M Marks the Spot: Star Trek's Planet Classifications, Explained

Star Trek's characters use a very specific system to classify the planets they encounter. Each letter and category has its own specific meaning.

The bright, optimistic future of Star Trek entailed regular scientific exploration, which was part of Starfleet’s mantra. That included an entire lexicon of terms, to better sell the show’s setting and to provide the sheen of rigor to its various dramatic plots. Planets were grouped according to class – each one with different features and details – which became a part of the world-building and continued to be used in subsequent Star Trek series. The most enticing was Class M , which was a planet capable of sustaining humanoid life. That meant new alien beings, new cultures and civilizations, or even just a suitable spot to set up a colony.

But class M wasn’t the only type of planet in the Star Trek lexicon. Nine others were mentioned at one point or another during the series, each with a letter demarking their status. A list of all classifications follows, along with a brief description of their conditions.

RELATED: Star Trek: Lower Decks Reveals What Kind of Captain Riker Really Is

Class D: Barren Rock

Class D referred to a planet or planetoid completely devoid of atmosphere. The most prominent example in canon was Regula, the planetoid from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan . Spock described it as “a great rock in space,” composed of unremarkable elements and of little note beyond that.

Class H: Uninhabitable

The class H designation in Star Trek canon was vague, though largely uninhabitable by most humanoid species. One exception was the Sheliak, an “R-3” lifeform consisting of what appeared to be sentient blobs. They laid claim over several Class H worlds, which the Federation ceded to them as part of a treaty. However, a class H planet named Tau Cygna V was inhabited by human colonists, provoking a diplomatic incident with the Sheliak that the Enterprise-D resolved in Star Trek: the Next Generation Season 3, Episode 2, “The Ensigns of Command.”

RELATED: Star Trek: Lower Decks Confidently Beams Back for a Charming & Silly Season 2

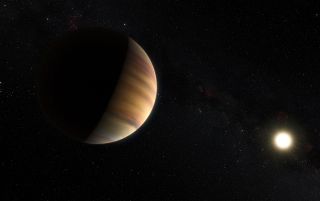

Class J: Gas Giant

Class J was designated a manner of gas giant, akin to Jupiter. They are uninhabitable by humanoid life forms though their varying layers of atmosphere could conceivably carry life of a non-humanoid sort. The most prominent onscreen appearance came in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Season 4, Episode 7, “Starship Down.” The Defiant engaged in a game of cat-and-mouse with the Jem’hadar in the atmosphere of a remote planet fitting the classification.

Class K: Habitable with Modifications

A class K planet was deemed habitable in many ways, but with surface conditions too harsh to support humanoid life. That could include anything from extreme temperatures to lack of a breathable atmosphere. People could live on such worlds with help from technological devices such as pressurized air domes or underground structures, but exposure to the surface without protective gear would be lethal. The Original Series Season 2, Episode 12, “I, Mudd” was set on a class K planet, beneath a dome controlled by androids where Harry Mudd set himself up as king.

RELATED: Star Trek: Lower Decks' Noël Wells & Eugene Cordero Discuss Starfleet's Joy

Class L: Marginally Habitable

Class L planets held all of the components suitable for human life, and could often support such life for extended periods of time. They are usually quite barren, though some contain arable land and others are able to support colonies of hundreds of thousands of people. Class L planets are mentioned regularly throughout the franchise, notably in multiple episodes of Star Trek: Voyager .

Class M: Habitable

The vast majority of Star Trek’s alien worlds are class M, featuring a sustainable oxygen atmosphere, viable ecology and other Earth-like qualities. That allows all manner of life to develop on them and provides a convenient location for franchise's stories. Most civilized worlds in the Star Trek universe are class M, including Earth, Vulcan, Qo’noS and Andoria -- though Andoria is technically a moon. The “M” stands for “Minshara,” a Vulcan term used in Star Trek: Enterprise , though none of the other planetary classes had in-canon designations beyond the letters.

RELATED: Star Trek: Lower Decks' Tawny Newsome & Jack Quaid Tackle Starfleet's Besties

Classes N and R: Habitable With Unknown Modifiers

Both class N and class R planets are deemed habitable, though they differ from Class M planets in a manner that the Star Trek canon has yet to lay out. In both cases, their respective atmospheres are sensitive to specific types of explosives. Beyond that, their properties are unknown. Both were mentioned for the first time in The Next Generation Season 4, Episode 17, “Night Terrors.”

Class T: Gas Giant

A class T is a gas giant, similar to a class J. As with classes N and R, there is no current in-canon explanation for the differences between the two. Class T planets have thus far only been mentioned once in the franchise: Voyager Season 6, Episode 20, “Good Shepherd.” The Delta flyer encounters one bearing rings, though it’s unknown if those are the distinguishing factor for the class or not.

RELATED: Star Trek: Discovery Season 4 Release Date, Trailer, Plot & News to Know

Class Y: Demon Planet

Class Y planets were designated “demon planets” due to their overtly toxic and dangerous atmospheres, and for their often hellish surface appearance. That could include surface temperatures higher than 500 degrees Kelvin and radiation discharges that were actively harmful to humanoid life. Its most notable appearance came in Voyager Season 4, Episode 24, “Demon,” which used a class Y planet as its primary focus.

KEEP READING: Star Trek: One of the Series' Most Quoted Phrases Was Never Actually Said

In planetary classification, a class A geothermal planet is a type of planet. As the name describes, the planet is generally geothermally active, generating heat. This type of planet is usually in the very early stages of development and are likely to evolve into other classes. No lifeforms have ever been discovered on these planets.

In planetary classification, a class B geomorteus planet is a type of planet. This type of planet is usually very close to, and heated by, a parent star, featuring very little native geothermal energy. The atmosphere of these worlds is usually tenuous, and features little or no chemically active particles. No lifeforms have ever been discovered on these planets. Mercury is an example of a class B geomorteus planet.

In planetary classification, a class C geoinactive planet is a type of planet. As the name describes, the planet is generally geothermally inactive, generating no heat energy. This type of planet is usually in the very late stages of development and has likely evolved from other classes. No lifeforms have ever been discovered on these planets.

In planetary classification, a class D planetoid is a type of planet. Planets of this type are generally smaller asteroids or moons that are locked into the gravitational pull of a larger planetary body. Class D worlds are usually composed of metals, predominantly nickel, iron and silicate. Bodies of this type generally do not support lifeforms.

A Class E planet is one that has a high temperature and a molten surface.

A Class F planet is a planet that has volcanic eruptions due to a molten core.

Class G geocrystalline, in planetary classification, is a type of planet. The relatively young geocrystalline worlds have also been classified as class F planets on other scales, and are possessed of a mostly carbon dioxide atmosphere with some toxic gases, released as the planet cools and crystallizes. Lifeforms usually only exists as single-celled organisms due to the absence of free water on the young world. These planets are generally between three to four billion years old and measure 10,000 to 15,000 kilometers in diameter.

A Class H planet is a planet that is hot and arid with little or no water.

A Class I planet is a planet that has a very tenuous surface made up of gasseous hydrogen and hydrogen compounds.

A Class J planet is a planet that has a surface composed of gasseous hydrogen and hydrogen compounds.

A Class K planet is a planet that can be adapted for humanoid habitation.

In planetary classification Class L is a category of planet, only marginally habitable by humanoid life. Such planets are though capable of supporting humanoid colonization.

The Class M (or Minshara-class) planet is the most stable type for humanoid habitation. Class M planets may feature large areas of water, if water or ice covers more than 80% of surface then the planet is considered Class O or Class P.

A Class N planet is a planet that has a high surface temperature due to a greenhouse effect and water exists only as vapor.

In planetary classification Class O or Pelagic planets are those who's surfaces are comprised of 80% or more water. These planets may have some land, but it is not a majority feature. An example of a class O planet is Argo, the planet Earth is very close to Class O.

