- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

- 843-763-7551

- Schedule A Tour

- Gullah Language

- Gullah Words

- Hear and Read Gullah

- Did you know that…

- Catfish Row

- Black Slave Owners

- Denmark Vesey’s

- Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church

- Hexes, Fixes, Roots

- Jones Hotel

- Old Slave Mart

- Philip Simmons Blacksmith

- Slave Quarters

- Sweetgrass Market

- The Patty Wagan

- The Underground Railroad

- The Whipping House

- Reservations

- About Alphonso Brown

- Gullah Bookstore

Sites Visited

- Sites Visted

Managed by Sweetgrass Marketing

The Owens-Thomas House and Slave Quarters

One of the most historically significant homes in Savannah, the Owens-Thomas House is a great example of how life was in 1800s Savannah Georgia

The regal Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters is arguably the most popular tourist attraction in Savannah, Georgia. The National Historical Landmark sits on the north-east side of Oglethorpe Square , emanating quintessential appeal. An inclination toward admiring the home's splendor is inevitable.

Its significance, however, does not lie in its appearance but rather in the events that unfolded within its walls. The dwelling was once home to many living in perpetual servitude, some who remain unnamed, and whose stories we are just beginning to discover. While often regarded as an architectural gem, the home is, in fact, an embodiment of inequality, a manifestation of humanity's perceived differences, and the antiquated views of the antebellum south.

About the Owners

The construction of the structure we now refer to as the Thomas-Owens House was commenced in 1816 for slave trader and merchant, Mr. Richard Richardson, and his wife, Frances. Upon the home's completion in 1819, the couple, their six children, and nine slaves moved into the estate.

Three years after moving in, the Richardsons faced an unexpected wealth decline, due in part to the financial crisis that emerged after the Napoleonic wars. While the battles were ongoing, England depended on the United States for supplies. Once the conflict ended, and soldiers returned to their designated trades, the demand for American-made products diminished significantly.

Richardson also experienced personal hardships during this time after his wife and two of his children passed away. Richardson put the house on the market in 1822 and moved to New Orleans, where he had been selling and purchasing slaves for years. In 1833, the slave trader died at sea during a journey from Le Havre, France to New Orleans.

In the mid-1820s, the Bank of the United States acquired the home and rented it to Mary Maxwell, who turned it into a boarding house. One of the boarding house's most notable guests was Marquis de Lafayette, a French military officer, and American Revolutionary War veteran, who stayed in the home while touring the country.

The mayor of Savannah, George Welshman Owens, acquired the home in an auction for 10,000 dollars. In 1830, he moved into the house with his large family and 15 slaves. Owens owned an estimated total of 400 slaves throughout his plantations. The estate remained in the Owens family until 1951 when his granddaughter Margaret Gray Thomas passed away. Margaret Thomas did not have any direct heirs, so she willed the home to the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences. The dwelling was restored and opened to the public three years later.

Architecture and Interior Design

Savannah's thriving cotton industry brought immense success to previously impoverished European immigrants. This new-money generation created unspoken competition amongst the wealthy, pressured not only to demonstrate their riches but also to leave behind an incredible legacy. Consequently, many expensive mansions were erected, each one more extravagant than the last.

The large home, designed by English architect William Jay, is an excellent example of Regency architecture in the south. The style, influenced by the rule of King George IV, was appealing and coveted in the western world. King George IV, himself, was considered to be a man of impeccable taste with a keen eye for detail. His excessiveness, combined with inspiration taken from ancient Greek and Roman architecture, impacted how buildings were designed and furnished during the early to mid-19th century.

In its entirety, the Owens-Thomas House features beautiful expensive details, with the formal dining room being the home's most luxurious space. The large dining area has a unique, rounded shape, mahogany furnishings, and intricate plasterwork. Unlike the other faux marble, faux wood, and cast iron-adorned rooms, the formal dining room displays a solid marble fireplace, wood carved tables, and bronze hardware.

The gleaming appearance of the home, however, is dimmed under a more sinister light as we travel across the estate's peaceful garden and towards the Slave Quarters. There we discover the key to the home's beauty: slavery. The fully carpeted floors, and nook and cranny-filled plasterwork don't seem so desirable when we realize the maintenance involved in a property this size. The aesthetic of the home is also hindered when we see how the people that cared for it lived. To stand between the main house and the slave quarters is to experience - within just a few feet - the stark contrast between social classes in 19th century Savannah.

The Slave Quarters

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of the home's history is the arduous slave labor required for its maintenance and the inhumane treatment that took place within its boundaries. The Slave Quarters were a two-story, six-chamber building where freedom-deprived African Americans lived. After being ripped from their home and transported as cargo to another country, these men, women, and children were thrown into cramped, deteriorated rooms, and forced into labor. They were verbally mistreated, physically, and sexually abused, punished for practicing their religions, and speaking their native language.

The dull, unfinished quarters they resided in were furnished with subpar bare essentials: a brick fireplace for cooking, deep wooden crates with a sheet and pillow for sleeping, and candlesticks for illumination. As new people were brought in to serve the affluent families, the lack of proper space forced many to sleep on the floor, resting uncomfortably before their long, tiresome shift. Their days consisted of cleaning, cooking, and raising the family children.

Every element in the main home required maintenance, and the grander the decor, the more slave labor was needed. The silver and china were looked after with extreme care by the family's enslaved butler, who also prepared the meals. The ornate crown moldings were dusted daily. The symbol of wealth that was a carpeted room required weekly cleanings that involved it being taken apart, beaten, steam cleaned, and reinstalled.

After slavery was abolished in 1865, the building was rebranded as "servant quarters," while still housing many of the same formerly enslaved individuals. Freedom was not enough as the abuse and lack of education had crippled their autonomy. Not having the means to move forward meant that those freed would need to let go of any hope of being independent and embrace their new roles as servants.

The stories of those who serviced the privileged are often missing from our narratives. Records are scarce since teaching slaves to read or write was a crime at the time, believing that educated African-Americans would revolt against their masters. Although some managed to get an education - thanks to clandestine schools like the one run by the celebrated Jane DeVeaux in her family home, it seems like the families that lived in the mansion made sure their slaves remained illiterate. The truth of the past has unfortunately been replaced by a romanticized old-world ideal of wealth, failing to highlight the inevitable byproduct of power: oppression.

Other Historic Homes

- 432 Abercorn

- The Andrew Low House

- The Davenport House

- The Gordon Low Birthplace

- The Green-Meldrim House

- The Harper-Fowlkes House

- The Mercer-Williams House

- The Owens-Thomas House

- The Scarbough House

- The Sorrel Weed House

- The Willink House

Our Savannah Tours

- Historic Church Tour

- Bonaventure Cemetery Tour

- Colonial Park Cemetery Tour

- Stories of old Savannah

Visiting the Owens-Thomas House

Visitor Information

The Telfair Museum currently offers walk-in guided tours of the Thomas-Owens House & Slave Quarters . Visit the estate for a dose of history and reality that offers a true look into Savannah’s interesting yet troublesome past.

Tour Hours Sunday & Monday: Noon - 5:00 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday: 10:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m.

Location 124 Abercorn Street Savannah, GA 31401

Do you want to learn more about Savannah?

Gallivanter offers the widest variety of highly-rated tours in Savannah. Make sure to book one for your trip to Savannah!

Whitney Plantation: Tour of an American Slavery Museum

By: Author Dave Lee

Posted on Last updated: October 7, 2021

In planning my third trip to New Orleans , going on a Whitney Plantation tour was high on my to-do list.

