Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer and cartographer best known for establishing and governing the settlements of New France and the city of Quebec.

Who Was Samuel de Champlain?

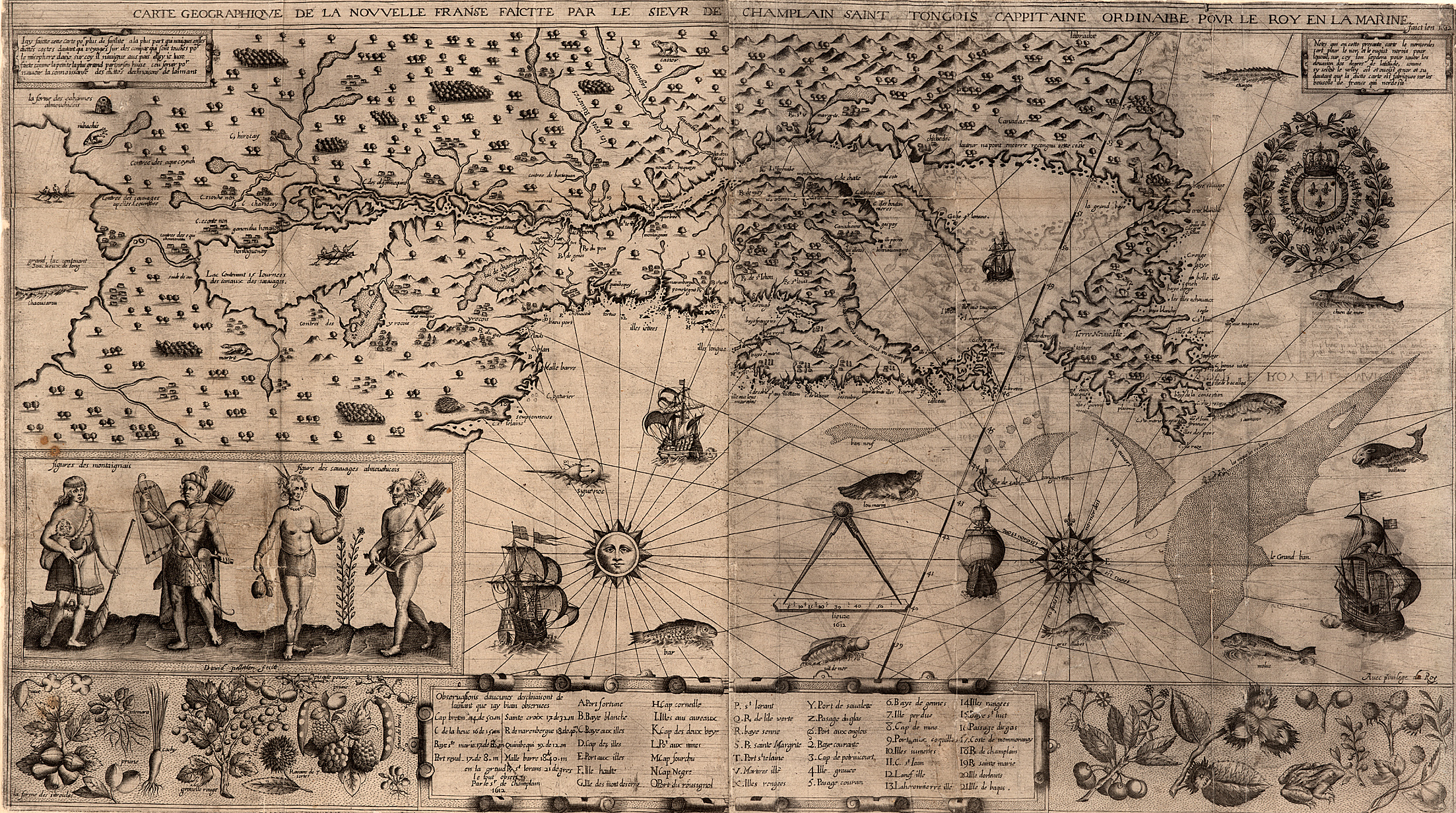

French explorer Samuel de Champlain began exploring North America in 1603, establishing the city of Quebec in the northern colony of New France, and mapping the Atlantic coast and the Great Lakes, before settling into an administrative role as the de facto governor of New France in 1620.

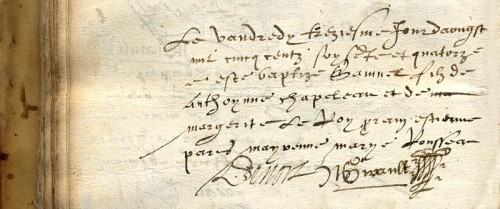

Samuel de Champlain was born in 1574 (according to his baptismal certificate, which was discovered in 2012), in Brouage, a small port town in the province of Saintonge, on the western coast of France. Although Champlain wrote extensively of his voyages and later life, little is known of his childhood. He was likely born a Protestant, but converted to Catholicism as a young adult.

First Explorations and Voyages

Champlain's earliest travels were with his uncle, and he ventured as far as Spain and the West Indies. From 1601 to 1603, he was a geographer for King Henry IV, and then joined François Gravé Du Pont's expedition to Canada in 1603. The group sailed up the St. Lawrence and Saguenay rivers and explored the Gaspé Peninsula, ultimately arriving in Montreal. Although Champlain had no official role or title on the expedition, he proved his mettle by making uncanny predictions about the network of lakes and other geographic features of the region.

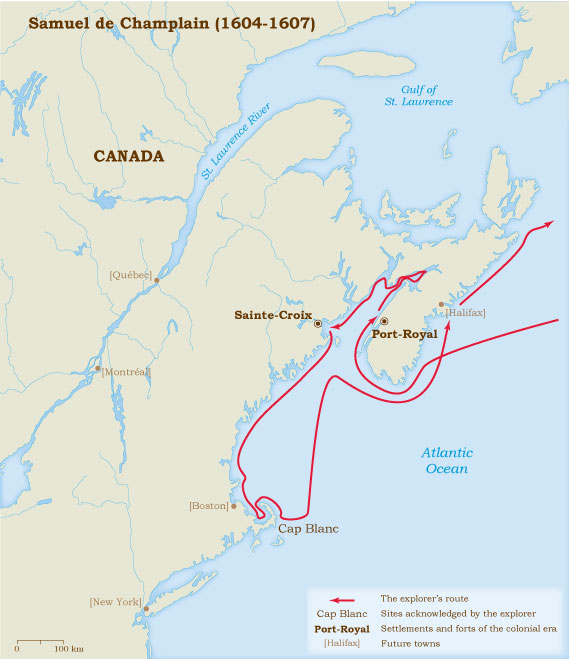

Given his usefulness on Du Pont's voyage, the following year Champlain was chosen to be geographer on an expedition to Acadia led by Lieutenant-General Pierre Du Gua de Monts. They landed in May on the southeast coast of what is now Nova Scotia and Champlain was asked to choose a location for a temporary settlement. He explored the Bay of Fundy and St. John River area before selecting a small island in the St. Croix River. The team built a fort and spent the winter there.

In the summer of 1605, the team sailed down the coast of New England as far south as Cape Cod. Although a few British explorers had navigated the terrain before, Champlain was the first to give a precise and detailed accounting of the region that would one day become Plymouth Rock.

Establishing Quebec

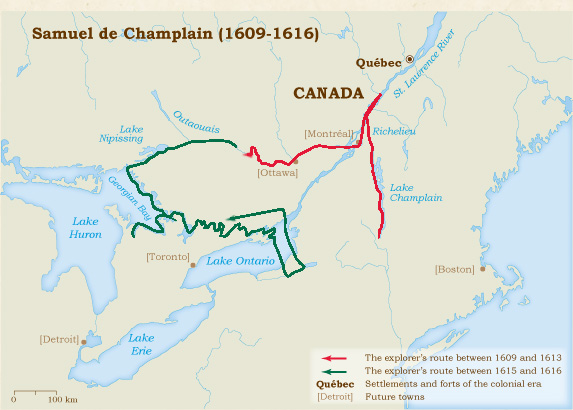

In 1608, Champlain was named lieutenant to de Monts, and they set off on another expedition up the St. Lawrence. When they arrived in June 1608, they constructed a fort in what is now Quebec City. Quebec would soon become the hub for French fur trading. The following summer, Champlain fought the first major battle against the Iroquois, cementing a hostile relationship that would last for more than a century.

In 1615, Champlain made a brave voyage into the interior of Canada accompanied by a tribe of Native Americans with whom he had good relations, the Hurons. Champlain and the French aided the Hurons in an attack on the Iroquois, but they lost the battle and Champlain was hit in the knee with an arrow and unable to walk. He lived with the Hurons that winter, between the foot of Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe. During his stay, he composed one of the earliest and most detailed accounts of Native American life.

