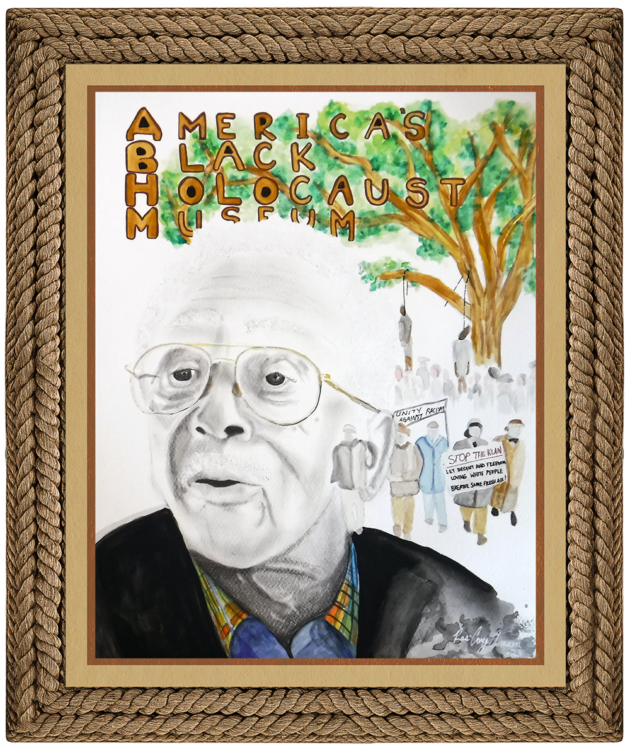

America's Black Holocaust Museum

Bringing Our History to Light

An old Virginia plantation, a new owner and a family legacy unveiled

More breaking news.

Pacers’ star Tyrese Haliburton says rival fan directed racist slur at his brother during playoff game

Beyoncé Showed Her Hair Being Washed. Here’s Why It Matters.

Stephen A. Smith’s Non-Apology ‘Apology’

Black Amputation Rates Are High. Knowing Your Risk Can Lower It.

Duke University Ends Scholarship Program for Black Students: Why You Should Care

Supreme Court Seems Poised to Allow Local Laws That Penalize Homelessness

Mandisa, Grammy-winning singer and ‘American Idol’ alum, dies at 47

A Photographer in Search of Forgotten Burial Sites

Explore Our Galleries

African Peoples Before Captivity

Kidnapped: The Middle Passage

Nearly Three Centuries Of Enslavement

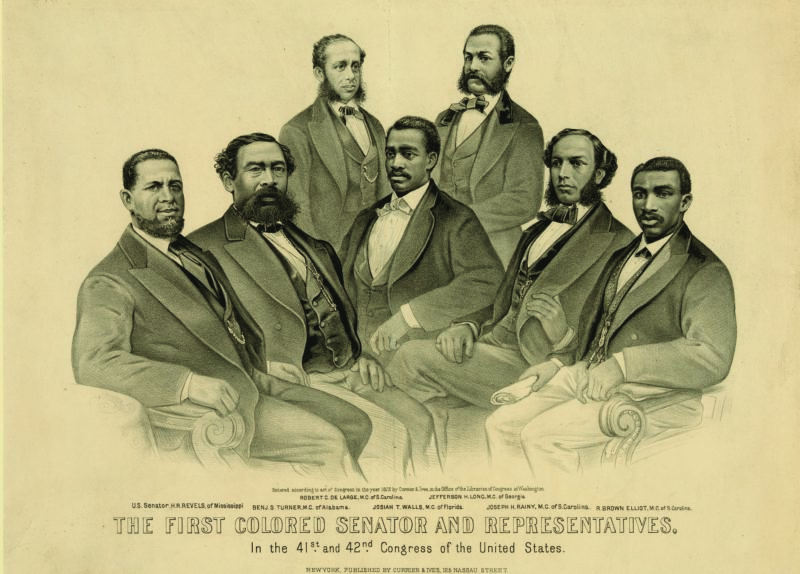

Reconstruction: A Brief Glimpse of Freedom

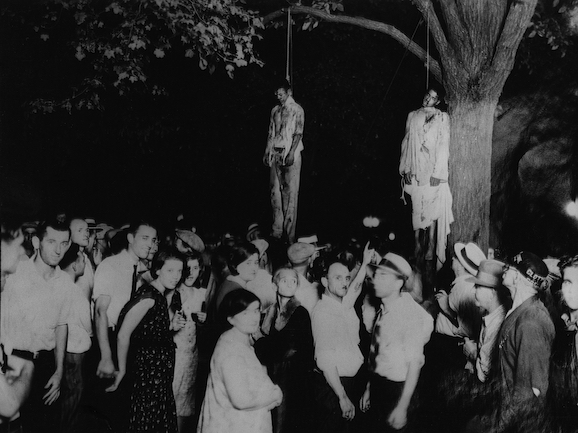

One Hundred Years of Jim Crow

I Am Somebody! The Struggle for Justice

NOW: Free At Last?

Memorial to the Victims of Lynching

The Freedom-Lovers’ Roll Call Wall

Special Exhibits

Portraiture of Resistance

Breaking news.

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Joe Heim, The Washington Post

GRETNA, Va. — There was so much Fredrick Miller didn’t know about the handsome house here on Riceville Road.

He grew up just a half-mile away and rode past it on his school bus every day. It was hard to miss. The home’s Gothic revival gables, six chimneys, diamond-paned windows and sweeping lawn were as distinctive a sight as was to be seen in this rural southern Virginia community. But Miller, 56, an Air Force veteran who now lives in California, didn’t give it much thought. He didn’t know it had once been a plantation or that 58 people had once been enslaved there. He never considered that its past had anything to do with him.

Two years ago, when his sister called to say the estate was for sale, he jumped on it. He’d been looking, pulled home to the place he left at 18. His roots were deep in this part of Pittsylvania County, and he wanted a place where his vast extended family, many of whom still live nearby, could gather.

The handsome house set on a rise had a name, it turned out. Sharswood. And Sharswood had a history. And its history had everything to do with Miller.

Read the full article here.

More Breaking News here .

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech . Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here .

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

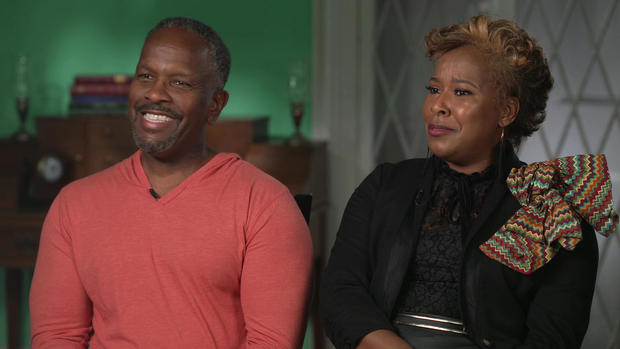

Inside the Sharswood Plantation: Family discovers ancestors were enslaved there after buying the home

GRETNA, Va. (WDBJ) - Driving down Riceville Road, its hard to miss the large gothic-style home in this rural community.

But beyond the 200-year-old walls lies a deep history uncovered by the descendants of the slaves who lived and worked on the Sharswood Plantation.

“We have a very big family,” said Fredrick Miller, owner of Sharswood. “I just wanted to be able to bring them all together at special times and just celebrate.”

In 2021, Fredrick Miller was looking for a house to host family events and reunions. His sister, Karen Dixon-Rexroth, convinced him to buy the home just up the road from their mother’s house.

“We often passed the house probably several times out of one day. So, just think of how many millions of times we passed this property and never really wondered what it was. We just knew it was a big old house,” explained Dixon-Rexroth.

Little did they know they would soon be holding the key to the big old house unlocking the history of their enslaved Miller ancestors.

“I said, ‘oh, my God. Do you know what you just did?’ explained Dexter Miller, Fred Miller’s cousin. “I knew the history of the house, but I did not have facts.”

Cousins Miller and Dixon-Rexroth immediately began searching for those facts and then reached out to local historian Karice Luck-Brimmer.

