What Is on Voyager’s Golden Record?

From a whale song to a kiss, the time capsule sent into space in 1977 had some interesting contents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Voyager-records-631.jpg)

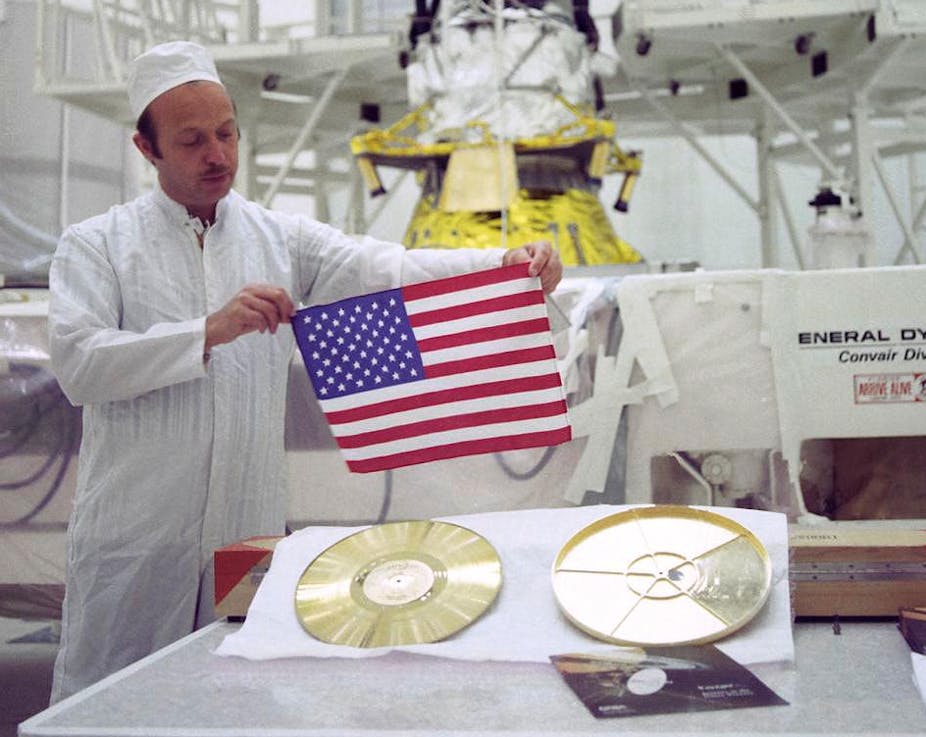

“I thought it was a brilliant idea from the beginning,” says Timothy Ferris. Produce a phonograph record containing the sounds and images of humankind and fling it out into the solar system.

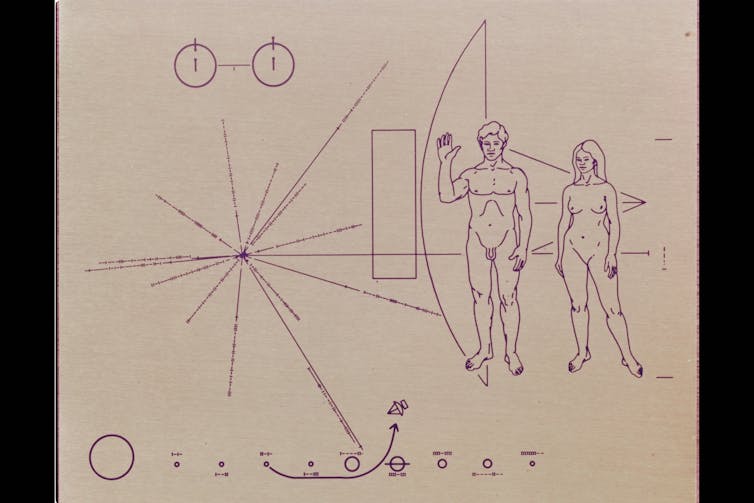

By the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake already had some experience with sending messages out into space. They had created two gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were affixed to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft. Linda Salzman Sagan, an artist and Carl’s wife, etched an illustration onto them of a nude man and woman with an indication of the time and location of our civilization.

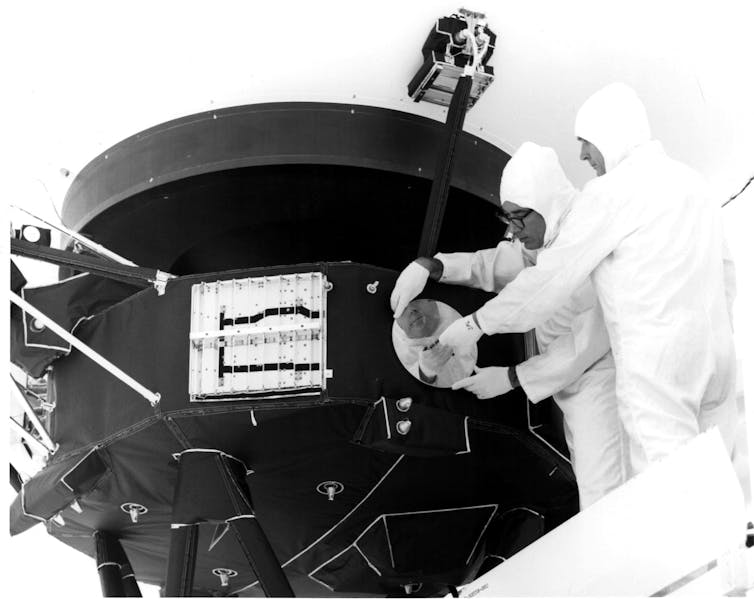

The “Golden Record” would be an upgrade to Pioneer’s plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and transmit much more information about life on Earth should extraterrestrials find it.

NASA approved the idea. So then it became a question of what should be on the record. What are humanity’s greatest hits? Curating the record’s contents was a gargantuan task, and one that fell to a team including the Sagans, Drake, author Ann Druyan, artist Jon Lomberg and Ferris, an esteemed science writer who was a friend of Sagan’s and a contributing editor to Rolling Stone .

The exercise, says Ferris, involved a considerable number of presuppositions about what aliens want to know about us and how they might interpret our selections. “I found myself increasingly playing the role of extraterrestrial,” recounts Lomberg in Murmurs of Earth , a 1978 book on the making of the record. When considering photographs to include, the panel was careful to try to eliminate those that could be misconstrued. Though war is a reality of human existence, images of it might send an aggressive message when the record was intended as a friendly gesture. The team veered from politics and religion in its efforts to be as inclusive as possible given a limited amount of space.

Over the course of ten months, a solid outline emerged. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. As producer of the record, Ferris was involved in each of its sections in some way. But his largest role was in selecting the musical tracks. “There are a thousand worthy pieces of music in the world for every one that is on the record,” says Ferris. I imagine the same could be said for the photographs and snippets of sounds.

The following is a selection of items on the record:

Silhouette of a Male and a Pregnant Female

The team felt it was important to convey information about human anatomy and culled diagrams from the 1978 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. To explain reproduction, NASA approved a drawing of the human sex organs and images chronicling conception to birth. Photographer Wayne F. Miller’s famous photograph of his son’s birth, featured in Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition, was used to depict childbirth. But as Lomberg notes in Murmurs of Earth , NASA vetoed a nude photograph of “a man and a pregnant woman quite unerotically holding hands.” The Golden Record experts and NASA struck a compromise that was less compromising— silhouettes of the two figures and the fetus positioned within the woman’s womb.

DNA Structure

At the risk of providing extraterrestrials, whose genetic material might well also be stored in DNA, with information they already knew, the experts mapped out DNA’s complex structure in a series of illustrations.

Demonstration of Eating, Licking and Drinking

When producers had trouble locating a specific image in picture libraries maintained by the National Geographic Society, the United Nations, NASA and Sports Illustrated , they composed their own. To show a mouth’s functions, for instance, they staged an odd but informative photograph of a woman licking an ice-cream cone, a man taking a bite out of a sandwich and a man drinking water cascading from a jug.

