Journey to the West | Full Story, Summary & Moral Lessons

- February 19, 2024

“Journey to the West” stands as one of the pinnacles of Chinese literature, a riveting blend of mythology, folklore, humor, and spirituality .

Authored by Wu Cheng’en in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty, this epic novel has transcended its cultural origins to become a global literary treasure!

The narrative follows the perilous journey of the Buddhist monk Xuanzang, historically known, as he travels to India to obtain sacred Buddhist scriptures. Accompanied by his three disciples— Sun Wukong , Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing—each with their own unique abilities, their quest is filled with divine interventions, battles with demons, and moral lessons.

Many of which we will be getting to know today!

Table of Contents

Historical Context

The “Journey to the West” is deeply entwined with the real-life travels of Xuanzang (602-664 CE), whose pilgrimage to India and back took 17 years, a journey undertaken to obtain authentic Buddhist scriptures.

Wu Cheng’en’s fictionalized account, however, does more than narrate a religious quest; it weaves a rich story of Chinese myths, Taoist and Buddhist philosophy, and satirical commentary on the social issues of his time, making it a multifaceted work of art.

If you’re interested in watching the Journey to the West, I highly recommend the 1986 series as it’s often lauded as being not only the most accurate but also you can really feel the love and respect given to the adaptation.

Key Characters

Tang Sanzang

Tang Sanzang, also known as Tripitaka , stands at the heart of “Journey to the West” as its protagonist. His mission to retrieve sacred Mahayana Buddhist scriptures from India serves as the narrative’s driving force. Tang Sanzang embodies virtues such as humility, compassion, and unwavering dedication to his spiritual quest.

His portrayal as the epitome of piety and moral integrity offers a rich canvas against which his interactions with disciples and various challenges unfold.

Tang Sanzang’s personality is a blend of devout faith and moral steadfastness. He is the moral compass for his disciples, guiding them not only towards their external goal but also on their internal journeys of growth and enlightenment .

Despite his virtues, Tang Sanzang is not portrayed as infallible. His naivety and strict adherence to religious doctrines sometimes lead him into trouble, requiring rescue by his more worldly and powerful disciples. This aspect of his character highlights the novel’s exploration of the balance between innocence and wisdom, as well as the necessity of worldly knowledge in achieving spiritual goals.

Throughout the novel, Tang Sanzang undergoes significant development. His journey is not only a physical one across dangerous terrains but also a spiritual odyssey that tests and refines his character. He learns to balance his strict moral codes with the practicalities of the world, growing in understanding and compassion towards his disciples and the beings they encounter.

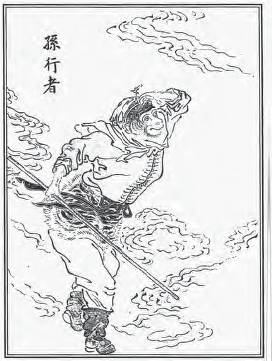

Sun Wukong , famously known as the Monkey King , is one of the most beloved characters in “Journey to the West.”

His origins are as magical as his personality; born from a stone egg on the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit, Sun Wukong acquires supernatural powers through Taoist practices.

His abilities include shape-shifting, immense strength, and the ability to travel vast distances in a single somersault. Despite his powers, Sun Wukong’s early journey is marked by rebellion and pride, leading him to challenge the heavens themselves.

His initial defiance against the celestial order and subsequent punishment—being imprisoned under a mountain by the Buddha—sets the stage for his redemption arc.

His release by Tang Sanzang and commitment to protect the monk on the journey to India is a turning point, marking his transition from a rebellious figure to a devoted disciple. This journey serves as a path of self-discovery and spiritual maturation for Sun Wukong, as he confronts challenges that test his ingenuity, patience, and fidelity.

The Monkey King’s personality is multifaceted; he is cunning and playful, yet capable of profound wisdom and bravery. His loyalty to Tang Sanzang is unwavering, and he becomes the monk’s most powerful protector, using his abilities to overcome demons and obstacles that the pilgrimage encounters. Sun Wukong’s transformation from a mischievous troublemaker to a protector embodies the novel’s themes of redemption and the possibility of spiritual growth regardless of one’s past.

In terms of symbolic significance, Sun Wukong represents the untamed mind and the potential for enlightenment within all beings. His journey from arrogance to enlightenment mirrors the Buddhist path, emphasizing the importance of humility, learning, and devotion.

Through Sun Wukong, “Journey to the West” explores the idea that even the most unruly spirits can achieve enlightenment through perseverance, guidance, and self-reflection.

Zhu Bajie, often referred to as Pigsy , is known for his complex and somewhat contradictory character traits. Originally a marshal in the celestial army, Zhu Bajie was banished to the mortal realm as a punishment for his indiscretions in heaven, particularly with the Moon Goddess, Chang’e .

Transformed into a pig-human hybrid, his appearance reflects his base nature and penchant for indulgence, especially in food and women. Despite these flaws, Zhu Bajie becomes one of Tang Sanzang’s disciples, joining the quest to retrieve the Buddhist scriptures from India.

Zhu Bajie’s personality is marked by a mix of bravery and cowardice, loyalty and self-interest, wisdom and folly. He often provides comic relief in the story through his antics and bumbling mistakes, yet his character also displays moments of insight and bravery.

His earthly desires and tendencies towards laziness often put him at odds with his more disciplined and spiritually focused companions, particularly Sun Wukong, with whom he shares a rivalry.

While he deeply respects Tang Sanzang and is committed to the pilgrimage, his weaknesses often lead to complications and challenges for the group. However, these shortcomings make his moments of courage and sacrifice all the more significant, highlighting the theme of redemption and the possibility of moral and spiritual growth regardless of one’s past actions or nature.

Zhu Bajie’s character serves as a reflection on human nature, embodying the struggles between base desires and higher aspirations, between selfishness and altruism. His journey alongside Tang Sanzang is as much about his own redemption and transformation as it is about the physical pilgrimage to India.

Sha Wujing, or Sandy , is the third disciple who joins Tang Sanzang. Once a celestial general, Sha Wujing was banished to the mortal world as punishment for a transgression in heaven, where he was transformed into a river ogre.

His frightening appearance belies a kind heart and a steadfast, loyal nature. Recognizing his past mistakes, Sha Wujing seeks redemption through service to Tang Sanzang on the perilous journey to the West.

Characteristically, Sha Wujing is the embodiment of stoicism and reliability. Compared to the more flamboyant Sun Wukong and the often comically flawed Zhu Bajie, Sha Wujing’s demeanor is subdued and earnest.

He is less prone to the antics and disputes that sometimes ensnare his fellow disciples, showcasing a level of maturity and wisdom that stabilizes the group. His role is often that of the peacemaker, bridging gaps between his more temperamental companions and ensuring the pilgrimage remains focused on its spiritual goals.

Armed with a magic staff that he uses to combat demons and other threats, he is a formidable fighter in his own right. His knowledge of aquatic environments also proves invaluable, as many of the journey’s challenges take place near or in water.

The Journey to the West

The Origins

In the lush, mystical expanse of the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit, a stone egg, nurtured by the elements and the heavens, gave birth to Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. This miraculous birth marked the beginning of an extraordinary being destined to leave an indelible mark on the realms of gods and mortals alike. Possessing incredible strength, agility, and a keen intellect from birth, Sun Wukong quickly established himself as the king of the monkeys, securing their loyalty through his bravery and wisdom.

Driven by an insatiable curiosity and the fear of death, Sun Wukong embarked on a quest for immortality. His journey led him to the tutelage of a Taoist sage, from whom he learned the secrets of magical arts, shape-shifting, and the way of immortality. These newfound powers, coupled with his natural cunning and prowess, made Sun Wukong a being of unmatched ability.

