An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc

- v.2022; 2022

Predicting Avoidable Emergency Department Visits Using the NHAMCS Dataset

Yuyang yang.

1-6 Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

Hanyin Wang

Scott dresden.

Despite the important role avoidable emergency department (ED) visits play in healthcare costs and quality of care, there has been little work in development of predictive models to identify patients likely to present with an avoidable ED visit. We use a conservative definition of ‘avoidable’ ED visits defined as visits that do not require diagnostic or screening services, procedures, or medications, and were discharged home to classify visits as avoidable. Models trained using data from emergency departments across the US yielded a training AUC of 0.723 and a testing AUC of 0.703. Models trained using the full dataset were tested on demographic groups (race, gender, insurance status), finding comparable performance between white/black patients and male/female with reductions in performance in Hispanic populations and patients with Medicaid. Predictors strongly associated with non-avoidable ED visits included increased age, increasing number of total chronic diseases, and general as well as digestive symptoms. Reasons for visit stated as injuries and psychiatric symptoms influenced the model to predict an avoidable visit.

Introduction

Avoidable emergency department (ED) visits put significant strain on the healthcare system by increasing overall cost and leading to ED overcrowding 1 , 2 . This problem has received more attention in the US in recent years due to significant increases in annual ED visits and reductions in ED admission rates among the elderly, the Medicare-reimbursed, and patients with multiple comorbidities 3 . Previous studies suggest that diverting ED visits for nonurgent conditions that are treatable at retail clinics or urgent care facilities may lead to a projected saving of $4.4 billion annually 4 . Avoidable ED visits are also believed to compromise quality of care by contributing to excessive testing and treatment as well as compromising the longitudinal relationship between the patients and the primary care physicians 2 , 5 . Yet despite the heightened interest in reducing potentially avoidable ED visits, only a handful of studies had explored the factors associated with avoidable ED visits such as reasons for visit, demographics features, and encounter characteristics. In one national study of ED visits and utilization, non-urgent ED visits were shown to be more prevalent in the older, non-Hispanic white, and Medicare-insured patients 6 . Another review showed that, based on limited evidence, younger age, convenience of the ED compared to alternatives, and referral to the ED by a physician all contributed to driving up non-urgent ED use 2 .

To our knowledge, none of the studies had developed advanced models to classify and predict avoidable ED visits, the insights from which could be used to inform more efficient and cost-effective care management. Thus, the goal of this study is to use several machine learning algorithms to predict avoidable ED visits based on patient and visit characteristics known before the point of triage using a conservative definition of avoidable ED visit 7 .

Study Population

The emergency department visits data used for this study comes from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), which is an annual survey tool to collect the utilization of ambulatory services in hospital emergency and outpatient departments 8 . NHAMCS surveys a sample of non-institutional and general hospitals across the United States 8 . For this study, data from the NHAMCS survey collected between the years 2014 to 2018 were included in our sample.

Variables of Interest

From the NHAMCS dataset, we included the following variables of interest: age, gender, race and ethnicity, arrival time, whether the patient was seen at the ED with the past 72 hours, alcohol abuse, substance abuse, comorbidities, including Alzheimer’s, Asthma, Cancer, Chronic Kidney Disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Heart Failure, Coronary Arterial Disease, Depression, Diabetes, End Stage Renal Disease, HIV, Hyperlipidemia, Hypertension, Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Osteoporosis, and Obesity, the total number of chronic conditions, time of day, day in the week of visit, month of visit, and reasons for visit codes. The NHAMCS dataset also contains patient stated reasons for visit, broken down into broad categories of chief complaints by organ system. Reasons for visit, in the form of organ system categories were used as variables in this study. In addition, patient time of arrival, which is encoded as a 24-hour time was recoded into arrival at daytime (between 7 AM and 5PM), night (5 PM and midnight), and overnight (midnight to 7AM).

Data Preprocessing and Avoidable ED Definition

Variables with more than 30% missing values (n=7 variables) and observations with missing data values (18.55%) were dropped. Training and testing datasets were created via a 7:3 split. Subsets of the dataset were created by stratifying by race, gender, and insurance type.

The avoidable ED visit definition of this study is based on a prior avoidable ED visit study by Hsia et al that uses NHAMCS data from earlier years 7 . An avoidable ED visit is defined as discharged ED visits not requiring any diagnostic tests, procedures or medications. Patients admitted for observation, hospitalized, transferred, died in the ED or were dead on arrival were considered to be non-avoidable ED visits and excluded ( Figure 1 ).

Flowchart for defining avoidable ED visit and removing data with missingness or errors

Modeling Methods & Statistical Analysis

To determine the best performing method for the classification task, multiple machine learning methods were experimented, including logistic regression, random forest, gradient boosted tree (XGboost), and multi-layer perceptron (MLP). Random forest and XGboost models were tuned to improve accuracy. After training 4 models with each machine learning method, we compared the area under curve (AUC) of each model. Modeling was performed using python 3.8.

To understand the performance of our model in various key demographic groups, we tested our full model on the demographic-specific testing sets. In addition, we created demographic-specific models, by retraining on demographic-specific training sets, and tested those models on the corresponding demographic-specific testing sets.

In addition, we examined the importance of variables used in the XGboost model. We obtained the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) values from each model using the shap python package. Individual SHAP plots for the main model is shown in Figure 2 and SHAP plots for demographic subgroups are included as supplementary figures.

Feature Importance Chart of Full XGBoost Model.

There are a total of 77,714 individuals in our sample population. There are more females (55%) than males in the data and the mean age is 37.06. 57% of the population is white, 23% is black, and 16% is Hispanic. Private insurance makes up 18% of the population, with 27% of patients using Medicare and 35% using Medicaid. In comparison to the white and black population, the Hispanic population was significantly younger, had decreased usage of Medicare and increased usage of Medicaid ( Table 1 ).

Baseline characteristics of the sample population

We tested four types of models XGBoost, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, and MLP. Out of these models XGBoost was found to have the best testing AUC ( Table 2 ). The training AUC of our full model is 0.723 and the testing AUC is 0.703. The AUC of the full model tested on demographic-specific groups is shown in Table 3 . The AUC of the full model is comparable between the female-only (AUC = 0.706) and male-only (AUC = 0.700) testing sets, as well as between white (AUC = .6984) and black patients (AUC = .7006) testing sets. There is a decrease in model performance among the Hispanic group (AUC = .6724). Within the insurance subgroups, the performance of the model is highest in the Medicare-only group (AUC = 0.7289) and lower in the private insurance-only group (AUC = 0.685) and Medicaid-only group (AUC = 0.677).

