Whakaari/White Island

White Island, Bay of Plenty

By GrahamIX

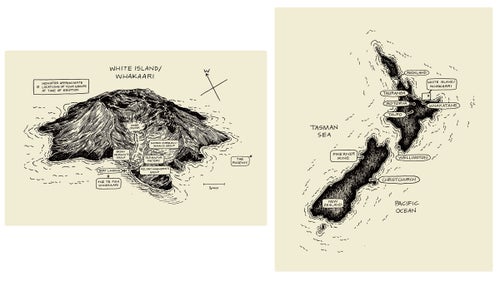

Whakaari / White Island is one of New Zealand’s most active volcanos, situated 48km off the coast of Whakatane in the North Island.

In December of 2019 a volcanic eruption occurred at Whakaari / White Island .

To ensure the safety of locals and visitors there are currently no boat tours to, or helicopter flights that land on the island.

While visitors cannot set foot on the Whakaari / White Island, scenic flights are still available.

If you wish to know more about Whakaari / White Island, visit the GeoNet website's frequently asked questions page. (opens in new window)

- Share on Facebook

- Share by email

Where to next?

Bay of Plenty Attractions long-arrow-right

Bay Of Plenty long-arrow-right

Whakatāne long-arrow-right

Autumn like this?

see & do .

Moutohorā Eco Sanctuary

See all events.

Autumn Events Guide 2023

School Holiday Events

Feature Events

Plan your trip.

Kiwi Capital of the World ™

- Live A Work

Whakaari/White Island

Whakaari/White Island is an active marine volcano that has attracted visitors from around the world for decades. To Māori and local Iwi (tribe) Ngāti Awa, Whakaari is a treasured ancestor and features in many stories and legends of the region. Glimpses from the shore and in the air offer breath-taking views of this geothermal wonder.

Estimated to be between 150,000 and 200,000 years old, the volcano is located 49 kilometres offshore from Whakatāne. It is two kilometres in diameter and its peak rises 321m above sea level.

The tragic eruption event that occurred at Whakaari / White Island on Monday, 9 December 2019 significantly impacted many people, both in Aotearoa and internationally. We acknowledge the families and loved ones of those who passed away, and send strength to the injured and their families during their recovery. As a result of the eruption event, there are currently no on-land tours of the island in operation.

You can still experience the unforgettable sights of Whakaari/White Islands, including scenic flights, on-land (not the island) lookout points and in the Whakaari/White Island Experience Room at the isite Visitor Information Centre.

White Island Flights

For a truly unforgettable experience, join the White Island Flights team for one of their great value White Island scenic flights.

Whakaari Experience Room

The Whakaari/White Island Experience room provides a stunning up-close and informative experience of this geothermal wonder.

Remarkable visibility, underwater steam vents and an abundance of marine life make the waters around the island one of New Zealand’s best dive sites. It’s also a fishing haven, with charter boats offering multi-day game fishing adventures.

Lookout points

There are several lookout points in the Eastern Bay of Plenty that provide views across the ocean to Whakaari/White Island. On a clear day you can see steam clouds puffing from the crater at The Whakatāne Heads, Kōhī Point or any spot along the coastline.

If you have any questions about your visit to the Whakatāne District, please contact our isite Visitor Information Centre team .

Want to know more about Whakaari / White Island, visit the GeoNet website's frequently asked questions page .

Summer like this?

Whakatāne is the ultimate summer destination. The ideal place to Rewind, Connect and Reset for your summer.

Matador Original Series

How to See Volcanic Whakaari/White Island in New Zealand

W hakaari, or White Island, is a volcanic island in the Bay of Plenty off the east coast of New Zealand’s beach-covered North Island . It’s the most active volcano in New Zealand and one of the most studied volcanoes in the world. Whakaari has been active for at least 150,000 years, with frequent eruptions throughout its history. Whakaari has had several deadly eruptions over the past 200 years, including an eruption in December 2019 that killed 22 people.

If you’ve watched the recently released Netflix documentary The Volcano: Rescue from Whakaari , you know that it’s not a place to underestimate.

Because of this, Whakaari/White Island is currently closed to tourists , but you can still do scenic flights over the island. So here’s what to know about scenic flights over Whakaari/White island, plus what to know when or if it opens for hiking tours once again.

Where is Whakaari?

Whakaari/White Island tours

Tauranga, New Zealand. Photo: Tauranga /Shutterstock

Whakaari/White Island tours typically leave from Whakatane (a four-hour drive from Auckland) or Tauranga (about three hours from Auckland). Whakatane is the closest mainland town to Whakaari and is the most popular departure point for organized tours.

When exploring the island on foot is allowed, you can book trips from several area tour companies, some of which offered the opportunity to camp on the island (and may again whenever it reopens).

When the island is closed to foot traffic, seeing the island from air is the only option. But that’s no problem, since seeing it from air may give you the best perspective of the uniquer island (and save you from smelling some seriously strong sulfur). White Island Flights offers scenic flights over Whakaari, offering stunning views of the iconic landscape from up high. Hour-long tours start at $249 NZD, or about $159 US.

What will you see at Whakaari?

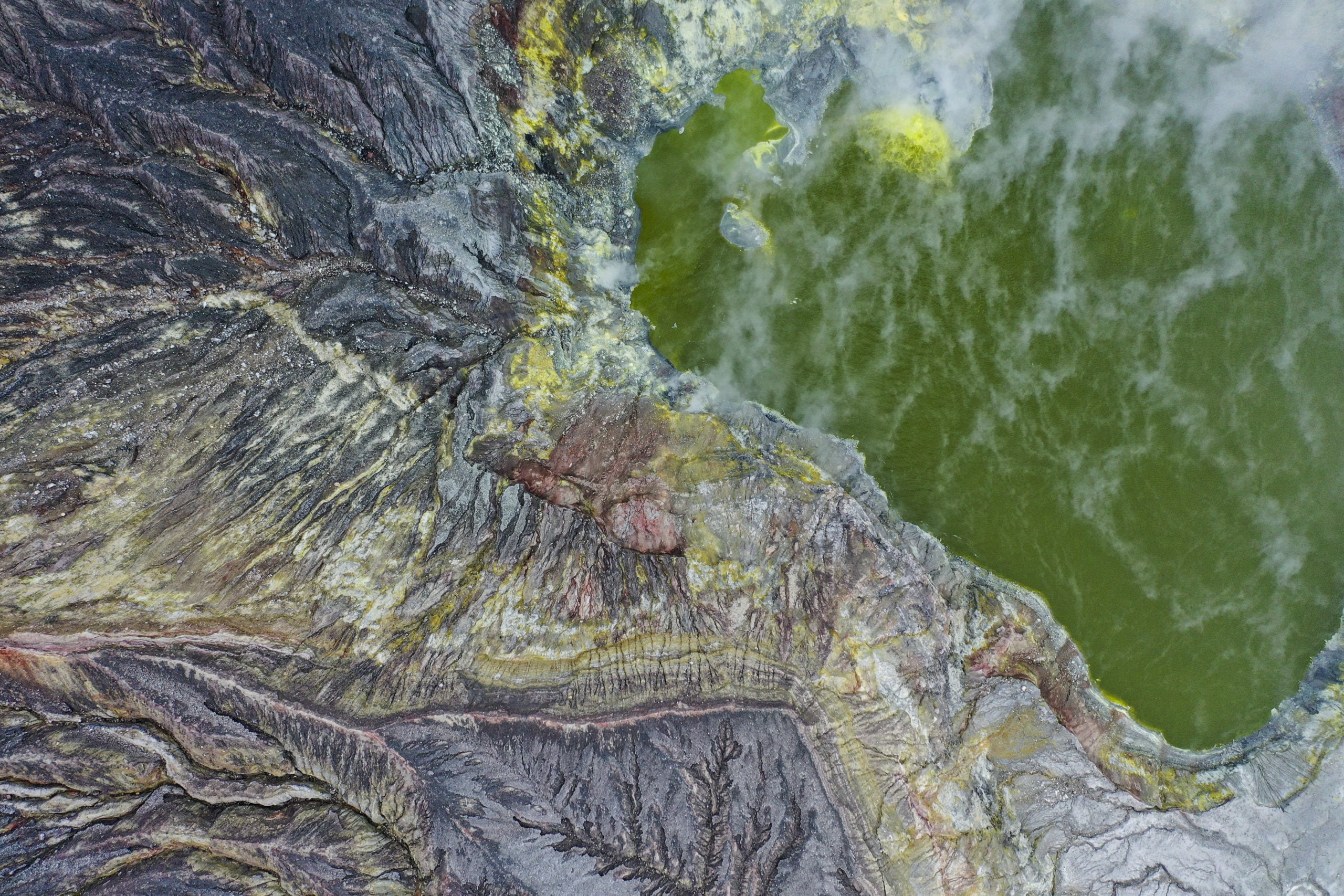

Photo: Jeff C. Photostock /Shutterstock

Whakaari/White Island offers some truly unique experiences for its visitors. Aside from the active volcano itself, there is a variety of geographical features including hot springs, fumaroles, craters and steam vents where one can observe the active processes of Whakaari. Fortunately, it’s easy to see all of these from the air.

