Gypsy and Traveler Culture in America

Gypsy and Traveler Culture, History and Genealogy in America

Are you a Gypsy, Traveler or Roader, or have some ancestry in any one of such groups? This site is dedicated to you; to help you become more aware of your own rich heritage, to help preserve your traditions, language and knowledge of where you came from and who you are.

The identities of Traveling People are everywhere threatened by the flood of misinformation that is being disseminated on the web and through the popular media. This site pledges to correct such misinformation and to present an accurate and unbiased view of traveling life as it has unfolded since the your ancestors first set foot in the New World.

Preservation of your ethnic heritage and pride in your own ethnic identity are some of the most valuable assets that any parents can leave to their children and grandchildren. To be of Gypsy or Traveler background is something special, something to be treasured along with the language, customs, and cultural values embodied in a unique way of life.

If you want to learn more about your family and your ethnic group, whether you be of Cale, Hungarian-Slovak, Ludar, Rom, Romnichel or Sinti Gypsy or American (Roader), English, German, Irish or Scotch Traveler background we will provide you with an interactive forum for asking questions, finding lost relatives, guidance to accurate sources, exchanging information as well as just keeping in touch with your own kind.

To get started just send a note to ASK MATT specifying what kind of Gypsy you are and in which family background you are interested.

The foundation on which this site is built is a rich storehouse of data of every imaginable kind: documentary sources, oral histories and observations of traveling life collected in over 35 years of unpaid research by Matt and Sheila Salo. The Salos have dedicated their lives to providing a true history of traveling life in America and to dispelling the myths that are currently being spread on the web and other media.

This endeavor is based on the premise that every kind of Gypsy and Traveler has a right to his or her own identity, whatever it might be. Each of you has a unique heritage that your ancestors nurtured over centuries of hardship and persecution. Now those rich and unique identities are in danger of being lost as more and more people lose the sense of who they are; customs, language and traditional life patterns are not being passed on; some people are even becoming ashamed of their Gypsy or Traveler identities.

Again, email any specific inquiries into American Gypsy or Traveler history, culture and genealogy to Matt T. Salo at ASK MATT .

Forthcoming: This history and culture page under preparation will be divided into subject areas that you can access separately depending on your interests. If you seek information sources, have specific questions, or want to broaden your horizons by learning about other groups, we will provide the best, most accurate information available. You will not be fed speculations about Melungeons, hordes of Gypsies in Colonial America, or Gypsies and Travelers as hapless victims or criminal castes - instead all our information will be based on actual verified data that truly represents the experience of your people in America since your ancestors first arrived here.

Culture and language are not easily lost and, unless you are among those few unfortunate individuals whose parents or grandparents misguidedly tried to separate themselves and their families from their roots, you should easily be able to pick up traits of language and culture that indicate your origins. We will begin with a brief overview of the different groups to orient those among you who are not quite sure of where they belong. More detailed descriptions will follow.

Gypsy and Traveler Groups in the United States

Cale: Spanish Gypsies, or Gitanos, are found primarily in the metropolitan centers of the East and West coasts. A small community of only a few families.

English Travelers: Fairly amorphous group, possibly formed along same lines as Roaders (see below), but taking shape already in England before their emigration to the US starting in early 1880s. Associate mainly with Romnichels. Boundaries and numbers uncertain.

Hungarian-Slovak: Mainly sedentary Gypsies found primarily in the industrial cities of northern U.S. Number in few thousands. Noted for playing "Gypsy music" in cafes, night clubs and restaurants.

Irish Travelers: Peripatetic group that is ethnically Irish and does not identify itself as "Gypsy," although sometimes called "Irish Gypsies." Widely scattered, but somewhat concentrated in the southern states. Estimates vary but about 10,000 should be close to the actual numbers.

Ludar: Gypsies from the Banat area, also called Rumanian Gypsies. Arrived after 1880. Have about the same number of families as the Rom, but actual numbers are unknown.

Roaders or Roadies: Native born Americans who have led a traveling life similar to that of the Gypsies and Travelers, but who were not originally descended from those groups. Numbers unknown as not all families studied.

Rom: Gypsies of East European origin who arrived after 1880. Mostly urban, they are scattered across the entire country. One of the larger groups in the US, possibly in the 55-60,000 range.

Romnichels: English Gypsies who arrived beginning in 1850. Scattered across the entire country, but tend to be somewhat more rural than the other Gypsy groups. Many families are now on their way to being assimilated, hence estimation of numbers depends on criteria used.

Scottish Travelers: Ethnically Scottish, but separated for centuries from mainstream society in Scotland where they were known as Tinkers. Some came to Canada after 1850 and to the United States in appreciable numbers after 1880. Over 100 distinct clans have been identified but total numbers not known.

Sinti: Little studied early group of German Gypsies in the United States consisting of few families heavily assimilated with both non-Gypsy and Romnichel populations. No figures are available.

Yenisch: Mostly assimilated group of ethnic Germans, misidentified as Gypsies, who formed an occupational caste of basket makers and founded an entire community in Pennsylvania after their immigration starting 1840. Because of assimilation current numbers are impossible to determine.

This inventory leaves out several Gypsy groups that have immigrated since 1970 due to the unrest and renewed persecution in Eastern Europe after the collapse of Communism. They have come from Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, the former Yugoslavian area, and possibly other countries. They number in few thousands by now, but their numbers are likely to increase.

Copyright @ 2002 Matt T. Salo

Subscription Offers

Give a Gift

Britain's Gypsy Travellers: A People on the Outside

Despite the popularity of shows like My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding , Britain’s Gypsy Travellers still face longstanding prejudice, warns Becky Taylor.

Two months later and Channel 4’s My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding is generating waves on television. While sympathetic and giving a voice to Gypsy Travellers, it nevertheless presents an exoticised image of their lives: the horse-drawn wagons, extravagant dresses and flamboyant wedding arrangements seem to encapsulate how they remain the ‘other’ of British society. As the opening voiceover put it: ‘For hundreds of years the Gypsy way of life was one of ancient traditions and simple tastes. Then their world collided with the 21st century. With unprecedented access to the UK’s most secretive community … this series will take you to the very heart of Gypsy life.’ If contemporary images of Gypsy Travellers seem to be polarised between vilification and the exotic, can the same be said for historical depictions of one of Britain’s oldest minority groups?

While the details remain contested, it is now broadly agreed that Europe’s Roma and Gypsy populations can trace their origins back to an Indian diaspora in the tenth century, with ‘Egyptians’ arriving in Britain by the early 16th century. Despite persecution, Gypsies established themselves, finding niches in both town and countryside, sometimes being protected by landowners who found them useful as a supply of casual labour, for entertainment and sometimes simply by the inconsistent application of the law. Their treatment reflected majority society’s deep ambivalence about the presence of Gypsies and a nomadic way of life. On the one hand it symbolised freedom from the responsibilities and duties associated with settled lifestyles – typified in folk songs such as ‘The Raggle-taggle Gypsy’; on the other it provoked an almost visceral hatred, a suspicion that Gypsies could evade the law and the codes of behaviour that bound settled society to a place and a parish.

Rather than being polar opposites, however, we might understand these stereotypes as two sides of a coin – as the product of a tendency to view Gypsy lives through the lens of the preoccupations and assumptions of mainstream society – rather than being grounded in reality. Whether articulated positively or negatively these stereotypes stem from the assumption that Gypsies were irredeemably separate from the rest of the population.