Later Years and Death

When Champlain returned to France, he found himself embroiled in lawsuits and was unable to return to Quebec. He spent this time writing the stories of his voyages, complete with maps and illustrations. When he was reinstated as lieutenant, he returned to Canada with his wife, who was 30 years his junior. In 1627, Louis XIII's chief minister, Cardinal de Richelieu, formed the Company of 100 Associates to rule New France and placed Champlain in charge.

Things didn't go smoothly for Champlain for long. Eager to capitalize on the profitable fur trade in the region, Charles I of England commissioned an expedition under David Kirke to displace the French. They attacked the fort and seized supply ships, cutting off necessities to the colony. Champlain surrendered on July 19, 1629 and returned to France.

Champlain spent some time writing about his travels until, in 1632, the British and the French signed the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, returning Quebec to the French. Champlain returned to be its governor. By this time, however, his health was failing and he was forced to retire in 1633. He died in Quebec on Christmas Day in 1635.

Related Videos

Quick facts.

- Name: Samuel de Champlain

- Birth City: Brouage, Province of Saintonge

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer and cartographer best known for establishing and governing the settlements of New France and the city of Quebec.

- Politics and Government

- War and Militaries

- Technology and Engineering

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1635

- Death date: December 25, 1635

- Death City: Quebec

- Death Country: Canada

- The advice I give to all adventurers is to seek a place where they may sleep in safety.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

The Ages of Exploration

Samuel de champlain, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

French explorer and cartographer best known for establishing and governing settlements in Canada, mapping the St. Lawrence River, discovering the Great Lakes, and founding the city of Quebec

Name : Samuel de Champlain [sam-yoo-uh l; (French) sa-my-el ] [ duh] [sham-pleyn; (French) shahn-plan]

Birth/Death : ca. 1567 - December 25, 1635

Nationality : French

Birthplace : Brouage, France

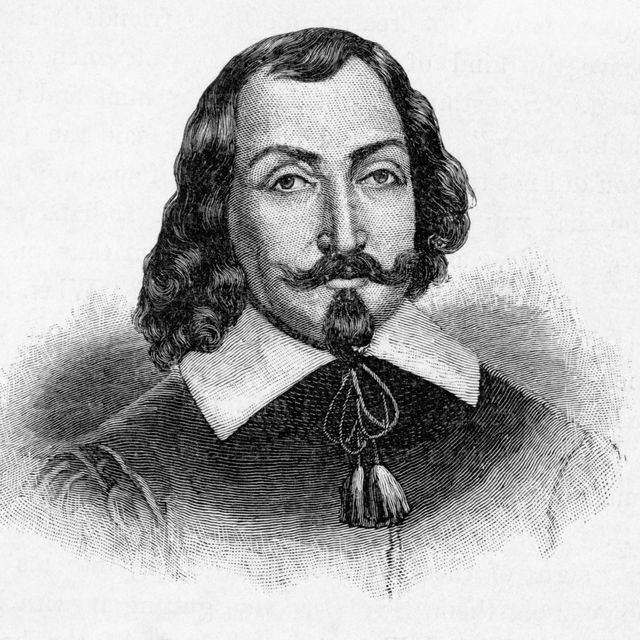

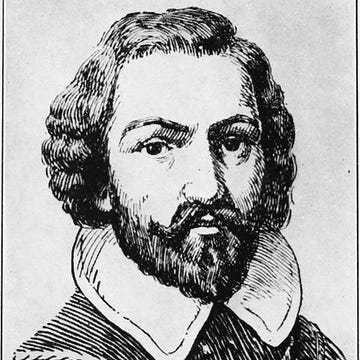

Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635), most likely styled after a portrait by Moncornet, 19th century. Source: A Popular History of France from the Earliest Times, Vol. 6, Chapter 53, p. 190. {{PD-Art}

Introduction Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer famous for his journeys in modern day Canada. During his travels, he mapped the Atlantic coast of Canada, parts of the St. Lawrence River, and parts of the Great Lakes. He is best known for establishing the first French settlement in the Canadian territory, and founding the city of Quebec. Because of this, Champlain became known as the “Father of New France.” 1

Biography Early Life Samuel de Champlain was born in the French village Brouage in the Province of Saintonge. Historians do not know his exact date of birth, but most agree it was between 1567 and 1570. 2 His father was Antoine Champlain and his mother was Marguerite Le Roy. Brouage was a seaport town where Antoine Champlain was a sea captain in the merchant marine. 3 Samuel de Champlain probably would have had a modest education where he learned to read and write. But his real skill was navigation. He went to sea at a young age, and learned to navigate, draw, and make nautical charts. During this time period, the French were at war against the Spanish. In 1593, Champlain served in the army of Henry of Navarre – also known as King Henry IV of France. He served in the army for 5 years, until King Henry’s and France’s victory in 1598. When the war ended, Champlain joined his uncle, Captain Provençal, on a mission from the King to return any captured Spanish soldiers to Spain.

Champlain and Provençal, along with their crew and captured Spanish soldiers, left France aboard the St. Julien September 9, 1598. They delivered the soldiers to Spain, but did not return back to France. Instead, the Spanish government hired Provençal and Champlain for a trip to its colonies in the West Indies (the Caribbean region). They accepted, and between 1599 and 1601, Champlain made three voyages for Spain to her American colonies. During these years, he visited several places, including the Virgin Islands and other Caribbean islands, Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Panama. Along the way he recorded much of his journey. In 1601, he wrote a detailed report to King Henry about his trip, which included maps, and drawings of plants and animals. He even mentioned the idea of a canal that should cut through Panama to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. 4 300 years later, this would be seen in the creation of the Panama canal. The King was impressed with Champlain’s descriptions. King Henry IV wanted to the French to begin settling in the New World in hopes that wealth could be brought back to France. So he sent an expedition to locate a place in the New World to establish a French colony and fur trade settlement. Samuel de Champlain would be among the men who would take part in this venture.

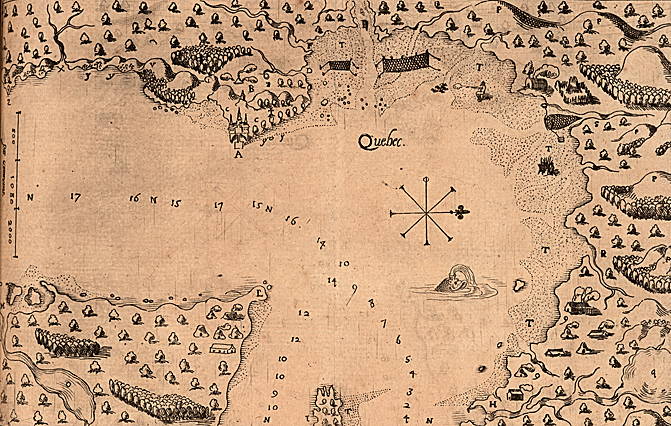

Voyages Principal Voyage Samuel de Champlain would take his second New World voyage under the expedition of François Gravé Du Pont. The fleet set sail from France on March 15, 1603. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean and arrived in North America. They continued past Newfoundland, entered the St. Lawrence River. They anchored in the harbor of Tadoussac near the mouth of the Saguenay River on May 26, 1603. 5 While here, the French interacted with some of the natives, and Champlain recorded the customs and interactions of these people. The expedition soon continued up the St. Lawrence River, and made it as far as present day Montréal. The native guides that had helped the Frenchmen spoke of a great sea to the west. Champlain hoped this sea to be the Pacific Ocean and the Northwest Passage to Asia. However, due to the strong rapids, the French were unable to explore much further. It would later be known that the “sea” the natives referred to were the Great Lakes. 6 Champlain continued to explore and interactive with the different native tribes, which included the Algonquin, Montagnais, and Hurons. The expedition ended when they returned to France in September 1603.

In France, Champlain reported the details of his trip to the King. By 1604, Champlain was once more heading to the New World. This time the expedition was led by Pierre du Gua de Monts. De Monts had been granted monopoly – exclusive possession – of the fur trade. They would spend the next three years exploring and mapping parts of North America. The expedition set sail on three ships, including La Bonne Renommée and Don de Dieu which Champlain sailed on. The goal was to once again try to find a good place for a French settlement. They landed on the coast of Nova Scotia, sailed around to the Bay of Fundy. 7 The expedition focused much its efforts on areas south of the St. Lawrence River. After a few months, they settled for winter at Saint Croix Island in the St. Croix River. After enduring a harsh winter, they began exploring the eastern coastline as far down as Cape Cod. In 1605, they established their first successful settlement – Port Royal (now known as Annapolis Royal) in Nova Scotia. In 1606, this site would become the capital of the area known as Acadia. Du Gua had to return to France in September 1605. His company was having financial hardship. Champlain and the expedition continued exploring these areas for the next few years. In July 1607, du Gua’s fur trade monopoly ended. Port Royal was forced to end, and Champlain and the settlers returned to France. 8

Subsequent Voyages In 1608, Champlain was chosen as du Gua’s lieutenant on another expedition across the Atlantic. Champlain left France on April 13, 1608 and headed for the St. Lawrence river. Once again, the goal was to start a new French colony. Champlain found an area on the shores of the St. Lawrence river and began constructing a fort and other buildings. In July 1608, Samuel de Champlain and his men created the first successful French colony in New France. The site of the colony was at a place the native Indians called kebec which means “ the narrowing of the waters.” 9 Champlain and the French spelled it Quebec. During the very harsh winter here, several of the men died of scurvy. In the summer of 1609, Champlain planned to head west further inland to explore and map the land. Before he could go, the Algonquins and Huron natives asked Champlain to help them attack the powerful Iroquois tribe. He joined them, and on July 29, they all defeated the Iroquois army. This expedition also enabled Champlain to explore the Richelieu River and to become the first European to map Lake Champlain. This battle would lead to several years of hostility between the French and Iroquois natives. With the death of King Henry, however, Champlain returned to France to discuss his political future.