Accuracy metrics for best machine learning model experimented in this study

Race Models

We identified several variables to have strong influence on model prediction of non-avoidable or avoidable ED visits. ( Figure 2 ). Age, increasing number of total chronic diseases, and general as well as digestive symptoms all strongly influenced the model to label a visit as avoidable. Reasons for visit stated as injuries, psychiatric symptoms, and younger age strongly influenced the model to predict an avoidable visit. The time of day and day of week of the visit were not considered to be particularly important by our model. We also noted several differences in the feature importance of models trained on specific demographic subgroups. Genitourinary symptoms were strong predictors of non-avoidable ED visits in women (Supplementary Figure 1 a). The presence of Psychiatric symptoms was seen as important in the Medicaid population, but not in either Medicare or Private insurance (Supplementary Figure 3 ).

Supplementary figure 3a. Private-Insurance only model.

In this study, we developed a classification algorithm using machine learning methods to predict avoidable ED visits prior to the patients arriving at the ED. Our results suggest a moderate ability to predict avoidable ED visits using variables known prior to the point of triage, with a max testing AUC just over 0.70. There was little difference in model performance between genders, and between black and white populations, suggesting that our model is not sensitive to racial differences between the two groups. Model performance was worse in Hispanic, as well as patients on Medicaid, suggesting that our model may be biased against these populations. Compared to the Black and White populations, the Hispanic population was significantly younger, used Medicaid more often, and had less comorbidities. Differences in the Hispanic population within the data in comparison to Black and White groups as well as confounding factors not represented in the data such as language or cultural barriers, which have been noted in machine learning work involving Hispanic groups, may explain reduced model performance in this group 9 .

Some of the variables identified in figure 2 as strong predictors of avoidable/non-avoidable determination are consistent with existing knowledge surrounding avoidable ED visits. It is noted that the emergency department setting is not well equipped to treat mental health disorders and substance abuse 7 , which may explain why psychiatric symptoms were associated with avoidable ED visits. Our finding that pediatric age is associated with increased likelihood of avoidable ED visits is consistent with previous findings 10 , 11 , potentially due to a mismatch in perceived severity of a child’s symptoms between parents and healthcare providers. The presence of Medicare insurance was not considered an impactful metric, although PAYTYPER 1(Private Insurance) was associated with increased avoidability and 5(Self-Pay) and -8(Unknown Payment) were associated with decreased avoidability. The time-of-day variable was not considered to be important in the model, suggesting that there is no difference in avoidable visits between overnight and daytime admissions. The day of week variable was also not considered to be important. It is known that patient access to primary care is an important factor in ED utilization. It has been shown that patients seek ED care during windows when primary care physicians are unavailable, such as overnight arrivals and weekend visits in single site studies 12 , 13 . As our data comes from the national level, the impact of primary care availability that may be visible at a local level may be obscured.

Some features were more important in the race, gender, and insurance specific models compared to the base model. Genitourinary symptoms were important in females but not males, possibly due to an increased abundance of urinary tract infections and other gynecological symptoms that present more commonly in females. Arrival by ambulance was important in females but not males and digestive symptoms were more important in females than males. Women are known to have higher rates of digestive primary complaints compared to men (and lower admissions, but same when adjusted for age and comorbidities) 14 . Pregnant women have been noted to use emergency department services non-urgently 15 .

Our work represents the first attempt to use machine learning in the classification of avoidable emergency visits. We identified several factors associated with avoidable and non-avoidable ED visits that may be useful for clinicians and patients in managing their care options. For example, in a primary care or community clinic setting, our model could be deployed to provide patient guidance on whether to schedule a meeting with their physician or go to the emergency department.

The addition of longitudinal care data from healthcare providers would likely improve the accuracy of our model in this setting. Future work should examine the effect of additional variables known prior to the point of triage to improve predictive performance, such as information regarding prior ED utilization.

Figures & Table

Supplementary figure 1a. Female only model.

Supplementary figure 1b. Male only model.

Supplementary figure 2a. Black only model.

Supplementary figure 2b. Hispanic only model.

Supplementary figure 2c. White only model.

Supplementary figure 3b. Medicare only model.

Supplementary figure 3c. Medicaid only model.

Gender Models

Insurance Models

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Medicaid Expansion and Avoidable Emergency Department Use—Implications for US National and State Government Spending

- 1 School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle

- 2 School of Public Health, Department of Health Systems and Population Health, University of Washington, Seattle

- 3 Evans School of Public Policy & Governance, University of Washington, Seattle

- Original Investigation Association of Medicaid Expansion With Emergency Department Visits by Medical Urgency Theodoros V. Giannouchos, PhD, MS; Benjamin Ukert, PhD; Christina Andrews, PhD JAMA Network Open

Expansion of Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act has been one of the most consequential health and social program reforms in recent decades. Since 2014, approximately 14 million low-income US individuals, most of whom were uninsured before, have gained health insurance coverage through Medicaid expansion alone. 1 Beyond increasing health insurance enrollments, Medicaid expansion has resulted in a net savings for participating states overall (largely owing to enhanced federal cost-sharing) and numerous economic and health benefits for enrollees. 2 However, there are lingering concerns about the ramifications of using a publicly funded coverage mechanism for a large proportion of the population for state and federal budgets.

A crucial question for many policy makers is whether Medicaid expansion offers value over alternative pathways to expand coverage, such as greater investment in subsidized insurance exchanges. However, answering this question largely hinges on the extent to which Medicaid expansion improves the efficiency of health care use and spending. Giannouchos and colleagues 3 examine whether Medicaid expansion was associated with improvements in the use of what is often one of the most expensive health care settings: the emergency department (ED). Their simple yet revealing study further contributes to the literature by noting that Medicaid expansion is a good value for states and is likely to reap long-term benefits in the form of better population health and lower health care spending.

In this study, the authors examined 80.6 million outpatient ED visits from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Emergency Department Databases and a difference-in-differences design to evaluate changes in the rate of outpatient ED use in 2 Medicaid expansion states (New York and Massachusetts) vs 2 nonexpansion states (Georgia and Florida) from 2011 to 2017. 3 Emergency department visits were stratified by severity using the New York University algorithm, which classifies visits based on their likelihood that the primary diagnosis will fall into 1 of 4 subgroups: (1) emergent, not preventable, (2) emergent but potentially preventable, (3) emergent but primary care treatable, and (4) nonemergent. Emergency department visits related to injuries and behavioral health conditions are also classified (or classified separately). Although no clear consensus exists on what proportion of ED visits are unnecessary, it is generally believed that a substantial number could be avoided with either better access to timely and high-quality ambulatory care (such as in the case of preventing exacerbations of chronic illness), greater attention to mitigating social determinants of health or, at least, shifting care to a less costly venue (such as an urgent care center).

