Use this tool to add tone marks to pinyin or to convert tone number (e.g. hao3) to tone marks.

Although you can use the red buttons to add tone marks, we highly recommend you use the number method (e.g. hao3) for speed and placement of the accent above the correct vowel. [Hint: Type "v" for "ü"] Note: You do not need to use this tool to enter pinyin in this dictionary.

Create Unlimited Lists

Your Quick List has reached 50 flashcards. Delete some words, or unlock unlimited flashcard sets.

Showing Results in:

- SEE TRADITIONAL

- SEE CANTONESE

Learn more about 旅行

- Written Chinese

- "旅行" Character Details

How do you remember 旅行 ?

Post your photos, example sentences and daily homework here to share with the Chinese learning community.

Measure Words for 旅行

How to use 旅行 in a sentence.

He planned to tour india this winter.

Do you have any suggestions about this trip?

We should make sure the children are safe during the trip.

There were unseen dangers from every side for the travellers.

Her journey was rather an expression of her independence of the old world.

Trains are reliable, cheap and best for long-distance journeys.

She travels con-stantly, moving among her several residences around the world.

Traveling with the bands was a broadening experience for the musicians, who were usually self - taught .

People wear slacks, sweaters, flat shoes, and all manner of casual attire for travel.

Data from Voyager II has presented astronomers with a puzzle about why our outermost planet exists.

- Chinese Characters with 1 Stroke

- Chinese Characters with 2 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 3 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 4 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 5 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 6 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 7 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 8 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 9 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 10 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 11 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 12 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 13 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 14 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 15 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 16 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 17 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 18 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 19 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 20 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 21 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 22 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 23 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 24 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 25 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 26 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 27 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 28 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 29 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 30 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 31 Strokes

- Chinese Characters with 32 Strokes

Daily Mandarin Lesson: "Travel" in Chinese

How to Use the Chinese Term 旅行 Lu Xing

- Mandarin History and Culture

Pronunciation

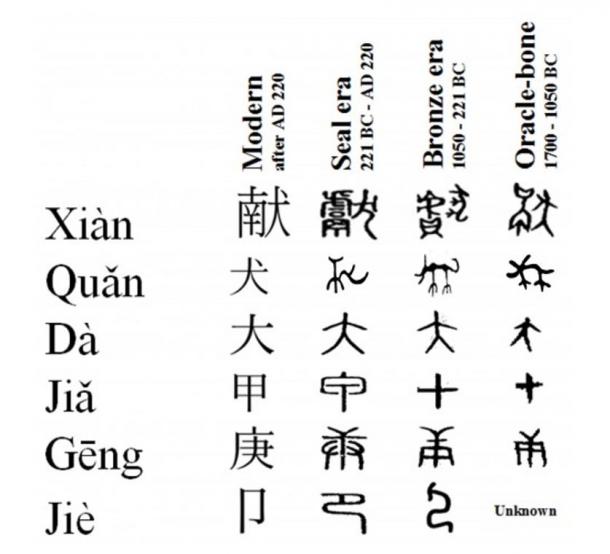

- Understanding Chinese Characters

旅行 (lǚ xíng) means "to travel" or "travels" in Mandarin Chinese. If you want to express your love for travel or if you're trying to explain that you're visiting China for leisurely travel, learning how to pronounce and use the term 旅行 can be helpful.

The pinyin for 旅行 is ► lǚ xíng . The first character is in the 3rd tone while the second character is in the 2nd tone. This can be written as: lu3 xing2.

Chinese Characters

In both traditional and simplified form, 旅行 is written the same way.

The first character 旅 (lǚ) means "trip" or "travel." The second character 行 (xíng) translates to all right; capable; competent; okay; to go; to do; to travel; temporary; to walk; to go; or will do depending on the context.

Sentence Examples

Audio files are marked with ►

► Tā měi nián dōu chū guó lǚxíng yī cì. 他每年都出國旅行一次 他每年都出国旅行一次 He travels abroad once a year. ► Tāmen yào qù ōuzhōu zì zhù lǚxíng. 他們要去歐洲自助旅行 他们要去欧洲自助旅行 They are travelling to Europe by themselves.

Another way to say "travel" in Chinese is 旅游 ( lǚ yóu), which can also mean "tourism."

- Daily Mandarin Lesson: "Happy" in Chinese

- Daily Mandarin Lesson: "What" in Chinese

- Daily Mandarin Lesson: Using "When" in Chinese

- Daily Mandarin Lesson: "Don't Have" in Chinese

- Daily Mandarin Lesson: "Busy" in Chinese

- How to Pronounce and Use 'Where' in Chinese

- How to Say 'Love' in Mandarin Chinese

- Laoshi - Daily Mandarin Lesson

- How to Say "Hello" and Other Greetings in Mandarin Chinese

- Chinese Punctuation Marks

- Chinese Grammar: 以后 Yi Hou

- Mandarin Chinese Pronouns

- Zhidao - Daily Mandarin Lesson

- How to Say "Aunt" in Mandarin Chinese

- What Does Piao Liang Mean in Chinese?

- How to Say Goodbye in Chinese

Searching for Zheng: China's Ming-Era Voyager

A worker inspects a statue of Chinese ancient voyager Zheng He (1371-1435) in preparation for a 2005 exhibition in Shanghai about Zheng's voyages

There is more than historical curiosity behind these new efforts. For centuries after his expeditions, Zheng — a Muslim eunuch — slipped out of public awareness, obscured by the rise and fall of new dynasties. Talk of his exploits was revived briefly at the beginning of the 20th century as the fledgling Chinese republic sought to build a navy in the shadow of imperial Japan. But experts say his place as a patriotic national hero has been truly cemented only in the past two decades, parallel with China's geopolitical rise — and the growth of its significant economic presence in many African nations and countries around the Indian Ocean.

In recent years, though, Beijing has come under criticism for an approach to Africa that is perhaps more bloodless than it is cuddly. China's support of autocratic regimes, from Zimbabwe to Sudan — where Beijing effectively built up an oil industry from scratch — has exposed the Asian giant to accusations of turning a blind eye to human-rights abuses as it goes about securing natural resources and political influence. China has pumped billions of dollars into infrastructure projects throughout the continent, tying up key contracts in resource-rich states like Angola and the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo.

Yet as total annual trade between Africa and China has surpassed $100 billion, Beijing has won its fair share of admirers too, not least among them many Africans whose quality of life has been improved by an influx of cheap Chinese household goods. China has also established a network of "Confucius Institutes" in various African cities to disseminate Chinese culture, while more and more African exchange students are attending Chinese universities. A flotilla of Chinese warships is part of an international operation attempting to curb piracy off the shores of Somalia. "This discussion of Zheng He is being carried out in China at a higher and more expensive level not just to boost the glory of his personal story," says Barry Sautman, a specialist on China-Africa relations at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, "but as a particular cog in China's projection of itself into Africa."

Although the aura of Zheng's expeditions may somehow bolster China's budding soft power, it's unclear what lasting impact the visiting fleets had on medieval Africa. No durable trade ties were left in place. And while stories linger in Kenya's Lamu archipelago of a light-skinned community descended from shipwrecked Chinese sailors, the population there retains no trace of Chinese customs or language. "Not much endured beyond the legend," says Sautman. Indeed, scholars like Wade suggest the voyages themselves were something of an "aberration" in the wider context of Chinese foreign policy in that era, which for centuries was far more focused on staving off the threat of invasion along its fragile land borders.

Moreover, though Beijing plays up the voyages as a triumphant Chinese adventure, the journeys had a distinctly Muslim character. Zheng practiced Islam, as did Ma Huan, the main chronicler aboard the ships. It's likely they were guided to their many ports of call, such as Malacca, India's Malabar coast and Malindi in Kenya, by Muslim pilots of Arab, Indian or African extraction. "They were essentially following maritime routes that had been in use by people in the Indian Ocean for ages," says Wade. Many academics argue that the popular Arab-Persian tale of the Seven Voyages of Sinbad, littered also with snippets of Indian folklore, was derived from the real travels of Zheng He — making the mariner as much a pan-Asian protagonist as a Chinese one.

No matter the many layers of myth surrounding Zheng He, the Chinese are confident they'll uncover a Ming-era wreck near the Lamu archipelago, where bits of Ming ceramic ware have surfaced in the past, and that it will be their legacy that gets burnished when they find it. A team of Chinese archaeologists is expected to commence work in July. It won't be alone — last year, following a visit to Kenya by Chinese President Hu Jintao, a Chinese state petroleum company won concessions to explore more than 100,000 sq km of Kenyan waters for oil. That will be theirs too. Africa, after all, holds more for China these days than just exotic animals.

