Victoria's Visit

For a British monarch, Queen Victoria was extremely quick off the mark in making her first visit to Scotland in 1842, only five years after taking the throne. She was greatly excited by Sir Walter Scott's novels and very anxious to make the acquaintance of her northern kingdom, which soon became one of her favourite haunts after the purchase of Balmoral Castle a few years later. The citizens of Edinburgh duly turned out to greet her.

Thursday, September 1 1842 At a quarter to one o'clock, we heard the anchor let down - a welcome sound. At seven we went on deck, where we breakfasted. Close on one side were Leith and the high hills towering over Edinburgh, which was in fog; and on the other side was to be seen the Isle of May (where it is said Macduff held out against Macbeth), the Bass Rock being behind us. At ten minutes past eight we arrived at Granton Pier, where we were met by the Duke of Buccleuch, Sir Robert Peel and others. They came on board to see us, and Sir Robert told us that the people were all in the highest good humour, though naturally a little disappointed at having waited for us yesterday. We then stepped over a gangway on to the pier, the people cheering and the Duke saying that he begged to be allowed to welcome us. Our ladies and gentlemen had landed before us, safe and well, and we two got into a barouche, the ladies and gentlemen following. The Duke, the equerries, and Mr. Anson rode.

There were, however, not nearly so many people in Edinburgh, though the crowd and crush were such that one was really continually in fear of accidents. More regularity and order would have been preserved had there not been some mistake on the part of the Provost about giving due notice of our approach. The impression Edinburgh has made upon us is very great; it is quite beautiful, totally unlike anything else I have seen; and what is even more, Albert, who has seen so much, says it is unlike anything he ever saw; it is so regular, everything built of massive stone, there is not a brick to be seen anywhere. The High Street, which is pretty steep, is very fine. Then the Castle, situated on that grand rock in the middle of the town, is most striking. On the other side the Calton Hill, with the National Monument, a building in the Grecian style; Nelson's Monument; Burns' Monument; the Gaol, the National School, &c.; all magnificent buildings, and with Arthur's Seat in the background, overtopping the whole, form altogether a splendid spectacle. The enthusiasm was very great, and the people very friendly and kind. The Royal Archers Body Guard met us and walked with us the whole way through the town. It is composed entirely of noblemen and gentlemen, and they all walked close by the carriage; but were dreadfully pushed about.

Saturday 3rd September. The view of Edinburgh from the road before you enter Leith is quite enchanting; it is, as Albert said, 'fairy-like', and what you would only imagine as a thing to dream of, or to see in a picture. There was that beautiful large town, all of stone (no mingled colours of brick to mar it), with the bold Castle on one side, and the Calton Hill on the other, with those high sharp hills of Arthur's Seat and Salisbury Crags towering above all, and making the finest, boldest background imaginable. Albert said he felt sure the Acropolis could not be finer; and I hear they sometimes call Edinburgh 'the modern Athens'. The Archers Guard met us again at Leith, which is not a pretty town.

The people were most enthusiastic, and the crowd very great. The Porters all mounted, with curious Scotch caps, and their horses decorated with flowers, had a very singular effect; but the fishwomen are the most striking-looking people, and are generally young and pretty women - very clean and very Dutch-looking, with their white caps and bright-coloured petticoats. They never marry out of their class.

At six we returned well tired.

Victoria, Leaves from the Journal of our Lives in the Highlands, 1848-61 , Edinburgh, 1868.

SUPPORT OUR JOURNALISM: Please consider donating to keep our website running and free for all - thank you!

