Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2024

Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: evidence from homogeneous panels of countries

- Pablo Juan Cárdenas-García ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1779-392X 1 ,

- Juan Gabriel Brida 2 &

- Verónica Segarra 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 308 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3248 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

Having previously analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic growth from distinct perspectives, this paper attempts to fill the void existing in scientific research on the relationship between tourism and economic development, by analyzing the relationship between these variables using a sample of 123 countries between 1995 and 2019. The Dumistrescu and Hurlin adaptation of the Granger causality test was used. This study takes a critical look at causal analysis with heterogeneous panels, given the substantial differences found between the results of the causal analysis with the complete panel as compared to the analysis of homogeneous country groups, in terms of their dynamics of tourism specialization and economic development. On the one hand, a one-way causal relationship exists from tourism to development in countries having low levels of tourism specialization and development. On the other hand, a one-way causal relationship exists by which development contributes to tourism in countries with high levels of development and tourism specialization.

Similar content being viewed by others

A qualitative dynamic analysis of the relationship between tourism and human development

Gravity models do not explain, and cannot predict, international migration dynamics

The coordination pattern of tourism efficiency and development level in Guangdong Province under high-quality development

Introduction.

Across the world, tourism is one of the most important sectors. It has undergone exponential growth since the mid-1900s and is currently experiencing growth rates that exceed those of other economic sectors (Yazdi, 2019 ).

Today, tourism is a major source of income for countries that specialize in this sector, generating 5.8% of the global GDP (5.8 billion US$) in 2021 (UNWTO, 2022 ) and providing 5.4% of all jobs (289 million) worldwide. Although its relevance is clear, tourism data have declined dramatically due to the recent impact of the Covid-19 health crisis. In 2019, prior to the pandemic (UNWTO, 2020 ), tourism represented 10.3% of the worldwide GDP (9.6 billion US$), with the number of tourism-related jobs reaching 10.2% of the global total (333 million). With the evolution of the pandemic and the regained trust of tourists across the globe, it is estimated that by 2022, approximately 80% of the pre-pandemic figures will be attained, with a full recovery being expected by 2024 (UNWTO, 2022 ).

Given the importance of this economic activity, many countries consider tourism to be a tool enabling economic growth (Corbet et al., 2019 ; Ohlan, 2017 ; Xia et al., 2021 ). Numerous works have analyzed the relationship between increased tourism and economic growth; and some systematic reviews have been carried out on this relationship (Brida et al., 2016 ; Ahmad et al., 2020 ), examining the main contributions over the first two decades of this century. These reviews have revealed evidence in this area: in some cases, it has been found that tourism contributes to economic growth while, in other cases, the economic cycle influences tourism expansion. Moreover, other works offer evidence of a bi-directional relationship between these variables.

Distinct international organizations (OECD, 2010 ; UNCTAD, 2011 ) have suggested that not only does tourism promote economic growth, it also contributes to socio-economic advances in the host regions. This may be the real importance of tourism, since the ultimate objective of any government is to improve a country’s socio-economic development (UNDP, 1990 ).

The development of economic and other policies related to the economic scope of tourism, in addition to promoting economic growth, are also intended to improve other non-economic factors such as education, safety, and health. Improvements in these factors lead to a better life for the host population (Lee, 2017 ; Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

Given tourism’s capacity as an instrument of economic development (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ), distinct institutions such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the United Nations World Tourism Organization and the World Bank, have begun funding projects that consider tourism to be a tool for improved socio-economic development, especially in less advanced countries (Carrillo and Pulido, 2019 ).

This new trend within the scientific literature establishes, firstly, that tourism drives economic growth and, secondly, that thanks to this economic growth, the population’s economic conditions may be improved (Croes et al., 2021 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ). However, to take advantage of the economic growth generated by tourism activity to boost economic development, specific policies should be developed. These policies should determine the initial conditions to be met by host countries committed to tourism as an instrument of economic development. These conditions include regulation, tax system, and infrastructure provision (Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Lejárraga and Walkenhorst, 2013 ; Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ).

Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate between the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, whereby tourism boosts the economy of countries committed to tourism, traditionally measured through an increase in the Gross Domestic Product (Alcalá-Ordóñez et al., 2023 ; Brida et al., 2016 ), and the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic development, which measures the effect of tourism on other factors (not only economic content but also inequality, education, and health) which, together with economic criteria, serve as the foundation to measure a population’s development (Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

However, unlike the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, few empirical studies have examined tourism’s capacity as a tool for development (Bojanic and Lo, 2016 ; Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Croes, 2012 ).

To help fill this gap in the literature analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, this work examines the contribution of tourism to economic development, given that the relationship between tourism and economic growth has been widely analyzed by the scientific literature. Moreover, given that the literature has demonstrated that tourism contributes to economic growth, this work aims to analyze whether it also contributes to economic development, considering development in the broadest possible sense by including economic and socioeconomic variables in the multi-dimensional concept (Wahyuningsih et al., 2020 ).

Therefore, based on the results of this work, it is possible to determine whether the commitment made by many international organizations and institutions in financing tourism projects designed to improve the host population’s socioeconomic conditions, especially in countries with lower development levels, has, in fact, resulted in improved development levels.

It also presents a critical view of causal analyses that rely on heterogeneous panels, examining whether the conclusions reached for a complete panel differ from those obtained when analyzing homogeneous groups within the panel. As seen in the literature review analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, empirical works using panel data from several countries tend to generalize the results obtained to the entire panel, without verifying whether, in fact, they are relevant for all of the analyzed countries or only some of the same. Therefore, this study takes an innovative approach by examining the panel countries separately, analyzing the homogeneous groups distinctly.

Therefore, this article presents an empirical analysis examining whether a causal relationship exists between tourism and economic development, with development being considered to be a multi-dimensional variable including a variety of factors, distinct from economic ones. Panel data from 123 countries during the 1995–2019 period was considered to examine the causal relationship between tourism and economic development. For this, the Granger causality test was performed, applying the adaptation of this test made by Dumistrescu and Hurlin. First, a causal analysis was performed collectively for all of the countries of the panel. Then, a specific analysis was performed for each of the homogeneous groups of countries identified within the panel, formed according to levels of tourism specialization and development.

This article provides information on tourism’s capacity to serve as an instrument of development, helping to fill the gap in scientific research in this area. It critically examines the use of causal analyses based on heterogeneous samples of countries. This work offers the following main novelties as compared to prior works on the same topic: firstly, it examines the relationship between tourism and economic development, while the majority of the existing works only analyze the relationship between tourism and economic growth; secondly, it analyzes a large sample of countries, representing all of the global geographic areas, whereas the literature has only considered works from specific countries or a limited number of nations linked to a specific country in a specific geographical area, and; thirdly, it analyzes the panel both individually and collectively, for each of the homogenous groups of countries identified, permitting the adoption of specific policies for each group of countries according to the identified relationship, as compared to the majority of works that only analyze the complete panel, generalizing these results for all countries in the sample.