“When I started doing this research for them, I had no idea that it was going to place them there,” said Luck-Brimmer.

Click here for other stories on Black History Month

Luck-Brimmer began her research at the Pittsylvania County Courthouse where she found a labor contract signed by slave owner and homeowner Nathanial Crenshaw-Miller on August 1866.

“They were by the enslavers after emancipation. A lot of times, the formerly enslaved, they just couldn’t move on. You’ve been here your whole life. A lot of people hadn’t been outside or off the lands of the plantation. So, it’s like, ‘how am I going to feed my family?’ A lot of them chose to stay on as sharecroppers. That’s where we have the labor contract between Nathaniel Crenshaw-Miller and at least 10 of the people that he enslaved.”

Among those 10 slaves were David and Violet Miller - their great, great grandparents. Enslaved, and married, on the same property he now owned.

“Words cannot express how I felt when I found out that my relatives actually were a part of this plantation, and I walked on the same grounds that my ancestor walked on. Tears began to roll. You feel like you’re home at last,” added Miller.

Everything down to the nails was made by the slaves. There were least 58 on the 2,500-acre plantation at one time.

“We see this big house here that faces the road, is really nice. But, when we go directly behind there, where the less fortunate people worked live, it’s a totally different world. I want people to see that and to understand that slavery did happen. It impacted people in a different way. I also think that the residuals of slavery exists today,” said Miller.

The Millers plan to restore the slave quarters on the property where their ancestors ate, slept, and cooked for their enslavers.

“It’s still standing. I’m proud that I know that my people put in the work to have that built, even though it was during a time of slavery and during slavery there was oftentimes of being abuse or neglect. I know that they were strong people and within that, that building still stands strong,” added Dixon-Rexroth.

The slave cemetery tombstones without names also stand strong, but years of neglect have made them unidentifiable to the naked eye.

Periwinkle covering the ground and the headstones that all point East toward Africa are the signs that revealed the gravesite to the Millers.

“Everyone should be laid to rest with some kind of dignity. To me, the way it is now, I think if you had an animal that passed on, you will probably put them the rest in a more dignified way, and it shouldn’t be that way. So, I want to do everything I can to make that better,” explained Miller.

They plan to host their second annual Juneteenth celebration event on the property June 18.

The big old house on Riceville Road will now welcome anyone to discover the history of Sharswood .

“It means a lot to me because I know that I can do something different with it. I want it to be a place that’s open, a welcoming kind of place. I don’t want it to be a place where you feel like, ‘I drive up and I just can’t go there.’ You can go there. You can come to Sharswood,” added Miller.

To learn more about Sharswood or donate to their GoFundMe to help restore and preserve the property, visit SharswoodFoundation.com .

Copyright 2023 WDBJ. All rights reserved.

Six people, including three children injured after driver crashes into home

Bedford County School Board sues parent for $600,000 after disputes over son’s special needs education plan

Child hit by driver in Roanoke

Two people shot in Southwest Roanoke, suspect still at large

Two men arrested in ongoing investigations with offenses against children

Latest news.

National Park Service seeking food truck vendors for Mabry Mill

Parents react to new Roanoke City Public Schools transportation system proposal

Roanoke volunteer fire department seeks donations to save historic truck

Little Feet Meet Turnout

National Down Syndrome Association of the New River Valley hosts annual W.A.L.K. event

Watch the cbs 60 minutes special on youtube: sharswood

Sharswood Foundation

We need Your Generous Support

to Restore the

Slave Dwelling and Cemetery

Your donation will help us restore a slave cabin in Virginia

Thank You to Leslie Stahl and CBS 60 Minutes!

Watch the replay on YouTube here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oPk2F3rxetk

To all who tuned in to the 60 Minutes episode...Thank you! My family and I are forever grateful for the outpouring of support, kind words, and donations to help restore the dilapidated slave dwelling and cemetery, overgrown with weeds . We are overjoyed and hopeful that our family's discovery at Sharswood may serve as a catalyst for a better understanding of slavery in America.

We all have a part in making a difference.

At Sharswood, I will do my best to fix many of the visibly broken things...but I cannot do it alone. Your donation will make it possible for professional historical restoration workers to join me.

~Fredrick Miller

Help Our Cause

Your generous donation will help fund our mission. Please Click the Donate button or make your check payable to:

5685 Riceville Rd. Gretna VA 24557

Donations to the Sharswood Foundation are

tax-deductible. Sharswood Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit--IRS EIN #88-2598753.

Learn More About black hisory in virginia

Montpelier, va, shirley plantation, nottaway county.

Montpelier - A memorial to James Madison and the Enslaved Community, a museum of American history, and a center for constitutional education that engages the public with the enduring legacy of Madison's most powerful idea:

government by the people.

https://www.montpelier.org/

Nottaway County had the highest percentage of enslaved people at 74 percent. Nottoway County was first inhabited by native American Indians of the Iroquoian nation tribe called Nadowa. This name was Anglicized with the coming of English settlers to 'Nottoway.'

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nottoway_County,_Virginia

The oldest plantation in Virginia, dating back to 1613. It was a tobacco plantation and the primary labor force was enslaved Africans and their descendants. The tobacco was shipped within the colonies and to England. Now home to Upper Shirley Vineyards.

https://historicshirley.com/

Monticello, VA

Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion. Black women were bred to increase the number of enslaved people for the slave trade, and children were sold.

https://time.com/5653369/august-1619-jamestown-history/

Legislation

Laws and practices limited the behavior of African Americans, for example, by not allowing blacks to meet in groups, have firearms, or raise livestock. They could only leave plantations for four hours at a time and needed written permission to travel.

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/

The primary plantation of Thomas Jefferson, a Founding Father and the third president of the United States. Historians agree that Jefferson fathered six children by his enslaved mistress, Sally Hemings, who was also half-sister to Jefferson's wife.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sally_Hemings

5685 Riceville Road, Gretna, Virginia 24557, United States

707-344-5145

Copyright © 2024 Sharswood Foundation - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.

- Subscriber SErvices

- Place an Ad

- Saved items

Chatham, VA (24531)

A mix of clouds and sun. High near 70F. Winds ENE at 5 to 10 mph..

Partly to mostly cloudy. Low 47F. Winds E at 5 to 10 mph.

Updated: April 25, 2024 @ 1:06 pm

- Full Forecast

The Miller family hosted a Juneteenth celebration at Sharswood in June — and where their ancestors had once been slaves.

- Photo courtesy of Karen Dixon

- Copy article link

Members of the Miller family relax on the front porch of Sharswood, taking a break from Juneteenth preparations last month. From left to right: Betty Miller Dixon, Sheila Tucker, Frederick Miller and Karen Dixon.

- Diana McFarland/Star-Tribune

The Sharswood house was built in the early 1850s by architect Andrew Davis and is of a gothic-style design. It still retains many of its original features, such as 300 diamond-shaped panes of glass some of the interior doors.

Frederick Miller said he has trouble going inside what has now been determined to be one of the 12 former slave houses on the property. This structure is located directly behind the main house.

This structure, located behind the main house, has been determined to have once been one of the 12 slave houses located at Sharswood. Those who attended the Juneteenth celebration that day had a chance to see it up close.

One of the original fireplaces in the manor house.

A view of the staircase from the second floor of the manor house.

The former office of the plantation overseer. Frederick Miller has turned it into a heritage center for his family.

This large oak tree is located between the manor house and former slave house and was likely on the property during the time of slavery. Frederick Miller wonders what the tree had witnessed during that time.

A document containing information about the Sharswood plantation and located in the Pittsylvania County Courthouse records room.

- Photo courtesy of Sonya Womack-Miranda

The interior of the former overseer's office has been devoted to the heritage of the Miller family.

The Juneteenth celebration at Sharswood included African dancing and drumming.

Celebrating the end of slavery where their ancestors were slaves

- By DIANA MCFARLAND Star-Tribune Editor

- Jul 16, 2022

Juneteenth was declared a national holiday in 2021 and on its second anniversary, the Millers were going to celebrate in style. The large, extended family invited the public to come to Sharswood — a former tobacco plantation — to enjoy food, live music, African drumming and more.

