Important note about COVID Red Settings:

At Orange our libraries are open with face masks required. Vaccine passes are no longer required. Please stay home if you are unwell. Learn more about visiting our branches at Orange .

Service update:

Miramar Library will reopen at 2pm — maintenance related to last night's stormy weather is now complete. Thank you for your patience.

Service note:

Wadestown Library will close early on Thursday 12 August at 5:30pm for a community meeting.

Wellington City Libraries

Te matapihi ki te ao nui, te haerenga a ngā piringa pāka ki aotearoa i te tau 1981 the 1981 springbok tour of new zealand.

Other heritage topics

- Architecture |

- The sinking of the Wahine |

- Wellington waterfront |

- Earthquakes in Wellington |

- More heritage resources

The rivalry between the Springboks and the All Blacks is one of the longest and most enduring between two sporting nations. In the past, generations of rugby players and enthusiasts from both countries viewed a series victory over the other nation as being the pinnacle of achievement in the sport. Alongside the history of fierce competition went a tradition of hospitality towards the visiting side.

In 1956 and 1965 when the South African rugby team toured New Zealand, they were showered with warmth and generosity wherever they went. Yet 25 years later, the 1981 Springbok tour became one of the most divisive events in New Zealand history.

Its impact went far beyond the rugby ground as communities and families divided and tensions spilled out onto the streets and into the living rooms of the nation. What were the events that made this tour so significant? What motivated ordinary Kiwis to take such extraordinary action against one another?

Although things had been far from perfect between my parents, the Springbok tour caused such tension and stress that we could not live together in the same house and function as a family unit. An example of the increase was when we, as a family, watched the evening news. Often one side would raise their voices in abuse and offensive name calling towards public figures. Later the abuse was turned in an indirect way on individual family members. This was done by blaming the chaos and disruption to rugby games in individual family members, their friends and associations. As the tour went on and the turmoil increased, the negative feelings intensified to such as degree that feelings of dislike, anger and incomprehension dominated our home. It's Just a Game (anon), in, The New Zealand Experience : 100 Vignettes, collected by B. Shaw & K. Broadley, 1985 .

From Digital NZ

Central library closure — collection availability.

Unfortunately much of our heritage collection is currently not available through our online catalogue — because of the closure of the Central Library, much of this collection is in storage. We hope to make it available again soon, but in the meantime, we suggest visiting the National Library of New Zealand in Thorndon (Corner Molesworth & Aitken St) to access these book titles and newspaper resources.

- Visiting the National Library

- Using the National Library Catalogue

Newspaper articles

Unfortunately, contemporary newspaper accounts of the Springbok Tour from 1981 fall into a time period where newspapers are generally not even indexed for searching, let alone available in full text online — see our finding historical Wellington newspaper articles resource.

That being said, information about (and sometimes the full text of) many anniversary accounts (10 years, 20 years later etc.), can be found online (see Online databases below) — and contemporary accounts can be accessed on microfilm if you know approximate dates (we've provided a table of key dates below).

Finding Historical Wellington Newspapers

Tip: Remember that many reports will not appear in newspapers until the following day.

Magazines — online databases

Our online databases can also be used to access a large number of articles about the tour which have previously been published in magazines . Though the databases do not go back as far as 1981, they do contain many retrospective articles written since then.

- Magazine databases

- New Zealand databases

- Newspaper databases

To access contemporary accounts of the Springbok Tour in magazines, we recommend visiting the National Library on Molesworth Street (see collection note above).

To find magazine titles of interest, have a read of the article below:

Story — Magazines and periodicals in New Zealand

Heritage Links (Local History)

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Rugby, racism and the battle for the soul of Aotearoa New Zealand

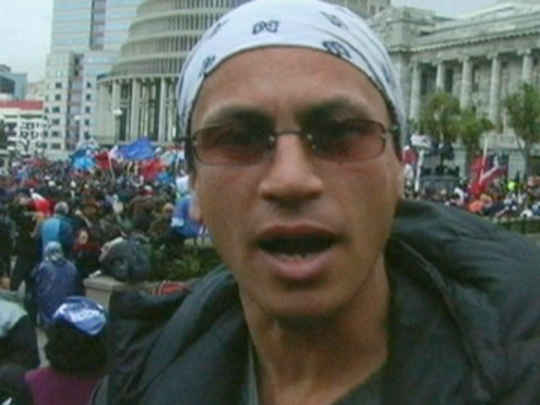

The Springboks’ tour and the protests that ensued 40 years ago helped set the fight for Māori rights on a stronger path

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand will always have a special place in any narrative about the international fight against apartheid in South Africa.

The protests against the Springboks reverberated around the world – delivering a savage psychological blow to South Africa’s white regime while giving a resounding boost to the oppressed majority.

This weekend marks the 40th anniversary of the first rugby Test of the Springboks’ tour of New Zealand in Christchurch, but well before that game was played, the political significance of the visit had eclipsed any results on the field.

Three weeks before the first Test, the second game of the tour was to be played in Hamilton, and white South Africans in their droves got out of bed in the middle of the night to watch the first ever live telecast of a rugby game in the country.

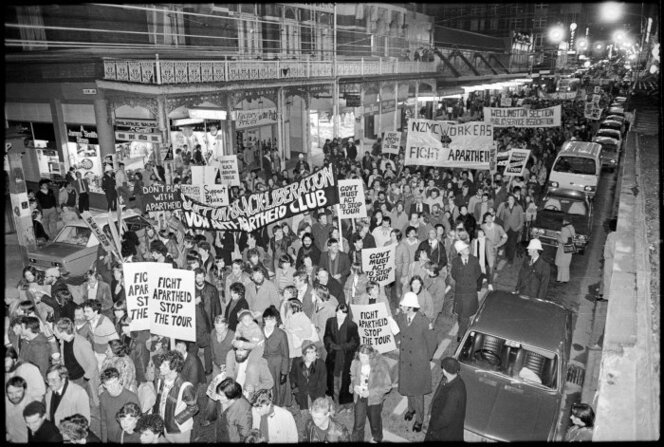

It was to be a special moment in South Africa, but not as expected. Instead of the Springboks vs Waikato game, fans saw 300 protesters linking arms in the middle of Hamilton’s Rugby Park – declaring they would not leave till the tour had been called off.

The anger that swept through white South Africa was nearly as palpable, if not as physical, as the anger expressed on Hamilton’s streets in the ensuing hours.

On South Africa’s Robben Island, Nelson Mandela was spending his 18th year in jail. He said when the prisoners learned that an anti-apartheid protest had stopped the game, they were jubilant. They grabbed the bars of their cell doors and rattled them around the prison; he said it was like the sun came out.

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, the tour protests also had a profound impact, although this took longer to play out. It was the closest we had come to civil war since the 19th century land wars, but more importantly the tour shone a harsh spotlight on racism in this country. Māori activists asked how could we be concerned about racism 10,000km away and ignore it in our own backyard? Fair question.

In the aftermath of the tour, racism took centre stage with an intense public debate that helped set Aotearoa New Zealand on a new path.

A decade earlier, Māori activist groups like Ngā Tamatoa (the young warriors) had challenged the Pākehā (European) majority about patronising attitudes and lazy racism that meant Māori were in effect second-class citizens.

Politicians are slow followers of public opinion, but four years after the tour and the wide discussion and debate it helped spur, the Waitangi Tribunal was given the responsibility to investigate historic breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi – previously the tribunal had only been mandated to look at possible future breaches. And so began its investigations into our history of racism and oppression and the injustices of colonisation, which continue to resonate for Māori in the present.

Since then numerous positive developments have given a stronger political voice to Māori.

In our most recent budget, the health minister, Andrew Little, announced the formation of a national Māori health authority that will have the power to contract health services for Indigenous New Zealanders where the state system has served them poorly. “By Māori, for Māori” is seen as a way to enhance our democracy with a turn away from the “tyranny of the majority”, under which they have fared poorly.

It’s not all plain sailing though, and recent debate about Māori rights to representation on local councils has met hostile, albeit minority, opposition.

But the direction continues to be forward and work is under way to incorporate the history of colonisation in these South Pacific islands into the school curriculum.

The irony in these positive developments is that the overall situation for most Māori is getting worse, with New Zealand’s Indigenous people disproportionately affected by poverty and inequality, which continues to grow relentlessly with the pandemic.

The civil disruption from the tour and the debate that followed benefited both New Zealand and South Africa in ways that we didn’t see at the time. We are a better country for it.

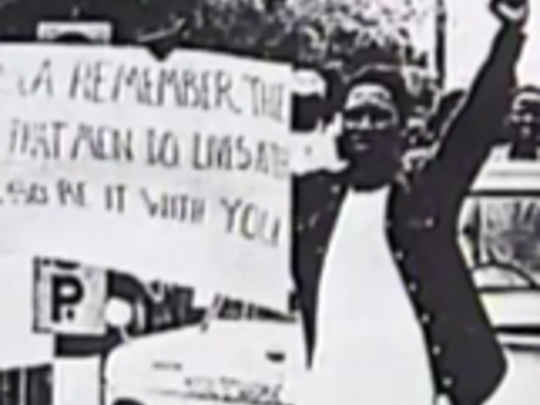

John Minto was national organiser of Halt All Racist Tours (HART) in 1981 and is currently the national chair of Palestine Solidarity Network Aotearoa.