- Visiting Scholars

Zheng He's Voyages of Discovery

Noted oceanic scientist Jin Wu discusses the 15th century expeditions of the Chinese mariner Zheng He & the celebration of the 600th anniversary of his first voyage

What Zheng He accomplished, Jin Wu declared, must be considered an achievement for all of mankind, not just a Chinese achievement.

Published: Tuesday, April 20, 2004

Center for Chinese Studies 11381 Bunche Hall

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1487

Campus Mail Code: 148703

Tel (310) 825-8683 Fax (310) 206-3555

© 2024 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Terms of Use / Privacy Policy

General Mailing list

Email Us [email protected]

Call us 7305143448, contact us feel free to contact, unraveling the symbolism in chinese characters: a journey into mandarin’s heart.

- Mandarin Speaking

Chinese characters, with their intricate designs and profound meanings, offer a unique window into the cultural and philosophical landscape of China. In this exploration, we will delve into the symbolism and deeper significance of several common Mandarin characters, each telling its own story and revealing facets of Chinese thought and tradition.

今天 (jīntiān): The Essence of “Today”

The Present in a Character: Understanding 今 (jīn) The character 今, combining the human element “人” (rén) with the concept of the present, embodies the idea of the self in the here and now. It’s a testament to the Chinese perspective on the importance of living in the moment, a philosophy deeply rooted in both Daoist and Confucian thought.

Heaven and Earth in 天 (tiān) The character 天, with its roots in “大” (dà), symbolizes the day and the sky. It reflects the Chinese concept of the universe, where the sky or heaven plays a crucial role in shaping human destiny, a belief central to Chinese astrology and Feng Shui.

星期一 (xīngqīyī): The Cycle of Time in “Monday”

The Cosmic Dance: Deciphering 星 (xīng) In 星, the sun radical “日” (rì) highlights the passage of time, an integral aspect of the character. It’s a reminder of the celestial bodies’ influence on the earthly realm, a concept at the heart of traditional Chinese astronomy and calendar systems.

The Lunar Phase: The Role of 期 (qī) With the “月” (yuè) radical, 期 relates to the moon and months, emphasizing the lunar cycle’s role in Chinese timekeeping. This character’s presence in the word for Monday underscores the blend of solar and lunar influences in Chinese reckoning of time.

Unity in 一 (yī)** The simplicity of 一, meaning “one,” signifies the beginning of the workweek. It’s a symbol of unity and starting anew, reflecting the Chinese value of harmony and balance in life’s continuous cycle.

明天 (míngtiān): Illuminating “Tomorrow”

The Duality of 明 (míng) In 明, the combination of “日” (sun) and “月” (moon) represents brightness and the promise of a new day. This character embodies the Chinese philosophical concept of Yin and Yang, where opposites coexist and give rise to each other.

星期二 (xīngqī’èr): “Tuesday” and the Number Two

The Concept of Pairing in 二 (èr) 二, standing for “two,” represents duality and balance. In Chinese culture, the number two often symbolizes harmony and partnership, echoing the Taoist belief in the interdependence of all things.

九 (jiǔ): The Significance of “Nine”

Ancient Roots: The Pictogram of Nine The character 九, resembling a bent arm, is an ancient symbol for the number nine. In Chinese culture, nine is considered a lucky number, associated with longevity and eternity, often appearing in folklore and imperial architecture.

月 (yuè): The Lunar Cycle

The Crescent Moon in 月 The pictogram of 月, resembling the crescent moon, illustrates the lunar cycle’s significance in Chinese culture, from festivals to agriculture. It’s a symbol of change and renewal, deeply embedded in Chinese poetry and art.

八 (bā): The Division of “Eight”

The Concept of Partition in 八 八 represents the idea of division or partition. In Chinese culture, the number eight is seen as particularly auspicious, associated with prosperity and success, as evidenced in the Beijing Olympics’ opening on 08/08/08.

日/号 (rì/hào): Marking the “Date”

The Daily Sun in 日 (rì) 日, symbolizing the sun or day, is used to denote dates, reflecting the solar influence in Chinese timekeeping. It’s a daily reminder of the sun’s vital role in life and culture.

Numbering the Days: The Role of 号 (hào) 号, with its origins in the act of calling out numbers, is used in numbering dates, emphasizing the structured nature of time in Chinese culture.

星期六 (xīngqīliù): “Saturday,” the Sixth Day

The Sequence in 六 (liù) 六, meaning “six,” marks Saturday as the sixth day in the Chinese week. The number six in Chinese culture often symbolizes smoothness and progress, reflecting a desire for steady advancement.

星期日 (xīngqīrì): The Sun’s Day, “Sunday”

日 (rì): The Day of Sun In 星期日, 日 represents the sun, symbolizing Sunday as the day of the sun. This is akin to many cultures where Sunday is seen as a day of rest and reflection, tying back to ancient sun worship.

**Frequently Asked Questions:**

1. How do Chinese characters reflect cultural beliefs?

Chinese characters often incorporate elements that reflect philosophical, astronomical, and cultural beliefs. For instance, the character for “bright” (明) combines symbols for the sun and moon, illustrating the Yin and Yang concept.

2. Why is understanding Chinese characters important?

Understanding these characters provides insight into Chinese culture, history, and philosophy, enhancing communication and cultural appreciation.

3. Can the meaning of a character change over time?

Yes, the interpretation and usage of Chinese characters can evolve, reflecting changes in society and cultural perspectives.

4. How do numbers play a role in Chinese characters?

Numbers in Chinese characters often have cultural significance, such as eight (八) symbolizing prosperity and nine (九) representing longevity.

5. Are there characters that are particularly auspicious or unlucky?

Yes, some characters are considered lucky or unlucky based on their pronunciation or historical associations, like eight (八) for luck and four (四) for misfortune due to its similarity to the word for death (死).

6. How does the lunar cycle influence Chinese characters?

The lunar cycle is significant in many characters, like 月 (moon), reflecting its importance in traditional festivals, agriculture, and timekeeping.

Delving into the world of Chinese characters opens up a rich tapestry of cultural and philosophical insights. Each character is not just a linguistic tool but a gateway to understanding the intricate relationship between language, culture, and thought in Chinese society. As we explore these symbols, we gain a deeper appreciation of the nuanced and profound ways in which the Chinese language mirrors its culture’s heart.

- Immersion Program

- Learn Chinese Online

- Study Abroad in China

- Custom Travel Programs

- Teach in China

- What is CLI?

- Testimonials

- The CLI Center

- Photo Gallery

10 Chinese Travel Phrases For Your Journey to The Middle Kingdom

Learn Chinese in China or on Zoom and gain fluency in Chinese!

Join CLI and learn Chinese with your personal team of Mandarin teachers online or in person at the CLI Center in Guilin , China.

Planning a trip to China and looking for useful Chinese travel phrases? This article provides 10 useful phrases for your upcoming journey to the Middle Kingdom.

If you are new to the Chinese language, we recommend that you first review this interactive pinyin chart and reference it when learning the below Chinese travel phrases.

Table of Contents

1. 好久不见 | Hǎojǐubújiàn | Long-time no see

2. 欢迎光临 | huānyíng guānglín | welcome (to a place), 3. 我是 ... 人 | wǒ shì ... rén | i am [insert nationality], 4. 你会说英语吗?| nǐ huì shuō yīngyǔ ma | can you speak english, 5. ...中文怎么说?| ...zhōngwén zěnme shuō | how do you say ... in chinese, 6. 祝你早日康復 | zhù ní zǎorì kāngfù | get well soon, 7. 这个多少钱 | zhège duōshǎo qián | how much is this, 8. 可以便宜一点吗?| kěyǐ piányí yīdiǎn ma | can you lower the price, 9. 可以加你的微信吗 | kěyǐ jiā nǐ de wéixìn ma | can i add your wechat, 10. 一路平安 | yīlù-píng'ān | bon voyage.

Learn Chinese with CLI

10 Useful Chinese Travel Phrases

We suggest selecting the below phrases that you think will be most useful during your travels in China, then memorize! We also invite you to sign up for one-on-one online Chinese lessons via Skype, Zoom or phone with CLI prior to your upcoming journey.

A classic example of good Chinglish here. This literally translates to “long time no see.” You can use it when you reunite with your long lost Chinese friends.

If your travels take you to Guilin, be sure to check out the city's hidden cave restaurants

You will hear this phrase a lot! This is the common greeting used by restaurants and shops when a customer enters the establishment.