Yet, contrary to these stereotypes, Gypsies and Travellers traded with, worked and lived alongside the rest of the population: an analysis of the traditional songs sung by Gypsies and Travellers, for example, shows significant overlap with those current in wider society, suggesting a high degree of interaction between the communities, particularly in casual agricultural and seasonal labour. Arthur Harding’s classic account of the East End underworld at the beginning of the 20th century, compiled by the historian Raphael Samuel, revealed in passing how Gypsy Travellers were part of the everyday fabric of poor urban life. David Mayall’s work on the 19th century, my own on the 20th and that of the Dutch scholars Lucassen, Willems and Cottars for the European context all confirm the ways in which the lives of Gypsy Travellers and settled populations were intimately interconnected and often how the lines between them were in fact blurred. Gypsies lived in peri-urban encampments or even cheap lodging in cities over winter alongside working-class populations, making and selling goods, moving in regular circuits across the countryside in the spring and summer, picking up seasonal work, hawking and attending fairs. Far from being ‘a separate people’, their economic survival in fact depended on close engagement with the wider population.

The stereotypes became increasingly entrenched over the course of the 19th century as Britain’s population became increasingly urbanised and the countryside became the repository for the working out of anxieties related to the rapidly changing social and physical landscape. Alongside phenomena like the folk song revival, the cult of the ‘outdoors’ and the early caravanning movements there emerged a movement of amateur ‘gentlemen scholars’, self-styled ‘gypsiologists’, who developed an interest in recording the origins, language and customs of Britain’s Gypsy Travellers. Focused around the activities of the Gypsy Lore Society (GLS), established in 1889, they became preoccupied with the foreign ancestry of British Gypsies and with developing theories about their ‘pure bred’ nature, which often tied blood lines to Romany language use and ‘proper’ nomadic living. The Gypsy caravan, which had only made its appearance in the 1830s as a result of the improving road system, became central to settled society’s image of ‘the Gypsy’, in part through paintings, such as those of the prominent GLS member Augustus John. Fed by an outpouring of writings on the subject from the 1880s, popular imagination saw Gypsies as a people who turned up out of the blue, camped on commons or byways in their bow-topped caravan, grazed horses, sold pegs, perhaps ‘tinkering’, ‘here today and gone tomorrow’. Just as the producers of My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding promised ‘unprecedented access’, so too did numerous gypsiologists spend a summer living with a group of Gypsy Travellers gaining an insight into ‘the secret people’ before writing a book about their experiences. Crucially, such Gypsies were always portrayed as ‘pure blooded’ or ‘true’ Romanies, largely untouched by modern, industrialised Britain. As one gypsiologist, Arthur Symons, wrote in the early 20th century:

Why ... are we setting ourselves the impossible task of spoiling the Gypsies? ... they stand for the will of freedom, for friendship with nature, for the open air, for change and the sight of many lands; for all of us that are in protest against progress ... The Gypsies represent nature before civilisation ... the last romance left in the world.

Crucially, for these stereotypes to find resonance in modern Britain, gypsiologists constructed a theory around the decline in the racial purity of Gypsies as they increasingly mixed and married with ‘degenerate’ members of the settled population. They developed a racial hierarchy which placed ‘pure-blooded’ Gypsies, who were believed to speak the best Romany, at the top; followed by ‘didikais’, half-breeds, or ‘pikies’ – groups with varying proportions of Gypsy blood depending on which source one reads; and ‘mumpers’, who were vagrants with no Romany ancestry, at the bottom. As David Mayall observed:

To confuse the ‘true’ Gypsy with those of diluted blood was presented as a grave error that led to much injustice being directed towards the clean-living Romany. The latter, declining in numbers as the century progressed, were superior in manners, morals and occupations to their degenerate and impoverished ‘mumply-brothers’. These half-breeds were said to have inherited all the vices of the Romany and the Gaujo [non-Gypsy] but none of their virtues.

For gypsiologists anxious to discover a Golden Age and a pure Gypsy culture this outlook allowed them to pursue their pet theories, with any contradictory findings dismissed as the result of cultural pollution and miscegenation. This enabled gypsiologists to distance themselves from the squalid, urban Traveller encampments that existed around all Britain’s major cities and any other elements that impinged on romantic notions of a rural Gypsy idyll.

Just as the impetus to romanticise Gypsies gained ground in the later 19th century, so too did negative stereotypes, as a growing body of opinion saw Travellers as being out of step with modern society. Along with longstanding beliefs about the lazy and lawless nature of Gypsies came newer concerns about their unsanitary habits, which were seen as anachronistic in a nation that increasingly set store by its housing and sanitary legislation. Added to this were commonly expressed sentiments that they were escaping from paying taxes and consequently evaded the responsibilities that came with modern living. Such views gained ground particularly in times of social difficulty. During the Second World War Gypsies were a common scapegoat for the press, which depicted them as shirkers and deserters, able to escape conscription through their nomadism and evading rationing through poaching and foraging. As the South Wales Evening Post put it: ‘Many people wonder how Gypsies get off with food rationing. It is understood, however, that hedgehogs are not rationed.’

Lacking a political voice or a representative body Gypsy Travellers responded to this entrenchment of stereotypes not by challenging them but by working within their parameters. Thomas Acton first pointed to the practice of claiming to have ‘pure Gypsy blood’ as a means of asserting an individual’s right to travel, while scapegoating other travelling communities: ‘I’m a real Gypsy/Traveller/Romani, and we don’t do that, only the (ethnic category name with pejorative overtones)’. He observed that the effect of this ‘transference of blame’ was to divert the hostility of the accuser away from that particular individual to an absent outsider group which both parties could agree was fundamentally incapable of maintaining a nomadic lifestyle. While in the short run this was ‘an attractive strategy for the individual Traveller’, it was not without its shortcomings, as it served to confirm racialised definitions of

Travellers, equating a right to travel with spurious definitions of blood purity. It was not until the 1960s and the formation of the Gypsy Council that Gypsy Travellers as a community found a collective voice, one which tried to assert that all had a right to travel and that nomadism did have a place in modern Britain. While it scored some early successes, notably in the 1968 Caravan Sites Act, its influence both within and outside the travelling community has declined over recent years and has failed to dislodge the enduring stereotypes surrounding Gypsies.

Travellers have modernised alongside the rest of society and are not a ‘secret people’ living in the manner of their great grandparents. Crucially this change in their lifestyle has removed what settled society understands as the markers of ‘true’ Gypsies: bow-topped caravans, horses and so on. These images of Gypsies have become the rod with which their back is consistently beaten: failing to conform to romantic expectations, the stereotypes most often deployed in the popular press and by politicians are the negative ones relating to anti-social behaviour and an inability to adapt to the standards of ‘normal’ society.