- New Zealand

- Asia Pacific

- Rugby union

Most viewed

1981 South Africa rugby union tour of New Zealand and the United States

From wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour , and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour ) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand. The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour after departing New Zealand. [1] [2]

Apartheid had made South Africa an international pariah , and other countries were strongly discouraged from having sporting contacts with it. Rugby union was (and is) an extremely popular sport in New Zealand, and the South African team known as the Springboks were considered to be New Zealand's most formidable opponents. [3] Therefore, there was a major split in opinion in New Zealand as to whether politics should influence sport in this way and whether the Springboks should be allowed to tour.

Despite the controversy, the New Zealand Rugby Union decided to proceed with the tour. The government of Prime Minister Robert Muldoon was called on to ban it, but decided that commitments under the Gleneagles Agreement did not require the government to prevent the tour, and decided not to interfere due to their public position of "no politics in sport". Major protests ensued, aiming to make clear many New Zealanders' opposition to apartheid and, if possible, to stop the matches taking place. This was successful at two games, but also had the effect of creating a law and order issue: whether a group of protesters could be allowed to prevent a lawful game taking place.

The dispute was similar to that involving Peter Hain in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s, when Hain's Stop the Tour campaign clashed with the more conservative 'Freedom Under Law' movement championed by barrister Francis Bennion . The allegedly excessive police response to the protests also became a focus of controversy. Although the protests were among the most intense in New Zealand's recent history, no deaths or serious injuries resulted.

After the tour, no official sporting contact took place between New Zealand and South Africa until the early 1990s, after apartheid had been abolished. The tour has been said to have led to a decline in the popularity of Rugby Union in New Zealand, until the 1987 Rugby World Cup .

Springbok Tour 1981

A DigitalNZ Story by National Library of New Zealand Topics

Protests against the South African rugby team touring New Zealand divided the country in 1981. Discover the reasons behind this civil disobedience, as well as the demonstrations, police actions and the politics of playing sports. SCIS no. 1809122

social_sciences , english , history

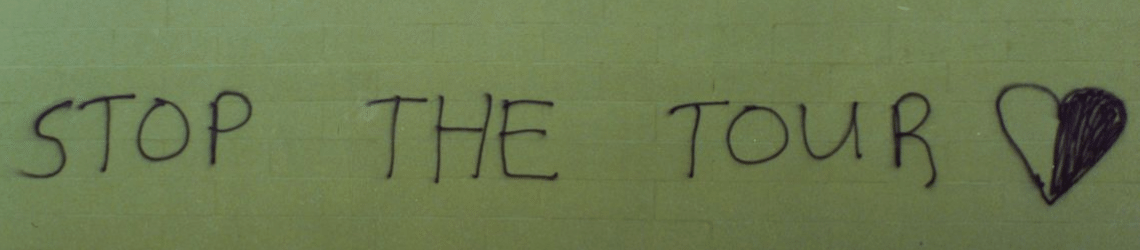

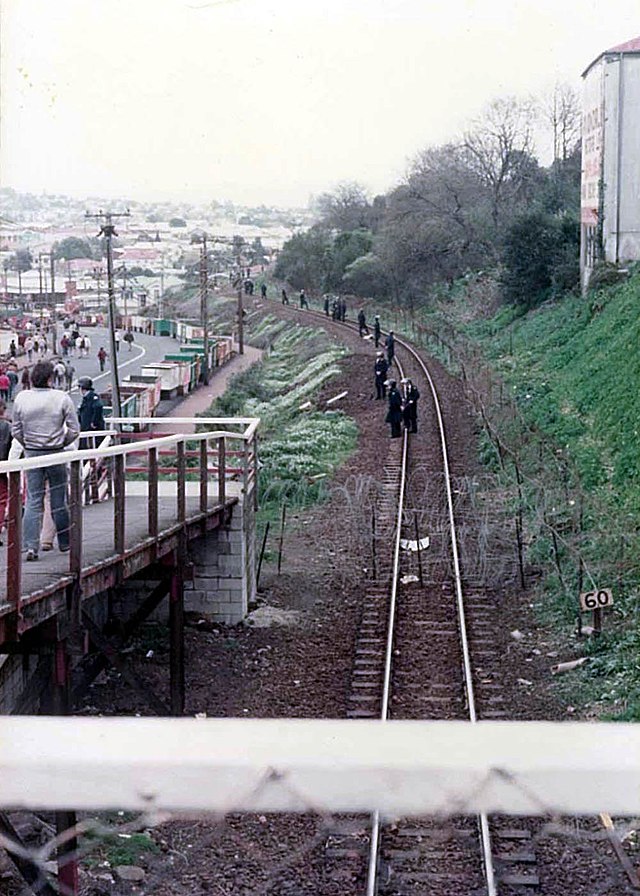

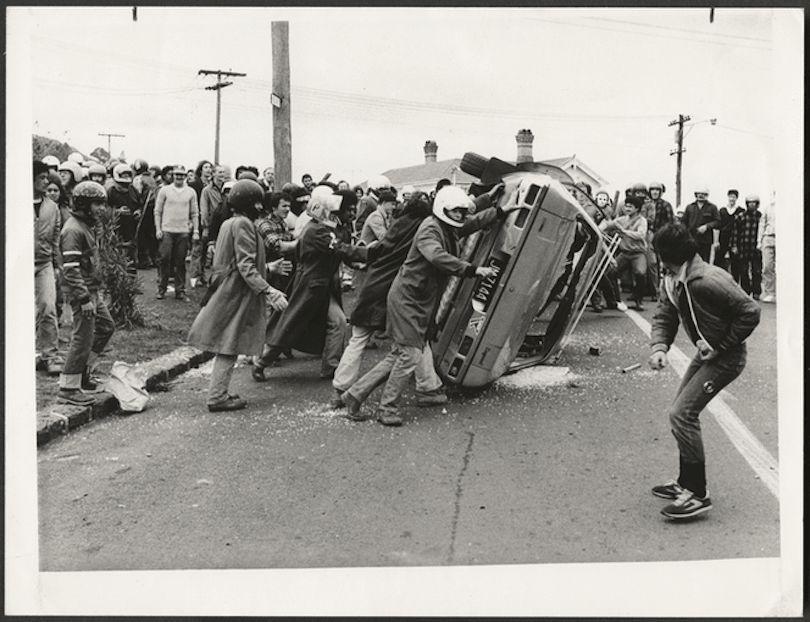

Protesters in Hamilton during a demonstration against the 1981 Springbok tour - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Alexander Turnbull Library

Anti-tour protestors and police in Molesworth Street, Wellington - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

Okay, step forward any lyin' commy…,

Try revolution

This Leanne Pooley-directed film aims to show how the events of the 1981 Springbok tour in Aotearoa played out in South Africa.

NZ On Screen

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Sports and politics

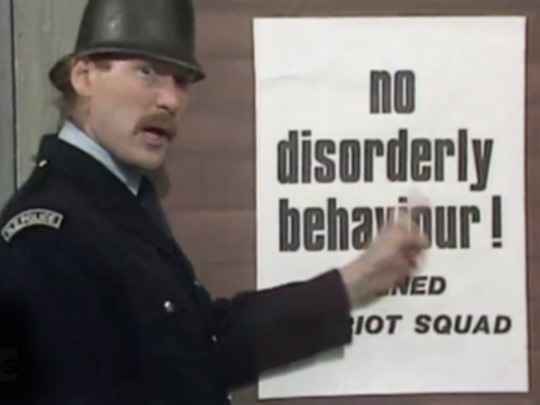

Red Squad and anti- tour demonstrators

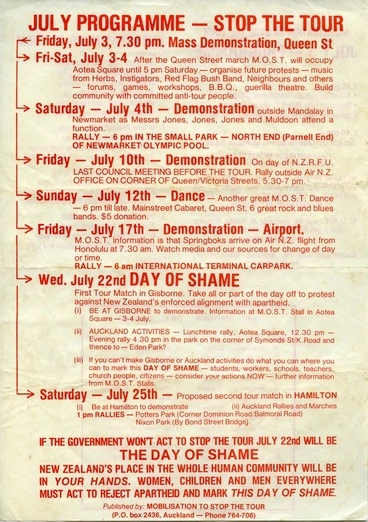

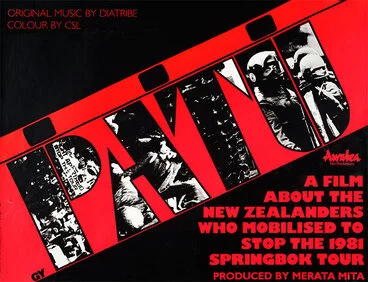

Springbok Tour protest programme

Protest badges - 1981

School children protesting

Young anti-springbok tour protester

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Tour diary - 1981 Springbok tour

Blazey discussing the 1981 springbok tour.

