Paimio Sanatorium

Address: Alvar Aallontie 275, 21540 Paimio, Finland Open Google map

Entrance fee: 10-25€ / person

Tours: Information about guided tours and accommodation on Paimio Sanatorium’s website

Themes: Hospitals, Modernism, Nature

Website: Alvar Aalto Foundation

The building completed in 1933 as Paimio Sanatorium was of key importance to the international career of architects Alvar and Aino Aalto. Together with Vyborg (Viipuri) Library, completed two years later, it gave the Aaltos an international profile. Finnish architecture was no longer merely the receiver of influences from outside.

The building, constructed on the basis of their win in an architectural competition resolved in 1929, was groundbreaking. A tuberculosis sanatorium was particularly suitable for a building which followed the tenets of the new Functionalism, where bold concrete structures and state-of-the-art building services were inseparable elements of architecture and practicality.

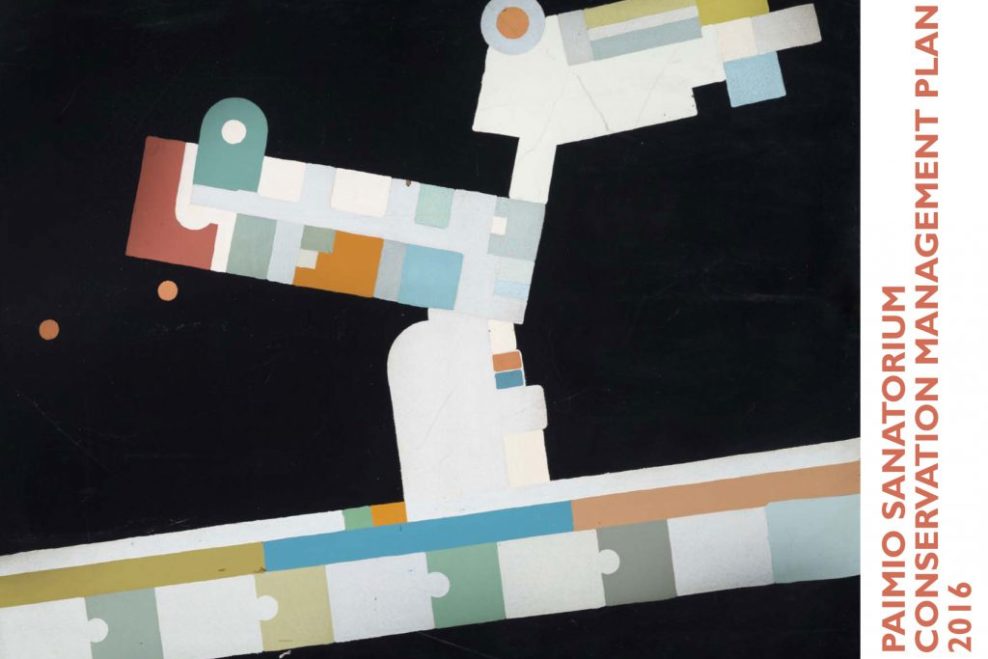

Aalto designed the interior colour scheme, including the yellow floors in the main staircase, the colourful walls in the corridors, the dark ceilings in the patients’ rooms and the orange balcony rails, in conjunction with the decorative artist Eino Kauria.

The entire building complex, grouped together in several parts according to use, was constructed in accordance with Aalto’s philosophy, right down to the smallest details of the furniture. As far as the loose furniture was concerned, a good many items designed specifically for the sanatorium were used, as well as standard products which were already available. According to the idea of standardisation, which belonged to the spirit of the times, these items were also planned for use elsewhere – for example, many of the light fittings ended up in the catalogue of the Taito metalworks.

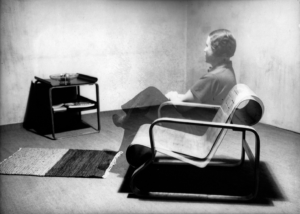

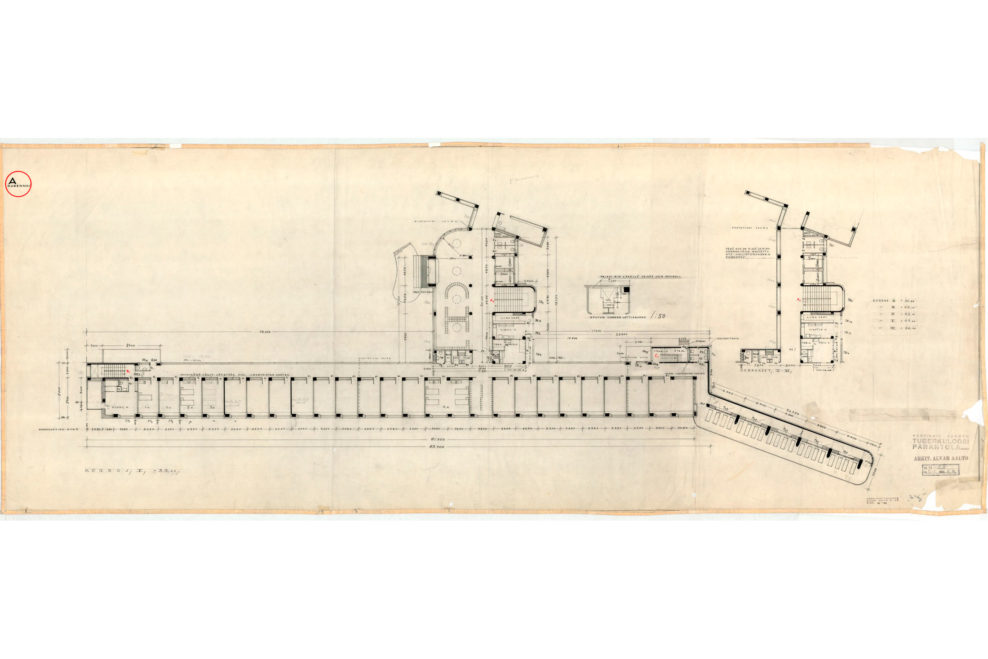

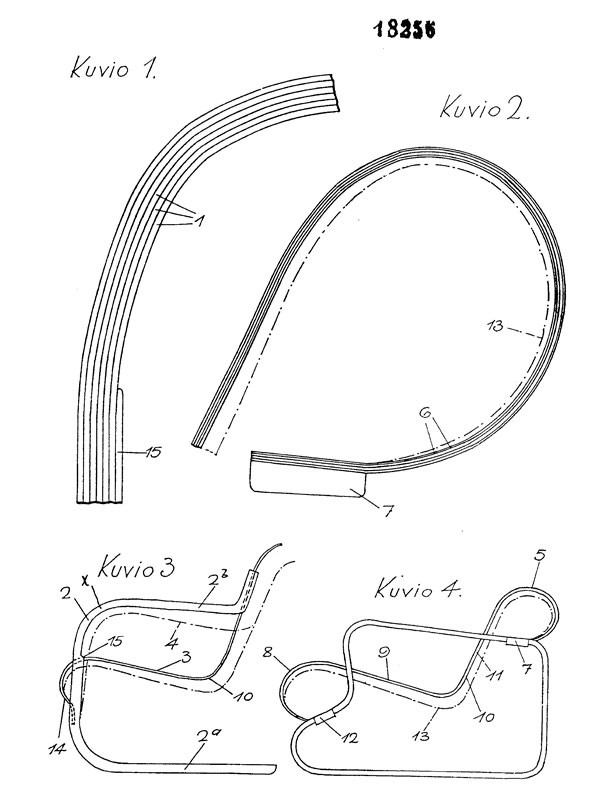

The pieces of furniture became key products for Artek, which was founded in 1935. The bent plywood Paimio chair in particular has become an international design icon. On the other hand, the three-legged stool, which is the same age as the sanatorium, was not included in the first phase of the furniture supplied by the Otto Korhonen furniture works. The furniture in the patients’ rooms was dominated by tubular-steel construction, soon to be spurned by the Aaltos.

An operating theatre wing designed by Aalto’s office was added to the main building in the late 1950s and new staff living-quarters were erected nearby in the 1960s. The sinuous, serpentine row of shared flats in the middle of the pine forest, known to the inmates as the ‘Hall of Vipers (Kyykartano), brought a new form of accommodation to the area.

Paimio Sanatorium is located in the middle of pine trees. Photo: Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

The color schemes of Paimio Sanatorium were co designed with Eino Kauria. Photo: Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Paimio Sanatorium is a total work of art that radiates human-nature connection, where architecture is an instrument of healing.

Information for visitors

Good to know.

Arriving to Paimio

Paimio is located in between Turku and Salo, approximately 140 kilometers away from Helsinki and 30 km from Turku. You can reach Paimio with a car or take a bus from Helsinki. Bus from Helsinki to Paimio stops at a bus stop called “Paimio motorway junction 11”. Order a taxi by dialling number +358 21 0041. Please note: there is limited availability of taxis so pre-ordering is advisable.

You can also take a train or a bus to Turku from Helsinki. From Turku you can take a local bus to Paimio city. Please note that the schedule for the bus is very irregular, especially during the summer. It takes approx. 1 hour to travel. Please check the timetables in advance at Matkahuolto or at local traffic site Föli . Some local buses take you directly to the sanatorium but some of them only stop at the centre of Paimio, approximately 3 kilometres away from the Paimio Sanatorium. From the centre you can call a taxi (with your mobile phone) by dialling number +358 21 0041.

Please note that the Sanatorium is in Finnish Paimion parantola, but the road signs, and the timetables state Paimion sairaala (Paimio hospital).

Paimio Sanatorium is located on Alvar Aallontie 275. Please note that you can only visit the building with a guided tour. The tour operator is Magni Mundi and you can find more information about the tours and prices on their web site.

Read more about the services and sights in Paimio.

Please note that you can purchase publications about Paimio’s Sanatorium from Alvar Aalto web shop!

Guided tours

Further information.

Guided tours:

Information about guided tours and accommodation on Paimio Sanatorium’s website.