The investigators found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant reduction in overall ED use by 4.7 visits per 1000 population. 3 Furthermore, this reduction was associated largely with changes in the subgroups of ED visits that are potentially avoidable, with greater decreases noted for the least severe conditions that are likely to be most avoidable and smaller decreases for higher severity conditions. Visits classified as nonemergent decreased by 1.5 visits per 1000 population, those classified as primary care treatable declined by 1.1 visits per 1000 population, and those classified as emergent, but potentially preventable declined by 0.3 visits per 1000 population (all statistically significant declines). Conversely, the authors noted no associations with visits classified as injuries and emergent, not preventable, which would not be expected to change owing to insurance coverage alone. Although the present study was limited to ED use, the apparent disproportionate reductions in nonemergent and primary care–treatable conditions are highly suggestive of greater access to alternative and less-costly sources of care. Accordingly, these results are largely consistent with the preponderance of studies that show increased access to preventive care, better continuity of care and management of chronic disease, and an overall decrease in unmet health care needs among low-income adults in states that expanded Medicaid vs those that did not. 4 , 5

Reducing unnecessary ED use has been a longstanding priority for state policy makers. Medicaid enrollees use the ED at higher rates than those with private insurance or who are uninsured. 6 Although Medicaid coverage clearly improves access to essential services relative to having no insurance, many Medicaid enrollees still experience persistent barriers in accessing high-quality and coordinated services and face poor social determinants of health, both of which are associated with avoidable ED use. Moreover, unlike private insurance, most Medicaid programs do not impose cost-sharing requirements for health care services used by enrollees, which lowers the opportunity cost for using the ED for Medicaid enrollees compared with individuals with private coverage. This situation may be why many studies on Medicaid coverage expansions demonstrate increased ED use. For example, the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, a randomized clinical trial under which Medicaid coverage was expanded via lottery to a subset of low-income individuals in Oregon, found that ED visits increased by 40% in the first year and a half following enrollment. 7 It is, therefore, understandable that the outcomes of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion on ED use have been an area of intense study.

Although Giannouchos et al 3 found encouraging patterns of ED use, other studies have found the opposite. In particular, a 2019 study by Garthwaite et al, 8 which also used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project data, but included 20 states and all ED visits (both outpatient ED visits as well as those leading to inpatient admission), found that ED use for deferrable conditions increased in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states, whereas those for nondeferrable conditions did not. The authors defined deferrable conditions as those that a panel of physicians believed were likely to be at the patient’s discretion, and nondeferrable conditions as those that were truly emergent and not likely to be discretionary. This latter study only examined data through 1 year postexpansion and, thus, may have observed an early uptick in ED use owing to pent-up demand. The study by Giannouchos et al 3 incorporates a 4-year time horizon but a more limited set of states, which could explain the variable results.

So, where does this study leave us on the question of whether Medicaid expansions improve value for states with respect to ED use? It appears that for some states, expanding Medicaid improves the efficiency ED use, resulting in fewer ED visits for conditions that may be prevented with better access to primary care. In other states, especially those that may have less ambulatory capacity to meet increased demand from newly enrolled Medicaid beneficiaries, ED visits may increase (at least initially). However, it is important to consider that better access to care and management of chronic disease may take years to manifest in the form of improved health and lower rates of avoidable ED visits. As a result, the long-term outcomes of Medicaid expansion associated with avoidable ED use should remain an area of ongoing inquiry as a meaningful indicator of the effectiveness of the ambulatory care system for Medicaid enrollees, as well as the overall health of the Medicaid population.

Published: June 14, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16917

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2022 Sabbatini AK et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Amber K. Sabbatini, MD, MPH, School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Washington, 1705 NE Pacific St, Box 357235, Seattle, WA 98195 ( [email protected] ).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

See More About

Sabbatini AK , Dugan J. Medicaid Expansion and Avoidable Emergency Department Use—Implications for US National and State Government Spending. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2216917. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16917

Manage citations:

© 2024

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Predicting Preventable Emergency Room Visits

A Census Bureau study finds connections between people who make preventable emergency department visits and the social determinants of health.

Predicting Preventable ER Visits

Getty Images

A study of data from Utah found preventable emergency care visits occurred at higher rates among patients who were lower-income, less educated, unemployed, uninsured, lacked internet access or didn’t have access to a car.

Preventable emergency room visits cost the health care system billions of dollars per year . They can represent a heavier burden for providers, as well as unnecessary suffering by patients whose conditions could have been cared for elsewhere or in a better coordinated way .

A recent working paper published by the U.S. Census Bureau found that these visits are more likely to occur among those who are socioeconomically vulnerable – suggesting these are the patients and populations that would benefit most from policies that encourage preventive medicine, access to care and the targeted deployment of medical resources.

For the study, bureau researchers partnered with the Utah Department of Health , combining data from the American Community Survey with data on emergency department visits from 2013 to 2017. An estimated one-third of Utahns ended up visiting the emergency department at some point during that five-year period, but they often didn’t have to: Perhaps their issue could have been treated in primary care, or the problem may not have been an actual emergency.

Preventable emergency care visits occurred at higher rates among patients who were lower-income, less educated, unemployed, uninsured, lacked internet access or didn’t have access to a car. Such patients may not always be able to drive to a primary care doctor, for example, or afford medication for a chronic disease.

On average, people living in poverty also made far more visits for a nonemergency or a condition treatable through primary care than those not in poverty, and females made more preventable emergency room visits than males. Notably, types of ED visits excluded from analysis included those related to substance abuse, mental health and injury, according to the paper.

Data from the U.S. News Healthiest Communities rankings paints a similar picture. The rankings take into account the share of people living in poverty in a county, as well as the rate of hospitalizations per 100,000 Medicare recipients for preventable conditions such as asthma, diabetes, dehydration and pneumonia.

When comparing counties with poverty rates of less than 10% to those with poverty rates of 30% or higher, the median low-poverty county saw 4,121 preventable hospitalizations per 100,000 beneficiaries in 2018, while the median high-poverty county saw 5,833.

Join the Conversation

Tags: hospitals , patient advice , Census Bureau , medical quality , public health , poverty

Recommended Articles

Healthiest communities.

Healthiest Communities Health News

Best States

- # 1 Los Alamos County, NM

- # 2 Falls Church city, VA

- # 3 Douglas County, CO

- # 4 Morgan County, UT

- # 5 Carver County, MN

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

RFK Jr.: By the Numbers

Laura Mannweiler April 26, 2024

Biden’s Student Loan Chief to Step Down

Lauren Camera April 26, 2024

What to Know: Bird Flu Virus in Milk

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder April 26, 2024

Inflation a Stubborn Foe for the Fed

Tim Smart April 26, 2024

The Curse of the Modern Vice President

‘A Rule for the Ages’

Lauren Camera April 25, 2024

Avoidable emergency department visits: a starting point

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California at San Francisco, 1001 Potrero Ave, 1E21, San Francisco, CA 94110, USA.

- 2 Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California at San Francisco, 3333 California St, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA.

- PMID: 28992158

- DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzx081

Objective: To better characterize and understand the nature of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' emergency department (ED) visits in the United States to provide policymakers insight into what interventions can target non-urgent ED visits.

