Quality worth making room for

What we tell ourselves about the Springbok tour

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

September 12, 1981 has come to represent the crescendo of the ill-fated Springbok tour. On this day 40 years ago, around 2000 protestors descended on a fortress-like barbed wire-clad Eden Park as the Springboks and All Blacks played a series-deciding final test. Inside the stadium, a light aircraft made low flying swoops over the ground throughout the game, sometimes barely making it over the goalposts, dropping bags of flour onto the field and players. With the Hamilton pitch invasion, the ‘flour-bomb test’ has endured in the public conscience.

Amid a raft of commemorations for the tour’s 40th anniversary, it is worth considering how this day will be remembered and what this tells us about national history making. Most commemorators will likely emphasise the unscripted drama that unfolded inside the stadium, in the skies above it, and in the streets outside. Some will recall the match as riveting, which among the flour bombs ran 10 minutes overtime and took an Alan Hewson penalty to win the match and series for the All Blacks. Others will raise an incident where a group of peaceful protesters outside Eden Park dressed as clowns were senselessly beaten by police. Fewer still will recall that on a tour shrouded in apartheid controversies, the final test was scheduled on the fourth anniversary of the death of activist and founder of South Africa’s Black Consciousness movement Steve Biko, who was murdered while in police custody by white officers.

But the contemporary representation of 1981 as an anti-apartheid endeavour also forgets that the anti-tour movement was as much a critique of New Zealand society.

But likely none will consider that the stories they contemporarily tell about the Springbok tour are as much a product of the time during which they are produced as they are an attempt to recall the past. For in the process of turning the unobservable past into a comprehensible history for the present, we inevitably look at the past through the ideological lens of contemporary values. And as values and the present change, so does the way we evaluated, narrate, and historicise the past. While the past is unchangeable, history is always shifting and evolving as certain parts of the past become emphasised, while other, less palatable parts are forgotten based on what is valued in the present. Exploring what is told about the Springbok tour at a given historical moment can tell us a lot about the social values of the time.

The contemporary emphasis on New Zealand as a bicultural, anti-racist society has meant that 1981 is most commonly ‘remembered’ as the country’s struggle against the horrifically racist apartheid system. But this obscures and forgets the more unpalatable reality that there was substantial support for the tour among many New Zealanders.

Stadiums were sold out and attracted more than three-quarters of the country’s television audience. Few will recall that the predominantly white Springbok team (one player and one manager were not white) received scores of letters from New Zealanders welcoming and supporting them, or that New Zealand’s far right groups, who sought closer relationships between white people across the two countries, enjoyed perhaps their biggest influx of support and highest public profile when rugby ties with South Africa became contested.

Rather than accepting historical accounts at face value, it is important to ask why some parts rather than others endure and come to represent what we ‘know’ about the past.

But the contemporary representation of 1981 as an anti-apartheid endeavour also forgets that the anti-tour movement was as much a critique of New Zealand society. Journalist and activist Geoff Chapple recalled in 1984 that the tour had “grown far beyond the original anti-apartheid issue. It now defined a whole belief system about what was right and wrong about New Zealand itself”.

Apartheid may have catalysed the movement, but the anti-tour protests also became an outlet for many of the domestic social tensions of the previous decades. Protesters raised their frustration at: a conservative government which deported Pacific Island ‘overstayers’, annexed Māori lands but encouraged the immigration of white South Africans; a national sport that promoted restrictive gender roles, toxic patriarchal masculinity, excessive consumption of alcohol and a culture of violence; and institutionalised racism which many Māori linked to the experiences of black South Africans.

Emphasising 1981 as primarily an anti-apartheid struggle obscures the complexity of the anti-tour campaign. It serves largely to construct New Zealand society in a favourable way which forgets some of the unpalatable realities that accompanied the tour.

How the Springbok tour has been understood by New Zealanders has evolved over 40 years (and will continue to evolve) in response to changing material conditions. By treating histories of 1981 as a kaleidoscope of partial, contested and selective narratives which seek to impose particular meaning on the past, we can learn much about the purpose of their creators, the eras in which they were created, and the way we make meaning as a nation more broadly.

Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter

Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter is a teaching fellow at the University of Otago’s School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences. More by Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter

Leave a comment

Join the Conversation Subscribe to Newsroom Pro to unlock commenting on articles. Start your 14-day free trial now or sign in . Please note: All commenters must display their full name to have comments approved. Click here for our full community rules.