However, with great power came a great desire for recognition and respect. Sun Wukong’s ambitions soon turned him against the celestial order. Seeking to claim his place among the gods and immortals, he caused havoc in the heavens, challenging the authority of the Jade Emperor himself. His antics and defiance led to a celestial war between his monkey army and the heavenly forces.

The turmoil caused by Sun Wukong could not go unpunished. Despite his might, he was eventually captured by the combined efforts of the Buddha and the celestial army. To curb his rebellious spirit, Buddha imprisoned Sun Wukong under the Five Elements Mountain, sealing him with a magical spell for five hundred years. This punishment was not just a consequence of his actions but also a pivotal moment of transformation. Under the mountain, Sun Wukong was forced to reflect on his deeds and the consequences of his unchecked ambition.

This period of imprisonment was a crucible, tempering Sun Wukong’s fiery spirit with a newfound understanding of responsibility and the importance of humility. It was here, in the shadow of his actions and under the weight of the mountain, that the foundation was laid for his redemption and eventual role as a protector on the journey to the West.

The Calling of Tang Sanzang

In the empire of the Tang Dynasty, under the watchful eyes of celestial beings, the birth of Tang Sanzang was foretold with a prophecy. He was destined to be no ordinary monk, but one whose journey would mark a pivotal moment in the spiritual fabric of the world. From an early age, Tang Sanzang displayed an uncommon devotion to his Buddhist faith, his heart set on understanding the deepest truths of existence and alleviating the suffering of all beings. His life was filled with piety, scholarship, and an unwavering commitment to the path of enlightenment, setting him apart as a vessel for divine purpose.

The turning point in Tang Sanzang’s life came through a divine revelation, where the Bodhisattva Guanyin presented him with a mission of paramount importance. He was to travel to the Western regions of India to retrieve sacred Buddhist scriptures not yet available in China . These texts held the key to deepening the spiritual understanding and salvation for countless souls in his homeland. This was not just a journey across lands; it was a pilgrimage that would test the limits of his faith, endurance, and spirit.

The gravity of this mission was clear; the scriptures were vital for the propagation of Buddhism in China, promising a new era of spiritual insight and enlightenment. However, the path to the West was fraught with perils beyond imagination—demons, treacherous landscapes, and trials that would challenge the very essence of his being. It was a journey that no one could undertake alone and survive, let alone succeed.

Recognizing the monumental challenges that lay ahead, the Bodhisattva Guanyin promised Tang Sanzang divine assistance in the form of disciples who would protect and guide him through the dangers. These disciples, each with their own paths to redemption and enlightenment, were destined to be united with Tang Sanzang, forming an unlikely fellowship bound by a shared mission.

Thus began Tang Sanzang’s journey, a quest that was not only his own but one that carried the hopes and spiritual aspirations of the entire Buddhist community. With the divine mandate bestowed upon him, Tang Sanzang set forth, stepping into the annals of legend.

Assembling the Disciples

As Tang Sanzang began his perilous journey to the West, the first to join him was none other than Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. Freed from his five-century imprisonment under the Five Elements Mountain by Tang Sanzang himself, Sun Wukong was bound to him by a vow. This vow, forged in the fires of redemption (and the head-tightening band), was Sun Wukong’s promise to protect Tang Sanzang throughout the journey. The release symbolized not only Sun Wukong’s second chance but also the formation of an unbreakable bond between the disciple and his master. With his unparalleled martial prowess and magical abilities, Sun Wukong was a formidable protector, one whose loyalty and dedication to Tang Sanzang’s mission were beyond question.

The next to join this celestial mission was Zhu Bajie, once a marshal in the heavens, now living as a half-human, half-pig being as punishment for his lascivious behavior in the celestial realm. Encountered by Tang Sanzang and Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie was persuaded to join the pilgrimage, seeking redemption for his past misdeeds.

Sha Wujing, the third disciple, was once a celestial general who, due to a grave mistake, was banished to a river, taking the form of a fearsome water ogre. His encounter with Tang Sanzang and the promise of redemption through service transformed Sha Wujing from a feared monster into a loyal disciple.

Together, these three disciples, each with their unique strengths, weaknesses, and backgrounds, formed the core of Tang Sanzang’s entourage. Their assembly was no mere coincidence but a divinely orchestrated gathering of souls seeking redemption, enlightenment, and the fulfillment of a sacred mission.

Trials and Tribulations

As Tang Sanzang and his newly assembled disciples embarked on their journey to the West, they were soon met with a series of trials that tested their resolve, unity, and individual capabilities. These challenges served not only as obstacles to be overcome but also as crucibles for character development and bonding among the pilgrims.

One of the first major trials they faced was the Black Wind Mountain, where a fierce demon known for capturing and eating travelers threatened their mission. It was here that Sun Wukong’s prowess and quick thinking were first put to the test, showcasing his ability to protect Tang Sanzang against seemingly insurmountable odds.

Another significant challenge came in the form of the White Bone Demon, a creature capable of changing its form to deceive and capture Tang Sanzang. This trial tested not only the physical strength of the disciples but also their wisdom and ability to see through deception.

These early trials also brought to the forefront the dynamics and interactions among the disciples. Sun Wukong’s impulsive nature and readiness to use force were often at odds with Tang Sanzang’s more compassionate and pacifistic approach, leading to tensions within the group. Zhu Bajie and Sha Wujing, each with their distinct personalities and strengths, found themselves navigating the complex dynamics between their desire for redemption and the often chaotic leadership of Sun Wukong.

The Final Challenges

As Tang Sanzang and his disciples neared the end of their epic quest to retrieve the sacred scriptures from the West, they encountered the Fiery Mountain, a vast barrier of flames that seemed insurmountable. This natural obstacle was a metaphor for the burning trials of the spirit, a test of their resolve and unity. To pass, they needed the fan of the Princess Iron Fan, a task that proved to be as much about diplomacy and wisdom as it was about strength and courage. The quest for the fan was marked by deception and challenges that tested their patience and ingenuity, especially for Sun Wukong, whose confrontations with the Princess pushed him to find non-violent solutions.

Following this, the pilgrims faced the ordeal of the Tenfold Maze, a bewildering labyrinth that tested their mental endurance and faith. The Maze, crafted by powerful magic, represented the inner confusions and doubts that can lead one astray from the path of enlightenment. Each turn and dead end forced the disciples to rely not just on Sun Wukong’s strength or Zhu Bajie’s might, but on Tang Sanzang’s unwavering faith and Sha Wujing’s quiet determination. It was their unity and collective wisdom that eventually led them through the maze, symbolizing the triumph of shared purpose over individual despair.

Perhaps the most significant trial came in the form of a spiritual challenge directly from the Buddha. Before granting them the scriptures, Buddha tasked Tang Sanzang and his disciples with a final test of their virtues and understanding of the Buddhist teachings. This trial was not about battling demons or overcoming physical barriers but confronting their inner selves and the essence of their journey. Each disciple, including Tang Sanzang, faced manifestations of their past errors, fears, and desires, challenging them to apply the lessons of compassion, humility, and perseverance they had learned on their journey.

The confrontation with their inner demons was a profound moment for the pilgrims, especially for Sun Wukong, whose journey from rebel to protector had been fraught with pride and anger. For Zhu Bajie, it was a moment to transcend his baser instincts and desires, while Sha Wujing confronted the solitude and obscurity of his existence with newfound peace. For Tang Sanzang, it was the ultimate test of his faith and his commitment to his mission, proving his worthiness to receive the sacred texts.

Arrival in the West

After overcoming the final, daunting challenges set before them, Tang Sanzang and his disciples reached their sacred destination in the West. It was here, in the presence of the Buddha, that they were finally granted the sacred scriptures.

