--------------------------------

What Is Cost Per Visit (CPV) and How To Calculate It?

Sanja trajcheva.

Marketing | May 06, 2023

As a digital marketer, you probably have a whole stack of KPIs that you’re monitoring on a daily basis. So here is another one for you… Cost per visit, or CPV.

Understanding your cost per visit can help you make sense of how much your advertising is costing you in total. It can also help you identify how effective your ad campaigns are and can even help you spot click fraud .

Sounds super useful, right? OK, so first of all, what is CPV?

Table of Contents

What is Cost per Visit?

The cost per visit (CPV) to your site or business looks at how much you’re paying for your advertising and how much a single visit costs.

This can be applied to both website clicks and physical visits or appointments at your location. Generally, it is used to analyze your PPC campaigns, but once you understand how to work out the cost per visit, you can apply it in different ways.

Unlike ROAS (return on ad spend), which focuses on how much it costs to win one customer, CPV looks more at how much you’re paying for an individual visit. It’s a useful way to work out how effective your ad campaigns are across multiple platforms and strategies.

Cost per visit is also not necessarily a metric used by the ad platforms, so you won’t see it in your dashboard. It is, however, quite useful to know if you want to tally up the results of your ad spend.

Do I need to know Cost Per Visit?

Most businesses are using a mixture of advertising methods online, which can include CPC (cost per click), CPA (cost per acquisition), and CPM (cost per thousand impressions).

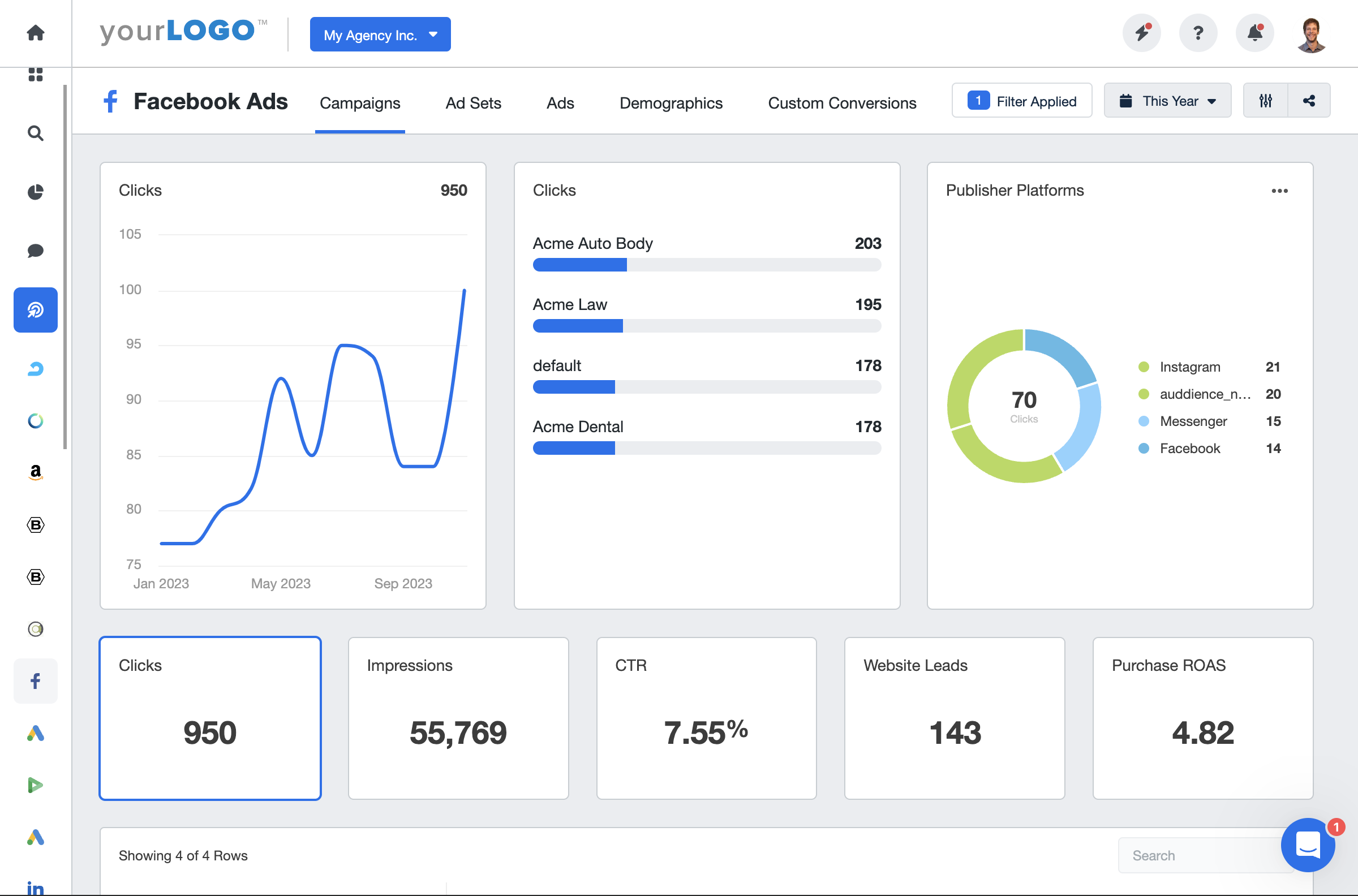

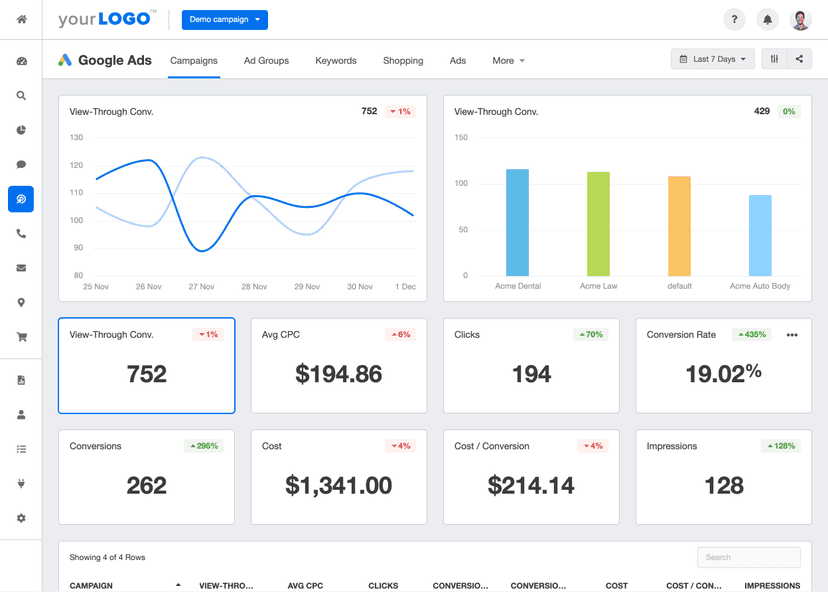

And running digital marketing ad campaigns usually means using multiple platforms. You might be using Google Ads to target the bottom-of-funnel (BoFu) market and sell. But you might be using Facebook Ads to increase site visitors and boost your brand visibility.

If you’ve ever looked at your spreadsheets or advertising dashboards and scratched your head, understanding your cost per visit can help make sense of all of your combined metrics.

How to work out Cost Per Visit (CPV)

Let’s say you want to work out your cost per visit in a weekly period.

The first thing to do is tally up your ad spend on all platforms that you’re using and the clicks or site visits that came from each of them.

As we can see from the chart above, our example business has spent $650 on marketing in a week. From that, there have been 125 site visits.

$650 / 125 visits = 5.2

That makes a total of around $5.20 per site visit.

To calculate cost per visit (CPV):

Total Cost (divided by) Total Visits = Cost Per Visit (CPV)

In this instance, we’re not looking at the CPA or ROAS, which will return different figures.

Now, another way to look at your cost per visit is to look at the total site visits you have in a period and divide that by all of your marketing efforts. This might also include the time spent to create organic content, the costs of any freelancers or agencies you’re using to do keyword research or manage your ads, and even the software you pay for to help you do the job.

This might look something like:

- Paid ad spend $650

- In-house marketing team $300

- Freelance contributor $150

- Software package $25

And let’s say you have 800 unique views on your site per week from all sources, including organic, paid search, and your paid social campaigns.

$1125 / 800 = $1.40 per visit

Understanding CPV

With the cost per visit, you can then apply your cost per acquisition or return on ad spend and see where your marketing efforts are most successful.

Of course, those organic results might not seem the most cost-effective in the short term, but they are probably (or should be) part of your overall content marketing strategy.

When looking at your paid search results, you can investigate how effective your PPC ads are at attracting the right kind of site visitors. Looking at that cost per visitor, you can then analyze things like:

- Time spent on site or bounce rate

- Pages viewed

- Average spend per customer

- Lifetime value of a customer

- How PPC fares as a percentage of your marketing spend

What’s in a click?

Each click has a value, even if it’s from an organic source. At some point, you’ve paid money or spent your time (which also has value, right?) to create a clickable resource.

Eventually, with some good marketing strategy, the bulk of your sales and site visitors should come from organic search results. Although not ‘free’ traffic (again, you have paid for it), it doesn’t cost per click or per view.

But pay-per-click is still one of the most effective ways of driving traffic to your business and getting on top of the SERPs.

When it comes to clicks on paid search ads, the issues of click fraud and ad fraud become key. Of those site visitors, how many of them are not genuine potential customers?