- Meet the team

- Privacy Policy

- Royal Weddings

- Media & Commentary requests

Queen Victoria and the Palace of Holyroodhouse

Queen Victoria’s love of Scotland and the Scottish Highlands is of course, legendary – immortalised in a wealth of artworks, souvenir albums, including the Queen’s own watercolours and not least of course, the Queen’s Highland journals. She praised Scotland with both her paintbrush and her pen. Queen Victoria was entirely devoted to the romance of the country, as seen through the poetic eyes of Sir Walter Scott, whose work the Queen deeply admired and whose Peveril of the Peak she read aloud to the Prince Consort as he lay dying at Windsor. Something of Scotland was with her right up until the end of her life, with her Scottish doctor, Sir James Reid, knelt on one side of her, as she died at Osborne, forty years after Prince Albert. Her association with the Palace of Holyroodhouse is less celebrated and therefore, is less known. This should not surprise however, because Balmoral was acquired as a private royal residence and Edinburgh would become a useful stopping-point in due time, to reach it.

The Queen and Prince Albert first visited Edinburgh together in September 1842 and the city clearly impressed them, as the Queen wrote in the first volume of her published Highland journals of their first glimpse of Holyrood: ‘ We passed by Holyrood Chapel, which is very old and full of interest, and Holyrood Palace, a royal-looking old place’ (cit., Queen Victoria, Leaves from the journal of our life in the Highlands, 25). Afterwards, the Queen confirmed this feeling, as she wrote to her uncle, King Leopold of the Belgians: ‘H ow much pleased we were with Edinburgh, which is a unique town in its way …’ (cit., A. C. Benson and Viscount Esher, The Letters of Queen Victoria, Vol I, 537). Significantly, as Queen Victoria herself wrote to Baron Stockmar, her and the Prince’s landing at Granton Pier on 1 September 1842 made this royal visit the first ‘where no Sovereign of England has been, since the Union, & none perhaps before, excepting Charles II. ‘ (cit., Delia Millar, Queen Victoria’s Life in the Scottish Highlands, 19).

A statue of Queen Victoria was erected in the forecourt at Holyroodhouse in 1851, where the fountain now stands in our present day. The year before, Lord John Russell had written to Queen Victoria that he thought it appropriate Her Majesty should stay at Holyrood (A. C. Benson and Viscount Esher, The Letters of Queen Victoria, Vol II, 317).

For Queen Victoria, the Palace of Holyroodhouse was a convenient place to stop en route to Balmoral after the freehold was purchased, and the foundation stone for the new castle was laid on 28 September 1853. Similarly, she used the palace as a stopping point on her return journeys south, as she did, for example, in October 1854 on her way back to Windsor. She wrote to King Leopold from Hull that they had spent the night at Holyrood (A. C. Benson and Viscount Esher, The Letters of Queen Victoria, Vol III, 63).

Under Victoria, the Palace of Holyroodhouse became once again, a royal residence. The old royal apartments on the first floor were refurbished, and the water supply renewed. The Queen used the Privy Chamber of Charles II – whom she told Dean Stanley she regarded as one of the most attractive of her predecessors, despite his perceived moral failings (Antonia Fraser, King Charles II, xiii) – for her private Morning Drawing Room; it was expressly renovated for her personal use.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert used Holyroodhouse briefly in the autumn time generally, from 1850 until 1861 (Millar, 132). The artist George M. Greig made a series of paintings of the royal rooms at the Palace between 1862 and 1863, for which he was commissioned by Queen Victoria, who ordered the places refurnished for that purpose. Greig also painted Queen Victoria’s bedroom at Holyroodhouse, today known as the King’s Ante-chamber or Privy Chamber. As the Queen’s bedroom, it contained a four-poster bed with green hangings, a draped dressing-table and beautiful tapestries. Similarly, the Prince Consort’s Sitting Room and Dressing Room is known today as the King’s Bedchamber; its Delft tiles survive.

