- Global English Dutch French German Portuguese Spanish

- Algeria English French

- Angola English Portuguese

- Congo English French

- Gabon English French

- Ghana English French

- Ivory Coast English French

- Morocco English French

- Mozambique English Portuguese

- Tunisia English French

- China Mandarin English

Middle East

Latin america.

- Argentina English Spanish

- Brazil English Portuguese

- Chile English Spanish

- Colombia English Spanish

- Costa Rica English Spanish

- Dominican Republic English Spanish

- Ecuador English Spanish

- El Salvador English Spanish

- Guatemala English Spanish

- Honduras English Spanish

- Mexico Spanish English

- Nicaragua English Spanish

- Panama English Spanish

- Paraguay English Spanish

- Peru English Spanish

- Uruguay English Spanish

- Venezuela English Spanish

North America

- Canada English French

- Austria English German

- France French English

- Luxembourg English French

- Portugal English Portuguese

- Spain English Spanish

FCM Malta is recognised as one of the leading business travel management company.

FCM Malta is recognised as one of the leading business travel management company. Supported by a team with decades of experience in the travel industry, FCM Malta offers a unique level of expertise, personalised service and a commitment to fully understand the needs of every client. By taking a unique approach the agency also offers a diverse range of value-for-money corporate travel services.

FCM is recognised as a top, award-winning global travel management company, part of the Flight Centre Travel Group (FCTG). FCTG is publicly-listed on the Australian Stock Exchange and while its roots are in leisure travel, its corporate travel business has grown rapidly since the 1990s through strategic acquisitions and by enhancing its technological capabilities to strengthen FCM’s international market position.

Global Network

With a presence in more than 95 countries across the world, you are never far away from a friendly, and efficient service from FCM. We are one of the only global travel management companies with a true 24/7 worldwide reach.

Our experienced travel consultants are equipped to provide all our clients with a customised service based on their individual needs and provide unbeatable travel expertise.

Corporate Social Responsibility

The world is our workplace so at FCM we care about making it a better place. That is why as a multinational travel management company our Corporate Social Responsibility focuses on the global environment; this includes its wildlife, its people, their cultures and their economies.

Why Choose FCM

We achieve this by continually moulding our approach to your specific and developing travel requirements to create customised travel services and programmes. Our unique Customer Value Propositions (CVP) are the foundation of this personalised business travel approach.

Latest News

Follow us on Facebook

Our offices.

FCM Ewropa Business Centre, Dun Karm Street, Birkirkara Bypass, Birkirkara BKR 9034 Malta

+356 2345 6789 [email protected]

point cruz yacht club honiara

Sailing Conductors

Charting the Undiscovered

Sprache wählen

Point cruz yacht club, honiara – salomonische inseln (en).

That’s where everything began! That’s where we first saw and fell in love with our sailing boat “Marianne”. We spent 3 wonderful weeks anchoring at Point Cruz Yacht Club in Honiara. We quickly signed the bill of sale, before Paul, the old owner, could change his mind…

The owner of the bar Merry introduced us to Matt who immediately invited us to his home where we recorded our first artist – George.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Point Cruz Yacht Club

User Reviews

Contribute a Review ...

Distances (30)

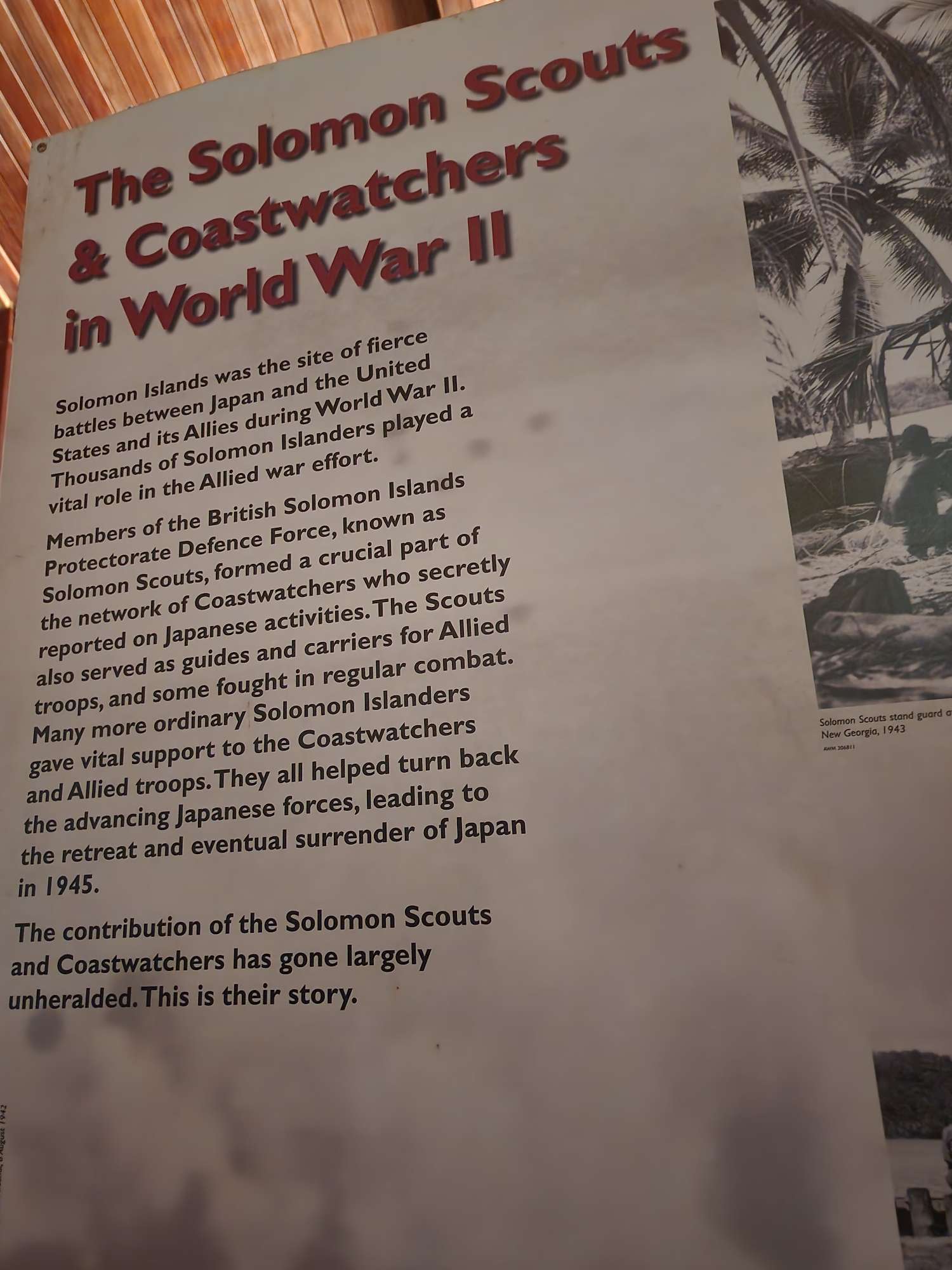

Solomon islands historical encyclopaedia 1893-1978.

Corporate entry: point cruz yacht club.

The new clubhouse of the Point Cruz Yacht Club in Honiara was opened by its Commodore, High Commissioner Sir Robert Foster, on 15 August 1964. ( NS 1 Aug. 1964)

Related entries

Related natural phenomena, published resources.

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate (ed.), British Solomon Islands Protectorate News Sheet (NS) , 1955-1975. Details

- Manage my booking Booking Reference Last Name Retrieve Booking

- Solomon Islands

- New Zealand

- French Polynesia

- Hong Kong, China

- New Caledonia

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- South Korea

- Taiwan, China

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Reservations 1300 894 311

Where do you want to go?

- 0 Children (2-11 Years)

- 0 Infant (0-2 Years)

- Port Moresby

- Honiara,Solomon Islands

- Munda,Solomon Islands

- Arona,Solomon Islands

- Atoifi,Solomon Islands

- Auki,Solomon Islands

- Balalae,Solomon Islands

- Bellona,Solomon Islands

- Choiseul Bay,Solomon Islands

- Fera,Solomon Islands

- Gizo,Solomon Islands

- Kagau,Solomon Islands

- Kirakira,Solomon Islands

- Lomlom,Solomon Islands

- Parasi,Solomon Islands

- Ramata,Solomon Islands

- Rennell,Solomon Islands

- Santa Ana,Solomon Islands

- Santa Cruz,Solomon Islands

- Seghe,Solomon Islands

- Suavanao,Solomon Islands

From To Change Route

- Destination Guide

- About the Solomons

- Explore Guadalcanal Province

Explore beyond Honiara in Guadalcanal

Home to the largest island in the solomon islands, guadalcanal province hosts the national capital, honiara. but also a smattering of cultural sites, well-preserved wwii relics, modest beaches, and a lost world to explore..

With well-preserved WWII relics along the northern coast, beautiful beaches, and remote retreats, Guadalcanal also offers fantastic diving at Iron Bottom Sound, the famous undersea graveyard where dozen of WWII wrecks have lain since 1942. Just off the northern coast, the island has the genuine look of a lost world. The hills behind the capital consist of a mighty mountain range rising to 2400m remains untamed and raw with a tropical rainforest climate.