Understanding how much click bots or malicious business competitors can cost your business can be an eye-opener for many business owners.

According to research from the University of Baltimore, the volume of click fraud averages around 14% globally. And from our own data, we’ve seen this rising to over 60% for some particularly competitive industries.

Yes, that means that 60% of paid clicks on some ad campaigns are not even real customers (or even people), which in many cases also means a higher cost per visit (CPV).

Check out how much fraudulent traffic there is on your PPC ads with the free trial of our industry-leading anti-click fraud software.

As an experienced content writer, Sanja is a firm believer in the power of storytelling to inspire and educate audiences. In her role at CHEQ, Sanja fearlessly tackles the challenges of the fake web – navigating through fake traffic, ad fraud, and click fraud. When not writing, she enjoys exploring new tastes and planning her next adventures.

Related articles

Unveiling the state of fake traffic 2024: insights, trends, and solutions, the bad actors awards: celebrating the most disruptive bots.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Recommended articles.

How Retailers Can Use Holiday Shopping Findings to Fuel Growth in 2024

Latest posts.

What is Click Fraud? How it Works, Examples, and Red Flags

Price Scraping Exposed: Who is at Risk and How to Prevent it?

Top 7 Ways to Detect Account Takeover Fraud

OTP Bots: The Achilles’ Heel of Your Digital Defense

How to target bottom of funnel customers with PPC content

Webinar Recap: How Junk Leads Impact Revenue Teams

How Bots and Bad Actors Bypass Web Application Firewalls (WAFs)

Don’t Fall Victim: How to Detect Bot Attack on Your Website

Comparing reCAPTCHA and hCAPTCHA: Are CAPTCHA still worth it?

Block invalid traffic with cheq essentials.

- rankingCoach 360 includes:

- Local Marketing Get found locally

- Google Ads More visitors today

- Search Engine Optimization (SEO) Reach the top of Google

- Reputation management Be at one with your customers

- Social Media Monitoring Track the latest news

- Brand Monitoring Check your presence all over the web

- Features overview

- Local Marketing

- Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

- Reputation management

- Social Media Monitoring

- Brand Monitoring

Cost Per Visit (CPV)

What is cost per visit (cpv).

The term cost per visit is pretty self-explanatory. It means the amount of money you’re paying for an ad and how much a single visit to your web page (through that ad) will cost you.

It can be relevant to both website clicks and physical visits or appointments at your location. However, it’s mainly used to analyze digital PPC (pay-per-click) marketing campaigns and help you understand your ads’ reach and influence.

When looking at your paid search results, you can determine how effective your PPC ads are at attracting the right audience. Looking at that cost per visit, you can then analyze variables such as:

- Bounce rate

- Pages viewed

- Average spend per customer

- The lifetime value of a customer

And learning about these factors can significantly help you in improving your ads and your website. But before that, let’s take a look at how we can calculate the cost per visit.

How to Calculate Cost Per Visit

Let’s say you want to calculate your cost per visit for one week.

The first thing to do is add up your ad spend on all platforms you’ve used in the last week and the site visits or clicks that came from each of them.

So, for example, let’s suppose that a business has spent $450 on marketing in a week. And as a result of investing that money, there have been 125 site visits.

$450 / 125 visits = 3.6

That makes a total of around $3.60 per site visit.

Meanwhile, another way to perceive cost per visit is to divide all your marketing efforts by the number of total site visits you might’ve received in a certain period.

It would include the costs of any freelancers or agencies you might’ve used to conduct keyword research or manage your ads, the time you spent to build organic content, and even the software you pay for to help you do the job.

In the end, it might look something like this:

- Money spent on ads $450

- In-house marketing team $300

- Freelance contributions $260

- Software used in the process $35

And let’s suppose your site had 800 unique views per week from all sources, including organic, paid search, and your paid social campaigns.

The final result would be: $1045 / 800 = $1.30 per visit

Why Is Cost Per Visit Important?

Each click on a web page or advertisement has value, even if it’s from an organic source. Remember that you’ve invested time and money to create spaces that will link to your site and increase your page visits. So, the money you’ve spent should be converting into sales for your business. Otherwise, there’s no point in running paid ads.

Key Takeaway

Overall, cost per visit can be an effective method to help you determine what works and what doesn’t for your digital marketing strategy. If you can calculate and then analyze the figures, you can then determine which ads might be costing you the most and whether your money is being well spent.

- Credit cards

- View all credit cards

- Banking guide

- Loans guide

- Insurance guide

- Personal finance

- View all personal finance

- Small business

- Small business guide

- View all taxes

You’re our first priority. Every time.

We believe everyone should be able to make financial decisions with confidence. And while our site doesn’t feature every company or financial product available on the market, we’re proud that the guidance we offer, the information we provide and the tools we create are objective, independent, straightforward — and free.

So how do we make money? Our partners compensate us. This may influence which products we review and write about (and where those products appear on the site), but it in no way affects our recommendations or advice, which are grounded in thousands of hours of research. Our partners cannot pay us to guarantee favorable reviews of their products or services. Here is a list of our partners .

Understanding Copays, Coinsurance and Deductibles

Many or all of the products featured here are from our partners who compensate us. This influences which products we write about and where and how the product appears on a page. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money .

Coinsurance, copays and deductibles are different out-of-pocket costs for health care, and being familiar with these terms can help you better understand your health coverage and costs. Even after you pay monthly premiums for health insurance , out-of-pocket costs can lead to high medical bills if you get sick or injured.

Here's how health insurance costs work.

Defining some health insurance terms

Before understanding how it all works together, let's brush up on some common health insurance terms.

Coinsurance

Coinsurance is a percentage of a medical charge you pay, with the rest paid by your health insurance plan, which typically applies after your deductible has been met. For example, if you have 20% coinsurance, you pay 20% of each medical bill, and your health insurance will cover 80%.

A copay, or copayment , is a predetermined rate you pay for health care services at the time of care. For example, you may have a $25 copay every time you see your primary care physician, a $10 copay for each monthly medication and a $250 copay for an emergency room visit.

The deductible is how much you pay before your health insurance starts to cover a larger portion of your bills. In general, if you have a $1,000 deductible, you must pay $1,000 for your care out of pocket before your insurer starts covering a higher portion of costs. The deductible resets yearly.

The premium is the monthly payment you make to have health insurance.

You pay the premium each month like a gym membership, even if you don't use the coverage. If you don't pay the premium, you may lose your insurance. If you're fortunate enough to have employer-provided insurance, the company typically picks up part of the premium.

Out-of-pocket maximum

The out-of-pocket maximum is the limit of what you'll pay in one year, out of pocket, for your covered health care before your insurance covers 100% of the bill. The maximum out-of-pocket limit for marketplace health plans (those on the Affordable Care Act health insurance marketplace) is $9,450 for an individual and $18,900 for a family in 2024 . (This amount doesn't include what you spend for services your insurance doesn't cover.)

Coinsurance vs. copay

Copays and coinsurance are different ways your health insurance may require you to pay for covered services. Here are the differences:

Copay vs. deductible

Your health plan may have both copays and deductibles, and whether you pay one or the other may depend on the services you receive. For some services, such as a visit to your primary care doctor, you may owe a fixed copay, such as $10 or $20. For other services, such as an MRI, you may have to pay the approved cost of the service up to your deductible.

Your copay may count toward your deductible, but it doesn't always. And you may owe copays for some services after you meet your deductible.

Coinsurance vs. deductible

Deductibles and coinsurance work together, but usually consecutively. As mentioned, the deductible is the amount you pay before your insurance starts covering the cost of your health care. Once you meet your deductible, you'll typically owe coinsurance (such as 20% of approved charges) on all additional services for the rest of the year.

You'll pay coinsurance on approved medical care until you hit the out-of-pocket maximum on your plan, after which your insurance will cover 100% of the rest of your care for the year.

How it all works together

Health insurance policies can have a variety of cost-sharing options. For example, some policies have low premiums, high deductibles and high maximum out-of-pocket limits, while others have high premiums, lower deductibles and lower max out-of-pocket limits.

In general, it works like this: You pay a monthly premium to have health insurance. Then, when you go to the doctor or the hospital, you pay either full cost for the services or copays as outlined in your policy. Once the total amount you pay for services, not including copays, adds up to your deductible amount in a year, your insurer starts paying a more significant chunk of your medical bills, commonly 80%. The remaining percentage that you pay is called coinsurance.

You'll continue to pay copays or coinsurance until you've reached the out-of-pocket maximum for your policy. At that time, your insurer will start paying 100% of your medical bills until the policy year ends or you switch insurance plans.

The catch: Your health plan's network

Here's the snag: The co-sharing scenario highlighted above works only if you choose doctors, clinics and hospitals within your health plan's provider network. If you use an out-of-network doctor, you could be on the hook for the whole bill, depending on which type of policy you have. This brings us to two related terms:

This is the group of doctors and providers who agree to accept your health insurance. Health insurers negotiate lower rates for care with the doctors, hospitals and clinics in their networks. So when you go in-network, your bills will typically be cheaper, and the costs will count toward your deductible and out-of-pocket maximum.

Out of network

A provider your insurance plan hasn't negotiated a discounted rate with is considered out of network. If you get care from an out-of-network provider, you may have to pay the entire bill yourself, or just a portion, as indicated in your insurance policy summary.