Whakaari also has its own unique fauna and flora, with several species that are endemic to the island. The extreme environment has led to some unique evolutionary adaptations, and species you’ll see there include the Whakaari skink, Whakaari gecko, and Whakaari cicada.

Is Whakaari safe?

Whakaari/White Island is an active volcano, and as such visitors must take extra safety precautions. All trips to Whakaari should be organized through reputable companies that have experience dealing with volcanic activity and know the risks associated with it. It is also important to check in advance if there have been any recent eruptions or seismic activity. When the island is closed to foot traffic, never try to charter your own boat. Planes and helicopters can make quick getaways if they notice any unpredictable seismic activity; hikers can’t. Be smart.

Whakaari eruptions

Photo: Jet 67 /Shutterstock

Whakaari has had several explosive eruptions over its long history, producing pyroclastic flows and ash plumes that have the potential to disrupt air travel in the region. Whakaari is monitored 24/7 by GeoNet, a government agency tasked with monitoring volcanic activity in New Zealand. The most recent major eruption occurred on December 9th 2019, and Whakaari has also had several smaller eruptions since then, including one as recently as March 2021. Scientists continue to monitor Whakaari’s activity and will close foot traffic to the island during periods of extended activity (which is the case as of December 2022).

When will Whakaari/White Island reopen?

Photo: Photo Image /Shutterstock

Whakaari remains closed to visitors as of January 2023. The question of when it will reopen is a difficult one and is still uncertain. Whakaari needs to be assessed for the short-term impact of the eruption and potential long-term effects on its geology and environment before any informed decision can be made.

More like this

Trending now, this new zealand lake is getting an electric hydrofoil ferry, discover matador, adventure travel, train travel, national parks, beaches and islands, ski and snow.

- Science & Environment

History & Culture

- Opinion & Analysis

- Destinations

- Activity Central

- Creature Features

- Earth Heroes

- Survival Guides

- Travel with AG

- Travel Articles

- About the Australian Geographic Society

- AG Society News

- Sponsorship

- Fundraising

- Australian Geographic Society Expeditions

- Sponsorship news

- Our Country Immersive Experience

- AG Nature Photographer of the Year

- Web Stories

- Adventure Instagram

What really happened on Whakaari/White Island?

THE ERUPTION BEGAN at 9.35pm with big heaves inside the crater. By 10.03pm it was pelting the nearby walking track with projectiles, but withheld its final energy until 10.11pm, when with a whoomph it sent a plume sky-high. A scalding current of steam and debris, coloured green by hydrothermally altered rock, rolled right across the track at 11m/s, and down to the south-eastern bays.

This eruption took place on Whakaari/White Island, New Zealand, on 27 April 2016, more than three years before the catastrophe in December last year that claimed the lives of 21 people (17 of them Australians) and injured 26 others.

Geologists from GNS Science, NZ’s leading provider of geoscientific research, reconstructed the pulses of the eruption from acoustic and seismic data, and, three weeks later when they could safely land on the island again, began figuring out the reach of those pulses.

The resulting scientific paper was published on 1 April last year, and its authors warned: “These eruptions clearly pose a significant hazard to the tourists that visit the island.” More than a quarter of the walking track had been bombarded by rock fragments. The pyroclastic surge, though just 5mm thick at its extremities, had nonetheless covered 95 per cent of the track.

You might wonder if this eruption triggered any changes, but it happened at night, with no witnesses, so it simply passed on by. You might, therefore, be tempted to wish it into the daylight, when tourists would have been afoot, because then it might have garnered more notice – since it came in pulses of ascending violence, there would have been time to run, and the headlines would have been nothing more than “Tour operators reassess risk after near miss”. It would have been a wake-up call that produced only meetings over cups of tea, with scribbled notes, bottom-line business interests weighed against risk, and some kind of agreed reform.

Three years later, at 2.11pm on 9 December 2019, there was another eruption – one that came without warning. Except, perhaps, that on 8 December the instruments that measure tremors in nanometres momentarily spiked 30 per cent higher than any tremor during the previous two months. Or perhaps for a moment during a video shot by tourist Allessandro Kauffmann earlier in the afternoon. Kauffmann was part of the group aboard Phoenix , a White Island Tours vessel, and he videoed much of the island tour. At about 1.30pm, he panned along the hot, strangely bright stream flowing from the crater lake. Amid the snap and spit of boiling mineral water, the microphone caught an off-camera aside by a White Island Tours guide: “I’m a little bit worried why it’s going green.”

Whakaari’s dangerous charm

Attitudes to Whakaari have long been cavalier. In 1914 miners drained the crater lake to uncover deeper deposits of sulphur. Geologists suspect this affected the stability of the crater cliffs, because in September that same year, a 300m-wide chunk collapsed. As it fell, the rock, weakened by heat and saturated with water, mutated from an avalanche into a highly fluid lahar (a violent type of mud or debris flow), which ran for more than 1km eastward to the sea, burying the 11 miners and destroying the sulphur factory.

Then, during Whakaari’s long eruptive phase from 1976 to 1982, the keen young geologists of the NZ Geological Survey’s Rotorua office put together the first comprehensive analysis of the volcano’s mighty hydrothermal systems. They were often photographed as minute specks against vast up-rushing columns of steam, or in front of dark umbrellas of mud thrown up by the vents. They were out there for hours, measuring the gradual expansion or contraction of the crater floor, even when the volcano was – to use their word – “ashing”, the grey flakes coating their hair and clothes.

“We took risks and didn’t even think about it,” says Ian Nairn, who was one of that group. “We often went out straight after a serious eruption. It was our job, our interest, and the main problem was how long it took to organise a boat or a helicopter.”

Peter and Jenny Tait first became similarly transfixed by the volcano’s dangerous charm when they took a group from Germany on a fishing charter, but, at the Germans’ impulsive request, finished up exploring the island. The Taits built a business out of taking tourists to stand at the junction of the real world and the unruly energy of the underworld: the strange colours, the steaming lake, the crater cliffs painted bright yellow at their base and then rising almost vertically to 300m, cupping the humans below within a thrilling amphitheatre.

“That first trip was in 1990,” Tait tells me, “and, as it developed, Jenny and I were taking six people a day there. It was very personal. The reaction of the punters was, ‘It’s unbelievable,’ and that’s what drove us to keep developing it.”

In 2017 the Taits sold their business, White Island Tours – a 27-year-old enterprise that came with a motel and cafe – to Ngati Awa Group Holdings, which kept on many of the Taits’ employees.

“Safety?” Tait says, when asked about the potential risks of taking visitors to an active volcano. “We were more worried about the Whakatane River bar than the island erupting, to be honest. There were so many things. It was an adventure trip. You have to cross the river bar. You have to cross pretty rough ocean, then get into an inflatable and land, with very tricky conditions, to get onto the island at times. And you’re on the island a very short time, really. The overall chances of it erupting seemed pretty small.”

On the afternoon of 9 December, Tait was sitting in his lounge, high on the rocky ridge that overlooks Whakatane and out across 50km of blue ocean to Whakaari. He saw the eruptive column’s silent rise. He didn’t know if there were people on the island or not.

The rescue mission

Those aboard Phoenix knew. At about 2pm, passengers had returned to the vessel, which was moored in Te Awapuia Bay on the south-eastern corner of the island. Phoenix motored north around Troup Head, giving its passengers one last photo opportunity directly up the crater, before it turned south to return to Whakatane.

It was right at that moment, to gasps of pure wonder, that the eruptive column boiled into the sky. Then the column darkened at the base, and a sinister ground-hugging wave steadily overwhelmed the island, billowing towards the vessel. The framing on every camera went up, down or sideways, jerking with fear.

The skipper accelerated clear of the ash cloud, and for his passengers the eruption was no more than a terrible fright. But there were people on board who knew that White Island Tours’ new flagship vessel, Te Puia Whakaari , was still moored back at Te Awapuia Bay, and that its tourists were still on shore. That meant 38 passengers from the cruise liner Ovation of the Seas , plus four guides.

Meanwhile, the Rotorua-based company Volcanic Air had brought four tourists to the island on a Squirrel helicopter that the company’s pilot and guide had set down on a landing pad behind the ruin of the sulphur factory. That made 47 people still on the island.

At 2.14pm, Phoenix sent out an emergency call to Coastguard Whakatane, advising of an eruption and requesting urgent medical evacuation. Phoenix then sped back to Te Awapuia Bay, and called the coastguard again at 2.16pm, confirming casualties. Minutes later, Te Puia Whakaari also contacted the coastguard. The three calls triggered a Civil Defence emergency, alerting police, St John Ambulance services, rescue-helicopter services and hospitals on the mainland.