Anti-Springbok tour protest reflects on thirty years since first game

Radio New Zealand

John Miller has documented M¬āori protest since the 1970's, including the Springbok Tour.

T-shirt, 'No Tour'

This T-shirt was made for protestors to wear during the Springbok rugby tour of 1981.

1956 rugby ball and John Minto helmet

Features the protester John Minto's helmet from Springbok rugby tour protests.

Barbed wire barrier protecting a rugby ground from anti-Springbok tour protestors.

TV movie Rage recreates the 1981 Springbok tour, which saw violent clashes between protestors and police.

Patu!, 1983

New Zealand 1981 South Africa 2013

Woman protestor angered by police batoning demonstrators during a Springbok rugby tour protest

These records are part of a July 1981 petition to Robert Muldoon, then-Prime Minister of New Zealand, calling for the Springbok rugby team to be refused entry into the country.

Petition Cards to Robert Muldoon

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

The Year 1981

Release Mandela!

These mugs were sold to raise money for protest funds for the 1981 anti-Springbok Tour movement.

The continuing saga of "The Tour"

Apartheid. Stop the tour

This badge was worn by protesters against contacts between South African and New Zealand sporting teams in the 1970s.

Halt All Racist Tours badge

Services to Schools

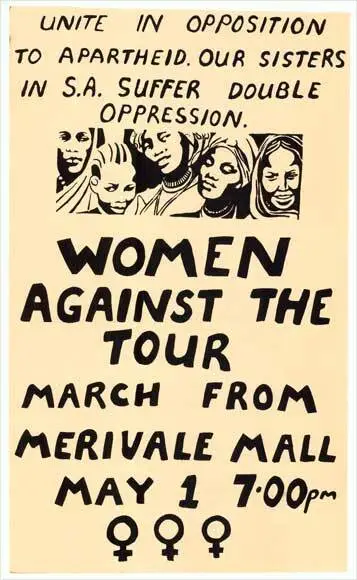

Women against the 1981 tour

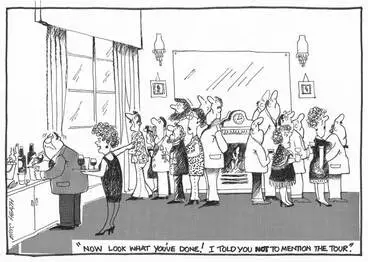

Don't mention the tour

The 1981 springbok tour, the 1981 springbok tour of new zealand, 1981 springbok tour: poster collection, riot 111: 1981, the great divide, the rugby tour that split us into two nations.

PR 24 baton

Rugby and apartheid

1981 Anti-Springbok tour demonstration

The springbok tour of 1981 – 25 years on.

“He aint dead Sir”

Anti-tour clash

1981 Springbok tour

National Library of New Zealand

NZSIS reports on 1981 Springbok rugby tour protests

Red squad revisited, 1981 springbok tour perspectives, the 1981 springbok tour and explosive revelations, tainted games.

1981 Springbok tour images

Research paper

National ideals or national interest: New Zealand and South Africa, 1981 - 1994

Clash on molesworth st, mirror image, artists against the springbok tour, anti-springbok-tour veterans on the power of hart, remembering the 1981 springbok tour, more than just rugby, a tour like no other: school journal year 7: part 04 no. 02: 2011 or, opinion around new zealand on the 1981 springbok tour, rugby, racism and fear, the grassroots of the 1981 springbok tour.

Merata Mita’s Patu! — a landmark in Aotearoa's film history, is based on the civil disobedience movement during the winter of 1981 Springbok tour.

New Zealand Protests

The Dawn Raids

Māori Protests

Covering the springbok tour, 1981 springbok rugby tour — cardboard and clown suits.

NZ Sporting History: The 1981 Springbok Tour

35 years ago: springbok tour protests in wellington, covering the tour, protest - tohe.

New Zealanders protest against Springbok rugby tour, 1981

Time period, location description, methods in 1st segment, methods in 2nd segment, methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, additional methods (timing unknown), segment length, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was organized in New Zealand in 1969 to protest rugby tours to and from South Africa. Their first protest, in 1970, was intended to prevent the All Blacks, New Zealand’s flagship rugby squad, from playing in South Africa, unless the Apartheid regime would accept a mixed-race team. South Africa relented, and an integrated All Black team toured the country.

Two years later, the Springboks arranged a tour of New Zealand. HART held intensive planning meetings, and, after laying out their nonviolent protest strategies to the New Zealand security director, he was forced to recommend to the government that the Springboks not be allowed in the country. Prime Minister Kirk, though he had promised not to interfere with the tour during his election campaign, canceled the Springbok’s visit, citing what he predicted would be the “greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.”

HART remained active in the anti-apartheid community, continuing to protest the Springboks, and helping to organize a boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The International Olympic Committee had not banned New Zealand after the All Blacks had toured South Africa, and many African countries saw this failure as a tacit endorsement of Apartheid. In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand.

The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival – perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in 1972 was. The government officials could not anticipate, however, that the country was about to fall into “near-civil war.” In response to HART, pro-rugby groups like Stop Politics in Rugby (SPIR) organized in an effort to help the Springbok’s tour succeed. Both sides tended to be easily identified by armbands that made their affiliation clear. In particular, HART activists wore their armbands for the entire length of the tour, subjecting themselves to constant ridicule and the threat of violence, despite their commitment to nonviolent protest only.

The Springboks played their first game on July 22 in Gisborne. An anti-Springbok rally took place that day, near the rugby pitch. When the campaigners arrived at the arena, they were confronted by pro-rugby demonstrators. Because Gisborne, like most cities in New Zealand, was close-knit, demonstrators on both sides knew each other, and were not afraid to call each other out for supporting the wrong side, whichever they believed that was. The pro-rugby demonstrators did not restrict themselves to words, even throwing stones at the other side. The anti-Springbok protesters could not stop the match that day. Though they were able to break through the perimeter fence, and engage the pro-tour demonstrators face to face, they were prevented from occupying the field. Though both sides reported that they were uneasy with the clashes between fellow New Zealanders, neither side was easily swayed.

Three days later, the Springboks were scheduled to play in Hamilton. Anti-Springbok planners had circulated a strategy that would hopefully allow them to tear down the fence, invade the field, and disrupt the match. Protesters had also secured more than 200 official tickets to the match, to make sure that their presence was felt, even in the event that they could not storm the pitch. Despite the presence of more than 500 police officers and a sizable pro-rugby contingent, the anti-Springbok march would prove unstoppable. 5000 anti-Springbok protesters descended upon the Hamilton pitch, and more than 300 made it onto the field, forcing a match cancellation. Protesters chanted that the whole world was watching. Many of the demonstrators were arrested, and those on the pitch endured a constant bombardment of bottles and other objects from rugby fans in the stands. This entire situation was captured on live TV and shown around the world.

With tensions in New Zealand reaching astronomical proportions, the Springboks were next scheduled to play four days later, on July 29. The anti-Springbok protesters were largely absent from the match, but had instead planned a march on the South African consulate in Wellington, New Zealand. Despite police declaring that a march was not permitted, the protesters marched right up to the police line on Molesworth Street. The police began to stop the marchers with their batons, violently forcing them away from the consulate building. The marchers, stunned and bloodied, turned towards the police station, chanting “Shame, shame, shame.” When they arrived, the accosted marchers pressed assault charges on the police that had attacked them. Though the charges were dismissed, the policing of the tour protests had taken a turn for the worse. From this point on, protesters were careful to carry shields and wear crash helmets in order to protect themselves from attacks.

Protests would continue for the entire length of the Springbok’s stay in New Zealand. Only one more match was cancelled, in Timaru. However, there were a few more notable encounters. In Christchurch, on August 15, protesters failed to occupy the pitch in time for the game to be cancelled. The police cordon around the arena held, and several observers believe that the police saved the lives of many protesters. The attacks of rugby supporters were growing more and more violent, The Christchurch incident was characterized by flying blocks of cement and full beer bottles. Had the anti-Bok protesters succeeded in reaching the field, the attacks would certainly have been even more dangerous.

The final match of the tour was in Auckland on September 12. Not only was the match important as a final chance for protesters to demonstrate their opposition to the Springboks, it was the deciding third meeting between the Springboks and the All Blacks. Doug Rollerson of the 1981 All Blacks recalled that it seemed very important for the All Blacks to win the match, to show that a mixed team was superior to the segregated Springbok side. When the All Blacks won, the sense of victory in New Zealand was similar to the US victory over the Soviet Union in 1980 – the triumph of righteousness over the evil empire. However, for most observers around the world, the off-field events were far more important. Though the protesters were generally non-violent, there were many others that joined in the marches – HART characterized them as opportunists that simply wanted to fight with police. Though eruptions of violence had taken place throughout the campaign, they were largely viewed by the protesters as third-party actions, and HART consistently distanced themselves from violent attacks. More memorably, Max Jones and Grant Cole commandeered a prop plane, and proceeded to drop flares and flour bombs on the pitch during play in an attempt to stop the game. Though the game continued, the actions of the protesters were again the primary news story in New Zealand and throughout the world.