Champlain returned to France and reported the success of creating the settlement of Quebec. It was decided that it would be the center for the French fur trade. Champlain returned to New France and Quebec many times over the next several years where he went on to explore and map much of the land. In 1610, he fought against the Iroquois once again. In spring 1611, he sailed up the St. Lawrence river and made it as far as present day Montreal. When he returned to France, the King chose Champlain to be his lieutenant in New France. 10 He was back in Quebec by March 1613. This time he went as far as the Ottawa River and explored areas connected to the Great Lakes. In 1615, he traveled up the Ottawa River to Lake Nipissing and the French River. He saw the Great Lakes for the first time when he arrived at Georgian Bay on the east side of Lake Huron. 11 When he returned to France, Champlain’s position as lieutenant in New France was taken away. This discovery would be his last great voyage of exploration. He would spend the next years of his life trying to re-establish and maintain his authority in New France.

Later Years and Death Samuel de Champlain returned to France in July 1616 where he learned his title of lieutenant had been taken away. He suggested to the French King that they begin growing the colony of Quebec. The King agreed, and Champlain returned to New France again in 1620. He spent the rest of his life focusing on governing and growing the territory rather than exploration. In 1628, Champlain became the deputy of the “Company One Hundred Associates” organized by Cardinal Richelieu to colonize New France. The company was given all the lands between Florida and the Arctic Circle, with a monopoly of trade with the exception of cod and whale fisheries. The Quebec colony had continued problems from the natives. In 1629 Champlain was forced to surrender Quebec to the English until 1632 when the colony was returned to France. In 1633, Champlain returned to Quebec where he continued to serve as governor. As he grew older, he became ill in late 1635. Champlain died in Quebec on Christmas Day – December 25, 1635.

Legacy Samuel de Champlain is remembered as one of the greatest pioneers of French expansion in the 17th century. He formed several settlements, including Acadia and Quebec City. He also mapped and explored much of the region. His travels enabled France to gain control on the North American continent and form the country of Canada. Champlain wrote down and left behind his writings related to his voyages. His accounts described many areas he explored, indigenous peoples, local plants and animals, and numerous maps. Champlain is honored throughout Canada. Many places bear his name, including Lake Champlain. But his legacy is best seen in the city of Quebec. By the time of Champlain’s death, there were almost 300 French pioneers living in New France. 12 Now, they have a population of over 7 million people. 13 Quebec City continues to be a thriving area and is the capital of the Quebec Province in Canada still today.

- Adrianna Morganelli, Samuel de Champlain: From New France to Cape Cod (New York: Crabtree Publishing Company, 2006), 4.

- Josepha Sherman, Samuel de Champlain, Explorer of the Great Lakes Region and Founder of Quebec (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2003), 7.

- Sherman, Samuel de Champlain , 7.

- Harold Faber, Samuel de Champlain, Explorer of Canada (New York: Benchmark Books, 2005), 10.

- Daniel B. Baker, ed., Explorers and Discoverers of the World (Detroit: Gale Research, Inc., 1993), 131.

- Morganelli, Samuel de Champlain , 10.

- Baker, Explorers and Discoverers of the World , 131.

- Raymonde Litalien and Denis Vaugeois, eds., Champlain: The Birth of French America (Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004), 146.

- Richard E. Bohlander, ed., World Explorers and Discoverers (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992), 106.

- Baker, Explorers and Discoverers of the World , 132.

- Bohlander, World Explorers and Discoverers , 108.

- Francois Remillard and Ulysses Travel Guides, Quebec (Montreal: Hunter Publishing, Inc., 2003), 13.

- Remillard and Ulysses Travel Guides, Quebec , 25.

Bibliography

Baker, Daniel B., ed. Explorers and Discoverers of the World . Detroit: Gale Research, Inc., 1993.

Bohlander, Richard E., ed. World Explorers and Discoverers . New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992.

Faber, Harold. Samuel de Champlain, Explorer of Canada . New York: Benchmark Books, 2005.

Litalien, Raymonde, and Denis Vaugeois, eds. Champlain: The Birth of French America . Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004.

Morganelli, Adrianna. Samuel de Champlain: From New France to Cape Cod . New York: Crabtree Publishing Company, 2006

Remillard, Francois, and Ulysses Travel Guides. Quebec . Montreal: Hunter Publishing, Inc., 2003.

Sherman, Josepha. Samuel de Champlain, Explorer of the Great Lakes Region and Founder of Quebec . New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2003.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Samuel de Champlain

This timeline chronicles major events in Samuel de Champlain's life.

March 15, 1603

Undefined

Champlain's First Trip

Samuel de Champlain boarded the Bonne-Renommée at Honfleur, France, destined for New France, as a private passenger on Gravé Du Pont's expedition.

May 26, 1603

Champlain Reaches Tadoussac

Samuel de Champlain reached Tadoussac on the north shore of the St Lawrence River and set foot for the first time in New France.

June 11, 1603

Champlain Learns of Hudson Bay

Samuel de Champlain travelled nearly 60 km up the Saguenay River, and learned from the Montagnais tribe that a large saltwater body existed to the north (the Hudson Bay).

July 04, 1603

Champlain Reaches Montréal

Samuel de Champlain explored the Saguenay River and journeyed up the St Lawrence River, reaching the Lachine Rapids and the future site of Montréal on July 4.

July 15, 1603

Champlain Arrives at Gaspé

Samuel de Champlain arrived at Gaspé, where he first heard about Acadia.

September 02, 1604

Champlain Explores Bay of Fundy

Samuel de Champlain began exploring the Bay of Fundy to seek an ideal site for a permanent settlement, becoming the first European to create a geographical description of the area.

September 05, 1606

Expedition to Massachusetts

Samuel de Champlain and Jean de Poutrincourt launched another expedition from Port-Royal to explore the coast of Massachusetts, hoping to establish friendly relationships with the Secoudon and Messamouet in the area. Their efforts were met with hostility and soon abandoned.

August 11, 1607

Port-Royal Abandoned

The Port-Royal settlement was abandoned on orders from France. On Sept 3, after skirting the Straits of Canso and mapping the Atlantic coastline from Cape Breton to the south of Cap Blanc, Samuel de Champlain and the other voyagers headed home to St Malo. Only Poutrincourt would return, in 1610.

April 13, 1608

Champlain Leaves on 3rd Voyage

As lieutenant to the Sieur de Monts, Samuel de Champlain set out on his third voyage to New France. He arrived at Tadoussac on 3 June.

July 03, 1608

Founding of Québec

Samuel de Champlain established a fortified trading post at Québec, the perfect location to foster the fur trade and to serve as the base for its founder's idea of colonizing the remote country.

June 28, 1609

Champlain Explores Haudenosaunee Country

Samuel de Champlain explored Haudenosaunee country, entering the Rivière des Iroquois (Richelieu), paddling upriver and reaching a great lake that would later bear his name.

July 30, 1609

Champlain Battles the Haudenosaunee

Champlain and his First Nations allies battled the Haudenosaunee on Lake Champlain, beginning 150 years of war between Iroquois and French. Champlain's musket kills three and astonishes the enemy.

October 13, 1609

Champlain Returns to France

Samuel de Champlain arrived back in France, ready to report to the king on the success of New France and extol the virtues of the Québec habitation as a warehouse for the fur trade.

August 08, 1610

Champlain Sets Sail for France

After a disastrous year for the fur trade, Samuel de Champlain set sail for France, leaving behind 16 men under the command of Jean de Godet Du Parc.

December 27, 1610

Champlain Marries

At the approximate age of 40, Samuel de Champlain entered into an elaborate marriage contract with Hélène Bouellé, aged 12, who brought a large dowry. They were married in Paris on December 30; the marriage came into effect two years later.

May 28, 1611

Champlain Leaves for Lachine

Samuel de Champlain left Québec and arrived at Lachine and named the island in the middle of the St Lawrence River St. Hélène for his wife.

June 13, 1611

Champlain Shoots Rapids

Samuel de Champlain impressed his native allies by shooting the dangerous Lachine Rapids in a canoe.

October 08, 1612

Bourbon Named Lieutenant-General of New France

Louis XIII named Charles de Bourbon, Comte de Soissons, as his lieutenant-general in New France. Bourbon chose Samuel de Champlain as his lieutenant on Oct 15.

