National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

The big trip: how to plan the ultimate Silk Road adventure through Central Asia

The old trade routes of the silk road give travellers endless options to explore central Asia, from lake-scattered mountain plateaus to ornate mausoleum complexes and lively cities packed with soviet architecture.

The name ‘Silk Road’ evokes images of Marco Polo and endless camel caravans stretching from Beijing to Baghdad and on to the Venetian Lagoon. But the fact is there was no single, definitive trail. Rather, the Silk Road was an umbrella term for a web of trade routes between China and Europe formed over a period of around 1,600 years, from the second century BC to 1450. While these routes wound as far south as India and Southeast Asia, most of their traffic moved overland through the heart of Central Asia, over snowy passes and through scorching deserts. Routes changed over time as new warlords demanded higher taxes from caravans wanting to travel through their territory. Other times, it was because of dangers caused by brutal brigands capturing riches such as silk, tea, ivory and precious metals, and enslaving travellers. Relics of the era can be found across the region today — particularly in the Central Asian segments of the Silk Road.

Few merchants and travellers made the full journey from Europe to China, as most goods and gold changed hands many times at various points along the Silk Road. Similarly, today, travellers tend to approach the region in bite-sized chunks — travelling the full length would take longer even than Marco Polo’s famous 24-year, 13th-century journey.

History buffs and architecture lovers often focus on Uzbekistan, where preserved mosques and madrasas hide behind fortress walls, and Soviet-era architectural oddities can be found. Trekkers and mountaineers turn towards Kyrgyzstan, a country of snowy peaks and a proud nomadic heritage. Kazakhstan blends the two, with a few attractive Silk Road ruins and impressive landscapes that make it an easy choice to add to any itinerary. The legendary, mountain-backed Pamir Highway — one of the world’s most epic road trips and the northern segment of the ancient Silk Road, described by Marco Polo in the 13th century — lies mostly within Tajikistan’s borders, but travellers intent on seeing it will have to contend with access restrictions and safety concerns.

Itinerary 1: S ilk Road Cities

Once major hubs for global trade and centres of cultural exchange, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s cities are now welcoming oases for history lovers, complete with ornate Islamic architecture and crumbling ruins.

Arriving in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, board a train (13-17h) to Turkistan to explore the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi. Dating to the late 14th century, it’s believed to be the earliest example of the Timurid architectural style — intricate tilework, multiple minarets and domes — that came to define the Silk Road. Set aside half a day to visit the partially excavated ruins of 10th-century desert fortress Sauran, 25 miles north west of Turkistan.

Cross the border to Uzbek capital Tashkent, a pleasant city of parks and fountains that, with nearly three million inhabitants, is the biggest in Central Asia. The 18th-century Kukeldash Madrasah, built as an Islamic school, is one of the largest in Central Asia. Inside the nearby 16th-century Hazrati Imam complex is the world’s oldest surviving Quran , brought to Taskkent by Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur.From Tashkent, travel to Urgench by plane, bus or train (3h/14h/15h) and continue by shared taxi to Khiva (30min), the best preserved fortress city along the Central Asian Silk Road. The 2,400-year-old Itchan Kala (old town) is packed with ancient architecture; it would be easy to spend two days here, wandering the winding streets and climbing lofty minarets for views of the city.

Days 8-12

Go by train to Bukhara (6h) for three nights, then onward by train to Samarkand (1.5h). Both cities are UNESCO listed; Samarkand is the more famous, but Bukhara is the more appealing as it blends ancient and modern so well. Sixteenth-century trading domes are still in use, standing beside all-but-abandoned synagogues, family homes and bakers’ kiosks. In Samarkand, don’t miss the Gur-e-Amir, a mausoleum complex that contains the tomb of tyrant Timur, whose empire stretched from Aleppo to Delhi, and the imposing Registan — a plaza at the heart of the city that contains three ornately mosaiced madrasas. On the edge of the historic centre, the Shah-i-Zinda mausoleum complex, with its colourful, tiled facades, is also worth a visit.

From Samarkand, add a trip to Shakhrisabz, Timur’s birthplace. Once envisioned as the capital of the Timurid Empire and eventual resting place of the conqueror, plans stalled when Timur unexpectedly died during a military campaign in 1405. Today, it’s a small, traditional town; just past a modern statue of Timur, the restored Chubin Madrasah has been converted into a museum dedicated to the tyrant and his empire.

Itinerary 2: Soviet Legacy

The Soviet Union ruled over much of Central Asia for more than half the 20th century, leaving an enduring physical and ideological legacy that can still be observed in the Silk Road nations of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

Start in Almaty, exploring the history of Kazakhstan’s Soviet-era capital through the architecture and art of the era. A guided walk with the company Walking Almaty can be one of the best ways to uncover Modernist mosaics and Imperial-era buildings across the historic centre. In the mountains above the city is the modernist Medeu Highland Skating Rink, which opened in 1951. Soviet skaters broke more than 200 world records here before the USSR collapsed. It remains a popular venue, as well as an active competition venue.

Travel west by car to Bishkek, across the border in Kyrgyzstan, where Soviet architecture surrounds a Lenin statue in the city centre. Just over an hour east of the city lies Issyk-Ata Sanatoria — a throwback to the Soviet-era hospital-spa-summer-camps, where tourists can stay overnight in dilapidated, pastel-blue dormitories. Guests can hike up the valley to a small waterfall (a three-mile round trip), returning for a dip in the sanatoria’s hot springs. Before returning to Bishkek, detour to Ata Beyit Memorial Complex, an hour west of Issyk-Ata. A secret mass grave of Soviet Kyrgyzstan’s intelligentsia was revealed here by a deathbed confession from one of the guards on duty the night of the massacre.

It’s a nine-hour overland journey by bus or shared taxi via Kazakhstan — or a one-hour, 20-minute flight — from Bishkek to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. Rebuilt after a devastating 1966 earthquake, Tashkent today is still a showcase of Soviet modernism. Wander from the stone Monument to Courage Earthquake Memorial to the Islamic Modernist dome of Chorsu Bazaar and the brutalist facade of Hotel Uzbekistan. Then descend beneath the streets to ride the Soviet-era train carriages of the Tashkent Metro, where each of the 43 stations has its own distinct architectural style and artistic elements. Don’t miss a trip to see Physics of the Sun, a giant industrial solar furnace complex built by the Soviets in 1981 on a hilltop outside Parkent, 31 miles east of Tashkent. Brutalist in design and still operational today, it uses thousands of mirrored panels to channel heat from the sun.

Finish your trip in the far west of Uzbekistan, with a long journey from Tashkent to the town of Nukus on the former shores of the Aral Sea — around 15 hours by car. This remote location is home to the Nukus Museum of Art, which displays collector Igor Savitsky’s world-class Soviet avant-garde art haul. Poor water management by the Soviets turned the Aral Sea (once the world’s fourth-largest lake) into a dust bowl, which can now be toured in a 4WD vehicle to see the carcasses of marooned ships. The barren scrublands are a devastating ecological warning as well as starkly beautiful. Independent visitors can arrange a bed for the night at Mayak Yurt Camp, which can also provide a driver for an unforgettable trip into the desert on the edge of the town of Moynaq, near the former shore.

Itinerary 3: Mountains & outdoor adventure

Lace up your hiking boots and head into the Tien Shan. The ‘heavenly mountains’ — a range that defines the border between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan — live up to their name, offering divine views of snow-capped peaks. There’s adventure here for every level of ability.

From mountain-flanked Almaty in Kazakhstan, it’s a three-hour drive to 93-mile-long Charyn Canyon for hikes among red-rock towers and through labyrinthine gorges. The alpine village of Sati makes an ideal base for visiting the Kolsai Lakes. From the nearest lake, it’s an easy five-mile hike to the next, then a challenging two-and-a-half miles to the final one. Two valleys east, you’ll find Lake Kaindy; created by an earthquake in 1911, it contains a partially submerged forest of spruce trees, whose exposed tips make for a surreal sight.

Cross the border into Kyrgyzstan and make for Karakol, founded in 1869 as a military outpost. Its wooden cottages are now interspersed with hostels catering to armies of hikers. The three-day trek to Ala-Kul lake is Kyrgyzstan’s most popular, climbing to an altitude of 3,900 metres for epic views over the lake from the Ala-Kul Pass. At the end of the trek, visitors can hire a Soviet-era military truck for a day trip to the Altyn-Arashan springs to sooth sore muscles.

