- Corrections

What was the Great Trek?

The Great Trek was a perilous exodus of pioneers into the heart of South Africa, looking for a place to call home.

When the British took control of Cape Town and the Cape Colony in the early 1800s, tensions grew between the new colonizers of British stock, and the old colonizers, the Boers, descendants of the original Dutch settlers. From 1835, the Boers would lead numerous expeditions out of the Cape Colony, traversing towards the interior of South Africa. Escaping British rule would come with a host of deadly challenges, and the Boers, seeking their own lands, would find themselves in direct conflict with the people who resided in the interior, most notably the Ndebele and the Zulu.

The “Great Trek” is a story of resentment, displacement, murder, war, and hope, and it forms one of the bloodiest chapters of South Africa’s notoriously violent history.

Origins of the Great Trek

The Cape was first colonized by the Dutch , when they landed there in 1652, and Cape Town quickly grew into a vital refueling station between Europe and the East Indies. The colony prospered and grew, with Dutch settlers taking up both urban and rural posts. In 1795, Britain invaded and took control of the Cape Colony, as it was Dutch possession, and Holland was under the control of the French Revolutionary government . After the war, the colony was handed back to Holland (the Batavian Republic) which in 1806, fell under French rule again. The British responded by annexing the Cape completely.

Under British rule, the colony underwent major administrative changes. The language of administration became English, and liberal changes were made which designated non-white servants as citizens. Britain, at the time, was adamantly anti-slavery, and was enacting laws to end it.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Tensions grew between the British and the Boers (farmers). In 1815, a Boer was arrested for assaulting one of his servants. Many other Boers rose up in rebellion in solidarity, culminating in five being hanged for insurrection. In 1834, legislation passed that all slaves were to be freed. The vast majority of Boer farmers owned slaves, and although they were offered compensation, travel to Britain was required to receive it which was impossible for many. Eventually, the Boers had had enough of British rule and decided to leave the Cape Colony in search of self-governance and new lands to farm. The Great Trek was about to begin.

The Trek Begins

Not all Afrikaners endorsed the Great Trek. In fact, only a fifth of the Cape’s Dutch-speaking people decided to take part. Most of the urbanized Dutch were actually content with British rule. Nevertheless, many Boers decided to leave. Thousands of Boers loaded up their wagons and proceeded to venture into the interior and towards peril.

The first wave of voortrekkers (pioneers) met with disaster. After setting out in September 1835, they crossed the Vaal River in January, 1836, and decided to split up, following differences between their leaders. Hans van Rensburg led a party of 49 settlers who trekked north into what is now Mozambique. His party was slain by an impi (force of warriors) of Soshangane. For van Rensburg and his party, the Great Trek was over. Only two children survived who were saved by a Zulu warrior. The other party of settlers, led by Louis Tregardt, settled near Delagoa Bay in southern Mozambique, where most of them perished from fever.

A third group led by Hendrik Potgieter, consisting of about 200 people, also ran into serious trouble. In August 1836, a Matabele patrol attacked Potgieter’s group, killing six men, two women, and six children. King Mzilikazi of the Matabele in what is now Zimbabwe decided to attack the Voortrekkers again, this time sending out an impi of 5,000 men. Local bushmen warned the Voortrekkers of the impi , and Potgieter had two days to prepare. He decided to prepare for battle, although doing so would leave all the Voortrekker’s cattle vulnerable.

The Voortrekkers arranged the wagons into a laager (defensive circle) and placed thorn branches underneath the wagons and in the gaps. Another defensive square of four wagons was placed inside the laager and covered with animal skins. Here, the women and children would be safe from spears thrown into the camp. The defenders numbered just 33 men and seven boys, each armed with two muzzle-loader rifles. They were outnumbered 150 to one.

As the battle commenced, the Voortrekkers rode out on horseback to harry the impi . This proved largely ineffective, and they withdrew to the laager. The attack on the laager only lasted for about half an hour, in which time, two Voortrekkers lost their lives, and about 400 Matabele warriors were killed or wounded. The Matabele were far more interested in taking the cattle and eventually made off with 50,000 sheep and goats and 5,000 cattle. Despite surviving through the day, the Battle of Vegkop was not a happy victory for the Voortrekkers. Three months later, with the help of the Tswana people, a Voortrekker-led raid managed to take back 6,500 cattle, which included some of the cattle plundered at Vegkop.

The following months saw revenge attacks led by the Voortrekkers. About 15 Matabele settlements were destroyed, and 1,000 warriors lost their lives. The Matabele abandoned the region. The Great Trek would continue with several other parties pioneering the way into the South African hinterland.

The Battle of Blood River

In February 1838, the Voortrekkers led by Piet Retief met with absolute disaster. Retief and his delegation were invited to the Zulu King Dingane ’s kraal (village) to negotiate a land treaty; however, Dingane betrayed the Voortrekkers. He had them all taken out to a hill outside the village and clubbed to death. Piet Retief was killed last so that he could watch his delegation being killed. In total, about 100 were murdered, and their bodies were left for the vultures and other scavengers.

Following this betrayal, King Dingane directed further attacks on unsuspecting Voortrekker settlements. This included the Weenen Massacre, in which 534 men, women, and children were slaughtered. This number includes KhoiKhoi and Basuto tribe members who accompanied them. Against a hostile Zulu nation, the Great Trek was doomed to fail.

The Voortrekkers decided to lead a punitive expedition, and under the guidance of Andries Pretorius, 464 men, along with 200 servants and two small cannons, prepared to engage the Zulu. After several weeks of trekking, Pretorius set up his laager along the Ncome River, purposefully avoiding geographic traps that would have led to a disaster in battle. His site offered protection on two sides by the Ncome River to the rear and a deep ditch on the left flank. The approach was treeless and offered no protection from any advancing attackers. On the morning of December 16, the Voortrekkers were greeted by the sight of six regiments of Zulu impis , numbering approximately 20,000 men.

For two hours, the Zulus attacked the laager in four waves, and each time they were repulsed with great casualties. The Voortrekkers used grapeshot in their muskets and their two cannons in order to maximize damage to the Zulus. After two hours, Pretorius ordered his men to ride out and attempt to break up the Zulu formations. The Zulus held for a while, but high casualties eventually forced them to scatter. With their army breaking, the Voortrekkers chased down and killed the fleeing Zulus for three hours. By the end of the battle, 3,000 Zulu lay dead (although historians dispute this number). By contrast, the Voortrekkers suffered only three injuries, including Andries Pretorius taking an assegai (Zulu spear) to the hand.

December 16 has been observed as a public holiday in the Boer Republics and South Africa ever since. It was known as The Day of the Covenant, The Day of the Vow, or Dingane’s Day. In 1995, after the fall of apartheid , the day was rebranded as “Day of Reconciliation.” Today the site on the west side of the Ncome River is home to the Blood River Monument and Museum Complex, while on the east side of the river stands the Ncome River Monument and Museum Complex dedicated to the Zulu people. The former has gone through many variations, with the latest version of the monument being 64 wagons cast in bronze. When it was unveiled in 1998, The then Minister of Home Affairs and Zulu tribal leader, Mangosuthu Buthelezi , apologized on behalf of the Zulu people for the murder of Piet Retief and his party during the Great Trek, while he also stressed the suffering of Zulus during apartheid.

The Zulu defeat added to further divisions in the Zulu Kingdom, which was plunged into a civil war between Dingane and his brother Mpande. Mpande, supported by the Voortrekkers, won the civil war in January 1840. This led to a significant decrease in threats to the Voortrekkers. Andries Pretorius and his Voortrekkers were able to recover Piet Retief’s body, along with his retinue, and give them burials. On Retief’s body was found the original treaty offering the trekkers land, and Pretorius was able to successfully negotiate with the Zulu over the establishment of a territory for the Voortrekkers. The Republic of Natalia was established in 1839, south of the Zulu Kingdom. However, the new republic was short-lived and was annexed by the British in 1843.