This leads us back to the people of Dale Farm and the stars of My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding . We may wonder at the dresses and tut over wedding venues cancelling bookings when they find they are to host a Traveller wedding, but this translates into neither an understanding of the place of Gypsy Travellers in British society nor positive political action. Living in an ex-scrapyard by the side of a busy dual carriageway, the Dale Farm homes are immaculate trailers from which furniture-selling businesses are run. Vulnerable through their lack of romantic visual appeal and unable to attract political representation, Travellers are facing the active prejudice not just of Basildon Council but of councils across the country, which decide not only that Travellers may not stay on their own land, but are also determined that there is no place for a Traveller community within its district. It is surely time for us to move beyond the stereotypes which have served Gypsy Travellers, settled society and historical analysis so ill for centuries and instead have the strength to embrace the diversity and richness represented by Britain’s nomadic communities. Seeing 80 families being put onto the highway will be Britain’s shame as much as Sarkozy’s expulsion of Roma from France.

Becky Taylor is author of A Minority and the State: Travellers in Britain in the 20th Century (Manchester University Press, 2008).

Popular articles

Why Were the Jews Persecuted?

Was Portugal’s Carnation Revolution Inevitable?

This is Home: An Irish Traveller in Hackney Wick

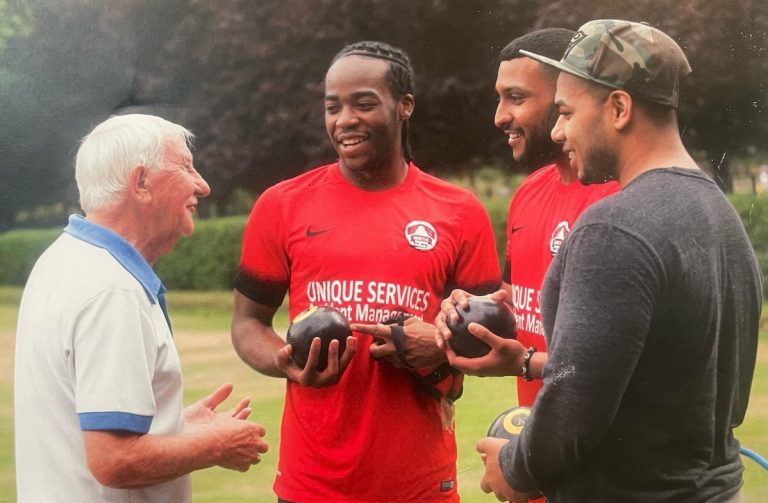

Irish Traveller and a proper East Ender, Danny Mongan is bridging cultural divides and challenging perceptions of Travellers’ rootlessness.

When Danny Mongan, 32, opens his mouth to speak, you’d never guess he was born in Homerton Hospital and has spent his whole life in the East End.

The son of Irish Travellers who arrived in East London in the 80s, a soft Irish accent has stayed with Mongan who was brought up in a large Traveller site in Hackney Wick.

In 2010, the site was demolished to make way for the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, and the inhabitants of more than 20 plots were split between three new sites in Hackney, where his family still lives today.

Mongan pulls up to our interview in Hackney Wick in a convertible BMW that I’m all too aware he has left unlocked and on a yellow line. But his easy-going confidence tells me that he didn’t do it mistakenly.

Sitting outside HWK Cafe, our interview is interrupted by someone asking Mongan to move his car so a delivery van can get through. ‘He didn’t ask anyone else if it was their car!’ laughs Mongan: ‘How did he immediately know it was mine?!’ he asks, feigning surprise and gesturing to his tattoos and gold chain.

Though he is proud of his Irish Traveller identity, Mongan chats candidly about parts of his culture that he disagrees with. Describing himself as a ‘black sheep’, he divides his life between his ‘inside’ Irish family and his ‘outside family’, referring to his non-Traveller friends. Optimistic and instantly personable, it takes a character like Mongan to slip in and out of these disparate worlds.

Working for the Gypsy Traveller Leauge (GTL), he aims to break down cultural barriers and challenge the perception of Travellers. Mongan is something of a chameleon and can often be found with his non-Traveller friends partying in Hackney Wick. But he frequently witnesses the discrimination faced by the Irish Traveller community in East London pubs and other venues, which he is determined to change.

What was your schooling like?

‘I went to Kingsmead Primary School in Hackney but I didn’t go to secondary school. I always had a different mindset from my siblings and my cousins, I was really inquisitive and I always wish I’d gone to secondary school. I think that’s one of the worst things about the Gipsy community. There’s so much hidden talent but they steal education away from our young people by taking them out of school. I did some typical Gypsy jobs like tarmacking and tree-topping but I never felt like they were for me.’

What does family mean to you?

‘Family means honour, good values, and good morals. It does mean a lot. But I dip in and out of the family bubble and through the years I’ve also found my outside family. Sometimes I don’t really believe that whole moto, ‘blood is thicker than water’ because there are a lot of cousins that I ‘uncousined’ if that makes sense when I saw how quick they were to turn their back on me when I went through my dark days, and my outside family, they’ve done everything in the world for me, so family in those two senses can mean the very opposite.

How many siblings do you have?

‘Six or seven, I think.’

A lot of Travellers keep their identity a secret but I will never deny who I am. Danny Mongan

Do you have the same cultural values as your family?

‘I respect some of my family’s values but I’ve always been a bit of a black sheep. I’ve mixed with my friends’ families who aren’t Travellers and I used to crave that relationship with my parents; being able to have open conversations about sex and drugs and things like that, but I didn’t talk about that with my parents and even though I know they love me, they never said it to me.

‘I’ve always been a bit smarter than my family and I don’t know why because I had the exact same upbringing as them but I’ve always thought like an outsider. It’s kind of a gift but I really craved your lifestyle.

‘I got married when I was 18 years old and it’s not like I was forced, I did love the girl, but we were divorced by the time I was 23. In the community, it was as if I had murdered someone or had committed some terrible crime. Some people were really ashamed and news travels really quickly in such a tight-knit community. Even people that I wasn’t friends with suddenly made it their business to know. So I thought I had to just get out, so I bought a flat in Homerton and that’s when I met people outside the community and made friends through festivals and my love of house music.’

What meal makes you feel especially at home?

‘Our dinner. I don’t know if you have a name for it but we just call it ‘our dinner’. It’s a traditional Gypsy Traveller dish with spuds, turnips, cabbage and other vegetables all cooked together in this broth. Sometimes you add mince or stewed chicken.’

What’s the best way to bridge cultural divides between people?

‘To mix. I respect a lot of Travellers’ ways but I don’t respect all of their ways. They have very good morals and values but I don’t respect leaving school at 13 and getting married by 17, that’s something that I think has to change. But to break that cultural divide and to get everyone to understand each other, I do feel like the Travellers need to mix more.

‘I think lots of Travellers are hypocritical because they will only mix with the outside world when they need something, like council support or they need to book a venue or something like that, but I love learning about people’s lives and people’s families. It’s give and take, you have to put yourself out there to be accepted. They don’t have to be best friends with everyone from the outside community, but I think too many Travellers hide away and are really closed, which is probably because they’ve been unfairly treated in the past, but then it just gets worse when people don’t know you.’

What does the East End mean to you?

‘The East End means home, so even though my heritage is Irish, I was born here and I grew up here. I used to hang around Hackney Wick when it was just warehouses and squatters and there was a lot of crime. People will see one burglary around here and think they know what it was like but really they don’t have a clue! It’s changed so much.

‘What I love about the area is that it’s so diverse. There are some cities that you go to and no matter how big the city is, the whole city feels the same. London is so diverse and so multicultural, you know when you’re in East London, West London, North London and South London, they’re so different. East London is by far my favourite, it’s so quirky and different and it means home to me.’

