- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

The new age of the airship: Could blimps be the future of air travel?

Sleek, green and coming to the skies above you.

What if you could fly with a fraction of the carbon emissions of a conventional aeroplane? What if you could cruise through the clouds with almost zero noise? And, what if you could board your aircraft without first having to navigate a sprawling airport and all its associated infrastructure?

That’s the elevator pitch for a new generation of airships, the retro-futuristic, blimp-style vehicles that might just revolutionise air travel in the coming decade. Dotted around the world, companies from small start-ups to aerospace giant Lockheed Martin are building lighter-than-air, modern-day Zeppelins with a broad range of applications in mind.

One British company, Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV), recently laid out plans for a series of short-haul flights that would enable city-hopping trips aboard its Airlander 10 craft. Proposed routes include Liverpool to Belfast, Oslo to Stockholm and Barcelona to Palma. And per passenger, HAV claims the carbon footprint of such a flight would be less than a tenth of the same journey in a conventional jet plane, because helium is used as a lifting gas to get the craft airborne.

"Three quarters of the carbon reduction almost comes for free," says Mike Durham, HAV’s chief technical officer. "It’s helium keeping us up so we only need fuel [from four combustion engines] to push us along. Conventional aeroplanes need to burn fuel to stay up as well."

Of course, without a jet engine, airships are considerably slower than modern planes. HAV says its proposed Liverpool-to-Belfast route would take 5 hours and 20 minutes (although a similar journey by ferry would take more than nine hours).

As the world slows down in response to COVID-19 and as we grapple with how to reduce carbon emissions from air travel and freight, airships may offer viable alternatives – and not just in passenger flights.Hybrid airships are touted for aid drops, search and rescue, eye-in-the-sky command centres and tourism. Imagine a bird's eye tour of the North Pole or Great Barrier Reef. Some believe luxury airships could even become playthings of the super-rich, decadent floating mansions that offer the same status as a luxury yacht.

The most practical application, however, lies in freight.

"I’ve long believed that hybrid airships would be best placed to disrupt global shipping given their volumetric capacity, the increasing desire for rapid delivery of goods from overseas, and the fact that their speed and operating cost would enable faster delivery than by ship with a proportionally lower increase in transportation cost," says John-Paul Clarke , professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Texas at Austin.

International shipping doesn't have to be fast, so transporting food or chemicals by airship could save significant carbon emissions compared to large freight vessels at sea. Yet for all their green credentials, some argue that helium-powered airships are not the future of green transport .

"The main source of helium production is oil and gas extraction," says Julian Hunt , a researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria. "If the main driver for a future airship industry is to reduce aviation CO 2 emissions, a helium-based airship industry will have to rely on a functioning oil and gas industry. It does not make sense."

Hunt has proposed using the jet stream to propel airships at far greater altitudes than something like the Airlander plans to fly.

But if helium – which is also a non-renewable resource – isn’t the answer, then it raises two alternative H-words, both with rather negative connotations: hydrogen and Hindenburg. In 1937, the most infamous airship that ever flew exploded midair and crashed in front of photographers and filmmakers, killing 36 people. Powered by (flammable) hydrogen, the crash was a PR disaster that contributed to the demise of airships as a popular mode of transport.

That was over 80 years ago, however. Most in the industry believe hydrogen's comeback is inevitable.

"Hydrogen is the obvious alternative to helium," says Clarke. "It can be produced greenly and more and more cheaply with each passing day. It has an unfortunate reputation due to past accidents [but] we have learned a lot over the years about how to handle hydrogen, especially in transportation settings, and it is now being used to propel cars, trucks, and aircraft."

So what's it like to fly in an airship? According to Durham, a trip on HAV's Airlander would be a lot smoother than modern flight.

"It’s a low-noise, low-vibration, low-turbulence cabin space where in many operations you may even be able to open a window. It’s also got floor to ceiling windows, so the ambient light is different as well. The cabin has a lot more volume per passenger."

Clarke and Hunt both doubt that airships offer a viable alternative to short-haul flights, citing issues like wind variability and logistical issues, but Durham remains optimistic.

"There will be sweet spots that work for our product and there will be spaces that won’t work. It’s probably not going to work for long-haul flights," he says.

"I think they have a place to play in society moving forward. The human race is going to have to come to terms with the fact that we cannot spend our time rushing and tearing about the place, ignoring the planet. Lighter-than-air travel has a part to play to support that drive to become greener."

Airship designs ready for takeoff

Lockheed martin.

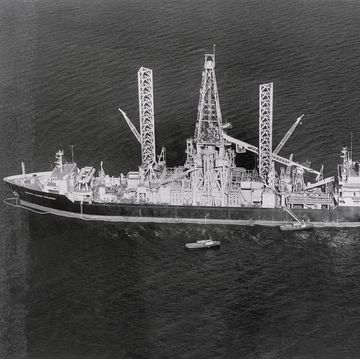

Skunk Works is an arm of the aerospace giant whose purpose is to develop new kinds of aircraft. The department has developed a demonstrator airship that it believes is ready for commercial deployment delivering aid in disaster zones or minerals from remote mining sites. It has also developed a robot that crawls across the exterior of the blimp seeking and repairing tiny holes.

Flying Whales

This French manufacturer is developing an airship designed for freight that picks up and drops off its payload without actually landing. Using helium to hover above the ground, it will have winches that lift or lower its payload, saving energy. The vehicle is designed to carry up to 66 tons.

This Israeli start-up is hoping to join a growing airship market with three different designs. Primarily built for transporting freight, the ships have cargo bays built into the airship and, unlike a lot of current designs, would be powered by hydrogen fuel cells, supplemented by diesel.

Read more about the future of flight:

- Airbus reveals zero-carbon hydrogen plane concepts

- Concept planes that could one day take to the sky

- The world's first airport for flying taxis

Share this article

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

What if your aircraft could be

Lighter than air.

The Electric Airship Revolution Is Almost Here. Are We Ready?

Companies around the world, including one backed by Google co-founder Sergey Brin, are hoping to resurrect the airship as a green energy, cargo-hauling alternative, but a few obstacles still remain.

The first age of airships ended in flames—the next one begins with an entire world on fire.

Some changes are obvious. Replace internal combustion engines with EVs . Duh. Retire CO2-spewing power plants and invest in wind, solar, and nuclear . No brainer. But there’s a big elephant in the room—one that comes with two turboprop engines, not enough legroom, and an insatiable hunger for jet fuel.

Jet airliners are notorious for spewing carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, sulfur oxides, and nitrogen oxides—basically all the bad oxides. Although valiant efforts to develop sustainable jet fuels or even fully electrified alternatives have produced some promising results , airplanes simply require too much energy to sustainably keep 100,000 pounds of metal aloft.

But what if your aircraft could be lighter than air?

“The First World War is what gave planes their first boost, and the Second World War pushed them to jet engines… but the new war is the war against carbon emissions,” Barry Prentice, director of the Transport Institute at the University of Manitoba and co-founder of Buoyant Aircraft Systems International (BASI), tells Popular Mechanics . “Climate change… is changing how we look at technology and also the airship itself.”

Resurrected from the graveyard of aviation, airships have become the engineering obsession of companies around the world. In California, LTA Research , backed by Google co-founder Sergey Brin, is preparing for test flights of its Pathfinder 1 rigid airship. The France- and Canada-based company Flying Whales, which received hundreds of millions of dollars in funding (including some from the French government), is currently testing its 650-foot-long LCA60T dirigible . And after a decade of development, Hybrid Air Vehicle in the U.K. is readying production of its Airlander 10 blimp .

Lots of people (with lots of money) say there’s a future in airships, but what does that look like exactly?

Old Name, New Tech

Airships are some of the oldest aircraft in human history. In the 18th century, they carried the Montgolfier brothers over the palace of Versailles, and nearly a century later, the U.S. military established its first ever aviation unit during the Civil War called the balloon corps .

Because of this long lineage, airships sometimes feel like technology frozen in the past. But comparing today’s electric airships to the grand Zeppelins of the interwar years is kind of like saying a Douglas DC-3 is just like an Airbus A320. Sure, they’re both planes, but that’s basically where the similarities end.

“The big old airships had cow intestines pasted on linen sheets to create the gas bags,” Prentice says. “Today no one is going to fly in an airship that hasn’t flown in a computer first. The tools have gotten a lot better and so have the materials—you’re not going to use cow intestines anymore.” Instead, you’re going to use advanced materials to maximize every ounce of lift generated by an airship’s helium (or hydrogen) gas bags.

Arguably the Rolls-Royce of this new generation of airships is LTA Research’s Pathfinder 1. Founded in 2015 and backed by Google co-founder Sergey Brin, the company has been tight-lipped about its airship efforts, but in May 2023, Bloomberg finally got a peek under the hood . Dotting the Pathfinder 1’s spec sheet are words like “Kevlar,” “carbon fiber,” “ripstop nylon,” and “hydrogen fuel cells”—all technologies completely unimaginable to airship engineers a century ago.

In other words, this ain’t your granddaddy’s airship.

➥ Anatomy of a Modern Airship

“Just one example of the novel engineering found in Pathfinder 1 is a tool using lidar , which measures helium volume in gas cells in real time. It’s an airship tool that never existed before and an LTA invention that increases the safety of our next-generation airships,” LTA Research CEO Alan Weston told Popular Mechanics in an email. “LTA intends to increase the capabilities of Pathfinder airships, with the possibility of solar or hydrogen fuel cells to power our electric propulsion system.”