Start your day with a curation of our top stories in your inbox.

We've recently sent you an authentication link. Please, check your inbox!

Sign in with a password below, or sign in using your email .

Get a code sent to your email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Enter the code you received via email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Subscribe to our newsletters:

Sign in with your email

Lost your password?

Try a different email

Send another code

Sign in with a password

I agree to Newsroom's Terms and Conditions

- Home Kāinga

- Our Story Ngā Kōrero

- Our Tours Ngā Haerenga

- Wellington Museum Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Space Place Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Nairn Street Cottage

- Cable Car Museum

- Careers Umanga

- What’s On Ngā Kaupapa Whakatairanga

- Museum Blog

- Our Venues Ngā Wāhi

- Venues at Wellington Museum Ngā Wāhi i Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Birthday Parties Ngā Pāti Rā Whānau

- Recommended Caterers Ētahi Kaitaka Kai

- Education Blog Rangitaki Mātauranga

- Space Place

- Wellington Museum

- Space Place Wāhi Haumaru

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Wāhi Haumaru

- Support Us Tautoko

- Museum Blog Te Kāpata Te Curio

Remembering the 81′ Springbok Tour

40 years on, we look back and talk to two Wellington residents who remember those turbulent times.

“All for the sake of a Rugby game. Doesn’t make sense does it?” – Liz Roberts

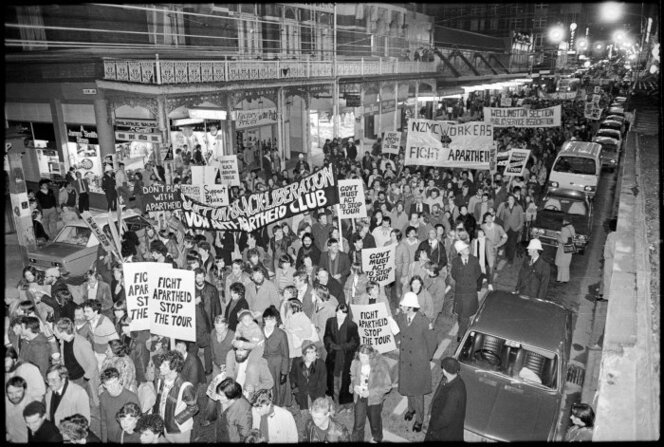

During the winter of 1981, violent clashes between rugby supporters, protesters and the police erupted all over Aotearoa in one of our country’s most tumultuous periods. The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home.

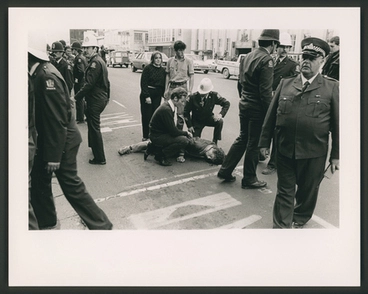

On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa’s Consul to New Zealand.

This was the first time police had used batons against protestors, and the violence horrified many New Zealanders. Former Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s prediction eight years earlier that a tour would result in the ‘greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known’ seemed to ring true.

Wearing helmets like this one, 7000 protesters gathered in central Wellington and around Athletic Park on 29th of August 1981 to stop pro-tour supporters from gaining access to the second test match. Once again the police intervened, this time using long batons, with many protesters injured as a result. This helmet was worn by Anne Bogle during other anti-tour protests.

The Merata Mita Estate permitted us to use the Wellington footage from PATU! (1983) – the powerful documentary directed by Merata Mita which shows the harrowing events of the 1981 Springbok Tour.

Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision meticulously restored and preserved the original documentary for the 40th anniversary. With their approval, we were able to use their newly restored and remastered version for these videos.

Liz Roberts lived on Te Wharepōuri Street in Berhampore, close to Athletic Park, and recalls the events of the 2nd Test on August 29th, 1981, where she saw protesters clash with Police on her street.

Anne Bogle was a young Victoria University student studying Law and History in 1981 – and attended a number of Anti-Tour protests in Wellington – she took part in the protest group that blocked the Wellington Motorway on July 25th and the infamous Molesworth Street incident a few days later on July 29th. The protester helmet she used during the anti-tour demonstrations is currently displayed at Wellington Museum.

Thank you to the Merata Mita Estate for their permission to use parts of the film and also to Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision for their great mahi on the preservation and restoration of this important piece of film taonga .

Also thank you to Anne Bogle and Liz Roberts for sharing their stories.