A Class P planet is a planet that is covered by water ice and is capable of supporting life.

The Class Q, from the old Vulcan Quaris class, is a type of planet that has rarely been encountered by the Federation. Conditions vary widely on class Q worlds, with very hot and cold regions and great variety in surface conditions.

A Class R planet is a planet that drifts through interstellar space or in cometary halos.

Classes S and T planets are planets of enormous size that have very tenuous surfaces made up of gasseous hydrogen and hydrogen compounds.

A Class Y planet is a planet that has a turbulent atmosphere, saturated with toxic chemicals and thermionic radiation.

Planet Classification

This list comprises all planet classes and all individual planets of each class that were shown or mentioned on screen. Exception: For Class M, there are just a number of examples from a total of probably over a hundred planets.

I am aware that the classification system has been consistently supplemented in the book Star Trek Star Charts by Geoffrey Mandel to include several more letters, but that is non-canon.

List of Canon Planet Classes

Planet Mutations - recurring planets whose appearance varies

Planets in TOS and TOS Remastered - Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 - survey of the TOS planet models and how they were remastered

Re-Used Planets in TNG - all the planets that appeared from twice up to eleven times

Re-Used Planets in DS9 - all the planets that appeared from twice up to six times

Some screen caps from TrekCore . Data taken from the Star Trek Encyclopedia III , the Star Trek Archive , Chakoteya and Memory Alpha . Thanks to Googolplex for a hint about another Class-L planet.

https://www.ex-astris-scientia.org/database/planet_classes.htm

Last modified: 30 Jun 2022

© Ex Astris Scientia 1998-2024, Legal Terms

This website is not endorsed, sponsored or affiliated with CBS Studios Inc. or the Star Trek franchise.

Fleet Yards

Planetary Classification

From star trek: theurgy wiki.

A planet is a celestial body in orbit around a star or stellar remnants, that has sufficient mass for self-gravity and is nearly spherical in shape. A planet must not share its orbital region with other bodies of significant size (except for its own satellites), and must be below the threshold for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium.

If a celestial body meets those requirements, it is considered a planet; at that point, the planet is further classified by its atmosphere and surface conditions into one of twenty-two categories.

Class A - Geothermal

Class A planets are very small, barren worlds rife with volcanic activity. This activity traps carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and keeps temperatures on Class A planets very hot, no matter the location in a star system. When the volcanic activity ceases, the planet "dies" and is then considered a Class C planet.

Class B - Geomorteus

Class B planets are generally small worlds located within a star system's Hot Zone. Highly unsuited for humanoid life, Class B planets have thin atmospheres composed primarily of helium and sodium. The surface is molten and highly unstable; temperatures range from 450° in the daylight, to nearly -200° at night. No life forms have ever been observed on Class B planetoids.

Class C - Geoinactive

When all volcanic activity on a Class A planet ceases, it is considered Class C . Essentially dead, these small worlds have cold, barren surfaces and possess no geological activity.

Class D - Dwarf

Also known as Plutonian objects, these tiny worlds are composed primarily of ice and are generally not considered true planets. Many moons and asteroids are considered Class D , as are the larger objects in a star system's Kuiper Belt. Most are not suitable for humanoid life, though many can be colonized via pressure domes.

Class E - Geoplastic

Class E planets represent the earliest stage in the evolution of a habitable planet. The core and crust is completely molten, making the planets susceptible to solar winds and radiation and subject to extremely high surface temperatures. The atmosphere is very thin, composed of hydrogen and helium. As the surface cools, the core and crust begin to harden, and the planet evolves into a Class F world.

Class F - Geometallic

A Class E planet makes the transition to Class F once the crust and core have begun to harden. Volcanic activity is also commonplace on Class F worlds; the steam expelled from volcanic eruptions eventually condenses into water, giving rise to shallow seas in which simple bacteria thrive. When the planet's core is sufficiently cool, the volcanic activity ceases and the planet is considered Class G.

Class G - Geocrystalline

After the core of a Class F planet is sufficiently cool, volcanic activity lessens and the planet is considered Class G . Oxygen and nitrogen are present in some abundance in the atmosphere, giving rise to increasingly complex organisms such as primitive vegetation like algae, and animals similar to sponges and jellyfish. As the surface cools, a Class G planet can evolve into a Class H, K, L, M, N, O, or P class world.

Class H - Desert

A planet is considered Class H if less than 20% of its surface is water. Though many Class H worlds are covered in sand, it is not required to be considered a desert; it must, however, receive little in the way of precipitation. Drought-resistant plants and animals are common on Class H worlds, and many are inhabited by humanoid populations. Most Class H worlds are hot and arid, but conditions can vary greatly.

Class I - Ice Giant (Uranian)

Also known as Uranian planets, these gaseous giants have vastly different compositions from other giant worlds; the core is mostly rock and ice surrounded by a tenuous layers of methane, water, and ammonia. Additionally, the magnetic field is sharply inclined to the axis of rotation. Class I planets typically form on the fringe of a star system.

Class J - Gas Giant (Jovian)

Class J planets are massive spheres of liquid and gaseous hydrogen, with small cores of metallic hydrogen. Their atmospheres are extremely turbulent, with wind speeds in the most severe storms reaching 600 kph. Many Class J planets also possess impressive ring systems, composed primarily of rock, dust, and ice. They form in the Cold Zone of a star system, though typically much closer than Class I planets.

Class K - Adaptable

Though similar in appearance to Class H worlds, Class K planets lack the robust atmosphere of their desert counterparts. Though rare, primitive single-celled organisms have been known to exist, though more complex life never evolves. Humanoid colonization is, however, possible through the use of pressure domes and in some cases, terraforming.

Class L - Marginal

Class L planets are typically rocky, forested worlds devoid of animal life. They are, however, well-suited for humanoid colonization and are prime candidates for terraforming. Water is typically scarce, and if less than 20% of the surface is covered in water, the planet is considered Class H.

Class M - Terrestrial

Class M planets are robust and varied worlds composed primarily of silicate rocks, and are highly suited for humanoid life. To be considered Class M, between 20% and 80% of the surface must be covered in water; it must have a breathable oxygen-nitrogen atmosphere and temperate climate.

Class N - Reducing

Though frequently found in the Ecosphere, Class N planets are not conducive to life. The terrain is barren, with surface temperatures in excess of 500° and an atmospheric pressure more than 90 times that of a Class-M world. Additionally, the atmosphere is very dense and composed of carbon dioxide; water exists only in the form of thick,vaporous clouds that shroud most of the planet.

Class O - Pelagic

Any planet with more than 80% of the surface covered in water is considered Class O . These worlds are usually very warm and possess vast cetacean populations in addition to tropical vegetation and animal life. Though rare, humanoid populations have also formed on Class O planets.

Class P - Glaciated

Any planet whose surface is more than 80% frozen is considered Class P . These glaciated worlds are typically very cold, with temperatures rarely exceeding the freezing point. Though not prime conditions for life, hearty plants and animals are not uncommon, and some species, such as the Aenar and the Andorians , have evolved on Class P worlds.

Class Q - Variable

These rare planetoids typically develop with a highly eccentric orbit, or near stars with a variable output. As such, conditions on the planet's surface are widely varied. Deserts and rain forests exist within a few kilometers of each other, while glaciers can simultaneously lie very near the equator. Given the constant instability, is virtually impossible for life to exist on Class-Q worlds

Class R - Rogue

A Class R planet usually forms within a star system, but at some point in its evolution, the planet is expelled, likely the result of a catastrophic asteroid impact. The shift radically changes the planet's evolution; many planets merely die, but geologically active planets can sustain a habitable surface via volcanic outgassing and geothermal venting.