Olympic Sprinters

Images were selected for the record based not on aesthetics but on the amount of information they conveyed and the clarity with which they did so. It might seem strange, given the constraints on space, that a photograph of Olympic sprinters racing on a track made the cut. But the photograph shows various races of humans, the musculature of the human leg and a form of both competition and entertainment.

Photographs of huts, houses and cityscapes give an overview of the types of buildings seen on Earth. The Taj Mahal was chosen as an example of the more impressive architecture. The majestic mausoleum prevailed over cathedrals, Mayan pyramids and other structures in part because Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in honor of his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and not a god.

Golden Gate Bridge

Three-quarters of the record was devoted to music, so visual art was less of a priority. A couple of photographs by the legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams were selected, however, for the details captured within their frames. One, of the Golden Gate Bridge from nearby Baker Beach, was thought to clearly show how a suspension bridge connected two pieces of land separated by water. The hum of an automobile was included in the record’s sound montage, but the producers were not able to overlay the sounds and images.

A Page from a Book

An excerpt from a book would give extraterrestrials a glimpse of our written language, but deciding on a book and then a single page within that book was a massive task. For inspiration, Lomberg perused rare books, including a first-folio Shakespeare, an elaborate edition of Chaucer from the Renaissance and a centuries-old copy of Euclid’s Elements (on geometry), at the Cornell University Library. Ultimately, he took MIT astrophysicist Philip Morrison’s suggestion: a page from Sir Isaac Newton’s System of the World , where the means of launching an object into orbit is described for the very first time.

Greeting from Nick Sagan

To keep with the spirit of the project, says Ferris, the wordings of the 55 greetings were left up to the speakers of the languages. In Burmese , the message was a simple, “Are you well?” In Indonesian , it was, “Good night ladies and gentlemen. Goodbye and see you next time.” A woman speaking the Chinese dialect of Amoy uttered a welcoming, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” It is interesting to note that the final greeting, in English , came from then-6-year-old Nick Sagan, son of Carl and Linda Salzman Sagan. He said, “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

Whale Greeting

Biologist Roger Payne provided a whale song (“the most beautiful whale greeting,” he said, and “the one that should last forever”) captured with hydrophones off the coast of Bermuda in 1970. Thinking that perhaps the whale song might make more sense to aliens than to humans, Ferris wanted to include more than a slice and so mixed some of the song behind the greetings in different languages. “That strikes some people as hilarious, but from a bandwidth standpoint, it worked quite well,” says Ferris. “It doesn’t interfere with the greetings, and if you are interested in the whale song, you can extract it.”

Reportedly, the trickiest sound to record was a kiss . Some were too quiet, others too loud, and at least one was too disingenuous for the team’s liking. Music producer Jimmy Iovine kissed his arm. In the end, the kiss that landed on the record was actually one that Ferris planted on Ann Druyan’s cheek.

Druyan had the idea to record a person’s brain waves, so that should extraterrestrials millions of years into the future have the technology, they could decode the individual’s thoughts. She was the guinea pig. In an hour-long session hooked to an EEG at New York University Medical Center, Druyan meditated on a series of prepared thoughts. In Murmurs of Earth , she admits that “a couple of irrepressible facts of my own life” slipped in. She and Carl Sagan had gotten engaged just days before, so a love story may very well be documented in her neurological signs. Compressed into a minute-long segment, the brain waves sound, writes Druyan, like a “string of exploding firecrackers.”

Georgian Chorus—“Tchakrulo”

The team discovered a beautiful recording of “Tchakrulo” by Radio Moscow and wanted to include it, particularly since Georgians are often credited with introducing polyphony, or music with two or more independent melodies, to the Western world. But before the team members signed off on the tune, they had the lyrics translated. “It was an old song, and for all we knew could have celebrated bear-baiting,” wrote Ferris in Murmurs of Earth . Sandro Baratheli, a Georgian speaker from Queens, came to the rescue. The word “tchakrulo” can mean either “bound up” or “hard” and “tough,” and the song’s narrative is about a peasant protest against a landowner.

Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

According to Ferris, Carl Sagan had to warm up to the idea of including Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” on the record, but once he did, he defended it against others’ objections. Folklorist Alan Lomax was against it, arguing that rock music was adolescent. “And Carl’s brilliant response was, ‘There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,’” recalls Ferris.

On April 22, 1978, Saturday Night Live spoofed the Golden Record in a skit called “Next Week in Review.” Host Steve Martin played a psychic named Cocuwa, who predicted that Time magazine would reveal, on the following week’s cover, a four-word message from aliens. He held up a mock cover, which read, “Send More Chuck Berry.”

More than four decades later, Ferris has no regrets about what the team did or did not include on the record. “It means a lot to have had your hand in something that is going to last a billion years,” he says. “I recommend it to everybody. It is a healthy way of looking at the world.”

According to the writer, NASA approached him about producing another record but he declined. “I think we did a good job once, and it is better to let someone else take a shot,” he says.

So, what would you put on a record if one were being sent into space today?

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Voyager at 30: Looking Beyond and Within – The Golden Record

A mission that was supposed to last just five years is celebrating its 30th anniversary this fall. Scientists continue to receive data from the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft as they approach interstellar space. The twin craft have become a fixture of pop culture, inspiring novels and playing a central role in television shows, music videos, songs and movies from the 1980s and 1990s. Many of these fictional works focus on what would happen if an alien race were able to locate Earth via Voyager's famous golden records, which include sounds and images of Earth. The selections portray people young and old, male and female -- not to mention examples of many other species -- and include information about every continent on the planet, as well as Earth's location in space.

Earlier NASA missions included plaques with information about Earth, in case an intelligent alien race intercepted the probes. This spurred John Casani, then Voyager's project manager, to appoint astronomer and author Carl Sagan to head a committee to come up with a message for Voyager.

It's the classic message in a bottle. The likelihood of finding it is small, but the payoff is huge if it is found.

Creative Director, Voyager Golden Record Project

In his book "Murmurs of Earth," Sagan later described how the committee created the record and chose its contents. Physicist Frank Drake suggested the idea of a record that would have pictures on one side and sounds on the other side. The group had less than six weeks to come up with a record that would represent the entire population of Earth -- in addition to the planet itself -- if it were ever discovered by an intelligent alien race.

Although the chances of extraterrestials finding the message are extremely slim, the Voyager golden record has become an icon.

" It's the classic message in a bottle. The likelihood of finding it is small, but the payoff is huge if it is found," said Ann Druyan, a science media producer and author. Druyan was appointed creative director of the record project and later married Sagan.

Ed Stone, Voyager's project scientist and former JPL director, explained that although there is almost no chance of the record being found, the record is important as a message to ourselves.

" In a sense it's a unifying message," Stone said. "It's a message from Earth. It contains greetings in many languages, music from many cultures and images that portray our home planet. It's our attempt to say what is Earth, and it's a record of who we think we are."

Druyan also explained that the coupling of music and science was an especially compelling reason to devote so much energy to the record.

" The record represented the idea that science and technology could come together with art," said Druyan, who also designed the sound essay.. "It's one of the few totally great stories that we have about humans. It cost the taxpayers virtually nothing, nobody got killed. It was a way to celebrate the glory of being alive on this tiny blue dot in 1977.

"This was the most romantic and beautiful project ever attempted by NASA. It had the sounds of a kiss, a mother saying hello to her newborn baby for the first time, all that glorious music. Remember, this was during the Cold War. Everyone was living with the knowledge that 50,000 nuclear weapons could go off at any time, and there was a lot of angst about the future. This was something positive -- a way to represent Earth and put our best foot forward. That was irresistible."

Carl Sagan's son Nick was six years old in 1977 when the Voyager records were being assembled. The records feature a recording of him as a child saying, "Hello from the children of planet Earth."

"I had no sense of the magnitude of it at the time," said Nick Sagan, who partially followed in his late father's footsteps by pursuing a career as a science fiction writer. "Literally it was my parents putting me in front of a microphone and saying, 'What would you say to extraterrestrials?'"

Sagan said he began to realize what the record meant as he got older, and as a teen he started to realize what a "strange but wonderful honor" it was.