Design/setting: We performed a retrospective analysis of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' ED visits using data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2005 to 2011.

Participants: We examined a total of 115 081 records, representing 424 million ED visits made by patients aged 18-64 years who were seen in the ED and discharged home.

Main outcome measures: We defined 'avoidable' as ED visits that did not require any diagnostic or screening services, procedures or medications, and were discharged home.

Results: In total, 3.3% (95% CI: 3.0-3.7) of all ED visits were 'avoidable.' The top five chief complaints included toothache, back pain, headache, other symptoms/problems related to psychosis and throat soreness. Alcohol abuse, dental disorders and depressive disorders were among the top three ICD-9 discharge diagnoses. Alcohol-related disorders and mood disorders accounted for 6.8% (95% CI: 5.7-8.0) of avoidable visits, and dental disorders accounted for 3.9% (95% CI: 3.0-4.8) of CCS-grouped discharge diagnoses.

Conclusions: A significant number of 'avoidable' ED visits were for mental health and dental conditions, which the ED is not fully equipped to treat. Our findings provide a better understanding of what policy initiatives could potentially reduce these 'avoidable' ED visits to address the gaps in our healthcare system, such as increased access to mental health and dental care.

Keywords: avoidable; emergency care; emergency department; health policy; healthcare system; non-urgent; setting of care.

© The Author 2017. Published by Oxford University Press in association with the International Society for Quality in Health Care. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected]

- Alcoholism / epidemiology

- Emergency Service, Hospital / statistics & numerical data*

- Health Care Surveys

- Middle Aged

- Mood Disorders / epidemiology

- Patient Discharge / statistics & numerical data*

- Retrospective Studies

- Stomatognathic Diseases / epidemiology

- United States

Estimates of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2016-2021

The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), collects annual data on visits to emergency departments to describe patterns of utilization and provision of ambulatory care delivery in the United States. Data are collected from nonfederal, general, and short-stay hospitals from all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, and are used to develop nationally representative estimates.

This visualization depicts both counts and rates of emergency department visits from 2016-2021 for the 10 leading primary diagnoses and reasons for visit, stratified by selected patient and hospital characteristics. Rankings for the 10 leading categories were identified using weighted data from 2021 and were then assessed in prior years; however, rankings were relatively consistent over the evaluated years. See tables in the Definitions section below the visualization for changes in leading primary diagnoses and reasons for visit from 2016-2021. Estimates in this visualization highlight and expand on information provided in the annual NHAMCS web tables , which can be used to assess how these categories and rankings changed over the evaluated years.

Use the tabs at the bottom of the visualization to select between “Primary Diagnosis” and “Reason for Visit”. Use the drop-down menus at the top of the visualization to select the estimate type, the estimate category, and the group breakdown of interest.

Access Dataset on Data.CDC.gov (Export to CSV, JSON, XLS, XML) [?]

Definitions

Based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD–10–CM). See Table 11 of the NHAMCS: 2020 Emergency Department Summary Tables for code ranges of diagnosis categories, available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2020-nhamcs-ed-web-tables-508.pdf .

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2016-2021

Based on the patient’s own words and coded according to: Schneider D, Appleton L, McLemore T. A reason for visit classification for ambulatory care. National Center for Health Statistics. See Appendix II of the 2020 NHAMCS public-use documentation for code ranges of reason categories, available from: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHAMCS/doc20-ed-508.pdf .

Calculated by dividing the number of ED visits by estimates of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population (obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Population Division) for selected characteristics including age, sex, and race and ethnicity. Visit rates for MSA are based on estimates of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population from the National Health Interview Survey, compiled according to the Office of Management and Budget definitions of core-based statistical areas. More information about MSA definitions is available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro.html . Visit rates for patient’s expected source of payment are based on patient’s primary expected source of payment and proportional insurance data from the National Health Interview Survey.

During data collection, all sources of payment were collected. For patients with more than one source of payment, the hierarchy below was used (with Medicare counted first and self-pay and no charge counted last) to collapse payments into one mutually exclusive variable (expected source of payment). Visits that had a missing or unknown expected payment source were excluded (between 10-14% [weighted] from 2016-2021).

- Medicare: Partial or full payment by Medicare plan includes payments made directly to the hospital as well as payments reimbursed to the patient. Charges covered under a Medicare-sponsored prepaid plan are included.

- Medicaid: Partial or full payment by Medicaid plan includes payments made directly to the hospital or reimbursed to the patient. Charges covered under a Medicaid-sponsored prepaid plan (HMO) or “managed Medicaid” are included.

- Private: Partial or full payment by a private insurer (such as BlueCross BlueShield), either directly to the hospital or reimbursed to the patient. Charges covered under a private insurance-sponsored prepaid plan are included.

- Uninsured: Includes self-pay and no charge or charity. Self-pay are charges paid by the patient or patient’s family that will not be reimbursed by a third party. Self-pay includes visits for which the patient is expected to be responsible for most of the bill, even if the patient never actually pays it. This does not include copayments or deductibles. No charge or charity are visits for which no fee is charged (such as charity, special research, or teaching).

- Other: Includes Worker’s Compensation and other sources of payment not covered by the above categories, such as TRICARE, state and local governments, private charitable organizations, and other liability insurance (such as automobile collision policy coverage).

Race and Hispanic ethnicity were collected separately and converted into a single combined variable that includes non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other people. Non-Hispanic other people includes Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Native people, and people with two or more races. Missing values for race and ethnicity were imputed as described in the 2019 NHAMCS public-use documentation, available from: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHAMCS/doc19-ed-508.pdf .

Please send comments or questions to [email protected] .

Data Source

National Center for Health Statistics, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2016-2021

Suggested Citation

National Center for Health Statistics. Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2016-2021. Generated interactively: from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/dhcs/ed-visits/index.htm

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- What Sets It Apart

- Applications

- Global Usage

- License Types

- News & Announcements

- ACG System Knowledge Base

- Resource Library v13.0

- System Documentation

- Bibliography

- User Conferences

- Meet the Team

- Barbara Starfield

- Update / SIgnout

- 2009 Conference Presentations

- 2010 ACG Conference

- 2010 London Symposium

- 2011 Asia Pacific Conference

- 2012 ACG Conference

- 2012 Avignon PCSI

- 2012 London Symposium

- 2013 Perdido Beach

- 2013 WONCA Prague Conference

- 2014 JHU International ACG User

- 2014 London Symposium

- 2015 AcademyHealth Award

- 2015 Hartford Training

- 2016 ACG Conference San Diego

- 2017 London Symposium

- 2017 Puerto Rico Training Conference

- 2017-2018 Webinar Series

- 2018 International Conference San Antonio

- 2018 Leicester Symposium

- 2019 Indian Wells Training

- 2019 London Symposium

- ACG System 10.0.1i Download

- ACG System 9.0i Download

- ACG System Public Documentation

- ACG System x.xi Mapping Files 1

- ACG® System Tutorial Video Library

- Case Studies

- Download The ACG System Software (Non-USA)

- Download The ACG System Software v12.0

- Download The ACG System Software v12.1

- Presentations

- Public Access

- Readmissions White Paper

- System Downloads

- Training Material

- Version 10.0

- Version 10i Training

- Version 11.0

- Version 11.1

- Version 11.2

- Version 12.0

- Version 12.1

- Version 8.2 – 8.2i

- Version 9.0

- White Papers

- Sort Results By Newest Oldest Alphabetical Popularity

Register for access to ACG System website content, newsletter & other communications

POPULATION HEALTH ANALYTICS

A plan of action to reduce avoidable ed visits, june 1st, 2021 | emergency department classification | population health management & improvement.