Significantly, these paintings were made after the death of Prince Albert. At the royal couple’s retreat of Balmoral in their beloved Scottish Highlands, the Prince Consort’s dressing room was kept as he had last used it, according to the Duchess of Teck: ‘The little turret-room poor Albert used as a dressing-room & his bath-room, both left as tho’ he were about to use them. ..’ (cit., Millar, 68). This was of course, a mere Highland equivalent of the Blue Room at Windsor, but without its sacred overtones. When the Duchess of Teck was shown this room at Balmoral in 1868 by the Queen, she saw placed around the curved walls of the room, twenty-two cartes-de-visite of the Prince Consort, in frames, as if the Prince’s missing presence was being multi-replicated, in his absence. By contrast, the Dressing Room at Holyroodhouse was less personal and therefore, treated as less of a private shrine after the death of the Prince.

During Prince Albert’s final days of illness, he lay in the Blue Room at Windsor Castle , the same room in which both George IV and William IV had died, in 1830 and 1837 respectively. Possibly this underlines the Prince Consort’s sense of fatalism – having famously once remarked that he did not cling to life – as we can see from the Queen’s journal that he was pleased at the change of rooms. The Prince’s mind evidently began to wonder, as he murmured his anxieties in French over the Orleanist princes (A. N. Wilson, Victoria, 254) and a week before his death had imagined himself back in Coburg, the land of his childhood, where he longed to hear the twittering birds once more. (Christopher Hibbert, Queen Victoria: A Personal History, 281). He was obviously confused (Ibid, 279), despite the fact that he sat up in his bed on 11 December, the first day that official bulletins were issued concerning his health. The shadows in the Blue Room on one occasion appear to have upset him, because he could see the room’s reflection in a mirror and seems to have imagined himself back in the gloom of the Palace at Holyroodhouse (Elizabeth Longford, Queen Victoria, 323). For this reason, the Queen had the Prince’s pillows lowered, so that he could not see what was reflected in the mirrors. As he was at this point, still being wheeled between bed and sofa, his favourite picture by the door to the Blue Room, a Madonna by his beloved Raphael, clearly comforted him by contrast: ‘It helps me through half the day’. (cit., Ibid, 323).

A letter from Princess Alice, second daughter of Queen Victoria to her mother, confirms that the Queen used the Palace of Holyroodhouse less after the death of the Prince Consort. Writing to the Queen in 1872, she asked: ‘I hope your Edinburgh visit will go off well. You have never lived in Holyrood since 1861, have you ?’ (cit., Alice, Biographical Sketch and Letters, 280).

In Queen Victoria’s second Highland journal, written in her widowhood, More Leaves from the Journal of a Life in the Highlands, from 1862 to 1882, the Queen describes a visit of 13 August 1872: ‘ Visit to Holyrood and Edinburgh’. The Queen wrote: ‘ We drove up to the door of the old, gloomy, but historical Palace of Holyrood, where a guard of honour with a band of the 93 rd Highlanders was stationed in the quadrangle of the court. We got out, walked up the usual stairs, and passed through two of the large gloomy rooms we used to occupy …’ ( cit., Queen Victoria, More Leaves from the Journal of a Life in the Highlands, from 1862 to 1882, 166).

It seems that the Queen had been given a different suite of rooms called the ‘Argyll rooms’, with ‘pretty light paper, chintz, and carpets (chosen by [Princess] Louise’ . The chintzes had ‘ red geraniums on a white ground’ . (cit., Ibid, 166).

An undertone of bereavement fills these secret passages, astonishing to read in published content: ‘ Our rooms are above the old rooms, and have the same look-out… our old rooms… looked sadly deserted: all open and some few things removed from them; the gloomy bedroom with its faded tapestry and green silk bed, and the wretched little dark box-room in which I undressed at night, all full of many recollections …’ (cit., Ibid, 167).

This part of the Palace of Holyroodhouse was painful for the Queen. Her historical interest immediately changed the tone, as she wrote about her visit to the chambers of Mary, Queen of Scots: ‘Beatrice and I with Brown… visited the rooms of Queen Mary, beginning with the Hamilton apartments (which were Lord Darnley’s rooms) and going up the old staircase to Queen Mary’s chamber. In Lord Darnley’s rooms, there are some fine old tapestry and interesting portraits of the Royal family …’ (cit., Ibid, 168).