This comes in handy when you first introduce yourself. A nice way to do this is to simply say your name and where you are from:

你好!我叫 Ben,我是美国人 (Nǐhǎo! Wǒ jiào Ben, wǒ shì Měiguórén) Hi! I’m Ben, I’m American.

Here is a list of all the countries in Chinese . Just remember to add 人 (rén) at the end of the country to make it a demonym!

If you really want to ensure that whoever you're introducing yourself to understands your name, you can also check out our lists of Chinese transliterations of common English men's and women's names to discover how to say your name in Chinese .

Although it is always great to try your very best to use Chinese everywhere you go, we all occasionally need a little bit of help. If you are reading this, chances are you are a native English speaker or at the very least have an intermediate level.

You can use this phrase to first ask if someone can speak English. It is a nicer and more polite way to switch to English instead of talking to someone in English right off the bat!

Learning key travel phrases will allow you to interact with locals as you travel through China

If your Chinese friends speak some English, you can also ask for translations of words and phrases whilst still keeping the conversation going in Chinese. For example:

"Delicious" 中文怎么说?| How do you say "delicious" in Chinese?

怎么说 "I am very happy"? | How do you say "I am happy"?

Maybe your friend had a little too much street food the night before and is now not feeling well. You can use this phrase to wish them to get well soon!

Shopping in China is a great opportunity to practice your language skills

Despite its rapid economic development, the cost of living is still very low in China (especially when compared to Western countries). This means a lot of shopping opportunities, so this will be a very useful Chinese travel phrase to learn!

So you know the price — it is now time to test your bargaining skills! One of the great things about Chinese culture is that haggling is normal and almost always part of the shopping experience. If you are exploring the nearby market stalls, you can always ask if the price can be lowered.

If you have Chinese friends or have ever spent any time in China, you will have noticed the importance of WeChat. It is one of China’s major digital communication tools and a great way to keep in touch with your Chinese friends.

Whether you are staying in China for just a few days or even decades, eventually you will part ways with the Middle Kingdom to visit friends and family abroad or just to travel around the continent. You will hear this phrase from Chinese friends and coworkers who want to wish you a safe and pleasant trip.

Traveling in China might seem intimidating at first, but just learning a few basic phrases can really take you far

Need more China travel phrases? Watch the video below for some more ideas for phrases to learn before you start your China travel adventure:

And there you have it! You will be surprised how far these Chinese travel phrases will take you during your journey in China . Don’t worry if you find them difficult at first—persistence is key! With enough patience and practice, you will improve in no time.

Hoping to test out these travel phrases but not sure which part of China you want to visit next? Check out our article on the 10 Best Places to Visit in China and our other travel guides for some ideas. No matter whether you fancy a relaxing beach vacation in Hainan , a walk through Qing Dynasty history in Shenyang , or a canal ride in Suzhou , the Venice of the East, China has a destination for you!

Interested in taking a deeper dive into the Chinese language? We invite you to learn Chinese in China with CLI.

天天学习, 好好向上!

Free 30-minute Trial Lesson

Continue exploring.

- Learn Chinese

- Travel China

Copyright 2024 | Terms & Conditions | FAQ | Learn Chinese in China

- Corrections

The Seven Voyages of Zheng He: When China Ruled the Seas

In the early 15th century, admiral Zheng He embarked on seven epic voyages, spreading the prestige and influence of Ming China across Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and even East Africa.

From 1405 to 1433 CE, the Chinese admiral Zheng He led seven great voyages, unmatched in history. The so-called Treasure Fleet traveled to Southeast Asia and India, sailed across the Indian Ocean to Arabia, and even visited the far-flung shores of East Africa.

Zheng He commanded a veritable floating metropolis consisting of 28, 000 men and over 300 vessels, of which 60 were enormous “treasure ships,” nine-masted behemoths over 120 meters (394 foot) long. Sponsored by the Yongle emperor, the Treasure Fleet was designed to spread the influence of Ming China overseas and establish a tributary system of vassal countries. Although the task was successful, bringing over 30 countries under the nominal control of China, political intrigues at the court, and the Mongol threat on the Empire’s northern border, led to the Treasure Fleet’s destruction. As a result, the Ming emperors shifted their priorities inwards, closing China to the world and leaving the high seas to the European navies of the Age of Exploration.

First Voyage of Zheng He and the Treasure Fleet (1405-1407)

On July 11, 1405, after an offering of prayers to the goddess protector of sailors, Tianfei, the Chinese admiral Zheng He and his Treasure Fleet set out for its maiden voyage. The mighty armada comprised of 317 ships, 62 of them being enormous “treasure ships” ( baochuan ), carrying nearly 28,000 men. The fleet’s first stop was Vietnam, a region recently conquered by the Ming dynasty’s armies. From there, the ships proceeded to Siam (present-day Thailand) and the island of Java before reaching Malacca on the southern tip of the Malaysian peninsula. The local ruler quickly submitted to Ming rule , allowing Zheng He to use Malacca as the main base of operations for his armada. It was the beginning of a renaissance for Malacca, which would become a strategically important port for all shipping between India and Southeast Asia in the following decades.

From Malacca, the fleet continued their voyage eastwards, crossing the Indian Ocean and arriving at the main trading ports on the southwest coast of India, including Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Calicut. The scene of Zheng He’s 300-vessel armada must have been awe-inspiring to the locals. Unsurprisingly, the local rulers accepted China’s nominal control, exchanged gifts, and their ambassadors boarded the ships, which would take them to China. On their return trip, laden with tribute and envoys, the Treasure Fleet confronted the notorious pirate Chen Zuyi in the Strait of Malacca. Zheng He’s ships destroyed the pirate armada and captured their leader, taking him back to China where he was executed.

The Second and Third Voyages: Gunboat Diplomacy (1407-1409 and 1409-1411)

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

The defeat of the pirate armada and the destruction of their base at Palembang secured the Malacca strait and the valuable trade routes linking Southeast Asia and India. Everything was ready for the second voyage of Zheng He in 1407. This time a smaller fleet of 68 ships sailed to Calicut to attend the inauguration of the new king. On the return trip, the fleet visited Siam (present-day Thailand) and the island of Java, where Zheng He got embroiled in a power struggle between two rival rulers. Although the Treasure Fleet’s main task was diplomacy, Zheng He’s massive ships carried heavy guns and were filled with soldiers. Therefore, the admiral could get involved in local politics.

After the armada returned to China in 1409 with holds full of tribute gifts and carrying new envoys, Zheng He immediately departed for another two-year voyage. Like the first two, this expedition also terminated at Calicut. Once again, Zheng He employed gunboat diplomacy when he intervened in Ceylon. Ming troops defeated the locals, captured their king, and brought him back to China. Although the Yongle emperor released the rebel and returned him home, the Chinese backed another regime as a punishment.

Fourth Voyage: The Treasure Fleet in Arabia (1413-1415)

Following a two-year pause, in 1413, the Treasure Fleet set out again. This time, Zheng He ventured beyond the ports of India, leading his armada consisting of 63 ships all the way to the Arabian peninsula. The fleet reached Hormuz, a key link between the maritime and overland Silk roads . The smaller fleet visited Aden, Muscat, and even entered the Red Sea. As these were predominantly Muslim lands, it must have been essential for the Chinese to have specialists in Islamic religion onboard.

Once again, Zheng He got entangled in a local conflict, this time in Samudera, on the north coast of Sumatra. The Ming forces, skilled in the art of war , defeated a usurper who had murdered the king and brought him to China for execution. The Ming had focused all their efforts on diplomacy, but when it failed, they secured their own interests by employing the mighty Treasure Fleet against potential troublemakers.

Fifth and Sixth Voyages: The Treasures of Africa (1416-1419 and 1421-1422)

In 1417, the Treasure fleet left China on its longest voyage to date. After it returned various foreign dignitaries to Southeast Asia, Zheng He crossed the Indian Ocean and sailed to the coast of East Africa. The armada visited several major ports, exchanged gifts, and established diplomatic relations with the local leaders. Among the vast quantities of tribute brought back to China were many exotic animals — lions, leopards, ostriches, rhinoceroses, and giraffes — some of them seen by the Chinese for the first time. The giraffe, in particular, was the most peculiar, and the Chinese identified it as a qilin — a legendary beast that in ancient Confucian texts epitomized virtue and prosperity.

