Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

The treatment and prevention of travelers' diarrhea are discussed here. The epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of travelers' diarrhea are discussed separately. (See "Travelers' diarrhea: Epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis" .)

Clinical approach — Management of travelers’ diarrhea depends on the severity of illness. Fluid replacement is an essential component of treatment for all cases of travelers’ diarrhea. Most cases are self-limited and resolve on their own within three to five days of treatment with fluid replacement only. Antimotility agents can provide symptomatic relief but should not be used when bloody diarrhea is present. Antimicrobial therapy shortens the disease duration, but the benefit of antibiotics must be weighed against potential risks, including adverse effects and selection for resistant bacteria. These issues are discussed in the sections that follow.

When to seek care — Travelers from resource-rich settings who develop diarrhea while traveling to resource-limited settings generally can treat themselves rather than seek medical advice while traveling. However, medical evaluation may be warranted in patients who develop high fever, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, or vomiting. Otherwise, for most patients while traveling or after returning home, medical consultation is generally not warranted unless symptoms persist for 10 to 14 days.

Fluid replacement — The primary and most important treatment of travelers' (or any other) diarrhea is fluid replacement, since the most significant complication of diarrhea is volume depletion [ 11,12 ]. The approach to fluid replacement depends on the severity of the diarrhea and volume depletion. Travelers can use the amount of urine passed as a general guide to their level of volume depletion. If they are urinating regularly, even if the color is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely mild. If there is a paucity of urine and that small amount is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely more severe.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Section 2 - Travelers’ Diarrhea

- Section 2 - Food & Water Precautions

Perspectives : Antibiotics in Travelers' Diarrhea - Balancing Benefit & Risk

Cdc yellow book 2024.

Author(s): Mark Riddle, Bradley Connor

For the past 30 years, randomized controlled trials have consistently and clearly demonstrated that antibiotics shorten the duration of illness and alleviate the disability associated with travelers’ diarrhea (TD). Treatment with an effective antibiotic shortens the average duration of a TD episode by 1–2 days, and if the traveler combines an antibiotic with an antimotility agent (e.g., loperamide), duration of illness is shortened even further. Emerging data on the potential long-term health consequences of TD (e.g., chronic constipation, dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome) might suggest a benefit of early antibiotic therapy given the association between more severe and longer disease and risk for postinfectious consequences.

Antibiotics commonly used to treat TD have side effects, some of which are severe but rare. Perhaps of greater concern is the recent understanding that antibiotics used by travelers can contribute to changes in the host microbiome and to the acquisition of multidrug-resistant bacteria. Multiple observational studies have found that travelers (in particular, travelers to South and Southeast Asia) who develop TD and take antibiotics are at risk for colonization with extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE).

The direct effect of colonization on the average traveler appears limited; carriage is most often transient, but it does persist in a small percentage of colonized persons. Elderly travelers (because of the serious consequences of bloodstream infections in this population) and those with a history of recurrent urinary tract infections (because Escherichia coli is a common cause) might be at an increased risk for health consequences from ESBL-PE colonization. At a minimum, clinicians should make these travelers aware of the risk and counsel them to convey their travel exposure history to their treating providers if they become ill after travel. Of broader importance, international travel has been associated with subsequent ESBL-PE colonization among close-living contacts, suggesting potentially wider public health consequences from ESBL-PE acquisition during travel.

The Challenge

The challenge providers and travelers face is how to balance the health benefit of short-course antibiotic treatment of TD with the risk for colonization and global spread of resistance. The role played by travelers in the translocation of infectious disease and resistance cannot be ignored, but the ecology of ESBL-PE infections is complex and includes diet, environment, immigration, and local nosocomial transmission dynamics. ESBL-PE infections are an emerging health threat, and addressing this complex problem will require multiple strategies, including antibiotic stewardship.

An Approach

Health care providers need to have conversations with travelers about the multilevel (individual, community, global) and multifactorial risks of developing TD: travel, individual behaviors (e.g., hand hygiene), diet (e.g., safe selection of foods and beverages), and other risk avoidance measures. But then, knowing it is often difficult to prevent or even reduce the risk for TD through behaviors and diet alone, what is the most reasonable way to prepare travelers for empiric TD self-treatment before a trip? Clinicians can strongly emphasize reserving antibiotics for moderate to severe TD and using antimotility agents for self-treatment of mild TD.

When it comes to managing TD, we expect the traveler to be both diagnostician and health care provider. For even the most astute traveler, making an appropriately informed decision about their own health can be challenged by the anxiety-provoking onset of that first abdominal cramp in sometimes austere and inconvenient settings. Given that TD counseling is competing with numerous other pretravel health topics that need to be covered, travel medicine providers might want to develop and implement simple messaging, handouts, or easy-to-access electronic health guidance. Providing travelers with clear written guidance about TD prevention and step-by-step instructions about how and when to use medications for TD is crucial.

Though further studies are needed (and many are under way), a rational approach involves using a single-dose regimen of an antibiotic that minimizes microbiome disruption and risk for colonization. Additionally, as travel and untreated TD independently increase the risk for ESBL-PE colonization, nonantibiotic chemoprophylactic strategies (e.g., self-treatment with bismuth subsalicylate), can decrease both the acute and posttravel risk concerns. Strengthening the resilience of the host microbiota to prevent infection and unwanted colonization, as with the use of prebiotics or probiotics, are promising potential strategies but need further investigation.

The following authors contributed to the previous version of this chapter: Mark S. Riddle, Bradley A. Connor

Bibliography

Arcilla MS, van Hattem JM, Haverkate MR, Bootsma MCJ, van Genderen PJJ, Goorhuis A, et al. Import and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by international travellers (COMBAT study): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):78–85.

Riddle MS, Connor BA, Beeching NJ, DuPont HL, Hamer DH, Kozarsky P, et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: a graded expert panel report. J Travel Med. 2017;24 (Suppl 1):S57–74.

. . . perspectives chapters supplement the clinical guidance in this book with additional content, context, and expert opinion. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Issues by year

Advertising

Volume 44, Issue 1, January-February 2015

Advising travellers about management of travellers’ diarrhoea

How is td defined.

Classic, severe TD is usually defined as at least three unformed bowel movements occurring within a 24-hour period, often accompanied by cramps, nausea, vomiting, fever and/or blood in the stools. 5–7 Moderate TD is defined as one or two unformed bowel movements and other symptoms occurring every 24 hours or as three or more unformed bowel movements without additional symptoms. Mild TD is defined as one or two unformed bowel movements without any additional symptoms and without interference with daily activities. 8,9 TD generally resolves spontaneously, usually after 3–4 days, 8 but, in the interim, frequently leads to disruption of planned activities.

What are the causes of TD?

Approximately 50–80% of TD is caused by bacterial infections; enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is the most common cause overall. Other bacterial causes include enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), Shigella , Campylobacter and Salmonella species. The exact breakdown of organisms varies according to destination, season and other factors. Noroviruses cause 10–20% of TD cases. Protozoal parasites should be considered particularly in those with persistent diarrhoea (illness lasting ≥14 days) or when antibacterial therapy fails to shorten illness. 10

How can TD be prevented?

Methods for preventing TD include avoidance, immunisation, non-antibiotic interventions or antibiotic prophylaxis. 11

What avoidance measures are generally recommended and do they work?