Days 9-11

Hike around Issyk Kol lake, staying at lakeside yurt camps such as Feel Nomad or Bel-Tam . Support conservation initiatives on a guided hike of Baiboosun Nature Reserve or make the easy, one-mile hike to the Shatyly Panorama for views over Issyk Kol and the snowy Tien Shan peaks.

Continue to Song-Kol lake at a breathtaking 3,015 metres. Drive up in around four hours from Kochkor on Issyk Kol’s western side, or take one to two days hiking and horse-trekking there from Kyzart, 45 miles west of Kochkor. Spend a full day at the lake, horse-riding through the grasslands in solitude. Afterwards, drive to Bishkek for day hikes up the forested slopes of nearby Ala Archa National Park or to explore the Soviet architecture of the capital.

How to travel: a practical guide

What visas will I need for Central Asia?

Visa policies have loosened considerably over the last decade, with travellers on UK passports currently allowed visa-free entry to Kazakhstan (30-day stay), Uzbekistan (30 days) and Kyrgyzstan (60 days). Longer stays will still require a visa, which must be issued at an embassy or through each country’s e-visa platform . You still need a visa to enter Tajikistan, which can be applied for online before arrival (avoid the on-arrival service, which is a frustrating, time-consuming process).

Am I likely to need any travel permits?

Trips to some remote border regions of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan do require special permits. If your itinerary includes the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan, for example, you’ll need a permit from the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, and it’s best to apply for it with your initial country visa application to save time. Applying for permits can involve Soviet-style bureaucracy; if travelling independently, it’s worth paying a local tour company to do it on your behalf. Fees are usually £25 to £40 per permit.

How should I manage money while travelling?

Credit cards are widely accepted in Central Asia’s cities but rarely outside of them, and even in cities you’ll still need cash for small purchases. ATMs are widespread in the big cities, but they can unexpectedly run out of cash — particularly on weekends — so it’s worth also carrying some foreign currency. British pounds and Euros can reliably be changed in cities, but in towns and rural areas US dollars are the easiest to exchange.

What languages are spoken across the Central Asian Silk Road?

Russia is the common language in this region. Tourism businesses in popular destinations will usually have English-speaking staff; it’s harder to find English speakers in rural areas.

How should I dress while travelling here?

Locals across the region typically dress more conservatively than in the West. While visitors aren’t usually expected to adhere to local norms, you may be the target of unwanted attention if you don’t cover your shoulders and knees, especially in rural areas; the capital cities across Central Asia tend to be more liberal.

Related Topics

- CITY GUIDES

- CULTURAL TOURISM

- RELIGIOUS TRAVEL

You May Also Like

10 whimsical ways to experience Scotland

A guide to Jaipur's craft scene, from Rajasthani block printing to marble carving

Free bonus issue.

Visiting North Carolina: Here’s what the locals love

How to plan a weekend in South Moravia, Czech wine country

The essential guide to visiting Scotland

The essential guide to visiting Alaska

6 experiences you shouldn't miss in Connemara

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

- History & Culture

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

The silk road.

For more than 1,500 years, the network of routes known as the Silk Road contributed to the exchange of goods and ideas among diverse cultures.

Social Studies, Ancient Civilizations, World History

Kharanaq, Iran

A tourist looks around the ancient city of Kharanaq, Iran. Towns such as these played a crucial role in the operation and success of the Silk Road.

Photograph by Mekdet

The Silk Road is neither an actual road nor a single route. The term instead refers to a network of routes used by traders for more than 1,500 years, from when the Han dynasty of China opened trade in 130 B.C.E. until 1453 C.E., when the Ottoman Empire closed off trade with the West. German geographer and traveler Ferdinand von Richthofen first used the term “ silk road” in 1877 C.E. to describe the well-traveled pathway of goods between Europe and East Asia. The term also serves as a metaphor for the exchange of goods and ideas between diverse cultures. Although the trade network is commonly referred to as the Silk Road, some historians favor the term Silk Routes because it better reflects the many paths taken by traders.

The Silk Road extended approximately 6,437 kilometers (4,000 miles) across some of the world’s most formidable landscapes, including the Gobi Desert and the Pamir Mountains. With no one government to provide upkeep, the roads were typically in poor condition. Robbers were common. To protect themselves, traders joined together in caravans with camels or other pack animals. Over time, large inns called caravanseraiscropped up to house travelling merchants. Few people traveled the entire route, giving rise to a host of middlemen and trading posts along the way.

An abundance of goods traveled along the Silk Road. Merchants carried silk from China to Europe, where it dressed royalty and wealthy patrons. Other favorite commodities from Asia included jade and other precious stones, porcelain, tea, and spices. In exchange, horses, glassware, textiles , and manufactured goods traveled eastward.

One of the most famous travelers of the Silk Road was Marco Polo (1254 C.E. –1324 C.E.). Born into a family of wealthy merchants in Venice, Italy, Marco traveled with his father to China (then Cathay) when he was just 17 years of age. They traveled for over three years before arriving at Kublai Khan’s palace at Xanadu in 1275 C.E. Marco stayed on at Khan’s court and was sent on missions to parts of Asia never before visited by Europeans. Upon his return, Marco Polo wrote about his adventures, making him—and the routes he traveled—famous.

It is hard to overstate the importance of the Silk Road on history. Religion and ideas spread along the Silk Road just as fluidly as goods. Towns along the route grew into multicultural cities. The exchange of information gave rise to new technologies and innovations that would change the world. The horses introduced to China contributed to the might of the Mongol Empire, while gunpowder from China changed the very nature of war in Europe and beyond. Diseases also traveled along the Silk Road. Some research suggests that the Black Death , which devastated Europe in the late 1340s C.E., likely spread from Asia along the Silk Road. The Age of Exploration gave rise to faster routes between the East and West, but parts of the Silk Road continued to be critical pathways among varied cultures. Today, parts of the Silk Road are listed on UNESCO ’s World Heritage List.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, specialist, content production, last updated.

February 9, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

The Silk Road: 8 FAQs to Understand the Silk Road's Past and Future

The Silk Road trade route was recognized about 2,100 years ago in China for its trade and travel from China's Han Empire to Central Asia and Europe, and it revolutionized the world until it declined during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

Content Preview

What was china's silk road.

- Why Was It Called the Silk Road?

Where Did the Silk Road Start and End?

Why was the silk road important, what was traded on the silk road, how did the silk road come into being, when did the silk road come to an end, is the silk road still used today.

The Silk Road was an ancient trade and communication route across the Eurasian continent, formally recognized in China during the reign of Emperor Wu (157–87 BC) of the Han Dynasty. It linked China with many regions of the Old World in commerce between 119 BC and around 1400 AD.

In fact, the Silk Road can be divided into the "overland Silk Roads" and the " Maritime Silk Road ". Now, we usually refer to the northern overland Silk Road as the Silk Road in China.

Learn more from 13 Silk Road Facts You Didn't Know .

Recommended Silk Road tours:

- 11-Day Along the Great Silk Road

- 5-Day Dunhuang Desert Culture Journey

- More Silk Road tours

Why Is It Called the Silk Road?

China is the "hometown of silk", and silk was the most representative of the goods exported by China on the Silk Road.

At the end of the 19th century, German geographer and traveler Ferdinand von Richthofen called the Silk Road routes die Seidenstrasse ('the Silk Road') or Seidenstrassen ('silk roads') in his book 'China'. The term was quickly accepted by academics and the public, and "Silk Road" was formally accepted as a proper noun.

In 119 BC, the Silk Road started from Chang'an (now called Xi'an), China's ancient capital, which was moved further east (and with it the Silk Road's start) to Luoyang during the Later Han Dynasty (25–220 AD). The Silk Road ended in Rome .

The total length of the Silk Road was about 9,000 kilometers (5,500 miles), and the total length of the northern Silk Road routes in China was about 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles).

Which Countries Did the Silk Road Go through?

Starting from ancient China, the northern Silk Road bifurcated through the five Central Asian countries (the Stans), and continued through Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and Turkey, then to Greece and Italy across the Mediterranean Sea.

The Silk Road was not a single thoroughfare.