Nevertheless, the Great Trek could continue, and thus the waves of Voortrekkers continued. In the 1850s, two substantial Boer republics were established: The Republic of the Transvaal and the Republic of the Orange Free State . These republics would later come into conflict with the expanding British Empire.

The Great Trek as a Cultural Symbol

In the 1940s, Afrikaner nationalists used the Great Trek as a symbol to unite the Afrikaans people and promote cultural unity among them. This move was primarily responsible for the National Party winning the 1948 election and, later on, imposing apartheid on the country.

South Africa is a highly diverse country, and while the Great Trek remains a symbol of Afrikaner culture and history, it is also seen as an important part of South African history with lessons to learn from for all South Africans.

6 Crazy Facts about Cape Town

By Greg Beyer BA History & Linguistics, Journalism Diploma Greg specializes in African History. He holds a BA in History & Linguistics and a Journalism Diploma from the University of Cape Town. A former English teacher, he now excels in academic writing and pursues his passion for art through drawing and painting in his free time.

Frequently Read Together

British History: The Formation of Great Britain and the United Kingdom

The French Revolution in 5 Iconic Paintings

Mandela & the 1995 Rugby World Cup: A Match that Redefined a Nation

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

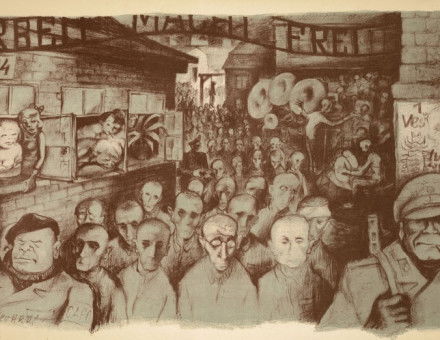

Great Trek Centenary Celebrations commence

Cameron, T. (ed) (1986) An Illustrated History of South Africa. Johannesburg, pp.258-259.|

Gilliomee, H. & Mbenga, B. (2007) New History of South Africa . Cape Town, pp.290-291.

Know something about this topic?

Towards a people's history

Subscription Offers

Give a Gift

The Great South African Trek

C.H.N. Routh records the travels and travails of the Boer pioneers

Heresies in history die hard; and the worst kind of school text-book, oversimplified and written down to the intelligence of the weakest pupils, helps to perpetuate popular errors. “Palmerston (we learn) fought the first Chinese War to force opium on to China,” or “The object of the Continental System was to starve out Great Britain. ...” A heresy that bears a charmed life teaches that the Great South African Trek was brought about by the abolition of slavery in 1833. The contention is that fury at the British government’s interference in the Boer way of life by this attack on their cherished system of slave labour, resentment at the financial losses incurred through inadequate compensation, and irritation at the inefficient machinery by which that compensation was to be paid, moved the frontier Boers to leave the colony in order to preserve slavery. Evidence is wholly against this reading. No doubt abolition increased the general irritation and added its quota to the growing resentment against the British government, but abolition itself would never have caused the Great Trek, and it cannot be regarded as the primary cause for the emigration.

To continue reading this article you will need to purchase access to the online archive.

Buy Online Access Buy Print & Archive Subscription

If you have already purchased access, or are a print & archive subscriber, please ensure you are logged in .

Please email [email protected] if you have any problems.

Popular articles

Slaying Myths: St George and the Dragon

South African information – tourism, history, culture of South Africa

- South Africa

- Kwazulu-Natal

- African Tribes

- game reserves

- Sport and Culture

- Natural Resources

- Transportation

- Food and Recipes

- Neigbouring Countries

The Great Trek

The Great Trek was the emigration of the Cape of Good Hope colonists in the 1830’s. This followed previous isolated treks of Dutch colonists who moved inland almost from the beginning of European Settlement in South Africa .

There were a number of reasons that caused the colonists who were mainly of Dutch origin to leave their homes and settle themselves inland and away from British rule.

One of the causes was that the British Colonial Office and their representatives did not have any understanding of the difficulties and problems of the Frontier farmers . These farmers were also disgruntled by the inadequate compensation paid for the slaves that had been liberated under the Emancipation Law . They were also dissatisfied about the return to the local Native tribes of the buffer territory called the “Province of Queen Adelaide” and of course their dislike of the tax laws that had been set up. Many British settlers sympathized with the Voortrekkers protests symbolized by the bible presented to a Voortrekker leader Piet Retief by the British colonists of Grahamstown.

One of the first organized parties of Voortrekkers to leave the Cape was that of Louis Trichardt who led a party together with a group under Jan Van Rensburg (about 30 wagons in all), across the frontier and moved north. Along the way Van Rensburg’s party separated from the original group and moved east and disappeared. Louis Trichard’s party after many hardships reach Lourenco Marques in Mozambique but most died from fever and the survivors returned back to Natal by ship.

In spite of dire warnings by Dutch Reformed clergy and Government officials other groups also began the long Trek to find a new home in the hinterland of South Africa. Among the chief leaders was Andries Hendrik Potgieter who reached what is present day Potchefstroom. Other groups settled in what is now the Free State where they established the town of Winburg.

P ieter Retief and Gerrit Maritz were leaders of the most important groups. In April 1837 Retief reached Thaba N’chu where he was elected Commander of 1000 emigrants and 6 months later he led an advance party across the Drakensberg into what is now Kwazulu-Natal and signed a treaty with Dingaan the Zulu chief at the time. They were invited to Dingaan’s Kraal where his party were murdered and an attempt was made by the Zulu’s to kill the survivors of his party at Blaauwkranz.

In December of 1838 the Voortrekkers defeated the Zulu warriors at the Battle of Blood River when Andries Pretorius defeated a Zulu army of 10,000 with a force of 460 Boers. After that the Great Trek would have ended if it were not for the fact that the British dispatched a force from the Cape and asserted British authority which resulted in further treks being undertaken by the Boers which led them to establish independent republics in the Free State and Transvaal . When the British Colony of Natal was set up this marked the end of the Great Trek.

Read more about the history of South Africa

Back to home page.

Briton and Boer in South Africa

IN order to understand the events which are occurring in South Africa, it is not enough to examine the terms of the Convention between Great Britain and the Transvaal, and to limit one’s inquiry to the question as to whether those terms have been observed. Although the results of such an inquiry might be sufficient to guide the action of statesmen, the student of politics requires more than this ; he would read the statesman’s dispatch in the light of historic evolution.

For the purpose of a brief review of the present situation, it is convenient to divide the history of South Africa into four periods: (1.) From the final British occupation of Cape Colony in 1814 to 1852, in which year the Transvaal became a separate state. (2.) From 1852 to 1877, the year in which England resumed sovereignty over the Transvaal. (3.) The revolt of 1880 and the Conventions of 1881 and 1884. (4.)

The growth of the Uitlander grievances since the reërection of the Transvaal in 1881.

At the outbreak of war between France and England in 1803, Cape Colony belonged to the Netherlands. In 1806 Louis Napoleon was made King of the Netherlands, and in the same year England attacked the Cape, as it was then a French possession. The Colony capitulated on January 10, 1806. The British occupation was made permanent by a Convention, signed in 1814, between Great Britain and the Netherlands, by the terms of which England paid thirty million dollars for the cession of the Cape Colony and of the Dutch colonies of Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo, which now form the colony of British Guiana.

It was hoped that the Dutch and the English in the Cape Colony would live together in friendly intercourse, and that eventually, by intermarriage, a fusion of the two races would be effected. This hope was doomed to disappointment, for an antagonism gradually developed between the old and the new colonists which led to the establishment of two republics beyond the border of the Colony. The first step toward the formation of these republics was the emigration during 1836 and 1837 of about eight thousand Dutch farmers from the Cape Colony, — a movement which is generally referred to as the Great Trek. These men went out of the Colony and established themselves in the vast hinterland. It is most important to understand the causes which led to the Great Trek. They were the misguided zeal of the English missionaries, the abolition of slavery with the safeguarding of the natives’ interests, and lastly, what Canon Knox Little describes as “ England’s fatuous policy of vacillation, betrayal, friction, irritation, postponing, changing, doing and undoing.”