Juneteenth marks the end of slavery in the United States, and like many black families, the Millers wanted to do it up big. But the family’s party at Sharswood, which Frederick Miller bought in 2020, had a special connection to Juneteenth.

It turns out that Frederick and his family are descendants of two individuals who had once been slaves at Sharswood — David and Violet Miller.

For sale sign

Karen Dixon was on her way to Walmart when she saw the for sale sign posted in front of what was she had always called “the scary house,” an imposing Gothic style farm house sitting on a sweeping swath of lawn about 10 miles from Gretna.

She called her brother, Frederick Miller, a retired Air Force civil engineer who had moved to California years ago for the military. Frederick had been looking for a place where his large extended family could gather back home in Pittsylvania County. Having grown up in the area, Frederick knew of the house and property, but hadn’t thought much about it beyond that. The Thompson family had owned the property since 1917.

While the sprawling property wasn’t exactly what he was looking for, Frederick submitted two bids for the house before it was accepted. He purchased the fully furnished house, its outbuildings and 10 acres for $225,000 in May 2020.

Once the sale closed, Karen and Frederick began doing some research and learned that Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller had been the original owner, as the house was built about a decade before the Civil War. Having the same last name as the antebellum owner struck a cord.

Karen wondered if their family was somehow connected, given that they all lived within five miles of what they learned the “scary house” had once been called — Sharswood.

In the South, it was common practice for former slaves to take the surnames of their white owners.

After some time, Karen was able to get in touch with Karice Luck-Brimmer, program associate with Virginia Humanities.

Luck-Brimmer has been delving into the histories of Pittsylvania County families for years, so she is well acquainted with many of the family names and ancestors in the area. In this case, Luck-Brimmer had begun researching the Miller family years earlier to help a woman, Alma Miller Turner, who she had lived next door to as a child. At the same time, Virginia Humanities was compiling a study of slave dwellings in Virginia and a structure at Sharswood was included.

In this way, “I felt like it was all meant to come together,” she said.

Luck-Brimmer said that in her work, she begins with the present day family and starts working backwards.

For the Millers, the name they used to begin the search was Sarah Miller.

Another search

Meanwhile, cousins Dexter Miller and Sonya Womack-Miranda had for years been researching the family tree to, in the words of Sonya’s mother - “find out who we are.”

They too were armed with one name to begin their search — Sarah Miller.

Sonya and Dexter said the search for the family’s origins began before Fred bought Sharswood and was something their cousin was unaware of.

Sonya began her research in 2011 and her quest took her to Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah, where she visited the Family History Library. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or Mormons, have created the largest genealogical library in the world and it is open to the public.

Sonya said there were thousands of Sarah Millers, but her mother told her to look for the name of Sarah’s son, as well as her brother. Their names were more unusual and made it easier to pinpoint the correct Sarah Miller, said Sonya, who requested that their names not be published.

Ultimately, Sonya came upon David and Violet Miller — Sarah’s parents.

Since their birth dates were prior to the Civil War, Sonya realized they must have been slaves.

Dexter and Sonya said an aunt, Alberta Miller Womack, who at the time was in her mid-80s, assisted in their efforts. Dexter said Alberta knew of this history and wanted it properly compiled so the family would know its origins. Alberta died in 2019.

Sonya said that while she and Dexter were doing this work, she would see Frederick at family gatherings, but didn’t talk about what they had learned about Sarah Miller.

Frederick lived on the other side of the world and didn’t know what they were learning, said Sonya.

Frederick knew Dexter was doing some family research and that the previous owner of Sharswood had told his cousin that his ancestors could have been part of the plantation.

It was after he bought the property that the pieces began to fall into place, said Frederick.

In the past it had been difficult for African-Americans to trace their lineage. However, with the advent of DNA testing and large genealogical databases, such as Ancestry.com , it has become far easier, said Sonya.

Sonya said Ancestry is now able to link a slave to his or her slave owner.

It was an 1850 federal census “slave schedule,” where Sonya found Violet. It stated she was born in 1822, was 28 years old in 1850, lived in the northern district of Pittsylvania County and the slave owner’s name was N.C. Miller — Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller.

Sonya, who lives in Maryland, traveled to the Pittsylvania County Courthouse and began digging through the records. She wasn’t initially looking for the Millers, but tracked the house and property back through the Thompsons, who had owned it for more than 100 years.

Her grandfather had once told her it had been the Miller plantation, and as she searched the records, she found it — Charles Edwin Miller — nephew of Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller.

“He was right, he was right. It was the Miller plantation,” said Sonya.

“It’s in the books,” she said, adding that the original plat also listed the plantation name as Sharswood.

Detective work

As a professional genealogist, Luck-Brimmer likes to have two pieces of documentation in hand to verify a family connection. Her search of the Millers took her to the archives at the University of North Carolina where she found the Crenshaw Miller papers. Among those documents was a labor contract dated from August 1865 that listed David and Violet Miller as sharecroppers who agreed to remain on the plantation. The couple had 10 children.

One way to trace slaveholders and slaves is to use the Virginia Slave Births index, she said. It has been digitized and some of it is in the Danville library, but it’s also easy to use through Family Search, said Luck-Brimmer.

Luck-Brimmer said that when black people are trying to search their enslaved ancestors that it is important to look at the enslaver too. The trick is to look for naming patterns, as well as to check wills and deeds, as those will contain valuable information.

With Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller, Luck-Brimmer wasn’t able to find a slave inventory because he died after 1865 — the end of the Civil War.

If someone died after 1865 there was no slave inventory in the will, she said.

Luck-Brimmer said that as she went through the Virginia Slave Births index looking for Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller, she found Violet listed along with two of her children — Samuel and Charity —who were the brother and sister of Sarah.

Subsequently, many Millers who came to the Sharswood Juneteenth celebration were able to be connected to the former slave plantation through Luck-Brimmer’s work.

“This research is changing people’s lives. It’s bringing people together,” she said, adding that it is also building an inclusive narrative of life in America.

This work is also putting the focus on the shared history of all who lived and worked during this time, said Luck-Brimmer.

One doesn’t typically hear about the enslaved people, who not only helped build these plantations, but were also the economic base of the operation, she said.

“We find out we’re more alike than different,” she said.

The original plantation had roughly 2,000 acres and grew mostly tobacco. It was nearly a town unto itself, as it produced most of what was needed and likely included a blacksmith and was associated with two mills. Sharswood had 58 slaves and 12 slave houses before the beginning of the Civil War. Two of those slaves were David and Violet Miller.

“That was a little hard to hear,” said Frederick of the number of slaves, to include his ancestors, who were kept on the former plantation.

Today, when Frederick looks across what was once vast tobacco fields toiled over by his ancestors, he said it’s difficult to digest what had once happened on the property he now owns.

There is an ancient oak tree behind the main house that was likely there when the plantation had slaves, and Frederick wonders what it had witnessed during those years. He often reflects about the lives his ancestors must have led as slaves on the property he now owns.

Behind the house, and the oak tree, is a structure that an architect has determined had once been a slave house. It had originally been one room, but was later divided in half to accommodate two families.

Frederick said he has a hard time going into the former slave house, as it saddens him to think that people had to live in such a small, rough space — especially considering the grandeur of the main house not more than 100 yards away.

It is also disheartening to think that, at the time, the government sanctioned slavery, he said.

In addition to the remaining slave house, there is a former smoke house and the overseer’s office, which has two stories and a porch. Today, Frederick has set it up as a heritage center for the Miller family.

Frederick said one reason he bought the property was that it was large enough to accommodate his family during reunions — events that can draw more than 300 people.

“We have a huge family,” he said.

Cousin Sonya has traveled to Ghana as part of her personal journey, and has touched the walls of the “slave castles” there. While in the cramped and gloomy “slave castles,” she reflected on the forces that brought her former ancestors to the United States as enslaved people.

When she visited Sharwood, Sonya did the same thing — touched the walls — this time in the slave house.

“It was amazing,” she said.

As he walks through the main house, which was built by architect Andrew Davis, Frederick points to some interesting details, such as the marble doorknobs and 3,000 diamond-shaped panes of glass that make up some interior doors in the house. One of the tiny panes of original glass contains the initials of the builder.