- Login / Register

- You are here: Buildings

Revisit: ‘Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium continues to radiate a profound sense of human empathy’

17 November 2016 By Ellis Woodman Buildings

Completed in 1932, Alvar Aalto’s Paimio tuberculosis sanatorium’s programme was revolutionary

Tuberculosis may have blighted mankind since at least as far back as antiquity, but when the AR devoted its September 1933 issue to a survey of recent tuberculosis sanatoriums, it turned its attention to a building type with a far shorter history. The sequestering of TB patients only became common practice after the disease was discovered to be contagious in the 1880s. An argument for the rehabilitative effects of exposure to light and air lent weight to the subsequent construction of residential facilities in often very remote locations. However, the success of such treatment was at best partial: to enter a sanatorium in the first decades of the last century was to face a 50 per cent likelihood of death within five years. It was only with the discovery of the antibiotic streptomycin in 1946 that patients finally began to have access to an effective cure.

Among the buildings featured in the AR’s survey, none was of more pioneering design than the facility that Alvar Aalto had completed earlier that year at Paimio in Finland. In an article that concludes by lauding the project as ‘the most revolutionary hospital building erected within the last decade’, P Morton Shand catalogued its numerous technical innovations, from its optimisation of daylight, heating and ventilation to its structuring of the patient’s social interactions over the course of what would frequently prove a stay of years. This was a work of architecture that addressed its programme with quasi-scientific rigour. As Aalto himself would later explain: ‘The main purpose of the building is to function as a medical instrument.’

Kauria colour chart credit artist eino kauria.

Source: Eino Kauria

Having secured independence from Russia in 1917, the Finns rapidly committed themselves to a nationwide programme of public construction in which regional hospitals, old people’s homes, mental health facilities and tuberculosis sanatoriums featured prominently. By the early 1930s, the country had established 3,700 patient places for victims of lung tuberculosis. Such projects not only represented the building blocks of an aspiring welfare state but provided one of the central means by which Finland consolidated its nascent national identity. A progressively minded young architect could hardly wish for a more sympathetic environment in which to embark on a career.

Aalto was 30 when he won the competition for the Paimio Sanatorium in 1928, by which point he had already secured a substantial reputation within Finland through projects such as the Workers’ Club (1924-25) and Defence Corps Building (1926-29) both in his home city, Jyväskylä. These employed a spare Neoclassical style that related closely to work being built by Asplund and Lewerentz across the border in Sweden. However, with the design for the concrete-framed and strip-windowed headquarters of the Turun Sanomat newspaper in Turku (1927-29), Aalto had recently undergone a Damascene conversion to the Functionalist cause. At Paimio that newfound enthusiasm came into full bloom.

Paimio sanatorium2

Source: Leon Liao

Lying a two-hour drive west of Helsinki, Paimio is a rural municipality that coalesces into something that might plausibly be termed a town only for the extent of a couple of intersecting streets. The sanatorium stands a judicious three kilometres away, set within a vast encompassing swathe of forest. Original photographs show distant views of the main seven-storey building towering above the treetops like a fairy-tale castle. However, the forest has long since grown to approximate the level of its uppermost storey, effectively concealing the facility from visitors until they have progressed part-way up its drive.

Aalto remained closely involved with additions and alterations to the building throughout his life, the most substantial being an operating theatre built in 1955. However, in the 1970s the building was converted for use as a general hospital and was earlier this year taken over by an agency that helps children dealing with mental and physical handicaps. Both functions necessitated changes to the fabric but, thanks to the close monitoring of Finland’s National Board of Antiquities, its external aspect and communal interiors survive in remarkably good condition.

Paimio sanatorium interior 2

Source: Leon Liao

Approaching through the woods, the visitor passes between brief outlying terraces housing the sanatorium’s senior staff, planned so as to present no view of the main building. They share this very much larger structure’s expression in white-painted concrete offset by brightly coloured metalwork and projecting blinds – a treatment that contrasts dramatically with the trees. The main building stands on the highest part of the 40-hectare site and takes the form of a free composition of linked wings. Each serves a distinct function – an arrangement intended to minimise the spread of disease and disruption to patients – and is distinguished formally by its unique orientation, massing and fenestration. We first encounter three of these blocks ranged around an entrance forecourt, its deep and splaying plan seemingly offering a gesture of embrace.

To one side lies the wing housing the wards and to the other that containing communal facilities including a dining room, library, recreation space and workshops. At the far end they intersect with the central block in which the foyer and principal means of vertical circulation are contained. Paimio is a transitional building in its architect’s development, offering little indication of the romantic form-language of Aalto’s mature style. However, the curvaceous, black-painted concrete canopy that cantilevers over the entrance door offers one significant departure from the orthogonal. The associations evoked by such forms in Aalto’s later work are to elements of the natural world but, if an anecdote relayed to me by the building’s current caretaker is to be believed, the canopy’s form derives from a more ghoulish source: a bisected blackened lung.

The seven-storey wing housing the wards is by some distance the largest. Accommodating 145 rooms ranged along single-loaded corridors, it is startlingly tall, long and skinny. The wing is oriented so that each room enjoys a south-south-west orientation through a deep-set window that extends from floor to ceiling. A central line of concrete columns allows the corridors to be cantilevered: a feat registered by the continuous strip window that extends along each one. The wing’s more prominent end is given particularly dynamic expression through the provision of a glazed lift – the first use of such technology in Finland – bracketed by cantilevered balconies to either side. These represent the most intimately scaled of a range of terraces to which patients had access. The average temperature in Paimio drops to -6°C in February but fur-lined sleeping bags were on hand to encourage use of external areas across the year.

The wing’s other end terminates in a stack of dramatically cantilevered decks – originally open but now glazed in – that cranks in plan to face due south. Here, weaker and more infectious patients spent part of the day lying in groups of 24. Those in better condition gathered – as many as 120 at a time – on the wing’s full-length roof terrace. Stripped of its soundtrack of coughing and the unfortunate fibrous cement canopy that was added later to fend off snow, the space encountered in the original photographs conjures an ocean-liner glamour. It was even equipped with a flag that was raised whenever a patient returned to health. Aalto developed the building’s unusual variety of communal spaces – both internal and external – with the aim of offering patients control over their relationship to the wider community. ‘The idea, it is perhaps hardly necessary to add, was an architect’s not a doctor’s,’ he observed in the Morton Shand article. ‘The doctors fail to understand it. Whether the medical profession will end by adopting it remains to be seen.’

200px paimio hospital 1978

The building is a true gesamtkunstwerk, every detail from door handles to lighting to furniture having been custom-developed by Aalto, working in close collaboration with his wife, Aino. The most celebrated product of that endeavour remains the Paimio chair which was designed for use in the recreation area and which is still produced by Artek. Inspired by Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel Wassily Chair of 1927-28, Aalto’s version represented an innovative demonstration of the possibilities of bent plywood technology. Although famed for its dramatic sculptural form, the design was closely wedded to considerations of comfort. The choice of plywood was led by the material’s natural feel and insulating qualities, while the angle of the seat and back were intended to aid patients’ breathing.

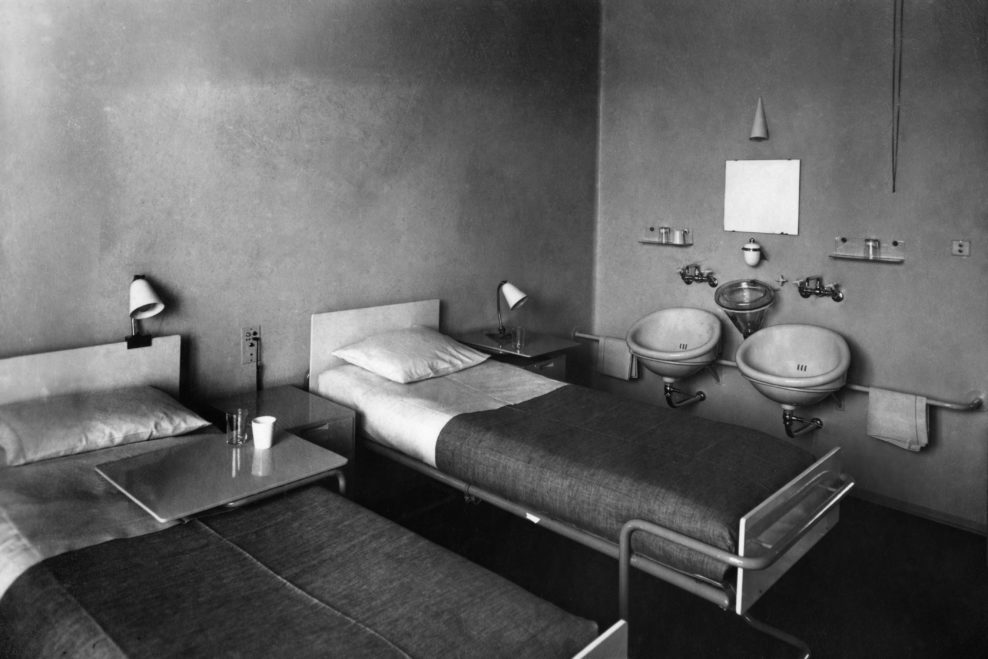

The most ample evidence of Aalto’s attention to detail was to be found in the wards of which only one now survives in its original form. Their principal innovation was their scale: accommodating two patients each, they were significantly smaller than the norm. However, the architect’s care for the wellbeing of patients was imprinted on every last component of these intensely conceived interiors. In response to Finland’s punishing winters, each window was designed as an assembly of two individually framed layers separated by a wide gap. The offsetting of their opening casements enabled ventilation to be introduced without generating a draft. The beams picking up the edge of the slab were inverted, allowing the windows to be set flush to the ceiling and thus to provide the deepest possible penetration of daylight. At the base of the window, the floor was curved up to cover the resultant upstand – a detail that provided better light reflection and facilitated cleaning. Despite the presence of the upstand and that of a built-in plywood desk, the window extended sufficiently low so as to allow patients a view of the surrounding grounds while lying in bed. Now sadly erased, the lawn outside featured a serpentine path that wove repeatedly back and forth with fountains located at the turning points.