However, while the giraffe could be interpreted as an auspicious sign, the Treasure Fleet was costly to maintain and keep afloat. After Zheng He returned from the sixth expedition in 1422, (which also visited Africa) he discovered that his patron and childhood friend — the Yongle emperor — had died on a military campaign against the Mongols. The new Ming ruler was less welcoming to what many courtiers considered expensive far-flung cruises. In addition, the Mongol threat in the north required vast funds to be diverted for military expenditure and the rebuilding and expansion of the Great Wall . Zheng He retained his position at court, but his naval expeditions were halted for several years. The new emperor lived only a few months and was succeeded by his more adventurous son, the Xuande emperor. Under his leadership, Zheng He would make one last grand voyage.

Seventh Voyage of Zheng He: The End of an Era (1431-1433)

Almost ten years after his last voyage, Zheng He was ready for what would became the Treasure Fleet’s final voyage. The great eunuch admiral was 59 years old, in poor health, but was eager to sail again. So, in the winter of 1431, more than a hundred ships and over 27, 000 men left China, sailing across the Indian Ocean and visiting Arabia and East Africa. The primary purpose of the fleet was to return the foreign envoys home, but it also solidified the tributary relationship between Ming China and over thirty overseas countries.

On the return trip in 1433, Zheng He died and was buried at sea. The death of the great admiral and seafarer reflected the fate of his beloved Treasure Fleet. Faced with a continuous Mongol threat from the north and surrounded by powerful Confucian courtiers who had no love for “wasteful adventures” the emperor ended the naval expeditions for good. He also ordered the dismantlement of the Treasure Fleet. With the eunuch faction defeated, the Confucians sought to erase the memory of Zheng He and his voyages from Chinese history. China was opening a new chapter by closing itself to the outside world. In an ultimate act of irony, Europeans began their voyages only a few decades later. Soon, they dominated the high seas, eventually leading to the European arrival in China as the superior power.

The Mongol Empire Versus China: The Way of War

By Vedran Bileta MA in Late Antique, Byzantine, and Early Modern History, BA in History Vedran is a doctoral researcher, based in Budapest. His main interest is Ancient History, in particular the Late Roman period. When not spending time with the military elites of the Late Roman West, he is sharing his passion for history with those willing to listen. In his free time, Vedran is wargaming and discussing Star Trek.

Frequently Read Together

Admiral Zheng He: China’s Forgotten Master of the High Seas

The Mighty Ming Dynasty in 5 Key Developments

What Was the Silk Road & What Was Traded on It?

Channel Islands Maritime Museum Volunteer Page

Admiral Zheng He and the Chinese Treasure Fleet

Zheng He (also known as Cheng Ho) was born in what is now Jinning County, Kunming City of Yunnan Province in 1371, the fourth year of the Hongwu reign period (1368-1398) of the Ming Dynasty. He was originally surnamed Ma, and later was known as San Bao (Three Treasures).

Raised a Muslim, Zheng He started to study the teachings of Islam at an early age. Both Zheng He’s father and grandfather had made the pilgrimage to Mecca, and so were quite familiar with distant lands. Under the influence of his father and grandfather, the young Zheng He developed a consuming curiosity about the outside world. Zheng He’s father’s direct character and altruistic nature also made a lasting impression on the boy.

He was only eleven years old, was captured by the Chinese Ming Muslim troops and made a eunuch . He was sent to the court of one the emperor ‘s son, Prince Zhu Di . The young eunuch eventually became a trusted adviser and assisted the prince in his insurrection against his nephew the Jianwen Emperor in 1403. For his valor in this war, the eunuch received the name Zheng He. Zheng He served in his court as a Eunuch Grand Director. It was during the Yongle era that Zheng He, with the rank of Chief Envoy carried his first six overseas missions with the Treasure Fleet. Zheng He became a mariner, explorer , diplomat and fleet admiral , who commanded voyages to Southeast Asia , South Asia , the Middle East , and East Africa , collectively referred to as the Voyages of Zheng He or Voyages of Cheng Ho from 1405 to 1433.

In 1425 Yongle’s successor the Hongxi Emperor appointed Zheng He to be Defender of Nanjing. In 1428 the Xuande Emperor ordered him to complete the construction of the magnificent Buddhist nine-storied Da Baoen Temple in Nanjing, and in 1430 appointed him to lead the seventh and final expedition to the “Western Ocean”. It is commonly believed that Zheng He died during the treasure fleet’s last voyage, on the returning trip after the fleet reached Hormuz in 1433.

Expeditions

Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming government sponsored a series of seven naval expeditions. The Yongle emperor designed them to establish a Chinese presence, impose imperial control over trade, impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean basin and extend the empire’s tributary system. It has also been claimed, on the basis of later texts, that the voyages also presented an opportunity to seek out Zhu Yunwen (the previous emperor whom the Yongle emperor had usurped and who was rumored to have fled into exile) – possibly the “largest scale manhunt on water in the history of China”. [10]

Zheng He was placed as the admiral in control of the huge fleet and armed forces that undertook these expeditions. Wang Jinghong was appointed his second in command. Zheng He’s first voyage, which departed July 11, 1405, from Suzhou , consisted of a fleet of 317 ships (other sources say 200 ships) holding almost 28,000 crewmen (each ship housing up to 500 men).

This map is useful to show the extent of the voyages. It is included in the display for you to use with our guests.

Voyages of Zheng He 1405-1433

The ships of Zheng’s armada were as astonishing as its reach. Some accounts claim that the great baochuan , or treasure ships, had nine masts on 400-foot-long (122-meter-long) decks. The largest wooden ships ever built, they dwarfed those of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama. Hundreds of smaller cargo, war, and supply ships bore tens of thousands of men who brought China to a wider world.

1405-1407 317 ships 27,870 men In July the fleet left Nanjing with silks, porcelain, and spices for trade. This well-armed floating city defeated pirates in the Strait of Malacca and reached Sumatra, Ceylon, and India.

1407-1409 The fleet returned foreign ambassadors from Sumatra, India, and elsewhere who had traveled to China on the first voyage. The expeditions firmly established the Ming dynasty’s Indian Ocean trade links.

1409-1411 Although notable for the imperial fleet’s only major foreign land battle, the voyage was also marked by Muslim Zheng’s offering of gifts to a Buddhist temple, one of many examples of his ecumenism.

1413-1415 In this voyage’s wake, the first to travel beyond India and cross the Arabian Sea, an estimated 18 states sent tribute and envoys to China, underscoring the Ming emperor’s influence overseas.

1417-1419 Zheng’s Treasure Fleet visited the Arabian Peninsula and, for the first time, Africa. In Aden the sultan presented exotic gifts such as zebras, lions, and ostriches.

1421-1422 Zheng He’s fleet continued the emperor’s version of shuttle diplomacy, returning ambassadors to their native countries after stays of several years, while bringing other foreign dignitaries back to China.

1431-1433 The last voyage, to Africa’s Swahili coast, with a side trip to Mecca, marked the end of China’s golden age of exploration and of Zheng He’s life. He presumably died en route home and was buried at sea.

Source: National Geographic

Zheng He’s fleets visited Arabia , Brunei , East Africa, India , Malay Archipelago and Thailand , dispensing and receiving goods along the way. Zheng He presented gifts of gold, silver, porcelain and silk ; in return, China received such novelties as ostriches , zebras , camels , ivory and even a giraffe .

Zheng himself wrote of his travels:

We have traversed more than 100,000 li (50,000 kilometers or 30,000 miles) of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare… — Tablet erected by Zheng He, Changle , Fujian , 1432. Louise Levathes

It is important to note that while the scale of Zheng He’s fleet was unprecedented (compared to previous voyages from China to the East Indian Ocean), the routes were not. Sea-based trade links had existed between China and the Arabian Peninsula since the Han Dynasty (there being trade with the Roman Empire at that time.) During the Three Kingdoms , the king of Wu sent a diplomatic mission along the coast of Asia, reaching as far as the Eastern Roman Empire . During the Song Dynasty , there was large scale maritime trade from China reaching as far as the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa . In short, Zheng He’s fleet was following long-established, well-mapped routes.

The Ming admiral and his treasure fleet were not engaged in a voyage of exploration, for one simple reason: the Chinese already knew about the ports and countries around the Indian Ocean. Indeed, both Zheng He’s father and grandfather used the honorific hajji , an indication that they had performed their ritual pilgrimage to Mecca, on the Arabian Peninsula. Zheng He was not sailing off into the unknown.

Likewise, the Ming admiral was not sailing out in search of trade. For one thing, in the fifteenth century all the world coveted Chinese silks and porcelain; China had no need to seek out customers – China’s customers came to them. For another, in the Confucian world order, merchants were considered to be among the lowliest members of society. Confucius saw merchants and other middlemen as parasites, profiting on the work of the farmers and artisans who actually produced trade goods. An imperial fleet would not sully itself with such a lowly matter as trade.