But Whakaari lay across 50km of rough ocean, far from any immediate help. As national agencies began to tool up, the locals were already organising their own ship-to-shore and air-to-ground rescues.

At Te Awapuia Bay, the ash had already cleared. The sky was once again blue and the sun shone, but Te Puia Whakaari and the island itself were a dull, flat grey. Phoenix ’s skipper kept his engines running, ready to speed clear if the volcano blew again.

Paul Kingi was a senior skipper and the tours manager at White Island Tours, but he’d joined Phoenix that morning simply as a guide and was free of any captain’s responsibility to stay with the vessel. He took immediate charge of the rescue, loading two crewmates into Phoenix ’s inflatable, then gunning its motor to intercept a woman swimming towards Te Puia Whakaari . After plucking another two women from the water, he took all three to Phoenix . Then he turned to the dozen or so people, grey with ash, who were huddled on or near the island’s landing.

As the sea-to-shore rescue got underway, an air-to-ground rescue was assembling. The rising plume from Whakaari had served as a shrill alarm for pilots from Whakatane, Rotorua and Taupo. Mark Law, head pilot of Whakatane-based helicopter operators Kahu NZ, saw the eruption as he drove back from Tauranga in his car. He got on the phone, and the Kahu base confirmed that GNS Science’s monitoring cameras on the island had blanked out. Simultaneously, high above the blue expanse of the Bay of Plenty, a helicopter pilot who had lifted off from Whakaari just six minutes earlier called his head pilot, Tim Barrow, at Volcanic Air, and described the scale of the eruption. Barrow then called Law.

Meanwhile, retired helicopter rescue pilot John Funnell was in the air in a small fixed-wing aircraft near Whakatane, keeping up his flying hours. As two Kahu choppers prepared to lift off for Whakaari, with pilots Law, Jason Hill and Tom Storey aboard, Funnell was enlisted as ‘top cover’, a specific role within emergency operations – the top cover is the fixed-winger that circles high above the scene and transmits information received from the team below.

So a small airborne unit was formed, bound together not by official roles or rehearsals, but by the natural meshing of grave concerns and aided by local knowledge of landing pads within the crater.

By then, the sea-to-shore rescue was closing up, and Phoenix had become a de facto hospital ship. Kingi’s inflatable had delivered the people on the landing to the vessel, including the four Volcanic Air tourists and their pilot. Three of those five were probably the luckiest people on the island that day, because when the volcano blew they were already at the shoreline, the last point of interest in their hour-long tour. The pilot urged them into the water, and he and the two who immersed themselves escaped serious injury. The other two hesitated, and were later hospitalised for burns.

Kingi, back on the island, had gone inland on the walking track towards the crater to find more survivors and help them down to the inflatable. The last person Kingi found, just as he had decided to stop searching, was 19-year-old Australian Jesse Langford, who stumbled down towards him. Jesse had been more than 300m inland when the volcano blew. He was his family’s only survivor, because his father, Anthony, mother, Kristine, and sister, Winona, passed away around him.

At about 2.45pm, Phoenix took off for Whakatane. The Kahu helicopters above and the vessel below crossed paths just before 3pm, and Law swooped low, the urgency of his mission and the scale of it confirmed by the sight of prone people being tended to on the back deck.

Those who had sustained the worst burns had been placed at the front of the vessel, and two doctors had stepped forward from among the passengers to tend to them – a general practitioner on holiday from the UK, and another from Germany.

Geoff Hopkins, a pastor at Arise church in Hamilton with a St John certificate, also provided assistance. He dug deep into remote first-aid training he’d done in the UK, but he was dealing with people drifting in and out of consciousness, people who were saying, “I’m not going to make it.” So he dug deeper yet, into his faith, and told them, “You’re not going to give up.”

His daughter, Lillani, was at the back of the vessel with the other victims, doing her best to stave off hypothermia and shock. She found herself singing the evangelical song “Waymaker”:

You are here – moving in our midst…

You are here – working in this place…

You are here – healing every heart…

And if she stopped there’d be a touch on her leg, and a whisper: “Keep singing.”

Halfway back, Phoenix was met by a coastguard vessel delivering paramedics and pain-relief medication.

About 3pm, the Kahu helicopters entered the crater airspace, and Law descended to 200 feet for a closer look. The centre of the island was now mostly clear of steam and ash. He saw some figures lying down, and others sitting – there were people alive down there. The Kahu pilots set their choppers down on the crater floor and got out of their machines, scuffing through the grey ashfall, amid dense gases and drifting ash.

Breathing was difficult, even with gas masks. They assessed the dead, the dying and the living. Through a handheld radio – they had to remove their gas masks to speak into it – they described injuries to Funnell, their top cover, who relayed the information to Whakatane Hospital.

The fliers felt the desperation in everyone they encountered, and their response was to talk back, to comfort, to tell each person, “We’re here. We’ll get you out,” before moving on to the next person. Law got word that the big air ambulances were still being staged at Whakatane, so any immediate rescue was up to them. The most badly injured – by ballistics as well as scalding – were those nearest the crater. The Kahu team hopped one of the choppers further up into the threatening miasma to get them, loaded five people, and Hill took off for Whakatane Hospital. Below him, out of the steamy cauldron that had produced the lethal blast, the volcano suddenly started ashing.

By now, it was about 3.40pm, and Barrow was settling his helicopter onto a landing pad by the shore. He’d flown in from Rotorua with pilot Graeme Hopcroft. Funnell had updated them on conditions, and they raced up to the crater to join the search. They half-carried one survivor to their chopper, then joined the Kahu crew to assist five more survivors into Law’s machine. Law lifted up and out for Whakatane. Barrow, Hopcroft and Storey loaded one more survivor into the Volcanic Air helicopter, then Barrow and Hopcroft fired it up and banked south for Whakatane.

For a time, Storey was left alone. He spent the next half-hour grouping bodies for later retrieval. Among the bodies was his friend, White Island Tours guide Hayden Marshall-Inman. A second Volcanic Air helicopter arrived to pick up Storey, and completed an aerial reconnaissance of the crater.

By then it was all but over.

Two Westpac air-ambulance helicopters arrived, one circling on standby above the crater, while the second landed St John medical director Tony Smith and three other clinicians on the eerie domain below. They checked the bodies for signs of life, and confirmed no survivors were left behind.

The science behind the eruption

In geological terms, the steam-driven eruption on 9 December was a small one, similar in energy and range to the 27 April event three years earlier. One significant difference was that it happened more quickly.

Shane Cronin, professor of volcanology at the University of Auckland, compares the 9 December eruption to a giant pressure cooker blowing its lid. Whakaari’s “lid” consisted of layers of sulphur, salts and weakened rock, which were metres deep. These were blasted away to form an entirely new vent. When this lid blew, a pressure wave fled across the island at supersonic speed, invisible but forceful enough to knock gas masks off the faces of tourists and guides and to shift Volcanic Air’s 1.3 tonne Squirrel helicopter half off its landing pad.

Then an eruptive column of steam and ash climbed into the sky, perilous to any who stood close by.

But the most lethal event in the eruptive sequence was the third: a dense, ground-hugging pyroclastic surge, which flowed from the vent, over the walking track and right down to the eastern shoreline.

Cronin calculates from past studies of steam-driven eruptions on Whakaari that this surge would have burst from the crater at 300ºC and 100km/hour, losing force and heat in the ambient air as it rolled east. It was still boiling hot but had slowed to about 25km/hour when it flowed into the sea.

The surge was mainly formed of steam and ash, but carried within it a “salty aerosol”, says Cronin. Past testing of residues from this type of eruption has found them to consist mostly of fine fragments of pulverised rock coated in sulphur and acid salts, which turn into concentrated droplets of sulphuric acid when they come into contact with air, water or human skin. The remaining residues are hydrochloric acid and small amounts of hydrofluoric acid, which is the most corrosive of the residues, especially if inhaled.

Although the Squirrel helicopter was 1km away from the eruptive vent, its rotor blades flapped up and down like a bird’s wings in the turbulence of the pressure wave. Then the pyroclastic surge plastered it with ash. Afterwards, it sat stranded in the grey surrounds, grievously damaged, its carbon fibre and aluminium rotors broken and drooping, undone by nature’s power.

Calculating the devastation

The eruption had triggered a national emergency, and leadership had been formally handed to Bay of Plenty’s Civil Defence Emergency Management Group, with police the lead agency for search and rescue, and for recovery. The helicopter pilots had operated independently of the official system, but fell under its command once they landed and were stood down.

Eight bodies still lay on the island, two of them White Island Tours guides – Tipene Maangi and Hayden Marshall-Inman. As public pressure rose by the day to recover the Whakaari dead, Marshall-Inman became a symbol for all eight. The 40-year-old was well liked within the communities of Whakatane and Ohope, and he’d been with White Island Tours for many years.