LTA Research sees the role of its airship as more of a cargo hauler and less of a people mover. While airships can deliver tonnage more sustainably than air cargo (which is often performed by the oldest, and therefore least efficient, planes), airships will likely never beat airplanes in terms of pure speed.

“The jet engine is a fabulous invention and I certainly don’t want to give them up,” Prentice says, “But there’s not justification for a cargo jet because freight doesn’t complain… I think people will look back and, if anything, they’re going to pick out and say ‘what the hell were they thinking,’ it’s going to be cargo jets.”

But even in a supporting cargo role, airships can take a huge bite out of global carbon emissions while also reaching parts of the world that airplanes and helicopters simply can’t reach or supply efficiently.

With the urgency of climate change adding fuel to the fire, Prentice thinks the single largest market for airships is to ferry goods across oceans . But one question remains: can they even make the journey?

Picturing the Solar-Powered Dream

Christoph Pflaum is not an airship engineer. Instead, he lives in a world of simulations. An expert in leveraging numerical computations to answer complex problems, Pflaum is a mathematician at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg who figures out the nitty-gritty realities of how things work, including optical simulations of thin-film solar cells.

“I became interested in how we use solar cells… but there was one area where we have difficulty using only renewable energy and that’s transport of goods over the Atlantic,” Pflaum told Popular Mechanics .“Then I saw the airship from Zeppelin NT… and I thought ‘okay, this is the place where we need to put thin-film solar cells.’”

Using his expertise in simulation analysis, Pflaum and his team calculated all the nuances of weather, solar availability, and materials to figure out the optimal route solar airships should take across the Atlantic and if they can hang tough with their gas-guzzling competition. The results of his work were published in the International Journal of Sustainable Energy this past March.

And the answer? Hell yeah they can.

“To find the optimal route is really a hard problem from a computer science point of view because there are so many directions you can go,” Pflaum says. So his team designed digital “towns” and “streets” across the Atlantic by creating a grid system for their theoretical solar airship to travel through between London and New York . The team then created “highways” across the ocean using wind data and solar availability to further influence the airship’s journey.

Pflaum’s simulations created routes that snaked into the North Atlantic in the summer and plummeted toward the equator in the winter—all in search of the optimum amount of solar energy during transit. The final results showed that solar airships, designed with a rigid construction to withstand winds, could drastically reduce the emissions of cargo transport to as little as one percent compared to a conventional airliner.

“Solar airships are undeniably environmentally friendly since they are outfitted with exceptionally light and immensely efficient thin-film solar cells that recharge continuously throughout the flight,” Plaum said in a press release back in March . “Consequently, no combustion-related discharges are produced during the airship’s operation.”

Pflaum’s vision of this solar-powered airship future is still a ways off. Both LTA Research and Hybrid Air Vehicles, for example, are initially using diesel to power their electric engines but plan to transition to renewables as the technology develops.

But for that future to ever reach fruition, airships need to first overcome their absolute biggest challenge: public perception.

A Bad Case of “Hindenburg Syndrome”

The word “airship” likely conjures up grainy black-and-white footage of military blimps soaring in the air—or perilously crashing into the ground. The fiery destruction of the German-made Zeppelin LZ 129 Hindenburg on May 6, 1937 essentially closed the curtain on the first generation of airships, and it’s a bad bit of PR that’s been particularly difficult to shake.

“We call it ‘Hindenburg Syndrome,’” Gennadiy Verba, president of the Israel-based Atlas LTA airship company, told Popular Mechanics . Verba previously worked on Google’s Project Loon , which sought to bring internet to remote areas using stratospheric balloons. “Nobody can overcome this psychological problem to use hydrogen again, but we have several methods to make hydrogen much safer.”

Airships like Pathfinder 1 and LCA60T use helium as a lifting gas, but helium is extremely hard to come by and is essential for various scientific experiments and medical equipment like MRI machines . Not only is hydrogen much easier to source , it’s lighter and also a more efficient lifting gas. But the U.S. Congress banned the use of hydrogen in military aircraft in 1922 , and that law remains on the books. Experts like Prentice think the century-old ban needs a rethink.

“In 1930, there was no way to detect [hydrogen]—it was a tasteless, odorless, invisible gas,” Prentice says, noting that today you can buy handheld detectors on Amazon that are capable of sensing hydrogen in parts per million. “Hydrogen will not burn at anything less than four parts per hundred, so long before you get to any risk of a fire with hydrogen, you can ventilate the area… Hydrogen is much harder to burn than people think.”

There are signs that things are changing. In 2022, the European Aviation Safety Agency updated regulations allowing for any lifting gas, stipulating that “adequate measures must be taken in design and operation to ensure the safety of the occupants and people on the ground in all envisaged ground and flight conditions including emergency conditions.”

If the FAA follows suit, then a new age of airships could really take off.

➥ Meet the New Generation of Airships

Pathfinder 1

LTA Research — Backed by Google co-founder Sergey Brin, Pathfinder 1 stretches some 400 feet and features a suite of next-gen technologies including lidar, Tedlar (an advanced polymer material), carbon fiber, and electric propulsion. The home of this gargantuan airship is Moffett Field in California, originally built for the U.S. Navy’s LTA (lighter-than-air) program in the 1930s. The company’s next airship, Pathfinder 3, will scale up to 600 feet long and will be built in Akron, Ohio, where Goodyear constructed U.S. Navy rigid airships a century ago.

Zeppelin NT

Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik — Zeppelin NT—which stands for “new technology” in German—is a 246-foot-long airship with a semi-rigid structure, meaning it contains a skeleton but also relies on internal pressure to maintain its shape. Goodyear blimps, for example, are actually Zeppelin NT airships in disguise. Unlike the other airships in this list, Zeppelin NTs have been dotting the skies for decades, and by leveraging new tech like aluminum and carbon-fiber construction, the Zeppelin NT has kept the airship flame alive in recent years.

Flying Whales — The largest airship on this list belongs to the French and Canadian aeronautics startup Flying Whales. At over 650 feet long, the LCA60T uses 1-megawatt Honeywell generators—the most powerful generators the company makes—to power its hybrid electric airship with sustainable aviation fuel. Some 14 gas cells filled with helium provide the airship’s lift, and the company plans for its first test flights in 2025.

Airlander 10

Hybrid Air Vehicles — Until the arrival of Pathfinder 1 in recent years, Hybrid Air Vehicles’ Airlander 10 has been the vanguard for this new era of airships. The only true non-rigid airship on this list, the Airlander 10 first took flight in 2012 and earned the nickname “the flying bum” due to its overall shape. The airship currently uses four diesel combustion engines, but still delivers a 75 percent reduction in carbon emissions compared to a typical airliner; the company also plans to create zero-emission ships in the future. In February 2023, the company announced that the Airlander 10 was finally ready for commercial production.

H2 Clipper Inc. — A relative newcomer to the airship game, the H2 Clipper is the only airship on this list that plans to use hydrogen, instead of the more scarce helium, as a lifting gas. That’s because the H2 Clipper will be a green hydrogen delivery service when its first prototype is built in 2025. The company, H2 Clipper Inc., is designing its airship to run exclusively on clean energy and will have a cargo area equivalent to 35 shipping containers.

Flying High or Run Aground?

Although using hydrogen would help, today’s airships need something to become the iPhone of the industry—a shining example of success that shows the world the technology’s promise. While there are a few lighter-than-air contenders, all eyes are on LTA Research’s Pathfinder 1, which will begin test flights this year.

“We’re wishing big success to anyone who will be the first,” Verba says. “Not if they succeed, but when they succeed, it’ll be a very good day for all of us.”

A few obstacles still stand in the way of that “very good day” becoming a reality—both technological and political. Proving hydrogen’s reliability and continuing to develop green technology such as thin-film solar cells as well as lithium-ion , battery-powered propulsion are big ones, but also perfecting the art of handling these massive airships on the ground is another herculean engineering effort. Where a heavy airplane simply sits idle at an airport terminal, airships are subject to changes in wind speed, direction, and pressure, and require more sophisticated ground-handling techniques—and that’s not even considering the fact that their hulking bodies require lots of space for building and maintaining them.

To address these issues, Prentice’s company, Buoyant Aircraft Systems International, has developed a turntable-style landing system that allows airships to move with the wind and also land in areas with little infrastructure—a perfect application for ferrying supplies to remote regions or disaster zones. Similarly, Pflaum’s research has designed a hexagonal parking construction to anchor a large number of airships in a relatively small area.

For decades, the age of airships has been just around the corner, but things are finally changing. Billionaire investors are getting behind the technology, and with the arrival of President Joe Biden’s climate bill, the government appears ready to put some serious money behind world-changing, green energy solutions. Whether airships are what the U.S. government has in mind remains to be seen.

“It’s the lack of public investment that’s really hurt the industry, but I think that is now changing,” Prentice says, “Because as Churchill * once said of [America] during the Second World War, the U.S. will eventually do the right thing, after they’ve exhausted all other options.”

And when it comes to decarbonizing aviation, there aren’t many options left.

* Editor’s note: This quote is frequently attributed to Churchill , though there is no evidence of him saying it.

Images and video courtesy of LTA Research.

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.

.css-cuqpxl:before{padding-right:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;} Pop Mech Pro .css-xtujxj:before{padding-left:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;}

Jumpstart Your Car With a Cordless Tool Battery

Lost Villa of Rome’s Augustus Potentially Found

Could Freezing Your Brain Help You Live Forever?

Air Force’s Combat Drone Saga Has Taken a Turn

China’s Building a Stealth Bomber. U.S. Says ‘Meh’

A Supersonic Bomber's Mission Ended in Flames

Who Wants to Buy the A-10 Warthog?