In our latest blog series, we’ll be taking a look at how the ACG System’s suite of tools can be used to understand emergency department (ED) visits and in turn, optimize health care utilization and reduce potential costs.

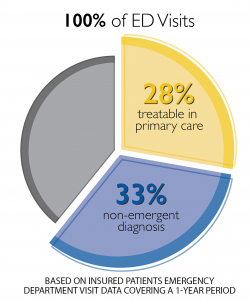

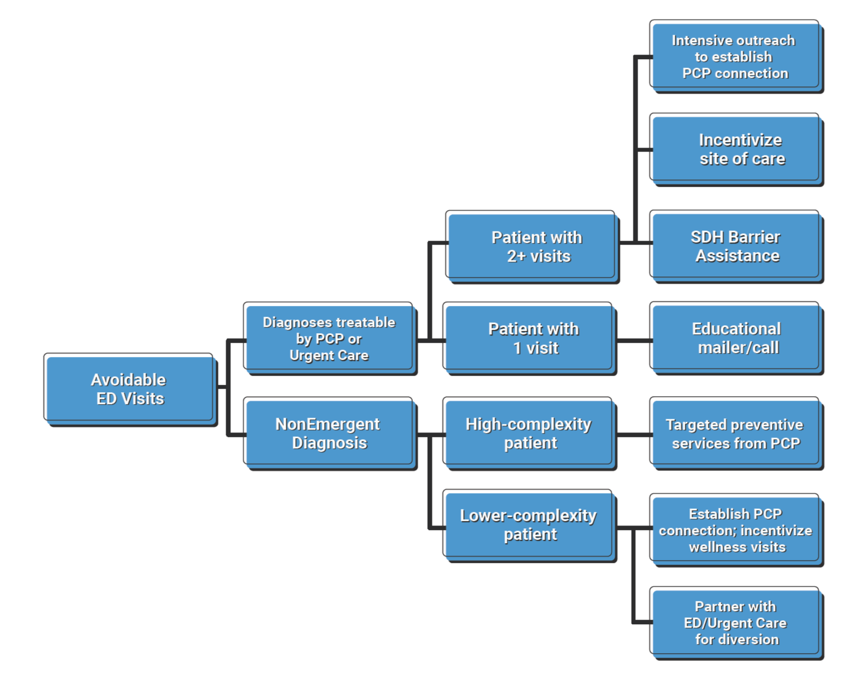

If you read last week’s blog , you know that the ACG System can reveal specific trends in ED visits for a certain population, specifically, patients who visited for non-emergent care or primary care (PCP) treatable conditions. By drilling down into this data, ACG System users can understand root causes of ED use and segment patients into groups depending on their unique health care needs. With this information in hand, System users can develop an effective strategy to reduce ED use and associated health care costs.

Following a detailed, ACG-driven analysis and plan, System users can use granular patient-level outputs to develop and deploy tactics to reduce potentially-avoidable ED visits. Patients with multiple ED visits for PCP-treatable diagnoses may benefit from outreach from their PCP, or assistance locating and working with a PCP if they do not have an existing relationship. The organization may wish to assess systemic access barriers as well, such as transportation challenges, PCP office hours/appointment availability, or prohibitively high co-pay for a PCP visit.

Another impactable patient group are those visiting ED departments for non-emergent diagnoses. ACG System users can identify and target relatively healthy patients (those with lower RUB* levels, for instance) with educational campaigns and incentives for PCP visits. Likewise, individuals with more complex needs, multiple chronic conditions, or care coordination challenges (RUB 4 or 5) can be directed to targeted preventive services and guidance from their PCP. The ability to tailor a specific approach to a specific group of patients maximizes impact while meeting patient-specific care needs.

The diagram below shows how the ACG System can segment a general set of data (avoidable ED visits) into its various, specific components. With each level of segmentation, the data filters into more and more precise groups, who can be targeted for specific interventions.

Ultimately, when ACG System users understand causes and trends in ED use at this granular level, they can proactively target patients with potentially-avoidable visits and deploy interventions to reduce avoidable ED use. The result? Improved access to PCPs and lower unnecessary ED visits.

*RUB = Resource Utilization Band, a category of expected health (care need as defined by the ACG System (1 = low; 5 = high)

Want to take an even deeper dive into how the ACG System can help classify your ED visit data? Read a case study from Israel’s Clalit Health Services here.

Sign up for blog alerts and other insights from the ACG System team

- Hidden Name

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Organization Name *

- Market Segment Other Employer Government / public sector Health Care Provider Health Insurance Plan IT / analytics Pharmaceutical Company Research Institution

- Hidden Compliance

- Hidden Owner ID (Alan)

- Hidden Owner ID (John)

- Hidden Lead Product

- Hidden Lead Source ACG Website

- Send me emails, blog alerts and other insights about population health analytics

- Contact me about how the ACG System can benefit my organization.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

April 11th, 2024

March 14th, 2024, february 15th, 2024, january 18th, 2024, november 30th, 2023.

Copyright 2024, The Johns Hopkins University. All rights reserved.

© The Johns Hopkins University, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Johns Hopkins Health System. All rights reserved. Terms of Use Privacy Statement

- Center on Health Equity and Access

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Value-Based Care

A Revised Classification Algorithm for Assessing Emergency Department Visit Severity of Populations

- Debra M. Ravert, MD

- Jonathan P. Weiner, DrPH

An updated emergency visit classification tool enables managers to make valid inferences about levels of appropriateness of emergency department utilization and healthcare needs within a population.

ABSTRACT Objectives: Analyses of emergency department (ED) use require visit classification algorithms based on administrative data. Our objectives were to present an expanded and revised version of an existing algorithm and to use this tool to characterize patterns of ED use across US hospitals and within a large sample of health plan enrollees.

Study Design: Observational study using National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey ED public use files and hospital billing data for a health plan cohort.

Methods: Our Johns Hopkins University (JHU) team classified many uncategorized diagnosis codes into existing New York University Emergency Department Algorithm (NYU-EDA) categories and added 3 severity levels to the injury category. We termed this new algorithm the NYU/JHU-EDA. We then compared visit distributions across these 2 algorithms and 2 other previous revised versions of the NYU-EDA using our 2 data sources.