Class S - Gas Supergiant

Aside from their immense size, Class S planets are very similar to their Class J counterparts, with liquid metallic hydrogen cores surrounded by a hydrogen and helium atmosphere.

Class U - Gas Ultragiant

Class U planets represent the upper limits of planetary masses. Most exist within a star system's Cold Zone and are very similar to Class S and J planets. If they are sufficiently massive (13 times more massive than Jupiter), deuterium ignites nuclear fusion within the core, and the planet becomes a red dwarf star, creating a binary star system.

Class X - Chthonian

Class X planets are the result of a failed Class T planet in a star system's Hot Zone. Instead of becoming a gas giant or red dwarf star, a Class X planet was stripped of its hydrogen/helium atmosphere. The result is a small, barren world similar to a Class B planet, but with no atmosphere and an extremely dense, metal-rich core.

Class Y - Demon

Perhaps the most environmentally unfriendly planets in the galaxy, Class Y planets are toxic to life in every way imaginable. The atmosphere is saturated with toxic radiation, temperatures are extreme, and atmospheric storms are amongst the most severe in the galaxy, with winds in excess of 500 kph.

Disclaimer Notice

Page used with permission of USS Wolff CO - granted Nov 1, 2016 Images by Chris Adamek and used with permission from http://sttff.net/

- Starfleet Information

- General Information

Star Trek Planetary Classification Explained for All Trekkers

- by Kingsley Felix

- October 15, 2023

Star Trek fans are familiar with the concept of planetary classification, which is a system used to describe the characteristics of planets in the Star Trek universe.

Various species and organizations use the classification system , including the Federation and the Vulcans.

Planets are assigned a letter designation based on their characteristics, such as their ability to support life.

The most well-known planetary classification is Class M, which is used to describe planets that are capable of supporting humanoid life.

Other classes include Class H, which is hazardous to humanoid life, and Class D, which is barren and lifeless.

The classification system is an important part of the Star Trek universe, as it helps characters understand the characteristics of the planets they encounter during their travels.

Understanding planetary classification is essential for any Star Trek fan, as it is a key part of the lore and world-building of the franchise.

By learning about the different classes of planets and their characteristics, fans can gain a deeper appreciation for the vastness and complexity of the Star Trek universe.

Whether you’re a longtime fan or new to the franchise, planetary classification is an important concept to understand.

Star Trek Planetary Classification

Class M planets are the most common type of planet in the Star Trek universe.

They are also known as Minshara class planets and are considered to be habitable by humanoid life forms.

These planets have a breathable atmosphere, stable climate, and gravity that is tolerable to humanoids.

In the Federation standard system of planetary classification, a class M planet, moon, or planetoid is considered to be suitable for humanoid life.

The Federation has charted thousands of class M planets, and they are the first choice for colonization.

The requirements for a planet to be classified as class M are an atmosphere of oxygen and nitrogen, proximity to a stable star, fertile soil, and tolerable gravity.

These planets are also often rich in natural resources and have diverse flora and fauna.

Some well-known class M planets in the Star Trek universe include Earth, Vulcan, Romulus, and Qo’noS.

These planets have played significant roles in the various Star Trek series and movies, and their distinct cultures and histories have been explored in depth.

Class M planets are essential to the Star Trek universe and serve as a backdrop for many of the franchise’s stories.

They are a testament to the imagination and creativity of the Star Trek writers and have captured the hearts and minds of fans for decades.

Class D planets are small, barren, and rocky celestial bodies that are devoid of any atmosphere. They are also known as planetoids or asteroids.

These planets are characterized by their rough, cratered surfaces and their lack of any significant geological activity.

The most prominent example of a Class D planet in the Star Trek universe is Regula, the planetoid from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

Spock described it as “a great rock in space,” composed of unremarkable elements and little note beyond that.

Class D planets are not suitable for life as they lack the necessary atmosphere and environmental conditions that support life.

However, they can be used for mining purposes as they contain valuable minerals and resources.

In planetary classification, Class D is the lowest classification for a planet.

It is important to note that Class D planets are not to be confused with Class F planets, which are also barren and uninhabitable but have a thin atmosphere.

Overall, Class D planets are small, barren, and rocky celestial bodies that lack an atmosphere and are not suitable for life.

They are often used for mining purposes due to their valuable resources.

Class H planets are characterized as usually being uninhabitable by most humanoid species but viable for Sheliak.

Such a planetary body could contain an atmosphere consisting of oxygen and argon.

According to the Federation standard system of planetary classification, Class H planets are typically barren, with no native life forms.

However, the Sheliak have laid claim to several Class H worlds, which the Federation ceded to them as part of a treaty.

Class H planets are largely uninhabitable due to their harsh environments, which are often characterized by extreme temperatures, harsh winds, and dangerous atmospheric conditions.

They are often barren and lifeless, with no vegetation or water sources. For most humanoid species, these planets are inhospitable and impossible to survive on for an extended period.

While Class H planets may be uninhabitable for most species, they can still be of scientific interest.

Scientists may study these planets to learn more about their geology, atmospheric conditions, and other characteristics.

They may also be used as a source of raw materials for mining and other industrial purposes.

In conclusion, Class H planets are typically barren and uninhabitable by most humanoid species.

However, they can still be of scientific interest and may be used as a source of raw materials.

The Sheliak have laid claim to several of these planets, which the Federation has ceded to them as part of a treaty.

Class J planets are gas giants similar to Jupiter and are uninhabitable for humanoid life forms.

However, their varying layers of the atmosphere could conceivably carry a life of a non-humanoid sort.

These planets are characterized by their thick, gaseous atmospheres and are usually found in the outer regions of a star system.

One of the most prominent onscreen appearances of a Class J planet was in the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Season 4, Episode 7, “Starship Down.”

In this episode, the USS Defiant was forced to land on a Class J planet after being attacked by a Jem’Hadar warship.

The planet’s atmosphere was so thick that the Defiant was unable to use its transporters, forcing the crew to make repairs while under attack.

Class J planets are also known for their powerful magnetic fields, which can interfere with the navigation systems of starships.

In some cases, these magnetic fields can even cause a ship to crash if the pilot is not careful.

Overall, Class J planets are fascinating celestial bodies that offer unique challenges and dangers to those who explore them.

While they may not be suitable for humanoid life, they are still important to study to understand the universe around us better.

Class K planets are considered habitable with modifications. These planets have surface conditions that are too harsh to support humanoid life without the use of pressure domes and life support systems.

An example of a Class K planet is Mudd, characterized as being adaptable for Humans by using pressure domes and life support systems.

Class K planets are not ideal for long-term habitation but can be used for temporary bases or colonies.

These planets often have extreme temperatures, a lack of a breathable atmosphere, and other challenging environmental conditions.

Despite their challenges, Class K planets can offer valuable resources such as minerals or energy sources.

For example, the planet Delta Vega, which was a Class K planet, was used as a lithium cracking station in an alternate reality.

Overall, Class K planets are considered to be a valuable resource for short-term colonization and resource extraction, but they are not suitable for long-term habitation without significant modification.

Class L planets are a type of planet classification in the Star Trek universe.

These planets are known as barely habitable planets, planetoids, and moons that can support humanoid life with additional means.

They are characterized by having higher concentrations of carbon dioxide than other planets.

Class L planets can have different kinds of atmospheres ranging from suitable for humanoid life to unsuited without additional means.

They are marginally habitable, and they hold all of the components suitable for human life. They could often support such life for extended periods of time.

Class L planets have been encountered in the Star Trek universe in various episodes.

For example, the Genesis Planet in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan was classified as a Class L planet. The planet was created by the Genesis Device and had a rapidly evolving ecosystem.

Class L planets are a unique type of planet classification in the Star Trek universe.