"It's been a challenge for the rest of my life to live up to that honor. It's always there in my subconscious," he said. "My dad inspired so many people to do so many great things -- to not take things at face value and to look at evidence to search for the truth. It's something that I look to as a beacon."

Sagan said that he and his father discussed the Voyager discoveries in the context of their search for life. They got excited when the spacecraft photographed Titan and Europa, and Sagan noted a change in his father as the years went by.

"One of the things that surprised him was that we didn't find life during his lifetime," he said. "He started to realize that if there's no other life out there, and life is so rare, we need to protect ours. I saw a shift in him. That's when he started to become more socially and politically conscious."

In the end, Sagan believes that Voyager and other extraterrestrial missions are important because of their process rather than their discoveries.

"The question is: What's it all about?" he said. "If we do find life it will change us, but if not it will change things also. The act of looking will tell us so much, and we will learn so much about ourselves."

Written by: Janna Brancolini

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made

By Timothy Ferris

We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium-sized star about two-thirds of the way out from the center of the Milky Way galaxy—around where Track 2 on an LP record might begin. In cosmic terms, we are tiny: were the galaxy the size of a typical LP, the sun and all its planets would fit inside an atom’s width. Yet there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe. Indeed, we made two of them.

The time capsules, really a pair of phonograph records, were launched aboard the twin Voyager space probes in August and September of 1977. The craft spent thirteen years reconnoitering the sun’s outer planets, beaming back valuable data and images of incomparable beauty . In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system, sailing through the doldrums where the stream of charged particles from our sun stalls against those of interstellar space. Today, the probes are so distant that their radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, take more than fifteen hours to reach Earth. They arrive with a strength of under a millionth of a billionth of a watt, so weak that the three dish antennas of the Deep Space Network’s interplanetary tracking system (in California, Spain, and Australia) had to be enlarged to stay in touch with them.

If you perched on Voyager 1 now—which would be possible, if uncomfortable; the spidery craft is about the size and mass of a subcompact car—you’d have no sense of motion. The brightest star in sight would be our sun, a glowing point of light below Orion’s foot, with Earth a dim blue dot lost in its glare. Remain patiently onboard for millions of years, and you’d notice that the positions of a few relatively nearby stars were slowly changing, but that would be about it. You’d find, in short, that you were not so much flying to the stars as swimming among them.

The Voyagers’ scientific mission will end when their plutonium-238 thermoelectric power generators fail, around the year 2030. After that, the two craft will drift endlessly among the stars of our galaxy—unless someone or something encounters them someday. With this prospect in mind, each was fitted with a copy of what has come to be called the Golden Record. Etched in copper, plated with gold, and sealed in aluminum cases, the records are expected to remain intelligible for more than a billion years, making them the longest-lasting objects ever crafted by human hands. We don’t know enough about extraterrestrial life, if it even exists, to state with any confidence whether the records will ever be found. They were a gift, proffered without hope of return.

I became friends with Carl Sagan, the astronomer who oversaw the creation of the Golden Record, in 1972. He’d sometimes stop by my place in New York, a high-ceilinged West Side apartment perched up amid Norway maples like a tree house, and we’d listen to records. Lots of great music was being released in those days, and there was something fascinating about LP technology itself. A diamond danced along the undulations of a groove, vibrating an attached crystal, which generated a flow of electricity that was amplified and sent to the speakers. At no point in this process was it possible to say with assurance just how much information the record contained or how accurately a given stereo had translated it. The open-endedness of the medium seemed akin to the process of scientific exploration: there was always more to learn.

In the winter of 1976, Carl was visiting with me and my fiancée at the time, Ann Druyan, and asked whether we’d help him create a plaque or something of the sort for Voyager. We immediately agreed. Soon, he and one of his colleagues at Cornell, Frank Drake, had decided on a record. By the time NASA approved the idea, we had less than six months to put it together, so we had to move fast. Ann began gathering material for a sonic description of Earth’s history. Linda Salzman Sagan, Carl’s wife at the time, went to work recording samples of human voices speaking in many different languages. The space artist Jon Lomberg rounded up photographs, a method having been found to encode them into the record’s grooves. I produced the record, which meant overseeing the technical side of things. We all worked on selecting the music.

I sought to recruit John Lennon, of the Beatles, for the project, but tax considerations obliged him to leave the country. Lennon did help us, though, in two ways. First, he recommended that we use his engineer, Jimmy Iovine, who brought energy and expertise to the studio. (Jimmy later became famous as a rock and hip-hop producer and record-company executive.) Second, Lennon’s trick of etching little messages into the blank spaces between the takeout grooves at the ends of his records inspired me to do the same on Voyager. I wrote a dedication: “To the makers of music—all worlds, all times.”

To our surprise, those nine words created a problem at NASA . An agency compliance officer, charged with making sure each of the probes’ sixty-five thousand parts were up to spec, reported that while everything else checked out—the records’ size, weight, composition, and magnetic properties—there was nothing in the blueprints about an inscription. The records were rejected, and NASA prepared to substitute blank discs in their place. Only after Carl appealed to the NASA administrator, arguing that the inscription would be the sole example of human handwriting aboard, did we get a waiver permitting the records to fly.

In those days, we had to obtain physical copies of every recording we hoped to listen to or include. This wasn’t such a challenge for, say, mainstream American music, but we aimed to cast a wide net, incorporating selections from places as disparate as Australia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, China, Congo, Japan, the Navajo Nation, Peru, and the Solomon Islands. Ann found an LP containing the Indian raga “Jaat Kahan Ho” in a carton under a card table in the back of an appliance store. At one point, the folklorist Alan Lomax pulled a Russian recording, said to be the sole copy of “Chakrulo” in North America, from a stack of lacquer demos and sailed it across the room to me like a Frisbee. We’d comb through all this music individually, then meet and go over our nominees in long discussions stretching into the night. It was exhausting, involving, utterly delightful work.

“Bhairavi: Jaat Kahan Ho,” by Kesarbai Kerkar

In selecting Western classical music, we sacrificed a measure of diversity to include three compositions by J. S. Bach and two by Ludwig van Beethoven. To understand why we did this, imagine that the record were being studied by extraterrestrials who lacked what we would call hearing, or whose hearing operated in a different frequency range than ours, or who hadn’t any musical tradition at all. Even they could learn from the music by applying mathematics, which really does seem to be the universal language that music is sometimes said to be. They’d look for symmetries—repetitions, inversions, mirror images, and other self-similarities—within or between compositions. We sought to facilitate the process by proffering Bach, whose works are full of symmetry, and Beethoven, who championed Bach’s music and borrowed from it.

I’m often asked whether we quarrelled over the selections. We didn’t, really; it was all quite civil. With a world full of music to choose from, there was little reason to protest if one wonderful track was replaced by another wonderful track. I recall championing Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark Was the Night,” which, if memory serves, everyone liked from the outset. Ann stumped for Chuck Berry’s “ Johnny B. Goode ,” a somewhat harder sell, in that Carl, at first listening, called it “awful.” But Carl soon came around on that one, going so far as to politely remind Lomax, who derided Berry’s music as “adolescent,” that Earth is home to many adolescents. Rumors to the contrary, we did not strive to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” only to be disappointed when we couldn’t clear the rights. It’s not the Beatles’ strongest work, and the witticism of the title, if charming in the short run, seemed unlikely to remain funny for a billion years.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” by Blind Willie Johnson

Ann’s sequence of natural sounds was organized chronologically, as an audio history of our planet, and compressed logarithmically so that the human story wouldn’t be limited to a little beep at the end. We mixed it on a thirty-two-track analog tape recorder the size of a steamer trunk, a process so involved that Jimmy jokingly accused me of being “one of those guys who has to use every piece of equipment in the studio.” With computerized boards still in the offing, the sequence’s dozens of tracks had to be mixed manually. Four of us huddled over the board like battlefield surgeons, struggling to keep our arms from getting tangled as we rode the faders by hand and got it done on the fly.