I wanted my first southern plantation experience to be more than a photo-op.

The Whitney Plantation is the first museum dedicated to American slavery.

The 2,000-acre sugar plantation dates back to 1752 when it was developed by German immigrants Ambroise Haydel and his wife.

According to the plantation's website , it stayed in their family for 115 years, before being “sold to Bradish Johnson, a major businessman and plantation owner with roots in Louisiana and New York.”

Fast forward to the early 2000s, and John Cummings, a successful lawyer from New Orleans, purchases the property as a real estate investment.

Over time, he realizes how little he knows about the history of the slaves who once worked on such properties.

And as he learns more, he decides to invest millions of dollars of his own money into turning the plantation into a museum honoring their experience.

Table of Contents

The Antioch Baptist Church

The children of whitney, the wall of honor, allées gwendolyn midlo hall, the field of angels, the slave quarters, robin's blacksmith shop, the kitchen, the big house, getting to whitney plantation, whitney plantation tour.

The Whitney Plantation opened in December 2014.

Unlike most plantation tours that focus on the large houses of the owners, the Whitney Plantation tour is given from the slaves' perspective.

Visitors meet their guide in the Welcome Center, which also serves as a tasteful gift shop, primarily offering books on slavery.

The 90-minute walking tour begins with a visit to the Antioch Baptist Church, which was built in 1870 on the eastern side of the Mississippi River.

Slaves would come from nearby plantations to worship there.

The church was donated and relocated to the Whitney after its community opened a new, larger one in 1999.

Walking inside the historic wooden structure, one's attention is drawn to the lifesize sculptures of child slaves.

Their innocence and vacant eyes evoke empathy.

“ The Children of Whitney , a series of sculptures by Ohio-based artist Woodrow Nash , represent these former slaves as they were at the time of emancipation: children.”

The children bring the space to life in a way I've never experienced in a museum before. We would see more of them as the tour continued.

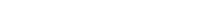

Next, we visited The Wall of Honor, which memorializes stories from the 350 slaves who worked on the Whitney Plantation.

Etched into the granite slabs, in their own words, are horrific, heartbreaking accounts of their treatment.

My words certainly won't do these stories justice, so I took a few photos to share here.

“The most crue master in St. John the Baptist Parish during slavery time was a Mr. Valsin Mermillion. One of his cruelties was to place a disobedient slave, standing, in a box, in which there were nails placed in such a manner that the poor creature was unable to move. He was powerless even to chase the flies or sometimes, ants crawling on some parts of his body.” — Mrs. Webb, Louisiana Slave

“We jus' have co'n braid and syrup and some times fat bacon, but when I et dat biscuit, she comes in and say, ‘What dat biscuit?' I say, ‘Miss, I et I's so hungry.' Den she grab dat broom and start to beatin' me over de head wid it and callin' me low down nigger and I guess I jes' clean lost my head 'cause I know'd better fan to fight her if I knowed anything ‘tall, but I started to fight her and de driver, he comes in and he grabs me and starts beatin' me wid dat cat-o'-nine tails, and he beats me 'till I fall to de floor nearly dead. He cut my back all to pieces, den dey rub salt in de cuts for mo' punishment, I's only 10 years old.” — Jenny Proctor

Following The Wall of Honor, we had a few minutes to walk through a memorial to the 107,000 Africans enslaved in Louisiana during the 18th and 19th centuries.

The memorial is named after Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, a historian, teacher, and author who compiled a database known as “Afro-Louisiana History and Genealogy, 1719-1820.”

The black granite walls are filled with more names, stories, and images of the enslaved.

See also: Zanzibar's Prison Island in Tanzania

The Field of Angels recognizes the 2,200 slave children born in St. John the Baptist parish between 1823-1863, many of whom died before their second birthday.

Most were buried on the grounds of the plantation; some were buried in the cemetery of a nearby Catholic church.

“Death rates on Louisiana’s cane plantations were relatively high compared to cotton or tobacco plantations. Many of the children honored at this memorial died of diseases, but some of them died under tragic circumstances such as being hit by lightning, drowning, or burning.” — Whitney Plantation website

The striking statue at the center of the memorial is “Coming Home” by Rod Moorehead. It depicts a black angel carrying a baby up to heaven.

The Whitney originally had 22 cypress slave cabins.

However, in the 1970s, all but two were destroyed to make more room for larger trucks and more modern harvesting equipment.

Some of the family owners, who were focused on selling the property rather than preserving it, believed the value would increase as a result.

The rest of the cabins visible on the Whitney Plantation were purchased from the Myrtle Grove Plantation.

The Children of the Whitney make another appearance on the porch of a slave cabin.

This particular cabin had a wall in the middle, splitting the single building up for use by two or more people.

Each side had a fireplace, a bedroom, and what appeared to be a sitting room.

Constructed in Pennsylvania in 1868, this rusty metal jail was donated to the Whitney by a Louisiana couple.

The metal box, about the size of a shipping container, would have been used to hold slaves who were caught trying to escape.

It is similar in design and appearance to what was used during slave auctions, as well.

As the Whitney Plantation tour continued, we passed by Robin's Blacksmith Shop.

According to a plaque, Robin was an enslaved man born in 1791 on the east coast of the U.S.

His job was to provide all the metalwork for the plantation, including “horseshoes, nails, hinges, and curtain rods.”

Built in the early 1800s, Whitney's kitchen is the oldest detached kitchen in Louisiana.

Here, a slave was responsible for cooking all the meals for the plantation owner's family.

Pigeon holes were cut in the roof so that the loft could be used as an additional pigeonnier (a space created for pigeons to nest).

Last but not least, we walked from the kitchen to The Big House, where the plantation owners lived.

The house was rebuilt in its current form sometime before 1815, making it a little over 200 years old.

It's an excellent example of Spanish Creole architecture.

Each floor has seven rooms. However, the guided tour only passes through the dining room in the middle of the ground floor.

There's not much to see. I found it the least interesting part of the experience.

Overall, I found the effort to present plantation life from the slaves' perspective to be a success.

Walking the grounds where so many indentured men, women, and children toiled without choice, were mercilessly tortured, and sexually abused is a heavy experience.

The investment in bringing a church, slave cabins, and original artwork to the grounds has paid off.

The Children of the Whitney, especially, give faces to the names and stories.

Seeing them throughout the tour reminds you what happened there was real, not some abstract history lesson.

There's no public transportation from New Orleans to the Whitney Plantation, so the easiest thing to do is sign up for a tour, which includes roundtrip bus transportation (from the French Quarter) and admission for a guided tour.

I went in partnership with Gray Line , which sells adult tickets for $69. Children age 6-12 cost $35 each.

The whole trip takes five hours. To make a full day of it, you can add a second plantation for an additional cost.

I also visited Oak Alley Plantation, where the focus is on the owners' home and oak trees. It's a beautiful property, and there are some slave cabins to see; however, the impact wasn't the same.

If you have a car and prefer to visit Whitney Plantation independently, it's recommended you buy your tickets in advance. Adult admission is $25; children age 6-18 are $11 each.

Where to Stay in New Orleans: The Quisby is centrally located in the Garden District, a 15-minute walk from the French Quarter. Free breakfast, an on-site bar open 24/7, and dorms starting at just $18 are a few of the reasons to stay here. Click here to check availability

My trip to New Orleans was in partnership with New Orleans & Company and The Quisby; this tour was provided compliments of Gray Line.

Dave is the Founder and Editor in Chief of Go Backpacking and Feastio . He's been to 66 countries and lived in Colombia and Peru. Read the full story of how he became a travel blogger.