The troubles with the missionaries began even before the Colony was ceded to England. In 1811, a certain Mr. Read, of the London Missionary Society, wrote a letter, which was widely circulated in England, in which he asserted that over one hundred murders of natives by the Dutch had been brought to his notice in his district, and that the Governor of the Colony remained deaf to the cry for justice. An inquiry was ordered by the Government, and every facility was given the natives of proving Mr. Read’s charges. After throwing the whole district into confusion by summoning over a thousand witnesses, many of whom were under arms on the frontier in expectation of a Kosa raid, the Circuit Court found that the charges were grossly exaggerated. The net result was the sending up for trial of five Dutchmen. George McCall Theal, in his History of South Africa, says in regard to this affair: “ The Black Circuit, as it was called, produced a lasting impression amongst the Dutch. It was no use telling the people that the trials had shown the missionaries to have been the dupes of idle story-tellers. The extraordinary efforts made to search for cases and to conduct the prosecutions appeared in their eyes as a fixed determination on the part of the English authorities to punish them, if by any means a pretext could be found. As for the missionaries of the London Society, from that time they were held by the frontier colonists to be slanderers and public enemies.” That the actions of the missionaries really influenced the Dutch in their determination to leave the Colony is shown by a manifesto published by Pieter Retief, one of the most prominent trekkers, to show why British rule was no longer endurable. The fourth paragraph of the manifesto says : “ We complain of the unjustifiable odium which has been cast upon us by interested and dishonest persons, under the name of religion, whose testimony is believed in England to the exclusion of all evidence in our favor; and we can foresee, as the result of this prejudice, nothing but the total ruin of the country.”

But a more important cause of discontent lay in the policy of protection of native interests which was vigorously enforced by the British authorities. As early as 1815 the ill treatment of the natives by the Dutch produced great friction. In that year a complaint was laid before a magistrate against one Frederik Bezuidenhout, for assault on a native servant. A summons to appear was disregarded, and a warrant was issued for the man’s arrest. Every effort was made to effect the arrest peaceably ; but the man surrounded himself with a band of his friends, and fired on the party detailed to make the arrest. A fight ensued, in which Bezuidenhout was killed and thirty-nine of his comrades were arrested. They were tried by jury before the High Court, and five of them were condemned to death. This affair is constantly recited by the Boers at public meetings, in order to inflame the people against the English. An entirely new light is thrown on the matter by Canon Knox Little in his Sketches and Studies in South Africa. He asserts that the Dutch Fieldcornet, under whose immediate orders the execution was carried out, had in his pocket, at the time of the execution, the Governor’s order for the pardon of the prisoners ; that he suppressed it from motives of personal spite ; and that afterwards, fearing detection, he committed suicide. It is unfortunate that Canon Knox Little does not quote the authority which he undoubtedly must have for this version, for the facts as he states them are not to be found in any history of South Africa with which I am familiar.

I now pass to a question which is at the bottom of a great deal of the ill feeling between the Dutch and the English, — the abolition of slavery. The Emancipation Act came into force in Cape Colony on December 1, 1834, the number of slaves in the Colony at that time being about forty thousand, mostly in the hands of the Dutch. The value of these slaves was three million pounds sterling, but the Imperial Government awarded only a million and a quarter as compensation. In this respect the Dutch slaveholders were no worse off than the West Indian slaveholders, but they undoubtedly had a grievance in the fact that the compensation was made payable in London.

George McCall Theal, the historian of South Africa, says that the abolition of slavery had little to do with the Great Trek ; but in this opinion he stands alone amongst writers on South African history. It is difficult, indeed, to reconcile his view with the terms in which he describes the effect of abolition on the minds of the Dutch. He says : " It is not easy to bring home to the mind the widespread misery that was occasioned by the confiscation of two millions’ worth of property in a small and poor community like that of the Cape in 1835. There were to be seen families reduced from affluence to want, widows and orphans made destitute, poverty and anxiety brought into hundreds of homes.” Pieter Retief stated in his manifesto that the abolition of slavery was one of the reasons why his band was leaving the Colony. Another powerful cause of discontent was the attitude of the Colonial Office in regard to the Kaffir war of 1834—35. On December 21, 1834, twelve thousand armed Kaffirs raided the Colony, and it was only after severe fighting that the Dutch farmers succeeded in driving them back over the Kei River. Sir Benjamin D’Urban, Governor of the Colony, extended the boundary of the Colony to the Kei River, in the hope that the strong natural barrier which it afforded would keep the two races from further conflict. Unfortunately, Lord Glenelg, Secretary of State for the Colonial and War Departments, entirely misunderstanding the situation, ordered the restoration of the territory to the Kaffirs. This action, which finds a parallel in more recent South African history, had the most far-reaching results. It disheartened the Boers who had shed their blood in upholding what they believed to be the honor of England, and at the same time encouraged the Kaffirs to further outrages.

Thoroughly disgusted with British rule, about eight thousand Boers left the Colony, and the Great Trek was accomplished. If ever men had reason to turn their backs on an unjust and unfaithful government, the Boers had, when, after losing their property and after being deprived of the fruits of victory, they inspanned their oxen and went out into the wilderness.

I cannot refer here to the early adventures of the trekkers. Suffice it to say that, after much fighting with the natives, and a great deal of vacillation on the part of the British Government, the independence of the Transvaal Boers was recognized by the Sand River Convention in 1852, and the Orange Free State was established as an independent republic in 1854.

The story of the Transvaal from 1852 to 1877 is one of continual strife and discord. The Boers were divided amongst themselves, and formed four small republics, which did little but quarrel with one another over religious and political questions. Occasionally they combined to fight the natives, with whom they never succeeded in establishing friendly relations. In 1857 the internal dissensions were varied by a raid into the Orange Free State. One of the objects of the raid was to compel the Free State to enter into confederation with the Transvaal, and one of the officers in command of the raiding party was S. J. P. Kruger, now President of the Transvaal, The raiding party found itself face to face with a large body of armed Free State burghers, and Kruger was sent in with a flag of truce to seek terms. The Orange Free State would not hear of confederation with the Transvaal, but yielded on one point, which is of great interest at the present time. This point is contained in Article 7 of the treaty concluded on that occasion, which runs: “ The deputies of the Orange Free State promise to grant and extend within their state the same rights and privileges to the burghers and subjects of the South African Republic as shall be afforded to those of the Cape of Good Hope and Natal.”

So it is seen that in 1857 Kruger was prepared to exact by force of arms from the Orange Free State the political rights of Transvaal Uitlanders in the sister republic.

At length matters came to such a pass in the Transvaal that the peace of the whole of South Africa was threatened. Notwithstanding an express agreement to the contrary in the Sand River Convention, the Boers persistently practiced slavery, and made a habit of raiding friendly native kraals for the purpose of carrying off the women and children. Since this has been repeatedly denied during the past few months, I think it well to put the fact beyond dispute by quoting from four independent sources. British Blue Book C. 1776, published in 1877, says : “ Slavery has occurred not only here and there in isolated cases, but as an unbroken practice has been one of the peculiar institutions of the country. It has been at the root of most of its wars.” Dr. Nachtigal, of the Berlin Missionary Society, wrote to President Burgers, of the Transvaal, in 1875 : “ If I am asked to say conscientiously whether such slavery has existed since 1852, and been recognized and permitted by the Government, I must answer in the affirmative.” A Dutch clergyman named P. Huet, in a volume published in 1869 entitled Het Afrikaansche Republiek, says: “Till their twenty-second year they [the natives] are apprenticed. All this time they have to serve without payment. It is slavery in the fullest sense of the word.” In 1876, one year before the annexation, Khame, Chief of the Bagamangwato, sent a petition to Queen Victoria. It ran in part: “I, Khame, King of the Bagamangwato, greet Victoria, the Great Queen of the English people. I ask her Majesty to pity me, and to hear what I write quickly. The Boers are coming into my country, and I do not like them. . . . They sell us and our children. The custom of the Boers has always been to cause people to be sold, and to-day they are still selling people.” This fourfold testimony seems to leave little room for doubt.