Pin It on Pinterest

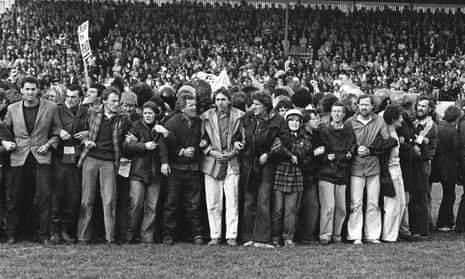

Springbok tour protest at Hamilton, 25 July 1981

A DigitalNZ Story by Zokoroa

On 25 July 1981, anti-tour protesters led to the Springbok - Waikato rugby game being halted in Hamilton

Rugby , Sport , Springbok , Springboks , Hamilton , Anti-tour , Protests. Apartheid , Anti-apartheid , Racism , Anti-racism , HART , Politics

In 1981 the Springbok rugby team toured New Zealand which led to public protests. Those against the tour objected to South Africa's apartheid policies, whilst those supportive of the tour thought politics and sport shouldn't mix. The game against Waikato at Hamilton's Rugby Park on 25 July was called off when several hundred anti-tour demonstrators invaded the field. During the clashes between pro-tour and anti-tour supporters, over fifty arrests were made. The tour also led to debate about racism and the place of Māori in New Zealand.

Two members of St John's College run onto Rugby Park, Hamilton, while two supporters of Springbok Rugby Tour try to stop them, 1981

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

"Confrontation on Centre Field" - 1981 Springbok Tour

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Protesters in Hamilton during a demonstration against the 1981 Springbok tour - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Alexander Turnbull Library

National protests

Protest badges - 1981 Springbok tour

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

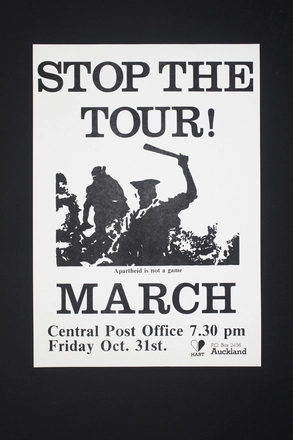

Stop the tour

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

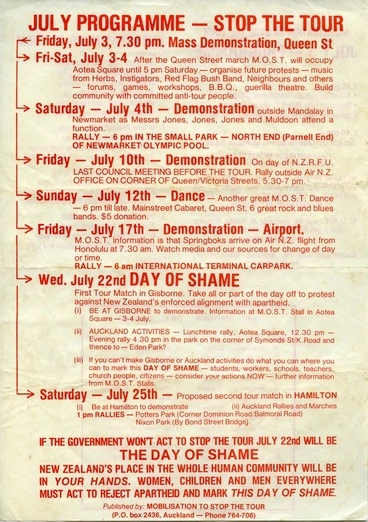

Springbok Tour protest programme

Poster was published by HART (Halt All Racist Tours) and handed out to anti-apartheid activists

Poster, 'The 50 Guilty People'

'No Tour' T-shirt

July petition to PM Robert Muldoon calling for the Springbok rugby team to be refused entry into NZ

Petition Cards to Robert Muldoon

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

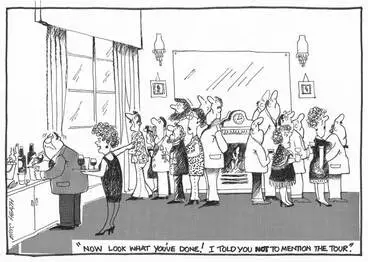

'Don't mention the tour'

Waikato stadium, hamilton: 25 july 1981.

Hamilton's rugby wars - Roadside Stories

Demonstrators Handbook

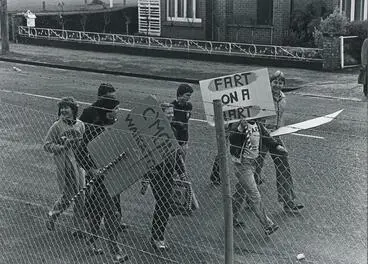

Protestors lined up across road. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Photograph - 1981 Springbok Tour

Members of St John's College before march to Rugby Park against Springbok Rugby Tour, Hamilton, 25 July 1981

![[Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre] Image: [Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2Fcb169b4cfd2233f12df791c5af4ba06bc4470a1d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre]

