Situation in Haiti April 13, 2024

U.s. citizens in haiti, update april 12, 2024, information for u.s. citizens in the middle east.

- Travel Advisories |

- Contact Us |

- MyTravelGov |

Find U.S. Embassies & Consulates

Travel.state.gov, congressional liaison, special issuance agency, u.s. passports, international travel, intercountry adoption, international parental child abduction, records and authentications, popular links, travel advisories, mytravelgov, stay connected, legal resources, legal information, info for u.s. law enforcement, replace or certify documents.

Share this page:

Ghana Travel Advisory

Travel advisory november 20, 2023, ghana - level 2: exercise increased caution.

Updated to reflect threats against LGBTQI+ travelers.

Exercise increased caution in Ghana due to crime and violence against members of the LGBTQI+ community . Some areas have increased risk. Read the entire Travel Advisory.

Exercise increased caution in:

- Parts of the Bono East, Bono, Savannah, Northern, North East, and Upper East regions due to civil unrest.

Country summary: Violent crimes, such as carjacking and street mugging, do occur. These crimes often happen at night and in isolated locations. Exercise increased caution specifically due to crime:

- In urban areas and crowded markets

- When traveling by private or public transportation after dark as criminal elements may use blockades to slow down and restrict movement of vehicles

- In areas near the northern border in the Upper East and Upper West regions

The U.S. government has limited ability to provide emergency services to U.S. citizens. Local police may lack the resources to respond effectively to more serious crimes.

LGBTQI+ Travelers: Ghanaian law contains prohibitions on “unlawful carnal knowledge” – generally interpreted as any kind of sexual intimacy – between persons of the same sex. Punishments can include fines and/or incarceration. Anti-LGBTQI+ rhetoric and violence have increased in recent years. Members of the LGBTQI+ community have reported safety incidents that include targeted assault, rape, mob attacks, and harassment due to their identity.

Read the country information page for additional information on travel to Ghana.

If you decide to travel to Ghana:

- See our LGBTQI+ Travel Information page and section 6 of our Human Rights Report for further details.

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program ( STEP ) to receive alerts and make it easier to locate you in an emergency.

- Follow the Department of State on Facebook and Twitter .

- Review the Country Security Report for Ghana.

- Prepare a contingency plan for emergency situations. Review the Traveler’s Checklist .

- Visit the CDC page for the latest Travel Health Information related to your travel.

Areas Near the Northern Border in the Upper East and Upper West Regions – Level 2: Exercise Increased Caution

U.S. citizens traveling in Ghana should exercise caution while visiting border areas, in particular the northern border, and be sure to read Security Alerts affecting those areas. Due to security concerns over criminal activity in remote areas, travel of U.S. government personnel to the northern and northwestern border is currently limited.

Visit our website for Travel to High-Risk Areas .

Travel Advisory Levels

Assistance for u.s. citizens, search for travel advisories, external link.

You are about to leave travel.state.gov for an external website that is not maintained by the U.S. Department of State.

Links to external websites are provided as a convenience and should not be construed as an endorsement by the U.S. Department of State of the views or products contained therein. If you wish to remain on travel.state.gov, click the "cancel" message.

You are about to visit:

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

Good resources that provide current information about the infections that occur in various geographic areas are essential [ 2-4 ]. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website includes an online version of Health Information for International Travel under Travelers' Health and updates on travel-related infections [ 4,5 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) website also has regularly updated information about outbreaks.

The approach to evaluation of illness associated with travel to West Africa will be reviewed here.

Issues related to travel to other regions are discussed separately:

● (See "Diseases potentially acquired by travel to East Africa" .)

A Guide to Travel Restrictions Throughout Africa

By Sarah Khan

Many predicted dire consequences when COVID-19 made its way across Africa , but the case numbers in African countries have largely remained low, especially in contrast with the United State s and Europe .

Experts have posited that factors like climate, strict lockdown, the continent’s relatively young population (more than 60 percent of Africans are under 25), and preparation measures already in place for other outbreaks may have all played a role.

But case counts, as well as government responses, have varied across the continent. South Africa has been the continent’s worst-affected country, accounting for nearly half the deaths despite a rather strict lockdown, and now a new, more infectious variant ; Rwanda, which has also implemented strict measures, has reported just over 200 deaths; while Tanzania stopped releasing official numbers after April and resumed international travel early, with surprisingly relaxed measures.

Many African nations are welcoming foreign travelers again, but quite a few exclude visitors from America. On the flip side, the United States has recently added South Africa to its COVID travel restrictions, meaning that non-U.S. citizens (including residents), may not enter the country if they were in South Africa within the 14 days prior. If you do decide to travel, be conscientious about not overburdening the local health systems. Stay on top of each country’s rules—which are subject to change based on rising case numbers—and wear masks , practice social distancing, and sanitize regularly.

Northern Africa

As of July, Egypt has been open to international travelers. All visitors must present printed results from a negative PCR test taken within 96 hours of entry, and must fill out a Public Health Card for contact tracing on arrival. Anyone flying directly into Hurghada, Sharm El Sheikh, Marsa Alam, or Taba who doesn’t have a PCR test must test on arrival and stay in their hotel room until the results are available. All indoor events are canceled, and restaurants and cafes are operating at 50 percent capacity.

Though Morocco began lifting travel restrictions in September, the country is under a new state of emergency, with a nationwide curfew.

Morocco , which began lifting restrictions in September, has since instated a Health State of Emergency until February 10 at the earliest and implemented a nationwide curfew. Under that, restaurants, cafes, shops, and supermarkets throughout the country close at 8 p.m.

Travelers from visa-exempt countries—including the U.S.—with confirmed hotel reservations are allowed, as are business travelers invited by Moroccan companies. Visitors must have a negative PCR test taken less than 72 hours before departure, with printed results to be presented at check in and health screenings at the port of entry. The rules change frequently and can make travel within Morocco a challenge.

East Africa

One of the first African countries to open widely for tourism, back in June, was Tanzania . At the time, there were no testing or quarantine requirements. That was changed in August to require a negative PCR test taken within 72 hours of travel, but the rule was later lifted in September. Now only enhanced screenings (and testing on arrival, if deemed necessary) are required. That said, your airline will likely require a negative PCR test to board, so it’s best to get tested regardless of changing rules. Keep in mind that the Tanzanian government has not released any of its COVID-19 statistics since April, so accurate information about the impact of the pandemic on locals is not readily available. The U.S. has also given the destination a Level 4 travel warning , saying “travelers should avoid all travel to Tanzania” due to a “very high level of COVID-19.”

Tanzania was one of the first African countries to reopen for tourism, though the U.S. government warns travelers against visiting right now.

Kenya reopened its borders to international travelers—Americans included—in August. As of February, all travelers must present a digitally verified COVID test through the Trusted Traveler program . Group gatherings are banned throughout the country, with the exception of funerals and weddings, which are allowed to host up to 150 people .

Arati Menon

Hannah Towey

Maya Silver

Rwanda is open to travelers, but you'll have to jump through some hoops before you can go gorilla trekking . First, fill out Rwanda’s passenger locator form online —you’ll have to upload a negative PCR test taken less than 120 hours before departure, along with your hotel reservation. A second PCR test is administered upon arrival in Kigali (at a cost of $50, plus a $10 medical services fee), and you’ll quarantine in your hotel room at your own expense until the results come back within 24 hours. To enter Volcanoes , Nyungwe , or Akagera national parks, you’ll have to submit a registration and indemnity form prior to arrival (ask your local tour operator for this), and also test negative within 72 hours of your park visit. Travelers must test negative once again before departure.