Source: Alvar Aalto Museum

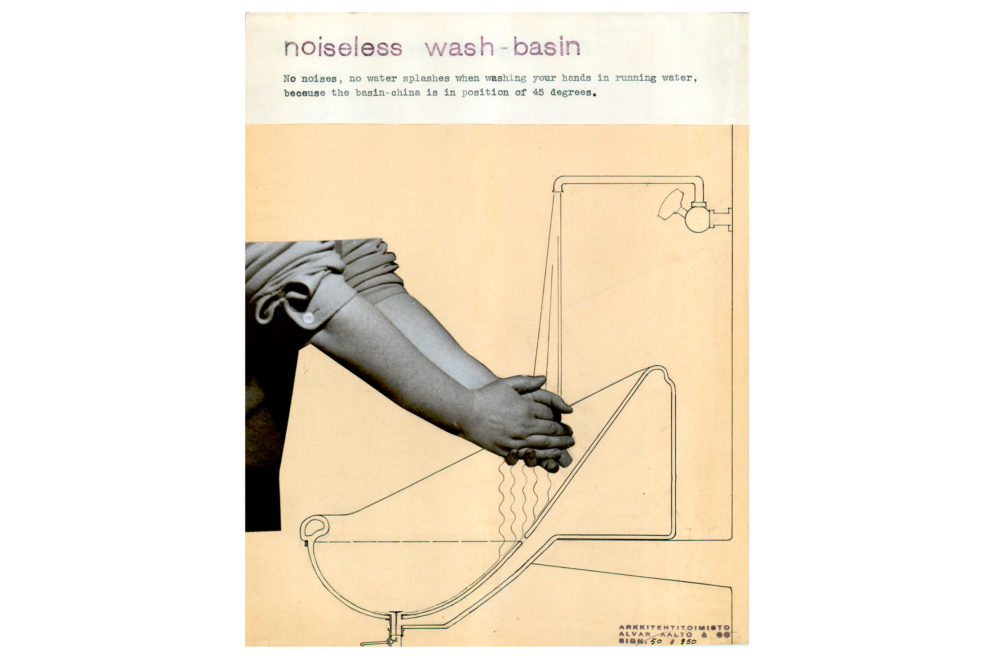

The window’s asymmetrical siting within the wall was also carefully considered to maximise morning light while restricting the admission of the sun during Finland’s long summer evenings. Heating panels were ceiling-mounted so as to be located at the greatest possible distance from the recumbent patients while one wall was lined in a soft insulation material to enhance the room’s acoustic. Wall-mounted sinks – paired to either side of a conical glass sputum cup – were also designed with noise in mind: their rear surface was set at a 30 degree angle, chosen after tests established that it resulted in the quietest performance. The walls and the equipment that they supported were white but the floor, ceiling and other furnishings offered a heightened restatement of the colours of the surrounding landscape. Pistachio green extended across the ceiling save for a half-circle of white that provided a reflective halo for the room’s principal light. Wall-mounted behind the patient’s heads, it was located so as to impact minimally on their field of vision.

‘The sanatorium cannot easily be characterised as an embodiment of the CIAM doctrine of pared-down standardisation’

In 1929, the year in which the construction of the sanatorium commenced, Aalto became a member of CIAM and attended the group’s second meeting at Frankfurt-am-Main. The appropriate standards of the Existenzminimum was the theme under discussion but Aalto proved one of a small number of vocal dissenters from such a reductionist mindset. Throughout the Paimio building we find evidence of his embrace of the possibilities of industrialised mass production and his belief in a design methodology rooted in scientific analysis. Yet for all that it deserves to be viewed as one of the principal monuments of the International Style, the sanatorium cannot easily be characterised as an embodiment of the CIAM doctrine of pared-down standardisation.

Paimio sanatorium 2 credit gustaf welin alvar aalto museum

Source: Gustaf Welin / Alvar Aalto Museum

Paimio sanatorium 1 credit gustaf welin alvar aalto museum

Source: Gustaf Welin / Alvar Aalto Museum

The similarly heliotropic arrangement of white concrete volumes that constitutes Duiker and Bijvoet’s 1925-31 Zonnestraal Sanatorium at Hilversum has often been claimed as an influence on Aalto’s building but, as Edward R Ford argues in The Details of Modern Architecture Volume 2: 1928 to 1988 , the relationship between structure and programme adopted at Paimio is markedly dissimilar from that of the earlier project. Zonnestraal’s structural frame follows an insistent and unwavering module dictated by an ambition to minimise the use of concrete while near continuous bands of glazing maintain a reading of the frame at all times, admitting no ambiguity about its autonomy from the non-loadbearing envelope. At Paimio, each wing employs a different structural grid in response to programmatic needs, while a far from continuous glazing treatment sacrifices structural purity in the interests of enabling each space to be oriented to a particular aspect. Aalto argued that the varying orientation of the communal spaces was especially valuable as it ensured that patients could find a place to rest either in or out of the sun at all times of the day. The architect was even content to abandon the structural logic governing each wing when the occasion demanded: the library in the communal block is hung from steel posts to allow the dining room that extends beneath it to remain column-free. The contrast between Paimio’s long-established adaptability and the near terminal dereliction into which Zonnestraal fell within 30 years of its construction speaks volumes about the relative robustness of the two approaches.

In his 1955 essay ‘Art and Technology’, Aalto relates the story of his participation as a juror at a student’s presentation of the design for a children’s hospital. The hapless speaker spent a considerable length of time detailing the myriad technical criteria that had informed his project. Aalto then responded: ‘You have apparently still left out at least one possibility. How would the building and the sick children in it function if a wild lion jumped in through one of the windows? Would the dimensions be suitable in such a case?’

As of yet, the Paimio Sanatorium has been spared trial by marauding predators but 81 years of varied use have proved it to be much more than a precise answer to a set of reductive functional requirements. Privileging the individual’s experience in his approach to every design problem, Aalto produced a building that transcended the brittle architectural doctrines of its period and which continues to radiate a profound sense of human empathy today.

November 2016

Since 1896, The Architectural Review has scoured the globe for architecture that challenges and inspires. Buildings old and new are chosen as prisms through which arguments and broader narratives are constructed. In their fearless storytelling, independent critical voices explore the forces that shape the homes, cities and places we inhabit.

Join the conversation online

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Alvar Aalto's Paimio Sanatorium in Finland

By Lee F. Mindel, FAIA

Nestled in the woods in southwestern Finland is the Alvar Aalto–designed Paimio Sanatorium, to me one of the most impressive buildings of the 20th century. Completed in 1933, the former tuberculosis sanatorium is a work of both art and science. It’s a cathedral to health and an instrument for healing. Aalto’s design, which was the winning entry for a 1929 competition, succeeds on both a macro and micro scale, seamlessly integrating the forested landscape with the architectural site plan and the interiors. (Aalto and his first wife, Aino, crafted all of the facility’s furniture, much of which is still available from the Finnish furniture company Artek .) On a recent visit, I was struck by the incredible care that went into Aalto’s fully articulated layout, which includes dramatic balconies (plenty of rest and sunshine was thought to be the best cure for tuberculosis during most of the early part of the 20th century), a double-height cafeteria, meeting rooms, a chapel, public spaces, staff housing, and walking trails throughout the surrounding forest. The patients’ rooms themselves received particular consideration. Because each space was originally designed to house two convalescents, Aalto created special no-splash sinks that would allow users to wash without disrupting the other. Lighting is located up high or down low, never at sight lines. Soothing, non-glare colors are utilized throughout the building—see the pale-yellow staircases and soothing blue common spaces. Windowed rooms connect to the landscape. A building for the ill becomes an inspiration for life.

Click to see some of my favorite photos from my visit to the Paimio Sanatorium.

More on archdigest.com:

Step inside Le Corbusier's family home in Switzerland, La Maison Blanche

Don't miss Lee F. Mindel's photographic tour of the showstopping architecture of Brasília

By Michelle Duncan

By Katherine McLaughlin

By Mayer Rus

By Sarah Archer

Paimio Sanatorium, 1929–33

To design the Paimio Sanatorium, Alvar and Aino Aalto leveraged the best science available at the time, which called for cross-ventilation and heliotherapy (exposure to sunshine) to treat and prevent tuberculosis. They considered everything from chairs and sinks to closets and beds. Sinks with angled basins were designed to minimize the sound of splashing water. Nonporous flooring and curved surfaces were easy to clean. Verandas were designed for resting outdoors.

The design of the Paimio Sanatorium was functional yet affirmed the presence of individuals. The embrace of light, air, cleanliness, and access to the outdoors in sanatoriums inspired sweeping changes in the design of homes and cities.

