Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Compare and contrast how R.C.Sherriff and Pat Barker present the theme of masculinity in the play 'Journey's End' and the book 'Regeneration'

Related Papers

Constructions of Masculinity in British Literature from the Middle Ages to the Present

Silvia Mergenthal

Kateřina Poulová

comments and constructive help he kindly offered during the writing phase of the thesis. The thesis deals with Pat Barker's Regeneration trilogy which presents both fictional and real-life characters of the First World War suffering from shell shock that was perceived as a crisis of masculinity, and supports the theory that it was a false interpretation based on the beliefs and highly adjusted codes the society had created. The introduction uncovers the problem of mental breakdowns that thwarted the dreams of many a man who entered the war with different views of the masculine deal. It also reveals a brief summary of some parts of Barker's life that had a great influence on the writing of the novel as well as on her own development as a writer. The main body of the thesis introduces the subject of masculinity and the construction, perception and infringement of its norms. Further on, mainly the rise and development of shell shock is explored based on non-fictional records ...

Angeles De la Concha

The English literary canon of the Great War has been traditionally shaped by the poetry of the poets who fought the war on the basis of their having seen and experienced its full horror, which attested truthful representation. This premise excluded women writers, whose participation in and experience of the war was obviously very different. Feminist research on the literary contribution of female writers to the representation of the conflict based on the plurality of experiences of many women that challenge that assumption have effectively worked to redress the balance. In this context, the war novels of contemporary female writers with male protagonists are negatively judged for miming the male gaze. In this article I would like to show that far from it Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, whose third volume was awarded with the Booker Prize, uses the male gaze precisely to unveil and expose the war entrenched patriarchal discourse and practices. Key words: canon, WWI, male gaze, patriarchal discourse and practices, gender.

Revue française de civilisation britannique

Ana Carden-Coyne

International Journal of Arts and Sciences

cyrena mazlin

Tahir Gulkaya

This thesis investigates how psychoanalysis might explain masculinity, and how that could relate to the way a soldier may have experienced trauma in World War One. It looks at the letters and retrospective accounts soldiers wrote describing their feelings about fear, and it focuses on key moments that may align with psychoanalytic ideas throughout the three chapters. It also attempts to explain the way soldiers may have understood masculinity, and how that understanding may have impacted the way they tried to hide their fear from each other. It likewise examines the path of how masculinities ideals could have been internalised by a little boy during the same period as the superego formed, which might be described as the first appearance of the masculine ideals. Therefore, this thesis is about how psychoanalysis understands masculinity, and how that understanding could have impacted war trauma in World War One.

Alice Ferrebe

Studies in Twentieth Century Literature

Misha Kavka

Cristina Pividori

Among the experiences of otherness that unsettled the imperial trope of the warrior hero, this paper focuses on the representation of the coward in three autobiographical responses to the Great War. By following the traces of the malingerer, the deserter and the psychologically injured soldier in Herbert's The Secret Battle (1919), Aldington's Death of a Hero (1929) and Manning's Her Privates We (1930), the hero-other distinction induced by Victorian standards will be explored as a popular theme that becomes problematic on the Western front, as the figure of the (heroic) self and of the (antiheroic) other start to move away from the rigidity of the binary system. While Herbert, Aldington and Manning keep a strong component of their own class and patriotic identity both in their novels and in their lives, the Great War experience suggests the possibility of removing the association traditionally maintained between heroism and the Victorian notions of manliness. Such openness not only challenges the norm, but paves the way for the elaboration of a new sense of heroic selfhood. Particular attention is given to the representation of the shell-shocked soldier as a site of struggle and negotiation between the trope of cowardice and its reality.

… fields: Perspectives in First World War …

Jessica Meyer

RELATED PAPERS

JOURNAL OF SCIENCE EDUCATION AND PRACTICE

irfan ajizi

AL-ISHLAH: Jurnal Pendidikan

Dwi Rahmadini

Datenschutz und Datensicherheit ( …

Christoph Thiel

International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications

Yuliadi Erdani

Belügyi Szemle

gusstiawan saputra

The Journal of Organic Chemistry

Dr. Andreas Koch

Cancer Nursing

Cathy Henshall

Agroalimentaria

Luis Pinedo Torres

Environmental Science and Pollution Research

stefania iordache

Journal of Agricultural Engineering

Giovanni stoppiello

Brazilian Journal of Development

Gilton Albuquerque

Jurnal Hukum dan Keadilan "MEDIASI"

Airi Safrijal

Remus Chendes

The Political Quarterly

James M. Glass

Francesca Valentini

Nanotechnology for Environmental Engineering

Apeksha Chavan

Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia

Antonio Jose Costa

IEICE Transactions on Communications

Ichthyology & Herpetology

Devi Stuart-Fox

Current Organocatalysis

Dr. Biswa Mohan Sahoo

Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry

Hiroshi Sakagami

Nellie Mae Education Foundation

Youn Joo Oh

Jati Wibowo

Analytical Biochemistry

Nguyên Nguyễn

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Journey's End

By r.c. sherriff, journey's end quotes and analysis.

"I hope you get better luck than I did with my last officer. He got lumbago the first night and went home. Now he's got a job lecturing young officers on 'Life in the Front Line'." Captain Hardy, Act I, p. 10

Speaking with Osborne, Hardy mocks the common schemes that officers employ to leave the war. In this passage, he speaks of an officer of his who left because of a back problem and later claimed to be a combat expert, when in reality he was barely able to face life in the trenches.

"Well, if you want to get the best pace out of a cockroach, dip it in whiskey—makes 'em go like hell!" Captain Hardy, Act I, p. 15

In this quote, Hardy gives Osborne advice on the soldiers' pastime of betting and racing cockroaches, a statement that stands in contrast to the discussion they have had about Stanhope's PTSD-related alcoholism and the looming threat of a rumored German attack. The passage is significant because it represents one of many instances of officers using dark humor to deal with the bleak circumstances in which they live.

"You see, he's been out here a long time. It—it tells on a man—rather badly." Osborne, Act I, p. 19

In this passage, Osborne tries to warn Raleigh that his heroic image of Stanhope may not match Stanhope's present, battle-addled condition. The difficulty Osborne has in articulating the statement is significant, as it speaks to how Osborne would not like to undermine Stanhope's authority by spreading doubt about his mental condition, while he nonetheless wants the bright-eyed Raleigh not to grow disillusioned.

Osborne: Small boys at school generally have their heroes. Stanhope: Yes. Small boys at school do. Osborne: Often it goes on as long as — Stanhope: — as long as the hero's a hero. Osborne: It often goes on all through life. Osborne and Stanhope, Act I, p. 30

In this private conversation on the subject of Raleigh's idolization of Stanhope, Osborne and Stanhope touch on the theme of heroism. Having looked up to Stanhope at school, Raleigh and Raleigh's sister turned him into a hero. However, Stanhope reveals in this dialogue his concern that Raleigh will see Stanhope for who he is truly is, having been damaged by the effects of war. Osborne sees things differently, and has faith that Raleigh will continue to see him as a hero, despite Stanhope's drinking and temper.

"She doesn't know that if I went up those steps into the front line—without being doped up with whiskey—I'd go mad with fright." Stanhope, Act I, p. 31

In this passage, Stanhope confides to Osborne that he drinks constantly in order to overcome his fear. He is concerned that Raleigh will report in a letter to his sister, to whom Stanhope is engaged, that he drinks constantly. He worries that she will not understand the brutal conditions he endures, and how he relies on drinking in order to calm his addled nerves.

