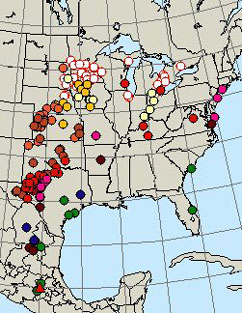

The North American network of monarch butterfly monitoring programs

Journey north.

Journey North engages students and citizen scientists around the globe in tracking wildlife migration and seasonal change. Participants share field observations across the northern hemisphere, exploring the interrelated aspects of seasonal change. In addition to monarchs, Journey North tracks the migration of several other species, including hummingbirds, robins, gray whales, whooping cranes, bald eagles, and tulips.

Publications

Monarch-centric Monitoring Programs

Programs monitoring all species.

The North American Butterfly Monitoring Network

working together to advance knowledge on butterflies

Journey North

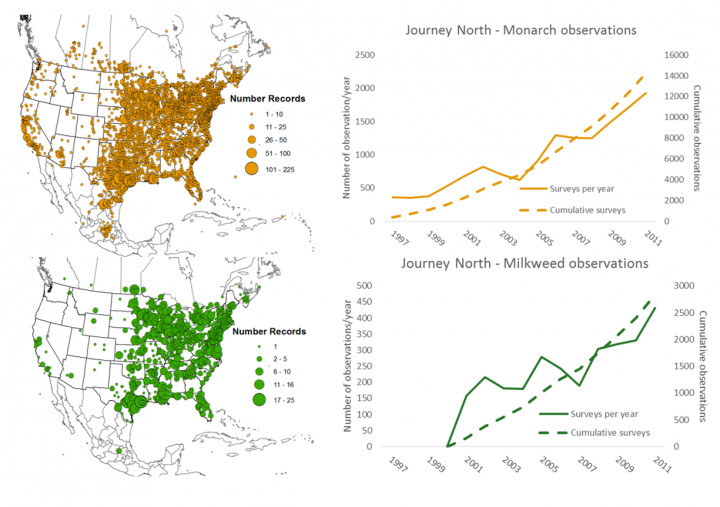

Journey North is a contributory, crowdsourced citizen science program of the University of Wisconsin-Arboretum. Journey North’s mission is to engage a wide audience across North America in tracking migration and seasonal change to foster scientific understanding, environmental awareness and the land ethic. Journey North Monarchs & Milkweed Project invites participants from Canada, US and Mexico to submit observations on phenological events including migration and life cycle stages of project species. During the spring season, participants submit data on first arrival of monarchs; first emergence of milkweed, first sightings of monarch eggs and larva. In the summer, participants record the presence of adult monarchs, milkweed and breeding activity. In the fall, participants track peak migration and roost locations. Finally, during the winter months, participants are encouraged to submit presence of monarchs found beyond official sanctuary locations. In addition to the Monarchs & Milkweed Project, Journey North observers also help track the migration of Hummingbirds, Common Loons & Ice-Out, American Robins, Barn Swallows, Red-winged Blackbirds, and Baltimore and Bullock’s Orioles. Journey North also runs two educational projects: Tulip Test Garden and Symbolic Migration.

The Symbolic Migration project is a partnership project between Journey North, a program of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum, and Monarchs Across Georgia, a committee of The Environmental Education Alliance of Georgia, a 501(c)(3) organization. Journey North manages the interactive Symbolic Migration Participant Maps and hosts all educational materials on the Journey North website. Monarchs Across Georgia administers the program and is responsible for all fundraising.

Monitoring Activity Tracker

Program Results

Flockhart DTT, Pichancourt JB, Norris DR, Martin TG. 2015. Unravelling the annual cycle in a migratory animal: breeding-season habitat loss drives population declines of monarch butterflies. Journal of Animal Ecology 84: 155-165.

Howard E, Davis AK. 2015. Tracking the fall migration of eastern monarchs with Journey North roost sightings: new findings about the pace of fall migration in Oberhauser KS, Nail KR, Altizer SM, eds. Monarchs in a Changing World: Biology and Conservation of an Iconic Insect. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University Press.

Batalden RV, Oberhauser KS. 2015. Potential changes in Eastern North American monarch migration in response to an introduced milkweed, Asclepias curassavica in Oberhauser KS, Nail KR, Altizer SM, eds. Monarchs in a Changing World: Biology and Conservation of an Iconic Insect. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University Press.

Nail KR, Batalden RV, Oberhauser KS. 2015. What's too hot and what's too cold? Lethal and sub-lethal effects of extreme temperatures on developing monarchs in Oberhauser KS, Nail KR, Altizer SM, eds. Monarchs in a Changing World: Biology and Conservation of an Iconic Insect. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University Press.

Flockhart DTT, Wassenaar LI, Martin TG, Hobson KA, Wunder MB, Norris DR. 2013. Tracking multi-generational colonization of the breeding grounds by monarch butterflies in eastern North America. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 280: 8.

Howard E, Davis AK. 2012. Mortality of migrating monarch butterflies from a wind storm on the shore of Lake Michigan, USA. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 45: 49-54.

Davis AK, Nibbelink NP, Howard E. 2012. Identifying large-and small-scale habitat characteristics of monarch butterfly migratory roost sites with citizen science observations. International Journal of Zoology 2012.

Howard E, Davis AK. 2011. A simple numerical index for assessing the spring migration of monarch butterflies using data from Journey North, a citizen-science program. Journal of the Lepidopterists Society 65: 267-270.

Howard E, Aschen H, Davis AK. 2010. Citizen Science Observations of Monarch Butterfly Overwintering in the Southern United States. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology Vol. 2010, Article ID 689301, 6 pages.

Howard E, Davis AK. 2009. The fall migration flyways of monarch butterflies in eastern North America revealed by citizen scientists. Journal of Insect Conservation 13: 279-286.

Davis AK, Howard E. 2005. Spring recolonization rate of monarch butterflies in eastern North America: new estimates from citizen-science data. Journal of the Lepidopterists Society 59: 1.

Feddema JJ, Shields J, Taylor OR, Bennett D. 2004. Simulating the Development and Migration of the Monarch Butterfly. Pages 229-240 in Oberhauser KS, Solensky MJ, eds. The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Howard E, Davis AK. 2004. Documenting the Spring Movements of Monarch Butterflies with Journey North, a Citizen Science Program. Pages 105-116 in Oberhauser KS, Solensky MJ, eds. The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Monitor Tracker

Art shapiro's butterfly project, butterflies and moths of north america, cape may monarch monitoring project, carolina butterfly society, carolinas butterfly monitoring program, cascade-siskiyou butterfly monitoring network (oregon/california), cascades butterfly project, chincoteague monarch program, coastal virginia wildlife observatory, colorado butterfly monitoring network, florida butterfly monitoring network, hawk migration association of north america (hmana), illinois butterfly monitoring network, iowa butterfly survey network, long point fall migration monitoring, maine butterfly survey, maritimes butterfly atlas, massachusetts butterfly club, michigan butterfly network, missouri butterfly monitoring network, monarch health, monarch joint venture, monarch larva monitoring project, monarch monitoring project (wwf-mexico), monarch watch, mpg ranch (montana), nevada butterfly monitoring network, new mexico butterfly monitoring network, north american butterfly association, occoquan region monitoring project, ohio lepidopterists monitoring network, ontario butterfly atlas, orange county butterfly network (california), peninsula point monitoring project, pieris project, prissm - partnership of regional institutions for sage scrub monitoring (california), rare charitable research reserve (ontario), rice creek field station, suny oswego (new york), southwest monarch study, swengel & swengel surveys, tennessee butterfly monitoring network, texas butterfly monitoring network, vanessa migration project, vermont butterfly survey, western monarch counts, wisconsin butterfly monitoring program.

© 1997 – 2019 Journey North. All rights reserved.

- Help Save The Monarchs

Experience the Amazing Monarch Butterfly!

We hope you enjoy this interactive map which shows the amazing migrations of monarch butterflies. You can see where they fly, the urgent threats they are facing, and how your support is expanding innovative solutions to help monarchs and other butterflies survive. Please start your journey now, then provide your support to help save monarchs and other wildlife!

You help butterflies wherever they fly

Did you know eastern monarch butterflies will fly between 2,000 to 3,000 miles to an overwintering location in South-Central Mexico? From New England to California, thanks for helping protect the pollinators that help keep our natural world healthy.

You help young people flap their wings

In Michigan, you help more than 3,000 students learn about monarchs, and what they can do to help care for the planet.