Content from the exhibition Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics , curated by MASS Design Group and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Paimio Sanatorium, Paimio, Finland, 1929–33 Alvar Aalto (Finnish, 1898–1976) and Aino Aalto (Finnish, 1894–1949)

Paimio Sanatorium, Paimio, Finland, 1929–33; Photograph: Building A to the south and the water pool, Gustaf Welin, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Photograph: Solarium Terrace, 1934, Gustaf Welin, Alvar Aalto Foundation

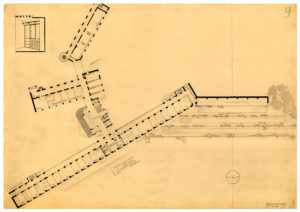

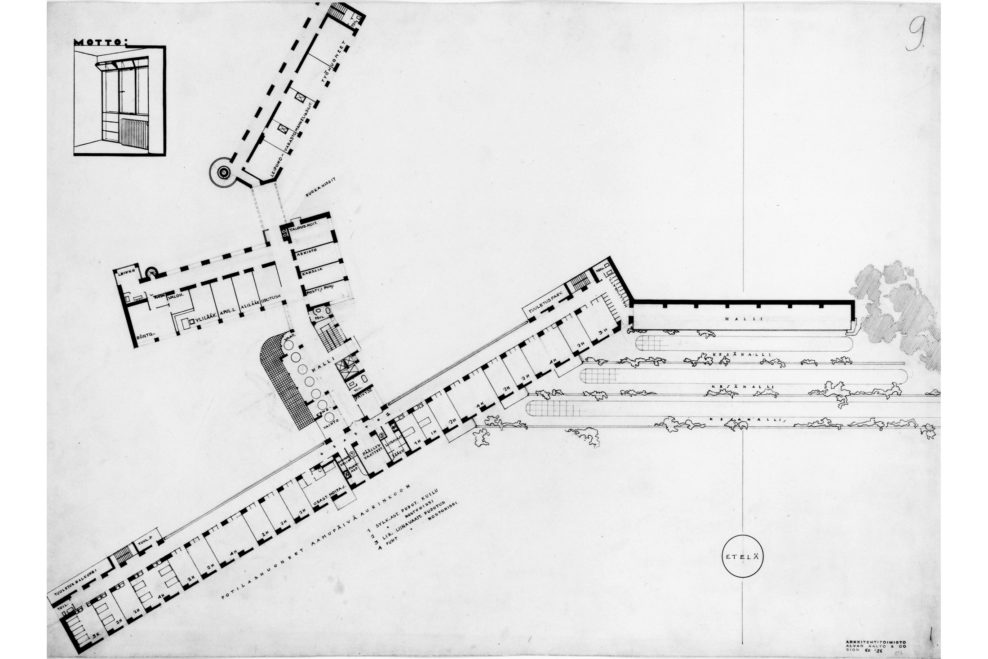

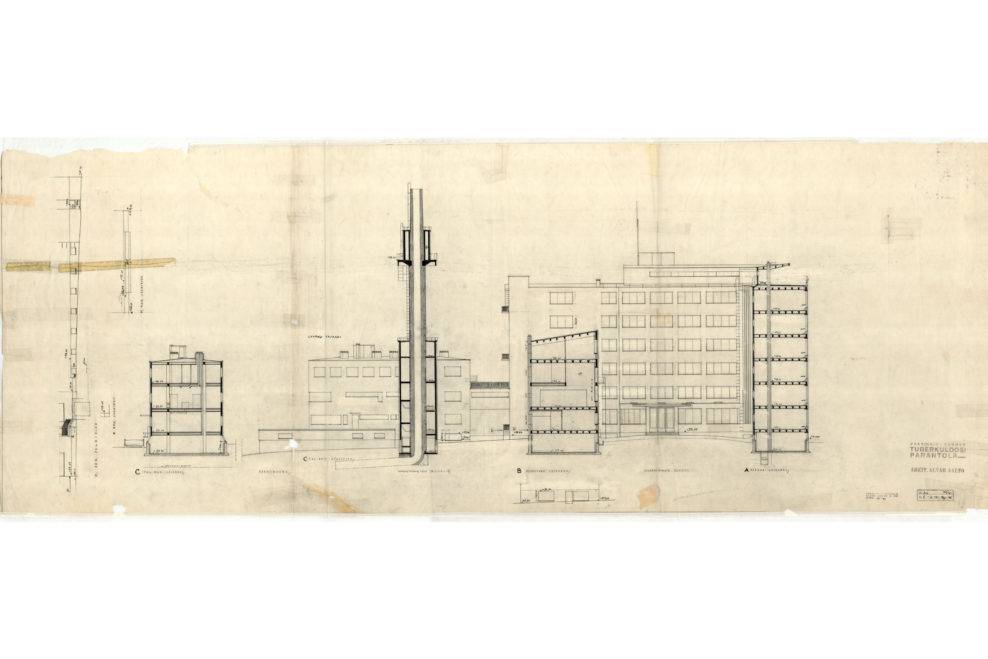

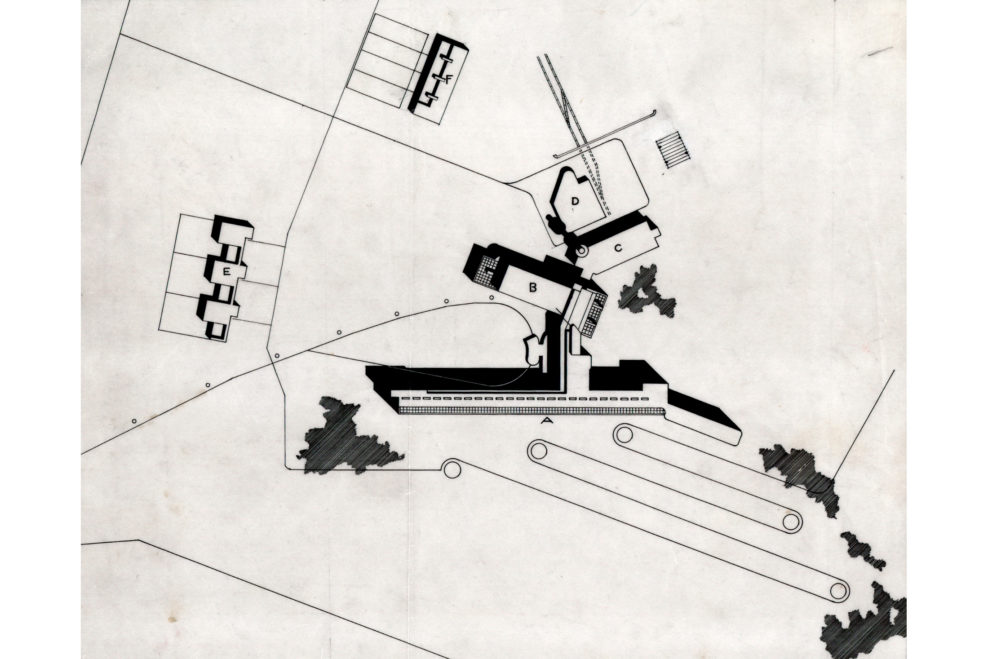

Site Plan, Paimio Sanatorium, 1932; Drawing: Alvar Aalto (Finnish, 1898–1976), Alvar Aalto Foundation

Photograph: Patients’ Room, 1933, Gustaf Welin, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Noiseless Wash Basin, 1932; Drawing: Alvar Aalto (Finnish, 1898–1976), Alvar Aalto Foundation

Paimio Lounge Chair (model 41), 1931–32 The Paimio Chair aimed to straighten the patient’s back to help them breathe and cough. The chair was made from curved plywood rather than from the tubular steel favored by many modern designers in the 1920s and 1930s. This iconic chair has furnished countless homes, offices, and lobbies. Alvar Aalto (Finnish, 1898–1976); Bent plywood, bent laminated birch, and solid birch; Manufacturer: Oy Huonekalu-ja Rakennustyötehdas Ab, Turku, Finland; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. Fund, 1943

Alvar Aalto (Finnish, 1898–1976); Bent plywood, bent laminated birch, and solid birch; Manufacturer: Oy Huonekalu-ja Rakennustyötehdas Ab, Turku, Finland; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. Fund, 1943

Paimio Chair and Aino Aalto, ca. 1932; Photograph: Alvar Aalto Foundation

Featured Image: Paimio Chair and Aino Aalto, ca. 1932; Photograph: Alvar Aalto Foundation

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Alvar Aalto Foundation | Alvar Aalto -säätiö EN Alvar Aalto Foundation | Alvar Aalto -säätiö EN

- Architecture

22. 4. M o n d a y

Guided tours.

for groups by appointment

The Aalto House

Studio Aalto

Exhibition: AALTO – AINO, ALVAR, ELISSA

Exhibition: new standards – puutalo oy 1940-1955, 23. 4. t u e s d a y.

12:00, 13:00 and 14:00

24. 4. W e d n e s d a y

25. 4. t h u r s d a y, 26. 4. f r i d a y, 27. 4. s a t u r d a y.

12:00 and 13:00

28. 4. S u n d a y

14:30 and 15:30

29. 4. M o n d a y

30. 4. t u e s d a y, 1. 5. w e d n e s d a y, 2. 5. t h u r s d a y, 3. 5. f r i d a y, 4. 5. s a t u r d a y, 5. 5. s u n d a y, 6. 5. m o n d a y, 7. 5. t u e s d a y, 8. 5. w e d n e s d a y, 9. 5. t h u r s d a y, 10. 5. f r i d a y, 11. 5. s a t u r d a y, 12. 5. s u n d a y, 13. 5. m o n d a y, 14. 5. t u e s d a y, 15. 5. w e d n e s d a y, 16. 5. t h u r s d a y, 17. 5. f r i d a y, 18. 5. s a t u r d a y, exhibition: the pool – the origin of pool skateboarding, 19. 5. s u n d a y, 20. 5. m o n d a y, 21. 5. t u e s d a y, 22. 5. w e d n e s d a y, 23. 5. t h u r s d a y, 24. 5. f r i d a y, 25. 5. s a t u r d a y, 26. 5. s u n d a y, 27. 5. m o n d a y, 28. 5. t u e s d a y, 29. 5. w e d n e s d a y, 30. 5. t h u r s d a y, 31. 5. f r i d a y, 1. 6. s a t u r d a y, 2. 6. s u n d a y, 3. 6. m o n d a y, 4. 6. t u e s d a y, 5. 6. w e d n e s d a y, 6. 6. t h u r s d a y, 7. 6. f r i d a y, 8. 6. s a t u r d a y, 9. 6. s u n d a y, 10. 6. m o n d a y, 11. 6. t u e s d a y, 12. 6. w e d n e s d a y, 13. 6. t h u r s d a y, 14. 6. f r i d a y, 15. 6. s a t u r d a y, 16. 6. s u n d a y, 17. 6. m o n d a y, 18. 6. t u e s d a y, 19. 6. w e d n e s d a y, 20. 6. t h u r s d a y, 21. 6. f r i d a y, 22. 6. s a t u r d a y, 23. 6. s u n d a y, 24. 6. m o n d a y, 25. 6. t u e s d a y, 26. 6. w e d n e s d a y, 27. 6. t h u r s d a y, 28. 6. f r i d a y, 29. 6. s a t u r d a y, 30. 6. s u n d a y, 1. 7. m o n d a y, 2. 7. t u e s d a y, 3. 7. w e d n e s d a y, 4. 7. t h u r s d a y, 5. 7. f r i d a y, 6. 7. s a t u r d a y, 7. 7. s u n d a y, 8. 7. m o n d a y, 9. 7. t u e s d a y, 10. 7. w e d n e s d a y, 11. 7. t h u r s d a y, 12. 7. f r i d a y, 13. 7. s a t u r d a y, 14. 7. s u n d a y, 15. 7. m o n d a y, 16. 7. t u e s d a y, 17. 7. w e d n e s d a y, 18. 7. t h u r s d a y, 19. 7. f r i d a y, 20. 7. s a t u r d a y, 21. 7. s u n d a y, 22. 7. m o n d a y, 23. 7. t u e s d a y, 24. 7. w e d n e s d a y, 25. 7. t h u r s d a y, 26. 7. f r i d a y, 27. 7. s a t u r d a y, 28. 7. s u n d a y, 29. 7. m o n d a y, 30. 7. t u e s d a y, 31. 7. w e d n e s d a y, 1. 8. t h u r s d a y, 2. 8. f r i d a y, 3. 8. s a t u r d a y, 4. 8. s u n d a y, 5. 8. m o n d a y, 6. 8. t u e s d a y, 7. 8. w e d n e s d a y, 8. 8. t h u r s d a y, 9. 8. f r i d a y, 10. 8. s a t u r d a y, 11. 8. s u n d a y, paimio sanatorium.