Though the anti-Springbok protests were largely unsuccessful in that the vast majority of the planned contests took place, they were able to raise an incredible amount of awareness for the anti-Apartheid movement. Nelson Mandela recalled that when the game in Hamilton was cancelled, it was “as if the sun had come out.” HART would continue protesting until the fall of the Apartheid regime.

Influenced and influenced by anti-Springbok protests in other countries like Australia, Britain (see "Australians campaign against South African rugby tour in protest of apartheid, 1971" and "British Citizens Protest South African Sports Tours (Stop the Seventy Tour), 1969-1970") (1,2).

This campaign was also influenced by the New Zealand Waterfront Strike (1951) (1).

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour

Coverage of the game and the protest actions

Collection items

The vault - 1981 springbok rugby tour.

Flour bombs, flares and leaflets were dropped from a low flying Cessna plane which buzzed the third and final game of the 1981 Springbok Tour - dramatic Radio New Zealand coverage of the game and the… Audio

- Download as Ogg

- Download as MP3

- Play Ogg in browser

- Play MP3 in browser

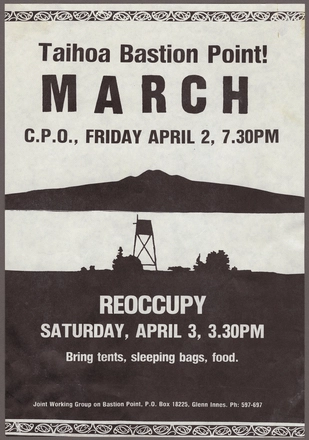

Access All Areas: A Country Divided

The winter of 1981 saw the Springboks rugby team tour New Zealand, and Kiwis divided. Recent Maori attempts to reclaim ownership of government requisitioned land at Bastion Point had focused attention… Audio

This audio is not downloadable due to copyright restrictions.

Anti-tour protestor reflects on thirty years since first game

Thirty years since the first game in the 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand. Audio

Brian Morris remembers the 1981 Springbok Tour

Ngāti Kahungunu Rongowhakaata Brian Morris was a Hawkes-Bay-representative-rugby-playing-school-teacher in 1981 when he made a stand against apartheid and the Springbok tour. He talks about that… Audio

Tom Scott: Rage

Tom Scott is a cartoonist, satirist, author and playwright. His latest project is a television docu-drama centred on the controversial 1981 Sprinkbok tour of New Zealand. Rage is the story of two… Audio

Springbok Tour put NZ Commonwealth Games in danger

Confidential Australian cabinet papers from 30 years ago, which have just been made public, reveal that concern about the 1981 Springbok tour was so high, it jeopardised New Zealand's participation at… Audio

New Zealand As It Might Have Been: Bob Gregory

What would have happened if New Zealand had lost the last test against the Springboks during the troubled tour of 1981? Bob Gregory, a professor of politics at Victoria University of Wellington… Audio

External Links

- The tour on NZ History Online

- The 1981 Springbok tour at Te Papa

- Patu! : Merata Mita’s documentary about the winter of 1981 on NZ On Screen

The Spinoff

Ātea December 28, 2021

Three things you didn’t know about the 1981 springboks tour.

- Share Story

Summer read: This year marked the 40th anniversary of the rugby tour that divided a nation. While countless books and articles have been written about that time, some important details have faded with age. Leonie Hayden looks back at three of them.

First published July 22, 2021

Merata Mita’s documentary Patu! opens with a group collecting signatures on the street in Auckland to petition the government to stop the upcoming Springboks’ tour of New Zealand. A young passer-by starts arguing with the organisers, asking how would they feel if a group of “wogs” or “Blacks” came over here. One group member explains that she’s married to a Black South African man. Undeterred, the man continues his tirade about what would happen if “they” were in charge.

It’s 1981 and Mita’s grainy film footage captures one of those most divisive periods in our history since the New Zealand Wars. It was a battle that played out on the rugby field, in the streets, within the halls of parliament and at kitchen tables all over the country. But the fight for New Zealand to take a stand against South Africa’s apartheid regime was far from new.

The New Zealand Rugby Football Union had left rugby legend George Nēpia and other giants of the game at home in 1928 to conform with South Africa’s segregation laws. In 1959, the Citizens’ All Black Tour Association had tried to demand “No Maoris, no tour” when Māori players were excluded from the team’s 1960 visit. They weren’t successful then, but Māori players would go on to tour South Africa as “honorary whites” in 1970 and then in 1976 – the same year as the Soweto uprising that saw hundreds of children and student protestors murdered by police.

While Robert Muldoon campaigned on sports and politics being kept separate, deftly side-stepping the Commonwealth members’ Gleneagles agreement , the world had very much decided the two were connected. Black African nations boycotted the 1976 Montreal Olympics in protest of our ongoing engagement with South Africa. New Zealand was becoming a pariah.

And so when the 1981 tour was announced, anti-apartheid groups such as Halt All Racist Tours (HART), Citizens Association for Racial Equality (CARE) and the Patu Squad (led by Hone Harawira, Donna Awatere, Josie Keelan and Ripeka Evans) began a national campaign to stop it in its tracks.

Ultimately, the demonstrations and petitions to Muldoon’s government – plus a national poll showing only 46% public support for the tour – fell on deaf ears and the South African team were officially welcomed to New Zealand at Te Poho-o-Rawiri marae in Gisborne on July 19, 1981.

Tā Graham Latimer’s wero

It was a pōwhiri with teeth.

The welcome for the Springboks took place at the same time as Māori activists were spreading glass across Gisborne’s Rugby Park ahead of the first game. The speakers that evening comprised Te Poho-o-Rawiri kaumātua, dignitaries of the Tairāwhiti Māori council, and the president of the New Zealand Māori Council, the late Sir Graham Latimer .

To many the welcome would have looked like a sign of a generational divide – conservative assimilationists on the marae versus activists on the field – but Latimer ensured the pōwhiri wasn’t an occasion that ignored or played down what was at stake. In fact, he very politely told Springboks captain Wynand Claassen and his team they wouldn’t be welcome again while apartheid remained in South Africa.

Per tradition, it was Latimer’s role as the New Zealand Māori Council president to extend a greeting to any international group being welcomed onto a marae. The speaker before him, Tom Fox, had emphasised with some pride, and to much applause, that the Tairāwhiti branch was the only Māori council that actively supported the tour.

Latimer, however, was less effusive. “I am fully conscious of the fact that I do not have a complete mandate to make this welcome,” he began. “Seven out of the nine district councils that make up the New Zealand Māori council are opposed to the tour, and one is undecided.” A long pause, silence from the crowd.

“Fifty-four per cent of the general public of New Zealand has expressed opposition to your tour. That’s in a poll. The last time such a tour was mooted, only 16% were against the tour. That you have come has been seen by some as a major victory but it must be recognised that if there were only another 6% against the tour, there would be neither a political party not a rugby union game enough to extend an invitation to you.”

He continued: “There can be no doubt in my mind that we will not be making another such welcome on a Māori marae – I emphasise that point – unless your government can show it is prepared to change its policies on apartheid. We hope we can look forward to a time in the not too distant future when you could be welcomed on any marae. It would be a pity if this could be looked upon as the last international tour by South Africa.”

Latimer finished by giving an especially warm mihi to Errol Tobias, the first player of colour to tour with the Springboks. “I believe he represents hope for 18 million South Africans, for whom there appears to be little hope.”

The genius of Latimer’s challenge was in its statesmanlike delivery. While much of his speech was received with (presumably) shocked silence, he was still rewarded with a huge round of applause at its conclusion, even though he had just told those gathered they would not be welcome in future under the same circumstances. The extraordinary recording of that evening, housed in the Ngā Taonga archive , captures a mild-mannered assassin executing an entire squad with diplomacy.

Naturally we have no way of measuring the effects of that speech on either the Springboks or apartheid. But it may have been the last time the issue was discussed politely.

Police violence was far worse than they’d like you to remember

Nicknamed the Day of Shame, July 22 saw the Springboks’ opener against Poverty Bay. Three hundred protestors marched to Rugby Park in Gisborne via a nearby golf course and attempted to breach a fence. Rugby fans jumped into action and a brawl broke out between the two groups. Police arrived to break up the fighting, and only two men managed to run onto the field. Thirteen were arrested and many were hurt in the resulting brawl, but it was nothing compared to the violence that was to come.

Over the course of the next two months, police, in particular the infamous Red and Blue riot control squads, would become more and more comfortable with using extreme violence against unarmed protestors, causing serious and sometimes permanent injuries. Pro-tour rugby fans were also brutal in their retaliation.

Singer and journalist Moana Maniapoto, then a first-year law student at the University of Auckland, remembers when the fence came down at the second game in Hamilton on July 25. “Everyone’s leaning on it, pushing and pushing it, and then the next minute the fence came down and you just heard this ‘Run!’ You’re just swept along. So then I’m in the middle thinking, ‘what am I doing here? They’re gonna kill us!'”

She recalls looking up at thousands of angry faces in the stands. “They were totally rabid. Screaming, yelling and throwing cans of beer at us.