The main northern route went from Xi'an/Luoyang through the Gansu Corridor to Dunhuang with two or three trails crossing the desert to Kashgar, then across Central Asia to Europe.

The southwestern Silk Road route (the Tea Horse Road ) went from Yunnan and Sichuan through Tibet to India, and the Maritime Silk Road went via sea/ocean via SE Asia and India to the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

The Silk Road promoted trade and commerce and cultural exchanges between European, African, and Asian countries. It generated the first upsurge of exchanges between China and the West.

Trade and travel between East and West caused revolutionary changes in everything from culture, religion, and technology to the emergence of huge empires and the disappearance of many small tribes, kingdoms, and empires.

The inventions of paper and gunpowder in China were so powerful that when the technology reached Europe, it enabled the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, and the scientific and industrial revolutions that transformed the world.

Paper enabled rapid publication, and gunpowder weapons changed warfare and enabled the destruction of older empires and the emergence of new nations.

Plagues spread and destroyed half the populations of large regions of Eurasia and new crops and technologies allowed the population in Eurasia to grow rapidly.

The Mongol invasions on the Silk Road routes imprinted Mongol ethnicity and language from Xinjiang to Eastern Europe.

Two of China's major religions, Buddhism and Islam , were introduced mainly via the Silk Road.

- For more, see Why China's Silk Road Is So Significant — 10 Reasons that Changed the World

- 7-Day When Silk Road Culture Meets Fabulous Fall Colors

The Han Empire initially wanted big central Asian horses for their cavalry. Initially, they mainly traded silk, but later paper and porcelain were also exported in exchange for precious metals, glassware, woolen articles, and other products all the way from Europe and Egypt.

- See more on What Was Traded on China's Silk Road and Why.

Silk Road trade from China officially began in 119 BC during the Han Empire period (206 BC – 220 AD).

In 139 BC, Emperor Wudi (156–87 BC) sent out Zhang Qian (200–114 BC) to lead an embassy into Dayuezhi (大月氏), i.e. Tokhara, or Termez in Uzbekistan today, hoping to join forces to repel the Huns.

Unfortunately, Zhang Qian was captured on the way and kept as a prisoner for several years by the Huns.

Eventually he took the opportunity to escape and, with the help of the Dayuan Kingdom (大宛国) of today's Fergana Valley, finally arrived in Dayuezhi.

In 126 BC, Zhang Qian returned to Chang'an and told the emperor about the exotic things he had seen along the way.

In 119 BC, Zhang Qian set out again . He traveled along the Silk Road with large quantities of silk, jade, and lacquerware and traded with the countries along the route.

These countries also sent envoys to the Han Dynasty. From then on, driven by the Silk Road, trade and cultural exchanges became more and more frequent.

The Silk Road trade continued over a roughly 1,500-year period. Trade grew and reached a height when the Mongols had control of Eurasia from China's Yuan Empire (1279–1368) to Eastern Europe.

The fall of the Yuan Empire and increased Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) isolationism, the growth of silk production in Europe and elsewhere, and the growth of maritime trade effectively ended Silk Road trading in the 1400s.

- For more, see The History of the Silk Road in China .

Into the historical context of the Silk Road, a new Silk Road is coming into being. In 2013, China launched the Belt and Road (the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road) Initiative (BRI). It focuses on the goal of promoting mutual development and prosperity.

New trans-Asia transportation infrastructure : Substantial progress has already been made. The first freight trains from Europe to China began running in 2011 and have cut transit time from Germany to China from 50 days by sea to 18 days.

In 2018, a major 5,400-kilometer highway to St. Petersburg from the Yellow Sea was opened that allows vehicles to travel the distance in 10 days. This is a new travel option for economical tourism and sightseeing along Silk Road places.

The Silk Road has become a popular route for tourism . In Xinjiang and along the entire Silk Road from Xi'an to Kashgar and Altay in Xinjiang to Greece and Albania, Silk Road tourism is booming. Multi-country trips tracing the Silk Road route are becoming popular among both Chinese and Westerners.

Explore the Silk Road with Us

Silk Road travel is a rich cultural journey into the heart of China . A personal experience is much more interesting and profound than what you read about in an article. See our recommended Silk Road tours for inspiration:

- 8-Day Miraculous Qinghai and Legendary Silk Road Tour

- 6-Day Silk Road Photography Tour

All our tours are customizable. Contact us to create a trip according to your group size, time, budget, interests, and other requirements.

Get Inspired with Some Popular Itineraries

More travel ideas and inspiration, sign up to our newsletter.

Be the first to receive exciting updates, exclusive promotions, and valuable travel tips from our team of experts.

Why China Highlights

Where can we take you today.

- Southeast Asia

- Japan, South Korea

- India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri lanka

- Central Asia

- Middle East

- African Safari

- Travel Agents

- Loyalty & Referral Program

- Privacy Policy

Address: Building 6, Chuangyi Business Park, 70 Qilidian Road, Guilin, Guangxi, 541004, China

About the Silk Roads

The vast trade networks of the Silk Roads carried more than just merchandise and precious commodities. In fact, the constant movement and mixing of populations brought about the widespread transmission of knowledge, ideas, cultures and beliefs, which had a profound impact on the history and civilizations of the Eurasian peoples. Travellers along the Silk Roads were attracted not only by trade but also by the intellectual and cultural exchange taking place in cities along the Silk Roads, many of which developed into hubs of culture and learning. Science, arts and literature, as well as crafts and technologies were thus shared and disseminated into societies along the lengths of these routes, and in this way, languages, religions, and cultures developed and influenced one another.

Silk is a textile of ancient Chinese origin woven from the protein fibre produced by the silkworm as it makes its cocoon. The cultivation of silkworms for the process of making silk, known as sericulture, was, according to Chinese tradition, developed sometime around the year 2,700 BCE. Regarded as an extremely high value product, silk was reserved for the exclusive usage of the Chinese imperial court for the making of cloths, drapes, banners, and other items of prestige. Its production technique was a fiercely guarded secret within China for some 3,000 years, with imperial decrees sentencing to death anyone who revealed to a foreigner the process of its production. Tombs in Hubei province dating from the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE contain the first complete silk garments as well as outstanding examples of silk work, including brocade, gauze and embroidered silk.

At some point during the 1st century BCE, silk was introduced to the Roman Empire, where it was considered an exotic luxury that became extremely popular, with imperial edicts being issued to control prices. Silks popularity continued throughout the Middle Ages, with detailed Byzantine regulations for the manufacture of silk clothes, illustrating its importance as a quintessentially royal fabric and an important source of revenue for the crown. Additionally, the needs of the Byzantine Church for silk garments and hangings were substantial. This luxury item was thus one of the early impetuses for the development of trading routes from Europe to the Far East.

Knowledge about silk production was very valuable and, despite the efforts of the Chinese emperor to keep it a closely guarded secret, it did eventually spread beyond China, first to India and Japan, then to the Persian Empire and finally to the west in the 6th century CE. This was described by the historian Procopius, writing in the 6th century:

"About the same time [circa. 550 CE] there came from India certain monks; and when they had satisfied Emperor Justinian Augustus that the Romans should no longer buy silk from the Persians, they promised the emperor in an interview that they would provide the materials for making silk so that never should the Romans seek business of this kind from their enemy the Persians, or from any other people whatsoever. They said that they were formerly in Serinda, which they call the region frequented by the people of the Indies, and there they learned perfectly the art of making silk. Moreover, to the emperor who plied them with many questions as to whether he might have the secret, the monks replied that certain worms were manufacturers of silk, nature itself forcing them to keep always at work; the worms could certainly not be brought here alive, but they could be grown easily and without difficulty; the eggs of single hatchings are innumerable; as soon as they are laid men cover them with dung and keep them warm for as long as it is necessary so that they produce insects. When they had announced these tidings, led on by liberal promises of the emperor to prove the fact, they returned to India. When they had brought the eggs to Byzantium, the method having been learned, as I have said, they changed them by metamorphosis into worms which feed on the leaves of mulberry. Thus began the art of making silk from that time on in the Roman Empire."

Beyond Silk: a diversity of routes and cargos

These routes developed over time according to shifting geopolitical contexts throughout history. For example, merchants from the Roman Empire would try to avoid crossing the territory of the Parthians, Rome’s enemies, and therefore took routes to the north instead, across the Caucasus region and over the Caspian Sea. Similarly, whilst extensive trade took place over the network of rivers that crossed the Central Asian steppes in the early Middle Ages, their water levels rose and fell, and sometimes rivers dried up altogether, and trade routes shifted accordingly.