You’re expanding conservation in three countries

You’ve helped more than 1,500 communities in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada take the Monarch Mayors pledge to help pollinators thrive!

You’re taking ACTION for monarchs

You help push Congress to pass the MONARCH Act, which invests in the conservation and recovery of the western migratory monarch and other native pollinators.

You help increase monarch POPULATIONS

In California, the western monarch population decreased again this year. We must act now to protect them, and we can do more with your continued support!

You’re supporting a migration corridor

Interstate 35 goes from Texas to Minnesota and follows the migration flyway for monarchs. Your support helps protect monarch habitat and plant the milkweed they need.

You help non-migratory monarchs, too

Not all monarchs migrate. Florida has a large non-migratory monarch population. Your support helps protect their habitat and food sources.

A Monarch’s Journey

Monarchs can fly over 100 miles in a single day given the right conditions; one monarch traveled 265 miles in just one day. It can take migratory monarchs up to two months to complete their journey.

You’re creating something to celebrate

Every year, Mexicans celebrate their ancestors on the Day of the Dead. Around that time, the monarchs arrive! Thanks for helping Mexico, Canada, and the U.S. expand conservation.

The Migration Generation

Around four generations of monarchs will emerge throughout the year. The first few generations are tasked with migrating north and laying lots of eggs, while the fourth generation must trek south to Mexico and overwinter.

Monarch Butterfly overview

We’ve prepared a special video to show you monarch butterflies and help you learn more about the urgent threats they’re facing. Watch it now!

Help Save Monarchs with Your Gift Today

This interactive map shows your impact. But will it be enough? The annual numbers for the eastern migratory monarch population have just been released and they clearly show that monarchs are struggling now more than ever. Extreme weather events are a primary cause of the more than 50% drop in the population in the past year. We must act now. Later is too late! Please support the National Wildlife Federation with your gift today. Thank you!

Count Me In!

I’ll help save the butterflies and other wildlife with a contribution today.

- Privacy Policy

- Keep The Conversation Going

National Wildlife Federation PO Box 1583, Merrifield, VA 22116-1583

- Mission & Vision

- Habitat Conservation

- Scientific Research and Monitoring

- Sustainable Development

- Education and Outreach

- News and Updates

- Publications

- Grants & Awards Overview

- Award Recipients

- Small Grants Program

- Project Challenges

- Population Status

- Annual Cycle

- Ways to Give

- MBF Champions

- Leaving a Legacy

- Things You Can Do

- The Monarch Butterfly Fund Story

- Where Funds Go

- Board, Advisors & Staff

- Join Our Board

- MBF Newsletters

- Newsletter Subscription

Support for Journey North

MBF supporting Journey North in its program to track the monarch migration.

July 16, 2023

MBF has supported Journey North to continue with their amazing work tracking the monarch migration. People can report their sightings and view maps of the migration . During the fall, Estela Romero provides information on the overwintering sites and also delivers paper butterflies to children in the schools around the monarch area as part of the symbolic migration . Additionally she gives environmental education lessons through the " Beyond the Mexico " project that MBF also supports.

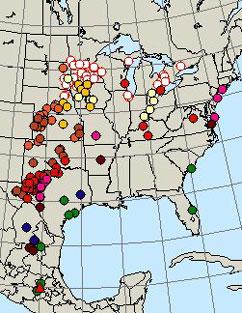

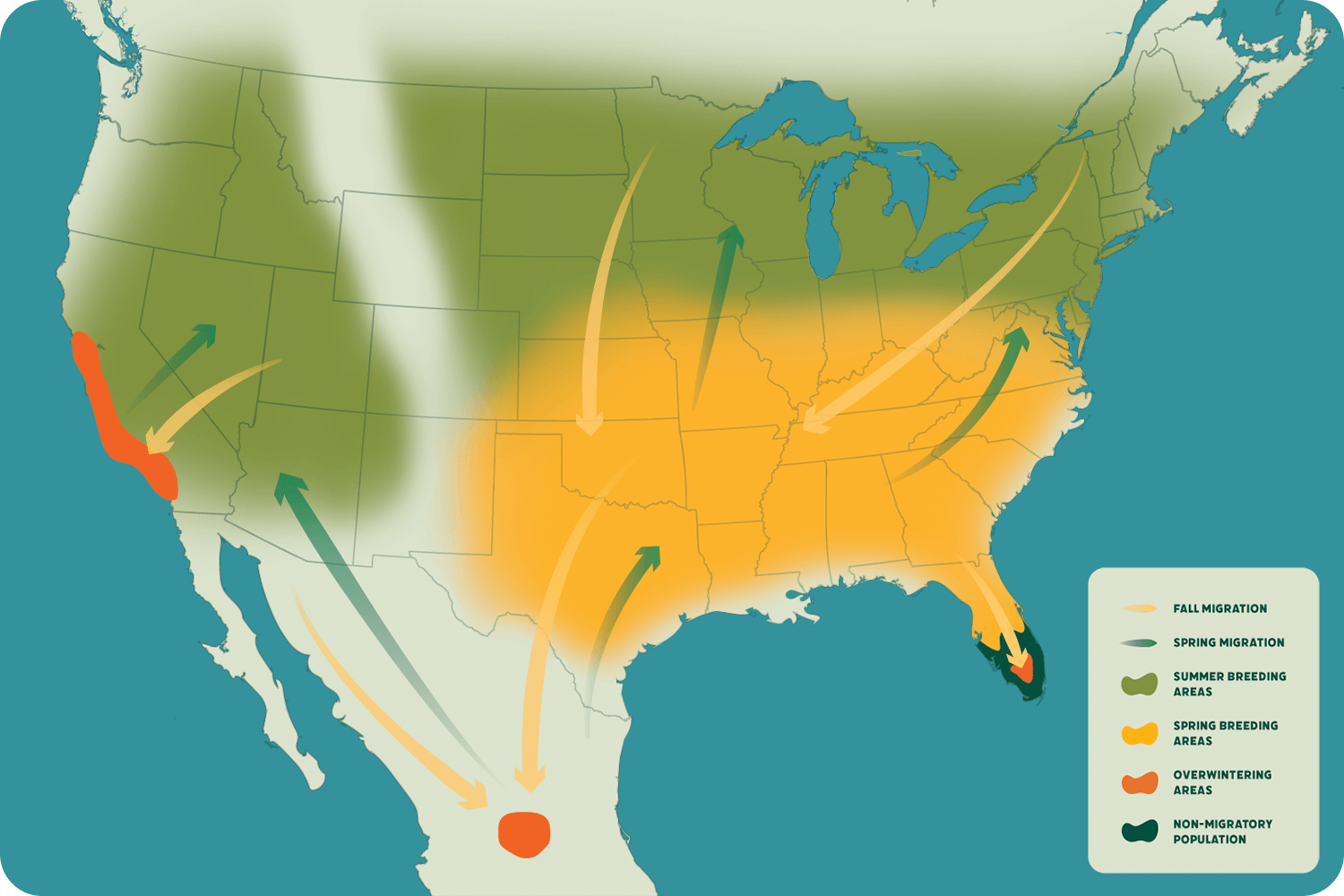

Partnering to conserve the monarch butterfly migration

Each fall, North American monarchs travel from their summer breeding grounds to overwintering locations. East of the Rocky Mountains, monarchs travel up to an astonishing 3,000 miles to central Mexico, whereas the shorter migration west of the Rockies is to the California coast. There is evidence of some interchange between the eastern and western populations, perhaps when individuals cross the Rocky Mountains, when butterflies fly from the western U.S. to the Mexican wintering sites, or butterflies from the Mexican sites fly into the western U.S.

On This Page

Tracking the monarch migration through community science, correo real.

Correo Real is a monarch education project which tracks the monarch migration through northern Mexico. The project was created by Señora Rocio Treviño so that volunteers throughout northern Mexico could submit counts and observations of the fall monarch migration.

Journey North

Journey North engages citizen scientists from across North America in tracking migration and seasonal change to foster scientific understanding, environmental awareness, and the land ethic. Volunteers submit observations of the first monarchs in the spring, roosts in the fall as well as first emergence and presence of milkweed. Sign up for weekly news updates and watch real-time interactive maps.

Monarch Monitoring Project

The Monarch Monitoring Project, or Cape May Monitoring Project, focuses on the fall migration of monarchs along the Atlantic coast, specifically through Cape May, an important migratory stopover for east coast monarchs. Volunteers record monarchs moving through West Cape May and Cape May Point, New Jersey.