The attainment of the sacred scriptures was an achievement of monumental significance. For Tang Sanzang, it represented the fulfillment of a divine mission entrusted to him, affirming his unwavering faith and dedication. The scriptures themselves were not just texts but beacons of wisdom, destined to enlighten countless generations to come. Their acquisition symbolized the bridging of divine knowledge from the West to the East, promising an era of spiritual awakening and understanding for Tang Sanzang’s homeland.

For the disciples, the journey to the West and the acquisition of the scriptures were transformative. Sun Wukong, once a rebellious figure driven by pride and the desire for immortality, emerged as a being of enlightenment, his actions tempered by wisdom and compassion. The journey refined his character, turning his immense power and cunning into instruments of protection and service to a cause greater than himself.

Upon their return to the Tang Empire, the pilgrims were received with reverence. The sacred scriptures were translated and spread, seeding the growth of Buddhism and its teachings throughout the land. The disciples, each awarded divine recognition for their service, achieved a form of enlightenment that transcended their former selves ( Both Sun Wukong and Tang Sanzang were turned into Buddhas .)

Summary of the Journey to the West

“Journey to the West” is a chronicling of the pilgrimage of the Buddhist monk Tang Sanzang and his quest to retrieve sacred scriptures from India. Alongside him are his three disciples: Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, with his unparalleled martial prowess and magical abilities; Zhu Bajie, the gluttonous and lecherous pig demon with a heart of gold; and Sha Wujing, the steadfast and reliable river demon. Each disciple, once celestial beings now seeking redemption for past transgressions, brings unique strengths and weaknesses to the journey, creating a dynamic and sometimes volatile mix of personalities.

The narrative begins with the birth and rise of Sun Wukong, who, after acquiring magical powers and challenging the heavens, is imprisoned under a mountain by the Buddha for his arrogance. Meanwhile, Tang Sanzang, chosen by the Bodhisattva Guanyin , embarks on a mission to the West to obtain Buddhist sutras that will enlighten the East. Along the way, he liberates and recruits Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing, who vow to protect him in exchange for their spiritual redemption.

Their journey is fraught with peril, encountering a series of demons and monsters intent on capturing Tang Sanzang for their own gain. Each challenge tests the group’s resolve, faith, and unity, with Sun Wukong’s quick wit and might often saving the day. Despite their differences and the difficulties they face, the pilgrims learn valuable lessons in compassion, patience, humility, and perseverance. These trials serve not only as physical obstacles but as spiritual tests, refining each disciple’s character and strengthening their bonds.

The pilgrimage is marked by significant trials, from battling the fiery Red Boy and outsmarting the cunning Spider Demons to navigating the treacherous Flaming Mountain and the illusion-filled Tenfold Maze. Each ordeal brings them closer together, teaching them the importance of teamwork, sacrifice, and the pursuit of enlightenment.

Upon reaching the West and passing the final tests set by the Buddha, Tang Sanzang and his disciples are granted the scriptures. Their return to the Tang Empire is triumphant, with each disciple achieving enlightenment and recognition for their service. The sacred texts they bring back promise a new era of spiritual awakening for their homeland.

- Loyalty and Devotion: The loyalty of Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing to Tang Sanzang is a central theme that underscores the importance of fidelity in the face of adversity. Their unwavering commitment to protect their master and ensure the successful retrieval of the sacred scriptures speaks to the value of loyalty in achieving a higher spiritual purpose.

- Perseverance through Trials: The pilgrims’ journey is fraught with challenges that test their resolve, faith, and endurance. Each trial, whether it be a confrontation with demons or overcoming natural obstacles, symbolizes the inner struggles individuals face on their path to enlightenment.

- The Quest for Enlightenment: At its heart, “Journey to the West” is a spiritual odyssey that mirrors the Buddhist path to enlightenment. The journey to retrieve the scriptures symbolizes the pursuit of wisdom and understanding, essential for liberation from suffering and the cycle of rebirth. The transformations of the characters, especially the disciples, reflect the individual’s journey toward enlightenment, marked by self-discovery, repentance, and spiritual growth.

- The Battle between Good and Evil: The frequent encounters with demons and the celestial trials faced by Tang Sanzang and his disciples embody the eternal struggle between good and evil. This theme is not only external, in the battles with literal demons, but also internal, representing the moral and spiritual conflicts within each character.

- Characters as Symbolic Archetypes: The main characters of “Journey to the West” are rich in symbolic significance. Sun Wukong, with his rebellious nature and transformative journey, symbolizes the untamed mind and the potential for enlightenment through discipline and self-cultivation. Zhu Bajie represents human desires and flaws, highlighting the struggles and potential for redemption despite one’s imperfections. Sha Wujing embodies steadfastness and humility, qualities essential for spiritual progress.

- Events as Metaphors for Spiritual Lessons: Many of the events and trials encountered by the pilgrims are metaphors for spiritual lessons. For example, the crossing of the Flaming Mountain can be seen as a metaphor for overcoming the burning passions and attachments that hinder spiritual growth. The encounters with various demons can represent the overcoming of personal obstacles on the path to enlightenment.

- The Journey Itself: The journey to the West is symbolic of the Buddhist path towards enlightenment. It is fraught with difficulties and distractions, much like the spiritual journey of an individual.

Moral Lessons

- Redemption and the Potential for Change : The characters of “Journey to the West,” especially the disciples of Tang Sanzang, embody the theme of redemption and the belief in the potential for change. Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing, each banished for their transgressions, find in their journey an opportunity for transformation. Their willingness to protect Tang Sanzang and endure hardships for the sake of obtaining the sacred scriptures illustrates the possibility of redemption, regardless of past misdeeds. This reflects the Buddhist concept of karma and the idea that positive actions can counteract negative past actions, leading to spiritual growth and liberation.

- Virtue and Moral Integrity : Throughout the novel, Tang Sanzang serves as a moral compass, embodying virtue and moral integrity. His compassion, patience, and unwavering commitment to non-violence, even in the face of danger, highlight the importance of upholding one’s principles. Tang Sanzang’s interactions with demons, often opting for understanding and conversion rather than conflict, reinforce the novel’s message that compassion and wisdom are more powerful than force.

- The Pursuit of Knowledge and Enlightenment : “Journey to the West” places great emphasis on the pursuit of knowledge and enlightenment, both as a personal quest and for the benefit of others. The journey to obtain the Buddhist scriptures symbolizes the quest for spiritual knowledge and truth. This quest is not portrayed as easy or straightforward but rather as a path filled with obstacles that require perseverance, sacrifice, and moral fortitude to overcome.

- Humility and Self-Cultivation : Finally, “Journey to the West” teaches the importance of humility and self-cultivation. The characters, particularly Sun Wukong, learn to temper their pride and recognize their limitations. This humility, coupled with a commitment to self-improvement and spiritual cultivation, is portrayed as essential for growth and enlightenment. The novel thus conveys the moral lesson that true strength and wisdom come from understanding oneself, acknowledging one’s flaws, and striving for self-betterment.

SHARE THIS POST

Read this next.

13 Exciting Things to Do in Niseko | Ultimate Travel Guide

13 Wonderful Things to Do in Nara | Ultimate Travel Guide

Discover the Secrets of Sanskrit | Why is It Powerful?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Hi, I’m Brandon

A conscious globe-trotter and an avid dreamer, I created this blog to inspire you to walk the Earth.

Through tales of travel, cultural appreciation, and spiritual insights, let’s dive into the Human Experience.

RECENT ARTICLES

5 Easy Steps to Create a Meaningful Sankalpa

The 4 Stages of Enlightenment in Buddhism | Simplified

How to Dissolve the Ego (Psychological & Spiritual Views)

Popular articles.

Meet the Ainu People | Japan’s Forgotten Indigenous Culture

Hanuman vs Sun Wukong | Get to Know the Divine Monkeys

13 Exciting Things to Do in Tagaytay | Epic Manila Day Trip

Taoism Simplified | Beliefs, Customs, Principles, and More

Subscribe for the latest blog drops, photography tips, and curious insights about the world.