Frederick’s mother, Betty Miller Dixon, has always lived nearby and thought the house was interesting but never imagined she would be able to see inside, much less have her son own it.

Betty, 82, was unaware of the family’s slave history.

The family didn’t talk about the slave era, but they did talk about being sharecroppers, said Betty.

Karen said it was likely because it seemed so long ago, but in reality, it wasn’t.

After all, the ancestor who connected the present day Millers to the plantation, Sarah, died in 1949 — when Betty was a child.

Dexter said it’s not uncommon for black families not to discuss slavery as it was too painful. And until recently, the records dating back to the slave era were “horrible,” he said, adding that all they’ve been able to find is an estimate of Sarah’s birth, which occurred sometime between 1869-1874.

Dexter said sharecropping was far from an improvement over slavery, as once all the costs were divvied up and paid back to the plantation owner, the black sharecropper “basically got nothing.” However, with the animus against the newly freed slaves running high after the Civil War, many chose to remain on the plantation to be safe, he said.

Based on their research, it appears David and Violet remained at Sharswood the rest of their lives, Dexter said.

Dexter said more than 1,000 people attended Juneteenth at Sharswood. But that celebration, remarkable and special in itself, came after a family reunion in 2021 — and not long after Frederick bought the property.

“Unexplainable,” said Dexter about that day.

To think that the family was celebrating on a planation where their ancestors were once slaves, “was so special,” he said.

For Karen, the experience of celebrating the end of slavery at the same place where her ancestors were once enslaved was overwhelming.

To think that none of their ancestors had entered the house through the front door, but the present day Millers were able to give at least 200 tours that day, she said.

It also provided a pleasing sense that Violet and David would be happy to see where the family is at today, said Karen Dixon.

For Frederick, owning the property his ancestors were once enslaved upon — and celebrating the end of slavery — is as if life has come full circle. He believes that he was meant to obtain the property and it will now become his focus.

“It’s my duty to tell the story as much as I can,” he said.

Post a comment as anonymous

- [whistling]

- [tongue_smile]

- [thumbdown]

- [happybirthday]

Your comment has been submitted.

There was a problem reporting this.

Watch this discussion. Stop watching this discussion.

(0) comments, welcome to the discussion..

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language. PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK. Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated. Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything. Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person. Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts. Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.

Time moves forward again on Main Street | Nov. 11, 2015

- Bobby Allen Roach/Star-Tribune

- Apr 24, 2024

Eugene Volk stands with his wife, Barbara, in front of the newly repaired clock at First Citizens Bank on Main Street in Chatham. Volk repaired the clock over three visits from his home in North Carolina.

Today's most clicked stories.

- Group not denied service, says Danville restaurant owner

- Pittsylvania County Schools employee remembered

- Tornado touches down in Swansonville

- Turille out as Pittsylvania County administrator

- Town of Chatham completes Silas Moore Park pavilion improvements

- ‘The desecration across the tracks’

- DR Softball remains unbeaten in district action

- Chatham Hall to host VISAA Girls Invitational State Tournament April 22

- Electoral Board seeks consistency for Dan River precinct

- Chatham faces impending deficit in water revenues

Watch Caesar's Being Built in Danville

Livestream of the future caesars virginia site, newsletters.

Success! An email has been sent to with a link to confirm list signup.

Error! There was an error processing your request.

News Alerts

We'll send breaking news and news alerts to you as they happen!

Star-Tribune e-Edition

Receive our newspaper electronically with the e-Edition email.

Star-Tribune News Updates

Would you like to receive our daily news? Signup today!

Latest e-Edition

Chatham star-tribune.

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

An old Virginia plantation, a new owner and a family legacy unveiled

GRETNA, Va. — There was so much Fredrick Miller didn’t know about the handsome house here on Riceville Road.

He grew up just a half-mile away and rode past it on his school bus every day. It was hard to miss. The home’s Gothic revival gables, six chimneys, diamond-paned windows and sweeping lawn were as distinctive a sight as was to be seen in this rural southern Virginia community. But Miller, 56, an Air Force veteran who now lives in California, didn’t give it much thought. He didn’t know it had once been a plantation or that 58 people had once been enslaved there. He never considered that its past had anything to do with him.

Two years ago, when his sister called to say the estate was for sale, he jumped on it. He’d been looking, pulled home to the place he left at 18. His roots were deep in this part of Pittsylvania County, and he wanted a place where his vast extended family, many of whom still live nearby, could gather.

The handsome house set on a rise had a name, it turned out. Sharswood. And Sharswood had a history. And its history had everything to do with Miller.

Slavery wasn’t something people talked much about in this part of Virginia when Miller was growing up in the 1970s and 1980s. And other than a few brief mentions in school, it wasn’t taught much, either.

The only time he remembers the subject coming up was when Alex Haley’s miniseries, “Roots,” was broadcast in 1977.

“For a lot of us, that was our first experience with what really happened during slavery,” he said. “It just wasn’t discussed.”

Miller assumed his ancestors had been enslaved. But where and when and by whom were questions that were left unasked and unanswered.

“People didn’t want to talk about this stuff because it was too painful,” said Dexter Miller, 60, a cousin of Fredrick’s who lives in Java. “They would say, ‘This is grown folks’ business.’ And that’s how some of the history was lost.”

Teaching America's truth: How slavery is taught in America's schools

Another cousin, Marian Keyes, who taught first in segregated schools and later in integrated schools from 1959 to 1990, said that for a long time there was little teaching about slavery in Pittsylvania County.

“We weren’t really allowed to even talk about it back then,” said Keyes, who turns 90 this year and lives in Chatham. “We weren’t even allowed to do much about the Civil War and all of that kind of stuff, really.”

Even outside of school, when she was growing up, Keyes said, the subject of slavery was avoided.

“I just thought everything was normal,” she said, “because that was the way of life.”

But the unspoken history left a gulf.

It wasn’t until after Fredrick Miller bought Sharswood in May 2020 that its past started coming into focus. That’s when his sister, Karen Dixon-Rexroth and their cousins Sonya Womack-Miranda and Dexter Miller doubled down on researching their family history.

What neither Fredrick Miller nor his sister knew at the time was that the property had once been a 2,000-acre plantation, whose owners before and during the Civil War were Charles Edwin Miller and Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller.

Fredrick Miller and so many members of his extended family were born and grew up in the shadow of Sharswood — and perhaps it was a clue to a deeper connection. It wasn’t uncommon after emancipation for formerly enslaved people to take the last names of their enslavers. But establishing the link required more research.

More than 1,700 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation.

His sister and cousins scoured genealogy sites and contacted Karice Luck-Brimmer, who works in community outreach with Virginia Humanities in Pittsylvania County and researches local African American genealogy. They pored over court and real estate records, examined census data and revisited family tales passed down over generations.

As the puzzle pieces connected, a clearer picture emerged. Sarah Miller, great-grandmother to Fredrick, Karen and Dexter, and great-great-grandmother to Sonya, died in 1949 at 81. From her death certificate, they learned that Sarah’s parents were Violet and David Miller.

The 1860 Census does not list enslaved people by name, only by gender and age. In the 1870 Census, however, Violet and David Miller lived just a short distance from Sharswood. Between the many documents that the descendants of Sarah Miller have obtained, the fragments of family oral history they’ve sewn together and the proximity of the family to the plantation, they are certain that Violet and David Miller were among those enslaved at Sharswood.

More clues continue to emerge. An entry in the Virginia Slave Births Index uncovered this month by Luck-Brimmer shows that a boy named Samuel was born to Violet in Pittsylvania County on May 9, 1864. N.C. Miller is listed as the enslaver. In the 1870 Census record for Violet and David Miller, Samuel, age 5, is listed as a member of the household. Sarah, his youngest sister, also is listed as a member of the household. She would have been 2, although no age is given for her in the record.

The newly discovered document “hands-down places them on the plantation,” Womack-Miranda said after seeing the entry. “It can never be disputed.”