Avoidance of TD has traditionally relied on recommendations regarding careful food and drink choices (avoiding untreated/unboiled tap water, including ice and water used for brushing teeth, and raw foods such as salads, uncooked vegetables or fruits that cannot be peeled). This underpins the saying ‘Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it…. easy to remember, impossible to do’. Additional standard advice is that undercooked or raw meat, fish and shellfish are high-risk foods. However, whether deliberately or inadvertently, most people find it very difficult to adhere to dietary restrictions 12 and over 95% of people disobey the rules of ‘safe’ eating and drinking within a few days of leaving home. Additionally, there is minimal evidence for a correlation between adherence to dietary precautions and a reduced risk of TD, 13 although common sense nevertheless supports care with food selection. 4

Where people eat may be more important than what people eat. Risks are associated, in descending order, with street vendors, restaurants and private homes. Use of antibacterial handwash before eating is also recommended. 14

Which vaccines can be considered?

Immunisation has little practical role in the prevention of TD and the only potentially relevant vaccines are those against rotavirus (infants only) and the oral cholera vaccine.

The cholera vaccine has >90% efficacy for prevention of Vibrio cholera but travellers are rarely at risk of infection with this pathogen. 1 The vaccine contains a recombinant B subunit of the cholera toxin that is antigenically similar to the heat-labile toxin of ETEC; therefore, the cholera vaccine may also reduce ETEC TD. However, it is not licensed for TD prevention in Australia and, although initially thought to offer a 15–20% short-term (3 months) reduction in TD, a recent Cochrane review showed no statistically significant effects on ETEC diarrhoea or all-cause diarrhoea. 15 Overall, there is, therefore, insufficient evidence to support general use of the cholera vaccine for TD protection, but it may still be considered for individuals with increased risk of severe or complicated TD (eg immunosuppressed or underlying inflammatory bowel disease).

Other vaccines directed against organisms spread by the faecal–oral route are the vaccines for typhoid, hepatitis A and polio, but infection with these organisms rarely causes TD. 15

Do non-antibiotic interventions work?

Several probiotic agents have been studied for treatment and prevention of TD, including Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces preparations. However, their effectiveness for TD prevention has been limited, 11,16,17 and a consensus group has recommended against their use. 4 Other over-the-counter agents are also available (eg travelan, which contains bovine colostrum harvested from cows immunised with an ETEC vaccine) but data regarding overall efficacy of reducing all-cause TD are currently lacking.

Should antibiotic prophylaxis against TD be given?

Quinolone antibiotics are highly effective (80–95%) in preventing TD, but antibiotic prophylaxis is rarely indicated. 4 It may result in a false sense of security and hence less caution in dietary choices, it poses risks of side effects, diarrhoea associated with Clostridium difficile , and, more importantly, would lead to a vast amount of antibiotic use, thus predisposing to more rapid development of antibiotic resistance globally. 11 Therefore non-antibiotic options for prevention and a focus instead on empirical self-treatment if needed according to symptoms are the mainstay of management, aligning with the antimicrobial stewardship perspective of minimisation of antimicrobial overuse and reducing promotion of antimicrobial resistance.

In rare circumstances, it may be reasonable to consider short courses of antibiotic prophylaxis in individuals at very high risk of infection (eg severely immunocompromised). 11 Globally, one of the most commonly used agents in this regard is rifaximin, a non-absorbed semisynthetic rifamycin derivative, which has been shown to be effective and is approved for use for TD prevention in some countries, but it is not approved for this indication in Australia. Other options include the antibiotics discussed below for TD self-treatment.

How should self-treatment of TD be managed?

Because of the limitations of TD prevention measures, the pre-travel consultation should be viewed as an opportunity to ‘arm’ travellers with the knowledge and medication needed to appropriately self-treat, should TD occur during their trip.

The first goal of therapy is the prevention and treatment of dehydration, which is of particular concern for young children, pregnant women and the elderly. Commercial packets of oral rehydration salts are readily available in pharmacies and should be purchased before travel. The other element of TD self-treatment is to recommend travellers bring an antimotility agent plus an antibiotic with them. Loperamide is preferred over the diphenoxylate/atropine combination, as the latter agent is generally less effective and associated with a greater potential for adverse effects.

When should loperamide alone versus loperamide plus an antibiotic be taken?

For mild symptoms of watery diarrhoea, self-treatment with oral rehydration plus loperamide is recommended. Loperamide therapy alone has no untoward effects in mild TD 18 but if symptoms worsen, or do not improve after 24 hours, antibiotics should be added. If TD is moderate or severe at onset, then combination therapy with loperamide plus antibiotics should be started immediately, as this optimises the clinical benefit of self-treatment by providing more rapid relief and shortening the symptom duration. 10,19

The recommended dose of loperamide is two tablets (4 mg) stat, then one tablet after each bowel motion to a maximum of eight per 24-hour period until the TD has resolved. Despite warnings regarding the safety of antidiarrhoeal agents with bloody diarrhoea or diarrhoea accompanied by fever, the combination with antibiotics is likely to be safe in the setting of mild febrile dysentery, 18 and a number of studies have shown the combination to be more efficacious than use of either agent alone. 7,18–20 Rapid institution of effective treatment shortens symptoms to 30 hours or less in most people. 12 For example, the duration of diarrhoea was significantly ( P = 0.0002) shorter following treatment with azithromycin plus loperamide (11 h) than with azithromycin alone (34 h). 19

Which antibiotic should be recommended for empirical elf-treatment of TD?

The most commonly used antibiotics for empirical TD therapy are fluoroquinolones (either norfloxacin or ciprofloxacin) or azithromycin ( Table 1 ). Cotrimoxazole has been used but is no longer recommended because of widespread resistance. For TD caused by ETEC, the fluoroquinolones and azithromycin have similar efficacy; however, in Asia (particularly South and South-East Asia), Campylobacter is a common cause of TD and strains occurring in this part of the world show a high degree of resistance to fluoroquinolones. 10,21 Therefore, azithromycin is preferred for travellers to this region. Azithromycin remains generally efficacious despite emerging resistance, and is also the preferred treatment for diarrhoea with complications of dysentery or high fever, and for use in pregnant women or children under the age of 8 years, in whom avoidance of quinolones is preferred. Moreover, the 24-hour dosing of azithromycin may be preferable to the 12-hourly dosing schedule required with fluoroquinolones.

What is the optimal dosing schedule?

The fluoroquinolones and azithromycin have been administered as a single dose or for 3 days ( Table 1 ). Usually a single dose is adequate and there is no apparent clinically important difference in efficacy with either dosing schedule for TD. 10 However, for bacteria such as Campylobacter and Shigella dysenteriae , single-dose therapy may be inadequate. 11 It is reasonable, therefore, to give travellers a 3-day supply of antibiotics and tell them to continue taking the therapy (either 12- or 24-hourly, depending on which antibiotic is prescribed) only if their TD symptoms persist. If the TD has resolved, no further antibiotics need to be taken and any remaining antibiotic doses can be kept in case of a second bout of TD. It is prudent to specifically highlight that this advice differs from the usual instructions to take all tablets even if symptoms have resolved.

What is the optimal empirical TD management in children?

There are few data on empirical treatment of TD in children and limited options for therapy. The mainstay of therapy is oral rehydration solution, particularly for children <6 years of age. Antimotility agents are contraindicated for children because of the increased risk of adverse effects, especially paralytic ileus, toxic megacolon and drowsiness (narcotic effect) with loperamide. 1 The lower age limit recommended for avoiding loperamide varies by location; US guidelines state that loperamide should not be given to infants <2 years of age, the UK <4 years and Australian guidelines state <12 years. 14 However, most Australian practitioners are prepared to use loperamide in children aged 6 years or older, if needed to control symptoms.

A paediatric (powder) formulation of azithromycin is available and is the most commonly recommended agent for children. The usual dose is 10–25 mg/kg for up to 3 days. A practical tip is to ensure that the pharmacy does not reconstitute the powder into a solution, as once dissolved, the solution lasts only for 10 days. Instead, sterile water should be provided along with instructions on how to reconstitute the powder if needed. Fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin or norfloxacin 10mg/kg bd) are an alternative option if there are reasons for avoiding azithromycin, with previous concerns regarding potential effects on cartilage not substantiated in recent studies. 14,22

Does starting antibiotics early prevent the chances of developing prolonged symptoms?