© 2023 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

- Destinations

- Privacy Policy

Want to get in touch? Feel free to fill in the form below or drop me an e-mail at [email protected]

- Jul 2, 2022

Classical Chinese Novels 101: Journey to the West

For centuries, the literati of China wrote in Literary Chinese, crafted rigidly-structured essays, delighted in allusive poetry—and looked down on fiction as a lesser form of writing. Despite this, the stories and characters of China’s traditional novels have long influenced popular culture, and they are still readily apparent in both modern Chinese and East Asian culture.

This 101 series will serve as a basic introduction to China’s Four Great Classical Novels, as well as the entertainingly divergent (and often banned) Ming classic, Plum in the Golden Vase . In addition to discussing the development of Chinese long-form vernacular fiction, these articles will seek to present different critical interpretations of each novel, as well as highlight the insights that they offer into Chinese culture. As this series is designed for those without knowledge of Chinese or just beginning their studies of the language, Chinese names will be given in English, Chinese pinyin, and characters for the first appearance, and all subsequent references will use the English.

Classical Chinese Novels 101 is divided into six chapters:

1. Classical Chinese Novels 101: Introduction to the Traditional Chinese Novel

2. Classical Chinese Novels 101: The Romance of the Three Kingdoms

3. Classical Chinese Novels 101: Water Margin

4. Classical Chinese Novels 101: Journey to the West

5. Classical Chinese Novels 101: The Plum in the Golden Vase

6. Classical Chinese Novels 101: Dream of the Red Chamber

Journey to the West , or Xiyouji (西游记), is a late Ming dynasty (1368-1644) novel of comedic fantasy based on the religious pilgrimage of a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk to India in search of religious scripts. Published in the late 16th century, with the earliest extant edition dating back to 1592, Journey to the West is a hundred-chapter novel attributed to the author Wu Cheng’an.

As with Water Margin and Romance of the Three Kingdoms , the authorship of Journey to the West is still disputed (Hsia, 1968; Lee, 2010; Yu, 2008). Also like the earlier two novels, Journey to the West appears to be the lengthy culmination of a long history of narrative development. Based on the historical travels of Xuanzang, a monk who travelled to India in the early 7th century and brought back 657 Buddhist texts, the eventual folk legends that developed out of this historical pilgrimage gained ever-more fantastical elements through centuries of storytelling, from Song dynasty (960-1279) oral stories to Yuan (1271-1368) and Ming dynasty dramas (Hsia, 1968; Lee, 2010).

Though similar in development to Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin , Journey to the West represents an evolution in the traditional Chinese novel. While the ultimate identity of its author is still disputed, the novel itself is widely seen as the product of one primary author rather than a product of the type of composite authorship usually mentioned in relation to the earlier traditional novels. As the well-regarded Chinese literature professor Y. W. Ma writes, “There should not be much doubt that a single author is responsible for the extant one-hundred chapter version of the novel” (Ma, 1986:43). Indeed, Ma considers Journey to the West as one of the two novels that represent the height of Ming dynasty fiction (the second being Plum in the Golden Vase ) (Ma, 1986).

The basic structure and narrative of Journey to the West are, at first appearance, relatively simple and episodic. It begins with the tale of Sun Wukong, a monkey born from a stone who gains consciousness and then attempts to seek immortality and power. Sun Wukong, also called Monkey, rebels against Heaven and has a confrontation with the Buddha, who defeats Monkey and traps him beneath a mountain. Later, Tang Sanzang, courtesy name Tripitaka, is sent by the Tang Emperor on a mission west to find sacred Buddhist texts. Along his way, Tripitaka recruits companions who serve as his protectors and disciples; his first follower is the freed Monkey, who is bound to obey him by the Bodhisattva Guanyin (Guanyin, also a Chinese goddess of mercy, is an enlightened patron to the travellers; she appears recurringly to save them, and sometimes to test them.). His other companions are Zhu Bajie, or Pigsy in the acclaimed Arthur Waley abridged translation (1942), and Sha Wujing, or Sandy. Together, the pilgrimage members encounter and overcome (sometimes with the help of Guanyin) eighty-one trials involving demon-fighting and resisting temptation before reaching the end of their journey.

Despite its simple structure, the novel stands out among the traditional novels for its vivacious comedy and sense of fun. The 20th-century scholar and Chinese ambassador to the United States, Hu Shih, specifically emphasized the novel as a book of good humor and entertainment (Lee, 2010). Though Hu Shih was arguing for an appreciation of Journey to the West separate from its history of scrutiny and philosophical analysis, the novel is undeniably allegorical, philosophical, and rich with possible interpretations.

To begin with, Journey to the West is a novel based on the historical pilgrimage of Xuanzang. In addition to the religious journey where the main characters discuss Buddhist tenets with each other, the language of the novel borrows heavily from Taoist and Confucian texts, incorporating well-known ideas and phrases from the other two Chinese religions. For example, in his article “Formation and Fiction in Journey to the West ,” scholar Anthony Yu (2008) points out that the decision to make the fictional Tripitaka an envoy of the Tang emperor, a marked departure from the historical Xuanzang who went to India in secret and asked for pardon on his return, aligns the character more with the archetype of the traditional Confucian official-scholar. Furthermore, the character Tripitaka is far from the pious, calm traveller that one might expect given his fictional identity as either a reincarnated earth-bound dweller of Buddha’s Western Paradise, or as the fictionalized version of a devoutly religious historical pilgrim. Instead, as C. T. Hsia succinctly puts it, “he is merely helpless” (Hsia, 1968:117). A constant victim of the various ordeals the group faces, Tipitaka is nervous, fearful, and worried about completing his mission for the emperor, and requires continually rescuing. While Tripitaka’s weaknesses, complemented by Monkey’s endless mischievousness and Pigsy’s gluttony, are the main elements of comedy in the novel, they also serve greater allegorical purposes.

Many scholars, including C.T. Hsia (1968), Andrew Plaks (2015), and Anthony Yu (2008), highlight the division between Tripitaka as the all-too-human leader of the party and Monkey as the representation of the “mind” of the party in accordance with a Chinese idiomatic expression that refers to the “monkey of the mind.” This characterization of the party as separate parts of one being, supports an allegorical reading of Journey to the West which sees the eighty-one ordeals faced by the pilgrimage party, as well as the tensions between them as commentary on the proper cultivation of the heart and mind. Though Chinese expression about the "monkey of the mind" originated in Buddhist texts, by the time of Journey of the West, it was a syncretic Buddhist, Neo-Confucian and Taoist idea. At the same time, other allegorical readings focus on its treatment of Buddhist enlightenment. In The Four Masterworks of the Ming Novel , Andrew Plaks (2015) outlines how characteristics like Tripitaka’s concern for his own comfort, Pigsy’s gluttony and sensual desires, and Monkey’s quest for power are allegories for the different kinds of physical and spiritual impediments to Enlightenment. Hsia (1968) goes further in describing how Tripitaka’s continued attachments, both physical and spiritual, cause part of his susceptibility to demons' attacks and temptations; his compassion and other kindly emotions, while well-meaning, lead to more trouble. Meanwhile, Monkey’s humor, liveliness, and general disregard for others, which often offends Tripitaka’s sense of propriety and morality, is more truly aligned with Buddhist non-attachment.