For Fredrick Miller, the 10.5-acre-estate he’d purchased for $225,000 ended up not being just a future gathering spot for the family, but also its first traceable point in the United States — an astonishing revelation for him. It also left him thinking about family history and the absence of that history for many people like him.

“You’ve got to know where you come from,” he said in a phone interview from his California home. “You’ve got to know where you come from. It’s unfortunate that a lot of us don’t.”

In an undated photo of Sarah that family members have shared with one another, the mother of seven wears wire-rimmed glasses and faces the camera with a somber expression. When he looks at the photo of his great-grandmother, Fredrick Miller sees sadness in her face. But, he hopes, maybe this purchase has brought some redemption.

With Sharswood in his hands, her family is reclaiming its past .

“I just hope that somehow she’s looking down from heaven and finally cracking a beautiful smile,” he said.

On a recent mid-December day, the oaks and walnuts that tower nearby had shed all of their leaves. A dry spell had turned the winter grass browner still. But Sharswood still shone, with its bright white paint accented with black shutters and a green metal roof. Immaculate.

Designed by the famed New York architect Alexander Jackson Davis and built in the middle of the 19th century, Sharswood signaled success.

Even with the additions and paint jobs over the years, it’s not hard to envision how the house looked before the Civil War, when it was the hub of one of the largest tobacco plantations in Pittsylvania County. And it’s not hard to envision the enslaved men, women and children who toiled to harvest that tobacco and enrich the plantation’s owners.

Approximately 550,000 people in Virginia were enslaved at the outset of the Civil War — roughly a third of the commonwealth’s population — Virginia Museum of History & Culture figures show.

In Pittsylvania County, closer to half of the population was not free. Those enslaved at Sharswood in 1860 ranged in age from 1 to 72, according to Census figures. Thirty-five were 12 or older and considered adults on the census count. There were 23 children. Of the 58 total, 31 were female.

There were 12 houses for enslaved people on the plantation, determined Doug Sanford, a retired professor of historic preservation at the University of Mary Washington, who has been documenting former homes of the enslaved across Virginia with Dennis Pogue, an associate research professor at the University of Maryland and retired archaeologist.

The census numbers are a small window into the plantation’s life. But not much more.

For many Black Americans, slavery is a brick wall that prevents them from finding out more about their past before emancipation. Census records before the Civil War rarely provided names of enslaved people. Some owners kept records that included first names and the prices they paid to buy an enslaved person or what they received for selling one, but personal details are scarce. Separations of families made the kinship trails even more difficult to follow.

Take this quiz on the history of U.S. slavery

Even when slavery ended, the details of the people subjected to it and of their daily lives were not easy to come by. After emancipation, there often was a reluctance among those who had endured slavery to share their story with their children and grandchildren, said Leslie Harris, a professor and historian at Northwestern University who has written extensively about slavery in the United States.

“The generation closer to these experiences clearly were dealing with a traumatic memory, and they didn’t want to rehearse that memory,” Harris said. “ Toni Morrison has this line in her book ‘Beloved’ where she says ‘This is not a story to pass down.’ So, for that generation, they didn’t want to pass down that trauma.”

But for subsequent generations, Harris said, “It’s not that it’s not troubling to learn these histories, but our curiosity and our desire to understand is enough removed from that to have us ask different questions of the record.”

The dilapidated cabin behind the main house at Sharswood isn’t visible from the road. A humble structure with a central chimney dividing two rooms, it feels almost hidden. But Sarah Miller’s descendants have focused their attention on it.

What the family learned from ongoing research by Sanford and Pogue and by Jobie Hill, a preservation architect who started the Saving Slave Houses project in 2012, is that the cabin was built before 1800, probably as the main house on the property, and then was divided into a duplex before 1820. From then on, they said, it probably served as a kitchen and laundry for the main house and a living space for some who were enslaved at Sharswood.

Standing 50 feet from the 16-by-32-foot cabin in which her ancestors may have worked or lived, Womack-Miranda, 53, said the discovery of the connection has been life-altering.

“When I walk around here, I imagine my ancestors walking on the same ground, the same dirt,” she said. “As an African American, you feel like you have reached the point where you can say, ‘I’m connected to my ancestors, to my roots, to the very plantation [where] my ancestors were enslaved.’ It makes me feel whole as an African American.”

Karen Dixon-Rexroth says she, too, feels the presence of her ancestors all about the property.

But Dixon-Rexroth, 49, also has noticed the generational difference when it comes to discussing the history of the plantation. As she walked with her mother, Betty Miller-Dixon, across the backyard last month and toward the cabin, she sensed her mother’s reluctance.

“You don’t like to go there, do you, Mom?” she asked.

Miller-Dixon, 81, stopped and looked at the dwelling.

“You just wonder how they survived it,” said Miller-Dixon, whose father, Gideon Miller, was Sarah Miller’s youngest child. “I don’t want to dwell on something I can’t control, but it bothers me when I go even just to look in there.”

Thinking about what their ancestors may have endured in captivity is painful. Although the Miller men who owned the property never married, the descendants of those enslaved at Sharswood believe they had children with women on the property. They wonder about ancestors who would have had no say in that. That some of them are descendants of the enslaved and the enslaver is a real possibility. They have thought of all of that. And more.

“When I saw the cabin, a feeling came over me like I believe I’m home,” said Dexter Miller. “I could feel my ancestors, and it almost brought tears to my eyes. I can picture them sitting around the fireplace, and the stories they were telling. I’m in the presence of my ancestors hundreds of years ago who lived here and slept here and birthed here. But I also think about what happened around that big oak tree. Were my ancestors beaten there? Hanged there? That’s crept into my mind. You never know.”

Fredrick Miller thinks about what slavery has done not just to his family, but to all descendants of the enslaved.

“When people experience traumatic events, they get counseling for it. They go through a process and, you know, try to get through it,” he said. “Black folk went through that kind of stuff for hundreds of years. And then when it was over, they just said, ‘Okay, go out there and be normal.’ You know, how is that possible? We are a product of who we were hundreds of years ago. And so it’s unfortunate, because I think that we could have definitely progressed a lot further had we dealt with that stuff early on and dealt with it the right way.”

While they do not ignore the pain and privation suffered by their forebears, many in the family say the lessons they are taking from this reconnection, from this reclaiming, is that history is not fixed in place; it is always being written.

“I just imagine my ancestors walking here and how they may have felt inside that life has to be better than this,” Dixon-Rexroth said. “And now, all these years later, us having the property in our possession.”

In August, the Miller family held a huge two-day reunion on the grounds. More than 200 relatives came. Tents and chairs were set up in the yard. Tables overflowed with fried fish, grilled jerk chicken, banana pudding and corn pudding. A food truck served Italian ice. Children ran around or played in a moon bounce. There were board games, raffles, giveaways. A DJ set up on the front porch.

The Miller family reunions go back to at least 1965. Relatives told Fredrick Miller it was the best one they had attended.

Miller said that when he looked at the crowd that had gathered that weekend, he was proud that his relatives were reconnecting, not just with one another, but also with their past. The small cabin behind the house was something everyone wanted to see.

“I just sat back and was able to observe the excitement of the people who showed up,” Miller said. “It was just such a good feeling to talk to them about that place, and that’s something we’d been lacking.”

He still thinks about if he had not bought Sharswood and how the past almost slipped through the family’s fingers.

“That history would have definitely been lost,” he said. “Definitely.”

- The painful, cutting and brilliant letters Black people wrote to their former enslavers March 13, 2022 The painful, cutting and brilliant letters Black people wrote to their former enslavers March 13, 2022

- More than 1,800 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation. March 5, 2024 More than 1,800 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation. March 5, 2024

- He became the nation’s ninth vice president. She was his enslaved wife. February 7, 2021 He became the nation’s ninth vice president. She was his enslaved wife. February 7, 2021

Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities

Virtual Tour of a Slave Dwelling in Mecklenburg County

This is a virtual tour of a slave dwelling at Prestwould plantation, on the north side of the Roanoke River, near Clarksville in Mecklenburg County. The cabin was erected in two phases in 1790 and 1829. Sir Peyton Skipwith built the main plantation house and moved his family there in in 1797. Prestwould is considered the best-documented plantation in Southside Virginia.