Although TD symptoms are short-lived in most cases, 8–15% of affected travellers are symptomatic for more than a week and 2% develop chronic diarrhoea lasting a month or more. 11 Episodes of TD have been shown to be associated with a quintuple risk of developing irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and post-travel IBS occurs in 3–10% of travellers. However, it is unknown whether IBS can be prevented by starting antimicrobial therapy earlier in the course of enteric infection. 4,18,23

Should tinidazole also be prescribed and, if so, for whom?

Tinidazole can be prescribed as a second antibiotic for empirical self‑treatment as it is effective against the protozoan parasitic enteric pathogen Giardia intestinalis . A dose of 2 g (4 x 500 mg tablets) stat is recommended. However, for most short-term travellers, tinidazole may be unnecessary and the complexity of the additional instructions required may be unwarranted. It is optimally recommended, therefore, for travellers departing on trips of significant duration (>2–3 weeks). If prescribed, the instructions should be to take tinidazole if the TD persists following the 3-day course of antibiotic therapy (fluoroquinolone or azithromycin). This will mean that the TD has lasted for at least 72 hours, thus increasing the likelihood of a parasitic cause.

When should medical care for acute symptoms be recommended?

While most episodes of TD are amenable to self-treatment, if there is a risk of dehydration due to intolerance of oral fluids or comorbidities, as well as in the setting of frank blood in the stool or unremitting fevers (>38.5°C for 48 hours), medical therapy should be sought. 18

How should TD be managed after return?

While a full description of TD management is beyond the scope of this article, for returning travellers with diarrhoea, at least one (preferably three) stool sample(s) should be taken, including specific requests for evaluation of parasites. For patients who are unwell, particularly those with fevers or dysentery, initiation of empirical antibiotic treatment with azithromycin or a quinolone may be needed while awaiting results. For those with prolonged symptoms, tinidazole as empirical therapy for protozoan parasites may be considered. Endoscopic evaluation may also be advisable if no infectious cause is found and symptoms do not resolve.

- Travellers’ diarrhoea continues to affect 20–50% of people undertaking trips to areas with under-developed sanitation and there is minimal evidence for beneficial effects of dietary precautions.

- Evidence for the benefit of cholera vaccine in reducing TD is limited, but it can be considered in people at high risk of infection.

- In 50–80% of TD cases, TD is caused by bacterial infection. Mild diarrhoea can be managed with an antimotility agent (loperamide) alone, but for moderate or severe diarrhoea, early self-treatment with loperamide in conjunction with antibiotics is advised.

- Recommended empirical antibiotics are fluoroquinolones (norfloxacin / ciprofloxacin) or azithromycin for up to 3 days, although in the setting of increasing resistance, the latter is preferred for travellers to South and South-East Asia.

Competing interests: Karin Leader received a consultancy fee from Imuron in relation to the C. difficile vaccine. She is also an ISTM board member and received a consultancy from ISTM to join the GeoSentinel leadership team. She received grants from Sanofi to develop a mobile phone app for splenectomised patients and from GSK to research the use of the HBV vaccine. GSK also paid her to lecture on travel risks at the Asia Pacific Travel Health Conference. She has received support from both GSK and Sanofi to attend travel medicine conferences.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed

- Diemert DJ. Prevention and self-treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Prim Care 2002;29:843–55. Search PubMed

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers’ Diarrhea. Available at www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/travelersdiarrhea_g.htm [Accessed 25 November 2014]. Search PubMed

- Paredes-Paredes M, Flores-Figueroa J, Dupont HL. Advances in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2011;13:402–07. Search PubMed

- DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJ, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med 2009;16:149–60. Search PubMed

- Nair D. Travelers’ diarrhea: prevention, treatment, and post-trip evaluation. J Fam Pract 2013;62:356–61. Search PubMed

- De Bruyn G, Hahn S, Borwick A. Antibiotic treatment for travellers’ diarrhoea. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000:CD002242. Search PubMed

- Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in traveler’s diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:1007–14. Search PubMed

- Steffen R. Epidemiology of traveler’s diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41(Suppl 8):S536–40. Search PubMed

- Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler’s diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA 1999;281:811–17. Search PubMed

- DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJ, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for self-therapy of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med 2009;16:161–71. Search PubMed

- Diemert DJ. Prevention and self-treatment of traveler’s diarrhea. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:583–94. Search PubMed

- Travelers’ diarrhea. NIH Consensus Development Conference. JAMA 1985;253:2700–04. Search PubMed

- Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent traveler’s diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41(Suppl 8):S531–35. Search PubMed

- Plourde PJ. Travellers’ diarrhea in children. Paediatr Child Health 2003;8:99–103. Search PubMed

- Ahmed T, Bhuiyan TR, Zaman K, Sinclair D, Qadri F. Vaccines for preventing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:CD009029. Search PubMed

- Ritchie ML, Romanuk TN. A meta-analysis of probiotic efficacy for gastrointestinal diseases. PloS One 2012;7:e34938. Search PubMed

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Yellow Book. Chapter 2. Travelers’ Diarrhea. Available at wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-2-the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea [Accessed 25 November 2014]. Search PubMed

- Wingate D, Phillips SF, Lewis SJ, et al. Guidelines for adults on self-medication for the treatment of acute diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:773–82. Search PubMed

- Ericsson CD, DuPont HL, Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, DuPont MW. Loperamide plus azithromycin more effectively treats travelers’ diarrhea in Mexico than azithromycin alone. J Travel Med 2007;14:312–19. Search PubMed

- Murphy GS, Bodhidatta L, Echeverria P, et al. Ciprofloxacin and loperamide in the treatment of bacillary dysentery. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:582–86. Search PubMed

- Tribble DR, Sanders JW, Pang LW, et al. Traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:338–46. Search PubMed

- Yung A, Leder K, Torresi J, et al. Manual of Travel Medicine. 3rd edn. Melbourne: IP Communciations, 2011. Search PubMed

- Stermer E, Lubezky A, Potasman I, Paster E, Lavy A. Is traveler’s diarrhea a significant risk factor for the development of irritable bowel syndrome? A prospective study. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:898–901. Search PubMed

- Expert Group for Antibiotic. Antiobiotic: gastrointestinal tract infections: acute gastroenteritis: acute diarrhoea in special groups: travellers’ diarrhoea. In: eTG Complete [Internet] Melbourne. Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2014. Search PubMed

Also in this issue: Environmental

Professional

Printed from Australian Family Physician - https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2015/january-february/advising-travellers-about-management-of-travellers © The Australian College of General Practitioners www.racgp.org.au

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

Travellers’ diarrhoea

Chinese translation.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Jessica Barrett , infectious diseases registrar 1 ,

- Mike Brown , consultant in infectious diseases and tropical medicine 1 2

- 1 Hospital for Tropical Diseases, University College London Hospitals NHS Trust, London WC1E 6AU, UK

- 2 Clinical Research Department, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK

- Correspondence to: J Barrett jessica.barrett{at}gstt.nhs.uk

What you need to know

Enterotoxic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is the most common cause of acute travellers’ diarrhoea globally

Chronic (>14 days) diarrhoea is less likely to be caused by bacterial pathogens

Prophylactic antibiotic use is only recommended for patients vulnerable to severe sequelae after a short period of diarrhoea, such as those with ileostomies or immune suppression

A short course (1-3 days) of antibiotics taken at the onset of travellers’ diarrhoea reduces the duration of the illness from 3 days to 1.5 days

Refer patients with chronic diarrhoea and associated symptoms such as weight loss for assessment by either an infectious diseases specialist or gastroenterologist

Diarrhoea is a common problem affecting between 20% and 60% of travellers, 1 particularly those visiting low and middle income countries. Travellers’ diarrhoea is defined as an increase in frequency of bowel movements to three or more loose stools per day during a trip abroad, usually to a less economically developed region. This is usually an acute, self limiting condition and is rarely life threatening. In mild cases it can affect the enjoyment of a holiday, and in severe cases it can cause dehydration and sepsis. We review the current epidemiology of travellers’ diarrhoea, evidence for different management strategies, and the investigation and treatment of persistent diarrhoea after travel.