A sense of frustration was growing in Whakatane, fuelled by outside control swooping in and sidelining local pilots, quarantining tour boats without properly cleaning them of corrosive ash, and suggesting – wrongly – that there was a criminal inquiry into White Island Tours. The town’s diffuse anger found focus on delays in the recovery.

But police were responsible for ensuring no further casualties, and the GNS Science seismometer on Whakaari was laying down a continuous recording of the volcano’s quivering energy.The volcano had erupted out of nowhere, and might do so again. In the hours after the eruption, the island was relatively quiet – and, in retrospect, this was the window for recovering the bodies.

Indications of unrest became more pronounced on Tuesday 10 December when the tremors began again, and on Wednesday and early Thursday the tremors peaked at levels well above the eruption itself. On Thursday evening, the tremors fell away sharply, and continued to fall on Friday, when the NZ Defence Force landed on the island at first light.

It was a team of eight, including six bomb disposal specialists, kitted out in three protective layers, with breathing apparatus and four hours’ worth of air. The work they did was exhausting. Around the active crater area, they waded through dense, hot, acidic mud, but they collected the bodies, and prepared them for final retrieval by helicopter to HMNZS Wellington , which was waiting offshore.

They recovered six bodies, but two had gone. Marshall-Inman and Winona Langford had been 800m away from the eruption, and 300m from the shoreline, but a violent rainstorm had swollen the stream near where they lay, and washed them into the sea. Police would later say that, while patrolling in Te Awapuia Bay, they’d seen a body believed to be Marshall-Inman near the landing, but couldn’t get close enough to recover it, and called in a Navy inflatable. In rebounding waves, the Navy personnel were unable to take the body aboard, and the rough sea allowed no second chance.

Resigned to the lack of any formal goodbye, the Inman family organised a celebration of life at the Whakatane Baptist Church on 20 December. Maangi’s photo was on display, too, and hundreds attended. The mourners heard from the helicopter-pilot rescuers that both Marshall-Inman and Maangi had tried to help members of their tour groups before they’d finally succumbed. Monday 9 December had been Marshall-Inman’s 1111th venture onto the island, and each one of them, except the last, had been recorded in his diary.

A few weeks later, Marshall-Inman’s brother Mark Inman and friends rode jet skis out to Whakaari, and sat on their craft in Te Awapuia Bay. After the long haul out to the island, the eight riders opened cans of beer and performed their own karakia – Maori incantations and prayers, used to invoke spiritual guidance and protection – to their friend and brother, and to all those who’d lost their lives.

The whaling captain, a secret plan and one of Australia’s boldest prison escapes

On 19 April 1876, a group of Irish Fenian prisoners who became known as the 'Fremantle Six' escaped from Australian authorities. However, the plan to secure their freedom began more than a year earlier and thousands of kilometres away.

Fishing for answers in Menindee Lakes

A New South Wales-first oxygenation trial aims to address dissolved oxygen levels in the Darling River that have contributed to large-scale fish deaths in recent years.

Ever heard of a moonbird?

The strong connection between King Island’s people and its moonbirds is celebrated by an arts festival bringing culture and conservation together.

Watch Latest Web Stories

Birds of Stewart Island / Rakiura

Endangered fairy-wrens survive Kimberley floods

Australia’s sleepiest species

2-FOR-1 GA TICKETS WITH OUTSIDE+

Don’t miss Thundercat, Fleet Foxes, and more at the Outside Festival.

GET TICKETS

BEST WEEK EVER

Try out unlimited access with 7 days of Outside+ for free.

Start Your Free Trial

The True Story of the White Island Eruption

Last December, around 100 tourists set out for New Zealand's Whakaari/White Island, where an active volcano has attracted hundreds of thousands of vacationers since the early 1990s. It was supposed to be a routine six-hour tour, including the highlight: a quick hike into the island's otherworldly caldera. Then the volcano exploded. What happened next reveals troubling questions about the risks we're willing to take when lives hang in the balance.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

Later, everyone who saw White Island erupt would remark on how quiet it was, how magnificent, and how swift. At 2:10 P.M., nothing. At 2:11, a two-mile-high tower of steam. Fifty miles away on New Zealand’s North Island, a search and rescue helicopter crew returning to base watched, astonished, as a colossal mushroom unfurled on the horizon. “Oh, my God!” shouted the pilot. “We’ve just seen a volcano erupt!” Then, a shudder of dread. It was December 9, the summer season. The island would be packed with day-trippers.

Just inland from the island’s rocky southern beach, with four middle-aged German clients he had brought in by chopper an hour earlier, pilot Brian Depauw glanced around to see a mammoth cumulus silently fill the sky behind him, then “go vertical.” Off the island’s east coast, on the Phoenix with a few dozen other tourists, Brazilian Allessandro Kauffmann captured the moment on video . The clip shows a vast ball of cloud roll out of the crater, then, soundlessly and impossibly fast, swallow the island. The initial eruption is followed moments later by a second blast, a dark gray avalanche that shoots out horizontally, directly toward the camera. The color and texture indicate a mix of rock, ash, and acid gas, a superheated pyroclastic flow. Its focused direction suggests that the crater amphitheater, with its high sides and single exit through a collapsed southern wall, has acted like a cannon: the explosion bounced off the caldera’s back and sides and is barrelling out the opening. The force of the wave is awesome. “Huge smoke coming very quickly … getting massive so fast,” was how Kauffmann’s wife, Aline, described it to reporters .

Paul Kingi, crewing on the Phoenix, saw the blast drop down onto the sea and hurtle toward his boat. As he yelled at everyone to get inside, the boat’s skipper gunned south, then made a wide curve around to the west and north, sidestepping the ash cloud like a matador executing a pass.

In Crater Bay on the Phoenix ’s sister ship, the Te Puia Whakaari , captain David Plews had no such chance. He was anchored in the path of a 60-mile-per-hour gas and rock tsunami. Already engulfed, or about to be, were his 42 passengers. Deep inside the crater, guide Hayden Marshall-Inman’s group of 21 had disappeared. Kelsey Waghorn’s group of 21, near the shore, were seconds from following them. Plews grabbed the ship’s radio. “Evacuate! Evacuate! Evacuate!” he shouted.

On land, Depauw heard the cries and saw what was about to happen. “Jump into the water!” he screamed at his guests. Depauw ran to the water’s edge and leapt. Two clients followed. The other two were unable to make the water in time. Depauw took a lungful of air as the black fog flew toward him. This is it , he thought. There’s no surviving this. Then he ducked.

When dawn had broken that day across the North Island’s north shore, before the light hit the beaches or the green mountains beyond, it caught White Island’s willowy plume, like a distant smoke signal, way out on the northern horizon. By the time Hayden Marshall-Inman arrived on Whakatane’s river-side quay to help prep the boat, the day was already sharp enough to give him a clear view across the Bay of Plenty, through the collapsed crater wall, and into the heart of the volcano. In his 40 years, Hayden had never tired of watching the steam shoot from the ground, puffing, balling, and rising into the wind before it drifted off across the water. The log he kept of his visits told him that this would be his 1,111th trip into New Zealand’s most active volcano , which followed 300 by his father, Alan, 69, a White Island Tours guide before him. When people asked, father and son always said: because it was never the same place twice.

The Marshall-Inmans shared their obsession with the Maori, to whom the island was a living ancestor, Whakaari , and the two dozen skippers, guides, and game-fish captains who drank at the Sportfishing Club, a few steps back from the wharf. Eight hundred years earlier, some of the first Maori to reach New Zealand from Polynesia came ashore at Whakatane. After James Cook’s arrival in 1769, the settlement became a town of shipbuilders, fishermen, and traders. By the 21st century, most of the men and women who still worked on the sea made their living taking some 20,000 tourists a year to the island.

The foundation of their business was an accident of nature that made White Island one of the world’s most accessible volcanos . With only a third of the cone above the ocean’s surface, and its fallen wall forming a giant natural drawbridge, all it took was 90 minutes in a boat or 20 in a helicopter and you were stepping off directly into the caldera. The place had a definite menace to it: the acrid air, the gas jets heated to 1,200 degrees, a lake at the bottom of an inner depression whose acidity was off the pH scale, and an abandoned sulfur mine from which ten men were swept away by a mud avalanche in 1914 , leaving only a cat named Peter as witness to their final moments. Claude Sarich, who worked the mine in the early 1930s, wrote : “The worst hell on earth, a place where rocks exploded in the intense heat, where … [clothes] just fell apart in a couple of hours, where [men] had to clean their teeth at least three times a day because their teeth went black.”