They are marginally habitable, and while they can support humanoid life with additional means, they are not suitable for long-term habitation.

Class N planets were a type of planet in the Federation standard system of planetary classification.

These planets were inhospitable to most forms of life due to their harsh and often extreme environments.

They were characterized by their high levels of tectonic activity, volcanic eruptions, and seismic disturbances.

Despite their inhospitable nature, Class N planets were sometimes inhabited by alien life forms that had adapted to their harsh environments.

One such planet was Majalis, which was home to a species of sentient beings known as the Majalans.

Commercial transports carrying passengers from Class N worlds had to make special accommodations to ensure their safety and comfort.

These accommodations were necessary due to the extreme conditions present on Class N planets.

In summary, Class N planets were inhospitable to most forms of life due to their extreme environments, but some alien life forms had adapted to survive on them.

Commercial transports had to make special accommodations for passengers from these planets due to the extreme conditions present.

Class R is a planetary classification used to describe a type of terrestrial planet.

These planets are characterized by their rugged terrain, often featuring steep cliffs, deep canyons, and rocky outcroppings.

They are also known for their geothermal activity, which can produce intense heat and volcanic activity.

The Federation uses a fissionable explosive called plutonium ryanite for large-scale excavations on the surface of Class R planets.

This explosive is highly effective at breaking up the tough, rocky terrain and allowing for easier access to the planet’s resources.

Despite their harsh conditions, Class R planets can still support life.

However, life on these planets is often adapted to extreme conditions, such as heat-resistant flora and fauna.

In conclusion, Class R planets are a unique and challenging exploration and resource extraction environment.

Their rugged terrain and geothermal activity require specialized equipment and techniques, but the rewards can be great for those willing to take on the challenge.

Class T planets are gas giants typically located in a star system’s outer regions.

These planets are characterized by their extremely hazardous conditions, including intense radiation, high levels of atmospheric pressure, and extreme temperatures.

As a result, they are considered uninhabitable by most known sentient species.

According to Star Trek: Star Charts, a class T planet is a gas giant classified as a “large ultra giant,” 50,000,000 to 120,000,000 kilometers in diameter, with an age of two to ten billion years.

These planets are typically composed of hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of heavier elements. A system of moons and rings often surrounds them.

Class T planets are often the site of scientific exploration and research due to their unique properties.

They are also sometimes used as hiding places or bases by rogue groups or individuals due to their inhospitable conditions.

In some cases, they have been used as a weapon against enemy forces by exploiting their hazardous environments.

Overall, Class T planets remain one of the most mysterious and dangerous types of celestial bodies in the Star Trek universe.

While they may offer valuable scientific insights, they pose significant risks to any attempting to explore or inhabit them.

Class Y planets are characterized by a toxic atmosphere, sulfuric deserts, surface temperatures exceeding five hundred Kelvin, and thermionic radiation discharges.

These planets are uninhabitable for humanoid life and are considered highly dangerous for any exploration.

The Federation standard system of planetary classification has classified only a few planets as Class Y.

One such planet is the Kolarus III, which was explored by the crew of the Enterprise NX-01 in the early 22nd century.

The planet was found to be uninhabitable due to its toxic atmosphere and high surface temperatures.

Class Y planets are also known to have unique geological features. For example, the Kolarus III had a large number of geothermal vents that were releasing toxic gases into the atmosphere.

These vents were also responsible for the high surface temperatures on the planet.

Due to the high level of danger associated with Class Y planets, Starfleet has strict protocols in place for any exploration.

Any Starfleet vessel that encounters a Class Y planet is required to stay at a safe distance and gather as much data as possible using remote sensors.

In conclusion, Class Y planets are highly dangerous and uninhabitable for humanoid life.

Toxic atmospheres, sulfuric deserts, and high surface temperatures characterize them.

Starfleet strictly regulates the exploration of these planets due to their high level of danger.

Class P planets are characterized by their unique properties and conditions.

These planets are often referred to as “Proto-planets” due to their early stage of development.

They are rocky worlds with little to no atmosphere and are often found in the process of forming.

Class P planets are not suitable for humanoid life as they lack the necessary conditions to support it.

They have no magnetic field, no atmosphere, and no water. They are also geologically active, with frequent volcanic activity and earthquakes.

Due to these conditions, Class P planets are often used for scientific research purposes.

One notable example of a Class P planet is the planetoid Bajor. Bajor was a Class P planet located in the Bajoran system.

It was home to the Bajoran people and was a major location in the Star Trek universe.

The planet was initially explored by the Cardassians, who stripped it of its resources and enslaved the Bajoran people.

After the Cardassians left, the Bajorans regained control of their planet and joined the United Federation of Planets.

In conclusion, Class P planets are rocky worlds in the early stages of development.

They are unsuitable for humanoid life and are often used for scientific research.

One notable example is Bajor, which was home to the Bajoran people and played a major role in the Star Trek universe.

Additional Information

Planetary classification is a crucial aspect of the Star Trek universe.

The classification system used by the Federation uses single-letter designations such as class M to describe a planet able to support humanoid life for long periods, while the Vulcans use the term “Minshara class” to describe a similar planet.

According to Memory Alpha , the planetary classes used in Star Trek are as follows:

- Class D: Dead planets

- Class H: Hadean planets

- Class J: Gas giants

- Class K: Desert planets

- Class L: Marginal planets

- Class M: Terrestrial planets

- Class N: Glaciated planets

- Class P: Ocean planets

- Class R: Rogue planets

- Class T: Molten planets

- Class Y: Demon planets

It is important to note that not all planets in the Star Trek universe fit neatly into these classifications.

Some planets may have unique characteristics that do not fit into any of these categories.

In addition to the classifications, various sub-classifications are used to describe a planet’s characteristics further.

These sub-classifications include:

- Atmosphere: The type of gases present in a planet’s atmosphere.

- Temperature: The average surface temperature of a planet.

- Hydrosphere: The amount of water present on a planet’s surface.

- Biosphere: The presence of life on a planet.

Background information suggests that the Federation classifies planets based on criteria such as atmospheric composition, surface temperature and conditions, the size of the body, and the presence of animal and plant life.

This system is used to determine the suitability of the planet for exploration, colonization, and scientific research.

The appendices of various Star Trek publications provide additional information on planetary classifications.

These appendices often include detailed information on each planetary class’s characteristics and examples of planets that fit into each class.

Overall, planetary classification is an important aspect of the Star Trek universe.

It allows characters to quickly and accurately describe the planets they encounter and provides a framework for understanding the unique characteristics of each planet.

Kingsley Felix

Kingsley Ibietela Felix is a digital media publishing entrepreneur and founder of Krafty Sprouts Media, LLC. A 2-time African blogger of the year. Kingsley can be found researching, reading, watching football, playing games, discussing politics or creating great content.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

You May Also Like

20 Best Websites to Read Comics Online

- by Jennifer Uwadiare

- September 26, 2022

What Is Amazon Prime Video?

- by Emmanuella Oluwafemi

- October 28, 2019

5 Different Types of Lighting in Film Explained

- by Christian Edet

- December 21, 2021

How Many Devices on Disney Plus?

- November 20, 2021

How Many Profiles Can You Have on HBO Max?

- by thebingeful

- October 12, 2023

21 Different Types of Theater

- April 30, 2022

Discover more from The Bingeful

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Star Trek’s Planet Classes, Explained

From M to P, how does the helpful planet classification system work?

One of the things that makes Star Trek such a successful science fiction franchise is the immense amount of world building the creators put into the various shows. Things didn’t end with cool-looking alien races. Writers and directors often created entire working socio-political infrastructures, and entire histories for the races. The same is true for the history of Earth and the humans who have evolved into the perfect representations of a utopian future pioneered in the franchise . One such seemingly minor detail was the creation and prolonged use of the planet class system.