The building completed in 1933 as Paimio Sanatorium was of key importance to the international career of architects Alvar and Aino Aalto. Together with Vyborg (Viipuri) Library, completed two years later, it gave the Aaltos an international profile. Finnish architecture was no longer merely the receiver of influences from outside.

The building, constructed on the basis of their win in an architectural competition resolved in 1929, was groundbreaking. A tuberculosis sanatorium was particularly suitable for a building which followed the tenets of the new Functionalism, where bold concrete structures and state-of-the-art building services were inseparable elements of architecture and practicality.

Aalto designed the interior colour scheme, including the yellow floors in the main staircase, the colourful walls in the corridors, the dark ceilings in the patients’ rooms and the orange balcony rails, in conjunction with the decorative artist Eino Kauria.

The entire building complex, grouped together in several parts according to use, was constructed in accordance with Aalto’s philosophy, right down to the smallest details of the furniture. As far as the loose furniture was concerned, a good many items designed specifically for the sanatorium were used, as well as standard products which were already available. According to the idea of standardisation, which belonged to the spirit of the times, these items were also planned for use elsewhere – for example, many of the light fittings ended up in the catalogue of the Taito metalworks.

The pieces of furniture became key products for Artek, which was founded in 1935. The bent plywood Paimio chair in particular has become an international design icon. On the other hand, the three-legged stool , which is the same age as the sanatorium, was not included in the first phase of the furniture supplied by the Otto Korhonen furniture works. The furniture in the patients’ rooms was dominated by tubular-steel construction, soon to be spurned by the Aaltos.

An operating theatre wing designed by Aalto’s office was added to the main building in the late 1950s and new staff living-quarters were erected nearby in the 1960s. The sinuous, serpentine row of shared flats in the middle of the pine forest, known to the inmates as the ‘Hall of Vipers (Kyykartano), brought a new form of accommodation to the area.

Designed in

Finland, Paimio

Entrance. Photo: Maija Holma © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Plan of Paimio Sanatorium. Drawing © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Patient wing with sun terraces in 1930s. Photo: Gustaf Welin © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Patient wing with sun terraces altered to interior spaces. Photo: Maija Holma © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Plan of the patient wing. Drawing © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Section. Drawing © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Top floor sun terrace in 1933. Photo: Gustaf Welin © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Patiens in the top floor terrace in 1934. Photo: Gustaf Welin © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Room for patients in 1933. Photo: Gustaf Welin © Alvar Aalto Foundation

"A noiseless wash basin". Drawing © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Paimio chairs were used in the sanatorium. Photo: Gustaf Welin © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Sanatorium during summer. Photo: Maija Holma © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Site plan. Drawing © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Aerial photo of the sanatorium. Photo © Alvar Aalto Foundation

See opening hours from Paimio Sanatorium website www.paimiosanatorium.com.

Enquiries: info@paimiosanatorium.com, tel. +358 413184431 (Thu-Sun) or +358 413147680 (Mon-Wed)

Later alterations

With the advent of antibiotics, tuberculosis could be cured and ceased to be such a terrifying disease, so the sanatorium was gradually converted into a general hospital from the early 1960s onwards.

After Alvar Aalto’s death in 1976, his office, Alvar Aalto & Co, was in charge of alterations, under the leadership of architect Elissa Aalto from 1976 until 1994; since 1996, design work has been carried out by LPR Architects.

Over the years, the hospital buildings have been altered considerably, but the key characteristics of the architecture and much of the original furniture have been preserved. In recent years, hospital functions have been transferred elsewhere and a new use has been sought for the building.

For new needs to be in harmony with this unique architectural whole, the issues of the future use of the building and change management have to be resolved before the work, started by the National Board of Antiquities, on seeking UNESCO World Heritage status, can be resumed.

Photo: Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Museum

Publications

Alvar Aalto Architect volume 5: Paimio Sanatorium 1929-33 is a detailed book with images and drawings about the building and available on our shop.alvaraalto.fi .

Architecture by Alvar Aalto 1: Paimio sanatorium is a booklet presenting the sanatorium with images and drawings. Available on shop.alvaraalto.fi .

More information

Paimio sanatorium Alvar Aallon tie 275 FI-21540 Preitilä

Tel: +358 41 318 4431

Paimio Sanatorium Foundation website

Photo: Maija Holma © Alvar Aalto Foundation

Visit Paimio Sanatorium

See available tours at visit.alvaraalto.fi

Paimio Sanatorium Conservation Management Plan 2016

Paimio chair

Inquiry launched into Paimio Sanatorium’s future

Press release

New Foundation being set up to ensure the future of Paimio Sanatorium

The Paimio Appeal

- Use of cookies

- Necessary cookies

- 3rd Party Cookies

This website uses cookies. The cookie information is stored in the browser and the information is used to identify the user. On this page, you can change the way you allow or deny the use of cookies.

Necessary cookies are essential in order to use certain functions on the website.

If you disable the necessary cookies, certain functions on the website will not work. In addition, we will not be able to save your prohibition on the use of cookies and will have to ask again later.

The site uses Google Analytics, which we use to analyze visitor numbers and site usage. Google Analytics associates this information with its own user data in accordance with its own privacy policy.

By accepting third-party cookies, you allow access to this information.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

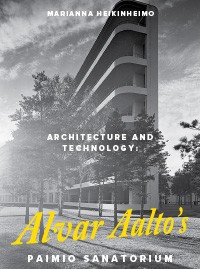

The Paimio Sanatorium (1928-1933) has been canonized as an internationally recognized masterpiece of modern architecture, and it is often considered to be the breakthrough of Alvar Aalto.

The theme of this web page is connected to my doctoral thesis Architecture and technology: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium for the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Architecture. I am Helsinki-based architect, researcher and entrepreneur. The list of references includes some of my research articles dealing with the Paimio sanatorium and other texts related to Aalto’s works, hospital architecture and research on the 20th century architecture. There are also links to my entrepreneurial activities. Ark-byroo architects has made approximately 300 building historical surveys, of which the first was about the Paimio sanatorium. Archtours, on its behalf, is an international network company arranging architectural study tours through its local networks. Helsinki September 8, 2014, updated July 4, 2018 Marianna Heikinheimo

Download thesis

related texts

image gallery

Paimio sanatorium, introduction.

In autumn 1928 the committee in charge of building Paimio Sanatorium (the Tuberculosis Sanatorium of Southwest Finland), issued the following announcement: “Esteemed Architects are invited to participate in a competition for drawing up the designs for said sanatorium with 184 sick beds”. [1] Alvar Aalto won the open competition and the construction project began soon after the result had been announced.

Architects Aino and Alvar Aalto, then a young couple, had developed very rapidly in their ideas about architecture, and it is difficult to imagine that the rather modest Alajärvi Municipal Hospital completed in 1928 was designed by the same practice as the winning entry for Paimio Sanatorium in the following year. When the Aaltos [2] moved to Turku in 1927, they came into contact with a group of important avant-garde architects. Turku and the international contacts it brought the Aaltos had a strong influence on their ideas about the home, living and architecture. Their moving to a new environment can also be seen as a spiritual journey into a world of new stimuli and architectonic ideas. [3]

The task of designing Paimio Sanatorium offered the innovative young architects the opportunity to try out their new ideas in practice. With its wings of different heights, its various gardens, courtyards and sections, Paimio Sanatorium resembled a small town. The steel ribbon windows of the facade and the mechanical motion of the scenic lift were features that underlined the overall feeling of movement. The Aaltos’ architecture, using reinforced concrete, met the requirements for hygiene, fresh air and sunlight generally placed on tuberculosis sanatoria. They saw the patients’ rooms as minimal apartments, and this inspired them to develop suitable furniture, both movable and fixed, for a small space. The simple design of articles for everyday use reflected the value placed by the architects on the morphology of industrially manufactured articles. In the course of the Paimio Sanatorium project, cooperation between Alvar Aalto and furniture manufacturer Otto Korhonen deepened, leading to the creation of an autonomous process for patenting the technical innovations relating to furniture. [4]

The common factor linking functionalist architecture and Taylorism (the Scientific Management method developed by Frederick Winslow Taylor, a reformer who introduced rational work methods) is the need to redefine problems and seek new solutions to them. These ideas are strongly reflected in the architecture of Paimio Sanatorium. In fact, in terms of its challenges, the design of the sanatorium can be compared to that of a factory.

In the industrial world of the early 20th century Taylorism can be seen as a process of profound cultural change that affected all spheres of life. The engineers who specialised in re-organising industrial production studied the functioning of a factory and analysed the work motions and the time taken to perform the work, the tools used, and the work environment. The work itself was divided into stages, and for each stage an optimal way of performing the work was defined. The traditional ways of working were to be subjected to rational scrutiny.