“The police arrived, just the ordinary cops, not the Red Squad, and I actually thought, ‘oh this is good, surely they’re not gonna let us get murdered’. Then the commissioner came on and said the match has been called off and there was this huge roar from the crowd. At first it was like, ‘yay!’ and then ‘oh my god. How the hell are we gonna get out of here?’”

Maniapoto, along with land protector Eva Rickard and another friend, managed to escape into the surrounding streets. “The cops were sporadically placed so you had to make a run for it to the gate. Then the cops recognised Eva and they were abusing the shit out of her. But we got out, and we were very lucky, my friend’s father heard on the radio that the match had been cancelled and he circled until he found us. A lot of people got attacked.”

Marx Jones and Grant Cole flour bomb Eden Park in a hired Cessna.

She would go on to attend protests in Rotorua and at the third test in Auckland – the latter resulting in a violent clash between police, protestors and rugby fans on the streets of Mount Eden. “Red Squad came out of nowhere and nutted off at everyone. I was with the least militant bunch when they charged. We were just standing there. Couldn’t believe it. I was batoned, kicked by heavy police boots while on the ground. Shock for a young freshie like me. They just smashed into us and left people lying on the ground in their wake.”

For further proof you need only watch the violence through Mita’s lens. The dull thud of police batons hitting flesh and human skull, and the wails of the injured, some of them young teenagers, is the haunting soundtrack for nearly half the film.

Maniapoto scoffs at the selective memory that it was “New Zealand” who took a stand against apartheid. “It’s held out as a landmark, framing New Zealand as a global social justice advocate. It wasn’t New Zealand; it was people power. It was activists, people from across all walks of life, and there were far fewer of us than there were in the stands.”

She talks abut the Nelson Mandela exhibition hosted at Eden Park in 2019 – a strange venue considering the violence that played out on the surrounding streets 38 years earlier. She says at the launch none of the speakers from the New Zealand Rugby Union came close to admitting they’d been wrong, or offering an apology. Instead everybody spoke proudly about the stand taken by the protestors. Says Maniapoto: “They’re starting to rewrite the history!”

The good bishop saves the Patu Squad

It was at the last test at Eden Park on September 12 that a young Hone Harawira, one of the leaders of the predominantly Māori and Pasifika Patu Squad, was finally caught.

Harawira and a handful of others had been arrested at Waitangi earlier in the year, and although they had been denied bail, they were turfed out of the cells for causing a ruckus and told when to attend their court date. They didn’t show up.

The group had outstanding warrants for their arrest before the tour even began.

“It must have got out to the police that we were all going to be involved in the tour, and one by one we were all picked up. One of the brothers, they got him before it started! So he spent the whole of the tour in Mt Eden,” Harawira chuckles.

Harawira says he was caught early on after the test that ended with Marx Jones’ aerial flour bomb attack , so hadn’t been involved in the upturning of a cop car, or the violence that erupted on an unprecedented scale outside Eden Park. Nevertheless, Harawira was charged with the assault of a police officer who’d had both collar bones broken.

“It wasn’t me but they wanted someone to pin it on so they pinned it on me.”

He says he had seven charges against him. “They were serious charges. Three charges of participating in a riot and four charges of assault with intent to cause grievous bodily harm. Which all carried a total of something like 98 years.”

Justice being neither blind nor in a hurry, Harawira wouldn’t stand trial for another two years, alongside many others who he notes were mostly brown, despite the vast majority of protestors being Pākehā. “Most of them were members of the Patu Squad.”

As he had many times before, Harawira planned to defend himself in court. He’d had University of Auckland law lecturers Jane Kelsey and David Williams to rely on for advice, but this time he wasn’t sure it going to be enough.

“The day before my court date, I’m sitting out the back in the cells thinking ‘jeez, what am I gonna do?’ Then the brain wave came to me. Bishop Desmond Tutu had been invited over by the Anglican church to come and do a speaking tour. Interest was still very high in apartheid South Africa. My mum knew George and Jocelyn Armstrong, who were part of the organisation that brought him over.

“So I rang my mum and said look, I want Bishop Tutu as a witness. She said, ‘He wasn’t there!’. I said, ‘that doesn’t matter! I want him for my witness’. So she said ‘OK when is it?’ And I said ‘Tomorrow! I’m gonna need him by about 10.30.’”

The next day Harawira and 10 others prepared to stand trial.

When the time came for him to give his defence, his star witness wasn’t there. “I read my statement. I’d come to the very end and I was dragging it out. I didn’t want to get out of the dock ‘cos I knew it hadn’t been enough to get me off. Then the door burst open, and someone looked at me with a big smile and just nodded and I knew then. So I asked the judge: ‘Can you please call my witness?’”

Harawira still laughs at the memory of the stunned faces of the judge, prosecution and jury as as the now-Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in his signature dark suit and purple cleric’s shirt, walked into the courtroom.

“And then I’m thinking, ‘What the fuck, now what do I do?’

“So he takes the stand and I go, ‘Could you please tell the court your name?’ And then I said, ‘Can you please tell the court your address?’ And he gave an address in Soweto. Instantly, if the room wasn’t already charged, everyone was completely wide-eyed now.

“And then I said, ‘Can you please explain to the court what apartheid is?’. And away he went. He must have spoken for 20 minutes. It was absolutely stunning. You could have heard a pin drop.”

He says that after Tutu had finished, neither he nor the prosecution could think of any more questions.

“As Bishop Tutu stepped out of the dock, all 11 defendants, we all stood up. Then our lawyers stood up, then the public, the screws from Mount Eden, the police stood up, then the jury stood up. Half of them were in tears. If was one of those moments. I knew right then and there we were gonna get off.” He crows in delight at the memory.

The group were acquitted of all charges.

“It’s kind of hard to believe but it’s all true. Meeting Nelson Mandela himself and going to his tangi, that’s another story.”

We are here thanks to you. The Spinoff’s journalism is funded by its members – click here to learn more about how you can support us from as little as $1.

- Encyclopedia

- Sign in / Register

Comprehensive Collection of Scholarly Articles Millions of reviewed and edited articles in all academic interests

Read online or download and save as eDocuments All articles are Print-on-Demand ready

Largest encyclopedia

The largest and most comprehensive Encyclopedia ever compiled A combined aggregation of about 1,000 article database, over 30,000,000 articles in total

Perfect resource

Beautifully presented and an easy to use interface Share the joy of discovery together Register today your eLibrary Card at no cost to you

Where the World goes to explore...

- Great Artwork

- Science/Astronomy

- Tech/Engineering

- Biology/Medicine

- Philosophy/Thinkers

- Architecture/Civil Planning

- Sports/Athletes

- Entertainers/Performers

Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains

Mount corcoran, the creation of adam, the starry night, dogs playing poker, the garden of earthly delights, the son of man, guernica (picasso), the storm on the sea of galilee, girl with a pearl earring, magnolia and erect rock, pillars of creation, mystic mountain, solar flare, hubble space telescope, crab nebula, parkes observatory, dark nebula, solar flare, stationary steam engine, international space station, kismet (robot), national ignition facility, printing press, ford model t, wright flyer, rocketdyne f-1, soyuz tma-14m, large hadron collider, escherichia coli, vibrio cholerae, polio vaccine, cell (biology), cough medicine, mitochondrion, unicellular organism, ogataea polymorpha, mahatma gandhi, gautama buddha, friedrich nietzsche, immanuel kant, sigmund freud, thomas hobbes, florence cathedral, palace of westminster, national congress of brazil, sydney opera house, notre dame de paris, villa capra "la rotonda", palais garnier, falling water, palm jumeirah, ailson brites, randy couture, muhammad ali, michael jordan, roberto clemente, serena williams, tiger woods, michael phelps, dale earnhardt jr., the beatles, carlos santana, steven tyler, elvis presley, frank sinatra, earth, wind & fire, boyz ii men, mark anthony, christina aguilera.

World Heritage Encyclopedia The World Heritage Encyclopedia is the largest and most comprehensive Encyclopedia ever compiled. The combination of articles, dictionary, eBooks, journals, and primary source documents, offers a most unique resource for students and researchers. A combined aggregation of hundreds of article databases, with millions of articles in total. All the articles may be read online or download and save as eDocuments. All articles are Print-on-Demand ready. World Heritage Encyclopedia believes the Common Core Standards are important, and that is why at WorldHeritage.org you'll find tools to help improve student performance, strengthen instructional effectiveness, and maximize the use of your technology. World Heritage Encyclopedia supports learning for all grade levels, from K-12, with a user-friendly interface and grade appropriate content. World Heritage Encyclopedia has aligned itself with the Common Core and State Standards to ensure all of the nonfiction STEM content needed by any student could be found, all in one place. Every month thousands of new articles, images, and multimedia elements are added.