Planning a trip? Go Backpacking recommends:

- G Adventures for small group tours.

- Hostelworld for booking hostels.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Your subscription makes our work possible.

We want to bridge divides to reach everyone.

Get stories that empower and uplift daily.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads .

Select free newsletters:

A selection of the most viewed stories this week on the Monitor's website.

Every Saturday

Hear about special editorial projects, new product information, and upcoming events.

Select stories from the Monitor that empower and uplift.

Every Weekday

An update on major political events, candidates, and parties twice a week.

Twice a Week

Stay informed about the latest scientific discoveries & breakthroughs.

Every Tuesday

A weekly digest of Monitor views and insightful commentary on major events.

Every Thursday

Latest book reviews, author interviews, and reading trends.

Every Friday

A weekly update on music, movies, cultural trends, and education solutions.

The three most recent Christian Science articles with a spiritual perspective.

Every Monday

Plantation tours bypass the ‘big house’ to focus on the enslaved

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

- By Noah Robertson Staff writer

- Lindsey McGinnis Correspondent

January 15, 2021

For over a century, the history of American slavery has been insufficiently and inaccurately told, typically privileging the enslavers over the enslaved. But efforts to correct the record are underway on former plantations from Wallace, Louisiana, to Medford, Massachusetts. Some sites no longer include the manor house in their tours, sharing details instead about the lives of the enslaved people.

“We are the stewards of spaces that can offer answers,” says Michelle Lanier, director of the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites and Properties. “There’s a grand healing that I think is attempting to emerge through our nation’s greatest wound.”

Why We Wrote This

By portraying slavery accurately and inclusively, some former plantations are doing their part to combat racial injustice. They hope letting the past inform the present will help heal “our nation’s greatest wound.”

At the former plantation of President James Monroe in Virginia, descendants of the enslaved are helping to right the record. “The true, deep-down hope is that this could be a roadmap to something bigger that our whole country can get behind,” says Jennifer Stacy, a member of the site’s Council of Descendant Advisors.

Meanwhile, at the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Massachusetts, Executive Director Kyera Singleton is working to expand the site’s role in social justice work by helping people learn from the past. “This history of injustice ... will keep happening if we don’t actually confront systemic inequalities and racism in this country,” she says.

Beside the long path to the Wappoo Creek stand symmetrical rows of Southern live oaks, arranged like the pillars of a temple. Down the dirt road below, shaded by the leaves and long beards of Spanish moss, Toby Smith leads her first tour of the morning to the Wappoo’s marshy banks. Then she asks them to look right.

Miles away, past mud flats, fishing boats, and the Ashley River, sits Charleston, South Carolina. If they drifted on the water for about an hour, they’d hit the city harbor. If they floated past for another three months, she says, they’d arrive on the West Coast of Africa.

That’s how Ms. Smith says she starts her tours of McLeod Plantation Historic Site, where she’s worked as a guide for the past two years. Her trip to the milky green waters of the Wappoo Creek is a regular pilgrimage, designed to help visitors imagine the journey of enslaved Africans who once stood on the same land. Starting near the water, she says, lets the tour walk in their footsteps.

For the next hour, Ms. Smith explains in a phone interview, she guides her group through the plantation grounds and lets them ask questions about its 37 acres. They pass the cramped slave quarters and palatial manor house. They pause at the slave cemetery and walk into the fields of sea island cotton, still growing. Inside the cotton gin house, they gaze at small dimples in the walls. Some days, Ms. Smith lets the group know that those are fingerprints left by enslaved children who hand-molded the bricks.

“We are walking on the blood, sweat, and tears of real human beings,” she often tells visitors. “That has a very profound impact on people. ... Sometimes you don’t have to say anything. It’s just the presence.”

McLeod is among a growing number of sites that recognize the power of that presence. Its vision is to interpret the legacy of slavery, where slavery took place. Behind that, the focus is a recognition that the history of American slavery has been insufficiently and inaccurately told, often privileging the enslavers over the enslaved. Gradually, that’s changing as historians acknowledge that every life on plantations like McLeod mattered.

Reconstructing the lives of enslaved people is difficult, but from Wallace, Louisiana, to Medford, Massachusetts, many sites on the ground zero of slavery are accepting their role in that effort. Recent calls for racial justice have demanded a reckoning with wrongs that date back centuries. Places like McLeod harbor that history – and with it hope for catharsis.

“We are the stewards of spaces that can offer answers,” says Michelle Lanier, director of the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites and Properties. “There’s a grand healing that I think is attempting to emerge through our nation’s greatest wound.”

“Basically we’ve been miseducated”

For many Americans, that wound has grown more painful with the way it has historically been taught, says Derrick Alridge, a professor at the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education and Human Development.

Dr. Alridge recently chaired Virginia’s Commission on African American History Education, charged with auditing the state’s efforts to teach Black history. Released last August, its 80-page report identifies faults endemic to curricula across the country.

Long dominant have been so-called master narratives, which teach American history through the lives of U.S. presidents or other “great men.” People of color – and especially African Americans – are often segregated into sections that cover only “messianic figures,” like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Regular Black Americans, including enslaved people, are rarely given space.

“You can’t erase history. You can ignore it, which is something we’ve done for centuries,” says Jody Allen, an assistant professor of history at William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. “There’s a real understanding that basically we’ve been miseducated in this country.”

Understanding the legacy of slavery, says Professor Alridge, is crucial to addressing its impacts today. Connecting historical dots – from the Black Lives Matter movement to the civil rights movement to abolition – puts the present in context and makes history real, he says.

At a place like McLeod, where that history is as real as it can get, the stakes for getting it right are high.

Bypassing the “big house”

Just as the historical narrative has traditionally focused on the owning class, plantation museums have orbited the “big house,” says Shawn Halifax, cultural history interpretation coordinator for the Charleston County Park & Recreation Commission, which runs McLeod.

Typically, visitors marvel at the opulent homes of slave owners, he says, while enslaved people are treated as footnotes. “The furnishing of these former dwellings oftentimes tends to create a type of nostalgia, which is the very thing that through our interpretation we’re trying to move beyond,” says Mr. Halifax.

At McLeod, the big house is empty, and the tour does not take visitors inside. Interpreters teach about William Wallace McLeod – the plantation’s owner and a Confederate soldier – but they focus on the 100 or so people enslaved on the site, telling their stories and saying their names.

More than 800 miles southwest, Whitney Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana, takes the same approach. Before the pandemic, the former sugar cane plantation attracted around 100,000 visitors each year, says Executive Director Ashley Rogers.

It, like McLeod, teaches slavery from the perspective of enslaved people and will soon empty its big house. “We’re trying to use this plantation as a vehicle to get people to understand the system of slavery more broadly,” says Ms. Rogers.

One way they do that is by making sure Whitney’s history speaks to today. Only two of the original 22 slave quarters are still standing, but they aren’t relics. After the Civil War, many of Whitney’s enslaved people had little choice but to keep farming sugar cane and living in their same quarters. Some of their descendants stayed until 1975.

“Our entire point of what we’re trying to do is to teach people about the past so that they understand the present,” says Ms. Rogers. “If history doesn’t have an impact that you can still feel, then it’s just an interesting story.”

Seeing today through the lens of yesterday

Sometimes the past and the present collide.

Jennifer Stacy grew up near Charlottesville, Virginia, about 10 miles from Highland, the plantation of President James Monroe. Her family used to drive past the site on their way into town, and she would read the sign: Home of James Monroe. She knew about slavery, and she knew her grandfather was also a Monroe. Even as a girl, she sensed the two were somehow connected.