With the demands for standardisation and efficient use of manpower, materials and workshops, there arose a need to re-design the factory. The design of an industrial plant required knowledge of production economy, rational plant design, new technical systems for buildings, and installation technology – in practice, therefore, a profound and broad-based expertise. [5]

Architects became familiar with Taylorism mainly through the works and writings of Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier. The demands of rationalism were part of the theoretical groundwork for functionalism. [6] The architects were also interested in Frank B. Gilbreth’s visual motion studies, which aimed to define work methods that were both efficient and energy-saving and to develop appropriate tools for the work. The Aaltos also had to consider similar details when designing Paimio Sanatorium.

The sanatorium as an institution

The planning of a tuberculosis sanatorium was a matter of national importance and urgency in Finland. In the early decades of the 20 th century there was no medication for pulmonary tuberculosis, which posed a serious threat to public health. The disease was treated in specialised institutions through rest, diet, exercise and surgery. [7] Patients were taught ways of making their everyday lives easier and protecting themselves and those living with them from infection. Treatment times were long and not very effective. With the Act on State Aid which came into force in 1930, society took over financial responsibility for the building and maintenance of institutions for the treatment of tuberculosis. The State began to subsidise public sanatorium projects by paying 75 per cent of the building costs, in addition to supporting their operation. The National Board of Health supervised the projects receiving financial support. In the first half of the 1930s, 16 large new public sanatoria were built in Finland. [8]

Paimio Sanatorium was commissioned by a special Building Committee set up for the building of a tuberculosis sanatorium by the Municipal Federation of Southwest Finland, consisting of 52 municipalities. The committee consisted of lay members, three of them being Members of Parliament, who were able to follow the progress of the Act on State Aid in Parliament. [9] The construction project was timed so that it was eligible to apply for financial aid. The work started in late spring 1930 and the sanatorium was inaugurated on June 18, 1933.

In addition to the main sanatorium building, the Aaltos’ architectural practice designed other buildings that were completed at the same time. There were also older buildings, most of them farm buildings, on the 327 hectare estate set up for the sanatorium. Paimio Sanatorium was built to take 286 patients. A total of about 70 people worked on the farm and at the hospital. All the daily foodstuffs for both patients and staff were provided by the farm.

Tuberculosis was a much feared disease in the 1930s, and Paimio Sanatorium was an institution where the patients were isolated. Its tall, white, 7-storey high outline was unlike anything that had been seen before in the Finnish countryside. Despite people’s fear of the disease the project was publicised from the beginning in a positive light, as there was seen to be a real need for a modern tuberculosis hospital. The positive public image was influenced particularly by the recently enforced Act on State Aid, but probably Alvar Aalto’s effective and extensive public relations efforts also played a role in building the sanatorium’s image. He knew many influential people and through his contacts was able to gain publicity not only for his own design work, but also for the whole project.

Since its completion Paimio Sanatorium has been in use as a hospital, and it has therefore not been possible to completely avoid alterations. Protection of the building was first considered when Alvar Aalto died in 1976. Aalto was such a highly regarded authority in Finland that the quality of the changes made was not discussed in front of the maestro during his lifetime. The National Board of Antiquities started the protection process with the Building Protection Act in 1990, as protection on the level of regional and local master plans was not sufficient to ensure that the cultural-historical values of the area would be preserved. In 1993 Paimio Sanatorium was protected under the Building Protection Act. The protected buildings are the former sanatorium, the heating plant, the garage facilities, the workers’ housing, the junior doctors’ terraced houses, the senior physician’s residence, the funeral chapel and the area surrounding these buildings. In 2002 the Ministry of Education applied for nomination of Paimio Sanatorium to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Sanatorium architecture

Competition.

Although the Building Committee’s original intention was to organise a large invited competition for the design of the institutional building, in which the architects invited to participate would be experienced hospital designers, an open competition was organised. This was of vital importance for new architects who were just setting out on their career. The jury for the competition consisted of the chairman of the Building Committee, Bernhard Heikkilä, with architects Jussi Paatela and Väinö Vähäkallio from the Finnish Association of Architects, Professor Akseli Koskimies of the Association for the Control of Tuberculosis (now the Finnish Lung Health Association), and Doctors Severi Savonen and Väinö Horelli. Väinö Vähäkallio was familiar with the development of construction technology and the demands of rationalisation [10] , while Jussi Paatela was a specialist in hospital design. [11] He also served as an expert for the National Board of Health’s hospital department during the building of Paimio Sanatorium. Doctors Severi Savonen and Väinö Horelli acted both as representatives of the developer responsible for the building project and as experts for the National Board of Health.

The programme for the architectural competition listed the buildings to be designed, the space requirements for the functions to be located in the main building and instructions for the allocation of space. [12] Four separate wards were planned, with a total of 184 beds. The individual rooms were designed to accommodate two, three or four patients, with 25 cubic metres of space for each patient. Each ward would also have two single rooms. The sanatorium would have offices and examination rooms, rooms in each ward for the use of staff and of patients, and communal rooms for the use of all patients. In addition, kitchens, rooms for the use of nursing and domestic staff, communal spaces and equipment, an isolation ward with its own entrance for patients with contagious diseases were also to be located in the main building. Further, the competition programme specified as separate buildings a residence for the senior physician, housing for the junior physicians and housekeeper, a maintenance building and a building for housing staff. The farm buildings were not included in the competition brief.

The competition entries were placed in three classes by the jury: one entry in the lowest class, eight in the middle class and four in the top class. Of the latter, three were awarded prizes. The jury was unanimous as regards the winning entry, submitted under the pseudonym Piirretty ikkuna (Drawn Window) . The second prize was awarded to a team of three architects, Kaarlo Borg, Otto Flodin and Paavo Hanstén for their entry, Valo (Light) . The third prize went to Antero Pernaja and Ragnar Ypyä for their entry, Ammon-Ra . The Awards Committee proposed purchasing Erik Bryggmann’s entry, also placed in the top class, for its architectural merit, but the Building Committee rejected the proposal.

The jury considered Alvar Aalto’s Drawn Window architectonically interesting, but somewhat “restless and pretentious” as a whole. The room arrangement was considered pleasing and their layout successful. However, the dimensioning of the building was criticised: the main stairway was too narrow, the patients’ bathing facilities overestimated and the cubic volume of the building insufficient. The jury favoured economy in the basic solutions, and felt that a wider frame would reduce the external wall surface and thus the heating costs. [13]

The entries gaining second and third place, Valo and Ammon-Ra, were similar in their basic concepts. The buildings had L-shaped floor plans within a orthogonal coordinate system, with the wards leading off side corridors, located on different storeys in one wing, and an open sun deck wing continuing from it. The entrances were at the articulation point of the L-shaped building. Both entries had a large roof terrace. The jury criticised the placing of individual functions in the building and the dimensioning of the spaces. Also criticised was the use of strip windows on the façade of the Ammon-Ra entry, despite the fact that it was a load-bearing structure. All the prize-winning entries had flat roofs. [14]

The winning entry, consisting of eleven sets of drawings, met the competition requirements as far as the buildings were concerned. The three wings of the main building were laid out on a free-form coordinate system. Two of the wings were four storeys high and one had three storeys. In the main building all the wings had side corridors. Different types of activities were distributed among the different wings. In the competition entry the wards’ sun balconies were a continuation of the patient wing, but the idea of a roof terrace was only introduced as a proposal. Three sun decks for use in summer were to be built on the terraced slope in front of the sun balcony wing. The heating plant and garage space were in the basement of the maintenance wing.

The four wards located on different floors were identical. The isolation ward was situated below them in the basement. Although the patients’ rooms were intended to accommodate 1–4 patients, most of them had two occupants. The ward sister’s accommodation, with a south-facing balcony, was midway along the row of patients’ rooms.

In the B wing above the second-floor reading room and library were living quarters with spacious loggias. The dining room and a common room, the hub of social life in the sanatorium, were also located in B wing. The canopy over the entrance was rounded at one end, but otherwise rectangular. Aalto’s proposal visualised a water tank to be built around the heating plant chimney, accessed by a glass-walled spiral staircase. [15]

The load-bearing column and slab construction was already fully worked out at the competition stage. The lines of columns in the patient wing were behind the south-facing facade, inside the corridor walls. The vertical pipe risers were also to be inside the corridor walls, as finally implemented. The projecting sun balconies were closed at one side and open at the other. The load-bearing beams were designed to taper towards the outer edge.

In the competition entry, the main building was to have a flat roof and roof terraces. According to the report, a wooden roof truss and a sharply-pitched tiled roof was too complex a solution for the basic structure of the main building, but might be acceptable in a smaller building. Aalto’s tactics were evidently to keep options for the roof open, fearing that the jury would favour more traditional roof shapes.

At the competition stage, the junior physicians’ terraced building was to be built in the same direction as the B wing, with its long side parallel to the entrance axis. The long facade of the staff building was also to face south. The morgue was to be north of the maintenance wing near the main building. The senior physician’s house was to be situated farther from the main building.

While the competition was still in progress, Alvar Aalto received a letter from the National Board of Health dated January 2, 1929, expressing an opinion on the draft design for the Tuberculosis Sanatorium of Southwest Finland, in other words the as yet unfinished competition entry. [16] The letter, which is still in the Aalto archives, bears the name “Horelli” pencilled in, in brackets. This suggests that Aalto knew about Väinö Horelli’s statement, and therefore at the competition phase he already knew the medical expert’s opinion on certain critical issues. As the criticism of Aalto’s entry received at the beginning of January differs in content from the assessment of his final competition entry, it can be surmised that his plan developed considerably during January 1929. [17] It remains a mystery to what extent the medical expert’s opinion finally influenced Aalto’s work and the course of events during the competition: Did Aalto gain an advantage over the other competitors, or did the situation put him I an awkward position?