Results: Applying the newly developed NYU/JHU-EDA, we classified 99% of visits. Based on our analyses, it is evident that an even greater number of US ED visits than categorized by the NYU-EDA are nonemergent. For the first time, we provide a more complete picture of the level of severity among patients treated for injuries within US hospital EDs, with about 86% of such visits being nonsevere. Also, both the original and updated classification tools suggest that, of the 38% of ED visits that are clinically emergent, the majority either do not require ED resources or could have been avoided with better primary care.

Conclusions: The updated NYU/JHU-EDA taxonomy appears to offer cogent retrospective inferences about population-level ED utilization.

Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(3):119-125. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.42636

Takeaway Points

- There is renewed interest in understanding emergency department (ED) use patterns in populations, both because of increased use associated with healthcare reform and as private payers seek to stem their rising ED spending.

- To assess the appropriateness of ED use at the population level, validated classification methods that use available administrative data will be required.

- Our analysis using an updated classification suggests that an even greater number of ED visits than previously categorized are nonemergent.

- Health plans and other organizations might use ED visit classification algorithms to gain an understanding about how populations make use of hospital services.

The New York University Emergency Department Algorithm (NYU-EDA) is widely used to classify emergency department (ED) visits. 1,2 This measurement tool’s development occurred in the late 1990s and was based on 5700 ED discharge abstracts from 6 hospitals in the Bronx, a borough of New York City. The NYU-EDA probabilistically classified 659 diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM ). The original NYU-EDA mapped only about 5% of all ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. We propose an algorithm that remedies this shortfall and classifies nearly all ED visits.

The NYU-EDA has been applied in health services research studies to identify emergent visits that required ED care. 3,4 Several studies have focused on nonemergent and primary care—treatable ED visits and evaluated emergent and nonemergent utilization patterns to assess the impact of healthcare reforms. 5-11 Estimates of proportions of nonemergent visits have ranged between 17% and 49%. One study looked at primary care—sensitive (PCS) visits (ie, emergent visits that are potentially avoidable and nonemergent and primary care–treatable visits) and found that up to 50% of ED visits were PCS in a statewide all-payer claims database with 92% of ED visits classified. 12

Evidence for the validity of the NYU-EDA has grown over 2 decades. Emergent visits were associated with total charges and increased likelihood of death and inpatient hospitalization directly from the ED and within 30 days from a previous visit. 10,13-15 However, researchers and emergency medicine clinicians have cautioned against using visit classifications based solely on discharge diagnoses for interventions aimed at reducing unnecessary visits or for denying payment. First, underlying differences in morbidity and access to care may, to some degree, account for utilization patterns that would be detected by an ED visit classification algorithm. Second, there are reasons for visits on the individual level that may be appropriate for ED utilization, which can differ from discharge diagnoses that categorize the encounter as nonemergent. For example, patients who are experiencing chest pain and come to the ED for evaluation are not necessarily inappropriately using the ED. ED visit classifications are useful tools for understanding the healthcare needs of populations, not the medical needs of individual patients. 16-19

A team of Johns Hopkins University (JHU) emergency medicine physicians and health services researchers has further updated and expanded the NYU-EDA using their best clinical judgment and diagnosis aggregations from the Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) System. 20 In this revised JHU version of the NYU-EDA (or NYU/JHU-EDA for short) we undertook 3 significant modifications and improvements to the original version and updates undertaken by other teams. First, rather than assigning ICD codes probabilistically, we classify each ED visit into 1 of 11 categories. Second, rather than placing all injuries into 1 category, we subcategorize injuries into 3 severity levels: nonsevere injuries, severe injuries, and severe injuries that are likely to require inpatient admissions. Third, we significantly expand the classification of ICD codes.

In this article, we describe the updated NYU/JHU-EDA, and, using data from a federal survey of US hospital EDs and a large claims database from multiple health plans, we compare results of our revised tool with the original NYU-EDA and 2 earlier modifications developed by Johnston et al and Ballard et al. 2,13

The first objective of this article is to offer a description and first-stage assessment of our ED classification algorithm. The second goal is to use this methodology to offer an account of use patterns of American EDs based on a representative sample of patients visiting hospital EDs and a large national sample of health plan enrollees. In addition to describing our new measurement tool, our analysis adds to the literature on how Americans use EDs and will offer insights into how health plans and other organizations might use classification algorithms to gain an understanding of how populations make use of hospital EDs.

Review of Previous Approaches for Classifying ED Visits

The original NYU-EDA first classifies common primary ED discharge diagnoses as having varying probabilities of falling into each of the 4 following categories: (1) nonemergent; (2) emergent, primary care treatable; (3) emergent, ED care needed, and preventable or avoidable with timely and effective ambulatory care; and (4) emergent, ED care needed, and not preventable. 1 The original NYU system categorizes certain diagnoses separately and directly into 5 additional categories: injuries, psychiatric conditions, alcohol related, drug related, or unclassified.

The adaptation by Ballard et al sums the NYU-EDA probabilities for nonemergent and emergent primary care—treatable visits and compares this sum with the total probability of the emergent, ED care needed categories. 13 Depending on the larger of the 2 resultant likelihoods, visits are classified as nonemergent or emergent, or as intermediate when there is an equal probability of being nonemergent or emergent. The Ballard et al method classifies visits into 1 of 8 categories, which have been shown to be a good predictor of subsequent hospitalization and death within 30 days of an ED visit. 13

After 2001, the NYU-EDA was not updated, and newly added diagnosis codes were not classified. In 2018, Johnston and colleagues identified new codes that are “nested” within previously classified diagnoses and applied the original probabilistic weights to these codes. 2 New diagnoses that remained unclassified were “bridged” to already weighted codes using ICD -based condition groupings from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System. 21 Instances in which a new diagnosis mapped to several codes with different weights were resolved in favor of a code most likely to represent an unavoidable emergent visit. 2 Because assigned weights sum to 1, both the original NYU-EDA and the update by Johnston et al describe a collection of ED visits by averaging weights.

We took a different approach to update, enhance, and expand the NYU-EDA method. We did not use probabilities but rather assigned primary discharge diagnoses to single classes and uniquely classified each ED visit. For codes that had been previously included in the original NYU-EDA, we based our updated assignments on the category with the highest probability. We resolved cases of equally high probabilities among multiple categories by giving preference to the emergent, ED care needed category.

Data Sources

To build our revised methodology, we combined ED encounter data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) from the period of 2009 to 2013. We used data from the 2014 survey for validation. 22 The reason for an ED visit is present in NHAMCS data and contained mainly signs and symptom diagnoses, but it was not present in claims. We used discharge diagnoses only and thus retained a key characteristic of the NYU-EDA and previous revised versions. Second, we extracted hospital ED claims from a large health insurance plan database. We obtained health plan claims data from QuintilesIMS (Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania [on November 6, 2017, the name of the organization changed to IQVIA]). The claims extract spanned the same time period (2009-2013) and included 14 commercial health plans; 6 of these plans also had Medicaid and Medicare managed care enrollees. The database consisted of patient enrollment data, ICD-9-CM diagnoses, hospital revenue center codes, procedures coded with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and plan-allowed amounts for medical services.