Writing much later, on her visit to Glencoe, the Queen felt her own ancestry stirring in her blood, sharing perhaps, her uncle George IV’s sentimental fascination with the Stuarts. It was the deep tie of Scottish consanguinity, much older blood that still ran in her veins, much further back than Hanover, to her direct ancestor, James I and his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, via Elizabeth of Bohemia: ‘ For Stuart blood is in my veins & I am now, their representative…’ ( cit., Millar, 19).

It was Queen Mary’s rooms that fascinated Queen Victoria most: ‘ We saw the small secret staircase which led up in the turret to Queen Mary’s bedroom, and we went up another dark old winding staircase at the top of which poor Rizzio was so horribly murdered – whose blood is still supposed to stain the floor… ’ (cit., Ibid, 168). She notes ‘ all hung with old tapestry, and the two little turret rooms; the one where she was supping when poor Rizzio was murdered, the other her dressing-room. Bits of the old tapestry which covered the walls at the time are hung up in frames in the rooms …’ (cit., Ibid, pp. 168-169).

Thanks to Queen Victoria, we have a unique (royal) record of how Queen Mary’s bedroom then appeared (1872): ‘ Thence we were shown into poor Queen Mary’s bedroom, where are the faded old bed she used, the baby-basket sent her by Queen Elizabeth when King James I was born, and her work-box…’ ( cit., Ibid, 168).

Interestingly, Queen Victoria notes that the Presence Chamber then contained: ‘ the bed provided for Charles I when he came to Holyrood to be crowned King of Scotland….’

The old apartments of Mary, Queen of Scots – who lived at Holyrood between 1561 and 1567 – had already begun at the close of the eighteenth century, to exert a particular fascination in the popular imagination. Queen Victoria was, of course, directly descended from the legendary Scottish queen, through the Stuarts via James I’s daughter, Elizabeth of Bohemia. Elizabeth’s daughter Sophie, Hanover’s quite remarkable Electress, was the mother of Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover and also Britain’s first Georgian king. Today, the museum of Stuart ‘relics’ displayed at the end of the apartments of Mary, Queen of Scots is a veritable cabinet of royal curiosities of varying claims, including examples of Mary, Queen of Scots’ needlework, a silver pomander and chain, a crucifix and rosary of Mary, Queen of Scots, two embroidered purses worked by her and a length of hair: ‘ of Mary Queen of Scots, presented to Queen Victoria in 1868 ’, as seen by the present author.

On 5 July 1871, the Waverley Ball was held at Willis’s Rooms, King Street in London’s district of St James’s, to mark both the anniversary of the birth of Sir Walter Scott and to act as a fundraiser for the completion of the Scott memorial in Edinburgh. Queen Victoria’s daughter, Princess Louise, later Duchess of Argyll attended the ball, together with her sister-in-law, Alexandra, the Princess of Wales. Princess Louise made an enchanting watercolour for Queen Victoria of what Alexandr wore that night. She was dressed in sixteenth-century-style, as Mary, Queen of Scots.

Typical of the Queen’s profound reverence for both Scottish heritage as well her lineage is the story concerning Queen Victoria and the Scottish royal vault in the Romanesque arcaded Abbey Church at Holyroodhouse. The roof had fallen in 1758 and thereafter took on the kind of picturesque romanticism which the great English abbeys that had been looted during the Dissolution of the Monasteries conjure up in the present day. Precisely because of this romanticism, the ruined Abbey became a popular place for walking, particularly by moonlight. The Abbey, like the English monasteries – was no accidental ruin.