Uganda reopened borders October 1 with new safety measures: a negative PCR test issued within 120 hours of travel is required. Officials recommend arriving at the airport four hours prior to your flight to clear all medical screenings. In addition to regulated social distancing around other people, visitors to Uganda’s national parks must stay at least 32 feet away from gorillas during sightings.

Visitors to Ethiopia can fly into Addis Ababa Bole International Airport’s brand-new $300 million contactless, biosafety-focused airport terminal —but to do so, you’ll need to present a negative PCR test taken within five days of arrival in Ethiopia. Even with the negative test, all visitors must self-isolate at a hotel for seven days.

Indian Ocean islands

Seychelles has been slowly reopening to international travel, but Americans have not yet made the cut—except for those who are fully vaccinated. Anyone who’s received both doses of the vaccination is welcome from anywhere in the world, provided they show proof of vaccination and they’re traveling more than two weeks after their second dose. A negative PCR test within 72 hours is still required. The country projects that the majority of Seychelles’ adults will be vaccinated by mid-March, which is when they plan to open fully for international tourism.

Southern Africa

South Africa recorded the highest number of COVID-19 cases in Africa—more than half of the total numbers on the continent. The country began reopening its borders to Americans in November, requiring a negative PCR test taken within 72 hours of arrival and the use of a COVID tracing app. Travelers must also fill out a health questionnaire two days prior to arriving and two days prior to departing. The emergence of a new variant in recent weeks has caused concerns. Last week, Biden added South Africa to a list of restricted countries (though U.S. citizens can return from South Africa), and there’s now a national lockdown in place from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m.

U.S. citizens will be permitted enter Zambia upon presenting a negative PCR test result taken within seven days of departure. You can apply for an e-visa online . Travelers to Zimbabwe must present a negative COVID-19 PCR test taken within 48 hours of departure, but should be aware that a new, strict lockdown began this month, which prohibits all gatherings, the closure of non-essential businesses, and a 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew. For Namibia , a negative PCR test taken 72 hours before arrival is required; if your test was taken more than 72 hours but less than one week before arrival, you’ll have to undergo supervised isolation at a government-approved hotel for seven days.

West Africa

Arriving in Ghana is a two-test process: First, you need a negative PCR test result from within 72 hours of departure in hand; then, you'll head to a new state-of-the-art lab that has been set up at Accra’s Kotoka International Airport for mandatory antigen tests at each travelers’ own expense ($150). Results typically arrive within 15 minutes, though the test must be paid for online in advance.

Nigeria reopened in September with strict testing protocols. Travelers must upload proof of a negative PCR test taken within 96 hours before boarding their flight to receive a QR code with a Permit to Travel certificate; both this and the negative PCR test must be shown in order to board any flight to Nigeria, and then again on arrival. After seven days, a second PCR test must be taken at the traveler's expense (ranging from about $112 to $132). Before traveling to Nigeria, visit the country’s travel portal to fill out a health questionnaire, upload your first negative PCR test result, and schedule and pay in advance for your second test.

All travelers to Senegal must present a negative PCR test dated within five days of arrival, as well as submit a passenger locator form . While some public spaces, like bars and theaters, remain closed, restaurants, private beaches, and markets are partially open with social distancing measures in effect, and a nightly curfew from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m.

This article was originally published in November 2020. It has been updated with new information. We’re reporting on how COVID-19 impacts travel on a daily basis. Find our latest coronavirus coverage here , or visit our complete guide to COVID-19 and travel .

Recommended

Royal Mansour Casablanca: First In

andBeyond Phinda Forest Lodge: First In

Africa Travel Guide

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Traveller. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

CDC to monitor travelers from West Africa for 21 days

shulz / iStock

In a move designed to further enhance air-traveler Ebola screening, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) today announced a program to monitor all passengers arriving from the three outbreak countries for 21 days after they arrive.

The move comes a day after the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced that all air travelers arriving from Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone would be funneled through five airports that are already doing enhanced screening, such as temperature checks and questions about exposure to the virus.

CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, said at a media briefing today that the 21-day monitoring will affect all of the approximately 150 people that arrive in the United States from the three countries every day, most of whom are Americans or people from the region who are longtime legal residents of the United States. Outbreak responders, journalists, and even the CDC's own employees are among the targets of the new screening step.

"We'll continue to do whatever we can to reduce the risk to Americans," Frieden said. The new measure has been in the works for some time and represents the next step in the process to boost the country's guard against Ebola, he added.

Steps will begin Oct 27

The new steps will require the involvement of state and local public health departments, which will be involved in actively monitoring the incoming travelers, who must take their temperatures twice a day and report the findings to authorities once a day, the same monitoring protocol used in Nigeria, which a few days ago was declared free of virus transmission, Frieden said.

Post-arrival monitoring will begin Oct 27 in six states that account for 70% of incoming travelers from the outbreak area: New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, New Jersey, and Georgia. Other states will start the process in the following days, according to the CDC. Frieden said some states see very few travelers from the region, so the number of travelers who will be monitored will vary widely by state.

In advance of the new monitoring process, states will need to have an around-the-the-clock phone number that travelers can call to report their temperatures or any symptoms they are having, Frieden said. States must also have a procedure to evaluate patients, a plan to transport them, and a system for how the travelers will be monitored, such as through Skype, FaceTime, or even through an employee health program, similar to what the CDC does to monitor its employees who return from the outbreak area.

Frieden said that the CDC will have technical and resource assistance for states.

Travelers will report in daily about any intent to travel, and if they don't report in every day, health departments will take immediate steps to locate them to resume daily monitoring and reporting. People who had high-risk exposure to the virus will be quarantined and barred from commercial travel. People who have symptoms will be isolated and directed to a local hospital that has been trained to receive and evaluate possible Ebola patients, the CDC said.

Each traveler will be given a care kit that includes a thermometer, a log sheet for recording temperatures, pictorial descriptions of the disease, a wallet card with information on whom to call, and other resources.

US patient updates

In other outbreak news, a photojournalist who was infected with Ebola in Liberia while working with NBC was released from the hospital today after tests showed that he was free of the virus.

Ashoka Mukpo, age 30, was hospitalized at Nebraska Medical Center on Oct 6. During his treatment he received convalescent serum from US Ebola survivor Kent Brantley, MD, and the experimental antiviral drug brincidofovir.

His medical team said at a briefing today that it's not clear if the supportive care, serum, or experimental drug played the key role in his recovery, and that tests are still being done to assess the impacts of the interventions, according to the hospital's Twitter feed.

In a statement released by the hospital today, Mukpo praised the care he received and said, "Today is a joyful day for my family and I. After enduring weeks where it was unclear whether I would survive, I'm walking out of the hospital on my own power, free from Ebola." He said he would discuss the details of his illness and treatment later with the press.

His doctors said Mukpo will have prolonged weakness, similar to that of other infections such as flu or mononucleosis. They said he was released 1 day sooner than the first Ebola patient treated at the hospital, Rick Sacra, MD.

Meanwhile, the condition of Nina Pham, the first nurse infected with Ebola while caring for the nation's first Ebola patient in Dallas, has been upgraded from fair to good, according to a statement yesterday from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Pham was transferred from Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on Oct 16 to the NIH Clinical Center Special Clinical Studies Unit, one of four US specialty units designed for treating rare and highly contagious diseases.

A second infected nurse infected at the same Dallas hospital, Amber Joy Vinson, is being treated at another one of the high-containment units, at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

Vaccine progress

A phase 1 trial of a second investigational Ebola vaccine is under way at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., the agency said in a statement today. The vaccine, called VSV-EBOV, was developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada and has been licensed to NewLink Genetics Corp, based in Ames, Iowa. It uses an Ebola virus protein spliced into a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV).

The early trial is designed to assess the safety and immunogenicity of a two-dose prime-boost strategy in healthy adults. A similar trial to test a single-dose strategy for the vaccine is also under way at the Walter Reed Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md.