"I believe Raleigh'll go on liking you—and looking up to you—through everything. There's something very deep, and rather fine, about hero-worship." Osborne, Act I, p. 33

In this passage, Osborne repeats his earlier suggestion that Raleigh's admiration for Stanhope will persist, despite the war-damaged person Stanhope has become. This quote is significant because it reveals Osborne's wisdom; as Stanhope will see when he hears Raleigh's letter, Osborne's prediction bears true.

"Tell me, mother, what is that That looks like strawberry jam? Hush, hush, my dear; 'tis only Pa Run over by a tram—" Trotter, Act II, Scene 2, p. 62

In this passage, Trotter blithely recites a grim rhyme about a mother reassuring her daughter at the sight of her husband being run over by a tram. This passage is significant because it speaks to the play's thematic concern with repression, revealing how soldiers use gallows humor to remain in high spirits when faced with the grim reality of war.

"To forget, you little fool—to forget! D'you understand? To Forget! You think there's no limit to what a man can bear?" Stanhope, Act III, Scene 2, p. 85

Raleigh does not feel like partaking in the higher quality food and champagne that celebrates the successful raid because he is stricken by sadness that Osborne did not make it back alive with him. Stanhope rebukes him, clarifying that he isn't the only one who cares that Osborne died, and that he drinks not to celebrate but to cope. This passage is significant because he finally admits to this weakness to Raleigh, risking that Raleigh will pass the revelation on to his sister, to whom Stanhope is engaged.

Raleigh: Hullo— Dennis— Stanhope: Well, Jimmy—( he smiles )—you got one quickly. Stanhope and Raleigh, Act III, Scene 3, p.93

After Stanhope learns that Raleigh has had his spine broken by a piece of shrapnel, he orders the sergeant-major to bring Raleigh back to him in the dugout. Lying in Osborne's former bed, Raleigh momentarily regains consciousness. In this passage, the two men greet each other with their first names. Although Raleigh has used Stanhope's first name a number of times, this is the first time that Stanhope calls Raleigh by his. This passage is significant because it reveals a tenderness between the characters, reminding the audience of the human lives that soldiers live outside of war.

" A tiny sound comes from where RALEIGH is lying—something between a sob and a moan. " Stage direction, Act III, Scene 3, p. 94

After Stanhope leaves Raleigh's bedside to fetch a candle, Raleigh emits a small, ambiguous sound. The sound turns out to be the last sound Raleigh makes before he dies—his final breath.

Journey’s End Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Journey’s End is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

How does Sherriff create tension in the duologue between Osborne and Stanhope at the end of Act 1?

Stanhope meets the revelation that Raleigh has joined his company with unease. The presence of Raleigh introduces a new conflict to the play that involves the themes of heroism, alcoholism, and PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). Stanhope knows...

What are Trotter's quotes showing his emotions?

From the text:

Trotter (throwing his spoon with a clatter into the plate) : Oh, I say, but dam!

Trotter : Well, boys ! ’Ere we are for six days again. Six bloomin’ eternal days. {He makes a calculation on the table.)

Trotter comes down the steps,...

How Sherriff presents the true horrors of was through the character of Raleigh?

The difference between the fantasy of war and its true, horrific and demoralizing nature is one of the play's major themes. The theme is most overtly revealed through Raleigh's character arc. When Raleigh first arrives, his boyish excitement at...

Study Guide for Journey’s End

Journey's End study guide contains a biography of R. C. Sherriff, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Journey's End

- Journey's End Summary

- Character List

Essays for Journey’s End

Journey's End essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of the play Journey's End by R. C. Sherriff.

- The Depiction of War in Journey’s End and Exposure

- How does Sherriff present Heroism in Journey's End?

- How Stanhope Generates Conflict in the Opening Act

- Comparison of the mental suffering created by war

- Human Decency in a World of Human Waste

Wikipedia Entries for Journey’s End

- Introduction

- Plot summary

- Productions (professional)

- Productions (amateur)

- Adaptations

- TOP CATEGORIES

- AS and A Level

- University Degree

- International Baccalaureate

- Uncategorised

- 5 Star Essays

- Study Tools

- Study Guides

- Meet the Team

- English Literature

- Other Play Writes

Through the selection of three characters in 'Journey's End' examine how Sherriff presents human weakness in the play.

Through the selection of three characters in 'Journey's End' examine how Sherriff presents human weakness in the play.

'Journey's End' is an anti-war play written by R. C. Sherriff. It deals with the effects of war on a select group of officers and has a static setting: the dugout of these officers. The play explores the way war affects men, the concept of masculinity, the exploitation of youth during the war, as well as class differences and other themes. One overarching theme, which encompasses how war affects men and masculinity, is that of human weakness. Sherriff questions contemporary and modern views of human weakness, as well as asking whether mental disturbance is intrinsically tied to war and whether this can be avoided.

Sherriff's decision to write 'Journey's End' as a play may simply be due to his own preferences; he may simply have wanted to write a play as opposed to a novel. However it allows an intimate atmosphere to be created between the audience and characters. In presenting human weakness Sherriff has the advantage of being able to force the audience to experience life in a dug-out – the noise, the claustrophobia, the constant threat of attack - thus sharing the stress of the environment between the characters and audience, and demanding that the audience empathise with the experiences of the characters through this.

Sherriff's gender directly influences the play as Sherriff had served in the trenches during the First World War, something which would not have been possible had he been female. He was able to use his own experiences within the play, and also knew first-hand the reality of warfare and how humans are affected by this. His portrayal of human weakness is therefore likely to be accurate and true to the situation; it would be much harder to create convincing characters in this situation had Sherriff not experienced life at the frontline.

'Journey's End' is very much a play of its period. It was first published in 1929, eleven years after the end of the First World War. Although attitudes to war and human weakness had changed due to the huge losses incurred and the collective observation of the effects, such as shellshock, the war had had on an entire generation of young men, there still remained an association between human weakness and effeminacy. Sherriff therefore had to present human weakness in a way which would introduce those who believed that displaying weakness was a feminine trait to the fact that not every man who feels fear or breaks down is effeminate, but which would also further the understanding of those who had already realised that this link was broken. 'Journey's End' still works as a play now and has messages for a modern audience, which is a testament to Sherriff's skill.

The three characters which best display the theme of human weakness in 'Journey's End' are Stanhope, Hibbert and the Colonel. Although this is a shared characteristic there are many contrasts between the trio: Stanhope and the Colonel both hide their weaknesses, while Hibbert's are plainly displayed. Their weaknesses also come in different forms: the Colonel cannot, or does not, wish to empathise with the men, while Stanhope and Hibbert are both cracking under the strain of war. Stanhope and Hibbert both display vices, most notably drinking, which are weaknesses in themselves but also ways of coping with weakness.

This is a preview of the whole essay

Dramatic devices are used to present human weakness throughout the play and in Stanhope, Hibbert and the Colonel. A dramatic device is any technique used within the play to create a specific effect, which is in this case to comment on human weakness. One dramatic device Sherriff uses is a physical description within the stage directions. Although the audience would obviously not read this, it would translate into the way a character was presented (costume, choice of actor, make-up etc.) on stage. Both Stanhope and Hibbert are described in this manner, the Colonel is not, although this has something to say about his weaknesses as well.