The design commission

The architect’s assignment included the main drawings, cost calculations and specification of works, supervision of the construction work and interior design, excluding the houses and apartments meant for private use. The developer was responsible for contracting out the work. Aalto as leading expert was able to influence the choice of contractors and subcontractors.

In addition to Alvar Aalto and Aino Marsio-Aalto, the Norwegians Erling Bjertnäs and Harald Wildhagen, as well as Finnish architects Lauri Sipilä and Lars Wiklund, participated in the design. [18] Concrete engineer Emil Henriksson’s engineering office carried out the strength calculations for the reinforced concrete structures of the main building as a sub-consultant for the architectural practice. [19] Various engineering offices and subcontractors drew up the specialised technical plans, mainly at the implementation phase. The planning and building were started in 1929. The design process went on until 1932, and the project was completed in 1933. Detail design and construction went on simultaneously.

In his work the architect had to consider the changes to the competition entry proposed by the experts. The main drawings and cost calculations were supposed to be ready by December 1, 1929. The design contract was extremely stringent. For example, as a condition for accepting the drawings or for the granting of State aid, it included a clause whereby the architect was obliged, without separate remuneration, to draw up new drawings should the National Board of Health propose changes. [20]

Aalto presented the final drawings to the Building Committee according to schedule, in December 1929. The committee was satisfied and stated that Aalto had in the main taken the required changes into consideration. [21] The scale of the Paimio Sanatorium project changed significantly the following spring, when the City of Turku decided to participate. As a result, the number of patient beds was increased from 184 to 286, but the wish expressed by the City of Turku that the number of staff be increased accordingly was turned down. The medical experts considered the planned number of staff to be sufficient, despite the greater number of patients. [22] The change in the building plan meant adding two extra floors to the patients’ wing. Aalto presented the drawings for the extended sanatorium to the Building Committee in April 1930, after which he had the task of sending an application for approval of the drawings by the National Board of Health. [23]

Division of functions

The floor plan for Paimio Sanatorium attracted attention as it was asymmetrical and non-rectilinear, but at the same time was based on a controlled system of coordinates. The sun balconies joined the A wing at an angle of 20˚, running parallel to the B wing; in other words the A and B wings were at an angle of 20˚ to each other. This can be seen from the entrance forecourt as a false perspective. The circulation area connecting the A and B wings was at right angles in relation to the A wing, while the C wing joined the B wing at an angle of 45˚.

Different functions were placed in different wings, which was the standard practice in tuberculosis sanatoria. [24] Aalto was also familiar with the grouping and separation of functions indirectly, through the concept of rationalisation as proposed in the Scientific Management programme. Special requirements regarding light and sunshine only affected spaces where it was important for treatment and it was necessary to ensure that light could penetrate sufficiently into the building frame. The sun balconies the large halls, the dining room and the work room in the B wing faced directly south. The halls were higher on the south than on the north side. This ensured that the sunlight could penetrate into the northern corners of the space as exemplified in the sectional drawing. The windows of the patients’ pavilion faced south-southeast towards the morning sun. To regulate the light entering the patients’ rooms, wooden Venetian blinds were fixed outside the windows. The windows on the south-facing B wing facade were furnished with canvas sun awnings. Aalto accepted the medical experts’ opinion that patients needed shade as well as sunlight. [25] The operating theatre was separated from the four-storey volume of the building in a low, semi-circular structure on the northern side of the B wing. The theatre received natural light from above and from the side, thus meeting the orthodox requirements for its function. [26]

The patients’ rooms formed a row along the almost 100-metre long corridor. [27] At the western end of the corridor, outside the actual ward area, were the apartments for the ward sisters. These six small apartments had their own lift and stairs. At the eastern end of the patients’ wing each ward’s sun balconies formed their own separate units adjoining the patient wing. On the sixth floor there was a sun deck for 120 patients meant for the use of all wards.

The ward’s work rooms were strategically placed near the middle of the corridor, so that traffic along the corridor was easily supervised. The office was separated from the corridor by glass walls.

The six wards, one above the other, were almost identical, but separate units. According to Taylorism, problems would be solved in separate production units without disturbing the functions of the whole plant. In Paimio Sanatorium men and women were in separate wards, [28] the weaker patients on the lower floors.

The building was entered from a foyer connecting the A and B wings. This route was used by the patients and some of the staff. The main entry was covered with a free-form canopy, which was an eye-catching feature of the inner courtyard. The front steps were partly outside and partly inside the building with the door on the intermediate landing. For carrying stretchers into the building the staircase was impractical but evidently this was not regarded as a disadvantage as the patients selected for the sanatorium were fit enough for rehabilitation and reasonably mobile. [29]

The work stations of the administrative and nursing staff were all near the main foyer. The administrative department also had its own entry. The communal spaces for the use of patients were on the upper floors of B wing, as were also the staff common rooms and living quarters. B wing was the most versatile part of the building in terms of functions. Local people from Paimio also visited the sanatorium to consult doctors as the municipal GP’s post had been discontinued when the sanatorium was built, and junior physicians could also take private patients. [30]

The junior physicians and ward sisters regularly had meals with the patients in the large dining room, which was designed to be multi-functional. From a room on the second floor films could be projected onto the wall of the dining room, and as the chairs and tables were stackable, the room could be also cleared for social functions. In addition, the white leather-covered sliding door of the dining room could be opened directly onto the patients’ communal lounge. As the wards had none of the dayrooms typical in sanatoria, the lounge was no doubt actively used.

The maintenance building and the B wing were joined by a tunnel-like corridor where the food was also served into dishes stored in practical wheeled cupboards. In the kitchens, the areas where food was cooked were separated by glass partitions. The ingredients were prepared on the floor below. The basement in C wing housed a laundry and on the upper floors the living quarters for kitchen staff.

The staff and their families lived on the premises of the Paimio Sanatorium, and different forms of housing were an important feature of the entire sanatorium area. In practice it was expected that the doctors and female nursing staff would live on the grounds of the sanatorium. Likewise it was recommended that the female domestic staff and male technical staff should live near the sanatorium. This made staff supervision easier, and they would also be more committed to the work if they were offered housing. [31]

In the 1920s–1930s a detached house was usually built for the senior physician in the hospital grounds. For junior physicians a terraced house with 3-4 rooms and a kitchen was considered suitable. Housing for female nursing staff was also given attention as they often lived on the hospital premises for most of their working lives. [32]

The size and comfort of the dwellings reflected the social hierarchy within the community. The senior physician of Paimio Sanatorium lived in a two-storey detached villa-type house with a floor area of 250 square metres and surrounded by a garden, situated 150 metres from the main building. The family had three bedrooms at their disposal as well as a large reception room, two toilets, a bathroom and a dressing room. The kitchen was equipped with a refrigerator. There was a servant’s room and toilet with a separate entrance. The senior physician’s house even had separate plumbing, so that his family would not be affected by any bacteria spread by water. The house also had its own sauna in the garden. Of the sanatorium staff, the head physician was the only one who had a say in the planning of his own living quarters. [33]

The terraced house for the junior physicians’ and the housekeepers’ families was a partly two-storey and partly single-storey, chain-like building that bordered on the sanatorium’s entrance forecourt. The area of the houses was 120 square metres per dwelling and each had three bedrooms, a toilet and a bathroom. There was a room and toilet for a servant adjoining the kitchen. Doctors and the housekeeper were assumed to have families, and the housing was thus designed accordingly.

There were two types of accommodation for workers. On the ground floor of the building there were four family apartments of 45 square metres with a living room, two bedrooms, a kitchenette and a toilet. On the upper floor there were 8 single-room apartments of 16 square metres each, furnished with a wash basin only. The rooms were built along an open gallery, at the end of which there were two toilets for residents’ use. The upper storey apartments were probably for male workers with no families, such as drivers and heating plant workers. [34]

The size and furnishing of the housing were more modest the further down the occupant was in the sanatorium hierarchy. The lowest level was the quarters for female staff on the second floor of the C wing in the main building. Aalto compared the living quarters to a hotel, and in the drawings this part was called the “service and kitchen staff hotel”. The designation hotel is controversial, as generally a hotel implies temporary habitation. On the other hand, the name can be seen as an attempt to make the modest form of housing seem more luxurious, and give the impression of efficiency. Even a small hotel room usually has toilet and washing facilities, in the same way as a ship’s cabin. Both a hotel room and a ship’s cabin can be compared to the minimum apartment which had probably inspired the architect.

Indoor and outdoor space

The relationship between indoor and outdoor spaces plays an important role at Paimio Sanatorium, as in most of Aalto’s architecture. Between the wings of the main building a number of different courtyards and gardens were built, forming a part of the functional complex.

The entrance courtyard opening to the west of the sanatorium, bordered on three sides by the main building, and on the western side by the junior physicians’ terraced houses. The road curving in front of the main door was dimensioned to allow a vehicle to turn. People were brought by bus from Paimio station right to the sanatorium door. In the centre of the courtyard there was a parking area decorated with flowers. From the stair landings, the patients’ corridors, the dining room and the library there was a good view of this central stage. A Swedish manual of hospital building from the 1930s urged that the main entrance be separated from the outpatient and staff entrances. The entrances should also be located so that traffic would not disturb infirm patients. [35] Aalto’s plan was completely different: In his view it was important to see and to be seen. From the patients’ corridor you could see the main entrance, which was also the route used by patients going to the outpatient department. Aalto’s sanatorium entrance was like the steps up to a 19th century theatre: a social stage.

In the garden to the south of the patients’ wing five circular ponds were built, bordered by flower beds and joined by sandy paths. The bright, sheltered garden, freely bordering on the forest, was meant for the patients to walk in. From their rooms and sun balconies patients could watch life in the courtyards and gardens, and by walking outside they could express their existence, for example, they communicate their improved state of health, to others.

The entrance forecourt and garden were visible to all, but one could also see from outside into the sanatorium. The open building with its large window panes gave those outside an insight into life inside the sanatorium. [36] At night and in winter the patients’ corridors with their strong colours and bright lighting made the sanatorium glow like a lamp in the dark.