The two-dose trial at NIH will enroll 39 healthy adults ages 18 to 65, randomized to one of three groups receiving a different, escalating dose. In each group, 10 will receive the vaccine and 3 will be injected with a placebo. Participants will receive their first dose or placebo, followed by another 28 days later. Study enrollment is staggered, beginning with the lowest dose, allowing researchers to assess safety before moving to the next dose level.

The one-dose trial at Walter Reed will assess the safety of the vaccine at different dosage levels, with initial results expected by the end of 2014.

Responding to recent concerns that progress on the VSV-EBOV could move too slowly because NewLink might be too small and unfamiliar with Ebola vaccines to move research and production forward rapidly, the company's chief executive scientific officer, Charles Link, MD, said there haven't been delays and that the process would be dangerous if things were progressing any faster, the Canadian Press reported today.

He said the company has a batch of vaccine that is close to being ready and that it is working with two European contract manufacturers to make more. Link told the Canadian Press that the company expects to have 60,000 to 70,000 vials of vaccine by the end of the year, which—depending on the dose needed—could be enough for between 600,000 to 700,000 doses or 6 million to 7 million doses.

Link added that plans are in the works to skip phase 2 trials and progress to phase 3 trials in Liberia and Sierra Leone in early 2015.

The first trial of an investigational Ebola vaccine began in September, involving a vaccine developed by the NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and GSK called ChAd3. Early trial data are expected by the end of the year.

In other Ebola vaccine developments, Johnson & Johnson today announced it has committed $200 million to speed the development and production of an Ebola vaccine regimen that involves its Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies.

The vaccine regimen, developed during work with the NIH, combines a Janssen preventive vaccine with one made by Danish company Bavarian Nordic. The combination has shown promise in preclinical studies and will begin phase 1 trials in the United States, Europe, and Africa in January.

In September the two companies said they would speed the development and testing of the prime-boost vaccine regimen.

The two vaccine components are Crucell's AdVac technology and Bavarian Nordic's MVA-BN technology. The companies have been collaborating on a monovalent vaccine targeting the Zaire strain of the Ebola virus, the one responsible for West Africa's outbreak, as part of ongoing work to develop a multivalent vaccine.

Paul Stoffels, MD, Johnson & Johnson's chief scientific officer, said in a statement that the company's goal is to produce more than a million vaccine doses over the next few months.

Other developments

- Texas Gov Rick Perry yesterday announced that the state would create a state-of-the-art Ebola treatment and infectious disease containment facility in Richardson, Tex., part of the initial recommendations of a task force recently put in place to better protect health workers and respond to infectious disease threats, according to a statement. Also, the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in Galveston was designated as another Ebola treatment and infectious disease containment facility. Three providers will set up the facility in Richardson: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Methodist Hospital System, and Parkland Hospital System. It will be located on the floor of the Methodist Campus for Continuing Care, which has an intensive care unit wing that can handle infectious disease cases.

- Joanne Liu, MD, international president of Doctors without Borders (MSF), said yesterday in an interview with the Canadian Press that the world should move away from assigning blame for the slow response to West Africa's Ebola epidemic and focus instead on the fixing the problem now. She was referring to a recent Associated Press story, which cited a draft of a World Health Organization (WHO) report that harshly criticized the agency's own early response to the outbreak. She said help is arriving in the region, but delivering on promises is slow and can take 6 to 8 weeks. She said MSF is urging nations to follow through on pledges they made in September during special United Nations meetings.

Oct 22 CDC statement

Nebraska Medical Center Twitter feed

Oct 21 NIH statement on Pham

Oct 22 NIH statement on Ebola vaccine trial launch

Oct 22 Canadian Press story on Ebola vaccine

Oct 22 Johnson & Johnson statement

Oct 21 Texas governor's office press release

Oct 21 Canadian Press story on MSF president

Related news

Ebola vaccine cut deaths in half during drc outbreak, study shows.

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever infects health workers in Pakistan outbreak

Equatorial Guinea's Marburg virus outbreak declared over

Health worker among deaths in Tanzania's Marburg outbreak

Uganda declares end to Ebola outbreak

Report: Pharma firms must boost access for LMICs, R&D for pandemic threats

This week's top reads

Wisconsin confirms another county affected by cwd in deer.

The 3-year-old buck was found dead in the town of Wautoma, within 10 miles of the Marquette and Portage county borders.

Officials warn of H5N1 avian flu reassortant circulating in parts of Asia

The virus is a reassortant between the older H5N1 clade (2.3.2.1c), still circulating in parts of Asia, and a newer H5N1 clade (2.3.4.4b) that began circulating globally in 2021.

Vietnam reports its first human infection from H9 avian flu virus

The patient lived adjacent to a poultry market, but there were no reports of bird illnesses or deaths.

Avian flu detected in North Carolina dairy herd

Seven states have now reported the virus in dairy herds, with detections at 21 facilities.

Blood donor study finds 21% incidence of long-term symptoms attributed to COVID-19

Among blood donors with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, 23.6% reported long-term neurologic symptoms.

Study: Pathogens that cause surgical infections may be coming from patients' skin

The study authors say the findings could have implications for infection-prevention strategies.

No need to avoid exercise with long-COVID diagnosis, researchers say

Participants with long COVID had a 21% lower peak volume of oxygen consumption at baseline.

Study identifies inflammation and symptom patterns in long COVID

Inflammation of myeloid cells and activation of immune proteins that are part of the complement system stood out blood from long COVID patients, but it's not clear if that applies to all types of long COVID.

Avian flu virus detected in South Dakota dairy herd

Today's announcement raises the number of affected states to 8.

Three studies spotlight long-term burden of COVID in US adults

One study found that veterans were at 44% higher risk of a preventable hospitalization in the year after infection.

Our underwriters

Unrestricted financial support provided by.

- Antimicrobial Resistance

- Chronic Wasting Disease

- All Topics A-Z

- Resilient Drug Supply

- Influenza Vaccines Roadmap

- CIDRAP Leadership Forum

- Roadmap Development

- Coronavirus Vaccines Roadmap

- Antimicrobial Stewardship

- Osterholm Update

- Newsletters

- About CIDRAP

- CIDRAP in the News

- Our Director

- Osterholm in the Press

- Shop Merchandise

NICHOLAS A. RATHJEN, DO, AND S. DAVID SHAHBODAGHI, MD, MPH

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):396-403

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Approximately 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030, and 66% of travelers will develop a travel-related illness. Most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require significant intervention; others could cause significant morbidity or mortality. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken, the travel itinerary, and a list of all geographic locations visited. Inquiries should also be made about pretravel preparations, such as chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and any personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing. Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections. The two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving at home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks. The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections. Localizing symptoms such as fever with respiratory, gastrointestinal, or skin-related concerns may aid in identifying the underlying etiology.

Globally, it is estimated that 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030. 1 Although Europe is the most common destination, tourism is increasing in developing regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. 2 Less than one-half of U.S. travelers seek pretravel medical advice. It is estimated that two-thirds of travelers will develop a travel-related illness; therefore, the ill returning traveler is not uncommon in primary care. 3 Although most of these illnesses are minor and relatively insignificant clinically, the potential exists for serious illness. The advent of modern and interconnected travel networks means that a rare illness or nonendemic infectious disease is never more than 24 hours away. 4 Travelers over the past 10 years have contributed to the increase of emerging infectious diseases such as chikungunya, Zika virus infection, COVID-19, mpox (monkeypox), and Ebola disease. 3

Although most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require medical evaluation, others could be life-threatening. 5 The challenge for the busy physician is successfully differentiating between the two. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Travelers at the highest risk are those visiting friends and relatives who stay in a country for more than 28 days or travel to Africa. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks. 3 , 6 The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections. 7 , 8 The incubation period of an illness relative to the onset of symptoms and the length of stay in the foreign destination can exclude infections in the differential diagnosis ( eTable A ) .