What would you say to those who make the Irish Traveller community feel unwelcome in East London?

‘Some of them might be uneducated, and some of them might know exactly what they’re doing. I’ve met all walks of people in life because I bounce in and out of the bubble, whereas my cousins don’t leave the bubble, and people from outside the bubble have never been inside the bubble, so a lot of people are uneducated and they’re the ones causing these barriers.

‘I think people outside the Traveller community should try to get to know us as well, educate themselves and not believe everything they see in the media, so don’t just jump to conclusions.

‘When people see a big group of Travellers coming into a pub they think this might happen or that might happen. They’ll say: ‘Your cousin was in here last weekend and started a fight.’ But if any marginalised group of people got into a fight at the pub, you’d just kick them out, you wouldn’t bar the whole community from ever going back there.

‘Imagine if you were going to pubs and you were being treated like a dog, being left outside and made to feel like utter shit. You’d want a voice, you’d want to be heard, you’d want respect and to be treated like a human being.’

I think people outside the Traveller community should try to get to know us as well, educate themselves and not believe everything they see in the media. Danny MOngan

What’s the most common misconception about Irish Travellers?

‘That we’re fighters. It doesn’t help that lots of Travellers get into MMA fighting so couple seeing that on the TV with some Irish traveller getting drunk in a pub and fighting and then all of a sudden people think we’re all like that.

‘I’m a really friendly guy and I’m inquisitive about other people so I always chat to people on nights out and I never hide that I’m a Traveller. Then at the end of the night, I often get people saying how surprised they are by me but I can’t change perceptions all on my own! A lot of Travellers keep their identity a secret but I will never deny who I am.’

What is Hackney Wick’s best-kept secret?

‘I sometimes go to HWK Bar, Lord Napier Star and Queen’s Yard. But the best places are those crazy little boat parties you stumble across on the canal. You think it’s just old people living in there and then you look in and this tiny thin boat turns into a mansion inside.’

What is your message to the next generation?

‘My son is nine years old and I want him to do everything that was stolen from me. I want him to go to school and get a good job and know that he can. So many Travellers are just brought up like robots. Travellers need to know that they can be footballers and astronauts and whatever but those opportunities are stolen from them when they get taken out of school and get married at 18.

‘So if my son decides he wants to do that I guess I’ll have to be okay with that, but I hope he doesn’t. I want him to be able to talk to me about anything in a way that I couldn’t with my parents.’

If you enjoyed reading this article, find the previous piece in our This is Home series about memories of Clare House in Bow.

Our members

The Play Is Not The Thing

Victoria Park Bowls Club

The Common Room

Save Our Safer Streets Bethnal Green

The Illusion of Depth at Victoria Baptist Church, Bow

Please support local journalism.

As a not-for-profit media organisation using constructive journalism to strengthen communities, we have not put our digital content behind a paywall or subscription fee as we think the benefits of an independent, local publication should be available to everyone living in our area.

We are powered by members. Hundreds of members have already joined. Become a member to donate as little as £3 per month to support constructive journalism and the local community.

- Liverpool Street Station named ‘at risk’ by Victorian Society Endangered Buildings list

- Mishti Doi recipe: Treat the family on Eid Al-Adha

One thought on “ This is Home: An Irish Traveller in Hackney Wick ”

Great article – really enjoyed reading that

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Sign me up for the newsletter!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe to our FREE weekly newsletter.

Be the first to hear about the latest news, culture and things to do in and around Roman Road .

Change Location

Find awesome listings near you.

Gypsy Roma and Traveller History and Culture

Gypsy Roma and Traveller people belong to minority ethnic groups that have contributed to British society for centuries. Their distinctive way of life and traditions manifest themselves in nomadism, the centrality of their extended family, unique languages and entrepreneurial economy. It is reported that there are around 300,000 Travellers in the UK and they are one of the most disadvantaged groups. The real population may be different as some members of these communities do not participate in the census .

The Traveller Movement works predominantly with ethnic Gypsy, Roma, and Irish Traveller Communities.

Irish Travellers and Romany Gypsies

Irish Travellers

Traditionally, Irish Travellers are a nomadic group of people from Ireland but have a separate identity, heritage and culture to the community in general. An Irish Traveller presence can be traced back to 12th century Ireland, with migrations to Great Britain in the early 19th century. The Irish Traveller community is categorised as an ethnic minority group under the Race Relations Act, 1976 (amended 2000); the Human Rights Act 1998; and the Equality Act 2010. Some Travellers of Irish heritage identify as Pavee or Minceir, which are words from the Irish Traveller language, Shelta.

Romany Gypsies

Romany Gypsies have been in Britain since at least 1515 after migrating from continental Europe during the Roma migration from India. The term Gypsy comes from “Egyptian” which is what the settled population perceived them to be because of their dark complexion. In reality, linguistic analysis of the Romani language proves that Romany Gypsies, like the European Roma, originally came from Northern India, probably around the 12th century. French Manush Gypsies have a similar origin and culture to Romany Gypsies.

There are other groups of Travellers who may travel through Britain, such as Scottish Travellers, Welsh Travellers and English Travellers, many of whom can trace a nomadic heritage back for many generations and who may have married into or outside of more traditional Irish Traveller and Romany Gypsy families. There were already indigenous nomadic people in Britain when the Romany Gypsies first arrived hundreds of years ago and the different cultures/ethnicities have to some extent merged.

Number of Gypsies and Travellers in Britain

This year, the 2021 Census included a “Roma” category for the first time, following in the footsteps of the 2011 Census which included a “Gypsy and Irish Traveller” category. The 2021 Census statistics have not yet been released but the 2011 Census put the combined Gypsy and Irish Traveller population in England and Wales as 57,680. This was recognised by many as an underestimate for various reasons. For instance, it varies greatly with data collected locally such as from the Gypsy Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessments, which total the Traveller population at just over 120,000, according to our research.

Other academic estimates of the combined Gypsy, Irish Traveller and other Traveller population range from 120,000 to 300,000. Ethnic monitoring data of the Gypsy Traveller population is rarely collected by key service providers in health, employment, planning and criminal justice.

Where Gypsies and Travellers Live

Although most Gypsies and Travellers see travelling as part of their identity, they can choose to live in different ways including:

- moving regularly around the country from site to site and being ‘on the road’

- living permanently in caravans or mobile homes, on sites provided by the council, or on private sites

- living in settled accommodation during winter or school term-time, travelling during the summer months

- living in ‘bricks and mortar’ housing, settled together, but still retaining a strong commitment to Gypsy/Traveller culture and traditions

Currently, their nomadic life is being threatened by the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, that is currently being deliberated in Parliament, To find out more or get involved with opposing this bill, please visit here

Although Travellers speak English in most situations, they often speak to each other in their own language; for Irish Travellers this is called Cant or Gammon* and Gypsies speak Romani, which is the only indigenous language in the UK with Indic roots.

*Sometimes referred to as “Shelta” by linguists and academics

New Travellers and Show People

There are also Traveller groups which are known as ‘cultural’ rather than ‘ethnic’ Travellers. These include ‘new’ Travellers and Showmen. Most of the information on this page relates to ethnic Travellers but ‘Showmen’ do share many cultural traits with ethnic Travellers.