- “Interview with Cornelius Garner” (Unknown, May 18, 1937)

- Housing for the Enslaved in Virginia

Never Miss an Update

Partners & affiliates.

Encyclopedia Virginia 946 Grady Ave. Ste. 100 Charlottesville, VA 22903 (434) 924-3296

Indigenous Acknowledgment

Virginia Humanities acknowledges the Monacan Nation , the original people of the land and waters of our home in Charlottesville, Virginia.

We invite you to learn more about Indians in Virginia in our Encyclopedia Virginia .

Watch CBS News

The house that unlocked a family's history

By Keith Zubrow

August 28, 2022 / 6:59 PM EDT / CBS News

When Fred Miller, a 56-year-old Air Force veteran, purchased the white, Gothic Revival-style house with the green roof near his childhood home in southern Virginia, he wanted a large space to host gatherings for his close extended family. He was not expecting to unlock hidden chapters from his family's past.

Miller did not know it at the time, but his new property was once a plantation. Named Sharswood, it was built in the 1850s by a slave-owning uncle and nephew who shared his last name.

"If I had known there was a 'Miller Plantation,' I maybe could have… put a connection with the last name Miller and that plantation," Miller told 60 Minutes. "But I'd never heard of a 'Miller Plantation' or a 'Miller' anything."

This Sunday on 60 Minutes, correspondent Lesley Stahl interviewed Fred Miller and members of his family at Sharswood, speaking about what they unearthed about the property and its past inhabitants.

Fred Miller's sister Karen Dixon-Rexroth, who initially convinced her older brother to buy the property, and their cousins Dexter Miller and Sonya Womack-Miranda, did most of the research into Sharswood's past.

"Something drew me to knowing the history of this place," Dixon-Rexroth told Stahl. "I knew it was an old place from the 1800s, so I started from there, as far as looking at the previous owners, and also any records that were available online."

With time and the help of Karice Luck-Brimmer, a local historian and genealogist, the Millers were able to uncover documents that proved that their own ancestors were once enslaved at Sharswood.

"Since the revelation… I know that when the slaves brought food into the main house, they came up through the basement stairs," Fred Miller told 60 Minutes. "And there's a distinct wear on the basement stairs from years and years of traffic, of people walking up those stairs, I'm thinking, 'Wow, these are my people.'"

When the 60 Minutes producing team of Shari Finkelstein and Braden Cleveland Bergan first visited Sharswood to meet the family and scout the location, they were part of a conversation between Dexter Miller and his former coworker Bill Thompson, whose family bought the property in 1917 and owned it for more than a century. Thompson's sister sold it to Fred Miller in May of 2020.

It was during this conversation that Miller asked Thompson the one question that had been on his mind for a long time.

"I said, 'Bill, there's one question that's been bothering me: Where is the slave cemetery?' He said, 'Dexter, it's right over there.' I said, 'Right over where?' He said, 'You see those trees over there?'"

And with that revelation, as seen in the video above, the 60 Minutes team accompanied the Millers to a cluster of trees just beyond Fred's property line, where for the first time they saw the likely burial site of their enslaved ancestors. Several weeks later, Lesley Stahl visited the site with Fred, who lives in California, and his sister Karen.

"It was heart-wrenching', I'll tell you that," Fred Miller said about seeing the cemetery for the first time. "Just to think that all these years of me wondering, and it was right under my nose the entire time, right here."

Fred Miller told 60 Minutes he plans to clean up the cemetery and is in the process of creating a non-profit foundation to also restore the slave quarters on the property to help educate people interested in the history of slavery. His sister said, for her, Sharswood has become a place of profound meaning and connection with the past.

"I would definitely say throughout this property I can feel something within me when I'm walking around, simply doing anything," Karen Dixon-Rexroth said. "I know that our ancestors are looking down on us with a smile."

You can watch Lesley Stahl's full report on Sharswood below.

The video above was originally published on May 15, 2022 and was produced by Keith Zubrow and edited by Sarah Shafer Prediger.

More from CBS News

Woman, 74, who allegedly robbed bank may have been scam victim, family says

Baby saved from dying mother's womb after Israeli airstrike named in her honor

Royal family releases new of Prince Louis to mark 6th birthday

U.S. birth rate drops to record low, ending pandemic uptick

- Subscriber Services

- Place an Ad

- Saved items

Altavista, VA (24517)

Sun and clouds mixed. High around 70F. Winds E at 5 to 10 mph..

Partly cloudy early with increasing clouds overnight. Low 48F. Winds E at 5 to 10 mph.

Updated: April 25, 2024 @ 1:29 pm

- Full Forecast

Raising awareness and celebrating freedom at Sharswood

- Jun 21, 2023

- Copy article link

By Sami Mirza

Altavista Journal News Correspondent

On a sweltering Saturday afternoon, Dexter Miller stood next to what was once a plantation office and watched dozens and hundreds of people stream into the property where his ancestors were once enslaved. It was the second annual Juneteenth celebration at the Sharswood plantation on Sunday, June 18, in honor of the federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery.

“200 years ago, this wouldn’t have been thought about, 200 years later, it’s come full circle,” he told an impromptu tour group that had formed. “Look what God can do.”

A century and a half after slavery ended, in 2020, Dexter’s cousin Fred Miller, purchased the estate to hold large family gatherings, and careful genealogical research proved the Millers now owned where their ancestors were once enslaved. The story was picked up by national media, including The Washington Post and the acclaimed CBS television program 60 Minutes.

“From the time that I got this place, I envisioned this.” Fred said. “Especially once I learned the history of Sharswood, I knew that it could be a tool for good, and we need that. It makes me happy when I see the entire community, from all walks of life, just come out here on this former plantation and break bread and have fun under a totally different situation than the origin of the place.”

Long celebrated as a commemoration of the freeing of the last remaining slaves in Texas, Juneteenth was made a federal holiday in 2021, and the Millers’ first event at Sharswood last year brought more than 1,000 guests.

This year, Dexter said the aim is to double that number. In addition to the tours, there was also a dramatic reading of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, live music from Lynchburg’s “The Drive” band, and traditional West African dances.

“It's going to get better each year,” Dexter said.

Also part of the celebration were around a dozen vendors providing food, jewelry and information, among other wares.

Angel Jones’ first babysitter was a member of the Miller family, and she brought her food truck “Lady May’s Café” almost 200 miles from the Chesapeake area to celebrate with the community.

“It feels good to just be to be in the presence of everybody,” Jones said.

For the Millers, the hope is to make Sharswood’s Juneteenth event an institution.

“We want to be known for bringing the community together, having a day where there's an awareness and a celebration and commemoration for the Juneteenth,” said Tonya Miller Pope, one of the lead organizers for this year’s event.

“We don't have that many opportunities for things like this in this county,” Fred added. “I think it's important for us to do that.”

The event has spread far beyond just Virginia though; people came from as far away as Louisiana and Chicago, and a chartered bus brought a group from Cleveland. All told, at least eight other states were represented.

“We also have people that, even though they didn’t come this year, they’re already saying, ‘are you doing this next year? Because I want to start making plans, I want to find hotel accommodations,’” Pope said. “It's open to the whole country.”

Within the county, Sharswood has already had an impact. Karen Dixon, Fred’s sister, said the experience has encouraged her to run for Pittsylvania County Clerk of Court to make a difference.

“Now going through my life, it's on the strength of those people from long ago,” she said. They are my inspiration.”

Dixon also spearheaded the addition of a LOVEworks sign to the property, right at the entryway. She said it was added to invite the community in and help put the property on the map.

“It (the story) is not for the Miller family, it’s for everyone,” Dixon said. “When they see that sign, I hope that they can reflect on positive things,”

Though the Juneteenth event was not a fundraiser, it does raise awareness for the Sharswood Foundation, the non-profit working to preserve the estate. Through the foundation, Fred hopes to restore a long-neglected slave cabin tucked away behind the main estate, to continue to educate the community about the history of slavery.