January 09, 1613

Champlain Publishes Voyages

Samuel de Champlain published his Les Voyages du Sieur de Champlain , describing his adventures in New France.

May 29, 1613

Champlain Reaches Ottawa River

Champlain reached the mouth of the Ottawa River. On June 4 he noted the mouths of the Gatineau and Rideau rivers at the present site of Ottawa.

September 26, 1613

Champlain Promotes New France

Champlain left for France, where he remained until April 24, 1615 to promote the cause of New France.

May 25, 1615

Récollets Arrive

Four Récollets from France arrived at Tadoussac with Champlain, only to quickly go their separate ways. The best-known Récollet, Gabriel Sagard, later published Le Grand Voyage du pays des Hurons, an indispensable source of knowledge of Huron customs and culture.

July 01, 1615

Champlain Visits Huronia

French explorer Samuel de Champlain reached Huronia, at the southern end of Georgian Bay.

July 09, 1615

Champlain Treks Up Ottawa River

Samuel de Champlain began his journey up the Ottawa River, passing through the Lac des Népissingues (Lake Nipissing), the Rivière des Français (French River) and the great Lac Attigouautau (Lake Huron). He arrived among the Hurons on 1 August.

August 01, 1615

Champlain Arrives at Huronia

Samuel de Champlain completed his journey up the Ottawa River, arriving among the Hurons.

September 01, 1615

French Mobilize Forces

An attack force of 500 First Nations and French moved out from Cahiagué, Huronia, to present-day Orillia. On Sept 8 Champlain sent Etienne Brulé to make contact with the SusQuéhanna.

October 11, 1615

Champlain Wounded

Samuel de Champlain was wounded twice in the leg by arrows when he and his Huron-Wendat allies stumbled upon an Haudenosaunee fort.

Champlain's Third Battle with the Haudenosaunee

Champlain and his allies arrived at a Haudenosaunee fort on Lake Onanadaga, just north of present-day Syracuse. The Haudenosaunee routed the invaders, wounding Champlain with two arrows.

January 15, 1616

Champlain Leaves Huronia

Samuel de Champlain left Huronia to visit the Tobacco Nation (south of Nottawasaga Bay), then the Cheveux-Relevés (Ottawas, south of Georgian Bay), extending an invitation to the natives to come to Québec.

September 10, 1616

Champlain Returns with Map

Samuel de Champlain arrived in France, where he would publish an engraved map of New France.

March 12, 1618

Louis XIII Initiates Colony

King Louis XIII instructed Samuel de Champlain and his partners to establish a viable colony in New France.

May 18, 1619

Voyages Published

The Voyages and Explorations of Samuel de Champlain , an account of Samuel de Champlain's adventures in New France, was published.

May 07, 1620

Champlain Becomes Governor

Louis XIII wrote to Samuel de Champlain, commissioning him to govern New France and to do so in accordance with the laws and customs of France. From that point, Champlain devoted himself almost exclusively to administration and his career as an explorer ended.

August 21, 1624

Champlain Leaves Québec

With construction of a new habitation well underway, Champlain left Québec with his wife, who would not to return. He landed at Dieppe, France in October.

April 27, 1628

Oxen in New France

Samuel de Champlain recorded in his journal that, for the first time in New France, land had been broken by the plough drawn by oxen, a task typically carried out by human strength.

July 20, 1629

Champlain Surrenders Québec

Champlain wrote the articles of capitulation on July 19 and on the following day surrendered Québec to the English adventurer David Kirke and his brothers. He was captured and taken to England.

March 29, 1632

Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye

France recovered Québec from England in the Treaty of Saint-Germain, along with compensation for goods siezed when Champlain surrendered Québec.

March 01, 1633

Champlain Recommended to Lead Colony

Asked by Cardinal Richelieu to take command of the colony, Isaac de Razilly deferred to Champlain as being more competent in colonial affairs.

March 23, 1633

Champlain's Final Voyage

Samuel de Champlain set sail on his final voyage to Québec at age 63.

May 23, 1633

Champlain Returns to Québec

Champlain returned to Québec and began to rebuild the Habitation from its ruins and to build the church of Notre-Dame-de-la-Recouvrance.

August 18, 1634

Champlain's Last Words

Champlain wrote to Richelieu, his last words on record, reporting that he had rebuilt the ruins of Québec and had built an armed trading post at Trois-Rivières. He also noted that several new families had arrived in the area, giving him renewed hope for the survival of settlement in the area.

December 25, 1635

Death of Champlain

Champlain died at Québec. He had suffered a stroke the previous October and signed his will November 17.

Virtual museum of New France

- Virtual museum of new France

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

The Explorers

- Economic Activities

- Useful links

- North America Before New France

- From the Middle Ages to the Age of Discovery

- Founding Sites

- French Colonial Expansion and Franco-Amerindian Alliances

- Other New Frances

- Other Colonial Powers

- Wars and Imperial Rivalries

- Governance and Sites of Power

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Basque Whalers

- Industrial Development

- Commercial Networks

- Immigration

- Social Groups

- Religious Congregations

- Pays d’en Haut and Louisiana

- Entertainment

- Communications

- Health and Medicine

- Vernacular Architecture in New France

Samuel de Champlain (sometimes called Samuel Champlain in English documents) was born at Brouage, in the Saintonge province of Western France, about 1570. He wrote in 1613 that he acquired an interest “from a very young age in the art of navigation, along with a love of the high seas.” He was not yet twenty when he made his first voyage, to Spain and from there to the West Indies and South America. He visited Porto Rico (now Puerto Rico,) Mexico, Colombia, the Bermudas and Panama. Between 1603 and 1635, he made 12 stays in North America. He was an indefatigable explorer – and an assistant to other explorers – in the quest for an overland route across America to the Pacific, and onwards to the riches of the Orient.

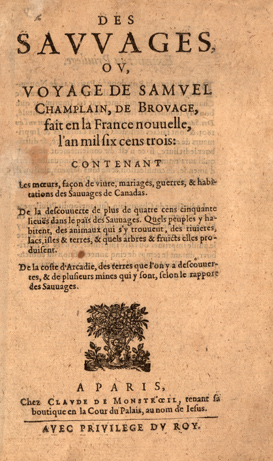

The Mystery of Samuel de Champlain

In the title of his first book, published in 1603, Des Sauvages, ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouage, fait en la France nouvelle l’an mil six cens trois… [“Concerning the Primitives: Or Travels of Samuel Champlain of Brouage, Made in New France in the Year 1603”], Samuel de Champlain indicated that he was a native of Brouage in the Saintonge region of France. But a fire in the 17th century completely destroyed the town records of Brouage, where the young Champlain was believed to have spent his childhood. Since then, historians have speculated about the birth date of the man often described as the “Father of New France.”

The name “Samuel,” taken from the Old Testament, suggests the possibility that Champlain was born into a Protestant family during a period when France was torn by endless conflicts over religion. However, by the time he undertook his voyages of discovery and exploration to Canada, he had definitely converted to Catholicism. The marriage contract between Samuel de Champlain and Hélène Boullé, dated 1610, shows that he was the son of the then-deceased sea captain, Anthoine de Champlain, and Marguerite Le Roy. On this basis, several historians have deduced that Champlain must have been born around 1570.

These are the few facts that history reveals, leaving room for all sorts of hypotheses about Champlain’s date of birth. But things were to take a different turn in the spring of 2012 when Jean-Marie Germe, a French genealogist, was examining the archives of the Protestant parish of Saint Yon de La Rochelle. In Champlain’s time, La Rochelle was a neighbouring town and rival of Brouage. What Mr. Germe found there was the baptismal record of Samuel Chapeleau, son of Antoine Chapeleau and Marguerite Le Roy, dated August 13, 1574.

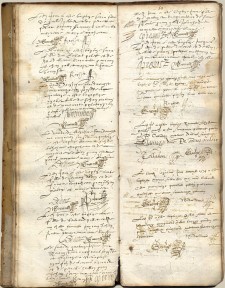

Baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain

Is this the baptismal certificate of the “Father of New France”? Certainly the document is difficult to read; the letters often have to be deciphered as much from their context, as from their appearance. Moreover, in that era the rules of spelling were flexible, to say the least. The different spellings used for the family name of the child and his father can be explained by the fact these names had perhaps previously been written down only rarely. A standard spelling had possibly not yet been adopted.

What are the chances of finding another baptismal certificate dating from this era where the names are identical to those we find in other historical documents? The chances are in fact very small indeed. However, even though the family names of Chapeleau and Champlain are similar, this small difference — understandable as it may be — cautions us not to jump to conclusions. Although the probability is slight, it is still possible that this document has nothing to do with our Samuel de Champlain.

If we are indeed looking at the baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain, we can now say for certain that he was born into a Protestant family, most probably during the summer of 1574. But unless there is another discovery to equal the one made by Mr. Germe, a complete mystery will continue to surround Samuel de Champlain’s date and place of birth.

Baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain, detail

“On Friday, the thirteenth day of August, fifteen hundred and seventy-four, Samuel, son of Antoine Chapeleau and of m [word crossed out] Marguerite Le Roy, was baptized. Godfather, Étienne Paris; godmother, Marie Rousseau. Denors N. Girault.”

In the Footsteps of Jacques Cartier

In 1602 or thereabouts, Henry IV of France appointed Champlain as hydrographer royal. Aymar de Chaste, governor of Dieppe in Northern France, had obtained a monopoly of the fur trade and set up a trading post at Tadoussac. He invited Champlain to join an expedition he was sending there. Champlain’s mission was clear; it was to explore the country called New France, examine its waterways and then choose a site for a large trading factory.

Thus Champlain sailed from Honfleur on the fifteenth of March, 1603, and prepared to follow the route that Jacques Cartier had opened up in 1535. He proceeded to explore part of the valley of the Saguenay river and was led to suspect the existence of Hudson Bay. He then sailed up the St. Lawrence as far as Hochelaga (the site of Montreal.) Nothing was to be seen of the Amerindian people and village which Cartier had visited, and Sault St. Louis (the Lachine Rapids) still seemed impassable. However, Champlain learned from his guides that above the rapids there were three great lakes (Erie, Huron and Ontario) to be explored.

Acadia and the Atlantic Coast

After Aymar de Chaste died in France in 1603, Pierre Du Gua de Monts became lieutenant-general of Acadia. In exchange for a ten years exclusive trading patent, de Monts undertook to settle sixty homesteaders a year in that part of New France. From 1604 to 1607, the search went on for a suitable permanent site for them. It led to the establishment of a short-lived settlement at Port Royal (Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia.)

While the settlers were tilling, building, hunting and fishing, Champlain carried on with his appointed task of investigating the coastline and looking for safe harbours.

The three years stay in Acadia allowed him plenty of time for exploration, description and map-making. He journeyed almost 1,500 kilometres along the Atlantic coast from Maine as far as southernmost Cape Cod.

From Quebec to Lake Champlain

In 1608, Champlain proposed a return to the valley of the St. Lawrence, specifically to Stadacona, which he called Quebec. In his opinion, nowhere else was so suitable for the fur trade and as a starting point from which to search for the elusive route to China. During this third voyage he learned of the existence of Lac Saint Jean (Lake St. John), and on the third of July, 1608, he founded what was to become Quebec City. He immediately set about building his Habitation (residence) there.

Champlain also explored the Iroquois River (now called the Richelieu), which led him on the fourteenth of July, 1609, to the lake which would later bear his name. Like the traders who had preceded him, he sided with the Hurons, Algonquins and Montaignais against the Iroquois. This intervention in local politics was ultimately responsible for the warlike relations that were to pit the Iroquois against the French for generations.

From the Ottawa Valley to Lake Huron

In 1611, Champlain returned to the area of the Hochelaga islands. He found an ideal harbour, and facing it he built the Place Royale (royal square), around which the town would later develop from 1642 onwards.

Even more important, he succeeded in penetrating beyond the Lachine Rapids, becoming the first European (apart from Étienne Brûlé) to start exploring the St. Lawrence and its tributaries as a route towards the interior of the continent. Champlain was so convinced that it was the route to the Orient that in 1612 he obtained a commission to “search for a free passage by which to reach the country called China.” Like most of the explorers who followed after him, he could not carry out his mission without the support of the Amerindian population.

The following year Champlain was induced to make a voyage up the Ottawa River in the course of which he reached Allumette Island. It was his initial foray along the route that was to lead him to the heartland of present-day Ontario and eventually to reach Lake Huron on the first of August, 1615.

That was to be Champlain’s last voyage of exploration. In the years that followed, he devoted all his efforts to founding a French colony in the St. Lawrence valley. The keystone of his project was the settlement at Quebec.

When it capitulated to the English Kirke brothers in 1629, Champlain returned to France, where he lobbied incessantly for the cause of New France. He finally returned to Canada on the twenty-second of May, 1633. At the time of his death at Quebec on the twenty-fifth of December, 1635, there were one hundred and fifty French men and women living in the colony.

About the Film

Broadcast schedule.

- The Journey

- Behind the Scenes

In the Footsteps of Champlain

Animation gallery, media coverage, story elements, the filmmakers, the animators, sound designers, the scholars, educational outreach, lesson plans, champlain timeline, champlain's soundtrack.

- Buy the DVD

Samuel de Champlain first arrived in what is now Canada in May 1603. Over the next thirteen years, he made seven trips into the interior, forging trade alliances with multiple tribes, accompanying them in their wars against the Iroquois, building Québec, and collecting geographic information for his maps and journals. All of his travels were dependent on the knowledge, skills, and technologies of the Algonquin, Wendat, Wabanaki and Innu. These travels formed the basis for his published journals, Les Savauges and Les Voyages .

This map allows you to follow in the footsteps of Champlain, discovering along the way entries from his journals, Amerindian location names, clips from Dead Reckoning ~ Champlain in America , and lesson plans that teachers and students can download to enhance the study of the life and times of Samuel de Champlain.

Lauch the map

Map credits.

The map, They Would Not Take Me There: People, Places, and Stories from Champlain's Travels in Canada, 1603 - 1616, was produced by the Canadian-American Center: A National Resource Center on Canada located at the University of Maine; Stephen J. Hornsby, Director.

The Authors/Cartographers are Michael J. Hermann and Margaret W. Pearce. Translator: Raymond J. Pelletier

© 2008 University of Maine Canadian–American Center, Orono, Maine, USA

For more information on the making of the interactive map, go to: www.umaine.edu/canam/cartography/Champlain.html

www.umaine.edu

The quotes from Champlain’s journals are from the translation edited by Henry Percival Biggar, The works of Samuel de Champlain, 6 v. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1922–36, rep. 1976. The authors also drew on the following books for historical and cartographic interpretations of Champlain’s story:

Heidenreich, Conrad E. 1976. Explorations and mapping of Samuel de Champlain, 1603–1632. Cartographica monograph no. 17. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Litalien, Raymonde and Vaugeois, Denis, eds. 2004. Champlain: The birth of French America. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

Trigger, Bruce G. 1976. The Children of Aataentsic: A history of the Huron people to 1660. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

The authors also drew on many more sources for Native place names and village locations.

A complete bibliography and place name database can be found at the website www.umaine.edu/canam

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Neil Allen, Betsy Arntzen, Nahanni Born, Hans Carlson, Abigail Davis, James Eric Francis, Sr., Robin Harrington, Conrad Heidenreich, Nicole Henderson, Stephen J. Hornsby, Douglas Jack, Anne Knowles, Micah Pawling, Raymond Pelletier, Sam Pepple, Kathryn Slott, Jane Smith, Nancy Strayer, and Roy Wright

Major funding provided by

Funding for the French website provided by

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

Jacques Cartier (1491—1557) French explorer

Great Lakes

Catholic League

Wars of Religion

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing this subject:

Samuel de Champlain

(1567—1635) French explorer and colonial statesman

Quick Reference

(1567–1635)

French explorer and colonial statesman. He made his first voyage to Canada in 1603, and between 1604 and 1607 explored the eastern coast of North America. In 1608 he was sent to establish a settlement at Quebec, where he developed alliances with the native peoples for trade and defence. He was appointed Lieutenant-Governor in 1612; much of his subsequent career was spent exploring the Canadian interior. After capture and imprisonment by the English (1629–32), he returned to Canada for a final spell as governor (1633–35).

From: Champlain, Samuel de in A Dictionary of World History »

Subjects: History

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries, champlain, samuel de (1570–1635), champlain, samuel de ( c. 1570–1635), champlain, samuel de (1567–1635).

View all reference entries »

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'Samuel de Champlain' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 22 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.15.189]

- 185.66.15.189

Character limit 500 /500

British Columbia - Documents - Colonial

History-Documents

Voices from the past

Laws,Acts,Treaties

Choose your documents

Documents in History

Speeches, letters, publications

Survey the crucial events

This Day in our History

Visit the site of History

2023 tour and Travel options

Recent Book Reviews

See our items of the month

VOYAGES OF SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN. II

Date: 1604-1610

Source: NAC/ANC, Elgin-Grey Papers

The "Voyages of Samuel de Champlain" is a significant historical document that provides valuable insight into the early exploration and colonization of Canada by European powers, as well as the relationships between European colonizers and Indigenous nations in the region. Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer and navigator who played a significant role in the early history of Canada. His "Voyages" describe his travels and experiences in the region, including his encounters with Indigenous peoples, his explorations of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes, and his involvement in the founding of Quebec City. The translation of Champlain's "Voyages" by Charles Pomeroy Otis, Ph.D. provides valuable insight into the experiences and perspectives of European explorers and colonizers in Canada in the early 17th century. The translation also highlights the challenges and complexities of cross-cultural interactions between European colonizers and Indigenous nations in the region. Today, the "Voyages of Samuel de Champlain" are considered an important historical document that provides valuable insight into the history of Canada and the wider North American continent. The translation by Charles Pomeroy Otis, Ph.D. is also significant because it has made Champlain's work more accessible to English-speaking audiences and has contributed to the ongoing study and understanding of Canada's rich cultural and historical heritage.

