Voice speed

Text translation, source text, translation results, document translation, drag and drop.

Website translation

Enter a URL

Image translation

Home Create an Account Sign-in Wish List Top

01926 499619

• Your Basket £0.00

Delivery • Terms & Conditions

- Forthcoming Titles

- Special Offers

- 21st Century

- Late 20th Century

- Cold War Period

- Second World War

- Inter War Years

- First World War

- Early 20th Century

- 19th Century

- 18th Century

- 17th Century

- 16th Century

- 15th Century

- From Retinue to Regiment 1453-1618

- Century of the Soldier 1618-1721

- From Reason to Revolution 1721-1815

- From Musket to Maxim 1815-1914

- Latin America@War

- Middle East@War

- Technology@War

- Paper Soldiers

- Modern Military Studies

- War & Military Culture in South Asia 1757-1947

- Wolverhampton Military Studies

- Helion Wargames

- Orders & Medals Research Society

- Upcoming Book Launches

- Upcoming Helion Conferences

- Upcoming Trade Shows

- Past Helion Conferences

- Create an Account

- Terms & Conditions

Great Trek (1835-1840)

The Great Trek (Afrikaans: Die Groot Trek; Dutch: De Grote Trek) was an eastward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape’s British colonial administration. The Great Trek resulted from the culmination of tensions between rural descendants of the Cape's original European settlers, known collectively as Boers, and the British Empire. It was also reflective of an increasingly common trend among individual Boer communities to pursue an isolationist and semi-nomadic lifestyle away from the developing administrative complexities in Cape Town. Boers who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as voortrekkers, meaning "pioneers", "pathfinders" (literally "fore-trekkers") in Dutch and Afrikaans.

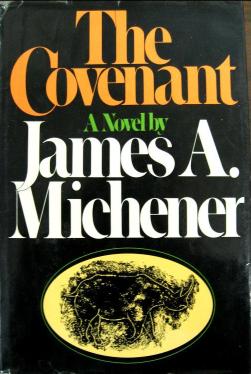

The Great Trek Uncut

Escape from British Rule: The Boer Exodus from the Cape Colony 1836

Robin Binckes

584 pages 30 b/w ills, 30 maps

Paperback £35.00 Including FREE UK delivery

Despatched within 1-2 working days

The Zulu Kingdom and the Boer Invasion of 1837-1840

From Musket to Maxim 1815-1914 #19

John Laband

276 pages 20 b/w ills, 5 b/w photos, 14 colour ills, 4 colour photos, 13 maps

Paperback £29.95 Including FREE UK delivery

Quick Links

Delivery Frequently Asked Questions Downloads inc. Catalogues & Paper Soldiers Trade Information Author Guidelines Terms & Conditions Helion Self Publishing

Helion & Company Unit 8, Amherst Business Centre Budbrooke Road Warwick CV34 5WE

© 2019 - 2024 Helion & Company Limited • Hosted by SWD • Legal Info • Terms of Use • Privacy & Cookies

The Great Trek

The Great Trek ( Afrikaans : Die Groot Trek ; Dutch : De Grote Trek )

- 1 The saga of The Great Trek

- 2 The rebellion of Slagtersnek

- 3 Dingane and Piet Retief

- 4.1 The Day of the Covenant and the Battle of Blood River

- 5 Celebratory events

- 6 Representations of Great Trek personalities, events and history in the performing arts

- 7.1 Plays, tableaus and historical enactments

- 7.4 Sources

- 7.5 Return to

The saga of The Great Trek

This refers specifically to the migration by wagon trains of Dutch -speaking settlers from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards. The main impetus was the increasing tensions between rural descendants of the Cape's original European settlers and the rules imposed by the British government in Cape Colony. The families who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as Voortrekkers , meaning "pioneers", "pathfinders" (literally "fore-trekkers") in Dutch and Afrikaans .

Like the Anglo-Boer War , the (often idealized) saga of The Great Trek would become one of the cornerstones in the construction of an Afrikaner history and identity, and thus a major theme in art, literature and performance. (See the list given below in section ) Of course, research since has not always agreed that all the trekkers (or voortrekkers as they are often known) were as idealistic or innocent as often depicted, for the trek was probably also a good opportunity for those seeking to avaoid the law , to hitch a lift north. Some more recent works have actually sought to redress that matter in various ways.

In many ways this iconization of the event is reminiscent of the similar role played by the great wagon trains heading to the "Wild West" in American history and the psyche of that nation, and as in that case there are also a number of major sub-themes in the broader history of the Trek which have become specific themes of their own in the arts and literature. Some are discussed below.

The rebellion of Slagtersnek

Dingane and piet retief, the day of the covenant and the battle of blood river.

Geloftedag , known in English as The Day of the Covenant or The Day of the Vow , refers to an important event in the history of the Afrikaner people of South Africa, not only celebrated with pageants and performances annually, but the core set of events that surrounding it (such as the rebellion against British rule, the trials and triumphs of the Voortrekkers and The Great Trek [1] , the death of Piet Retief , the covenant itself and the Battle of Blood River ( Afrikaans : Slag van Bloedrivier ; Zulu : iMpi yaseNcome ) ) have been the central theme of numerous historical studies as well as works of art and literature, including many texts written and created for stage, media and film.

Known in Afrikaans as Geloftedag , or The Day of the Vow in English, refers to an important event in the history of the Afrikaner people of South Africa, originating from a oath taken on 16 December 1838 by the Boer leaders of the Great Trek in Natal to honour God in perpetuity if He granted them vistory in the forthcoming Battle of Blood River . As a consequence of the victory, it has been celebrated as a religious public holiday in South Africa from that day onwards.

Initially called Dingaansdag ("Dingane's Day]), 16 December was made an annual public holiday in 1910, before being renamed Geloftedag (the "Day of the Vow") in 1982.

These celebrations gained a particular political significance in the country after the 1938 symbolic re-enactment of the Great Trek of 1838 and the eventual construction and inauguration of the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria (1949).

In 1994, after the end of Apartheid , the name and the intention was changed, it now being called the Day of Reconciliation , an annual holiday also on 16 December, intended to celebrate the dream of final reconciliation between all people in the country.

Celebratory events

Representations of great trek personalities, events and history in the performing arts.

The particular works are simply listed here, click on the name of the particular text to find details on its origins, publication and/or performances.

Di Voortrekkers (1916)

Die Bou van 'n Nasie (" The Building of a Nation ", 1939)

Inspan (1953)

Untamed (1955)

Die Voortrekkers (1973)

The Fiercest Heart (1961)

Plays, tableaus and historical enactments

Piet Retief (Anon., 1904)

Die Pad van Suid-Afrika ( C.J. Langenhoven , 1913)

Die Vooraand van die Trek ( J.R.L. van Bruggen , 1934)

Bakens: Gedramatiseerde mylpale uit die Groot Trek ( J.R.L. van Bruggen , 1938)

Inauguration of the Voortrekker Monument (Anon, 1949)

Voëlvry (Opperman, 1968)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Trek

http://www.voortrekker-history.co.za/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day_of_the_Vow

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day_of_Reconciliation

http://flieksioneel.co.za/filmfeite/van-toeka-tot-nou-films/

Go to ESAT Bibliography

Return to PLAYS I: Original SA plays

Return to PLAYS II: Foreign plays

Return to PLAYS III: Collections

Return to PLAYS IV: Pageants and public performances

Return to South African Festivals and Competitions

Return to The ESAT Entries

Return to Main Page

Navigation menu

Personal tools.

- View source

- View history

- Recent changes

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- This page was last edited on 8 March 2023, at 09:31.

- This page has been accessed 9,064 times.

- Content is available under Public Domain unless otherwise noted.

- Privacy policy

- Disclaimers

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

Great Trek 1835-1846

The Great Trek was a movement of Dutch-speaking colonists up into the interior of southern Africa in search of land where they could establish their own homeland, independent of British rule. The determination and courage of these pioneers has become the single most important element in the folk memory of Afrikaner Nationalism. However, far from being the peaceful and God-fearing process which many would like to believe it was, the Great Trek caused a tremendous upheaval in the interior for at least half a century.

The Voortrekkers

The Great Trek was a landmark in an era of expansionism and bloodshed, of land seizure and labour coercion. Taking the form of a mass migration into the interior of southern Africa, this was a search by dissatisfied Dutch-speaking colonists for a promised land where they would be 'free and independent people' in a 'free and independent state'.