If not trade or new horizons, then, what was Zheng He seeking? The seven voyages of the Treasure Fleet were meant to display Chinese might to all the kingdoms and trade ports of the Indian Ocean world, and to bring back exotic toys and novelties for the emperor. In other words, Zheng He’s enormous junks were intended to shock and awe other Asian principalities into offering tribute to the Ming.

Zheng He generally sought to attain his goals through diplomacy, and his large army awed most would-be enemies into submission. But a contemporary reported that Zheng He “walked like a tiger” and did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary to impress foreign peoples with China’s military might. He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and southeast Asian waters. For example, he would defeat Chen Zuyi, one of the most feared and respected pirate captains, and return him back to China for execution. He also waged a land war against the Kingdom of Kotte in Ceylon , and he made displays of military force when local officials threatened his fleet in Arabia and East Africa. From his fourth voyage, he brought envoys from thirty states that traveled to China and paid their respects at the Ming court.

So then, why did the Ming halt these voyages in 1433, and either burn the great fleet in its moorings or allow it to rot (depending upon the source)?

There were three principle reasons for this decision. First, the Yongle Emperor who sponsored Zheng He’s first six voyages died in 1424. His son, the Hongle Emperor, was much more conservative and Confucianist in his thought, so he ordered the voyages stopped. (There was one last voyage under Yongle’s grandson, Xuande, in 1430-33.)

In addition to the political motivation, the new emperor had a financial motivation. The treasure fleet voyages cost Ming China enormous amounts of money; since they were not trade excursions, the government recovered little of the cost. The Hongle Emperor inherited a treasury that was much emptier than it might have been, if not for his father’s Indian Ocean adventures. China was self-sufficient; it didn’t need anything from the Indian Ocean world, so why send out these huge fleets?

Finally, during the reigns of the Hongle and Xuande Emperors, Ming China faced a growing threat to its land borders in the west. The Mongols and other Central Asian peoples made increasingly bold raids on western China, forcing the Ming rulers to concentrate their attention and their resources on securing the country’s inland borders.

For all of these reasons, Ming China stopped sending out the magnificent Treasure Fleet. However, it is still tempting to muse on the “what if” questions. What if the Chinese had continued to patrol the Indian Ocean? What if Vasco da Gama’s four little Portuguese caravels had run into a stupendous fleet of more than 250 Chinese junks of various sizes, but all of them larger than the Portuguese flagship? How would world history have been different, if Ming China had ruled the waves in 1497-98?

In 1424, the Yongle Emperor died. His successor, the Hongxi Emperor (reigned 1424–1425), decided to stop the voyages during his short reign. Zheng He made one more voyage during the reign of Hongxi’s son Xuande Emperor (reigned 1426–1435), but after that the voyages of the Chinese treasure ship fleets were ended.

Zheng He returned from his voyages to find a new emperor, whose court was uninterested, even hostile, to the continuation of his naval adventures.

After Zheng He’s voyages, the treasure ships were decommissioned, and sat in harbours until they rotted away. Some suggest that Confucian scholars ordered that many of the treasure ships be burned, although exact information on their fate is not known Chinese craftsmen and officials subsequently lost the knowledge for building such large vessels.

Xuande believed his father’s decision to halt the voyages meritorious, and felt “there would be no need to make a detailed description of his grandfather’s sending Zheng He to the Western Oceans.” Given the lack of respect for the voyages it accounts for the Ming “neglect” of Zheng He in official accounts and the scant records of the voyages available for later historians.

China was split between The Mandarin bureaucrats who generally ran the Empire, and the eunuchs who had control within the Imperial Court. The admiral of the Treasure Fleets was Zheng He (jung huh). Zheng He ended up in the Imperial Court. The eunuchs of the Imperial Court functioned as a separate bureaucracy and the Mandarins were fearful of their power. When the Treasure Fleet expeditions to the Indian Ocean turned out to be successes the Mandarins were so afraid that the power of the eunuchs would be enhanced to the point where they would rival the Mandarins in power that they set to stop the Treasure Fleet expeditions. The Mandarins convinced the Emperor that the Treasure Fleet threaten to contaminate the Empire and must be destroyed.

Less than a century after the distruction of Treasure Fleets the Portuguese appeared in the Indian Ocean in their relative small caravels. Soon the Portuguese gained control over the Indian Ocean and traveled on to China, where they acquired Macau, and on to Japan. How much different would world history have been if the Chinese Treasure Fleets had continued around Africa and one day appeared in the harbors of Western Europe.

While the treasure fleet itself was discontinued, Chinese Maritime activities did continue. Trade was important to them. However, piracy and black market activities also became more prominent.

Protection and the Great Wall

State-sponsored Ming naval efforts declined dramatically after Zheng’s voyages. Starting in the early 15th century, China experienced increasing pressure from resurgent Mongolian tribes from the north. In recognition of this threat and possibly to move closer to his family’s historical geographic power base, in 1421 the emperor Yongle moved the capital north from Nanjing to present-day Beijing . From the new capital he could apply greater imperial supervision to the effort to defend the northern borders. At considerable expense, China launched annual military expeditions from Beijing to weaken the Mongolians. The expenditures necessary for these land campaigns directly competed with the funds necessary to continue naval expeditions.

In 1449 Mongolian cavalry ambushed a land expedition personally led by the emperor Zhengtong less than a day’s march from the walls of the capital. In the Battle of Tumu Fortress the Mongolians wiped out the Chinese army and captured the emperor. This battle had two salient effects. First, it demonstrated the clear threat posed by the northern nomads. Second, the Mongols caused a political crisis in China when they released Zhengtong after his half-brother had proclaimed himself the new Jingtai emperor. Not until 1457 did political stability return when Zhengtong recovered the throne. Upon his return to power China abandoned the strategy of annual land expeditions and instead embarked upon a massive and expensive expansion of the Great Wall of China . In this environment, funding for naval expeditions simply did not happen.

Zheng He died during the treasure fleet’s last voyage. Although he has a tomb in China, it is empty: he was, like many great admirals, buried at sea . [20]

Size of the ships

Early 17th century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He’s ships.

Traditional and popular accounts of Zheng He’s voyages have described a great fleet of gigantic ships, far larger than any other wooden ships in history. Some modern scholars consider these descriptions to be exaggerated.

Scholars disagree about the factual accuracy and correct interpretation of accounts of the treasure ships.

The purported dimensions of these ships at 137 m (450 ft) long and 55 m (180 ft wide are at least twice as long as the largest European ships at the end of the sixteenth century and 40% longer and 65% wider than the largest wooden ships known to have been built at any time anywhere else. These dimensions are disputed with some suggesting they were as short as 61–76 m (200–250 feet) and that they used for river rather than ocean travel.

Chinese recordsassert that Zheng He’s fleet sailed as far as East Africa. According to medieval Chinese sources, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships. The fleet included:

- Treasure ships , used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (nine-masted, about 126.73 metres (416 ft) long and 51.84 metres (170 ft) wide), according to later writers [ . This is more or less the size and shape of a football field.

- Equine ships, carrying horses and tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (eight-masted, about 103 m (339 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide).

- Supply ships, containing staple for the crew (seven-masted, about 78 m (257 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide).

- Troop transports , six-masted, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (83 ft) wide.

- Fuchuan warships, five-masted, about 50 m (165 ft) long.

- Patrol boats, eight-oared, about 37 m (120 ft) long.

- Water tankers, with 1 month’s supply of fresh water.

Six more expeditions took place, from 1407 to 1433, with fleets of comparable size.

If the accounts can be taken as factual, Zheng He’s treasure ships were mammoth ships with nine masts, four decks, and were capable of accommodating more than 500 passengers, as well as a massive amount of cargo. Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta both described multi-masted ships carrying 500 to 1000 passengers in their translated accounts. Niccolò Da Conti , a contemporary of Zheng He, was also an eyewitness of ships in Southeast Asia, claiming to have seen 5 masted junks weighing about 2000 tons. There are even some sources that claim some of the treasure ships might have been as long as 600 feet. On the ships were navigators, explorers, sailors, doctors, workers, and soldiers along with the translator and diarist Gong Zhen .