Decades later, Ms. Stacy learned that she’s a descendant of Ned Monroe, an enslaved man at Highland who helped build the University of Virginia. Three years ago, she joined the estate’s newly formed Council of Descendant Advisors , a group of 10 descendants who advise the site on its efforts to tell a fuller story.

“It’s now shared authority, where the goal is to reinterpret the history there and to get it right,” Ms. Stacy says. “The true, deep-down hope is that this could be a roadmap to something bigger that our whole country can get behind and start doing, because it is who we are.”

Highland, like other plantation sites across the country, is researching the lives of those enslaved on its land – constructing genealogies, reviewing oral histories, and panning streams of centuries-old documents. The task, though, requires swimming against the currents of history. Researchers engaged in this work often face a dearth of primary sources, low funds, and small staffs.

This is especially true in the North.

Records show slavery is central to Northern states’ histories. Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and other influential figures in the North who supported abolition owned slaves, and New England colonies played a critical role in the transatlantic slave trade. There were enslaved people in every Rhode Island township, historians say, and local merchants bankrolled more than 500 voyages to West Africa during the Colonial period. All the other colonies combined sent 189.

But Americans’ postbellum memory associates slavery almost exclusively with former Confederate states. Research on slavery outside the South is thin, and long-held notions of Northern heroism can chill attempts to learn more.

Correcting the record

“There is this great desire for people to want us to have made greater strides, but we are working against 50-plus years of America’s educational system,” says Lavada Nahon, interpreter of African American history for the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

While many sites in the North are adopting an approach similar to Whitney’s or McLeod’s, rediscovering an entire state’s role in slavery is a massive effort in historical forensics.

Artifacts have been mislabeled and misinterpreted, and important history has been lost in translation. In New York, this could mean translating early documents from Dutch to English or interpreting confusing terminology – a recent paper published by the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site in Albany argues that the “servants” listed in Alexander Hamilton’s cash book were actually enslaved people. Even cursive handwriting can challenge the newer generation of historians.

“It is not as if we are choosing not to honor our ancestors,” Ms. Nahon says. “It is time-consuming work.”

It’s also work that evolves. Heidi Hill, historic site manager at Schuyler Mansion, says the site has been compiling research on free and enslaved Africans since the 1980s. They’ve long incorporated names, numbers, and the type of work enslaved people did into their tours and other events.

“But now we’re asking different questions,” says Ms. Hill. “Who were these people? Where did they come from? Who were their family members? How did they connect?”

Piecing together the lives of enslaved people

When communicating with a largely miseducated public, making the historical narrative more inclusive requires a powerful commitment.

Kyera Singleton heard about the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Massachusetts, at a conference in 2019. She’d grown up in the Northeast, studied slavery, and still had no idea there were freestanding slave quarters in the North. But while the scholar in her wanted to visit, Ms. Singleton had a familiar fear: that the history would be whitewashed and the trip would be more painful than illuminating.

Still, she decided to go and soon learned that the site had undergone a dramatic rebranding in 2005, bringing enslaved people into focus.

“Every room that we went in, we talked about the enslaved people,” she says. “It shows that their names matter, their lives matter, their history matters.”

Ms. Singleton was so impressed that she applied to work at the museum, and since April of last year, she has served as executive director. In her new role, Ms. Singleton is eager to uncover how the enslaved people who lived at the site experienced slavery, resisted it, and advocated for their freedom – a challenging mission that includes archaeological and archival research, partnering with universities, and a lot of guesswork.

“You might not find all of the information that you want,” she admits. “And that’s a part of the cruelty of history in many ways – whose lives were deemed important enough to document versus those whose lives were deemed unimportant.”

The paucity of first-person accounts of slavery has long been an excuse to avoid difficult conversations, says Cordell Reaves, historic preservation programs analyst for New York’s Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

“That is … a terrible disservice to the general public,” he says. “[Visitors] can be engaged in having a conversation around ongoing research, even if we are not absolutely certain about the outcome.”

Lately, Ms. Singleton has been working to increase the visibility of the Royall House and Slave Quarters, hoping to expand the site’s role in present-day social justice movements by helping communities understand that last year’s assaults against Black people, including by the police, were not unique.

“This history of injustice has been happening long before 2020,” says Ms. Singleton. “It will keep happening if we don’t actually confront systemic inequalities and racism in this country.”

Interrupting the cycle of history

The country has chosen not to confront the history before, and the history repeats. Generations come; generations go. The next sometimes forgets the last.

But places like McLeod remember, says Ms. Smith, the interpreter near Charleston.

Her tour ends, she says, at the Wisdom Oak, thought to be at least 200 years old. Ms. Smith asks her group to imagine what memories are caught in its branches.

Ms. Smith tells her group that she is a direct descendant of slaves, some of whom may have lived just 20 miles from McLeod. Her great-great-grandmother Idella was taken from modern-day Ghana in the 1840s, after the slave trade was illegal in America. Ms. Smith is alive today because Idella survived that voyage at the age of 8, mourned her losses alone, and started a family, living until 1941.

This work is “a way for me to keep them alive, share their memories, and also to give them a measure of honor and dignity that they never had in life,” says Ms. Smith.

Then, at the roots of the Wisdom Oak, she tells her group about a visitor to McLeod six years ago. A month before Dylann Roof killed nine members of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, he visited McLeod and took pictures of himself there.

“People physically recoil at the fact that he was on the property,” says Ms. Smith. “But it gives us an opportunity to talk about hatred and why we cannot let hate end the conversation.”

There’s no agenda, no judgment, no attempt to sanitize what went on then or now, she says. It’s just a moment to pause, to acknowledge the pain, and to ask what they’ll do about it.

Maybe listen – to each other, or the ancient oak above them.

“Ultimately, we hope that it could be a place always of conversation and healing,” says Ms. Smith, “and people will leave better than when they came.”

Walter Houston Robinson contributed to this report.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the title of Whitney Plantation Executive Director Ashley Rogers and the spelling of Derrick Alridge.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Unlimited digital access $11/month.

Digital subscription includes:

- Unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

- CSMonitor.com archive.

- The Monitor Daily email.

- No advertising.

- Cancel anytime.

Related stories

A sanctuary of social and spiritual justice: commentary on ebenezer church, q&a with william g. thomas iii, author of ‘a question of freedom’, storied narrative’s translation prompts a fresh look at the slave trade, share this article.

Link copied.

Dear Reader,

About a year ago, I happened upon this statement about the Monitor in the Harvard Business Review – under the charming heading of “do things that don’t interest you”:

“Many things that end up” being meaningful, writes social scientist Joseph Grenny, “have come from conference workshops, articles, or online videos that began as a chore and ended with an insight. My work in Kenya, for example, was heavily influenced by a Christian Science Monitor article I had forced myself to read 10 years earlier. Sometimes, we call things ‘boring’ simply because they lie outside the box we are currently in.”

If you were to come up with a punchline to a joke about the Monitor, that would probably be it. We’re seen as being global, fair, insightful, and perhaps a bit too earnest. We’re the bran muffin of journalism.

But you know what? We change lives. And I’m going to argue that we change lives precisely because we force open that too-small box that most human beings think they live in.

The Monitor is a peculiar little publication that’s hard for the world to figure out. We’re run by a church, but we’re not only for church members and we’re not about converting people. We’re known as being fair even as the world becomes as polarized as at any time since the newspaper’s founding in 1908.

We have a mission beyond circulation, we want to bridge divides. We’re about kicking down the door of thought everywhere and saying, “You are bigger and more capable than you realize. And we can prove it.”