The sequence begins with an audio realization of the “music of the spheres,” in which the constantly changing orbital velocities of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and Jupiter are translated into sound, using equations derived by the astronomer Johannes Kepler in the sixteenth century. We then hear the volcanoes, earthquakes, thunderstorms, and bubbling mud of the early Earth. Wind, rain, and surf announce the advent of oceans, followed by living creatures—crickets, frogs, birds, chimpanzees, wolves—and the footsteps, heartbeats, and laughter of early humans. Sounds of fire, speech, tools, and the calls of wild dogs mark important steps in our species’ advancement, and Morse code announces the dawn of modern communications. (The message being transmitted is Ad astra per aspera , “To the stars through hard work.”) A brief sequence on modes of transportation runs from ships to jet airplanes to the launch of a Saturn V rocket. The final sounds begin with a kiss, then a mother and child, then an EEG recording of (Ann’s) brainwaves, and, finally, a pulsar—a rapidly spinning neutron star giving off radio noise—in a tip of the hat to the pulsar map etched into the records’ protective cases.

“The Sounds of Earth”

Ann had obtained beautiful recordings of whale songs, made with trailing hydrophones by the biologist Roger Payne, which didn’t fit into our rather anthropocentric sounds sequence. We also had a collection of loquacious greetings from United Nations representatives, edited down and cross-faded to make them more listenable. Rather than pass up the whales, I mixed them in with the diplomats. I’ll leave it to the extraterrestrials to decide which species they prefer.

“United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs”

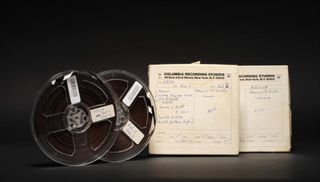

Those of us who were involved in making the Golden Record assumed that it would soon be commercially released, but that didn’t happen. Carl repeatedly tried to get labels interested in the project, only to run afoul of what he termed, in a letter to me dated September 6, 1990, “internecine warfare in the record industry.” As a result, nobody heard the thing properly for nearly four decades. (Much of what was heard, on Internet snippets and in a short-lived commercial CD release made in 1992 without my participation, came from a set of analog tape dubs that I’d distributed to our team as keepsakes.) Then, in 2016, a former student of mine, David Pescovitz, and one of his colleagues, Tim Daly, approached me about putting together a reissue. They secured funding on Kickstarter , raising more than a million dollars in less than a month, and by that December we were back in the studio, ready to press play on the master tape for the first time since 1977.

Pescovitz and Daly took the trouble to contact artists who were represented on the record and send them what amounted to letters of authenticity—something we never had time to accomplish with the original project. (We disbanded soon after I delivered the metal master to Los Angeles, making ours a proud example of a federal project that evaporated once its mission was accomplished.) They also identified and corrected errors and omissions in the information that was provided to us by recordists and record companies. Track 3, for instance, which was listed by Lomax as “Senegal Percussion,” turns out instead to have been recorded in Benin and titled “Cengunmé”; and Track 24, the Navajo night chant, now carries the performers’ names. Forty years after launch, the Golden Record is finally being made available here on Earth. Were Carl alive today—he died in 1996 at the age of sixty-two—I think he’d be delighted.

This essay was adapted from the liner notes for the new edition of the Voyager Golden Record, recently released as a vinyl boxed set by Ozma Records .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Anthony Lydgate

By Amanda Petrusich

By David Remnick

Voyager Golden Records 40 years later: Real audience was always here on Earth

Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Penn State

Disclosure statement

Jason Wright acknowledges funding from NASA, the NSF, the Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Words at The Pennsylvania State University, and from Breakthrough Listen, part of the Breakthrough Initiatives sponsored by the Breakthrough Prize Foundation ( https://breakthroughinitiatives.org/ ).

Penn State provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Forty years ago, NASA launched Voyager I and II to explore the outer solar system. The twin spacecraft both visited Jupiter and Saturn; from there Voyager I explored the hazy moon Titan, while Voyager II became the first (and, to date, only) probe to explore Uranus and Neptune. Since they move too quickly and have too little propellant to stop themselves, both spacecraft are now on what NASA calls their Interstellar Mission , exploring the space between the stars as they head out into the galaxy.

Both craft carry Golden Records : 12-inch phonographic gold-plated copper records, along with needles and cartridges, all designed to last indefinitely in interstellar space. Inscribed on the records’ covers are instructions for their use and a sort of “map” designed to describe the Earth’s location in the galaxy in a way that extraterrestrials might understand.

The grooves of the records record both ordinary audio and 115 encoded images . A team led by astronomer Carl Sagan selected the contents, chosen to embody a message representative of all of humanity. They settled on elements such as audio greetings in 55 languages , the brain waves of “a young woman in love” (actually the project’s creative director Ann Druyan, days after falling in love with Carl Sagan ), a wide-ranging selection of musical excerpts from Blind Willie Johnson to honkyoku , technical drawings and images of people from around the world, including Saan Hunters, city traffic and a nursing mother and child.

Since we still have not detected any alien life, we cannot know to what degree the records would be properly interpreted. Researchers still debate what forms such messages should take . For instance, should they include a star map identifying Earth? Should we focus on ourselves, or all life on Earth? Should we present ourselves as we are, or as comics artist Jack Kirby would have had it, as “the exuberant, self-confident super visions with which we’ve clothed ourselves since time immemorial”?

But the records serve a broader purpose than spreading the word that we’re here on our blue marble. After all, given the vast distances between the stars, it’s not realistic to expect an answer to these messages within many human lifetimes. So why send them and does their content even matter? Referring to earlier, similar efforts with the Pioneer spacecraft , Carl Sagan wrote , “the greater significance of the Pioneer 10 plaque is not as a message to out there; it is as a message to back here.” The real audience of these kinds of messages is not ET, but humanity.

In this light, 40 years’ hindsight shows the experiment to be quite a success, as they continue to inspire research and reflection.

Only two years after the launch of these messages to the stars, “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” imagined the success of similar efforts by (the fictional) Voyager VI. Since then, there have been Ph.D. theses written on the records’ content , investigations into the identity of the person heard laughing and successful crowdfunded efforts to reissue the records themselves for home playback.

The choice to include music has inspired introspection on the nature of music as a human endeavor, and what it would (or even could) mean to an alien species. If an ET even has ears, it’s still far from clear whether it would or could appreciate rhythm, tones, vocal inflection, verbal language or even art of any kind. As music scholars Nelson and Polansky put it , “By imagining an Other listening, we reflect back upon ourselves, and open our selves and cultures to new musics and understandings, other possibilities, different worlds.”

The records also represent humanity’s deliberate effort to put artifacts among the stars. Unlike everything on Earth, which is subject to erosion and all but inevitable destruction (from the sun’s eventual demise, if nothing else), the Golden Records are essentially eternal, a permanent time capsule of humanity. And unlike the Voyager spacecraft themselves – which were designed to have finite lifespans and whose journey into interstellar space was incidental to their primary function of exploring the outer planets – the Golden Records’ only purpose is to serve as ambassadors of humanity to the stars.

Placing artifacts in interstellar space thus makes the galaxy subject to the social studies, in addition to astronomy. The Golden Records mark our claim to interstellar space as part of our cultural landscape and heritage , and once the Voyager spacecraft themselves are not functional any longer, they will become proper achaeological objects . They are, in a sense, how we as a species have planted our flag of exploration in space. Anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan muses , “Has NASA been to interstellar space because this spacecraft has? Have we, as a human species, [now] been to interstellar space?”

I would argue we have, and we are a better species for it. Like the Pioneer plaques and the Arecibo Message before them, the Golden Records inspire us to broaden our minds about what it means to be human; what we value as humans; and about our place and role in the cosmos by having us imagine what we might, or might not, have in common with any alien species our Voyagers eventually encounter on their very long journeys.

- Extraterrestrial life

- Space exploration

- Golden Record

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Operations Coordinator

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

Master copy of the Voyager Golden Record, designed as an audio postcard for intelligent aliens, is up for auction

Carl Sagan's personal copy of the Voyager Golden Record contains 27 pieces of music and 22 minutes of sound meant to capture the beauty of life on Earth.