But what concerned England very nearly was the constant danger of the wars in the Transvaal spreading to British territory, — a danger which increased from year to year, as the republic sank deeper into financial embarrassment. The Boers had never been willing to pay taxes, and at last even the money for current expenses was not forthcoming. In view of these facts, the British Government sent out Sir Theophilus Shepstone in 1876 to visit the Transvaal and inquire into its condition. He was authorized to annex the Transvaal, if he found such a course necessary in the interests of peace and safety, provided the inhabitants or a sufficient number of the legislature were willing. Sir Theophilus Shepstone entered the Transvaal with the knowledge of President Burgers, and proceeded to Pretoria. He was accompanied by twenty-five mounted police, the only force he had within a month’s march of him during the whole period of his stay, and at the time he issued the proclamation annexing the country. To assert that the Transvaal was forcibly annexed is, in the face of these facts, absurd. Shepstone took eighteen days to reach Pretoria. His progress was marked by the presentation of numbers of addresses and memorials, from Dutch, English, and natives, praying him to take over the country. But he was not prepared to do this until he had satisfied himself that the needed reforms could not be carried out by the Dutch themselves without British aid.

After spending three months in the country he sent home a dispatch, dated March 6, 1877, in which he thus described the condition of the republic:

“ It was patent to every observer that the government was powerless to control either its white citizens or its native subjects ; that it was incapable of enforcing its laws or of collecting its taxes ; that the salaries of officials had been, and are, four months in arrears ; that the white inhabitants had become split into factions ; that the large native population within the boundaries of the state ignore its authority and laws ; and that the powerful Zulu King, Cetewayo, is anxious to seize the first opportunity of attacking a country the conduct of whose warriors has convinced him that it can be easily conquered by his clamoring regiments.”

But he was not willing to recommend annexation, if the people of the country were ready to undertake reforms. In fact, President Burgers submitted to Shepstone a new constitution so satisfactory that he declared “ he would abandon his design of annexation, if the Volksraad would adopt these measures, and the country be willing to submit to them and carry them out.” The Volksraad, however, refused to adopt the new constitution, whereupon Burgers proclaimed it on his own responsibility, — an act which was immediately condemned by the Executive Council. Then President Burgers advised the Volksraad to accept the British annexation. His language was unmistakable. Speaking on March 3 and on March 5, 1877, he told the Volksraad that it would be folly to hope that things would mend themselves. The bitter truth was that matters were as bad as they could be, and that the appeal for help to the British Government had not come from enemies of the state, but had arisen through the grievances which existed as a result of the demoralization of the people themselves. Their duty was to come to an agreement with the British Government.

Sir Theophilus Shepstone annexed the country to the British Crown on April 12, 1877. A formal protest was entered by the Boer Executive Council. That it was merely formal is proved by the fact that each member of the Council, except Paul Kruger, signified in writing his willingness to serve the new government; and Kruger himself drew his salary as a member of the Executive Council for eight months after annexation, having applied for and received his pay up to the end of the year, although his term of office ended on November 4.

There can be no doubt whatever that at the time of the annexation of the Transvaal, in 1877, the majority of the Boers were willing, and that many of them were anxious, to be taken under British rule. The only element of discord was a small band of ultra-conservatives, who, after precipitating the annexation by fostering internal strife, were now ready, their tactics having overthrown Burgers, to undertake an antiBritish agitation in the interest of Kruger’s candidature for the presidency, the success of which meant the retrocession of the country from the British flag.

Nothing would have come of this movement had it not been for the incredible folly of the British Government. At a time when it was above all things necessary to keep faith with the Boers, when a firm adherence to the promises contained in the proclamation of Sir Theophilus Shepstone would have strengthened the pro-British feeling, and at the same time have cut the ground from under the feet of the agitators, a policy was pursued which, though free from that depth of baseness which marked the actions of the Gladstone administration in 1881, was so thoroughly ill advised that we can only wonder that when the revolt broke out in 1880 there were still to be found in the country a considerable number of men who adhered to the British.

The first mistake was in allowing an unnecessary delay in establishing an electoral government. This was followed by the recall of Shepstone, — who was liked and respected by the Boers, — on the ground that his expenditure was excessive, and the appointment of Colonel Lanyon in his place. Lanyon possessed those excellent qualities which so well befit a soldier, but which are unsuitable for administrative work ; and his precise and rigorous methods made him most unpopular with the Boers. Everything worked well for Kruger and his party ; for Sir Bartle Frere, the one man who, in the absence of Shepstone, might have set matters right, was recalled, and his duties in the Transvaal were handed over to Sir Garnet Wolseley.

During the agitation which led to the revolt of 1880, the pro-British Boers, becoming anxious at the preparations going on around them, sought to be reassured by the British Government that the annexation would not be revoked. This assurance was repeatedly given in the most solemn and authoritative manner. Sir Garnet Wolseley was authorized by the British Cabinet to make the following proclamation: “ I do proclaim and make known, in the name and on behalf of her Majesty the Queen, that it is the will and determination of her Majesty’s Government that this Transvaal territory shall be and shall continue to be forever an integral portion of her Majesty’s dominions.” On another occasion Sir Garnet Wolseley said : “So long as the sun shines the Transvaal will remain British territory.” This was confirmed by Sir Michael Hicks Beach, Secretary of State for the Colonies, who, on being informed that certain persons entertained “ the false and dangerous idea that her Majesty was not resolved to maintain her sovereignty over this territory,” telegraphed to Sir Garnet Wolseley : “ You may fully confirm explicit statements made from time to time as to inability of her Majesty’s Government to entertain any proposal for withdrawal of Queen’s sovereignty.”

One important voice was raised against this view. Mr. Gladstone, speaking during his Midlothian campaign in March, 1880, said : “ If those acquisitions [Cyprus and the Transvaal] were as valuable as they are valueless, I would repudiate them, because they were obtained by means dishonorable to the character of this country.”

Less than two months after the delivery of this speech Gladstone came into power. A month later he received from Messrs. Kruger and Joubert a letter, in which they prayed that he would give effect to the sentiments he had expressed so unequivocally by restoring the independence of the Transvaal. Mr. Gladstone replied : “It is undoubtedly a matter for much regret that it should, since the annexation, have appeared that so large a number of the population of Dutch origin in the Transvaal are opposed to the annexation of that territory ; but it is impossible now to consider that question as if it were presented for the first time. Looking at all the circumstances, our judgment is that the Queen cannot be advised to relinquish her sovereignty over the Transvaal.” From this letter the loyalist party in the Transvaal took heart of grace. Things were evidently on a permanent basis, when even the leading advocate for repudiation declared his deliberate opinion that the Transvaal must remain British territory.

But on December 13, 1880, Kruger and his associates proclaimed the South African Republic. The Boer war followed, which lasted until March, 1881. The Boers fought with great bravery, and the British forces were defeated in several small engagements. Large British reinforcements were on the way, and the Boers would soon have been outnumbered and overmatched, when Gladstone sent out to say that if the Boers would lay down their arms they should be accorded complete self-government subject to British suzerainty. What had been refused by Gladstone to petition and entreaty was to be given as the reward of rebellion.