Following the literature, we identified ED visits in the claims database through the presence of revenue center codes (0450-0459, 0981) and CPT codes for evaluation and management (EM) services in the ED (99281-99285). 23,24 We resolved instances in which facility and professional claims indicated different primary diagnoses by prioritizing facility bills. Our rationale for giving diagnoses on facility bills priority over professional bills for the same visit is that facility bills relate more closely to the final discharge record, whereas some professional claims may contain preliminary diagnoses.

Development of the NYU/JHU EDA

We applied the Johns Hopkins ACG system to help categorize diagnoses that were not included in the original NYU-EDA method. The system assigns diagnoses found in claims or encounter data to 1 of 32 Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs) (ie, morbidity types with similar expected need for healthcare resources). 25,26 The ACG system also maps diagnoses to 1 of 282 Expanded Diagnosis Clusters (EDCs) (ie, clinically homogeneous groups of diagnoses).

To help expand the scope of the NYU-EDA visit classification to more diagnoses, we formed “clinical classification cells” for ICD codes falling within combinations of ADGs and EDC clusters. Each unique cell was reviewed and categorized by our clinician team of 3 practicing emergency physicians (K.P., D.M.R, and Dr Alan Hsu).

For classification cells with ICD codes that were not previously classified with NYU-assigned probabilities, 2 of our clinicians independently assigned an ED visit class. After differences among approximately 35% of all manual assignments were reconciled and finalized by the third clinician, we developed majority class assignments for the remaining diagnoses within classification cells. Relatively uncommon diagnoses within cells that contained only codes without any original NYU-EDA weights or any manually assigned diagnosis remained unclassified. Using this approach, our NYU/JHU-EDA currently classifies 10,723 ICD-9-CM and 74,329 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-10-CM ) codes ( eAppendix Tables 1 and 2 [ eAppendix available at ajmc.com ] provide examples of common ICD codes in each NYU/JHU-EDA category).

To help us assign severity levels to ACG-based classification cells consisting of injury-related diagnoses, we used CPT codes for EM services associated with ED visits and further assessed whether visits resulted in an inpatient admission. EM codes classify severity from minor (99281) to high with immediate threat to life or physiologic function (99285). We counted the number of nonsevere injury visits (99281-99283) and the number of severe injury visits (99284, 99285) in our health insurance claims data sets. Based on the larger of the 2 counts, each of our injury diagnosis clusters was classified as being either nonsevere or severe. A subset of severe injury visits was identified as likely to require inpatient hospitalization based on a greater than 50% likelihood of cases being admitted. All injury ICD clusters that were so assigned into 1 of 3 severity levels underwent a final clinical review by our clinician team. A graphic overview of the final classification categories of our revised NYU/JHU-EDA grouping taxonomy is presented in the Figure .

Statistical Analysis

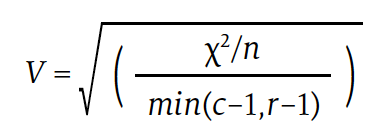

We conducted pairwise comparisons of visit distributions among the 4 EDA versions applied to NHAMCS and health plan data and computed Cramér’s V measure of association. Cramér’s V is a number between 0 and 1 that indicates how strongly 2 categorical variables are associated. It is based on Pearson’s χ 2 statistic and computed as follows:

Download PDF: A Revised Classification Algorithm for Assessing Emergency Department Visit Severity of Populations

Commonwealth Fund Report Details Pervasive Racial and Ethnic Disparities in US Health Care, Outcomes

Using 25 health system performance indicators, the Commonwealth Fund 2024 State Health Disparities Report evaluated racial and ethnic disparities in health care and health outcomes both within and across US states and highlighted the urgent need for equitable health care policies and practices in the US.

Health Equity Conversations: Managing Underserved Communities and Value-Based Payment

On this episode of Managed Care Cast, we feature several leaders in diversity, equity, and inclusion advancing health equity in their respective organization’s policy and practice initiatives.

Institutional Practices for Charitable Medication Access for Uninsured Patients

Analysis of a patient sample enrolled in charitable care at an academic medical center revealed that chronic medications were variably filled at a significant cost.

Health Equity Conversations: Barriers to Equitable Care

Trends in Low-Value Cancer Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Among adults with newly diagnosed cancer, rates of low-value cancer services persisted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in areas ranging from peridiagnosis imaging to end-of-life care.

Impact of Care Coordination on 30-Day Readmission, Mortality, and Costs for Heart Failure

Enhancing coordination of care has the potential to increase the value of heart failure care.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- DATA PRODUCTS

Avoidable Emergency Department Visits

Potentially avoidable emergency department visits.

Efforts to reduce the number of healthcare services that provide little to no value to patients continue to be an industry focal point across the Commonwealth of Virginia. While potentially unnecessary care can take many forms, visits to the emergency department for conditions that likely could have been cared for in a lower cost healthcare setting have previously been identified as a major focus area for Virginia through inclusion in the Health Value Dashboard .

VHI's Potentially Avoidable Emergency Department (ED) Visits Dashboard seeks to highlight how these visits are distributed across the Commonwealth. This interactive dashboard allows users to identify regional and county specific rates of potentially avoidable ED visits, the major types of conditions that drive the frequency of these visits, and how they compare across patient insurance type and over time. While interacting with this dashboard, it's important to consider the following about each of the rates that are displayed:

- ED visits were identified as potentially avoidable based on the primary diagnosis coded on the corresponding paid health insurance claims.

- Important factors such as the time of day a visit occurred, the patient's access to primary care, and other social determinants of health were not taken into account when identifying which ED visits were potentially avoidable.

A full methodology on how this report was prepared can be found here .

Have questions or comments about the dashboard? Click here.

Updated on: 5/2/2023

- HEDIS Measures and Technical Resources

- Emergency Department Utilization

Emergency Department Utilization (EDU)

Assesses emergency department (ED) utilization among commercial (18 and older) and Medicare (18 and older) health plan members. Plans report observed rates of ED use and a predicted rate of ED use based on the health of the member population. The observed and expected rates are used to calculate a calibrated observed-to-expected ratio that assesses whether plans had more, the same or less emergency department visits than expected, while accounting for incremental improvements across all plans over time. The observed-to-expected ratio is multiplied by the emergency department visit rate across all health plans to produce a risk-standardized rate which allows for national comparison.