» MORE: What the No Surprises Act means for your medical bills

Doing the math on copays, coinsurance and deductibles

To illustrate with an example, consider a person — let's call her Prudence — who needs some health services. (Your costs would be different based on your policy, so you'll want to do your own calculations.)

Prudence's policy:

Insurance coverage: Single.

Annual deductible: $1,200.

Copays: $20 per office visit, $50 per specialist, $100 per ER visit; these don't count toward her deductible.

Coinsurance: 20% after she meets her deductible.

Scenario: Doctor visits and an MRI

Prudence goes in for an annual checkup. Because she goes to an in-network provider, this is a free preventive care visit. (If it had been an office visit for a medical issue, there would have been a $20 copay.) However, her primary care physician thinks Prudence should see an orthopedist based on her physical exam. The orthopedist later recommends an MRI.

Copays for an in-network specialist on her plan are $50. The MRI provider is in her insurer's network, and the approved insurance charge is $1,000 for the MRI, including the radiologist fees for interpreting the scan.

Imaging scans like this are "subject to deductible" under Prudence's policy, so she must pay for it herself, or out of pocket, because she hasn't met her deductible yet.

Total out-of-pocket costs: $50 for the specialist copay + $1,000 for the scan = $1,050.

Scenario: Trip to the ER

Later that year, Prudence falls while hiking and hurts her wrist. She heads to an in-network emergency room, for which she has a $100 copay. After the copay, ER charges are $3,400. Her deductible will be applied next.

Prudence has already paid $1,000 of her $1,200 deductible for her MRI, so she's responsible for $200 of the ER bill before her insurer pays a larger share. Of the remaining $3,200, her health plan will pay 80%, leaving Prudence with a 20% coinsurance of $640.

Total out-of-pocket costs: $100 for the ER copay + $200 for remaining deductible + 20% coinsurance ($640) = $940.

Prudence has now paid $1,990 toward her medical costs this year, not including premiums. She has also met her annual deductible, so if she needs care again, she'll pay only copays and 20% of her medical bills (coinsurance) until she reaches the out-of-pocket maximum on her plan.

Understanding how your health insurance works can save you money and grief now and down the road.

On a similar note...

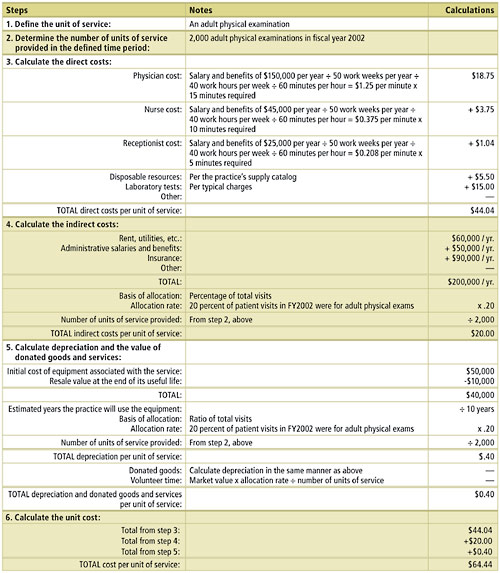

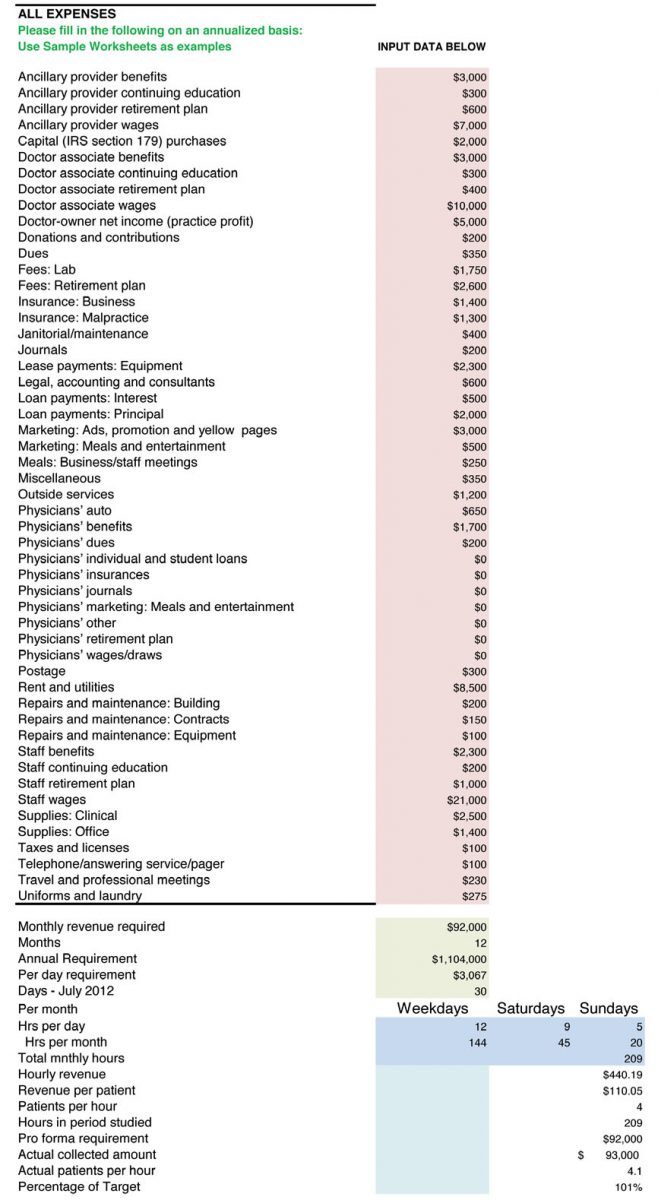

Do you know what it costs your practice to provide an adult physical, a well-child exam or an office procedure? A “unit cost analysis” will tell you that and more .

JEFF KULLGREN, MPH, AND MARIA D. SIBELLA, MA

Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(4):41-45

A unit cost analysis is one of the most useful yet underused tools for managing a family practice. It takes into account all of the resources associated with providing a particular service and calculates how much it costs to provide that service at the smallest practical unit. 1 – 3 For example, you might want to know the true cost of providing an adult physical exam, a well-child visit or a particular procedure.

Cost-per-unit data can be highly useful to you when developing budgets, setting fees, planning for expansion or negotiating rates with health care insurers. You may find, for example, that the true cost of providing an adult physical exam is significantly higher than the current reimbursement rate of a local health plan. You might then be able to use the data to negotiate a higher reimbursement rate, or at least decide whether the contract is worth renewing. Similarly, you may find that the costs of doing a certain procedure make it unprofitable given the level of reimbursement and the demand for the procedure.

In our recent experience at a medium-sized community health center in the Midwest, the unit cost analysis proved to be an insightful tool. It showed us, for example, that our laboratory expenses for patients with HIV account for about half of the cost of each of their medical visits. When this information was shared with a funding agency, it decided to increase its financial support of the clinic. The analysis also provided a foundation for further inquiries, including a time study of patient and staff work flow that will be used to improve the clinic’s efficiency.

While most physicians would agree on the theoretical utility of unit cost information, they might doubt the practicality of actually performing a unit cost analysis, fearing that it requires vast and expensive resources such as consultants, sophisticated computer systems or accounting training. Fortunately, these elements are not needed to conduct a unit cost analysis. By following the steps provided below, you can acquire valid and actionable cost information about the care you provide regardless of practice size or resources.

Knowing the costs of your services can help you with setting fees, planning for the future and negotiating better rates with health plans.

A unit cost analysis does not require sophisticated computer systems or accounting training.

Family physicians can use a unit cost analysis to determine the true cost of providing an adult physical exam, a well-child visit, a particular procedure, etc.

Six steps to a unit cost analysis

Unit cost analysis is fairly straightforward. The most important thing to remember is that you can and should modify the methodology where necessary for your organization. In doing so, bear in mind that you are not striving to produce a publishable analysis that will stand up under peer review. Instead, you are simply trying to obtain accurate cost information that will enable sound management decisions.

The sample unit cost analysis provided in this article will help illustrate how each of these steps can be applied in the real world. Both the example and this article take a “bottom up” approach (that is, you start by determining all of the individual costs associated with a unit of service and then add them together to determine the cost per unit). Practices with more sophisticated information management systems may be able to take a “top down” approach (that is, you start with the total costs associated with a service and then divide by the number of units of service provided to determine the cost per unit). Each of these methods will lead to the same destination (the cost per unit); they simply have different ways of getting there.

Step 1: Define the unit of service. The first step in a unit cost analysis is to identify the type of service whose cost you want to know. Common units of service are office visits, adult physicals, diabetes check-ups, well-child exams, etc. How you define a unit of a given service should be based on what is meaningful, familiar and useful to your practice. Your staff, for example, may be used to thinking about office visits in 15-minute intervals. This definition will be important when you begin to figure the costs of physician time, nurse time and support staff time associated with the service. Using familiar definitions will make it easier to acquire information, communicate findings with your staff and translate your results into action.

Another consideration in choosing and defining your units of service is your information management system. If your units of service correspond with data already captured by your computer system, it will be easier for you to find the data you need and analyze your practice’s costs. For example, if your computer system tracks claims better than visits, you might choose to calculate the costs of preventive medicine services coded 99381 to 99429.

Units of service can be further segmented, as needed, to provide more detailed cost data about particular types of patients. Patients for whom English is a second language, for example, may require the presence of an interpreter during their regular office visits as well as extra time with their physician. Likewise, patients being treated for chronic diseases may require more time with the physician, more lab tests or more nurse time devoted to patient education. By breaking down your units of service into these smaller components, you can identify costs that might be missed by looking at only the average costs of all patients.