US Army Accepts Delivery of First M10 Assault Gun

Underwater UFO is a Threat, Says Ex-Navy Officer

DIY Car Key Programming: Why Pay the Dealer?

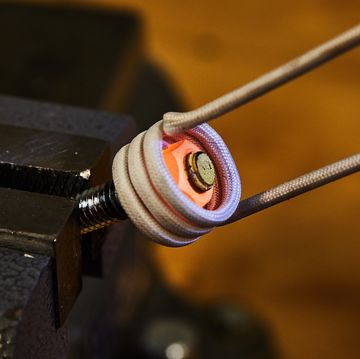

Use Induction Heat to Break Free Rusted Bolts

Inside of world's largest airship revealed in stunning images

New details about one of the world's largest aircraft, Airlander 10, reveal a spacious cabin with floor-to-ceiling windows (and plenty of legroom) inside the blimp-like exterior. And the futuristic aircraft will be loads better for the environment.

British company Hybrid Air Vehicles recently released concept images of its forthcoming airship, which is 299 feet (91 meters) long and 112 feet (34 m) wide, with the capacity to hold about 100 people. But rather than being crammed in like sardines, passengers will be treated to floor-to-ceiling windows and the kind of space and legroom commercial airlines currently reserve for business-class customers.

The firm thinks the vehicle, which is expected to enter service by 2025, will soon challenge conventional jets on a number of popular short-haul routes, thanks to its improved comfort and 90% lower emissions.

Related: Photos: Building the world's largest airship (Airlander 10)

"The number-one benefit is reducing your carbon footprint on a journey by a factor of 10," Mike Durham, Hybrid Air Vehicles' chief technical officer, told Live Science. "But also, while you're going to be in the air a little bit longer than you would if you were on an airplane, the quality of the journey will be so much better."

The Airlander is so much greener than a passenger plane, Durham said, primarily because it relies on a giant balloon of helium to get it into the air. In contrast, airplanes need to generate considerable forward thrust with their engines before their wings can provide the lift to get them airborne.

Once it's in the air, the airship relies on four propellers on each corner of the aircraft to push it along. In the first generation, two of these propellers will be powered by kerosene-burning engines, but the other two will be driven by electric motors, further reducing the vehicle's carbon emissions . By 2030, the company expects to provide a fully electric version of the Airlander.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rather than conventional batteries, liquid hydrogen fuel cells will power the Airlander's electric motors. Liquid hydrogen can store much more energy for a given weight than batteries, Durham said. The hydrogen will be kept in cryogenically cooled tanks in the hull and pumped to the fuel cells, where it will react with oxygen to generate electricity.

The airship design does come with some trade-offs, though. For one, its top speed will be about 80 mph (130 km/h), and it will generally average closer to 60 mph (100 km/h). That's closer to a car or train than a short-haul jet, which cruises at more than 450 mph (720 km/h).

For some intercity journeys of around 100 to 250 miles (160 to 400 kilometers), Durham said traveling from one city center to another is only slightly slower, thanks to the airship's ability to land in much smaller spaces or even on bodies of water.

For example, the company estimates that traveling between Seattle and Vancouver would take just over 4 hours by Airlander compared with slightly more than 3 hours by plane. Crucially, it would produce only 10 lbs. (4.6 kilograms) of carbon dioxide per passenger over that journey, compared with 117 lbs. (53 kg) for a conventional plane.

— Supersonic! The 11 fastest military airplanes

— Interstellar space travel: 7 futuristic spacecraft to explore the cosmos

— The Hindenburg wasn't alone: 23 intriguing airships

But considering the journey only takes 2.5 hours by car, passengers are more likely to be wooed by the aircraft's creature comforts than it's speed. On that front, Durham is confident the Airlander will be a much more pleasant experience than the alternatives. The cabin is such a small part of the vehicle's overall cross section that it has little effect on drag, which means the company has been able to make the airship much more spacious than a streamlined jet ever could be.

The floor-to-ceiling windows, combined with a cruising altitude below 10,000 feet (3,040 meters), means passengers will get spectacular views. And because the gigantic, helium-filled hull separates the engines from the cabin, there's little vibration and almost no noise. The aircraft is also largely unaffected by turbulence.

"Once you're up into the climb, you're pretty much running in a near-silent flight environment," Durham said.

Original article on Live Science.

Villa near Mount Vesuvius may be where Augustus, Rome's 1st emperor, died

When did humans start getting the common cold?

Dusty 'Cat's Paw Nebula' contains a type of molecule never seen in space — and it's one of the largest ever found

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 3 Scientists discover once-in-a-billion-year event — 2 lifeforms merging to create a new cell part

- 4 Quantum computing breakthrough could happen with just hundreds, not millions, of qubits using new error-correction system

- 5 DNA analysis spanning 9 generations of people reveals marriage practices of mysterious warrior culture

- 2 Plato's burial place finally revealed after AI deciphers ancient scroll carbonized in Mount Vesuvius eruption

- 3 Tweak to Schrödinger's cat equation could unite Einstein's relativity and quantum mechanics, study hints

- 4 Earth from space: Lava bleeds down iguana-infested volcano as it spits out toxic gas

- 5 Hundreds of black 'spiders' spotted in mysterious 'Inca City' on Mars in new satellite photos

Why the Airship May Be the Future of Air Travel

Just one short-haul flight a year produces 10% of our individual carbon emissions. 1 We could go back to trains for our traveling, which produce about half the CO2 of a plane, 2 but you don’t always have the time. What if we could get the speed of air travel with the lower emissions of ground-travel? Enter the airship.

When it comes to our individual carbon footprint, air travel is the emission-spewing Dumbo in the room. Flying less is the most impactful action you can take to bring down your CO2 quota. 3 Although aviation currently accounts for only 2% of the global carbon footprint, its impact is taking off pretty fast. 4 With the GHG emissions of the hydrocarbons-guzzling aircraft engines expected to increase more than 4 times by 2045, flying could reach 25% of the global carbon budget by 2050. 5 , 6 So, what do we do? A UK company, Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV) 7 , is launching a short-range airship service that will water down the carbon emissions of flight by 90%. 8 By 2025, you may be able to hop onboard their Airlander 10 and get dropped off a couple of hundred miles away. Because of its shape, the Airlander 10 has been nicknamed “the flying buttocks” 9 … thankfully the only gas inside this bad boy is helium … but airships could do more than just make us feel less guilty about a return flight on the weekend. One big benefit is that airships don’t require special infrastructure since flying boats don’t need a runaway for taking off and landing. This could translate into smaller sites located closer to cities, saving people from long commutes to airports, but the airship flexibility would be extremely beneficial for delivering food and humanitarian aid to isolated areas. Sounds uplifting … but before delving into the tech feasibility, let’s jump onboard our DeLorean balloon to fly back in time to where airships came from.

The airships’ turbulent history

Lighter-than-air (LTA) 10 vehicles fly through the sky like hot-air balloons, using LTA gases such as helium or hydrogen. While something like a hot-air balloon goes with the wind, airships have engines to ensure maneuverability. These vehicles can be rigid, semi-rigid or non-rigid. The last category, which includes blimps, rely on the pressure of the gas filling the balloon to keep their shape, while the other two types of machines are supported by an internal framework. But when did airships take off? Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin was the pioneer who led the way to rigid airships as we know it. He designed the first rigid motorized dirigible at the end of the 19th century, giving his name to the ancestor of modern airships.

Zeppelins became very popular for their travel comfort. It was like having a cruise in the sky. Much more relaxing than jolting up and down in a cramped plane. But a storm was brewing on the horizon, like the one Zeppelin LZ 14 flew into in 1913. 11 The dirigible lost control and dove into the North Sea before splitting in two, killing 14 people. As bad as that was, airships fate was sealed in 1937, when the Hindenburg went down like a lead balloon. With its 804-foot length, the German zeppelin was the largest dirigible ever constructed at that time. Because of the US export restrictions imposed on the Nazi regime, German designers used hydrogen instead of helium as the filling gas. But given the flammability of hydrogen, that wasn’t the best choice. At the end of one of its transatlantic cruises, the Hindenburg caught fire while landing in New Jersey and killed 36 people. 12 But safety wasn’t the only reason why airships floated away as a from of travel. In addition to being in the wrong place at the wrong time on the Hindenburg, you would’ve also spent a fortune on the trip. While it would shave 2 days off your Atlantic crossing, the trip would have cost you 5.5 times more than a third class ticket on an ocean liner. In today’s money, that would translate to around $8,200. 13

A Comeback to thrust forward

So, how come airships are rising back into the sky again after that bumpy ride? Some scientists are suggesting hydrogen-filled balloons as a more sustainable alternative for transporting the gas compared to maritime cargo shipping. 14 Researchers said the airships would require less energy and time to deliver the fuel than oceangoing cargo ships. How would that be possible? Their idea is to fly in the less turbulent stratosphere and make the most out of the jet stream, which is an air current that circles the globe from west to east reaching up to 140 mph. 15

You might be asking yourself the same question I did: isn’t this just going to be history repeating itself? The study considered using unmanned airships, which removes any risk for a human crew. Also, they argued some compelling points on the hydrogen controversy. While helium is safer, it’s more difficult to source and its availability is much more limited than hydrogen. Which makes its price higher. 16 Another perk of using hydrogen would be generating power and water through on-board fuel cells. But the fire risk is not the only challenge. At the stratosphere altitudes, the air pressure is lower. This means ultra-flexible materials need to be used for designing the airship gasbag. The trouble is these materials are not quite ready yet. 17

In the meantime, someone is already working on this setup. The Buoyant Aircraft Systems International (BASI) 18 is looking into hydrogen-filled airships to bring produce, construction equipment, and modular housing to the many off-the-grid communities in Canada. Designed to suit the Arctic climate conditions, BASI’s airships will be initially hybrid and then converted to a hydrogen fuel cell-power system.

While using helium rather than hydrogen, Lockheed Martin already offers an airship cargo service. 19 Their LMH-1 hybrid model stays aloft using 80% helium buoyancy topped by an aerodynamic lift. By minimizing the use of fossil fuels-driven direct lift, Lockheed Martin hybrid models consume less than 10% of a helicopter’s fuel. Also, their vehicles can be parked on any type of terrain thanks to an air cushion landing system (ACLS). Put simply, the ACLS is a massive inflatable doughnut underneath the blimp that makes airship touchdown a piece of cake. It also doubles as a really great hemorrhoid pillow. After 20 years of development, their versatile hovercrafts are now accomplishing a number of cargo missions. From delivering heavy equipment to hard-to-access areas hemmed in by icy roads in Alaska, to picking up workers and rare earth metals off isolated mines in Quebec 20 , to serving as a flying clinic for getting aid and tons of supplies into — and injured or refugees out of — accidents and natural disaster locations.

Varialift is working on a different hybrid model, combining solar-powered and conventional engines. 21 , 22 According to the UK company’s CEO, their floating ship would use only 8% of the fuel of a conventional jet over a transatlantic flight between the UK and the US. For the same payload, the firm also claims their machine and operational costs would be up to 90% less than a standard aircraft.

Yet, airships are not just about shipping goods. Since 2001, the German company Zeppelin NT has risen from the Hindenburg ashes. 23 Their gondola bags have a semi-rigid design, relying both on helium pressure and on a solid frame to support itself. Carrying up to 12 passengers, gasoline-powered Zeppelin NT airships have been used both for aerial sight-seeing and traveling purposes.

And going back to the eco-friendly Airlander 10 — the ‘flying buttocks’ — that I mentioned earlier, last May, HAV announced a number of routes that will be explored by their green flying machines in 2025. But you might be able to ride on one of HAV’s Airlander 10 even earlier. If you fancy an “experiential journey” to the North Pole, you can book your slot with OceanSky Cruises as soon as 2023. 24 But it will cost you a bit of money. Remember the Hindenburg golden ticket? Peanuts in comparison to this. The price tag for a two-person cabin on the Airlander 10 is $79,000. 25 As for lower-cost travel, HAV is currently trying to strike a deal with some other airlines. HAV’s CEO said the company aims at covering 47% of regional flights with a distance up to 230 miles. HAV touts the airship market will reach a value of $50bn over the next 20 years. However, by 2026, when they’ll start selling their vehicles, the estimated value might be only around $165 million. 26

With a capacity of 100 passengers, the company claims their hybrid-electric dirigibles will take as long as conventional flights yet have a tenth of their carbon footprint. 27 That applies whether traveling from Liverpool to Belfast or from Seattle to Vancouver. At least, based on company calculations. Although flying at a top speed of only 130 mph, the airship doesn’t need a runway and could take off from and land in pretty much any flat open area, including water. This city center-to-city center traveling mode makes these vehicles flexible and independent from airports…or ports… if you like? That means you’d save time on commuting. But how safe are HAV’s airships? Fire risk is extinguished by filling the balloon with helium. Yet, one of their prototype tests crashed while landing in 2016. 28 However, HAV machines will be certified by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), which means it will have to conform to the same safety standards as other aircraft.

So, how green is the Airlander 10 technology? Combining the helium buoyant effect, an aerodynamic lift and a helicopter-like thrust, HAV’s hybrid design is more efficient than comparable aircrafts. Leveraging the helium lift, the vehicle reduces the consumption of the fossil fuel-burning engine and could carry a higher payload. Also, the UK Aerospace Research and Technology Programme awarded the company with a £1M grant to develop a prototype fully powered by a 500 kW electric motor. And they aren’t stopping there because the Airlander 10 could feature battery and solar cell technology. 29

What’s puncturing the airship’s balloon?

More cargo, less carbon emissions, no infrastructure required. Sounds like airships are on the rise, right? But is there anything that could hold them down? or on the water? Cost might be one thing. One factor that could inflate the airships operational cost is the gasbag filling. And I’m not talking about myself. Helium is a non-renewable source and we may experience a shortage in the future. 30 While hydrogen could work as an alternative for unmanned cargo missions, it would probably be too risky to use with passengers on board. According to Julian Hunt, a researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), using a cargo airship would currently cost up to 50 times more than standard ships. He also said we should invest up to $100 billion over the next 20 years in technological improvements to make airshipping compete with conventional shipping. 31 Sir David King, the former UK Chief scientist and climate change specialist is more optimistic than Hunt, saying that the cost of a Varialift airship would be comparable to a jumbo jet. 32 Also, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), airships would be more cost-effective than jetliners for freight transport. 33 That’s because of the lower fuel consumed during take off and landing as well as the higher payload carried by the flying boats. 34 The UK Advanced Technologies Group Ltd. (ATG) estimated the freight cost per ton kilometer for three hybrid cargo airships of different capacity. At the lowest payload, the airship would cost slightly more than a standard aircraft. However, for the medium and top capacities, ATG model simulations predicted airships to compete with trucking and maritime shipping respectively. 35 But airships may not be only competitive for cargo deliveries. A 1980 study suggested that a 420-ton airship would be a cost-effective way of ferrying both passengers and their cars from the U.S. mainland to Hawaii. A more recent and comprehensive study compared the economic feasibility of airships to that of airplanes and helicopters. 36 Researchers found airships to be the most profitable transport solution when considering long distances (up to 5,000 km) and a high carrying capacity.

The flight path to sustainable aviation

Hybrid and fully electric airships may be a greener alternative for fast travel over short distances. Plus, their greater flexibility can play a key role for delivering cargo to hard-to-reach regions and for performing rescue operations. Data on cost effectiveness seems to be lacking and controversial. Also, airships’ technology may need further investments to catch up with competitors. But eco-friendly flying boats could be a key part of a zero-carbon aviation strategy along with electrical aircrafts and more sustainable fuels. It’s also got the cool steampunk, retro-futurist vibe to it.

- “How Bad Are Bananas?: The Carbon Footprint of by Mike … – Alibris.” ↩︎

- “Plane, Train or Automobile: Which Has the Biggest Footprint?” ↩︎

- “To fly or not to fly? The environmental cost of air travel | Human … – DW.” 24 Jan. 2020 ↩︎

- “‘Worse Than Anyone Expected’: Air Travel Emissions Vastly Outpace ….” 20 Sept. 2019 ↩︎

- “A40-WP/54 – ICAO.” 7 May. 2019 ↩︎

- “Analysis: Aviation could consume a quarter of 1.5C carbon budget ….” 8 Aug. 2016 ↩︎

- “Hybrid Air Vehicles.” ↩︎

- “Airships for city hops could cut flying’s CO2 emissions by 90% | Air ….” 26 May. 2021 ↩︎

- “Will Airships Have A Place In The Future Of Aviation? – Simple Flying.” 9 Apr. 2021 ↩︎

- “Lighter-Than-Air – Centennial of Flight.” ↩︎

- “Zeppelin Disasters – List of Airship Accidents – Zeppelin History.” ↩︎

- “Hindenburg | German airship | Britannica.” ↩︎

- “Transatlantic transportation costs in 1937 – Outrun Change.” 2 Oct. 2017 ↩︎

- “Using the jet stream for sustainable airship and … – ScienceDirect.com.” ↩︎

- “jet stream | National Geographic Society.” ↩︎

- “Zeppelins stopped flying after the Hindenburg disaster … – NBC News.” 19 Aug. 2019 ↩︎

- “Planes Are Ruining the Planet. New, Mighty Airships Won’t. | by ….” ↩︎

- “Buoyant Aircraft Systems International.” ↩︎

- “Hybrid Airship | Lockheed Martin.” ↩︎

- “Canadian rare earths mine to transport ore using airships – MINING ….” 22 Nov. 2016 ↩︎

- “Varialift – unique heavy lift and transport solution – Varialift.” ↩︎

- “A solar-powered airship is being built to transport cargo more greenly.” 2 Oct. 2019 ↩︎

- “Home | Zeppelin-NT am Bodensee.” ↩︎

- “Reservations – OceanSky Cruises.” ↩︎

- “Boarding soon: the five-star airship bound for the … – Financial Times.” 11 Oct. 2019 ↩︎

- “Airship Market 2021 is estimated to clock a modest CAGR of 7.4 ….” 4 Apr. 2021 ↩︎

- “Airlander 10 will provide a new option for regional travel – HAV.” ↩︎

- “World’s biggest aircraft crashes in Bedfordshire | Air … – The Guardian.” 24 Aug. 2016 ↩︎

- “HAV – Hybrid Air Vehicles.” ↩︎

- “How A Helium Shortage Could Put The Brakes On The Tech Boom.” 13 May. 2021 ↩︎

- “Could Airships Rise Again? – IEEE Spectrum.” 23 Sept. 2019 ↩︎

- “Emissions-free air freight? How about a solar-powered helium airship.” 19 Jan. 2016 ↩︎

- “Blimps could replace aircraft in freight transport, say … – The Guardian.” 30 Jun. 2010 ↩︎

- “Cargo Airships – Canadian Transport Research Forum.” ↩︎

- “The Return of the Airship – University of Manitoba.” ↩︎

- “Economic Feasibility of Using Airships in Various … – TEM Journal.” 28 Aug. 2020 ↩︎

Free Heat For Your Home? Exploring Computer Waste Heat Recovery

Exploring earthship homes – ultimate efficiency, you may also like.

Why the Future of AI & Computers Will Be Analog

Are Airships Finally Making Their Comeback?

Why Everyone is Wrong about the Apple Vision Pro (including me)

5 BEST Things I Saw in Vegas at CES 2024

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

More in Clean Transport

3 Ways Transportation Will Change In the Future

Now Boarding: Renewable Mass Transit Systems

The Best Time to Get an Electric Bicycle is Now

How Soon Can We Ride With Electric Flights?

Login with patreon.

Join the Community

- Early access & ad free videos

- Members only discord chat

- Monthly Q&A video calls

Thinking of Going Solar?

Save Money | Gain Security | Take Control

A video guide to help you through hiring an installer and the solar installation process.

Listen to the Podcast

Recent posts.

Top 5 Reasons We’re Getting Ripped Off With Solar … or Are We?

2024 Perovskite Breakthroughs are the Future of Solar

How a Sand Battery Could Revolutionize Home Energy Storage

- Energy Production

- Energy Storage

- All Renewable Posts

- Clean Transportation

- Electric Vehicles

- All Tech Posts

- Electrify Everything

- All Reviews

Join our weekly newsletter!

AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE

Airships rise again.

Zero emissions and a million pounds of lift renew the appeal of these century-old giants.

:focal(2132x2586:2133x2587)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/f7/d4f7cc05-fef1-4202-b60d-11fd48551ed7/opener.jpeg)

Tom Grundy, the CEO of Hybrid Air Vehicles, started his career working on fighters and drones for BAE Systems, and he was a project engineering manager for Airbus during the development of the A380. But these days his focus is on a type of aircraft that can do things the fixed-wing fliers he has spent his life admiring can’t—even though the basic technology keeping them aloft is substantially older. Welcome to the second age of the airship.

Grundy’s company is promoting its striking, pillow-like AirLander 10, initially designed for military surveillance, as a pleasant, low-emission alternative means of regional air travel. In May the company announced plans to begin service for up to 100 passengers per flight on a handful of short-haul routes (Liverpool to Belfast, Oslo to Stockholm, Seattle to Vancouver, among others) in 2025. A Scandinavian company is in talks about using the AirLander to give tours of the North Pole.

The chief market for the airships of the 21st century, however, will not be passenger service but freight hauling. The new airships can carry heavier loads farther and cheaper than helicopters can, with lower emissions than fixed-wing aircraft—potentially zero emissions, if the ships are powered by hydrogen fuel cells.

Historically, there have been two major types of airship. Rigid airships, as the name implies, are built around a hard skeleton. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin of Germany flew the first rigid airships, and on his account, they are sometimes called Zeppelins. The other type of airship is non-rigid. Non-rigid airships have no skeleton. They consist of an envelope inflated with a lifting gas such as helium, from which is suspended a gondola for crew, passengers, and cargo. The familiar Goodyear blimps have been mostly non-rigid airships.

The engineers at Hybrid Air Vehicles looked at the history of rigid and non-rigid airships and came down solidly on the non-rigid side—with a twist. Rather than the cigar or American football shapes of past airships and blimps, the AirLander looks more like a pillow. A radically different design, it’s a lifting body—and heavier than air. It relies on both aerostatic lift from helium and aerodynamic lift to fly, making it a hybrid airship. “About 40 percent of our lift is aerodynamic,” Grundy says. “When we turn our engines off and we slow down, we’re heavier than air. We come down and land just like airplanes do.”

The appealing energy efficiency of airships comes from their ability to float in the air as boats do on water—so it seems strange to purposefully erode that lighter-than-air quality. But there is another, problematic side to aerostatic buoyancy. “If you are taking 50 tons of cargo to a remote part of the world,” Grundy says, “and you want to put that 50 tons down in [that same spot], you now have 50 tons of buoyancy you have to deal with.” Like a pool float held underwater, it’s going to surge upward once you let off the pressure. Airships of yore would manage by venting lifting gas (not something you want to do with limited and expensive helium), taking on ballast, and elaborate rope and mooring procedures. That’s a nonstarter if you want to make money taking big things to places with little infrastructure, Grundy says, but he believes the AirLander is the answer.

When the AirLander had its first flight in Lakehurst, New Jersey in 2012, it was intended as a U.S. Army surveillance craft. The Army canceled that program the following year, and HAV brought the ship across the Atlantic to Cardington, about 60 miles north of London, for a 2016 series of flights that would test its viability for civilian use. In November 2017, the unoccupied AirLander broke free from its mooring mast and deflated. Grundy says the lessons of this incident resulted in improvements to the production model, which remains on schedule. “Our base business plan sees us delivering 12 aircraft per year” beginning as soon as 2025, he says.

Gentle Giant

The Graf Zeppelin was 776 feet long. Even non-rigid airships could be enormous, according to Wichita State University professor of aerospace engineering Brandon Buerge. He cites the U.S. Navy’s N-Class blimps of the 1950s, tasked with anti-submarine and early-warning missions. They could be as large as 400 feet long and 120 feet tall, “bigger than anything we’ve been flying with any regularity,” Buerge says.

Early on, the German Zeppelins racked up an impressive record for safety and capability. The Graf Zeppe lin flew more than a million miles beginning in 1928, circumnavigated the globe, and lifted more than 43 tons. “How long did it take before fixed-wing aircraft caught up?” Buerge asks. (About 30 years. The C-133 Cargomaster—first heavy lifter in the U.S. Air Force—entered service in 1958 and could carry more than 55 tons, but it had four jet fuel-guzzling turboprops.)

Still the rigid giants eventually proved fragile. The German airships used flammable hydrogen for lift, which led to the Hindenburg disaster. And the U.S. Navy’s rigid airships displayed an alarming tendency to break up in bad weather. The Germans scrapped the Graf Zeppelin at the start of World War II, while the American Navy stuck with non-rigid blimps, using them to escort shipping convoys. The blimps proved much more resilient, with one N-Class blimp, the Snowbir d, crossing the Atlantic twice and beating the Graf Zeppelin ’s record for endurance by flying for more than 264 hours through all kinds of weather.

“Those are the ships they would plow through ice storms,” Buerge says. “It’s hard to kill a non-rigid airship.”

As you approach Moffett Federal Air Field in Sunnyvale, California, Hangars Two and Three are easily visible from U.S. 101, their parabolic apexes and massive door frames hulking over the relatively flat desert landscape. Seeing them from a distance does not prepare you for the feeling of their immensity as you stand between them. The giant hangars channel the early summer breeze like a box canyon. In the 1930s, they housed U.S. Navy airships like the Macon , a behemoth 785 feet long and 150 feet high. More recent tenants include the California Air National Guard and NASA.

The current occupant of Hangar Two, LTA Research, is using it to house airships again. My tour guides on this bright June morning are LTA CEO Alan Weston and LTA chief of operations James McCormick, who acts as a sort of ground wire for Weston’s seemingly boundless energy. Inside the hangar, a chorus of birdsong echoes down from the rafters far overhead.

Before us stands the naked, cigar-shaped skeleton of the airship they have dubbed Pathfinder 1, a 400-foot-long vessel that could easily swallow the fuselage of the Boeing 737 that brought me to California. It’s more organic sculpture than airframe, a latticework of black carbon-fiber tubes rising like the bones of an ancient leviathan awaiting its taxidermied skin—in this case, high-tech sailcloth.

“Isn’t that cool?” Weston asks.

His excitement is catching, but he is in some ways a strange ambassador for the return of a technology that for most of the last 70 years has been more prevalent in science fiction than in the real world, those floating billboards hovering over football stadiums notwithstanding. “Most of my career has been in spacecraft and rockets,” Weston says. He designed kill vehicles for President Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars program and spent 23 years doing research and development for the U.S. Air Force. Then he served as director of programs at NASA Ames Research Center until his retirement in August 2013.

Retirement did not last long. Late that same year, Google co-founder Sergey Brin asked Weston to create a company to build an airship that could carry cargo on his humanitarian relief missions.

Weston’s enthusiasm for his new project grew as he studied the history of airships. The Hindenburg disaster of 1937 might have been the death of airships in the popular imagination, but there have been fresh design efforts in every decade since. (John McPhee’s book The Deltoid Pumpkin Seed documents a push by a strange coalition of former Navy airship men and Presbyterian ministers to develop a hybrid airplane/rigid airship in the 1970s. Their ship flew, but no one wanted it. Their dreams of at once revolutionizing air freight and missionary work went unfulfilled.)

His history lessons complete, Weston concluded that the challenges that plagued the older rigid airships could be overcome. They would use non-flammable helium as a lifting gas, for starters. And the flaws that brought down Navy airships like Akron and Macon —a faulty altimeter and structural damage, respectively—could be corrected with modern avionics and strong, light materials. Each of the 13 rib-like carbon fiber “mainframes” that make up the length of Pathfinder 1 weighs just 600 pounds, but together, they support a vessel with 28 tons of lift. A broken carbon tube can be replaced in-flight.

“The beautiful thing about a rigid airship is you can almost do anything you want,” Weston says. “The problem with all these blimps is you don’t have any hard points.”

Pathfinder 1 will support a gondola, diesel generators, solar panels, batteries, electric motors, and vectored thrust propellers, as well as a small gangway running the length of the envelope for accessing the interior frame. While LTA will not disclose the dimensions of its in-development Pathfinder 3, it will be substantially more capacious than Pathfinder 1, with room enough in the crew gangway for passengers and for hydrogen—for fuel cells, rather than for lift.

Beyond Pathfinder 3, LTA aims to build a massive rigid airship that will dwarf the Zeppelins of the past. All LTA will say on the record about its next-gen giant is that it will be too big to be built in Sunnyvale—LTA is in the process of moving into the former Goodyear Airdock hangar in Akron, Ohio. “The AirDock goes on top of this,” Weston says, gesturing up toward Hangar Two’s distant ceiling. “This is 160 feet tall. The AirDock is 200 feet tall.”

That ship isn’t scheduled to fly until 2023 at the earliest, and Weston and his team have plenty to keep them busy in the meantime, like fully outfitting Pathfinder 1 and flying it to its new home in Akron—following a series of flight tests around the San Francisco Bay area.

Though Weston hopes to begin these short-distance “camping trips” this year, they are currently unscheduled. “History is full of airship projects that crashed or something bad happened because people were in a rush,” Weston says. “We’re going to be careful.”

Igor Pasternak shares Tom Grundy’s view that buoyancy control is key to building a commercially practical airship. The founder of Worldwide Aeros Corporation in Montebello, California, Pasternak built tethered balloons called aerostats as a teenager growing up in Ukraine. Airships, he says, are “what I have been doing all my life.”

He thinks, though, that relying on aerodynamic lift and vectored thrust will limit an airship’s operational capacity. Requiring a runway, even a short one, is another limitation. The vehicle under construction at Worldwide Aeros, the Aeroscraft Dragon Dream, is a non-cylindrical rigid airship. It takes a different approach than Hybrid’s AirLander, using a low-pressure system to compress and release helium to modulate the lift of the airship—compress the helium, shrink its volume, and you reduce aerostatic lift. Prove a heavy-lifting airship can perform true vertical take-offs and landings without ground infrastructure, Pasternak says, and “we are talking about a huge shift, dramatic shift” in the transport business.

That proof is yet to come. The design review for the Dragon Dream operational demonstrator was completed only last summer, and he won’t say when its next test flight will be. As with LTA, he’s pushing the humanitarian applications of airships, having entered into a partnership with the World Food Program that he hopes will eventually see his invention delivering food to famine-struck regions.

The emphasis on charity might help to cover up some observers’ skepticism. “Hope springs eternal” is what aviation analyst Richard Aboulafia says when I ask him if the new airship ventures will change the market. “Frankly, it doesn’t scale,” he explains. “Air travel is all about scale, getting 300 people into a 777. You just can’t do that with these things.”

He can’t readily think of a cargo someone would need to send faster—and at a higher price—than by ship, but slower than by jet. And exotic cargo flown to remote locales is often a one-way trip. “Air cargo is all about equipment utilization, with UPS and FedEx being the best examples of that,” he says. “They have these elaborately choreographed route networks that are all about efficient use of equipment and not having too many one-way trips.”

LTA, Weston admits, is in a privileged position. With a nonprofit humanitarian mission and the backing of some of the world’s wealthiest people, Weston has been freed to think about the challenges of lighter-than-air flight one step at a time. He wants to build airships with no carbon footprint, and so hopes to utilize hydrogen fuel cells in Pathfinder 3 and beyond. Combine oxygen from the air and on-board hydrogen in a fuel cell and you can generate power as well as water, both for consumption and for ballast. “You’re generating the stuff you’re going to drink and use to wash your hands and take a shower with as you are flying around,” Weston says. “We actually gain weight with the water. One kilogram of hydrogen generates nine kilograms of water, so we have plenty of buoyancy control.”

He muses that the success of airships in humanitarian relief could spur the market more generally. Perhaps low-cost, hydrogen-powered cargo airships could spur other industries, such as shipping, to transition to hydrogen power. “I view this as the project of a lifetime,” Weston says. “There’s more opportunity, in my head, to do something useful than anything I’ve ever seen.”

To Buerge the aerospace engineer, helicopters seem like a reasonable analogy to the new airships. “I don’t ride on a helicopter with any regularity, and you probably don’t either,” he says. But even though the civilian helicopter market isn’t near the size of the commercial aircraft industry, “I wouldn’t call helicopters an unsuccessful technology, or a technology that doesn’t exist in a serious way.”

And there’s one element of airships that hasn’t been tested seriously in recent memory: the experience of flying in one.

Buerge once flew in two blimps, a Polar 400 and a Skyship 600, on one of those warm summer days that generate puffy clouds and bumpy rides in fixed-wing aircraft. The dynamics were more like a boat than an airplane, the bow coming up gradually, the ship gliding over a thermal, and then down again. Smooth. “The response isn’t anything that someone that is used to flying in heavier-than-air vehicles would interpret as turbulence,” he says. “It was as close to a magic carpet as I have ever experienced.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Jon Kelvey | | READ MORE

Jon Kelvey is a writer and freelance journalist focusing on science, health and aerospace.

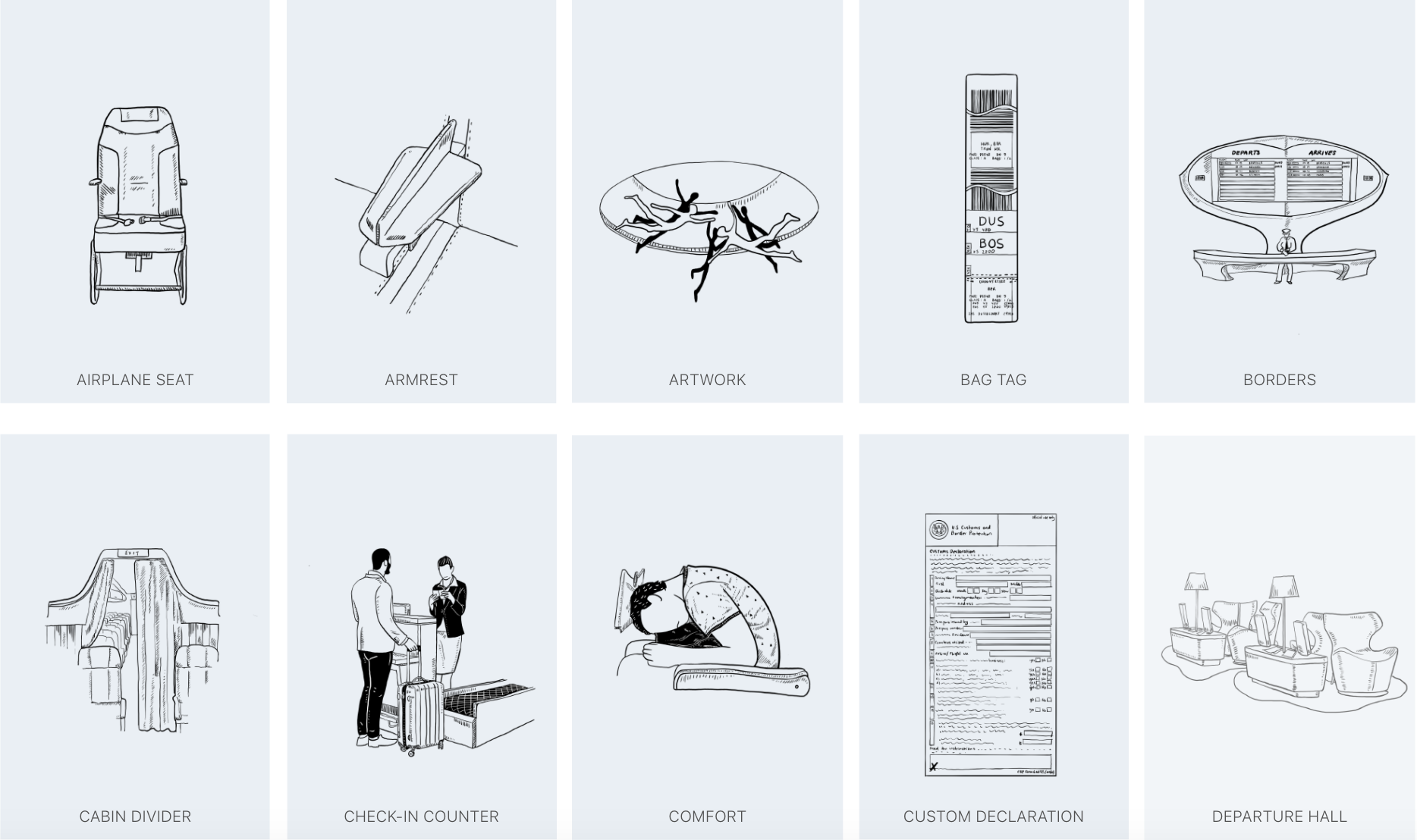

- The Future of Air Travel: Toward a better in-flight experience

A snapshot from Air Travel Design Guide, illustrating artifacts, spaces, and systems that impact the passenger experience in travel. Illustrations by Isa He

Anyone remember air travel? In early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe and international flights were hurriedly cancelled, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Laboratory for Design Technologies (LDT) pivoted its three-year focus project, The Future of Air Travel , to respond to new industry conditions in a rapidly changing world. With the broad goal of better understanding how design technologies can improve the way we live, the project aims to reimagine air travel for the future, recapturing some of its early promise (and even glamour) by assessing and addressing various pressure points resulting from the pandemic as well as more long-term challenges.

The two participating research labs—the Responsive Environments and Artifacts Lab (REAL) , led by Allen Sayegh , associate professor in practice of architectural technology, and the Geometry Lab, led by Andrew Witt , associate professor in practice of architecture—“look at air travel from an experiential and a systemic perspective.” As part of their research, the labs consulted with representatives from Boeing, Clark Construction, Perkins & Will, gmp, and the Massachusetts Port Authority, all members of the GSD’s Industry Advisors Group .

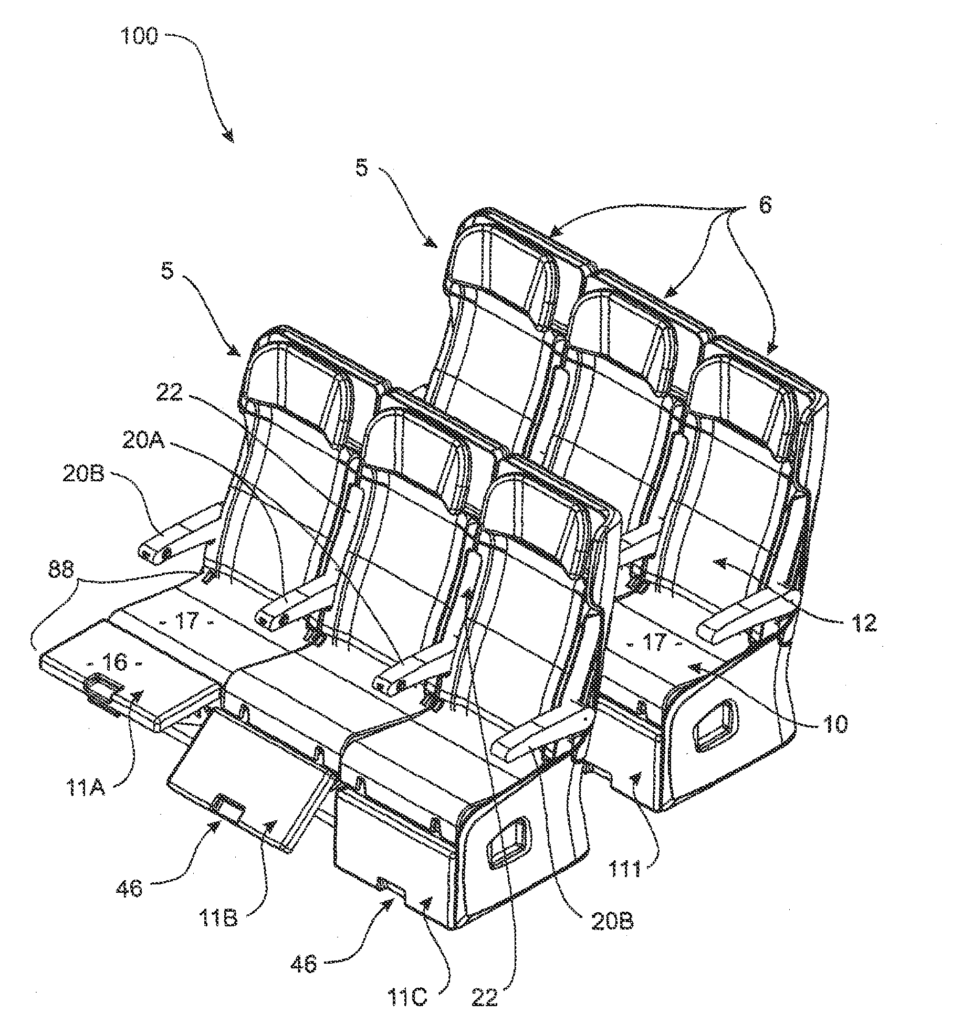

So far, the project has resulted in two research books: An Atlas of Urban Air Mobility and On Flying: The Toolkit of Tactics that Guide Passenger Perception (and its accompanying website www.airtraveldesign.guide ). On Flying , by Sayegh, REAL Research Associate Humbi Song , and Lecturer in Architecture Zach Seibold , seeks “to facilitate a rethinking of how to design objects, spaces, and systems by putting the human experience at the forefront”—and in so doing “prepare and design for improved passenger experiences in a post-COVID world.” The book’s accessible glossary covers topics including the design implications of the middle armrest (“What if armrests were shareable without physical contact?”); whether the check-in process could be improved by biometric scanners; the effect of customs declarations on passengers; how air travel is predicated on “an absence of discomfort” instead of maximizing comfort; and the metaphysical aspects of jet lag.

The project “examines and provides insight into the complex interplay of human experience, public and private systems, technological innovation, and the disruptive shock events that sometimes define the air-travel industry”. Consider, for instance, the security requirements of air travel in a post-COVID world—how can the flow of passengers through the departure/arrival process be streamlined while incorporating safety measures such social distancing?

On Flying acknowledges that it’s hard to quantify many of the designed elements—ranging from artifacts to spaces and systems—that affect our experience of air travel. So the toolkit methodically catalogs and identifies these various factors before speculating on alternative scenarios for design and passenger interaction. A year into the project, Phase 2 will more overtly examine the context of COVID-19, considering it alongside other catastrophic events, such as 9/11, in order to better understand and plan for their impact on the industry as a whole and on passenger behavior.

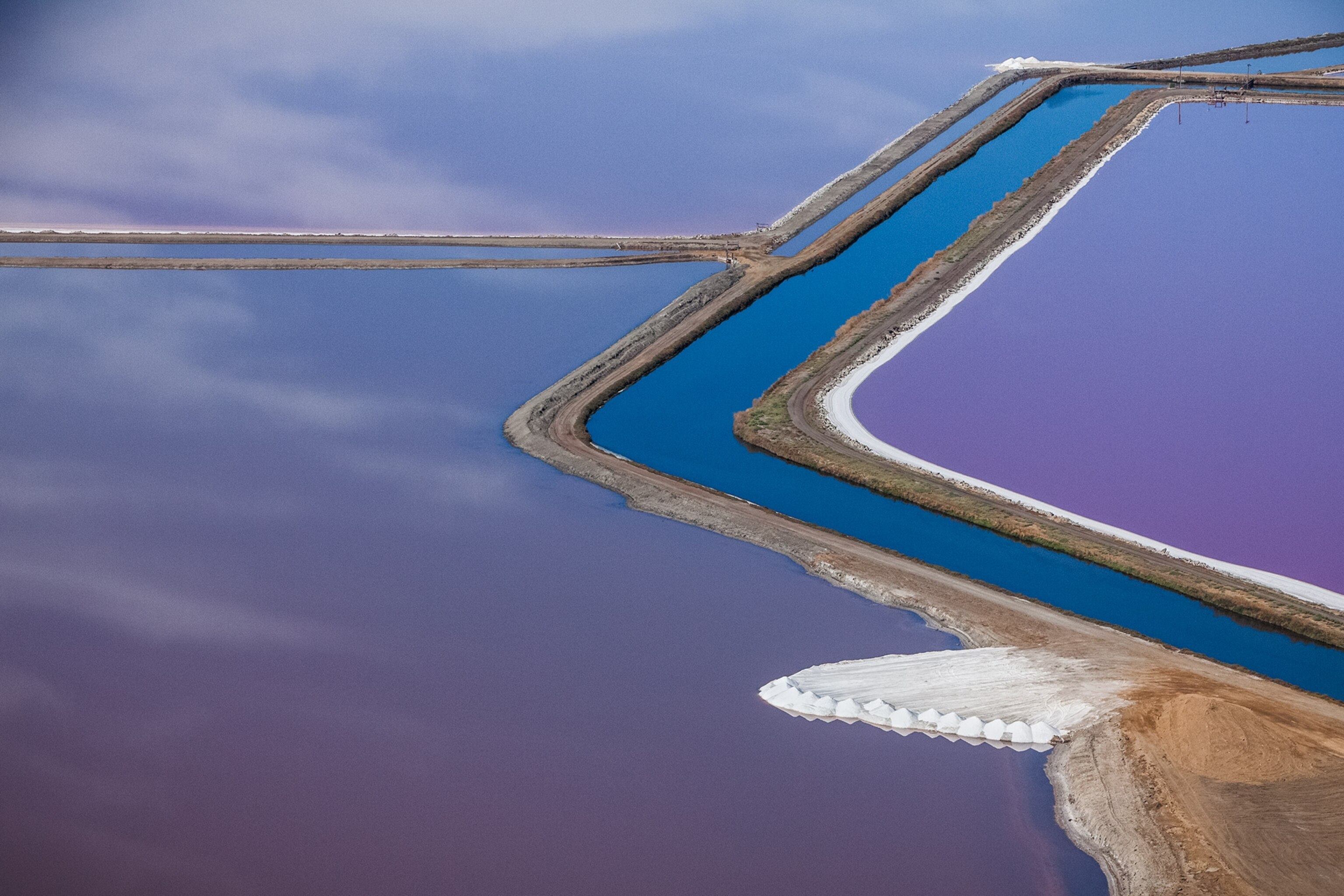

Meanwhile, An Atlas of Urban Air Mobility , by Witt and Lecturer in Architecture Hyojin Kwon , is “a collection of the dimensional and spatial parameters that establish relationships between aerial transport and the city,” and it aims to establish a “kit of parts” for the aerial city of the future. Phase 1 considered the idea of new super-conglomerates of cities, dependent on inter-connectivity of air routes—specifically looking at the unique qualities of Florida as an air travel hub. The atlas investigates flightpath planning and noise pollution and other spatial constraints of air travel within urban environments. One possible solution it raises is the concept of “clustered networks,” where electrical aerial vehicles could be used in an interconnected pattern of local urban conurbations, reflecting a hierarchy of passenger flight, depending on scale and distance traveled.

Phase 2 will move into software and atlas development, expanding the atlas as well as their simulation and planning software. One intriguing aspect will be a critical history of past visions of future air travel: a chance to look back in order to look forward with fresh eyes. By studying our shared dream of air travel, the hope is to rediscover and reboot abandoned visions that may yet prove to inspire new innovations.

It’s a reminder that, not so long ago, international flight excited and inspired us—before the realities of delayed flights, lost luggage, rude customs officials, and poorly planned infrastructure stole our dreams. And that’s before we ever stepped onto the plane itself. According to the Air Travel Design Guide , the social contract of air travel has now become so skewed from the original glamorous proposition that today, “the passenger can feel as if they are at the mercy of nature, airport security personnel, or the airline cabin crew. They are directed where to go, how to move, and even when to go to the bathroom on the plane.”

Surely it can—and should—be better than this?

“We may not arrive more on time,” the team concludes, “but thanks to the introduction of better design practice—we might enjoy the experience better.”

Learn more about the Laboratory for Design Technologies and its Industry Advisors Group (IAG) partners at research.gsd.harvard.edu/ldt/

- Responsive Environments

- Transportation

- Responsive Environments and Artifacts Lab’s “PULSUS” featured in Domus

- How can design improve disease modeling and outbreak response? A simulation tool by GSD alum Michael de St. Aubin offers answers

- From 3D-printed face shields to strategies for a just recovery: How the Harvard Graduate School of Design community is contributing to COVID-19 response efforts

- Rethinking the “Room” through the Pandemic: Isolation, Openness, and Confrontation

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Airships for city hops could cut flying’s CO2 emissions by 90%

Bedford-based blimp maker unveils short-haul routes such as Liverpool-Belfast that it hopes to serve by 2025

For those fancying a trip from Liverpool to Belfast or Barcelona to the Balearic Islands but concerned about the carbon footprint of aeroplane travel, a small Bedford-based company is promising a surprising solution: commercial airships.

Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV), which has developed a new environmentally friendly airship 84 years after the Hindenburg disaster, on Wednesday named a string of routes it hoped to serve from 2025.

The routes for the 100-passenger Airlander 10 airship include Barcelona to Palma de Mallorca in four and a half hours. The company said the journey by airship would take roughly the same time as aeroplane travel once getting to and from the airport was taken into account, but would generate a much smaller carbon footprint. HAV said the CO2 footprint per passenger on its airship would be about 4.5kg, compared with about 53kg via jet plane.

Other routes planned include Liverpool to Belfast, which would take five hours and 20 minutes; Oslo to Stockholm, in six and a half hours; and Seattle to Vancouver in just over four hours.

HAV, which has in the past attracted funding from Peter Hambro, a founder of Russian gold-miner Petropavlovsk, and Iron Maiden frontman Bruce Dickinson , said its aircraft was “ideally suited to inter-city mobility applications like Liverpool to Belfast and Seattle to Vancouver, which Airlander can service with a tiny fraction of the emissions of current air options”.

Tom Grundy, HAV’s chief executive, who compares the Airlander to a “fast ferry”, said: “This isn’t a luxury product it’s a practical solution to challenges posed by the climate crisis.”

He said that 47% of regional aeroplane flights connect cities that are less than 230 miles (370km) apart, and emit a huge about of carbon dioxide doing so.

“We’ve got aircraft designed to travel very long distances going very short distances, when there is actually a better solution,” Grundy said. “How much longer will we expect to have the luxury of travelling these short distances with such a big carbon footprint?”

Grundy said the hybrid-electric Airlander 10 could make the same connections with 10% of the carbon footprint from 2025, and with even smaller emissions in the future when the airships were expected to be all-electric powered.

“It’s an early and quick win for the climate,” he said. “Especially when you use this to get over an obstacle like water or hills.”

HAV said it was in discussions with a number of airlines to operate the routes, and expected to announce partnerships and airline customers in the next few months. The company has already signed a deal to deliver an airship to luxury Swedish travel firm OceanSky Cruises, which has said it intends to use the craft to offer “experiential travel” over the North Pole with Arctic explorer Robert Swan.

Grundy said the company was in the final stages of settling on a location for its airship production line, which he hoped would be in the UK. He said the company would hire about 500 people directly involved in building the craft, and it would support a further 1,500 jobs in the supply chain. The company currently employs about 70 people, mostly in design, at its offices in Bedford. He said the company aimed to produce about 12 airships a year from 2025.

The craft was originally designed as a surveillance vehicle for intelligence missions in Afghanistan. HAV claims independent estimates put the value of the airship market at $50bn over the next 20 years. It aims to sell 265 of its Airlander craft over that period.

The £25m Airlander 10 prototype undertook six test flights, some of which ended badly. It crashed in 2016 on its second test flight, after a successful 30-minute maiden trip. HAV tweeted at the time: “Airlander sustained damage on landing during today’s flight. No damage was sustained mid-air or as a result of a telegraph pole as reported.”

The aircraft, which can take off and land from almost any flat surface, reached heights of 7,000ft (2,100m) and speeds of up to 50 knots (57mph) during its final tests. The company has had UK government backing and grants from the European Union.

- Air transport

- Greenhouse gas emissions

- Climate crisis

Most viewed

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

- PLANET POSSIBLE

Greener air travel will depend on these emerging technologies

Electric engines, alternative fuels, and better navigation could reduce emissions—and mitigate the impacts of a global return to the skies.

The sky over Cologne, Germany, is crisscrossed by condensation trails from airplanes. Because the pollutants in these so-called “contrails” contribute to climate change, researchers are studying ways to eliminate them—one of several ongoing efforts to make flying more sustainable.

Here’s a word you may have overlooked in 2020: flygskam, a Swedish term for the feeling of being ashamed to fly. In a year that saw a 66 percent decrease in flights, compared to 2019, you might think that flygskam has flown the coop.

But with a recent uptick in air traffic—and the anticipation of travel’s rebound thanks to COVID-19 vaccines —flygskam is taking flight again. The term originated in 2017 as part of a campaign to change how we fly, from the frequency of our flights to the technology of our aircraft. The goal: to mitigate the carbon dioxide emissions that experts think may triple by 2050 .

Aviation accounts for a relatively small portion of global emissions—2.5 percent. While bigger culprits, such as electricity and agriculture, account for greater emissions, they also benefit billions of people. Airline emissions, in contrast, come mostly from rich travelers in the richest countries: business class passengers produce six times as much carbon as those in economy class, and one percent of the most frequent fliers are responsible for half of all aviation’s carbon emissions.

Will the pandemic -caused travel slowdown be enough to shake up aviation and produce lasting benefits for the environment? In 2020, the drop in air traffic likely reduced carbon emissions by several hundred million tons . Some are calling to make those reductions permanent by eliminating contrails, using new fuels, improving navigation, and more. With climate change reaching a point of no return as early as 2035 , action will need to happen quickly.

( Wondering what you can do? Here are 12 ways to travel sustainably in the new year .)

Of course, flying less would have an even bigger impact, and there are calls for travelers to fly only once a year , give up flying for a year , and attend conferences virtually . Still, air travel is here to stay, so the cleaner the better. Here are some of the ways flying could clean up its act in the years to come.

Curtailing the contrails

Aviation emits more than carbon dioxide; it also produces water vapor, aerosols, and nitrogen oxides. These pollutants absorb more incoming energy than what is radiated back to space, causing Earth’s atmosphere to warm. This means aviation’s impact on warming might be an even bigger share than its carbon footprint.

The turbine engines of commercial aircraft, like this one at a maintenance facility in Singapore, rely on kerosene-based propellants. Companies are experimenting with biofuels and synthetic fuels that can reduce carbon dioxide emmissions.

An Airbus A300-600R makes its final approach before landing. The company plans to have a hydrogen-fueled plane in service by 2035.

The worst of the non-carbon impacts are from contrails, short for condensation trails: the line-shaped clouds that form from a plane’s engine exhaust. A small number of flights are responsible for most contrails. This is because contrails form only in narrow atmospheric bands where the weather is cold and humid enough.

Avoiding those zones could make a big difference in limiting aviation’s non-carbon pollution. One research paper modeling Japan’s airspace found that modifying a small number of flight routes to skip these areas could reduce contrails’ effects on the climate by 59 percent. The change would be as little as 2,000 feet above or below these regions. While flying a plane higher or lower can reduce its efficiency and require more jet fuel, the paper found that limiting contrails would still offset any additional carbon emissions.

“There is a growing realization that the impact of contrails is a really significant component of aviation’s climate impact,” says Marc Stettler, one of the paper’s authors and a lecturer on transport and the environment at Imperial College London .

The spots where contrails can form change from day to day, so airlines need accurate, multi-day weather forecasts to avoid them. In the future, pilots could report contrails, much like they now do with turbulence, so other planes could adjust their flight paths.

The EU’s aviation authority, EUROCONTROL, starting preparing last year to conduct trials on a contrail avoidance project . Stettler and his colleagues plan to continue research on how to go about implementing changes that could reduce contrails.

“This is the faster way that aviation can reduce its climate impact,” he says.

Related: Stunning views from an airplane window

Harnessing alternative fuels

Commercial airplanes rely on kerosene-based propellant, but companies are experimenting with turning biomasses, such as vegetable oil and even used diapers , into jet fuels. Some research suggests these biofuels could cut carbon pollution from airplanes by upwards of 60 percent . But all biofuels are not created equal.

Those that could be processed into food are unsustainable because of the planet’s growing population, which needs crops for calories. Used cooking oil and pulp leftover from agriculture or logging are expensive and not produced at a scale large enough to make a meaningful difference. But this doesn’t mean that other sustainable aviation fuels won’t be developed.

( How clean is the air on planes? Cleaner than you may think .)