The history of maritime routes can be traced back thousands of years, to links between the Arabian Peninsula, Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Civilization. The early Middle Ages saw an expansion of this network, as sailors from the Arabian Peninsula forged new trading routes across the Arabian Sea and into the Indian Ocean. Indeed, maritime trading links were established between Arabia and China from as early as the 8th century CE. Technological advances in the science of navigation, in astronomy, and also in the techniques of ship building, combined to make long-distance sea travel increasingly practical. Lively coastal cities grew up around the most frequently visited ports along these routes, such as Zanzibar, Alexandria, Muscat, and Goa, and these cities became wealthy centres for the exchange of goods, ideas, languages and beliefs, with large markets and continually changing populations of merchants and sailors.

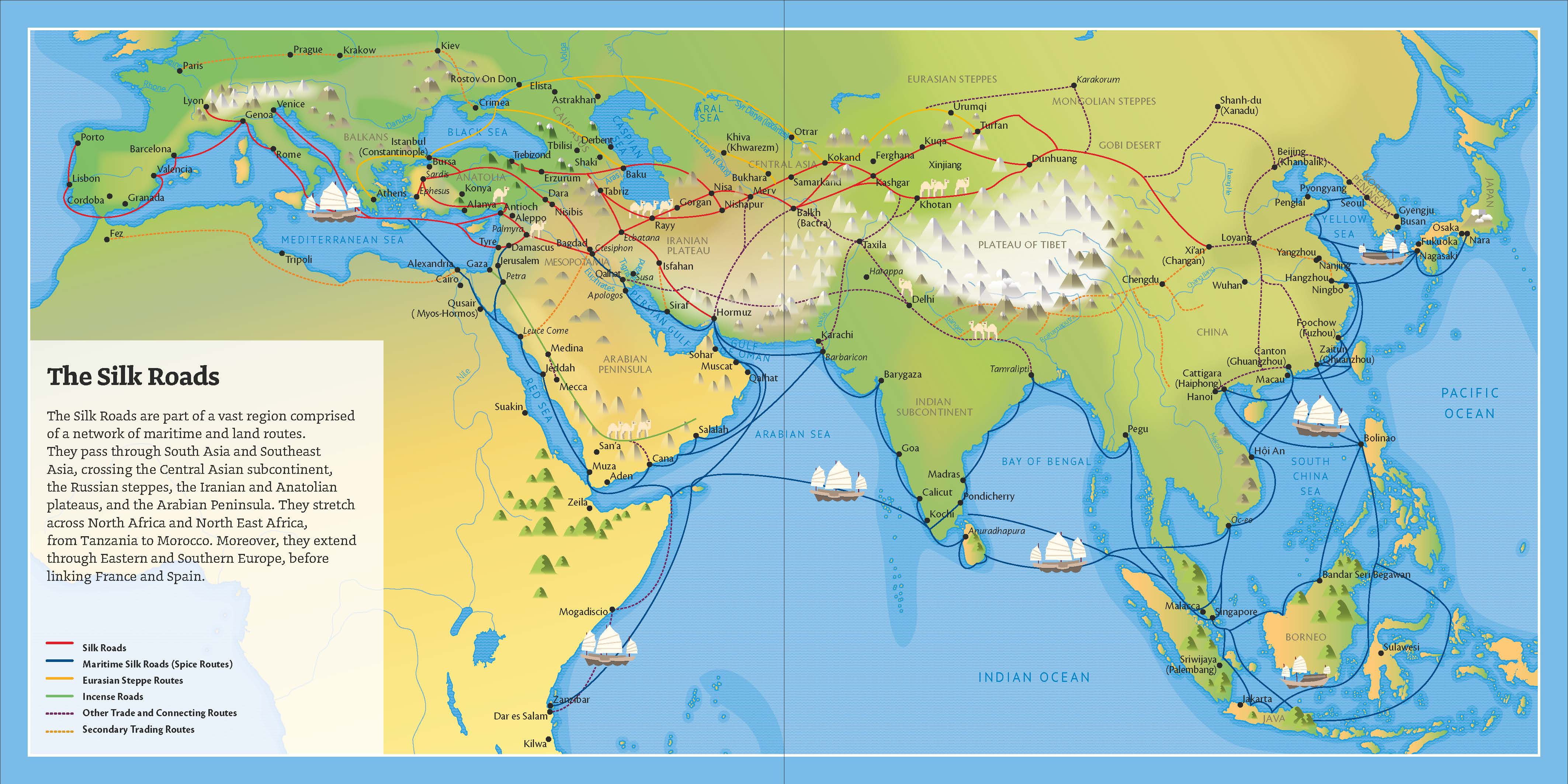

The map above illustrates the great variety of routes that were available to merchants transporting a wide range of goods and travelling from different parts of the world, by both land and sea. Most often, individual merchant caravans would cover specific sections of the routes, pausing to rest and replenish supplies, or stopping altogether and selling on their cargos at points throughout the length of the roads, leading to the growth of lively trading cities and ports. The Silk Roads were dynamic and porous; goods were traded with local populations throughout, and local products were added into merchants’ cargos. This process enriched not only the merchants’ material wealth and the variety of their cargos, but also allowed for exchanges of culture, language and ideas to take place along the Silk Roads.

Routes of Dialogue

Despite the Silk Roads history as routes of trade, the man who is often credited with founding them by opening up the first route from China to the West in the 2nd century BC, General Zhang Qian, was actually sent on a diplomatic mission rather than one motivated by trading Sent to the West in 139 BCE by the Han Emperor Wudi to ensure alliances against Chinas enemies the Xingnu, Zhang Qian was ultimately captured and imprisoned by them. Thirteen years later he escaped and made his way back to China. Pleased with the wealth of detail and accuracy of his reports, the emperor then sent Zhang Qian on another mission in 119 BCE to visit several neighbouring peoples, establishing early routes from China to Central Asia.

These routes were also fundamental in the dissemination of religions throughout Eurasia. Buddhism is one example of a religion that travelled the Silk Roads, with Buddhist art and shrines being found as far apart as Bamiyan in Afghanistan, Mount Wutai in China, and Borobudur in Indonesia. Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism and Manicheism spread in the same way, as travellers absorbed the cultures they encountered and then carried them back to their homelands with them. Thus, for example, Hinduism and subsequently Islam were introduced into Indonesia and Malaysia by Silk Roads merchants travelling the maritime trade routes from the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula.

Travelling the Silk Roads

As trade routes developed and became more lucrative, caravanserais became more of a necessity, and their construction intensified across Central Asia from the 10th century onwards, continuing until as late as the 19th century. This resulted in a network of caravanserais that stretched from China to the Indian subcontinent, Iranian Plateau, the Caucasus, Turkey, and as far as North Africa, Russia and Eastern Europe, many of which still stand today.

Maritime traders had different challenges to face on their lengthy journeys. The development of sailing technology, and in particular of ship-building knowledge, increased the safety of sea travel throughout the Middle Ages. Ports grew up on coasts along these maritime trading routes, providing vital opportunities for merchants not only to trade and disembark, but also to take on fresh water supplies, as one of the greatest threats to sailors in the Middle Ages was a lack of available drinking water. Pirates were another risk faced by all merchant ships along the maritime Silk Roads, as their lucrative cargos made them attractive targets.

The legacy of the Silk Roads

Today, many historic buildings and monuments still stand, marking the passage of the Silk Roads through caravanserais, ports and cities. However, the long-standing and ongoing legacy of this remarkable network is reflected in the many distinct but interconnected cultures, languages, customs and religions that have developed over millennia along these routes. The passage of merchants and travellers of many different nationalities resulted not only in commercial exchange but in a continuous and widespread process of cultural interaction. As such, from their early, exploratory origins, the Silk Roads developed to become a driving force in the formation of diverse societies across Eurasia and far beyond.

Related Links

Unesco integral study of the silk roads, roads of dialogue, recommendations for transnational heritage corridors of silk roads site nomination, this platform has been developed and maintained with the support of:.