The largest ships in the fleet, the treasure ships described in Chinese chronicles, would have been several times larger than any wooden ship ever recorded in history, surpassing l’Orient (65 m/213.3 ft long) which was built in the late 18th century. The first ships to attain 126 m (413.4 ft) long were 19th century steamers with iron hulls. Some scholars argue that it is highly unlikely that Zheng He’s ship was 450 feet (137.2 m) in length, some estimating that they were 390–408 feet (118.9–124.4 m) long and 160–166 feet (48.8–50.6 m) wide instead while others put them as small as 200–250 feet (61.0–76.2 m) in length, which would make them smaller than the equine, supply, and troop ships in the fleet.

One explanation for the seemingly inefficient size of these colossal ships was that the largest 44 Zhang treasure ships were merely used by the Emperor and imperial bureaucrats to travel along the Yangtze for court business, including reviewing Zheng He’s expedition fleet. The Yangtze River, with its calmer waters, may have been navigable by these treasure ships. Zheng He, a court eunuch, would not have had the privilege in rank to command the largest of these ships, seaworthy or not. The main ships of Zheng He’s fleet were instead 6 masted 2000-liao ships.

Accounts of medieval travelers

The characteristics of the Chinese ships of the period are described by Western travelers to the East, such as Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo. According to Ibn Battuta, who visited China in 1347:

We stopped in the port of Calicut, in which there were at the time thirteen Chinese vessels, and disembarked. China Sea traveling is done in Chinese ships only, so we shall describe their arrangements. The Chinese vessels are of three kinds; large ships called chunks (junks), middle sized ones called zaws ( dhows ) and the small ones kakams . The large ships have anything from twelve down to three sails, which are made of bamboo rods plaited into mats. They are never lowered, but turned according to the direction of the wind; at anchor they are left floating in the wind.

Three smaller ones, the “half”, the “third” and the “quarter”, accompany each large vessel. These vessels are built in the towns of Zaytun and Sin-Kalan . The vessel has four decks and contains rooms, cabins, and saloons for merchants; a cabin has chambers and a lavatory, and can be locked by its occupants.

This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three ells in length. When these walls have thus been built the lower deck is fitted in and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished.

– Ibn Battuta

Zheng He Timeline:

- June 11, 1360. Zhu Di born, fourth son of future Ming Dynasty founder.

- Jan. 23, 1368. Ming Dynasty founded.

- 1371. Zheng He born to Hui Muslim family in Yunnan, under birth name of Ma He.

- 1380. Zhu Di made Prince of Yan, sent to Beijing.

- 1381. Ming forces conquer Yunnan, kill Ma He’s father and capture boy.

- 1384. Ma He is castrated, sent to serve as a eunuch in Prince of Yan’s household.

- June 30, 1398-July 13, 1402. Reign of Jianwen Emperor.

- August 1399. Prince of Yan rebels against nephew, the Jianwen Emperor.

- 1399. Eunuch Ma He leads Prince of Yan’s forces to victory at Zheng Dike, Beijing.

- July 1402. Prince of Yan captures Nanjing; Jianwen Emperor (probably) dies in palace fire.

- July 17, 1402. Prince of Yan, Zhu Di, becomes Yongle Emperor .

- 1402-1405. Ma He serves as Director of Palace Servants, highest eunuch post.

- Feb. 11, 1404. Yongle Emperor awards Ma He honorific name “Zheng He.”

- July 11, 1405-Oct. 2 1407. First voyage of Treasure Fleet, led by Admiral Zheng He, to Calicut, India.

- 1407. Treasure Fleet defeats pirate Chen Zuyi at Straights of Malacca; Zheng He takes pirates to Nanjing for execution.

- 1407-1409. Second Voyage of Treasure Fleet, again to Calicut.

- 1409-1410. Yongle Emperor and Ming army battle Mongols.

- 1409-July 6, 1411. Third Voyage of Treasure Fleet to Calicut. Zheng He intervenes in Ceylon succession dispute.

- Dec. 18, 1412-August 12, 1415. Fourth Voyage of the Treasure Fleet to Hormuz. Capture of the pretender Sekandar in Semudera (Sumatra) on return trip.

- 1413-1416. Yongle Emperor’s second campaign against the Mongols.

- May 16, 1417. Yongle Emperor enters new capital city at Beijing, leaves Nanjing forever.

- 1417-August 8, 1419. Fifth Voyage of the Treasure Fleet, to Arabia and East Africa.

- 1421-Sept. 3, 1422. Sixth Voyage of the Treasure Fleet, to East Africa again.

- 1422-1424. Series of campaigns against the Mongols, led by Yongle Emperor.

- Aug. 12, 1424. Yongle Emperor dies of possible stroke while fighting Mongols.

- Sept. 7, 1424. Zhu Gaozhi, eldest son of Yongle Emperor, becomes Hongxi Emperor. Orders stop to Treasure Fleet voyages.

- May 29, 1425. Hongxi Emperor dies. Son Zhu Zhanji becomes Xuande Emperor.

- June 29, 1429. Xuande Emperor orders Zheng He to take one more voyage.

- 1430-1433. Seventh and final Voyage of the Treasure Fleet, to Arabia and East Africa.

- 1433, exact date unknown. Zheng He dies and is buried at sea on the return leg of the final voyage.

- 1433-1436. Zheng He’s companions Ma Huan, Gong Zhen and Fei Xin publish accounts of their travels.

Another source you may want to investigate is the modern study of the Zheng He and the treasure ship by contemporary historians.

- http://www.international.ucla.edu/article.asp?parentid=10387

There is also much discussion about the possibility that China discovered America before Columbus.

- · 1421: The Year China Discovered the World – Gavin Menzies

- http://www.chinesediscoveramerica.com/

- http://history.howstuffworks.com/european-history/chinese-beat-columbus.htm

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4609074.stm

You can see that this historical period is still of great interest.

Characters in this word:

*** the simplified equivalent of this word has not been verified by any editors, so it may not be fully accurate ***.

- a large version of the word in a traditional script font which you may need to install

- the meaning of the word, typed in by our volunteer editors

- guidelines on whether the word can only be used in Spoken Cantonese etc (if nothing is present the word may be used in both Cantonese and Mandarin)

- our arbitrarily assigned difficulty level

- a smaller version of the character in a computerised, printed font

- a list of each of the characters for the word, showing jyutping and meaning (if our dictionary contains that character)

Looking for Something?

Chinese basic words and phrases for travel.

If You Like It, Share It!

Table of Contents

Why You Need to Know Chinese Basic Words and Phrases

If you’re going to travel in China, then you really need to learn a few common Chinese phrases. I speak from experience when I say that traveling in China without knowing at least some basic Chinese words and sentences is incredibly frustrating.

Even if you’ve traveled in dozens of other countries without speaking the local language, the language barrier you’ll come up against in China will be unlike anything you’ve experienced before.

But the good news is, learning just the very basics of Chinese will really go a long way. And who knows, you may fall in love with the language like I did and want to keep learning!

When I first started learning basic Mandarin in 2009, I saw it purely as a survival tactic. Nick and I were working in Guangzhou, China off and on for a few weeks, and in between work stints we had lots of time to explore the country.

For our first short trip in China, we chose the remote Western Chinese province of Gansu . This was not the wisest choice we could have made. Fascinating as it was to explore such an off the beaten track part of China, we got ourselves into all kinds of trouble.

We even wandered into an out of bounds area and found ourselves surrounded by a S.W.A.T. team of half a dozen police officers! Of course, we could have avoided all of this if we had just known some Mandarin basics.

If you memorize just a few Chinese words and phrases from the list below, like “please”, “thank you”, “sorry” and the very useful “I don’t understand”, this will already make your trip a lot smoother.

And for the phrases you can’t remember, just keep them on hand so you can show them to people as needed.

Should I Learn Simplified or Traditional Chinese Characters?

In the list below, each phrase is written in both simplified Chinese and traditional Chinese characters. So, which one should you show to locals when trying to communicate with them? Well, it depends on where you are traveling.

The simplified Chinese script is used throughout mainland China and also in Singapore. Traditional Chinese characters, on the other hand, are used in Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

In Malaysia , schools switched to teaching simplified Chinese in the 1980s, but most Chinese speakers there are able to read both sets of characters without much difficulty.

Chinese-speaking communities in other parts of the world are probably more likely to use traditional characters, but this may be changing over time with new waves of immigration. If you’re not sure, you can just point to both.

Chinese, Mandarin, Cantonese … What’s the Difference?

When people find out that I’m studying Chinese, they often ask me if I’m learning Mandarin or Cantonese. The answer is, I’m learning Mandarin, but those are not the only two forms of spoken Chinese.