Mechanical motion

Paimio Sanatorium was in many ways an extremely modern hospital building. The multi-storey hospital was based on the idea of greater efficiency and shorter distances. Movement between floors was by staircases, lifts and shafts.

Three passenger lifts, two combined passenger and goods lifts and one lift for conveying sputum spittoons, were installed in the sanatorium. [37] The patients’ soiled linen was dropped from a shaft in the ward to the basement, where the laundry was situated. The clean washing was taken by lift back to the ward.

Efficient lifts played an important role in the new rationalist and functionalist architecture. In 1914, in his manifesto on futuristic architecture, the architect Antonio Sant’Elia extolled buildings that were like machines and encouraged his colleagues to place lifts where they could be seen, on the facades of buildings, like “serpents of steel and glass”:

“ We must invent and rebuild the Futurist city like an immense and tumultuous shipyard, agile, mobile and dynamic in every detail; and the Futurist house must be like a gigantic machine. The lifts must no longer be hidden away like tapeworms in the niches of stairwells; the stairwells themselves, rendered useless, must be abolished, and the lifts must scale the lengths of the façades like serpents of steel and glass .” [38]

The scenic lift at Paimio Sanatorium can be seen as a romantic idealisation of the building as a machine. The lift was housed between two glazed steel-framed walls. The movement of the plywood lift car and the mechanism with its wheels were visible through the glass as one approached the sanatorium. The high, narrow glazed shaft in the facade accentuated the scale of the building, and gave expression to a longing for the hectic bustle of metropolitan life, which never stopped, even at night.

Fresh air and abundant natural light were two of the central themes in rationalist building and architecture. Alvar Aalto gave considerable thought to ventilation and air, in many different contexts:

“Among the biological requirements of human life are air, light and sun. Air cannot be equated to room size or number of rooms. It is a factor in its own right. We can certainly build a dwelling with a large volume of air without it affecting the economical use of floor area or playing any role in determining room heights. It is a question of ventilation.” [39]

A natural gravity ventilation system was installed in Paimio Sanatorium., The importance of clean air and ventilation for health was emphasised in the early decades of the 20 th century, especially in medical publications. As the patients’ wing was ventilated all year round, the indoor spaces of the building were not as warm in winter as they were designed to be. There was an exhaust outlet in the corridor-side wall of the patients’ rooms. These were equipped with valves and the exhaust air was conveyed by separate shafts to the roof ridge. [40] The height of the building resulted in an air pressure difference between the lower and upper floors, which allowed the gravity system to operate efficiently. On the roof there were separate ventilation outlets for each group of shafts. In rooms where gases accumulated the exhaust air outlets were provided with electrically operated valves.

The combination of central heating and gravity ventilation is highly dependent on season and wind conditions. It is more efficient the greater the difference between indoor and outside temperatures, and thus the system works best in winter. [41]

Standardisation

Standardisation was one of the pillars of Taylor’s Scientific Management method:

“The standard method of doing anything is simply the best method that can be devised at the time the standard is drawn. Improvements in standards are wanted whenever and wherever they are found (…) a proposed change in a standard must be scrutinized as carefully as the standard was scrutinized prior to its adoption; and further that this work be done by experts as competent to do it as were those who originally framed the standard (…) Standardization practised in this way is a constant invitation to experimentation and improvement.” [42]

The idea of standardisation was so important to Aalto that he had included the requirement for standard drawings in the design contract for Paimio Sanatorium. [43] He had evidently taken the idea of human biological needs as standard requirements from Le Corbusier. In the years 1929–32 Aalto designed a number of objects that he designated as “standard”, most of them connected with the Paimio Sanatorium project. [44] For example, the furnishing of the patients’ rooms inspired the architect to design standards for the wardrobe, glass shelf, wash basin, spittoons and windows.

According to the view of the Finnish Standardisation Board, the standardisation of the house building sector could be divided into standardisation of parts of buildings and of complete buildings. The standardisation of building parts was further classified as standardisation of form and dimensions, or of quality. [45] Aalto’s interest in the subject also concerned the use of materials in the Paimio Sanatorium building parts. Functionalist architects considered reinforced concrete to be a material that was modern, of uniform quality and scientifically developed.

Reinforced concrete

The structural concept chosen for the main building of Paimio Sanatorium was based on Le Corbusier’s flexible system. The load-bearing frame of the main building consisted of reinforced concrete columns with a slab resting on top. The rows of load-bearing columns were partly inside the building envelope and at some places in line with the external wall. Where the slab extends out from the building in the form of a cantilever, the walls above and below the windows form narrow concrete beams directly connected to the floor slab.

The intermediate floor slabs consisted of two leaves. The upper leaf was cast onto a bed of coke cinder filling on top of the lower slab. The partition walls were built on the beam and separated from the load-bearing structure, thus creating a floor and partition wall system that was sound-insulating. Part of the beam system served to carry air exhaust ducts, and at these points the walls were made of concrete slabs. [46] The roofs of the main building were flat, and the double-slab attic floor served as the roof. Unlike the other spaces, the open sun decks and balconies were made of one slab. In this case the load-bearing structure was a beam carrying a slab or simply a cantilevered slab.

In the patients’ wing, the room division, load-bearing structure and ductwork conceived by Aalto work together in unison. The inspection hatches of the vertical pipe shaft in the corridor wall opened onto the corridor. This arrangement later restricted changes to the sanatorium’s plumbing, as the shafts were not big enough to accommodate both sewage and grey water pipes.

The sun balcony section owes its robust construction to Emil Henriksson, a specialist in concrete engineering, commissioned in 1930 by the Aaltos’ practice to carry out the concrete strength calculations. [47] The load-bearing row of columns in the completed building gives balance to the structure, which is cantilevered in two directions. The beams taper towards the outer edge of the cantilever. A thin reinforced concrete envelope cast in-situ was used in the solid, seven-storey high rear wall to protect the tensioned steel rods. The sophisticated structure was a unique example of engineering skill that satisfied the architect’s need to find a means of expression suited to the challenges of the task.

The concrete structure of the main building was built by the company owned by a Turku contractor, Master Builder Arvi Ahti, in 1930. [48] According to the contract, the architect’s drawings and building specifications took precedence over the construction drawings and strength calculations. The structures shown in the architectural drawings were not to be altered. The strength calculations and the casting work proceeded simultaneously. The concrete casting of the framework began with the boiler room in June. The concrete wall of the sun balcony section had reached plinth height by the end of July. [49] The concrete frames of the main building’s various wings were built between July and October. The strength calculations for the topmost beams of the B wing, which carried the intermediate floor between the dining room and the library, were not drawn up until November. The major part of the work was carried out in cold, rainy weather in the autumn of 1930. The final inspection of the structural framework was attended by both Aalto and Ahti, in a very positive atmosphere. According to the minutes, the contracted work had been executed with care and was of high quality, to the complete satisfaction of the client. Against expectations, the developer had been forced to commission drilling work on the bedrock at the site, and as a result had been forced to postpone contracting work to a less favourable time of year than planned. The contractor expressed special thanks that the detailed drawings and reinforced concrete calculations had always been delivered on schedule, and that all the work phases had been agreed on in good time. [50]

The construction of the sun balcony wing posed unprecedented challenges, and its execution depended on mutual trust and collaboration between two men. Ahti was Emil Henriksson’s brother-in-law and a member of the board of Ahti’s company. Henriksson was also Aalto’s oldest partner in cooperation. His collaboration with Alvar Aalto started with the projects for the South-western Finland Agricultural Cooperative Building and the local newspaper Turun Sanomat’s building in Turku. Aalto presented the tenders to the Building Committee in such a way that Ahti’s tender was accepted, even though it was not the cheapest. The Building Committee had already authorised the executive committee to sign the contract with another company. [51] In June after Ahti had submitted his tender the Building Committee and Aalto again negotiated with Ahti, who then lowered his price. This move did not, however, convince the executive committee, who considered that the new proposal required no further action, and they continued to negotiate with the company that had been chosen first. At this stage Aalto evidently found an omission in the tender, which he used to his own advantage. The chosen contractor had not included in the calculations the concrete casting work on the rear wall of the sun balconies as specified in Aalto’s final drawings. As no unanimous agreement could be reached the Building Committee called a halt to the contract negotiations and decided to approach Ahti, who reduced his tender to the same price as the first company had offered and was given the job. [52]

Even though the case took on somewhat farcical dimensions, it says something about Aalto’s ability to handle situations to his own advantage. Aalto, Ahti and Henriksson benefited from the mutual support, and Aalto was able to implement his bold plans with the help of trusted partners.

The Stockholm Exhibition of 1930

Sven Markelius was Aalto’s Swedish colleague and friend, who opened the doors to Europe for him. Markelius had been given the task of planning the hospital section of the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition. His expert team consisted of doctors and an engineer whose special field was heating, ventilation and sanitation. [53] The timing of the Stockholm Exhibition was perfect as regards the planning of Paimio Sanatorium. During the exhibition, in summer 1930, the master drawings for the sanatorium had just been completed and the design process was progressing to detailed drawings. The hospital section provided Aalto with a concrete model on which to base his design of the patients’ rooms in Paimio Sanatorium.

The purpose of the Stockholm Exhibition’s hospital section was to try out bold new solutions instead of the traditional ones, and to give manufacturers the opportunity to present their furniture and equipment designed for hospital use. The exhibition featured an operating theatre and a nursing ward. The ward was located on the top floor of the two-storey exhibition building. Intended to indicate future trends, the ward was of the “terrace hospital” type where the sun balcony was built in front of the patient’s room. Markelius pointed out that this concept was specifically suited for low buildings. The nursing ward comprised the patients’ dayroom, a kitchenette, two patients’ rooms with a bathroom between them, all built along a corridor. Markelius himself stressed that locating the toilet and washroom facilities on the sunny side of the building could be considered wasteful use of space, an unnecessary luxury, as their function did not require sunlight. Usually hospital wards had a bathroom. According to Markelius this solution made the staff’s work easier, improved hygiene and contributed to the patients’ comfort and wellbeing. A hospital should be comfortable in his view. [54]