UNESCO Headquarters

7 Place de Fontenoy

75007 Paris, France

Social and Human Sciences Sector

Research, Policy and Foresight Section

Silk Roads Programme

Take advantage of the search to browse through the World Heritage Centre information.

Developing a Sustainable Tourism Strategy for the Silk Roads Heritage Corridors

Acclaimed as the ‘greatest route in the history of mankind’, the ancient Silk Road formed the first bridge between the East and the West and was an important vehicle for trade between the ancient empires of China, Central and Western Asia, the Indian sub-continent, and Rome. The Silk Road was more than just trade routes, it symbolised the multiple benefits arising from cultural exchange. As a result, countless historic and cultural sites remain along the network of famous routes.

Today these routes, or ‘heritage corridors’ as they have been identified by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), have the potential to offer economic benefits to local communities and cross cultural exchange through tourism development. The Silk Road’s exceptional cultural and living heritage creates incredible opportunities for tourism.

The Silk Road Heritage Corridors Project

In recent years a team of experts at UNESCO, ICOMOS and UCL, have conducted ground-breaking research into the Silk Road’s sites and routes as part of the transnational Silk Roads World Heritage Serial Nomination project.

15 State Parties

This project has involved unprecedented collaboration between 15 State Parties. Moreover, two World Heritage Nominations for the Silk Roads Heritage Corridor in Central Asia and China have been submitted to UNESCO which will commence the final evaluation of the nominations in 2013-2014. These nominations focus on specific Silk Road Heritage Corridors crossing Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and China, and another between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

At the 3rd UNWTO Silk Road Ministers’ Meeting held on 6 March 2013, the Silk Roads Heritage Corridors Tourism Strategy Project was launched. With a focus on early intervention and upstream processes, UNESCO and UNWTO, supported by the UNESCO/Netherlands Funds-in-Trust, is launching a major project in 2013 that will provide policy guidance to the destinations and will develop a common sustainable tourism strategy for visitor management, site presentation and promotion along these heritage Corridors.

Roadmap for Development

Heritage Conservation & Tourism: Promoting sustainable growth along the Silk Roads Heritage Corridors

This Roadmap lays the foundation for developing a comprehensive and sustainable Silk Roads Heritage Corridors Tourism Strategy. It focuses on two heritage corridors crossing five countries: China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, which form the basis of a serial nomination that will be considered for inscription to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2014. The strategy addresses the overarching principles of sustainable growth, community development, heritage management and conservation.

Read the Roadmap

English Russian

Why this Project is needed

When the World Heritage Convention was conceived in the early 1970s, the impact of tourism was not fully addressed. The annual international arrivals at the time totalled about 180 million, in comparison to the 1 billion international arrivals surpassed in 2012. Cultural tourism is growing at an unprecedented rate and now accounts for around 40% of global tourism.

When managed responsibly, tourism can be a driver for preservation and conservation of cultural and natural heritage and a vehicle for sustainable development. Tourism to World Heritage Sites stimulates employment, promotes local activity through arts and crafts and generates revenues. However, if not planned or managed effectively, tourism can be socially, culturally and economically disruptive, harming hereby fragile environments and local communities.

There are significant opportunities for destinations along the Silk Road corridors to join efforts for building transnational tourism initiatives to promote and develop shared heritage under the Silk Road brand. By taking a collaborative approach to developing tourism for the Silk Road corridors, it is planned that:

- sustainable approaches to destination management will be applied across the region

- dispersal of visitation across the region will improve

- length of stay and yield will increase

- new opportunities for investment will open up

- international relations will be strengthened

- new opportunities for public private sector partnerships will be realised

Useful Links

- UNWTO Silk Road Programme

- UNESCO World Heritage Sustainable Tourism Programme

- ICOMOS International Conservation Center-Xi’an (IICC-X)

- Silk Roads Cultural Heritage Resource Information System (CHRIS)

Project Priorities

A number of priorities have been identified to ensure that the tourism strategy developed for the Silk Road Heritage Corridors optimises the opportunities that tourism presents while safeguarding the outstanding heritage along the Silk Road

- Provide quality visitor experiences that do not degrade or damage the property’s natural or cultural values

- Deliver holistic planning , with well integrated stakeholder participation for long-term sustainability

- Identify nodes (large cities) along the Silk Road, the segments of routes connecting them and the corridors as Silk Road tourism lends itself to attracting travellers along integrated routes and corridors rather than to individual sites or destinations.

- Collaborate on trans-national approaches that are key to strengthening Silk Road tourism.

- Share skills, expertise and knowledge to avoid duplication, build on strengths and implement coordinated management frameworks along the Silk Road with regard to sustainable tourism, conservation, education, research development and interpretation.

- Develop appropriate standards and protocols to face key issues for heritage sites, such as boundaries and buffer zones, site selection, etc.

- Implement monitoring systems at local, national and transnational levels to measure change, impacts of actions and changes to the values of the sites.

- Provide high quality, consistent and informative heritage communication and interpretation , delivered throughout the tourism experience, to build tourist expectations and deliver high quality visitor experiences.

- Invest in Intangible Cultural Heritage such as traditional handicrafts, gastronomy, rituals, music and other cultural expressions to enhance the visitor experience and contribute to intercultural understanding and exchange. This can be achieved through developing community centres for capacity building, organising cultural festivals and implementing marketing and promotional campaigns.

- Embrace technology and innovation such as 3D digital scanning and modelling, digital preservation and archiving. These methods can provide a publicly accessible archive enabling people to visit and learn about cultural heritage sites from around the world. These technologies can also help ensure that heritage sites are effectively managed today as well as protected for tomorrow.

In partnership with

Silk Road Architectural Heritage and Polycentric Tourism Development

- Conference paper

- First Online: 28 April 2022

- Cite this conference paper

- Stella Kostopoulou 23 ,

- Paraskevi-Kali Sofianou 24 &

- Konstantinos Tsiokanos 25

Part of the book series: Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation ((ASTI))

572 Accesses

1 Citations

Polycentricity is a useful multi-scalar spatial concept, operating at local, regional, or national level, that indicates the connection of neighboring centers with common characteristics and their integration in wider spatial networks. Tourism networking is expressed as the cooperation among destinations, their local authorities, tourism stakeholders, local communities etc., toward sustainable tourism development. Cultural heritage, rendering a destination appealing to visitors and tourists to discover the local cultural identity, is considered an important tool for sustainable tourism development. Hence, cultural heritage and tourism are considered important factors of integration in a polycentric spatial system. This paper provides a baseline research on Silk Road architectural heritage tourism, a rather untapped tourism research field, focusing on the interlinkages between polycentricity theory, tourism development and Silk Road built cultural heritage. Silk Road refers to the extensive network of ancient trade routes connecting Eastern and Western civilizations. On these routes, silk and other valuable products such as jewels, metals, glass, porcelain, spices, were transported. Silk Road built cultural heritage with its connotative meanings is an important part of the tangible cultural heritage as historical and cultural evidence. The revival of the Silk Road is expected to enhance new tourism destinations and products, as a major challenge, particularly for induced destinations. The main goal of the paper is to identify and classify Silk Road architectural assets and to introduce regional cooperation opportunities through networking, so as to enhance new tourism destinations. The Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace in Northern Greece, endowed with a plethora of Silk Road built cultural assets, most of them still unexploited, is used as the study area to highlight the proposed methodology. The ultimate goal is the formation of polycentric tourism networks based on Silk Road architectural heritage in order to create a Silk Road regional brand to stimulate tourism development over the study area.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Agnew, N. (1997). Preface. In N. Agnew (Ed.), Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road, International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites . Getty Conservation Institute.

Google Scholar

Andrea, A. J. (2014). The silk road in world history: A review essay. Asian Review of World Histories , 2 (1), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.12773/arwh.2014.2.1.105

Boniface, C. M. P. (2001). Routeing heritage for tourism: Making heritage and cultural tourism networks for socio-economic development. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 7 (3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250126427

Article Google Scholar

Brezzi, M., & Veneri, P. (2014). Assessing polycentric urban systems in the OECD: Country, regional and metropolitan perspectives. European Planning Studies , (August), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.905005

Briant, P. (2002). From cyrus to Alexander. A history of the Persian empire . Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. Retrieved from 978-1-57506-031-6

Bulatova, Y. K., & Ul’chickij, O. A. (2015). Theory and history of architecture, restoration and reconstruction of historical and architectural heritage. Scientific Herald of the Voronezh State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering. Construction and Architecture , 25 (1), 92–104.