The artistic sensibilities of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert could not fail to be inspired by the ruins of the Abbey; Prince Albert made a watercolour of the Abbey from one of the palace windows ‘ Albert del Aug: 28 1850’ , whilst the Queen likewise made a watercolour two days later and signed it ‘VR del Aug: 30. 1850’. Probably, Albert had shown her his watercolour. The Queen stayed at Holyrood with Prince Albert and the Royal Family in 1850, whilst Prince Albert laid the foundation stone for the National Gallery of Fine Art in Edinburgh. She made a pen and ink sketch of her watercolour and labelled it: ‘Holyrood Abbey from my windows at Holyrood VR del Aug: 30 – 1850’ .

A vault was constructed at the eastern end of the Abbey Church in the grounds of the Palace of Holyroodhouse, to contain the royal tombs. It was destroyed by the English army under Lord Hertford in 1544 as part of the policy later aptly termed Henry VIII’s ‘Rough Wooing’ in a perverse attempt to win the fealty of the Scots. The devastation was unsparing in its savagery – Edinburgh was burned for two days and the 12 th -century Abbey and Palace of Holyroodhouse destroyed (Antonia Fraser, Mary, Queen of Scots, 29).

The coffin of Mary, Queen of Scots’ father, James V was placed in this burial vault in the Abbey Church; in fact, the controversy over the actual date of death of James V was only finally put to rest when it was discovered engraved on the lid, in the seventeenth century (Ibid, 15). Also buried in the royal vault was James V’s beautiful summer bride, Queen Madeleine, daughter of King Francis I of France, who had come to him with an impressive dowry of 100,000 livres on the wedding day but died a mere two months after her arrival, which meant that mourning veils were worn for the first time in Scotland (Ibid, 7). The coffin of Mary of Gueldres, Queen of James II of Scotland was moved to the vault from Edinburgh’s Trinity Church in 1848. Queen Mary founded the church in around 1460, in memory of her husband. The demolition of the church and its adjoining hospital was overseen by the Edinburgh architect David Bryce to make way for the construction of Waverley Station.

Also placed there were the infant sons of James V by his second wife – the mother of Mary, Queen of Scots, Queen Mary of Guise – the prince of Scotland, who died at Holyrood and also their second son, Robert, Duke of Albany, who had been born at James V’s beloved palace of Falkland in April 1541. In a telling phrase that exactly echoes the words spoken to the English King Henry VII by Queen Elizabeth of York on the death of their eldest son, Arthur, Prince of Wales, Queen Mary of Guise had ‘[ told] the king that they were young enough to expect to have many more children’. (cit., Ibid, 11). They did indeed have another child, destined to become Mary, Queen of Scots; James V died in a state of anguish over the Battle of Solway Moss, on 14 December 1542, leaving the weight of his crown on the shoulders of his baby daughter, born a mere six days previously (Ibid, 4).

The royal vault at Holyroodhouse was plundered during the riots of James VII and II’s reign and left in mournful disarray. In 1898, Queen Victoria ordered that the royal vault in the Abbey Church be repaired, whereupon the remains that were left were interred together in one casket and the vault respectfully sealed. Her journal, however, would not appear to contain any reference to this, as I can find no reference in the Queen’s journals (Princess Beatrice’s copies) for Holyrood after the mid-1880s.

This perhaps recalls Queen Victoria’s similar action in the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula at the Tower of London, which was restored in 1876. The Queen approved that the remains unearthed in the nave during the restoration were reburied in the crypt. Those remains in the chancel beneath the pavement, which included those then ‘identified’ as Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Katherine Howard, were re-interred before the altar, a mere four inches beneath its paving. Octagonal Victorian plaques in a mosaic design record Henry VIII’s two executed queens’ names, armorial crests and the dates in which they died, now mark the resting place of these royal women: ‘ Queen Anne Boleyn MDXXXVI’ and ‘ Queen Katherine Howard, MDXLII’ (Antonia Fraser, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, 520).