While both Stanhope and Hibbert are described in the stage directions, Stanhope is presented as an upstanding young officer, while Hibbert is immediately presented as weak. Sherriff describes Stanhope as having “dark hair... carefully brushed” and wearing a “uniform ...[which is] well cut and cared for”. This suggests that Stanhope is a professional who, despite his age, is eager to appear as smart as possible. At this point he appears to be a 'normal' young, high-flying officer (we are told that he is wearing “stars of rank.... [despite being] no more than a boy”, indicating that he is performing well above his age and is an able and confident officer. His appearance reinforces this impression). Hibbert, however, appears to be the opposite. He is “small and slightly built”, suggesting that he is physically weak (and probably mentally as well), contrasting with the powerful, commanding presence of Stanhope in his “well cut” uniform. Hibbert's “little moustache” implies that with his failure to grow a “real” moustache, he is also a failure in life. While Stanhope's “carefully brushed” hair seems professional, Hibbert's failed attempt at a moustache suggests someone who is vain, and perhaps deluded as to how others see him. Both men have their weaknesses hinted at through their pale faces (Stanhope has “a pallor under his skin” while Hibbert has “a pallid face”), though Stanhope's weaknesses seem to be half concealed, hence why the pallor is described as being “under his skin” rather than in plain sight as Hibbert's are. Sherriff presents the audience with two conflicting images of human weakness: Hibbert, the stereotypically weak man, and Stanhope, the seemingly strong and confident company commander, who tries hard to conceal his weaknesses but never quite manages it.

The Colonel is completely different to both Stanhope and Hibbert. He is not described, and is never named more personally than “the Colonel”. Although in a production of 'Journey's End' there would obviously be an actor playing the Colonel, the lack of description in the stage directions seems to suggest that either it does not matter what the Colonel looks like, or that the Colonel simply acts as a vehicle for Sherriff's views on the weaknesses high-ranking officers and/or men from the upper classes display. The latter seems more likely, given that the Colonel behaves in a way which is stereotypical of his role and class. As already mentioned, the Colonel's main weakness is a lack of empathy, stemming from cowardice. This will be expanded upon later in this essay, but for now it suffices to say that Sherriff, through the lack of description of the Colonel, effectively states that the majority of higher-ranking officers are cowards.

Sherriff also uses the actions of characters in the stage directions to comment on their weaknesses. For Stanhope especially there are repeated references to him drinking (“taking another whisky”, “… helping himself to another drink”, “Stanhope... helps the Sergeant-Major to a large tot, and takes one for himself”) and this seems to be, from the frequent references, a common occurrence. This suggests both that drinking itself is a weakness of Stanhope's, but also that it is driven by the stress placed on him by his role in the army and within the war itself. It is therefore possible to surmise that Stanhope is trapped in a cycle: he drinks to cope with his 'weaknesses' regarding his inability to cope with the pressures placed on him by the war, but he also drinks because he is so used to it. Stanhope appears to be an alcoholic, although there is a clear reason for his alcoholism.

Hibbert also drinks, but his motivations seem different from Stanhope's. He does use alcohol as a coping mechanism; when he tells Stanhope the real reason he wants to leave the trenches, becoming hysterical in the process, he gladly “takes the mug [of whisky] and drinks” as a way to calm himself down. Yet Hibbert seems to drink more socially than Stanhope; at the beginning of Act Three Scene Two he, Stanhope and Trotter are drinking from “two champagne bottles” and Hibbert's “high-pitched and excited” (and frequent) laughter suggests that he is drunk, but also that he is eager to please Stanhope by laughing at his jokes. This implies that Hibbert is keen to fit in and, factoring in his vain appearance, it seems as though other's opinions matter highly to him. This is another aspect of Hibbert's weakness, as well as the vice of drinking.

Unlike Hibbert and Stanhope, the Colonel does not abuse alcohol. Instead, his actions within the stage directions which relate to his weaknesses are mainly pauses. He generally only appears in the play when passing on important information to Stanhope, which is generally of a delicate nature and usually involves the loss of life. During these conversations the Colonel frequently pauses (“There is a pause”, “another pause” etc.). This indicates that he feels uncomfortable with what he is saying and with the loss of life, but prefers to ignore the issue rather than speak up or alter the plans. When he speaks “over his shoulder” to Osborne and Raleigh, who he is aware will be in grave danger on the raid he has sent them on, he further reinforces this. He cannot bear to face the men whose lives he has put in danger face-to-face, implying that he is cowardly in this respect.

Another dramatic device Sherriff uses is the language he actually chooses for each character's speech. There is far too much to analyse, even in an entire essay, so the most important point for each character in relation to human weakness is discussed here.

Stanhope has a very distinctive, public school voice. His speech contains typical middle/upper class vernacular such as “chaps”, “rotten”, “Lord, no”, “awfully” and “cheero”. Although this is not as pronounced as in Raleigh's speech (Sherriff probably intended this to show that Stanhope has more experience of the real world and the effect of visible class differences than Raleigh), it certainly sets Stanhope apart. However, by doing so Sherriff makes a statement that it is not just 'weak' men who suffer from the effects of war or from conditions such as alcoholism; these men can be strong, upstanding, middle or upper class, and well-educated, and still suffer in the same way as a man who appears physically and mentally weak. Sherriff seems to be directly targeting the audience, many of whom would no doubt have fitted, at least partially, what Stanhope represents here.

Hibbert, who up until Act Two Scene Two has appeared to be a character who fits the audience's stereotypes of a 'weak' man, reveals through the hyperbolic nature of his speech that his desire to return home is not due simply to cowardice. Here he attempts to be sent down the line due to his supposed neuralgia but Stanhope refuses to let him leave, prompting hysterics and a full explanation from Hibbert. Hibbert claims that he “shall die of this pain”, which shows the intensity of his suffering and how complete his desire to leave the trenches is, how desperate he has become. When Stanhope threatens him at gunpoint Hibbert says “Go on, then, shoot! … I swear I'll never go into those trenches again. Shoot! - and thank God -”. Here a completely different facet of Hibbert's weaknesses are uncovered; he is not just a coward or simply weak, for he would happily accept death rather than face going out of the dug-out and into the trenches again. This is not a decision to be made lightly and Hibbert, although speaking in quite a hyperbolic way, seems to be fully aware of the implications of his decision. That he actually encourages Stanhope to shoot when it seems as though Stanhope would willingly do so surely suggests that Hibbert had been broken by the war, just as Stanhope himself has.

Once again, the Colonel's use of language reinforces the concept of commanding officers who have no idea of the reality of warfare, or, if they do, choose to ignore it as long as they remain safe. The Colonel uses understated language when talking about the war, such as “good show”, which indicates his detachment from the war and the reality of what soldiers and officers on the frontline must face. The quotation indicates that he sees war as something of a game, which must be entertaining to watch, if not participate in. In addition, his description of taking prisoners when talking to Raleigh trivialises the entire war. He says that “one'll do [one German soldier], but bring more if you see any handy”, which is a phrase more suited to grocery shopping than to war. In only one sentence Sherriff manages to sum up perfectly the Colonel and other commanding officers' views of war; they are not required to risk their lives, but merely sit back and reap the rewards of it, while ignoring the dangers faced by others under their command.

The structure of the text also helps Sherriff present his views on human weakness. Both Hibbert and Stanhope speak in broken sentences when stressed; the use of dashes signifies this in the script (“If you went, I'd have you shot – for deserting. It's a hell of a disgrace – to die like that.”). The quotation in brackets is said by Stanhope, when Hibbert threatens to leave, and the dashes help signify Stanhope's tumultuous state of mind. The dashes also help to show how he is breaking down, as the sentence structure itself is disrupted. This is also true of Hibbert's broken sentences; a few lines later he says “every sound up there makes me all – cold and sick. I'm different to – to the others – you don't understand.” The language shows the extent of Hibbert's suffering, but it is the broken structure and frequent pauses which add impact and reinforce that Hibbert is on the edge of a complete breakdown.