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH

WITH HISTORICAL ILLUSTRATIONS, AND A MEMOIR BY THE REV. EDMUND F. SLAFTER, A.M.

Editor: THE REV. EDMUND F. SLAFTER, A.M.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents

Reference: Article by (Staff Historian), 2023

History Highlights

History & Heritage Tours & Travel

History Web Sites

Special Events

Economic history

Great people

Submit an article

Tour Reviews

History Attractions

Submit Tour Suggestions

2023/Departures

Spotlight Tours

Events and anniversaries

History & Heritage

Tel: 1 604 833-9488

Email: [email protected]

All content and images are protected by copyright to Access History

The Savages or Voyages of Samuel De Champlain

Samuel de Champlain was born in Brouage, France. His date of birth is unknown, but estimated to be around 1570. For exploring North America in the name of France, Champlain was coined as the “Father of New France,” as he established the city of Quebec in Canada (then referred to as New France). As a child Champlain was well educated in cartography and mathematics. His father was a sea captain and taught him navigation from a young age with the inclusion of astronomy.His background also included the titles of soldier and diplomat. In 1603 Champlain embarked to North America in the name of Henry IV, King of France. This account of his first voyage to Canada was written and published in this year with the purpose of exploring the St. Lawrence River in Canada. Alan Taylor, author of American Colonies: The Settling of North America , address the motives behind Frances’ interest in Northern Expansion. Spain had already dominated most of the Caribbean and the southern lands of America. They were powerful and would not hesitate to destroy any competitors of unrelated colonies. Although, at the time, North America was viewed as a safer location for settlement, the French were hesitant because thus far there had been no findings of precious metals nor the very desired “North Passage.” This passage would have given any country the power to monopolize trade with Asia through a channel reaching across to the Pacific Ocean. However, if a passage was not located, the promise of any other fortune from the northern lands was so doubtful that the Emperor of Spain, who could have commissioned a blockade against French exploration of the St. Lawrence River, had said, ” As regards to settling in the Northern Sea, there is nothing to envy in this; for it is of no value, and if the French take it, necessity will compel them to abandon it” (Taylor 92). As the emperor had anticipated, the first French expedition let by Jacques Cartier failed to colonize due to the deathly cold, scurvy, and hostility from the natives. Taylor prefaces the reader that the hostility was “provokes by French thefts and threats” (92). Fortunately for France, the grim experiences shadowing northern expansion did not altogether halt business. A century after the first voyage, the French still managed to maintain a temporary livelihood through the profitable trade of fur and fish. Fish were seasonal but the fur trade of North America was especially valued because over-hunting in Europe had literally killed its own resources for this market.

One of the most interesting points Taylor makes concerns the issue of dependency. Historians have debated the weight of both the Indians and Europeans dependency upon the other. Taylor divulges in the mutuality of the business relationship claiming that the Indians and European powers had, in a sense, advanced the needs and wants of each party, changing their cultures. The Indians began to rely on the Europeans for metals, cloth, and alcohol. The Europeans were then succumbed to the Indian demands of trade and their own countries capitalistic demands.

Samuel de Champlain’s narrative, Voyages of Samuel De Champlain, was translated from French by Charles Pomeroy Otis, Ph.D. It was published in Paris on November 15, 1603 (the same year of the voyage). I believe there are multiple categories this narrative falls under, but all which encompass the major themes of Description and Promotion. The preface to the narrative is as follows:

“Describing: The customs, mode of life, marriages, wars, and dwellings of the Savages of Canada. Discoveries for more than four hundred and fifty leagues in the country. The tribes, animals, rivers, lakes, islands, lands, tress, and fruits found there. Discoveries on the coast of La Cadie, and numerous mines existing there according to the report of the Savages.”

Champlain’s historical descriptions can be assumed for the purpose and goal of northern French expansion and exploitation. Chapter four depicts Champlain’s desire to know every inch of the land. He and his men are guided by natives to see how they travel across lands, where lakes/rivers/and sources of water are, the distance amongst these landmarks, the average time it takes to get there through different seasons, and the course of the water (its speed and how it reacts to weather and time of day) (page 275). It is informative, layered with information and descriptions of the land and sea (mountains, streams, valleys, etc.), and since Champlain wrote and dedicated this account to the Chevalier of the Orders of the King, Lord Charles de Montmorency. It seems safe to inquire that he wishes to also promote himself having dedicated the narrative to a high member of the King’s court. Champlain, like many explorers traveling in the name of their king, are seeking recognition for their trials. Here is his opening letter to the lord:

My Lord, Although many have written about the country of Canada, I have nevertheless been willing to rest satisfied with their report, and have visited these regions expressly in order to be able to render a faithful testimony to the truth, which you will see, if it be your pleasure, in the brief narrative which I address to you, and which I beg you may find agreeable, and I pray God for your ever increasing greatness and prosperity, my Lord, and shall remain all my life, Your most humble and obedient servant, S. Champlain

The thoroughness of his account, displayed within the exasperating depth of detail, also shows his desire for personal gain: “… we continued our course until the 28th, when we fell in with a lofty iceberg. The next day we sighted a bank of ice more than eight leagues long, accompanied by an infinite number of smaller banks, which prevented us from going on. In the opinion of the pilot, these masses of ice were about a hundred or a hundred and twenty leagues from Canada. We were in a latitude 45˚40´, and continued our course in 44˚” (Champlain 232). This passage is from the beginning of the narrative as Champlain sails from Honfleur in Normandy to the Port of Tadoussa, Canada. With the intention of his audience being the lord himself, the reader must keep in mind that his account may not be reliable. The stream of consciousness will be placing Champlain in a favorable light as he attempts to inform the lord, and in turn king, on all factors of this new land. Also, since this is a historical account the reader should maintain some sense of criticism in the way the author describes and explains his experiences which have been translated then commented upon by the editor of this publication. The editor being Rev. Edmund F. Slafter, whom edited on November 10, 1880. For example, the editor notes that when one is considering Champlain’s observations of fruits, trees, and animals (page 263-264) they should understand that he only includes items that are profitable in Europe’s commerce. This footnote hints that there are observations left out, probably because they did not benefit the account whose language is heavily economic and geographical.

Champlain exercised his diplomatic skills with logic and grace. Since he realized early on the benefits of a peaceful relation with his neighboring Indians, he was careful in demonstrating command and authority. He knew that bad relations could lead to Indian attacks and be counterproductive to fur trade and exploring the new country. Although I am only inferring by means of his own account, I felt he was respectful to the local tribes, and merely observed rather than interfered with their customs. The only time I really felt Champlain was probing into the Indian’s culture was in regards to religion. He confesses in his narrative (to the lord) that this was an agreeable time to display tension. He asserts the law and rule of God, and how the Indians have been living in sin because they have not yet warranted faith in the one and only. The grand Sagamore, Anadabijou, remained firm but acknowledged Champlain’s beliefs with kindness. This being a rare moment of the first volume where a conversation of religion is mentioned, showed that conversion was not an important factor in his travels. Yet, coming from a society enthralled in Christianity, I think Champlain wanted to pay compliment to this element, and maintain respect within the king’s court for moral obligation as a European.

The amount of intricate detail surprised me. I could tell Champlain had the mind of a cartographer, and it was very interesting to see how he perceived and observed the land. At times, the narrative was abrupt then bogged down with description. What I found to be most compelling was the way in which Champlain describes the Indians, their culture, and his observations of their movement. Since I am not a soldier nor explorer, it was very engaging to read of a group of people through this mind set. Regarding the physical statue of the Indians, his descriptions were militaristic and complemented their strengths. Compliments usually reigned around ones ability to hunt and travel since that was his focus and intended gain. However, the manners and ceremonies of the Indians were considered barbaric which I think is why Champlain maintained his word choice of savages . This was ironic because he often seemed in awe of the ways the Indians have learned to maneuver through the land, and hunt and fight with such stealth. He also asserts credibility to their warnings of the monster, Gougou, who resides on an inland (290). Since said multiple groups expressed such seriousness and terror when speaking of the monster, he believed there must be an evil presence because with God’s greatness comes the devil’s despair, and they would be foolish in mistrusting this information. It was shocking that this moment connected with Indian culture, was not faulty or barbaric, but believable to Champlain! I did not want to read too much into this, but I think it displays a great example of multi-cultrual superstition.

Trivia: Champlain did not name Quebec. This title was already given by the natives of the land. Quebec in Indian means a narrowing or contraction, signifying the land (253).

Other memorable passages of the narrative : The description of Quebec and its idealness (page 100/253), Vices, lifestyle, and character of the Indians (242) ,The Indians and their belief in God (243-247), Chapter XII: Ceremonies of the Savages before they engage in war (285).