The last entry that I can discover in Queen Victoria’s journal (Princess Beatrice’s copies) written from the Palace of Holyroodhouse is for 5 November 1886 (Guy Fawkes Day). The Queen describes leaving Holyrood in the evening and the next journal entry is dated from Windsor, so clearly, she took the Royal Train overnight. The Queen’s farewell to Balmoral was predictably, on a different emotional level, for had she known it, the Queen would be dead within three months of her last Scottish trip. Perhaps fittingly, she was carrying with her back to Windsor, a wreath to lay on the tomb of the Prince Consort in the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore. (Millar, 142). She took her last lunch at Balmoral appropriately, in Prince Albert’s room and drove away from Balmoral, noting that it was ‘ wretchedly gloomy & dark ‘. (cit., Millar, 142). On 6 November 1900, she took the train from Ballater, the nearest station for Balmoral, to Windsor. The journal entry does not mention Edinburgh, but instead, Aberdeen, Perth and Carstairs.

Had the Queen known it, the need for Holyrood en route was at an end.

©Elizabeth Jane Timms, 2019

Share this:.

About author

Elizabeth jane timms, latest posts, queen elizabeth ii's poignant tribute in the most trying of times, eleanor of aquitaine: queen of both france and england, the king makes unexpected walkabout as he attends easter day service, king charles is all smiles as he attends easter service at windsor, never miss the latest, most popular, the queen watches on with pride as lady louise drives prince philip’s carriages at windsor horse show, an annus horribilis in monaco a difficult year for albert and charlene finally winds to an end, the duchess of cambridge wows tv audiences with a musical piano performance on christmas eve, latest blogs.

The royal bride who wore a wedding dress designed by a future king

The pretty diamonds of a princess - and the best royal wedding tiara of all, how a king turned an ancient tradition into a gift of flowers for his queen.

Search This Blog

Nigel's photo blog, queen victoria in scotland.

- Edinburgh Castle was visited by Queen Victoria between 1842 and 1886. She prompted various structural alterations and changes.

- Rosslyn Chapel was a near ruin at the time of the Queen’s visit in 1842. At Victoria’s prompting the chapel was restored and brought back into use as a place of worship. Rosslyn chapel is now one of Scotland’s top visitor attractions as a consequence of featuring in the Da Vinci Code .

- Palace of Holyroodhouse , Edinburgh. Queen Victoria reintroduced the custom of using the Palace as a Royal residence.

- Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were guests of Lord Breadalbane at Taymouth Castle in September, 1842. The Royal couple passed by again in 1866. Located near Kenmore at northern end of Loch Tay. This site is not a visitor attraction but can be viewed from a minor road.

- Blair Castle was visited on occasions from 1844 onwards. This castle is the ancestral home of the Dukes of Atholl. During the 1844 visit the Queen awarded the local military unit, the Atholl Highlanders , the right to bear arms, a right which is still exercised today.

- Queen’s View . A panoramic view of Loch Tummel which was visited by Queen Victoria in 1866. This vista is probably named after the 14th century, Queen Isabella. Near Pitlochry.

- Falls of Bruar. Near Blair Castle. Visited by Queen Victoria in 1844. Warning : These waters contain strong undercurrents. Drownings have occurred.

- Ardoch Roman Fort which had a long period of intermittent military occupation starting from the first century AD. There is a wall plaque recording Victoria and Albert’s visit in 1842. Located at Braco.

- Loch Maree Hotel, Gairloch, Ross-shire. This is on the North Coast 500 route. Queen Victoria stayed here in 1877. It is possible to book the same room as that used by the former monarch.

- Balmoral Castle was purchased by Victoria and Albert in 1848 and remains in the ownership of the Royal Family today. Access for the public is restricted to gardens, grounds and Castle ballroom.

- The small town of Braemar ( near Balmoral) was first visited by Victoria in 1848 when she attended a local Gathering and Highland Games.

- Braemar Castle was visited by the Queen in 1849 as guest of the Farquharson family.

- Royal Lochnagar Distillery . Situated close to Balmoral. The Royal Family visited the distillery in 1848, one of the first ever distillery tours!