The natives in and around the Transvaal had been eager to fight for the British, but had been prevented from doing so by the British authorities, who felt that the general interests of peace in South Africa would thus be imperiled. A large number of loyal Boers and British fought with the regular troops, placing their faith in the repeated assurances of the British Government that under no circumstances would the Transvaal be given up. The position of these loyalists after the surrender was deplorable. Their grievances were eloquently set forth by Mr. C. K. White, president of the Committee of Loyal Inhabitants of the Transvaal, who wrote to Mr. Gladstone :

“ I, for one, opposed the Government strenuously on one occasion, at least; but when the sword was drawn, and it came to being an enemy or loyal, we all of us came to the front and strove to do our duty, in full dependence on the pledged and, as we hoped, the inviolate word of England. And now it is very bitter for us to find that we trusted in vain ; that, notwithstanding our sufferings and privations, in which our wives and children had to bear their share, we are to be dealt with as clamorous claimants, and told that we are too pronounced in our views. If, sir, you had seen, as I have seen, promising young citizens of Pretoria dying of wounds received for their country ; if you had seen the privations and discomforts which delicate women and children bore without murmuring for upwards of three months ; if you had seen strong men crying like children at the cruel and undeserved desertion of England ; and if you had invested your all on the strength of the word of England, and now saw yourself beggared by the act of the country in which you trusted, you would, sir, I think, be 'pronounced.' ” It is not recorded that Gladstone replied to this letter.

Nothing was gained by the surrender but national dishonor. The rebels had already been betrayed by Mr. Gladstone, and they saw, therefore, only cowardice where they were expected to see magnanimity. The loyalists, on the other hand, and with them the natives, were handed over to their enemies, with nothing to remember but the deliberate breaking of those most solemn and emphatic pledges which had been their stay and comfort during the trials of the rebellion. There should have been either no fighting or more fighting. The idea was well expressed by Lord Cairns. Speaking in the House of Lords, he said : " I want to know what we have been fighting about. If this arrangement is what was intended, why did you not give it at once ? Why did you spend the blood and treasure of the country like water, only to give at the end what you had intended to give at the beginning ? We know that there are those who have lost in the Transvaal that which was dearer to them than the light of their eyes. They have been consoled with the reflection that the brave men who died, died fighting for their Queen and country. Are the mourners now to be told that these men were fighting for a country which the Government had determined to abandon, and that they were fighting for a Queen who was no longer to be sovereign of that country ? ”

The formal instrument restoring the Transvaal to the Boers was the Pretoria Convention, signed and published on August 3, 1881. The articles of this Convention were amended and altered by the London Convention of February 27, 1884. The points of interest in regard to these Conventions are dealt with in the last section of this article.

From the date of the signing of the London Convention has gradually been accumulating that mass of grievances of British subjects in the Transvaal which forms the backbone of the present difficulties between Great Britain and the South African Republic. In 1895, a petition praying for redress, signed by thirty-eight thousand Uitlanders, was presented to the Volksraad, and was rejected with insult and ridicule, one member saying that if the Uitlanders wanted any rights they had better fight for them. On December 26, 1895, a manifesto was issued by the Transvaal National Union, in which the demands of the Uitlanders were stated. The principal demands were, the establishment of the republic as a true republic ; a constitution framed by the representatives of the whole people, which should be safeguarded against hasty alteration ; an equitable franchise law ; and the independence of the courts of justice. If these demands were not granted, it was decided to attempt the overthrow of the government by force of arms. Owing to misunderstandings, Dr. Jameson, of the British South Africa Company, who with a body of men was on the frontier ready to give aid if fighting were resorted to, entered the Transvaal with his force before the time appointed, and thus entirely destroyed the plans of the National Union. The story of the Jameson Raid is too long to enter into ; but it may be remarked that every effort was made by the High Commissioner and by Cecil Rhodes to recall Jameson before he met the Boers, that the Raid was promptly condemned by the British authorities, and that Dr. Jameson and his officers were subsequently tried, convicted, and imprisoned by a British court of justice, for violation of the Foreign Enlistments Act. The most important fact to be noted in connection with the proposed Johannesburg rising and the Raid is that they were planned and subscribed to only after the most solemn assurances had been given that there was to be no attempt to bring the Transvaal under the British flag, and that if the plan succeeded a true republic should be formed.

The four Johannesburg leaders of the National Union were sentenced to death ; but this sentence was subsequently altered to fifteen years’ imprisonment, and finally to a fine of $100,000. Fifty-nine of the men who formed the Reform Committee were imprisoned for some months, and had to pay a fine of $10,000 each. An attempt was made to connect Mr. Chamberlain with the Raid, but this entirely failed.

As might naturally be expected, the lot of the Uitlanders, after the Jameson Raid, became harder and harder, notwithstanding the fact that President Kruger solemnly promised, after Jameson’s men had laid down their arms, that he would inquire into and redress their grievances. At length, on March 24 of the present year, a petition signed by 21,648 Uitlanders was forwarded by the High Commissioner to her Majesty, praying that she would intervene to secure just treatment for the Uitlanders, who, whilst paying five sixths of the taxes of the state, had no voice in its government.

The chief grounds for the petition were stated to be, the failure of President Kruger to institute the reforms promised after the Jameson Raid ; the continuation of the dynamite monopoly and its attendant grievances, notwithstanding the fact that a government commission, consisting of officials of the republic, had inquired into the matter and suggested many reforms ; the subjugation of the High Court to the executive authority, and the dismissal of the chief justice for his earnest protest against the interference with the court’s independence ; 1 the selection of none hut burghers to sit on juries ; the aggressive attitude of the police toward the Uitlanders, culminating in the murder of a man named Edgar, who was shot by a policeman when in his own house and unarmed ; taxation without representation ; and the withholding of educational privileges from the children of Uitlanders. Though it is impossible, within the limits of this article, to review the evidence for these statements, there seems to be no reason to doubt that the assertions of the Uitlanders are correct. After some correspondence between the two governments, and a friendly suggestion from the President of the Orange Free State, a conference was arranged between Sir Alfred Milner, the High Commissioner of South Africa, and President Kruger. The conference took place at Bloomfontein, the capital of the Orange Free State, and lasted from May 31 to June 5. I have before me a verbatim report of the proceedings.

The position taken by Sir Alfred Milner was that there were a number of open questions between the two governments, which increased in importance as time went on, and that the tone of the controversy was becoming more acute. There were two methods by which things could be settled: one was by giving the Uitlanders such fair proportion of representation in the first Yolksraad as would enable them to work out gradually the needed reforms ; the other, for the Government of Great Britain to adopt that course which, in similar circumstances, would be adopted in regard to grievances of British subjects in any country, even in a country not under specified conventional obligations to her Majesty’s Government ; that is, by raising each point separately, and showing how the intense discontent of British subjects stood in the way of that friendly relation which it was desired should exist between the two governments. Of these two methods, Sir Alfred Milner thought that the former would be the better ; for if a fair franchise were granted to the Uitlanders, most of the questions pending between the two governments could be dropped as specific issues, and the remaining ones could be settled by friendly discussion. If he could persuade President Kruger to grant a fair franchise, all that was needed to set things right would then he effected by a movement within the state, the danger of continual and irritating pressure from outside would be removed, and the independence of the republic would be strengthened. Sir Alfred Milner pointed out that the existing franchise law compelled an alien, after renouncing allegiance to his own government, to wait twelve years before he was granted citizenship in the Transvaal, and that even then there was much uncertainty whether he would get the franchise. It was to be recalled that those men who had come into the republic in 1886, and had been promised citizenship at the end of five years, were informed, just before the term of five years ended, that the law had been changed, and they would have to wait seven years longer.