Burgalassi, D. (2010). Defining and measuring polycentric regions: The case of Tuscany. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/25880

Burger, M. J., van der Knaap, B., & Wall, R. S. (2013). Polycentricity and the multiplexity of urban networks. European Planning Studies, 22 (4), 816–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.771619

Burger, M. J., & Meijers, E. (2012). Form follows function? Linking morphological and functional polycentricity. Urban Studies, 49 (5), 1127–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011407095

Campos, J. (2003). The cultural consistence of built heritage constitutes its intangible dimension. In 14th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Place, memory, meaning: preserving intangible values in monuments and sites.’ Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe: ICOMOS. http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/474/1/A1-6_-_Campos_%2B_photos.pdf

Chang, T. C. (2010). Bungalows, mansions and shophouses: Encounters in architourism. Geoforum , 41 (6), 963–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.07.003

Clarke, N., Kuipers, M., & Stroux, S. (2020). Embedding built heritage values in architectural design education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 30 (5), 867–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-019-09534-4

CoE. (1975). Architectural heritage . European charter of the architectural heritage . https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/170-european-charter-of-the-architectural-heritage

CoE. (1985). Convention for the protection of the architectural Heritage of Europe. Council of Europe. http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/ita/%0ATreaties/Html/121.htm

Costa, M., & Carneiro, M. J. (2020). The influence of interpretation on learning about architectural heritage and on the perception of cultural significance. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change , 0 (0), 1–20 https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2020.1737705

Dadashpoor, H., & Saeidi Shirvan, S. (2019). Measuring functional polycentricity developments using the flow of goods in Iran: A novel method at a regional scale. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 23 (4), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2018.1556114

Dai, T., Zhuang, T., Yan, J., & Zhang, T. (2018). From landscape to mindscape: Spatial narration of touristic Amsterdam. Sustainability (switzerland), 10 (8), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082623

Davoudi, S. (2003). Polycentricity in European spatial planning: From an analytical tool to a normative agenda. European Planning Studies, 11 (8), 979–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965431032000146169

Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. (2004). The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.). In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acha/hd_acha.htm

E-evros, n.d. Archaeological site of Hanna Traianoupoli (in Greek). https://www.e-evros.gr/gr/pages/4807/arxaiologikos-xwros-xana-traianoypolh

E-evros, n.d. Petrota: the village with the best bridge craftsmen (in Greek). https://www.e-evros.gr/gr/pages/20521/petrwta-to-xwrio-me-toys-kalyteroys-xtistes-gefyriwn-th-sphlia-twn-8rylwn

Eastern Macedonia & Thrace, n.d. Metaxades. https://www.emtgreece.com/en/settlements/metaxades

EL.STAT. (2016). Greece in figures . Peiraeus. http://www.statistics.gr/documents/20181/1515741/GreeceInFigures_2016Q3_GR.pdf/a5def5de-e7f7-423c-a23b-4e3e677a448c

EL.STAT. (2011). Population census . https://www.statistics.gr/en/2011-census-pop-hous

ESPON. (2006). ESPON Project 1.3.3 The Role and Spatial Effects of Cultural Heritage and Identity (2004–2006) . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2000.tb00614.x

ESPON. (2016). Policy Brief: Polycentric Territorial Structures and Territorial Cooperation . ISBN: 978-2-919777-98-3

European Commission. (2020). Region of Anatoliki Makedonia Thraki (Eastern Macedonia and Thrace), Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regional-innovation-monitor/base-profile/region-anatoliki-makedonia-thraki

Finka, M., & Kluvánková, T. (2015). Managing complexity of urban systems: A polycentric approach. Land Use Policy, 42 , 602–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.09.016

Foundation of Thracian Art & Tradition. (2007). Stone bridges. Retrieved December 12, 2020, from http://www.xanthi.ilsp.gr/cultureportalweb/article.php?article_id=995&topic_id=90&level=3&belongs=&area_id=4&lang=en&hightlight=Kokkas

Fung Business Intelligence Centre. (2015). The Belt and Road Initiative: 65 Countries and Beyond.

Gabaix, X., & Ioannides, Y. (2003). The evolution of city size distributions . Medford.

Gavra, E. (1986). Khans and caravanserai from Thessaloniki to Serres and the wider area 1774–1913 (in Greek). Makedonika , 25 , 143–179. https://epublishing.ekt.gr/el/5874/Μακεδονικά/11310

Geiss, P. G. (2021). Central Asia and the Silk Road: Economic rise and decline over several millennia. Central Asian Survey, 40 (1), 134–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2020.1862992

Gholitabar, S., Alipour, H., & da Costa, C. M. M. (2018). An empirical investigation of architectural heritage management implications for tourism: The case of Portugal. Sustainability (Switzerland) , 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010093

Graf, M., & Popesku, J. (2016). Cultural routes as innovative tourism products and possibilities of their development. International Journal of Cultural and Digital Tourism , 3 (1), 24–44. http://iacudit.org/journal/volumes/v3n1/v3n1_24-44.pdf

Green, N. (2007). Functional polycentricity: A formal definition in terms of social network analysis. Urban Studies, 44 (11), 2077–2103. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701518941

Grimmel, A., & Li, Y. (2018). The belt and road initiative: A hybrid model of regionalism. Working Papers on East Asian Studies , 122 . https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/udedao/1222018.html

Gupta, A., & Prakash, A. A. (2018). Conservation of Historic Buildings. International Journal of Engineering Research , 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.5958/2319-6890.2018.00087.9

Hague, C., & Kirk, K. (2003). Polycentricity scoping study . Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. http://www.odpm.gov.uk/stellent/groups/odpm_planning/documents/pdf/odpm_plan_pdf_025470.pdf

Hansen, V. (2002). The impact of the Silk Road trade on a local community: The Turfan Oasis, 500–800. New Perspectives on the Tang Conference, Princeton University . http://pclt.cis.yale.edu/history/faculty/materials/hansen-silk-road-trade.pdf

Hansen, V. (2012). Silk Road: A new story . Oxford University Press.

Haspel, J. (2011). Built heritage as a positive location factor - Economic potentials of listed properties . Paris. https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/1304/1/IV-3-Article3_Haspel.pdf

Munroe,H. N. (2012). Woven Silk. In Medieval Art and The Cloisters . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/material-matters/posts/woven-silk

Hemingway, C., & Hemingway, S. (2007). Ancient Greek colonization and trade and their influence on Greek art. In In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/angk/hd_angk.htm

Hewings, G. J. D., & Parr, J. B. (2007). Spatial interdependence in a metropolitan setting. Spatial Economic Analysis, 2 (1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421770701232467

Hunt, P. (2011). Late Roman Silk: Smuggling and Espionage in the 6th Century CE. https://archive.is/20130626180730 , http://traumwerk.stanford.edu/philolog/2011/08/byzantine_silk_smuggling_and_e.html#selection-461.0-466.0

ICCROM. (2005). Definition of Cultural Heritage. References to documents in history . In J. Jokilehto (Ed.), http://cif.icomos.org/pdf_docs/Documentsonline/Heritagedefinitions.pdf

ICOMOS. (1964). International Charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites (The Venice Charter 1964). IInd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments , 1–4.

ICOMOS. (1993). Cost benefit analysis for the cultural built heritage: The conceptual foundation . https://www.icomos.org/publications/93econom3.pdf

IGEAT (Institut de gestion de l’environnnement et d’aménagement du territoire) et al. (2007). ESPON 1.4.3 Study on Urban Functions. Final Report . Brussels/Luxembourg. https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/fr-1.4.3_April2007-final.pdf

Inalcik, H. (1969). Capital formation in the Ottoman Empire. He Journal of Economic History, 29 (1), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700097849

INSETE. (2019). Who goes where? How much he spends? Analysis of inbound tourism per market and per region . https://insete.gr/studies

INSETE Intelligence. (2020). Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace - Annual report of competition and structural adjunction in the tourism sector (in Greek) . Athens. https://insete.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20-12-Eastern_Macedonia_and_Thrace.pdf

Jeong, S.-I. (2016). The Silk Road Encyclopedia . Seoul Selection U.S.A., Inc.