- Crathie Kirk . Queen Victoria worshipped here from 1848, a tradition continued by the current Royal Family.

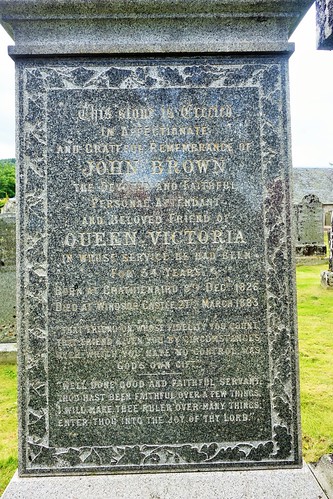

- Grave of Royal servant, John Brown, at Crathie burial ground. John Brown was born near Crathie in 1826 and died 1883.

- Sites on Royal Deeside include: Royal Deeside Railway, Crathes Castle , Aboyne, Finzean Estate, Fettercairn, Cambus O’May Bridge, Ballater, Ballater Old Royal Station, Glen Muick, Linn o' Dee and Mar Lodge and Estate.

© Nigel P Cole/Catswhiskerstours Limited

Post a comment, popular posts from this blog, reconstructed roman villa.

Glen Quaich, one of Scotland's best backroads tour routes

Fort Augustus, a popular visitor site on southern tip of Loch Ness

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Victoria's Visit. For a British monarch, Queen Victoria was extremely quick off the mark in making her first visit to Scotland in 1842, only five years after taking the throne. She was greatly excited by Sir Walter Scott's novels and very anxious to make the acquaintance of her northern kingdom, which soon became one of her favourite haunts ...

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Scotland for the first time in September 1842. During their visit, they stayed at various castles as guests of members of the Scottish nobility. From 7-10 September, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were guests of Lord Breadalbane at Taymouth Castle in Perthshire.

Miller's article was no mere exercise in antiquarianism; the. that had induced him to take up the theme of royal progresses was from his own day - the visit to Scotland from 1-15 September 1842 Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and Sir Robert Peel, the prime minister. This visit, which took the royal party by sea to Edinburgh and was lowed by an ...

3rd June 2019. Queen Victoria’s visited Balmoral in her beloved Scottish Highlands in the late autumn of 1900. The Queen could not know it, but it was the last time that she would see the new ...

1 September – Queen Victoria arrives by sea at Granton, Edinburgh, to start her first visit to Scotland. [5] September – Robert Davidson 's experimental battery-electric locomotive Galvani is demonstrated on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway. The Sobieski Stuarts ' Vestiarium Scoticum is published in Edinburgh, purporting to be a ...

Queen Victoria was entirely ... her and the Prince’s landing at Granton Pier on 1 September 1842 made this royal visit the first ... Queen of James II of Scotland was moved to the vault from ...

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Hawthornden Castle in Midlothian on 14 September 1842, the last day of their first holiday in Scotland. The owners of the castle, the Walker Drummond family, were away from home and so the royal couple paid only a brief visit.

The first part of the Middle Pier was opened on 28 June 1838, the date of Queen Victoria's Coronation, and named the Victoria Jetty in her honour. The Queen and Prince Albert arrived here on 1 September 1842 at the start of their first visit to Scotland. Here the Royal Yacht, the Royal George, is just off the pier surrounded by vessels of all ...

From the moment of her first visit in 1842, Scotland made an impression on Queen Victoria and in turn she would shape how others saw the country in paintings and visual culture. To mark 200 years since the influential monarch's birth on 24 May 1819, curator Freya Spoor reflects on how her legacy can still be seen in Scotland’s national art ...

Rosslyn Chapel was a near ruin at the time of the Queen’s visit in 1842. At Victoria’s prompting the chapel was restored and brought back into use as a place of worship. Rosslyn chapel is now one of Scotland’s top visitor attractions as a consequence of featuring in the Da Vinci Code.