Step 2: Determine the number of units of service provided. In determining the number of units provided, you will need to choose a time period to analyze and must adhere to this period throughout your analysis. Practices with a computerized practice management system should be able to produce the number of units of a particular service provided during a given time period fairly easily. Practices without a computerized system can use a basic chart audit to produce a reasonable estimate. Again, the goal is to acquire the most valid and reliable information available with the staff time and resources available.

Step 3: Calculate the direct costs. Direct costs are expenses you can easily relate to the provision of a specific service. Examples of direct costs include physician and support staff salaries and benefits, medical supplies, lab tests and other resources consumed at the time of the service. Unit costs are likely to be more sensitive to direct costs than any other component of the analysis, so a careful and detailed approach is crucial.

The largest and most important direct cost is often the physician time allocated to one unit of service. This component can be determined through one or a combination of four methods: 1) direct observation of physician activities; 2) time sheets or time diaries that physicians fill out; 3) time sheets or time diaries that patients fill out; or 4) patient cycle times (from check-in to checkout) generated from a practice management system. Support staff time can be determined similarly. For example, by keeping a time diary for one week, a physician may find that he spends an average of eight minutes in the exam room with the typical adult patient. Using his salary or hourly wage as a reference, the physician could then determine his cost for those eight minutes. (See step three of the example .)

Cost information for other resources – such as materials, supplies and laboratory tests – that are consumed during a particular service can be obtained through several different approaches as well. Often a discussion with the physicians or staff familiar with the resources used to provide the service will be sufficient. Reviews of invoices and budgets for the time period or direct observation can also be helpful in tallying the resources directly consumed. For example, to determine the resources associated with a typical office visit, your nurse might simply make a list of the items commonly used and consult the practice’s supply catalog to determine their costs.

Step 4: Calculate the indirect costs. Indirect costs are expenses shared by more than one area of the practice. These costs involve resources that are not directly consumed during the provision of a service, but without them the provision of that service would not be possible. Common examples include administrative staff salaries and benefits, facility costs, insurance premiums, office equipment and supplies, and marketing expenses.

To calculate the indirect costs associated with a particular service, begin by making a list of all indirect costs within the practice (e.g., rent and utilities = $60,000 per year; administrative salaries and benefits = $50,000 per year; malpractice and general liability insurance = $90,000 per year). Then, total these indirect costs (e.g., $200,000 per year). Next, decide how much of the practice’s indirect costs should be allocated to the service in question. Common bases for allocation include the ratio of the selected service to all services provided, the percentage of total revenue attributed to the service, the percentage of practice square-footage devoted to the service, or the percentage of the organization’s total direct costs attributed to the service. For example, the fact that 20 percent of a practice’s visits are adult physical exams can be used as a rationale for attributing 20 percent of the practice’s indirect costs to adult physical exams. (See step four of the example .) Often, more than one potential basis for assigning indirect costs will suggest themselves. In such cases you’ll simply want to decide which one makes the most sense for your practice as a whole.

Step 5: Calculate depreciation and the value of donated goods and services. Before you can figure the full cost of providing the service in question, you must incorporate estimates for depreciation and the value of any donated goods or services. Overlooking these expenses may lead you to underestimate long-term expenses, and it may impede long-range planning. “Straight line depreciation” is one generally accepted – and perhaps the most straightforward – way of calculating this cost. Take the initial cost of the equipment and subtract its estimated resale value at the end of its useful life (e.g, $50,000 - $10,000 = $40,000). Divide this number by the years you expect your practice to use the equipment (e.g., $40,000 ÷ 10 years = $4,000). Using a cost allocation similar to the one used in step 4, determine the amount of depreciation attributable to the service (e.g., $4,000 x .20 = $800). Divide this number by the number of units of service provided in the study time period to arrive at a depreciation cost per unit of service (e.g., $800 ÷ 2,000 adult physical exams per year = $0.40 per adult physical exam).

Some clinics also rely on the use of donated goods or volunteer services, and the market value of these items (i.e., the amount you would have had to pay to acquire the donated goods or services) should be included in your cost calculations. Since these resources may not always be available to a practice, the costs of replacing them to maintain current service levels can be significant. Documenting the financial importance of these donations can also be valuable for organizational fundraising and planning.

To calculate depreciation for donated goods, use the formula described above for depreciation of non-donated equipment. To calculate the cost of donated services, multiply the market value of the services by the allocation rate, and then divide by the number of units of service provided (e.g., $10,000 x .20 ÷ 2,000 adult physical exams provided per year = $1.00 per unit of service).

Step 6: Determine the full cost of the unit of service. This final step is the simplest: Add the costs from steps 3, 4 and 5 to arrive at a total cost per unit of service. In the example , the final cost for an adult physical examination was $64.44.

AN EXAMPLE: CALCULATING THE COST OF PROVIDING AN ADULT PHYSICAL EXAM

Family physicians in a two-person practice would like to know the true cost of providing an adult physical exam in their office. The practice wants to determine whether a private insurer is compensating them adequately and whether they should try to negotiate a better reimbursement rate.

Using data for fiscal year 2002, the physicians completed the following unit cost analysis. The practice also kept time diaries for one week to determine the physician and staff time required for an average adult physical examination.

In the end, the physicians found that an average adult physical examination costs $64.44.

Lessons learned

As family medicine continues to be practiced in a financially hostile health care environment, the need for accurate and actionable cost data has never been greater and will only increase in the future. A unit cost analysis can reliably yield this information and is a valuable tool for any family practice seeking to improve its management, efficiency and planning. By using an effective but realistic approach based on the six steps listed in this article, even the most resource-poor organizations can design and conduct a unit cost analysis that will help managers make the sound decisions needed not only to survive – but to succeed – within this environment.

Health Resources and Services Administration. Determining the Unit Cost of Services: A Guide for Estimating the Cost of Services Funded by the Ryan White CARE Act of 1990 . Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 1993.

Yates BT. Analyzing Costs, Procedures, Processes and Outcomes in Human Services . Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1996.

Zelman WN. Cost per unit of service. Evaluation and Program Planning . 1987;10:201-207.

Continue Reading

More in fpm, more in pubmed.

Copyright © 2004 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Journal of Urgent Care Medicine

Practice Management

Understanding Your Cost Per Patient

Urgent message: Assessing the true cost per patient is key to determining which pricing model will generate the most revenue for an urgent care center.

JORDAN TODD RICE, MD A cost-per-patient analysis may not work for every urgent care center owner, but this article is intended to give JUCM readers the basic tools they need to understand the formulas. It can also serve as a baseline for discussions with urgent care center staff, executives, managers, clinicians, and owners.

The goal of the exercise is to help urgent care providers better understand key elements of patient costs so they can determine which pricing model will best serve their organizations, be they for-profit, nonprofit, a single urgent care center or a practice with multiple locations.

How do operators of urgent care centers truly break down the cost for providing care to a single patient for primary care, urgent care or Workers’ Compensation services?

- How can the operator of an urgent care center do a true cost/benefit analysis to find out if it makes sense to switch to a single payment from payors rather than traditional fee-for-service reimbursement?

- How can and will paperless and digital systems affect the answers to the previous two questions?

Overcoming Accounting Obstacles One of the biggest challenges in calculating cost per patient is getting information from an urgent care center’s accounting and practice management systems. This is the most difficult task because such systems are great for generating information about pricing and revenue but not set up to provide costs, unless the Relative Value Unit (RVU) option is switched on. Some providers thought that the advent of all-in-one systems and single databases combing practice management (billing, scheduling, claims follow-up, etc.) and an electronic medical record would make the task easy to accomplish. In fact, automation helps practices do better charge capture, speeds up patient visits (after the normal 3- to 6-month learning curve for the switch from paper to paperless) and may even automate coding. It does not, however, compute the true cost per patient.

The other obstacle is the accounting program. Virtually every transaction in every category can be seen in an urgent care practice’s Chart of Accounts, but calculating the cost of each transaction is not as easy as you might think. For example, if your practice has a 401 (k) plan or your employees pay a portion of their health insurance, is that a true “cost” that needs to be factored into the computation of average cost?

Finally, an urgent care practice must be able to differentiate types of payors and services. For example, if your practice is a hybrid that provides both primary care and urgent care services, payors typically pay the same amount regardless of the type of visit. The main differentiators for most states and payors are factors such as the type of provider (some payors discount a physician extender visit by as much as 15%), use of “s” codes for a particular facility (fee-for-service or global fee) and whether a service was rendered “after hours” compared with the hours of an average practice. All of these factors affect reimbursement and cost, assuming that physician extenders are paid less than MDs and DOs. Even the place of service can affect reimbursement, but it usually does not impact cost. The same is true for treating Workers’ Compensation cases or providing occupational medicine services. The reimbursement levels may be higher or lower than those for a non-work-related injury, but the cost should be relatively similar for treating a 10-cm laceration, an aggravated left ankle sprain, or carpal tunnel syndrome, which is now becoming more and more common outside of the workplace because of the advent of home computers, pads, tablets, and even smartphones.

Thus we need to focus on cost only and in this case we will look across the board. Table 1 is a typical chart of accounts for an urgent care practice by category.

Your urgent care practice may have more or less accounts, but the ones listed are typical whether you have one office or 50.