We searched PubMed and Cochrane Library databases for “travellers’ diarrhoea,” and “travel-associated diarrhoea,” to identify relevant articles, which were added to personal reference collections and clinical experience. Where available, systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials were preferentially selected.

Who is at risk?

Variation in incidence 1 2 may reflect the degree of risk for different travel destinations and dietary habits while abroad. Destinations can be divided into low, medium, and high risk (see box 1). Rates of diarrhoea are likely to correlate closely with the quality of local sanitation.

Box 1: Risk of travellers’ diarrhoea according to destination 1 3

High risk destinations.

South and South East Asia*

Central America*

West and North Africa*

South America

East Africa

Medium risk

South Africa

North America

Western Europe

Australia and New Zealand

*Regions with particularly high risk of travellers’ diarrhoea

Backpackers have roughly double the incidence of diarrhoea compared with business travellers. 4 Travel in cruise ships is associated with large outbreaks of viral and bacterial gastroenteritis. 5 General advice is to avoid eating salads, shellfish, and uncooked meats. There is no strong evidence that specific dietary measures reduce incidence of diarrhoea, but studies examining this are likely to be biased by imperfect recall of what was eaten. 6 Risk factors for travellers’ diarrhoea are listed in box 2.

Box 2: Factors increasing risk of travellers’ diarrhoea 4 7 8 9

By increased dietary exposure.

Backpacking

Visiting friends and family

All-inclusive holidays (such as in cruise ships)

By increased susceptibility to an infectious load

Age <6 years

Use of H 2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors

Altered upper gastrointestinal anatomy

Genetic factors (blood group O predisposes to shigellosis and severe cholera infection)

What are the most important causes of travellers’ diarrhoea?

Most studies report a failure to identify the causative pathogen in between 40% and 70% of cases. 10 This includes multicentre studies based in high prevalence settings (that is, during travel). 3 10 11 12 This low diagnostic yield is partly due to delay in obtaining samples and partly due to the insensitivity of laboratory investigations. Older studies did not consistently attempt to identify enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC), and surveillance studies vary in reporting of other E coli species. 3 Where a pathogen is identified, bacteria are the commonest cause of acute travellers’ diarrhoea, with the remainder being caused by norovirus, rotavirus, or similar viruses (see table 1 ⇓ ). Protozoa such as Giardia lamblia can also cause acute diarrhoea, but they are more often associated with persistent diarrhoea, lasting more than two weeks. Cyclospora catayensis , another protozoan cause of diarrhoea, was identified in an increased number of symptomatic travellers returning from Mexico to the UK and Canada in 2015. 13

Frequency of pathogens causing travellers’ diarrhoea 2 3 10 11 12

- View inline

Table 1 ⇑ illustrates overall prevalence of causative agents in returning travellers with diarrhoea. However relative importance varies with country of exposure. Rates of enterotoxigenic E coli (ETEC) are lower in travellers returning from South East Asia than in those returning from South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America, whereas rates of Campylobacter jejuni are higher. Norovirus is a more common cause in travellers to Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, and Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica are more common in travellers to South and South East Asia. 10

The importance of enterotoxigenic E coli as a cause for diarrhoea in travellers returning from Latin America has been decreasing over the past four decades. 10 A large scale analysis of EuroTravNet surveillance data shows increasing incidence of Campylobacter jejuni infection in travellers returning from India, Thailand, and Pakistan. 2

How does travellers’ diarrhoea present?

Most episodes of travellers’ diarrhoea start during the first week of travel, with the peak incidence on the second or third day after arrival. 8 14

Typically diarrhoea caused by enterotoxigenic E coli (“turista”) is watery and profuse, and preceded by abdominal cramps, nausea, and malaise. Symptoms are not a reliable guide to aetiology, but upper gastrointestinal manifestations such as bloating and belching tend to predominate with Giardia lamblia , while colitic symptoms such as urgency, bloody diarrhoea, and cramps are seen more often with Campylobacter jejuni and Shigella spp.

Most episodes will last between one and seven days, with approximately 10% lasting for longer than one week, 5% lasting more than two weeks, and 1% lasting more than 30 days. 8 During the illness, few patients will be severely incapacitated (in one large prospective cohort about 10% of 2800 participants were confined to bed or consulted a physician), but planned activities are often cancelled or postponed. 8

How can travellers’ diarrhoea be prevented?

Several controlled trials have failed to demonstrate an impact of food and drink hygiene advice on rates of diarrhoea. 15 However, the clear food-related source of most diarrhoeal pathogens means that general consensus among travel physicians is to continue to recommend boiling water, cooking food thoroughly, and peeling fruit and vegetables. 6 Other basic advice includes avoiding ice, shellfish, and condiments on restaurant tables, using a straw to drink from bottles, and avoiding salads and buffets where food may have been unrefrigerated for several hours. Travellers should be advised to drink bottled water where available, including in alcoholic drinks, as alcohol does not sterilise non-bottled water. If bottled water is not available, water can be purified by boiling, filtering, or use of chlorine based tablets. 16 There is some weak evidence that use of alcohol hand gel may reduce diarrhoea rates in travellers, 17 but, based on studies in non-travellers, it is reasonable to strongly encourage travellers to adhere to good hand hygiene measures. Two recent systematic reviews estimated hand washing with soap reduces the risk of diarrhoeal illness by 30-40%. 18 19

When is antibiotic prophylaxis recommended?

For most travellers antibiotic chemoprophylaxis (that is, daily antibiotics for the duration of the trip) is not recommended. While diarrhoea is annoying and distressing, severe or long term consequences from a short period of diarrhoea are rare, and routine use of chemoprophylaxis would create a large tablet burden and expose users to possible adverse effects of antibiotic therapy such as candidiasis and diarrhoea associated with Clostridium difficile .

Chemoprophylaxis should be offered to those with severe immune suppression (such as from chemotherapy for malignancy or after a tissue transplant, or advanced HIV infection), underlying intestinal pathology (inflammatory bowel disease, ileostomies, short bowel syndrome), and other conditions such as sickle cell disease or diabetes where reduced oral intake may be particularly dangerous (table 2 ⇓ ). 22 These patient groups may be unable to tolerate the clinical effects and dehydration associated with even mild diarrhoea, or the consequences of more invasive complications such as bacteraemia. For such patients, it is important to discuss the benefits of treatment aimed at preventing diarrhoea and its complications against the risks of antibiotic associated diarrhoea and other side effects. If antibiotics are prescribed then consideration should be given to any possible interactions with other medications that the patient is taking.

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis options for immunosuppressed or other high risk travellers

A small comparative study in US soldiers showed that malaria prophylaxis with daily doxycycline has the added benefit of reducing rates of travellers’ diarrhoea caused by enterotoxigenic E coli and Campylobacter jejuni . 23

Do vaccines have a role in prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea?