The Colonel, unlike Hibbert and Stanhope, does not appear to be on the edge of a breakdown. He speaks in short, commanding sentences, as befitting a senior officer. His short sentences and brief answers to Stanhope, such as “Yes. I suggested that.” and “I'm afraid not. It's got to be done.” also convey that he doesn't wish to discuss what Stanhope is talking about (the raid). The abrupt effect this gives his speech fits with the previous conclusion that he wishes to ignore the dangers the soldiers face, and additionally implies that he is, to a degree, incapable of sympathising with Stanhope and others' views.

In 'Journey's End', Sherriff challenges commonly-held views of human weakness. He shows the audience through the character of Stanhope that even if someone appears outwardly strong and in control, they can still be considered 'weak'. He challenges the very concept of weakness, arguing through the prevalence of classically 'weak' behaviour in the play that what many people would have considered as being weak at the time the play was written and performed is in fact a perfectly logical response to war and combat situations. The view of weakness as being effeminate is also shown to be false through the fact that both Stanhope and Hibbert, such as when he says that he would rather die than go back into the trenches, can behave courageously, which is generally seen as a masculine characteristic. Sherriff also seems to conclude that mental disturbance is linked to warfare and, through the character of the Colonel, voices the opinion that this is partly because the officers do not see the soldiers as real people, but as pawns on a chessboard. Overall, Sherriff presents human weakness as something we all suffer from, albeit in different forms.

Document Details

- Word Count 2661

- Page Count 4

- Level AS and A Level

- Subject English

Related Essays

Explore the ways R.C. Sherriff presents the attitudes of key characters in...

How is Stanhope Represented in the First Two Acts of 'Journey's End'?

Explore Sheriff's presentation of the theme of the effects of war on soldie...

Comment on Sherriff's presentation of Stanhope in the first two acts of Jou...

Although a Play Journey End Is Primarily Concerned with Masculinity?

Although a play Journey end is primarily concerned with masculinity? Journey’s End shows the effect and horrors during the war. The irony of Journey’s End is the way it is set at the front line but we are faced with the mundane and passive elements of battle. The soldiers in Journey’s End talk about every topic but the war showing how they deal with the war in a masculine manner. Different characters in Journey End take different approaches to the war. Trotter seems to ignore his fate, and Stanhope accuses him of having no inner life at all.

In fact, Sherriff is careful to make it clear that this is not the case: ‘Always the same am I? (He sighs) Little you know,’ is Trotter’s answer to Stanhope, and it reveals a man – probably the strongest in character of all the officers – who faces death with remarkable good humour and toughness which shows true masculinity. His calendar shows Trotter’s ability to carry on a day-to-day existence of meals and duties without being constantly plagued by thoughts of death. In this, Trotter contrasts completely with the main character, Stanhope.

Stanhope is a young man who is erratic and unpredictable. He entered the war wanting to be a hero, and ends up carrying the burden of this image of heroism. Stanhope feels, ‘– as long as the hero’s a hero. ’ This shows him trying to be masculine and know it has become a burden. In the scene where Stanhope threatens to shoot Hibbert with his revolver it shows the way in which the weaker man is manipulated by the stronger it includes an important lesson in what lies at the core of Stanhope’s psychology. At the end of the ordeal Stanhope says to Hibbert Good man, Hibbert.

I liked the way you stuck that,’ it is as though he is inducting Hibbert into the mental state in which facing the certainty of death actually brings about a new strength of character. Showing that facing death is being truly masculine and anything other than that will make him a coward Hibbert is portrayed as weak in the play, representing a common situation that occurred during the period of the war; men doing everything they could to get away from the war Hibbert falsely claimed that he was suffering of neuralgia (sharp pain along the course of a nerve) in attempt to get sent home.

In this scene he tries to delay going up and out of the dug-out as much as possible and this is shown through stage directions and dialogue, ‘Hibbert sips his water very slowly, rinsing his mouth deliberately with every drop’, this illustrates how Hibbert was portrayed as a coward as he delayed leaving as much as possible Hearing the news about the German raid, Raleigh provokes sympathy for him because in the previous scene Raleigh thought the raid was all “Frightfully exciting. ” This just illuminates how naive and innocent he is which is what all the men were like at the beginning of the play.

In the final part of the scene, we

see how the relationship between Stanhope and Raleigh is more than just professional. As Stanhope hears of men getting wounded, he acts calmly and plans the best course of action to help them, but when he hears of Raleigh’s injury, he is affected by his friendship with Raleigh, and orders him to be bought down to the dugout. The war created a catalyst of changes including the masculinity of men. Traditional hegemonic roles were no longer intact. The war created many different types of men which this play portrays.

Related Posts

- Is "Hamlet" primarily a tragedy of revenge

- June focuses primarily on Mrs. Dalloway her circle

- Pride and Prejudice: Jane Austen's Life, Love, and Marriage Book Analysis

- The Awakening: A Novel of Edna Pontellier and Her Relationship Book Review

- Fielding and Defoe Concerns with the Issue of Morality in 'Joseph Andrews' Book Review

- Concerned To Ensure Flexibility Of Labour

- Death of a Salesman Is Not a Dramatic Hero: Willy Loman Book Analysis

- The great Gatsby is too concerned

- The Great Gatsby: A History of the Great Gatsby and a Historical Perspective Book Analysis

- Journey - Life of Pi, Journey to the Interior, the Red Tree

How about getting full access immediately?

- Relationships

10 Rules for a Modern Masculinity

The new masculinity playbook will give life more meaning..

Posted July 7, 2021 | Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

- Men need a shift from going it alone—the Atlas-like mentality needs to go.

- A shift to a modern masculinity is underway, whether we want it or not. If we open a conversation about it we can influence the direction.

- Solutions to hard questions emerge a level above the one where we're stuck. We are stuck on politics, political correctness, and stereotypes.

- Answers are found when we enter with a beginner's mind and question our programming so that we each find our unique path.

As longstanding cultural structures and stereotypes are being reevaluated, masculinity and manhood are in crisis. The old masculine stereotypes of being aggressive, privileged, and tough, while also being hypersexual and unemotional, are being dismantled. At the same time, we are also seeing these old stereotypes being re-embraced around the world.

In previous blog posts , we have discussed a softer form of the traditional masculinity concept of being the tough protector and sole provider in a family or a relationship. This notion puts extreme pressure on men, isolates them, and often leads to mental health struggles while also affecting relationships at work, at home, and amongst friends. This is what we call “The Atlas Complex of Men,” in which men carry the weight of the world on their shoulders alone and believe it will collapse unless they continue to do so.

With the aim of starting a constructive discussion about modern manhood and modern masculinity, the MANTORSHIFT Institute conducted a qualitative research project in the U.S., the U.K., France, Germany, Austria, Jordan and Iran. There were over 200 men interviewed of various age groups and backgrounds. In two previous posts I have summarized why we conducted this research and what were some of the first findings. In this final blog about this work, we report some of the remaining findings and provide some foundational ideas about what we call the Playbook for Modern Masculinity.

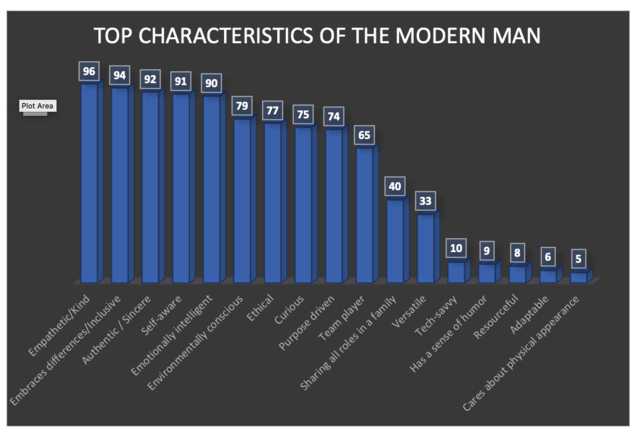

We have found that the five defining characteristics of a modern man are empathetic , inclusive, authentic, self-aware, and emotionally intelligent . The below diagram shows the top 17 characteristics that were named in the interviews.