For simplicity, let’s assume that for June 2011, the total for the accounts shown in Table 1 was $100,000. In a very unsophisticated model, we would simply take the number of patients for the month and divide that into $100,000 to get the cost per patient. If the practice saw 50 patients per day for 30 days in June, the total number of patients seen that month would have been 1,500. The cost per patient, then, would be $66.66 ($100,000 divided by 1,500). Net revenue of $120,000 from the 1,500 patients (understanding that most billings would be collected in June, some in July, and the remainder in August) would result in net profit of $20,000.

The collected amount per patient would be $80 and the profit per patient, in our simplistic model, would be $14.34. Continuing with our simplistic example, if a payor were to offer the practice a global fee of $90 per patient, which would typically encompass all services, including on-site laboratory, x-ray, electrocardiography (ECG), spirometry and most other patient costs, the practice would then receive a profit of $24.34 per patient. That is one reason that practices receiving global fees use digital technology for x-rays, ECG, and spirometry and send most laboratory work out to be processed. There are also savings to be had on the billing and collection side because global fees don’t get rejected, don’t have to be re-filed, and co-pays are received at the time of service, so there is little patient follow-up in terms of collections.

Real-World Complications Why, then, do simple cost-per-patient calculations not work in the real world? The factors involved are myriad, some which we’ve already discussed. One issue is how payroll is processed. In a traditional medical model, employees and clinicians are paid every 2 weeks. Some urgent care practices pay employees weekly, whereas others pay twice a month, and others even pay clinicians daily.

Clearly, when employees are paid every 2 weeks, there will be three pay periods in several months every year, which skews costs tremendously. Also, many insurance premiums are paid quarterly, semi-annually or even annually. That, too, affects month-to-month costs. Other factors include benefits payments, such as 401 (k) or retirement contributions, which may happen every pay period, monthly, or annually. Utility, water, sewer, and other costs also fluctuate from month to month. In Maine and Oregon, heating costs may sky rocket in mid-winter, whereas Arizona and Florida may have high cooling costs from mid-spring to mid-fall. Water and sewer costs tend to fluctuate less, but even they can go up and down. Therefore, it might make sense to do computations for your urgent care practice using quarterly, semi-annually, or even annual numbers.

If our model urgent care center has $1.2 million in true costs and 18,000 patients, the cost per patient would be the same: $66.66. But what if the center’s costs were actually $1.4 million and it had only 17,000 patients? Now the cost zooms to $82.35 per patient. Conversely, if the center only had $1 million in costs and 20,000 patients, the cost per patient would be only $50. Again, ANY additional revenues above this would be profits (or surplus for non-profit urgent care centers).

Now, let’s do some addition and subtraction from revenues for your urgent care center. Do you sell products for weight loss or durable medical equipment, or do your physicians dispense drugs? If so, those services usually are not paid by fee-for-services or global contracts. Laboratory services and x-rays typically are included in a global fee, but they usually are separate fees for a payor. Do you bill separately for them? The same question applies to Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System items, which are reimbursed and may be a “carve out” paid in addition to a global fee, depending on the individual contract. Cash-only services such as allergy testing, home sleep studies (elective), Holter or event monitoring are revenue. But their costs should be separated from the equation to compare fee-for-service and global fees and truly understand your actual cost per patient.

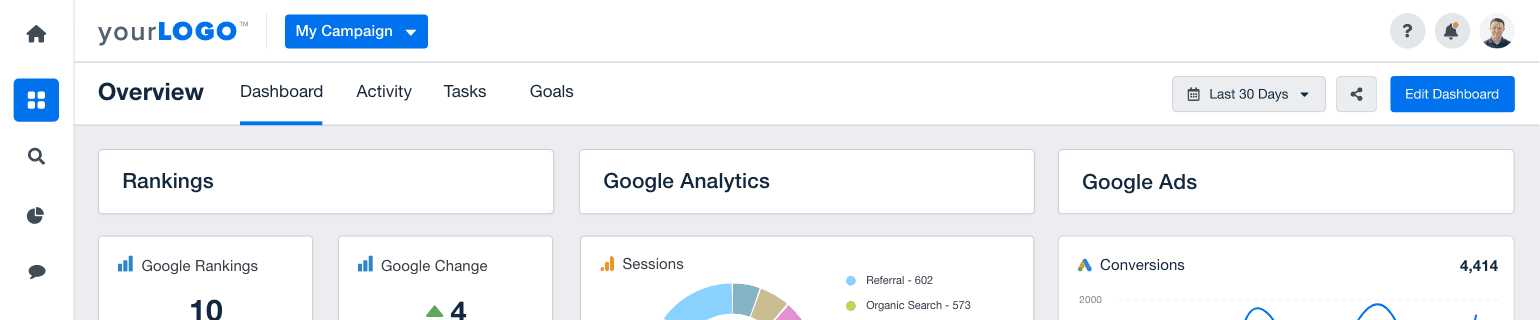

Understanding a Cost Benefit Analysis Spreadsheet Next, let’s look at how a cost benefit analysis spreadsheet works. A typical one that includes all costs is available in the Resources section of UCA’s Members Only portal, Uconnect (http://uconnect.ucaoa.org), and can be downloaded for free. A screenshot of what typical data entry looks like is shown in Figure 1.

Please note that annualized numbers were used in our example for the reasons we previously mentioned. There are too many expenses that are not paid on a monthly basis, and payroll can skew the numbers from month to month. What is key is to understand that each provider uses different resources, some of which are reimbursed and some are not. Once again, x-rays could be a profitable venture, but you have to understand the true cost of each x-ray. What is the cost of the unit? Is it leased or purchased? How much developer or fixer does it take if you use plain film for 100 or 1,000 x-rays? Is there a maintenance contract on the development unit? How about on the x-ray tube and collimator?

What cost benefit analysis does is permit the operator of an urgent care center operator to know the exact cost per x-ray, based on ALL costs against ALL revenues. In fact, I have worked with owners of urgent care centers who insisted they made money with a particular payor on a three-view ankle x-ray. But when we looked at all costs, including the cost for the room (rented or owned facility), personnel and over-reads if required, many times those x-rays were costing money not producing revenue. Even digital units have costs associated with them other than just the lease or amortized purchase price, such as the price of replacement cassettes, DVDs, maintenance, and replacement tubes.

The Impact of Variation in Reimbursement The hardest part of determining cost per patient is factoring into the equation varying reimbursements. Unless your urgent care center accepts cash only, you may be receiving 100 different reimbursements for a three-view ankle x-ray. Medicare, Medicaid, Indian Health Service, Tri-Care and some Federally Qualified Health Center fees are all under the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) umbrella, but each will have a different reimbursement level. And even that number can be affected by the clinician on duty and whether that individual was a physician extender or a physician, for whom discounts of between 10% and 15% might apply. Figure 2 illustrates this computation, focusing on one insurance company.

For our example, we used fictitious numbers and a fictitious payor and chose an arbitrary reimbursement of $35 for a three-view ankle x-ray for Delta employee. From there, we included all costs involved with taking three x-rays. Note that we added every possible cost. Most are inputted as an annual cost and then we worked backward to the cost per x-ray. We can do this working off the annual number or the monthly number. The spreadsheet includes ALL costs for the facility and takes into consideration the total amount of space for x-rays, including the development room, x-ray storage, x-ray room, and operator area. If you pay for over-reads and they are not reimbursed separately or directly by a payor, then that needs to be included. We added all costs associated with the x-ray unit (assuming a lease, in this case), such as maintenance, fixer, developer, film, and any other direct costs. We also added in 15% (every center will be different) for billing and administration to collect and bill for the service. So, after looking at our sample $35 payment and subtracting these expenses, we came out with a profit of $1.64 per three-view ankle x-ray for this particular insurance company.

The same cost can be used when negotiating global fees. You simply need to look at the total number of x-rays you do for that particular payor over a period of time (1 year is safe) and interpolate the same costs minus some administration and billing, because they will be lower. If you receive a global fee of $150, for example, and one out of three patients has an x-ray and the average cost of that x-ray is $33.36, that equals a cost of $11.12 per patient under the global fee. This same calculation can be done for all payors and all x-rays your center offers and for which it bills. This is true of in-house laboratories.

A lot of work? Absolutely! There is no easy way to do a cost benefit analysis. It takes time and effort and requires a complete knowledge of true costs and actual reimbursements net of any write-offs, charge-offs, collection fees, and any other factors that will affect the actual cash that goes into the center’s bank account.

Understanding RBRVS Now we turn to Resource-Based Relative Value Units (RBRVS). Why are these helpful to your practice, if your practice management system allows you to use them? This is a neutral system used by CMS, HMOs, and many payors to determine how much money providers should be paid. All procedures (CPTs) are assigned a base value, which is influenced by three factors: physician work (52%), practice expense (44%), and malpractice expense (4%). The value for a particular CPT code is then further adjusted by a geographic factor because it clearly costs more to deliver services in New York and San Francisco than it would in small towns where there are no physician shortages. And finally, there is an annual conversion factor.

A debate about the issue of payment for effort-based medicine versus outcomes-based medicine is beyond the scope of this article. Reimbursement for urgent care services traditionally has been done based on our efforts and not the actual outcomes because urgent care providers usually do little follow up and are the largest referral source in all of medicine, save the emergency department. An argument can be made for reimbursing hybrid urgent care centers for outcomes-based medicine, but the focus of this article is understanding costs. And costs based on RBRVS can be a helpful indicator of what it should cost to provide a particular procedure coded via CPT for conditions from urinary tract infection, to ankle sprain, to upper respiratory infection.