General questions should determine the patient’s pertinent medical history, focusing on any unique factors, such as immunocompromising illnesses or underlying risk factors for a travel-related medical concern. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken and the travel itinerary that includes accommodations, recreational activities, and a list of all geographic locations visited ( Table 1 3 , 6 , 9 and Table 2 3 , 6 ) . Patients should be asked about any medical treatments received in a foreign country. Modern travel itineraries often require multiple stopovers, and it is not uncommon for the casual traveler to visit several locations with different geographically linked illness patterns in a single trip abroad.

Travel History

Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections. 10 , 11 These travelers rarely seek pretravel consultation, are less likely to take chemoprophylaxis, and engage in more risky travel-related behaviors such as consuming food from local sources and traveling to more remote locations. 3 Overall, travelers visiting friends and relatives tend to have extended travel stays and are more likely to reside in non–climate-controlled dwellings.

During the clinical history, inquiries should be made about pretravel preparations, including chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing. 12 , 13 Accurate knowledge of previous preventive strategies allows for appropriate risk stratification by physicians. Even when used thoroughly, these measures decrease the likelihood of certain illnesses but do not exclude them. 6 Adherence to dietary precautions and pretravel immunization against typhoid fever do not necessarily eliminate the risk of disease. Travelers often have no control over meals prepared in foreign food establishments, and the currently available typhoid vaccines are 60% to 80% effective. 14 Although all travel-related vaccines are important, the two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A. 12 , 15

Travel duration is also an important but often overlooked component of the clinical history because the likelihood of illness increases directly with the length of stay abroad. The longer travelers stay in a non-native environment, the more likely they are to forego travel precautions and adherence to chemoprophylaxis. 3 The use of personal protective measures decreases gradually with the total amount of time in the host environment. 3 A thorough medical and sexual history should be obtained because data show that sexual contact during travel is common and often occurs without the use of barrier contraception. 16

Clinical Assessment

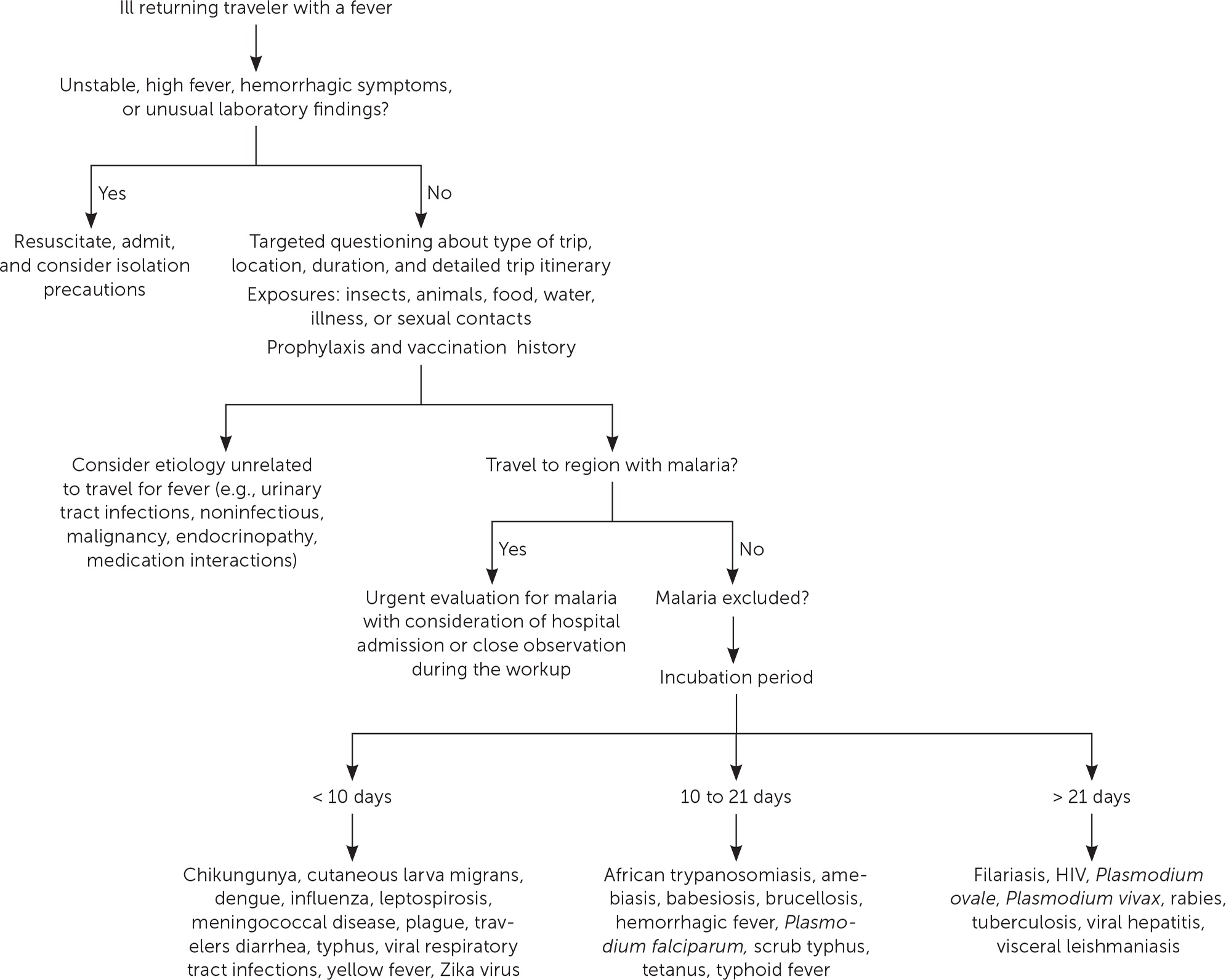

The severity of the illness helps determine if the patient should be admitted to the hospital while the evaluation is in progress. 3 Patients with high fevers, hemorrhagic symptoms, or abnormal laboratory findings should be hospitalized or placed in isolation ( Figure 1 ) . For patients with a higher severity of illness, consultation with an infectious disease or tropical/travel medicine physician is advised. 3 Patients with symptoms that suggest acute malaria (e.g., fever, altered mental status, chills, headaches, myalgias, malaise) should be admitted for observation while the evaluation is expeditiously completed. 13

Many tools can assist physicians in making an accurate diagnosis. The GeoSentinel is a worldwide data collection network for the surveillance and research of travel-related illnesses; however, this service requires a subscription. The network can guide physicians to the most likely illness based on geographic location and top diagnoses by geography. 4 For example, Plasmodium falciparum malaria is the most common serious febrile illness in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. 17

Ill returning travelers should have a laboratory evaluation performed with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and C-reactive protein. Additional testing may include blood-based rapid molecular assays for malaria and arboviruses; blood, stool, and urine cultures; and thick and thin blood smears for malaria. 3 Emerging polymerase chain reaction technologies are becoming widely available across the United States. Multiplex and biofilm array polymerase chain reaction platforms for bacterial, viral, and protozoal pathogens are now available at most tertiary health care centers. 4 Multiplex and biofilm platforms include dedicated panels for respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses and bloodborne pathogens. These tests allow for real-time or near real-time diagnosis of agents that were previously difficult to isolate outside of the reference laboratory setting.