The mine closed in the 1930s, and for decades White Island was largely forgotten. But in the early 1990s, as adventure tourism took off, Whakatane’s sailors and pilots began offering day trips to this other world across the sea. The thousand-foot-high crater walls, the raw rockscape, the fine dust—the whole power and wonder of it—was as close as most would come to walking on the moon. Hayden’s brother, Mark, who proposed to his wife, Andy, in the crater, described it as “a thing of beauty.” Add in the chance to sail between three rock stacks said to be the gates to the Maori underworld and you had an experience that the guidebooks called unmissable.

In the weeks that followed the eruption, hundreds of columnists and radio hosts would take a different view: How crazy did you have to be, they would ask, to go walking around a live volcano, let alone run a business taking people there? The truth was: not crazy at all. Compared with climbing or jet-boating, or even swimming or driving a car , visiting a volcano was safe. A 2017 Journal of Applied Volcanology survey of every recorded volcano fatality for the past five centuries found that an average of one tourist, climber, camper, student, pilgrim, or park warden died every year on a volcano. Instead, like earthquakes and tsunamis, most volcano deaths occur among people who live in the area—the Journal counted 800 million residents within 60 miles of the world’s 1,508 active volcanoes, and reported that 216,035 had died in 517 years—though today, with early warnings and evacuation drills, years can pass without a single one of those, either.

White Island was also one of the world’s most closely observed craters, studded with webcams, seismometers, UV spectrometers, and survey pegs. The chemical makeup of its air and waters was regularly tested. The results fed into a frequent analysis by the geological monitoring service, GeoNet, which rated the alert level on a scale of 0 to 5. Limiting tours to levels 1 and 2, and granting skippers and pilots the prerogative to cancel a landing if they didn’t like the conditions, had helped ensure no fatalities in more than a century, even though White Island erupted continuously from 1975 to 2000.

Visiting White Island was about the thrill of feeling a little more alive by feeling a little closer to death, all the while knowing that, really, you were in no more danger than you would be crossing a road.

That spotless record partly reflected the tameness of the tours. If New Zealand’s adventure industry often seemed like a marriage of the outdoors and mad science—seeing what happened, say, if you leapt off a bridge with a rubber band tied to your ankles—a walk around White Island was one of its gentler offerings. The crater was two-thirds of a mile in diameter; the walk covered about half that. The established route started at a jetty on the island’s southern shore and climbed leisurely up a dirt track through the collapsed crater wall, skirting bubbling mud puddles and steaming fumaroles before reaching the rim of the inner depression, from where visitors could gaze down at the acid lake. After that, it was a 30-minute stroll back past the old sulfur factory to the jetty. Tourists aged eight to eighty, wearing hard hats and carrying gas masks, had no trouble completing the trail in an hour and a half.

If White Island Tours was guilty of anything, it was of hamming up the risk. A leaflet from 2006 was headlined: “Volcano. Handle With Scare!” Guides liked to warn visitors that an eruption could happen at any moment, and that anybody caught in one could expect to be hit by rocks, scalded by steam, and enveloped in an acid mist as the crater lake flash-vaporized. Alan Marshall-Inman would have his groups dip their fingers in the coppery streams and ask them if they tasted blood. Hayden would tell the story of an ash eruption during a visit in September 2017. “We were walking into it,” he told a travel program in July 2018. “I could definitely feel the nerves inside me for sure.”

That was the whole idea of visiting White Island. It was about the thrill of feeling a little more alive by feeling a little closer to death, all the while knowing that, really, you were in no more danger than you would be crossing a road.

By early December, it was peak season on the island, and the volcano seemed to be cooperating. On November 19 , GeoNet had raised the alert from 1 to 2, but a week later it had clarified that despite “a few earthquakes,” “high to moderate” gas emissions, and the possibility that the volcano was “entering a period where eruptive activity is more likely than normal,” it did not consider the new mud fountains in the crater to be a hazard to visitors and that, overall, the island was in a state of “moderate volcanic unrest.”

With that assessment, the volcano would be crowded. White Island Tours, where Hayden was a skipper, had around 100 passengers booked, requiring three of its four boats. Also heading out were two small helicopters from Volcanic Air, flying visitors from Rotorua, up in the hills.

With White Island Tours’ fleet of cruisers, and the helicopters making up to three trips a day, skippers and pilots coordinated their arrivals to avoid swamping the island. That collegial spirit was apparent, too, in the consideration shown to Brian Depauw, a young airman who had returned to New Zealand after two years flying tourists over Victoria Falls in Zambia. Though Depauw was working for Volcanic, he had trained at Kahu, the other helicopter outfit flying to White Island, run by a towering former special-forces soldier with a boxer’s nose named Mark Law. In any other town, Depauw’s switch might have rankled Law, just as Law might have seen his operation as a rival to White Island Tours. But in Whakatane, Law described Depauw and Volcanic boss Tim Barrow as “mates,” while Law’s children were best friends with Hayden’s niece and nephew—Andy and Mark’s kids—and he and Hayden were regulars at the town rugby park, where they could be found cheering on their boys.

That was the kind of place Whakatane was. A town of some 17,000, without a traffic light, whose street of tourist cafés and restaurants might die down in winter, but that, year-round, had its own clubs for rowing and cricket, croquet and table tennis, even skeet shooting and petanque, its own theater and newspaper, the Beacon , its own airport, university, and hospital, a cardboard mill, two boat builders, and three rescue services—fire, ambulance, and coast guard—all staffed, in part, by volunteers. In Whakatane, people pitched in. The town mayor, Judy Turner, doubled as a funeral celebrant. Another of Kahu’s pilots was Tom Storey, an easygoing 29-year-old with hazel eyes who, when he wasn’t flying or hunting deer or wild boar, ran Back Country Builders, erecting beach houses. The way people juggled roles in Whakatane said something about small towns. But it said as much about New Zealand, a nation built by men and women who had crossed thousands of miles by canoe and ship, and referred to themselves as “number-eight wire” types—the sort who could tame a land and fix just about anything with a coil of fencing line.

That sense of community enterprise animated White Island Tours. Whakatane’s biggest Maori tribe, the Ngati Awa, bought the operation in 2017 using money from a state program designed to compensate for the colonial theft of their land. There were a few grumbles about that in Whakatane among pakeha , the name Maori gave the descendants of European settlers, a minority of whom still saw Maoris’ poor showing in health, education, and crime as evidence of a natural order. But in a town that was 43.5 percent Maori , most considered racism not just unpleasant but impractical, something that got in the way of getting on. They approved of how the Ngati Awa used White Island Tours’ profits to fund social programs to lift their people, historically some of the poorest in New Zealand. They were proud, too, of how such initiatives explained why New Zealand’s national experiment was held up as an example to Australia, South Africa, and even the U.S.

To its mixed-race staff of 60, and especially to Hayden, White Island Tours was a second family. Ten years earlier, boat manager Paul Kingi had taken on “Hayds” over a handshake when he was a beach bum with few ambitions beyond watching the Chiefs, the rugby team he worshipped, and pursuing an endless summer from Whakatane to Maine, where he worked in YMCA camps. Hayden became Kingi’s “pet project,” said Rick Pollock, 72, a retired Whakatane charter captain who had employed Hayden and Kingi as deckhands. Though Hayden struggled at first with the seven different talks on safety, history, and geology that a guide had to master, he looked the part with his seaman’s build and pirate’s sideburns, and he had such a way with passengers that Kingi came to see him as one of his best assets, promoting him from guide to skipper. “He used to talk to everybody,” Kingi said later. “He wanted to know their life story—he used to get around and make sure he spoke to everybody on that boat.” In 2016, when an engine fire engulfed the Peejay V as it returned from White Island, it was Hayden who guided everyone to safety, making sure he was among the last off. Pollock said of his former crew member: “He would help anybody. That’s who he was.”

The Maori way of looking at Hayden, and Whakatane, was that they lived by tikanga. The word described a good heart, a true soul, a deep, spiritual instinct for doing what was right, rooted in centuries of listening to the world and accepting your place in it. People who followed tikanga knew what to do and did it without thinking. Tikanga was why, when Kingi called for extra hands to crew a third boat for 38 passengers of a cruise liner that had just docked down the coast, Hayden offered to take a day’s demotion from skipper to guide to accommodate the additional clients. It was also why, a day later, in the face of extraordinary danger, and in defiance of an order to rescue crews to remain on the mainland, so many Whakatane men and women would risk everything to try to save them.

Kingi staggered his three boats’ departures. The Peejay IV left at around 9:30 A.M. The Phoenix followed at 10:30, with Kingi helping out as crew. Last to leave, at around 11:30, was the season’s new addition, the Te Puia Whakaari , a catamaran with a cruising speed of 30 knots . At the wheel was David Plews, a White Island veteran with eyes the hue of sea ice, who, at the helm of the Peejay V during the 2016 fire, had calmly anchored the blazing boat at a spot off Whakatane Heads where it could sink without obstructing the harbor.