JTI, n.d. Traveler's Guide, East Macedonia & Thrace. Mosque (Courts) Arap Mosque. http://jti-rhodope.eu/poi.php?poi_id=1_102&lang=en

Juping, Y. (2009). Alexander the great and the emergence of the silk road. The Silk Road, 6 (2), 15–22.

King, L. (1985). The Web Book of Regional Science . In G. I. (1985) Thrall & J. (2020) Randall, (Eds.). Sage. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/rri-web-book

Kloosterman, R., & Musterd, S. (2001). The polycentric urban region: Towards a research agenda. Urban Studies, 38 (4), 623–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120035259

Kostopoulou, S. (2018). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the Silk Road: The European Interdisciplinary Silk Road Tourism Centre. In 8th UNWTO International Meeting on Silk Road Tourism . Thessaloniki, Greece. https://webunwto.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/49581/kostopoulou-_8th_unwto_international_meeting_silk_road_tourism_-_thessaloniki_-_2018_0.pdf

Kostopoulou, S. (2019). Silk Road cultural heritage tourism network. In 5th International Conference of International Association for Silk Road Studies IASS SUN “Silk Road: Connecting Cultures, Languages, and Ideas” (pp. 232–260). Moscow, Russia.

Kostopoulou, S., & Sofianou, E. (2017). Polycentricity and cultural tourism development: Networking festival destinations in Northern Greece. In 54th Colloquium ASRDLF – 15th conference ERSA-GR Cities and regions in a changing Europe: challenges and prospects . Athens.

Kostopoulou, S., Toufengopoulou, A., Kyriakou, D., Malisiova, S., Sofianou, E., & Xanthopoulou-Tsitsoni, V. (2016). The Western Silk Road in Greece . Thessaloniki.

Kostopoulou, S., Sofianou, P. -K., Tsiokanos, K. (2021). Silk road heritage branding and polycentric tourism development. Sustainability , 13 , 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041893

Krochmal, A. (1954). The Vanishing White Mulberry of Northern Greece. Economic Botany , 8 (2), 145–151. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4287804

Kuzmina, E. E. (2007). The prehistory of the Silk Road . In V. Mair (Ed.), University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lambregts, B. (2009). The polycentric metropolis unpacked: Concepts, trends and policy in the Randstad Holland. Amsterdam institute for Metropolitan and International Development Studies (AMIDSt).

Lambregts, B., & Kloosterman, R. (2006). Randstad Holland: Multiple faces of a polycentric role model. The Polycentric . http://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:uva.nl:295109

Lerario, A., & Di Turi, S. (2018). Sustainable urban tourism: Reflections on the need for building-related indicators. Sustainability (Switzerland) , 10 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061981

Liu, B., Huang, S., & Fu, H. (2017). An application of network analysis on tourist attractions: The case of Xinjiang, China. Tourism Management , 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.009

Mark, J. (2018). Silk Road Definition. Retrieved January 2, 2021, from https://www.worldhistory.org/Silk_Road/

Marris, T. (1985). The importance of our architectural heritage for England’s tourism. The Tourist Review, 40 (1), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb057918

Marshall, J. (1989). Rank-size relationships and population concentration. In The Structure of Urban Systems (pp. 326–360). University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/j.ctvcj2zd8.14

Meijers, E. (2005). Polycentric urban regions and the quest for synergy: Is a network of cities more than the sum of the parts? Urban Studies, 42 (4), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500060384

Meijers, E., & Burger, M. J. (2017). Stretching the concept of ‘borrowed size.’ Urban Studies, 54 (1), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015597642

Meijers, E., & Burger, M. J. (2010). Spatial structure and productivity in US metropolitan areas. Environment and Planning A, 42 (6), 1383–1402. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42151

Meijers, E., Hoogerbrugge, M., & Cardoso, R. (2018). Beyond polycentricity: Does stronger integration between cities in polycentric urban regions improve performance? Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 109 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12292

Meijers, E., Hollander, K., & Hoogerbrugge, M. (2012). A strategic knowledge and research agenda on polycentric metropolitan areas . The Hague. www.emi-network.eu

Meijers, E., Waterhout, B., & Zonneveld, W. (2007). Closing the gap: Territorial cohesion through polycentric development. European Journal of Spatial Development, 24 , 1–24.

Melkidi, C. (2006a). Architecture - Metaxades. http://www.xanthi.ilsp.gr/cultureportalweb/article.php?article_id=512&topic_id=56&level=2&belongs=9&area_id=20&lang=en

Melkidi, C. (2006b). Tobacco warehouses. http://www.xanthi.ilsp.gr/cultureportalweb/print.php?article_id=506&lang=en&print_mode=article

Ministry for Arts, Heritage, G. and the I. (1999). Architectural Heritage (National Inventory) and Historic Monuments (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1999. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/bills/bill/1998/76/

Mizzau, L., & Montanari, F. (2008). Cultural districts and the challenge of authenticity: The case of Piedmont, Italy. Journal of Economic Geography, 8 (5), 651–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn027

Mpalta, E. (n.d.). Thrace in the ottoman registrations - 15th-16th centrury (in Greek). In Thrace. History and Geographic approaches . Athens: National Hellenic Research Foundation.

Murata, K. (2019). Procopius in the far East: Japanese language studies and translations. Histos Supplement , 16 , 1–13. https://histos.org/documents/SV09.16.MurataProcopiusinJapanese.pdf

Murzyn-Kupisz, M. (2012). Cultural, economic and social sustainability of heritage tourism: Issues and challenges. Economic and Environmental Studies , 12 (2), 113–133. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/93213www.econstor.euwww.ees.uni.opole.pl

Nordregio. (2005). ESPON 1.1.1 Potentials for polycentric development in Europe . ESPON. https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/fr-1.1.1_revised-full_0.pdf

Ockman, J., & Frausto, S. (Eds.). (2005). Architourism: Authentic, escapist, exotic, spectacular . The Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture, with Prestel, 2005.

Parr, J. (2004). The polycentric urban region: A closer inspection. Regional Studies, 38 (3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/003434042000211114

Parr, J. (2005). Perspectives on the city-region. Regional Studies, 39 (5), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400500151798

Portal, M.-L. (2011). Silk production in Soufli. Archaeology and Arts , 89 , 53–58. https://www.archaiologia.gr/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/89-4.pdf

Rauhut, D. (2017). Polycentricity—One concept or many? European Planning Studies, 4313 (January), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1276157

Richards, G. (2007). Cultural tourism: Global and local perspectives . Psychology Press.

Richards, G., & Munsters, W. (2010). Cultural tourism research methods. Cultural Tourism Research Methods , (October), 1–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.07.014

Richter, G. M. A. (1929). Silk in Greece. American Journal of Archaeology, 33 , 27–33.

Schmitt, P., Volgmann, K., Münter, A., & Reardon, M. (2015). Unpacking polycentricity at the city-regional scale: Insights from Dusseldorf and Stockholm. European Journal of Spatial Development, 59 , 1–26.

Soufli Municipality. (2015). The History of Silk (in Greek). https://soufli.gr/index.php/el/2015-03-01-20-56-3/2015-03-01-21-10-10

Specht, J. (2013). Architecture and the destination image: Something familiar, something new, something virtual, something true BT - Branded Spaces: Experience enactments and entanglements. In S. Sonnenburg & L. Baker (Eds.), (pp. 43–61). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-01561-9_3

Specht, J. (2014). Architectural tourism. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling . Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06024-4

UNESCO. (2004). The World Heritage List: Filling the Gaps - an Action Plan for the Future. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from http://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/5297

UNESCO. (1989). Draft Medium-term plan, 1990–1995 (UNESCO. General Conference, 25th session, 1989). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000082539

UNESCO, n.d. About the Silk Roads. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/about-silk-roads

UNESCO, n.d. Main Street of Eurasia. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/main-street-eurasia

United Nations. (2009). Investment Guide to the Silk Road . New York, Geneva.