Vaccines have been developed and licensed against Salmonella typhi , Vibrio cholerae , and rotavirus—all with reasonable efficacy. However, unlike enterotoxigenic E coli , none of these is a major cause of travellers’ diarrhoea, and only vaccines against S typhi are recommended for most travellers to endemic settings. Phase 3 trials of enterotoxigenic E coli toxin vaccines have been undertaken but have failed to demonstrate efficacy. 24 Studies suggest vaccines against enterotoxigenic E coli would have a major public health impact in high burden countries, and further candidate vaccines are in development. 25

What are the options for self administered treatment?

Table 3 ⇓ summarises the options for self treatment.

Summary of self treatment choices

Anti-motility agents and oral rehydration therapy

For most cases of travellers’ diarrhoea, oral rehydration is the mainstay of treatment. This can be achieved with clear fluids such as diluted fruit juice or soups. Young children, elderly people, and those at greater risk from dehydration (that is, those with medical comorbidities) are recommended to use oral rehydration salts (or a mixture of six level teaspoons of sugar and half a teaspoon of salt in a litre of clean water if rehydration salts are unavailable) (see http://rehydrate.org/rehydration/index.html ).

Anti-motility agents such as loperamide may be appropriate for mild symptoms, or where rapid cessation of diarrhoea is essential. Case reports of adverse outcomes such as intestinal perforation suggest anti-motility agents should be avoided in the presence of severe abdominal pain or bloody diarrhoea, which can signify invasive colitis. 26 Systematic review of several randomised controlled trials have demonstrated a small benefit from taking bismuth subsalicylate, but this has less efficacy in reducing diarrhoea frequency and severity than loperamide. 27

Antibiotics

Symptomatic treatment is usually adequate and reduces antibiotic use. However, some travellers will benefit from rapid cessation of diarrhoea, particularly if they are in a remote area with limited access to sanitation facilities or healthcare. Several systematic reviews of studies comparing antibiotics (including quinolones, azithromycin, and rifaximin) against placebo have shown consistent shortening of the duration of diarrhoea to about one and a half days from around three days. 28 29 30 Short courses (one to three days) of antibiotics are usually sufficient to effect a cure. 30

For some people travelling to high and moderate risk areas (see box 1) it will be appropriate to provide a short course of a suitable antibiotic, with advice to start treatment as soon as they develop diarrhoea and to keep well hydrated. Choice of antibiotic will depend on allergy history, comorbidities, concomitant medications, and destination. Avoid quinolones for both prophylaxis and treatment of travellers to South East and South Asia as levels of quinolone resistance are high. 31 Azithromycin remains effective in these areas, but resistance rates are likely to increase.

A meta-analysis of nine randomised trials showed that the addition of loperamide to antibiotic treatment (including azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and rifamixin) resulted in statistically significantly higher rates of cure at 24 and 48 hours compared with antibiotic alone. 32 Travellers can be advised to add loperamide to their antibiotic treatment to reduce the time to symptomatic improvement as long as there are no features of invasive colitis such as severe pain, high fever, or blood visible in the diarrhoea. 30 If any of these symptoms develop, travellers are advised to seek medical advice immediately.

Returned travellers with persistent diarrhoea

Most bacterial causes mentioned do not cause persistent diarrhoea in immune competent adults. Travellers with diarrhoea persisting beyond 14 days may present in primary or secondary care on their return and require assessment for other underlying causes of persistent diarrhoea.

Table 4 ⇓ lists the important clinical history and symptoms that can point to the underlying cause.

Assessment of chronic diarrhoea

What investigations should be sent?

For diarrhoeal symptoms that persist beyond 14 days following travel (or sooner if there are other concerning features such as fever or dysentery), offer patients blood tests for full blood count, liver and renal function, and inflammatory markers; stool samples for microscopy and culture; and examination for ova, cysts, and parasites. Historically, advice has been to send three stool samples for bacterial culture, but this is unlikely to increase the diagnostic yield. Instead, stool microscopy can be used to distinguish inflammatory from non-inflammatory causes: a small observational study found presence of faecal leucocytes was predictive of a positive bacterial stool culture. 33 Yield from stool culture may be increased by dilution of the faecal sample, and the introduction of molecular tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for common gastrointestinal pathogens such as Campylobacter spp may decrease turnaround times and increase yield. 34

Additional tests should be offered according to symptoms and risk (table 4 ⇑ ). If the patient has eosinophilia and an appropriate travel history, the possibility of schistosomiasis, strongyloides, and other helminthic infections should be considered. While schistosomiasis can rarely cause diarrhoea in the context of acute infection, serology may be negative in the first few months of the illness.

Imaging is required only if the patient has signs of severe colitis or local tenderness, in which instances toxic megacolon, inflammatory phlegmon, and hepatic collections should be excluded. Patients with severe colitis or proctitis may need joint assessment with gastroenterology and consideration of endoscopy, or laparotomy if perforation has occurred.

Where infectious and non-infectious causes have been appropriately excluded, the most likely diagnosis is post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome, although diarrhoea can also herald underlying bowel pathology and anyone with red flags for malignancy should be referred by the appropriate pathway for assessment. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome has an incidence of around 30% after an acute episode of travel associated gastroenteritis. 35 36 It is more commonly a sequela of prolonged episodes of diarrhoea or diarrhoea associated with fever and bloody stools. 36 There is weak evidence from small randomised trials suggesting that exclusion of foods high in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAP) may be helpful. 37 Exclusion of dietary lactose and use of loperamide, bile acid sequestrants, and probiotics can also be tried, but there is limited evidence for long term benefit. 35 37 38

How should giardiasis be managed?

The most common pathogen identified in returning travellers with chronic diarrhoea is Giardia lamblia, particularly among people returning from South Asia. 39 Use of G lamblia PCR testing has increased detection, 40 which potentially will identify infection in some patients previously labelled as having post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and in those whose diarrhoea may have been attributed to non-pathogenic protozoa. Most patients respond to 5-nitroimidazoles (a systematic review of a large number of trials has shown similar cure rates with tinidazole 2 g once only or metronidazole 400 mg three times daily for five days 41 ), but refractory cases are increasingly common and require investigation, identification of underlying risk factors, and repeated treatment (various antimicrobials have been shown to be effective but may have challenging risk profiles). .

Questions for future research

What is the justification for using antibiotics to treat a usually self limiting illness, in the wider context of rising levels of global antimicrobial resistance rates? What is the clinical impact of resistant enterobacteriaciae found in stool samples from returning travellers? 42 43

To what extent do host genetic factors increase susceptibility to gastrointestinal pathogens, and can this help to identify at risk populations and tailor treatments to individual patients?

What is the long term efficacy of new pharmacological treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and rifaximin in post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome?

Tips for non-specialists

Include consideration of chemoprophylaxis for high risk individuals in pre-travel assessment

Advise all travellers on hygiene measures (such as hand washing and food consumption) and symptom management of diarrhoea

Avoid quinolones for prophylaxis or treatment in travellers to South East and South Asia

Where diarrhoea persists beyond 14 days, consider investigations to rule out parasitic and non-infectious causes. The presence of white blood cells on stool microscopy indicates an inflammatory cause

Additional educational resources

Resources for patients.

National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC): http://travelhealthpro.org.uk/travellers-diarrhoea/

Provides pre-travel advice, as well as links to country-specific advice

Fit for Travel: www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/advice/disease-prevention-advice/travellers-diarrhoea.aspx

Provides similar pre-travel advice on hygiene and disease prevention

Patient.co.uk: http://patient.info/doctor/travellers-diarrhoea-pro

Has patient leaflets and more detailed information about investigation and management of travellers’ diarrhoea

Resources for healthcare professionals

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention yellow book: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea

Provides a guide to pre-travel couselling

Rehydration Project website: http://rehydrate.org/rehydration/index.html

Has additional information about non-pharmacological management of diarrhoea

How patients were involved in the creation of the article

No patients were involved in the creation of this review.