Nearly 46 years ago, NASA launched two small probes carrying a pair of gold-plated copper records that would soon become the farthest human-made objects from Earth ever created. The probes — named Voyager 1 and 2 — and their golden payloads are currently floating more than 12 billion miles (19 billion kilometers) from Earth, and gaining distance every day. But this week, you can add a master copy of those legendary records to your personal vinyl collection without even leaving your home — and all you need is half a million dollars.

On July 27, Sotheby's will auction two double-sided reels of audio tape containing the master recordings of the Voyager Golden Record, plucked from the personal collection of celebrity astronomer Carl Sagan and his wife, Ann Druyan, both of whom helped with the record's design and development in 1977.

Like the gold-plated discs they begot, the master tapes contain 27 pieces of music intended to encapsulate the world's musical heritage, including Beethoven, Chuck Berry, a Navajo chant and an Indian vocal raga. The tapes also include 22 minutes of nature sounds and human voices speaking in 59 languages, all of which were designed as a sort of audio postcard for any potentially intelligent aliens that might one day chance upon the Voyager probes. (The probes also contain an audio player with pictorial instructions, and a star map showing the location of Earth .)

Related: Are aliens real?

"Bursting with the myriad sounds of life, Carl and I and our colleagues designed the Golden Record to be a testament to the beauty of being alive on Earth," Druyan, who was the creative director of NASA's Voyager Interstellar Message Project that produced the records, said in a Sotheby’s statement. "We hoped it would capture the richness and diversity of our world."

— Aliens haven't contacted Earth because there's no sign of intelligence here, new answer to the Fermi paradox suggests

— Why have aliens never visited Earth? Scientists have a disturbing answer

— 'Leaking' cell phone towers could lead aliens straight to Earth, new study suggests

Only eight copies of the records were ever made, including the two gold-plated versions now riding through interstellar space on the Voyager probes. Bidding for the master tapes begins at $300,000, and Sotheby's expects them to fetch up to $600,000. Bidding closes at 11:20 a.m. ET on July 27.

For those of us not looking to spend half a million, NASA has provided the full track list , and there are numerous playlists of the record's contents available on YouTube and music streaming platforms. Take a listen — and hope, for a moment, that life in another star system may one day bump the same jams.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.

NASA's downed Ingenuity helicopter has a 'last gift' for humanity — but we'll have to go to Mars to get it

Object that slammed into Florida home was indeed space junk from ISS, NASA confirms

'Uncharted territory': El Niño to flip to La Niña in what could be the hottest year on record

Most Popular

- 2 The universe may be dominated by particles that break causality and move faster than light, new paper suggests

- 3 Nightmare fish may explain how our 'fight or flight' response evolved

- 4 Intel unveils largest-ever AI 'neuromorphic computer' that mimics the human brain

- 5 Lyrid meteor shower 2024: How to watch stunning shooting stars and 'fireballs' during the event's peak this week

- 2 Global 'time signals' subtly shifted as the total solar eclipse reshaped Earth's upper atmosphere, new data shows

- 3 2,500-year-old skeletons with legs chopped off may be elites who received 'cruel' punishment in ancient China

- 4 Giant, 82-foot lizard fish discovered on UK beach could be largest marine reptile ever found

- 5 Southern Grasshopper mouse: The tiny super-predator that howls at the moon before it kills

11 Pieces of Media on the Voyager Golden Record

By michele debczak | apr 11, 2021.

At this moment, two gold-plated copper records are hurtling through space, speeding beyond our solar system. The Voyager 1 and 2 probes launched in 1977 , and they’ve since traveled billions of miles from Earth. They are currently the loneliest human-made objects in the universe—and they may stay that way forever—but they were built to make a connection.

The purpose of NASA ’s Voyager mission is to illustrate life on Earth to any intelligent aliens that come across the spacecraft. The records on board contain media selected by a committee chaired by scientist Carl Sagan. If extraterrestrials can use the instructions engraved on the disc's cover to access its contents, they’ll be exposed to animal noises, classical music, and photographs of people from around the world. Here are some pieces of media that were chosen to represent our planet.

1. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven is one of many classical artists representing the music of Earth on the Voyager record. In addition to his Fifth Symphony , the composer’s String Quartet No. 13, Opus 130, is also included on the track list.

2. Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

Though there are many musical compositions on the Voyager Golden Record , the inclusion of “Johnny B. Goode” stirred controversy. Critics claimed rock n’ roll was too adolescent for a project of such significance. Carl Sagan responded by saying, “There are a lot of adolescents on the planet.”

3. A Mandarin Greeting and Invitation

The Voyager project recorded UN delegates from around the world saying greetings in 54 different languages. Most are straightforward, but the Mandarin message includes an invitation. Translated to English, it says: "Hope everyone's well. We are thinking about you all. Please come here to visit when you have time."

4. Humpback Whale Songs

The greetings section of the record features one language that doesn’t belong to humans. Interspersed between the spoken audio clips are the sounds of singing humpback whales . There’s a reason whales were included with the greetings rather than the other animal noises on the record—it was the committee’s way of acknowledging that humans aren’t the only intelligent life on Earth.

5. The UN Building

The Voyager committee chose the UN Building to represent modern urban architecture. The record includes two images of the New York City skyscraper, both taken at the same angle. One depicts the structure during the day and the other shows it at night .

6. A Traffic Jam

The Voyager record highlights many technological marvels from the time it was made, including a rocket and an airplane. The photo of a traffic jam in Thailand that was included may seem less impressive, but it accurately depicts how we use cars on our planet.

7. A Bulgarian Folk Song

The Voyager committee wanted the record's music to represent a wide range of eras and cultures. One track, titled "Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin," is a traditional folk song from Bulgaria . Sung by Valya Balkanska, it’s about a famous rebel leader from the country’s history. Folk music from Azerbaijan, Georgia, and the Navajo people also made it onto the compilation.

8. Ann Druyan’s Brainwaves

While working on the Voyager committee, Ann Druyan had the idea to record her brainwaves, turn them into audio, and copy them onto the record. She spent an hour hooked up to electrical impulse-measuring systems while thinking various thoughts, including what it’s like to fall in love. She and Sagan—her collaborator on the Voyager record project—had recently gotten engaged.

9. A Map of the Solar System

The Voyager mission is designed to travel far, but it will always hold evidence of where it came from. One of the images on the record shows a picture of our solar system with a map illustrating Earth’s location.

10. People Eating

Some human behaviors are tricky to capture in one image. To show the different ways people consume food and drink, the Voyager committee included a photo of someone licking ice cream, someone else biting into a sandwich, and a third person pouring water into their mouth.

11. A Morse Code Message

Another type of communication represented on the Voyager record is Morse code . The message translates to the Latin saying ad astra per aspera , or “to the stars through hard work.”

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Voyagers' Records Wait for Alien Ears

The identical Voyagers 1 and 2 were launched in 1977 and are currently much farther away from Earth and the sun than Pluto. Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

The identical Voyagers 1 and 2 were launched in 1977 and are currently much farther away from Earth and the sun than Pluto.

The Voyager phonograph records are 12-inch gold-plated copper disks containing sounds and images selected to portray life on Earth to extra-terrestrials who may encounter the spacecraft. Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

The Voyager phonograph records are 12-inch gold-plated copper disks containing sounds and images selected to portray life on Earth to extra-terrestrials who may encounter the spacecraft.

Tunes for E.T.

Voyager's golden record contains music from around the world. A sampling of some of the record's actual contents:

'The Well-Tempered Clavier;' performed by Glenn Gould; Bach, Prelude and Fugue in C, No.1. Book 2

'johnny b. goode' performed by chuck berry, 'melancholy blues' performed by louis armstrong and his hot seven, spinning the golden record.

Carl Sagan and other scientists assembled 115 images, plus sound, music and other elements on Voyager's gold record.

Thirty years ago this summer, two spacecraft lifted off from Earth. Both carried a gift for any extra-terrestrial life that might be on the receiving end.