Why It Matters

ED visits are a high-intensity service and a cost burden on the health care system, as well as on patients. Some ED events may be attributed to preventable or treatable conditions . A high rate of ED utilization may indicate poor care management, inadequate access to care or poor patient choices, resulting in ED visits that could be prevented. 1,2 Plans can ensure that members receive appropriate, coordinated primary care to address preventable ED visits.

Results – National Averages

Emergency department utilization total rate.

*Lower rates signify better performance.

§ Not available due to CMS suspension of data reporting during COVID-19 pandemic.

This State of Healthcare Quality Report classifies health plans differently than NCQA’s Quality Compass. HMO corresponds to All LOBs (excluding PPO and EPO) within Quality Compass. PPO corresponds to PPO and EPO within Quality Compass.

Figures do not account for changes in the underlying measure that could break trending. Contact Information Products via my.ncqa.org for analysis that accounts for trend breaks.

- Dowd, B., M. Karmarker, T. Swenson, et al. 2014. “Emergency department utilization as a measure of physician performance.” American Journal of Medical Quality 29 (2), 135–43. http://ajm.sagepub.com/content/29/2/135.long

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Measures of Care Coordination: Preventable Emergency Department Visits. Accessed at https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/carecoordination/measure2.html

Save your favorite pages and receive notifications whenever they’re updated.

You will be prompted to log in to your NCQA account.

Share this page with a friend or colleague by Email.

We do not share your information with third parties.

Print this page.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

ED visits for conditions that are preventable or treatable with appropriate primary care lower health system efficiency and raise costs ( Enard & Ganelin, 2013 ). An estimated 13% to 27% of ED visits in the United States could be managed in physician offices, clinics, and urgent care centers, saving $4.4 billion annually ( Weinick, et al., 2010 ).

patients may go to the emergency room. For non-emergent issues, the most common reasons relate to access: lack of a relationship with a primary care provider or care team, lack of after-hours or timely access to a provider, or barriers to access such as transportation. For other ED visits deemed avoidable, the reasons may be more

Visits to emergency departments are considered preventable when they are for health conditions that could have been handled in a non-emergency setting or avoided if the patient had adequate prior preventive care. Among factors affecting the rate of preventable emergency room (ER) visits: Income. Education. Employment. Health insurance coverage.

Two-thirds of 27 million emergency department visits by patients with private insurance each year are "avoidable," a new analysis finds. The staggering amount of money the U.S. spends on health ...

In 2010, nearly 1 in 5 visits were determined to be potentially avoidable and contributed $65 billion to rising health care costs and ED overcrowding. 3 The average cost of treating common primary ...

Improper utilization of emergency departments (EDs) in the United States is an issue that places a large burden on the healthcare system. Previous studies have shown that differences in race, gender, and income level have been associated with avoidable ED visits. Broward County, Florida, is diverse with people from many different socioeconomic ...

Reducing avoidable emergency department (ED) visits is an important health system goal. This is a retrospective cohort study of the impact of a primary care intervention including an in-hospital, free, adult clinic for poor uninsured patients on ED visit rates and emergency severity at a nonprofit hospital. We studied adult ED visits during ...

These preventable, or avoidable, ED visits place a strain on ED capacity and have high costs—an estimated $8.3 billion per year, according to a 2019 analysis by Premier. 1 However, ...

Key Points. Question Has there been a change in potentially preventable emergency department (ED) visits among adult patients with cancer over time?. Findings In this cross-sectional study of 35.5 million ED visits among patients with cancer, 51.6% of visits were identified as potentially preventable. From 2012 to 2019, the absolute number of potentially preventable ED visits among patients ...

Introduction. Avoidable emergency department (ED) visits put significant strain on the healthcare system by increasing overall cost and leading to ED overcrowding 1, 2.This problem has received more attention in the US in recent years due to significant increases in annual ED visits and reductions in ED admission rates among the elderly, the Medicare-reimbursed, and patients with multiple ...

The investigators found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant reduction in overall ED use by 4.7 visits per 1000 population. 3 Furthermore, this reduction was associated largely with changes in the subgroups of ED visits that are potentially avoidable, with greater decreases noted for the least severe conditions that are ...

A study of data from Utah found preventable emergency care visits occurred at higher rates among patients who were lower-income, less educated, unemployed, uninsured, lacked internet access or ...

18 Million Avoidable Hospital Emergency Department Visits. According to UnitedHealth Group research, two-thirds of hospital ED visits annually by privately insured individuals in the United States - 18 million out of 27 million - are avoidable. An avoidable hospital ED visit is a trip to the emergency room that is primary care treatable ...

The plan is intended to save millions of dollars, reduce low acuity and possibly preventable emergency room use, and protect patients by implementing these best practices: Tracking emergency room visits to reduce "ER shopping.". Implementing patient education efforts to re‐direct care to the most appropriate setting.

anywhere from 30 -70% of ED visits are potentially avoidable. Research studies on avoidable ED visits for specific settings below: • Nursing Homes: Appropriateness of transferring nursing home residents to emergency departments: a systemic review/ January 2019 • Clinic/Office: CMS TCPi Reducing Unnecessary Emergency Department Visits

Objective: To better characterize and understand the nature of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' emergency department (ED) visits in the United States to provide policymakers insight into what interventions can target non-urgent ED visits. Design/setting: We performed a retrospective analysis of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' ED visits using data from the National ...

This visualization depicts both counts and rates of emergency department visits from 2016-2021 for the 10 leading primary diagnoses and reasons for visit, stratified by selected patient and hospital characteristics. Rankings for the 10 leading categories were identified using weighted data from 2021 and were then assessed in prior years ...

A plan of action to reduce avoidable ED visits. In our latest blog series, we'll be taking a look at how the ACG System's suite of tools can be used to understand emergency department (ED) visits and in turn, optimize health care utilization and reduce potential costs. If you read last week's blog, you know that the ACG System can reveal ...

Reducing avoidable emergency department (ED) visits is an important health system goal. This is a retrospective cohort study of the impact of a primary care intervention including an in-hospital, free, adult clinic for poor uninsured patients on ED visit rates and emergency severity at a nonprofit hospital.

The New York University Emergency Department Algorithm (NYU-EDA) is widely used to classify emergency department (ED) visits. 1,2 This measurement tool's development occurred in the late 1990s ...

ED visits were identified as potentially avoidable based on the primary diagnosis coded on the corresponding paid health insurance claims. Important factors such as the time of day a visit occurred, the patient's access to primary care, and other social determinants of health were not taken into account when identifying which ED visits were ...

Reducing Avoidable Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalization Toolkit. This toolkit provides an overview of a quality improvement process to reduce the frequency of avoidable emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization. As part of a Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement (QAPI) project, this toolkit provides your team with ...

Some ED events may be attributed to preventable or treatable conditions. A high rate of ED utilization may indicate poor care management, inadequate access to care or poor patient choices, resulting in ED visits that could be prevented. 1,2 Plans can ensure that members receive appropriate, coordinated primary care to address preventable ED visits.