Photograph – Springbok tour protest

Protesters hold anti-apartheid and anti-racism signs

Fence, Hamilton

Group of protestors middle of rugby field with spectators behind. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Group of protestors including Geoff Chapple in middle of rugby field. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

![[Protesters occupy a rugby pitch] Image: [Protesters occupy a rugby pitch]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F12c490904f98340761e6a8bf5f035e791d6df33d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Protesters occupy a rugby pitch]

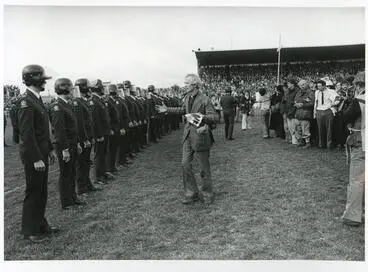

Policemen in riot helmets standing on Rugby Park, Hamilton, during the Springbok rugby tour - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

"Rev. George Armstrong (St. Johns College, Auckland) pleading with Riot Squad" - 1981 Springbok Tour

Line of police confronting protestors. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

"Riot Squad on rugby field" - 1981 Springbok Tour

![[A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton] Image: [A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F40cb0fdb2ef59bfbe1b9e1a93fd27d5ebf48b618%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton]

Police and tour protesters on Rugby Park, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Baton used by two special police squads formed as security escorts for Springboks

PR 24 baton

Protestors and police officers at Rugby Park, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Hamilton, 25 July

Police confronting protestors on rugby field. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Police separating demonstrators & rugby Fans Hamilton.

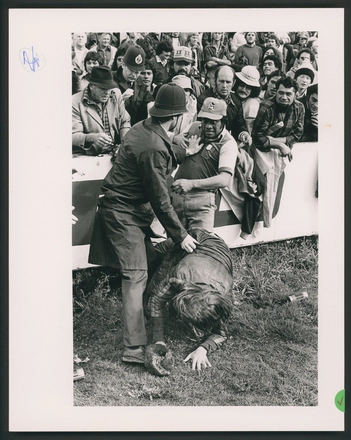

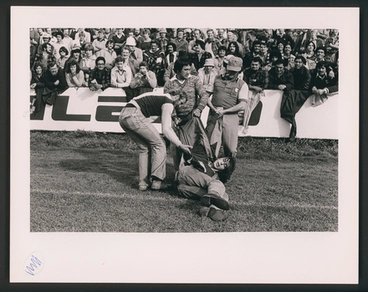

Police struggle with demonstrators, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

Rugby supporters hand a demonstrator off the Field, Hamilton.

A demonstrator lies bloody unconscious in Victoria St, Hamilton.

![[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton] Image: [Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F850aa51c4f15738b036acfa8730c91ebbc69b21d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]

![[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton] Image: [Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F92d515aa64923b96854a7fdfe70fcdde07a4a9d3%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

This calendar was produced in 1982 to raise legal funds for protesters who had been arrested during Springbok tour

Days of Rage calendar

Reaction in south africa.

The Waikato game was the first being televised live back to South Africa, so viewers there saw the NZ opposition to the tour and apartheid.

Try Revolution

NZ On Screen

Bromhead, Peter, 1933- :'Right Jan...you on the vickers..and the other nineteen pick up the bodies...' Auckland Star, 28 July 1981.

1981 springbok captain recalls impact of pitch invasion.

Radio New Zealand

Personal accounts

After the tour, English Department of University of Canterbury placed adverts to gather people's comments & experiences

Springbok Tour Archive [Pro]: Hamilton group on democracy versus communism.

University of Canterbury Library

John Minto, national organiser of Halt All Racist Tours (HART), looks back on the 1981 Springbok tour

John Minto - 1981 Springbok tour

Blazey discussing the 1981 springbok tour, stories told about violence : hamilton during the 1981 springbok tour / by nikita prinsloo.

National Library of New Zealand

Springbok Tour Archive [Anti]: Hamilton woman's note on experience and feelings during the tour.

Springbok tour archive [anti]: coromandells housewife's account of trip to hamilton and repercussions., springbok tour archive [pro]: hamilton person, 60. nz freedoms, protest activity, anti-authority elements., springbok tour archive [anti]: christchurch middle-aged man discussing maoris and racism., springbok tour archive [pro]: a northland woman's views on communism, professional 'stirring', hamilton match, violent protest etc., video / audio.

1981 - A Country at War

Waikato game stopped, 1981

The game that never was

Film: game cancelled in hamilton, 1981 springbok tour, hamilton's rugby wars - roadside stories, report on protests at rugby park.

Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Anti-Springbok-tour veterans on the power of HART

Books / articles.

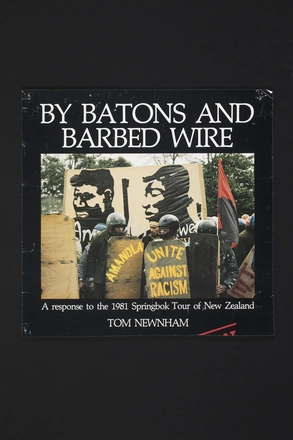

By batons and barbed wire

Roadside stories: hamilton's rugby wars, anti-springbok protesters block hamilton match.

(This DigitalNZ Story was compiled in 2020)

New Zealanders protest against Springbok rugby tour, 1981

Time period, location description, methods in 1st segment, methods in 2nd segment, methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, additional methods (timing unknown), segment length, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was organized in New Zealand in 1969 to protest rugby tours to and from South Africa. Their first protest, in 1970, was intended to prevent the All Blacks, New Zealand’s flagship rugby squad, from playing in South Africa, unless the Apartheid regime would accept a mixed-race team. South Africa relented, and an integrated All Black team toured the country.

Two years later, the Springboks arranged a tour of New Zealand. HART held intensive planning meetings, and, after laying out their nonviolent protest strategies to the New Zealand security director, he was forced to recommend to the government that the Springboks not be allowed in the country. Prime Minister Kirk, though he had promised not to interfere with the tour during his election campaign, canceled the Springbok’s visit, citing what he predicted would be the “greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.”

HART remained active in the anti-apartheid community, continuing to protest the Springboks, and helping to organize a boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The International Olympic Committee had not banned New Zealand after the All Blacks had toured South Africa, and many African countries saw this failure as a tacit endorsement of Apartheid. In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand.

The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival – perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in 1972 was. The government officials could not anticipate, however, that the country was about to fall into “near-civil war.” In response to HART, pro-rugby groups like Stop Politics in Rugby (SPIR) organized in an effort to help the Springbok’s tour succeed. Both sides tended to be easily identified by armbands that made their affiliation clear. In particular, HART activists wore their armbands for the entire length of the tour, subjecting themselves to constant ridicule and the threat of violence, despite their commitment to nonviolent protest only.

The Springboks played their first game on July 22 in Gisborne. An anti-Springbok rally took place that day, near the rugby pitch. When the campaigners arrived at the arena, they were confronted by pro-rugby demonstrators. Because Gisborne, like most cities in New Zealand, was close-knit, demonstrators on both sides knew each other, and were not afraid to call each other out for supporting the wrong side, whichever they believed that was. The pro-rugby demonstrators did not restrict themselves to words, even throwing stones at the other side. The anti-Springbok protesters could not stop the match that day. Though they were able to break through the perimeter fence, and engage the pro-tour demonstrators face to face, they were prevented from occupying the field. Though both sides reported that they were uneasy with the clashes between fellow New Zealanders, neither side was easily swayed.

Three days later, the Springboks were scheduled to play in Hamilton. Anti-Springbok planners had circulated a strategy that would hopefully allow them to tear down the fence, invade the field, and disrupt the match. Protesters had also secured more than 200 official tickets to the match, to make sure that their presence was felt, even in the event that they could not storm the pitch. Despite the presence of more than 500 police officers and a sizable pro-rugby contingent, the anti-Springbok march would prove unstoppable. 5000 anti-Springbok protesters descended upon the Hamilton pitch, and more than 300 made it onto the field, forcing a match cancellation. Protesters chanted that the whole world was watching. Many of the demonstrators were arrested, and those on the pitch endured a constant bombardment of bottles and other objects from rugby fans in the stands. This entire situation was captured on live TV and shown around the world.

With tensions in New Zealand reaching astronomical proportions, the Springboks were next scheduled to play four days later, on July 29. The anti-Springbok protesters were largely absent from the match, but had instead planned a march on the South African consulate in Wellington, New Zealand. Despite police declaring that a march was not permitted, the protesters marched right up to the police line on Molesworth Street. The police began to stop the marchers with their batons, violently forcing them away from the consulate building. The marchers, stunned and bloodied, turned towards the police station, chanting “Shame, shame, shame.” When they arrived, the accosted marchers pressed assault charges on the police that had attacked them. Though the charges were dismissed, the policing of the tour protests had taken a turn for the worse. From this point on, protesters were careful to carry shields and wear crash helmets in order to protect themselves from attacks.