While Mandarin is the lingua franca in China, there are actually several hundred different Chinese languages! And that’s just the “Sinitic” languages spoken by the majority ethnic group, the Han. There are also about 300 minority languages spoken by minority groups in places like Tibet and Yunnan .

But even the Chinese languages are as different from each other as English is from German, or as Spanish is from French.

However, these differences only show up in spoken form. The written form of Chinese, which is based on Mandarin, is standardized throughout the country.

In fact, it’s pretty common for Chinese people who speak different languages to resort to writing things down in order to communicate with each other. So, if you point to one of the written phrases in this list to get your point across, this won’t be seen as weird.

Although, it’s more fun to try pronouncing them yourself! Just one word of caution, though. Don’t try to pronounce Mandarin words or phrases without knowing something about tones first.

Mandarin Pronunciation and Tones

Mandarin is a tonal language, and you really do need to get the tones right if you want to be understood.

If you say the syllable “ma” with a rising tone (“ma?”) instead of a falling tone (“ma!”), for example, you’ll end up saying a completely different word.

This is where pinyin comes in handy. Pinyin is a system for romanizing Chinese, which means writing Chinese words phonetically using the Latin alphabet.

A tone marker over is written over each syllable to indicate whether it’s pronounced as a first tone (mā), second tone (má), third tone (mǎ), fourth tone (mà) or neutral tone (ma).

For each of the basic Mandarin words and phrases in the list below, you’ll find the pinyin with tone markers next to it in the right-hand column.

Of course, you still need to know what the different tones sound like in order to pronounce them properly.

More Resources for Learning Basic Mandarin

It would be silly of me to try to teach you tone pronunciation in a written article, so instead I’ll direct you over to ChinesePod , one of my favorite resources for learning Chinese.

The folks there have put together a great video course called Say It Right that’s all about Chinese tones and pronunciation. It’s totally free; you just need to sign up for a free account.

And check out some of their Newbie lessons while you are there, which are really engaging and fun. I started out by castually listening to a few of their Newbie lessons back in 2009 and ended up sticking with it all the way to the Advanced level.

If you’re not interested in learning Chinese to an advanced level and just want to have some common Chinese phrases at your fingertips, then uTalk is a great option .

Inside the uTalk smartphone app, you’ll find hundreds of useful Chinese words and phrases on all kinds of topics ranging from asking directions to watching a football match.

I’ve already included in the list below the Chinese phrases that I have found most useful when traveling. These start with most common Chinese words and phrases, like how to say “thank you” in Chinese, how to say “how are you” in Chinese, and how to say “where are you from?” in Chinese.

In addition, the list below also covers the main topics of eating out in restaurants, using public transport and checking in and out of accommation. I’ve limited the list to about 100 words and phrases to keep it a manageable size for a blog post.

But if you’d like to have a more extensive list of Chinese phrases in English translation, covering dozens of other topics, then do check out uTalk.

Even if you don’t plan to actually learn all the phrases in the app, it also works as a really handy electronic phrasebook. Just type in a word such as “train”, and you’ll instantly see all the revelant phrases, like “the train is canceled”, “the train is delayed” and “when is the last train?”.

uTalk has some really affordable monthly subscription plans, and you can even get 20% off through this link . This discount is valid for any of the 140+ languages uTalk offers, not just Chinese. Oh, and they do offer Cantonese and Shanghainese as well as Mandarin!

Chinese Travel Phrases

And now here’s that list of Chinese travel phrases I promised you. I created this list based on my many years of experience studying Chinese, and I also checked it with a native speaker. So you can be sure that everything here is correct and sounds natural in Chinese.

Most Common Chinese Words and Phrases

Chinese restaurant phrases.

These phrases will definitely come in handy when ordering food in a restaurant in Chinese. This list includes phrases for explaining food allergies and for ordering vegetarian or vegan food, which you won’t find in most phrasebooks.

Be aware that the Chinese word for “vegan” is commonly used in Taiwan (where veganism is very popular) but is unlikely to be understood in China. There are actually two words for “vegan” in Taiwan. The one I’ve used below is “全素” or “full vegetarian”, but you could also say “純素” or “pure vegetarian”.

Either way, in China you will probably need to explain what that means.

But don’t worry, I’ve also included in the list phrases like “I don’t eat any animal products” and “I don’t eat meat, fish, eggs or dairy products” to help you do just that.

Chinese Transportation Phrases

Chinese Accommodation Phrases

Want to learn even more Chinese words and phrases? And learn how to pronounce them correctly?

Remember to check out ChinesePod and uTalk . These are the top two resources I recommend for people traveling to China or any other destination where Chinese is spoken. 一路平安 (Bon Voyage)!

About Wendy Werneth

This post is really excellent and super helpful, Wendy! FYI in Taiwan, Chinese speakers are far more likely to say 早安 than 早上好 for “good morning”, 國語 (or a little less commonly 中文) rather than 漢語 for “Chinese”, and 這裡吃 rather than 在這吃 for eating here. This is in my personal experience, and confirmed by my Taiwanese wife. The expressions you’ve listed for those are correct too, but just less common in Taiwan.

Great, that’s really helpful Nick. Thanks for your input! I tried to make the post as general as possible by including both simplified and traditional characters, but it’s true that the phrases I’ve included are based on usage in China. So I’m glad to hear the Taiwanese perspective!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and site URL in my browser for next time I post a comment.

Who is the Nomadic Vegan?

Hi, I'm Wendy. I'm an intrepid traveler, vegan foodie and animal lover. I travel all over the world (117 countries and counting!) uncovering vegan treasures to show you how you can be vegan anywhere. Read more on my About page .

Let's Be Friends!

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Travel China Cheaper

Travel China the smart way! Expert tips and travel advice for China tourists and expats.

PLANNING A TRIP TO CHINA? Start Here

Chinese Idioms: 21 Useful Chengyu (in Chinese and English)

February 26, 2024 By Josh Summers

The ability to recite “chengyu”, or Chinese idioms, is often a litmus test in China to show not only your language abilities but even your intellect. Learn all you need to know about Chinese sayings along with 21 useful chengyu that are sure to impress your Chinese friends.

Before I share with you 21 common chengyu, you may be wondering…

What is Chinese Chengyu?

Chengyu, or 成语 (Chéngyǔ), is simply a Chinese idiom. Chengyu typically are made up of four Chinese characters and often allude to a story in Chinese history and legends.

Chinese people take pride in both their language and history, so seeing that chengyu tie both of these together, it comes as no surprise that Chinese idioms are super important in China’s popular culture.

When in China, you’re always going to encounter locals speaking chengyu, whether it be when giving a toast, teaching a concept in school, giving friendly advice, or just in simple conversation.

So now that you understand the cultural importance of chengyu, let’s cover 21 common chengyu and what they mean in English.

21 Brilliant Chinese Idioms Worth Memorizing (aka chengyu)

Below are 21 Chinese idioms that are super useful and worth committing to memory as you’re learning the Chinese language.

I’ve provided the Chinese characters, the pinyin, and a short explanation of how each chengyu is used to help learn each one.

马马虎虎 / mǎmǎhūhū – Just so-so or a careless person

This is usually the first chengyu anyone taking a course in Chinese will learn because it’s really easy to use.

When someone asks you questions like, “How was your meal?” or, “How was the movie?”, you can simply respond with “mǎmǎhūhū” if it was nothing great.

入乡随俗 / rùxiāngsuísú – When in Rome, do as the Romans do

When visiting China, you’re bound to deal with plenty of culture shock. When I first visited China in 2010, getting used to the food was my biggest cultural adjustment.

To help me adjust, locals often used this idiom on its own as an encouragement encouragement. You’re likely to hear it as well should you encounter any strong culture shock while in China.

一石二鸟 / yīshí’èrniǎo – To kill two birds with one stone

Almost any idiom in English can also be expressed in Chinese like this one.

To use 一石二鸟 / yīshí’èrniǎo, you can start by introducing your master plan or comment on someone else’s plan by saying, “这样很好。可以一石二鸟。/ Zhèyàng hěn hǎo. Kěyǐ yīshí’èrniǎo” or, “This is really good. You can kill two birds with one stone.”

一路平安 / yīlù píng’ān – Have a safe and pleasant journey!

You can use this phrase when saying goodbye to someone that is leaving for a trip or vacation. You’ll likely hear Chinese say this to you as you check out of a hotel and board a train or plane.

Some Chinese may also say, “一路顺风 / yīlù shùnfēng,” which is similar to the phrase “Bon voyage!”

人山人海 / rénshānrénhǎi – Sea of people

Chinese aren’t shy about saying there are tons of people in China. So you’re likely to hear this chengyu in crowded places in China.