War and History

The Guadalcanal campaign, also known as the Battle of Guadalcanal began on 07 August 1942 and lasted until February 1943. It was the first major land offensive by Allied forces against the Empire of Japan and during those seven months, 60,000 US Marines killed more than 20,000 of the 31,000 Japanese troops on the Island, a tremendous loss on all sides. The major objective of the fighting was a tiny airstrip the Japanese were building at the western end of Guadalcanal. The airstrip, later named Henderson Field, would become an important launching point for the Allied air attacks during the Pacific Island-hopping campaign.

Things to do

World War II Tours

There are many battle sites and relics of the war found in and around Honiara. Places of interest to visit include Bonegi Beach, Henderson Airfield, Vilu Museum, Red Beach, and Betikama Museum.

- Birdwatching

The major birding site of Mount Austen is just a 45-minute drive outside Honiara. A morning here can be very rewarding with sightings of Solomons Cockatoo, Yellow-bibbed Lory, Cardinal Lory, Buff-headed Coucal, perhaps Guadalcanal (Woodford’s) Rail, and Claret-breasted Fruit Dove. Mackinlay’s Cuckoo dove, Ultramarine Kingfisher, Brown-winged Starling, Long-tailed Myna, Chestnut-bellied Monarch, Cockerell’s Fantail, and Midget Flowerpeckers can also be seen with luck.

The Botanic Gardens in the main town are also worth a look - Duchess Lorikeet and Black-headed Myzomela are two of the more common species to be seen.

The Betikama Wetlands are also rich in birdlife and well worth a look.

There is a number of dive sites along the western part of Guadalcanal, including the famous WWII sites at Iron Bottom Sound and Bonegi Beach. Local dive operator Tulagi Dive is very experienced with all dive sites and the best ‘go-to organisation for divers looking to explore Guadalcanal’s underwater world.

Local guides can be arranged fishing trips around Marau Sound in eastern Guadalcanal and good fishing spots can also be found around the river estuaries of north-western Guadalcanal

Surfable waves can be found at the western end of Guadalcanal. It needs a two-hour, 40-minute drive from Honiara but is worth the journey during the wave season. Olotsara Retreat organises surfing tours – ask Tourism Solomons for more information.

Treks and Adventure

If a waterfall fan, there are a number of inland treks that will take you to the best cascades in Guadalcanal - Matanikau cascade, Tenaru Falls, and Barana Waterfalls. Note a local guide is essential for such trips. These can be arranged through local villages or with assistance from the Tourism Solomons office in Honiara.

Events & Festivals

Guadalcanal Second Appointed Day

The Second Appointed Day marks the establishment of the local Provincial Government for Guadalcanal Province and is celebrated with an annual public holiday celebrated with sports, speeches, and processions.

Guadalcanal Weaving Festival

Part of the Guadalcanal Second Appointed Day festivities and an excellent opportunity to engage with Guadalcanal culture and an event featuring demonstrations of traditional weaving from all over the province, the annual Guadalcanal Weaving Festival attracts hundreds of locals and visitors alike keen to engage with Guadalcanal’s culture. and discover more about the lifestyle, history and rich culture of the Guadalcanal people, an element that shapes their way of life.

Where to Stay

There are various accommodations types on offer in Guadalcanal with options ranging from resorts, guest houses, budget lodges, bungalows right through to the hotels of the capital including the Pacific Casino Hotel, the Heritage Park Hotel, the King Solomon Hotel, the Honiara Hotel, the Solomon Kitano Hotel and the recently opened Coral Sea Resort & Casino in the heart of town.

Tavanipupu Wellness & Spa Retreat is located in Marau Sound, the eastern part of Guadalcanal Province. A privately owned 5-star island resort in the South Pacific. Only 25 minutes east by plane from the Solomon Islands capital of Honiara. Another resort nearby, Milk Fish Resort is located at Marapa Island that offers 2 en-suite bungalows.

Food and Drinks

These days there is a surprising variety in good quality restaurants and cafes in and around Honiara with many catering to ex-pats.

- Central Market, located on the main road, is a great source of fresh fruit and vegetables. Fish and chips, as well as uncooked fish, are sold there.

- The Lime Lounge is located along Commonwealth Street serving coffee, cakes, burgers, and sandwiches.

- The Taj Mahal (Located downtown). Has good Indian and Sri Lankan food

- Point Cruz Yacht Club. The favored hangout of ex-pats in Honiara, the yacht club has a variety of simple and inexpensive meals available nightly.

- Palm Sugar (located at the Art Gallery) offers great coffee, burgers, soup, and many more

- Other suggestions include Heritage Park Hotel- Hadyns, IBS Restaurants, Garden Bar & Restaurants ( Pacific Casino), Coral Sea, Break Water, and Mambo Juice Bar.

Getting around

Local motorised canoes travel from Marau Sound along the weather coast to Honiara. There are irregular shipping services from Honiara to Marau Sound. MV Haura shipping runs weekly to Marau Station. Some buses services operate from Honiara to the Eastern (GPPOL 3) and western (Lambi) of Guadalcanal Province.

Travelling around Guadalcanal Province is a once-in-a-lifetime experience and an insight into a way of life that had remained unchanged across the years. Come explore Guadalcanal Province.

Tours and Activities

Kokonut pacific tour.

Visit and see the production and manufacturing of one of the Solomon Islands largest exports, the coconut. The people behind Kokonut Pacific produce oils, soaps, creams and much more. Join them for a 3-hour guided tour of their facility.

Honiara City Tour

Discover the capital of the Solomon Islands and surrounds on a tour of the city. Vist Point Cruz, the Coast Watchers Memorial, the Honiara Central Market, China Town, the US War Memorial, National Parliament, the National museum and more.

Island Day Tours from Honiara

Board a boat at Point Cruz to travel to the Central Province to see the area's famous World War II historical sites. Visit Gavutu Island where the Japanese built a big wharf during the war and Tokyo Bay where many Japanese War ships rushed to try to avoid being bombed by American Armed Forces. Savo Island tours are also available.

Waterfall Tours in Honiara

The hike up to the Mataniko Falls takes between 1-2 hours and begins from Lili village, behind New Chinatown and approximately 10-15 minutes from Honiara. The spectacular Tenaru Falls is an hour's drive and a three-hour hike from Henderson Airport. These two hikes will give you an appreciation of the terrain and what the Allied and Japanese soldiers went through during World War II.

Tulagi Dive

Iron Bottom Sound was the scene of some of WWII's biggest naval battles. It is the channel between Guadalcanal, Savo and the Florida islands and is the resting place for over 50 Japanese and Allied warships and fighter planes, hence the name "Iron Bottom". Noteable dives around Honiara include Hirokawa Maru, USS John Penn, and Kinugawa Maru. For the more experienced diver, try out the Aaron Ward in the nearby Florida Islands, the only diveable destroyer.

Battlefield tours in Honiara

Some of the most brutal World War II battles took place on the northern face of Guadalcanal. Visit Bloody Ridge, Red Beach, the Vilu War Museum, Betikama school relics, the American War Memorial, Tetere beach, The Thin Red Line, Honiara golf course (previously a US Airstrip), and the Japanese War Memorial (Mt Austen). Tours of both the Western Battlefield and Eastern Battlefield are also available.

Attractions

National museum and cultural centre.

The National Museum is modest but still worth a visit, for a taste of the history of the Solomon Islands. With exhibitions that traverse history and the diverse cultures that make up its almost 1000 islands, you can view old photographs, currency, weaponry and find out more about the history of World War II and the missionaries, both of which are core to the current national identity and way of life.

Savo Island from Honiara

Sunset Lodge on Savo Island is roughly an hour by boat from Honiara. It is from here experienced local guides will take you on a tour to Honiara's nearest active volcano. Savo is also known for its Megapode birds and eggs, a small bird that squeezes out eggs three times the size of a standard sized chicken egg. Perfect for a day trip or an overnight stay. For accommodation bookings, contact: +677 72 38977.

Bonegi Beach

Bonegi Beach is a haven for divers and beachgoers. Two Japanese freighters (Hirokawa Maru and Kinugawa Maru) bombed by the allies are beached right in front of the Bonegi stretch. They are the most dived wrecks in the country and are excellent for both beginners and more experienced divers due to proximity to the shore and the amazing coral and fish life that have made the freighters their home.

Accommodation

Heritage park hotel.

Centrally located, the Heritage Park Hotel is in an outstanding position for both business guests and leisure travellers who want to explore the attractions on offer in Honiara and its surrounds. The property is on the waterfront and with views from the bar out to the islands, especially breathtaking. All rooms are modern and exceptionally comfortable. The property is accessible by car from the airport.

Coral Sea Resort & Casino

With a traditional exterior and modern interior, the resort is focused on ensuring its guests are kept relaxed with a sun drenched pool entertainment area, outstanding bar and restaurants and ocean views over Honiara Harbour. The property is an oasis in the middle of the city and its styled rooms and villas will not disappoint. The resort is close to the CBD and accessible by car from the airport.