In Hsia’s interpretation of the novel, the Heart Sutra received by Tripitaka at the beginning of his journey is the central message of the allegory (Hsia, 1968). The Heart Sutra teaches that “form is emptiness, and the very emptiness is form,” but Tripitaka and his fellow travellers show through their eighty-one ordeals that they are too attached to their comforts and desires (the form) (Hsia, 1968:119). Monkey, who more easily rejects his physical attachments—in one highly allegorical scene, he kills thieves called Ear, Eye, Nose, Tongue, Mind, and Body against Tripitaka's wishes—fails to find the enlightenment (the emptiness) described by the Heart Sutra because deliberately seeking enlightenment is also a form of attachment. The novel offers a representation of and commentary on the seeming paradox of attaining enlightenment (Hsia, 1968). Anthony Yu (2008) recalls other traditional interpretations of Journey to the West which indicate that the novel represents the Three-Religions-in-One ideology (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism) that was common among contemporary Ming scholars. Andrew Plaks, for his part, argues that the novel is ultimately a “ psychomania of the process of the cultivation of the mind as construed by sixteenth-century thinkers” (2015:258). In Plaks’ reading, the allegorical meaning of the novel is an exploration of the conflicts relating to the cultivation of the mind while playing with the available language and motifs of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism.

The various interpretations, or the arguments against excessive interpretations, aside, Journey to the West remains a beloved novel for its mixture of comedy and fantasy. Though the journey made by Tripitaka, Monkey, and the others is a story that has been retold countless times in Chinese and East Asian culture in dramas, movies, televisions shows, video games, and children's literature, English readers interested in becoming acquainted with this lively story can start with Arthur Waley’s translation before diving into the allegorical complexities of China’s three religions. Waley’s renamed version, Monkey , does great justice to the character who is arguably the most interesting and compelling figure of the novel: the fun, mischievous, and powerful Monkey King.

Bibliographical References

Hsia, C. T. (1968). The Classic Chinese Novel: A Critical Introduction = Zhongguo gudian xiaoshuo . New York Columbia University Press.

Lee, W. (2010). Full-Length Vernacular Fiction. In V. H. Mair (Ed.), The Columbia history of Chinese literature . Columbia University Press.

Ma, Y. W. (1986). Fiction. In W. H. Nienhauser (Ed.), The Indiana Companion to Chinese Literature (pp. 31–48). Indiana University Press.

Plaks, A. H. (2015). The Four Masterworks of the Ming Novel: Ssu ta ch’i-shu . Princeton University Press.

Yu, A. C. (2008). The Formation of Fiction in the “Journey to the West.” Asia Major , 21 (1), 15–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41649940

Visual Sources

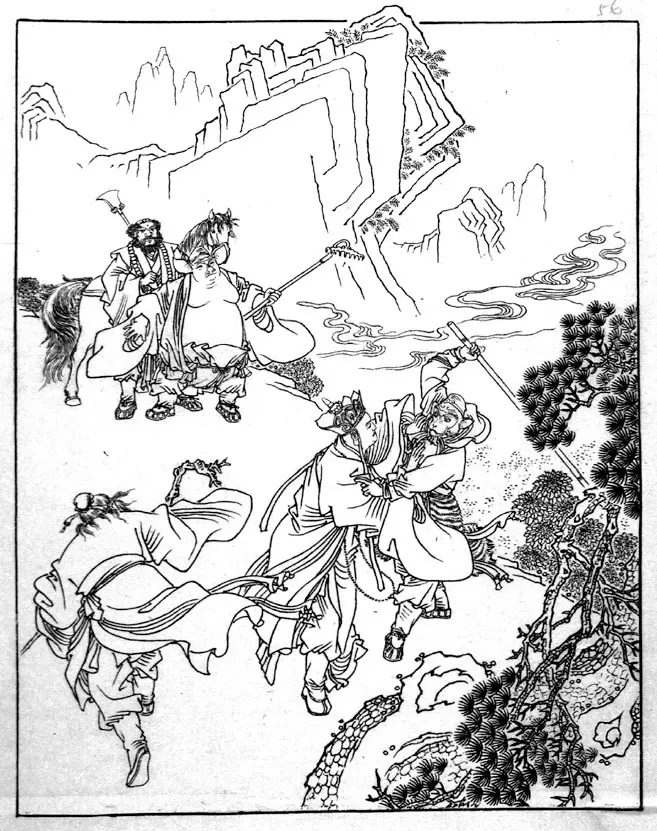

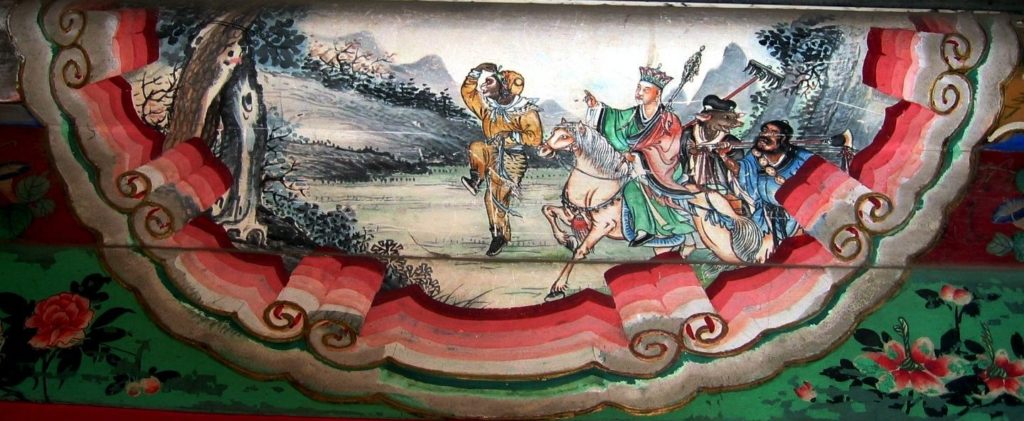

Figure 1: Yoshitoshi, T. (Early 1880s). Sun Wukong Blows on His Hairs [woodblock print; ink and color on paper]. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved June 30, 2022, from https://collections.mfa.org/objects/215182/sun-wukong-blows-on-his-hairs-goku-ke-o-fuku-jo-and-uba-

Figure 2: Unknown. (1690-1720). Monkey Battles the Spider Spirit [woodblock print]. The British Museum. Retrieved June 30, 2022, from https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1928-0323-0-20

Figure 3: Donshu, Ohara. (1815-1857). Priest Xuanzang and his attendants from the Xijouji [hanging scroll; ink and color on silk]. The British Museum. Retrieved June 30, 2022, from https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/36401001

Figure 4: Wiyono, L. D. (2014). Sun Wukong, the Infamous Monkey King [digital illustration]. Retrieved June 30, 2022, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/louisdavilla/14220881646/in/photostream/

Arcadia, has many categories starting from Literature to Science. If you liked this article and would like to read more, you can subscribe from below or click the bar and discover unique more experiences in our articles in many categories

Let the posts come to you.

Thanks for submitting!

If a monk acts rightly he will grow daily but invisibly, like grass in a garden during the spring, whereas an evildoer will be imperceptibly worn away day by day like a stone. — the Monk Tripitaka

Additional Document

- Themes and Goals

- Introduction to Journey to the West

- Summary and Structure of the Novel

- Teaching 2 Episodes from Chapter 14

- Episode A. The Six Bandits

- Episode B. The Golden Headband

- Journey to the West in World Literature

- Further Reading and Resources

- Acknowledgements

Many approaches can be taken to teaching excerpts from Journey to the West , a novel that incorporates the three major philosophies of China: Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism. This unit centers on Buddhist elements of the text, with the goal of providing instructors with materials for discussing in depth two specific passages from Chapter 14 which highlight Buddhist ideas.

Given the accessibility of the text, it works well in courses in world literature, world novel, and Asian studies, and could also form part of the reading list for courses in world religions. Given the late 16 th-century date of the text, it can be taught in the middle of a one-semester World Literature course or at the end or beginning of a course in World Literature I or II. Discussion questions and paper topics are provided for using the text in courses in World Literature I and II, comparing the text to others that might appear on those syllabi. (See also “ Journey to the West in World Literature Courses” below.)