Monarch Watch Tagging

To determine monarch migration routes, and weather influence and survival during monarch migrations, Monarch Watch launched a tagging program to mark individual monarchs with a unique identification. The tagging program has produced a dataset with records of over one million tagged butterflies and more than 16,000 recoveries.

Peninsula Point Monitoring Project

Peninsula Point Monitoring Project is an effort managed by the U.S. Forest Service to monitor monarch larvae and conduct migration counts at an important stopover site on the northern shore of Lake Michigan, Peninsula Point.

Southwest Monarch Study

Understanding migratory and breeding patterns in Arizona and the desert Southwest is very important since monarchs there fall between the eastern and western migratory populations. The Southwest Monarch Study tracks the migration and breeding patterns of monarchs in this region.

Project Monarch

Project Monarch uses the world’s smallest tracking devices to track Monarch migration. Download the app on your Bluetooth-enabled iOS or Android device and scan for tagged monarchs. View maps of tagged monarch observations on the app or website.

Interactive Monarch Migration

Click on the seasons on the right for an interactive view of the monarchs' annual migration. When each animation is finished, click on the butterfly to learn more with videos and slide shows.

Go to full screen version

This map was created in collaboration with the Center for Global Environmental Education at Hamline University with generous support from U.S. Forest Service - International Programs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Missouri Department of Conservation.

Eastern Monarchs

Decreasing day length and temperatures, along with aging milkweed and fewer nectar sources trigger a change in monarchs; this change signifies the beginning of the migratory generation. Unlike summer generations that live for two to six weeks as adults, adults in the migratory generation can live for up to nine months. Most monarch butterflies that emerge after about mid August in the eastern U.S. enter reproductive diapause (do not reproduce) and begin to migrate south in search of the overwintering grounds where they have never been before. From across the eastern U.S. and southern Canada, monarchs funnel toward Mexico. Along the way, they find refuge in stopover sites with abundant nectar sources and shelter from harsh weather. Upon reaching their destination in central Mexico beginning in early November, monarchs aggregate in oyamel fir trees on south-southwest facing mountain slopes. These locations provide cool temperatures, water, and adequate shelter to protect them from predators and allow them to conserve enough energy to survive winter. In March, this generation begins the journey north into Texas and southern states, laying eggs and nectaring as they migrate and breed. The first generation offspring from the overwintering population continue the journey from the southern U.S. to recolonize the eastern breeding grounds, migrating north through the central latitudes in approximately late April through May. Second and third generations populate the breeding grounds throughout the summer. It is generally the fourth generation that begins where we started this paragraph, migrating through the central and southern U.S. and northern Mexico to the wintering sites in central Mexico.

Western Monarchs

In any given year, adult monarchs west of the Rocky Mountains leave overwintering sites along the California coast (with a small number of sites in Baja California and Arizona) in February and March and head inland in search of milkweed on which to deposit their eggs. Once first-generation monarch eggs reach adulthood, they disperse east across the Central Valley and north across most of the western states. Second- and third-generation monarchs live and die throughout spring and summer, generally staying in the same areas where they hatched. The fourth generation (along with late bloomers from the third generation) emerges in late summer to fall. This migratory generation lives 6-9 months, compared to the 2-5 weeks of earlier generations. Western migratory monarchs also differ biologically from non-migratory generations; they are in a state of reproductive diapause, meaning their reproductive organs do not mature until later in the adult stage (after winter). Instead of looking for milkweed, fourth-generation western monarchs require nectar to build lipid reserves as they migrate south and west to the overwintering sites along the California coast (also in Baja California and Arizona), arriving around late October. Once they arrive, they roost for the winter in eucalyptus, Monterey cypress, Monterey pine, and other trees, sometimes in aggregations of thousands of individuals. In February and March, reproductive diapause ends and the annual cycle starts anew. Milkweed and nectar plant availability throughout the spring, summer, and fall will benefit western monarchs. In areas of the desert southwest, monarchs use nectar and milkweed plants throughout much of the year. For western monarch information and resources, visit the Western Monarchs category of our Downloads and Links page .

How do monarchs find the overwintering sites?

Orientation is not well understood in insects. In monarchs, orientation is especially mysterious. How do millions of monarchs start their southbound journey from all over eastern and central North America and end up in a very small area in the mountains of central Mexico? How do western monarchs find the same overwintering groves year after year? We know that they do not learn the route from their parents since only about every fourth to fifth generation of North American monarch migrates. Therefore, it is certain that monarchs rely on their instincts rather than learning to find overwintering sites. What kind of instincts might they rely on? Other animals use celestial cues (the sun, moon, or stars), the earth’s magnetic field, landmarks (mountain ranges or bodies of water), polarized light, infra-red energy perception, or some combination of these cues. Of these, the first two are considered to be the most likely cues that monarchs use, and consequently have been studied the most.

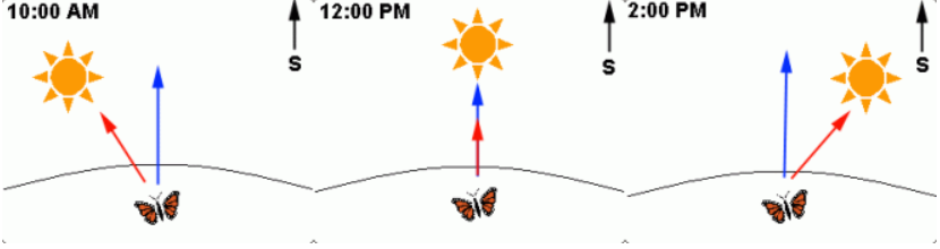

Sun Compass : Since monarchs migrate during the day, the sun is the celestial cue most likely to be useful in pointing the way to the overwintering sites. This proposed mechanism is called a sun compass. Monarchs may use the angle of the sun along the horizon in combination with an internal body clock (like a circadian rhythm) to maintain a southwesterly flight path. The way this would work is illustrated below. For example, if a monarch’s internal clock reads 10:00 AM, then the monarch will fly to the west of the sun to maintain a southern flight direction. When the monarch’s internal clock reads noon (12:00 PM), the monarch’s instincts tell it to fly straight toward the sun, while later in the day the monarch’s instincts tell it to fly to the east of the sun.

However, this would have to be combined with the use of some other kind of cue. If all the monarchs in eastern and central North America maintained a southwesterly flight, they could never all end up in the same place. It has been proposed that mountain ranges are important landmarks used by monarchs during their migration. For example, when eastern monarchs encounter a mountain range, their instincts might tell them to turn south and follow the mountain range. This kind of instinct would serve to funnel monarchs from the entire eastern half of North America to a fairly small region in the mountains of central Mexico.

Magnetic Compass: Scientists have suggested that monarchs may use a magnetic compass to orient, possibly in addition to a sun compass or as a “back-up” orientation guide on cloudy days when they cannot see the sun. Studies of migratory birds have indicated that they register the angle made by the earth’s magnetic field and the surface of the earth. These angles point south in the Northern Hemisphere and north in the Southern Hemisphere.

James Kanz (1977) conducted experiments to test the orientation of migratory monarchs held in cylindrical flight chambers. He reported that the monarchs flew in southwesterly directions on sunny days, but flew in random directions on cloudy days. He concluded that monarchs primarily use the sun to orient, and that magnetic orientation was unlikely, since the monarchs did not appear to be able to orient when they could not use the sun. However, Klaus Scmidt-Koenig (1985) reported conflicting evidence. He recorded the vanishing bearings (the direction in which a monarch disappears from sight) of wild, migratory monarchs, and found that even on cloudy days, most monarchs still flew in a southwesterly direction. Scientists attempted additional tests of magnetic orientation, but were not able to determine whether monarchs use the Earth’s magnetic field to orient.

However, researchers from the Reppert Lab (2014) showed that migratory monarchs indeed possess a magnetic compass that aids in orienting migrants south towards their overwintering grounds during fall migration. Remarkably, the use of the magnetic compass requires short wave UV-light (previous magnetic compass experiments failed to account for light at this range). With UV-light being allowed to enter the flight simulator, eastern migratory monarchs consistently oriented themselves south. The light-sensitive magnetosensors reside in the adult monarch’s antennae. While the expert consensus remains that the sun compass is the monarch’s primary compass for navigation, the authors suggest migratory monarchs use the magnetic compass to augment their sun compass.