Overall, the results suggest that a relationship exists between tourism and development in all of the analyzed countries from the sample. A specific analysis was performed for homogeneous country groups, only finding a causal relationship between tourism and development in certain country groups. This suggests that the use of heterogeneous country samples in causal analyses may give rise to inappropriate conclusions. This may be the case, for example, when finding causality for a broad panel of countries, although, in fact, only a limited number of panel units actually explain this causal relationship.

The remainder of the document is organized as follows: the next section offers a review of the few existing scientific works on the relationship between tourism and economic development; section three describes the data used and briefly explains the methodology carried out; section four details the results obtained from the empirical analysis; and finally, the conclusions section discusses the main implications of the work, also providing some recommendations for economic policy.

Tourism and economic development

Numerous organizations currently recognize the importance of tourism as an instrument of economic development. It was not until the late 20th century, however, when the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), in its Manila Declaration, established that the development of international tourism may “help to eliminate the widening economic gap between developed and developing countries and ensure the steady acceleration of economic and social development and progress, in particular of the developing countries” (UNWTO, 1980 ).

From a theoretical point of view, tourism may be considered an effective activity for economic development. In fact, the theoretical foundations of many works are based on the relationship between tourism and development (Ashley et al., 2007 ; Bolwell and Weinz, 2011 ; Dieke, 2000 ; Sharpley and Telfer, 2015 ; Sindiga, 1999 ).

The link between tourism and economic development may arise from the increase in tourist activity, which promotes economic growth. As a result of this economic growth, policies may be developed to improve the resident population’s level of development (Alcalá-Ordóñez and Segarra, 2023 ).

Therefore, it is essential to identify the key variables permitting the measurement of the level of economic development and, therefore, those variables that serve as a basis for analyzing whether tourism results in improved the socioeconomic conditions of the host population (Croes et al., 2021 ). Since economic development refers not only to economic-based variables, but also to others such as inequality, education, or health (Todaro and Smith, 2020 ), when analyzing the economic development concept, it has been frequently linked to human development (Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ). Thus, we wish to highlight the major advances resulting from the publication of the Human Development Index (HDI) when measuring economic development, since it defines development as a multidimensional variable that combines three dimensions: health, education, and income level (UNDP, 2023 ).

However, despite the importance that many organizations have given to tourism as an instrument of economic development, basing their work on the relationship between these variables, a wide gap continues to exist in the scientific literature for empirical studies that examine the existence of a relationship between tourism and economic development, with very few empirical analyses analyzing this relationship.

First, a group of studies has examined the causal relationship between tourism and economic development, using heterogeneous samples, and without previously grouping the subjects based on homogeneous characteristics. Croes ( 2012 ) analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic development, measured through the HDI, finding that a bidirectional relationship exists for the cases of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Using annual data from 2001 to 2014, Meyer and Meyer ( 2016 ) performed a collective analysis of South African regions, determining that tourism contributes to economic development. For a panel of 63 countries worldwide, and once again relying on the HDI to define economic development, it was determined that tourism contributes to economic development. Kubickova et al. ( 2017 ), using annual data for the 1995–2007 period, analyzed Central America and Caribbean nations, determining the existence of this relationship by which tourism influences the level of economic development and that the level of development conditions the expansion of tourism. Another work examined nine micro-states of America, Europe, and Africa (Fahimi et al., 2018 ); and 21 European countries in which human capital was measured, as well as population density and tourism income, analyzing panel data and determining that tourism results in improved economic development. Finally, within this first group of works, Chattopadhyay et al. ( 2022 ), using a broad panel of destinations, (133 countries from all geographic areas of the globe) determined that there is no relationship between tourism and economic development.

Studies performed with large country samples that attempt to determine the causal relationship between tourism and economic development by analyzing countries that do not necessarily share homogeneous characteristics, may lead to erroneous conclusions, establishing causality (or not) for panel sets even when this situation is actually explained by a small number of panel units.

Second, another group of studies have analyzed the causal relationship between tourism and economic development, considering the previous limitation, and has grouped the subjects based on their homogeneous characteristics. Cárdenas-García et al. ( 2015 ) used annual data from 1990–2010, in a collective analysis of 144 countries, making a joint panel analysis and then examining two homogeneous groups of countries based on their level of economic development. They determined that tourism contributes to economic development, but only in the most developed group of countries. They determined that tourism contributes to economic development, both for the total sample and for the homogeneous groups analyzed. Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García ( 2021 ), using annual data for the 1993–2017 period, performed a joint analysis of 143 countries, followed by a specific analysis for three groups of countries sharing homogeneous characteristics in terms of tourism growth and development level. They determined that tourism contributes to economic development and that development level conditions tourism growth in the most developed countries.

Finally, another group of studies has analyzed the causal relationship between tourism and economic development in specific cases examined on an individual basis. In a specific analysis by Aruba et al. ( 2016 ), it was determined that tourism contributes to human development. Analyzing Malaysia, Tan et al. ( 2019 ) determined that tourism contributes to development, but only over the short term, and that level of development does not influence tourism growth. Similar results were obtained by Boonyasana and Chinnakum ( 2020 ) in an analysis carried out in Thailand. In this case of Thailand (Boonyasana and Chinnakum, 2020 ), which relied on the HDI, the relationship with economic growth was also analyzed, finding that an increase in tourism resulted in improved economic development. Finally, Croes et al. ( 2021 ), in a specific analysis of Poland, determined that tourism does not contribute to development.

As seen from the analysis of the most relevant publications detailed in Table 1 , few empirical works have considered the relationship between tourism and economic development, in contrast to the numerous works from the scientific literature that have examined the relationship between tourism and economic growth. Most of the works that have empirically analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic development have determined that tourism positively influences the improved economic development in host destinations. To a lesser extent, some studies have found a bidirectional relationship between these variables (Croes, 2012 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ; Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ) while others have found no relationship between tourism and economic development (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022 ; Croes et al., 2021 ).

Furthermore, in empirical works relying on panel data, the results have tended to be generalized to the entire panel, suggesting that tourism improves economic development in all countries that are part of the panel. This has been the case in all of the examined works, with the exception of two studies that analyzed the panel separately (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ; Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ).

Thus, it may be suggested that the use of very large country panels and, therefore, including very heterogeneous destinations, as was the case in the works of Biagi et al. ( 2017 ) using a panel of 63 countries, as well as that of Chattopadhyay et al. ( 2022 ) working with a panel of 133 countries, may lead to error, given that this relationship may only arise in certain destinations of the panel, although it is generalized to the entire panel.

This work serves to fill this gap in the literature by analyzing the panel both collectively and separately, for each of the homogenous groups of countries that have been previously identified.

The lack of relevant works on the relationship between tourism and development, and of studies using causal analyses to examine these variables based on heterogeneous panels, may lead to the creation of rash generalizations regarding the entirety of the analyzed countries. Thus, conclusions may be reached that are actually based on only specific panel units. Therefore, we believe that this study is justified.