The men, women and children who set out from the eastern frontier towns of Grahamstown, Uitenhage and Graaff-Reinet represented only a fraction of the Dutch-speaking inhabitants of the colony, and yet their determination and courage has become the single most important element in the folk memory of Afrikaner nationalism. However, far from being the peaceful and God-fearing process which many would like to believe it was, the Great Trek caused a tremendous social upheaval in the interior of southern Africa, rupturing the lives of hundreds of thousands of indigenous people. But this time the reports that reached the chiefs of the Sotho clans on the northern bank were more alarming: the white men were coming in their hundreds.

Threatened by the 'liberalism' of the new colonial administration, insecure about conflict on the eastern frontier and 'squeezed out' by their own burgeoning population, the Voortrekkers hoped to restore economic, cultural and political unity independent of British power. The only way they saw open to them was to leave the colony. In the decade following 1835, thousands migrated into the interior, organised in a number of trek parties under various leaders. Many of the Voortrekkers were trekboers (semi-nomadic pastoral farmers) and their mode of life made it relatively easy for them to pack their worldly possessions in ox-wagons and leave the colony forever.

After crossing the Orange River the trekkers were still not totally out of reach of the Cape judiciary - in terms of the Cape of Good Hope Punishment Act (1836), they were liable for all crimes committed south of 25 deg latitude (which falls just below the present-day Warmbaths in northern Transvaal).

The trekkers had a strong Calvinist faith. But when the time came for them to leave they found that no Dutch Reformed Church minister from the Cape was prepared to accompany the expedition, for the church synod opposed the emigration, saying it would lead to 'godlessness and a decline of civilisation'. So the trekkers were forced to rely on the ministrations of the American Daniel Lindley, the Wesleyan missionary James Archbell, and a non-ordained minister, Erasmus Smit.

The trekkers, dressed in traditional dopper coats (short coats buttoned from top to bottom), kappies (bonnets) and hand-made riempieskoene (leather thong shoes), set out in wagons which they called kakebeenwoens (literally, jawbone wagons, because the shape and sides of a typical trek wagon resembled the jawbone of an animal).

These wagons could carry a startling weight of household goods, clothes, bedding, furniture, agricultural implements, fruit trees and weapons. They were ingeniously designed and surprisingly light, so as not to strain the oxen, and to make it easier to negotiate the veld, narrow ravines and steep precipices which lay ahead. Travelling down the 3500 metre slope of the Drakensberg, no brake shoe or changing of wheels could have saved a wagon from hurtling down the mountain were it not for a simple and creative solution: the hindwheels of wagons were removed and heavy branches were tied securely underneath. So the axles were protected, and a new form of brake was invented.

The interior represented for the trekkers a foreboding enigma. The barren Kalahari Desert to the west of the highveld, and the tsetse fly belt which stretched from the Limpopo River south-eastwards, could not have been a very inviting prospect. Little did they realise that neither man nor animal would escape the fatal malarial mosquito. Yet the Voortrekkers ploughed on through treacherous terrain, eliminating all obstacles in their path, and intent on gaining access to ports beyond the sphere of British control, such as Delagoa Bay, Inhambane and Sofala. In order for their new settlement to be viable, it was crucial that they make independent links with the economies of Europe.

Trek and the 'empty lands'

The Empty Land Myth The Empty or Vacant Land Theory is a theory was propagated by European settlers in nineteenth century South Africa to support their claims to land. Today this theory is described as a myth, the Empty Land Myth, because there is no historical or archaeological evidence to support this theory. Despite evidence to the contrary a number of parties in South Africa, particularly right-wing nationalists of European descent, maintain that the theory still holds true in order to support their claims to land-ownership in the country. Read article

Reconnaissance expeditions in 1834 and 1835 reported that Natal south of the Thukela and the central highveld on either side of the Vaal River, were fertile and largely uninhabited, much of the interior having been unsettled by the ravages of the Mfecane (or Difaqane as it is called in Sotho). The truth of these reports - many of them from missionaries - has long been a source of argument among historians, and recent research indicates that the so-called 'depopulation theory' is unreliable - the devastation and carnage by African warriors is exaggerated with every account, the number of Mfecane casualties ranging between half a million and 5-million.

This kind of historical inaccuracy strengthens the trekkers' claim that the land which they occupied was 'uninhabited and belonged to no-one', that the survivors of the Mfecane were conveniently spread out in a horseshoe shape around empty land. Probably in an attempt to justify their land seizure, the trekkers also claimed to have actually saved the smaller clans in the interior from annihilation, and defeated the 'barbarous' Ndebele and Zulu warriors.

Africans did indeed move temporarily into other areas, but were soon to reoccupy their land, only to find themselves ousted by Boer intruders. For example, in Natal the African population, estimated at 11000 in 1838, was increased by 'several thousand refugees' after Dingane's defeat at the hands of his half-brother Mpande two years later. In 1843, when the Republic of Natalia was annexed by the British, the official African population was put at 'between 80 000 and 10 0000 people'. But even this may have been an underestimation.

Trekker communities and technology

Military prowess was of paramount importance to the trekker expedition. It had to be, for they were invading and conquering lands to which African societies themselves lay claim. Bound by a common purpose, the trekkers were a people's army in the true sense of the word, with the whole family being drawn into military defence and attack. For instance, the loading of the sanna (the name they gave to the muzzle-loading rifles they used) was a complicated procedure and so the Boers used more than one gun at a time - while aiming and firing at the enemy with one, their wives and children would be loading another.

Armed with rifles on their backs and a kruithoring (powder horn) and bandolier (a bullet container made of hartebeest, kudu or ox-hide) strapped to their belts, formidable groups of trekkers would ride into battle. Bullets were often sawn nearly through to make them split and fly in different directions, and buckshot was prepared by casting lead into reeds and then chopping it up. Part of every man's gear was his knife, with a blade about 20 centimetres in length. When approaching the battlefield, the wagons would be drawn into a circle and the openings between the wheels filled with branches to fire through and hide behind. When they eventually settled down, the structure of many of the houses they built - square, with thick walls and tiny windows - resembled small fortresses.

The distinction between hunting and raiding parties was often blurred in trekker society. Killing and looting were their business, land and labour their spoils. When the trekkers arrived in the Transvaal they experienced an acute labour shortage. They did not work their own fields themselves and instead used Pedi who sold their labour mainly to buy arms and ammunition.

During commando onslaughts, particularly in the eastern Transvaal, thousands of young children were captured to become inboekselings ('indentured people'). These children were indentured to their masters until adulthood (the age of 21 in the case of women and 25 in the case of men), but many remained bound to their masters for much longer. This system was akin to child slavery, and a more vicious application of the apprenticeship laws promulgated at the Cape in 1775 and 1812.

Child slavery was even more prevalent in the northern Soutpansberg area of the Transvaal. It has been suggested that when these northern Boers could no longer secure white ivory for trade at Delagoa Bay, 'black ivory' (a euphemism widely used for African children) began to replace it as a lucrative item of trade. Children were more amenable to new ways of life, and it was hoped that the inboekselings would assimilate Boer cultural patterns and create a 'buffer class' against increasing African resistance.

Dispossession and land seizure

The trekkers' first major confrontation was with Mzilikazi, founder and king of the Ndebele. After leaving the Cape, the trekkers made their first base near Thaba Nchu, the great place of Moroka, the Rolong chief. In 1836 the Ndebele were in the path of a trekker expedition heading northwards and led by Andries Hendrik Potgieter. The Ndebele were attacked by a Boer commando led by Potgieter, but Mzilikazi retaliated and the Boers retreated to their main laager at Vegkop. There in October, in a short and fierce battle which lasted half an hour, 40 trekkers succeeded in beating off an attack by 6000 Ndebele warriors. Both sides suffered heavy losses - 430 Ndebele were killed, and the trekkers lost thousands of sheep and cattle as well as their trek oxen. But a few days later, Moroka and the missionary Archbell rescued them with food and oxen.

Gert Maritz and his party joined these trekkers in Transorangia (later the Orange Free State) and in January 1837, with the help of a small force of Griqua, Kora, Rolong and Tlokwa, they captured Mzilikazi 's stronghold at Mosega and drove the Ndebele further north. The trekkers then concluded treaties of friendship with Moroka and Sekonyela (chief of the Tlokwa).