Assisting Plews on his new boat were four guides. Kelsey Waghorn, 25, a marine biologist with a cascade of mousey brown curls and a rescue dog called River, would lead the first group of 19 passengers. She would be backed up by Jake Milbank, celebrating his 19th birthday that day, whose elfin blond hair framed his delicate features. Hayden would take the second group of 19. His assistant would be Tipene Maangi, a personable 24-year-old with a deep knowledge of Maori myths and two months on the job.

The guides chatted with the passengers as they were welcomed aboard. Their liner, the Ovation of the Seas , had sailed from Sydney on December 4, and 24 of them were Australian, mostly families and middle-aged couples. The rest included nine Americans, two Chinese women, two British women, and a Malaysian man.

After an uneventful crossing, Plews anchored the Te Puia Whakaari in Crater Bay around 1 P.M. and began running his passengers ashore. An hour later, the number of tourists on the island had peaked. The Peejay IV was already heading back to Whakatane with its few dozen passengers. A similar number from the Phoenix had completed their walk and, back on board, were cruising northeast for one last photo opportunity. The two small parties flown in by Volcanic were also close to leaving. The first chopper departed at 2:05. Ten minutes behind were Brian Depauw and his four guests, who would soon board their chopper for the flight back to Rotorua.

Last to leave would be the 38 passengers and four guides from the Te Puia Whakaari. At two o’clock, Waghorn’s group were already near the abandoned sulfur factory and would soon reach the jetty where Plews would pick them up. Hayden’s group—one Australian-American family of four and 15 other Australians, including a family of four, two families of three, a trio of friends in their thirties, and a mother and daughter—were at the lip of the inner crater looking down on the lake.

At 2:10, a GeoNet camera taking pictures at ten-minute intervals caught an image of Hayden’s group in the distance. They have left the inner rim and are walking in single file back down a gentle slope, heading for the jetty. Though the image isn’t sharp enough to identify individuals, it shows body shapes. The walkers look relaxed. Their arms appear to be swinging, their postures indicate an ambling pace, and their loose grouping suggests no urgency. Some figures are half-turned, seemingly in conversation. One looks to be to be pointing out a rock formation.

For all but three, it was the last picture of them alive.

Trauma surgeons talk about a “golden hour” within which to begin treating injuries. A volcanic eruption means burns, and with those, time is especially pressing. Even the most severely injured can sometimes walk and talk immediately after exposure. But as the seconds pass, their skin swells and blisters, even peels right off, while those who have inhaled toxic gas find their breathing ever more restricted. The difference between life and death can be minutes.

On December 9, the initial response was fast. Several skippers out at sea saw the eruption and called it in. Whakatane’s coast guard reported minutes later that White Island Tours had three boats out with around 100 people aboard. At that, dispatchers scrambled 11 search and rescue choppers on the North Island. The SAR crew who had seen White Island erupt were based 20 minutes away at Tauranga and in position to be first on the scene. Following would be two AW 169’s from Auckland Rescue Helicopter Trust, which could fly at 190 miles per hour and, with the golden hour in mind, were fitted out as flying emergency rooms. Whereas it used to be “half an hour to get there, half an hour to get them to hospital,” said spokesman Lincoln Davies, “we can treat them straight away.”

When the national air desk issued the crews their dispatch orders, however, there was a shock. No one would be flying to White Island. Instead, the crews were told that they would receive casualties at Whakatane, then transport them to burn units across the country. The order must have struck the crews as illogical—if the rescuers weren’t doing any rescuing, how would there be any casualties to transfer?—but when they double-checked, the word came back: stay away from White Island. “Much higher-ups said: ‘It’s an active volcano which is erupting, and you have to consider whether you’re putting crews’ lives in danger,’ ” said Sharni Weir, spokeswoman for Philips Search and Rescue Trust, which operates four choppers. “We would want to go to White Island, [but] air desk said: ‘No, you’re all to go to Whakatane.’ And we all went there.”

Underwater, Depauw saw a dark wave roll across the surface, then everything go black. After what he thought was two minutes, the light began to return and Depauw, his lungs aching, burst up into the air. The water around him was slicked with a dirty yellow dust that stank of sulfur. But behind the blast wave, the air was beginning to clear.

Out in the bay, the Te Puia Whakaari was coated in matte gray ash. The beach, which had been a mosaic of colorful rocks, was buried under drifts of Chernobyl-like dust. In the crater, Depauw’s helicopter had taken the full force of the blast. Caked in ash, its 1.5-ton weight had been knocked off its landing platform, and the blast had left two of its rotor blades folded at right angles to the ground like giant spider legs. Depauw checked his passengers. The two with him in the water seemed unhurt, though it later transpired that the woman had suffered burns to her arm. He was less sure about the other two, who were now gathering with Waghorn’s group on the jetty.

As Depauw swam in, the Phoenix sped into the bay. While the boat anchored, Kingi launched a tender and raced to the jetty. Michael Schade, a tech manager from San Francisco, filmed the scene . The passengers look unhurried. One woman whose appearance matches that of Ivy Kohn Reed, 51, from Gaithersburg, Maryland, north of Washington, D.C., has her hands on her hips, waiting patiently to board. A man is sitting down on the jetty, almost as though he’s resting on a hot day.

Only a closer look reveals anything amiss. The group’s clothing is muted gray with ash. The legs of one woman sitting on the jetty, inching herself forward, appear blackened. On board Kingi’s tender, Waghorn is covered in ash and moving unsteadily. Jake Milbank is also coated and lying in the bows, staring up at the sky.

At 2:24, Schade took a still of Kingi ferrying passengers to the Phoenix. Kingi is grim faced, hunched over the wheel. His passengers crouch forward. One woman, probably newlywed Lauren Urey, 32, from Richmond, Virginia, is covered in ash. A gray arm, likely belonging to her husband, Matt, 36, is hugging her. In the bows, a guide from the Phoenix supports a woman with her right hand while her left arm hugs Milbank, who appears to have collapsed.

In a handful of runs, Kingi and his crew picked up all 19 passengers from Waghorn’s group, their two guides, plus Depauw and his four clients. As the Phoenix ’s skipper set off for Whakatane, Kingi switched boats to the Te Puia Whakaari , saying that he would make a final sweep of the shore. Heading deeper into the crater, Kingi was astonished to see a figure stumble out of the ash. Jesse Langford , 19, who had been with Hayden’s group inside the caldera with his father Anthony, 51, mother Kristine, 45, and sister Winona, 17, had somehow made it down to the shore. Kingi was even more stunned when he saw Langford’s injuries. No part of him was untouched. His hair, face, chest, arms, hands, legs, and feet were all burned.

Carefully, Kingi assisted the teenager into the tender and raced him over to the Te Puia Whakaari. Plews raised anchor, opened the throttle, and roared off for Whakatane. With word that the Peejay IV was returning to the island after disembarking its uninjured passengers, Kingi elected to stay behind and continue to search.

Unusual for peak season, there were no Kahu helicopters flying that day. Tom Storey was doing foundation work on a new beach house. Mark Law had been at a mountain-bike competition on the South Island that weekend and was driving the coast road back to Whakatane when he saw a massive, sinister-looking column of smoke appear on the horizon.

Law called the Kahu office. Within minutes, they called back to say that GeoNet’s island webcams had been knocked out and the White Island boats at the volcano weren’t responding. Law asked the office to call Storey and another pilot, Jason Hill. Then he phoned Tim Barrow. The Volcanic boss said that one of his choppers had made a narrow escape but another, flown by Depauw, was on the island when it erupted.

Next, John Funnell called. Funnell, 69, was a pioneer of New Zealand’s search and rescue service who lived in Taupo, in the hills. He had been teaching instrument approaches to a student at Whakatane airstrip when he saw the eruption. He landed, dropped off his student, and headed to the island. Because rescue crews inside the steep-sided crater would be cut off from all communication except what they could pick up on short-range handheld radios, Funnell told Law that he would circle the island and provide overhead radio cover, juggling his VHF radio and a cell phone to relay messages from the police and coast guard.

Arriving at Kahu’s hangar, Law called Barrow again. The men agreed: with Funnell in place, rescue crews expected to be converging on an island the two of them knew better than anyone, and word filtering through that Hayden might have been out there when it blew, they needed to get in the air.

At 2:50, Jason Hill took off with Tom Storey as copilot. Flying solo, Law followed a few minutes later. At 3:05, Barrow and copilot Graeme Hopcroft lifted off from Rotorua.

Speeding back to Whakatane, the Phoenix was now a hospital ship. Nearly an hour after the eruption, passengers who had been able to walk aboard were now moaning and screaming as their burns swelled and blistered. Tongues were puffing. Throats were closing. “You’d lift someone’s shirt and the shirt was in perfect condition, but there would be terrible burns underneath it,” Geoff Hopkins, on a tour with his daughter, told Radio New Zealand . Initially, he, Depauw, and other passengers had poured bottled water on the burns. Now many of the injured were going into shock. Some couldn’t tolerate wind or sunlight. Others shivered uncontrollably. Hopkins told Good Morning Britain that he found himself comforting Lauren and Matt Urey, who were slipping in and out of consciousness. “I don’t think I’m going to make it,” Lauren would say. “You can!” Hopkins would insist. “You’re a fighter! There’s more for you. It’s not going to end today.”