The unit can be used by itself or in combination with the following other units on Buddhism in East Asia:

- “Foundations and Transformations of Buddhism” (see this unit for explanations of terms and basic concepts of Buddhism)

- “Buddhist Art in East Asia: Three Introductory Lessons towards Visual Literacy”

- “Buddhism and Japanese Aesthetics”

- “Dialogue and Transformation: Buddhism in Asian Philosophy”

“Background Information for Teaching Journey to the West” is designed to provide instructors with materials to enlarge their understanding of the text, whether spending one day on the teaching unit given, or one or two weeks on a larger reading selection from the novel.

Authorship of the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West (Xiyou Ji or Hsi-yu Chi) , has not been established beyond doubt, but most scholars accept attribution of the popular 100-chapter version to Wu Cheng’en (c.1500-c.1582), who wrote during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 C.E.). The novel was popularized in English through the abridged translation of Arthur Waley published as Monkey in 1943.

The novel reworks and expands on folk tales and dramatic and operatic episodes that sprang up around the historical journey of the Tang Dynasty Buddhist monk Xuanzang (596-664 C.E.) to India to bring the original Buddhist scriptures back to China. Xuanzang’s sixteen-year trip (629-645 C.E.) and his subsequent life-long dedication to translating the scriptures from Sanskrit into Chinese made him a legend in his own time. Unlike the fictional monk, the historical Xuanzang left China without the Emperor’s permission, but was honored on his return. In the fantastic and mystical stories developed about him, he collected a company of non-human immortal disciples, provided by the Bodhisattva Guanyin, to help on his journey. Monkey first appears as an escort during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 C.E.). Wu Cheng’en, in his masterful reworking of the folk materials, brings the disciple Monkey — the real hero of the novel — to the forefront (hence Waley’s choice of title), with the first seven chapters devoted to his biography.

Monkey, the hero of Journey to the West, is a popular figure of East Asian literature, opera, children’s books and cartoons, and television. Monkey masks, puppets, and even children’s costumes are available. Monkey is beloved for his martial prowess and supernatural powers, but it’s his rebel spirit, his complete fearlessness, his wiliness, and his devotion as a friend that make him the sidekick anyone would want to have along on life’s journey. In Journey to the West , the monk Xuanzang (Tripitaka) needs Monkey and his other disciples — or rather, they all need each other — to reach the goal. The novel can be read as adventure tale and satire, but the journey and the goal are Buddhist. Journey to the West is a wonderful vehicle for introducing students to Buddhist ideas through an endearing cast of characters and a story that works on multiple levels.

The novel falls into two main parts. Chapters 1-12 include Monkey’s history; the conversion of Monkey, Friar Sand, Pig and the White Dragon Horse to Buddhism by Guanyin and their promises to wait for the monk and accompany him on the journey. This first part also contains background on the Tang Emperor Taizong and his selection of Xuanzang (Tripitaka) to undertake the pilgrimage. Chapters 13-100 present the journey to the Western Paradise and obtainment of the scriptures. Master and disciples undergo the necessary 81 trials (the 9 x 9 of perfection), which include numerous encounters with wild beasts, supernatural monsters, and demons, as well as with various good and evil humans. They defeat the demons, often with supernatural help, and help to restore order in human societies. In the final three chapters, the pilgrims present the scriptures to Emperor Taizong and return to the Western Paradise for their rewards.

The “Six Bandits” and “Golden Headband” episodes from Chapter 14 provide an opportunity for a focused discussion of Buddhist elements in the novel. These two episodes could be covered in one class period. Provide students with a brief introduction to Buddhism prior to the unit. (See “Notes on Buddhist Elements” in “Background Information for Teaching Journey to the West” and the unit “Foundations and Transformations of Buddhism” )

The Bedford and Norton anthologies both include Chapter 14 in their selections, as does the anthology Western Literature in a World Context , ed. Paul Davis et al. All three use the Arthur Waley translation, and since that abridged text is the edition usually chosen by instructors who do not use an anthology, that translation is featured here. Since the Waley translation omits the introductory couplets and most of the poetry, some of the Chapter 14 poetry from the Jenner translation is provided here. (See the “Primary Text: English Translations” below for a complete list of available editions of Journey to the West and complete notes on the various English translations.)

Note: Instructors using an anthology might wish to assign the entire selection from Journey to the West featured in the anthology. Information provided in “The Pilgrim Characters” and “Supernatural Framework” in “Background Information for Teaching Journey to the West ” can assist in teaching other sections of the text than Chapter 14.

A. Student Readings

Waley, Arthur, trans. Monkey: Folk Novel of China by Wu Ch’eng-en. 1943. Reprint, New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1970.

This episode occurs at the beginning of Chapter 14. More precisely, within this chapter, the episode begins on page 131 about half-way down the page with the sentence: “They rose early the next day, and the old man brought them washing-water and breakfast.” The episode ends on page 133 with the sentence: “‘It’s no use trying to teach people like that,’ said Tripitaka to himself gloomily. ‘I only said a word or two, and off he goes. Very well then. Evidently it is not my fate to have a disciple; so I must get on as best I can without one.’”

Also provide students with the opening couplet to the chapter and the first stanza of the opening poem (not included in Waley).

Opening Couplet:

The Mind-Ape Returns to Truth The Six Bandits Disappear Without Trace.

First stanza of the opening poem:

Buddha is the mind, the mind is Buddha, Mind and Buddha have always needed things. When you know that there are no things and no mind Then you are a Buddha with a true mind and a Dharma* body.

Jenner, W. J. F., trans. Journey to the West. Wu Cheng’en. Intro. Shi Changyu. 4 vols. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2001 (1997-1986). Page 319.

*While Dharma is a complex term, it can be translated as the Law or the body of teachings of the Buddha, hence a pun on “body”; the physical body has become the teachings.

B. The Episode

The couplet: The Mind-Ape returns to Truth when Xuanzang frees Monkey from his five-hundred year captivity under the mountain and Monkey becomes his disciple on the journey.

Shortly into the journey, in early winter, Master and disciple are beset by a gang of bandits. Monkey says he’s never heard of them, so they give their names: “The first of us is called Eye that Sees and Delights; the second, Ear that Hears and is Angry; the third, Nose that Smells and Covets; the fourth, Tongue that Tastes and Desires; the fifth, Mind that Conceives and Lusts; the sixth, Body that Supports and Suffers” (Waley 132). Monkey kills them all, much to Tripitaka’s dismay. Reminding him that, “A priest . . . should be ready to die rather than commit acts of violence” (132-33), Tripitaka tells him that he is evil, this is a bad start, and he can’t come with him to India. Monkey, who felt he deserved thanks for saving their lives, leaves in a huff. Tripitaka was trying to correct Monkey, not send him away, and is discouraged about how to continue the journey without him.

C. Buddhist Context

In Buddhism, the Six Bandits represent the six cauras , the six senses of the body that, when factors of attachment, impede enlightenment. “Monkey’s execution of them is intended to portray in an allegorical fashion his greater detachment from the human senses, a freedom of which his master . . . [has] little knowledge” (“Introduction,” Anthony C. Yu, trans. and ed. The Journey to the West. Vol 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977, 59.) Xuanzang’s compassion gets in the way of his perception; his attachment to the phenomenal world prevents him from seeing the bandits for what they are. The six cauras can be compared with the Christian Seven Deadly Sins of pride, envy, wrath, avarice, gluttony, and lechery, which can kill the spirit. In contrast to the six cauras are the six paramitas, the virtues of generosity, morality, patience, vigor, meditation, and wisdom that carry all beings beyond the world of suffering. The Christian virtues that can overcome the Seven Deadly Sins are humility, loving kindness, gentleness, diligence, generosity, temperance, and chastity.