Table 3 lists common tropical diseases and associated vectors. 3 , 6 , 18 Physicians should be aware of unique and emerging infections, such as viral hemorrhagic fevers, COVID-19, and novel respiratory pathogens, in addition to common illnesses. Testing for infections of public health importance can be performed with assistance from local public health authorities. 19 In cases of short-term travel, previously acquired non–travel-related conditions should be on any list of applicable differential diagnoses. References on infectious diseases endemic in many geographic locations are accessible online. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Travelers’ Health website provides free resources for patients and health care professionals at https://www.cdc.gov/travel .

Febrile Illness

A fever typically accompanies serious illnesses in returning travelers. Patients with a fever should be treated as moderately ill. One barrier to an accurate and early diagnosis of travel-related infections is the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms of illness. Often, these symptoms are vague and nonfocal. A febrile illness with a fever as the primary presenting symptom could represent a viral upper respiratory tract infection, acute influenza, or even malaria, typhoid, or dengue, which are the most life-threatening. According to GeoSentinel data, 91% of ill returning travelers with an acute, life-threatening illness present with a fever. 20 All travelers who are febrile and have recently returned from a malarious area should be urgently evaluated for the disease. 13 , 21 Travelers who have symptoms of malaria should seek medical attention, regardless of whether prophylaxis or preventive measures were used. Suspicion of P. falciparum malaria is a medical emergency. 13 Clinical deterioration or death can occur in a malaria-naive patient within 24 to 36 hours. 22 Dengue is an important cause of fever in travelers returning from tropical locations. An estimated 50 million to 100 million global cases of dengue are reported annually, with many more going undetected. 23 eTable B lists the most common causes of fever in the returning traveler.

Respiratory Illness

Respiratory infections are common in the United States and throughout the world. Ill returning travelers with respiratory concerns are statistically most likely to have a viral respiratory tract infection. 24 Influenza circulates year-round in tropical climates and is one of the most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers. 3 , 12 Influenza A and B frequently present with a low-grade fever, cough, congestion, myalgia, and malaise. eTable C lists the most common causes of respiratory illnesses in the returning traveler.

Gastrointestinal Illness

Gastrointestinal symptoms account for approximately one-third of returning travelers who seek medical attention. 25 Most diarrhea in travelers is self-limiting, with travelers diarrhea being the most common travel-related illness. 7 Diarrhea linked to travel in resource-poor areas is usually caused by bacterial, viral, or protozoal pathogens.

The most often encountered diarrheal pathogens are enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and enteroaggregative E. coli , which are easily treated with commonly available antibiotics. 26 Physicians should be aware of emerging antibiotic resistance patterns across the globe. The CDC offers up-to-date travel information in the CDC Yellow Book . 3 Although patients are often concerned about parasites, they should be reassured that helminths and other parasitic infections are rare in the casual traveler. 3

The disease of concern in the setting of gastrointestinal symptoms is typhoid fever. Physicians should be aware that typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever are clinically indistinguishable, with cardinal symptoms of fever and abdominal pain. 3 Typhoid fever should be considered in ill returning travelers who do not have diarrhea, because typhoid infection may not present with diarrheal symptoms. The likelihood of typhoid fever also correlates with travel to endemic regions and should be considered an alternative diagnosis in patients not responding to antimalarial medications. A diagnosis of enteric fever can be confirmed with blood or stool cultures. Although less common, community-acquired Clostridioides difficile should be considered in the differential diagnosis in the setting of recent travel and potential antimicrobial use abroad. 27

Another important travel-related pathogen is hepatitis A due to its widespread distribution in the developing world and the small pathogen dose necessary to cause illness. Hepatitis A is a more serious infection in adults; however, many U.S. adults have been vaccinated because the hepatitis A vaccine is included in the recommended childhood immunization schedule. 28 eTable D lists the most common causes of gastrointestinal illnesses in the returning traveler.

Dermatologic Concerns

Dermatologic concerns are common among returning travelers and include noninfectious causes such as sun overexposure, contact with new or unfamiliar hygiene products, and insect bites. The most common infections in returning travelers with dermatologic concerns include cutaneous larva migrans, infected insect bites, and skin abscesses. Cutaneous larva migrans typically presents with an intensely pruritic serpiginous rash on the feet or gluteal region. 3 Questions about bites and bite avoidance measures should be asked of patients with symptomatic skin concerns; however, physicians should remember that many bites go unnoticed. 29

Formerly common illnesses in the United States are common abroad, with measles, varicella-zoster virus infection, and rubella occurring in child and adult travelers. 3 Measles is considered one of the most contagious infectious diseases. More than one-third of child travelers from the United States have not completed the recommended course of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the time of travel due to immunization scheduling. One-half of all measles importations into the United States comes from these international travelers. 30 Measles should always be considered in the differential because of the low or incomplete vaccination rates in travelers and high levels of exposure in some areas abroad. eTable E lists the most common infectious causes of dermatologic concern in the returning traveler.

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key words prevention, diagnosis, treatment, travel related illness, surveillance, travel medicine, chemoprophylaxis, and returning traveler treatment. The search was limited to English-language studies published since 2000. Secondary references from the key articles identified by the search were used as well. Also searched were the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Cochrane databases. Search dates: September 2022 to November 2022, March 2023, and August 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

The World Tourism Organization. International tourists to hit 1.8 billion by 2030. October 11, 2011. Accessed March 2023. https://www.unwto.org/archive/global/press-release/2011-10-11/international-tourists-hit-18-billion-2030

- Angelo KM, Kozarsky PE, Ryan ET, et al. What proportion of international travellers acquire a travel-related illness? A review of the literature. J Travel Med. 2017;24(5):10.1093/jtm/tax046.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Yellow Book: Health Information for International Travel . Oxford University Press; 2023. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/table-of-contents

Wu HM. Evaluation of the sick returned traveler. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36(3):197-202.

Scaggs Huang FA, Schlaudecker E. Fever in the returning traveler. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32(1):163-188.

Feder HM, Mansilla-Rivera K. Fever in returning travelers: a case-based approach. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(8):524-530.

Giddings SL, Stevens AM, Leung DT. Traveler's diarrhea. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(2):317-330.

Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han P, et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for travel-related disease–GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997–2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1-23.

Sridhar S, Turbett SE, Harris JB, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in international travelers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021;34(5):423-431.

Matteelli A, Carvalho AC, Bigoni S. Visiting relatives and friends (VFR), pregnant, and other vulnerable travelers. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26(3):625-635.

Ladhani S, Aibara RJ, Riordan FA, et al. Imported malaria in children: a review of clinical studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(5):349-357.

Sanford C, McConnell A, Osborn J. The pretravel consultation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(8):620-627.

Shahbodaghi SD, Rathjen NA. Malaria. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(3):270-278.

Freedman DO, Chen LH, Kozarsky PE. Medical considerations before international travel. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):247-260.

- Marti F, Steffen R, Mutsch M. Influenza vaccine: a travelers' vaccine? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7(5):679-687.

Vivancos R, Abubakar I, Hunter PR. Foreign travel, casual sex, and sexually transmitted infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(10):e842-e851.

Paquet D, Jung L, Trawinski H, et al. Fever in the returning traveler. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119(22):400-407.

Cantey PT, Montgomery SP, Straily A. Neglected parasitic infections: what family physicians need to know—a CDC update. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(3):277-287.

Rathjen NA, Shahbodaghi SD. Bioterrorism. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):376-385.

Jensenius M, Davis X, von Sonnenburg F, et al.; Geo-Sentinel Surveillance Network. Multicenter GeoSentinel analysis of rickettsial diseases in international travelers, 1996–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(11):1791-1798.

Tolle MA. Evaluating a sick child after travel to developing countries. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):704-713.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About malaria. February 2, 2022. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/index.html

Wilder-Smith A, Schwartz E. Dengue in travelers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(9):924-932.

Summer A, Stauffer WM. Evaluation of the sick child following travel to the tropics. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37(12):821-826.