If you’re looking for bran muffin journalism, you can subscribe to the Monitor for $15. You’ll get the Monitor Weekly magazine, the Monitor Daily email, and unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

Subscribe to insightful journalism

Subscription expired

Your subscription to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. You can renew your subscription or continue to use the site without a subscription.

Return to the free version of the site

If you have questions about your account, please contact customer service or call us at 1-617-450-2300 .

This message will appear once per week unless you renew or log out.

Session expired

Your session to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. We logged you out.

No subscription

You don’t have a Christian Science Monitor subscription yet.

A Thoughtful and Inclusive Tour of Historic Charleston Plantations

At sprawling plantations in south carolina’s largest city, you’ll discover renowned architecture, award-winning gardens—and a growing awareness of the importance of centering black voices..

- Copy Link copied

Middleton Place

It’s no secret that Charleston and its most beautiful estates have a complicated past. With 40 percent of all the enslaved who were brought to America coming through the Holy City, many ended up at the plantations that are now historic destinations. Traditionally, plantation tours focused on the opulence of the houses and tended to highlight the perspectives of wealthy white inhabitants. Today, this is changing, as nearly all the plantation sites in the Charleston area feature tours of slave quarters, African American history exhibits, and immersive Gullah Geechee culture programs, a distinctive group of African Americans whose ancestors were enslaved in the Lowcountry.

Because of these educational, contemplative experiences, visiting Charleston’s plantations can feel more rewarding and insightful than ever before. Walk in the footsteps of the enslaved and see where they slept, worked, and worshiped. Listen to moving stories and songs from true descendants of the Gullah Geechee people. Visit the headquarters for the Freedmen’s Bureau, an important early Reconstruction agency that worked to secure the freedom of African Americans. Here are some ways you can discover the full history behind Charleston’s plantations, while honoring the people who were enslaved there.

Boone Hall Plantation

Christopher Shane 2014

Experience Gullah Geechee culture with the people who know it best

The only plantation in Charleston to offer a live exploration of Gullah Geechee culture, Boone Hall Plantation helps to preserve these distinctive, meaningful traditions. During the presentation, Gullah Geechee descendants share their history, allowing guests to experience their enlightening and moving storytelling, song, and dance firsthand.

A visit to Boone Hall also provides an in-depth look at the lives of the enslaved and African Americans. Its Black History in America exhibit, staged throughout nine of the estate’s historic dwellings, illustrates different periods from slave ships arriving to the struggle for civil rights up to present day. While touring the sprawling grounds, visitors have an opportunity to witness the living quarters, historic relics, and lifestyle of the enslaved who lived at Boone Hall, in addition to house tours and the stunning Avenue Of Oaks, a three-quarter mile stretch of 270-year-old giant live oaks draped with Spanish moss.

Discover the unabridged truth of an important heritage site

Established in 1851, McLeod Plantation Historic Site is an award-winning Gullah Geechee heritage site, carefully preserved in recognition of generations of enslaved people. Originally a 1,693-acre labor camp, the estate has played many roles, including hospital for the Confederates, burial ground for Union soldiers, and headquarters for the Freedmen’s Bureau. Today, the 37-acre plantation hosts guided interpretive tours that illuminate the lives of the men, women, and children who lived and worked here before and after slavery.

Most of all, McLeod focuses on the African Americans who lived on the property well into the late 20th century. Compare the McLeod family home with those built for enslaved families, explore the meaning of spirituality in the lives of McLeod Plantation’s residents, and trace the emergence of Gullah culture in the Lowcountry.

McLeod Plantation Historic Site

Explore the African American history of three different plantations

Spend your day outside of downtown Charleston visiting these three neighboring plantations that are just down the road from one another. Drayton Hall , built in 1738, is the oldest unrestored plantation house in America still open to the public. With no plumbing, electric lighting, or furnishings in the main house, it allows a rare opportunity to appreciate the original architecture of a late 18th-century home. Visitors to Drayton Hall can view an interactive exhibit on Black history, the largest documented African American cemetery in North America (and the oldest still in use), and a collection of 17th- to 19th-century artifacts that were recovered during excavations, providing insight into the undocumented lives of both the African and Native Americans who were enslaved here.

Nearby, Magnolia Plantation & Gardens , the oldest public garden in America and a popular destination for wildlife enthusiasts, invites guests to embark on a variety of naturalist-guided tours, including a boat excursion on the “Ashley River and the Nature Tram” tour, where you’ll be able to spot alligators, turtles, and birds like blue herons, ibises, and egrets. “From Slavery to Freedom: The Magnolia Cabin Project Tour” instead focuses on the stories of the African American families who were once enslaved here, as well as Black history from the segregation era through today’s modern civil rights. Visitors board an open-air shuttle that transports them to former slave dwellings (four cabins built in the 1850s and a smokehouse from circa 1900) where free men and women who worked to design and maintain the gardens, and served as Magnolia’s first tour guides, also lived after the Civil War.

Finally, see history come alive at Middleton Place , home to some of America’s oldest and most significant landscaped gardens. Craftspeople in the stable yards demonstrate the skills employed by enslaved people, from sewing clothing to making tools in the blacksmith shop. Eliza’s House, a Reconstruction-era African American freedman’s dwelling named for its last resident Eliza Leach, contains a permanent exhibit on slavery that provides a glimpse of the everyday life of the plantation’s enslaved people.

Drayton Hall

Dig deeper into the past

Looking for a little more guidance or simply don’t want to do any driving? Leave it to Gullah Tours , operated by Alphonso Brown, a lecturer on the Gullah language and Black history of Charleston, and Sites & Insights operated by Al Miller, an author and community historian. As the area’s premier tours related to Gullah Culture, you’ll visits a variety of sites like Catfish Row, the Sea Islands, and the historic Battery, adding invaluable insight to topics like Gullah Geechee culture, the Stono Rebellion, and important African American figures.

11 Remarkable Southern Plantation Tours in the US

With their architecture and remarkable gardens, historic Southern plantation homes are full of old-world charm and beauty. But more importantly, they have rich stories to tell because they played significant roles in our nation’s history. Today, it’s hard to believe, but more than 50,000 plantations operated during the antebellum period.

The economy of the 17th- and 18th-century American South was due to an insatiable demand for cotton, indigo, rice, and tobacco. Though most of them folded after the abolition of slavery, many of these magnificent properties on which this economy was built still exist and are rich in history.

Most of the plantations you can visit today are located in the Deep South, including South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. The ones open to visitors tend to be more impressive and often managed by state historical societies or parks programs. If experiencing the storied history and architectural beauty of a southern plantation home is in your future, then these 11 Significant Southern Plantation Tours in America should not be missed!

Oak Alley Plantation, Vacherie, LA

This plantation was first a sugar cane plantation started by Valcour Aime, who purchased the property in 1830. He established an enslaved community that worked the plantation. But in 1836, Jacques Roman bought the Oak Alley property and began to build his own home on the lot.

Accomplished entirely by slave labor, his house was built in Greek Revival style using bricks made on-site and marble shipped in by steamboat. The self-guided tour at Oak Alley centers on the lives and living conditions of those who were owned and kept on this plantation.

While visiting, learn about life after emancipation and stop by the Blacksmith Shop, which pays tribute to Louisiana artisans and the history of forging metalwork. This plantation can be found in the 1993 film, Interview With a Vampire and Beyoncé’s 2006 music video for Deja Vu.