Sir Alfred Milner then proposed that the franchise should be granted to every white man who had been five years in the country, and was prepared to take oath to obey the laws, to undertake all the obligations of citizenship, and to defend the independence of the country ; it being understood that by taking such an oath he renounced his citizenship of any other country. A property qualification and good character were to be conditions. The assertion has been frequently made that Sir Alfred Milner wished to secure the citizenship of the Transvaal for British subjects under conditions which would still allow them to remain British subjects; but I find no foundation for this statement.

In reply to this proposal, President Kruger urged that the Uitlanders did not want the franchise, and would not take it on any terms ; and also, that if he granted Sir Alfred Milner’s request the country would be controlled by foreigners, and all power taken from the old burghers, — propositions which are mutually destructive. But on the third day of the conference President Kruger himself presented a new franchise proposal. This was passed by the Volksraad at once, before the British authorities had any time to examine it. After it was published, it appeared on its very face so full of intricacies that its effect as a measure of reform was a matter of serious doubt. Under its terms an alien could apparently secure the franchise in seven years, but the conditions were so complicated that to fulfill them was impossible. To give only one example : A man who desired the franchise must first signify his intention in writing to the Fieldcornet, the Landdrost, and the State Secretary. Two years later he might become naturalized (without receiving full burgher rights), provided he produced a certificate, signed by the Fieldcornet, the Landdrost, and the Commandant of the district, to the effect that he had never broken any of the laws of the republic. If these officials were not sufficiently well acquainted with the private life of the applicant to grant such a certificate, then a sworn statement to the same effect from two prominent full burghers would suffice. At the termination of another five years, the applicant, having six months previously signified his intentions in writing to the Fieldcornet, the Landdrost, and the State Secretary, might apply for the full franchise. He must then furnish the certificate alluded to above. This, together with his application, must be indorsed by the Fieldcornet and the Landdrost. Both were then to be passed to the State Secretary, who should hand them on to the State Attorney, who should return them with a legal opinion to the State Secretary. If the opinion were favorable, the man might be granted the full franchise ; if not, the matter was to be referred to the Executive Council.

If this account appears involved, I can only refer my readers to the law itself, when it will be seen that I have selected for explanation by no means the most complicated conditions.

In view of the opinion expressed by Sir Alfred Milner and prominent Uitlanders that on the face of it the law appeared almost unworkable, Mr. Chamberlain telegraphed, asking for the appointment of delegates from the Transvaal and from the British side to discuss the new law, to see if it would as a matter of fact effect the needed reforms. To Mr. Chamberlain’s request for a joint inquiry the Transvaal government sent a reply in which nothing was said about the joint inquiry, but in which a proposal was made for a new franchise law. The basis of the new proposal was a five years’ retrospective franchise. The following conditions, which I take verbatim from the Transvaal government’s official translation of its note, were attached : The proposals of this government regarding questions of franchise and representation must be regarded as expressly conditional on her Majesty’s Government consenting to the points set forth in paragraph 5 of that dispatch, namely : (a.) In future not to interfere in internal affairs of the South African Republic. (A) Not to insist further on its assertion of existence of suzerainty. (c.) To agree to arbitration. Further, it was explicitly stated by the State Attorney that these offers could only be understood to stand if England decided not to press her request for a joint inquiry into the political representation of the Uitlanders. There can he no doubt about this rejection of the joint inquiry, for the draught of the telegram in which the British agent conveyed the suggestions to Sir Alfred Milner was initialed by the State Attorney himself.

In reply, Mr. Chamberlain said he was prepared to waive the joint inquiry if the British agent, assisted by competent men, should be allowed to investigate the terms of the proposal. In regard to intervention, her Majesty’s Government hoped that the fulfillment of the promises made, and the just treatment of the Uitlanders in future, would render unnecessary any further intervention on their behalf ; but they could not, of course, debar themselves from their rights under the Convention, nor divest themselves of the ordinary obligations of a civilized power to protect its subjects in a foreign country from injustice. As to the suzerainty, the condition imposed could not be accepted, as her Majesty’s Government were of opinion that the contention of the South African Republic to be a sovereign international state was not warranted either by law or by history, and was entirely inadmissible. In reference to arbitration, Mr. Chamberlain agreed to the discussion of the form and scope of such a tribunal, and suggested an early conference.

The Transvaal replied that it regretted the refusal of her Majesty’s Government to accept the conditions annexed to the latest franchise proposals, which proposals it now withdrew. The Transvaal having refused the joint inquiry into the working of the seven years’ franchise law, nothing was left between the two parties but Sir Alfred Milner’s proposal put forth at Bloomfontein. However, Mr. Chamberlain made one more effort for a peaceful settlement. In a dispatch dated September 9, 1899, he stated that her Majesty’s Government was still willing to accept the Transvaal’s offer of a five years’ franchise, without the conditions attached ; that the acceptance of this offer would at once remove the tension between the two governments, and would in all probability render unnecessary any further intervention on the part of her Majesty’s Government to secure the redress of the Uitlander grievances ; further, that such questions as remained for settlement between the two governments — those which were neither Uitlander questions nor questions of interpretation of the Convention — might be referred to a tribunal of arbitration. If the answer, however, to this last proposal was negative or inconclusive, her Majesty’s Government would reserve the right to reconsider the situation de novo, and to formulate their own proposals for a final settlement.

It grows increasingly clear, from the perusal of these dispatches, that the core of the contention between England and the Transvaal is the relative status of the two governments. This status depends upon the fact and extent of British suzerainty under the two Conventions of 1881 and 1884. The Convention of 1881 consisted of a Preamble and a number of Articles. The Preamble grants self-government to the inhabitants of the Transvaal in these words : “ complete self-government, subject to the suzerainty of her Majesty, to the inhabitants of the Transvaal territory, upon certain terms and conditions, and subject to certain reservations and limitations.” Now I take this to mean that, on certain terms and conditions, —that is, the laying down of arms, and so on, — self-government was to be granted to the people of the Transvaal under the suzerainty of the Queen, but that this self-government was to be subject to certain reservations and limitations. In other words, the reservations and limitations did not refer to the suzerainty, but to the self-government. It was not to be unconditional self-government, but self - government with certain specified limitations in addition to the general limitation of the Queen’s suzerainty.

As there can be no question as to the assertion of the suzerainty in the Convention of 1881, there remains only one point to be dealt with, — whether the suzerainty persists in the Convention of 1884.

Any doubt as to the existence of the suzerainty would at once be removed by an examination of the circumstances under which the Convention of 1884 was signed. The Transvaal delegates requested the British Government to do away with the suzerainty by marking the proposed Convention a treaty between two powers. This the Government refused to do, on the ground that the Transvaal was not in fact an independent power, nor was it intended that it should be represented as such. So the issue was definitely raised before the Convention was signed, and the Transvaal delegates signed the Convention knowing the feelings of her Majesty’s Government on the matter.

The question really at issue between the Transvaal and Great Britain is that of supremacy in South Africa. The discussion of the Uitlander grievances was essentially a difficult matter ; for the Boers, going back to 1881, recalled the fact that there was a time when apparently England was prepared to break her most solemn promises, when the most positive assertions of her desires and intentions were swept away like chaff at the first sign of resistance ; and remembering this, they not unnaturally hoped that the same thing might happen again. But as to the larger issue there can be no uncertainty. The Transvaal government “ wish to confine themselves to stating the standpoint formerly taken up by them, which they hereby declare they maintain, namely, that no suzerainty exists ; ” 2 while the British Government say, “the contention that the South African Republic is a sovereign international state is not, in their opinion, war-

ranted either by law or history, and is wholly inadmissible.” 3

England’s action in South Africa has been construed as an attempt to deprive the Transvaal of those great benefits which belong to self-government, and to substitute an autocratic foreign rule for a government deriving its powers from the will of the people. This is very far from being the case. The origin of England’s interference in the affairs of the Transvaal lies in the fact that everything implied in the grant of self-government has been persistently withheld from the majority of the inhabitants of that country. England demands that the men who pay the taxes shall have a voice in the government ; that the courts of justice shall be independent of the executive power ; that the lives and property of the citizens shall be protected ; that a man shall be tried by a jury of his peers. There would appear to be little in these demands incompatible with the principle of self-government.