It is widely agreed that an individual needs to find their own models, and no commonly agreed on or shared models are available. Most respondents can’t name someone who embodies modern masculinity or models the modern man for them.

Some politicians were mentioned as positive and negative examples. There was a very strong tendency, though, for citizens of a country to not highlight a politician from their own country. For example, several non-French respondents mentioned Emmanuel Macron as a good example of modern masculinity, while French respondents disagreed and, in fact, named him as someone who models the opposite. Others mentioned Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama as positive examples. Donald Trump was mentioned by many respondents as the antithesis of a modern man.

One question that inevitably comes up is, if we know what modern masculinity is, why don’t we do it? One important barrier is that men still experience high expectations from society and, increasingly, a negative bias . There are still high expectations for men to provide financially and protect physically; vulnerability is often met with confusion and disapproval from women. These expectations and associated shaming in turn can often fuel a bitter return to the belief of male superiority. In a highly image-conscious world where inner values are not widely recognized and only financial success matters, men find it increasingly difficult to remove their traditional masks and authentically express who they really are.

When asked for their advice to young men about how to avoid a return to traditional masculinity, most respondents focus on curiosity and learning, finding a unique path for manhood. They say it is built through acceptance and in conversation with others while also being resilient and courageous in discovering vulnerability and emotions.

After hearing from men around the world, we believe that a constructive dialogue about what it means to be a modern man should continue. This discussion needs to be not only among men but also between men and women. We don’t believe that shaming or making men feel guilty is useful in a constructive discussion, contrary to the current trend as seen in the controversial #MeToo Gillette ad in 2019.

If we want to gain new practitioners of modern masculinity, it is increasingly clear that instead of focusing the discussion on whether patriarchy existed or still exists, it is more useful to define the specific behaviors desired of men (and women) and the behaviors that no longer serve.

In summary, the 2020/21 MANTORSHIFT research specifically points to the following 10 core behaviors for men who want to find a healthy identity and masculinity. We see these points as the foundation for a new Playbook for Modern Masculinity:

- Listen and expose yourself to opinions that are different from your own in the media and in art.

- Meet and discuss with people who have different political and worldviews.

- Expose yourself to travel and different cultures in as many ways as possible.

- Always check the source of information that you are being served and do as much independent thinking and cross-checking as possible.

- Bring your attention to what you can do in your family, relationships, and the way you conduct business in terms of treating others, and find ways to become an ally to women.

- Strive to find a higher purpose in situations, rather than seek to understand what divides. This is best done by identifying higher level goals that might unite us rather than divide.

- Refrain from divisive political terminology (i.e., terms such as left or right, conservative or liberal) and instead focus on building a healthy community, creating deeper and healthy relationships, sustaining mental health, raising happier children and more such basic needs shared by all.

- Create a conversation with your partner about your goals, common goals, roles, and then revisit the discussion on a regular basis.

- Continue to develop and evolve your own understanding of what masculinity and being a modern man mean for you.

- Seek ways to integrate the two sides (traditionally referred to as yin-yang or masculine and feminine) in yourself so that you can be a more whole human being rather than a follower of your own cultural and societal programming. Don’t go it alone, reach out for professional help to coaches, men’s groups, and therapists.

Mickey Feher is a psychologist and serial entrepreneur. He is a coach and a facilitator who helps organizations and individuals discover their Higher Purpose and connect the two for better results and spirits.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Support Group

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Regeneration

Everything you need for every book you read..

During World War I, Dr. Rivers works as a psychiatrist in the Craiglockhart War Hospital in Scotland, treating British officers in various stages of mental breakdown. As a psychiatrist, Rivers is in a position to closely analyze the various pressures that soldiers feel during wartime, not only from the battlefield, but from society. The most powerful forces in a soldier’s life, Rivers observes, are the narrow expectations of masculinity and what it means to be a man, which often exacerbates his patients’ mental trauma. Through Rivers’s observations, Regeneration argues that in order to produce healthier men, society must redefine what it means to be a man, with far less emphasis placed on stereotypically masculine traits.

Both Rivers and his patients constantly feel pressured to behave in stereotypically masculine ways, suggesting that society at large expects all men to fit into a narrow ideal of what it means to be a man. Rivers observes that, although soldiers in World War I witness and directly experience horrific suffering, society expects them to remain absolutely stoic, suggesting that emotional repression is held up as a mark of masculinity. He notes, “They’d been trained to identify emotional repression as the essence of manliness. Men who broke down, or cried, or admitted to feeling fear were sissies, weaklings, failures. Not men .” However, such emotional repression often leads their minds to feel overwhelmed, triggering a psychological breakdown, suggesting that such masculine repression is deeply unhealthy. Fellow soldiers expect each other to fit into the stereotypical masculine ideal as well. One of Rivers’ patients, Second-Lieutenant Prior , recalls that even on the front lines in France, he sometimes felt belittled because he did not fit the stereotypical ideal: he did not hunt, he did not wear khaki shirts, and so on. This feeling of inadequacy suggests that men themselves are prone to judge each other’s manhood, as well as their own, by whether or not they behave in a supposedly masculine fashion. Even soldiers, who are often seen as the ideal of masculinity and bravery, are not exempt from these societal expectations. Prior’s father embodies society’s expectations for how a masculine man is supposed to behave. Although Prior had a debilitating mental breakdown (causing intermittent mutism) on the battlefield and requires psychiatric treatment, Prior’s father is dismissive of it, feeling that it makes him less than a man, since Prior was unable to remain stoic and endure the hardships. Prior’s father even tells Rivers that he wishes Prior had actually been shot, since then he might feel some level of sympathy for his son, suggesting that societal expectations are so strongly-held that Prior’s father would rather his own son be physically injured than to endure the shame of Prior not meeting society’s ideals of masculine strength.

As a psychiatrist, Rivers argues that while masculine ideals are not inherently wrong, in many instances they are counterproductive to the tasks at hand, and soldiers may even need to exhibit traits that society deems feminine. Rivers observes that although they will not admit it, officers take on a motherly role toward their men. An officer tends to his soldiers’ blistered feet on long marches, ensures that each man has the food and gear he needs to survive, and gives comfort as best he can when his soldiers are afraid. Rivers notes that the “perpetually harried expression” officers have while they speak of their men is exactly the same expression worn by impoverished mothers trying to sustain large families, “totally responsible for lives they have no power to save.” As Rivers observes, even in war, a seemingly masculine setting, officers must embody a stereotypically feminine role to care for and protect the lives of their troops, suggesting that masculine ideals are inadequate—and even harmful—in many situations.

As a psychiatrist, Rivers’s own style of treatment is notably feminine. Rather than stoically repressing his patients’ emotions, Rivers gently and patiently counsels his patients to feel their emotions, to cry or scream at the horrors of war as they need. Although Rivers’ goal is to recuperate his patients to the point that they can return to war, he does so by “nurturing,” not by threatening. One of his patients even refers to him as a “male mother.” Contrasting with Rivers’s feminine, nurturing approach to psychiatry, Dr. Yealland , whom Rivers witnesses working in London, takes a stereotypically masculine approach to psychiatry. Yealland holds a god-like view of his own power and authority, and tells his patients that he will unquestionably cure them within a single session. To treat a patient with mutism, Yealland locks himself and the man in a dark room and electrocutes the man, torturing him for hours until he regains a shaky ability to form words with his mouth once again. Although the patient is technically cured of mutism, Rivers can clearly see that his psychological trauma has only increased, implying that Rivers’s feminine, nurturing approach leads to a better long-term outcome than Yealland’s domineering, masculine method.