Solomon Kitano Mendana Hotel

The hotel is an excellent choice in Honiara with its fantastic location, spacious rooms and friendly environment. Enjoy Hakubai Japanese restaurant with fresh authentic choices from the menu or you can head over to Cowboys Bar and Grill which is a hotspot of an evening. The hotel has cool refreshing pool, evening entertainment and activities for kids. The hotel is accessible by car from the airport.

King Solomon Hotel

The hotel is centrally located in easy walking distance to the Solomon Islands Cultural Museum, banks, cafés, and shopping. The property has 73 rooms, many self-contained and suitable for long-term accommodation. There is an infinity waterfall pool, nightly entertainment, and a great view of Iron Bottom Sound.

Pacific Casino Hotel

With 142 spacious, comfortable, and airy rooms on the waterfront, enjoy all the amenities on offer. The kidney-shaped pool is a delight or enjoy a meal and cocktail at one of their dining venues. The casino is also a draw with its many games including crowd favorites Roulette and Blackjack and accessible by car from the airport.

Tavanipupu Spa & Wellness Retreat

This quaint property boasts having had British royalty stay. The grounds are manicured to perfection and handcrafted bungalows are richly appointed with all the comforts one desires. Enjoy a relaxing massage or laze away in the crystal clear water. Tavanipupu is accessible from Marau Airport, a 25 minute flight from Honiara.

Parangiju Mountain Lodge

This traditional property is hidden in the hills located in Central Guadalcanal. Amongst the rainforest, about an hour's drive from Honiara, enjoy the spectacular views, food, and local hikes. Tenaru Falls and the Bat caves are a very popular hike and a worthwhile three-hour round trip.

Ginger Beach Retreat

Gingers is 20km from Honiara, perched on the beachfront and surrounded by lush green jungle. It is a great place to relax in clean and comfortable traditional style accommodation done well. This is a great getaway for a destination wedding or group holiday and tours can also be arranged.

Sanalae Apartments

This boutique accommodation is located in a quiet setting 3 kilometers from the Honiara city centre, featuring self-contained apartments, ideal for business travellers and long term guests, as well as motel-style Garden Rooms. Light refreshments are offered at Reception for convenience.

Iron Bottom Sound Monarch Hotel

Located on the beachfront, 10 minutes walk from shops and services, this hotel features 30 guestrooms with garden views including standard rooms, studios and self contained apartments. All rooms are air-conditioned. Monarch Bar and Grill serves buffet and grilled dishes with live music each night.

Rock Haven Inn

An older style accommodation for those wanting affordable accommodation and a central location. Motel-style rooms with fans or air-conditioning, family units, and apartment-style with many offering sea views are on offer. There is also a restaurant on-site offering breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Milk Fish Bungalows

Located on the island of Marapa in the Marau Sound, and accessible via boat transfers from Marau Airport, Milk Fish Resort offers the ultimate setting for a relaxing getaway, simple, comfortable bungalows in natural surroundings with meals provided daily, waterfalls, treks, and small islands to explore on their doorstep.

Roderick Bay Beach Bungalows

Located in the stunning Sandfly Passage, Roderick Bay Beach Bungalows all overlook the wreck of the cruise vessel World Discoverer which was ran aground there and offers incredibly unique snorkelling and swimming experience. With 3 self-contained bungalows, village visits and a zip line from the World Discover itself, there is lots of fun to be had during a getaway.

B17 Dive & Beach Bungalows

Located about 40 minutes drive North West of Honiara, the accommodation offers self-contained beachfront bungalows with shared facilities and activities including swimming, snorkelling, scuba diving, Noni farm and village tours. In close proximity to the US B-17 Flying Fortress bomber after which the accommodation is named, it is the perfect location for divers, or for those who wish to simply relax.

Dolphin View Beach Guesthouse

This lesser known guesthouse is a quiet, relaxing place and named due to the dolphins that gather off the shore. With comfortable accommodation and shared facilities in Aruligho, guests can enjoy sea views, a barbecue, and the on-site bar in natural surroundings. Activities include snorkelling, canoeing and dolphin tours.

Anna Sherchand

Solo Female Travel Blog

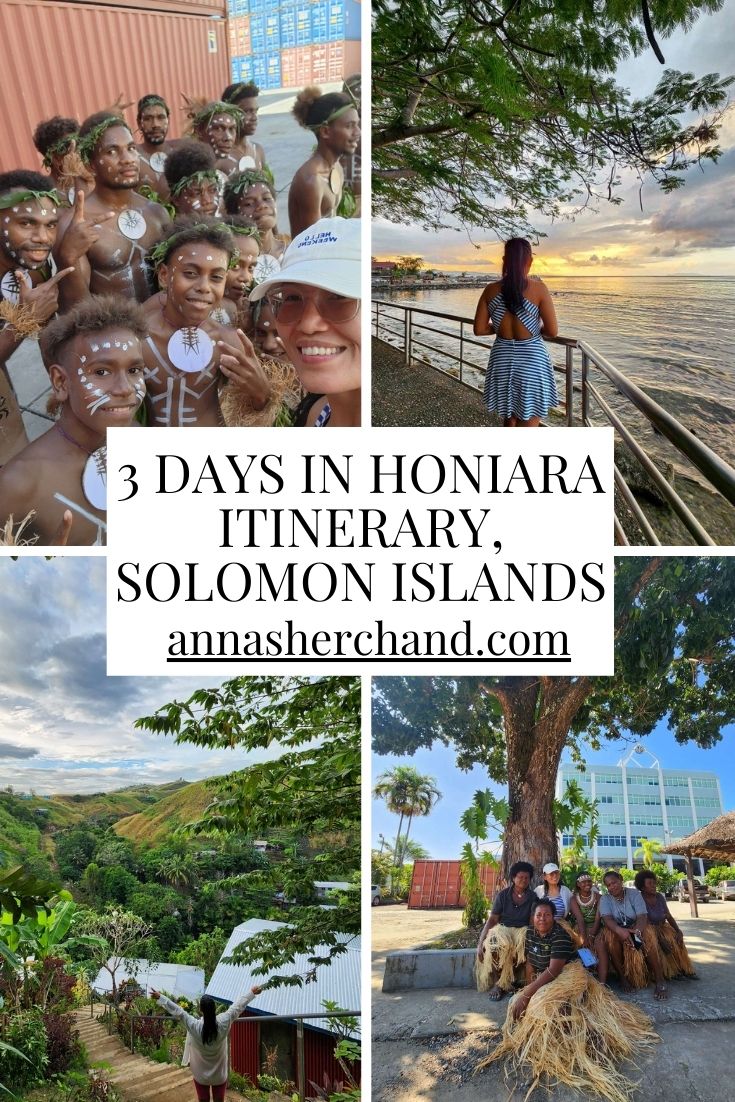

3 days in Honiara itinerary Solomon Islands

Firstly, when traveling to the South Pacific islands in Oceania, you have to be careful in planning it because the flights are usually once a week so if you miss it you will be stuck there for another week. So, after solo traveling to Papua New Guinea and spending 3 days in Port Moresby , my next stop was Honiara in the Solomon Islands. If you are thinking about going, here is 3 days in Honiara itinerary to help you plan.

The reason why I visited only the capital cities is because I don’t dive so no interest in exploring the outer islands and I live in Australia which means when I travel I don’t want to be chasing beaches as we have tons at home. Plus limited and expensive flights as well as being time-poor made me settled on those few days but you know what, it’s better to be there for a few days focusing on 1 place than being there and spending 1 day on each island or not being there at all.

With that said, I was super anxious about visiting the Solomon Islands because of the remoteness and lack of internet with that. But it all went down smoothly in the end. So if you are a little worried, I hope this 3 days in Honiara itinerary with the hidden gems, and must-see attractions, plus my solo travel tips to Honiara, give you some reassurance that if I can do it, so can you!

Nestled on the northern coast of Guadalcanal Island, Honiara stands as the vibrant capital city of the Solomon Islands. Known for its rich cultural heritage, pristine natural beauty, and intriguing history, Honiara offers a captivating blend of experiences for travelers seeking an authentic South Pacific adventure. Let’s delve deeper into the wonders of Honiara, where tradition meets modernity in a truly unique way.

- 3 days in Honiara itinerary

Day 1: Breakfast

2. visit the national museum, 3. visit the national art gallery, 4. visit unity square which is the paficif’s tallest flagpole, 5. grab lunch at the cafe bliss/ palm sugar/bethel cafe, 6. central market, 7. honiara botanical gardens, 8. speak to dive tulagi about arranging diving opportunities, 9. rent a car at economy car rentals for the next two days, 10. explore the local shops at npf plaza, 11. point cruz yacht club, 1. jacobs ladder, 2. breakfast at breakwater again, 3. guadalcanal american war memorial, 4. solomon peace memorial park (wwii japanese war memorial), 5. visit the willie besi war museum, 6. grab lunch at mambo juice, 7. visit the vilu military museum, 8. heritage park hotel for sunsets , 9. tenkai sushi cafe, 1. tenaru falls, 2. lunch at breakwater again, 3. bonegi beach, 4. get a massage, 5. pizza at the river house, solo travel tips to honiara, solomon islands, where to get the sim card, where to get the local currency, where to stay in honiara, how expensive are the solomon islands, how to get around honiara, when is the best time to visit the solomon islands, what is honiara known for, is honiara safe for solo travellers, let me know in the comments:.