Weighing Fee-for-Service Versus Global Fees Once you understand the cost per patient for your urgent care center, you can start evaluating whether fee-for-service is better than global fees on a payor-by-payor basis. In other words, the center will have to absorb the cost per x-ray, which will ONLY be affected on the global fee basis (because it is part of the global fee), but the actual cost per x-ray to the center should be a bit lower because there is less administration and the payment is stable from patient to patient. Yes, the comparison between fee-for-service and global fees is apples to organs, but in the end, the issue is which generates more profit or surplus (for non-profits). This article has not addressed hospital-based centers that have a facility fee and professional component, because a global fee for both typically is precluded by regulatory issues at the state and federal level. Physicians employed by a hospital-owned center may want to consider comparing global fees with fee for service. Again, such calculations can take a lot of time and one center may have a global fee with Medicaid but a fee-for-service arrangement with Blue Cross Blue Shield, for example. However, without calculating the true cost per patient, no urgent care center can be in a position to properly to make a case that an insurance company or CMS is underpaying for its providers’ services.

This primer offers basic tools for starting the process of identifying your urgent care center’s cost per patient. More information is available from the following resources to help providers further refine the process:

- http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/cba.htm

- http://management.about.com/cs/money/a/CostBenefit.htm

- http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newTED_08.htm

- http://www.archives.gov/federal-register/publications/faqs.html

- http://www.physicianpractice.com/rvu/content/article/1462168/1867117

- ← High-Risk Conditions Presenting as Back Pain (Part 2)

- Atypical Appendicitis in the Older Patient →

- Clinical Feature Articles

- Case Reports

- Orthopedic Case Report

- Clinical Image Challenges

- Web Exclusive Images Challenges

- Abstracts in Urgent Care

- JUCM Webinars Archive

- Letters from the Editor-in-Chief

- From the UCA CEO

- Practice Management Articles

- Perspectives

- Occupational Medicine

- Revenue Cycle Management

- Developing Data

- Web Exclusive Articles

- Buyer’s Guide

- Author Bios

- Author Instructions

- Submit An Article

- Individual Articles

- Full Issue PDFs

Remember Me

Lost your password?

Username or E-mail:

Cost per visit

Cost Per Visit indicates the cost incurred by an ecommerce business to attract each visitor to its site.

Cost per visit is a critical metric in ecommerce, representing the amount of money an advertiser spends to garner a single visit to their website through different marketing channels. This metric helps understand the efficiency of an online marketing campaign in terms of attracting potential consumers. It provides an insight into how effectively the advertiser is capitalizing on its digital marketing strategies based on the monetary investment and the traffic drawn to the webpage.

Cost Per Visit = Total Marketing Expenses (in a given period) / Total Website Visits (in that given period)

If an ecommerce business invests $10,000 per month in digital marketing and results in 50,000 site visits, then CPV would be $0.20 ($10,000/50,000).

Why is Cost Per Visit important?

Knowing the Cost per visit helps ecommerce businesses understand the effectiveness of their marketing investments. It enables them to track the cost-effectiveness of different marketing channels, helping them prioritize resources and fine-tune their marketing strategies for maximized returns. Examining Cost per visit can reveal crucial insights into whether a business is spending too much or too little on attracting website visitors.

Which factors impact Cost Per Visit ?

Multiple factors can influence Cost per visit, including the quality of content, SEO effectiveness, the marketing channel's efficiency, targeting precision, frequency of customer interaction, competitor's strategies, and changes in industry trends.

How can Cost Per Visit be improved?

To optimize Cost per visit, it is crucial to improve the conversion rate and drive quality traffic to the website. Ecommerce businesses should focus on effective SEO strategies, high-quality, relevant content, social media marketing, and pay-per-click advertising. A/B testing can also assist in understanding visitor preferences and trends.

What is Cost Per Visit 's relationship with other metrics?

Cost per visit is deeply intertwined with other ecommerce metrics like conversion rate, Cost per Acquisition (CPA), and Return on Marketing Investment (ROMI). A lowered CPV can optimize ROI, indirectly leading to a lower CPA. Enhanced CPV results could indicate improved efficiency in SEO, content, advertising, and overall marketing efforts.

Explore more Glossary terms

Cost of goods sold.

Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) is an accounting metric used to calculate the cost of any goods sold in an ecommerce business.

Coverage Issues

Track SEO health with Coverage Issues metrics. Measure index problems encountered by Googlebot, ensuring website visibil...

Cost Per Completed View

Cost Per Completed View (CPCV) is a digital advertising metric that calculates the cost of a single full video view.

Cost per Email Click

Cost per Email Click (CPC) is a useful email metric that measures the price paid to acquire leads or customers via email...

Clicks per post

Clicks per post refer to the number of times users click on a particular post in an ecommerce environment, offering insi...

CPA fraud refers to dishonest actions undertaken to falsely increase the perceived performance of a CPA campaign.

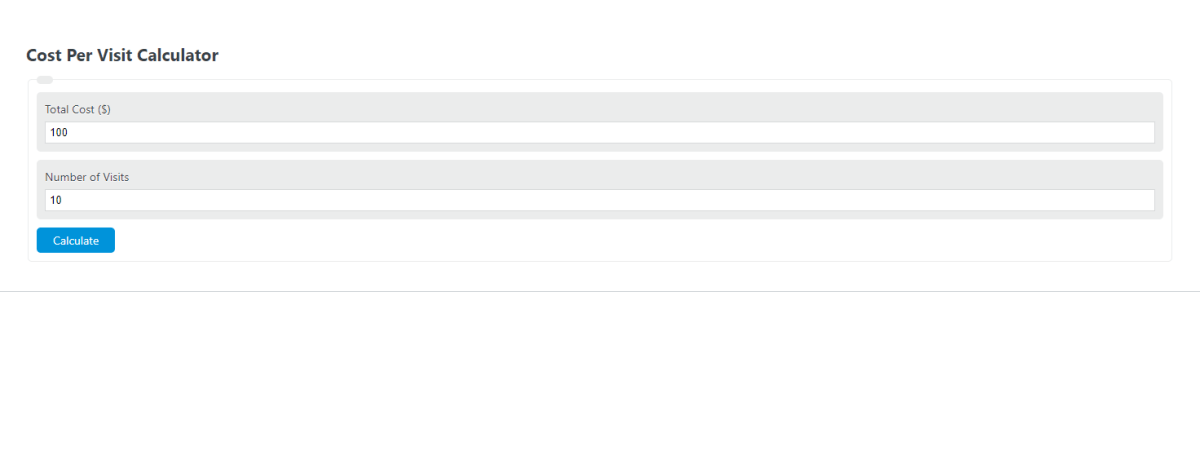

Cost Per Visit Calculator

Author: Calculator Academy Team

Last Updated: August 1, 2023

Enter the total cost of the marketing campaign and the number of visits generated into the calculator to determine the cost per visit.

- Cost Per Click Calculator

- Cost Per Point Calculator

- Cost Per Impression Calculator

- Cost Per Acquisition Calculator

- Cost Per Reach Calculator

- Cost Per Action Calculator

- Cost Per Result Calculator

- Cost Per User Calculator

- Cost Per Vote Calculator

Cost Per Visit Formula

The following equation is used to calculate the Cost Per Visit.

- Where CPV is the cost per visit ($/visit)

- MC is the total marketing cost ($)

- V is the number of visits generated

To calculate the cost per visit, divide the total cost of the marketing campaign by the total number of visits generated.

What is Cost Per Visit?

Definition:

Cost per visit, or CPV for short, is a measure of the monetary costs it takes a business to generate one visit, typically to a website, but in some cases to a physical store.

Sometimes marketing teams like to look at the cost per visit of other metrics like cost per impression because getting people to visit the store or website is the ultimate goal, not getting an impression.

How to Calculate Cost Per Visit?

Example Problem:

The following example outlines the steps and information needed to calculate the Cost Per Visit.

First, determine the total marketing cost. In this case, the marketing cost is found to be $600.00.

Next, determine the total number of website visits generated. For this example, the number of visits was 20.

Finally, calculate the cost per visit using the formula above:

CPV = MC / #V

CPV = $600.00 / 20

CPV = $30.00 / visit

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

How to Calculate Your Health Plan Coinsurance Payment

Health insurance doesn’t pay all of your healthcare expenses. Instead, you’re expected to foot the bill for part of the cost of your care through your health plan’s cost-sharing requirements like your deductible , copayments , and coinsurance .

This article will explain how coinsurance works, how it differs from deductibles and copays, and how you can know what to expect in terms of the bills you may receive from your medical providers.

Since deductibles and copayments are fixed amounts, it doesn’t take a lot of math to figure out how much to pay. A $30 copayment to fill a prescription or see a doctor will cost you $30 no matter how much the total bill for the prescription or office visit was.

Your health insurance picks up the rest of the tab. Note that this generally only applies if you use an in-network provider and fulfill any prior authorization requirements that your insurance plan has.

However, calculating your health insurance coinsurance payment is trickier. Since coinsurance is a percentage of the total cost for the service, you’ll owe a different amount of coinsurance for each service you receive.

If the healthcare service you received was cheap, your coinsurance won’t be much. However, if the healthcare service was expensive, your coinsurance could wind up being hundreds or even thousands of dollars. Your coinsurance will be limited by your health plan's maximum out-of-pocket limit .