Methodological approach

Given the objective of this study, to determine whether a causal relationship exists between tourism and socio-economic development, it is first necessary to identify the variables necessary to measure tourism activity and development level. Thus, the indicators are highly relevant, given that the choice of indicator may result in distinct results (Rosselló-Nadal and He, 2020 ; Song and Wu, 2021 ).

Table 2 details the measurement variables used in this work. Specifically, the following indicators have been used in this paper to measure tourism and economic development:

Measurement of tourist activity. In this work, we decided to consider tourism specialization, examining the number of international tourists received by a country with regard to its population size as the measurement variable.

This information on international tourists at a national level has been provided annually by the United Nations World Tourism Organization since 1995 (UNWTO, 2023 ). This variable has been relativized based on the country’s population, according to information provided by the World Bank on the residents of each country (WB, 2023 ).

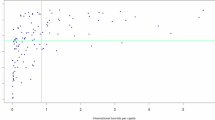

Tourism specialization is considered to be the level of tourism activity, specifically, the arrival of tourists, relativized based on the resident population, which allows for comparisons to be made between countries. It accurately measures whether or not a country is specialized in this economic activity. If the variable is used in absolute values, for example, the United States receives more tourists than Malta, so based on this variable it may be that the first country is more touristic than the second. However, in reality, just the opposite happens, Malta is a country in which tourist activity is more important for its economy than it is in the United States, so the use of tourist specialization as a measurement variable classifies, correctly, both Malta as a country with high tourism specialization and to the United States as a country with low tourism specialization.

Therefore, most of the scientific literature establishes the need to use the total number of tourists relativized per capita, given that this allows for the determination of the level of tourism specialization of a tourism destination (Dritsakis, 2012 ; Tang and Abosedra, 2016 ); furthermore, this indicator has been used in works analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development (for example, Biagi et al., 2017 ; Boonyasana and Chinnakum; 2020 ; Croes et al., 2021 ; Fahimi et al., 2018 ).

Although some works have used other variables to measure tourism, such as tourism income, exports, or tourist spending, these variables are not available for all of the countries making up the panel, so the sample would have been significantly reduced. Furthermore, the data available for these alternative variables do not come from homogeneous databases, and therefore cannot be compared.

Measurement of economic development. In this work, the Human Development Index has been used to measure development.

This information is provided by the United Nations Development Program, which has been publishing it annually at the country level since 1990 (UNDP, 2023 ).

The selection of this indicator to measure economic development is in line with other works that have defended its use to measure the impact on development level (for example, Jalil and Kamaruddin, 2018 ; Sajith and Malathi, 2020 ); this indicator has also been used in works analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development (for example, Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ; Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ).

Although some works have used other variables, such as poverty or inequality, to measure development, these variables are not available for all of the countries forming the panel. Therefore the sample would have been considerably reduced and the data available for these alternative variables do not come from homogenous databases, and therefore comparisons cannot be made.

These indicators are available for a total of 123 countries, across the globe. Thus, these countries form part of the sample analyzed in this study.

As for the time frame considered in this work, two main issues were relevant when determining this period: on the one hand, there is an initial time restriction for the analyzed series, given that information on the arrival of international tourists is only available as of 1995, the first year when this information was provided by the UNWTO. On the other hand, it was necessary to consider the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting tourism sector crisis, which also affected the global economy as a whole. Therefore, our time series ended as of 2019, with the overall time frame including data from 1995 to 2019, a 25-year period.

Previous considerations

Caution should be taken when considering causality tests to determine the relationships between two variables, especially in cases in which large heterogeneous samples are used. This is due to the fact that generalized conclusions may be reached when, in fact, the causality is only produced by some of the subjects of the analyzed sample. This study is based on this premise. While heterogeneity in a sample is clearly a very relevant aspect, in some cases, it may lead to conclusions that are less than appropriate.

In this work, a collective causal analysis has been performed on all of the countries of the panel, which consists of 123 countries. However, given that it is a broad sample including countries having major differences in terms of size, region, development level, or tourism performance, the conclusions obtained from this analysis may lead to the generalization of certain conclusions for the entire sample set, when in fact, these relationships may only be the case for a very small portion of the sample. This has been the case in other works that have made generalized conclusions from relatively large samples in which the sample’s homogeneity regarding certain patterns was not previously verified (Badulescu et al., 2021 ; Ömer et al., 2018 ; Gedikli et al., 2022 ; Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ; Xia et al., 2021 ).

Therefore, after performing a collective analysis of the entire panel, the causal relationship between tourism and development was then determined for homogeneous groups of countries that share common patterns of tourism performance and economic development level, to analyze whether the generalized conclusions obtained in the previous section differ from those made for the individual groups. This was in line with strategies that have been used in other works that have grouped countries based on tourism performance (Min et al., 2016 ) or economic development level (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ), prior to engaging in causal analyses. To classify the countries into homogeneous groups based on tourism performance and development level, a previous work was used (Brida et al., 2023 ) which considered the same sample of 123 countries, relying on the same data to measure tourism and development level and the same time frame. This guarantees the coherence of the results obtained in this work.

From the entire panel of 123 countries, a total of six country groups were identified as having a similar dynamic of tourism and development, based on qualitative dynamic behavior. In addition, an “outlier” group of countries was found. These outlier countries do not fit into any of the groups (Brida et al., 2023 ). The three main groups of countries were considered, discarding three other groups due to their small size. Table 3 presents the group of countries sharing similar dynamics in terms of tourism performance and economic development level.

Applied methodology

As indicated above, this work uses the Tourist Specialization Rate (TIR) and the Human Development Index (HDI) to measure tourism and economic development, respectively. In both cases, we work with the natural logarithm (l.TIR and l.HDI) as well as the first differences between the variables (d.l.TIR and d.l.HDI), which measure the growth of these variables.

A complete panel of countries is used, consisting of 123 countries. The three main groups indicated in the previous section are also considered (the first of the groups contains 36 countries, the second contains 29 and the last group contains 43).

The Granger causality test ( 1969 ) is used to analyze the relationships between tourism specialization and development level; this test shows if one variable predicts the other, but this should not be confused with a cause-effect relationship.

In the context of panel data, different tests may be used to analyze causality. Most of these tests differ with regard to the assumptions of homogeneity of the panel unit coefficients. While the standard form of the Granger causality test for panels assumes that all of the coefficients are equal between the countries forming part of the panel, the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012) considers that the coefficients are different between the countries forming part of the panel. Therefore, in this work, Granger’s causality is analyzed using the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012). In this test, the null hypothesis is of no homogeneous causality; in other words, according to the null hypothesis, causality does not exist for any of the countries of the analyzed sample whereas, according to the alternative hypothesis, in which the regression model may be different in the distinct countries, causality is verified for at least some countries. The approach used by Dumitrescu and Hurlin ( 2012 ) is more flexible in its assumptions since although the coefficients of the regressions proposed in the tests are constant over time, the possibility that they may differ for each of the panel elements is accepted. This approach has more realistic assumptions, given that countries exhibit different behaviors. One relevant aspect of this type of tests is that they offer no information on which countries lead to the rejection of the lack of causality.

Given the specific characteristics of this type of tests, the presence of very heterogeneous samples may lead to inappropriate conclusions. For example, causality may be assumed for a panel of countries, when only a few of the panel’s units actually explain this relationship. Therefore, this analysis attempts to offer novel information on this issue, revealing that the conclusions obtained for the complete set of 123 countries are not necessarily the same as those obtained for each homogeneous group of countries when analyzed individually.

Given the nature of the variables considered in this work, specifically, regarding tourism, it is expected that a shock taking place in one country may be transmitted to other countries. Therefore, we first analyze the dependency between countries, since this may lead to biases (Pesaran, 2006 ). The Pesaran cross-sectional dependence test (2004) is used for the total sample and for each of the three groups individually.

First, a dependence analysis is performed for the countries of the sample, verifying the existence of dependence between the panel subjects. A cross-sectional dependence test (Pesaran, 2004 ) is used, first for the overall set of countries in the sample and second, for each of the groups of countries sharing homogeneous characteristics.

The results are presented in Table 4 , indicating that the test is statistically significant for the two variables, both for all of the countries in the sample and for each of the homogeneous country clusters, for the variables taken in logarithms as well as their first differences.

Upon rejecting the null hypothesis of non-cross-sectional dependence, it is assumed that a shock occurs in a country that may be transmitted to other countries in the sample. In fact, the lack of dependence between the variables, both tourism and development, is natural in this type of variables, given the economic cycle through the globalization of the economic activity, common regions visited by tourists, the spillover effect, etc.

Second, the stationary nature of the series is tested, given that cross-sectional dependence has been detected between the variables. First-generation tests may present certain biases in the rejection of the null hypothesis since first-generation unit root tests do not permit the inclusion of dependence between countries (Pesaran, 2007 ). On the other hand, second-generation tests permit the inclusion of dependence and heterogeneity. Therefore, for this analysis, the augmented IPS test (CIPS) proposed by Pesaran ( 2007 ) is used. This second-generation unit root test is the most appropriate for this case, given the cross-sectional dependence.

The results are presented in Table 5 , showing the statistics of the CIPS test for both the overall set of countries in the sample and in each of the homogeneous clusters of countries. The results are presented for models with 1, 2, and 3 delays, considering both the variables in the logarithm and their first differences.

As observed, the null hypothesis of unit root is not rejected for the variables in levels, but it is rejected for the first differences. This result is found in all of the cases, for both the total sample and for each of the homogeneous groups, with a significance of 1%. Therefore, the variables are stationary in their first differences, that is, the variables are integrated at order 1. Given that the causality test requires stationary variables, in this work it is used with the variation or growth rate of the variables, that is, the variable at t minus the variable at t−1.

Finally, to analyze Granger’s causality, the test by Dumitrescu and Hurlin ( 2012 ) is used. This test is used to analyze the causal relationship in both directions; that is, whether tourism contributes to economic development and whether the economic development level conditions tourism specialization. Statistics are calculated considering models with 1, 2, and 3 delays. Considering that cross-sectional dependence exists, the p-values are corrected using bootstrap techniques (making 500 replications). Given that the test requires stationary variables, primary differences of both variables were considered.

Table 6 presents the result of the Granger causality analysis using the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012), considering the null hypothesis that tourism does not condition development level, either for all of the countries or for each homogeneous country cluster.

For the entire sample of countries, the results suggest that the null hypothesis of no causality from tourism to development was rejected when considering 3 delays (in other works analyzing the relationship between tourism and development, the null hypothesis was rejected with a similar level of delay: Rivera ( 2017 ) when considering 3–4 delays or Ulrich et al. ( 2018 ) when considering 3 delays). This suggests that for the entire panel, one-way causality exists whereby tourism influences economic development, demonstrating that tourism specialization contributes positively to improving the economic development of countries opting for tourism development. This is in line with the results of Meyer and Meyer ( 2016 ), Ridderstaat et al. ( 2016 ); Biagi et al. ( 2017 ); Fahimi et al. ( 2018 ); Tan et al. ( 2019 ), or Boonyasana and Chinnakum ( 2020 ).

However, the previous conclusion is very general, given that it is based on a very large sample of countries. Therefore, it may be erroneous to generalize that tourism is a tool for development. In fact, the results indicate that, when analyzing causality by homogeneous groups of countries, sharing similar dynamics in both tourism and development, the null hypothesis of no causality from tourism to development is only rejected for the group C countries, when considering three delays. Therefore, the development of generalized policies to expand tourism in order to improve the socioeconomic conditions of any destination type should consider that this relationship between tourism and economic development does not occur in all cases. Thus, it should first be determined if the countries opting for this activity have certain characteristics that will permit a positive relationship between said variables.

In other words, it may be a mistake to generalize that tourism contributes to economic development for all countries, even though a causal relationship exists for the entire panel. Instead, it should be understood that tourism permits an improvement in the level of development only in certain countries, in line with the results of Cárdenas-García et al. ( 2015 ) or Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García ( 2021 ). In this specific work, this positive relationship between tourism and development only occurs in countries from group C, which are characterized by a low level of tourism specialization and a low level of development. Some works have found similar results for countries from group C. For example, Sharma et al. ( 2020 ) found the same relationship for India, while Nonthapot ( 2014 ) had similar findings for certain countries in Asia and the Pacific, which also made up group C. Some recent works have analyzed the relationship between tourism specialization and economic growth, finding similar results. This has been the case with Albaladejo et al. ( 2023 ), who found a relationship from tourism to economic growth only for countries where income is low, and the tourism sector is not yet developed.

These countries have certain limitations since even when tourism contributes to improved economic development, their low levels of tourism specialization do not allow them to reach adequate host population socioeconomic conditions. Therefore, investments in tourism are necessary there in order to increase tourism specialization levels. This increase in tourism may allow these countries to achieve development levels that are similar to other countries having better population conditions.

Therefore, in this group, consisting of 43 countries, a causal relationship exists, given that these countries are characterized by a low level of tourism specialization. However, the weakness of this activity, due to its low relevance in the country, prevents it from increasing the level of economic development. In these countries (details of these countries can be found in Table 3 , specifically, the countries included in Group C), policymakers have to develop policies to improve tourism infrastructure as a prior step to improving their levels of development.

On the other hand, in Table 7 , the results of Granger’s causal analysis based on the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012) are presented, considering the null hypothesis that development level does not condition an increase in tourism, both in the overall sample set and in each of the homogeneous country clusters.

The results indicate that, for the entire country sample, the null hypothesis of no causality from development to tourism is not rejected, for any type of delay. This suggests that, for the entire panel, one-way causality does not exist, with level of development influencing the level of tourism specialization. This is in line with the results of Croes et al. ( 2021 ) in a specific analysis in Poland.

Once again, this conclusion is quite general, given that it has been based on a very broad sample of countries. Therefore, it may be erroneous to generalize that the development level does not condition tourism specialization. Past studies using a large panel of countries, such as the work of Chattopadhyay et al. ( 2022 ) analyzing panel data from 133 countries, have been generalized to all of the analyzed countries, suggesting that economic development level does not condition the arrival of tourists to the destination, although, in fact, this relationship may only exist in specific countries within the analyzed panel.

In fact, the results indicate that, when analyzing causality by homogeneous country groups sharing a similar dynamic, for both tourism and development, the null hypothesis of no causality from development to tourism is only rejected for country group A when considering 2–3 delays. Although the statistics of the test differ, when the sample’s time frame is small, as in this case, the Z-bar tilde statistic is more appropriate.

Thus, development level influences tourism growth in Group A countries, which are characterized by a high level of development and tourism specialization, in accordance with the prior results of Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García ( 2021 ).

These results, suggesting that tourism is affected by economic development level, but only in the most developed countries, imply that the existence of better socioeconomic conditions in these countries, which tend to have better healthcare systems, infrastructures, levels of human resource training, and security, results in an increase in tourist arrivals to these countries. In fact, when traveling to a specific tourist destination, if this destination offers attractive factors and a higher level of economic development, an increase in tourist flows was fully expected.

In this group, consisting of 36 countries, the high development level, that is, the proper provision of socio-economic factors in their economic foundations (training, infrastructures, safety, health, etc.) has led to the attraction of a large number of tourists to their region, making their countries having high tourism specialization.

Although international organizations have recognized the importance of tourism as an instrument of economic development, based on the theoretical relationship between these two variables, few empirical studies have considered the consequences of the relationship between tourism and development.

Furthermore, some hasty generalizations have been made regarding the analysis of this relationship and the analysis of the relationship of tourism with other economic variables. Oftentimes, conclusions have been based on heterogeneous panels containing large numbers of subjects. This may lead to erroneous results interpretation, basing these results on the entire panel when, in fact, they only result from specific panel units.

Given this gap in the scientific literature, this work attempts to analyze the relationship between tourism and economic development, considering the panel data in a complete and separate manner for each of the previously identified country groups.

The results highlight the need to adopt economic policies that consider the uniqueness of each of the countries that use tourism as an instrument to improve their socioeconomic conditions, given that the results differ according to the specific characteristics of the analyzed country groups.

This work provides precise results regarding the need for policymakers to develop public policies to ensure that tourism contributes to the improvement of economic development, based on the category of the country using this economic activity to achieve greater levels of economic development.

Specifically, this work has determined that tourism contributes to economic development, but only in countries that previously had a lower level of tourism specialization and were less developed. This highlights the need to invest in tourism to attract more tourists to these countries to increase their economic development levels. Countries having major natural attraction resources or factors, such as the Dominican Republic, Egypt, India, Morocco, and Vietnam, need to improve their positioning in the international markets in order to attain a higher level of tourism specialization, which will lead to improved development levels.

Furthermore, the results of this study suggest that a greater past economic development level of a country will help attract more tourists to these countries, highlighting the need to invest in security, infrastructures, and health in order for these destinations to be considered attractive and increase tourist arrival. In fact, given their increased levels of development, countries such as Spain, Greece, Italy, Qatar, and Uruguay have become attractive to tourists, with soaring numbers of visitors and high levels of tourism specialization.

Therefore, the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic development should focus on the differentiated treatment of countries in terms of their specific characteristics, since working with panel data with large samples and heterogenous characteristics may lead to incorrect results generalizations to all of the analyzed destinations, even though the obtained relationship in fact only takes place in certain countries of the sample.

Conclusions and policy implications

Within this context, the objective of this study is twofold: on the one hand, it aims to contribute to the lack of empirical works analyzing the causal relationship between tourism and economic development using Granger’s causality analysis for a broad sample of countries from across the globe. On the other hand, it critically examines the use of causality analysis in heterogeneous samples, by verifying that the results for the panel set differ from the results obtained when analyzing homogeneous groups in terms of tourism specialization and development level.

In fact, upon analyzing the causal relationship from tourism to development, and the causal relationship from development to tourism, the results from the entire panel, consisting of 123 countries, differ from those obtained when analyzing causality by homogeneous country groups, in terms of tourism specialization and economic development dynamics of these countries.

On the one hand, a one-way causality relationship is found to exist, whereby tourism influences economic development for the entire sample of countries, although this conclusion cannot be generalized, since this relationship is only explained by countries belonging to Group C (countries with low levels of tourism specialization and low development levels). This indicates that, although a causal relationship exists by which tourism contributes to economic development in these countries, the low level of tourism specialization does not permit growth to appropriate development levels.

The existence of a causal relationship whereby the increase in tourism precedes the improvement of economic development in this group of countries having a low level of tourism specialization and economic development, suggests the appropriateness of the focus by distinct international organizations, such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development or the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, on funding tourism projects (through the provision of tourism infrastructure, the stimulation of tourism supply, or positioning in international markets) in countries with low economic development levels. This work has demonstrated that investment in tourism results in the attracting of a greater flow of tourists, which will contribute to improved economic development levels.

Therefore, both international organizations financing projects and public administrations in these countries should increase the funding of projects linked to tourism development, in order to increase the flow of tourism to these destinations. This, given that an increase in tourism specialization suggests an increased level of development due to the demonstrated existence of a one-way causal relationship from tourism to development in these countries, many of which form part of the group of so-called “least developed” countries. However, according to the results obtained in this work, this relationship is not instantaneous, but rather, a certain delay exists in order for economic development to improve as a result of the increase in tourism. Therefore, public managers must adopt a medium and long-term vision of tourism activity as an instrument of development, moving away from short-term policies seeking immediate results, since this link only occurs over a broad time horizon.

On the other hand, this study reveals that a one-way causal relationship does not exist, by which the level of development influences tourism specialization level for the entire sample of countries. However, this conclusion, once again, cannot be generalized given that in countries belonging to Group A (countries with a high development level and a high tourism specialization level), a high level of economic development determines a higher level of tourism specialization. This is because the socio-economic structure of these countries (infrastructures, training or education, health, safety, etc.) permits their shaping as attractive tourist destinations, thereby increasing the number of tourists visiting them.

Therefore, investments made by public administrations to improve these factors in other countries that currently do not display this causal relationship implies the creation of the necessary foundations to increase their tourism specialization and, therefore, as shown in other works, tourism growth will permit economic growth, with all of the associated benefits for these countries.

Therefore, to attract tourist flows, it is not only important for a country to have attractive factors or resources, but also to have an adequate level of prior development. In other words, the tourists should perceive an adequate level of security in the destination; they should be able to use different infrastructures such as roads, airports, or the Internet; and they should receive suitable services at the destination from personnel having an appropriate level of training. The most developed countries, which are the destinations having the greatest endowment of these resources, are the ones that currently receive the most tourist flows thanks to the existence of these factors.

Therefore, less developed countries that are committed to tourism as an instrument to improve economic development should first commit to the provision of these resources if they hope to increase tourist flows. If this increase in tourism takes place in these countries, their economic development levels have been demonstrated to improve. However, since these countries are characterized by low levels of resources, cooperation by organizations financing the necessary investments is key to providing them with these resources.

Thus, a critical perspective is necessary when considering the relationship between tourism and economic development based on global causal analysis using heterogeneous samples with numerous subjects. As in this case, carrying out analyses on homogeneous groups may offer interesting results for policymakers attempting to suitably manage population development improvements due to tourism growth and tourism increases resulting from higher development levels.

One limitation of this work is its national scope since evidence suggests that tourism is a regional and local activity. Therefore, it may be interesting to apply this same approach on a regional level, using previously identified homogeneous groups.

And given that the existence of a causal relationship (in either direction) between tourism and development has only been determined for a specific set of countries, future works could consider other country-specific factors that may determine this causal relationship, in addition to the dynamics of tourism specialization and development level.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ahmad N, Menegaki AN, Al-Muharrami S (2020) Systematic literature review of tourism growth nexus: An overview of the literature and a content analysis of 100 most influential papers. J Econ Surv 34(5):1068–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12386

Article Google Scholar

Albaladejo I, Brida G, González M y Segarra V (2023) A new look to the tourism and economic growth nexus: a clustering and panel causality analysis. World Econ https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13459

Alcalá-Ordóñez A, Brida JG, Cárdenas-García PJ (2023) Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been confirmed? Evidence from an updated literature review. Curr Issues Tour https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2023.2272730

Alcalá-Ordóñez A, Segarra V (2023) Tourism and economic development: a literature review to highlight main empirical findings. Tour Econom https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166231219638

Ashley C, De Brine P, Lehr A, Wilde H (2007) The role of the tourism sector in expanding economic opportunity. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge MA

Google Scholar

Biagi B, Ladu MG, Royuela V (2017) Human development and tourism specialization. Evidence from a panel of developed and developing countries. Int J Tour Res 19(2):160–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2094

Badulescu D, Simut R, Mester I, Dzitac S, Sehleanu M, Bac DP, Badulescu A (2021) Do economic growth and environment quality contribute to tourism development in EU countries? A panel data analysis. Technol Econom Dev Econ 27(6):1509–1538. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2021.15781

Bojanic DC, Lo M (2016) A comparison of the moderating effect of tourism reliance on the economic development for islands and other countries. Tour Manag 53:207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.10.00

Bolwell D, Weinz W (2011) Poverty reduction through tourism. International Labour Office, Geneva

Boonyasana P, Chinnakum W (2020) Linkages among tourism demand, human development, and CO 2 emissions in Thailand. Abac J 40(3):78–98

Brida JG, Cárdenas-García PJ, Segarra V (2023) Turismo y Desarrollo Económico: una Exploración Empírica. Red Nacional de Investigadores en Economía (RedNIE), Working Papers, 283

Brida JG, Cortes-Jimenez I, Pulina M (2016) Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Curr Issues Tour 19(5):394–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.868414

Cárdenas-García PJ, Pulido-Fernández JI (2019) Tourism as an economic development tool. Key factors. Curr Issues Tour 22(17):2082–2108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1420042

Cárdenas-García PJ, Sánchez-Rivero M, Pulido-Fernández JI (2015) Does tourism growth influence economic development? J Travel Res 54(2):206–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513514297

Carrillo I, Pulido JI, (2019) Is the financing of tourism by international financial institutions inclusive? A proposal for measurement. Curr Issues Tour 22:330–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1260529

Chattopadhyay M, Kumar A, Ali S, Mitra SK (2022) Human development and tourism growth’s relationship across countries: a panel threshold analysis. J Sustain Tour 30(6):1384–1402. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1949017

Corbet S, O’Connell JF, Efthymiou M, Guiomard C, Lucey B (2019) The impact of terrorism on European tourism. Ann Tour Res 75:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.012

Croes R (2012) Assessing tourism development from Sen’s capability approach. J Travel Res 51(5):542–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511431323

Article ADS Google Scholar

Croes R, Ridderstaat J, Bak M, Zientara P (2021) Tourism specialization, economic growth, human development and transition economies: the case of Poland. Tour Manag 82:104181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104181

Dieke P (2000) The political economy of tourism development in Africa. Cognizant, New York

Dritsakis N (2012) Tourism development and economic growth in seven Mediterranean countries: a panel data approach. Tour Econ 18(4):801–816. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2012.0140

Dumitrescu EI, Hurlin C (2012) Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econom Model 29(4):1450–1460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.014

Fahimi A, Saint Akadiri S, Seraj M, Akadiri AC (2018) Testing the role of tourism and human capital development in economic growth. A panel causality study of micro states. Tour Manag Perspect 28:62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.08.004

Gedikli A, Erdoğan S, Çevik EI, Çevik E, Castanho RA, Couto G(2022) Dynamic relationship between international tourism, economic growth and environmental pollution in the OECD countries: evidence from panel VAR model. Econom Res 35:5907–5923. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2041063

Granger CWJ (1969) Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 37(3):424–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912791

Jalil SA, Kamaruddin MN (2018) Examining the relationship between human development index and socio-economic variables: a panel data analysis. J Int Bus Econ Entrepreneurship 3(2):37–44. https://doi.org/10.24191/jibe.v3i2.14431

Kubickova M, Croes R, Rivera M (2017) Human agency shaping tourism competitiveness and quality of life in developing economies. Tour Manag Perspect 22:120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.03.002

Lee YS (2017) General theory of law and development. Cornell Int Law Rev 50(3):432–435

CAS Google Scholar

Lejárraga I, Walkenhorst P (2013) Economic policy, tourism trade and productive diversification. Int Econ 135:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2013.09.001

Meyer DF, Meyer N (2016) The relationship between the tourism sector and local economic development (Led): the case of the Vaal Triangle region. South Afr J Environ Manag Tour 3(15):466–472

Min CK, Roh TS, Bak S (2016) Growth effects of leisure tourism and the level of economic development. Appl Econ 48(1):7–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2015.1073838

Nonthapot S (2014) The relationship between tourism and economic development in the Greater Mekong Subregion: panel cointegration and Granger causality. J Adv Res Law Econ 1(9):44–51

OECD (2010) Tourism trends & policies 2010. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

Ohlan R (2017) The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Bus J 3(1):9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbj.2017.01.003

Ömer Y, Muhammet D, Kerem K (2018) The effects of international tourism receipts on economic growth: evidence from the first 20 highest income earning countries from tourism in the world (1996–2016). Montenegrin J Econ 14(3):55–71

Pesaran MH (2004) General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. Cambridge Working Papers in Economics No: 0435. Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge

Pesaran MH (2006) Estimation and inference in large heterogeneous panels with a multifactor error structure. Econometrica 74(4):967–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2006.00692.x

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Pesaran MH (2007) A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. J Appl Econ 22:265–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.951

Pulido-Fernández JI, Cárdenas-García PJ (2021) Analyzing the bidirectional relationship between tourism growth and economic development. J Travel Res 60(3):583–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520922316

Ridderstaat J, Croes R, Nijkamp P (2016) The tourism development–quality of life nexus in a small island destination. J Travel Res 55(1):79–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514532372

Rivera MA (2017) The synergies between human development, economic growth, and tourism within a developing country: an empirical model for Ecuador. J Destination Mark Manag 6:221–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.04.002

Rosselló-Nadal J, He J (2020) Tourist arrivals versus tourist expenditures in modelling tourism demand. Tour Econ 26(8):1311–1326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619867810

Sajith GG, Malathi K (2020) Applicability of human development index for measuring economic well-being: a study on GDP and HDI indicators from Indian context. Indian Econom J 68(4):554–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019466221998620

Sharma M, Mohapatra G, Giri AK (2020) Beyond growth: does tourism promote human development in India? Evidence from time series analysis. J Asian Financ Econ Bus 7(12):693–702

Sharpley R, Telfer D (2015) Tourism and development: concepts and issues. Routledge, New York

Sindiga I (1999) Tourism and African development: change and challenge of tourism in Kenya. Ashgate, Leiden

Song H, Wu DC (2021) A critique of tourism-led economic growth studies. J Travel Res 61(4):719–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728752110185

Tan YT, Gan PT, Hussin MYM, Ramli N (2019) The relationship between human development, tourism and economic growth: evidence from Malaysia. Res World Econ 10(5):96–103. https://doi.org/10.5430/rwe.v10n5p96

Tang C, Abosedra S (2016) Does tourism expansion effectively spur economic growth in Morocco and Tunisia? Evidence from time series and panel data. J Policy Res Tour Leis Events 8(2):127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2015.1113980

Todaro MP, Smith SC (2020) Economic development. 13th Edition. Boston: Addison Wesley

Ulrich G, Ceddia MG, Leonard D, Tröster B (2018) Contribution of international ecotourism to comprehensive economic development and convergence in the Central American and Caribbean region. Appl Econ 50(33):3614–3629. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1430339

UNCTAD (2011) Fourth United Nations Conference on least developed countries. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UNDP (1990) Human Development Report 1990. Concept and measurement of human development.United Nations Development Programme, NY

UNDP (2023) Human Development Reports 2021/2022.United Nations Development Programme, NY

UNWTO (1980) Manila Declaration on World Tourism. United Nations World Tourism Organization, Madrid

UNWTO (2020) World Tourism Barometer. January 2020. United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Madrid

UNWTO (2022) World Tourism Barometer. January 2022. United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Madrid

UNWTO (2023) UNWTO Tourism Data Dashboard. United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Madrid

Wahyuningsih D, Yunaningsih A, Priadana MS, Wijaya A, Darma DC, Amalia S (2020) The dynamics of economic growth and development inequality in Borneo Island, Indonesia. J Appl Econom Sci 1(67):135–143. https://doi.org/10.14505/jaes.v15.1(67).12

World Bank (2023) World Bank Open Data. World Bank, Washington DC

Xia W, Doğan B, Shahzad U, Adedoyin FF, Popoola A, Bashir MA (2021) An empirical investigation of tourism-led growth hypothesis in the European countries: evidence from augmented mean group estimator. Port Econom J 21(2):239–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-021-00193-9

Yazdi SK (2019) Structural breaks, international tourism development and economic growth. Econom Res 32(1):1765–1776. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1638279

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, University of Jaén, Campus Las Lagunillas s/n, 23071, Jaén, Spain

Pablo Juan Cárdenas-García

GIDE, Faculty of Economics, Universidad de la República, Gonzalo Ramirez 1926, 11200, Montevideo, Uruguay

Juan Gabriel Brida & Verónica Segarra

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Author 1: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Author 2: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, validation, visualization. Author 3: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software, validation, writing original draft.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pablo Juan Cárdenas-García .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Researchdata-tourism+hdi, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cárdenas-García, P.J., Brida, J.G. & Segarra, V. Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: evidence from homogeneous panels of countries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11 , 308 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02826-8

Download citation

Received : 03 September 2023

Accepted : 13 February 2024

Published : 24 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02826-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, tourism research progress – a bibliometric analysis of tourism review publications.

Tourism Review

ISSN : 1660-5373

Article publication date: 16 June 2020

Issue publication date: 26 February 2021

Tourism review (TR) celebrates its 75th anniversary in 2020. The purpose of this paper is to proffer a holistic overview of TR based on bibliometric analyses of the publications from 2001 to 2019.

Design/methodology/approach

The research method entails performance analyses and science mapping analyses on TR. The performance analyses engage a sequence of bibliometric statistics, including citation analysis, most cited authors and papers, most influential and productive authors, countries and institutions to name a few. The authors also used visualization of similarities viewer to perform the science mapping analysis of TR based on co-citations of cited authors, bibliographic couplings of authors and countries and co-occurrences of authors’ keywords from 2001 to 2019 and from 2014 to 2019. To examine the thematic evolution using SciMAT, a de-duplicating process was conducted in which 1,485 keywords were refined to 128 word groups before thematic evolution map and strategic diagrams for the three sub-periods were generated.

The thematic evolution map revealed ten thematic areas. The key themes of each of these thematic areas are destination studies, tourism destination and hospitality tourism; destination studies, competitiveness and innovations, co-operations and experience tourism; business studies, sports tourism, tourism destination and satisfaction; quality studies, networks, social studies and co-operation; business model and sports tourism; tourism management and tourism destination; political studies, perception and satisfaction; political studies, sustainability studies, social studies and health tourism; behavior, perception and satisfaction; and cultural tourism and tourism destination.

Research limitations/implications

The study has managed to unveil the key trends of publications, authors, affiliations, nations and authors’ keywords. The findings are useful for potential authors to have a quick snapshot of what is expected from and what is happening in TR.

Originality/value

The study serves as a historical record of TR’s publications. It presents comprehensive bibliometric analyses of the publications in TR and identifying the key research trends.

Tourism Review(TR)将于2020年庆祝其成立75周年。本论文研究的目的是基于2001年至2019年出版的相关文献数量加以分析, 并对TR进行全面概述。

研究方法需要对TR进行性能分析和科学映射分析。绩效分析涉及一系列的文献数量统计, 包括引用分析:引用最多的作者和论文, 最具影响力和生产力的作者, 国家和机构。作者们还使用VOSviewer对引用作者的共同引用, 作者与国家/地区的书目耦合以及2001年至2019年以及2014年至2019年共同出现的作者关键词来进行TR的科学制图分析, 并使用SciMAT, 进行了重复数据删除过程, 将1485个关键字简化为128个词组, 进行随后三个阶段主题性的进化图与策略图的制作。

从2001年到2019年, TR的出版物和其引用率出现了巨大的飞跃, 因为它引起了全世界各项研究人员, 机构和国家的极大兴趣。被引用最多的文献和最有影响力的作者多来自发达国家的机构, 包括美国(US), 英国(UK)以及其他欧洲和大洋洲国家。但是, 亚洲和非洲大陆的国家也正在加入潮流, 并开始在TR中树立影响力。

该研究设法揭示了出版物, 作者, 隶属关系, 国家和作者的关键词的主要趋势。这些发现对于有潜能的作者快速了解TR预期和正在发生的事情很有帮助。

这项研究可作为TR出版物的历史记录。它将提供TR出版物的综合文献计量分析, 并确定了关键的研究趋势。

旅游期刊, 文献计量分析, 科学制图, 书目耦合, 共引, 共现, VOSviewer, SciMAT

Tourism Review (TR) celebra su 75 aniversario en 2020. El objetivo de esta investigación es ofrecer una visión global de TR basada en análisis bibliométricos de las publicaciones de 2001 a 2019.

Diseño / metodología / enfoque

el método de investigación implica análisis de rendimiento y análisis de mapeo científico en TR. Los análisis de desempeño involucran una secuencia de estadísticas bibliométricas, que incluyen análisis de citas, autores y artículos más citados, autores más influyentes y productivos, países e instituciones, por nombrar algunos. Los autores también utilizaron el VOSviewer para realizar el análisis de mapeo científico de TR basado en citas compartidas de autores citados, acoplamientos bibliográficos de autores y países y co-ocurrencias de las palabras clave de los autores desde 2001 hasta 2019 y desde 2014 hasta 2019. Para examinar el evolución temática utilizando SciMAT, se llevó a cabo un proceso de desduplicación en el que se refinaron 1485 palabras clave a 128 grupos de palabras antes de que se generaran mapas de evolución temáticos y diagramas estratégicos para los tres subperíodos.

hay un salto gigantesco en las publicaciones, así como las citas de TR de 2001 a 2019, ya que ha ganado mucho interés por parte de varios investigadores, instituciones y países de todo el mundo. La mayoría de los autores más citados e influyentes provienen de instituciones de países desarrollados, incluidos los Estados Unidos (EE. UU.), El Reino Unido (Reino Unido) y otras naciones europeas y de Oceanía. Sin embargo, países de los continentes asiático y africano se están uniendo al carro y comenzaron a establecer su influencia en TR.

Limitaciones / implicaciones de la investigación

el estudio ha logrado revelar las tendencias clave de publicaciones, autores, afiliaciones, naciones y palabras clave de los autores. Los hallazgos son útiles para que los autores potenciales tengan una instantánea rápida de lo que se espera de lo que está sucediendo en TR.

Originalidad / valor

el estudio sirve como un registro histórico de las publicaciones de TR. Presenta análisis bibliométricos exhaustivos de las publicaciones en TR e identifica las tendencias de investigación clave.

- Bibliometric analysis

- Science mapping

- Bibliographic coupling

- Co-citations

- Citation structure analysis

- Tourism journals

- Co-occurrence

- Revistas de turismo

- Análisis bibliométrico

- Mapeo científico

- Acoplamiento bibliográfico

- Co-ocurrencia

- Trabajo de investigación

Leong, L.-Y. , Hew, T.-S. , Tan, G.W.-H. , Ooi, K.-B. and Lee, V.-H. (2021), "Tourism research progress – a bibliometric analysis of tourism review publications", Tourism Review , Vol. 76 No. 1, pp. 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-11-2019-0449

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Tourism and economic growth: A global study on Granger causality and wavelet coherence

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Affiliation SLIIT Business School, Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology, Malabe, Sri Lanka

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Information Management, SLIIT Business School, Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology, Malabe, Sri Lanka

Roles Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft

- Chathuni Wijesekara,

- Chamath Tittagalla,

- Ashinsana Jayathilaka,

- Uvinya Ilukpotha,

- Ruwan Jayathilaka,

- Punmadara Jayasinghe

- Published: September 12, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386

- Reader Comments

This paper empirically investigates the relationship between tourism and economic growth by using a panel data cointegration test, Granger causality test and Wavelet coherence analysis at the global level. This analysis examines 105 nations utilising panel data from 2003 to 2020. The findings indicates that in most regions, tourism contributes significantly to economic growth and vice versa. Developing trade across most of the regions appears to be a major influencer in the study, as a bidirectional association exists between trade openness and economic growth. Additionally, all regions other than the American region showed a one-way association between gross capital formation and economic growth. Therefore, it is crucial to highlight that using initiatives to increase demand would advance tourism while also boosting the economy.

Citation: Wijesekara C, Tittagalla C, Jayathilaka A, Ilukpotha U, Jayathilaka R, Jayasinghe P (2022) Tourism and economic growth: A global study on Granger causality and wavelet coherence. PLoS ONE 17(9): e0274386. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386

Editor: Vu Quang Trinh, Newcastle University Business School, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: July 18, 2022; Accepted: August 26, 2022; Published: September 12, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Wijesekara et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its with Supporting information files.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Tourism is one of the world’s major industries, and people have been travelling for pleasure since the dawn of time. It has become one of the fastest expanding sectors of the global economy in recent years. Tourism arose as a result of modernisation and contributed significantly to shaping the experience of modernity. Economic growth and tourism development are intertwined, according to previous literature, therefore, an increase in the general economy will support tourism development [ 1 ]. As a result, it’s critical to investigate how tourism and other factors (including macroeconomic) are linked to economic growth. Economic growth can be defined as an increase in the real gross domestic product (GDP) or GDP per capita. Global tourism, as a key contributory business, has contributed to approximately 10% of global GDP through possible employment opportunities, extending client markets, encouraging export trades, and gains from foreign exchanges [ 2 , 3 ]. Another study that looked at the relationship between tourism and economic growth using variables like tourist receipts and tourism spending added to the literature by suggesting that tourism receipts impacted economic growth [ 4 ]. Additionally, according to Marin [ 5 ], tourism receipts have an upward link to the country’s economy and can thus aid in economic growth. Globally developed tourism business fosters economic growth over time, supporting the economy more than anticipated.

In recent years, research studies analysing the direction of the relationship between economic growth and tourism have been a popular area of interest in literature. A study of 12 Mediterranean nations in 2015 demonstrated a bidirectional causality relationship between tourism development and economic growth [ 6 ]. In a study conducted in Romania [ 7 ], a bidirectional causal relationship exists between GDP and the number of international tourist arrivals, whereas in an African study, a unidirectional causal relationship exists between international tourism earnings and real GDP, both in the short and long run [ 8 ]. According to previous research, this link appears to be both unidirectional and bidirectional.