Show People are a cultural minority that have owned and operated funfairs and circuses for many generations and their identity is connected to their family businesses. They operate rides and attractions that can be seen throughout the summer months at funfairs. They generally have winter quarters where the family settles to repair the machinery that they operate and prepare for the next travelling season. Most Show People belong to the Showmen’s Guild which is an organisation that provides economic and social regulation and advocacy for Show People. The Showman’s Guild works with both central and local governments to protect the economic interests of its members.

The term New Travellers refers to people sometimes referred to as “New Age Travellers”. They are generally people who have taken to life ‘on the road’ in their own lifetime, though some New Traveller families claim to have been on the road for three consecutive generations. The New Traveller culture grew out of the hippie and free-festival movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

Barge Travellers are similar to New Travellers but live on the UK’s 2,200 miles of canals. They form a distinct group in the canal network and many are former ‘new’ Travellers who moved onto the canals after changes to the law made the free festival circuit and a life on the road almost untenable. Many New Travellers have also settled into private sites or rural communes although a few groups are still travelling.

If you are a new age Traveller and require support please contact Friends, Families, and Travellers (FFT) .

Differences and Values

Differences Between Gypsies, Travellers, and Roma

Gypsies, Roma and Travellers are often categorised together under the “Roma” definition in Europe and under the acronym “GRT” in Britain. These communities and other nomadic groups, such as Scottish and English Travellers, Show People and New Travellers, share a number of characteristics in common: the importance of family and/or community networks; the nomadic way of life, a tendency toward self-employment, experience of disadvantage and having the poorest health outcomes in the United Kingdom.

The Roma communities also originated from India from around the 10th/ 12th centuries and have historically faced persecution, including slavery and genocide. They are still marginalised and ghettoised in many Eastern European countries (Greece, Bulgaria, Romania etc) where they are often the largest and most visible ethnic minority group, sometimes making up 10% of the total population. However, ‘Roma’ is a political term and a self-identification of many Roma activists. In reality, European Roma populations are made up of various subgroups, some with their own form of Romani, who often identify as that group rather than by the all-encompassing Roma identity.

Travellers and Roma each have very different customs, religion, language and heritage. For instance, Gypsies are said to have originated in India and the Romani language (also spoken by Roma) is considered to consist of at least seven varieties, each a language in their own right.

Values and Culture of GRT Communities

Family, extended family bonds and networks are very important to the Gypsy and Traveller way of life, as is a distinct identity from the settled ‘Gorja’ or ‘country’ population. Family anniversaries, births, weddings and funerals are usually marked by extended family or community gatherings with strong religious ceremonial content. Gypsies and Travellers generally marry young and respect their older generation. Contrary to frequent media depiction, Traveller communities value cleanliness and tidiness.

Many Irish Travellers are practising Catholics, while some Gypsies and Travellers are part of a growing Christian Evangelical movement.

Gypsy and Traveller culture has always adapted to survive and continues to do so today. Rapid economic change, recession and the gradual dismantling of the ‘grey’ economy have driven many Gypsy and Traveller families into hard times. The criminalisation of ‘travelling’ and the dire shortage of authorised private or council sites have added to this. Some Travellers describe the effect that this is having as “a crisis in the community” . A study in Ireland put the suicide rate of Irish Traveller men as 3-5 times higher than the wider population. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the same phenomenon is happening amongst Traveller communities in the UK.

Gypsies and Travellers are also adapting to new ways, as they have always done. Most of the younger generation and some of the older generation use social network platforms to stay in touch and there is a growing recognition that reading and writing are useful tools to have. Many Gypsies and Travellers utilise their often remarkable array of skills and trades as part of the formal economy. Some Gypsies and Travellers, many supported by their families, are entering further and higher education and becoming solicitors, teachers, accountants, journalists and other professionals.

There have always been successful Gypsy and Traveller businesses, some of which are household names within their sectors, although the ethnicity of the owners is often concealed. Gypsies and Travellers have always been represented in the fields of sport and entertainment.

How Gypsies and Travellers Are Disadvantaged

The Traveller, Gypsy, and Roma communities are widely considered to be among the most socially excluded communities in the UK. They have a much lower life expectancy than the general population, with Traveller men and women living 10-12 years less than the wider population.

Travellers have higher rates of infant mortality, maternal death and stillbirths than the general population. They experience racist sentiment in the media and elsewhere, which would be socially unacceptable if directed at any other minority community. Ofsted consider young Travellers to be one of the groups most at risk of low attainment in education.

Government services rarely include Traveller views in the planning and delivery of services.

In recent years, there has been increased political networking between the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller activists and campaign organisations.

Watch this video by Travellers Times made for Gypsy Roma Traveller History Month 2021:

Information and Support

We have a variety of helpful guides to provide you with the support you need

Community Corner

Read all about our news, events, and the upcoming music and artists in your area

- 0 0 Your cart is empty Browse Shop

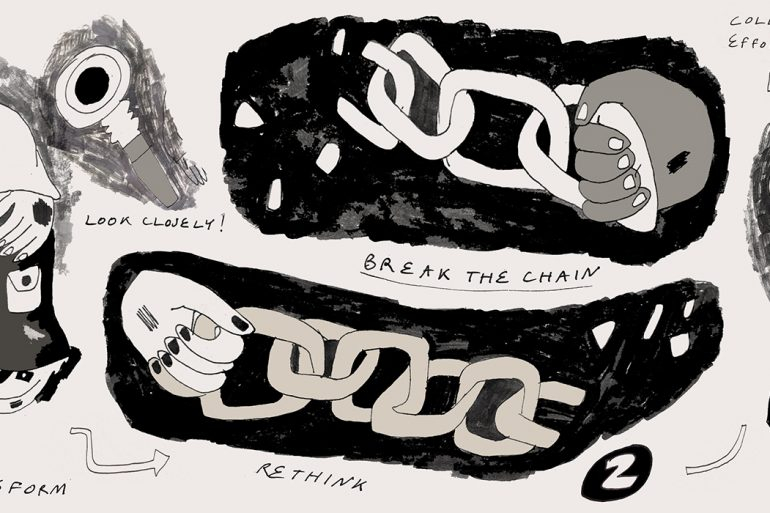

What is Gypsy and Traveller resistance?

Everything you need to know about Gypsy and Traveller resistance, the history of discrimination in the UK, current policies of oppression and resources to support the movement

When we think of resistance, our minds are too often drawn to significant displays in the form of mass protests and activism, but our existence as Gypsies and Travellers is already resistance.

The refusal to assimilate into societal norms, despite great pressure and state oppression, whilst maintaining our own distinct cultural identities, is an example of resistance in and of itself.

Gypsies and Travellers in the UK have long experienced state oppression through parliamentary bills which have sought to curtail the freedoms of Gypsies and Travellers and their right to roam. In spite of this Gypsies and Travellers, both in houses and on sites, have resisted assimilation through the maintenance of strong family connections, cultural traditions and through the preservation of accents and their own languages.

The refusal to adhere to the norm, and the taking and leaving of state structures depending on need, is what has allowed Gypsies and Travellers to survive. No doubt it is this resistance that will ensure the survival of Gypsies and Travellers into the next century, but it will need support from non-Traveller allies to ensure that Gypsies and Travellers are not harassed by further violent and discriminatory policies.