Genetics : Upon dispersal, the Central and South American, Atlantic, and Pacific populations lost the ability to migrate. This prompted researchers to identify the gene regions in North American monarchs that appeared highly differentiated from non-migratory populations. Kronforst et al. (2014) identified 536 genes significantly associated with migration. One single genomic segment appeared to be divergent in the non-migrating populations and was extremely different from the North American population. One gene, collagen IV alpha-1, showed high divergence between migrating and non-migrating populations. Collagen IV alpha-1 is an important gene for muscle function, and divergence of this gene implicates selection for different flight muscles between migrating and non-migrating populations. Surprisingly, Collagen IV alpha-1 was down regulated in migratory monarchs, perhaps preparing them for lengthy flight. Furthermore, migrating monarchs had low metabolic rates compared to non-migrants as a consequence of flight muscle performance, lowering energy expenditure in migrating monarchs muscles. This evidence led researchers to conclude that changes in muscle function afforded migrating monarchs the ability to fly farther and use their energy more efficiently. Dr. Kronforst used the analogy of a marathon runner vs. a sprinter, "Migrating butterflies are essentially endurance athletes, while others are sprinters."

Overwintering Biology

Where do the monarchs go.

It is thought that monarchs were originally tropical butterflies that underwent range expansion. Scientists are not sure how long the monarch’s spectacular annual migration to Mexico has been occurring; it may be as old as 10,000 years (when the glaciers last retreated from North America) or as young as a few centuries. The earliest reports of overwintering clusters of monarchs in the United States were from California in the 1860s.

Monarch overwintering sites in Mexico and along the California coast have particular characteristics that enable monarch survival. These characteristics are important because they provide the monarch with the right overwintering conditions. Trees on which to cluster are one of the most important elements of the sites. The climate and the entire surrounding area are also important. Nearby trees, streams, underbrush, and fog or clouds all form an intricate natural ecosystem comprising the monarchs’ winter habitat. Monarchs need a cool place to roost so that they don’t use up their energy reserves as quickly. They also need to be protected from snow and winds. The surrounding trees serve as a buffer to the winds and snow.

Although monarchs are found in many areas of the world, the most spectacular migration occurs in North America.

Monarchs that spend the summer breeding season in eastern North America (including states and provinces east of the Rocky Mountains: central and eastern Canada, midwestern and eastern United States) migrate to the Transvolcanic mountains of central Mexico. Many millions of monarchs from these regions fly south to Mexico each fall. Their flight pattern is shaped like a cone as they come together and pass over the state of Texas on their way south. In massive butterfly clouds, they sweep up into the mountain ranges of central Mexico. Indigenous Mexican cultures of the Transvolcanic Range have welcomed the monarch migration since time immemorial; in 1975 scientists from Canada and the U.S. recorded the overwintering sites for the first time.

In Mexico, monarchs roost in oyamel fir forests, which occur in a very small mountainous area in central Mexico. Overwintering sites are about 3000 meters (almost 2 miles) above sea level and are on steep, southwest-facing slopes. Because monarchs need water for moisture, the fog and clouds in this mountainous region provide another important element for the winter survival of the monarchs. The butterflies choose spots that are close to, but not quite, freezing. They cluster together, covering whole tree trunks and branches, and cling to fir and pine needles. The tall trees make a thick canopy over their heads. Protective trees and bushes soften the wind and shield the butterflies from the occasional snow, rain, or hail. Each of the above elements is important to the butterflies, making up the monarch habitat – trees in which to roost, other trees and shrubs to protect them, the cool air, and the presence of water.

Monarchs do not reproduce until the spring, so they do not rely on milkweed during this time. They do seek out water and drink nectar from flowers in the overwintering sites. These two documents list nectar plants identified within the overwintering reserves in Mexico (documents are in Spanish): PLANTAS de la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca , PLANTAS .

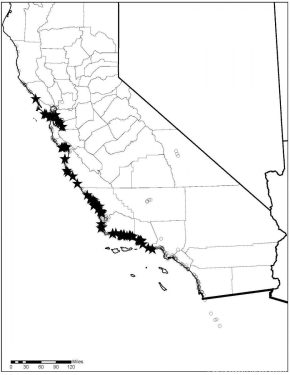

Monarchs that spend the summer breeding season in western North America (including states west of the Rocky Mountains: Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, and Montana) migrate to specific overwintering groves along the California coast roughly between Mendocino County in the north, and San Diego County in the South. Here, monarchs roost in eucalyptus trees, Monterey pines, and Monterey cypresses that are located in bays sheltered from wind, or farther inland where they're protected from storms. There are over 400 historic overwintering aggregations in California in addition to many temporary clusters. Scientists estimate that the California monarchs make up about 5% of the overall worldwide monarch population. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation has mapped out where to see congregations of overwintering monarchs in California here .

Journey North – Tracking Migrations and Seasons

PHOTO: SPRING 2019, TEXAS | “Lone female flew in, immediately laying eggs (50) on all available milkweed,” reported Julie Streit-Murphy of Vernon, Texas on March 23, 2019. Read the article .

Give people a profile-style introduction to Journey North and how it tracks the migrations of Monarchs throughout the year (not just 2017!). Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, et volutpat hendrerit intellegat has, ad quot doctus omittam per. Vis ne bonorum civibus, quas impetus scriptorem ex sed, quod tacimates nec ne. Pri ex oblique incorrupte scriptorem, movet convenire sit ex, hendrerit rationibus ex mei. Cu has vivendo theophrastus. Prompta nusquam et ius, agam adolescens vim ei. Vim reque affert cetero in, ullum deserunt repudiare eos ad, per ea ignota voluptaria. Saperet accusamus mediocritatem qui ad. Duo apeirian theophrastus ex. Te mea amet dolores.

Related Posts

Papalotzin – The flight of the Monarch Butterfly

Following the Monarchs in an Ultralight Airplane

Dreamy Visit to Mexico’s Monarch Butterfly Roosts

Premium Content

Follow the monarch on its dangerous 3,000-mile journey across the continent

The iconic North American butterfly's annual migration patterns are under threat from habitat loss and extreme weather, causing its devoted fans to research solutions and push for protection from the Endangered Species Act.

On a hot, clear October day in Texas hill country, André Green II is gently shaving a monarch butterfly.

Bent over his makeshift laboratory bench, he deftly pinches the butterfly’s bright wings between a thumb and forefinger, swiping a sliver of sandpaper down its thorax to remove a few minuscule hairs.

Green and his fellow researchers have set up temporary quarters inside one of the area’s many private hunting lodges, and its walls are lined with the taxidermied heads of native and exotic game animals. But Green, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Michigan and a National Geographic Explorer, has eyes only for the three dozen monarchs he captured earlier in the day. He applies a dot of epoxy between the wings of the butterfly in his hand, then affixes a custom-designed sensor—a stack of computer chips powered by a miniature solar panel that together weigh less than three grains of rice. The soft flutter of wings is the only sound in the room.

This monarch and its companions, Green and his collaborators expect, will carry the sensors to the mountains of central Mexico, 800 miles south. In a few weeks, the researchers will follow the monarchs to Mexico, where they will try to detect the signals emitted by the sensors’ antennas. If they can recapture one or more of the butterflies—a big if—they will be able to access the light and temperature data collected by the sensors en route, allowing them to map each butterfly’s path.

Like other monarch research projects across North America, this one has been aided by volunteers eager to help the species. Green’s colleagues, realizing that bicyclists travel at about the same speed as monarchs on the move, recruited cyclists to test the accuracy of the sensors by carrying them on multiday rides. Green conducted laboratory experiments to confirm that the sensors don’t interfere with flight. Now, this novel technology is about to undergo its first real-world test.

When he finishes attaching the sensors, Green sits back in an overstuffed leather chair, surveying the butterflies in the net cage before him. “This year, we’ll be happy if we pick up any kind of signal in Mexico,” he says. Collecting meaningful data might require several more seasons of trial and error, but Green is patient. Smiling, he resorts to scientific understatement: “It’s a real opportunity to understand this particular system.”

As the day cools, Green carries the cage of butterflies outside, picking his way downhill to the pecan grove below the lodge. There, beside a creek, hundreds of migrating monarchs swirl through the lengthening light. Green extracts the sensor-carrying butterflies one by one, gingerly settling them on low-hanging branches like so many glass ornaments. Tomorrow morning, if all goes well, they will continue to venture south, taking their secrets with them.

The system that so fascinates Green is one of the most epic, and dangerous, journeys on the planet. Though monarchs live throughout the world—in South America, the Caribbean, Australia, Europe, and elsewhere—North American monarchs are distinguished by their extraordinarily ambitious seasonal migrations. Each fall, monarchs in the northern United States and southern Canada fly south, the first relay team along a 3,000-mile route known only to earlier generations. Those that survive gather in central Mexico, where they spend the winter in the same fir groves that sheltered their grandparents and great-grandparents the previous year.