UNWTO. (n.d.). Technical cooperation and Silk Road Declarations. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from https://www.unwto.org/es/declarations-silk-road

UNWTO. (2019). The UNWTO Western Silk Road Initiative Maximising the Potential. Retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/2019-09/new_final_wsr_fact_sheet.pdf

Ursache, M. (2015). Tourism—Significant driver shaping a destinations heritage. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188 , 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.348

van Meeteren, M. (2016). From polycentricity to a renovated urban systems theory: Explaining Belgian Settlement Geographies . Ghent University. https://www.academia.edu/33366697/From_Polycentricity_to_a_Renovated_Urban_Systems_Theory_Explaining_Belgian_Settlement_Geographies

Vasanen, A. (2012). Functional polycentricity: Examining metropolitan spatial structure through the connectivity of urban sub-centres. Urban Studies, 49 (December), 3627–3644. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012447000

Vasiliev, I. A., & Shmigelskaia, N. A. (2016). The Revival of the Silk Road: brief review of the 4th China-Eurasia Legal Forum. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Law , 2 (2), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu14.2016.209

Veneris, P., & Kornaraki, C. (2016). Sericulture and the cocoon houses in Soufli, Evros: Examples of rehabilitation (in greek) . http://library.tee.gr/digital/m2401_2500/m2468/m2468_veneris.pdf

Vicente, R., Lagomarsino, S., Ferreira, T.-M., Cattari, S., & Mendes da Silva, J. A. R. (2018). Strengthening and Retrofitting of Existing Structures. In Building pathology and rehabilitation (Vol. 9). Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5858-5

Vogel, D. R., Davison, R., Harris, R., & Sorrentino, M. (2003). eTransformation of the Silk Road : Rejuvenating a Historical Trade Network. In 16th Bled eCommerce Conference eTransformation . Slovenia.

Wahlquist, H. (2020). Albert Herrmann: A missing link in establishing the Silk Road as a concept for Trans-Eurasian networks of trade. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38 (5), 803–808. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420911410a

Wang, R., Liu, G., Zhou, J., & Wang, J. (2019). Identifying the critical stakeholders for the sustainable development of architectural heritage of tourism: From the perspective of China. Sustainability (Switzerland) , 11 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061671

Waugh, D. (2007). Rochthofen’s “Silk Roads”: Toward the Archaeology of a Concept. The Silk Road , 5 . http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/vol5num1/srjournal_v5n1.pdf

Waugh, D. (2010). The Silk Roads in History. Expedition Magazine, Penn Museum , 52 (3), 9–22. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/?p=1294

Williams, T. (2014). The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study . Charenton-le-Pont.

Williams, T. (2016). Mapping the Silk Roads. In W. Mariko Namba (Ed.), The Silk Road: Interwoven history . Cambridge Institutes Press.

Winter, T. (2020). The geocultural heritage of the Silk Roads. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 00 (00), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1852296

Wood, F. (1996). Did Marco Polo go to China? Westview Press, Perseus Book Group.

World Bank Group. (2018). Cultural heritage, sustainable tourism and urban regeneration: Capturing lessons lessons and experience from Japan with a a focus on Kyoto . Washington, D.C. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30204

Xinru, L. (2010). The Silk Road in world history . Oxford University Press.

Zarkada, C. (1984). Xanthi’s khans (in Greek). Archaiologia , 13 , 80–86. https://www.archaiologia.gr/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/13-12.pdf

Zeng, B. (2018). Pattern of Chinese tourist flows in Japan: A social network analysis perspective. Tourism Geographies, 20 (5), 810–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1496470

Zufferey, N. (2008). Traces of the Silk Road in Han-Dynasty iconography: questions and hypotheses. In P. Foret & A. Kaplony (Eds.), The Journey of Maps and Images on the Silk Road . Brill.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund-ESF) through the Operational Programme «Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning 2014–2020» in the context of the project “Polycentric system of cultural tourism destinations of the Silk Road. Case study: Region of Eastern Macedonia-Thrace” (MIS 5047888).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Stella Kostopoulou

Department of Civil Engineering, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Paraskevi-Kali Sofianou

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Konstantinos Tsiokanos

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stella Kostopoulou .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, University of Enna “KORE”, Enna, Italy

Antonella Versaci

Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Aversa, Italy

Claudia Cennamo

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, School of Languages and Cultures, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Natsuko Akagawa

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Kostopoulou, S., Sofianou, PK., Tsiokanos, K. (2022). Silk Road Architectural Heritage and Polycentric Tourism Development. In: Versaci, A., Cennamo, C., Akagawa, N. (eds) Conservation of Architectural Heritage (CAH). Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95564-9_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95564-9_3

Published : 28 April 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-95563-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-95564-9

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

We’re sorry, this site is currently experiencing technical difficulties. Please try again in a few moments. Exception: request blocked

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My Portfolio

- Stock Market

- Biden Economy

- EV Deep Dive

- Stocks: Most Actives

- Stocks: Gainers

- Stocks: Losers

- Trending Tickers

- World Indices

- US Treasury Bonds

- Top Mutual Funds

- Highest Open Interest

- Highest Implied Volatility

- Stock Comparison

- Advanced Charts

- Currency Converter

- Investment Ideas

- Research Reports

- Basic Materials

- Communication Services

- Consumer Cyclical

- Consumer Defensive

- Financial Services

- Industrials

- Real Estate

- Mutual Funds

- Credit Cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash-back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Personal Loans

- Student Loans

- Car Insurance

- Morning Brief

- Market Domination

- Market Domination Overtime

- Opening Bid

- Stocks in Translation

- Lead This Way

- Good Buy or Goodbye?

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Yahoo Finance

Xinhua silk road: cultural tourism festival kicks off in e. china's changshu.

BEIJING , April 1, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- The 2024 Changshu Yushan Culture and Shajiabang Tourism Festival and the 33rd Jiangsu Changshu Shanghu Peony Festival opened in Changshu City of east China's Jiangsu Province on Saturday, aiming to promote development of local cultural tourism.

Themed "Tasting Changshu Culture, Admiring Changshu Scenery", the month-long festival highlights 10 main activities and 10 supporting activities, such as peony festivals, national opera fan competition, Guqin performers gathering and village cultural market.

In recent years, Changshu has integrated culture and tourism and launched a series of characteristic products such as regimen tour, team-building tour and study tour, thus forming a unique tourism product system, said Shen Xiaodong , Chairman of the Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) Changshu Municipal Committee, at the opening ceremony of the festival.

He added that Changshu was at the second place on the Top 100 county list nationwide in terms of county-level comprehensive tourism strength. Its Yushan Cultural Tourism Resort was honored as a national-level tourist resort and dubbed "National Leisure Tourism Destination." Changshu is favored by tourists from home and abroad thanks to its rich tourism resources and well-developed facilities.

It is also learned that the Shanghu Peony Festival is a sub-venue of the 2024 World Peony Conference. Changshu peony is expected to be known worldwide through the interaction between Shanghu Peony Festival, Heze main venue in east China's Shandong Province and Shimane sub-venue in Japan .

This year's peony festival, held both online and offline, has rolled out brand new activities, such as nine-color peony petal rain, flower and bird painting exhibition, the peony fairy parade and special performances, with an aim to build the Shanghu peony brand and make Changshu peony more famous.

Organized by government authorities of Changshu, the festival focuses on various aspects including tourism festival, sports and leisure, folk culture, intangible cultural heritage exhibitions, and food experience.

Original link: https://en.imsilkroad.com/p/339460.html

SOURCE Xinhua Silk Road

Tourism Web Portal

About the portal.

A technological tool for effective communication between the leading players in the Moscow tourism market and representatives of the foreign/regional tourism industry through online events. OBJECTIVES: • Building long-term cooperation with foreign/regional representatives • Raising awareness among foreign/regional representatives of the tourism industry of the tourism opportunities, measures and attractiveness of the city of Moscow in the field of tourist infrastructure development

Moscow City Tourism Committee

The Tourism Committee, or Mostourism, is the executive body of the Moscow City Government that oversees tourist activities in the capital. The Committee is responsible for legislative initiatives, congress and exhibition activities, and event and image projects. As the brand manager for an attractive tourism image for Moscow, Mostourism constantly analyses global trends, offers Russian and foreign tourists what they want, and also uncovers new opportunities for the capital in terms of interesting and rewarding leisure activities.

ANO «Project Office for the Development of Tourism and Hospitality of Moscow»

Syundyukova Yulia [email protected] Mezhiev Magomed [email protected]

Video materials about Moscow

- China Daily PDF

- China Daily E-paper

- Asia-Pacific

- Middle East

- China-Europe

- China-Japan

- China-Africa

Show helps foster mutual understanding