You need to understand how to calculate your health insurance coinsurance payment so you’ll know how much you’ll owe for coinsurance and you can budget for it.

Find Your Coinsurance Rate

You’ll need to find your coinsurance rate for the type of care you’re getting. You should be able to locate this in the Summary of Benefits and Coverage you got when you enrolled in your health plan. Sometimes you can even find it on your health insurance card.

Coinsurance typically kicks in after you've met your deductible, so you'll want to understand how much your deductible is as well. You'll pay your medical bills in full—at the negotiated discounted rate that your insurer has with your medical provider—until you've paid an amount equal to your deductible. Then you'll start to pay coinsurance. Note that some health plans have coinsurance for certain drug tiers even before you've met your deductible.

On some health plans, coinsurance can be the same percentage no matter what type of service you get. For example, 30% coinsurance for hospitalization and 30% coinsurance for specialty drug prescriptions.

In other health plans, you might have a low coinsurance rate for some services and a higher rate for other types of services. For example, you could have 35% coinsurance for hospitalization, but only 20% coinsurance for surgery at an outpatient surgery center.

And it's very common for prescription drug coverage to be structured with copayments for drugs that are in lower-cost tiers, but coinsurance for higher tier or specialty drugs. So you may be accustomed to paying a flat dollar amount at the pharmacy, but then end up having to pay a percentage of the cost of a new prescription—which can get quite expensive, depending on the drug.

Note that prescription costs are generally capped by health plans' maximum out-of-pocket limits, but that's not true for Medicare Part D prescription coverage. However, the Inflation Reduction Act is phasing in a cap on out-of-pocket prescription costs under Medicare Part D, starting in 2024.

Find the Cost of Your Care

Once you know your coinsurance rate, you need to determine the total cost of the healthcare service you received. If you’re using an in-network provider, your health plan has already negotiated discounts from that provider.

Calculate your health insurance coinsurance payment based on the discounted rate, not the standard rate charged to people who don’t belong to your health plan.

Find this in-network discounted amount on your Explanation of Benefits (EOB) listed as “ allowed amount ". The EOB will also show the amount the provider billed, which will generally be higher than the allowed amount.

If you haven’t gotten the healthcare service yet, you won’t have an EOB to check. You can try asking your medical provider or health insurer what the in-network rate for that particular service is.

But know that sometimes you simply won't be able to get an accurate estimate of the total cost of your treatment in advance, either because the information is considered proprietary, as part of the network negotiations between the insurer and the medical provider, or because the medical provider won't know in advance exactly what services need to be performed.

A healthcare transparency rule was phased in starting in mid-2022 (fully in force by 2024), requiring health plans to make pricing and network-approved costs available to consumers upon request.

This rule is controversial, with insurers deriding it as unnecessary and costly, while HHS officials herald it as a big step forward for healthcare price transparency. It is expected to result in lower MLR rebates , as well as higher premiums in the individual/family health insurance market.

A similar, but much less far-reaching rule was finalized in 2019, requiring hospitals to publicize their network-negotiated rates for common services. This rule took effect in January 2021, although enforcement and compliance have proved challenging. In 2023, CMS outlined new rules to make hospital pricing lists more readily available to the public.

If the care you're going to need is a basic service that doesn't vary from case to case (an MRI, for example), the hospital or doctor's office should be able to give you a total price in advance.

But if you're having a surgical procedure, the doctor may not know exactly what will be involved until they actually do the surgery—and no amount of transparency regulations can address that.

You can rest assured that your health plan's maximum out-of-pocket will kick in if the bill becomes substantial, but if your out-of-pocket maximum isn't met, the amount you'll have to pay in coinsurance could be subject to change.

Calculate Your Coinsurance

To calculate the coinsurance you owe, you’ll first convert your percentage figure into a decimal figure by moving the decimal point two spaces to the left like this:

Now, multiply this decimal figure by the network-approved amount for the service you had or will have. Note that this is not the same as the amount that is billed by the medical provider since insurance companies negotiate lower rates and require their in-network medical providers to write off the portion of their bill above that amount.

Assuming you've used an in-network medical provider, the coinsurance amount is calculated based on the network-approved price, NOT the amount that was initially billed.

Coinsurance rate (as a decimal figure) x total cost = coinsurance you owe.

Follow these two examples to see the calculations and results

Antoine’s health plan requires 20% cost-sharing to fill a prescription. The network-negotiated price for his prescription is $150.

0.20 x $150.00 = $30.00 Coinsurance rate x total cost = coinsurance Antoine owes.

Antoine owes $30 coinsurance for this particular prescription.

Kinsey’s health plan requires 35% cost-sharing for hospitalizations. The total network-negotiated cost for her hospital stay, after she pays her deductible, is $12,850.

0.35 x $12,850 = $4,497.50 Coinsurance rate x total cost = coinsurance Kinsey owes.

Kinsey will owe $4,497.50 in coinsurance charges for her hospitalization, in addition to the amount of her deductible. But that's assuming she hasn't yet met her health plan's out-of-pocket maximum yet. If her deductible plus this coinsurance would exceed the out-of-pocket maximum for her plan, her coinsurance amount will be reduced so that her costs won't go over the plan's limit.

Factors Affecting Coinsurance Amount

Don’t forget that you must also pay your deductible. On some health plans, you’ll have to pay the entire deductible before your health plan begins to pay part of the cost of your non-preventive care. Only after you’ve paid your full deductible will you be sharing the cost of your care with your health plan by paying coinsurance.

If you have a really big healthcare bill, your out-of-pocket maximum might kick in and protect you from some of the cost. Once the deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance you’ve paid this year add up to the out-of-pocket maximum, your cost-sharing requirements are finished for the year.

Your health plan picks up 100% of the cost of your covered in-network care for the rest of the year. You don’t have to pay coinsurance, copays, or deductibles again until next year (usually). Note that this isn't how it works with Medicare (inpatient cost-sharing for Original Medicare is based on benefit periods rather than the calendar year).

In 2024, all non-grandfathered, non-grandmothered plans must have out-of-pocket maximums that don't exceed $8,450 for a single individual and $18,900 for multiple family members on the same plan. But many plans have out-of-pocket maximums that are well below these limits. Medicare Advantage plans cannot have out-of-pocket maximums of more than $8,850 in 2024 (not counting drug costs). Original Medicare does not have a cap on out-of-pocket costs, but most enrollees have supplemental coverage that pays some or all of the out-of-pocket costs.

Thanks to the Affordable Care Act , most preventive care must be covered by your health insurance without requiring coinsurance, copayments, or even a deductible, as long as your health plan isn't grandfathered.

This means you won’t have to pay coinsurance on things like your yearly physical exam, yearly mammogram, and routine immunizations. Although it may seem like preventive care is free, it’s not. Instead, the cost of that preventive care is included in your monthly health insurance premium whether or not you actually use the care.

It's also important to note that while some of these services, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, are fully paid for by your health insurance without cost-sharing if they're done on a preventive basis, but subject to your deductible and coinsurance if they're considered diagnostic.

So if you're just going in for your routine annual mammogram, you won't have to pay anything. But if you've found a lump in your breast and are having a mammogram to determine whether it's cause for concern, expect to have to pay your health plan's normal cost-sharing (deductible and/or coinsurance) for the mammogram.

Coinsurance is a form of health care cost-sharing in which the patient pays a percentage of the cost and their health plan pays the rest. Coinsurance typically kicks in after the patient has paid their deductible, but before they have met their annual maximum out-of-pocket limit. Coinsurance typically applies to services that aren't covered with a copay.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Transparency in Coverage .

Keith K. Trump Administration finalizes transparency rule for health insurers . Health Affairs. November 1, 2020.

Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public .

Lloyd, Travis G.; Hoffmann, Stephanie M. Bradley Insights and Events. The Ongoing Saga of the CMS Hospital Price Transparency Rule .

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Price Transparency Fact Sheet .

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight. Premium Adjustment Percentage, Maximum Annual Limitation on Cost Sharing, Reduced Maximum Annual Limitation on Cost Sharing, and Required Contribution Percentage for the 2024 Benefit Year .

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Final Contract Year (CY) 2024 Standards for Part C Benefits, Bid Review, and Evaluation .

By Elizabeth Davis, RN Elizabeth Davis, RN, is a health insurance expert and patient liaison. She's held board certifications in emergency nursing and infusion nursing.