More detailed information from Taylor : The reliance of the Indians on the Europeans (page 98), Five reasons why the French claimed Canada and the goods of the trade (93-100).

BritannicaBiography

WikiBiography

The Narrative: Voyages of Samuel de Champlain

1603 , AlgonquianIndians , Iroquois , Quebec , SamuelDeChamplain

Comments are closed.

Contact & office hours.

Contact Dr. Vander Zee Office Hours: M/W 9-11 & by apt. Office: 22B Glebe St. Rm. 202

- About WordPress

- Get Involved

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

CANADA HISTORY

The founder of Quebec City and one of the most charismatic figures in Canadian history, Samuel de Champlain opened up the St Lawrence river and extended French influence throughout the Great Lakes basin. Samuel de Champlain was born in 1580 and by the time he passed way in 1635, he was known as the father of new France. He was a protestant which was unusual for a Frenchman of that age and grew up on the west coast of France in the seaport of Brouage. He became a sailor and learned the skills of navigation and cartography. Champlain became involved with group who were interested in the fur trade and in 1603 was dispatched, aboard the Bonne - Renommee, for North America. He used his cartographers skills and produced a map of the St Lawrence river and upon his return to France published the map and his account of the trip in his work "Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603". Henry IV of France commissioned Champlain to explore and report further on the new lands in the Americas and in 1604 he helped found the Saint Croix Island settlement on the Bay of Fundy but after a particularly harsh winter the settlers were relocated along the coast of Nova Scotia to an new site named Port Royal. Champlain was able to use his base here to further explore the Atlantic coast for the next few years. During his 1605 - 06 explorations he found no friendly areas where he felt another settlement could be established. He returned to France in 1607 to organize another effort for colonizing the new lands in America. In 1608 Champlain sailed from Honfleur France in command of the Don-de-Dieu along with two other ships. The ships arrived at Tadoussac on the St Lawrence in June of 1608 and continued by small boat on to the site of Stadacona which was the Iroquois village that Jacques Cartier had made contact with. The village was abandoned, possibly due to inter-aboriginal warfare between the Iroquois and the Algonquin's or the devastating effects of European diseases such as smallpox for which the Indians had no natural immunity. On July 3rd, 1608 Champlain landed with his settlers and established a new settlement named Quebec City. They began work immediately and built several multistory buildings. During the first year, once the deep snows of Quebec had fallen, the dreaded disease of scurvy and smallpox also set in. 20 of the twenty eight settlers who stayed for the winter died. In 1609 Champlain made contact and formed friendly relations with the Huron, the Algonquin, the Montagnais and the Etchemin. The mighty Iroquois were their enemy and they appealed to Champlain to help them with their fight against them. Champlain and 9 of his soldiers setout with 300 Algonquin's to explore the Iroquois lands to the south and travelled south along the Richelieu River to Lake Champlain. Champlain and his party had not run into any Iroquois so 7 of the 9 soldiers and most of the Algonquin were allowed to return to Quebec City. Subsequently they ran into a Iroquois war party of over 200 warriors. On July 30tha the 200 Iroquois attacked Champlain, his 2 soldiers and his 30 Algonquin warriors near present day Crown Point, NY. Champlain fired his arquebus at them and killed 2 of the Iroquois leaders with one shot. This was the first encounter that the Iroquois had Experienced with gunpowder and they immediately scattered and fled. The battle lines between the French with the Algonquin's and the English with the Iroquois was now set for the next 150 years. Champlain sailed for France that fall and upon his return in 1611 he traveled upriver from Quebec City to the former village of Hochelega where he established Montreal. He strengthened his relations with the Algonquin and returned to France that fall more intent then ever on gaining additional support for the French colonizing efforts in what was now becoming known as New France. Champlain was named lieutenant and given the power to act as virtual governor in New France. He was empowered to expand the lands of the colony, make treaties with the native people, administer the colonies and explore to the west for the route to China and the Indies. He also married Helene Boullie a 12 year old, on December 30 1610 and received a dowry which he was to use to support his efforts in New France. Champlain returned once again to New France in March of 1613 for the next few years explored through to the Great Lakes and the Georgian Bay area in Ontario. He travelled up the Ottawa River and to Lake Nipissing. The lake and river network in Ontario and Quebec made the birch bark canoe, the natives choice, the easiest way to travel throughout the land. In September of 1615 Champlain departed from Lake Simcoe, in Ontario, with the Huron's and travelled up the Oneida River where the attacked the Iroquois. This attack failed and Champlain was hit in his knee and his leg with two arrows. The Huron's and Champlain retreated back to Huronia where Champlain spent the wither recovering and learning more about the Huron. He returned to Quebec City the following spring. Champlain oversaw the coming of the Jesuit Order in New France and their efforts at converting the natives to Christianity. He administered and continued to explore eastern Canada for the next 20 years and on December 25, 1635 he died after suffering a stroke a month previously. THE VOYAGES TO THE GREAT RIVER ST. LAWRENCE BY THE SIEUR DE CHAMPLAIN, . . . FROM THE YEAR 1608 UNTIL 1612 Credit for establishing the first permanent settlement in Canada belongs to Samuel de Champlain, "The Father of New France." Born in France in 1567, Champlain made his first voyage to the St. Lawrence region in 1603, and in 1604 he took part with De Monts in an abortive attempt to establish a French colony in Acadia. It was on his third voyage, in 1608, that he succeeded in founding a settlement at Quebec. From his base at Quebec he made further explorations, discovering Lake Champlain and exploring the Ottawa Valley. In 1615 he reached Georgian Bay by way of the Ottawa River and Lake Nipissing. The documents given here describe Champlain's arrival at Quebec, the construction of the first buildings in the setttlement, and the difficulties of the first winter. . . . From the island of Orleans to Quebec is one league, and I arrived there on July the third [ 1608 ]. On arrival I looked for a place suitable for our settlement, but I could not find any more suitable or better situated than the point of Quebec, so called by the natives, which was covered with nut-trees. I at once employed a part of our workmen in cutting them down to make a site for our settlement, another part in sawing planks, another in dig. H. P. Biggar, ed., The Works of Samuel de Champlain ( Toronto, The Champlain Society, 1925), II, 24-25, 35- 37, 44-45, 52-53, 59, 63.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents

February Special - Group of 7 Art

February Special - Documents in History

- Document 1: Champlain, The Voyages of Samuel de Champlain

Original Source: Samuel de Champlain, Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France, (Paris: Pierre Le-Mur, 1632), 173-178.

Transcription Source: Samuel Champlain, Voyages of Samuel de Champlain, 1604-1618 , W.L. Grant, ed., (New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1907), 207-212.

On the thirteenth day of the month two hundred Charioquois savages, together with the captains, Ochateguin, Iroquet, and Tregouaroti, brother of our savage, brought back my servant. 1 We were greatly pleased to see them. I went to meet them in a canoe with our savage. As they were approaching slowly and in order, our men prepared to salute them, with a discharge of arquebuses, muskets, and small pieces. When they were near at hand, they all set to shouting together, and one of the chiefs gave orders that they should make their harangue, in which they greatly praised us, commending us as truthful, inasmuch as I had kept the promise to meet them at this Fall. After they had made three more shouts, there was a discharge of musketry twice from thirteen barques or pataches that were there. This alarmed them so, that they begged me to assure them that there should be no more firing, saying that the greater part of them had never seen Christians, nor heard thunderings of that sort, and that they were afraid of its harming them, but that they were greatly pleased to see our savage in health, whom they supposed to be dead, as had been reported by some Algonquins, who had heard so from the Montagnais. The savage commended the treatment I had shown him in France, and the remarkable objects he had seen, at which all wondered, and went away quietly to their cabins, expecting that on the next day I would show them the place where I wished to have them dwell. I saw also my servant, who was dressed in the costume of the savages, who commended the treatment he had received from them. He informed me of all he had seen and learned during the winter, from the savages.

The next day I showed them a spot for their cabins, in regard to which the elders and principal ones consulted very privately. After their long consultation they sent for me alone and my servant, who had learned their language very well. They told him they desired a close alliance with me, and were sorry to see here all these shallops, and that our savage had told them he did not know them at all nor their intentions, and that it was clear that they were attracted only by their desire of gain and their avarice, and that when their assistance was needed they would refuse it, and would not act as I did in offering to go with my companions to their country and assist them, of all of which I had given them proofs in the past. They praised me for the treatment I had shown our savage, which was that of a brother, and had put them under such obligations of good will to me, that they said they would endeavor to comply with anything I might desire from them, but that they feared that the other boats would do them some harm. I assured them that they would not, and that we were all under one king, whom our savage had seen, and belonged to the same nation, though matters of business were confined to individuals, and that they had no occasion to fear, but might feel as much security as if they were in their own country. After considerable conversation, they made a present of a hundred castors. I gave them in exchange other kinds of merchandise. They told me there were more than four hundred savages of their country who had purposed to come, but had been prevented by the following representations of an Iroquois prisoner, who had belonged to me, but had escaped to his own country. He had reported, they said, that I had given him his liberty and some merchandise, and that I purposed to go to the Fall with six hundred Iroquois to meet the Algonquins and kill them all, adding that the fear aroused by this intelligence had alone prevented them from coming. I replied that the prisoner in question had escaped without my leave, that our savage knew very well how he went away, and that there was no thought of abandoning their alliance, as they had heard, since I had engaged in war with them, and sent my servant to their country to foster their friendship, which was still farther confirmed by my keeping my promise to them in so faithful a manner.