When Piet Retief and his followers split away and moved eastwards to Natal, both Potgieter and Piet Uys remained determined to break the Ndebele. At the end of 1837, 135 trekkers besieged Mzilikazi 's forces in the Marico valley, and Mzilikazi fled across the Limpopo River to present-day Zimbabwe. He died there, to be succeeded by Lobengula, who led a rather precarious life in the area until he was eventually defeated by the forces of the British South Africa Company in the 1890s.

Meanwhile, Retief and his followers continued marching towards Port Natal (later Durban). After Retief's fateful encounter with Dingane, chief of the Zulu, and the ensuing Battle of Blood River, the trekkers declared the short-lived Republic of Natalia (1838). They formed a simple system of goveming, with Pretorius as President, assisted by a volksraad (people's assembly) of 24 members, and local government officials based on the traditional landdrost and heemraden system. In 1841, an adjunct council was established at Potchefstroom, with Potgieter as Chief-Commandant. The trekkers believed that at last they had found a place in the sun....

But the British would not recognise their independence. In December 1838, the Governor, Sir George Napier, a determined military man who had not allowed the loss of his right arm in battle to ruin his career, sent his military secretary, Major Samuel Charters, to occupy Port Natal, which effectively controlled Voortrekker use of the harbour. Three years later, when the Natal Volksraad resolved to drive all Africans not working for the whites southwards beyond the Mtamvuna River (later the border between Natal and the Transkei), Napier again intervened. He was concerned that this would threaten the eastern frontier of the Cape, and so instructed Captain Thomas Charlton Smith to march to Port Natal with 250 men. Smith, who had joined the Royal Navy at the age of nine and was a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo, tried to negotiate with Pretorius, but to no avail.

On the moonlit night of 23 May 1842, Smith attacked the Boer camp at Congella but Pretorius, who had been alerted, fought back. The trekkers proceeded to besiege the British camp. One of their number, Dick King. who became known as the 'saviour of Natal', evaded the siege and rode some 1000 kilometres on horseback to seek reinforcements in Grahamstown. In June a British relief force under Lieutenant-Colonel Abraham Cloete arrived on the scene and Boer resistance was crushed. On 15 July the volksraad at Pietermaritzburg signed the conditions of submission.

Although most trekkers had travelled into Natal or into the far north with the main expeditions, some had remained on the fertile land above the junction of the Caledon and Orange rivers, and gradually began to move north-eastward.

The trekkers' pioneer in this area was Jan de Winnaar, who settled in the Matlakeng area in May-June 1838. As more farmers were moving into the area they tried to colonise the land between the two rivers, even north of the Caledon, claiming that it had been abandoned by the Sotho people. But although some of the independent communities who had lived there had been scattered, others remained in the kloofs and on the hillsides. Moshoeshoe, paramount chief of the Sotho, when hearing of the trekker settlement above the junction, stated that '... the ground on which they were belonged to me, but I had no objections to their flocks grazing there until such time as they were able to proceed further; on condition, however, that they remained in peace with my people and recognised my authority'.

The trekkers proceeded to build huts of clay (instead of reed), and began planting their own food crops (no longer trading with the Sotho). This indicated their resolve to settle down permanently. A French missionary, Eugene Casalis, later remarked that the trekkers had humbly asked for temporary rights while they were still few in number, but that when they felt 'strong enough to throw off the mask' they went back on their initial intention.

In October 1842 Jan Mocke, a fiery republican, and his followers erected a beacon at Alleman's drift on the banks of the Orange River and proclaimed a republic. Officials were appointed to preside over the whole area between the Caledon and Vaal rivers. Riding back from the drift, they informed Chief Lephoi, an independent chief at Bethulie, that the land was now Boer property and that he and his people were subject to Boer laws. They further decided that the crops which had been sown for the season would be reaped by the Boers, and they even uprooted one of the peach trees in the garden of a mission station as indication of their ownership. In the north-east, they began to drive Moshoeshoe's people away from the springs, their only source of water. Moshoeshoe appealed for protection to the Queen of England, but he soon discovered that he would have to organise his own resistance.

Land seizure and dispossession were also prevalent in the eastern Transvaal where Potgieter had founded the towns of Andries-Ohrigstad in 1845 and Soutpansberg (which was later renamed Schoemansdal) in 1848. A power struggle erupted between Potgieter and Pretorius, who had arrived with a new trekker party from Natal and seemed to have a better understanding of the political dynamics of southern Africa. Potgieter, still anxious to legitimise his settlement, concluded a vredenstraktaat (peace treaty) in 1845 with Sekwati, chief of the Pedi, who he claimed had ceded all rights to an undefined stretch of land. The precise terms of the treaty are unknown, but it seems certain that Sekwati never actually sold land to the Boers.

Often in order to ensure their own safety, chiefs would sign arbitrary treaties giving away sections of land to which they in fact had no right. Such was the case with Mswati, chief of the Swazi, who, intent on seeking support against the Zulu, in July 1846 granted all the land bounded by the Oliphants, Crocodile and Elands rivers to the Boers. This angered the Pedi, who pointed out that the land had not even been his to hand over.

There was no uniform legal system or concept of ownership to which all parties interested in the land subscribed. Private land ownership did not exist in these African societies, and for the most part the land which chiefs ceded to the Boers was communally owned. Any document 'signed' by the chiefs, and its implications, could not have been fully understood by them. Misunderstandings worked in the favour of the Boers.

Large tracts of land were purchased for next to nothing. For example, the northern half of Transorangia went to Andries Potgieter in early 1836 for a few cattle and a promise to protect the Taung chief, Makwana, from the Ndebele. The area between the Vet and Vaal rivers extended about 60 000 square kilometres. This means that Potgieter got 2000 square kilometres per head of livestock! Also the 'right of conquest' was extended over areas much larger than those that chiefs actually had authority over. After Mzilikazi 's flight north in November 1837, the trekkers immediately took over all the land between the Vet and Limpopo rivers - although Mzilikazi's area of control covered only the western Transvaal.

But it was only after the Sand River Convention (1852) and the Bloemfontein Convention (1854) that independent Boer republics were formally established north of the Vaal and Orange rivers respectively.

Reader’s Digest. (1988). Illustrated History of South Africa: the real story, New York: Reader’s Digest Association. p. 114-120.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Services on Demand

Related links, tydskrif vir geesteswetenskappe, on-line version issn 2224-7912 print version issn 0041-4751, tydskr. geesteswet. vol.49 n.4 pretoria 2009.

Was die Groot Trek werklik groot? 'n Historiografiese ondersoek na die gevolge en betekenis van die Groot Trek

Was the Great Trek really great? A historiographical inquiry into the consequences and significance of the Great Trek

Pieter de Klerk

Vakgroep Geskiedenis, Noordwes-Universiteit (Vaaldriehoekkampus), E-pos: [email protected]

Sedert die laat negentiende eeu het historici die gevolge en betekenis van die Groot Trek bespreek. Daar kan verskillende hooftendense in die interpretasies onderskei word. Daar is eerstens die vroeë beskouing dat die Trek die beskawing in suidelike Afrika uitgedra het. Tweedens is daar die siening van Afrikaanse historici dat die Groot Trek die totstandkoming van die Afrikanervolk moontlik gemaak het. Derdens het lede van die liberale skool van historici die Trek beskou as 'n ontvlugting van progressiewe Britse beleidsmaatreëls in die Kaapkolonie; dit was 'n ramp vir die ontwikkeling van Suid-Afrika. Vierdens is daar die siening van die radikale skool dat die Groot Trek 'n fase was in die uitbreiding van kapitalisme en kolonialisme in Suid-Afrika. Vyfdens is daar die resente opvatting dat die Groot Trek net een van verskeie migrasies in Suid-Afrika was en nie uitgesonder kan word as van besondere betekenis nie. Sesdens beskou latere Afrikaanse geskiedskrywers die Trek as 'n gebeurtenis met uiteenlopende gevolge. Dit blyk dat historici steeds beïnvloed is deur tydsomstandighede in hul beklemtoning van bepaalde gevolge van die Trek. Sommige van hul stellings oor die langtermyngevolge van die Trek is spekulatief en kan moeilik gestubstansieer word. Gesien binne die perspektief van die huidige tydsgewrig was die Groot Trek primer deel van 'n omvattende proses van verwestering en modernisasie in suidelike Afrika. Alhoewel dit nie as dié sentrale gebeurtenis in die geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika gesien kan word, soos vroeër dikwels beweer is nie, is dit tog een van 'n klein aantal sleutelgebeurtenisse in die geskiedenis van die land.

Trefwoorde: Groot Trek, Voortrekkers, Suid-Afrikaanse geskiedenis, historiografie, Afrikanernasionalisme, Afrikanasionalisme, liberale historici, radikale historici, kolonisasie, kapitalisme, rassebeleid.

Since the late nineteenth century historians have discussed the consequences and significance of the Great Trek. G M Theal, who wrote an authoritative multi-volume history of South Africa, described the Trek as a unique event in the history of modern colonisation. He, together with scholars such as G E Cory and M Nathan, saw the importance of the Great Trek especially in terms of the expansion of Western civilisation and Christianity into the eastern parts of South Africa. During the period between approximately 1900 and 1980 many Afrikaans- speaking historians were strongly influenced by Afrikaner nationalism. They linked the Great Trek to the birth of the Afrikaner nation. Some historians, such as G S Preller and C Beyers, saw the Voortrekkers as people who were already conscious of their identity as a nation and wanted to become free of British dominance. Later historians, such as G D Scholtz, C F J Muller and F A van Jaarsveld, believed that Afrikaner nationalism only developed after the Great Trek, but that the Trek prevented the anglicization of the Boers in the Cape Colony and therefore made possible the development of an Afrikaner nation. W M Macmillan, E A Walker and C W de Kiewiet, three prominent members of the liberal school of historians, also regarded the Great Trek as a very important event in the development of South Africa, but thought that it had mainly negative consequences. In their opinion, the Voortrekkers had escaped from the economic and political changes in the Cape Colony with the aim of preserving an antiquated way of life. In the Boer republics, and later in the Union of South Africa, the racial policies of the Dutch colonial period were continued, instead of the liberal racial policies practised in the Cape Colony under British rule. Some contemporary historians still accept major elements of the early liberal interpretations. Authors with a Marxist viewpoint, such as D Taylor and W M Tsotsi, also regarded the Voortrekkers as representatives of a pre-capitalist economic system, but at the same time saw them as the vanguard of the imperialist advance in Africa; the Voortrekkers were conquerers and the oppressors of the indigenous population. P Delius, T Keegan and others, however, viewed the Voortrekkers as being part of the expanding capitalist system in Southern Africa. Since the 1960s a number of historians argued that the Great Trek should not be seen as a central event in the development of South Africa. A R Willcox and N Parsons emphasized the similarities between the Great Trek and the Mfecane. N Etherington, who is critical of traditional views of the Mfecane as a dispersal of peoples in Southern Africa caused by the rise of the Zulu kingdom under Shaka, viewed the Great Trek as one of a number of "treks" by various groups during the period 1815-1854. According to him the Great Trek was not larger or more significant than the other migrations and therefore does not deserve to be called "great". During the last four decades several Afrikaans historians pointed out that the Great Trek had a number of diverse consequences. From the perspective of the history of the Afrikaners there were various negative consequences. As a result of the Trek, the Afrikaners remained politically divided for many years. Furthermore, the Trek resulted in the cultural and economic isolation of the Boers. The Great Trek increased the conflicts between the Boers and indigenous tribes, but, on the other hand, stimulated trade between black and white groups. It would appear that in their various interpretations of the consequences of the Great Trek historians were influenced by the circumstances of their own time. Consequences which during a certain period seemed very important are now no longer regarded as particularly significant. De Kiewiet, for instance, pointed out in 1941 that the Great Trek connected the future development of the whole of South Africa with the Afrikaners, but today the Afrikaners are no longer the politically dominant group. Interpretations of the signifance of the Great Trek have also been strongly influenced by philosophical and ideological views. Afrikaner nationalists, African nationalists, Marxists and liberal historians have emphasized different consequences. While the view of the liberal school that the Great Trek caused the continuation of non-liberal racial policies had been influential for a long time, it was challenged by later scholars who regarded racism and apartheid as products of capitalism and colonialism. Some statements on the long term consequences of the Great Trek are speculative and cannot be proved or disproved. Among these are the proposition of several Afrikaner historians that the descendants of the Voortrekkers would have been completely anglicized if they had remained in the Cape Colony; and the statement by De Kiewiet that the Great Trek had prevented the development of separate white and black states in Southern Africa. The Great Trek was an important phase in the Western colonisation of South Africa. Early historians such as Theal saw the colonisation process as a positive development. For African nationalist writers, however, colonisation meant primarily the oppression of the indigenous peoples. Political decolonisation did not bring an end to the process of westernisation and modernisation in Africa, and the dominant political and economic system in South Africa today is mainly of Western origin. The Great Trek was a key event in the history of South Africa, comparable with events such as the British conquest of the Cape Colony in 1806 and the transfer of political power to the black majority in 1994.

Key concepts: Great Trek, Voortrekkers, South African history, historiography, Afrikaner nationalism, African nationalism, liberal historians, radical historians, colonisation, capitalism, racial policy

Full text available only in PDF format.

BIBLIOGRAFIE

Ajayi, J.F.A. (ed). 1989. Africa in the nineteenth century, until the 1880s. Paris: Unesco. (General History of Africa, volume 6. [ Links ] )

Benyon, J. 1988. The necessity for new perspectives in South African historiography with particular reference to the Great Trek. Historia, 33(2):1-10. [ Links ]

Beyers, C. 1941. Die Groot Trek met betrekking tot ons nasiegroei. Argiefjaarboek vir Suid-Afrikaanse geskiedenis, 4(1):1-16. [ Links ]

Bundy, C. 1986. Vagabond Hollanders and runaway Englishmen: white poverty in the Cape before poor whiteism. In W. Beinart, P. Delius & S. Trapido (eds). Putting a plough to the ground; accumulation and dispossession in rural South Africa, 1850-1930. Johannesburg: Ravan. [ Links ]

Bundy, C. 2007. New nation, new history? Constructing the past in post-apartheid South Africa. In H.E. Stolten (ed). History making and present day politics; the meaning of collective memory in South Africa. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. [ Links ]

Cana, F. 1909. South Africa, from the Great Trek to the Union. London: Chapman & Hall. [ Links ]

Carruthers, J. 2002. Book review of N. Etherington, The Great Treks. Kleio, 34:167-170. [ Links ]

Cory, G.E. 1919. The rise of South Africa; a history of the origin of South African colonisation and of its development towards the east from the earliest times to 1857, volume 3. London: Longmans & Green. [ Links ]

Cory, G.E. 1926. The rise of South Africa; a history of the origin of South African colonisation and of its development towards the east from the earliest times to 1857, volume 4. London: Longmans & Green. [ Links ]

Davenport, T.R.H. & Saunders, C. 2000. South Africa; a modern history. London: Macmillan. (Fifth edition. [ Links ] )

De Kiewiet, C.W. 1941. A history of South Africa, social and economic. Oxford: University Press. [ Links ]

De Klerk, P. 2008. F.A. van Jaarsveld se Die ontwaking van die Afrikaanse nasionale bewussyn na vyftig jaar. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe, 48(3):338-356. [ Links ]

Delius, P. 1983. The Pedipolity, the Boers and the British in the nineteenth-century Transvaal. Johannesburg: Ravan. [ Links ]

Denoon, D. & Nyeko, B. 1984. Southern Africa since 1800. London: Longman. (Revised edition. [ Links ] )

Du Bruyn, J.T. 1986. Die Groot Trek. In T. Cameron & S.B. Spies (reds.). Nuwe geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika in woord en beeld. Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau. [ Links ]

Du Bruyn, J.T. 1997. Early Transvaal - a historiographical perspective. Suid-Afrikaanse Historiese Joernaal, 36:136-144. [ Links ]

Elphick, R. & Giliomee, H. 1989. The origins and entrenchment of European dominance at the Cape, 1652-c.1840. In R. Elphick & H. Giliomee (eds). The shaping of South African society, 1652-1840. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Etherington, N. 1991. The Great Trek in relation to the Mfecane: a reassessment. Suid-Afrikaanse Historiese Joernaal, 25:3-21. [ Links ]

Etherington, N. 2001. The Great Treks; the transformation of South Africa, 1815-1854. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Etherington, N. 2002. Reviewing "the evidence" for the Great Treks. South African Historical Journal, 47:191-202. [ Links ]

Etherington, N. 2008. Is a reorientation of South African history a lost cause? South African Historical Journal, 60(3):323-333. [ Links ]

Fredrickson, G.M. 1981. White supremacy; a comparative study in American and South African history. Oxford: University Press. [ Links ]

Freund, B. 1998. The making of contemporary Africa; the development of African society since 1800. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. (Second edition. [ Links ] )

Gebhard, W.R.L. 1988. Changing black perceptions of the Great Trek. Historia, 33(2):38-50. [ Links ]

Gie, S.F.N. 1939. Geskiedenis vir Suid-Afrika of ons verlede, deel 2, 1795-1918. Stellenbosch: Pro Ecclesia. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H. 1981. Processes in development of the Southern African frontier. In H. Lamar & L.M. Thompson (eds). The frontier in history; North America and Southern Africa compared. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H. 2003. The Afrikaners; biography of a people. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H. & Mbenga, B. (reds.). 2007. Nuwe geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika. Kaapstad: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Hamilton, C. 1995. Introduction. In C. Hamilton (ed). The Mfecane aftermath; reconstructive debates in Southern African history. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. [ Links ]

July, R.W. 1998. A history of the African people. Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press. (Fifth edition). [ Links ]

Keegan, T. 1988. Rural transformations in industrializing South Africa; the southern Highveld to 1914. Johannesburg: Ravan. [ Links ]

Keegan, T. 1996. Colonial South Africa and the origins of the racial order. Cape Town: Philip. [ Links ]

Lester, A. 2002. Redrawing cartographies of power. Journal of Southern African Studies, 28(3):651-653. [ Links ]

Macmillan, W.M. 1927. The Cape colour question; a historical survey. London: Faber & Gwyer. [ Links ]

Macmillan, W.M. 1963. Bantu, Boer and Briton; the making of the South African native problem. Oxford: Clarendon. (Revised edition; first edition 1928). [ Links ]

Magubane, B.M. 1979. The political economy of race and class in South Africa. New York: Monthly Review Press. [ Links ]

Majeke (pseudonym of D.Taylor). 1952. The rôle of the missionaries in conquest. Johannesburg: Society of Young Africa. [ Links ]

Malan, J.H. 1913. Boer en barbaar of die lotgevalle van die Voortrekkers, viral tussen die jare 1835 en 1840. Potchefstroom: Unie Lees- en Studiebibliotheek. [ Links ]

Maylam, P. 2001. South Africa's racial past; the history and historiography of racism, segregation and apartheid. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Muller, C.F.J. 1963. Die Groot Trek. In F.A. van Jaarsveld et al. Die hervertolking van ons geskiedenis. Pretoria: Universiteit van Suid-Afrika. [ Links ]

Muller, C.F.J. 1974. Die oorsprong van die Groot Trek. Kaapstad: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Muller, C.F.J. 1980. Die Groot Trek-tydperk, 1834-1854. In C.F.J. Muller (red.). Vyfhonderd jaar Suid-Afrikaanse geskiedenis. Pretoria: Academica. (Derde uitgawe). [ Links ]

Nathan, M. 1937. The Voortrekkers of South Africa; from the earliest times to the foundation of the republics. London: Gordon & Gotch. [ Links ]

Omer-Cooper, J.D. 1966. The Zulu aftermath; a nineteenth-century revolution in Bantu Africa. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Omer-Cooper, J.D. 1995. The Mfecane survives its critics. In C. Hamilton (ed). The Mfecane aftermath; reconstructive debates in Southern African history. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. [ Links ]

Parsons, N. 1993. A new history of Southern Africa. London: Macmillan. (Second edition). [ Links ]

Parsons, N. 2002. Reviving the Treks debates. South African Historical Journal, 46: 308-312. [ Links ]

Peires, J.B. 1989. The British and the Cape, 1814-1834. In R. Elphick & H. Giliomee (eds). The shaping of South African society, 1652-1840. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Preller, G.S. 1920. Piet Retief; lewensgeskiedenis van die grote Voortrekker. Kaapstad: Nationale Pers. (Tiende uitgawe). [ Links ]

Reader's Digest (publisher). 1988. Reader's Digest illustrated history of South Africa; the real story. Cape Town: Reader's Digest. [ Links ]

Saunders, C. 1988. The making of the South African past; major historians on race and class. Cape Town: Philip. [ Links ]

Saunders, C. 2002. Great Treks? South African Historical Journal, 46:300-307. [ Links ]

Scholtz, G.D. 1970. Die ontwikkeling van die politieke denke van die Afrikaner, deel 2, 1806-1854. Johannesburg: Voortrekkerpers. [ Links ]

Smith, K. 1988. The changing past; trends in South African historical writing. Johannesburg: Southern. [ Links ]

Theal, G.M. 1887. History of the Boers in South Africa or the wanderings and wars of the emigrant farmers from their leaving of the Cape Colony to the acknowledgement of their independence by Great Britain. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Lowrey. [ Links ]

Theal, G.M. 1902. Progress of South Africa in the century. Toronto: Linscott. [ Links ]

Theal, G.M. 1918-1919. History of South Africa. London: Allen & Unwin. (Fourth edition, 11 volumes). [ Links ]

Thompson, L.M. 1985. The political mythology of apartheid. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Thompson, L.M. 1995. Southern Africa, 1795-1870. In P. Curtin et al. African history; from earliest times to independence. London: Longman. (Second edition). [ Links ]

Tsotsi, W.M. 1981. From chattel to wage slavery; a new approach to South African history. Maseru: Lesotho Printing and Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Van Aswegen, H.J. 1989. Geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika tot 1854. Pretoria: Academica. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, A.J.H. 1951. Die Groot Trek tot 1838. In A.J.H. van der Walt, J.A. Wiid & A.L. Geyer (reds.). Geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika, deel 1. Kaapstad: Nasionale Boekhandel. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, A.J.H. 1964. Die Groot Trek tot 1838. In A.J.H. van der Walt, J.A. Wiid, A.L. Geyer & D.W. Krüger (reds.). Geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika. Kaapstad: Nasou. (Tweede uitgawe). [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1951. Die eenheidstrewe van die republikeinse Afrikaners, deel 1, Pioniershartstogte (1836-1864). Johannesburg: Voortrekkerpers. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1957. Die ontwaking van die Afrikaanse nasionale bewussyn, 1868-1881. Johannesburg: Voortrekkerpers. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1961. Lewende verlede. Johannesburg: Afrikaanse Pers- Boekhandel. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1962. Die tydgenootlike beoordeling van die Groot Trek, 1836-1842. Pretoria: Universiteit van Suid-Afrika. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1963. Die beeld van die Groot Trek in die Suid-Afrikaanse geskiedskrywing, 1843-1899. Pretoria: Universiteit van Suid-Afrika. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1974. Geskiedkundige verkenninge. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1982. Van Van Riebeeck totP.W. Botha; 'n Inleiding tot die geskiedenis van die Republiek van Suid-Afrika. Johannesburg: Perskor. (Derde uitgawe). [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1984. Omstrede Suid-Afrikaanse verlede; geskiedenisideologie en die historiese skuldvraagstuk. Johannesburg: Lex Patria. [ Links ]

Van Jaarsveld, F.A. 1992. Afrikanergeskiedskrywing; verlede, hede en toekoms. Johannesburg: Lex Patria. [ Links ]

Venter, C. 1985. Die Groot Trek. Kaapstad: Don Nelson. [ Links ]

Visagie, J.C. 2005. Etherington oor die Afrikaner en die Groot Trek. Historia, 50(1):1-21. [ Links ]

Voigt, J.C. 1899a. Fifty years of the history of the republic in South Africa (1795-1845), volume 1. London: Fisher Unwin. [ Links ]

Voigt, J.C. 1899b. Fifty years of the history of the republic in South Africa (1795-1845), volume 2. London: Fisher Unwin. [ Links ]

Walker, E.A. 1930. The frontier tradition in South Africa. London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Walker, E.A. 1965. The Great Trek. London: Adam & Charles Black. (Fifth edtion; first edition 1934). [ Links ]

Willcox, A.R. 1976. Southern land; the prehistory and history of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Purnell. [ Links ]

Wilson, M. & Thompson, L.M. (eds). 1969-1970. The Oxford history of South Africa. Oxford: University Press. (2 volumes). [ Links ]

1 Vergelyk Etherington (2008:323-324, 332). 2 Vergelyk Saunders (1988:9); Smith (1988:31). 3 Vergelyk Theal (1887:357); Van Jaarsveld (1963:52). 4 Vergelyk Muller (1963:54-55); Van Jaarsveld (1974:55); Smith (1988:47-48). 5 Vergelyk Muller (1963:53-54); Thompson (1985:180); Van Jaarsveld (1992: 28). 6 Majeke, Introduction, ongenommerd; vgl. Van Jaarsveld (1974:101); Muller (1974:37); Saunders (1988:137). 7 Vergelyk Van Jaarsveld (1984:58-65); Saunders (1988:154-161); Smith (1988:139-144). 8 Vergelyk die kritiek van Saunders (2002:300-307). 9 Vergelyk ook Muller (1974:20-21; Visagie (2005:2).

Pieter de Klerk is professor in Geskiedenis aan die Vaaldriehoekkampus van die Noordwes-Universiteit. Hy het aan die Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir CHO (tans bekend as die Noordwes-Universiteit) en aan die Vrije Universiteit van Amsterdam gestudeer, voordat hy in 1971 die graad D.Litt. in Geskiedenis aan eersgenoemde inrigting verwerf het. Hy is in 1968 as junior lektor in Geskiedenis op die Potchefstroomkampus van die PU vir CHO aangestel en is sedert 1983 aan die Vaaldriehoekkampus verbonde. Hy is die outeur van 'n aantal boeke en artikels op, hoofsaaklik, die volgende terreine: die teorie en filosofie van geskiedenis, historiografie en vergelykende geskiedenis. Hy het verskeie voordragte op internasionale en binnelandse vakkonferensies gelewer en was redaksielid van enkele akademiese tydskrifte.

Pieter de Klerk is professor of History at the Vaal Triangle Campus of North-West University. He studied at the Potchefstroom University for CHE (presently called Northwest-University) and at the Free University of Amsterdam, before he obtained the degree D.Litt. in History in 1971 at Potchefstroom University. In 1968 he was appointed as junior lecturer in History at the Potchefstroom Campus of the PU for CHE, and since 1983 he has been a staff-member at the Vaal Triangle Campus. He is the author of a number of books and articles focusing largely on the following fields of expertise: the theory and philosophy of history, historiography and comparative history. He has presented several papers at international and national academic conferences and has served on the editorial boards of a number of scholarly journals.

About: Great Trek

The Great Trek (Afrikaans: Die Groot Trek; Dutch: De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial administration. The Great Trek resulted from the culmination of tensions between rural descendants of the Cape's original European settlers, known collectively as Boers, and the British Empire. It was also reflective of an increasingly common trend among individual Boer communities to pursue an isolationist and semi-nomadic lifestyle away from the developing administrative complexities in Cape Town. Boers who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as voortrekkers, meaning "pioneers", "pathfinders" (liter

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

Vocabulary

What does great trek mean?

Definitions for great trek great trek, this dictionary definitions page includes all the possible meanings, example usage and translations of the word great trek ., did you actually mean gritrock or geriatrics , wikipedia rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes.

The Great Trek (Afrikaans: Die Groot Trek; Dutch: De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial administration. The Great Trek resulted from the culmination of tensions between rural descendants of the Cape's original European settlers, known collectively as Boers, and the British Empire. It was also reflective of an increasingly common trend among individual Boer communities to pursue an isolationist and semi-nomadic lifestyle away from the developing administrative complexities in Cape Town. Boers who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as voortrekkers, meaning "pioneers", "pathfinders" (literally "fore-trekkers") in Dutch and Afrikaans. The Great Trek led directly to the founding of several autonomous Boer republics, namely the South African Republic (also known simply as the Transvaal), the Orange Free State, and the Natalia Republic. It also led to conflicts that resulted in the displacement of the Northern Ndebele people, and conflicts with the Zulu people that contributed to the decline and eventual collapse of the Zulu Kingdom.

Wikidata Rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes

The Great Trek was an eastward and north-eastward migration away from British control in the Cape Colony during the 1830s and 1840s by Boers. The migrants were descended from settlers from western mainland Europe, most notably from the Netherlands, northwest Germany and French Huguenots. The Great Trek itself led to the founding of numerous Boer republics, the Natalia Republic, the Orange Free State Republic and the Transvaal being the most notable.

How to pronounce great trek?

Alex US English David US English Mark US English Daniel British Libby British Mia British Karen Australian Hayley Australian Natasha Australian Veena Indian Priya Indian Neerja Indian Zira US English Oliver British Wendy British Fred US English Tessa South African

How to say great trek in sign language?

Chaldean Numerology

The numerical value of great trek in Chaldean Numerology is: 1

Pythagorean Numerology

The numerical value of great trek in Pythagorean Numerology is: 6

- ^ Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Trek

- ^ Wikidata https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?search=great trek

Word of the Day

Would you like us to send you a free new word definition delivered to your inbox daily.

Please enter your email address:

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:.

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"great trek." Definitions.net. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 9 Apr. 2024. < https://www.definitions.net/definition/great+trek >.

Discuss these great trek definitions with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Are we missing a good definition for great trek ? Don't keep it to yourself...

Image credit, the web's largest resource for, definitions & translations, a member of the stands4 network, image or illustration of.

Free, no signup required :

Add to chrome, add to firefox, browse definitions.net, are you a words master, come up with (an idea, plan, explanation, theory, or principle) after a mental effort, Nearby & related entries:.

- great things

- great tinamou

- great titchfield street

- great toe noun

- great tribulation

- great turnstile

- great unconformity

- great unknown, the

Alternative searches for great trek :

- Search for great trek on Amazon

Words and phrases

Personal account.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

† grote verb

- Hide all quotations

What does the verb grote mean?

There is one meaning in OED's entry for the verb grote . See ‘Meaning & use’ for definition, usage, and quotation evidence.

This word is now obsolete. It is only recorded in the Middle English period (1150—1500).

Entry status

OED is undergoing a continuous programme of revision to modernize and improve definitions. This entry has not yet been fully revised.

Where does the verb grote come from?

Earliest known use

Middle English

The only known use of the verb grote is in the Middle English period (1150—1500).

OED's earliest evidence for grote is from around 1300, in Havelok .

grote is a borrowing from early Scandinavian.

Etymons: Norse gráta .

Nearby entries

- grossy, adj. 1648–

- grost, n. a1500

- grosté, n. a1475

- Gros Ventre, n. & adj. 1804–

- grot, n.¹ Old English–1425

- grot, n.² a1325–1400

- grot, n.³ 1511–

- grot, n.⁴ & adj.¹ 1961–

- grot, n.⁵ 1970–

- grot, adj.² 1967–

- grote, v. c1300–25

- groten, v. c1440

- grotes, n. c1450

- grotesque, n. & adj. 1561–

- grotesque, v. 1875–

- grotesquely, adv. 1740–

- grotesqueness, n. 1826–

- grotesquerie, n. 1655–

- grothite, n. 1867–

- Grotian, adj. & n. 1864–

- Grotianism, n. 1920–

Thank you for visiting Oxford English Dictionary

To continue reading, please sign in below or purchase a subscription. After purchasing, please sign in below to access the content.

Meaning & use

Entry history for grote, v..

grote, v. was first published in 1900; not yet revised.

grote, v. was last modified in July 2023.

Revision of the OED is a long-term project. Entries in oed.com which have not been revised may include:

- corrections and revisions to definitions, pronunciation, etymology, headwords, variant spellings, quotations, and dates;

- new senses, phrases, and quotations which have been added in subsequent print and online updates.

Revisions and additions of this kind were last incorporated into grote, v. in July 2023.

Earlier versions of this entry were published in:

OED First Edition (1900)

- Find out more

OED Second Edition (1989)

- View grote, v. in OED Second Edition

Please submit your feedback for grote, v.

Please include your email address if you are happy to be contacted about your feedback. OUP will not use this email address for any other purpose.

Citation details

Factsheet for grote, v., browse entry.

- Pronunciation

- Try to pronounce

- Collections

Learn how to pronounce Grote Trek

- Very difficult

Have you finished your recording?

Quiz on Grote Trek

{{ quiz.name }}

{{ quiz.questions_count }} Questions

Show more fewer Quiz

Collections on Grote Trek

-{{collection.uname}}

Show more fewer Collections

Popular collections

World leaders, manchester united players list 2020, pandemics before covid 19, bayern munich squad / player list 2020-21, popular quizzes.

Trending on HowToPronounce

- Ellen van Dijk [nl]

- Gaby Blaaser [nl]

- zwevegem [nl]

- Sint Jansklooster [nl]

- Anita Doth [nl]

- Feyenoord [nl]

- Calvin Verdonk [nl]

- Wesley Sonck [nl]

- Danira Boukhriss [nl]

- Famke Louise [nl]

- Harry Dikmans [nl]

- Rob de Nijs [nl]

- spinvis [nl]

- Tim van Dijke [nl]

Add Grote Trek details

Thanks for contributing

You are not logged in..

Please Log in or Register or post as a guest

Grote Trek should be in sentence

Grote Trek in dutch pronunciations with meanings, synonyms, antonyms, translations, sentences and more.

Which is the right way to pronounce the word plagiarize, word of the day, latest word submissions, recently viewed words, flag word/pronunciation, create a quiz.

Why ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Built Season 5 Around a Classic Episode From a Legacy Series

By Adam B. Vary

Adam B. Vary

Senior Entertainment Writer

- Why ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Built Season 5 Around a Classic Episode From a Legacy Series 5 days ago

- ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Star Sonequa Martin-Green on the Show’s Unexpected Final Season, the ‘Pressure’ of Representation and Taking the ‘Trek’ Cruise 6 days ago

- Jerrod Carmichael Was Terrified of Being Seen, So He Made a Reality Show: ‘This May Be Unhealthy. It Is a Little Dangerous’ 2 weeks ago

SPOILER ALERT: This story discusses major plot developments in Season 5, Episode 1 of “ Star Trek : Discovery,” now streaming on Paramount+.

By the end of the episode, however, the mission has pushed Burnham and her crew to their limits, including slamming the USS Discovery into the path of a massive landslide threatening a nearby city. Before they risk their lives any further pursuing this object, Burnham demands that Kovich at least tell her why. (MAJOR SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

Kovich’s explanation evokes the classic “ Star Trek: The Next Generation ” episode “The Chase” from 1993 in which Capt. Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart) — along with teams of Romulans, Klingons and Cardassians — learn that all humanoid life in the galaxy was created by a single species that existed billions of years earlier, and seeded thousands of planets with the DNA to pass along their legacy. (Along with presenting a profound vision of the origins of life, the episode also provided an imaginative explanation for why almost all the aliens in “Star Trek” basically look like humans with different kinds of forehead ridges.)

Kovich tells Burnham that the Romulan scientist was part of a team sent to discover exactly how these aliens — whom they call the Progenitors — made this happen; the object they’re seeking winds up being one part of a brand new “chase,” this time in the 32nd century, to find the Progenitors’ technology before it can fall into the wrong hands.

“I remember watching that episode and at the end of it just being blown away that there was this huge idea where we all come from,” Paradise says. “And then they’re going to have another mission the next week. I found myself wondering, ‘Well, then what? What happened? What do we do with this information? What does it mean?’”

Originally, Paradise says the “Discovery” writers’ room discussed evoking the Progenitors in Season 4, when the Discovery meets an alien species, the 10-C, who live outside of the galaxy and are as radically different from humans as one could imagine. “As we dug deeper into the season itself, we realized that it was too much to try and get in,” Paradise says.

Instead, they made the Progenitors the engine for Season 5. “Burnham and some of our other characters are on this quest for personal meaning,” Paradise says. Searching for the origins of life itself, she adds, “feels like a big thematic idea that fits right in with what we’re exploring over the course of the season, and what our characters are going through.”

That meant that Paradise finally got to help come up with the answers to the questions about “The Chase” that had preoccupied her when she was younger. “We had a lot of fun talking about what might’ve happened when [Picard] called back to headquarters and had to say, ‘Here’s what happened today,’” she says. “We just built the story out from there.”

More From Our Brands

‘the challenge: all stars’ showrunner peels back the curtain on new season, review: meze audio’s newest headphones deliver premium sound and plush comfort, uconn hoops spending pays off with second straight ncaa title, the best loofahs and body scrubbers, according to dermatologists, tulsa king casting agency quits after stallone allegedly disparages background actors, verify it's you, please log in.

To support our work, we invite you to accept cookies or to subscribe.

You have chosen not to accept cookies when visiting our site.

The content available on our site is the result of the daily efforts of our editors. They all work towards a single goal: to provide you with rich, high-quality content. All this is possible thanks to the income generated by advertising and subscriptions.

By giving your consent or subscribing, you are supporting the work of our editorial team and ensuring the long-term future of our site.

If you already have purchased a subscription, please log in

What is the translation of "trek" in English?

"trek" in english.

- volume_up appetite

trek- {adj.}

- volume_up migratory

trekken {vb}

- volume_up draw

- make a draft

- make a stroke

- wander about

aandacht trekken {vb}

- volume_up attract attention

grenzen trekken {vb}

- volume_up draw lines

"trek" in Dutch

- volume_up tocht

Translations

- open_in_new Link to source

- warning Request revision

trek- {adjective}

Trekken [ trok|getrokken ] {verb}, aandacht trekken {verb}, grenzen trekken {verb}, trek {noun}, context sentences, dutch english contextual examples of "trek" in english.

These sentences come from external sources and may not be accurate. bab.la is not responsible for their content.

Monolingual examples

Dutch how to use "migratory" in a sentence, dutch how to use "attract attention" in a sentence, dutch how to use "draw lines" in a sentence.

- treinkaartje

- treinmachinist

- treinsurfen

- treintunnel

- treinvervoer

- trek hebben in

- trek hebben in iets

- trekharmonika

Even more translations in the Russian-English dictionary by bab.la.

Social Login

- 1.2 Anagrams

- 2.1 Pronunciation

- 2.2 Adjective

- 3.1 Pronunciation

- 3.2 Adjective

- 3.3 Anagrams

- 4.1.1.1 Inflection

- 4.1.1.2 Descendants

- 4.2.1 Adjective

- 4.3 Further reading

- 5.1 Pronunciation

English [ edit ]

Noun [ edit ].

grote ( plural grotes )

- Obsolete spelling of groat

Anagrams [ edit ]

- Roget , Trego , ergot , etrog , regot

Afrikaans [ edit ]

Pronunciation [ edit ], adjective [ edit ].

- attributive form of groot

Dutch [ edit ]

- IPA ( key ) : /ˈɣroːtə/

- Homophone : grootte

- masculine / feminine singular attributive

- definite neuter singular attributive

- plural attributive

Middle Dutch [ edit ]

Etymology 1 [ edit ].

From grôot + -e .

grôte f

Inflection [ edit ]

This noun needs an inflection-table template .

Descendants [ edit ]

Etymology 2 [ edit ].

See the etymology of the corresponding lemma form.

- masculine nominative singular

- feminine / neuter nominative / accusative singular

- nominative / accusative plural

Further reading [ edit ]

- “ grote (I) ”, in Vroegmiddelnederlands Woordenboek , 2000

- Verwijs, E. ; Verdam, J. (1885–1929), “ grote (II) ”, in Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek , The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, →ISBN , page II

Romanian [ edit ]

- IPA ( key ) : [ˈɡrote]

grote f pl

- indefinite plural

- indefinite genitive / dative singular

- English lemmas

- English nouns

- English countable nouns

- English obsolete forms

- Afrikaans terms with audio links

- Afrikaans non-lemma forms

- Afrikaans adjective forms

- Dutch terms with IPA pronunciation

- Dutch terms with audio links

- Dutch terms with homophones

- Dutch non-lemma forms

- Dutch adjective forms

- Middle Dutch terms suffixed with -e

- Middle Dutch lemmas

- Middle Dutch nouns

- Middle Dutch feminine nouns

- Middle Dutch non-lemma forms

- Middle Dutch adjective forms

- Romanian terms with IPA pronunciation

- Romanian non-lemma forms

- Romanian noun forms

- Requests for inflections in Middle Dutch noun entries

- Requests for inflections in Middle Dutch entries

Navigation menu

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

George, 1794–1871, English historian.

Words Nearby Grote

- gross weight

- Gros Ventre

- grotesquery

Dictionary.com Unabridged Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2024

How to use Grote in a sentence

“The first step is to ask all vendors what impact on their systems they anticipate, what options they have in place to enable performance and what items they have on their roadmap to improve the performance of their marketing,” said Grote .

Grote offered more advice on how to make this transition as smooth as possible.

Grote Industries Indiana-based, privately held business manufacturing vehicle safety systems.

The fact of these petitions being presented, encouraged Mr. Grote to make his annual motion in favour of vote by ballot.

Mr. Grote 's speech on this occasion contained many specious arguments, and it appears to have had a great effect upon the house.

Mr. Grote 's motion was further opposed by Mr. Charles Buller, albeit he was his friend.

On a division Mr. Grote 's amendment was rejected by a majority of one hundred and twenty-five to twenty-three.

Mr. Grote , in reply, said that the designation was quite as respectable as that of "literary Whig."

British Dictionary definitions for Grote

/ ( ɡrəʊt ) /

George. 1794–1871, English historian, noted particularly for his History of Greece (1846–56)

Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

The Great Trek ( Afrikaans : Die Groot Trek [di ˌχruət ˈtrɛk] ; Dutch : De Grote Trek [də ˌɣroːtə ˈtrɛk] ) was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial administration. The Great Trek resulted from the culmination of tensions between rural descendants of the Cape's original European settlers, known collectively as Boers , and the British Empire . It was also reflective of an increasingly common trend among individual Boer communities to pursue an isolationist and semi-nomadic lifestyle away from the developing administrative complexities in Cape Town . Boers who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as voortrekkers ( /ˈfʊərtrɛkərz/ , Afrikaans: [ˈfuərˌtrɛkərs] ), meaning "pioneers", "pathfinders" (literally "fore-trekkers") in Dutch and Afrikaans .

The Great Trek led directly to the founding of several autonomous Boer republics , namely the South African Republic (also known simply as the Transvaal ), the Orange Free State , and the Natalia Republic . It also led to conflicts that resulted in the displacement of the Northern Ndebele people , and conflicts with the Zulu people that contributed to the decline and eventual collapse of the Zulu Kingdom .

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Cape of Good Hope area was populated by Khoisan tribes The first Europeans settled in the Cape area under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company (also known by its Dutch initials VOC ), which established a victualling station there in 1652 to provide its outward bound fleets with fresh provisions and a harbour of refuge during the long sea journey from Europe to Asia. In a few short decades, the Cape had become home to a large population of "vrijlieden" , also denoted as "vrijburgers" (free citizens), former Company employees who remained in Dutch territories overseas after completing their contracts. Since the primary purpose of the Cape settlement at the time was to stock provisions for passing Dutch ships, the VOC offered grants of farmland to its employees under the condition they would cultivate grain for the Company warehouses, and released them from their contracts to save on their wages. Vrijburgers were granted tax-exempt status for 12 years and loaned all the necessary seeds and farming implements they requested. They were married Dutch citizens, considered "of good character" by the Company, and had to commit to spending at least 20 years on the African continent. Reflecting the multi-national character of the VOC's workforce, some German soldiers and sailors were also considered for vrijburger status as well, and in 1688 the Dutch government sponsored the resettlement of over a hundred French Huguenot refugees at the Cape. As a result, by 1691 over a quarter of the colony's European population was not ethnically Dutch. Nevertheless, there was a degree of cultural assimilation through intermarriage, and the almost universal adoption of the Dutch language. Cleavages were likelier to occur along social and economic lines; broadly speaking, the Cape colonists were delineated into Boers , poor farmers who settled directly on the frontier, and the more affluent, predominantly urbanised Cape Dutch .

Following the Flanders Campaign and the Batavian Revolution in Amsterdam , France assisted in the establishment of a pro-French client state, the Batavian Republic , on Dutch soil. This opened the Cape to French warships. To protect her own prosperous maritime shipping routes, Great Britain occupied the fledgling colony by force until 1803. From 1806 to 1814, the Cape was governed as a British military dependency, whose sole importance to the Royal Navy was its strategic relation to Indian maritime traffic. The British formally assumed permanent administrative control around 1815, as a result of the Treaty of Paris .

At the onset of the British rule, the Cape Colony encompassed 100,000 square miles (260,000 km 2 ) and was populated by about 26,720 people of European descent, a relative majority of whom were of Dutch origin. Just over a quarter were of German ancestry and about one-sixth were descended from French Huguenots, although most had ceased speaking French since about 1750. There were also 30,000 African and Asian slaves owned by the settlers, and about 17,000 indigenous Khoisan . Relations between the settlers – especially the Boers – and the new administration quickly soured. The British authorities were adamantly opposed to the Boers' ownership of slaves and what was perceived as their unduly harsh treatment of the indigenous peoples.

The British government insisted that the Cape finance its own affairs through self-taxation, an approach which was alien to both the Boers and the Dutch merchants in Cape Town. In 1815, the controversial arrest of a white farmer for allegedly assaulting one of his servants resulted in the abortive Slachter's Nek Rebellion . The British retaliated by hanging at least five Boers for insurrection. In 1828, the Cape governor declared that all native inhabitants but slaves were to have the rights of "citizens", in respect of security and property ownership, on parity with the settlers. This had the effect of further alienating the colony's white population. Boer resentment of successive British administrators continued to grow throughout the late 1820s and early 1830s, especially with the official imposition of the English language. This replaced Dutch with English as the language used in the Cape's judicial and political systems, putting the Boers at a disadvantage, as most spoke little or no English.

Britain's alienation of the Boers was particularly amplified by the decision to abolish slavery in all its colonies in 1834. All 35,000 slaves registered with the Cape governor were to be freed and given rights on par with other citizens, although in most cases their masters could retain them as apprentices until 1838. Many Boers, especially those involved with grain and wine production, were dependent on slave labour; for example, 94% of all white farmers in the vicinity of Stellenbosch owned slaves at the time, and the size of their slave holdings correlated greatly to their production output. Compensation was offered by the British government, but payment had to be received in London , and few Boers possessed the funds to make the trip.

Bridling at what they considered an unwarranted intrusion into their way of life, some in the Boer community considered selling their farms and venturing deep into South Africa's unmapped interior to preempt further disputes and live completely independent from British rule. Others, especially trekboers , a class of Boers who pursued semi-nomadic pastoral activities, were frustrated by the apparent unwillingness or inability of the British government to extend the borders of the Cape Colony eastward and provide them with access to more prime pasture and economic opportunities. They resolved to trek beyond the colony's borders on their own.

Although it did nothing to impede the Great Trek, Great Britain viewed the movement with pronounced trepidation. The British government initially suggested that conflict in the far interior of Southern Africa between the migrating Boers and the Bantu peoples they encountered would require an expensive military intervention. However, authorities at the Cape also judged that the human and material cost of pursuing the settlers and attempting to re-impose an unpopular system of governance on those who had deliberately spurned it was not worth the immediate risk. Some officials were concerned for the tribes the Boers were certain to encounter, and whether these tribes would be enslaved or otherwise reduced to a state of penury .

The Great Trek was not universally popular among the settlers either. Around 12,000 of them took part in the migration, about a fifth of the colony's Dutch-speaking white population at the time. The Dutch Reformed Church , to which most of the Boers belonged, explicitly refused to endorse the Great Trek. Despite their hostility towards the British, there were Boers who chose to remain in the Cape of their own accord.

For its part, the distinct Cape Dutch community had accepted British rule; many of its members even considered themselves loyal British subjects with a special affection for English culture. The Cape Dutch were also much more heavily urbanised and therefore less likely to be susceptible to the same rural grievances and considerations as those held by the Boers.

Exploratory treks to Natal

In January 1832, Andrew Smith (an Englishman) and William Berg (a Boer farmer) scouted Natal as a potential colony. On their return to the Cape, Smith waxed very enthusiastic, and the impact of discussions Berg had with the Boers proved crucial. Berg portrayed Natal as a land of exceptional farming quality, well watered, and nearly devoid of inhabitants.