Plant classes, or planetary classifications, were a way for the military-like Starfleet (as well as many other exterior space governing bodies) to categorize the various types of planets across the galaxy. The classification would take into account many important factors that made the planet up, including atmosphere, temperature, size, and vegetation. Of course, there was still a massive amount of variation within this, but these factors, as well as some other minor ones, were the most important. These would help give an indication as to what to expect when visiting a new or old world. It’s also important to note that these were specifically designations for planets, rather than moons, comets, or the like. Planets are defined as a body that is not only in orbit around a sun, but is also big enough ( which is why poor Pluto got demoted ). It also has to be round, and have an orbit that is fairly clear from debris.

RELATED: Star Trek: Who Are The Voth?

The Federation classification system is a simple one, and uses single letters to differentiate the different planets. Other races used the same tick list for their classifications, but often gave them different names. The pointy-eared Vulcans, for example, named the M class planets the ‘Minshara’ class — alternative name, same classification. The list of known classifications are as follows: D, H, J, K, L, M, N, R, T, P, and Y, which unfortunately doesn't make an interesting or memorable acronym.

Of all of these, the most important and frequently used is Class M , which basically denotes any planet that is Earth-like. The atmosphere of an M-Class Planet contains oxygen and usually nucleogenic particles (the thing that was necessary for the production of rain on a planet). Most notably, though, they were home planets that would support human life. The best examples of these plants from the franchise was, of course, Earth, but Vulcan and the Organian home world Organia also fall into this category. Here is where the classifications are shown to be fairly broad. There is a vast difference between the living conditions on Earth versus Vulcan, but still they are both still classified as M-class planets.

Other classes were used for planets that were uninhabitable for most species, for various reasons. Class D denotes an uninhabitable, small planet with no atmosphere. Examples of this include the Weytahn and Regula planets. What was interesting about these planets was that they were often viable candidates for terraforming, which is what happened to Weytahn, converting it from a class D planet to a class M. Class H is a fairly specific, and rarely used class, denoting planets that were uninhabitable by humans but were hospitable for the Sheliak race, one of the few non-humanoid aliens in the franchise. Class J and T planets are types of gas giants.

Class M planets are not the only habitable ones in the universe. Class K worlds were able to support human life, as long as they were using artificial biospheres. They were not naturally habitable, but could be made so with relative ease. Examples of these were Theta VIII and the wonderfully named planet Mudd. Meanwhile, the unusual Class L planets were often relatively habitable for humans, but had a strange dichotomy between flora and fauna. These worldshad a large amount of vegetation, overflowing with greenery, but had either very little or no animal life. It made these worlds oddly barren, despite all appearances, but at the same time relatively safe (discounting poisonous and deadly plants).

Other planet classes denote hostile or dangerous environments. Class N planets are a rare appearance within the shows, only being mentioned a few times. This class is given to planets with high surface temperatures, and a dense, acidic atmosphere. Here, water only exists as a vapor. In our own solar system, Venus is a prime example of a Class N planet. Class R worlds are somewhat mysterious, as the only canon example is Dakala. This classification is given to ‘rogue’ planets, ones which had somehow broken free of their orbit and managed to travel untethered by a sun through space, like a rogue starship going at warp and crashing into anything in its path.

After the iconic Class M planets, potentially the next most memorable classification is the Class Y worlds. These were aptly given the nickname of ‘Demon’ planets, and are what one might call a typical representation of hell. They are incredibly inhospitable worlds, with massively toxic atmospheres and temperatures of an unimaginable level — 500 degrees Kelvin, to be precise. They are not only dangerous to those who dared set foot on them. They were also dangerous to those just in the vicinity, prone to thermionic radiation discharges that were deadly to those nearby.

Finally, the technically non-canon Class P planets appear on various different star charts for the franchise, but are never specifically discussed in the shows or movies. The only mention is a passing comment that the technologically advanced Breen home world was likely to be a class P. These are glaciated planets, old worlds that are more than 80% ice, with human breathing air composed of oxygen and nitrogen.

That’s all the classifications to date, though with new shows getting added to the franchise constantly, it’s only a matter of time until new classifications sneak up, pretending like they’ve been there the whole time.

MORE: Star Trek: Who Was The Franchise's Most Hated Character?

Navigation menu

- Mission Logs

- Chronologies

- Library Computer

Planetary Classes

- 19 Classes S-T

- 21 References

Gothos ( TOS 18 )

Geothermal [1]

Geomorteus [1]

Psi 2000 ( TOS 06 )

Geoinactive [1]

Moon (Sol IIIa) ( ENT 96 )

Asteroid/Moon [1]

Geoplastic [1]

Janus VI ( TOS 26 )

Geometallic [1]

Delta Vega ( TOS 01 )

Geocrystalline [1]

Rigel XII ( TOS 03 )

Desert [1]

Gas Supergiant [1]

Jupiter ( DSC 15 )

Gas Giant [1]

Mars ( STSC )

Adaptable [1]

Marginal [1]

See: Class M Planets

Reducing [1]

Pelagic [1]

Exo III ( TOS 09 )

Glaciated [1]

Variable [1]

Rogue [1]

Classes S-T

Ultragiant [1]

Demon [1]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Mandel, Geoffrey . Star Trek: Star Charts . Pocket Books , 2002.

- ↑ Roddenberry, Gene ( Executive Producer ). "I, Mudd." Star Trek , Season 2, Episode 12. Directed by Marc Daniels . Written by Stephen Kandel . Desilu Productions , 3 November 1967.

- Astrometrics

- Prime Timeline

- Privacy policy

- About Trekipedia

- Disclaimers

- Login / Create Account

Class H planets

- VisualEditor

- View history

Pages in category "Class H planets"

The following 2 pages are in this category, out of 2 total.

Star Trek : Planetary Classification

Memory Beta, non-canon Star Trek Wiki

A friendly reminder regarding spoilers ! At present the expanded Trek universe is in a period of major upheaval with the continuations of Discovery and Prodigy , the advent of new eras in gaming with the Star Trek Adventures RPG , Star Trek: Infinite and Star Trek Online , as well as other post-57th Anniversary publications such as the ongoing IDW Star Trek comic and spin-off Star Trek: Defiant . Therefore, please be courteous to other users who may not be aware of current developments by using the {{ spoiler }}, {{ spoilers }} OR {{ majorspoiler }} tags when adding new information from sources less than six months old (even if it is minor info). Also, please do not include details in the summary bar when editing pages and do not anticipate making additions relating to sources not yet in release. THANK YOU

Class H planets

- View history

This category contains a list of class H desert planets .

All items (12)

- Category:Memory Beta images (class H planets)

Planet Classes

Class A - Gas Supergiant

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's outer or "cold zone". They are typically 140 thousand to 10 million kilometers in diameter and have high core temperatures causing them to radiate heat. Low stellar radiation and high planet gravity enables them to keep a tenuous surface comprised of gaseous hydrogen and hydrogen compounds.

Class B - Gas Giant

Class B Planets are usually found in a star's outer or "cold zone". They are typically 50 thousand to 140 thousand kilometers in diameter and have high core temperatures but do not radiate much heat. Low stellar radiation and high planet gravity enables them to keep a tenuous surface comprised of gaseous hydrogen and hydrogen compounds.

Class C - Reducing

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "habitable zone". They are typically 10 to 15 thousand kilometers in diameter. They have high surface temperatures due to the "greenhouse effect" caused by their dense atmospheres. The only water found is in vapor form.

Class D - Geo Plastic

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "habitable zone". They are typically 10,000 to 15,000 kilometers in diameter. They have a molten surface because they have been recently formed. The atmosphere contains many hydrogen compounds and reactive gases. Class D planets eventually cool, becoming Class E.