Approaching the Phoenix from the air, Storey and Hill saw passengers on deck performing CPR. As the pair attempted to airlift the worst injured, Mark Law shot past. A few minutes later, with Hill still hovering, Law learned that a coast guard boat from Whakatane with two paramedics on board was approaching the Phoenix. He told Hill and Storey to leave the boat to the coast guard. He needed them on the island.

Passing over the crater, Law had spotted more than a dozen people in a loose grouping on the crater floor a couple hundred yards below the inner depression. Some were sitting. Some were “starfished.” At 3:12, an hour and a minute after the eruption, Law touched down on a landing platform. Hill and Storey followed. The acid in the air would be ruinous to their choppers. But “the most important thing was we went and cared for those folks who were alive, dying, and dead,” Law said.

Strapping on gas masks, Law, Hill, and Storey ran the few hundred yards up into the crater through shin-deep drifts of hot ash. Once they reached the group, the three men hurried from person to person, checking their injuries and reassuring them that help was coming. Their burns were gruesome. “They were black,” said Law. “Anything exposed was burned.” Law had tended badly wounded soldiers in combat. “Nothing more important in that situation than to hear someone arrive and take care of you when you are in such an agonizing, confused, painful, lost state,” he said. Some of the group were unresponsive, possibly dead. Most were alive, if dazed and incoherent. “People were groaning and asking for water,” Storey said.

All 20 people that the pilots found were below the rim of the inner crater, forming a loose line along the path. Many of their burns were so severe that later, when the pilots saw pictures of the dead and missing on the news, they didn’t recognise them. One adult was so disfigured it was impossible to tell if they were a man or a woman. But from police press releases, the pilots’ descriptions, and confirmation from New Zealand police, the 20 were:

Martin Hollander, 48, and his U.S.-born wife, Barbara, 49, from Sydney, and their boys, Berend, 16, and Matthew, 13; Gavin and Lisa Dallow, 53 and 48, from Adelaide, and their daughter, Zoe Hosking, 15; Kristine and Anthony Langford, 45 and 51, from Sydney, and their daughter Winona, 17; Paul Browitt, from Melbourne, and his daughters Stephanie, 23, and Krystal, 21; Julie Richards, 47, from Brisbane, and her daughter, Jessica, 20; Richard Elzer, 32, and Karla Mathews, 32—boyfriend and girlfriend—and their friend Jason Griffiths, 33, all from the eastern Australian town of Coffs Harbour; Hayden Marshall-Inman and Tipene Maangi, both guides.

At first, when Storey came across two young women, Krystal Browitt and either Jessica Richards or Zoe Hosking, lying unconscious next to each other, he thought they were dead, but feeling for a pulse, he found one on both. A few yards downhill, lying next to a stream, Tipene Maangi was showing no signs of life. Fifty yards away, one of the Hollander boys was breathing. Looking for Hayden, Law followed a set of footprints in the ash leading away from the main group, past Maangi, toward the sea. His friend was 40 yards on, lying by the same stream, unresponsive. Winona Langford was nearby. She also wasn’t moving.

As the three pilots worked, they were able to piece together some of what had happened. From where they were, the walkers would have seen the initial eruption. Behind a boulder, Storey and Law came across a small pile of phones and tablets; video from them would later confirm that several had stopped to film the steam cloud. What none of them could have seen, until it crested the lip and consumed them, was the horizontal blast of rock, ash, and acid mist. Many injuries were to their anterior sides, suggesting that they were facing it when it hit. Superintendent Andy McGregor, police district commander for the Bay of Plenty, said: “In the ash was hydrochloride, hydrofluoride, and sulfur dioxide. Mix those with water and you get hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid, [which] attacks calcium, and sulfuric acid. So you’ve got superheated gases, you’ve got the blast, and you’ve got the acid atmosphere. Imagine what that does.” The pilots didn’t have to. Along with the burns, they found evidence of the eruption’s force. Law noted numerous shrapnel injuries and signs of internal damage. Storey came across one man with part of his head missing.

Amid the carnage were signs of courage and sacrifice. A guide’s medical kit sitting among the group was probably carried there by Hayden or Maangi after the blast. Many of the injured were wearing gas masks that looked to have been placed on them after they’d lost consciousness. In Maangi’s outstretched hand was an asthma inhaler, as though he was passing it to someone when he succumbed. The footprints described almost unbelievable heroism. Atop the ash, they had to have been made after the eruption and seemed to indicate that Hayden had backtracked and tried to lead his group away from the crater, toward the ocean. The position of his body, Maangi’s, and Winona’s suggested that, in the darkness of the ash cloud, they were following the stream downhill. None of them made it. But Winona’s elder brother, Jesse, had run all the way to the jetty.

As they processed what they were seeing, the pilots steeled themselves with the thought that they had arrived in time. Most of the injured were hanging on, if barely. The pilots understood that rescue crews were en route. “I think they were only about four or five miles away,” Storey said.

Then, sometime between 3:25 and 3:30, Funnell came back on the radio. The rescuers had been ordered to Whakatane. No help was coming. The pilots were on their own.

One of the cornerstones of New Zealand’s adventure-tourism industry is a 1972 law effectively banning personal-injury lawsuits. In their place, the government set up a mandatory compensation policy under which it would foot all bills for the dead and injured. It was an unusual legal innovation and a typically Kiwi one: New Zealanders didn’t sue for damages, they fixed them.

A generation later, New Zealand was the adventure capital of the world. But the deaths of 37 tourists between 2006 and 2009 led to concerns over public safety, which intensified when 29 miners were killed in a methane explosion at the Pike River coal mine on the South Island in November 2010, and again in February 2011, when an earthquake in Christchurch, the largest city on New Zealand’s South Island, killed 185 people. The result, in 2013, was a stringent new set of health and safety regulations , policed by a new government agency, Worksafe, with the power to impose million-dollar fines and imprison offenders for up to five years. New Zealand’s adventure operators were required to obtain Worksafe certification and submit to regular inspections.

With its impeccable record and easy crater walks, White Island Tours wasn’t much affected by the new dispensation. When a 73-year-old fell to his death on a guided walk around the neighboring island of Moutohora in April 2019, Worksafe cleared the company of blame. Two months before the eruption , a Worksafe inspector who’d joined a tour of White Island reportedly raised no concerns.

But Pike River had another legacy. Alarm about working conditions was quickly replaced by public outrage over a refusal by police commanders to send search and rescue teams into the mine on the grounds that it was unsafe. The police weren’t wrong to be concerned: in the nine days that followed the disaster, there were three more methane explosions. Still, two men walked out of the mine shortly after the blast, and the idea that rescue professionals, whose job it was to head into danger to save lives, might be held back by health and safety rules offended what New Zealanders like to call the Kiwi way. In 2012, an independent inquiry criticized the emergency response as “cumbersome” and said it was wrong to assign command to senior police officers in the capital, Wellington, who would have no idea of the reality on the ground. But the unease generated by Pike River endured. Despite more inquiries and election pledges, the miners’ 29 bodies remain unrecovered .

The lesson of Pike River was that disaster response needed quick, informed decision-making, and this required rescuers on the ground assessing their own risks and making their own calls. Instead of heeding it, however, the central government responded as central governments are bound to: with more regulation. In the wake of the disaster, New Zealand’s rescuers found themselves subject to ever tighter rules on workplace safety. The July 2018 New Zealand Aeromedical and Air Rescue Standard , a revised version of guidelines already updated in 2015 and 2012, required operators to ensure they were “recognising and minimising the risk of threat and error,” and crews to “operate within a risk management system that maximises aviation safety.” Rescues would “never be to the detriment of flight safety.” The first criterion for judging whether a crew was fit to deploy was their ability to provide “safe and effective support of the operation of the aircraft in the prevailing and forecast conditions.” An ability to give “appropriate clinical support for the person(s) in distress” was merely the fifth criterion. In 59 pages of guidelines, just one, page 48, concerned patient safety.

After observing the rescue crews arrive and cut their engines outside the Kahu hangar, Mark Law suspected they might be a no-show on the island. When official confirmation came, his decision was immediate. “As soon as Mark heard that they had been retasked to Whakatane, he said we would be taking the victims out,” Storey said.

As Hill ran back to fetch his helicopter and fly it up into the crater, Law and Storey began picking up casualties. Among the first to be loaded was Lisa Dallow, who they knew was alive since, after asking Storey for water, she started throwing up blood and ash. Next, Storey approached Paul Browitt, who was sitting up. “Afterward,” the tax inspector croaked. “Grab my daughter first. She’s in the blue.” Storey ran over to Stephanie, in a blue Adidas top, and carried her to the chopper. He then went back for her father. After that, Law and Storey hauled over a male casualty, then the man with the head wound. With his maximum load of five casualties on board, Hill departed for Whakatane at 3:48.