Despite decades of study, this annual ultramarathon—and the shorter migration of the continent’s western population along the Pacific Coast—is only partly understood and ever more perilous. Due to climate change and habitat loss, monarchs on both migration routes are increasingly beset by extreme weather and scarce nectar sources. At the same time, the milkweed plants that breeding monarchs need to host their eggs and feed their caterpillars remain in critically short supply, diminishing overall numbers.

The prospects for North American monarchs are considered so dire that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified the two populations as vulnerable. They’re now under consideration for protection by the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Those who have witnessed the populations’ decline hope their new status will lead to sustained, multinational action: Karen Oberhauser, who has studied monarchs since the 1990s and recently retired as director of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum, says that since the monarch was first proposed for protection under U.S. law in 2014, the species has gained new support from government agencies and scientists. “The level of federal engagement has just skyrocketed, and that’s been so important,” she notes. “It’s brought a lot of really smart people into our circles.”

While the monarch is neither the largest nor the showiest butterfly in North America, no other insect—and very few species of any kind—so captivates us. Its travels connect people across generations, national borders, and even, it is said, the barrier between life and death. Some Mexican observers of the annual Day of the Dead regard migrating monarchs as souls on the wing. Emergency workers in lower Manhattan during the days after September 11, 2001, saw the monarchs that sailed over ground zero as symbols of survival and rebirth. “When we say that this butterfly is ‘iconic,’ it is exactly that,” says anthropologist Columba González-Duarte of the New School for Social Research in New York City. “It has a place now, for North Americans, as that insect that goes beyond borders, that is capable of the impossible.”

Long before anyone understood how far North American monarchs travel, people celebrated their periodic appearances. Mexican poet and novelist Homero Aridjis, whose memoir recalls his childhood in the central Mexican state of Michoacán during the 1940s and ’50s, wrote that the autumn wind “bore currents of butterflies.” Aridjis and his friends would trek to a nearby mountain meadow to watch the butterflies alight in the firs, captivated by the spectacle.

In the 1950s, Canadian zoologist Fred Ur-quhart and his wife, Norah, founded the Insect Migration Association, beginning a long tradition of public participation in monarch research. Over the next several decades, the association recruited some 3,000 volunteers to capture individual butterflies and mark each with a tiny label reading “Send to Zoology University Toronto Canada.” From the resulting data, the Urquharts surmised that monarchs spent the winter in Mexico, but didn’t know where. In 1973, when they placed a call for volunteers in a Mexico City newspaper, Kenneth Brugger, an American expatriate, responded. Brugger’s wife, Cathy, now Catalina Aguado Trail, had been paying close attention to monarchs and other butterflies since her childhood in Michoacán. She agreed to lend her language skills and knowledge of the region to the search for the monarch’s wintering grounds.

For two years, first on weekends and then full-time, the couple crisscrossed the mountains of central Mexico by motorbike and on foot. On the afternoon of January 2, 1975, while climbing a volcanic peak called Cerro Pelón, Trail looked up into the firs and stopped short: The trunks and branches above her were covered with thousands of monarchs, so closely packed that their wings overlapped. When Brugger joined her, they both stood silently, awestruck.

Trail and Brugger’s elation soon turned to worry. The monarch’s winter habitat in Mexico is almost entirely limited to 10 or so small patches of high-elevation oyamel fir forest within an area of 217 square miles. In the 1970s, the local communities that hold communal rights to the forests depended on logging for a living, and the evergreen canopy that protects the monarchs from winter weather was shrinking fast. Crowds of curious visitors could further disrupt the habitat.

As word got out, tourists did travel to the mountains to gaze up at the monarchs. But the news also prompted action. The IUCN called on the Mexican government to protect the fir groves, as did the Mexican environmental group Pro-Monarca. Though the government established a national reserve that in October 1986 banned or limited logging in five of the known wintering grounds, the hoped-for economic benefits of tourism for local communities were spotty, and logging continued.

In 2000, after long and sometimes acrimonious debate among government officials, scientists, conservation advocates, and community representatives, the reserve was expanded threefold to encompass most of the monarch’s known wintering habitat. The Monarch Fund—which is administered by the Mexican government and supported by international conservation groups—began making modest but consistent payments to the residents who hold rights within the core zone of the reserve, partially compensating for lost timber income and successful protection efforts. Around the same time, a group of Mexican sustainable-development advocates founded the organization Alternare, which works with communities near the reserve on projects like reforestation and water conservation.

Thanks to these and other initiatives, logging in the reserve began to decline, and by the early 2010s, annual forest loss had fallen from hundreds of acres to single digits—a major conservation success. Since 2019, forest loss has once again increased, this time because of drought-driven bark beetle outbreaks and the legal logging that is intended to control them. Part of the problem, says geographer Isabel Ramírez of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, is that state forest management policies haven’t caught up with the changing climate.

( Can monarchs adapt to a rapidly changing world? )

Early on a December morning, I follow André Green and his team along a narrow trail into the Sierra Chincua monarch sanctuary in central Mexico. My first impression is that the tall, slender trees around us are covered with rusty foliage. When my eyes and brain catch up to reality, I realize that every fir in sight is draped with slumbering butterflies, wings folded to display their paler undersides. The layers of insects are heavy enough to bend even the sturdiest branches. The cool mountain air seems to vibrate, stirred by the countless wings twitching above our heads.

As the struggle to protect the wintering grounds unfolded in the 1990s and early 2000s, scientists from Mexico to Canada were working to understand the monarch’s astonishing annual journey. Longtime monarch researcher Lincoln Brower and his colleagues learned that while the monarchs that overwinter in Mexico travel north in the spring, they don’t complete the trip; they instead lay eggs in northern Mexico and throughout the southern U.S. When those offspring mature, they continue to the northern U.S. and southern Canada, also laying eggs along the way. During the summer, two or three more generations emerge. The final generation, unlike its predecessors, doesn’t immediately reproduce but enters a state of suspended maturation called diapause. When the days begin to shorten and cool, these aging teenagers head south, returning to Mexico in a single generation.

Since these Mexico-bound monarchs can’t ask their great-grandparents for directions to the winter colonies, scientists reasoned that they must be able to navigate. Through a succession of studies, researchers learned that monarchs are equipped with two compasses: a primary system that uses the sun and a backup system that uses the Earth’s magnetic field.

In a study published in 2009, biologist Christine Merlin and her collaborators found that monarchs use circadian clocks located in their antennae to correct their sun-compass readings for the planet’s daily rotation. While this elaborate system keeps monarchs headed in the right direction, it doesn’t fully explain their ability to home in on the same circumscribed wintering grounds year after year.

In the Sierra Chincua sanctuary, the sun climbs higher above the horizon and the rustling in the trees increases. The monarchs open their wings to bask, warming their muscles in preparation for flight, and the whole forest seems to brighten. On the steep slope above the trail, one of the team’s radio receivers stands ready to detect a sensor-carrying butterfly, just in case one has not only reached Mexico but chosen this stand of firs as a winter home. A few monarchs begin flitting from tree to tree, and soon we’re surrounded by a muffled cacophony of millions of moving wings, a torrent that glows above and around us. Some of the monarchs stream out of the grove, while others weave through the trees, radiant in the filtered sunlight, occasionally dipping low enough to skim our faces and hands. All the while, though, the receiver remains silent.

Since returning to their laboratories at the Universities of Michigan, Delaware, and Pittsburgh, Green and his colleagues have improved the energy efficiency of the sensors, ensuring that the solar panels will be able to harvest enough sunlight in the shady reserve forests. In October 2023, they attached 175 sensors to butterflies in Texas, boosting the chances of capturing a signal when they climb into the Sierra Chincua this winter.

“It’s just a marvelous, marvelous organism, and understanding how it’s able to do what it can do allows us to understand the biological world a little better,” says Green. “So as long as they’re performing the behavior, I’ll be interested in overcoming the obstacles to understand it.”

Why protect the migration of North American monarchs? The answers, I found as I followed their journey, are almost as varied as monarch allies themselves. Some, like Green, are drawn to the butterfly’s mysteries; others admire its beauty and tenacity. Many monarch volunteers form international friendships that they come to value almost as much as the butterflies.

For Jane Breckinridge, co-founder of the Tribal Alliance for Pollinators, restoring monarch habitat is part of a broader endeavor to support species of all kinds, including humans. “Monarchs are special and magical, and I love them,” she says. “But the problems they face are the problems faced by all our native pollinators and all our other native critters.”