What is the history of travelling communities in the UK?

Romany Gypsies and Irish Travellers are historically nomadic communities, with some continuing to practise nomadism all or part of the year round.

Romany Gypsies originated historically from India and Irish Travellers came to the UK from Ireland and the two have co-existed in the UK since the early 19th century.

In more recent years, we have seen greater migration of Roma, especially from European countries to the UK.

Gypsies and Travellers have always existed in both rural and urban areas and historically engaged in seasonal trades such as fruit and vegetable picking, tinsmithing, horse trading and scrap metal recycling. Many Irish Travellers historically worked as navigators, building canals and railways and later on motorways and building sites. Some Gypsy and Traveller women would have sold heather, flowers and pegs.

There has been a lot of work done by Gypsies and Travellers in London to map their histories in the city and to put to bed the myth that Gypsies and Travellers only existed in rural areas.

People often hold a romanticised view of what they consider to be the ‘real’ Gypsies and Travellers of the years gone by with wagons and horses, whilst at the same time spouting hate and discrimination at Gypsies and Travellers with Transit vans and Hobby trailers.

It is rarely acknowledged that the same industrialisation and capitalism which radically changed the face of communities across the UK, has also done the same to ours.

In order to survive, Gypsies and Travellers have had to adapt – and this has meant shifting trades, locations and living units. Whilst wagons were and are works of art, they were also impractical as we shifted into the 21st century and people had to move with the times.

There is also no doubt that our children and grandchildren will do the same as we are faced with the growing impacts of climate change and the current housing crisis.

What state structures minoritise these communities?

State structures have long played a role in the minoritisation of Gypsy and Traveller communities. From the Egyptian Act of 1530 to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill of 2022 – the state has consistently tried to eradicate nomadism.

At present, the state’s refusal to cater for Gypsy and Traveller people in the form of sites and stopping places is a clear example of minoritisation in practice but the attitudes towards Gypsies and Travellers also prevails across sectors.

Whether it is housing, healthcare, policing or the service industry, there are endless examples of Gypsies and Travellers being refused service or provided with substandard care. It has left us in a position whereby we experience greater levels of incarceration, high suicide rates and poor health outcomes.

Moreover, in education the state refuses to provide support for Gypsy and Traveller families who are nomadic despite military families, whose kids also move schools a lot, being provided with support structures that we could only dream of.

In our criminal justice system, the courts view Gypsy and Traveller ethnicity as a risk factor, often using it to refuse bail or community sentence orders.

State structures don’t exist without the people who work to uphold the system, and it is through this that Gypsies and Travellers continue to be minoritised because the system doesn’t allow for anything else.

Discrimination across leftist spaces

The media and politicians play a big role in influencing public opinion regarding Gypsies and Travellers, and even in leftist spaces, Gypsies and Travellers can find themselves being used as a political football.

A few years ago, alongside the now redundant LabourGRT campaign, I spent a lot of time speaking on Gypsy and Traveller issues and the impact of the PCSC Bill. There were countless conversations and backlash from Labour MP’s when we called them out on campaign materials they were using.

Despite promises from Labour it is something that has continued to happen and with them whipping peers to abstain on part four of the PCSC Bill, my faith was lost.

It is disheartening for Gypsy and Traveller activists to go into campaigning and grassroots movements on the left and be met with stereotypes and discrimination – it feels like you are battling in a place that should find a political home in.

Abolitionist organising spaces is a place where Gypsies and Travellers can find greater cross-movement and cross-community solidarity. We saw this in the wake of the PCSC Bill with myself and other Gypsy and Traveller activists speaking at protests and discussing ways in which our movements could support each other.

When as a people you have been criminalised for hundreds of years, it is much easier to see not only the role of the police in oppression but also in seeing that there are ways of organising community and living that don’t rely on carceral institutions and thinking.

There is so much about the ways in which Gypsies and Travellers live and exist that can provide support to abolitionist imagining. The fact that we often live in extended family units and provide familial support that reduces the reliance on state institutions such as care homes and additional childcare, provides a model for a different way of living.

Using this knowledge we can support other movements as they explore what community and community support could look like outside of the bounds of the state. It provides a real opportunity to connect across struggles as we all fight for liberation.

How can people support the movement?

Movements are made up of lots of different people doing different things, some big and some small. If you are short on time and lacking confidence, learning more can be a great place to start. There are different resources out there but some of my favourites are included below. You can also follow different organisations and activists on social media and platform their voices and the work they are doing (especially that which is Gypsy and Traveller led!)

If you are currently engaged in social justice work, think about how you can include the voices of Gypsies and Travellers and the issues facing our communities, in your own work and spaces. Often people can view our issues in isolation, but they are tied up in broader social issues. We need non-Travellers to talk about the issues we are facing in order to create change. This can be done in your everyday work and in your spheres of influence – big or small.

How can you initiate conversations with friends and family members? How can you ensure that your workplace is inclusive of Gypsies and Travellers who may be interacting with it?

What can you do?

There are lots of different resources out there and probably not enough socialist resources but here are some podcasts, blogs and videos that provide greater insight:

- PODCAST: Radicals in Conversation – Gypsies, Roma and Travellers

- Growing up in the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller community:

- Chelsea McDonagh: Fighting for Traveller Education – The Plastic Podcasts

- How the Police Bill targets Gypsies, Roma and Travellers | rs21

- The PCSC Bill has failed Gypsies and Travellers – so where do we go next?

- “We Are People Too”: A blog by Chris McDonagh on growing up as an Irish Traveller

- Just About . . . Gypsy, Roma and Traveller People and Criminal Justice – SCCJR

- The Guilty Feminist: 248. Romany Women with Alison Spittle and guests Lolo Jones, Lisa Smith and Riah Knight

- Roads From The Past – Short Film – Travellers’ Times Online

What is the Decriminalisation of Sex Work?

What is Israeli Apartheid?

What is the UK Trade Union Movement?

What is seed sovereignty?

What is Eco-Anxiety?

What are Climate Reparations?

What are food systems?

What is the Green New Deal?

What is Greenwashing?

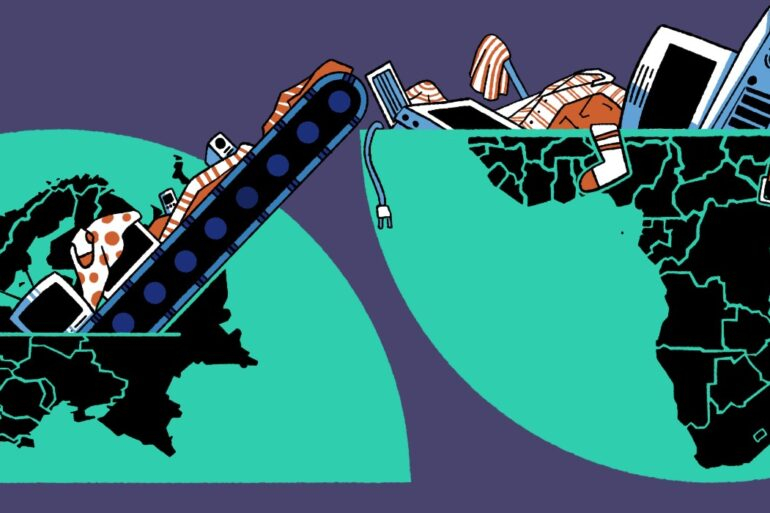

What is Waste Colonialism?