Swaminathan A, Torresi J, Schlagenhauf P, et al.; GeoSentinel Network. A global study of pathogens and host risk factors associated with infectious gastrointestinal disease in returned international travellers. J Infect. 2009;59(1):19-27.

Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers' diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(4):609-614.

Michal Stevens A, Esposito DH, Stoney RJ, et al.; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clostridium difficile infection in returning travellers. J Travel Med. 2017;24(3):1-6.

Mayer CA, Neilson AA. Hepatitis A - prevention in travellers. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(12):924-928.

Herness J, Snyder MJ, Newman RS. Arthropod bites and stings. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):137-147.

Bangs AC, Gastañaduy P, Neilan AM, et al. The clinical and economic impact of measles-mumps-rubella vaccinations to prevent measles importations from U.S. pediatric travelers returning from abroad. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022;11(6):257-266.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2023 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Emerg Infect Dis

- v.21(11); 2015 Nov

Ebola in West Africa—CDC’s Role in Epidemic Detection, Control, and Prevention

Stronger systems are needed for disease surveillance, response, and prevention worldwide.

Since Ebola virus disease was identified in West Africa on March 23, 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has undertaken the most intensive response in the agency’s history; >3,000 staff have been involved, including >1,200 deployed to West Africa for >50,000 person workdays. Efforts have included supporting incident management systems in affected countries; mobilizing partners; and strengthening laboratory, epidemiology, contact investigation, health care infection control, communication, and border screening in West Africa, Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, and the United States. All efforts were undertaken as part of national and global response activities with many partner organizations. CDC was able to support community, national, and international health and public health staff to prevent an even worse event. The Ebola virus disease epidemic highlights the need to strengthen national and international systems to detect, respond to, and prevent the spread of future health threats.

The unprecedented epidemic of Ebola virus disease (Ebola) in West Africa highlights the need for stronger systems for disease surveillance, response, and prevention worldwide. After a preventable and costly local and global delay, heroic efforts by clinicians and public health personnel and organizations from West Africa and throughout the world broke the cycle of exponential growth of the epidemic and prevented many deaths. As of late 2015, this response, conducted at great expense and personal risk, continues. Here we summarize the experience of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which complements efforts by the affected countries, the international community, and many partner organizations.

Since Ebola was first reported in West Africa on March 23, 2014, CDC has undertaken the most intensive outbreak response in the agency’s history. As of July 2015, >1,200 CDC employees had deployed to the affected countries for >50,000 person workdays; >3,000 CDC staff, including all 158 Epidemic Intelligence Service Officers, have participated in international or domestic response efforts. For context, over the course of more than a decade, ≈300 CDC staff participated in the smallpox eradication program, one of CDC’s most notable international responses and most intensive technical collaborations with the World Health Organization (WHO) before the current Ebola response ( 1 ).

CDC had a team of experts on the ground in Guinea within 1 week after the initial case report. When Ebola resurged and spread, CDC activated its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) ( 2 ) on July 9, 2014. Since then, CDC has coordinated >1,400 deployments to Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone and sent staff to help Nigeria ( 3 ), Senegal ( 4 ), and Mali ( 5 ) prevent the spread of Ebola. CDC staff also have undertaken development of new diagnostic tests ( 6 ) and research to evaluate therapeutic drugs ( 7 ) and vaccine efficacy ( 8 , 9 ). As of mid-2015, >500 CDC staff continued working throughout the 3 most heavily affected nations (Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia), the West Africa region, and the United States.

At the peak of the epidemic in fall 2014, widespread transmission of Ebola virus was occurring in the capitals of Liberia and Sierra Leone; health care systems had become largely nonfunctional; Ebola cases or clusters occurred in other countries of Africa; and there was a real possibility that Ebola could spread widely and become endemic in some of the poorest and sickest countries of the world. As of late2015, although the region is not Ebola-free, enormous progress has been made. There is a risk for resurgence and cross-border spread, and because the status of Ebola virus reservoirs is not confirmed and the possibility of sexual transmission from survivors persists, the potential exists for periodic outbreaks.

CDC Response in Heavily Affected Countries

Incident management.

One challenge in responding to complex outbreaks is coordination among partners. CDC’s priority in West Africa during summer 2014 was to augment the efficiency of response activities through incident management systems run by national leaders and supported by an EOC reporting to the president of each affected country. These systems were developed in collaboration with WHO and served as the focal point for international assistance. CDC also helped countries establish subnational EOCs in areas with Ebola virus transmission in Liberia and Guinea; the United Kingdom similarly played a key role in Sierra Leone. When resources had to be mobilized rapidly, the CDC Foundation, a not-for-profit philanthropic entity authorized by the US Congress in 1992 to help CDC improve its response capacity ( 10 , 11 ), supported staffing, logistics, data management, informatics, and operations of EOCs.

Epidemiology and Surveillance

Working with governments, nongovernmental organizations, and WHO, CDC epidemiologists assisted national- and district-level staff in each country in identifying cases and contacts and trained in-country staff to perform these essential public health activities. Because clinical, public health, laboratory, and data systems were overwhelmed ( 12 ), CDC staff assisted with data entry and management, including geographic information systems to track and evaluate disease trends.

Contact Tracing

After the cycle of exponential epidemic growth was broken and personnel could refocus on contact identification, CDC strengthened work with national counterparts and WHO to help improve the quality of contact identification and follow-up, including isolation of symptomatic contacts for clinical assessment and laboratory testing. These activities were vital to reduce Ebola transmission. WHO has played a critical role in improving contact tracing and contact management, particularly in Guinea ( 13 ).

Laboratory Testing

Global collaboration with laboratories from a European Union consortium made real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR available in the heavily affected West Africa countries for patients and decedents suspected of having Ebola. CDC experts helped coordinate the laboratory section of the incident management system, supported laboratories in Liberia with the US Department of Defense (DoD) and National Institutes of Health, and operated a field laboratory in Bo, Sierra Leone, that processed >2,000 samples during a 3-week period at the height of the epidemic ( 14 ); by mid-2015, that laboratory had processed >20,000 samples.

Rapid Isolation and Treatment of Ebola Patients

Rapid isolation and treatment of Ebola patients is a key strategy to stop Ebola outbreaks. Each country had limited capacity to isolate and treat patients, and strategies to do so effectively and safely evolved over time. In collaboration with the US Agency for International Development’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA), WHO, DoD, and multiple other partners, CDC provided technical support and training to establish Ebola treatment units (ETUs) and community care centers. Beginning in early October 2014, CDC designed and helped implement a strategy of rapid isolation and treatment of Ebola (RITE) in Liberia. This strategy controlled outbreaks faster and supported the care of patients in remote areas, cutting the time to control outbreaks in half ( Figure 1 ) and doubling survival rates ( 15 ).

Decreased size and duration of outbreaks in remote areas before and after implementation of the Rapid Isolation and Treatment of Ebola (RITE) strategy, Liberia, 2014. Size of circle is proportional to number of cases in cluster.

Infection Control

In the 3 heavily affected countries, CDC and its partners trained >25,000 health care workers in infection control, including use of personal protective equipment (PPE) ( 16 ). A 3-day hands-on training course designed by CDC with Médecins Sans Frontières trained >600 US health care providers on Ebola clinical care and infection control before their deployment to West Africa ( 17 ).

Health Promotion and Communications

In addition to the efforts of partner organizations, CDC field teams included emergency risk communication specialists to generate and disseminate accurate information, address rumors, decrease stigma, reduce unsafe burial practices, and respond to community needs. CDC staff in Liberia and Sierra Leone identified and promulgated burial practices that met community needs for culturally acceptable mourning, thus reducing resistance to safe burials ( 18 , 19 ). In all countries, community engagement and effective communication were key strategies for successful outbreak control.