Rivers’s practice and observations do not argue that men should be emasculated or made effeminate, but suggests that society ought to reevaluate what it means to be a man, with less emphasis on meeting narrowly-defined and often inadequate masculine ideals. Rivers’s ultimate goal for his patients is to return them to the battlefield, and thus his treatment does not make “any encouragement of weakness or effeminacy.” Rather, Rivers recognizes that stereotypically feminine characteristics—tenderness, a nurturing spirit, emotional expression—are necessary even for men on the battlefield, arguing that society needs to loosen its strict expectations on men to meet a stoic, masculine ideal. However, Rivers also recognizes that such characteristics so contradict masculine ideals that “they could be admitted into consciousness only at the cost of redefining what it meant to be a man.” This ultimately suggests that in order to produce psychologically healthy men, society must adjust its view of manhood to allow for a balance between stereotypically masculine and feminine characteristics.

Pat Barker’s novel points out the extreme pressure that society exerts upon men to fit a narrow ideal of masculinity and argues that this concept of manhood needs to be redefined in much broader terms.

Masculinity, Expectations, and Psychological Health ThemeTracker

Masculinity, Expectations, and Psychological Health Quotes in Regeneration

“I mean, there was the riding, hunting, cricketing me, and then there was the…other side…that was interested in poetry and music, and things like that. And I didn’t seem able to…” He laced his fingers. “Knot them together.”

“I’ve worried everybody, haven’t I?”

“Never mind that. You’re back, that’s all that matters.”

All the way back to the hospital Burns had kept asking himself why he was going back, Now, waking up to find Rivers sitting by his bed, unaware of being observed, tired and patient, he’d realized he’d come back for this.

They’d been trained to identify emotional repression as the essence of manliness. Men who broke down, or cried, or admitted to feeling fear, were sissies, weaklings, failures. Not men. […] Fear, tenderness—these emotions were so despised that they could be admitted into consciousness only at the cost of redefining what it meant to be a man.

[Prior] didn’t know what to make of [Sarah], but then he was out of touch with women. They seemed to have changed so much during the war, to have expanded in all kinds of ways, whereas men over the same period had shrunk into a smaller and smaller space.

“You’re thinking of breakdown as a reaction to a single traumatic event, but it’s not like that. It’s more a matter of … erosion. Weeks and months of stress in a situation where you can’t get away from it.

[Rivers] distrusted the implication that nurturing, even when done by a man, remains female, as if the ability were borrowed, or even stolen from women […] If that were true, then there really was very little hope.

“It makes it difficult to go on, you know. When things like this keep happening to people you know and and …love. To go on with the protest, I mean.”

In his khaki, Prior moved among them like a ghost. Only Sarah connected him to the jostling crowd, and he put his hand around her, clasping her tightly, though at that moment he felt no stirring of desire.

“When all this is over, people who didn’t go to France, or didn’t do well in France—people of my generation, I mean—aren’t going to count for anything. This is the Club to end all Clubs.”

[Sassoon had] joked once or twice to Rivers about being his father confessor, but only now, faced with this second abandonment, did he realize how completely Rivers had come to take his father’s place. Well, that didn’t matter, did it? After all, if it came to substitute fathers, he might do a lot worse.

The bargain, Rivers thought, looking at Abraham and Isaac. The one on which all patriarchal societies are founded. If you, who are young and strong, will obey me, who am old and weak, even to the extent of being prepared to sacrifice your life, then in the course of time you will peacefully inherit, and be able to exact the same obedience from your sons.

Rivers thought how misleading it was to say that the war had “matured” these young men. It wasn’t true of his patients, and it certainly wasn’t true of Burns, in whom a prematurely aged man and fossilizes schoolboy seemed to exist side by side.

“You’re never gunna get engaged till you learn to keep your knees together. Yeh, you can laugh, but men don’t value what’s dished out for free. Mebbe they shouldn’t be like that, mebbe should all be different. But they are like that and your not gunna change them.”

“It’s only fair to tell you that…since that happened my affections have been running in more normal channels. I’ve been writing to a girl called Nancy Nicholson. I really think you’ll like her. She’s great fun. The…the only reason I’m telling you this is…I’d hate you to have any misconceptions. About me. I’d hate you to think I was homosexual even in thought. Even if it went no further.”

At the moment you hate me because I’ve been instrumental in getting you something you’re ashamed of wanting. I can’t do much about the hatred, but I do think you should look at the shame. Because it’s not really anything to be ashamed of , is it? Wanting to stay alive? You’d be a very strange sort of animal if you didn’t.

“You will leave this room when you are speaking normally. I know you do not want the treatment suspended now that you are making such progress. You are a noble fellow and these ideas which come into your mind and make you want to leave me do not represent your true self.”

‘Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead’ Review: A Remake That Remarkably Refashions Secondhand Goods

After her elderly babysitter dies, an enterprising teen fakes her way into a summer job at a dwindling fashion brand in this smart update of a cult comedy.

By Courtney Howard

Courtney Howard

- ‘Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead’ Review: A Remake That Remarkably Refashions Secondhand Goods 2 days ago

- ‘Arthur the King’ Review: Mark Wahlberg and a Very Good Dog Make For a Winning Combination in This Feelgood Drama 4 weeks ago

- ‘Glitter & Doom’ Review: Jukebox Musical Hits Right Notes With Indigo Girls Songs, Off Notes With Queer Love Story 1 month ago

Within its first few minutes, director Wade Allain-Marcus ’ “Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead” proves a worthy remake. Putting a modern comic spin on its ’90s counterpart’s opening sequence, it sets up our young heroine for a rude awakening and an indelible coming-of-age journey. By rearranging a few key details, losing some vestigial supporting characters and refocusing the story on a Black family learning to come together, the proceedings gain hilarity, buoyancy and resonance. Genuinely funny, charming and sincere, it’s a respectful and revelatory update in a world where those are few and far between.

Nonagenarian Ms. Sturak (June Squibb) isn’t the sweet old caretaker the kids expected. She’s unabashedly racist and rude. Thankfully her tyrannical reign comes to an abrupt end, as she expires in her sleep the first night. The savvy siblings must band together not only to dispose of the body (in a sequence with a solid self-aware joke at the expense of the 1991 film), but also to survive without cash or a guardian — and without disrupting their mother’s sanity. Tanya quickly learns she can’t get by on gig employment, so she forges her résumé to work at a flailing fashion company for the fabulously cool Rose ( Nicole Richie ). Yet just as things start to look up for the Crandells, they suffer a series of significant setbacks that land them in trouble.

The filmmakers shrewdly incorporate timely topics like fast fashion, food insecurity, toxic masculinity and privilege in a humorous, intelligent manner. The juvenile shenanigans that provide conflict are filled with tension — as predicaments like breaking an arm and dealing with cops are very different scenarios from the perspective of the Black Crandells as compared to their white predecessors.