You can always use the chengyu on its own to describe a crowded situation, but if you want to say a full sentence, you can use this model:

place + preposition + 人山人海.

For example, “长城上人山人海! / chángchéng shàng rénshānrénhǎi!” means, it’s insanely crowded on the Great Wall!

说曹操,曹操就到 / Shuō cáocāo, cáocāo jiù dào – Speak of the devil and he shall appear

While a bit of a tongue twister, this chengyu is quite common and easy to use given it has an English equivalent that most of us have heard before.

Simply say this phrase when you are talking about someone and they suddenly appear out of nowhere.

叶公好龙 / yègōnghàolóng – To pretend to like something when actually you hate or fear it

How many times in your life have you pretended to like something when you actually hate it?

While in China, my local friends always wanted to eat duck feet together and I always went along with it to not spoil the fun.

When one of my friends finally realized I hated duck feet, she said, “你吃鸭抓抓就是叶公好龙,只在嘴上说说,并不真的喜欢。以后我们就吃披萨。怎么样?/ Nǐ chī yā zhuā zhuā jiùshì yègōnghàolóng, zhǐ zài zuǐ shàng shuō shuō, bìng bù zhēn de xǐhuān. Yǐhòu wǒmen jiù chī pīsà. Zěnme yàng?”.

In English, she meant:

“You say you like duck feet when you actually don’t. How about we just eat pizza from here on?”

民以食为天 / mín yǐ shí wéi tiān – People view food as their heaven

This five-character chengyu is a classical way of saying there is nothing more important than food.

You can use this in discussions on health and fitness to describe the importance of food or for more serious conversations such as the importance of food in solving world hunger.

幸灾乐祸 / xìngzāilèhuò – To gloat about someone else’s misfortune

Have you ever fallen down and instead of getting a helping hand from your friend, they laugh instead and make you feel even more embarrassed?

In these types of situations, should you encounter them in China, you can say, “不要幸灾乐祸!/ bùyào xìngzāilèhuò!” or, “Don’t gloat on my misfortune!”

Trust me…they’ll be impressed when you do 🙂

自食其果 / zìshíqíguǒ – To reap what you sow

This Chinese idiom can be used on its own and is similar to how we use the phrase “You reap what you sow” in English.

Whenever you say or hear about someone suffering the negative consequences of their own doing, “自食其果” is an appropriate phrase to describe the situation.

百年好合 / bǎinián hǎo hé – Live a long and happy life together

This is the perfect idiom to use with someone who just got married. What it exactly translates to is “100 years together.”

So if you’re ever lucky enough to attend a Chinese wedding, be sure to say this to the newlywed couple. And also don’t forget to bring a red envelope with you!

恭喜发财 / gōngxǐ fācái – Have a prosperous New Year!

One thing you’ll quickly notice about Chinese during each Spring Festival is they are very well-spoken while giving toasts. You’ll also likely be on the receiving end of a toast yourself should you attend a Chinese New Year celebration, so you can use this common idiom in your response.

Otherwise, things may get awkward when your host wishes you good fortune and health and you have nothing to wish them in return!

岁岁平安 / suì suì píng’ān – May you have peace all year round!

This is another Chinese New Year greeting, but you can use this idiom whenever something like a mirror or glass shatters. Like in Western culture, shattering a mirror in China is a bringer of bad luck. But saying this idiom after breaking a mirror will reverse the bad luck!

Why is this the case?

Because the word to shatter in Chinese (碎 / suì) has the same sound as 岁 / suì from this idiom, which has a positive meaning. So keep this idiom in mind should you ever break a mirror or anything that can shatter.

鹤立鸡群 / hèlìjīqún – A crane standing in a flock of chicken (i.e. someone who is outstanding)

As the definition suggests, you can use this Chinese idiom to describe someone that is truly outstanding from others. You can use it to either give encouragement to someone that is talented or praise someone on a job well done.

For example, “你太棒了, 鹤立鸡群!没有人能比得上你!/ nǐ tài bàngle, hèlìjīqún! Méiyǒu rén néng bǐ dé shàng nǐ!”

This sentence means, “You’re so awesome. Just like a crane standing among chickens. No one can match you!”

羊入虎口 / yáng rù hǔkǒu – To tread on dangerous ground

This saying is useful when advising friends not to do something as the result could invite punishment or danger. Let’s say for example your classmate forgot to do their Chinese homework and want to copy yours.

Out of concern that your teacher will catch you, you can say, “不行!你这样可能是羊入虎口。/ Bùxíng! Nǐ zhèyàng kěnéng shì yáng rù hǔkǒu.” or, “No! Doing this can get us into trouble.”

不可思议 / bùkěsīyì – Inconceivable

If something were to ever strike you as incredible to the point where you cannot fathom or speak about it, you can use this idiom to express that emotion.

If you have ever seen the Princess Bride , the Sicilian is constantly surprised by the skills of the Man in Black in his quest to save Princess Buttercup and says nothing but, “Inconceivable!”

If the movie were translated into Chinese, instead of inconceivable, the Sicilian would say, “不可思议!”

骑驴找驴 / qí lǘ zhǎo lǘ – To look for something that’s right under your nose

This is one of my favorite sayings! It’s most similar to the Western expression, “to be right under one’s nose.”

You can use this when you are someone else is looking for something in plain sight.

Say, for example, I’m looking for my glasses when they are on my forehead, you can respond by saying, “眼镜在你额头上,真是骑驴找驴!/ yǎnjìng zài nǐ étóu shàng, zhēnshi qí lǘ zhǎo lǘ!”

挑拨离间 / tiǎobō líjiàn – To drive a wedge between people.

No one likes it when someone drives a wedge between two friends.

If you ever have a friend that gets angry at you over a rumor started by someone, you can tell your friend, “不要相信他。他想在我们中间挑拨离间!/ Bùyào xiāngxìn tā. Tā xiǎng zài wǒmen zhōngjiān tiǎobō líjiàn!” or, “Don’t trust him. He only wants to drive a wedge between us!”

画蛇添足 / huàshétiānzú – To draw legs on a snake (i.e. to overdo something)

This Chinese saying is perfect for artists or chefs that in the effort to improve something that is already perfect add something that makes it worse.

Whenever you’re in a situation like drawing a picture, adding ingredients to a meal, or deciding whether to go out with a scarf or not to be more fashionable and the additional effort is not needed at all, you can use this idiom to express, “Don’t overdo it!” or, “别画蛇添足!/ bié huàshétiānzú!”

三个臭皮匠,顶个诸葛亮 – The wisdom of the masses exceeds that of any individual or many minds are better than one.

Okay now for a hard one that will really impress Chinese locals! This chengyu originates from a mastermind named Zhuge Liang from the Warring States Period.

While I won’t go into the backstory here, the idiom states that ordinary people in groups can outsmart a mastermind.

You can use this when someone encounters a really difficult problem and you offer help to come to a solution. Two minds are better than one right?

有朋自远方来,不亦乐乎 / yǒupéng zì yuǎnfāng lái, bù yì lè hū – It’s always great to see old friends

No list of useful Chinese idioms would be complete without a quote from Confucius!

While this one is a bit tough, it’s really useful for when you see old friends. If you’ve lived in China for several years like me, you and your close friends have probably moved on to live in another Chinese city or moved back home entirely.

When you see each other again, you can always use this idiom in place of “好久不见 / hǎojiǔ bùjiàn,” which conveys less enthusiasm and feeling for a happy reunion.

Wow, after looking over that list, that’s a lot of chengyu!

To help you memorize each of these idioms, I’d focus on learning the meaning and structure behind each character as well as researching the story behind each idiom.

This way you’re much more likely to be able to recall each of them from memory.

Frequently Asked Questions about Chengyu

Below are some of the most frequently asked questions related to Chinese idioms.

A chengyu is a Chinese idiom made up of four characters. There are exceptions where there are more characters, but 4 characters is the norm.

In short, there are thousands of chengyu you can learn. So obviously it’s impossible to learn them all. It’s best to find the most common idioms and try to learn the ones you can use in daily life.

While having some knowledge of Chinese idioms is helpful, it’s not essential. I would focus on the basics in Mandarin until you are an intermediate or advanced speaker. The primary benefit of learning idioms, apart from improving your Chinese, is enriching your knowledge of Chinese history.

As a fluent Mandarin speaker that has only memorized a handful of these idioms, I would focus more on memorizing general vocabulary. You should think of knowing chengyu as a “nice to have” skill whereas expanding your vocabulary is essential.