Belle Meade Plantation, Belle Meade, TN

What started as a simple log cabin is now a plantation outside of Nashville that serves as an educational source. Established by John Harding in 1807, “Belle Meade” translates to mean beautiful meadow in old English and French. What started as a 250-acre property would become a 5,300-acre farm that raised thoroughbred horses.

Besides a Greek Revival Mansion, it had a train station and a rock quarry and raised five generations of owners with their enslaved workers. Today the site maintains 34 acres of the original property, including the mansion and original home. It is dedicated to the conservation of Tennessee’s Victorian architecture and equestrian history.

Visitors can enjoy a tour of the property led by trained and costumed guides, who share the mansion’s history and other historic buildings like a carriage house, horse stable, and log cabin. Free wine tasting is offered at the location’s winery after tours, and there is a gift shop and restaurant for visitors.

Shirley Plantation, Charles City, VA

This location remains a working plantation and privately-owned home to this day. This is the country’s first plantation built in 1613, only six years after English settlers founded Jamestown. The “Great House” was styled initially in Anglo-Dutch architecture through continuous efforts and additions with mixed styles, creating a charismatic aesthetic.

The Hill family has been living on the property for 11 generations, keeping the estate in beautiful, restored condition. You can learn about the amazing women who kept the farm operating during the Civil War and saved it from falling by caring for wounded Union soldiers.

Tours highlight the history of the plantation, including the role of religion in colonial America, colonial education, the history of the Hill family, and the effects of the Civil War and Civil Rights against the plantation. A new slavery exhibit has also been built in the original 18th-century outbuilding.

Nottoway Plantation, White Castle, LA

This is the south’s biggest antebellum mansion. Located northwest of New Orleans and southwest of Baton Rouge, Nottoway is a Greek and Italian-style mansion full of luxurious features and details. Over the years, Nottoway Plantation went through several different owners and years of decline but managed to survive the Civil War.

It was completed in 1859 by prestigious sugar planter John Hampton Randolph. As a wealthy businessman, he wanted no expense spared when it came to the home’s design. The 53,000sqft mansion has 64 rooms with 22 massive exterior columns, 12 hand-carved Italian marble fireplaces, 15ft ceilings, and a lavish pure white oval ballroom. He also installed modern bathrooms with running water and gas lighting throughout the home.

He wanted a home that would be seen by river boaters on the Mississippi River or riders on a horse-drawn carriage traveling on Great River Road. When you visit today, costumed tour guides take you through the mansion, sharing details of the property’s history.

Sherwood Forest, Charles City, VA

This location is unique because it’s the only private home to be owned by two presidents. William Henry Harrison purchased the house under the name “Walnut Grove.” After his death, his successor John Tyler purchased the plantation in 1842, renaming it Sherwood Forest to show his outlaw position in the Whig party. He lived in the house from the time he left the office until he died in 1862.

The Tyler family has continued living here since then, keeping the house in excellent condition. The property is open for tours daily between 9 am and 5 pm. Only 30 minutes from Williamsburg, Sherwood Forest is a Greek Revivalist wonder with 25 acres of gardens, woodlands, and outbuildings both original and reconstructed.

Visit the gardens once used by Civil War troops and even learn about the ghost, the “Gray Lady,” who has allegedly haunted the Gray Room for the past 200 years, rocking back and forth in her rocking chair.

Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, GA

Melville Hanna, who obtained the property in 1896, gave the estate to his daughter, Kate, in 1901, and she immediately began construction on Pebble Hill, being actively involved in its design process. She first built a log cabin that served as a school and a playroom for her children.

She then continued with neo-classical brick structures like the Plantation Store, the Waldorf, the Pump House, and the Stables Complex. Kate being a humanitarian, provided many benefits to the 40 employees who worked on the plantation. The Visiting Nurse Association offered medical services for employees and their families, and two schools were built and maintained for employees’ children.

After Kate died in 1936, her daughter Elisabeth inherited the plantation and turned it into a museum. Finally, in 1956 the Pebble Hill Foundation made the property open to the public, and they maintain and manage the estate today.

Whitney Plantation, Edgard, LA

This historical complex, which includes 12 structures, was initially called the Habitation Haydel. The Spanish Creole-style main dwelling and its surrounding buildings were built by slaves under the owner, German immigrant Ambrose Heidel, in 1752.

This plantation stands as a memorial to the slaves sacrificed on the property and others like it. The Field of Angels especially is a section of the slave memorial site, dedicated to 2,200 Louisiana slave children who died before they were three. Ultimately, thirty-nine children died at Whitney between 1823-1863, only six of which made it to five years old.

Also dedicated to the slaves of Whitney, you’ll find the Slave Quarters site. You won’t find the original buildings here because the previous owners advocated for their removal in an attempt to raise property values. The ones that stand were moved from other plantations, supporting the authenticity and educational value of the site.

Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, Hermitage, TN

The President and his wife lived here for years, living off profits made from the crops that slaves worked daily. When he initially bought The Hermitage in 1804, Jackson owned nine African American slaves, and by the time he passed away in 1845, he owned 150 slaves who lived and worked on the property.

Tours here cover over 1,000 acres of farmland that used to be The Hermitage Plantation. It was a self-sustaining property, relying on slave labor to produce cotton. Although slaves could not legally wed, Jackson encouraged them to form family units to discourage slaves from escaping since it would be more difficult for an entire family to flee safely.

Take a tour of the Hermitage and walk through the mansion and its grounds, where President Jackson and his wife are buried. Costumed tour guides share a detailed history of the Jackson family, the plantation, its buildings, and original belongings that have survived on the property.

Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, Charleston, SC

In 1676, Thomas Drayton, with his wife Ann, the first in the Magnolia family line that lasted for more than 300 years, established the Magnolia Plantation along the Ashley River. During the Colonial era, the plantation saw immense growth due to the cultivation of rice.

But once the American Revolution began, troops occupied the land, and Drayton and his sons became soldiers fighting the British. The American Civil War threatened the welfare of the Drayton family, the house, and the gardens, but the plantation recovered and saw additional growth of the gardens, which became the focus.

The property was saved from ruin by opening to the public and now offers guided tours taking visitors through the Drayton family home and gives a glimpse of what plantation life was like in the 19th century. This includes ten rooms that are open to the public, furnished with antiques, quilts, and Drayton family heirlooms.

Destrehan Plantation, Destrehan, LA

This Plantation in Louisiana was built in 1787 and is located 25 miles away from downtown New Orleans. It was home to successful sugar producers Marie Celeste Robin de Logny and Jean Noel Destrehan. By 1804, fifty-nine enslaved workers lived on the property, producing over 203,000 pounds of sugar.

This plantation is where one of the three trials after the 1811 Slave Revolt took place. Led by Charles Deslondes, it was one of the most significant slave revolts in US history. Visitors can tour the restored plantation, encircled by lush greenery, that looks over the Mississippi River.

Stories of the Destrehan family and those enslaved are shared through guided tours, which also feature historical exhibits and opportunities to participate in period demonstrations. Tours also include access to the Jefferson Room, displaying an authentic document signed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

James Madison’s Montpelier, Montpelier Station, VA

Ambrose Madison, a slaveholder in Virginia, and his wife Frances and children arrived in 1732 at a plantation they named Mount Pleasant. James, the grandson of Ambrose, spent his early childhood here while construction on a brick Georgian house began that would later become the center of James Madison’s Montpelier.

This is the land where James Madison thought up ideas and shaped the US as the country’s 4th president. With 2,650 acres of rolling hills, horse pastures, and scenic views of the Blue Ridge Mountains, Montpelier offers insight into the Madison family history and provides a deeper look into Madison’s presidency. Exhibits on the grounds include the 1910 Train Depot, exploring the African American struggle for civil rights.