Originally built in the late 1700s, the cabin still stands next to a great white oak that Dexter estimates is 500 or 600 years old. When first arrived on the property, Dexter touched the tree, wondering what it had witnessed when his ancestors lived there.

200 years on, it’s also where he starts his tours.

“That tree is so symbolic to me because it was the only thing that was here when my ancestors were here that’s still alive,” Dexter said.

Most Popular

- 100 mile yard sale set for May 2-5

- Hurt council work session draws packed house for open discussion

- Larry Deane Pillow, Jr.

- Fishing tournaments to kick off in Brookneal this weekend

- Frances Woodall Nichols

- Hurt woman killed by gunshot

- Lacy White Powell

- McCorkle shines on the mound, leads team to 5th straight win

- Centra to host “Walk with a Doc”

- Riley Levelle "Whitey" Crouch

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular videos.

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.

Newsletters

Success! An email has been sent to with a link to confirm list signup.

Error! There was an error processing your request.

Daily Headlines

Have the latest local news delivered every afternoon so you don't miss out on updates.

News Alerts

We'll send breaking news and news alerts to you as they happen!

The Altavista Journal e-Edition

Receive our newspaper electronically with the e-Edition email.

Latest e-Edition

The altavista journal.

Preservation Virginia Blog

In the field recording an18th century building at sharswood.

By Sonja Ingram, Associate Director, Preservation Field Services, Preservation Virginia

October 20, 2021

Sharswood , designed by famed architect A.J. Davis of New York, was built in the 1850s for Charles Miller in the Mt. Airy Community of Pittsylvania County. Davis also designed Belmead in Powhatan County―one of the nation’s most noted Gothic Revival houses, which became a principal center of African American education after the Civil War; and the Virginia Military Institute campus, one of the first entirely Gothic Revival campuses in America.

The fairy-tale-like, Gothic Revival Sharswood replaced an earlier house that was destroyed by fire. A review of the Pittsylvania County 1860 U.S. Census revealed that 58 enslaved African Americans lived and worked at Sharswood, and 12 houses for enslaved people existed on the farm. The property also retains several outbuildings including an office, a brick smokehouse, a covered well, and a timber-framed kitchen/quarters. Sharswood was recorded by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1933. It was also recorded by Architect Anne Carter Lee for the Society of Architectural Historians , and is included in Madelene Vaden Fitzgerald’s 1987 book, Pittsylvania: Homes and People of the Past .

The kitchen quarters and smokehouse predate the main house, and appear to have been built in the 18th century. The timber-framed kitchen/quarters has been the subject of several investigations by architectural historians, including preservation architect, Jobie Hill, who recorded the kitchen/quarter in 2017 as part of the Saving Slave Houses Project . Also in 2017, Professor Doug Sanford of the University of Mary Washington and several of his students further recorded the building.

Mike Pulice from the Department of Historic Resources. Pulice described the kitchen quarters as, “highly significant and a rare survival.” His report includes the following description: “meticulous mortise-and-tenon braced timber-framing with massive L-shaped “guttered” corner posts; the exclusive use of hand-wrought, rosehead nails; single-piece “struck” window and door casings/molded trim; and a massive central double fireplace of stone and brick masonry construction.”

I recently visited Sharswood with Professors Doug Sanford and Dennis Pogue (University of Maryland), as part of the Virginia Slave Housing Surveyed Buildings Database. Pogue and Sanford determined that the kitchen/quarters was an 18th century, hall and parlor-type house, which was later converted into a duplex dwelling for enslaved families at Sharswood. Due to its significance and its rare state of preservation, Sanford and Pogue are planning to further record the building.

Sharswood is owned by descendants of the enslaved family who lived and worked there before Emancipation. The family is currently working with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources to have Sharswood placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Historic Sites

- Bacon's Castle

- Cape Henry Lighthouse

- Historic Jamestowne

- John Marshall House

- Patrick Henry's Scotchtown

- Smith's Fort Plantation

- A Future for Shockoe Bottom

- Revolving Fund Program

- Untold Stories

- Virginia Preservation Conference

Subscribe to the newsletter

Preservation Virginia, 204 West Franklin Street, Richmond, VA 23220-5012

phone 804-648-1889 | fax 804-775-0802 | [email protected]

© 2024 Preservation Virginia. All Rights Reserved.

You are here

- Location: Gretna Virginia Regional Essays: Virginia: Valley, Piedmont, Southside & Southwest Southside Pittsylvania County Mount Airy Vicinity Architect: Alexander Jackson Davis Types: smokehouses outbuildings kitchens offices (work spaces) dwellings slave quarters plantation houses plantations Styles: Carpenter Gothic Materials: brick (clay material) clapboard siding

What's Nearby

Related essays.

Anne Carter Lee, " Sharswood ", [ Gretna , Virginia ], SAH Archipedia, eds. Gabrielle Esperdy and Karen Kingsley, Charlottesville: UVaP, 2012—, http://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/VA-02-PI22 . Last accessed: April 25, 2024.

Permissions and Terms of Use

Print Source

Buildings of Virginia: Valley, Piedmont, Southside, and Southwest , Anne Carter Lee and contributors. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, 365-365.

At the center of what was once a 2,000-acre tobacco plantation is a fine Carpenter Gothic house built for Charles Edwin Miller. Designed by Alexander Jackson Davis of New York, Sharswood is almost a catalogue of Gothic Revival characteristics, from steep roof to clustered, polygonal chimney stacks, lacy bargeboards with finials here finished by fleur-de-lis crockets, a one-story porch with octagonal columns and tracery, diamond-paned windows, and hood molds over the windows (but no pointed-arch windows). Like most Gothic Revival houses in the area, it has a rectilinear form instead of picturesque massing.

The plantation also contained twelve outbuildings in which the enslaved population lived and worked. According to the 1860 census, there were 58 enslaved people working on the Sharswood plantation at the time, 23 of whom were children. The structures are still extant, including a farm office with sawn porch pillars, a brick smokehouse, and a cistern. One wood-frame structure was built before 1800 and likely used as the original main house. After 1820, however, the 16-by-32–foot building was divided into a duplex and used as a living space for some of the enslaved workers. It is possible that it served other purposes over time, including a kitchen and/or laundry space. The property also includes a cemetery for the enslaved, although the tombstones are unidentifiable due to years of neglect. On VA 640, just before the intersection with VA 40, is an almost abandoned mid-nineteenth-century, center-chimney workers’ house that was probably associated with Sharswood.

In 2020, the now 10.5-acre Sharswood property was purchased by California resident Frederick Miller, who had grown up in the area. Through genealogical research, Miller discovered his ancestors had been enslaved at Sharswood. Miller and his family established the Sharswood Foundation with the aim of restoring the buildings in which their ancestors lived and worked.

Crenshaw and Miller Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Hedlund, Peter. “Virtual Tour of a Dwelling for the Enslaved at Sharswood Plantation, Pittsylvania County.” Encyclopedia Virginia , December 2021. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/sharswood/ .

Heim, Joe. “An old Virginia plantation, a new owner and a family legacy unveiled.” Washington Post , January 22, 2022.

“Man unknowingly buys former plantation house where his ancestors were enslaved.” 60 Minutes . CBS News, February 12, 2023.

Sharswood Foundation. https://sharswoodfoundation.com/ .

Writing Credits

- Location: Gretna, Virginia Regional Overviews: Southside , Pittsylvania County , Mount Airy Vicinity Architect: Alexander Jackson Davis Types: smokehouses outbuildings kitchens offices (work spaces) dwellings slave quarters plantation houses plantations Styles: Carpenter Gothic Materials: brick (clay material) clapboard siding

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.

Sharswood-Help Restore Slave Cabin and Cemetery

Donations (991)

- June 3rd, 2022

Your easy, powerful, and trusted home for help

Donate quickly and easily.

Send help right to the people and causes you care about.

Your donation is protected by the GoFundMe Giving Guarantee .

- Newsletters

‘Changing the narrative’: Juneteenth celebration held at former slave plantation in Gretna

Family turns painful history into story of perseverance.