Class E - Geo Metallic

Planets of this class have a molten core and are usually found in a star's "habitable zone". They are typically 10,000 to 15,000 kilometers in diameter. Their atmospheres still contain hydrogen compounds. They will cool further eventually becoming Class F.

Class F - Geo Crystaline

Class F planets are usually found in a star's "habitable zone". They are typically 10 to 15 thousand kilometers in diameter and have surfaces that are still crystalizing. Their atmospheres still contain some toxic gases. They will cool eventually becoming Class C, M or N.

Class G - Desert

Planets of this class can be found in any of a star's zones. They are typically 8 to 15 thousand kilometers in diameter. Their surfaces are usually hot. Their atmospheres contain heavy gases and metal vapors.

Class H - Geo-Thermal

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "habitable zone" or "cold zone". They are typically 1,000 to 10,000 kilometers in diameter. They have partially molten surfaces and atmospheres that contain many hydrogen compounds. They cool becoming Class L.

Class I - Asteroid / Moon

Planetary bodies of this class can be found in any of a star's zones. They are usually found in orbit of larger planets or in asteriod fields. They are typically 100 to 1,000 kilometers in diameter. They have no atmospheres. Their surfaces are barren and cratered.

Class J - Geo-Morteus

Planets of this class are found in a star's "hot zone". They are typically 1,000 to 10,000 kilometers in diameter. They have high surface temperatures due to the proximty to the star. Their atmospheres are extremely tenuous with few chemically active gases.

Class K - Adaptable

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "habitable zone". They are adaptable for humanoid colonization through the use of pressure domes and other life support devices. They are typically 5,000 to 10,000 kilometers in diameter. They have thin atmospheres. Small amounts of water are present.

Class L - Geo-Inactive

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "habitable zone" or "cold zone". They are typically 1,000 to 10,000 kilometers in diameter. Low solar radiation and minimal internal heat usually result in a frozen atmosphere.

Class M - Terrestrial

Planets of this class are found in a star's "habitable zone". They are typically 10,000 to 15 thousand kilometers in diameter. They have atmospheres that contain oxygen and nitrogen . Water and life-forms are typically abundant. If water covers more than 97% of the surface, then they are considered Class N.

Class N - Pelagic

Class N planets are usually found in a star's "habitable zone". They are typically 10,000 to 15 thousand kilometers in diameter. They have atmospheres that contain oxygen and nitrogen . Water and life-forms are typically abundant. If water covers less than 97% of the surface, then they are considered Class M.

Class S - Near Star

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "cold zone". They are typically 50 million to 120 million kilometers in diameter and have high core temperatures causing them to radiate heat and light. These are the largest possible planets, because most planetary bodies that reach this size do become stars.

Class T - Gas Ultragiant

Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "cold zone". They are typically 10 to 50 million kilometers in diameter. They have high core temperatures causing them to radiate enough heat to keep water in a liquid state.

Class Y - Demon

Class Y - Demon Planets and planetoids of this class can be found in any of a star's zones. They are typically 10,000 to 15 thousand kilometers in diameter. Atmospheric conditions are often turbulent and saturated with poisonous chemicals and thermionic radiation. Surface temperatures can reach in excess of 500 K.

Starfleet Note: Communication is frequently impossible, and transport may be difficult. Simply entering orbit is a dangerous prospect. No known environment is less hospitable to humanoid life than a Class Y planetary body.

Class H planet

- Edit source

- View history

In planetary classification , a Class H planet type is usually uninhabitable by Humans , usually due to their desertic nature. In the Treaty of Armens , "unwanted lifeforms inhabiting H class worlds may be removed at the discretion of the Sheliak Corporate ."

Class H planets [ ]

- List of class H planets

External links [ ]

- Class H article at Memory Alpha , the canon Star Trek wiki.

- Class H article at Memory Beta , the non-canon Star Trek wiki.

Planet Classification: How to Group Exoplanets

With thousands of exoplanet candidates discovered, astronomers are starting to figure out how to group them in order to describe them and understand them better. Many planet classification schemes have been proposed over the years, ranging from science fiction to more scientific ones. But we still know little about exoplanets, and some scientists still debate what the definition of a planet should be.

What is a planet?

Before discussing how to classify planets, it's important to understand what a planet is. The International Astronomical Union came out with an official definition in 2006, but that definition has remained controversial. The definition states that a planet is a celestial body that

- is in orbit around the sun,

- has sufficient mass to have a nearly round shape,

- has "cleared the neighborhood" around its orbit.

The definition arose after astronomers, including California Institute of Technology astronomer Mike Brown, found several small worlds at the edge of the solar system. These bodies were approximately the size of Pluto, which was then considered a planet. With a new definition, the small worlds and Pluto were grouped into a new category called "dwarf planet."

The decision did not meet with universal approval. Alan Stern is the principal investigator of the New Horizons mission to Pluto, which flew by the world in 2015. He has repeatedly argued that the phrase " cleared the neighborhood " is vague and does not account for the fact that, for example, Earth has many asteroids in its orbit. Further, the New Horizons pictures of Pluto showed a surprisingly complex world that includes mountains, frozen lakes and other features – which he again argued makes it more like a planet.

The IAU responded to the New Horizons discoveries as follows: "These results raise fundamental questions about how a small, cold planet can remain active over the age of the Solar System. They demonstrate that dwarf planets can be every bit as scientifically interesting as planets. Equally important is that all three major Kuiper belt bodies visited by spacecraft so far – Pluto, Charon, and Triton – are more different than similar, bearing witness to the potential diversity awaiting the exploration of their realm."

In 2017, a group of scientists, including Stern, proposed a new definition of planet , which they plan to submit to the IAU: "A planet is a sub-stellar mass body that has never undergone nuclear fusion and that has sufficient self-gravitation to assume a spheroidal shape adequately described by a triaxial ellipsoid regardless of its orbital parameters."

Classifying planets

The urge to classify planets has increased since exoplanet discoveries became more frequent. The first confirmed exoplanet discovery was in 1992, with the discovery of PSR B1257+12 around a pulsar star; the first main-sequence star discovery (51 Pegasi b) was found in 1995.

Since then, thousands of exoplanet candidates have been found, most of them with the Kepler Space Telescope . While Kepler's mission is focused on finding planets like Earth orbiting in the "habitable zones" (where liquid water may exist on the planet's surface) of their stars, the telescope has discovered a wide variety of planets.

Many of the exoplanets discovered early on were so-called "hot Jupiters," large gas giants that orbit very close to their parent star. Some planets are very old, such as PSR 1620-26 b (nicknamed Methuselah as it's only 1 billion years younger than the universe itself.) Some planets are so close to their parent star that their atmosphere is evaporating , such as the case of HD 209458b. Further, planets have been found orbiting two, three or even more stars.

With such a wide range of planets, it is perhaps understandable that there is no single classification system for all planets. For the most part, astronomers focus on the degree to which planets may be habitable, which is perhaps best demonstrated with the Habitable Exoplanets Catalog . This is a list of the most promising habitable planets as determined by experts at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo's Planetary Habitability Laboratory (PHL).

The challenge is, habitability is usually defined solely by a planet's orbit and mass. Telescopes of today are not sensitive enough to look at atmospheres except for the very largest and closest planets. That said, observatories of the future may be able to examine atmospheres directly. The James Webb Space Telescope , which launches in 2018, should be capable of looking at certain planets' atmospheres, although it's unclear how much information it can obtain about smaller, rocky planets close to Earth's mass.

Solar System classification schemes

The word "planet" comes from a Greek word meaning "wanderer", meaning that the planets wander in Earth's sky compared with the (relatively fixed) stars. Planet movements were known by all ancient cultures, but they were limited to those that could be seen with the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. The discoveries of Uranus and Neptune came after the telescope was used in astronomy starting in the 1600s.