Nostalgic nods to the original are deftly executed, with cameo appearances, quotable lines and soundtrack cues all placed with precision. While many of the first feature’s memorable squeeze zooms, close-ups, sharp edits and wardrobe accents are included as callbacks for eagle-eyed fans, Allain-Marcus and his team also apply their own signature aesthetic flourishes. A late title card drop hints that we’re in for a cool, creative mashup. Matt Clegg’s cinematography evokes tender romanticism when Tanya and her crush Bryan (Miles Fowler) are on dates, while there’s youthful fluidity in the camera movement, particularly when the family is gracefully circled during a second-act dinner scene. Production design on the Crandell house — filmed at the same Santa Clarita home as the original — reflects the family’s evolving state of togetherness, going from disrepair to gussied-up polish.

Jones nimbly negotiates her character’s awkward moments with vulnerability and impeccable comic timing. Hansley Jr. gives Kenny depth and dimension, while Young — handed a hilarious subplot as Zack befriends a murder of crows — and Sledge give star-making turns of their own. Richie genuinely sparkles in the role of Rose, talking in the delightfully-hurried pace of Rosalind Russell as if starring in her own ’40s-inspired screwball comedy.

A few gags fall flat (including one mention of factory-worker suicides) and there’s a nothingburger C-storyline involving Rose’s slimy paramour Gus (Jermaine Fowler), but the positive changes overshadow the flaws. Also notable is a sly commentary on the remake process itself: Eco-minded Tanya takes a sustainable approach to her job, creating chic wardrobes from upcycled fabrics and garments. Like the filmmakers, she takes the good parts of what was and fashions something fresh and fun for contemporary times.

Reviewed online, April 1, 2023. MPA Rating: R. Running time: 98 MIN.

- Production: Iconic Events Releasing presents a BET+ Original Film of a Spiral Stairs Entertainment Production in association with Treehouse Pictures, SMIZE Productions. Producers: Juliet Berman, Oren Segal, Justin Nappi, Juliana Maio. Executive producers: Maureen Guthman, Devin Griffin, Michael Phillips, Tova Laiter, Ryan Huffman, Tyra Banks, Neil Landau, Tara Ison, Chuck Hayward.

- Crew: Director: Wade Allain-Marcus. Screenplay: Chuck Hayward, based on the screenplay by Neil Landau and Tara Ison. Camera: Matt Clegg. Editor: Aric Lewis. Music: Jonathan Scott Friedman.

- With: Simone Joy Jones, Nicole Richie, Donielle T. Hansley Jr., Ayaamii Sledge, Carter Young, Miles Fowler, Iantha Richardson, Gus Kenworthy, June Squibb, Jermaine Fowler.

More From Our Brands

James mcavoy is a terrifying host in ‘speak no evil’ trailer, this luxe 157-foot catamaran lets you explore the galápagos with a butler on hand 24/7, espn, fubo push dueling arguments in streaming antitrust case, the best loofahs and body scrubbers, according to dermatologists, ahs: delicate turns back the clock, unmasking another familiar foe, verify it's you, please log in.

What Happened When Captain Cook Went Crazy

In “The Wide Wide Sea,” Hampton Sides offers a fuller picture of the British explorer’s final voyage to the Pacific islands.

The English explorer James Cook, circa 1765. Credit... Stock Montage/Getty Images

Supported by

- Share full article

By Doug Bock Clark

Doug Bock Clark is the author of “The Last Whalers: Three Years in the Far Pacific with a Courageous Tribe and a Vanishing Way of Life.”

- April 9, 2024

THE WIDE WIDE SEA: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook, by Hampton Sides

In January 1779, when the British explorer James Cook sailed into a volcanic bay known by Hawaiians as “the Pathway of the Gods,” he beheld thousands of people seemingly waiting for him on shore. Once he came on land, people prostrated themselves and chanted “Lono,” the name of a Hawaiian deity. Cook was bewildered.

It was as though the European mariner “had stepped into an ancient script for a cosmic pageant he knew nothing about,” Hampton Sides writes in “The Wide Wide Sea,” his propulsive and vivid history of Cook’s third and final voyage across the globe .

As Sides describes the encounter, Cook happened to arrive during a festival honoring Lono, sailing around the island in the same clockwise fashion favored by the god, possibly causing him to be mistaken as the divinity.

Sides, the author of several books on war and exploration, makes a symbolic pageant of his own of Cook’s last voyage, finding in it “a morally complicated tale that has left a lot for modern sensibilities to unravel and critique,” including the “historical seeds” of debates about “Eurocentrism,” “toxic masculinity” and “cultural appropriation.”

Cook’s two earlier global expeditions focused on scientific goals — first to observe the transit of Venus from the Pacific Ocean and then to make sure there was no extra continent in the middle of it. His final voyage, however, was inextricably bound up in colonialism: During the explorer’s second expedition, a young Polynesian man named Mai had persuaded the captain of one of Cook’s ships to bring him to London in the hope of acquiring guns to kill his Pacific islander enemies.

A few years later, George III commissioned Cook to return Mai to Polynesia on the way to searching for an Arctic passage to connect the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Mai brought along a menagerie of plants and livestock given to him by the king, who hoped that Mai would convert his native islands into a simulacra of the English countryside.

“The Wide Wide Sea” is not so much a story of “first contact” as one of Cook reckoning with the fallout of what he and others had wrought in expanding the map of Europe’s power. Retracing parts of his previous voyages while chauffeuring Mai, Cook is forced to confront the fact that his influence on groups he helped “discover” has not been universally positive. Sexually transmitted diseases introduced by his sailors on earlier expeditions have spread. Some Indigenous groups that once welcomed him have become hard bargainers, seeming primarily interested in the Europeans for their iron and trinkets.

Sides writes that Cook “saw himself as an explorer-scientist,” who “tried to follow an ethic of impartial observation born of the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution” and whose “descriptions of Indigenous peoples were tolerant and often quite sympathetic” by “the standards of his time.”

In Hawaii, he had been circling the island in a vain attempt to keep his crew from disembarking, finding lovers and spreading more gonorrhea. And despite the fact that he was ferrying Mai and his guns back to the Pacific, Cook also thought it generally better to avoid “political squabbles” among the civilizations he encountered.

But Cook’s actions on this final journey raised questions about his adherence to impartial observation. He responded to the theft of a single goat by sending his mariners on a multiday rampage to burn whole villages to force its return. His men worried that their captain’s “judgment — and his legendary equanimity — had begun to falter,” Sides writes. As the voyage progressed, Cook became startlingly free with the disciplinary whip on his crew.

“The Wide Wide Sea” presents Cook’s moral collapse as an enigma. Sides cites other historians’ arguments that lingering physical ailments — one suggests he picked up a parasite from some bad fish — might have darkened Cook’s mood. But his journals and ship logs, which dedicate hundreds of thousands of words to oceanic data, offer little to resolve the mystery. “In all those pages we rarely get a glimpse of Cook’s emotional world,” Sides notes, describing the explorer as “a technician, a cyborg, a navigational machine.”

The gaps in Cook’s interior journey stand out because of the incredible job Sides does in bringing to life Cook’s physical journey. New Zealand, Tahiti, Kamchatka, Hawaii and London come alive with you-are-there descriptions of gales, crushing ice packs and gun smoke, the set pieces of exploration and endurance that made these tales so hypnotizing when they first appeared. The earliest major account of Cook’s first Pacific expedition was one of the most popular publications of the 18th century.

But Sides isn’t just interested in retelling an adventure tale. He also wants to present it from a 21st-century point of view. “The Wide Wide Sea” fits neatly into a growing genre that includes David Grann’s “ The Wager ” and Candice Millard’s “ River of the Gods ,” in which famous expeditions, once told as swashbuckling stories of adventure, are recast within the tragic history of colonialism . Sides weaves in oral histories to show how Hawaiians and other Indigenous groups perceived Cook, and strives to bring to life ancient Polynesian cultures just as much as imperial England.