Why Encyclopedias The World Heritage Encyclopedia includes the great general encyclopedias of the past and the present but all types of works that claim to provide in an orderly arrangement the essence of "all that is known" on a subject or a group of subjects, translated from the Koine Greek enkyklios paideia, which literally means "complete knowledge". As French philosopher, and contributor of the Encyclopedie Denis Diderot, said "Indeed, the purpose of an encyclopedia is to collect knowledge disseminated around the globe; to set forth its general system to the men with whom we live, and transmit it to those who will come after us, so that the work of preceding centuries will not become useless to the centuries to come; and so that our offspring, becoming better instructed, will at the same time become more virtuous and happy, and that we should not die without having rendered a service to the human race. "

Accessibility World Heritage Encyclopedia, (WorldHeritage.org) is a live collaboration differing from paper-based reference sources in important ways. Unlike printed encyclopedias, we are continually editing, updating, and appending, articles on historic events appearing within minutes, rather than months or years. WorldHeritage.org is fully accessible on a tablet, smartphone, laptop, desktop computer, or any Internet-connected device with a Web browser.

Is Print Obsolete? "Thinking beyond the format", Encyclopedias join a long list of paper we once thought we couldn't live without, like the Sears catalog, Yellow Pages and maps. Even the world famous Encyclopedia Britannica will no longer be printed after 244 years, the final edition costing almost $1400. Today, the modern encyclopedia is often in electronic form and much more affordable then the traditional paper versions. Unlike many online encyclopedias, World Heritage Encyclopedia is an aggregation of professionally written, crowd sourced, peer reviewed, and edited articles, making our information the most reliable and complete encyclopedia. On-line encyclopedias offer the additional advantage of being dynamic; new information can be presented almost immediately as it is happening in the world. With modern technology we have the extra advantage of information being portable as well.

- Explore Tūhura

- Collections Ngā Kohinga

- Interviews Ngā Uiuinga

- Profiles Ngā Tāngata

- Watch list Rārangi Mātakitaki

We're sorry, but something went wrong

Please try reloading the page

We're sorry, but your browser is unable to play this video content.

If this continues please try upgrading your browser or contact us for assistance.

We're sorry, but this video is currently unavailable on mobile.

Part one of two excerpts from this television programme

Part two of two excerpts from this television programme

1981 - A Country at War

Television (excerpts) – 2000.

- Related videos

The New Zealand Government's decision to proceed with a controversial Springbok rugby tour in 1981 tore open cultural and political rifts within Kiwi society. In these two documentary excerpts, New Zealanders on both sides of the divide give firsthand accounts of the bloody aftermath of matches in Gisborne, Hamilton and Auckland. The protests enraged rugby fans, and for police officers like Tyrone Laurenson, the events of 1981 were a matter of personal survival. For Māori protestors, the tour provoked serious questions about racism at home in Aotearoa.

It was like trench warfare; I suddenly realised that everything had changed... – Journalist Bill Ralston on witnessing the first Springbok match in 1981

Key Cast & Crew

Geoff Steven

Executive Producer

Owen Hughes

Bill Ralston

Rachel Jean

Producer, Director

John Sumner

Robyn Grace

Production Manager

Produced by

Frame Up Films

Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision - TVNZ Collection

- ake ake ake

- allan hewson

Documentary

More Information

NZ History page on the 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand

Springbok tour police officer Tyrone Laurenson breaks his silence, The NZ Herald, August 2001

Remembering the 1981 tour, The Southland Times, August 2011

More from The Protest Collection ...

Merata Mita’s Patu! is a startling...

This 1997 Inside New Zealand documentary...

Children of the Revolution

This documentary explores the 1970s/80s protest...

The Taranaki village of...

In 1951, New Zealand temporarily became a police...

Ngā Tamatoa: 40 Years On

Actor Rawiri Paratene was 16 years old when he joined...

Polynesian Panthers

In the 1950s thousands of Pacific Islanders came to...

French Letter '95

In this video, languid Pacific Island imagery (poi,...

Amidst a tale of despair in the city, a staunch 'no...

Bastion Point - The Untold Story

In 1977 protesters occupied Bastion Point, after the...

One Network News - Protest (2 January 1995)

Television news becomes the news in this brief report...

Revolution - 1, Fortress New Zealand

Documentary series Revolution mapped the...

In the tradition of novelty songs,...

Try Revolution

Some argue that if the 1981 Springbok rugby tour of...

Nuclear Waste

Herbs released this...

Tame Iti - The Man Behind the Moko

This documentary presents insight into the man most...

Don't Go

In the vein of 'We are the World' and 'Do They Know...

This all star cover of Mutton Birds classic...

Syd Jackson: Life and Times of a Fully Fledged Activist

As Syd Jackson’s daughter Ramari puts...

TV movie Rage recreates the 1981...

I Care Campaign - John Hanlon

In early 1974, NZ had more than just the Commonwealth...

This song is from New Zealand’s troubled winter...

I Am the River

The Garlick Thrust

Young Geoff Garlick reckons he's developed a...

Rangatira: In the Blood / He Toto i Tuku iho - Donna Awatere Huata

This edition of the Rangatira series...

'Azania' is an impassioned anti-apartheid song written...

Land of a Thousand Lovers

In 1885 the NZ Government used legislation to take...

Mururoa 1973

In 1973 Alister Barry joined the crew of a protest...

All Blacks for Africa - A Black and White Issue

This 1992 TV One documentary follows the All Blacks on...

There is No Depression in New Zealand

This track by Auckland post-punk trio Blam Blam Blam...

The New Zealand Government's decision to proceed with...

This militant debut from Upper Hutt Posse marked...

E Tū (Te Reo Māori Remix)

Album Te Reo: Remixes (2002)...

Gallery - Mururoa protest interview with Bill Ralston

In this short Gallery interview...

Loose Enz - The Protesters

The powerhouse, largely Māori cast of this teleplay...

Freedom to Sing

In April 2011, singer Tiki Taane was handcuffed,...

Pacific 3-2-1-Zero

Pacific 3-2-1-Zero is a record of a...

Share this video

- Embed this video

- Badge this video

Which size would you like?

Copy this code and paste it into your website.

Which clip would you like to embed?

Start clip at:

Beginning This time: eg. 1m7s

At end of clip:

Continue to next clip Stop playing

Would you like the clip to be a fixed size or responsive?

<!-- Start NZ On Screen - 1981 - A Country at War - Clip: 1981 - A Country At War (clip 1) Size: 585 by 410 --> <iframe width=" 585 " height=" 410 " style="width: 585px " src=" https://www.nzonscreen.com/embed/ca905f85ced3675a " frameborder="0" allowfullscreen ></iframe> <!-- End NZ On Screen - 1981 - A Country at War - Clip: 1981 - A Country At War (clip 1) -->

<!-- Start NZ On Screen - 1981 - A Country at War - Clip: 1981 - A Country At War (clip 2) Size: 585 by 410 --> <iframe width=" 585 " height=" 410 " style="width: 585px " src=" https://www.nzonscreen.com/embed/a4120c4cb8b690bc " frameborder="0" allowfullscreen ></iframe> <!-- End NZ On Screen - 1981 - A Country at War - Clip: 1981 - A Country At War (clip 2) -->

Don't have an account? Create an account here

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit http://www.djreprints.com.

https://www.barrons.com/news/riots-barbed-wire-s-africa-s-stormy-1981-rugby-tour-of-new-zealand-b34eb476

- FROM AFP NEWS

Riots, Barbed Wire: S.Africa's Stormy 1981 Rugby Tour Of New Zealand

- Order Reprints

- Print Article

All Blacks fans will gather to watch the World Cup final against the Springboks on Saturday, but there was a time when their rugby team's links to apartheid-era South Africa bitterly divided New Zealanders.

The Springboks' 1981 tour of New Zealand was blighted by violent protests.

The rugby-mad host nation was split by New Zealand rugby's insistence on maintaining ties with South Africa's apartheid regime while other countries supported a sporting boycott.

The flashpoint came soon after the Springboks arrived.

There were bloody scenes as pitched street battles erupted between protestors and police, rocking the normally peaceful nation.

Lines were drawn between New Zealanders who were either eager to see their heroes face the Springboks or vehemently opposed to the tour.

"It split the country, you were either for or against it -- there was no middle ground," former All Blacks winger Stu Wilson, 69, told AFP.

The presence of the South Africa team divided many New Zealand households, including his own.

"My wife at the time was protesting against them and I was playing them. It was quite unusual," recalled Wilson, who was 27 at the time.

"She didn't try to talk me out of it. She had her views and I had mine."

The All Blacks now regularly play South Africa, but in 1981, it had been 16 years since the Springboks had previously visited New Zealand.

"I was pretty happy that they toured. I had no problems playing, but a couple of my mates did," Wilson said, referring to then All Blacks' captain Graham Mourie and star centre Bruce Robertson, who both declined to play the South Africans on political grounds.

"A lot of us had never had the chance to play the Springboks, let alone try and win a series against them."

While Wilson and his team-mates were trying to beat the Springboks on the field, anti-apartheid protestors were doing their best to halt the tour.

A violent edge developed after the second match of the tour was cancelled when protestors linked arms on the pitch in Hamilton.

"We weren't going out to just hold banners and protest, we were going to try and stop the tour," John Minto, the national leader of the protest group HART (Halt All Racist Tours) in 1981, told AFP.

"The country was certainly the most divided that I've ever seen with strong emotions on both sides and a lot of violence."

Minto was among the protestors who forced the game in Hamilton to be cancelled, amid angry scenes.