In our own solar system, astronomers typically distinguish between "rocky" planets and "gas" planets . The rocky planets are Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. They have small atmospheres compared with their size, and are closer to the sun.

Long-standing theory is that when the sun was young and the solar system was just forming , radiation blew most of the gas to the outer solar system, depriving these planets of the chance to pick up a lot of atmosphere. However, other solar systems have huge, gassy exoplanets close to their parent stars. Perhaps these exoplanets migrated, or perhaps the formation theory needs tweaking.

The gas planets in our solar system are Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, although there are vast differences among them. Uranus and Neptune still have rocky cores (as best as theory can tell), but have very large atmospheres compared with those cores. While the cores of Jupiter and Saturn also remain enigmatic, physics predicts that because of the planets' much larger size relative to Uranus and Neptune, the cores may be liquid-metallic – or perhaps more solid. More study will be needed.

At least one classification scheme distinguishes the planets in our solar system with their position relative to Earth . Under this scheme, "inferior" planets (those inside Earth's orbit) are Mercury and Venus. "Superior" planets (those outside Earth's orbit) are Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

Sometimes, planets in our solar system are classified with their position relative to the asteroid belt , which lies approximately between Mars and Jupiter. With this scenario, "inner" planets are Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. "Outer" planets are Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

Exoplanet classification schemes

Perhaps the most famous attempt at exoplanet classification is that used by "Star Trek." A habitable planet like the Earth is referred to as an M-class planet; often, members of the crew would call out that they were orbiting an M-class planet, or this would be noted specifically in a captain's log.

Star Trek fan site Memory Alpha has a class list as follows:

- Class D (planetoid or moon with little to no atmosphere)

- Class H (generally uninhabitable)

- Class J (gas giant)

- Class K (habitable, as long as pressure domes are used)

- Class L (marginally habitable, with vegetation but no animal life)

- Class M (terrestrial)

- Class N (sulfuric)

- Class R (a rogue planet, not as habitable as a terrestrial planet)

- Class T (gas giant)

- Class Y (toxic atmosphere, high temperatures)

The Planetary Habitability Laboratory lists several "obscure" examples of classification, as well as more scientific examples. Of the more scientific examples, the suggestions include using mass as a classification scheme (Stern and Levison, 2002) or the abundance of elements more important for life (Lineweaver and Robles, 2006). Stern and Levison further argue, according to PHL, that "any classification should be physically based, determinable on easily observed characteristics, quantitative, uniquely, robust to new discoveries, and be based of the fewest possible criteria."

PHL also has a proposed classification scheme that uses mass as a basis — a metric that can be obtained with today's telescopic observations. Mass can be estimated based on radial velocity measurements obtained by instruments such as the HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) spectrograph at the European Southern Observatory's La Silla 3.6m telescope. Simply put, this method measures the "tug" a planet exerts as it goes around its parent star, providing an estimate of the mass.

The PHL's proposed classification list is as follows:

Minor planets, moons and comets

- Less than 0.00001 Earth masses = asteroidan

- 0.00001 to 0.1 Earth masses = mercurian

Terrestrial planets (rocky composition)

- 0.1-0.5 Earth masses = subterran

- 0.5-2 Earth masses = terran (Earths)

- 2-10 Earth masses = superterran (super-Earths)

Gas giant planets

- 10-50 Earth masses = Neptunian (Neptunes)

- 50-5000 Earth masses = Jovian (Jupiters)

Additional resources

- IAU: Pluto and the Solar System

- PHL: Exoplanet Mass Classification (EMC)

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, " Why Am I Taller ?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

Satellites watch as 4th global coral bleaching event unfolds (image)

Happy Earth Day 2024! NASA picks 6 new airborne missions to study our changing planet

Ice-penetrating radar will help JUICE and other spacecraft find water beyond Earth

Most Popular

- 2 'Rocket cam' takes you aboard final launch of ULA's Delta IV Heavy (video)

- 3 Watch live today as NASA astronauts fly to launch site for 1st crewed Boeing Starliner mission to ISS

- 4 NASA's Fermi space telescope finds a strange supernova with missing gamma rays

- 5 Stellar detectives find suspect for incredibly powerful 'superflares'

Star Trek: Infinite

Report this post

- View history

Skalaar's shuttle on the surface of a class L planet

The surface of a class L planet in the Alpha Quadrant

The Delta Flyer orbiting an icy class L planet

The surface of Kelis' homeworld

In the Federation standard system of planetary classification , some barely habitable planets , planetoids , and moons were classified as class L . Class L worlds could have different kinds of atmospheres ranging from suitable for humanoid life to unsuited without additional means, but typically they had higher concentrations of carbon dioxide than class M worlds. ( DS9 : " The Sound of Her Voice "; VOY : " Muse ") While vegetation was common on L-class worlds, they were usually, though not always, devoid of fauna . ( TNG : " The Chase "; DS9 : " The Ascent ") According to Sylvia Tilly , class L planets were generally considered to have a breathable atmosphere but were environmentally hostile. ( DIS : " All Is Possible ") Class L planets were prime candidates for colonization and potential terraforming .

In 2153 , Skalaar and Jonathan Archer landed on a class L planet with a cloudy atmosphere to escape Kago . The landing site appeared barren and cratered, but allowed them to get out and conduct repairs to the outer hull of Skalaar's shuttle without environmental suits . ( ENT : " Bounty ")

Indri VIII was a class L planet that lacked animal life but used to be covered with deciduous plants until 2369 . That year, the USS Enterprise -D witnessed a Klingon ship destroying the planet's lower atmosphere including all life with a plasma reaction. ( TNG : " The Chase ")

The USS Olympia crashed on a class L planet in the Rutharian sector in 2371 . The sole survivor was able to survive in a cave on the planet's surface for a while, but died when she ran out of tri-ox injections that prevented carbon dioxide poisoning . ( DS9 : " The Sound of Her Voice ")

Also in 2371, the USS Voyager discovered a colony of Humans on a class L planet in the Delta Quadrant with an oxygen / argon atmosphere . The Humans were abducted by the Briori centuries earlier to be used as slave labor. However, the Human slaves revolted, overthrowing and eradicating their Briori masters. Using their former masters' technology, they established a thriving settlement; by 2371, they had a population of hundreds of thousands across three cities. The planet had steppe-like vegetation and even land that "begged to be farmed ." ( VOY : " The 37's ")

In 2373 , Odo and Quark crash-landed the USS Rio Grande on a class L planet after Odo was traveling with Quark to meet a Federation Grand Jury . The crash site was dominated by steep, forested mountains, poisonous vegetation, and lacked animal life. ( DS9 : " The Ascent ")

In an alternate 2375 , the USS Voyager crash-landed on a class L planet dominated by glaciers near the border of the Alpha Quadrant . This timeline was replaced by a new one when Harry Kim sent a message from fifteen years in the future back to this year. ( VOY : " Timeless ")

A riddle presented by Neelix to Tuvok in 2376 contained the story of " a lone ensign finds himself stranded on a class L planetoid with no rations . His only possession, a calendar . When Starfleet finds him twelve months later, he's in perfect health. Why didn't he starve to death ?" Tuvok suggested that such a planetoid might contain hot water springs. ( VOY : " Riddles ")

B'Elanna Torres crash-landed the Delta Flyer on a class L planet in 2376 and was stranded there for several days, but Harry Kim finally reached her after walking two hundred kilometers with the part she needed to contact Voyager . The planet was home to a pre-warp civilization and contained at least one body of water while the area around the crash site was mountainous, densely forested, and even hosted some sort of hunting game. ( VOY : " Muse ")

In 2378 , a class L planet was found by Overlookers Nar and Zet as a settlement site for the crew of the USS Voyager after they confiscated their warp core . ( VOY : " Renaissance Man ")

Kokytos , one of Theta Helios ' many moons , was a class L world with an icy climate. The moon was prone to spider lightning discharges and was also home to predatory Tuscadian pyrosomes . ( DIS : " All Is Possible ")

- 1 List of class L worlds

- 2.1 Background information

- 2.2 External link

List of class L worlds [ ]

Appendices [ ], background information [ ].