Protests would continue for the entire length of the Springbok’s stay in New Zealand. Only one more match was cancelled, in Timaru. However, there were a few more notable encounters. In Christchurch, on August 15, protesters failed to occupy the pitch in time for the game to be cancelled. The police cordon around the arena held, and several observers believe that the police saved the lives of many protesters. The attacks of rugby supporters were growing more and more violent, The Christchurch incident was characterized by flying blocks of cement and full beer bottles. Had the anti-Bok protesters succeeded in reaching the field, the attacks would certainly have been even more dangerous.

The final match of the tour was in Auckland on September 12. Not only was the match important as a final chance for protesters to demonstrate their opposition to the Springboks, it was the deciding third meeting between the Springboks and the All Blacks. Doug Rollerson of the 1981 All Blacks recalled that it seemed very important for the All Blacks to win the match, to show that a mixed team was superior to the segregated Springbok side. When the All Blacks won, the sense of victory in New Zealand was similar to the US victory over the Soviet Union in 1980 – the triumph of righteousness over the evil empire. However, for most observers around the world, the off-field events were far more important. Though the protesters were generally non-violent, there were many others that joined in the marches – HART characterized them as opportunists that simply wanted to fight with police. Though eruptions of violence had taken place throughout the campaign, they were largely viewed by the protesters as third-party actions, and HART consistently distanced themselves from violent attacks. More memorably, Max Jones and Grant Cole commandeered a prop plane, and proceeded to drop flares and flour bombs on the pitch during play in an attempt to stop the game. Though the game continued, the actions of the protesters were again the primary news story in New Zealand and throughout the world.

Though the anti-Springbok protests were largely unsuccessful in that the vast majority of the planned contests took place, they were able to raise an incredible amount of awareness for the anti-Apartheid movement. Nelson Mandela recalled that when the game in Hamilton was cancelled, it was “as if the sun had come out.” HART would continue protesting until the fall of the Apartheid regime.

Influenced and influenced by anti-Springbok protests in other countries like Australia, Britain (see "Australians campaign against South African rugby tour in protest of apartheid, 1971" and "British Citizens Protest South African Sports Tours (Stop the Seventy Tour), 1969-1970") (1,2).

This campaign was also influenced by the New Zealand Waterfront Strike (1951) (1).

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

Important note about COVID Red Settings:

At Orange our libraries are open with face masks required. Vaccine passes are no longer required. Please stay home if you are unwell. Learn more about visiting our branches at Orange .

Service update:

Miramar Library will reopen at 2pm — maintenance related to last night's stormy weather is now complete. Thank you for your patience.

Service note:

Wadestown Library will close early on Thursday 12 August at 5:30pm for a community meeting.

Wellington City Libraries

Te matapihi ki te ao nui, te haerenga a ngā piringa pāka ki aotearoa i te tau 1981 the 1981 springbok tour of new zealand.

Other heritage topics

- Architecture |

- The sinking of the Wahine |

- Wellington waterfront |

- Earthquakes in Wellington |

- More heritage resources

The rivalry between the Springboks and the All Blacks is one of the longest and most enduring between two sporting nations. In the past, generations of rugby players and enthusiasts from both countries viewed a series victory over the other nation as being the pinnacle of achievement in the sport. Alongside the history of fierce competition went a tradition of hospitality towards the visiting side.

In 1956 and 1965 when the South African rugby team toured New Zealand, they were showered with warmth and generosity wherever they went. Yet 25 years later, the 1981 Springbok tour became one of the most divisive events in New Zealand history.

Its impact went far beyond the rugby ground as communities and families divided and tensions spilled out onto the streets and into the living rooms of the nation. What were the events that made this tour so significant? What motivated ordinary Kiwis to take such extraordinary action against one another?

Although things had been far from perfect between my parents, the Springbok tour caused such tension and stress that we could not live together in the same house and function as a family unit. An example of the increase was when we, as a family, watched the evening news. Often one side would raise their voices in abuse and offensive name calling towards public figures. Later the abuse was turned in an indirect way on individual family members. This was done by blaming the chaos and disruption to rugby games in individual family members, their friends and associations. As the tour went on and the turmoil increased, the negative feelings intensified to such as degree that feelings of dislike, anger and incomprehension dominated our home. It's Just a Game (anon), in, The New Zealand Experience : 100 Vignettes, collected by B. Shaw & K. Broadley, 1985 .