Technical Guidance

CDC has issued >200 scientific documents, including >100 technical guidance documents, covering many aspects of the response. CDC staff also worked closely with UNICEF and other partners to develop guidance in related areas, such as safe reopening of schools ( 20 ).

Mobilization of Partners

During summer 2014, CDC recognized that despite Médecins Sans Frontières’ massive response; CDC’s own response; and responses of affected countries, WHO, and international partners, the epidemic was spiraling out of control. CDC then advocated to increase involvement by the US government and the global community.

DoD, along with USAID/OFDA’s Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART), has been a key partner in this scale-up. Initially focused on researching treatments and vaccines and providing laboratory diagnostics, in September 2014, DoD took the lead on constructing, supplying, and maintaining a field hospital to treat health care workers with Ebola in Liberia. DoD also deployed 3,000 military personnel for logistics and coordination, provision of medical personnel to train health care workers, establishment of additional treatment centers in Liberia, and operation of 3 mobile medical laboratories ( 21 ). The DART provided coordination to rapidly engage partners providing services and supporting response efforts; CDC staff served as the technical lead for health, public health, and medical issues within the DART.

Epidemic Modeling

A CDC model that projected the possible trajectory of the epidemic if the trend of rapid transmission through August 2014 continued unabated was key to increasing the speed and scale of the US and global response ( 22 ). The worst-case scenarios of the model made clear the need for urgent action and helped stimulate a massive global response.

Analysis from the model provided 4 key findings. First, cases were increasing exponentially, and the response needed was massive and urgent. CDC helped facilitate assistance, including from the African Union, which mobilized nearly 1,000 staff, including doctors, nurses, epidemiologists, and health educators ( 23 ).

Second, the model predicted a severe penalty for delay; case numbers at the peak roughly tripled for every month of delayed scale-up ( Figure 2 ). Thus, interventions (isolation, treatment, and safe burials) had to be rapid, with action and progress measured in hours and days rather than in weeks and months. In each country, CDC encouraged national leaders, incident managers, health workers, the media, and communities to take action, immediately because even a rapid international response would not be fast enough.

Estimated impact of delaying intervention on daily number of Ebola virus disease cases, Liberia, 2014–2015. The intervention modeled is as follows: starting on September 23, 2014 (day 181 in model), and for the next 30 days, the percentage of all patients in Ebola treatment units increased from 10% to 13%. This percentage was again increased on October 23, 2014 (day 211 in model) to 25%, on November 22, 2014 (day 241 in model) to 40%, and finally on December 22, 2014 (day 271 in model) to 70%. Day 1 in model is March 3, 2014. The impact of a delay of starting the increase in interventions was then estimated by twice repeating the above scenario but setting the start day on either October 23, 2014, or November 22, 2014. When the intervention is started on November 22, 2014, the peak is not reached by January 20, 2015, which is the last date included in the model. Graph based on Figure 10 in Meltzer et al. ( 22 ).

Third, the model identified a tipping point at which the epidemic would plateau and decline if enough (i.e., > 70%) Ebola patients were isolated effectively and decedents buried safely. This finding led to establishment of community isolation facilities ( 24 ) and to contracting by USAID/OFDA for burial teams that worked to technical specifications established by CDC, first in Liberia and later in Sierra Leone ( 25 ). In Liberia, experienced CDC public health specialists conducted detailed planning exercises with community, political, medical, and public health leaders in each county to identify where sick persons could be isolated until ETUs were constructed and how contacts could be monitored and cared for if they became ill.

Fourth, the model predicted that when the tipping point was reached, transmission would decline rapidly. This prediction was shown to be accurate in the following months in Liberia and Sierra Leone ( Figure 3 ). For Liberia, the model’s prediction that if urgent action were taken, there would be 10,000–27,000 cumulative cases by January 21, 2015, closely matched the 8,500–24,000 cases that occurred ( Figure 4 ). The predictions also closely matched the actual case trajectory after effective intervention.

Comparison of estimated weekly Ebola virus disease case rate for Liberia with intervention with actual weekly case rates for Liberia and Sierra Leone. The September 2014 modeled projection curve was based on Figures 9 and 10 in Meltzer et al. ( 22 ), by using model predictions calculated assuming that interventions started on September 24, 2014. Liberia, week 1 begins May 4, 2014; Sierra Leone, week 1 begins May 25, 2014. The model projected the incidence that would occur if the proportion of Ebola patients who were hospitalized was 25% at week 22, increased to 40% at week 26, and increased again to 70% at week 30, while the proportion in effective home isolation remained constant at 10%. The similarity in the increase and decrease in the actual epidemic curves in both Sierra Leone and Liberia closely match the model after taking into account differences in start dates and population sizes between the 2 countries, implying that the proportion of cases effectively isolated in both countries followed a similar time course as the model.

Comparison of the estimated impact of interventions on number of Ebola cases with actual cases reported, Liberia, 2014–2015. The September 2014 modeled projection curve was based on Figure 3 in Meltzer et al. ( 22 ) by using model predictions calculated assuming that interventions started on September 24, 2014. The corrected curve of projected cases is adjusted for potential underreporting by multiplying reported cases by a factor of 2.5. Actual reported cases are from World Health Organization situation report for January 21, 2015 ( 26 ).

Border Health Security

CDC worked with ministries of health and airport authorities in all 3 heavily affected countries, as well as in other affected countries, to establish screening of travelers leaving the country by air to prevent sick or exposed persons from boarding planes. By mid-2015, >200,000 travelers leaving Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone had been screened. In addition to reducing the likelihood of additional spread of Ebola to other countries, this screening, along with CDC’s work with airlines to address air transport industry and flight crew concerns, helped enable humanitarian and public health organizations to sustain travel to affected areas by regular commercial airline flights. CDC staff also provided technical assistance on measures to reduce risk for spread through maritime ports and across land borders.

CDC laboratory scientists implemented high-throughput laboratory capacity by using robotics and collaborated with private industry to promote development of lateral-flow assays to detect Ebola in point-of-care settings within 30 minutes after a finger stick or oral swab ( 6 ). In addition to supporting the National Institutes of Health randomized controlled trials of Ebola treatment ( 27 ) and vaccines ( 28 ), CDC staff worked with Sierra Leone authorities to implement a parallel Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine against Ebola (STRIVE), an adaptive, phased-introduction trial of a vaccine candidate among health workers in that country ( 8 , 9 ).

Support to Other At-Risk Countries

In Nigeria, a cluster of Ebola cases in July 2014 resulted from a traveler from Liberia. CDC deployed disease control experts to Lagos, the country’s most populous city, within 72 hours and, in the first week after disease confirmation, supplemented response efforts with 13 Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) trainees, graduates, and trainers who had experience in epidemiology and infection control. In the 2 weeks that followed, CDC sent additional agency staff and helped mobilize 40 CDC-trained physicians from Nigeria’s FETP. With the Nigerian government and partners, CDC facilitated creation of an effective incident management system, using leadership and staff from the Nigerian Polio Eradication Program and support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. This incident management system oversaw training of 2,300 health care staff, creation of an ETU in 14 days, and identification of >800 contacts; conducted 19,000 home visits of these contacts to monitor symptoms and temperatures; and screened >150,000 persons at airports. Although 19 secondary cases of Ebola occurred in 3 generations of spread in 2 cities, this rapid action controlled transmission, and Nigeria has been Ebola-free since this incident ( 3 ).

CDC staff provided similar assistance in Mali after a child arriving from Guinea died of Ebola and again after a cluster of cases occurred from a person from the Mali–Guinea border who had previously undiagnosed Ebola ( 29 ), and in Senegal after an incident of disease importation ( 4 ). CDC also collaborated with WHO to increase preparedness in at-risk countries by helping establish EOCs, surveillance for hemorrhagic fever and clusters of deaths, training in contact tracing, laboratory specimen transport and testing, isolation capacity for patients suspected of having Ebola, health communication messages, and border health security.