Why police will never be the answer to gendered violence

What is Health Justice?

Shado Newsletter

Email address:

I have read and agree to the privacy-policy

- Entertainment

Planned traveller camp near Battle of Shrewsbury site could see weapons and historic finds unearthed

An "archaeological watching brief" is to be undertaken if a temporary traveller camp near the Battle of Shrewsbury site gets planning permission.

Proposals have been submitted for land on the edge of Battlefield Industrial Estate to try and stop "unauthorised encampments" in the town.

However, given the rich history of the area due to the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, it has been recommended that archaeological work is undertaken.

A Shropshire Council archaeological report said: "The proposed developed site is located 400m south-west and within the setting of the registered battlefield for the Battle of Shrewsbury. It is understood that the proposed development site is currently in agricultural use as improved pasture.

"The registered battlefield is significant on account of its archaeological potential, military innovations, commemoration value and topographical integrity. The battlefield also holds group value with the Church of St Mary of Magdalene (grade II) and the College of St Mary of Magdalene (Scheduled Ancient Monument) which both lie within its boundary.

Warehouse to be built on former Shropshire Star site in Telford after plans approved Telford | 3 hours ago

Woman arrested after car and patient transport vehicle involved in crash Plus Shrewsbury | 4 hours ago

27 dogs in Shrewsbury looking for their 'forever home' Viral news | Apr 28

Telford police seize car and report driver who allegedly had illegal number plate Telford | 2 hours ago

Telford shoplifter targeted Asda four times in four days - stealing speakers and steaks Plus Crime | 8 hours ago

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘My example can change minds’: Roma fighting for place in postwar Ukraine

Campaigners across Europe call on Kyiv to recognise contribution of marginalised community

- Ukraine war – live updates

G rowing up in Ukraine , Arsen Mednik often found himself singled out – at school children would point at him, calling him “gypsy”, while employers were often reluctant to hire him when they learned he was Roma.

But in early 2022, as Russian forces began their savage occupation of his home town of Bucha, Mednik was among the first Ukrainian Roma to volunteer in the defence of the country.

“My only thought was that I wanted to defend people,” he said. “The Russians weren’t paying attention to who was Roma or Ukrainian. They just killed everyone.”

The 34-year-old is among the many Roma people on the frontlines of the war on Ukraine, risking their lives despite their own personal experiences of marginalisation and wider concerns over whether they will have a place in the country when the war ends.

Exact figures of how many from the community are fighting are hard to come by, but it is estimated that there are a few thousand, said Stephan Müller, an adviser on international affairs with the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma.

The actual number among the country’s estimated 400,000 Roma could be even higher – a recent survey of 143 Roma in Ukraine by the Roma Foundation for Europe found that a quarter of respondents had relatives on the frontlines. Of these, a third were volunteers.

It’s a remarkable contribution given that Roma, whose roots in Ukraine trace back centuries, rank among the country’s most discriminated against , complicating their access to decent housing, jobs, healthcare and schooling.

In the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Roma were targeted regularly by far-right groups, resulting in the deaths of at least two people and leading Amnesty International to warn in 2019 that “attacks against Roma are becoming increasingly vicious in Ukraine” and urge that perpetrators be brought to justice.

“There is strong antigypsyism in Ukraine, we shouldn’t deny that,” said Müller. “But despite all of this racism, Roma are standing on the side of Ukraine and fighting.”

Müller is among the campaigners across Europe who are calling on Ukraine to recognise the contributions of Roma and do more to secure their place in the country once the war ends. Their efforts are guided by recent history, in which Roma were often expelled or excluded from reconstruction efforts following periods of war.

“So in Kosovo, for example, more than 100,000 – almost two-thirds of the Roma population – were expelled primarily after the war,” said Müller. Some were targeted by violence, forcing them to flee, while others ended up displaced after unequal treatment by authorities.

In Ukraine, Roma who are not on the frontlines have sought to contribute in other ways, said Müller, citing fundraising efforts to purchase army equipment, Roma artists who are holding concerts for the army and Roma-led NGOs who are serving up free meals to non-Roma who are in need.

“This has to be made public,” he said. “And has to be acknowledged, recognised and properly rewarded in a postwar period. Rather than wreak havoc and violence against Roma or expel them.”

The efforts to highlight Roma contributions to the war efforts have come up against the stereotype-heavy coverage of the community by many in mainstream media, said Nataliia Tomenko of ARCA, an agency that supports Roma youth and works to preserve Roma history and culture in Ukraine.

“In general, when they talk about communities in Ukraine, it’s not on the level it should be,” she said. “There is no positive representation.” Her organisation has sought to combat this by spotlighting the stories of several Roma soldiers on its website.

The government in Ukraine has also made some efforts to this end, recognising the contribution of minorities, including Roma, to the country’s defence in state programmes and bestowing an award for bravery to Viktor Ilchak, a Roma soldier from western Ukraine, last year.

after newsletter promotion

Campaigners have warned that Ukraine’s national recovery plan fails to meaningfully address many of the distinct issues faced by Roma, such as those who live in informal housing without ownership documents, potentially complicating access to compensation or financial assistance for rebuilding, to those who lack the documents needed to prove their citizenship or residence status.

Postwar plans also need to take into account the disproportionate effect that the war has had on many in the Roma community, said Anzhelika Bielova, the founder of Voice of Romni, an organisation working to empower Roma women in Ukraine.

“The vulnerability of already-vulnerable groups was amplified,” said Bielova, whose organisation has shifted to providing humanitarian aid since the war began.

“The majority of Ukrainians have better access to services and information than the Roma community, which is in a vulnerable situation,” she said, citing the lack of internet access and information on available resources that affect many in the community.

The invasion came on the heels of the coronavirus pandemic, both of which forced many schools in the country to shift classes online. Grappling with a lack of technology such as laptops and smartphones, many Roma children were locked out of learning, giving rise to a void that could seriously affect their future but also their postwar role in the country.

Few organisations – whether in Ukraine or outside – have addressed these issues, she said. “In parts of Roma settlements in western Ukraine, people are living in awful conditions, without gas, without heat and without access to water,” she added. “And they’re invisible to humanitarian actors.”

After spending the first days of the war digging trenches in and around Kyiv, Mednik eventually joined the army.

Standing shoulder to shoulder with others in Ukraine, he saw much of the discrimination he had wrestled with his whole life melt away. “People who get to know me, they have a good opinion about Roma,” he said. “I realised that my example can change people’s minds.”

In September, as he crouched in a trench near Kherson, he was hit by an unidentified object, leaving him in a coma for 20 days. When he woke up, he learned he had encephalitis, shrapnel in his lungs and had lost several of his fingers as well as much of his hearing.

After three months of rehabilitation, Mednik returned to the army, helping to coordinate air defence operations. “I have to show a good example for Ukrainians, to show that Roma can fight, not only for themselves but also for other Ukrainians,” he said.

What kept him going, even as exhaustion sets in for many across Ukraine, was his deep desire to defend people. “I’m proud to be Roma. We’re an ancient people, with a history and a culture to match. We’re not military people, we’re a people of peace,” he said. “But in this case, when someone comes to kill me, my family, my friends, I decided to fight. I’m proud to defend people and proud to be Roma.”