Kelis' homeworld , as seen in "Muse", appeared somewhat atypical of a class L planet as it contained at least one region that supported lush vegetation and even a pre-warp civilization . Although Harry Kim traversed two hundred kilometers of the planet's surface by foot without any visible life-sustaining equipment, little was seen of the planet's surface and the remainder of the planet might have been far less hospitable and more standard for a class L planet.

According to the Star Trek: Star Charts , on page 25, class L planets were "marginal" planets. They had ages that ranged from four to ten billion years and diameters between 10,000 and 15,000 kilometers. Marginal planets were located within the ecosphere of a star system . They were categorized by a rocky and barren surface with little surface water and an atmosphere of oxygen/argon with a high concentration of carbon dioxide . Native lifeforms were limited to plant life, although the majority of class L planets were suitable for humanoid colonization .

External link [ ]

- Class L at Memory Beta , the wiki for licensed Star Trek works

- 3 ISS Enterprise (NCC-1701)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

According to the Star Trek: Star Charts, on page 24, class H worlds had an age of four to ten billion years and had a diameter ranging from 8,000 to 15,000 kilometers.They were found throughout star systems.These desert planets were categorized by a hot and arid surface, with little or no surface water and an atmosphere that might contain heavy gasses and metal vapors.

The class H designation in Star Trek canon was vague, though largely uninhabitable by most humanoid species. One exception was the Sheliak, an "R-3" lifeform consisting of what appeared to be sentient blobs. They laid claim over several Class H worlds, which the Federation ceded to them as part of a treaty.

The Class M (or Minshara-class) planet is the most stable type for humanoid habitation. Class M planets may feature large areas of water, if water or ice covers more than 80% of surface then the planet is considered Class O or Class P. Class N Reducing.

The Star Trek: Star Charts book, which was authored and advised by Trek staffers, listed many other planetary classes which may one day be recognized on-screen, but as of now they remain conjectural. ... According to the Star Charts, a class P planet is a "glaciated" planet. They have an age that ranges from three to ten billion years and a ...

Exception: For Class M, there are just a number of examples from a total of probably over a hundred planets. I am aware that the classification system has been consistently supplemented in the book Star Trek Star Charts by Geoffrey Mandel to include several more letters, but that is non-canon. List of Canon Planet Classes

A planet is considered Class H if less than 20% of its surface is water. Though many Class H worlds are covered in sand, it is not required to be considered a desert; it must, however, receive little in the way of precipitation. Drought-resistant plants and animals are common on Class H worlds, and many are inhabited by humanoid populations.

According to Star Trek: Star Charts, a class T planet is a gas giant classified as a "large ultra giant," 50,000,000 to 120,000,000 kilometers in diameter, with an age of two to ten billion years. These planets are typically composed of hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of heavier elements. A system of moons and rings often surrounds ...

Star Trek's Planet Classes, Explained. By Alice Rose Dodds ... converting it from a class D planet to a class M. Class H is a fairly specific, and rarely used class, ...

Class H. Rigel XII (TOS 03) Desert. Age 4-10 billion years Diameter 10,000-15,000km Location ... Mars, Planet Mudd ... Star Trek, Season 2, Episode 12. Directed by Marc Daniels. Written by Stephen Kandel. Desilu Productions, 3 November 1967.

The Planet Classification System was developed by the Federation as a means of conveniently categorizing planets using a uniform criteria consisting of a number of elements including, but not limited to: atmospheric composition, age, surface temperature, size, and the presence of life. The system uses the Terran alphabet, more specifically the Latin alphabet to designate the different ...

Class H planets Category page. Edit VisualEditor View history Talk (0) Pages in category "Class H planets" The following 2 pages are in this category, out of 2 total. B. Bajor VII; K. Kassae II; Categories ... Star Trek Online Wiki is a FANDOM Games Community. View Mobile Site

Home Pages Star Trek : Planetary Classification. Source (s): Memory Alpha. Star Treh the Final Frontier.

A Class H planet is a planet that is hot and arid with little or no water. (ST reference: Star Charts) Rigel XII Tau Cygna V ... Star Trek: Infinite and Star Trek Online, as well as other post-57th Anniversary publications such as the ongoing IDW Star Trek comic and spin-off Star Trek: Defiant.

A friendly reminder regarding spoilers!At present the expanded Trek universe is in a period of major upheaval with the finale of Picard and the continuations of Discovery, Lower Decks, Prodigy and Strange New Worlds, the advent of new eras in Star Trek Online gaming, as well as other post-56th Anniversary publications such as the new ongoing IDW comic.

This category lists class H planets. Star Trek Expanded Universe. Explore. Main Page; All Pages; Community; Interactive Maps; ... Class H planet; D Devos II; I Ircassia III; Ircassia IV; K Ka'al; Kahara III; R Rigel XII; S Starbase 7; Y ... Star Trek Expanded Universe is a FANDOM TV Community.

Class H - Geo-Thermal. Planets of this class are usually found in a star's "habitable zone" or "cold zone". They are typically 1,000 to 10,000 kilometers in diameter. They have partially molten surfaces and atmospheres that contain many hydrogen compounds. They cool becoming Class L. Class I - Asteroid / Moon. Planetary bodies of this class can ...

In the Federation standard system of planetary classification, a class Y planet was characterized by a toxic atmosphere, sulfuric deserts, surface temperatures exceeding five hundred Kelvin, and thermionic radiation discharges. ... Information taken from Star Trek: Star Charts indicates class Y worlds have an age between two and ten billion ...

In planetary classification, a Class H planet type is usually uninhabitable by Humans, usually due to their desertic nature. In the Treaty of Armens, "unwanted lifeforms inhabiting H class worlds may be removed at the discretion of the Sheliak Corporate." List of class H planets Class H article at Memory Alpha, the canon Star Trek wiki. Class H article at Memory Beta, the non-canon Star Trek wiki.

An artist's impression of the first planet orbiting a sunlike star beyond the solar system, 51 Pegasi b, a massive gas giant orbiting its planet every 4 days. (Image credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser/Nick ...

Star Trek: Infinite. All Discussions Screenshots Artwork Broadcasts Videos Workshop News Guides Reviews ... I'm not sure it i terraformed H class planet, but I would expect such behavior . You terraform planets to to have better habitability, but in trade-off of available resources. For planets those would be districts, since in this game you ...

According to the non-canon publication Star Trek: Star Charts, class K planets are called "adaptable". These planets have an age that ranges from four to ten billion years and a diameter that ranges from 5,000 to 10,000 kilometers. A class K planet is found within the ecosphere of a star system.

Class M planet. In the Star Trek universe, a Class M planet is one habitable by humans and similar life forms. Earth, Vulcan, Romulus, and Qo'noS are examples of Class M planets. [1] The planet needs an atmosphere of oxygen and nitrogen, should be close to a stable star, have fertile soil, a tolerable gravity, a climate that is generally ...

That icon is an undiscovered card. 2 class H planets have a single undiscovered card as a reward, 2 have two undiscovered cards, 1 has an undiscovered card and advanced action card, and 1 has an undiscovered card plus 3 data crystals. The others have rewards which don't include undiscovered cards.

Although Harry Kim traversed two hundred kilometers of the planet's surface by foot without any visible life-sustaining equipment, little was seen of the planet's surface and the remainder of the planet might have been far less hospitable and more standard for a class L planet. According to the Star Trek: Star Charts, on page 25, class L ...