D. Class Discussion

The following questions can be discussed in pairs, groups, as a class, or used for journal entries.

1. Should Monkey have killed the bandits or could he have merely chased them away, as Tripitaka suggests? Monkey maintains the bandits would have killed them and that would have been the end of the mission; consider the allegorical nature of the bandits. 2. Should Tripitaka have scolded Monkey so severely, or should he have extended the pity and compassion he has for the bandits to Monkey as well, and listened to his defense? 3. Did Monkey really kill the six senses if he can get so angry at Tripitaka that he is willing to forget his promise and leave in a huff? 4. Is the couplet that introduces the chapter true? Have the Six Bandits disappeared without trace? What is the relationship of the opening poem?

Students are usually interested in discussing the Buddhist emphasis on freeing the mind from delusion and freeing the self from desire. Is what we call reality really delusion? Aren’t beauty, music, and good smells and tastes part of the joy of being human? Is it possible/do we really want to free ourselves from desire? Depending on your class, some students may relate these ideas to other religious traditions, such as the role of the senses in the seven deadly sins of Christianity, as noted in “Buddhist Context” above.

This episode also provides a good opportunity to discuss the Heart Sutra. See “The Heart Sutra” in “Background Information for Teaching Journey to the West” for the text of the sutra, as well as information for the instructor.

E. Comments

As the pilgrims progress on the journey, they are often beset by demons that attack the senses, and Tripitaka’s compassion frequently prevents him from perceiving evil. Note that Waley often chooses words that echo Christian ideas, as with “covets” and “lusts” in the bandits’ self-descriptions. Even when they understand the allegory, many students will still take the side of Tripitaka, because a Buddhist should not kill. This is underscored by an episode in Chapter 57, when Monkey once again kills a group of bandits. In this case, however, they are human bandits, one of whom is the son of a farmer who offered them hospitality. Tripitaka dismisses Monkey, who goes to the Bodhisattva to complain. She points out to him that the monk’s “heart is set on kindness. Why did someone of your tremendous powers need to bother with killing so many small-time bandits? . . . they’re human and it’s wrong to kill them. It’s not the same as with evil beasts, demons and spirits” (Jenner, W. J. F., trans. Journey to the West. Wu Cheng’en. 4 vols. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2001 (1997-1986), 1299.) At this early point in the journey, neither Tripitaka nor Monkey seem to have internalized the teaching of “no things and no mind” found in the opening poem. Students should be aware of the paradoxes raised in the text and should not feel complacent about finding one “right answer” to the inherent complexities in the text.

This episode, also from Chapter 14, begins about half-way down page 134 with the sentence: “After Monkey left the Master, he somersaulted through the clouds and landed right in the palace of the Dragon King of the Eastern Ocean.” The episode concludes at the end of Chapter 14; the last lines of the Chapter/episode on p. 137 read: “Very crestfallen, Monkey put the luggage together, and they started off again towards the west. If you do not know how the story goes on, you must listen to what is told in the next chapter.”

When Monkey leaves Tripitaka, he intends to go home to the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit, but he stops for a cup of tea with the Dragon King of the Eastern Ocean. Asking the Dragon King about a painting on his wall, he hears the story of the humble, dedicated disciple, Chang Liang, who repeatedly fetches his master Shih Kung’s shoe from the water. The Dragon King reminds Monkey he needs to have more patience, learn to control himself, and submit to the will of others if he is to gain the Fruits of Illumination. Monkey decides to return to Tripitaka at once (Waldron, 135).

Meanwhile, the Bodhisattva Kuan-yin, disguised as an old woman, visits the disconsolate Tripitaka. She provides him with a brocade coat and embroidered cap, and a magic spell to tighten the golden band inside the cap. Once Monkey puts on the cap, “If he disobeys you, say the spell, and he’ll give no more trouble and never dare to leave you” (134). When Monkey returns, he finds Tripitaka sitting dejectedly along the roadside. Tripitaka tells him, “I hadn’t the heart to go on, and was just sitting here waiting for you” (135). Monkey is the mind/heart; without him, Tripitaka can make no progress.

When Monkey spots the pretty clothes, Tripitaka tells him, “Anyone who wears this cap can recite scriptures without having to learn them. Anyone who wears this coat can perform ceremonies without having practised them” (135-36). Monkey asks to put them on, Tripitaka recites the spell, and Monkey rolls on the ground in pain. Tripitaka recites three times before Monkey realizes that Tripitaka has a spell. He promises that in future, he will listen to Tripitaka and obey him, but Monkey is so angry, he rushes to attack him, and Tripitaka must once more recite the spell. When he learns Tripitaka received these from Kuan-yin, he’s angry at her as well. Finally, the contrite Monkey says, “Master, this spell is too much for me. Let me go with you to India. You won’t need to be always saying this spell. I will protect you faithfully to the end” (136-37). And they set out.

C. Discussion Questions

The following questions can be discussed in pairs, groups, as a class, or used for journal entries. Some critics have seen the use of the golden band as taking away Monkey’s spirit and independence; students enjoy debating Monkey’s submission to Tripitaka on this point.

1. Does Monkey lose his freedom and individuality as a result of the golden band and his submission to Tripitaka? Why is it necessary to control Monkey mind? Instructor’s note: In a complete reading of the novel, we find that Monkey functions quite independently and with all his usual spirit throughout one hundred chapters. 2. How does Monkey’s perception of Tripitaka change? Does his conversion finally seem genuine? Instructor’s note: As a result of this episode, what changes is Monkey’s perception of Tripitaka and of the journey. After the struggle with Tripitaka, Monkey totally dedicates himself to his Master and to the goal of the journey. Whereas formerly he was the center of every enterprise in which he involved himself, now his Master and the goal of the journey become his central focus. 3. What does Monkey stand to gain by accompanying Tripitaka on the journey? Instructor’s note: Monkey had voluntarily returned to Tripitaka and he wants to cultivate retribution and earn his heavenly rewards.

For colleges which offer only one course in world literature, Journey to the West will fall in about the middle of the course. For colleges which offer World Literature I and II, the text can be taught either at the end of the first course or the beginning of the second, given its late 16 th-century date. The Norton Anthology places it at the beginning of the second set of volumes (Volume D), World Literature II. However, the Bedford Anthology places it at the end of Book 3, which places it in World Literature I. Teacher’s Guides available for the various anthologies offer numerous suggestions for structuring the course syllabus and comparing various texts. The suggestions below are for paper topics or extended course discussion or exams. They can be adapted according to the teacher’s selection of anthology, texts, dates covered, and course focus, or may just help spark ideas.

Students may be asked to choose one of the topics and write a focused essay of 3-5 pages, citing specific passages from the texts to support and illustrate their points.

Topics for World Literature I

1. Homer’s Odyssey , Virgil’s Aeneid, and Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West all involve lengthy journeys. Choosing one of the first two texts and Journey to the West , compare and contrast the texts, considering the following: motives for the journey; the companionship or lack thereof and effect of this on progress of the journey; problems encountered and how they are resolved; and what it means to the main character(s) to reach the goal. Finally, offer some ideas on how the different cultures reflected in the texts affect the various outcomes and/or philosophies presented.

2. There is lack of consensus on whether or not Hanuman, the Monkey King in The Ramayana , may have influenced the development of the Monkey King of Chinese folklore and Journey to the West . Using the selections we’ve read, compare the roles these two characters play in their respective texts and compare and contrast their respective characteristics and actions. Based on what you discover in this process, offer your own opinion as to whether the earlier portrait from India might have influenced the Chinese Monkey King.

3. Using the ideas either from Confucius, Analects , or Lao Zi, Dao De Jing, analyze how Confucian or Daoist ideas inform Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West . For example, you might apply Confucian ideas of community and human relationships, or Daoist ideas of non-action and following the Dao, etc. Be very specific in applying and citing the earlier texts to show that this is a Confucian or Daoist journey.