After this article had gone to the printer, news of the outbreak of hostilities arrived. It would be idle now to dilate on the possible effects of this unfortunate resort to arms. As England has sought nothing but fair treatment for the majority of the inhabitants of the Transvaal, and the recognition of British supremacy in South Africa, it is to be hoped that, at the conclusion of the war, the ill feeling between the Dutch and English in South Africa will gradually die out, under the influence of those advantages arising from a strong and just government. There is little reason to doubt that, under whatever name the South African Republic emerges from the conflict, the inhabitants of that country will be granted all the substantial rights of self-government.

Alleyne Ireland .

- As an example of the subordination of the judiciary to the executive, I may quote the case of a man named Dums, who sued the Government in respect of the yielding to England by treaty of his farm, The Government immediately passed a law to the effect that Dums could never sue the Government, for anything. ↩

- Dispatch from State Secretary of the Transvaal, dated May 9, 1899. ↩

- Dispatch from Mr. Chamberlain, dated July 13, 1899. ↩

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Moederland: Nine Daughters of South Africa review – my ancestors’ role in the horror of apartheid

Cato Pedder, great-granddaughter of South African PM and white supremacist Jan Smuts, uses her family’s legacy to unearth stories of women that shaped, and were shaped by, a troubled nation

O n 29 May this year, South Africans will go to the polls to vote in their seventh democratic general election. Thirty years ago, the country’s first free and fair election saw the formal end of apartheid when, as Cato Pedder writes, “all night, all that day, all the next day, 19.5 million people, 85% of the electorate, queue[d] peacefully outside polling stations across the country … And each of them, as they receive[d] their ballot paper … [felt] this ritual [was] somehow holy.” With Nelson Mandela as the president of the new South Africa , the country was full of hope, but the ensuing decades have been troubled by blatant government corruption, nepotism, water and electricity crises, vast unemployment and social unrest. This year a record 27.72 million citizens are registered to vote (19,525 of those in London), a jump of almost 1 million since 2019. This increase suggests people’s frustrations; their desire to question those in power. Many new voters are women, and women make up the majority of registered voters (55.24%). However, analyses after previous elections have shown that women are often kept from voting by domestic duties, which is likely to occur again in May.

It is women and their role in South Africa’s past that form the subject of Moederland and through which Pedder attempts to understand herself and where or how she belongs. She lives in England, yet her name and blood irrevocably connect her to South Africa and a culture “freighted with shame”. Named after her grandmother, she has spent her life explaining that Cato is not pronounced “Kate-o” but “Cuh-too. It’s Afrikaans, short for Catharina”. Her great-grandfather was Jan Smuts, twice prime minister of South Africa, a man so revered by the British that a statue of him still stands in Parliament Square. Smuts is the only person in the world to have signed the peace treaties after both world wars; he was central to the creation of the League of Nations, and drafted the preamble to the UN charter. He was also a white supremacist who supported racial segregation and was involved in writing and promulgating the laws that paved the way to apartheid. Pedder struggles with her “place in all this”, her great-grandfather tying her “to the white male power that continues to saturate South Africa and further afield”.

after newsletter promotion

It is no secret that women are often absent from history books, with historians blaming a lack of recorded information. But, as Pedder finds, the South African archives are full of the letters and journals of women, as well as opgaafrolle (tax censuses), the transcribing and analysing of which my own colleagues at Stellenbosch University are engaged in; revealing data about women, enslaved people and indigenous Khoikhoi people who were often forced into servitude. This data conveys details such as what they owned, where they lived, and family groupings. The information is there: it only has to be looked for.

Informed by impressively thorough research, Pedder follows nine of her female ancestors (family trees are included at the start of the book), from the 17th century when the Dutch first landed at the Cape, and moving through the centuries, via the “great trek” of settlers into the interior, the atrocities of the Boer war, and the shame and horror of apartheid. Exploring the past, bringing it to vivid life with wonderful prose, she intersects the lives of her ancestors with her own thoughts and experiences.

But this is not another whinging apologia by a white author. Pedder writes with perspicacity and sensitivityand is able to articulate her dismay at having laboured under “the misapprehension that in retelling the long-forgotten stories of women, [she would be] striking a righteous blow” not only for her own female ancestors but for women generally, such as her proto-Afrikaans forebear and seventh great-grandmother, Anna Siek, whose place in history books has been little more than “a footnote”. In reality, Pedder realises, writing about white women means writing about how they have participated in white domination. White and black women have had very different experiences, so while Pedder is horrified at her proximity in the family tree to a slave-owning torturer – Michiel Otto, second husband of Siek – she must also acknowledge the role his wife (and the wives of other white men) played in oppression. Or even someone like Isie, wife of Smuts, who was appalled by the thought of white women voting or having seats in parliament, let alone men of colour, or, heaven forbid, women of colour.

The first of the nine women in Moederland is a Khoikhoi girl whose real name we do not know, though she has become famous in South African history. The Dutch adopted her as a pet, a translator, a creature to civilise, and named her Eva (after the biblical first woman). Her Khoikhoi name is recorded by them as Krotoa, and so she has become known to us. Her role in the history of South Africa, her life caught between the Dutch and her own people, her eventual partial banishment to Robben Island with her white husband and mixed-race children, her alcoholism and death, have been revisited and imbued with various isms and significances in recent decades – she is part of colonialism, racism, post-colonialism, feminism, post-apartheid reparations, and historical rewriting and reclamation. Pedder is aware of the way Krotoa has been exploited over the centuries for various ends, and also that she represents a true connection to South Africa prior to the ill-effects of colonisation. Her own desire to find a connection with Krotoa does not sit comfortably with her, yet it is there, a wish to find some link that will legitimate her sense of belonging to South Africa. But what role can DNA really play, she asks. Does having a connection to Indigenous people remove you from guilt and responsibility? What percentage is enough to belong fully and wipe the slate clean? Her DNA results show that she is “European, but there are matches to another community, partial incomplete”. Yes, she is a colonialist, but she is also South African.

In fact, Moederland provides more questions than answers, but that is not a flaw. It is the questioning that makes this book valuable, just as it is questioning that must become part of all our lives on a path to understanding ourselves and others today when too often cancel culture wants to delete and deny. Research enables us to explore, and it fuels our ability to interrogate ourselves, our pasts, our presents and futures. We need more books like this, we need more detailed research, more people allowing themselves to be uncomfortable and to question.

Crooked Seeds by Karen Jennings (Holland House Books, £14.99). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply.

Moederland: Nine Daughters of South Africa by Cato Pedder is published by John Murray (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply

- History books

- Book of the day

- South Africa

Most viewed

- Subscriptions

- Commercial Rights

South Africa: The Great Trek 1836–46

The Great Trek is the name given to the exodus of 12,000–14,000 Boers from British Cape Colony. Frustrated by the colony’s Anglicization policies, restrictions on slave labour and population pressures intensified by drought and increasing inward migration, they chose to look for better grazing pastures elsewhere. After crossing the Orange River, the trekkers split, northwards or eastwards. After a series of skirmishes, the northern trekkers achieved decisive victory over the Ndebele at Mosega in 1837 and created the independent republics of Transvaal and Transorangia. The eastwards Boers defeated the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River and declared the republic of Natal. The British Government annexed Natal in 1843, but recognized the inland republics in 1852–54. However, they sought to restrain the Boer expansion by simultaneously granting recognition to two native protectorates in Griqua and Basuto. These territories harboured many Boer settlers, becoming a source of future contention.