Voyager 1 and its cousin, Voyager 2, carried rock-and-roll by Chuck Berry, jazz by Louis Armstrong, Bach, Beethoven, and other music from around the world.

The 27 pieces were contained in a copper record, accompanied by a needle and playback instructions.

Neither spacecraft will reach another star system anytime soon. Still, scientists are celebrating the anniversary of some of the hardest-working spacecraft in the cosmos.

Originally built to explore Jupiter and Saturn, today Voyager 1 is farther from Earth than any other human-made object and speeding outward at more than 38,000 miles per hour. Both spacecraft are still sending scientific information about their surroundings to Earth.

Though three-quarters of the record is taken up with music, a committee chaired by the late Carl Sagan also decided to include pictures from Earth, greetings in 55 languages, and natural sounds from the planet. Science writer Timothy Ferris produced the record, and he says that even today the Voyager time capsules still hold up.

"We thought of the record in terms of presenting some of the things important to us as a species, and music is important to people all over the world even though it's not often possible to say why," says Ferris, who is now an emeritus professor at the University of California, Berkeley and the author of several popular science books, including The Whole Shebang and Coming of Age in the Milky Way . His upcoming PBS special "Seeing in the Dark", will air on Wednesday, September 19."

Ferris says that the committee that chose the music consulted with performers, musicologists, composers, and others before they narrowed down the selections. Naturally, they ran into political pressure.

"Someone told me that we should have an Irish song because Tip O'Neill was Speaker of the House at the time," Ferris recalls.

It will be around 40,000 years before the spacecraft make a close approach to any other planetary system. But Ferris and NASA scientists expect the nuclear-powered Voyager crafts to live on, perhaps one day meeting beings who might give the craft's golden contents a spin.

Liane Hansen spoke with Ferris about the Voyager's music and its long life.

Related NPR Stories

Searching the sky for alien laser messages, focus on stars in search for earth-like worlds, cassini team releases images from saturn mission, kansas town is launch pad for bid at flight record, space photography marks anniversary, web resources, murmurs of earth, buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Music for Aliens: Campaign Aims to Reissue Carl Sagan’s Golden Record

By Kenneth Chang

- Sept. 21, 2016

Carl Sagan’s Voyager Golden Record — of sounds of Earth, recorded greetings and an eclectic mix of music that was sent into space — has long been out of print and pretty much unobtainable for decades.

One copy of the record is attached to NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft, which has entered interstellar space , the farthest artifact ever tossed out by humanity. A second copy, on Voyager 2, is not quite as distant, just 10 billion miles away.

Both are receding from Earth at more than 35,000 miles per hour.

Not even Dr. Sagan, the Cornell astrophysicist who led the creation of the record in 1977 for the listening pleasure of any aliens who happened upon it, could get a copy.

He asked. NASA said no.

But now, a Kickstarter crowdfunding project begun on Wednesday is planning to reissue it, long a dream of David Pescovitz, an editor and managing partner at Boing Boing , the technology news website, and a research director at the nonprofit Institute for the Future .

“When you’re 7 years old, and you hear about a group of people creating messages for possible extraterrestrial intelligence,” Mr. Pescovitz said, “that sparks the imagination. The idea always stuck with me.”

He teamed up with Timothy Daly, a manager at Amoeba Music in San Francisco, and Lawrence Azerrad, a graphic designer who has created packaging for Sting, The Beach Boys, Wilco and other musicians.

The reissue will not exactly be like the original, which was pressed out of a gold-plated copper disk. The original was also intended to be played at 16 2/3 revolutions per minute, half of the usual speed of LP records. That was necessary to cram in a variety of sounds of Earth, spoken greetings in 55 languages, 116 images and 90 minutes of music.

The reissue will consist of three LPs pressed out of vinyl recorded at normal LP speed. The box set will cost $98 plus shipping, with the project aiming to raise $198,000. For the MP3 generation — or anyone without a phonograph — digital downloads are available for $25.

Mr. Pescovitz aims to distribute the records next year in time for the 40th anniversary of the Voyager launches. (Voyager 2 launched first, on Aug. 20, 1977; Voyager 1 launched a couple of weeks later, on Sept. 5.)

Perhaps now the recording, meant to encapsulate thousands of years of music, will finally find an audience. The songs include a Peruvian wedding song, a Pygmy girls’ initiation song, a movement from one of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, and “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry.

“Isn’t it funny?” recalled Timothy Ferris, a science writer who produced the original record. “It hasn’t been heard by any aliens yet, and it hasn’t hardly been heard by humans.”

A CD-ROM version was issued in 1992, and NASA has since put digital versions of the greetings and sounds of Earth — but not the music — on SoundCloud . But this is the first time it will be available as an LP.

“For us, it’s creating a physical, tangible object,” Mr. Pescovitz said.

Mr. Ferris said the song selections were done by consensus, although Dr. Sagan, who died in 1996 , did not like “Johnny B. Goode” at first. Alan Lomax, a folk music archivist who was another volunteer member of the committee selecting material for the Voyager records, also disliked the song and complained to Dr. Sagan that it was adolescent.

Mr. Ferris recalled Sagan’s response: “Well, there are a lot of adolescents on Earth, too.” The song went on the record.

But Mr. Ferris added, “You can’t take it too far or you’d be doing Miley Cyrus.”

A dozen copies of the golden record were made. Afterward, Dr. Sagan wrote to NASA, asking if he and John Casani, the project manager for Voyager, could obtain copies as mementos.

Robert A. Frosch, the NASA administrator, replied that all of the copies had been distributed to various institutions, mostly NASA centers, except for one copy reserved for President Jimmy Carter.

Today, it is not easy to get a glimpse of a copy. The aluminum cover can be seen at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, but the record itself is not on display. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., the NASA center that operates the continuing Voyager missions, has its copy of the record on display in a case in an auditorium that is open to the public, at least during public lectures .

What’s Up in Space and Astronomy

Keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe..

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other 2024 event that’s out of this world with our space and astronomy calendar .

Scientists may have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, a mysterious cosmic force . That could be good news for the fate of the universe.

A new set of computer simulations, which take into account the effects of stars moving past our solar system, has effectively made it harder to predict Earth’s future and reconstruct its past.

Dante Lauretta, the planetary scientist who led the OSIRIS-REx mission to retrieve a handful of space dust , discusses his next final frontier.

A nova named T Coronae Borealis lit up the night about 80 years ago. Astronomers say it’s expected to put on another show in the coming months.

Is Pluto a planet? And what is a planet, anyway? Test your knowledge here .

- Created with Sketch.

The Golden Record: Carl Sagan’s Interstellar Portrait of Humanity

The Voyager Golden Record is a unique audio-visual time capsule developed by NASA and affixed to the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecrafts. Designed to communicate to possible space-faring civilizations something of the diversity of life and culture on our world, the Golden Record consisted of greetings in 59 human languages and those of the humpback whales, 115 images of life here, the sounds of Earth, and 27 pieces from the world’s musical traditions. It has been called the beginning of the concept of “world music.”

It was Voyager 1 that looked homeward from high above Neptune to take, at Carl Sagan’s behest, the iconic Pale Blue Dot photograph. Upon flawlessly completing the first phase of their mission, the NASA Voyagers 1 and 2 made for the open sea of interstellar space, teaching us the actual shape of our solar system as it moves through the galaxy. The Golden Record is an unparalleled document in the history of space exploration and our civilization.

Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan’s personal copy of the master recording for NASA’s iconic Voyager Golden Record will be offered in Sotheby’s Space Exploration auction in New York on 27 July as a part of Geek Week: Remixed .

More from Sotheby's

Stay informed with sotheby’s top stories, videos, events & news..

By subscribing you are agreeing to Sotheby’s Privacy Policy . You can unsubscribe from Sotheby’s emails at any time by clicking the “Manage your Subscriptions” link in any of your emails.

Search form

The Golden Record, The Sounds of Earth

In 1977, NASA launched the Voyager space probes 1 and 2 to study the outer solar system. As of 2020 both probes are over 11 billion miles from earth, or three times the distance to Pluto. However, there is still 40,000 years until the probes will encounter another planetary system. The Golden Record is intended as a message in the event that one of the Voyager probes is eventually found by life forms outside of our solar system.