There’s also The Mere Distinction of Colour, allowing visitors to hear the stories of enslaved people at Montpelier, as told by their descendants. It recounts the events at Madison’s home and the South Yard of the land, where slaves lived and worked. The exhibition even explores how the legacy of slavery impacts race and human rights in modern America.

Speaking of tours in the US… There are plenty of them and we have some awesome estate tours to show!

Ricarda is our very definition of a wanderer. Hailing from Chicago, Illinois, she’s on a race to see and experience as much of the world as possible. She packed up her life one day and has been traveling by RV ever since, scouring the states to discover the many stunning views the US has to offer! Lucky for us, she’s also one of our senior writers so we get access to a lot of worth-telling insights about her amazing adventures.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Follow us on:

Most popular, 9 surprising things not allowed on a plane 11 january 2023, 11 charming small towns to retire in america 30 may 2022, 13 remarkable train tours for railway fanatics 19 october 2021, 8 disgusting things hotels are still doing to save money 22 june 2022, related posts.

7 Quirky Spots for an Epic New Year’s Eve

Do you want to have a New Year’s Eve that will be different and special? Say no

Stunning Destinations: 6 Budget-Friendly Spring Travel Ideas in the US

Looking for some budget-friendly spring travel ideas? USA Wanderers has got you covered! As the winter blues

10 Hidden Gems Among UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Are you looking for more traveling destinations? Check out these must-see UNESCO World Heritage sites: Hello folks!

10 Beach Towns in the US That Are Shockingly Inexpensive

Which are the most affordable beach towns in the US? Life on a beach is alluring—long, relaxing

5 Incredible Budget-Friendly Winter Destinations If You Miss the Snow

As some would say, winter is coming, and we believe that in case you miss the snow,

7 Exquisite Must-Try Dishes on a Culinary Road Trip Across America

USA Wanderers presents: must-try dishes on a culinary road trip across America! I’m a foodie, and I

10 US National Park Road Trips With Breathtaking Stops

What are some of the best national park road trips in the US? The national parks of

12 for ’24: 2024’s BEST Monthly Travel Ideas (Part 2)

Welcome back to the best destinations for this year! You didn’t think we would forget the second

Do not sell my personal information | Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Contact | Subscribe | UnSubscribe | BECOME A WANDERER | OUR NEWSLETTERS

Made with ❤ by Inedit Agency

CA Privacy Policy | Request to Know | Request to Delete

HISTORY & LEGACIES

Whitney plantation, the plantation every american should visit, -national geographic.

THE WHITNEY INSTITUTE EDUCATES THE PUBLIC ABOUT THE HISTORY AND LEGACIES OF SLAVERY IN THE UNITED STATES

Whitney Plantation (legal name The Whitney Institute) is a non-profit museum dedicated to the history of the Whitney Plantation, which operated from 1752-1975 and produced indigo, sugar, and rice as its principal cash crops. The museum preserves over a dozen historical structures, many of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Whitney Plantation Historic District.

COME EXPERIENCE

Visit the museum.

HOURS & TICKETS

LOCATION & DIRECTIONS

VISITOR GUIDELINES

PHOTO & VIDEO POLICY

Your support matters, in these uncertain times, our mission continues., @follow us on instagram, whitney plantation on social media, events & seminars, whitney plantation events, temporary exhibit on view march through november 2024, extractivism.

The Magic of the Drums: Ancestral Remembrance

KEEP UP TO DATE WITH WHITNEY PLANTATION

- PLAN YOUR VISIT

CALL US TODAY

(225) 265-3300

5099 LOUISIANA HWY 18 EDGARD, LA 70049

Notable Southern Plantation Tours in the United States

History buffs with an interest in the southern part of the United States will enjoy these plantation tours. They offer insight into the history of slave labor, plantation living and how the south evolved into what it is today.

Did you know you can now travel with Culture Trip? Book now and join one of our premium small-group tours to discover the world like never before.

Oak Alley Plantation

Located in Louisiana, Oak Alley Plantation was first a sugar cane plantation started by Valcour Aime, who purchased the property in 1830. He established an enslaved community who worked the plantation. Then in 1836, Jacques Roman acquired the Oak Alley property and began to build his own home on the plantation. Accomplished entirely by slave labor, his home was built in Greek Revival style using bricks made on site and marble shipped in by steamboat to construct the dining-room floor. The self-guided exhibit at Oak Alley focuses on the lives and living conditions of those who were owned and kept on the plantation. Visitors learn about life after emancipation and can stop by the Blacksmith Shop, which acts as a tribute to Louisiana craftsmen and the history of forging metalwork.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to 500$ on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

Belle Meade Plantation

What started as a single log cabin is now a plantation located outside of Nashville, Tennessee that serves as an educational resource. Founded by John Harding in 1807, “Belle Meade” translates to mean beautiful meadow in old English and French . It began as a 250-acre property that eventually became a 5,400 thoroughbred horse farm. It had a Greek Revival Mansion, a train station and a rock quarry that supported five generations of owners and their enslaved workers. Today the site retains 34 acres of the original property, including the mansion and original homestead. It is dedicated to the preservation of Tennessee’s Victorian architecture and equestrian history.

Visitors to Belle Meade Plantation enjoy a tour of the property led by trained and costumed guides, who share the history of the mansion, as well as many other historic buildings like a horse stable, carriage house and log cabin. Free wine tasting is offered at the site’s winery after tours, and there is a gift shop and restaurant for visitors as well.

Nottoway Plantation

The south’s largest antebellum mansion is Nottoway Plantation. Located in Louisiana northwest of New Orleans and southwest of Baton Rouge, Nottoway is a Greek and Italianate style mansion full of extravagant features and details. It was completed in 1859 and the construction was commissioned by prestigious sugar planter John Hampton Randolph. The mansion became home to John, his wife Emily Jane, and their 11 children. As a wealthy businessman, John wanted no expense spared when it came to the home’s design. The 53,000 square foot mansion has 64 rooms with features like 22 massive exterior columns, 12 hand carved Italian marble fireplaces, 15 1/2 foot ceilings and a lavish pure white oval ballroom. Modern bathrooms with running water and a gas plant that provided gas lighting throughout the home were also installed per John’s vision.

John’s wish was for the mansion to be a place where he could entertain visitors in extravagant and elegant style. He wanted a home that would be admired by all, seen by river boaters on the Mississippi River or riders on a horse drawn carriage traveling on Great River Road. When you visit Nottoway Plantation today, costumed plantation tour guides take you through the mansion, sharing details of the property’s construction and history. Over the years, Nottoway Plantation went through several different owners and years of decline, but managed to survive the Civil War. This is a testament to the loving care that the mansion has received by those who are determined to keep its history alive.

Pebble Hill Plantation

The original owner of Pebble Hill Plantation in Georgia was Melville Hanna, who acquired the property in 1896. In 1901, he gave the property to his daughter, Kate. She immediately began construction on Pebble Hill, hiring architect Abram Garfield, and was actively involved in the design process. The first building was a log cabin that served as both a school and a playroom for her children. Several of the buildings were neo-classical brick structures that include the Plantation Store, the Pump House, the Waldorf and the Stables Complex.

Kate was a humanitarian who provided many benefits to the employees who worked on the plantation. Over 40 families of employees lived in furnished cottages, the Visiting Nurse Association provided medical services for employees and their families, and two schools were built and maintained for employees’ children in grades 1-7.