Ebola in the United States

Before diagnosis of the first case of Ebola imported to the United States, CDC alerted US health care providers to consider Ebola if compatible signs and symptoms manifested within 21 days after a traveler arrived from an affected country ( 30 ). CDC also issued infection control guidance for hospitals ( 31 ); strengthened laboratory networks and existing surveillance systems; and disseminated recommendations for travelers on the CDC website, through social media channels, and at US international airports.

The first case of Ebola diagnosed in the United States, imported by a traveler from Liberia, revealed gaps in hospital preparedness and response capabilities ( 32 ). Ebola was not considered in the patient’s initial presentation, despite fever and travel history to Liberia. CDC provided assistance to the state and local health departments and to nearby hospitals. Two nurses caring for the patient were infected, most likely as the result of underprepared processes, lack of training, and suboptimal use of PPE during the first few days of the patient’s second hospitalization, before his Ebola diagnosis. CDC subsequently strengthened recommendations for infection control, particularly training, supervision, and specifications of PPE. The second nurse who became ill was allowed to travel by air despite exposure that CDC should have categorized as high-risk to prevent the nurse from flying ( 33 ). In turn, this measure would have reduced the number of travelers whose health was monitored and the work of public health personnel monitoring contacts.

Recognizing a need for enhanced preparedness and training, CDC staff then visited 81 facilities in 21 states and Washington, DC, helping 55 of these facilities qualify as Ebola Treatment Centers for patients with suspected or confirmed Ebola. CDC also has qualified 56 state, county, and local public health laboratories to perform real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR for Ebola with a Food and Drug Administration–approved DoD assay developed by the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases ( 34 ).

CDC established Ebola Response Teams composed of CDC experts in infection control, clinical care, contact tracing, communications, environmental waste management, and other areas to support state and local health departments and to deploy to any hospital in the United States that has a patient under investigation for Ebola ( 35 ). CDC staff arrived at New York City’s Bellevue Hospital before Ebola was confirmed in the patient treated there.

To strengthen protection throughout the United States and to preclude restrictions on travel that could have undermined the response in West Africa and led to surreptitious travel from the region, CDC, together with the US Customs and Border Protection and state and local public health departments, developed a postarrival monitoring program to educate and follow >20,000 travelers arriving in the United States from Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone since October 2014 ( 36 ). Travelers are met at the airport and provided with Check and Report Ebola (CARE) kits that include health education materials, a thermometer, and ways to connect with their state or local health department, including a prepaid cell phone. Through mid-May 2015, >1,200 travelers were referred to CDC for additional screening because of illness or, more commonly, to assess possible exposures; 28 persons were referred for medical evaluation. Ebola was not diagnosed in any of these persons ( 37 ).

Nearly 500 persons considered to be at “some or high risk” received direct active monitoring that included daily direct observation of symptoms and temperature monitoring by health workers. More than 20,000 travelers classified as “low but not zero risk” received active monitoring, in which they monitored their own temperature and any symptoms and reported daily to the state or local health department until 21 days after their departure from an Ebola-affected country (an effort that has involved >400,000 cumulative contacts with arriving travelers). Health departments facilitated safe transport to a hospital ready to assess travelers for Ebola if the person developed fever or other symptoms of concern.

Before initiation of the active monitoring program, 1 case of Ebola was detected by self-monitoring; rapid detection and isolation prevented further disease transmission. Every jurisdiction now monitors travelers arriving from the highly affected countries and reports to CDC.

The Ebola epidemic in West Africa is unprecedented in size and geographic distribution; it spread in many areas unfamiliar with the disease, including the first large urban outbreaks of Ebola. If the response in West Africa and global assistance had been implemented earlier, faster, and more effectively, far fewer cases and deaths and much less social and economic disruption would have occurred. The epidemic has shown that critical improvements are needed in 2 main areas. First, the ability of every country to quickly identify and respond to a health threat needs to be enhanced. Second, the ability of the global community to rapidly respond to needs in a country overwhelmed by an epidemic must be improved.

For months, the Ebola epidemic spread faster than the international community, including CDC, responded. Critical barriers in the affected countries include limited electronic connectivity ( 38 ); insufficient numbers of trained staff; inability to surge rapidly enough to provide needed case detection, education, contact tracing, and isolation services; and poorly functioning national health and public health systems with staff who often were unpaid, untrained, and poorly supervised. Surveillance and data management systems were overwhelmed; solutions are needed to manage, track, and support large outbreaks and public health interventions.

Stronger national and international systems for disease detection and control are needed. Paradoxically, the world is better prepared to find and stop emerging health threats than at any time in history, yet also is at greater risk for rapid spread of infectious diseases, which occur more frequently because of encroachment into forest areas, spread of antimicrobial-resistant organisms, and increasing ease of creation of dangerous pathogens, in the context of an increasingly mobile, interconnected, and urban world. The global community must use these lessons to improve response systems for large-scale emergencies, following the principles of the International Health Regulations, while using core staff and facilities on a daily basis to respond to ongoing health problems.

If the 3 highly affected countries had had effective surveillance and containment systems in place before 2014, the outbreaks might have been detected and stopped promptly ( 39 ). There was an unrecognized need for more effective control in urban areas with mobile populations. The use of the incident command system in this complex scenario was critical for organizing focused efforts to stop chains of transmission at the community level and within the health care system. Trust and coordination had to be established with more diverse communities, many of which were in postconflict environments, than in past outbreaks. In all 3 countries, emergency risk communication was a dynamic process, changing as the outbreak evolved, to promote understanding of nuanced messages of risk. Community engagement and understanding of each local community’s beliefs and traditional practices was critical to success of the overall response and particularly important to ensure rapid isolation of infected patients, complete elicitation and monitoring of contacts, and safe burials.

In Uganda, where CDC and others have invested in public health for years, cases of Ebola and Marburg virus disease are now diagnosed promptly, infection control and contact tracing quickly implemented, and outbreaks either stopped rapidly or prevented altogether ( 40 ). Similarly, leveraging infrastructure and assets developed through the polio eradication efforts in Nigeria enabled an effective rapid response and demonstrated the value of investing in core public health capacities and training epidemiologists through the country’s FETP program, which is needed in countries around the world. In contrast, before the outbreak, CDC had limited activities and no offices in any of the 3 heavily affected countries. The Global Health Security Agenda, supported by the United States in partnership with other nations and international organizations, seeks to rapidly improve the capacity of countries throughout the world to find, stop, and, wherever possible, prevent the spread of health threats ( 41 , 42 ).

Sustainable response capacity of international entities also needs to be improved. There were initial delays in effective response by WHO country offices and initial resistance of these offices and the African Region of WHO to involve CDC and other organizations ( 43 ). WHO has since mounted an effective response supporting the core public health interventions to stop spread of Ebola and is working to become more effective. The Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network is designed to provide a global response ( 44 ) but needed more staff with a wider range of skills to be deployed rapidly and for longer periods of time. Organizations that participated in the response needed a broad range of skills, including expertise not only in laboratory and epidemiologic functions but also clinical care, logistics, health communications, information technology, data management, and anthropology, as well as fluency in English, French, and local languages and substantial knowledge of the cultural, social, and religious sensitivities that need to be addressed to engage communities and stop the spread of disease. CDC, along with communities, health care workers, and leaders in the affected nations and the international community, will continue to respond until the Ebola epidemic ends and is committed to strengthening national capacities in West Africa and elsewhere to prevent similar epidemics in the future.

Acknowledgments