Dr. Carl Sagan, and other members of a NASA committee, assembled the Golden Record as a way to portray life on Earth in the form of sounds and images. At the time of the launch, Dr. Sagan said: “The spacecraft will be encountered, and the record played only if there are advanced space-faring civilizations in interstellar space, but the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

The record features spoken greetings in 55 different languages, all of which can be found on NASA’s SoundCloud account. It also contains samples of other human sounds like laughter, music and nature sounds such as animal calls and weather patterns.

It also contains 116 images, including equations, diagrams and photos, to depict our understanding of space, chemistry, biology, and aspects of humanity’s culture and achievements.

The first voice recording on the Golden Record is an introduction from the UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim (1918 – 2007) saying, “As the Secretary-General of the United Nations, an organization of 147 member states who represents almost all of the human inhabitants of the planet Earth, I send greetings on behalf of the people of our planet. We step out of our Solar System into the Universe, seeking only peace and friendship, to teach if we are called upon, to be taught if we are fortunate. We know full well that our planet and all its inhabitants are but a small part of this immense Universe that surrounds us, and it is with humility and hope that we take this step.”

The USA President Jimmy Carter (1924 – ) said, “We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.”

Fact Magazine

- Exhibitions

Now reading:

Carl Sagan’s legendary message to aliens, the Voyager...

Share this:

- Access All Areas

- Against the Clock

- Documentaries

- FACT Freestyles

- In The Studio

- How To Make A Track

- FACT Premieres

- Record Shopping

- Singles Club

- Dubplate Masters

- The Vinyl Factory Films

Carl Sagan’s legendary message to aliens, the Voyager Golden Record, to get first vinyl release

A document of humankind’s existence for extra-terrestrials.

In 1977, Carl Sagan sent a “bottle into the cosmic ocean” in the form of the Voyager Golden Record, a golden LP containing songs, sounds and images of humankind, which he placed on both Voyager spacecrafts. Now Ozma Records has launched a Kickstarter for a stunning 40th anniversary release honoring an album that could one day be the only record left of humanity.

Remastered with Timothy Ferris, the original Voyager record producer, Ozma’s gold-vinyl release recreates the sleeve designed to show intelligent alien life how to play it. The visual elements embedded within the original record (which is roughly 13 billion miles away from Earth at the time of this writing) come instead in a hardcover book displaying images of humanity from examples of nature to diagrams of the human body to images of people eating, drinking and playing.

Most importantly, the original tracklist remains untouched. Sagan stuffed his record with European classical artists such as Beethoven and Mozart, nature field recordings, greetings in 55 languages (including whale!) and music from a wide range of different cultures including Japan, Zaire, New Guinea, Java, Senegal, China, India and more. He also included jazz, blues and, after a fierce amount of arguing with government officials, an unpleasant “adolescent” music called rock and roll (“There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,” Sagan famously responded).

One famous exclusion is the Beatles, but there’s an interesting explanation why. Sagan suggested ‘Here Comes The Sun’ be included, but the group’s label, EMI, refused to allow NASA the copyright permission.

Explore a portion of the record alongside some of its artwork below and contribute to the Kickstarter here .

More from News

Music you can buy on Bandcamp today to help support artists during the pandemic

Friday, March 20

Experimental rap duo Model Home channel weird dub energy on ‘Faultfinder’

Thursday, March 12

Kelora return with an eerie night bus lament on ‘X24’

FACT to present Homoelectric at Lovebox 2020 with DJ Harvey, Krystal Klear and more

Wednesday, March 11

Shabazz Palaces’ Ishmael Butler reflects on his son growing up in ‘Fast Learner’ video

Tuesday, March 10

Asian Dope Boys team up with City, Dis Fig and Gabber Modus Operandi for TRANCE performance

Monday, March 9

YGG move in the shadows in the video for new track, ‘Fathers’

Junglepussy reflects on the surreal nature of love in ‘Arugula’ video

Thursday, March 5

Ital Tek fights sleep deprivation on new track, ‘Deadhead’

Nyege Nyege Tapes’ Metal Preyers take on DIY horror with ‘The Caller’ video

8 years ago

2 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

4 weeks ago

1 month ago

2 months ago

3 months ago

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

golden record / whats on the record

Greetings to the universe in 55 different languages.

A golden phonograph record was attached to each of the Voyager spacecraft that were launched almost 25 years ago. One of the purposes was to send a message to extraterrestrials who might find the spacecraft as the spacecraft journeyed through interstellar space. In addition to pictures and music and sounds from earth, greetings in 55 languages were included.

NASA asked Dr Carl Sagan of Cornell University to assemble a greeting and gave him the freedom to choose the format and what would be included. Because of the launch schedule, Sagan (and those he got to help him) was not given a lot of time. Linda Salzman Sagan was given the task of assembling the greetings.

The story behind the creation of the "interstellar message" is chronicled in the book, "Murmurs of Earth", by Carl Sagan, et al. Unfortunately, not much information is given about the individual speakers. Many of the speakers were from Cornell University and the surrounding communities. They were given no instructions on what to say other than that it was to be a greeting to possible extraterrestrials and that it must be brief. The following is an excerpt by Linda Salzman Sagan from the book:

"During the entire Voyager project, all decisions were based on the assumption that there were two audiences for whom the message was being prepared - those of us who inhabit Earth and those who exist on the planets of distant stars."

"We were principally concerned with the needs of people on Earth during this section of the recording. We recorded messages from populations all over the globe, each representative speaking in the language of his or her people, instead of sending greetings in one or two languages accompanied by keys for their decipherment. We were aware that the latter alternative might have given the extraterrestrials a better chance of understanding the words precisely, though it would have raised the thorny question of which two languages to send. We felt it was fitting that Voyager greet the universe as a representative of one community, albeit a complex one consisting of many parts. At least the fact that many different languages are represented should be clear from the very existence of a set of short statements separated by pauses and from internal evidence - such as the initial greeting "Namaste," which begins many of the greetings from the Indian subcontinent. The greetings are an aural Gestalt, in which each culture is a contributing voice in the choir. After all, by sending a spaceship out of our solar system, we are making an effort to de-provincialize, to rise above our nationalistic interests and join a commonwealth of space-faring societies, if one exists."

"We made a special effort to record those languages spoken by the vast majority of the world's inhabitants. Since all research and technical work on the record had to be accomplished within a period of weeks, we began with a list of the world's most widely spoken languages, which was provided by Dr. Steven Soter of Cornell. Carl suggested that we record the twenty-five most widely spoken languages. If we were able to accomplish that, and still had time, we would then try to include as many other languages as we could."

"The organization of recording sessions and the arduous legwork involved in finding, contacting and convincing individual speakers was handled by Shirley Arden, Carl's executive assistant, Wendy Gradison, then Carl's editorial assistant, Dr. Steven Soter, and me. The master table, reproduced on pages 134 through 143, which shows each of the languages, the speaker's name, their comments in the original language, an English translation, and the real and fractional number of human beings who speak that language, was largely Shirley's idea. We contacted various members of the Cornell language departments, who cooperated with us on very short notice and provided numerous speakers, even though school was ending and many people were leaving for summer vacations. Other speakers were more difficult to find. sometimes it meant sitting for hours, telephoning friends of friends who might know someone who could speak, let's say, the Chinese Wu dialect. After finding such a person, we had to determine whether he or she would be available during the hours when the recording sessions had been scheduled. Even while the recording sessions were going on, we were still trying to find and recruit speakers of languages not yet represented. Often people waiting to record would suggest names of individuals fluent in the very languages we were looking for. Immediately we called those people, explained the project and our plight, and asked them to come at once. Many people did just that."

"Bishun Khare, a senior physicist in the Laboratory for Planetary Studies, was responsible almost singlehandedly for the participation of the Indian speakers. He personally called friends and member of the Cornell Indian community, explaining the undertaking to them and asked for and received their cooperation."