"I got injured many times during the tour, but ended up in hospital twice in Hamilton that night for stitches," he said, having been repeatedly struck by objects thrown from furious rugby fans.

Minto, now 70, was unaware what impact the abandoned match would have. "We were chanting 'the whole world's watching' - hoping like hell that they were."

Years later, Minto learned the news had reached the prison cell of Nelson Mandela, jailed in South Africa at the time as an anti-apartheid activist, but who united the nation as president after his release.

Mandela, who died in 2013, met Minto on a visit to New Zealand in 1995.

"Mandela told me that when they heard that the game had been stopped by a protest, the prisoners rattled their cell doors to celebrate," Minto added. "He said it was like the sun came out."

In the wake of the abandoned game in Hamilton, New Zealand police responded with increasingly rough tactics, staging baton charges on crowds of demonstrators outside parliament in Wellington in what became known as "The Battle of Molesworth Street".

Protestors in turn became more radical, arming themselves with clubs and bats, while donning motorcycle helmets and makeshift body armour.

Tensions reached fever pitch before the decisive third and final Test at Auckland's Eden Park.

The ground was ringed with barbed wire as more than 2,100 police -- 40 percent of the entire national force -- faced off against crowds of protestors in the streets.

During the match, protestors flew with a single-engine plane over the pitch and dropped flour-bombs, one of which felled All Blacks prop Gary Knight.

"A flour bomb knocked out Gary -- our biggest, strongest man," said Wilson. "If it had hit anyone else, it probably would have killed them."

At one point, Wilson tackled an opponent, only to discover several fish hooks, thrown onto the pitch by protestors, had stabbed his leg.

He scored a try in a nail-biting 25-22 victory. Wilson remembers the relief when a late penalty by New Zealand full-back Allan Hewson sailed between the posts to seal a 2-1 series win.

"We knew if we lost, and with the country already divided, then that was going to be worse, so it motivated us to put these guys away and try to repair the damage the tour had done," said Wilson.

Outside the ground, fighting erupted as protestors clashed with police.

"We waited three or four hours for the fans to disperse and the protestors to go. We left in a bus, heading to the hotel and there were cars burnt out. It was like a war zone"

The divisions caused by New Zealand rugby's stance took time to heal and damaged the game's standing among Kiwis.

"The sad thing is, it took years to recover, the country was a bit battered after the tour," said Wilson.

When New Zealand hosted the inaugural Rugby World Cup in 1987, then prime minister David Lange was still so disillusioned with the sport that he refused to attend.

"Looking back, we were attacking the central pillar of New Zealand cultural life, which was rugby," said Minto.

"It was New Zealand's most important link with South Africa. The country polarised dramatically and quickly."

Riots, Barbed Wire: S.Africa's Stormy 1981 Rugby Tour Of New Zealand

All Blacks fans will gather to watch the World Cup final against the Springboks on Saturday, but there was a time when their rugby team's links to apartheid-era South Africa bitterly divided New Zealanders.

An error has occurred, please try again later.

This article has been sent to

- Cryptocurrencies

- Stock Picks

- Barron's Live

- Barron's Stock Screen

- Personal Finance

- Advisor Directory

Memberships

- Subscribe to Barron's

- Saved Articles

- Newsletters

- Video Center

Customer Service

- Customer Center

- The Wall Street Journal

- MarketWatch

- Investor's Business Daily

- Mansion Global

- Financial News London

For Business

- Corporate Subscriptions

For Education

- Investing in Education

For Advertisers

- Press & Media Inquiries

- Advertising

- Subscriber Benefits

- Manage Notifications

- Manage Alerts

About Barron's

- Live Events

Copyright ©2024 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law. For non-personal use or to order multiple copies, please contact Dow Jones Reprints at 1-800-843-0008 or visit www.djreprints.com.

True Crime New Zealand (NZ)

A nz crime podcast, history iv: 1981 springbok rugby tour (part ii).

22nd July 1981. The Springboks began the journey down the east coast of New Zealand and found their way to Gisborne . The Springboks were to play Poverty Bay (a small bay near Gisborne) for their first game in NZ.

To enter Rugby Park (where the game was being played) , spectators had to agree to be searched upon entry. Items such as banners, placards, flags, poles, fireworks, or “any article that might impede the match” were banned.

As the game kicked off, over 300 anti-apartheid protesters marched across the neighbouring golf course to reach Rugby Park . A wire fence separated folk watching the game with barbed wire topping it and a line of police officers attempting to keep the peace.

Visit www.truecrimenz.com for more information on this case including sources and credits.

Hosted by Jessica Rust

Written and edited by Sirius Rust

Music sourced from:

“Day of Chaos” Kevin MacLeod ( incompetech.com ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“Beauty Flow” Kevin MacLeod ( incompetech.com ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“Leaving Home” Kevin MacLeod ( incompetech.com ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“Floating Cities” Kevin MacLeod ( incompetech.com ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“Crypto” Kevin MacLeod ( incompetech.com ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“Over Under” Kevin MacLeod ( incompetech.com ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“Spacial Harvest” Kevin MacLeod ( incompetech.com ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“Snowfall” Punch Deck ( https://soundcloud.com/punch-deck/snowfall ) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The podcast version is the intended way to consume this story but we make a transcript available for those that would rather read instead. This can be found below.

HISTORY IV: 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour (PART II)

Chapter iv: we want rugby.

To enter Rugby Park (where the game was being played) , spectators had to agree to be searched upon entry. Items such as banners, placards, flags, poles, fireworks, or “any article that might impede the match” were banned.

The anti-apartheid demonstrators broke through the police barricade and dashed to the fence standing between them and the rugby game. The protesters arrived at the gate and began tearing down the fenceline.

Those watching the game turned to see this and began exchanging blows with their fellow NZers on the other side of the fence. Police tried to maintain order but the protesters continued tearing down the fence. Eventually, the approximately 60 police officers linked arms and pushed the protesters back around 25 metres.

More, smaller assaults continued, as the protesters attempted to break the police line but were unsuccessful. Ultimately, 13 people are arrested in the chaos and two were taken to the hospital.

The rugby match between the Springboks and Poverty Bay was played, unmolested, and the South Africans won 24 to 6 .

25th July 1981. Three days after the Gisborne game, the Springboks travelled to Hamilton to play the Waikato rugby team . However, before the game, over 2,000 anti-apartheid protesters marched to Rugby Park (now Waikato Stadium ) .

The protesters found their way to the park’s perimeter fence, where they encountered angry Waikato rugby fans inside the grounds. A short standoff ensued before the protesters darted at the wire fence and began tearing it down. The ‘flimsy’ barrier came down relatively effortlessly before approximately 500 protesters raced into the grounds, fighting off furious rugby supporters as they did so.

The protesters smashed their way inside and eventually onto the rugby pitch. In the middle of the pitch, the demonstrators linked arms and created a tightly packed mass. This drama was being broadcast countrywide, and worldwide, including in South Africa .

At this time, three lines of police carrying riot shields and batons marched onto the pitch to confront the protesters. The protesters fought off the police and angry rugby fans, although some were taken and arrested by police. After being confronted with the scale of violence, some of the protesters left voluntarily but approx. 250 protesters remained huddled on the pitch, arms linked.

Earlier that afternoon of the 25th of July 1981 , a former World War II Spitfire pilot Pat McQuarrie stole a Cessna 172 (an American four-seat, single-engine, high wing, fixed-wing aircraft) from a Taupo airfield. There was some confusion about Pat’s intentions with the plane but police were concerned he was heading to Hamiton and planned on disrupting the game or perhaps even crashing the plane into the grandstand.

The fear of escalating carnage led to the announcement that the game was cancelled. “ WE WANT RUGBY! WE WANT RUGBY!”, the 30,000 -strong crowd screamed after the announcement was made. The angry rugby fan’s aggression was taken out on the 200+ protesters still standing in the middle of the field. Bottles, boots, cans, anything throwable, was hurled at the protesters as the police turned from pursuing the demonstrators to protecting them.

The police attempted to usher the protesters from the pitch as furious fans continued to pour down fire on them. The police eventually got the protesters out of the grounds, although twenty-three people, including one police officer, had to be treated in Waikato Hospital for injuries sustained in the attacks.

Ultimately , over 73 people were arrested and the pilot Pat McQuarrie landed safely at the Morrinsville Horse Track where he was arrested.

The level of anger from the pro-tour supporters at the game being cancelled is exemplified by the 25th of July 2021 article in The Waikato Times dubbed ‘1981 Springbok Tour 40 years on: How Hamilton became a city of rage’ where they describe the ongoing violence spreading throughout the city; pro-tour folk vs. anti-tour folk . The Halt All Racist Tour headquarters in Hamiton was broken into, and the Waikato University halls of residence windows were smashed in.

The Waikato Times even detailed in the same article receiving a call from someone in South Africa furious they couldn’t watch the game. The person told the newspaper, “I saw about 250 people prevent thousands from watching a game of rugby… Why didn’t they shoot a few? That’s what we would have done. ”

CHAPTER V: EMOTION AND ADRENALINE

New plymouth .