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to the preparation of this manuscript. MB is guarantor. We thank Dr Ron Behrens for sharing his extensive expertise on this subject.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ Greenwood Z, Black J, Weld L, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Gastrointestinal infection among international travelers globally. J Travel Med 2008 ; 15 : 221 - 8 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00203.x pmid:18666921 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Schlagenhauf P, Weld L, Goorhuis A, et al. EuroTravNet. Travel-associated infection presenting in Europe (2008-12): an analysis of EuroTravNet longitudinal, surveillance data, and evaluation of the effect of the pre-travel consultation. Lancet Infect Dis 2015 ; 15 : 55 - 64 . doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71000-X pmid:25477022 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Health Protection Agency. Foreign travel-associated illness: a focus on travellers’ diarrhoea. HPA, 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140714084352/http:/www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1287146380314 .

- ↵ Schindler VM, Jaeger VK, Held L, Hatz C, Bühler S. Travel style is a major risk factor for diarrhoea in India: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015 ; 21 : 676.e1 - 4 . doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.005 pmid:25882361 . OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Freeland AL, Vaughan GH Jr, , Banerjee SN. Acute gastroenteritis on cruise ships - United States, 2008-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016 ; 65 : 1 - 5 . doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6501a1 pmid:26766396 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJ, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med 2009 ; 16 : 149 - 60 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00299.x pmid:19538575 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Bavishi C, Dupont HL. Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011 ; 34 : 1269 - 81 . doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04874.x pmid:21999643 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Pitzurra R, Steffen R, Tschopp A, Mutsch M. Diarrhoea in a large prospective cohort of European travellers to resource-limited destinations. BMC Infect Dis 2010 ; 10 : 231 . doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-231 pmid:20684768 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Flores J, Okhuysen PC. Genetics of susceptibility to infection with enteric pathogens. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009 ; 22 : 471 - 6 . doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283304eb6 pmid:19633551 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009 ; 80 : 609 - 14 . pmid:19346386 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ von Sonnenburg F, Tornieporth N, Waiyaki P, et al. Risk and aetiology of diarrhoea at various tourist destinations. Lancet 2000 ; 356 : 133 - 4 . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02451-X pmid:10963251 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler’s diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA 1999 ; 281 : 811 - 7 . doi:10.1001/jama.281.9.811 pmid:10071002 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Nichols GL, Freedman J, Pollock KG, et al. Cyclospora infection linked to travel to Mexico, June to September 2015. Euro Surveill 2015 ; 20 . doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.43.30048 pmid:26536814 .

- ↵ Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler’s diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA. 1999 ; 281 : 811 - 7 . doi:10.1001/jama.281.9.811 pmid:10071002 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ DuPont HL. Systematic review: prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008 ; 27 : 741 - 51 . doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03647.x pmid:18284650 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Clasen TF, Alexander KT, Sinclair D, et al. Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 ; 10 : CD004794 . pmid:26488938 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Henriey D, Delmont J, Gautret P. Does the use of alcohol-based hand gel sanitizer reduce travellers’ diarrhea and gastrointestinal upset?: A preliminary survey. Travel Med Infect Dis 2014 ; 12 : 494 - 8 . doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.07.002 pmid:25065273 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Ejemot-Nwadiaro RI, Ehiri JE, Arikpo D, Meremikwu MM, Critchley JA. Hand washing promotion for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 ; 9 : CD004265 . pmid:26346329 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Freeman MC, Stocks ME, Cumming O, et al. Hygiene and health: systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects. Trop Med Int Health 2014 ; 19 : 906 - 16 . doi:10.1111/tmi.12339 pmid:24889816 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Hu Y, Ren J, Zhan M, Li W, Dai H. Efficacy of rifaximin in prevention of travelers’ diarrhea: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Travel Med 2012 ; 19 : 352 - 6 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00650.x pmid:23379704 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- Alajbegovic S, Sanders JW, Atherly DE, Riddle MS. Effectiveness of rifaximin and fluoroquinolones in preventing travelers’ diarrhea (TD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2012 ; 1 : 39 . doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-39 pmid:22929178 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Sommet J, Missud F, Holvoet L, et al. Morbidity among child travellers with sickle-cell disease visiting tropical areas: an observational study in a French tertiary care centre. Arch Dis Child 2013 ; 98 : 533 - 6 . doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-302500 pmid:23661574 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Arthur JD, Echeverria P, Shanks GD, Karwacki J, Bodhidatta L, Brown JE. A comparative study of gastrointestinal infections in United States soldiers receiving doxycycline or mefloquine for malaria prophylaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1990 ; 43 : 608 - 13 . pmid:2267964 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Behrens RH, Cramer JP, Jelinek T, et al. Efficacy and safety of a patch vaccine containing heat-labile toxin from Escherichia coli against travellers’ diarrhoea: a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled field trial in travellers from Europe to Mexico and Guatemala. Lancet Infect Dis 2014 ; 14 : 197 - 204 . doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70297-4 pmid:24291168 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Bourgeois AL, Wierzba TF, Walker RI. Status of vaccine research and development for enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Vaccine 2016 ; S0264-410X(16)00287-5 . pmid:26988259 .

- ↵ McGregor A, Brown M, Thway K, Wright SG. Fulminant amoebic colitis following loperamide use. J Travel Med 2007 ; 14 : 61 - 2 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00096.x pmid:17241255 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Heather CS. Travellers’ diarrhoea. Systematic review 901. BMJ Clin Evid 2015 www.clinicalevidence.com/x/systematic-review/0901/overview.html .

- ↵ De Bruyn G, Hahn S, Borwick A. Antibiotic treatment for travellers’ diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000 ;( 3 ): CD002242 . pmid:10908534 .

- ↵ Ternhag A, Asikainen T, Giesecke J, Ekdahl K. A meta-analysis on the effects of antibiotic treatment on duration of symptoms caused by infection with Campylobacter species. Clin Infect Dis 2007 ; 44 : 696 - 700 . doi:10.1086/509924 pmid:17278062 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Steffen R, Hill DR, DuPont HL. Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review. JAMA 2015 ; 313 : 71 - 80 . doi:10.1001/jama.2014.17006 pmid:25562268 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Dalhoff A. Global fluoroquinolone resistance epidemiology and implictions for clinical use. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2012 ; 2012 : 976273 . pmid:23097666 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in traveler’s diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2008 ; 47 : 1007 - 14 . doi:10.1086/591703 pmid:18781873 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ McGregor AC, Whitty CJ, Wright SG. Geographic, symptomatic and laboratory predictors of parasitic and bacterial causes of diarrhoea in travellers. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012 ; 106 : 549 - 53 . doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2012.04.008 pmid:22818743 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Public Health England. Investigations of faecal specimens for enteric pathogens. UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations. B 30 Issue 8.1. 2014. www.hpa.org.uk/SMI/pdf .