After Kate’s death in 1936, her daughter Elisabeth “Pansy” inherited the plantation. She wanted it to become a museum, and in 1956 formed the Pebble Hill Foundation to make the property open to the public. After her death in 1978, the plantation became property of the Pebble Hill Foundation, which maintains and manages the estate today.

Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage

Located about 10 miles east of downtown Nashville, Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage offers self-guided audio tours and interpreter led tours of the former president’s estate. General admission plantation tours cover over 1,000 acres of farmland that used to be The Hermitage Plantation. The Hermitage was a self-sustaining property that relied on slave labor to produce cotton. President Andrew Jackson and his wife Rachel lived there for several years in the late 1700s. The Jackson family survived on profits made from the crops that the slaves worked every day. When he first bought The Hermitage in 1804, he owned nine African American slaves. At the time of his death in 1845, he owned about 150 slaves who lived and worked on the property.

Although slaves could not legally marry, Jackson encouraged his to form family units. This was a way to discourage slaves from trying to escape, since it would be more difficult for an entire family to safely flee.

Take a plantation tour of the Hermitage to walk through the mansion, the exhibit gallery and the grounds, where both President Jackson and his wife are laid to rest. Costumed tour guides will share the detailed history of the Jackson family, the plantation and the buildings and original belongings that remain on the property.

Magnolia Plantation and Gardens

Back in 1676, Thomas Drayton and his wife Ann established the Magnolia Plantation along the Ashley River in South Carolina . The couple were the first in a line of Magnolia family ownership that has lasted for more than 300 years. During the Colonial era, the plantation saw immense growth due to the cultivation of rice. Once the American Revolution began, troops occupied the land and Drayton, along with his sons, became soldiers fighting the British. In 1825, Thomas Drayton’s great grandson willed the estate to his daughter’s sons, since he had no male heirs to leave the property to. One of the sons died of a gunshot wound, leaving the second brother a wealthy plantation owner at the age of 22. The American Civil War threatened the welfare of the Drayton family, the house and the gardens on the plantation. But the plantation recovered and saw additional growth of the gardens, which became the focus. The property was saved from ruin when it opened to the public in 1870. The plantation offers half-hour long guided tours taking visitors through the Drayton family home – the third in more than three centuries – and gives a glimpse of what plantation life was like in the 19th century onward. There are 10 rooms open to the public, furnished with antiques, quilts and Drayton family heirlooms. More than five years ago, Magnolia’s Cabin Project started as an effort to preserve five structures on the property that date back to 1850. The structures are former slave dwellings that are now the focal point for a 45-minute program in African American history .

Destrehan Plantation

The Destrehan Plantation in Louisiana was established in 1787. It is located 25 miles from downtown New Orleans. It was the home of successful sugar producers Marie Celeste Robin de Logny and her husband, Jean Noel Destrehan. By 1804, 59 enslaved workers inhabited the property, producing over 203,ooo pounds of sugar. The Destrehan Plantation was the site where one of the three trials following the 1811 Slave Revolt took place. It was led by Charles Deslondes, and was one of the largest slave revolts in U.S. history.

Visitors can tour the restored plantation, which is surrounded by lush greenery and looks over the Mississippi River. Stories of the Destrehan family and those who were enslaved are shared through guided tours, which also feature historic exhibits and the opportunity to participate in period demonstrations. Plantation tours also include access to the Jefferson Room, which displays an authentic document signed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

San Francisco Plantation House

Considered the most opulent plantation house in North America, the San Francisco Plantation House is located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, about 40 minutes outside of New Orleans. In the early 1800s, Elisee Rillieux sold the land that later became the San Francisco Plantation House to Edmond Bozonier Marmillion and Eugene Lartigue, profiting $50,000. Edmond was in debt, despite being a successful crops planter. His financial problems stayed with him for the 26 years he owned the property. He continued to acquire slaves and purchase land, but didn’t make investments in sugar machinery.

The plantation was prosperous for a while in the mid-1800s, but in 1853, Edmond hired expert builders and skilled slaves to convert the plantation into a prestigious residence for his sons. Valsin and Charles were the only two of Edmond’s and his wife Antoinette’s eight children who didn’t die from tuberculosis, the same disease that killed Antoinette in 1834. The main construction on the house was completed two years later and Edmond then hired artists to create hand painted ceilings, painted door panels, faux marbling and faux wood graining throughout the home.

When Edmond passed away in 1856, his son Valsin took over the plantation. In 1859, he tried to sell the estate, but wasn’t able to due to a legal conflict involving his sister-in-law, Zoe Luminais. When the conflict was resolved in 1861, war and reconstruction prevented the possibility of sale for 15 years. Valsin died in 1871, and in 1879, Achille D. Bougere purchased the property for $50,000.

Guided plantation tours are conducted by professional costumed guides who take visitors through the colorful plantation, exploring a slave cabin, a one room school house, and the property, which was restored in both 1970 and 2014. Blacksmithing and demonstrations also take place on the property, where you’ll find a gift store as well.

James Madison’s Montpelier

Ambrose Madison, a planter and slaveholder in Virginia, along with his wife Frances and their three children, arrived in 1732 to a plantation they called Mount Pleasant. One of Ambrose’s grandchildren, James, spent his early childhood at Mount Pleasant while construction began on a brick Georgian house that would later become the center of James Madison’s Montpelier .

It was on this very land that James Madison contemplated ideas and shaped the United States as the country’s fourth president. With 2,650 acres of horse pastures, rolling hills and scenic views of the Blue Ridge Mountains, James Madison’s Montpelier offers insight into the Madison family history, and provides a deeper look into James Madison’s presidency . Just behind Mount Pleasant is the Madison Family Cemetery, where both James and Dolley Madison are buried.

Exhibits on the property include the 1910 Train Depot, which explores the African American struggle for civil rights . It opened in 2010 and is a permanent exhibit on the plantation. There’s also The Mere Distinction of Colour, which allows visitors to hear the stories of those who were enslaved at Montpelier, as told by their descendants. It recounts the events that took place at the Madison’s home, as well as the South Yard of the property, where the slaves lived and worked. The exhibition also explores how the legacy of slavery impacts race relations and human rights in modern America.

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

See & Do

Gift the joy of travel this christmas with culture trip gift cards.

Guides & Tips

The benefits of booking a private tour with culture trip.

Everything You Need to Know About Booking a Private Culture Trip

How to Book a Private Tour with Culture Trip

How to Make the Most of Your Holiday Time if You're in the US

Travel With Culture Trip: Who Are Our Local Insiders?

The Best Solo Travel Tours in the US

5 Ski Resort Scenes You Can't Miss This Year

Travel in America: Top 5 Trip Ideas

The Best Couples Retreats in the USA

Top TRIPS by Culture Trip for Ticking Off Your Bucket List

Top Trips for Embracing Your Own Backyard

Winter sale offers on our trips, incredible savings.

- Post ID: 1425513

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

- Buy Tickets

Slavery at Monticello Tour

Open Today – 8:30AM - 5:30PM

These guided outdoor walking tours focus on the experiences of the enslaved people who lived and labored on the Monticello plantation. Included in the price of admission.

Reservations for this tour are not required. Tours begin on Mulberry Row near the Hemmings Cabin (view a map of Monticello for visitors ).

Explore Before You Visit

Download our free Slavery at Monticello app

Thomas Jefferson and Slavery

People Enslaved at Monticello

Slavery FAQS

Videos related to slavery at monticello.

"Picturing Mulberry Row" - a look at slavery at Monticello through this critical component of the greater plantation

"Some visitors think we're trying to knock Jefferson off his pedestal" - A Guide's Perspective