- Roma, Gypsies and Travellers

Irish Traveller compensated after Conservative club refused to host christening party

Tory party urged to investigate Welsh secretary’s ‘racist’ leaflet about Travellers

Welsh secretary has ‘history of hostility’ towards Traveller communities

Police investigate Traveller sites leaflet distributed by Welsh secretary

Gypsy, Roma and Travellers suffer ‘persistent’ discrimination in UK

‘We need to get out!’ How Gypsy families were driven out of Spanish town by mob

‘It’s traumatic’: new travellers’ Dorset home challenged by Martin Clunes

Social barriers faced by Roma, Gypsies and Travellers laid bare in equality survey

Greene King pays damages after Irish Travellers refused service at pub

Pontins under investigation over treatment of Travellers

Most viewed.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Irish Travellers (Irish: an lucht siúil, meaning the walking people), also known as Pavees or Mincéirs (Shelta: Mincéirí) are a traditionally peripatetic indigenous ethno-cultural group originating in Ireland.. They are predominantly English speaking, though many also speak Shelta, a language of mixed English and Irish origin. The majority of Irish Travellers are Roman Catholic, the ...

SUBSCRIBE HERE: http://bit.ly/2ol5mam For generations, groups of travellers have spent their lives on the move, invading public parks and illegally squattin...

Roma, Romany Gypsies, Manuches, Kale and Sinti and people with Roma descent live in various countries across the world. There are more than 10 million people of Romani descent in Europe alone. Romani is a rich family of languages with an Indo-Aryan root. Romani is the only Indio-Aryan language that has been spoken exclusively in Europe since ...

Gypsy and Traveler Groups in the United States. Cale: Spanish Gypsies, or Gitanos, are found primarily in the metropolitan centers of the East and West coasts. A small community of only a few families. English Travelers: Fairly amorphous group, possibly formed along same lines as Roaders (see below), but taking shape already in England before ...

Shelta (/ ˈ ʃ ɛ l t ə /; Irish: Seiltis) is a language spoken by Mincéirí (Irish Travellers), particularly in Ireland and the United Kingdom. It is widely known as the Cant, to its native speakers in Ireland as de Gammon or Tarri, and to the linguistic community as Shelta. Other terms for it include the Seldru, and Shelta Thari, among others.The exact number of native speakers is hard to ...

Irish Travellers speak English as well as their own language, known variously as Cant, Gammon, or Shelta. Cant is influenced by Irish and Hiberno-English and remains a largely unwritten language. According to the 2016 census, there were nearly 31,000 Irish Travellers living in the Republic of Ireland, representing 0.7 percent of the population.

Romanichals (UK: / ˈ r ɒ m ə n ɪ tʃ æ l / US: /-n i-/; more commonly known as English Gypsies) are a Romani subgroup within the United Kingdom and other parts of the English-speaking world. Most Romanichal speak Angloromani, a mixed language that blends Romani vocabulary with English syntax. Romanichals resident in England, Scotland, and Wales are part of the Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller ...

Arthur Harding's classic account of the East End underworld at the beginning of the 20th century, compiled by the historian Raphael Samuel, revealed in passing how Gypsy Travellers were part of the everyday fabric of poor urban life. David Mayall's work on the 19th century, my own on the 20th and that of the Dutch scholars Lucassen, Willems ...

The son of Irish Travellers who arrived in East London in the 80s, a soft Irish accent has stayed with Mongan who was brought up in a large Traveller site in Hackney Wick. ... Working for the Gypsy Traveller Leauge (GTL), he aims to break down cultural barriers and challenge the perception of Travellers. Mongan is something of a chameleon and ...

Gypsies, Roma and Travellers have a rich and diverse culture. Gypsy Roma and Traveller people belong to minority ethnic groups that have contributed to British society for centuries. Their distinctive way of life and traditions manifest themselves in nomadism, the centrality of their extended family, unique languages and entrepreneurial economy.

First segment of a two part (2 x hour) documentary tracking down the decedents of Irish travellers (Gypsies) living in the Southern US States.

Irish Traveller culture is known to date back at least to the 11th century. Many New Travellers chose a travelling generation. Roma are Romany people from central and eastern Europe. Other Travellers include Showmen, Bargees and Circus people Around 300,000 Gypsies and Travellers live in the UK. Around 200,000 live in

In spite of this Gypsies and Travellers, both in houses and on sites, have resisted assimilation through the maintenance of strong family connections, cultural traditions and through the preservation of accents and their own languages. The refusal to adhere to the norm, and the taking and leaving of state structures depending on need, is what ...

A term used to refer generally to communities who are not of Gypsy or Traveller ethnicity, sometimes referred to as "countrymen", "gorgers", "non-Gypsy" and "non-Travellers". Sites. Gypsy and Traveller sites are authorised places of residence which may be owned and managed by the council or privately. Back to table of contents

Irish traveller explains the tradition of 'grabbing' in the gypsy community. Subscribe for more! https://bit.ly/3ManoGPClick here for more Gypsy Weddings: ht...

The Traveller accent is pretty unique, and the show did a good job of reproducing it. The underlying joke is that many people find the Traveller accent harsh and intimidating, and Irish people tend to regard the Traveller community with distrust and assume they're always up to the worst. The girls getting terrified and misreading all the signs ...

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (abbreviated to GRT) is an umbrella term used in the United Kingdom to represent several diverse ethnic groups which have a shared history of nomadism.The groups include Gypsies, defined as communities of travelling people who share a Romani heritage, resident in Britain since the 16th century; Ethnic Travellers, the traditional travelling people of Ireland and ...

Only 184 Gypsy and Traveller students were registered in higher education in 2018-19, ... "I used to try to change my accent so I wouldn't be stereotyped and unfortunately, 20 years later, I ...

British Gypsies are white in appearance due to mixed marriages with Gaelic Travellers, Funfair Travellers and even non-Travellers over the centuries. Northern and Southern Romanichal Gypsies speak different dialects of Angloromani, so I coloured them different shades of red. Anglormani is a mix of English and Romani.

Some like to call Irish Travellers Gypsy to try to say we are outsiders like the ones from Egypt. Its judt a way to rile us up. To pretend we came from Egypt when we didnt. ... English Traveller; pale skin; English accent. Irish Traveller in England; will still have an irish accent despite maybe never being in Ireland as all older family have ...

Ellesmere Road, Shrewsbury, the site of a proposed temporary Gypsy Traveller site. Photo: Google Proposals have been submitted for land on the edge of Battlefield Industrial Estate to try and stop ...

Pikey (/ ˈ p aɪ k iː /; also spelled pikie, pykie) is an ethnic slur referring to Gypsy, Roma and Traveller people.It is used mainly in the United Kingdom and in Ireland to refer to people who belong to groups which had a traditional travelling lifestyle. Groups referred to with this term include Irish Travellers, English Gypsies, Welsh Kale, Scottish Lowland Travellers, Scottish Highland ...

Gypsy, Roma and Travellers suffer 'persistent' discrimination in UK. 25 May 2023 'We need to get out!' How Gypsy families were driven out of Spanish town by mob. 7 May 2023

when a gypsy traveller encounters the hardest bouncer in the uk, opposing worlds don't agree with each other, and let's just say it doesn't end well.