- Ironstream for Splunk®

- Ironstream for ServiceNow®

- Automate Evolve

- Automate Studio

- Assure Security

- Assure MIMIX

- Assure MIMIX for AIX®

- Assure QuickEDD

- Assure iTERA

- Syncsort MFX

- Syncsort Optimize IMS

- Syncsort Optimize DB2

- Syncsort Optimize IDMS

- Syncsort Network Management

- Syncsort Capacity Management

- Spectrum Context Graph

- Spectrum Global Addressing

- Spectrum Quality

- Trillium Discovery

- Trillium Geolocation

- Trillium Quality

- Data360 Analyze

- Data360 DQ+

- Data360 Govern

- Spectrum Spatial

- Spectrum Spatial Routing

- Spectrum Spatial Insights

- Spectrum Global Geocoding

- Spectrum Enterprise Tax

- MapInfo Pro

- Precisely Addresses

- Precisely Boundaries

- Precisely Demographics

- Precisely Points of Interest

- Precisely Streets

- PlaceIQ Audiences

- PlaceIQ Movement

- EngageOne Communicate

- EngageOne RapidCX

- EngageOne Digital Self-Service

- EngageOne Vault

- EngageOne Compose

- EngageOne Enrichment

- Precisely Data Integrity Suite

- Precisely APIs

- Precisely Data Experience

- Customer engagement

- Digital self-service

- Digital archiving

- Email and SMS

- Print to digital

- Data enrichment

- Data integrity

- Environmental, social and governance (ESG)

- Data integration

- Security Information and Event Management

- Real-time CDC and ETL

- IT Operations Analytics

- IT Operations Management

- Cloud data warehousing

- Data governance

- Data catalog

- Data products

- Data quality

- Address validation/standardization

- CRM & ERP data validation

- Customer 360

- Data matching & entity resolution

- Data observability

- Data reconciliation

- Data validation and enrichment

- IBM systems optimization

- Geo addressing and spatial analytics

- Spatial analytics

- Geocoding and data enrichment

- Master data management

- Process automation

- Amazon Pinpoint

- Compliance with security regulations

- Security monitoring and reporting

- High availability and disaster recovery

- Data privacy

- Access control

- IBM mainframe

- Sort optimization

- Microsoft Azure

- SAP process automation

- Excel to SAP automation

- SAP master data management

- SAP finance automation

- Financial services

- Telecommunications

- Precisely Strategic Services

- Professional services

- Analyst reports

- Customer stories

- Infographics

- Product demos

- Product documentation

- Solution sheets

- White papers

- IBM i security

- Location intelligence

- Master Data Management

- SAP Automation

- Financial service and banking

- Supply Chain

- Global offices

- Careers and Culture

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging

- Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG)

- Global Code of Conduct

- Precisely Trust Center

- Press releases

- In the news

- Trust ’23

- Get in touch

Blog > Data Enrichment > The Emergence of Cost-Per-Visitor and What Marketers Need to Know

The Emergence of Cost-Per-Visitor and What Marketers Need to Know

Location data allows businesses to understand consumer behavior, drive sales, and inform decisions in incredible ways. However, the technology needs for accurate location intelligence are exceedingly complex. Like a Russian doll, there are multiple layers beneath the surface – all working together to collect and interpret massive amounts of data, and determine the best way to deploy intelligence in a dynamic and ever-changing world.

Admittedly, new technologies are inherently complex. Their norms have not been established, and standards compete for consensus. Companies package products in a noble effort to provide a simple interface to promising, powerful, and complex capabilities.

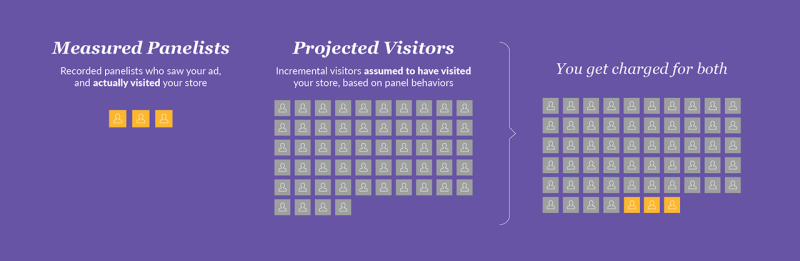

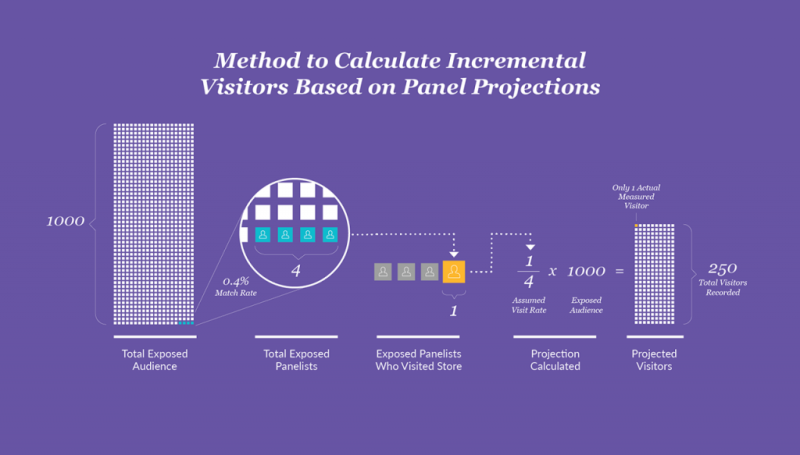

One recent model we’ve taken note of is Cost Per Visit (CPV). On the surface, it seems like a simple way to use location – but when you peel back the layers, there’s a lot that is not immediately clear. The allure of simplicity is concealing some troubling details.

What is Cost Per Visit? CPV is a new metric that aims to charge advertisers only for new store visits that are driven by media. This structure is meant to increase the efficiency of an advertiser’s spend. However, there are many challenges to overcome before CPV can be reliably used as a transactional metric. For now, if you are evaluating CPV, here are three important things to consider:

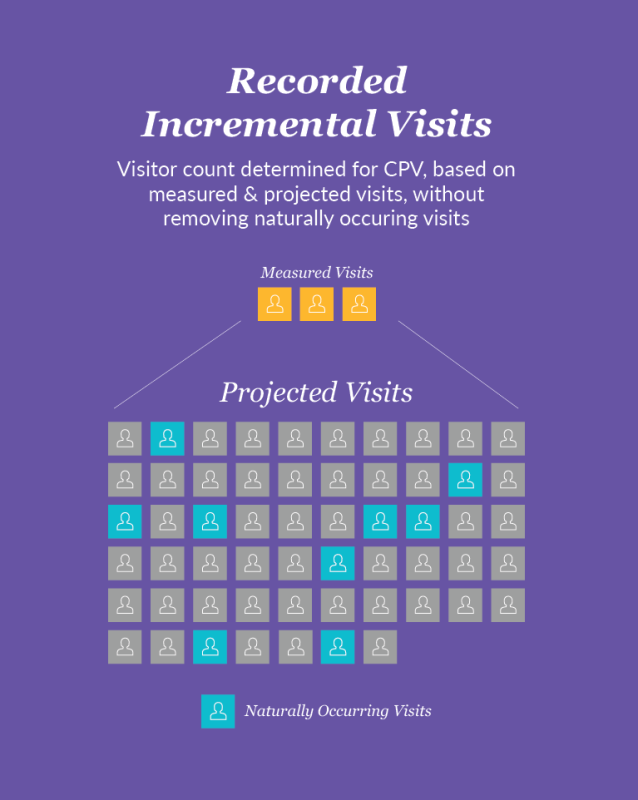

1. Panel projections are used to measure visits – you are not paying for visits, you are paying for projected visits. Current CPV offerings use panel-based projections to validate visitation measurement. While fine for directional insights, limited size panels aren’t ideal when projecting a precise number of visits for locations. This is because panels only measure a very small portion of all visits; the rest of the measured visits (which advertisers are asked to pay for) are assumed to have happened. This all boils down to an alarming fact: advertisers are being charged for projected visits, not actual measured visits.

2. Projections account for a majority of visits a media company is taking credit for – between 99.5% and 99.7% of reported visits are projections, not actual visits. Think about it this way – let’s say 1000 people view your ad. With the standard campaign panel match rates we’ve seen (between 0.3-0.5%), that means about 4 panelists (out of the 1,000) will see your ad. If only 1 out of the 4 panelists visited your store, the other 996 ad viewers (non-panelists) would be assumed to visit at the same rate (25%). This means you would be charged for 250 visitors, even though only 1 was measured as a visitor .

3. The control group methodology used to calculate incremental visits is flawed – which means you will pay for visits which would have occurred anyway! To account for an audience’s normal visitation behavior (i.e. loyal customers), it is essential to withhold part of your audience from advertising. This is known as a B control group, and is used as a benchmark to measure expected, predictable behavior. True control groups mirro r the group who do receive ads as closely as possible – typically down to the DMA and demographic level. In addition, a proper B control group will include previous visitation patterns to isolate the incremental visits driven by your campaign. If someone shops at Kroger every week, it would be disingenuous to credit an advertisement with generating their usual weekly grocery run.

Read our Audience Handbook

Precisely PlaceIQ Syndicated Audience Handbook

Read this handbook and explore real-world audiences to discover new and innovative ways to reach high-value consumers.

Unfortunately, available CPV offerings do not use well planned B control groups. This means they are reporting inflated visitation metrics, and advertisers are being charged for visits that would have occurred normally. Think of it this way – let’s say you target frequent store visitors . A portion of this group would have visited anyways – because that is their typical behavior. Without a proper control group in place to account for this, the advertiser will end up paying for normal visits , instead of just incremental visits.

To summarize; with a CPV model as it exists today, you are paying for projected visits, based upon a panel that measures only 0.3% to 0.5% of your audience. To make matters worse, those visits likely aren’t incremental and we have no way of determining ad-driven visits since a true B control isn’t used.

Think of it this way: Would you pay Google for 1000 clicks, after 3 clicks occurred?

Would you declare the winner of a marathon after 138 yards?

If you answered no to either of these, then CPV probably isn’t for you, as current approaches in-market use the same type of projections.

While one day a proper and accountable CPV system may exist, the structural realities of available data are the natural gating factor. As such, marketers should consider CPV to still be in its primitive stages, with many challenges to address before it can be a reliable metric to transact against. For those testing the waters, it is important to dig deep with your vendor, ask questions, and understand their underlying approach. This will enable you to make the best decision for your campaign, your budget, and your brand.