Topics for World Literature II

1. For both Voltaire’s Candide and Wu Cheng’en’s Monkey, the relationships these characters have with their fellow travelers are important. Using specific relationships, discuss the idea of community, friendship, and love or respect, and the importance of these values to the main characters and to their motives and actions. [Note: The differences in meaning of the term “Enlightenment” for the contexts of these works should be discussed in class, or could be incorporated into this paper topic.]

2. Matsuo Basho, in his Narrow Road of the Interior , says that for many, “travel is life, travel is home” (Norton Anthology, Vol. D, 607). The travelers in works we have read have various motives for undertaking their travels and for continuing them. They encounter a variety of adventures and undergo a range of emotions. Choose either Voltaire’s Candide or Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and compare and contrast the travelers’ motives and their views and feeling about what they observe and experience with that of the travelers in Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West. Is travel “life” and/or “home” for any of these travelers? Explain your conclusions as fully as possible.

3. Several of the characters in texts we have read are looked up to as authoritative figures by others in the work: Pangloss, the Monk Tripitaka, Kuan-yin, Master Houyhnhnm. Choosing two or three of these figures, from at least two different texts and cultures, explain what it is that gives the characters authority, what others expect of them or how they regard them, and what influence they have on the course of events. Does the view of these characters’ authority change over the course of the selection, and if so, why? Given the satire in these works, does the reader (do you) perceive the bases for authority and the authoritative figures in the same light as do the characters within the works?

A. Primary Text: English Translations

The major translators have been Arthur Waley (1943), Anthony Yu (who withholds authorial attribution to Wu, 1977) and W.J.F Jenner (2001; 1977-1986). An abridged “retelling” by David Kherdian was published in 2000.

Jenner, W. J. F., trans. Journey to the West. Wu Cheng’en. Intro. Shi Changyu. 4 vols. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2001 (1997-1986).

This is the most recent complete translation. It’s quite colloquial and the Chinese names are given in pinyin, the current transliteration usage internationally. (Jenner also translates more Chinese proper nouns into English and Sanskrit names into Chinese than does Yu.) The prose and poetry are dynamic, accessible to students, and fun. It’s available only in the four-volume slip-cased set, not in any of the anthologies. For a course in Asian studies or world novel, where more time can be spent on the text, instructors may want to consider using this translation.

Kherdian, David. Monkey: A Journey to the West. A retelling of the Chinese folk novel by Wu Ch’eng-en. Boston & London: Shambhala, 2000.

This edition mimics the Waley in providing a condensed version for classroom use; major selections are from Chapters 1-7, 14, 59-61, and 98-100. Like Waley, Kherdian omits the introductory couplets, most of the poetry, and the Heart Sutra. Includes lovely black and white reproductions of the woodblock illustrations of Hokusai (1760-1849) and other artists from an 1833 Japanese retelling.

The edition that popularized the novel; provides most of thirty chapters, but omits most of the poetry, the introductory couplets, and the Heart Sutra. Waley’s translation is anthologized in the following: The Bedford Anthology of World Literature. Book 3: The Early Modern World, 1450- 1650. Ed. Paul Davis et al. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004. 832-911. ( Ch. 8, from Ch. 12-13, Ch. 14, 16-21, from Ch. 22, 28). Literatures of Asia From Antiquity to the Present. Ed. Tony Barnstone. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003. 341-357 ( Ch. 1-2). Literatures of Asia, Africa, and Latin America From Antiquity to the Present . Ed. Willis Barnstone and Tony Barnstone. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999. 338-355. ( Ch. 1-2). The Norton Anthology of World Literature, Vol. D: 1650-1800. 2 nd ed. Ed. Sarah Lawall. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2002. 8-71. (Ch 1, 14-21). Western Literature in a World Context. Vol. 1: The Ancient World through the Renaissance. Ed. Paul Davis et al. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995. 2134-2202. ( Ch. 8; from Ch. 12-13; Ch. 14-21; from Ch. 22, 28). The World of Literature. Ed. Louise Westling et al. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999. 1049-1060. (from Ch. 16, Ch. 17).

Yu, Anthony C., trans. and ed. The Journey to the West. 4 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Yu’s four-volume set is the first complete English translation. The introduction and notes are scholarly, detailed, and extensive. This translation is highly recommended to the instructor and advanced students for its detailed background and explication. However, these features — and the expense of the individual volumes — make this edition most appropriate only for upper-level or graduate courses. Yu uses the old Wade/Giles transliteration of Chinese names. Yu’s translation is anthologized in the following: The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature. Ed. Victor H. Mair. New York: Columbia UP, 1994. 966-980. ( Ch. 7). The Longman Anthology of World Literature, Vol. C: The Early Modern Period. Ed. Jane Tylus and David Damrosch. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 30-107. (from Ch. 1, 2, 7, 8, 12; Ch. 53; from 69-72, 98, 99, 100).

B. Critical Commentary and Background

Adams, Roberta E. “Aspects of Authority in Wu Cheng-en’s Journey to the West .” Chinese Cultures of Authority . Ed. Roger T. Ames and Peter Hershock. Albany: SUNY Press, Forthcoming Spring 2006.

Bantly, Francisca Cho. “Buddhist Allegory in the Journey to the West .” The Journal of Asian Studies 48:3 (1989): 512-24.

Campany, Rob. “Cosmogony and Self-Cultivation: The Demonic and the Ethical in Two Chinese Novels.” Journal of Religious Ethics 14:1 (1986): 81-112. de Bary, Wm. Theodore and Irene Bloom, comps. “The School of Consciousness-Only.” In Sources of Chinese Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999. 2nd ed., Vol. I: 440-44.

Dudbridge, Glen. “The Hundred-Chapter Hsi-yu chi and Its Early Versions.” Asia Major . n.s. 14:2 (1969): 141-91.

Hsia, C. T. The Classic Chinese Novel: A Critical Introduction. New York: Columbia University Press, 1968.

Liu, I-Ming. “How to Read “The Original Intent of the Journey to the West,” Trans. Anthony C.

Yu, In David L. Rolston, ed. How to Read the Chinese Novel. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. 299-315.

Plaks, Andrew H. “Allegory in Hsi-Yu Chi and Hung-Lou Meng .” In Chinese Narrative: Critical and Theoretical Essays. Ed. Andrew H. Plaks. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977. 163-202.

*-----. The Four Masterworks of the Ming Novel. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

-----. “ The Journey to the West .” In Masterworks of Asian Literature in Comparative Perspective: A Guide for Teaching. Ed. Barbara Stoler Miller. Columbia Project on Asia in the Core Curriculum. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1994. 272-284.

Shi, Changyu. Introduction to Journey to the West . Wu Cheng’en. Trans. W. J. F. Jenner. 4 vols. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2001.

Waley, Arthur. The Real Tripitaka and Other Pieces. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1952.

Wriggins, Sally Hovey. Xuanzang: A Buddhist Pilgrim on the Silk Road. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996.

Journey to the West . Animated video, 52 episodes on 28 VCDs. China Central Television (CCTV).MandarinChinese. 1999. Distributed by ChinaSprout. ( www.chinasprout.com )

Journey to the West: Legends of the Monkey King. Animated video, 72 minutes. China Central Television (CCTV)/Cinar Productions, 2001. English version from the 1999 Chinese TV series. Distributed in the U.S. by ChinaSprout, Inc. ( www.chinasprout.com ).

D. Children’s Illustrated Books in English

The Making of Monkey King. English/Chinese. Retold by Robert Kraus and Debby Chen. Illustrated by Wenhai Ma. Adventures of Monkey King, Vol. 1. Union City, CA: Pan Asian Publications, 1998.

Monkey King Wreaks Havoc in Heaven . English/Chinese. