- Donor Selection Guidelines /

- Geographical Disease Risk Index /

- Latest Updates

- Version Information

- Introduction

- Document and Change Control

- General Principles

- Use of this Index

- DSG cross-reference

- Source Files

Information concerning malaria risk has been sourced from Health Protection Scotland ( www.travax.nhs.uk/ ) with some modifications to account for typical donor travel patterns, entry points to the countries concerned, areas where reporting is compromised and ease of use for end users. They are not identical to those found on the ‘Fit for Travel’ website which is designed to inform travellers decisions about anti-malarial therapy rather than give assurance of safety of blood donations for recipient patients.

Countries with malarial risk have been categorised into three groups:

A. Countries where the malarial risk is present in the whole country all year or with very clear seasonal guidance.

B. Countries where only parts of the country are affected.

C. Indicates that only part of the country is affected in discrete pockets, or the risk of infection is low or that there are few visitors to the affected areas. It is likely that tourists who visit these countries will be able to donate but individual assessment must be applied. Donors are likely to have detailed knowledge of the malarial areas visited. The health care professional should establish whether the donor sought advice prior to travel or not and if they were advised to take anti malarial precautions.

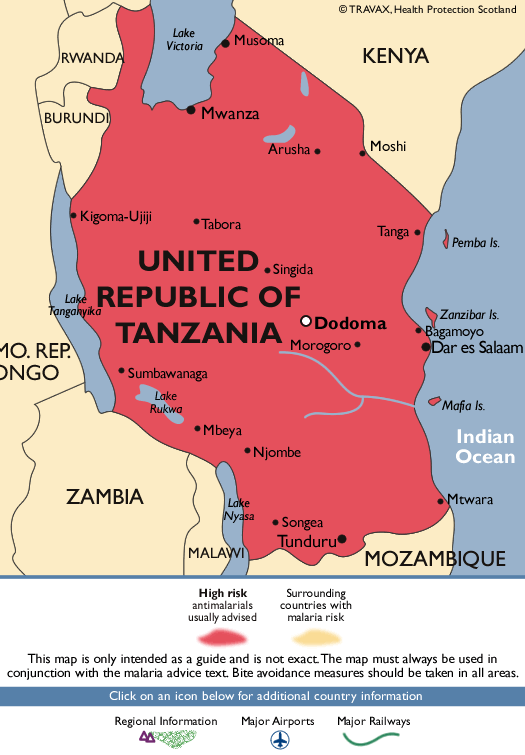

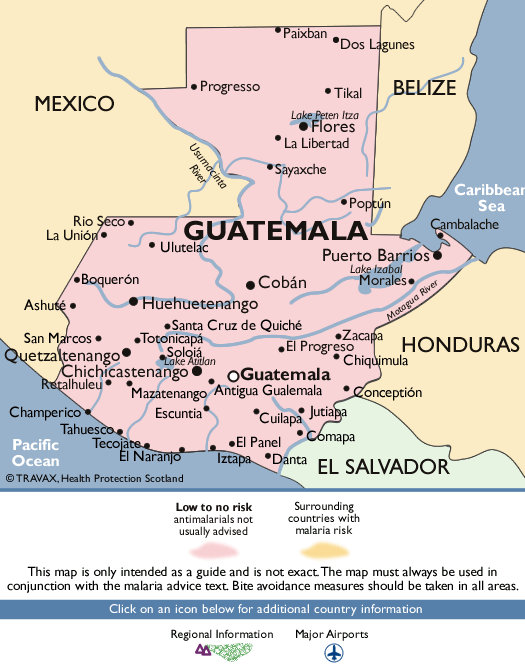

Malaria Maps

The maps included are to be used to accompany the GDRI when assessing the malaria risk for a donor. They have been sourced from the Fit for travel website. It is important to apply the GDRI guidance for all infection risks; these maps only provide advice for malaria risk.

Use Of Maps

Maps are provided to allow staff to assess the malaria risk for the areas within these countries that a donor has visited. The text of the GDRI should be taken as the main source to make decisions. The maps present information about neighbouring countries but this should not be used for malarial assessment. The advice below each map relates to the Fit for travel website. Decisions regarding malaria guidance should be made using the template below.

The colours used in the maps are presented below.

All maps were downloaded from the Fit for travel website ( www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk )

Airport Stopovers

The definition of an Airport Stopover, as approved by The Standing Advisory Committee on Transfusion Transmitted Infections, is: A transit through an airport during which the traveller has not left the airport.

When the donor's visit has consisted only of an airport stopover there is no need to refer to the Geographical Disease Risk Index.

This section was last updated in GDRI Edition 002, Release 24, Issue 01

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ther Adv Infect Dis

- v.8; Jan-Dec 2021

An update on prevention of malaria in travelers

Nelson iván agudelo higuita.

Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, 800 Stanton L. Young Blvd., Suite 7300, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA

Bryan Pinckney White

Infectious Diseases Clinical Pharmacist, Oklahoma University Medical Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA

Carlos Franco-Paredes

Department of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

Miranda Ann McGhee

Malaria, a parasitic disease caused by protozoa belonging to the genus Plasmodium , continues to represent a formidable public health challenge. Despite being a preventable disease, cases reported among travelers have continued to increase in recent decades. Protection of travelers against malaria, a potentially life-threatening disease, is of paramount importance, and it is therefore necessary for healthcare professionals to be up to date with the most recent recommendations. The present review provides an update of the existent measures for malaria prevention among travelers.

Introduction

Malaria is a parasitic disease caused by protozoa belonging to the genus Plasmodium . There are four species that exclusively affect humans: Plasmodium falciparum , Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale, and Plasmodium malariae. Plasmodium species that commonly infect non-human primates can also be responsible for a high proportion of human cases in certain parts of the world as is the case with Plasmodium knowlesi in southeast Asia and Plasmodium simium in Brazil. 1 – 4 All species of malaria are transmitted by the bite of an infective female Anopheles mosquito. Malaria can be also transmitted through blood transfusion, needle sharing, laboratory accidents, organ transplantation, and congenitally from mother to fetus. 5 , 6

Malaria continues to represent a formidable public health challenge. According to the most recent World Malaria Report published in 2020, there were an estimated 229 million cases of malaria worldwide in 2019 with 94% reported from the African region and mostly affecting children younger than 5 years of age. There were an estimated 409,000 deaths globally, with 95% occurring in sub-Saharan Africa. 7 Although there has been progress in reducing the global prevalence and mortality attributable to malaria, the number of cases reported among travelers in the United States (US) has continued to have a stepwise increase of approximately 29.4 cases per year since 1972. 6 A total of 2161 confirmed malaria cases were reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2017, a 4% relative increase in confirmed cases compared with 2016 and the highest in 45 years. Most cases originated from West Africa (66.9%) and P. falciparum accounted for the majority of infections (70.5%). Most of the cases of malaria affected travelers who were visiting friends and relatives (VFR traveler) and only about a quarter of US residents with malaria reported taking any form of chemoprophylaxis. There were 27 pregnant women affected, of which 22 were hospitalized. Ten of the pregnant women were US residents, and none took prophylaxis to prevent malaria. 6

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar for articles published up to June 30, 2021 with emphasis in the last 2 decades, using the terms ‘malaria,’ in combination with ‘traveler,’ ‘protection,’ ‘prophylaxis,’ ‘prevention.’ We reviewed these articles, and relevant articles in the references of these articles. Only articles published in English were included.

Clinical presentation

The severity of clinical manifestations due to malaria is primarily determined by previous exposures to Plasmodium spp. and the resulting immune status (i.e. premunition). The degree of parasitemia also plays a significant role in the pathogenetic mechanisms of the infection in the microvasculature. The ability of P. falciparum and, to a lesser degree, P. knowlesi to infect most stages of the lifespan of red cells correlates with higher levels of parasitemia and worse outcomes. Reports of life-threatening malaria caused by P. vivax are increasing in certain areas of the world, with thrombocytopenia being a potential marker of severity that requires further validation. 8 , 9 Most travelers are considered non-immune to malaria and symptomatic disease is therefore seen across all age groups. The incubation period is of approximately 2 weeks for malaria caused by P. falciparum , P. knowlesi , and P. vivax . For P. ovale and P. malariae , the incubation period is of about 2–3 weeks and 18–35 days, respectively. 10 – 13 Temperate climate P. vivax ( P. vivax var hibernans ) was of great importance until the middle of last century and was characterized by long incubation periods of up to 8–10 months. Temperate climate P. vivax malaria is still endemic in the Korean peninsula. 14 – 16

The incubation period can also be altered (i.e. prolonged) by agents used for chemoprophylaxis and by antibiotics that are not commonly used to prevent or treat malaria such as rifampin, azithromycin, and ciprofloxacin. 17 – 19 Malaria can present as early as 1 week after the initial exposure and as late as several years after leaving a malaria zone irrespective of chemoprophylaxis use. This is especially true with P. vivax or P. ovale when no liver stage schizonticide is taken as part of prophylaxis. 13 , 18 , 19

The presentation of malaria can be vague and nonspecific. Fever, malaise, headache, chills, and sweats are common but gastrointestinal and respiratory complaints may predominate. Fever in a returning traveler should be considered a medical emergency and expedited evaluation for life-threatening infections is mandatory. Failure to consider the diagnosis of malaria is not infrequent and the diagnosis can be difficult, as fever is not always present during the initial evaluation. If the first blood films are negative, both thick and thin blood films or rapid diagnostics should be repeated twice 8–24 h apart. 13 , 19

There are no pathognomonic physical exam findings for malaria but several variables could be used to predict a higher likelihood of the disease. Splenomegaly, fever, a white blood cell count <10,000 cells/l, platelet count <150,000/μl, hemoglobin <12 g/dl, eosinophils <5%, and hyperbilirubinemia have been associated with parasitemia. 20 , 21 Malaria is a notifiable disease in every state of the United States.

Educating the traveler

The risk of acquiring malaria is determined by a variety of factors inherent to the traveler, itinerary, and the geographic area being visited. The risk assessment should be therefore individualized and ideally occur at least 4–6 weeks before departure.

Malaria is endemic in 90 countries and territories ( Figure 1 ) and its transmission is usually continuous throughout the year in tropical regions and seasonal in temperate zones of the world. The intensity and extent of transmission within a country varies and may be focal. 7 , 22 There are several resources with country-specific data regarding malaria transmission to help clinicians with decision making. It is important to note that despite the great value offered by these resources, reliable data on area-specific risks within a predetermined region/country is difficult to predict 23 and that several professional organizations publish recommendations that differ, sometimes to a great extent. In general, studies have shown that the highest risk of malaria transmission occurs in sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea. 6 , 24 – 27 Chemoprophylaxis should be therefore prescribed routinely to travelers visiting these regions, Pakistan and India, regardless of whether they will be visiting an urban or rural setting. It is important to note that most, but not all, urban and tourist destinations in southeast Asia, Central and South America do not have sufficient risk of malaria transmission to warrant routine prophylaxis. 27 , 28

Malaria-endemic countries.

Certain populations are at higher risk of acquiring the disease or suffering from its complications. Immigrants who have settled in developed countries and return to their home countries as VFR travelers are highly vulnerable. 6 , 23 , 26 Some of the factors that affect a VFR’s risk of illness include beliefs that they are immune to diseases that they might have acquired during childhood (e.g. malaria), access and trust of the healthcare (e.g. asylum seekers and new immigrants), lack of awareness of the risks associated with travel, cost, and language barriers among others. 29 , 30 Pregnant women are at high risk of developing potentially fatal complications related to malaria. 31 Women who are pregnant or who are likely to become pregnant should be advised against travel to malaria-endemic zones, as there is no chemoprophylactic regimen that is completely effective (see section 8.2 for more details).

There are many other aspects that need to be considered when determining the risk of acquisition of malaria. These include the length and season of the trip, rural versus urban setting, altitude of the destination, accommodation characteristics, outdoor exposure during night-time hours in locations with considerable exposure to mosquitoes, and adherence to mosquito avoidance precautions and chemoprophylaxis. 23 Travel health practitioners need to inform travelers of the life-threatening nature of malaria infection and the importance of prevention.

Personal protection measures

Anopheles spp. feed mainly between dawn and dusk, and measures to decrease exposure during this time is of paramount importance. Contact with mosquitoes can be reduced by the use of screened accommodations and mosquito bed nets (preferably insecticide impregnated), appropriate application of repellents, and wearing clothes that cover most of the body. 23 , 32 – 34

A wide array of popular devices designed to repel mosquitoes are available on the market. A few examples include coils, candles, and heat-generating devices. The effectiveness of these devices is not supported by robust studies and should therefore be used with the addition of proven measures. 34

In general, topical repellents can be divided into synthetic chemicals and plant-derived essential oils. 35 , 36 The best-known chemical insect repellents are N, N -diethyl- m -toluamide, also known as N, N -diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET), and picaridin. Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or PMD (chemical name: para-mentahne-3,8 diol), IR3535 [chemical name: 3-( N -butyl- N -acetyl)-aminopropionic acid, ethyl ester], and 2-undecanone are considered either derivatives or synthetic products of natural materials. 33 , 34

The efficacy and duration of protection are subject to factors such as ambient temperature and humidity, degree of perspiration and level of activity, exposure to water and other variables. The degree of protection to a determined species of mosquito or tick varies according to the active ingredient and the duration of protection is proportional to the concentration of the product. 33 , 34 For DEET, picaridin, and IR3535, a concentration of at least 20% and for PMD 30% is recommended. Most repellents can be used on children aged >2 months with the exception of OLE, which should not be used on children aged <3 years. No additional precautions for using registered repellents on children or pregnant or lactating women are otherwise needed. 33 , 34 It is also important to remember that DEET can have an unpleasant odor for some and can dissolve plastic. In addition, the sunscreen and repellent should be used as separate products and the sunscreen should be applied first.

The Environmental Protection Agency reviews and approves repellents based on efficacy and human safety. A repellency awareness graphic is available on the labels of insect repellents. More information is available on the following website: www.epa.gov/insect-repellents/repellency-awareness-graphic .

Chemoprophylactic agents

Please refer to Table 1 for doses and schemes used for the different drugs.

Chemoprophylactic agents in malaria.

CrCl, creatinine clearance; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Atovaquone/proguanil

Atovaquone inhibits the parasitic electron transport. Proguanil is metabolized through CYP2C19 to cycloguanil, which acts a parasitic dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor. 37 The drug’s synergistic effect is caused by proguanil’s ability to increase atovaquone activity to collapse the mitochondrial membrane potential. 38 Atovaquone is poorly absorbed, with bioavailability reaching 23% when taken with food. It is extensively protein bound (>99%) and is primarily (94%) hepatically eliminated with limited metabolism. It has a half-life of 55.9 h with multiple doses. 37 Proguanil is extensively absorbed regardless of food with a bioavailability of 60–75%. Approximately 40–60% of proguanil is excreted renally with a half-life of 12–21 h. 38

Studies have shown a 96–100% protection efficacy against P. falciparum . The medication is well tolerated with the most common side effects reported being abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and headache. Abbreviated regimens have been examined in an attempt to improve compliance. The doses used for the treatment of malaria (four tablets daily for 3 consecutive days) provides protection against malaria for >4 weeks. A study done in Australia examined the efficacy of this regimen in adults traveling to malaria-endemic areas with low-to-medium risk for up to 4 weeks. Most participants complied with the regimen, although 43.3% reported side effects. No traveler developed malaria, although the study was not designed and did not have the statistical power to determine effectiveness. 39 An observational study designed to detect prophylactic failure with a twice-weekly regimen of atovaquone/proguanil among long-term expatriates (⩾6 months) in West Africa found no cases of malaria. In comparison, the malaria rates were 11.7/1000 person-months in the group taking no prophylaxis, and 2.06/1000 person-months in the group taking weekly mefloquine. 40 Other investigators have examined and concluded that discontinuation of the medication 1 day after return as opposed to the 7 days did not alter efficacy. 41 Despite these promising results, a modified regimen of atovaquone/proguanil needs to be supported by more robust data from clinical trials with a larger sample size and higher-risk destinations. 42

Doxycycline

Doxycycline inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit. Doxycycline may also inhibit dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, a mitochondrial enzyme involved in pyrimidine synthesis. 43 Doxycycline is almost completely absorbed in the duodenum with a bioavailability of 95%. Food decreases absorption by 20%. The volume of distribution is 0.7 l/kg with protein binding of 82–93%. It achieves high concentrations in the liver and it is excreted unchanged with 35–60% in the urine and the rest in feces. 44

Doxycycline has an efficacy between 92% and 96% for P. falciparum and 98% for primary P. vivax infection. The most common side effects are photosensitivity, nausea, vomiting, and an increased frequency of vaginal yeast infections. 45 The medication should be taken with at least 8 oz of water while in an upright position and not just before going to bed, to avoid esophagitis. Doxycycline monohydrate or enteric-coated doxycycline hyclate are better tolerated than generic doxycycline hyclate. It is also common practice to prescribe 150 mg of fluconazole for women that intend to use the medication as a standby treatment for vaginal candidiasis. There are insufficient data to make recommendations regarding the interchangeability between doxycycline and minocycline for this indication. Minocycline should be stopped 1–2 days before travel for those taking it chronically and be replaced with doxycycline. The minocycline can be resumed once the course of doxycycline has been completed. 45

The exact mechanism of action is unknown but protein synthesis inhibition has been hypothesized. 46 Mefloquine is well absorbed with a bioavailability of 87–89%. It has high protein binding of 98%, with a mean volume of distribution of 22 l. 47 Mefloquine is metabolized by CYP3A4 into carboxymefloquine, an inactive metabolite. 48 Its terminal half-life is 14–21 days with primarily bile and feces elimination. 47

Controversy has surrounded the use of this agent due to its safety profile. 49 , 50 Mefloquine has been associated with a lengthy list of side effects including gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, and dizziness. More severe neuropsychiatric side effects such as visual disturbances, severe depression leading to suicide, sensory and motor neuropathies, memory deficits, hallucinations, aggression, seizures, psychosis, irreversible vertigo, and encephalopathy have been reported. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black-box warning in 2013 about the risk of neuropsychiatric side effects. In the US, any traveler receiving a prescription for mefloquine must also receive a copy of the FDA medication guide, which can be found at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/019591s023lbl.pdf . 51 The European Medicines Agency updated the product information and mandated that all European Union members ensure that healthcare professionals are aware and communicate to their patients the risk neuropsychiatric and other adverse events. In addition, it was stipulated that only travelers without a contraindication to the medication receive a prescription and that the traveler carry an alert card at all times. 52

The risk of developing severe or disabling neuropsychiatric side effects ranges from 1/607 to 1/20,000 compared with a rate for chloroquine of 1/1181 to 1/13,600. 50 Mefloquine is contraindicated in the setting of allergy to the medication or related compounds (e.g. quinine) or any excipient. Active or recent history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia, convulsions, cardiac conduction abnormalities and treatment with halofantrine or ketoconazole are also contraindications. 52

Mefloquine is an ideal chemoprophylactic agent for long-term travelers, children, and pregnant women, but due to the potential toxicities, it should be reserved when other agents are contraindicated and for areas with high malaria risk such as sub-Saharan African and parts of Oceania.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine’s exact mechanism of action is unknown. They are thought to concentrate in lysosomes and interfere with parasitic processing of hemoglobin. 53 Chloroquine has a bioavailability of 89%. Hydroxychloroquine has a bioavailability of 74%. The pharmacokinetics of these drugs are complex, with a large volume of distribution (greater than 50,000 l has been reported), three-compartment pharmacokinetics, and reported half-lives of over 100 days. They both concentrate in the liver. Approximately 23–38% is excreted unchanged in the urine, 17–18% is excreted as metabolites in the urine, with the remainder being excreted in feces or stored long term in lean tissues. 54

The medication is well tolerated with the most common reported side effects being gastrointestinal disturbances, dizziness, blurred vision, insomnia, and pruritus. The medication can exacerbate psoriasis, and although rare in the doses used for prophylaxis, retinopathy can occur. The medication is safe in pregnancy. 51

The exact mechanism of action of primaquine is unknown. Possible mechanisms are impeding mitochondrial metabolism or oxidative stress. It is rapidly absorbed with a plasma peak in 1–3 h and a volume of distribution of 3 l/kg. It accumulates in the brain, liver, skeletal muscle, lungs, and heart. Primaquine is metabolized into carboxyprimaquine and other metabolites, by oxidases and dehydrogenases. Less than 5% is eliminated unchanged in the urine. 55

Primaquine phosphate has two roles in prevention. It can be used as a causal prophylactic agent against all Plasmodium spp . and for presumptive anti-relapse therapy (PART), also known as terminal prophylaxis, for P. vivax and P. ovale . The dosing should overlap with the blood schizonticide and therefore when chloroquine, doxycycline, or mefloquine are used for primary prophylaxis, primaquine is usually taken during the last 2 weeks of postexposure prophylaxis. When atovaquone–proguanil is used for prophylaxis, primaquine may be taken during the final 7 days of atovaquone–proguanil, and then for an additional 7 days. Primaquine should be given concurrently with the primary prophylaxis medication. However, if that is not feasible, the primaquine course in the form of terminal prophylaxis should still be administered after the primary prophylaxis medication has been completed. 56 Terminal prophylaxis with primaquine (or tafenoquine, see below) is particularly important for long-term travelers returning from highly endemic areas of P. vivax transmission in the Pacific Islands (i.e. Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, and Solomon Islands) or among those returning from countries that constitute the Horn of Africa.

The efficacy for prophylaxis is considered to be over 85% against P. falciparum and P. vivax and around 95% when used for PART. The most common side effects are abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Severe hemolysis in persons with glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency and methemoglobinemia can occur. The medication is contraindicated in the setting of G6PD deficiency, nicotinamide dehydrogenase methemoglobin reductase deficiency, pregnancy, known hypersensitivity to primaquine, and illnesses that manifest with tendency for granulocytopenia. A G6PD testing should be performed before use of the medication. 56

Tafenoquine

Tafenoquine’s exact mechanism of action is unknown. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to Plasmodium spp. death. Absorption is slow and increased with a high-fat meal. It is extensively (>99.5%) protein bound with a volume of distribution of 1600 l. The terminal half-life is 15 days. It is thought to be excreted unchanged, but complete information on excretion is unknown. 57

Tafenoquine succinate is formulated as either a 100 mg or 150 mg tablet. The medication has been approved by the FDA and in Australia for the primary prevention of malaria for persons aged ⩾18 years and for the radical cure of P. vivax in persons older than 16 years of age. 57 – 59 It is important to note that the medication is approved in two separate formulations from two different manufacturers. The 60° Pharmaceuticals manufacture Arakoda ® and Kodatef ® for causal prophylaxis in the US and Australia, respectively. In a partnership with Medicines for Malaria Venture, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) manufactures Krintafel ® and Kozenis ® for radical cure of P. vivax , also in the US and Australia, respectively. Tafenoquine is also licensed for PART. For P. ovale , tafenoquine can be used off label for radical cure. 60 – 62

Tafenoquine has only been studied for radical cure of P. vivax malaria when used with chloroquine, and the medication should therefore be co-administered with chloroquine only. CDC continues to recommend the off-label use of tafenoquine for radical cure of P. ovale and like with P. vivax , it should be co-administered with chloroquine only.

Tafenoquine has a half-life of approximately 2 weeks allowing weekly administration for primary prophylaxis after a loading dose and one dose when used for radical cure. When used for primary prophylaxis, the medication is taken at a dose of 200 mg daily for 3 days prior to travel, weekly during travel, and then once after return. The last dose should be taken 7 days after the last maintenance dose while in the malaria-endemic area. For the radical cure of P. vivax , the dose is 300 mg once. 57 , 58 The efficacy of the medication for causal prophylaxis varies between 86% and 100%. The malaria recurrence-free rate at 6 months ranges from 62% to 89%. 58

The medication is contraindicated in G6PD-deficient individuals. Quantitative G6PD testing (rather than qualitative, which is usually appropriate for primaquine use) is required, which might logistically be difficult to accomplish for last-minute travelers. 63 , 64 The medication is contraindicated in pregnancy and in breastfeeding women if the infant has G6PD deficiency or if the infant’s G6PD status is unknown. Its safety in children has not been established. 58

Malaria standby emergency treatment (SBET)

The concept describes the self-administration of emergent malaria treatment brought from the country of origin for use when no medical attention is available or for use after the diagnosis has been established. The topic is controversial and the appropriate setting for its use varies according to different national guidelines. 65 There is great variation in the proportion of travelers that appropriately use this strategy as response to the development of fever which is of primordial importance given the life-threatening nature of the disease. 66

For travelers taking chemoprophylaxis and for whom SBET is prescribed, the drug that is being used for chemoprophylaxis should not be used for treatment. Once treatment is completed, chemoprophylaxis should be resumed. If atovaquone/proguanil is being used, it can be resumed immediately after treatment. If another agent is being used, it can be resumed 1 week after completion of treatment. Atovaquone/proguanil and artemether/lumefantrine, two regimens approved in the US, can be used for SBET. Artemether/lumefantrine can be used during pregnancy. 67 , 68 The medications should be bought and taken from the country of origin, given the high rates of counterfeit in malaria-endemic countries. 51 Mefloquine should be avoided for this indication given the potential toxicity. In addition, artemether/lumefantrine should not be used for SBET if mefloquine is being used for chemoprophylaxis. 51 Other regimens such as the combination of doxycycline and quinine require multiple doses which are frequently associated with side effects.

SBET alone can be considered if traveling to low malaria transmission areas such as most of southeast Asia and South America. If possible, SBET should only be considered when traveling to remote areas where medical attention is hampered by a lack of medical services, or quality medications and access to a medical evaluation is not readily available within 24 h. 65 It is important to emphasize to the traveler that the development of fever requires immediate evaluation regardless of SBET use.

Vaccines have not been approved for the prevention of malaria among travelers. The RTS,S/AS01 vaccine has been studied in two phase III trials in Africa with ages ranging from 5–17 months. 69 – 71 The largest malaria vaccine trial done in Africa included 15,459 infants and young children and showed that the vaccine prevented 39% of cases of malaria and 29% of cases of severe malaria over a 4-year follow-up period. For those that received four doses, 1774 cases of malaria were prevented for every 1000 children vaccinated. Efficacy waned with time. 69 A recommendation to include the vaccine in the national immunization programs has not been made, and a pilot study is currently underway in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi. 72 Although vaccines can have a great impact in achieving the goals of malaria eradication, further research is needed to be considered ideal for travelers. 73

Choosing an antimalarial agent for chemoprophylaxis

The choice of a chemoprophylactic agent ( Tables 2 2 – 4 ) requires consideration of several factors such as the travel destination, layovers, season, length of travel, traveler’s health, potential side effects and medication interactions, preference, and cost.

Cost of malaria chemoprophylaxis for adults for one week of travel, including required pre- and post-travel dosing. Prices obtained from GoodRx ( https://www.goodrx.com/ ).

US, United States.

Advantages and disadvantages of malaria chemoprophylaxis.

G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; US, United States.

Drug interactions with malaria chemoprophylaxis agents. 74

B-blockers, beta blockers; US, United States.

P. falciparum has developed resistance to all antimalarials, and knowledge about its geographic distribution is important in decision making. 51 , 75 Resistance to chloroquine was first observed in southeast Asia and South America in the 1950s and subsequently spread to most parts of the world excluding the Caribbean and Central America, west of the Panama Canal. 76 Resistance is the result of a point mutation in the PfCRT protein that localizes to the digestive vacuole of the Plasmodium spp. This results in the inability of chloroquine to concentrate within the digestive vacuole and form complexes with toxic heme moieties that interfere with detoxification mechanisms. 77 – 80

Resistance of P. vivax to chloroquine was documented in 1989 when Australians repatriated from Papua New Guinea failed routine treatment. 81 Subsequent reports from Indonesia, Myanmar, and India corroborated findings. 82 The cause of resistance in P. vivax remains elusive due to the nature of the parasite’s dormant phase in the liver, low parasitemia, and difficulty in distinguishing relapse, recrudescence, and reinfection. 83

Special populations

Infants, children, and adolescents.

Prevention recommendations for malaria in children are similar to that in adults and include assessment of risk based on travel itinerary, education of mosquito avoidance, determination of chemoprophylaxis, and educating parents to seek early medical care if fever develops during or soon after travel. 84 All chemoprophylactic agents used in adults, with the exception of tafenoquine, are available for children. There are several observations to remember: atovaquone/proguanil should not be administered to children weighing less than 5 kg and doxycycline in those younger than 8 years of age. The product’s label should be carefully followed for pediatric dosing of malarial chemoprophylaxis. Due to difficulty in pediatric dosing, pulverizing tablets into specified dosing can be done, with the assistance of a pharmacist. Due to bitter taste, medications can be mixed into or crushed into food. Specific contraindication for use of repellents in children was described earlier in this document.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Pregnant women are particularly susceptible to malaria infection due to immunologic changes that occur during pregnancy. P. falciparum can concentrate in the placenta and lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm birth, and low birth weight. 85 – 87 Congenital infection with detectable parasitemia from 24 h to 7 days of life is another important complication. 88 – 90

Pregnant women should be advised not to travel, if at all possible, as no chemoprophylactic regimen is 100% effective. For women that chose to travel to a malaria-endemic region, emphasis on mosquito avoidance measures and chemoprophylaxis should be provided. In the US, malaria chemoprophylaxis in pregnancy is limited to mefloquine and chloroquine.

In some countries, atovaquone/proguanil is used for either treatment or prophylaxis of malaria during pregnancy. Although the available safety data for its use in pregnancy are reassuring, well-established trials are needed before a definite recommendation can be made. 91 , 92 Doxycycline is also used during the first trimester in several European countries if there are compelling reasons for chemoprophylaxis and if no alternative is available. It is important to remember that doxycycline needs to be administered for 4 weeks after return from a malaria-endemic region. 93

In all women of childbearing age, plans for conception during travel should be discussed. All breastfeeding mothers should be counseled that maternal use of chemoprophylaxis does not provide protection to a breastfed infant, as only a limited amount of medication is secreted in the breastmilk. All chemoprophylactic agents can be administered to breastfeeding mothers except primaquine and tafenoquine, unless G6PD deficiency has been excluded in both the mother and newborn.

Immunosuppressed travelers

Immunosuppressed patients, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), are more likely to develop severe malaria. 22 Immunosuppressed travelers should be provided chemoprophylaxis similarly to those who are immunocompetent, with additional consideration of the possibility of drug interactions.

Interactions with malaria prophylaxis are primarily seen with cancer-related therapies, anti-rejection medications used after transplantation, and medications used to treat HIV ( Table 4 ). Drug interactions related to anti-retrovirals can be checked on the University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions website ( https://www.hiv-druginteractions.org/ ). Typical cancer-directed therapies that can result in interactions include the use of tamoxifen with chloroquine that results in an increased risk of retinopathy, increased levels of platinum-based chemotherapies with tafenoquine, and increased levels of methotrexate when used with doxycycline. In those who have undergone transplantation, chloroquine can increase cyclosporine levels. In travelers with HIV, interactions occur primarily with protease-inhibitor-based regimens and with some non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors such as efavirenz, nevirapine, and etravirine. 74 , 94

Long-term travelers

A long-term traveler is a person visiting a malaria-endemic region for longer than 6 months. Long-term travelers represent a high-risk group, as they tend to underuse personal protective equipment and adhere poorly to anti-malaria prophylaxis. 32

Chloroquine has a good safety record for the treatment of rheumatologic conditions, suggesting it can be used for long-term malaria prophylaxis. For long-term use (>5 years) of chloroquine, a baseline eye examination with bi-annual follow up is recommended to screen for potential retinal toxicity. 51 Long-term mefloquine use is shown to be safe. Tolerability has been variable and related to neuropsychiatric events that usually occur early in the course of prophylaxis. 32 , 95 , 96 Atovaquone/proguanil has been used up to a duration of 34 weeks with good tolerability, with diarrhea being the primary side effect. 97

The tolerability of doxycycline was evaluated in a study of 600 military personnel in Cambodia for 1 year and 900 men deployed to Somalia for 4 months. The medication was well tolerated, with gastrointestinal events and photosensitivity being the most common reported side effects. 98 Another study with 228 US Peace Corps volunteers who took doxycycline prophylaxis for an average of 19 months showed a similar side-effect profile. 99 Doxycycline is approved by the FDA for a duration of 4 months. The use of primaquine for up to 52 weeks is safe with mild non-clinically significant methemoglobinemia being the most common side effect. 100

Relapse prevention

PART is an intervention used to eradicate the quiescent liver hypnozoites of P. vivax or P. ovale with medications such as primaquine and tafenoquine. Primaquine is FDA approved at a dose of 0.25 mg/kg (15 mg base) daily for 14 days. 51 The World Health Organization guidelines recommend a higher dose of primaquine (0.5 mg/kg or 30 mg base daily for 14 days) for strains of P. vivax acquired in East Asia and Oceania, 101 and CDC recommends the higher dose regardless of geographic site of acquisition. 51 Tafenoquine should be administered as a single 300 mg dose and it should ideally overlap with blood-stage treatment or the last dose of prophylaxis. If this is not feasible, tafenoquine may be taken as soon as possible afterward. 62

The use of PART is appropriate for travelers that have visited P. vivax -endemic areas, even if P. falciparum is present, and especially for prolonged stays. 50 It is important to remember that if either primaquine or tafenoquine are used as prophylactic agents, PART is not needed.

There are several important caveats with the use primaquine. Adherence to a 14-day course is poor, and life-threatening hemolytic reactions may occur if G6PD deficiency is not recognized. To address the first limitation, two randomized controlled trials in G6PD-normal patients compared a shorter primaquine regimen consisting of 1 mg/kg day for 7 days with high-dose primaquine for 14 days. Both studies showed no difference in efficacy between the 7-day and 14-day course. However, there were more side effects reported in the 7-day arm in one of the studies. 102 , 103

Blood donation

Transfusion-transmitted malaria was first described in the turn of last century and is an important form of transmission in malaria-endemic areas. 104 A recent review concluded that the median worldwide prevalence of malaria parasitemia in healthy blood donors was 10.54% by microscopy, 5.36% by molecular techniques, and 0.38% by rapid diagnostic tests. 105

Storage of blood under refrigeration is deleterious to Plasmodium spp. Refrigeration at 4°C decreases parasitemia rapidly, nonetheless Plasmodium falciparum has been shown to survive in stored whole blood or plasma at this temperature for approximately 18 days and can remain microscopically detectable for up to 28 days when frozen but with diminished infectivity. 106

The incubation period of transfusion-transmitted malaria is longer than mosquito-transmitted malaria which could lead to a lack of suspicion and delay in the diagnosis of the disease; especially in non-endemic regions. 104 A study that examined transfusion-transmitted malaria in the US between 1963 and 1999 found that the median incubation period was 10 days but ranged from 1 to 180 days. 107

As of April of 2020, the FDA recommends that non-resident travelers of an endemic country or those who are residents of an endemic country but have lived in a non-endemic region for more than 3 consecutive years and are returning from malaria-endemic areas defer blood donation for 3 months after arrival as opposed to 1 year as was previously recommended. This group does not necessarily need to defer donation, as pathogen reduction techniques could be used and allow the collection of components from otherwise-eligible donors. For former residents of malaria-endemic regions that have lived in a non-endemic region for less than 3 consecutive years and for people that have been diagnosed with malaria, donation of blood products should be deferred for 3 years, and this recommendation remains unaltered in the most recent update. 108

The prevention of malaria in travelers continues to be challenging. A multitude of factors determine the risk of malaria acquisition among travelers. The knowledge of such factors and the available preventive measures are of vital importance in being able to provide evidence-based recommendations to travelers. This knowledge should not be restricted to specialized travel medicine professionals as a significant percentage of travelers seek attention from general practitioners. It is therefore imperative for practitioners to be familiar with the most recent guidance and available resources (e.g. internet based, specialized travel clinics available in the community, etc.) to be able to provide safe, effective, and affordable care to the traveler.

Authors contributions: Conceptualization, retrieval of articles for review, critical revision of original draft and approval of final manuscript: Nelson I. Agudelo Higuita, Miranda McGhee, Bryan White, Carlos Franco-Paredes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Nelson Iván Agudelo Higuita, Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, 800 Stanton L. Young Blvd., Suite 7300, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA.

Bryan Pinckney White, Infectious Diseases Clinical Pharmacist, Oklahoma University Medical Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA.

Carlos Franco-Paredes, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA.

Miranda Ann McGhee, Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, 800 Stanton L. Young Blvd., Suite 7300, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Section 2 - Interactions Between Travel Vaccines & Drugs

- Section 2 - Travelers’ Diarrhea

Yellow Fever Vaccine & Malaria Prevention Information, by Country

Cdc yellow book 2024.

Author(s): Mark Gershman, Rhett Stoney (Yellow Fever) Holly Biggs, Kathrine Tan (Malaria)

The following pages present country-specific information on yellow fever (YF) vaccine requirements and recommendations, and malaria transmission information and prevention recommendations. Country-specific maps are included to aid in interpreting the information. The information in this chapter was accurate at the time of publication; however, it is subject to change at any time due to changes in disease transmission or, in the case of YF, changing entry requirements for travelers. Updated information reflecting changes since publication can be found in the online version of this book and on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Travelers’ Health website. Recommendations for prevention of other travel-associated illnesses can also be found on the CDC Travelers’ Health website .

Yellow Fever Vaccine

Entry requirements.

Entry requirements for proof of YF vaccination under the International Health Regulations (IHR) differ from CDC’s YF vaccination recommendations. Under the IHR, countries are permitted to establish YF vaccine entry requirements to prevent the importation and transmission of YF virus within their boundaries. Certain countries require proof of vaccination from travelers arriving from all countries ( Table 5-25 ); some countries require proof of vaccination only for travelers above a certain age coming from countries with risk for YF virus transmission. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines areas with risk for YF virus transmission as countries or areas where YF virus activity has been reported currently or in the past, and where vectors and animal reservoirs exist.

Unless issued a medical waiver by a yellow fever vaccine provider, travelers must comply with entry requirements for proof of vaccination against YF.

WHO publishes a list of YF vaccine country entry requirements and recommendations for international travelers approximately annually. But because entry requirements are subject to change at any time, health care professionals and travelers should refer to the online version of this book and the CDC Travelers’ Health website for any updates before departure.

CDC Recommendations

CDC’s YF vaccine recommendations are guidance intended to protect travelers from acquiring YF virus infections during international travel. These recommendations are based on a classification system for destination-specific risk for YF virus transmission: endemic, transitional, low potential for exposure, and no risk ( Table 2-08 ). CDC recommends YF vaccination for travel to areas classified as having endemic or transitional risk (Maps 5-10 and 5-11 ). Because of changes in YF virus circulation, however, recommendations can change; therefore, before departure, travelers and clinicians should check CDC’s destination pages for up-to-date YF vaccine information.

Duration of Protection

In 2015, the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices published a recommendation that 1 dose of YF vaccine provides long-lasting protection and is adequate for most travelers. The recommendation also identifies specific groups of travelers who should receive additional doses, and others for whom additional doses should be considered (see Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 26, Yellow Fever ). In July 2016, WHO officially amended the IHR to stipulate that a completed International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis is valid for the lifetime of the vaccinee, and YF vaccine booster doses are not necessary. Moreover, countries cannot require proof of revaccination (booster) against YF as a condition of entry, even if the traveler’s last vaccination was >10 years ago.

Ultimately, when deciding whether to vaccinate travelers, clinicians should take into account destination-specific risks for YF virus infection, and individual risk factors (e.g., age, immune status) for serious YF vaccine–associated adverse events, in the context of the entry requirements. See Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 26, Yellow Fever , for a full discussion of YF disease and vaccination guidance.

Table 2-08 Yellow fever (YF) vaccine recommendation categories 1

Malaria prevention.

The following recommendations to protect travelers from malaria were developed using the best available data from multiple sources. Countries are not required to submit malaria surveillance data to CDC. On an ongoing basis, CDC actively solicits data from multiple sources, including WHO (main and regional offices); national malaria control programs; international organizations; CDC overseas offices; US military; academic, research, and aid organizations; and the published scientific literature. The reliability and accuracy of those data are also assessed.

If the information is available, trends in malaria incidence and other data are considered in the context of malaria control activities within a given country or other mitigating factors (e.g., natural disasters, wars, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic) that can affect the ability to control malaria or accurately count and report it. Factors such as the volume of travel to that country and the number of acquired cases reported in the US surveillance system are also examined. In developing its recommendations, CDC considers areas within countries where malaria transmission occurs, substantial occurrences of antimalarial drug resistance, the proportions of species present, and the available malaria prophylaxis options.

Clinicians should use these recommendations in conjunction with an individual risk assessment and consider not only the destination but also the detailed itinerary, including specific cities, types of accommodations, season, and style of travel, as well as special health conditions (e.g., pregnancy). Several medications are available for malaria prophylaxis. When deciding which drug to use, consider the itinerary and length of trip, travelers’ previous adverse reactions to antimalarials, drug allergies, medical history, and drug costs. For a thorough discussion of malaria and guidance for prophylaxis, see Sec. 5, Part 3, Ch. 16, Malaria .

- Arrive within 6 days of leaving an area with risk for YF virus transmission, or

- Have been in such an area in transit (exception: passengers and members of flight crews who, while in transit through an airport in an area with risk for YF virus transmission, remained in the airport during their entire stay and the health officer agrees to such an exemption), or

- Arrive on a ship that started from or touched at any port in an area with risk for YF virus transmission ≤30 days before its arrival in India, unless such a ship has been disinsected in accordance with the procedure recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), or

- Arrive on an aircraft that has been in an area with risk for YF virus transmission and has not been disinsected in accordance with the Indian Aircraft Public Health Rules, 1954, or as recommended by WHO.

- Africa: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo, Uganda

- Americas: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Trinidad & Tobago (Trinidad only), Venezuela

CDC recommendations : Not recommended

- Throughout the country, including the cities of Bombay (Mumbai) and New Delhi (the capital)

- No malaria transmission in areas >2,000 m (≈6,500 ft) elevation in Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, or Sikkim

- Chloroquine

- P. vivax (50%)

- P. falciparum (>40%)

- P. malariae and P. ovale (rare)

- Atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, mefloquine, tafenoquine 3

Other Vaccines to Consider

See Health Information for Travelers to India .

1 Current as of November 2022. This is an update of the 2010 map created by the Informal WHO Working Group on the Geographic Risk of Yellow Fever.

2 Refers to Plasmodium falciparum malaria, unless otherwise noted.

3 Tafenoquine can cause potentially life-threatening hemolysis in people with glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. Rule out G6PD deficiency with a quantitative laboratory test before prescribing tafenoquine to patients.

4 Mosquito avoidance includes applying topical mosquito repellant, sleeping under an insecticide-treated mosquito net, and wearing protective clothing (e.g., long pants and socks, long-sleeve shirt). For additional details on insect bite precautions, see Sec. 4, Ch. 6, Mosquitoes, Ticks & Other Arthropods.

5 Primaquine can cause potentially life-threatening hemolysis in people with G6PD deficiency. Rule out G6PD deficiency with a quantitative laboratory test before prescribing primaquine to patients.

6 P. knowlesi is a malaria species with a simian (macaque) host. Human cases have been reported from most countries in Southwest Asia and are associated with activities in forest or forest-fringe areas. P. knowlesi has no known resistance to antimalarials.

Yellow Fever Maps

2 In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) expanded its YF vaccination recommendations for travelers going to Brazil because of a large YF outbreak in multiple states in that country. Please refer to the CDC Travelers’ Health website for more information and updated recommendations.

3 YF vaccination is generally not recommended for travel to areas where the potential for YF virus exposure is low. Vaccination might be considered, however, for a small subset of travelers going to these areas who are at increased risk for exposure to YF virus due to prolonged travel, heavy exposure to mosquitoes, or inability to avoid mosquito bites. Factors to consider when deciding whether to vaccinate a traveler include destination-specific and travel-associated risks for YF virus infection; individual, underlying risk factors for having a serious YF vaccine–associated adverse event; and destination entry requirements.

The following authors contributed to the previous version of this chapter: Mark D. Gershman, Emily S. Jentes, Rhett J. Stoney (Yellow Fever) Kathrine R. Tan, Paul M. Arguin (Malaria)

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Malaria risk map for India based on climate, ecology and geographical modelling

Affiliation.

- 1 ICMR - National Institute of Malaria Research, New Delhi. [email protected].

- PMID: 31724378

- DOI: 10.4081/gh.2019.767

Mapping the malaria risk at various geographical levels is often undertaken considering climate suitability, infection rate and/or malaria vector distribution, while the ecological factors related to topography and vegetation cover are generally neglected. The present study abides a holistic approach to risk mapping by including topographic, climatic and vegetation components into the framework of malaria risk modelling. This work attempts to delineate the areas of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria transmission risk in India using seven geo-ecological indicators: temperature, relative humidity, rainfall, forest cover, soil, slope, altitude and the normalized difference vegetation index using multi-criteria decision analysis based on geographical information system (GIS). The weight of the risk indicators was assigned by an analytical hierarchical process with the climate suitability (temperature and humidity) data generated using fuzzy logic. Model validation was done through both primary and secondary datasets. The spatio-ecological model was based on GIS to classify the country into five zones characterized by various levels of malaria transmission risk (very high; high; moderate; low; and very low. The study found that about 13% of the country is under very high malaria risk, which includes the malaria- endemic districts of the states of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Tripura, Assam, Meghalaya and Manipur. The study also showed that the transmission risk suitability for P. vivax is higher than that for P. falciparum in the Himalayan region. The field study corroborates the identified malaria risk zones and highlights that the low to moderate risk zones are outbreak-prone. It is expected that this information will help the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme in India to undertake improved surveillance and conduct target based interventions.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Anopheles / growth & development

- Geographic Information Systems

- Geographic Mapping*

- India / epidemiology

- Malaria / epidemiology*

- Malaria, Falciparum / epidemiology*

- Malaria, Vivax / epidemiology*

- Mosquito Vectors / growth & development

- Risk Assessment

- Risk Factors

- Soil / chemistry

- India Tourism

- India Hotels

- India Bed and Breakfast

- India Vacation Rentals

- Flights to India

- India Restaurants

- Things to Do in India

- India Travel Forum

- India Photos

- All India Hotels

- India Hotel Deals

- Last Minute Hotels in India

- Things to Do

- Restaurants

- Vacation Rentals

- Travel Stories

- Rental Cars

- Add a Place

- Travel Forum

- Travelers' Choice

- Help Center

Malaria pills needed for travel to these destinations? - India Forum

- Asia

- India

Malaria pills needed for travel to these destinations?

- United States Forums

- Europe Forums

- Canada Forums

- Asia Forums

- Central America Forums

- Africa Forums

- Caribbean Forums

- Mexico Forums

- South Pacific Forums

- South America Forums

- Middle East Forums

- Honeymoons and Romance

- Business Travel

- Train Travel

- Traveling With Disabilities

- Tripadvisor Support

- Solo Travel

- Bargain Travel

- Timeshares / Vacation Rentals

- Asia forums

- India forum

We will be going to New Delhi , Jaipur , Agra , Khajuraho, Bandhavgarh, and back to New Delhi on a 10 day escorted tour.

Your thoughts on the need for the Malaria pills? Thank you!

It is better to carry.

Hi Mustseeitall.

For those destinations you've mentioned, no you wouldn't need malaria tabets. You can check the Fit to Travel website to be sure, but I think Bandhavgarh was the only 'slightly' suspect regon.

Check this map out - http://www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/destinations/asia-(east)/india/india-malaria-map.aspx

Thank you for all of your great replies!!

Better safe than sorry.

This topic has been closed to new posts due to inactivity.

- Safaris when staying at Aman I Khas 6:29 am

- Badrinath in late April/early May 2024 6:14 am

- Train ticket to shridi 5:58 am

- Visit to ARUNACHAL in MAY 1st week 5:53 am

- Stays in jibhi 5:37 am

- Looking for tour operator for 3N including Lachung 5:07 am

- North east itinerary 4:26 am

- Drive fromK bagdogra airport to gangtok 4:26 am

- Sikkim itinerary for 5 to 6D in june? 4:23 am

- Hotels Near Christ University Central Campus 4:10 am

- Which GSM operator do you recommend for Golden Triangle? 4:06 am

- Delhi-Taj Mahah daytour in June 3:55 am

- Taxi availability 3:54 am

- Accomodation for four 3:25 am

- Makemytrip.com 277 replies

- Weather beginning of January? 7 replies

- A perfect location for honeymoon in February 9 replies

- masoori(e) hill station 6 replies

- train from mumbai to kerala 12 replies

- Best places for honeymoon in June 7 replies

- Thomas cook india - europe tour review 97 replies

- Best Tour Operator for Europe - Thomas Cook/SOTC/Cox/Others 4 replies

- Easy Tours of India 12 replies

- New Years Eve Parties 2013 India (City) 19 replies

India Hotels and Places to Stay

- How to apply for e-Visa: 30 days, one year and five years

- How to apply for Regular Tourist visa (up to 12 months) (or from 1 to 5 years)

- How to transfer on an Indian airport between two flights, esp. with 2 tickets

- Trip Report for North Eastern States

- Post Your Just Back Reports / Trip Reports

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Learn more

Information on how to stay safe and healthy abroad. About us.

- Destinations

- United Republic of Tanzania

- Asia (Central)

- Asia (East)

- Australasia & Pacific

- Central America

- Europe & Russia

- Middle East

- North America

- South America & Antarctica

United Republic of Tanzania Malaria Map

Malaria Information and Prophylaxis, by Country [L]

The information presented in this table is consistent 1 with the information in the CDC Health Information for International Travel (the “Yellow Book”).

1. Factors that affect local malaria transmission patterns can change rapidly and from year to year, such as local weather conditions, mosquito vector density, and prevalence of infection. Information in these tables is updated regularly. 2. Refers to P. falciparum malaria unless otherwise noted. 3. Estimates of malaria species are based on best available data from multiple sources. Where proportions are not available, the primary species and less common species are identified. 4. Several medications are available for chemoprophylaxis . When deciding which drug to use, consider specific itinerary, length of trip, cost of drug, previous adverse reactions to antimalarials, drug allergies, and current medical history. All travelers should seek medical attention in the event of fever during or after return from travel to areas with malaria. 5. Primaquine and tafenoquine can cause hemolytic anemia in persons with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. Before prescribing primaquine or tafenoquine, patients must be screened for G6PD deficiency using a quantitative test. 6. Mosquito avoidance includes applying topical mosquito repellant, sleeping under an insecticide treated bed net, and wearing protective clothing (e.g., long pants and socks, long sleeve shirt). For additional details on mosquito avoidance, see: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/index.html 7. P. knowlesi is a malaria species with a simian host (macaque). Human cases have been reported from most countries in Southeast Asia and are associated with activities in forest or forest-fringe areas. This species of malaria has no known resistance to antimalarials.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Learn more

Information on how to stay safe and healthy abroad. About us.

- Destinations

- Central America

- Asia (Central)

- Asia (East)

- Australasia & Pacific

- Europe & Russia

- Middle East

- North America

- South America & Antarctica

Guatemala Malaria Map

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Map showing extent of malaria risk in India.

India Malaria Map

Advice for All Destinations COVID-19. Read the information on the COVID-19: Health Considerations for Travel page for advice on travelling during the COVID-19 pandemic.. Vaccinations and malaria risk. Review both the Vaccination and Malaria sections on this page to find out if you may need vaccines and/or a malaria risk assessment before you travel to this country.

Malaria is a risk in India. Fill your malaria prescription before you leave and take enough with you for the entire length of your trip. ... For information traffic safety and road conditions in India, see Travel and Transportation on US Department of State ... Map Disclaimer - The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on maps do ...

All areas throughout country, including cities of Bombay (Mumbai) and New Delhi, except none in areas > 2,000 m (6,562 ft) in Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Sikkim. Chloroquine. P. vivax 50%, P. falciparum >40%, P. malariae and P. ovale rare. Atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, mefloquine, or tafenoquine 5.

I've researched many sites. US CDC tends to take a more conservative approach and implies anti-malarial are recommended for the entire country other than high altitude locations. Fit for Travel (not sure if this is UK government or private) includes a map of India and shows all of my planned locations as being "low to no risk".

Malaria is a serious parasite infection that is transmitted by the bite of female mosquitoes. The parasites are microscopic and found in the blood of infected people. There are different types of malaria parasite and although the infection they cause is similar. 'Falciparum' malaria is the one that causes the most severe infection.

Reprint of malaria map from Health Information for International Travel 1974 (CDC 1974) View Larger Figure. For many years, CDC Yellow Book included World Health Organization global malaria maps, which generally followed the above design style. Small size and lack of labels made these maps difficult to interpret for specific travel itineraries.

Malaria Threats Map Explore data about the major biological threats to malaria control and elimination. Maps. Explore individual studies and site-level data for all the threats. Enter Map. Dashboards. View summaries of the threats at different geographical levels. View Dashboards. Data download.

Malaria Maps. The maps included are to be used to accompany the GDRI when assessing the malaria risk for a donor. They have been sourced from the Fit for travel website. ... The advice below each map relates to the Fit for travel website. Decisions regarding malaria guidance should be made using the template below. The colours used in the maps ...

Introduction. Malaria is a parasitic disease caused by protozoa belonging to the genus Plasmodium.There are four species that exclusively affect humans: Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale, and Plasmodium malariae.Plasmodium species that commonly infect non-human primates can also be responsible for a high proportion of human cases in certain parts of the world as is the ...

Information about how to order the U.S. government publication about traveling titled "Health Information for International Travel" (also called the "Yellow Book"). Provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Malaria Information and Prophylaxis, by Country [U] The information presented in this table is consistent 1 with the information in the CDC Health Information for International Travel (the "Yellow Book"). Primarily P. falciparum. Less commonly, P. malariae, P. ovale, or P. vivax. 1.

This is an update of the 2010 map created by the Informal WHO Working Group on the Geographic Risk of Yellow Fever. Malaria Prevention. 2 Refers to Plasmodium falciparum malaria, unless otherwise noted. 3 Tafenoquine can cause potentially life-threatening hemolysis in people with glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. Rule out ...

The spatio-ecological model was based on GIS to classify the country into five zones characterized by various levels of malaria transmission risk (very high; high; moderate; low; and very low. The study found that about 13% of the country is under very high malaria risk, which includes the malaria- endemic districts of the states of ...

Answer 1 of 6: My travel advice nurse says I should take Malaria pills for my trip to India later this month. We will be going to New Delhi, Jaipur, Agra, Khajuraho, Bandhavgarh, and back to New Delhi on a 10 day escorted tour. Your thoughts on the need...

1) City(ies) of travel 2) District of travel 3) Altitude of city(ies) of travel Altitude information and to determine if a city is within a certain district external icon General map of Bhutan external icon: Bolivia: All areas below 2,500 m (8,202 ft). None in the city of La Paz: Chloroquine: P. vivax 99%, P. falciparum 1%

Guyana. Paraguay. Peru. Suriname. Uruguay. Venezuela Margarita Island. back to top. List of country information found in fitfortravel, information is split by continent and there is a text search to help you locate the country information.

Map showing extent of malaria risk in Rwanda.

Map showing extent of malaria risk in Mexico.

Map showing extent of malaria risk in United Republic of Tanzania.

Malaria Information and Prophylaxis, by Country [L] The information presented in this table is consistent 1 with the information in the CDC Health Information for International Travel (the "Yellow Book"). All, except none in the city of Vientiane. Along the Laos-Burma (Myanmar) border in the provinces of Bokeo and Louang Namtha and along ...

Map showing extent of malaria risk in Guatemala.