Different Formats

Request Variations

Institution Subscriptions

MORE MAPS TO EXPLORE

Nubia in the 18th Dynasty c. 1550–1290 BCE

Trading with New Kingdom Egypt 1500–1330 BCE

Nubia After the New Kingdom from 1550 BCE

The Campaigns of Ramesses II c. 1276–1270 BCE

Macedonians in Egypt 332–240 BCE

Egypt in Syria 1425–1418 BCE

Administrative Nomes of Upper Egypt

Saite Expansion 664–656 BCE

- South Africa

- View all news

- Agribusiness

- Empowerment

- Managing for profit

- View all business

- Aquaculture

- Game & Wildlife

- Sheep & Goats

- View all animals

- Field Crops

- Fruit & Nuts

- View all crops

- How to Business

- How to Crop

- How to Livestock

- Farming for Tomorrow

- Machinery & Equipment

- Agritourism

- Hillbilly Homes

- Classifieds

Boer goat ram ‘Formula One’ sold for over R1 million

The boer goat stud sire formula one was recently sold for r1,05 million, the highest price ever paid in south africa for a stud goat..

Formula One was bred and sold by the Lukas Burger Stud from Griekwastad and bought by VEA Stud Breeders from Bonnievale.

This award-winning goat comes from a top bloodline. His dam Demi Lee and sire Maserati represent some of best bloodlines in the country.

Formula One is a proven stud sire and has been used by the Lukas Burger Stud from 2022. Between 2022 and 2024, the goat sired 300 kids.

READ Starting a Boer goat stud on a 10ha farm

William Smit, VEA Stud Breeders’ spokesperson, told Farmer’s Weekly : “Formula One is the ideal package as far a stud Boer goat sire is concerned. The first thing that we noticed about him was his immense size and incredible capacity. His length and width are outstanding, coupled with masculinity and a long line of proven genetics.”

According to Smit, the purchase of Formula One is a valuable investment in the long-term future of VEA Stud.

READ Boer goat buck sold for a record price on auction

One of his sons, for instance, took the laurels in his category at the 2024 Northern Cape Boer Goat championships while a Formula One daughter took the laurels in her category at the Vryburg regional show.

MORE FROM FARMER’S WEEKLY

Poor quality silage threatens animal health

Directive issued to promote welfare of animals in transit

NAMPO aims to connect farmers and visitors again

Pioneering carrot producer Vito Rugani mourned

Congress discusses improving mental health in veterinary industry

Maize theft in Free State raises serious concern

The dangers of using livestock medicines incorrectly

Twee Seuns Suffolk Stud Production Sale

Want to start a pig farm? Read this first!

Many KZN farmers receive permits to cultivate cannabis

Load-shedding adds to low producer beef prices

Local problems more of a threat to SA than losing AGOA

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Great Trek, the emigration of some 12,000 to 14,000 Boers from Cape Colony in South Africa between 1835 and the early 1840s, in rebellion against the policies of the British government and in search of fresh pasturelands. The Great Trek is regarded by Afrikaners as a central event of their 19th-century history and the origin of their nationhood. It enabled them to outflank the Xhosa peoples ...

The Great Trek (Afrikaans: Die Groot Trek [di ˌχruət ˈtrɛk]; Dutch: De Grote Trek [də ˌɣroːtə ˈtrɛk]) was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial administration. The Great Trek resulted from the culmination of ...

Boers (/ b ʊər z / BOORZ; Afrikaans: Boere are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled Dutch Cape Colony, but the United Kingdom incorporated it into the British Empire in 1806. The name of the group is derived from ...

Great Trek 1835-1846. The Great Trek was a movement of Dutch-speaking colonists up into the interior of southern Africa in search of land where they could establish their own homeland, independent of British rule. The determination and courage of these pioneers has become the single most important element in the folk memory of Afrikaner ...

Boer, (Dutch: "husbandman," or "farmer"), a South African of Dutch, German, or Huguenot descent, especially one of the early settlers of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Today, descendants of the Boers are commonly referred to as Afrikaners. ... Between 1835 and 1843 about 12,000 Boers left the Cape in the Great Trek, heading ...

Boer republics and Griqua states in Southern Africa, 19th century. The Boer republics (sometimes also referred to as Boer states) were independent, self-governing republics formed (especially in the last half of the 19th century) by Dutch-speaking inhabitants of the Cape Colony and their descendants. The founders - variously named Trekboers, Boers, and Voortrekkers - settled mainly in the ...

Voortrekker, any of the Boers (Dutch settlers or their descendants), or, as they came to be called in the 20th century, Afrikaners, who left the British Cape Colony in Southern Africa after 1834 and migrated into the interior Highveld north of the Orange River.During the next 20 years, they founded new communities in the Southern African interior that evolved into the colony of Natal and the ...

The Great Trek was a perilous exodus of pioneers into the heart of South Africa, looking for a place to call home. When the British took control of Cape Town and the Cape Colony in the early 1800s, tensions grew between the new colonizers of British stock, and the old colonizers, the Boers, descendants of the original Dutch settlers. From 1835 ...

This migration of more than 10,000 Boers became known as the Great Trek. The Boers eventually moved beyond the Orange and Vaal rivers and established the Orange Free State and the South African Republic. The British recognised the independence of the South African Republic in 1852 and the Orange Free State in 1854.

Great Trek. Afrikaners left the Cape Colony (in present-day South Africa) in large numbers during the second half of the 1830s, an act that became known as the "Great Trek" and that helped define white South Africans' ethnic, cultural, and political identity.In line with Afrikaners' belief in a separate existence, developing tensions between these settlers, British authorities, and African ...

Many Afrikaaners today refer to them as the Anglo-Boer Wars to denote the official warring parties. The first Boer War of 1880-1881 has also been named the Transvaal Rebellion, as the Boers of the ...

Great Trek Centenary Celebrations commence. 8 August 1938. The Great Trek was a migration that took place between 1838 and the 1840s, and involved the Boers leaving the Cape Colony and settling in the interior of South Africa. White settlement led to the establishment of the republics of Natalia, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal.

The mass migration of the Boer farmers from Cape Colony to escape British domination in 1835-36 - the Great Trek - has always been a potent icon of Africaaner nationalism and identity. For African nationalists, the Mfecane - the vast movement of the Black populations in the interior following the emergence of a new Zulu kingdom as a major military force in the early 19th century - offers an ...

A heresy that bears a charmed life teaches that the Great South African Trek was brought about by the abolition of slavery in 1833. The contention is that fury at the British government's interference in the Boer way of life by this attack on their cherished system of slave labour, resentment at the financial losses incurred through ...

The mass migration of the Boer farmers from Cape Colony to escape British domination in 1835-36 - the Great Trek - has always been a potent icon of Afrikaaner nationalism and identity. For African nationalists, the Mfecane - the vast movement of the Black populations in the interior following the emergence of a new Zulu kingdom as a major military force in the early 19th century - offers an ...

The history of the great Boer trek and the origin of the South African republics by Cloete, Henry, 1790-1870; Cloete, William Brodrick, 1851-1915, ed. Publication date 1899 Topics Afrikaners Publisher London, J. Murray Collection americana Book from the collections of University of Michigan

Piet Retief (born Nov. 12, 1780, near Wellington, Cape Colony [now in South Africa]—died Feb. 6, 1838, Natal [now in South Africa]) was one of the Boer leaders of the Great Trek, the invasion of African lands in the interior of Southern Africa by Boers seeking to free themselves from British rule in the Cape Colony.. Although he was better educated than most Boers, his combining of farming ...

The History of the Great Boer Trek and the Origin of the South African Republics. This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the ...

The Great Trek was the emigration of the Cape of Good Hope colonists in the 1830's. This followed previous isolated treks of Dutch colonists who moved inland almost from the beginning of European Settlement in South Africa.. There were a number of reasons that caused the colonists who were mainly of Dutch origin to leave their homes and settle themselves inland and away from British rule.