On the 29th of July 1981, four days after the cancelled Hamilton game, the Springboks travelled to New Plymouth to play the Taranaki rugby team . Graham Mourie , a team member for Taranaki and a captain of the All Blacks , refused to play in the game in solidarity with the anti-apartheid movement.

Around 200 people marched in New Plymouth to protest the Springboks and the tour. However, little drama came from the protesters, and the game took place securely; South Africa once again secured the victory, winning 34 to 9 .

After the New Plymouth game ended, a considerable protest of around 2,000 people began to heat up on Molesworth Street (near Parliament buildings) in Wellington . The anti-apartheid protesters were marching toward the South African Consulate . As the protesters got closer to their destination, a string of police appeared wearing riot gear and carrying batons. The following is a first-hand account by Rona Bailey (at the time a woman in her sixties) of what happened next, detailed in the 1983 book By Batons and Barbed Wire authored by Tom Newnham , “The police were moving in on us at the side, flailing out viciously in all directions with their short batons. I caught a baton across the side of my head, not with full force, probably because I had slipped down and was almost on my knees at the time. The girl on my left caught the full force of the batons twice. I fell to the ground and people dragged me out – I can’t really remember after that”.

The Molesworth Street protests were eventually pushed back and disbanded. This marked the first time that police used violence to repel the anti-apartheid protesters .

PALMERSTON NORTH

On the 1st of August 1981, the Springboks travelled to Palmerston North to play the Manawatu side. Over 5,000 anti-apartheid protesters met at Rangitikei Street before marching along Cuba Street , chanting “Remember Steve Biko … Remember Soweto… Remember Nelson Mandela ”.

Steve Biko was a South African anti-apartheid activist who was arrested in 1977 and beaten by South African security officers. The result of the beatings led to extensive head injuries which eventually became a brain haemorrhage. Steve Biko died from these injuries on the 12th of September 1977.

Soweto is a township in the city of Johannesburg in South Africa. In 1976 , students at the Soweto High School walked out in protest of the Afrikaans Medium Decree which forced black students to use an even balance of English and the Afrikaans language in school. This was controversial due to Afrikaans (as it is viewed as a derivative of Dutch ) being seen as the “language of the oppressor” .

On the morning of the 16th of June 1976, somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000 black students walked out of their schools in Soweto and attempted to occupy the nearby Orlando Stadium (a stadium predominantly used for soccer games) .

Ultimately, 1,500 heavily-armed police officers were deployed to Soweto by the South African government to shut down the protest. The official number of students killed is given at 176 , but it is estimated up to 700 may have been killed in the uprising; with over 1,000 wounded.

Back in ‘Palmy’ , the protesters continued their march. They were marching down Cuba Street on their way to the Palmerston North Showgrounds (now the Central Energy Trust Arena ).

As they got closer to the showgrounds, the marchers, some of whom were wearing crash helmets and rugby padding due to the increased police brutality, were greeted by a force of 1,000 law enforcement (approx. 20% of the nation’s total police force) . The officers donned riot gear and long batons and began pacing forward in formation.

The anti-apartheid protesters felt there was no path forward and retreated for safer grounds. The rugby game went ahead and the Springboks beat the Manawatu team 31 to 19.

On the 5th of August 1981, the Springboks travelled to Wanganui . About 100 protesters stood outside Spriggins Park (where the game was being played) shouting and waving placards.

The protesters were greatly outnumbered by those attending the game. And apart from a few verbal fisticuffs, the game went ahead with little drama. The Springboks beat the Wanganui rugby side 45 to 9 .

INVERCARGILL

The Springboks travelled down the country to the ‘deep south’ to compete against the Southland team. The game was to be played at Rugby Park in Invercargill . Before the match, the NZ Army was called in to erect a barbed wire barricade between the crowds and the pitch to impede the protesters.

The game was to be played on the 8th of August 1981. Approximately 350 people showed up to march against the match going ahead, however, they were outnumbered by a heavy police presence. When the protesters came within 200m of Rugby Park, they were greeted by two lines of police in riot gear and carrying batons.

Police even had a large presence within Rugby Park, a line of police stood on the sidelines of the pitch (behind the barbed wire barricade) staring into the crowd. The heavy police presence created a new protest chant, “Two-Four-Six-Eight – Racist Tour – Police State”.

The rugby game went ahead unmolested, and the Springboks beat Southland 22 to 6 .

On the 11th of August 1981, the Springboks travelled to Dunedin to play the Otago side at Carisbrook (known locally as The House of Pain ) . 1,200 anti-tour protesters marched along the Southern Motorway which overlooked Carisbrook. As they got closer, the protesters once again were met with rows of police in riot gear.

One of the officers present was Constable Grindell , who detailed their experience in the 31st of July 2021 edition of the Otago Daily Times , for the article ‘Battling the Boks’ . Grindell told the newspaper that there was no violence but, “There was a wee bit of name-calling… It was worse for the Maori policemen. The young Maori cops were getting called traitors. They particularly took a lot of stick.”

After this, the protest split into two camps. One camp of around 600 people entered the city to participate in a silent protest. The other made their way to the Southern Cross Hotel where the Springbok team had been staying, an approximately half an hour journey north to await the Springboks’ return. The hotel had a heavy police presence and the protesters were instructed to disperse but instead, the 300 or so group sat on the footpath, refusing to leave.

24-year-old Francesca Holloway was one of the protesters that day. She detailed her experience to the Otago Daily Times for the same article, “While I was living in Dunedin in the lead-up to [the] events I received telephoned death threats and all sorts of threats being made which were fairly unsettling… Walking away from [the protest] later on, I was assaulted by some people who were absolutely furious that people in Dunedin had dared to express their opinion against the tour. It was a very messy, difficult day. It was very intense, with a lot of people trying to stay calm while dealing with a lot of emotion and adrenaline surges.”

At The House of Pain, the game had begun. A small group of 27 protesters snuck their way into the grounds. They began chanting and blowing whistles but were quickly apprehended by police and arrested.

Nevertheless, the rugby game went ahead unthreatened, and in the closest game yet, the Springboks narrowly beat the Otago side by 17 to 13.

CHAPTER VI: WHY ARE WE BEING SACRIFICED?

Christchurch.

On the 15th of August 1981, the Springboks arrived in Christchurch for the first test match against the All Blacks . Police presence and security were at an all-time high, as tensions had been escalating in Christchurch for the past week.

A shop that had an anti-apartheid poster on the window was smashed on the 8th of August .

On the 11th of August , 126 anti-tour demonstrators were arrested when they protested by blocking an intersection.

On the 12th of August, Prime Minister Robert Muldoon ‘stoked the flames’ when he compared the anti-tour protesters to Nazis , “when the Fascists broke into the offices of other political parties, ransacked them, threw the papers out the window, burnt them, did their best to stop free speech as [the anti-tour protesters] did at the National Party conference in this country during the weekend before last”.

In the early morning hours of the 14th of August, an explosion of a container of sand was set off outside of Lancaster Park (the stadium the rugby test was to be played in) . The same day, the Springboks snuck into the city on an unscheduled Boeing 737 with a heavy police escort.

Back on the 15th of August, a large protest of approximately 6,000 people congregated at Cathedral Square. They began moving toward Lancaster Park. As they got closer they are met with six rows of police in riot gear with batons.

The police confront the protesters and violence broke out. Ultimately, the police hold the line and 27 people were arrested. 11 people were taken to the hospital including an older man who had his teeth knocked out, as well as two police officers.

Ten minutes before kick-off, 60 protesters make their way into the stadium and onto the pitch, however, only 30 of those make it past the police line and barbed wire. The police push the 30 protesters back, to a large cheer from the crowd. Police said later that the protesters scattered fishhooks and broken glass on the field to stop the game.

The game went ahead largely unabated, and the All Blacks took the victory 14 to 9.

The Springboks were supposed to play the South Canterbury team on the 19th of August 1981 in Timaru but the match was cancelled on the 7th of August , citing “security concerns” .

It is likely the Timaru match was cancelled due to the ballooning police budget and to give the officers rest after the first test in Christchurch. Approximately 40% of the entire nation’s police force was being used for ‘Operation Rugby’ and an estimated 15 million dollars (approx. 69 million in 2022 dollars) was spent on policing during the 56-day tour.

It would seem many in Timaru were upset about the cancellation, as The Timaru Herald ran an editorial headline on the 10th of August 1981 reading ‘Why are we being sacrificed?’ . The editorial opens with the paragraph, “ Everyone in South Canterbury has cause for anger at the cancellation of the Springboks game, irrespective of his or her views for or against the tour. What other reaction is reasonable in response to an unexplained slap in the face?”

On the 20th of August 1981, the Springboks arrived in the city of Nelson to play Nelson Bays in their final match on the South Island . There was controversy immediately as the Mayor of Nelson, Peter Malone , welcomed the Springboks to the city in an official ceremony the next day on the 21st of August. Controversially, the only Mayor of NZ to officially do this on the tour.

This was seen by those against the tour as a pro-apartheid action. However, Mayor Malone told the locals that the welcome was only in the tradition of extending courtesy to all visitors to Nelson.