"There were only a few disappointments, where someone had agreed to come to a recording session, could not and forgot to let us know in time for us to make other arrangements. It wasn't always possible to find replacements at the last minute, so there are some regrettable omissions - Swahili is one."

All the greetings, written in the appropriate language, translated to English, and with the name of the speakers, are included in the book. A CD-ROM, which accompanied the 1992 version of the book, included the spoken versions.

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts

- Money market accounts

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Car insurance

- Home buying

- Options pit

- Investment ideas

- Research reports

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

NASA's Voyager 1 phones home after months

NASA's Voyager 1 probe -- the most distant man-made object in the universe -- is returning usable information to ground control following months of spouting gibberish, the US space agency announced Monday.

The spaceship stopped sending readable data back to Earth on November 14, 2023, even though controllers could tell it was still receiving their commands.

In March, teams working at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory discovered that a single malfunctioning chip was to blame, and devised a clever coding fix that worked within the tight memory constraints of its 46-year-old computer system.

"Voyager 1 spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems," the agency said.

"The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again."

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was mankind's first spacecraft to enter the interstellar medium, in 2012, and is currently more than 15 billion miles from Earth. Messages sent from Earth take about 22.5 hours to reach the spacecraft.

Its twin, Voyager 2, also left the solar system in 2018.

Both Voyager spacecraft carry "Golden Records" -- 12-inch, gold-plated copper disks intended to convey the story of our world to extraterrestrials.

These include a map of our solar system, a piece of uranium that serves as a radioactive clock allowing recipients to date the spaceship's launch, and symbolic instructions that convey how to play the record.

The contents of the record, selected for NASA by a committee chaired by legendary astronomer Carl Sagan, include encoded images of life on Earth, as well as music and sounds that can be played using an included stylus.

Their power banks are expected to be depleted sometime after 2025. They will then continue to wander the Milky Way, potentially for eternity, in silence.

Recommended Stories

Techcrunch space: engineering the future.

Don't worry -- we'll be diving into the Mars Sample Return news shortly. This week's SOTW segment is dedicated to Mars Sample Return, NASA's troubled and ambitious plan to bring Martian rock and dust back to Earth. NASA administrator Bill Nelson has pronounced the agency’s $11 billion, 15-year plan to collect and return samples from Mars insufficient.

UnitedHealth says Change hackers stole health data on 'substantial proportion of people in America'

Health insurance giant UnitedHealth Group has confirmed that a ransomware attack on its health tech subsidiary Change Healthcare earlier this year resulted in a huge theft of Americans' private healthcare data. UnitedHealth said in a statement on Monday that a ransomware gang took files containing personal data and protected health information that it says may "cover a substantial proportion of people in America." Change Healthcare processes insurance and billing for hundreds of thousands of hospitals, pharmacies and medical practices across the U.S. healthcare sector; it has access to massive amounts of health information on about half of all Americans.

Report: Hornets interviewing former NBA, Duke guard JJ Redick for head coaching vacancy

Redick currently works for ESPN as NBA analyst.

Zuckerberg wants more companies to build Meta-powered headsets

Mark Zuckerberg says Meta will open up its Quest operating system so that third-party companies can build new headsets.

Report: Jets trading QB Zach Wilson to Broncos

Wilson's starting over in Denver.

Here are the 30+ startups showcasing at HAX's May 1 Demo Day

A few weeks back, TechCrunch ventured out to New Jersey to pay an early visit to HAX’s Newark offices. HAX’s China operations have shrunk considerably since then, courtesy of a global pandemic and all of the ensuing lockdowns. In some ways, the Newark space is a reflection of the Shenzhen offices.

US government says security flaw in Chirp Systems' app lets anyone remotely control smart home locks

A vulnerability in a smart access control system used in thousands of U.S. rental homes allows anyone to remotely control any lock in an affected home. U.S. cybersecurity agency CISA went public with a security advisory last week saying that the phone apps developed by Chirp, which residents use in place of a key to access their homes, "improperly stores" hardcoded credentials that can be used to remotely control any Chirp-compatible smart lock. Apps that rely on passwords stored in its source code, known as hardcoding credentials, are a security risk because anyone can extract and use those credentials to perform actions that impersonate the app.

What is the Federal Reserve?

The Federal Reserve ensures the health and stability of the nation’s banks and economy through monetary policy and interbank lending.

Here's a lab-grown diamond startup that’s attracted a16z's attention

What's more, the company expects to generate $20-$30 million in revenue this year, and has a three-month customer repurchase rate of roughly 20%, according to its founder and CEO, Adam Hua. Pascal's pitch is that it can make diamond jewelry accessible by using lab-grown diamonds that are chemically and physically akin to natural diamonds but cost one-twentieth of the price. The company's gem-studded jewelry starts at as little as $70, and it is hoping using cultivated diamonds will help it gain a foothold in the more affordable segment of the wider jewelry market.

2024 NFL Draft: Dream fantasy football landing spots for top rookies

With the 2024 NFL Draft nearly here, fantasy football analyst Matt Harmon plays matchmaker for the top prospects at each position.

Anthony Davis fed up with not winning Defensive Player of the Year: 'The league doesn't like me'

Does Davis have a DPOY case? The Lakers' star definitely thinks so.

Stock market today: S&P 500 snaps 6-day losing streak ahead of Big Tech earnings rush

Big Techs are the highlight as hopes rest on this week's flood of earnings to reassure and reignite the market.

Tesla earnings week spotlights price cuts, Elon's 'balls to the wall' autonomy push

As Tesla gears up to report what will likely be unimpressive financial results for the first quarter on Tuesday, the company is making more moves to go “balls to the wall for autonomy,” as CEO Elon Musk put it last week in a post on X. Over the weekend, Tesla dropped the price of its Full Self-Driving (FSD) advanced driver-assistance system to $8,000, down from $12,000. The push to get FSD into more cars could be a bid to collect more data as Tesla works to boost the neural networks that will power fuller-scale autonomy.

Based on the odds, here's what the top 10 picks of the NFL Draft will be

What would a mock draft look like using just betting odds?

Substack rival Ghost confirms it will join the fediverse in 2024

Ghost, an open source rival to Substack's newsletter platform, has confirmed it will this year officially join the fediverse -- or the open social network of interconnected servers that includes apps like Mastodon, Pixelfed, PeerTube, Flipboard and, more recently, Instagram Threads, among others. Founder John O’Nolan had explained in a post on Threads that there are many potential ways that Ghost could leverage federation in its software but wanted to know how users would expect things to work. According to some replies, the hope was that Ghost's blog and newsletter authors would become fediverse accounts, while each of their posts would be federated to the fediverse.

'Send now, pay later' startup Pomelo lands $35M Series A from secretive Vy Capital, Founders Fund

Pomelo, a startup that combines international money transfer with credit, has raised $35 million in a Series A round led by Dubai venture firm Vy Capital, TechCrunch has exclusively learned. Additionally, the company is announcing a $75 million expansion of its warehouse facility. Founders Fund and A* Capital also participated in the financing, along with early investor Afore Capital, and others.

EU opens probe of TikTok Lite, citing concerns about addictive design

The European Union has opened a second formal investigation into TikTok, announcing Monday that it suspects the video sharing platform of breaking the bloc's Digital Services Act (DSA), an online governance and content moderation framework. The Commission also said it's minded to impose interim measures that could force the company to suspend access to the TikTok Lite app in the EU while it investigates concerns the app poses mental health risks to users. Although the EU has given TikTok until April 24 to argue against the measure -- meaning the app remains accessible for now.

The 30 best Walmart deals to shop this week — save up to 80% on outdoor gear, gardening supplies, tech and more

Some major deals on board: a Mother's Day-ready digital picture frame for $30 off, a cordless 6-in-1 stick vac for just $80, and a Chromebook laptop for under $150.

Tales of the Shire trailer shows what life as a regular Hobbit looks like

Weta Workshop and Private Division have released the first trailer for Tales of The Shire. You play as a Hobbit in this Lord of the Rings cozy life sim.

Informatica makes a point to say it's not for sale — to Salesforce or anyone else