From Digital NZ

Central library closure — collection availability.

Unfortunately much of our heritage collection is currently not available through our online catalogue — because of the closure of the Central Library, much of this collection is in storage. We hope to make it available again soon, but in the meantime, we suggest visiting the National Library of New Zealand in Thorndon (Corner Molesworth & Aitken St) to access these book titles and newspaper resources.

- Visiting the National Library

- Using the National Library Catalogue

Newspaper articles

Unfortunately, contemporary newspaper accounts of the Springbok Tour from 1981 fall into a time period where newspapers are generally not even indexed for searching, let alone available in full text online — see our finding historical Wellington newspaper articles resource.

That being said, information about (and sometimes the full text of) many anniversary accounts (10 years, 20 years later etc.), can be found online (see Online databases below) — and contemporary accounts can be accessed on microfilm if you know approximate dates (we've provided a table of key dates below).

Finding Historical Wellington Newspapers

Tip: Remember that many reports will not appear in newspapers until the following day.

Magazines — online databases

Our online databases can also be used to access a large number of articles about the tour which have previously been published in magazines . Though the databases do not go back as far as 1981, they do contain many retrospective articles written since then.

- Magazine databases

- New Zealand databases

- Newspaper databases

To access contemporary accounts of the Springbok Tour in magazines, we recommend visiting the National Library on Molesworth Street (see collection note above).

To find magazine titles of interest, have a read of the article below:

Story — Magazines and periodicals in New Zealand

Heritage Links (Local History)

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Rugby, racism and the battle for the soul of Aotearoa New Zealand

The Springboks’ tour and the protests that ensued 40 years ago helped set the fight for Māori rights on a stronger path

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand will always have a special place in any narrative about the international fight against apartheid in South Africa.

The protests against the Springboks reverberated around the world – delivering a savage psychological blow to South Africa’s white regime while giving a resounding boost to the oppressed majority.

This weekend marks the 40th anniversary of the first rugby Test of the Springboks’ tour of New Zealand in Christchurch, but well before that game was played, the political significance of the visit had eclipsed any results on the field.

Three weeks before the first Test, the second game of the tour was to be played in Hamilton, and white South Africans in their droves got out of bed in the middle of the night to watch the first ever live telecast of a rugby game in the country.

It was to be a special moment in South Africa, but not as expected. Instead of the Springboks vs Waikato game, fans saw 300 protesters linking arms in the middle of Hamilton’s Rugby Park – declaring they would not leave till the tour had been called off.

The anger that swept through white South Africa was nearly as palpable, if not as physical, as the anger expressed on Hamilton’s streets in the ensuing hours.

On South Africa’s Robben Island, Nelson Mandela was spending his 18th year in jail. He said when the prisoners learned that an anti-apartheid protest had stopped the game, they were jubilant. They grabbed the bars of their cell doors and rattled them around the prison; he said it was like the sun came out.

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, the tour protests also had a profound impact, although this took longer to play out. It was the closest we had come to civil war since the 19th century land wars, but more importantly the tour shone a harsh spotlight on racism in this country. Māori activists asked how could we be concerned about racism 10,000km away and ignore it in our own backyard? Fair question.

In the aftermath of the tour, racism took centre stage with an intense public debate that helped set Aotearoa New Zealand on a new path.

A decade earlier, Māori activist groups like Ngā Tamatoa (the young warriors) had challenged the Pākehā (European) majority about patronising attitudes and lazy racism that meant Māori were in effect second-class citizens.

Politicians are slow followers of public opinion, but four years after the tour and the wide discussion and debate it helped spur, the Waitangi Tribunal was given the responsibility to investigate historic breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi – previously the tribunal had only been mandated to look at possible future breaches. And so began its investigations into our history of racism and oppression and the injustices of colonisation, which continue to resonate for Māori in the present.

Since then numerous positive developments have given a stronger political voice to Māori.

In our most recent budget, the health minister, Andrew Little, announced the formation of a national Māori health authority that will have the power to contract health services for Indigenous New Zealanders where the state system has served them poorly. “By Māori, for Māori” is seen as a way to enhance our democracy with a turn away from the “tyranny of the majority”, under which they have fared poorly.

It’s not all plain sailing though, and recent debate about Māori rights to representation on local councils has met hostile, albeit minority, opposition.