- ↵ DuPont AW. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2008 ; 46 : 594 - 9 . doi:10.1086/526774 pmid:18205536 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Schwille-Kiuntke J, Mazurak N, Enck P. Systematic review with meta-analysis: post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome after travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015 ; 41 : 1029 - 37 . doi:10.1111/apt.13199 pmid:25871571 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Halland M, Saito YA. Irritable bowel syndrome: new and emerging treatments. BMJ 2015 ; 350 : h1622 . doi:10.1136/bmj.h1622 pmid:26088265 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Orekoya O, McLaughlin J, Leitao E, Johns W, Lal S, Paine P. Quantifying bile acid malabsorption helps predict response and tailor sequestrant therapy. Clin Med (Lond) 2015 ; 15 : 252 - 7 . doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.15-3-252 pmid:26031975 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Swaminathan A, Torresi J, Schlagenhauf P, et al. GeoSentinel Network. A global study of pathogens and host risk factors associated with infectious gastrointestinal disease in returned international travellers. J Infect 2009 ; 59 : 19 - 27 . doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2009.05.008 pmid:19552961 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Nabarro LE, Lever RA, Armstrong M, Chiodini PL. Increased incidence of nitroimidazole-refractory giardiasis at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, London: 2008-2013. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015 ; 21 : 791 - 6 . doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.04.019 pmid:25975511 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Pasupuleti V, Escobedo AA, Deshpande A, Thota P, Roman Y, Hernandez AV. Efficacy of 5-nitroimidazoles for the treatment of giardiasis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014 ; 8 : e2733 . doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002733 pmid:24625554 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Tham J, Odenholt I, Walder M, Brolund A, Ahl J, Melander E. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in patients with travellers’ diarrhoea. Scand J Infect Dis 2010 ; 42 : 275 - 80 . doi:10.3109/00365540903493715 pmid:20121649 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Kantele A. A call to restrict prescribing antibiotics for travellers’ diarrhea--Travel medicine practitioners can play an active role in preventing the spread of antimicrobial resistance. Travel Med Infect Dis 2015 ; 13 : 213 - 4 . doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.05.005 pmid:26005160 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Traveler's diarrhea

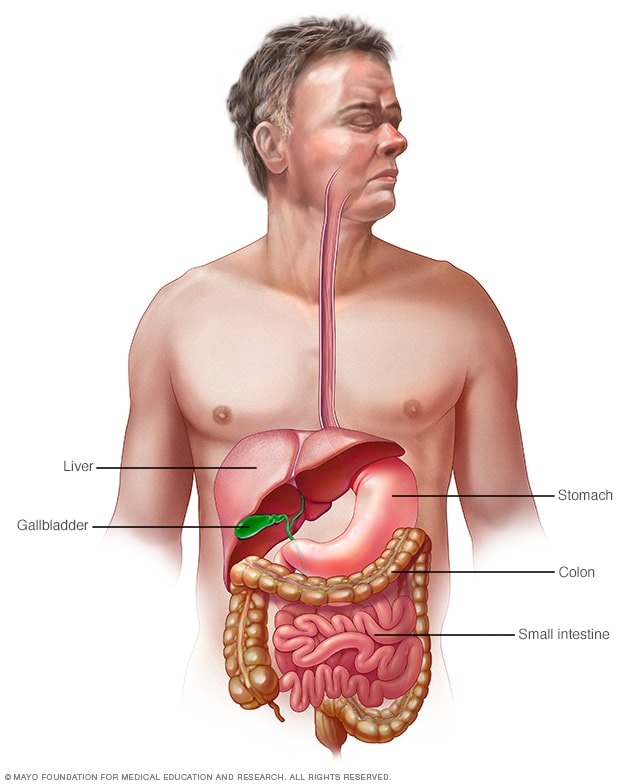

Gastrointestinal tract

Your digestive tract stretches from your mouth to your anus. It includes the organs necessary to digest food, absorb nutrients and process waste.

Traveler's diarrhea is a digestive tract disorder that commonly causes loose stools and stomach cramps. It's caused by eating contaminated food or drinking contaminated water. Fortunately, traveler's diarrhea usually isn't serious in most people — it's just unpleasant.

When you visit a place where the climate or sanitary practices are different from yours at home, you have an increased risk of developing traveler's diarrhea.

To reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea, be careful about what you eat and drink while traveling. If you do develop traveler's diarrhea, chances are it will go away without treatment. However, it's a good idea to have doctor-approved medicines with you when you travel to high-risk areas. This way, you'll be prepared in case diarrhea gets severe or won't go away.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

Traveler's diarrhea may begin suddenly during your trip or shortly after you return home. Most people improve within 1 to 2 days without treatment and recover completely within a week. However, you can have multiple episodes of traveler's diarrhea during one trip.

The most common symptoms of traveler's diarrhea are:

- Suddenly passing three or more looser watery stools a day.

- An urgent need to pass stool.

- Stomach cramps.

Sometimes, people experience moderate to severe dehydration, ongoing vomiting, a high fever, bloody stools, or severe pain in the belly or rectum. If you or your child experiences any of these symptoms or if the diarrhea lasts longer than a few days, it's time to see a health care professional.

When to see a doctor

Traveler's diarrhea usually goes away on its own within several days. Symptoms may last longer and be more severe if it's caused by certain bacteria or parasites. In such cases, you may need prescription medicines to help you get better.

If you're an adult, see your doctor if:

- Your diarrhea lasts beyond two days.

- You become dehydrated.

- You have severe stomach or rectal pain.

- You have bloody or black stools.

- You have a fever above 102 F (39 C).

While traveling internationally, a local embassy or consulate may be able to help you find a well-regarded medical professional who speaks your language.

Be especially cautious with children because traveler's diarrhea can cause severe dehydration in a short time. Call a doctor if your child is sick and has any of the following symptoms:

- Ongoing vomiting.

- A fever of 102 F (39 C) or more.

- Bloody stools or severe diarrhea.

- Dry mouth or crying without tears.

- Signs of being unusually sleepy, drowsy or unresponsive.

- Decreased volume of urine, including fewer wet diapers in infants.

It's possible that traveler's diarrhea may stem from the stress of traveling or a change in diet. But usually infectious agents — such as bacteria, viruses or parasites — are to blame. You typically develop traveler's diarrhea after ingesting food or water contaminated with organisms from feces.

So why aren't natives of high-risk countries affected in the same way? Often their bodies have become used to the bacteria and have developed immunity to them.

Risk factors

Each year millions of international travelers experience traveler's diarrhea. High-risk destinations for traveler's diarrhea include areas of:

- Central America.

- South America.

- South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Traveling to Eastern Europe, South Africa, Central and East Asia, the Middle East, and a few Caribbean islands also poses some risk. However, your risk of traveler's diarrhea is generally low in Northern and Western Europe, Japan, Canada, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Your chances of getting traveler's diarrhea are mostly determined by your destination. But certain groups of people have a greater risk of developing the condition. These include:

- Young adults. The condition is slightly more common in young adult tourists. Though the reasons why aren't clear, it's possible that young adults lack acquired immunity. They may also be more adventurous than older people in their travels and dietary choices, or they may be less careful about avoiding contaminated foods.

- People with weakened immune systems. A weakened immune system due to an underlying illness or immune-suppressing medicines such as corticosteroids increases risk of infections.

- People with diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, or severe kidney, liver or heart disease. These conditions can leave you more prone to infection or increase your risk of a more-severe infection.

- People who take acid blockers or antacids. Acid in the stomach tends to destroy organisms, so a reduction in stomach acid may leave more opportunity for bacterial survival.

- People who travel during certain seasons. The risk of traveler's diarrhea varies by season in certain parts of the world. For example, risk is highest in South Asia during the hot months just before the monsoons.

Complications

Because you lose vital fluids, salts and minerals during a bout with traveler's diarrhea, you may become dehydrated, especially during the summer months. Dehydration is especially dangerous for children, older adults and people with weakened immune systems.

Dehydration caused by diarrhea can cause serious complications, including organ damage, shock or coma. Symptoms of dehydration include a very dry mouth, intense thirst, little or no urination, dizziness, or extreme weakness.

Watch what you eat

The general rule of thumb when traveling to another country is this: Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it. But it's still possible to get sick even if you follow these rules.

Other tips that may help decrease your risk of getting sick include:

- Don't consume food from street vendors.

- Don't consume unpasteurized milk and dairy products, including ice cream.