As Law ran to fetch his chopper, Storey readied the next five casualties. The urgency of their situation was suddenly apparent. People were dying all around him. Maangi was long gone. When Storey returned to the two young women, neither had a pulse. Uphill, Richard Elzer and Karla Mathews had died lying next to each other. Alongside them was another lifeless body, likely Julie Richards. Hayden and Winona Langford hadn’t stirred. A young woman—from Storey’s description, probably Zoe Hosking, 15—was still breathing when he picked her up and as he carried her to the chopper. “She was holding on to me,” he said. “Then she went all limp.” Reaching Law, he nodded at the body in his arms. “I think she’s gone,” he said. Law said to load her anyway.

While Storey and Law lifted more casualties aboard, Tim Barrow and Graeme Hopcroft touched down below. Over the radio, Law directed Barrow to the lower Hollander boy. He, too, was now in a bad way, said Barrow. “Not capable of communicating,” the Volcanic boss told Radio New Zealand . “Just asking for water.” Barrow and Hopcroft managed to walk the boy to their helicopter, then helped Storey and Law load Law’s next five casualties, after which the ex-special-forces pilot took off for Whakatane. Barrow then flew his helicopter into the crater and picked up the final casualty that Storey could identify as alive. Barrow and Hopcroft left shortly afterward. By then, 4:07, Jason Hill was touching down on the mainland and the Phoenix was arriving at Whakatane wharf.

Deep inside the crater, guide Hayden Marshall-Inman’s group of 21 had disappeared. Kelsey Waghorn’s group of 21, near the shore, were seconds from following them. Plews grabbed the ship’s radio. “Evacuate! Evacuate! Evacuate!”

In all, the pilots picked up 12 people in 40 minutes. Beyond help and still on the island were eight more casualties. Imagining that his friends would soon be returning for the bodies, Storey began moving them together to make extraction easier. He put Elzer, Mathews, and the third casualty beside each other in the recovery position. He did the same for the two young women. He dragged Maangi out of the stream. Following Law’s and Hayden’s footsteps, he heaved Hayden out of the water and sat him upright on a bank. To reach Winona Langford, on the far bank across a deep ash field, Storey followed the stream downhill, found a crossing, and walked back up the other side.

Everywhere he went, Storey found phones, which he tucked in their owners’ hands as a way to identify them. He noted which bodies were wearing Ovation of the Seas identification tags. When Funnell alerted him to the arrival of a fourth Volcanic crew and, finally, a rescue chopper, Storey walked down to the beach to meet them.

Storey described his tour of the crater. There was no one left, he said. It would be four days before a military squad in hazmat suits recovered the bodies.

In Whakatane, as soon as the Kahu and Volcanic pilots returned, the police ordered them to stand down. Superintendent McGregor later said that what the pilots had achieved was “fantastic.” But he added: “It’s a police decision for their own safety. They came back and said there is no one left. And we said: ‘We can look to recover bodies later.’ ”

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern flew in and met the pilots just after the eruption. At a press conference , she acknowledged “those pilots who … made an incredibly brave decision under extraordinarily dangerous circumstances in an attempt to get people out.” By then, however, Law, Storey, Barrow, and Hill were telling reporters that the authorities were being too cautious. The families needed to bury their loved ones. Conditions were perfect. Law said that he and the others could fly to the island, pick up all eight bodies, and be back in an hour and a half.

In fact, the opportunity to retrieve all the bodies had passed. A heavy rainstorm had hit the island overnight, and an ash mudslide that the police estimated at five feet deep washed down the streambed and swept Hayden’s and Winona Langford’s bodies out to sea. On December 11, navy divers found Hayden’s corpse lying on the seabed and brought him to the surface. But when they took their boat into deeper water to transfer him to a police launch, they dropped his body in a heavy swell and it sank in hundreds of feet of water. Two days later, December 13, an army team took about three hours to recover the six remaining bodies . The search for Hayden and Winona was finally called off on Christmas Eve.

Of the 47 people on White Island at the time of the eruption, 21 died and 24 were injured. Of the 12 flown out by Hill, Law, and Barrow, 10 died. Paul Browitt , who had insisted that his daughter Stephanie be rescued before him, clung to life for more than a month but finally passed away in a hospital in Melbourne on January 13, bringing to 18 the number from Hayden’s group of 21 who perished. The dead from Waghorn’s group included Chris Cozad , a 43-year-old father of three from Sydney, who died on December 14, and Mayuri Singh and her husband, Pratap , from outside Atlanta, who died, respectively, on December 22 and January 28.

The survivors required so many skin grafts that New Zealand put out a global order for 33.8 square meters , the equivalent of 16 bodies’ worth. By mid-February, Lisa Dallow was described as critical but stable in Melbourne. At the same hospital, Stephanie Browitt, 23, was expected to recover after spending weeks in an induced coma; her mother, Marie, who’d remained on the Ovation while her husband and two daughters went to White Island, had barely left her side . Rick and Ivy Kohn Reed , and Matt and Lauren Urey, returned to the U.S. After 25 operations to treat burns covering 80 percent of his body, Jake Milbank wrote his thanks to supporters, who’d raised $87,700 to pay for his treatment. Kelsey Waghorn , who underwent 14 surgeries of her own for her 45 percent burns, wrote to donors who had raised $68,580 for her: “I’ll just keep pushing forward and hope that that will do for now.”

The most extraordinary survival story belonged to Jesse Langford. Despite suffering burns over 90 percent of his body during his run through the crater, by December 30, the 19-year-old was able to write a eulogy for his father, mother, and sister. From his hospital bed in Sydney, he watched a livestream of their funeral, at which his words were read out. The past weeks “have taught me that when times are tough, you have to find that inner strength that pushes you to persevere,” he wrote . “You always have a bit more in you.”

Final analysis of the eruption is months away and may never be definitive. Still, New Zealand volcanologists are confident they know what happened. The eruption was most likely phreatomagmatic, combining steam and magma. It would have begun with a magma rise from a fault movement deep in the earth, which was then given more upward force by gases exsolving out of the liquid as it rose and depressurized, an effect that Tom Wilson, professor of disaster risk and resilience at the University of Canterbury, likened to opening a soda bottle. When the magma hit the acid crater lake, or seawater and rainwater percolating down, or both, the water would have been flashed into gas and the molten rock into glass. Both of those processes would have released enough explosive energy to shoot steam 12,000 feet into the air and blow a deadly wave of hot rock, ash, and acid gas across the crater floor.

Given the loss of life, Wilson said that more important than plotting the eruption’s precise cause was reckoning with its unpredictability. None of its various elements were detectable, he said, for the simple reason that on the scale of volcanic eruptions, December 9 was “really small.” Better science could help, but what was really needed was a “calm, measured, analytical” conversation about adventure tourism and acceptable risk, and an understanding that there were no easy answers. “We absolutely don’t tolerate 21 people dying in an event on White Island,” he said. Then again, “the whole point of adventure tourism is to have a bit of fun, a bit of risk, and for it to be exciting—and there is going to be risk and the potential for injuries and loss of life to occur.”

Under investigation by the coroner and Worksafe, White Island Tours must wait to hear whether it will be fined or prosecuted, or its business outlawed. The consensus in Whakatane is that landings on the island will be restricted and perhaps banned altogether.

So far, however, there has been no move to reexamine a set of health and safety regulations that, whatever their original intent, prevent rescue crews in New Zealand from doing their jobs. Of Hayden’s group, “no one would have lived if we hadn’t gone when we did,” said Law. If Kingi and the crew of the Phoenix hadn’t acted, two dozen more might have died. The irony, and tragedy, is that the order to bar rescuers from flying to White Island, where people were dying, was expressed in terms of public safety.

Asked why they’d stopped rescue crews from flying to White Island immediately after the 2:11 eruption, a spokesperson for the national air desk declined to comment. Asked why emergency crews were kept away, a spokesperson for the police, which had overall command of the operation, replied with a written statement saying, “There were no signs of life … conditions on the island were unstable and there was significant risk in landing. The difficult decision was made to pull back any deployed aircraft making rescue attempts to prevent further loss of life.”

The statement, which avoids addressing the absence of rescuers in the critical period after the eruption, seemed intended to obscure the central issue—how, in playing it by the book, the authorities blew the golden hour. Because there was time. The flight from the North Island to White Island takes 20 minutes. Five pilots in three helicopters picked up 12 casualties in 40 minutes. “The reality of the situation that day,” Law said, “is it was all about volunteers taking care of the needs of many, while emergency services reacted to the needs of compliance and personal safety.” The authorities, he said, were “on a completely different page than us.”