But the direction continues to be forward and work is under way to incorporate the history of colonisation in these South Pacific islands into the school curriculum.

The irony in these positive developments is that the overall situation for most Māori is getting worse, with New Zealand’s Indigenous people disproportionately affected by poverty and inequality, which continues to grow relentlessly with the pandemic.

The civil disruption from the tour and the debate that followed benefited both New Zealand and South Africa in ways that we didn’t see at the time. We are a better country for it.

John Minto was national organiser of Halt All Racist Tours (HART) in 1981 and is currently the national chair of Palestine Solidarity Network Aotearoa.

- New Zealand

- Asia Pacific

- Rugby union

Most viewed

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The 1981 tour was part of a long process that led to this significant change in South Africa, and in this respect, it represented New Zealand's contribution towards a major international development in the closing decades of the 20th century. The anti-apartheid movement in South Africa was buoyed by events in New Zealand.

A short term consequence of the 1981 Springbok Tour Protests was the fact that New Zealand's nation was divided into city and country. The nation was divided for 56 days, tensions grew within families and many friendships greatly suffered as a result of the tour. The country was restricted to rural New Zealand who mainly were pro-rugby, and ...

Read a story about the 1981 Springboks rugby tour. The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand caused social ruptures within communities and families across the country. With the National government backing the tour, protests against apartheid sport turned into confrontations with both police and pro-tour rugby fans — on marches and at matches.

Police officers guarding a barbed wire perimeter around Eden Park near Kingsland railway station.. The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand.The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour ...

Read a story about the 1981 Springboks rugby tour. The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand caused social ruptures within communities and families across the country. With the National government backing the tour, protests against apartheid sport turned into confrontations with both police and pro-tour rugby fans — on marches and at matches.

September 12, 1981 has come to represent the crescendo of the ill-fated Springbok tour. On this day 40 years ago, around 2000 protestors descended on a fortress-like barbed wire-clad Eden Park as the Springboks and All Blacks played a series-deciding final test. Inside the stadium, a light aircraft made low flying swoops over the ground ...

The Springbok Tour. The springbok tour of the 1980's was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the ...

The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home. On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa's ...

In 1981 the Springbok rugby team toured New Zealand which led to public protests. Those against the tour objected to South Africa's apartheid policies, whilst those supportive of the tour thought politics and sport shouldn't mix. The game against Waikato at Hamilton's Rugby Park on 25 July was called off when several hundred anti-tour ...

A country divided — 1981 Springbok Tour. For 56 days in July to September 1981, New Zealanders were divided against each other because of the Springbok rugby tour. Explore our online exhibition of photos and cartoons about the 1981 Springbok tour from the Alexander Turnbull Library collections.

In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand. The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival - perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in ...

Newspaper articles. Unfortunately, contemporary newspaper accounts of the Springbok Tour from 1981 fall into a time period where newspapers are generally not even indexed for searching, let alone available in full text online — see our finding historical Wellington newspaper articles resource.. That being said, information about (and sometimes the full text of) many anniversary accounts (10 ...

The Springboks' tour and the protests that ensued 40 years ago helped set the fight for Māori rights on a stronger path ... The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand will always have a ...

This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand. Due to on-going public interest, including a recent formal request made under the Official Information Act 1982 (OIA) by an historian, the NZSIS has decided it is appropriate to release some of its historical information surrounding the Springbok tour, and is making 10 documents available.

A significant and most clear consequences of the 1981 Springbok tour was the manner in which New Zealand public had been divided. Before the Springboks were even welcomed into New Zealand, Kiwi's never really had the same perspective towards the tour. This left tensions running high in New Zealand's cities, towns and even family living rooms.

NZ Sporting History: The 1981 Springbok Tour. New Zealand continued to play rugby against South Africa through the years of apartheid, and toured over there with a 'white only team'. Then in 1981 the Springbok team were welcomed onto our shores. Audio.

The Tour was a catalyst for Nelson Mandela's freedom and become the first democratically elected state president of his time. One of the most important long term consequences of the Springbok tour protests was tat it helped to bring an end to Apartheid in South Africa, Apartheid wasn't fully abolished until the 90's but many people believe that the Springbok tour protests were a starting ...

Cartoons. Editorial cartoons were able to give voice to the strong opinions and social fallout of a divided nation during the 1981 Springbok Tour and the anti-Sprinbok tour protests. These six cartoonists illustrate some of the differing perspectives, key players, and huge impacts in the lead up to, during, and after the tour.