( Anyone can help monarch butterflies. All you need is a yard. )

A citizen of the Muscogee Nation in northeastern Oklahoma, Breckinridge grew up in nearby Tulsa, then spent two decades in Minnesota before returning to live on her grandmother’s land in 2004. There, she and her husband, David, opened a commercial butterfly farm, cultivating an array of species for sale to zoos and museums. She started a program called Natives Raising Natives, which recruits tribal members to rear butterflies—and the native plants they need—at home for extra income. In 2014, Breckinridge asked University of Kansas professor Chip Taylor for help in restoring a monarch migration corridor on tribal lands in Oklahoma. Taylor, the founder of the volunteer monarch-tracking organization Monarch Watch, was enthusiastic; he knew monarchs badly needed more habitat in Oklahoma. But he suspected it would not be easy: Patches of native prairie are so rare that locally adapted seed supplies can only be acquired through labor-intensive collection.

Ten years later, the Tribal Alliance for Pollinators is the largest producer of native plants and seeds in Oklahoma, and it works with tribes throughout the Great Plains and beyond. Seeds from 230 native prairie species are available free to all tribal members, and each year the small staff distributes tens of thousands of young plants to individuals and institutions. Tribes throughout Oklahoma have documented breeding monarchs making heavy use of the milkweeds in their pollinator gardens, which also host native bees, small mammals, and other species. The plants benefit humans, too, for some have ceremonial significance or medicinal uses, and all are appreciated for their colorful variety.

The Muscogee Nation is home to two distinct Indigenous languages, Muscogee and Yuchi, and the latter is spoken by a few dozen people. That number, however, is growing: At the local immersion school, preschoolers and elementary students greet the day in Yuchi, then tend to the school’s garden of native plants. During the winter of 2019, inspired in part by the work of the Tribal Alliance for Pollinators, the school’s staff and instructors crowded into a van and drove to central Mexico, where they trekked into one of the sanctuaries to see the butterflies that would, before long, be flying toward the Muscogee Nation.

For school co-founder Halay Turning Heart, who learned Yuchi as a child and now speaks it with her young children, the connection between her work and the monarch’s migration is obvious. “We see the language as essential for our survival, and we know the butterflies are struggling for their survival,” she says. “We recognize that they’re fighting for their habitat and that we’re helping to bring it back.” The sight of the monarchs assembled in Mexico, she remembers, was both awe-inspiring and heart-wrenching: “We knew we might not see it again in the same way. We know how quickly things can change.”

You May Also Like

How to choose just one picture from thousands

See monarch butterflies in all their glory on this California road trip

Monarch butterflies aren't endangered, reversing recent decision. Is that good news?

Nowhere is the enormous challenge of bringing back monarch habitat more obvious than in Iowa. The state’s fertile soil grows more than two billion bushels of corn each year, almost all of which is used for livestock feed or ethanol production, and rural Iowa is dominated by field after field of corn and soybeans. In 1996, when Monsanto began introducing genetically modified crops that are resistant to the herbicide glyphosate, or Roundup, farms across the Midwest started using glyphosate for weed control, killing milkweed and other benign natives in the process.

Today, native plants find refuge on the grounds of the Tallgrass Prairie Center at the University of Northern Iowa, where staff members tend neat rows of milkweed, spiderwort, and other species. The seeds for these plantings are collected in the state’s vanishingly small remnants of native prairie, several located in the 19th-century cemeteries that were among the few places off-limits to settler plows. Every year, commercial seed, some produced from this genetically diverse stock, is distributed to the state’s county road departments, which plant it on Iowa’s road margins.

The program, started more than 30 years ago as an attempt to sustainably manage roadside vegetation, is now one of the most extensive habitat restoration efforts in the state. Iowa transportation officials estimate that about a quarter of the state’s roadsides are planted with native grasses and wildflowers, and the plants frequently host monarchs and other insects. Throughout rural Iowa, county roadside managers serve as informal ambassadors for the value of native prairie, explaining that what may look like a stand of weeds in need of mowing is a low-maintenance, ecologically rich echo of prairies past.

But Iowa’s roadsides cover only a tiny part of the state, and experts say that in order to reproduce at rates that will stave off extinction, North American monarchs require at least twice the amount of milkweed currently available in the entire Midwest—as well as reliable supplies of other nectar-producing natives along their migratory routes. “We need much more than one percent of the land area to counteract all that’s been lost,” says Laura Jackson, the director of the Tallgrass Prairie Center. The state has little public land—state-managed roadsides make up less than a fifth of it—so Jackson and the rest of the center’s staff also work on private-land habitat restoration through the federal Conservation Reserve Program, which contracts farmland for conservation purposes.

In 2018, they began collaborating on a major restoration project with Cathy Irvine, a retired special-education teacher in northeastern Iowa, who has donated almost 300 acres of her family’s corn and bean fields to the center as a tribute to her late husband, David. On a June afternoon, a pair of monarchs flits across 80 acres already thick with milkweed, wild indigo, purple coneflower, and other native flowers and grasses. “None of this will be planted again except as prairie,” she says with satisfaction.

If Iowa embodies the difficulty of prairie restoration, the Irvine Prairie illustrates its possibilities. Getting the right combination of viable native seeds into hospitable ground is no small feat, and restoration practitioners are well acquainted with failure. “Humility is big around here,” says Jackson. Plantings also require periodic burning or mowing to keep out woody species. Once prairie plants take root, however, valuable habitat can happen fast. Irvine and Jackson look forward to the day when seeds from these native species begin to sprout on nearby roadsides, setting forth into the landscape their ancestors called home.

Each spring, the overwintering generation of monarchs in Mexico performs a final spectacular feat, flying hundreds of miles north to lay their eggs. During an April visit to the Muscogee Nation, I watch a single monarch, identifiable as female by her thick black wing veins, travel low over a sunbaked putting green, the ragged edges of her wings a testament to her endurance. If she hasn’t finished laying her eggs—several hundred in total, typically deposited one by one on the undersides of milkweed leaves—she will soon, for her life is nearly at an end. Her progeny, and theirs, will complete the trip north, flying as far as southern Canada.

This defunct golf course, acquired by the Muscogee Nation from a private owner, doesn’t look much like butterfly habitat, but the monarch is snacking on nectar from a cluster of native plants, and more flowers will bloom soon. Collin Spriggs, a conservation botanist with the Tribal Alliance for Pollinators, parks his blue hatchback on the turf and unloads fragrant trays of lemon bee balm and mountain mint seedlings. Leading the small crew of planters is Muscogee Nation wildlife technician Brooklyn Bartling, whose left bicep is tattooed with images of a blackberry, a bee, and a ladybug.

Bartling excitedly describes the nation’s plan to turn the course into a nature reserve, as well as her work helping to remove invasive plants from the grounds and establish native wildflowers. “I’m taking pictures of butterflies, caterpillars, bugs—everything I see here,” she says. “I want to get that information to the public, to put the why behind what we’re doing.”

She and Spriggs stand over a compass plant, a native perennial they’ve been keeping an eye on since planting it last year. Though it has just two leaves, Spriggs says, its taproot may already extend several feet into the subsoil, affording the plant access to water even during the current drought.

Bartling grins at the news and looks up to survey the fairway. “There’s a lot of potential here,” she says. “A lot of potential.”

Related Topics

- MONARCH BUTTERFLIES

- BUTTERFLIES

- ANIMAL MIGRATION

- WILDLIFE CONSERVATION

- ENDANGERED SPECIES

- PHOTOGRAPHY

- NATURE PHOTOGRAPHY

- WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY

Whales and butterflies are the real celebrities in Santa Barbara

These photos are works of art—and the artists are bugs

Can monarchs adapt to a rapidly changing world?

These national parks have some beautiful bugs—see for yourself

Millions of butterflies stop in these Mexico sanctuaries. Here’s how to see them.

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Gory Details

- 2023 in Review

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts

- Money market accounts

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Car insurance

- Home buying

- Options pit

- Investment ideas

- Research reports

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Where and when to look for monarch butterflies this summer in North Central Mass.

It's the season for outdoor hobbies, and as gardeners prepare their grounds for the seasonal harvest, they should remember to grow plants, like milkweed, to support monarch butterflies.

Milkweed is the most important plant in the life cycle of a monarch. Adult female monarchs only lay their eggs on milkweed leaves because it's the only plant that monarch caterpillars can eat before they cocoon and develop into monarch butterflies.

It takes three generations of monarch butterflies to complete their annual 3,000-mile migration journey to dozens of New England communities. Monarchs migrate all over the Northern U.S. and Canada from Mexico and Southern California.

The monarch butterfly lifecycle

Adult monarchs can be found throughout the commonwealth, from the Quabbin region to the North Shore. Hundreds of thousands of these butterflies migrate north from the boreal forest of Michoacán, Mexico, starting in February and March.

The monarchs begin to mate in Mexico before they journey north to their first stop in Texas, where the second generation is hatched. Then, the second generation sets off to Virginia, where they will mate and produce the third generation. After a month-long trip, the third generation eventually arrives in Massachusetts and other New England states.

Massachusetts residents can anticipate the third generation of monarchs arriving in June. The monarchs will start their search for milkweed to lay their hundreds of eggs so the next generation can begin the journey back. Adult monarchs stay in Massachusetts from June to August. Between September and October, the next generation begins the annual winter migration back to Mexico.

On their way back to Mexico in the fall, monarch butterflies go through a similar three-generation journey, stopping along the way to mate and reproduce a new generation of monarchs to complete the migration pattern before winter starts.

An adult monarch's expected life span is between 60 and 70 days, and it takes about 20 to 39 days for an egg to hatch into a caterpillar and then become a monarch butterfly.

Martha Gach, regional education manager and conservation coordinator at Mass Audubon, said there shouldn't be any delays in the migration pattern as long as the weather in the south is warm.

Where to find monarch butterflies?

Dr. Loree Griffin Burns, a naturalist and author, said people should find adult monarchs anywhere with a thriving milkweed population.

During summer, people can only find monarch eggs and caterpillars on milkweed leaves and cocoons.

Gach said there are over 70 milkweed species native to the United States. Still, there are three native milkweed species in the North Central Mass. region: common milkweed, found in any grassy field or blooming backyard; rose milkweed, found in swampy marsh wetlands in the area; and butterfly milkweed, which grows in dry grass fields.

Here are five parks and conservation sanctuaries in the Greater Gardner with a large milkweed population:

Lake Wampanoag Wildlife Sanctuary in Gardner

Wachusett Meadow Wildlife Sanctuary in Princeton

Otter River State Forest in Baldwinville

High Ridge Wildlife Management Area in Westminster

Broad Meadow Brook Conservation Center and Wildlife Sanctuary in Worcester

What to do if you want to help preserve the monarch butterfly

For the past two decades, the monarch population has declined rapidly due to illegal deforestation of the boreal forest in Michoacán, Mexico, said Gach.

People can take several small actions to help support the monarch population this summer. Gach said people can participate in No Mow May, where they don't mow their lawns for the whole month to prevent the cutting of milkweed and other flowering weeds that feed the monarch butterflies and other pollinators.

Planting milkweed in the backyard or garden can help the female monarch find a place to lay her eggs. Gach said people can also avoid spraying pesticides and weed killer in their yards and gardens because those chemicals can kill pollinators like the monarch.

This article originally appeared on Gardner News: Monarch butterflies need milkweed to migrate from Mexico to New England

Recommended Stories

D.j. wagner continues 5-star exodus from kentucky; zvonimir ivišić following john calipari to arkansas.

Wagner joins a pair of freshmen teammates and several 5-star recruits leaving Kentucky after Calipari's exit.

WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert: League is 'pretty confident' it will expand to 16 teams by 2028 season

Engelbert said Philadelphia, Toronto, Denver, Nashville and South Florida are potential expansion spots.

Severe storm season is here: How to stay safe during heavy rain, lightning and tornadoes

Experts say to stock up, pay close attention to weather warnings and stay off the roads as increasingly severe weather sweeps the U.S. in the spring.

Threads is testing real-time search results

Threads is testing a new search feature that will allow users to filter results by recency, Adam Mosseri confirmed.

Report: USA basketball roster for Paris Olympics to feature LeBron James, Stephen Curry, Joel Embiid

USA Basketball is finalizing its roster for the upcoming Paris Olympics

WNBA Draft: Iowa star Caitlin Clark selected No. 1 overall by Indiana Fever

It’s finally official. Caitlin Clark is a member of the Indiana Fever.

'Had both feet on the ground the whole time': Clean your gutters with this clever tool, down to just $30

Use your hose and this telescoping gadget to tackle a dreaded chore without the high-wire act.

WNBA Draft 2024: Caitlin Clark goes No. 1 to Indiana Fever; Angel Reese joins Kamilla Cardoso on Chicago Sky

Follow along as Caitlin Clark, Cameron Brink, Angel Reese and more find their WNBA homes in Monday's draft.

Grand Canyon's Tyon Grant-Foster, after multiple heart surgeries and NCAA tournament run, declares for NBA Draft

Tyon Grant-Foster led the Lopes to their first ever NCAA tournament win earlier this year.

Save 25% on this Hotor trunk organizer and clean up your car for under $15

In the market for a trunk organizer? This one from Hotor is a top 5 best-seller on Amazon and it's available for under $15 today.

- Show search

Climate Change Stories

Monarch Butterflies Bring Together Conservation and Culture Between U.S. and Mexico

Preserving the monarch butterfly and its unique migration across North America protects a cultural icon.

September 06, 2021

Every fall, as temperatures begin to drop in North America, monarch butterflies from as far north as Canada set out on a migration to warmer, southern climates.

The bright orange and black butterflies flap and glide from asters and goldenrods to coyote bush and rabbitbrush, traveling up to 100 miles per day. They are bound south, instinctively seeking the forests that offer the perfect conditions for overwintering.

As the only butterfly species that completes a two-way migration, the monarchs will begin their return to the north in the coming spring. Individual butterflies live four to five weeks on average, so it will be their descendants—most likely their great-great-grandchildren—that will reach the northern states and complete this epic journey.

But monarch butterflies and their migration are now threatened by temperature changes, drought, and other climate change impacts. A long-term decline in numbers among eastern and western populations shows how vulnerable monarchs are in North America.

As pollinators, the monarch butterfly migration across the continent provides an invaluable service, essential for many ecosystems to thrive. It is thanks to pollinators, such as butterflies, bees, and other insects, that we have many of the flowers and dietary staples that we enjoy, like squash and blueberries.

Monarchs have another irreplaceable role across North America—that of a cultural icon.

Cultural Significance of Monarch Butterflies in Mexico

Among many Mexican communities in the Midwest and eastern United States, the monarch butterfly migration to Mexico is symbolic.

The butterflies that embark on a 3,000-mile southbound journey were born in the United States and have never been to Mexico. And yet, they are driven by environmental factors to glide south until they reach the oyamel fir forests of Mexico, mainly in Michoacán.

“In Mexico, even before the Spanish colonization, you could see images of butterflies through stone carvings and paintings of Indigenous groups,” said Joel Perez-Castaneda, Project Director for The Nature Conservancy (TNC) Indiana.

Quote : Joel Perez-Castaneda

In some stories, they are the returning souls of loved ones. In others, butterflies are returning warriors that were killed in battle.

Joel Perez-Castaneda

“These butterflies were part of that culture. To this day, in cultural celebrations, you can see the bright orange, black and white colors, hear the references in songs, and see the dances that mimic the butterfly’s movements.”

Adding to the mystique of thousands of butterflies funneling into the Mexican forests every fall is the fact that monarchs arrive around the same time when Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) is celebrated in early November.

“There are many legends and myths about monarchs and other butterflies, a lot of times tying them to the souls of their ancestors,” said Perez-Castaneda.

“In some stories, they are the returning souls of the loved ones. In others, butterflies are returning warriors that were killed in battle. The truth is that a lot of Indigenous groups believe that, even after passing on, their souls lived through nature and the environment. It says a lot about how much they really appreciated nature and its surroundings and cared for it.”

Preserving and Celebrating the Monarch Butterfly Journey

Across many states in the U.S., from Florida to Indiana, conservationists lead diverse and complementary efforts to protect the monarchs —from creating butterfly gardens where monarchs feed or lay their eggs, to preserving the lands they visit and pollinate during their migration.

“Northwest Indiana has a strong Mexican community presence, since many Mexicans moved to the area from Mexican states such as Michoacán, where the monarch overwinters,” Perez-Castaneda said.

In East Chicago, Indiana, The Nature Conservancy and its partners are not only engaging with the community to protect the butterfly, but also uniting in celebrating the monarch.

El Festival de la Monarca (The Monarch’s Festival) is a community event that occurs in September, while the butterflies are migrating through northwest Indiana on their way to Mexico. The celebration includes educational activities for people of all ages, as well as music, art, and dance.

“All it took is for us to pay attention to the community to realize that the love of the monarch was already there,” Perez-Castaneda said. “You can drive around East Chicago and see businesses with images of the butterfly, from ice cream shops to restaurants. We want to connect residents to the natural areas around them and guide them on how they can support the monarch and other pollinators through native gardening, local conservation, learning about the monarchs and taking other actions. This Festival is the place where culture meets science and serves both nature and people.”

In previous years, the festival has offered a webinar about native plants, a monarch-themed window decorating contest, field trips, and a bilingual hike in English and Spanish.

Although the monarch is an enduring symbol among many communities, during recent decades the presence of this species at overwintering sites in Mexico has declined significantly . Populations in North America have decreased from approximately one billion in 1996 to only about 100 million in 2016.

Support the monarch & help preserve its migration

- Explore TNC’s work to support monarchs in Florida , Oklahoma and Nevada .

- Plant a pollinator garden in your home or community.

- Support science education in your schools with Nature Lab .

We All Need Thriving Pollinators

Declining monarch populations across North America could be a sign that other elements of their habitats, such as wildflowers or other pollinators, might be fading too. We need to protect the balance and biodiversity of our natural ecosystems for humans and nature to thrive together.

The disappearance of large areas of native plant habitats is a major contributor to the decline of pollinator populations worldwide. Another major factor is climate change. For monarchs, if temperatures get too warm during spring, they might migrate farther north than before. Then when winter comes, the longer trip to overwintering sites in Mexico could overtax them and decrease their reproduction.

Changes in the monarchs’ migration patterns impact diverse ecosystems across the continent, and ultimately affect our human food systems, too. Although butterflies are among the more noticeable—and charming—pollinators when they visit a garden or field, bees, hummingbirds, moths, and bats also play an important role pollinating many food crops , as well as 75% of the world’s flowering plants.

More Monarchs

Monarch Butterfly

Researchers estimate that a jaw-dropping 970 million monarchs have vanished since 1990. Learn more about these incredible butterflies and how you can help protect them.

Orlando Metro Cities Program

This program seeks to improve the quality of urban life by working with communities to integrate nature-based solutions in the six-county Orlando Metro region.

Building Neighborhoods for Nature and Pollinators

Learn how one OK Conservation Leadership Academy member was inspired to incorporate nature into housing development design.

We personalize nature.org for you

This website uses cookies to enhance your experience and analyze performance and traffic on our website.

To manage or opt-out of receiving cookies, please visit our

- News/Events

- Arts and Sciences

- Design and the Arts

- Engineering

- Global Futures

- Health Solutions

- Nursing and Health Innovation

- Public Service and Community Solutions

- University College

- Thunderbird School of Global Management

- Polytechnic

- Downtown Phoenix

- Online and Extended

- Lake Havasu

- Research Park

- Washington D.C.

- Biology Bits

- Bird Finder

- Coloring Pages

- Experiments and Activities

- Games and Simulations

- Quizzes in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality (VR)

- World of Biology

- Meet Our Biologists

- Listen and Watch

- PLOSable Biology

- All About Autism

- Xs and Ys: How Our Sex Is Decided

- When Blood Types Shouldn’t Mix: Rh and Pregnancy

- What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

- Understanding Intersex

- The Mysterious Case of the Missing Periods

- Summarizing Sex Traits

- Shedding Light on Endometriosis

- Periods: What Should You Expect?

- Menstruation Matters

- Investigating In Vitro Fertilization

- Introducing the IUD

- How Fast Do Embryos Grow?

- Helpful Sex Hormones

- Getting to Know the Germ Layers

- Gender versus Biological Sex: What’s the Difference?

- Gender Identities and Expression

- Focusing on Female Infertility

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Pregnancy

- Ectopic Pregnancy: An Unexpected Path

- Creating Chimeras

- Confronting Human Chimerism

- Cells, Frozen in Time

- EvMed Edits

- Stories in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality

- Zoom Gallery

- Ugly Bug Galleries

- Ask a Question

- Top Questions

- Question Guidelines

- Permissions

- Information Collected

- Author and Artist Notes

- Share Ask A Biologist

- Articles & News

- Our Volunteers

- Teacher Toolbox

show/hide words to know

Migration: movement of an animal or a group of animals from one place to another.

How Far Do Monarch Butterflies Travel?

Imagine you are a tiny monarch butterfly. How far do you think you will travel as you migrate from your winter home to your summer home? Keep in mind that an average stick of gum weighs four times as much as your new monarch body. As you think about this, also ask yourself where your summer home is and if you have just only one.

Once you spend a minute or two thinking about life as a butterfly, click on the map below to see where you might travel.

Animated Monarch Migration Map

Click on the map of Central and North America to see the migration path of some monarch butterflies.

What's the Story Behind the Monarch Butterfly Migration?

If you looked closely at the animation, you will see there are different paths that the monarch butterflies take to and from their winter homes. Many butterflies on the west side of the Rocky Mountains travel to the north central coast of California, about 500 kilometers (~300 miles).

Many monarchs from the eastern population travel all the way to the Sierra Madre mountains in central Mexico. A monarch born in Canada would have the farthest journey of all, nearly 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles). We now know that not all butterflies use these strict migration routes and we are hoping to learn more about why certain butterflies have specific routes.

As the butterflies fly north for the summer they produce several generations. However, the monarch in Canada returning to Mexico has to do this on its own. Think how far the tiny butterfly has to travel. In comparison, a 150 pound person would have to travel more than 13,000 times around the Earth to do what the monarch does! *

Monarchs gather at Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. Click to enlarge. Image by Pablo Leautaud - via Creative Commons

Such a long migration requires lots of energy. Not only do the butterflies have to fly, they have to eat. During each day of the trip, the monarchs must visit hundreds of flowers to get enough nectar for their trip.

Not All Is Well with Their Winter Home

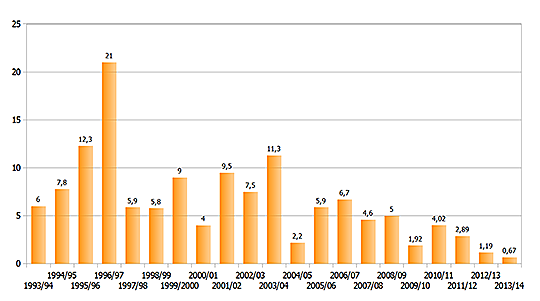

Over the years, the winter home in Mexico has been shrinking. This means fewer monarch butterflies are able to survive the cold months. How this will impact them is something that scientists and concerned citizens are investigating. It is clear from the graph below that size of the habitat is growing smaller each year.

* How'd you figure that?

Let's say the average butterfly weighs 500 milligrams and the distance they will fly from Canada is about 4,000 kilometers.

For every milligram of body weight, the monarch would have to fly 8 kilometers.

4,000 / 500 = 8

Now, if we take our 150-pound person (150 pounds equals ~68,000,000 milligrams) and have them travel 8 kilometers for every milligram of body weight, they would travel 544,000,000 kilometers.

68,000,000 X 8 = 544,000,000

The circumference of the Earth is around 40,030 kilometers. When you divide total travel distance by the circumference of the Earth, you get 13,590.

544,000,000 / 40,030 = 13,590

Now you give it a try -

How many trips could the same person take from Earth to the moon and back to equal what a monarch does? We will give you one hint: the average distance from the Earth to the moon is 384,403 kilometers.

Image credit: Monarch Migration Map Animation by Harald Süpfle - via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: Migrating Monarch Butterflies

View citation, bibliographic details:.

- Article: Monarch Migration Map

- Author(s): Tracy Fuentes

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: December 18, 2009

- Date accessed: April 13, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/monarch-migration

Tracy Fuentes. (2009, December 18). Monarch Migration Map. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved April 13, 2024 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/monarch-migration

Chicago Manual of Style

Tracy Fuentes. "Monarch Migration Map". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 18 December, 2009. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/monarch-migration

MLA 2017 Style

Tracy Fuentes. "Monarch Migration Map". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 18 Dec 2009. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 13 Apr 2024. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/monarch-migration

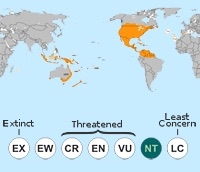

Monarch Butterflies are found mainly in North, Central America and part of South Americas and are listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

Migrating Monarch Butterflies

Coloring Pages and Worksheets

Monarch Life Cycle

Be Part of Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.

Share to Google Classroom

Interactive Map: Hummingbird migration is underway. Here’s what you can do to attract them

HIGH POINT, N.C. (WGHP) — Many people, not just passionate bird-watchers, look forward to seeing hummingbirds every spring!