I spent the 1st day in the town and planned outside-of-town activities for the two next days.

Start your day with good coffee/smoothies and breakfast at the Breakwater Cafe while enjoying the waterfront view. They don’t have wifi so important to get your own (info on where to get data – scroll below for solo travel tips to Honiara). This became my favorite cafe in Honiara for food and clearly for other people too so, def couldn’t work here due to a lot of people and noise.

Recommend Heritage Park Hotel or Mendana Hotel if you need to get some work done. Both hotels have restaurants and bring you your own internet as above.

On the opposite side of the cafe is the National Museum, where you can discover the rich cultural heritage and fascinating history of the Solomon Islands. Uncover the tales of ancient traditions and marvel at the remarkable artifacts on display.

There are two halls showcasing the history of Solomon Islands and don’t miss the cultural show at the back of the museum. The local ladies do a great job of demonstrating how they make different types of necklaces out of seashells and dance and you can buy the necklaces and other souvenirs there or at the gift shop. I learned a lot about the historical significance of the Solomon Islands, including Guadalcanal, which played a crucial role during World War II. Honiara’s strategic location made it a pivotal battleground in the Pacific campaign and they weren’t even themselves fighting. You can explore remnants of the war, such as the Guadalcanal American Memorial, the Japanese Peace Memorial, and the Vilu War Museum tomorrow (itinerary below). These sites offer insights into the conflict’s impact on the island and pay homage to those who sacrificed their lives.

Next door to the cafe is the National Art Gallery. It is small but does the job of telling the “red money story” in art forms and others. It’s next to a plaza with lots of artisan booths where you can buy carvings, paintings, and jewelry.

Honiara serves as a melting pot of diverse cultures, with over 60 different indigenous ethnic groups calling the Solomon Islands home. From the Malaitan, Guadalcanal, and Central provinces to the smaller islands surrounding Honiara, the city embraces a vibrant mix of languages, traditions, and customs. Engaging with locals provides a glimpse into their warm hospitality, ancient rituals, and captivating stories.

For a true taste of Honiara, immerse yourself in the bustling Central Market. Here, vibrant displays of tropical fruits, aromatic spices, and traditional handicrafts entice visitors. Indulge your taste buds in the flavors of the Solomon Islands by savoring local dishes like kokoda (marinated fish salad), taro, fresh seafood, and exotic fruits. The fusion of traditional ingredients and modern influences creates a culinary experience to remember.

Take a leisurely stroll through the Honiara Botanical Gardens, located near the city center. Enjoy the serene surroundings, lush greenery, and diverse plant species.

Head to the Point Cruz Yacht Club for dinner. This waterfront restaurant offers stunning views of the ocean and delicious seafood dishes. Relax and enjoy the evening atmosphere.

Believe it or not, this has been one of my highlights of visiting Honiara.

Jacobs Ladder is a well-known landmark for locals & hidden gem to visitors in Honiara. It is a steep staircase with approximately 800 steps that connect the upper part of the city to the lower coastal area. Here’s some information about Jacobs Ladder:

- Location: Jacobs Ladder is located near the city center of Honiara, specifically in the residential area of Point Cruz. It starts at the top of Murray Road and descends towards the coastline, ending near the Point Cruz Yacht Club.

- Purpose and History: Jacobs Ladder was constructed during World War II by American forces as part of the Guadalcanal campaign. It was initially built as an access point for military personnel to move quickly between the hilltop area and the waterfront.

- Fitness and Recreational Activity: Today, Jacobs Ladder has become a popular spot for fitness enthusiasts and visitors looking for a challenge. So obviously I had to do it & I was not disappointed. Started from the top & walked all the way down & around. The only thing I would say is to be mindful of some stray dogs. Luckily I met a local girl who helped me distract 5 dogs at one point but the second time around there was no one and, the dog barked at me so bad I was nervous and tripped, fell down & landed on my hands hurting my wrist! Be careful out there. Other than that, highly recommend it. Many locals have homes here and use the stairs for their daily commute. The steep climb provides a rigorous workout and is often used for fitness training but also offers beautiful panoramic views of the city and the sea.

- Scenic Views: As you ascend or descend Jacobs Ladder, you’ll be treated to stunning views of the Honiara skyline, the harbor, and the surrounding islands. It’s a great vantage point to capture photographs and appreciate the natural beauty of the area.

- Accessibility: Jacobs Ladder is open to the public and accessible to anyone who is physically capable of climbing the steep stairs. However, due to the high number of steps and the incline, it may not be suitable for individuals with mobility issues or certain health conditions. It’s recommended to take precautions, stay hydrated, and go at your own pace while using the stairs.

Visiting Jacobs Ladder in Honiara can be a rewarding experience, providing a combination of exercise, scenic views, and a glimpse into the city’s history. If you enjoy physical activities and want to challenge yourself, climbing Jacobs Ladder can be a memorable part of your visit to Honiara.

because I definitely deserved it after all that morning hike. Plus you can rent a snorkel at the cafe or diving equipment from Tulagi Dive. Be sure to confirm if available ahead of time.

More pictures. on Instagram highlight “Solomon Islands”

Head to the Guadalcanal American Memorial, which commemorates the World War II Battle of Guadalcanal. Take a moment to reflect on the historical significance of this site and pay homage to the brave soldiers who fought here. The World War II Guadalcanal American Memorial is located on Skyline Drive overlooking the town of Honiara, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands.

Located near the Guadalcanal American Memorial, pay a visit to the WWII Japanese Peace Memorial, dedicated to Japanese soldiers who lost their lives during the war. The memorial provides a tranquil setting for reflection.

Aka Vilu War Museum offers some wonderful displays of “relics” from the war here. Exhibits are collected from across the island and were a nice range of American and Japanese artifacts. It is a small open-air museum in Vilu open Mondays to Sundays 0730-1700, an entrance fee of 100 SBD p/p, and filming costs 1000 SBD.

Pretty decent Japanese food, I had Katsu Chicken for dinner.

Don’t forget to grab some snacks for tomorrow morning from the Chinatown Bulk Shop or others in town.

Honiara boasts breathtaking natural beauty, showcasing the Solomon Islands’ unspoiled paradise. The lush rainforests surround the hidden gems like Tenaru Falls, where cascading water creates a serene oasis for nature enthusiasts to explore. Here’s some information about Tenaru Falls:

You can either drive there or contact the Paranjiju Mountain Lodge (Amanda +677 71 01432) to align the guide to get up to the waterfalls as visitors are not allowed to go on their own. 600 SBD for it.

- Location: Tenaru Falls is situated about 30 kilometers east of Honiara, near the Tenaru River in the Guadalcanal Province of the Solomon Islands. It is nestled within a lush rainforest, offering a serene and picturesque setting.

- Natural Beauty: Tenaru Falls is a cascading waterfall that flows down a series of rock formations, creating a stunning display of water and natural beauty. The falls are surrounded by dense vegetation, including tropical trees and ferns, adding to the scenic charm of the area.

- Hiking and Exploration: To reach Tenaru Falls, you can embark on a moderate hiking trail that winds through the rainforest. The trail takes approximately 1-2 hours to complete, depending on your pace, and stops along the way. The journey offers an opportunity to immerse yourself in nature and appreciate the biodiversity of the region.

- Swimming and Relaxation: At the base of Tenaru Falls, there is a pool of clear water where visitors can take a refreshing dip and cool off. The pool is relatively shallow and provides a tranquil spot for swimming or simply relaxing amidst the natural surroundings.

- Local Guides: It is recommended to hire a local guide to accompany you on the hike to Tenaru Falls. They can provide valuable insights, ensure your safety, and share interesting information about the flora, fauna, and history of the area.

- Preparation: Before embarking on the hike, it is important to wear appropriate footwear, carry sufficient water, and use insect repellent to protect against mosquitoes and other insects. It’s also advisable to bring a camera to capture the beautiful scenery.

Visiting Tenaru Falls offers a chance to experience the natural wonders of the Solomon Islands and enjoy a peaceful escape from the city. The combination of hiking, swimming, and immersing yourself in the rainforest environment makes it a popular destination for nature lovers and adventure enthusiasts.

because I like their food and giant smoothies or Red Cross cafe for a local meal.

Snorkel at one of the many beaches west of Honiara by rental car or public bus. Some recommended beaches are Bonegi Beach, Lele, Turtle, Ginger, B-17, and Visale Beach with crystal-clear turquoise waters, perfect for snorkeling, swimming, and sunbathing.

at Jing’s Spa

Ps: make sure to arrive early at the airport – Honiara is hosting the Pacific games in November and they are currently fixing their roads etc so rain, bad roads, and traffic can lead to significant delays. Also, check out the memorial garden located right next to the airport- an excellent place to wait for your international flight after check-in or before. And Kuya cafe next door for last-minute pick-me-up coffee.

Note: Honiara comes alive during its colorful festivals and celebrations, providing a unique opportunity to witness the vibrancy of Solomon Islander culture. The annual Solomon Islands Arts Festival showcases traditional music, dance, and crafts, while the Guadalcanal Provincial Cultural Festival celebrates the province’s cultural heritage. These events offer a glimpse into the locals’ deep-rooted traditions and are a testament to their pride in their cultural identity. Pls, check with S.I. Visitors Bureau to get real-time info on when these are scheduled.

Honiara, with its rich cultural tapestry, intriguing history, and breathtaking landscapes, stands as a gateway to the wonders of the Solomon Islands. It offers an unforgettable journey that combines authenticity, natural beauty, and a warm sense of community, making it an ideal destination for adventurous solo female travelers.

As soon as you land you can pick up and top up your Telekom SIM card at the airport or at the Telekom office. And you can top it up in little roadside snacks/cellular top-up shops – I found one called Breezeland.

Unfortunately, there were no ATMs or currency exchange at the airport, lucky I had exchanged some PNG Kina for Solomon Dollars (SBD) prior to leaving PNG. It’s always a good idea to have some cash on hand before you arrive or to ensure you have an alternative method of payment in case the ATMs are out of service or experiencing technical issues.

Alternatively, you can exchange currency after your arrival at the Post Office and pick up some Solomon Islands postcards too.

Honiara, the capital city of the Solomon Islands, offers a range of accommodation options to suit different preferences and budgets. Here are some areas and hotels where you can consider staying in Honiara:

- Town Center: The town center of Honiara is a convenient location for accessing amenities, restaurants, and shops. Several hotels are situated in this area, providing easy access to key attractions and services. Examples of hotels in the town center include Heritage Park Hotel , Coral Sea Resort & Casino , and Solomon Kitano Mendana Hotel .

- Kukum/NPF Plaza: The Kukum area, near NPF Plaza, is another popular area to stay. It offers a range of mid-range and budget accommodations, including guesthouses and hotels. Some options in this area include King Solomon Hotel , Pacific Crown Hotel , and Honiara Pacific Hotel.

- Point Cruz: Point Cruz is a residential area located near the waterfront and offers a peaceful atmosphere. This area has a few hotels and guesthouses, such as The Pacific Hotel, King Solomon’s Palace, and Iron Bottom Sound Hotel.

- Tasahe: Tasahe is a suburban area located a short distance from the city center. It offers a more relaxed environment and is home to some upscale accommodations, such as the Coral Sea Villas and Honiara Hotel Motel.

- Lungga/Naha: Located outside the city center, the Lungga/Naha area provides a quieter setting and is known for its beautiful beaches. Accommodation options in this area include Guadalcanal Beach Resort.

When choosing a place to stay in Honiara, consider factors such as your budget, preferred location, proximity to attractions or activities, and the amenities offered by the hotel. It’s also advisable to book your accommodation in advance, especially during peak travel seasons, to secure your preferred choice.

The cost of visiting the Solomon Islands can vary depending on several factors, including your travel style, accommodation choices, dining preferences, and activities. Here is a general overview of the expenses you can expect in the Solomon Islands:

- Accommodation: Accommodation options in the Solomon Islands range from budget guesthouses to luxury resorts. Prices can vary significantly, with budget accommodations starting at around $55-80 AUD per night, while mid-range and higher-end options can range from $100 to several hundred dollars per night.

- Internet: Range of options available in terms of how much data you want to buy. For example, 1GB was $9 SBD and 2 GB was $11 SBD so it made sense to get the 2 GB. *155# to get data plans & *121# to check the balance. The internet speed was a little spotty but surprisingly worked most of the time.

- Food and Dining: Dining options in the Solomon Islands can be relatively affordable, especially if you opt for local eateries and markets. A basic meal at a local restaurant can cost around $10 AUD, while dining at mid-range restaurants may range from $15-30 AUD per person. Prices at high-end restaurants and resorts will be higher.

- Transportation: Transportation costs can vary depending on the distance and mode of travel. Taxis within Honiara and short trips within the city may cost around $5-10 AUD. Public buses (PMVs) are a more affordable option, with fares ranging from $1-5 USD depending on the distance but not reliable. Rental car prices vary, starting from around $100 AUD per day.

- Activities and Tours: The cost of activities and tours can vary widely depending on the type and duration. For example, diving and snorkeling trips can range from $50-150 AUD per dive or excursion. Guided cultural tours, visits to historical sites, and adventure activities can cost anywhere from $20 to a few hundred dollars per person.

- Flights: International flights to the Solomon Islands can be a significant expense, depending on your location and the time of booking. Prices for round-trip flights can vary widely, ranging from $500 to $2000 AUD or more, depending on factors such as the airline, season, and demand.

It’s important to note that these are rough estimates and prices can fluctuate. Additionally, remote areas or less touristy islands may have fewer accommodation and dining options, which can affect prices. It’s advisable to research and plan your budget accordingly, taking into account the specific activities and locations you plan to visit in the Solomon Islands. Regardless, people do vacation in the Solomon Islands because it is secluded & beautiful.

Taxis: Taxis are readily available in Honiara and can be found at taxi stands or hailed on the street. Public transport is not the best, so my best bet was to get taxis to get around. However, if you stay right in the city must-see places are located in the town. So you probably won’t need it unless for day trips.

There are two well-known taxi companies and they charge 10 SBD per KM

King Taxi and Crown Taxi +677 20777

Rental Cars: Renting a car can provide more flexibility and independence for exploring Honiara and its surrounding areas. Several car rental agencies operate in the city, and you can arrange a rental either in advance or upon arrival. Keep in mind that driving is on the left-hand side of the road in the Solomon Islands.

Walking: Honiara’s city center is relatively compact, making it suitable for exploring on foot. Walking allows you to immerse yourself in the local atmosphere, discover hidden gems, and easily access nearby attractions. However, be cautious and aware of your surroundings, especially in busy areas or at night.

The best time to visit the Solomon Islands, including Honiara, is during the dry season, which typically extends from April to November. This period offers more favorable weather conditions and is considered the peak tourist season. Here are some factors to consider when planning your visit:

- Weather: The dry season experiences less rainfall and more sunshine, making it ideal for outdoor activities and exploring the islands. The temperatures are generally warm and pleasant year-round, with average highs ranging from 28°C to 32°C (82°F to 90°F).

- Diving and Snorkeling: The months of April to October are particularly popular for diving, Whale watching, and snorkeling enthusiasts. The waters are generally calm and visibility is excellent, offering great opportunities to explore the vibrant coral reefs and marine life.

- Festivals and Events: The dry season also coincides with various cultural festivals and events in the Solomon Islands. These celebrations showcase traditional music, dance, arts, and crafts, providing a unique cultural experience for visitors.

- Crowds and Prices: The dry season is the peak tourist season in the Solomon Islands, which means that popular sites and accommodations may be more crowded. It’s advisable to book accommodations and activities in advance to secure your preferred options. However, it’s worth noting that prices for flights and accommodations may also be higher during this period.

- Wet Season Considerations: The wet season, from December to March, brings more rainfall and increased humidity to the Solomon Islands. While some travelers may still choose to visit during this time, it’s important to be prepared for potential rain showers and plan activities accordingly. Some outdoor activities and tours may be limited or disrupted during heavy rain.

It’s always recommended to check the current weather conditions and consult local resources when planning your visit to the Solomon Islands. Additionally, keep in mind that weather patterns can vary, and it’s possible to experience rainfall even during the dry season.

Honiara, the capital city of the Solomon Islands, is known for several notable features and attractions. Here are some things that Honiara is known for:

- World War II History: Honiara played a significant role during World War II as the site of the Battle of Guadalcanal. The city is known for its historical significance and various war-related sites, including the Guadalcanal American Memorial, Japanese Peace Memorial, and Vilu War Museum.

- Cultural Diversity: Honiara is home to a diverse population, representing various indigenous ethnic groups from the Solomon Islands. The city offers opportunities to experience and appreciate the rich cultural heritage through traditional music, dance, arts, crafts, and local customs.

- Central Market: The Central Market in Honiara is a bustling hub where locals gather to sell and purchase fresh produce, seafood, handicrafts, and traditional artifacts. It’s a vibrant place to immerse yourself in the local atmosphere, sample local cuisine, and engage with friendly vendors.

- Pristine Beaches and Marine Life: Honiara boasts stunning beaches with crystal-clear waters and vibrant marine life. Places like Bonegi Beach and Visale Beach offer opportunities for snorkeling, diving, and enjoying the beauty of the Pacific Ocean.

- Natural Wonders: Honiara is surrounded by lush rainforests and natural wonders. Tenaru Falls, located just outside the city, offers a serene hiking experience leading to a magnificent waterfall. The Honiara Botanical Gardens provide a tranquil escape with a variety of flora and fauna to explore.

- Melanesian Art and Crafts: Honiara is known for its vibrant art scene and the production of Melanesian arts and crafts. The city offers a range of galleries and craft markets where you can find traditional wood carvings, shell jewelry, paintings, and other unique artworks.

- Warm Hospitality: The locals of Honiara are known for their friendly and welcoming nature, providing a warm and hospitable atmosphere for visitors. Interacting with the residents offers insights into their way of life, traditions, and cultural practices.

These are just a few highlights of what Honiara is known for. Besides, the country’s blend of history, culture, natural beauty, and warm hospitality makes the Solomon Islands worth visiting and an intriguing destination for travelers seeking an authentic South Pacific experience.

Honiara can generally be considered safe for solo travelers, but it’s important to exercise caution and take necessary precautions, as with any travel destination. Here are some factors to consider:

- Personal Safety: Like in any city, it’s advisable to be mindful of your surroundings, particularly at night and in less crowded areas. Avoid displaying valuable items openly and be cautious of pickpocketing or petty theft. It’s recommended to use common sense, trust your instincts, and take appropriate safety measures.

- Local Advice: Seek local advice and information from trusted sources such as your hotel or reliable tour operators. They can provide insights into areas to avoid or precautions to take based on the current situation in Honiara.

- Transportation: Ensure that you use reliable and licensed taxis or transportation services. It’s recommended to agree upon a fare before starting your journey. Avoid hitchhiking or accepting rides from strangers.

- Respect Local Customs: Familiarize yourself with the local customs and cultural norms. Respecting the traditions and sensitivities of the local population can help create a positive and safe experience for solo travelers.

- Emergency Contacts: Keep important contact numbers, including your embassy or consulate, local authorities, and emergency services, readily available in case of any unforeseen situations.

- Travel Insurance: It’s always advisable to have comprehensive travel insurance that covers medical emergencies, personal belongings, and trip cancellations. Ensure that your insurance policy is suitable for the activities you plan to undertake in Honiara.

While Honiara is generally safe, it’s essential to stay informed, use common sense, and take necessary precautions to ensure a safe and enjoyable solo travel experience. As with any travel destination, it’s advisable to research and be aware of the local customs, laws, and potential risks before your trip.

if you have any other questions on this 3 days in Honiara itinerary 3 days in Port Moresby 5 days in Apia Samoa itinerary 5 days in Nuku’alofa Tonga itinerary Grampians itinerary for 3-4 days Best day trips from Hobart, Tasmania Day trip to Stradbroke Island , Queensland Weekend in Brisbane Best places to visit in autumn in Australia Backpacking in Melbourne, Australia Digital nomad guide to Melbourne Sydney itinerary 5 days Best places to see autumn leaves in Adelaide Exploring Adelaide the best way All Adelaide travel blogs 10 hidden beaches and bays in Sydney 99% of readers found must see on the east coast of Australia helpful. Sydney bucketlist things Sydney itinerary for 5 days Secret Sydney walks Best places to take photos in Sydney Pros and cons of living in Australia where to stay in Sydney Hidden beaches and bays most instagrammable cafes in Sydney where to eat in Sydney most Instagrammable places in Sydney, Australia Most beautiful places in New Zealand North Island Check out the most beautiful places in New Zealand South Island Going to Vietnam after Australia? Check out the 7 days Hanoi travel guide. One month in Central America itinerary Solo trip to Phoenix , Arizona How about Colombia? Check out how to get from Medellin to guatape Check out where to stay in Medellin , Colombia Check hotel prices and book it through booking.com Read the most wanted travel resource here. If you like this article, read about my journey to becoming a solo female Nepali Australian travel blogger , follow my adventures on Instagram , Facebook , YouTube , Twitter , and Pinterest , but most importantly sign up for my e-mail list to keep up with updates and travel posts!

- ← Experience Paradise: Day Trip to Stradbroke Island

- Yarra valley itinerary and the must sees in Dandenong ranges →

You May Also Like

Hidden Gems in Australia

Travel to Nepal during Covid

Digital nomad guide to Melbourne

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

From CruisersWiki

Honiara is the capital city of the Solomon Islands.

See Solomon Islands .

Communication

Add here VHF channel for coastguard, harbor masters. etc.

Also see World Cruiser's Nets

Approach Point Cruz lining up the post in front of the yacht club with the post further up on the hill. There are green and red (unlit) buoys marking the entrance. The latest C-MAP ED3 2012 is correct, some of the older C-MAP ED2 show you off to the W on the reef.

Updated Oct 2012 by Kestrahl

Honiara is a port of entry for the Solomon Islands. For details see Entrance: Solomon Islands .

Anchoring stern up to the seawall is it seems harder than it used to be, as this space is currently taken up by local charter boats that it seems have moorings off the seawall.

There is also a new big dock in the middle that has recently been constructed and takes up a fair amount of space.

Marinas & Yacht Clubs

Point Cruz Yacht Club is on the shore at the head of the bay. It is the place to land your Dinghy and fairly safe to leave it. The Club is more a hang a out-bar for the older expat crowd than a yacht club but they are generally friendly and helpful. The Club offers free temporary membership to overseas visitors. The bar and kitchen are open for lunch and dinner. Cold showers and laundry facilities are available plus WiFi.

As at Oct 2012 there are 7 visiting cruising yachts here all swinging free on the W side of the harbor near the yellow mooring buoy. The mooring buoy can be rented - see notice board at point Cruz club.

Provisioning

Give the names and locations of supermarkets, grocery stores, bakeries, etc.

Bar at the Yacht Club

Transportation

List transportation (local and/or international.)

Give a short history of the port.

Places to Visit

List places of interest, tours, etc.

Contact details of "Cruiser's Friends" that can be contacted for local information or assistance.

List links to discussion threads on partnering forums . ( see link for requirements )

- Honiara at the Wikipedia

- Honiara at the Wikivoyage

We welcome users' contributions to the Wiki. Please click on Comments to view other users' comments, add your own personal experiences or recommend any changes to this page following your visit.

Verified by

Date of member's last visit to Honiara and this page's details validated:

If you provide a lot of info and this page is almost complete, change {{Page outline}} to {{Page useable}}.

- View source

Personal tools

- WIKI CONTENTS

- Countries (A to Z)

- News Updates

- Recent Changes

- About and Contact

- Page Templates

- The test editing page

Copyright Issues?

- Report Here

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

advertisement

Friends of cruisers wiki.

- Cruisers Forum

- Cruisers Log

- This page was last modified on 21 August 2018, at 07:46.

- This page has been accessed 13,265 times.

- Content is available under C.C. 3.0 License .

- Privacy policy

- About CruisersWiki

- Disclaimers

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Following History’s Footsteps on Guadalcanal

T he first footprints appeared on the stretch of Guadalcanal shore code-named “Red Beach” on August 7, 1942. Made by Marine Corps–issue boots, these were truly historic imprints: America’s first steps toward the ultimate, unconditional victory over Japan almost exactly three years later.

By the conclusion of the crucial battle in the southern Solomon Islands—a battle that also raged in the skies above and roiled the waters around the roughly 2,000-square-mile island until February 1943, and resulted in nearly 40,000 total casualties—there would be countless more footprints, along with the rapid accumulation of more tangible evidence of the clash. As I prepared to set foot on Guadalcanal nearly 70 years later, I wondered how many of the battle’s footprints remained.

In Europe and the United States one typically finds shiny plaques, paved guide paths, and meticulously maintained museums, monuments, and cemeteries. But many Pacific War sites remain largely undisturbed, laden with potential for not only discovery, but head-shaking sadness as well. A combination of unchecked jungle growth, unrelenting tides, and the unremitting effects of time and poor preservation efforts is steadily erasing from existence the ruins, wrecks, guns, and bunkers that have stood as symbolic sentinels for decades.

So, much like the Marines who landed that August day with little ammunition and food, I commenced the expedition with uncertainty. Little did I know that on the “Canal,” history, however hidden, is always just a few footsteps away.

It was literally under my feet only moments after my Air Pacific jet landed on the tarmac: Honiara International Airport is built upon the exact site of Henderson Field, the focal point of the six-month campaign—awakening me to the realization that Joe Foss, Bob Galer, John L. Smith, and the other legendary pilots of the Cactus Air Force once trod this very same ground.

The past quickly vanished in the dusty bustle of Honiara, the seaside Solomon Islands capital city home to 79,000—but only temporarily, thanks to John Innes. Innes is the modern incarnation of the intrepid scouts and coastwatchers who guided the Marines throughout the battle. Born in London during the war, Innes arrived in the Solomons via Australia and a work-related move. He was bitten shortly thereafter. “You can cure malaria,” Innes likes to say, “but there is no cure for the history bug.”

After decades of locating aircraft wrecks, helping recover and identify remains, and accompanying veterans on what can best be considered emotional archaeological digs, Innes has assumed a much-needed role as Guadalcanal’s on-site historian. While Solomon Islanders are very friendly and hospitable, most remain largely unaware of the historical significance of the soil on which they live. Or perhaps they just want to forget. “Having no word for ‘war’ in their native tongue,” Innes said, those present at the time of the battle referred to it as the “Big Death.”

There are no signs marking the site of the infamous Goettge Patrol massacre on the grounds of the United Church in downtown Honiara. Nor, if not for Innes, would I have known that the fairways of the Honiara Golf Course were once home to Fighter Two, the airstrip from which the P-38s of the 339th Fighter Squadron lifted off on April 18, 1943, and shot down Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

The majority of the island’s historic sites, however, are located outside of the littered, betel nut–spattered streets and sidewalks of Honiara. Over the course of several exhausting yet exhilarating days, I retraced the footsteps made by Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson’s Second Marine Raider Battalion on the Long Patrol, an epic march that cleared Japanese troops and artillery from Mount Austen, the 1,514-foot monolith that dominates Guadalcanal’s interior, and hunkered down behind strands of rusty barbed wire that still circle the Lunga Perimeter, as they had in October, 1942.

On Japanese Memorial Hill, I stood upon slabs of white sun-washed stone framed by white frangipani and red hibiscus, representative of the national colors of Japan, to scan the sweeping vistas of the island panorama. Atop an eerily calm Edson’s Ridge, where, from September 12–14, 1942, a handful of Marines repulsed a massive Japanese attack and saved Henderson Field, I crouched in a depression that was once a foxhole and contemplated the identity and the emotions of the young Marines who fought there The reverberating thunder of artillery salvos from the 11th Marine Regiment’s 105mm guns has long since faded; only ocean breezes breathe across the island, gently rustling the golden-green fields of kunai grass that carpet the ridges.

And I learned not to follow in Japanese footsteps—literally. The sprawling Lever Brothers coconut plantation that Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki’s men marched west through, toward a resounding defeat at the Battle of the Tenaru, no longer exists. The easiest contemporary route passes along what was once the southern boundary of Henderson Field, past clumps of red ginger and sugar cane, onto Block Four Road. That path, little more than a jungle trail, delivers you to Alligator Creek and the sandbar where hundreds of Japanese fell before Marine machine guns on August 21, 1942.

Near the inland area known as the Gifu, where American forces reduced the last pockets of Japanese resistance in the battle’s final stages, the residents of Barana village display war relics on crowded tables: rusty bayonets, helmets, .50-caliber machine gun barrels, Marston matting, Coca-Cola bottles, and shell casings. Just off Tetere Beach, rows of amtracs sit among massive banyan trees, as if in preparation for the next island invasion.

The most impressive collection of war relics is at the Vilu War Museum, located 21 kilometers west of Honiara off the northwest coastal road. Walled by towering coconut palms and flowering coroton trees are a series of boneyard “exhibits:” nearly complete skeletons of an F4F Wildcat, an F4U Corsair, an SBD Dauntless dive bomber, and a P-38 Lightning. There is also a Type 97 Japanese tank, three 105mm guns, and a 155mm howitzer, plus an arsenal of deactivated ordnance ranging from 500-kilogram Japanese bombs to mortar shells.

And the best part? Much like the rest of Guadalcanal, the museum is hands-on history. There are no display cases, velvet ropes, or flash photography rules. For the entry price of 25 Solomon Island dollars (about $3), proprietor/curator Anderson Dua will invite you to touch whatever you please. Dua even happily showed me how to fold the creaking wing of the carrier-design Wildcat.

I continued my march further west along the northwest road, bouncing down a tunnel of tall palms to remote Koli Point, where the Japanese were able to evacuate approximately 13,000 starving troops in February 1943. The surf softly laps the black sands of Koli, perhaps the best place to visually absorb Savo Island, which rises out of the glassy, swelling surface of Ironbottom Sound like a half-moon.

On August 9, 1942, the first major naval engagement of the campaign took place off Savo Island; it was the biggest naval disaster in American history with the exception of Pearl Harbor. Although the extreme depths of Ironbottom Sound insure that most of the wrecks will remain hidden history, some of the estimated 690 aircraft and 200 vessels in the waters around Guadalcanal are divable. For those who want to see wrecks up close without getting wet, there is LST 342. Torpedoed off New Georgia in July 1943, the tank landing ship was blown in two, yet the bow was deemed salvageable enough to be towed to what is now its eternal mooring in Purvis Bay, off Florida Island, about a one-hour trip via charter from Honiara.

History’s constant close proximity on Guadalcanal was driven home to me one evening, as Innes and I were relaxing at Honiara’s Point Cruz Yacht Club, overlooking Savo and Florida Islands. About 20 paces away was a plaque memorializing Signalman Douglas Munro, and I realized I was gazing out on the site where Munro had earned the Congressional Medal of Honor—the only member of the U.S. Coast Guard to do so. Munro was mortally wounded on September 27, 1942, while leading several Higgins boats to Point Cruz to evacuate Marines. He reportedly remained conscious long enough to ask, “Did they get off?”

Yet of all the memorials on Guadalcanal, no words are more appropriate than those etched into the marble walls of the American Memorial located atop Skyline Ridge overlooking the Matanikau River valley, on what was known during the battle as Hill 73:

“May this memorial endure the ravages of time until the wind, rain and tropical storms wear away its surface, but never its memories.”

As long as one can follow the historic footprints, these memories will endure.

John D. Lukacs is a writer and historian whose work has appeared in USA Today, the New York Times , and on ESPN.com. His first book, Escape From Davao: The Forgotten Story of the Most Daring Prison Break of the Pacific War , will be published in paperback by Penguin/NAL in May. His next book, on the Battle for Manila in 1945, will be published by Penguin/NAL Caliber.

When You Go Honiara International Airport is serviced by Air Pacific, Air Vanuatu, Our Airline (formerly known as Air Nauru), Pacific Blue, and Solomon Airlines. Getting around Guadalcanal is not difficult; rental cars are available, and taxis are both plentiful and affordable.

Where to Stay and Eat The new Heritage Park Hotel (www.hph.com.sb, 677-24007), located in the Honiara waterfront area on the site of the former governor-general’s residence, offers superb service, a sparkling pool, luxury stylings, and multiple amenities. Japanese troops called Guadalcanal “Starvation Island,” but you won’t go hungry when visiting. The Point Cruz Yacht Club offers a tasty assortment of nightly specials and is highly recommended. The Renaissance restaurant and The Terrace at Heritage Park Hotel offer formal and casual dining experiences featuring European and Pan-Asian fare.

What Else to See Guadalcanal is acquiring a reputation as one of the Pacific’s premier eco-tourism destinations. Birdwatchers, wildlife enthusiasts, fishermen, and scuba divers flock to the Solomons. Extreme Adventures (solomonadventures.com) offers “seafari” tours, snorkeling, and fishing expeditions. Divers should contact divemaster Neil Yates (www.tulagidive.com.sb, 677-32131). For fishing and day charters, as well as a few good fish stories, Mike Hammond at Fishing Solomon (677-24498) will help you get underway.

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

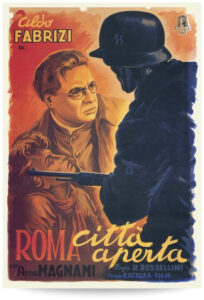

Filmed During WWII, This Italian War Film Started Its Own Cinematic Genre

“Rome, Open City” even used German POWs as extras.

Civil War Generals Never Forgot the Blood and Lost Friends in the US Showdown with Mexico

At the outset of the Civil War, generals on both sides were not surprised by the bloodshed they witnessed.

if (!inwiki && isMobileDevice){ document.write(' (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ');} Point Cruz Yacht Club, Honiara (Honiara)

- Similar places

- Nearby places

- Nearby cities

- Mt. Vatunjae 20 km

- Mt. Esperance 35 km

- Marau Sound 100 km

- Mt. Mariu 211 km

- Mt. Vangunu 237 km

- Nakumwe 242 km

- Mt. Mahimba 266 km

- Mt. Mangela 285 km

- Sikaiana (Stewart Islands) 341 km

- Southwestern Nauru 1255 km

- Honiara International Airport (AGGH) 11 km

- Mt. Gallego 26 km

- Ironbottom Sound 34 km

- Guadalcanal 36 km

- Savo Volcano 37 km

- Savo 37 km

- Mbungana 39 km

- Purvis Bay 46 km

- Nggela Sule 47 km

- Nggela Pile 52 km

- 2706 km

- 2751 km

- 2800 km

- 2814 km

- 2833 km

- 2837 km

- 2847 km

- 3476 km

- 3482 km

Post comment

or continue as guest

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Advertising

- Coast Guard

- Humanitarian Aid

- Marine Safety

- Search and Rescue

- Defense Readiness

- Drug Interdiction

- Law Enforcement

- Migrant Interdiction

- Waterway Security

- Aids to Navigation

- Environmental Protection

- ice operations

- Living Marine Resources

- Marine Environmental Protection

We Remember Signalman First Class Douglas A. Munro

Signalman First Class Douglas Monro

The Coast Guard’s first major participation in the Pacific war was at Guadalcanal. Here the service played a large part in the landings on the islands. So critical was their task that they were later involved in every major amphibious campaign during World War II. During the war, the Coast Guard manned over 350 ships and hundreds more amphibious type assault craft. It was in these ships and craft that the Coast Guard fulfilled one of its most important but least glamorous roles during the war–that is getting the men to the beaches. The initial landings were made on Guadalcanal in August 1942, and this hard-fought campaign lasted for nearly six months. Seven weeks after the initial landings, , on September 27, 1942, during a small engagement near the Matanikau River, Signalman First Class Douglas Albert Munro, died while rescuing a group of marines near the Matanikau River.

Douglas Munro grew up in the small town of Cle Elum, Washington. Enlisting in September 1939, Munro volunteered for duty on board the USCG cutter Spencer where he served until 1941. While on board he earned his Signalman 3rd Class rating. In June, President Roosevelt directed the Coast Guard to man four large transports and serve in mixed crews on board twenty-two naval ships. When word arrived that these ships needed signalmen, Munro, after much pleading with Spencer’s executive officer, was given permission to transfer to the Hunter Liggett (APA-14). This 535 foot, 13,712 ton ship, was one of the largest transports in the Pacific. She carried nearly 700 officers and men and thirty-five landing boats including two LCTs. In April 1942, the “Lucky Liggett” sailed to Wellington, New Zealand, to prepare for a major campaign in the south pacific.

On 7 August 1942, the United States embarked on its first major amphibious assault of the Pacific War. After the successes at Coral Sea and Midway the United States decided to counter Japanese advances in the Solomon Islands. These islands form two parallel lines that run southeast approximately 600 miles east of New Guinea. Tulagi and Guadalcanal, both at the end of the chain were picked for an assault. Guadalcanal was strategically important because the Japanese were building an airfield, and if finished would interfere with the campaign.

Wreaths are presented on the grave of Signalman 1st Class Douglas A. Munro during a memorial ceremony held in his honor at Laurel Hills Memorial Cemetery in Cle Elum, Wash., Sept. 25, 2015. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Katelyn Shearer)

Eighteen of the twenty-two naval troop carrying ships attached to the campaign’s task force carried Coast Guard personnel. These men were assigned an integral part in the landings–the operation of the landing craft. Many of the Coast Guard coxswains had come from Life-Saving stations and their experience with small boats made them the most seasoned small boat handlers in government service.

The Coast Guard manned transports played a prominent role in the initial landings at Guadalcanal, Tulagi and other nearby islands. As the task force gathered, Munro, now a signalman first-class, was assigned to temporary duty on the staff of Commander, Transport Division Seventeen. During the preparations for the invasion, Munro was transferred from ship to ship, as his talents were needed. The task force rendezvoused at sea near the end of July and on 7 August the Liggett led the other transports to their anchorage off Guadalcanal. Hunter Liggett served as the amphibious force command post until the Marines secured the beaches.

At he time of the invasion, Munro was attached to the staff of Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner on board McCawley (APA-4). Munro made the landing on Tulagi Island where fierce fighting lasted for several days. About two weeks later Munro was sent twenty miles across the channel to Guadalcanal where the Marines had landed and had driven inland. One of the bloodiest and most decisive battles ensued. The Americans quickly seized the airfield on the island but for six months both the U.S. and the Japanese poured troops onto Guadalcanal in an attempt to gain control and force the other off.

Marines assigned to Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor, Wash., render a three-volley salute in honor of Coast Guard Signalman 1st Class Douglas Munro during a memorial ceremony at Munro’s gravesite in Cle Elum, Wash., Sept. 26, 2014. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Katleyn Shearer)

After the initial landings at Guadalcanal, Munro and twenty-four other Coast Guard and Navy personnel were assigned to Lunga Point Base. The base was commanded by Commander Dwight H. Dexter, USCG, who was in charge of all the small boat operations on Guadalcanal. The base, situated on the Lever Brothers coconut plantation consisted of a small house with a newly constructed coconut tree signal tower. Munro was assigned here because of his signalman rate. The base served as the staging area for troop movements along the coast. To facilitate this movement, a pool of landing craft from the numerous transports lay there to expedite the transportation of supplies and men.

A month into the campaign, the Marines on the island were reinforced and decided to push beyond their defensive perimeter. They planned to advance west across the Matanikau River to prevent smaller Japanese units from combining and striking American positions in overwhelming numbers. For several days near the end of September, the Marines tried to cross the river from the east and each time met tremendous resistance. On Sunday, 27 September, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller embarked three companies of his 7th Marines in landing craft. They planned to land west of the river, drive out the Japanese, and establish a patrol base on the west side of the Matanikau.

A photo of the memorial to Douglas Munro at the Point Cruz Yacht Club, Honiara, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands.

The landing craft were dispatched from Lunga Base. Douglas Munro, just two weeks short of his twenty-third birthday, took charge of ten LCPs and LCTs (tank lighters) to transport Puller’s men from Lunga Point to a small cove west of Point Cruz. The Marines landed with the support of the destroyer U.S.S. Monssen which laid down a covering barrage with her five inch batteries shortly after twelve o’clock. Major Ortho L. Rodgers, commanding the landing party reached the beach in two waves at 1:00. The 500 unopposed Marines pushed inland and reorganized on a ridge about 500 yards from the beach. At about 1:50, approximately the same time they reached the ridge, their gunfire support was disrupted by a Japanese bombing raid. Monssen had to withdraw to avoid seventeen high level Japanese bombers. Unfortunately, this occurred at the same time that the Marines were struck by an overwhelming Japanese force west of the river. This situation deteriorated when Major Rodgers was killed and one of the company commanders was wounded.

After the Marines landed, Munro and the boats returned to Lunga Point Base. A single LCP remained behind to take off the immediate wounded. Coast Guard petty officer Ray Evans and Navy Coxswain Samuel B. Roberts manned the craft. They kept the craft extremely close to the beach to take off the wounded as quickly as possible. The Japanese, meanwhile had worked behind the Marines and without warning a machine gun burst hit the LCP parting the rudder cable and damaging the boat’s controls. After jury rigging the rudder, Roberts was struck by enemy fire and Evans managed to jam the controls to full ahead and sped back to Lunga Point Base. Unable to stop, the LCP ran onto the beach at 20 mph. Roberts later died but won the Navy Cross posthumously.

Coast Guard recruits in training participated in a ceremony to honor Petty Officer 1st Class Douglas Munro Sept. 27, 2010.

As Evans arrived at the Lunga Point base, word arrived that the Marines were in trouble and were being driven back toward the beach. Their immediate plight had not been known. The bombing raid had driven Monssen out of range to visually communicate with shore. Furthermore, the three companies of Marines had failed to take a radio and were unable to convey their predicament. Using under-shirts they spelled out the word “HELP” on a ridge not far from the beach. Second Lieutenant Dale Leslie in a Douglas SBD spotted the message and passed it by radio to another Marine unit. At 4 P.M. Lt. Colonel Puller, realizing that his men were isolated, embarked on Monssen to direct personally the covering fire for the marines who were desperately trying to reach the beach.

The landing craft had meanwhile been readied at Lunga Point Base. Again, virtually the same boats that had put the Marines on the beach were assembled to extract them. Douglas Munro, who had taken charge of the original landing, volunteered to lead the boats back to the beach. None of these boats were heavily armed or well protected. For instance, Munro’s Higgin’s boat had a plywood hull, it was slow, vulnerable to small arms fire, and was armed only with two air-cooled .30 caliber Lewis machine guns.

As Munro led the boats ashore the Japanese fired on the small craft from Point Cruz, the ridges abandoned by the Marines, and from positions east of the beach. This intense fire from three strong interlocking positions disrupted the landing and caused a number of casualties among the virtually defenseless crews in the boats. Despite the intense fire Munro led the boats ashore. Reaching the shore in waves, Munro led them to the beach two or three at a time to pick up the Marines. Munro and Petty Officer Raymond Evans provided covering fire from an exposed position on the beach.

As the Marines reembarked, the Japanese pressed toward the beach making the withdrawal more dangerous with each second. The Monssen and Leslie’s Douglas “Dauntless” dive bomber provided additional cover for the withdrawing Marines. The Marines arrived on the beach to embark on the landing craft while the Japanese kept up a murderous fire from the ridges about 500 yards from the beach. Munro, seeing the dangerous situation, maneuvered his boat between the enemy and those withdrawing to protect the remnants of the battalion. Successfully providing cover, all the Marines including twenty-five wounded managed to escape.

For his heroic and selfless actions in the completion of this rescue mission Munro was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the only Coast Guardsman in history to receive the award.

Douglas Munro lived up to the Coast Guard’s motto–“Semper Paratus”, Always Ready.

- Stewardship

This site is owned and operated by Bright Mountain Media, Inc., a publicly owned company trading with the symbol: BMTM .

Copyright © 2024 Coast Guard News . All rights reserved. Privacy Policy Terms of Use

WordPress Theme designed by Theme Junkie

- Preliminary pages

- List of figures

- List of maps

- List of plates

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- A note on nomenclature

- Introduction

- 1. Nahona`ara before 1942

- 2. Taem blong faet: Camp Guadal

- 3. The new capital

- 4. The other Honiara

- 5. Municipal authority and housing

- 6. Building infrastructure

- 7. Building society and the nation

- 8. Stepping-stones to national consciousness

- 9. Since independence

- 10. The village-city

- Bibliography

Since independence

Plate 9.1 Busy Mendana Avenue in 2014.

Once lined with shade trees, Honiara’s main street has become a hot and dusty area dominated by bitumen, concrete, and traffic jams.

Source: Christopher Chevalier Collection.

Modern Honiara