They replied that, so far as they were concerned, they had never thought of this; that they were well aware that all this talk was far from the truth, and that if they had believed the contrary they would not have come, but that the others were afraid, never having seen a Frenchman except my servant. They told me also that three hundred Algonquins would come in five or six days, if we would wait for them, to unite with themselves in war against the Iroquois; that, however, they would return without doing so unless I went. I talked a great deal with them about the source of the great river and their country, and they gave me detailed information about their rivers, falls, lakes, and lands, as also about the tribes living there, and what is to be found in the region. Four of them assured me that they had seen a sea at a great distance from their country, but that it was difficult to go there, not only on account of the wars, but of the intervening wilderness. They told me also that, the winter before, some savages had come from the direction of Florida, beyond the country of the Iroquois, who lived near our ocean, and were in alliance with these savages. In a word they made me a very exact statement, indicating by drawings all the places where they had been, and taking pleasure in talking to me about them ; and for my part I did not tire of listening to them, as they confirmed points in regard to which I had been before in doubt. After all this conversation was concluded, I told them that we would trade for the few articles they had, which was done the next day. Each one of the barques carried away its portion ; we on our side had all the hardship and venture; the others, who had not troubled themselves about any explorations, had the booty, the only thing that urges them to activity, in which they employ no capital and venture nothing.

The next day, after bartering what little they had, they made a barricade about their dwelling, partly in the direction of the wood, and partly in that of our pataches ; and this they said they did for their security, in order to avoid the surprises of their enemies, which we took for the truth. On the coming night, they called our savage, who was sleeping on my patache, and my servant, who went to them. After a great deal of conversation, about midnight they had me called also. Entering their cabins, I found them all seated in council. They had me sit down near them, saying that when they met for the purpose of considering a matter, it was their custom to do so at night, that they might not be diverted by anything from attention to the subject in hand; that at night one thought only of listening, while during the day the thoughts were distracted by other objects.

But in my opinion, confiding in me, they desired to tell me privately their purpose. Besides, they were afraid of the other pataches, as they subsequently gave me to understand. For they told me that they were uneasy at seeing so many Frenchmen, who were not especially united to one another, and that they had desired to see me alone; that some of them had been beaten; that they were as kindly disposed towards me as towards their own children, confiding so much in me that they would do whatever I told them to do, but that they greatly mistrusted the others; that if I returned I might take as many of their people as I wished, if it were under the guidance of a chief; and that they sent for me to assure me anew of their friendship, which would never be broken, and to express the hope that I might never be ill disposed towards them; and being aware that I had determined to visit their country, they said they would show it to me at the risk of their lives, giving me the assistance of a large number of men, who could go everywhere ; and that in future we should expect such treatment from them as they had received from us.

Straightway they brought fifty castors and four strings of beads, which they value as we do gold chains, saying that I should share these with my brother, referring to Pont Grav, we being present together; that these presents were sent by other captains, who had never seen me; that they desired to continue friends to me; that if any of the French wished to go with them, they should be greatly pleased to have them do so ; and that they desired more than ever to establish a firm friendship. After much conversation with them I proposed that inasmuch as they were desirous to have me visit their country, I would petition His Majesty to assist us to the extent of forty or fifty men, equipped with what was necessary for the journey, and that I would embark with them on condition that they would furnish us the necessary provisions for the journey, and that I would take presents for the chiefs of the country through which we should pass, when we would return to our settlement to spend the winter; that moreover, if I found their country favorable and fertile, we would make many settlements there, by which means we should have frequent intercourse with each other, living happily in the future in the fear of God, whom we would make known to them. They were well pleased with this proposition, and begged me to shake hands upon it, saying that they on their part would do all that was possible for its fulfilment; that, in regard to provisions, we should be as well supplied as they themselves, assuring me again that they would show me what I desired to see. Thereupon, I took leave of them at daybreak, thanking them for their willingness to carry out my wishes, and entreating them to continue to entertain the same feelings.

- Table of Contents

- How to use this book

Thinking through Canada's Early History

- Introduction

- Interpretation 1: Peace, "Colonialism and the Words We Choose"

- Interpretation 2: Luby et al., "(Re)naming and (De)colonizing the (I?)ndigenous People(s) of North America - Part I"

- Interpretation 3: Luby et al., "(Re)naming and (De)colonizing the (I?)ndigenous People(s) of North America - Part II"

- Discussion Questions

- Review: Thinking Through Canada's Early History

Assessing the Bering Land Bridge

- Document 1: Jose de Acosta, The Naturall and Morall Historie of the East and West Indies

- Interpretation 1: MacEachern, “A Theory, in Practice: Back to the Bering Land Bridge”

- Review: Assessing the Bering Land Bridge

Ceremonies of Possession

- Document 2: Winthrop, The History of New England

- Interpretation 1: Reid, "The Doctrine of Discovery and Canadian Law"

- Review: Ceremonies of Possession

Settling a New France

- Document 1: The Loudunais and Mirebalais, c. 1635

- Document 2: Map of French Settlement around Quebec, 1709

- Document 3: A General Plan of Annapolis Royal, 1753

- Document 4: Kalm, Travels into North America

- Interpretation 1: Kennedy, Marshland Colonization in Acadia and Poitou during the 17th Century

- Review: Settling a New France

Colonialism and Christianity

- Document 1: Of Various Obstacles and Difficulties Encountered

- Document 2: Marie de l'Incarnation: Letter 32: To one of the Good Brothers

- Interpretation 1: Word Cloud Analysis of the Jesuit Relations

- Review: Colonialism and Christianity

Treaties in Historical Context

- Document 1: Dish with One Spoon Treaty (c. 1500 – present)

- Document 2: Two Row Wampum (c. 1613 – present)

- Document 3: Great Peace of Montreal (1701)

- Document 4: Peace and Friendship Treaty Ratification (1728)

- Document 5: Murray Treaty (1760)

- Document 6: The Royal Proclamation of 1763

- Document 7: Treaty of Niagara (1764)

- Document 8: London Township Treaty (1796)

- Document 9: Selkirk Treaty (1817)

- Document 10: Numbered Treaty One (1871)

- Interpretation 1: Jaime Battiste on Mi’kmaw Treaties

- Interpretation 2: Murray Sinclair on the Royal Proclamation of 1763

- Interpretation 3: Hayden King on Anishinaabe Treaties

- Review: Treaties in Historical Context

Were the Black Loyalists Loyal?

- Interpretation 1: Cahill, "The Black Loyalist Myth in Atlantic Canada"

- Interpretation 2: Walker, "Myth, History and Revisionism"

- Review: Were the Black Loyalists Loyal?

Perspectives on the Fur Trade

- Document 1: Country Marriages

- Document 2: Jean-Baptiste Point du Sable

- Document 3: Diary of Nicholas Garry

- Review: Perspectives on the Fur Trade

Local Economies and Global Trade

- Document 1: Colonial Censuses

- Interpretation 1: Maitland's Moment

- Review: Local Economies and Global Trade

Pathways to British North America

- Document 1: The Life of Josiah Henson

- Document 2: Roughing it in the Bush

- Document 3: The Life and Adventures of Wilson Benson

- Review: Pathways to British North America

Rebellion or Revolution?

- Document 1: 92 Resolutions

- Document 2: 10 Resolutions

- Interpretation 1: Henderson: "Banishment to Bermuda: Gender, Race, Empire, Independence..."

- Review: Rebellion or Revolution?

First Peoples and Schooling

- Interpretation 1: Peace, "Borderlands, Primary Sources, and the Longue Durée"

- Document 1: Report to the New England Company

- Document 2: History of the New England Company... during the two years, 1869-1870

- Review: First Peoples and Schooling

Considering Gum Shan

- Document 1: Douglas to the Duke of Newcastle

- Document 2: Hazlitt, The Great Gold Fields of Cariboo

- Interpretation 1: Chung, Kwong Lee & Company and the Early Trans-Pacific Trade

- Review: Considering Gum Shan

Debating Confederation

- Document 1: Confederation Debates

- Interpretation 1: Sean Kheraj

- Review: Debating Confederation

The Trial of Louis Riel

- Document 1: The Prisoner's Address

- Review: The Trial of Louis Riel

Working in the Nineteenth Century

- Document 1: Report of the Royal Commission on the Relations of Capital and Labor

- Interpretation 1: Word Cloud

- Review: Working in the Nineteenth Century

Drugs, Race, and Moral Panic

- Document 1: Emily Murphy, The Black Candle

- Interpretation 1: Yvan Prkachin