And yet, such modern retellings also force us to ask how different they really are from their predecessors, especially if much of their appeal lies in exactly the same derring-do that enthralled prior audiences. Parts of “The Wide Wide Sea” inevitably echo the storytelling of previous yarns, even if Sides self-consciously critiques them. Just as Cook, in retracing his earlier voyages, became enmeshed in the dubious consequences of his previous expeditions, so, too, does this newest retracing of his story becomes tangled in the historical ironies it seeks to transcend.

In the end, Mai got his guns home and shot his enemies, and the Hawaiians eventually realized that Cook was not a god. After straining their resources to outfit his ships, Cook tried to kidnap the king of Hawaii to force the return of a stolen boat. A confrontation ensued and the explorer was clubbed and stabbed to death, perhaps with a dagger made of a swordfish bill.

The British massacred many Hawaiians with firearms, put heads on poles and burned homes. Once accounts of these exploits reached England, they were multiplied by printing presses and spread across their world-spanning empire. The Hawaiians committed their losses to memory. And though the newest version of Cook’s story includes theirs, it’s still Cook’s story that we are retelling with each new age.

THE WIDE WIDE SEA : Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook, | By Hampton Sides | Doubleday | 408 pp. | $35

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

The actress Rebel Wilson, known for roles in the “Pitch Perfect” movies, gets vulnerable about her weight loss, sexuality and money in her new memoir.

“City in Ruins” is the third novel in Don Winslow’s Danny Ryan trilogy and, he says, his last book. He’s retiring in part to invest more time into political activism .

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist and author of “The Anxious Generation,” is “wildly optimistic” about Gen Z. Here’s why .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Advertisement

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The irony of Journey's End is the way it is set at the front line but we are faced with the mundane and passive elements of battle. The soldiers in Journey's End talk about every topic but the war showing how they deal with the war in a masculine manner. Different characters in Journey End take different approaches to the war.

The True Nature of War. The difference between the fantasy of war and its true, horrific and demoralizing nature is one of the play's major themes. The theme is most overtly revealed through Raleigh's character arc. When Raleigh first arrives, his boyish excitement at joining the war is shaken when he notices the quiet and the general lack of ...

Sherriff and Barker present in the play 'Journey's End' and the book 'Regeneration', respectively, the theme of masculinity being a prominent influence in the behaviour of soldiers, and furtherly was a great contribution to the psychological breakdown that we are presented with.

Journey's End is at heart about how men deal with almost certain death, constant fear, sudden and intense horror, attack and maiming. The play touched the hearts and minds of audiences watching ...

Journey's End is a 1928 dramatic play by English playwright R. C. Sherriff, set in the trenches near Saint-Quentin, Aisne, towards the end of the First World War.The story plays out in the officers' dugout of a British Army infantry company from 18 to 21 March 1918, providing a glimpse of the officers' lives in the last few days before Operation Michael.

Buy Study Guide. Journey's End Quotes and Analysis. Buy Study Guide. "I hope you get better luck than I did with my last officer. He got lumbago the first night and went home. Now he's got a job lecturing young officers on 'Life in the Front Line'." Captain Hardy, Act I, p. 10. Speaking with Osborne, Hardy mocks the common schemes that officers ...

An officer in Stanhope 's infantry. Trotter is jovial, irreverent, and gluttonous, frequently giving Mason —the cook—a hard time about the food served in the dugout. Although Trotter provides primarily comedic relief in Journey's End … read analysis of Trotter.

GCSE; Edexcel; Themes - Edexcel Social class in Journey's End. Sherriff uses World War One to explore a variety of themes - including the futility of war, class differences, courage and comradeship.

'Journey's End' is an anti-war play written by R. C. Sherriff. It deals with the effects of war on a select group of officers and has a static setting: the dugout of these officers. The play explores the way war affects men, the concept of masculinity, the exploitation of youth during the war, as well as class differences and other themes.

In Journey's End, Sherriff presents to the audience the cyclical nature of life during war. The soldiers in the trenches try to organize their lives around eating meals, drinking tea, sleeping, and taking orders, which ultimately adds a repetitious quality to their collective existence. Indeed, they are always either standing watch or waiting ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like effects of war + living up to heroic standards, stanhopes loss of empathy, damage to stanhopes personal relationships and more.

Journey's End Summary. Next. Act 1. In the first scene of Journey's End, Osborne arrives in the British trenches of St. Quentin, France in the last year of World War I. He is the second-in-command of an infantry stationed only 70 yards from the trenches of their Germany enemies. The nature of this kind of military service is quite intense ...

In Act 1, Hardy tells Osbornes that Stanhope came "straight from school" and that he has commanded the company for a year. KP1 - good leader. As a good leader: Respected by the men: "He's the best company commander we've got" and he leads by example by being the first to volunteer for the raid. KP1 - takes his good traits to the extreme.

Characters - Edexcel Stanhope in Journey's End Captain Dennis Stanhope is a flawed hero and the main character in this anti-war play. The play portrays soldiers with a variety of different ...

Unmatched as a theatrical response to the First World War, R. C. Sherriff's Journey's End focuses on the experience of soldiers and the conditions in which they fought and died through a socially diverse regiment of English soldiers hiding in trenches in France. Carefully following the requirements of GCSE English Literature assessment ...

This article offers an overview of studies of literary masculinities. After tracing their origins and development within the broader field of masculinity studies, it continues by illustrating the present applications of masculinity studies to literary criticism, ranging from studies of female to "ethnic" (i.e., both white and non-white) masculinities in literature, among others.

The irony of Journey's End is the way it is set at the front line but we are faced with the mundane and passive elements of battle. The soldiers in Journey's End talk about every topic but the war showing how they deal with the war in a masculine manner. Different characters in Journey End take different approaches to the war.

pursue idealized masculinity (Beyon, 64). Within these stories the hero thus becomes an image that must be upheld and is governed by specific expectations and a series of tasks that he must overcome. There is a formula that his journey must follow, a formula that has roots that go as far back as the time of the Anglo-Saxons in medieval Europe.

Whether you identify as male or are interested in exploring evolving gender roles, embracing this new era of masculinity is a collective journey that requires open-mindedness, self-reflection, and ...

Paul Theroux's 1981 novel, The Mosquito Coast, provides a critical analysis of American manhood, describing Allie Fox's pursuit of the "self-made man" in the late 1970s.Narrated by Charlie Fox, Allie's son, the novel presents the mechanism of the masculine subject: it is not so much a pregiven entity as an effect produced by the process of subjectivation, which is based on the body.

This time, the students reacted more quickly. "Take charge; be authoritative," said James, a sophomore. "Take risks," said Amanda, a sociology graduate student. "It means suppressing any ...

We have found that the five defining characteristics of a modern man are empathetic, inclusive, authentic, self-aware, and emotionally intelligent. The below diagram shows the top 17 ...

Masculinity, Expectations, and Psychological Health Theme Analysis. LitCharts assigns a color and icon to each theme in Regeneration, which you can use to track the themes throughout the work. During World War I, Dr. Rivers works as a psychiatrist in the Craiglockhart War Hospital in Scotland, treating British officers in various stages of ...

Within its first few minutes, director Wade Allain-Marcus ' "Don't Tell Mom the Babysitter's Dead" proves a worthy remake. Putting a modern comic spin on its '90s counterpart's ...

But Cook's actions on this final journey raised questions about his adherence to impartial observation. He responded to the theft of a single goat by sending his mariners on a multiday rampage ...