Abbie Coleman , Multimedia Journalist

GRETNA, Va. – Hundreds of people came out for the second annual Juneteenth Festival at Sharswood Manor Estate , where they strived to reclaim the narrative of Black history in Gretna.

It’s been two years since Juneteenth became an official federal holiday , and people all around the country are finding new ways to celebrate.

[RELATED: Black History Special: The New Millers]

Know what's on tap for the day ahead! Have the stories we're following delivered straight to your inbox

In Gretna at the Sharswood Manor Estate, owner Fred Miller and his family have turned the former slave plantation into a place of celebration and freedom.

“I think a place like this offers so much in terms of bringing people together, to changing the narrative on what America’s past used to be,” Miller said.

Miller and his sister, Karen Dixon’s, great-great-grandparents were enslaved on the plantation in the 1800s.

“To this day, it’s hurtful to me thinking about what they would have experienced that long ago,” Dixon said.

On Sunday, black-owned businesses, musicians and food vendors came out for a Juneteenth celebration.

Dixon says hosting the event at Sharswood shows how far they’ve come.

“We don’t have to live in the past. In moving forward, we’re going to stand on the strength of our ancestors and move forward in a positive light,” she said.

Makel Dickerson joined in the celebration.

He says it’s important to remember the history of slavery.

“Not only do we overcome that, but we’re here to say we’re here and we made it and we’ll absolutely defeat anything and any challenge,” Dickerson said.

Dickerson says even though the country has come a long way, there is still work to be done.

“Not only has that been a part of our history through slavery, but just to get here today and to combat all the racism that we do face today, and we’re still here,” he said

Organizers say they hope to continue the event for years to come.

Copyright 2023 by WSLS 10 - All rights reserved.

About the Author

Abbie coleman.

Abbie Coleman officially joined the WSLS 10 News team in January 2023.

Click here to take a moment and familiarize yourself with our Community Guidelines.

Recommended Videos

The Retreat

Nearby attractions.

We hope you enjoy your visit to Poplar Forest. Please take the time to explore all that Central Virginia has to offer.

Learn more about visiting Virginia

Attractions

Travel Packages

Peaks of otter lodge.

The natural wonder of Peaks of Otter is the main attraction here, of course, but it’s perfectly complimented by the warm hospitality at Peaks of Otter Lodge . Both are a breath of fresh air.

Completed in 1964, the Lodge is the revered flagship of the chain of visitor concessions stretching along the Virginia portion of the Blue Ridge Parkway, and one in a long line of inns and wayside houses that have sheltered travelers and visitors in this part of the world for nearly 200 years.

Today, we can offer you the beauty and tranquility of Peaks of Otter along with the comfortable newly renovated accommodations. We even have designated pet friendly rooms available. Warm yourself by the fire and enjoy drinks in the Bear Claw Lounge, unplug and decompress. The lack of in-room phones and cell service only enhances the peacefulness of the surroundings.

Explore Deeper

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Help Our Cause. Your generous donation will help fund our mission. Please Click the Donate button or make your check payable to: Sharswood Foundation. 5685 Riceville Rd. Gretna VA 24557. Donations to the Sharswood Foundation are. tax-deductible. Sharswood Foundation is a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit--IRS EIN #88-2598753. Click to Donate through paypal.

Sharswood Plantation, also known as Sharswood Manor Estate, is a historic plantation house in Gretna, Virginia. Prior to the American Civil War, Sharswood operated as a 2,000-acre tobacco plantation under the ownership of Charles Edwin Miller and Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller. The Carpenter Gothic mansion was designed by New York architect ...

This is a virtual tour of one of twelve structures that once housed the enslaved population at Sharswood, a former 2,000-acre tobacco plantation in Pittsylvania County. The 1860 census lists fifty-eight people who were held on the plantation in bondage, twenty-three of whom were children under the age of twelve. (Those above twelve were considered adults.) This sixteen-by-thirty-two-foot ...

Sharswood in Gretna, Va., was built in the middle of the 19th century and at one point was the hub of a sprawling plantation. The Pittsylvania County property now consists of 10½ acres. Out of the frame behind the large tree at right is a cabin that may have been used by enslaved people as a kitchen and laundry for the main house as well as a ...

But beyond the 200-year-old walls lies a deep history uncovered by the descendants of the slaves who lived and worked on the Sharswood Plantation. "We have a very big family," said Fredrick ...

At the Sharswood Foundation; we're bridging the gap

Sharswood. The original plantation had roughly 2,000 acres and grew mostly tobacco. It was nearly a town unto itself, as it produced most of what was needed and likely included a blacksmith and was associated with two mills. Sharswood had 58 slaves and 12 slave houses before the beginning of the Civil War. Two of those slaves were David and ...

An old Virginia plantation, a new owner and a family legacy unveiled. By Joe Heim. January 22, 2022 at 8:00 a.m. EST. Sharswood in Gretna, Va., was built in the middle of the 19th century and at ...

Man unknowingly buys former plantation house where his ancestors were enslaved 26:40. Producer's note: As a 60 Minutes producer, sometimes you read about a story that you just have to pursue.

This is a virtual tour of a slave dwelling at Prestwould plantation, on the north side of the Roanoke River, near Clarksville in Mecklenburg County. The cabin was erected in two phases in 1790 and 1829. Sir Peyton Skipwith built the main plantation house and moved his family there in in 1797. Read more about: Virtual Tour of a Slave Dwelling in Mecklenburg County

In 2011, Sonya Womack-Miranda embarked on a yearslong journey of discovery — an unearthing of her family roots and its connection to a place called Sharswood. Located between Danville and Lynchburg, Virginia, Sharswood was a 2,000-acre hub for tobacco plantations in Pittsylvania County in the 1860s. Enslaved people ranging in ages from one to ...

Miller did not know it at the time, but his new property was once a plantation. Named Sharswood, it was built in the 1850s by a slave-owning uncle and nephew who shared his last name ...

Cheryl Preheim has an in-depth conversation with the writer and producers of 'Sharswood Plantation: Legacy of Sarah Miller'.

Sharswood Manor Estate. 3,608 likes · 104 talking about this. "Sharswood", established around 1853 and was a Gothic style design by New York architect A.J. Davis.

It was the second annual Juneteenth celebration at the Sharswood plantation on Sunday, June 18, in honor of the federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery. "200 years ago, this wouldn't have been thought about, 200 years later, it's come full circle," he told an impromptu tour group that had formed. "Look what God can do.".

Oct. 20. In the Field! Recording an18th Century Building at Sharswood. By Sonja Ingram, Associate Director, Preservation Field Services, Preservation Virginia. October 20, 2021. Sharswood, designed by famed architect A.J. Davis of New York, was built in the 1850s for Charles Miller in the Mt. Airy Community of Pittsylvania County.

Watch as the Miller family discovers the slave cemetery at Sharswood, a former plantation, where their enslaved ancestors were likely buried.#60Minutes #Blac...

At the center of what was once a 2,000-acre tobacco plantation is a fine Carpenter Gothic house built for Charles Edwin Miller. Designed by Alexander Jackson Davis of New York, Sharswood is almost a catalogue of Gothic Revival characteristics, from steep roof to clustered, polygonal chimney stacks, lacy bargeboards with finials here finished by fleur-de-lis crockets, a one-story porch with ...

Discovering the history of the Miller Plantation, we share this unbelievable story about Sharswood. With the rehabilitation of the slave dwelling, our mission for Sharswood is that the former tobacco plantation will be a learning experience for the public, especially students doing research.

There were twenty-three children of the fifty-eight total, thirty-one were female. Before and during the Civil War, Sharswood was a 2,000-acre tobacco plantation owned by two brothers, Charles Edwin Miller, and Nathaniel Crenshaw Miller. Fredrick Miller and his extended family had grown up in the shadow of Sharswood.

In Gretna at the Sharswood Manor Estate, owner Fred Miller and his family have turned the former slave plantation into a place of celebration and freedom. "I think a place like this offers so ...

Docent-guided tours are currently offered four times daily as docents are available. 1776 Poplar Forest Parkway. Lynchburg, VA 24502. Mailing Address: P.O. Box 419. Forest, VA 24551-0419.