- Don't eat raw or undercooked meat, fish and shellfish.

- Don't eat moist food at room temperature, such as sauces and buffet offerings.

- Eat foods that are well cooked and served hot.

- Stick to fruits and vegetables that you can peel yourself, such as bananas, oranges and avocados. Stay away from salads and from fruits you can't peel, such as grapes and berries.

- Be aware that alcohol in a drink won't keep you safe from contaminated water or ice.

Don't drink the water

When visiting high-risk areas, keep the following tips in mind:

- Don't drink unsterilized water — from tap, well or stream. If you need to consume local water, boil it for three minutes. Let the water cool naturally and store it in a clean covered container.

- Don't use locally made ice cubes or drink mixed fruit juices made with tap water.

- Beware of sliced fruit that may have been washed in contaminated water.

- Use bottled or boiled water to mix baby formula.

- Order hot beverages, such as coffee or tea, and make sure they're steaming hot.

- Feel free to drink canned or bottled drinks in their original containers — including water, carbonated beverages, beer or wine — as long as you break the seals on the containers yourself. Wipe off any can or bottle before drinking or pouring.

- Use bottled water to brush your teeth.

- Don't swim in water that may be contaminated.

- Keep your mouth closed while showering.

If it's not possible to buy bottled water or boil your water, bring some means to purify water. Consider a water-filter pump with a microstrainer filter that can filter out small microorganisms.

You also can chemically disinfect water with iodine or chlorine. Iodine tends to be more effective, but is best reserved for short trips, as too much iodine can be harmful to your system. You can purchase water-disinfecting tablets containing chlorine, iodine tablets or crystals, or other disinfecting agents at camping stores and pharmacies. Be sure to follow the directions on the package.

Follow additional tips

Here are other ways to reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea:

- Make sure dishes and utensils are clean and dry before using them.

- Wash your hands often and always before eating. If washing isn't possible, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol to clean your hands before eating.

- Seek out food items that require little handling in preparation.

- Keep children from putting things — including their dirty hands — in their mouths. If possible, keep infants from crawling on dirty floors.

- Tie a colored ribbon around the bathroom faucet to remind you not to drink — or brush your teeth with — tap water.

Other preventive measures

Public health experts generally don't recommend taking antibiotics to prevent traveler's diarrhea, because doing so can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotics provide no protection against viruses and parasites, but they can give travelers a false sense of security about the risks of consuming local foods and beverages. They also can cause unpleasant side effects, such as skin rashes, skin reactions to the sun and vaginal yeast infections.

As a preventive measure, some doctors suggest taking bismuth subsalicylate, which has been shown to decrease the likelihood of diarrhea. However, don't take this medicine for longer than three weeks, and don't take it at all if you're pregnant or allergic to aspirin. Talk to your doctor before taking bismuth subsalicylate if you're taking certain medicines, such as anticoagulants.

Common harmless side effects of bismuth subsalicylate include a black-colored tongue and dark stools. In some cases, it can cause constipation, nausea and, rarely, ringing in your ears, called tinnitus.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Infectious enteritis and proctocolitis. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Microbiology, epidemiology, and prevention. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Ferri FF. Traveler diarrhea. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Elsevier; 2023. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Diarrhea. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/diarrhea. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Travelers' diarrhea. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/travelers-diarrhea. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Khanna S (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 29, 2021.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

GREGORY JUCKETT, M.D.

Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(1):119-124

See related patient information handout on traveler's diarrhea , written by the author of this article .

Common pathogens in traveler's diarrhea include enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli , Campylobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia and many other species. Viruses and protozoa are the cause in many cases. Fortunately, traveler's diarrhea can usually be avoided by carefully selecting foods and beverages. Although drug prophylaxis is now discouraged, treatment with loperamide (in the absence of dysentery) and a fluoroquinolone, such as ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily for one to three days), is usually safe and effective in adults with traveler's diarrhea. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline are alternatives, but resistance increasingly limits their usefulness. Antibiotic treatment is best reserved for cases that fail to quickly respond to loperamide. Antibiotic resistance is now widespread. Nonabsorbable antibiotics, immunoprophylaxis with vaccines and biotherapeutic microbes that inhibit pathogen infection may eventually supplant antibiotic treatment. In the meantime, azithromycin and new fluoroquinolones show promise as possible replacements for the older agents. Ultimately, the best solution is improvements in sanitary engineering and the development of safe water supplies.

Travel to destinations such as Latin America, Asia, Africa and the Middle East has never been more popular, with over 20 million travelers visiting a less developed country each year. 1 Approximately one third (20 to 50 percent) of travelers to less developed areas of the world become ill from ingesting fecally contaminated food or water. 2 , 3 In 10 to 20 percent of cases, fever and bloody stools (dysentery) occur. 2

Although traveler's diarrhea usually resolves within three to five days (mean duration: 3.6 days), in about 20 percent of persons the illness is severe enough to cause bed confinement and in 10 percent of cases the illness lasts more than one week. 3 , 4 In the very young and the very old, as well as in those who are immunocompromised, traveler's diarrhea can occasionally be life-threatening. It is important to realize, however, that traveler's diarrhea can be minimized by education about ways to prevent the disease. Physicians can do a great deal to ensure that their patients have a safe and enjoyable trip abroad.

Epidemiology

Traveler's diarrhea is defined as three or more unformed stools in 24 hours in a person from an industrialized nation traveling in a less developed country. Unlike in the United States, where most diarrheal disease is viral in origin, in developing countries, bacterial infection is the cause of diarrhea in at least 80 percent of cases. Viral, protozoal or undetermined etiologies account for the remainder of cases. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is the chief pathogen, accounting for 40 to 50 percent of cases. 5 Other common bacterial causes include Campylobacter jejuni , Shigella, Salmonella, Aeromonas and Yersinia species, Plesiomonas shigelloides and Vibrio parahaemolyticus ( Table 1 ) . All of these agents are efficiently spread by the fecal-oral route and, in some cases, such as Shigella infections, a minute inoculum (as few as 10 to 100 organisms) is all that is necessary to produce disease.

Without stool cultures for identifying the pathogen in diarrheal illness, it is easy to confuse the symptoms of traveler's diarrhea with those of food poisoning produced by heat-stable, toxin-forming bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus or by the heat-labile toxin of Clostridium perfringens . In general, however, preformed toxins (Staphylococcus and Bacillus) produce symptoms within one to six hours, whereas infections (such as from Clostridium) that result in toxin formation in vivo cause symptoms within eight to 16 hours. Most invasive bacterial infections, on the other hand, become symptomatic after 16 hours. 6

Viruses that are responsible for traveler's diarrhea in the tropics include rotavirus and Norwalk agents. Diarrhea caused by viral agents is usually self-limited.

The three major protozoal causes of traveler's diarrhea are Entamoeba histolytica , Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium parvum . Diarrheal disease caused by these organisms is notable for its longer duration and failure to respond to routine antibiotic therapy.

Risk factors for traveler's diarrhea are listed in Table 2 . Persons from a developing region who have relocated to an industrialized country and who then return to their country of origin are also at increased risk, especially since they seldom take precautions. Any “native resistance” is soon lost after relocation and subsequent alteration of the intestinal flora.

Traveler's diarrhea is fundamentally a sanitation failure, leading to bacterial contamination of food and water. It is best prevented through proper sewage treatment and water disinfection. In the absence of these amenities, the next best option is for the educated traveler to take precautions to prevent the disease.

Preventive measures include not drinking tap water, not using ice in beverages (even alcoholic drinks), not eating salads and other forms of raw vegetables, not eating fruits that can't be peeled on the spot and not eating mayonnaise, pastry icing, unpasteurized dairy products and undercooked shellfish.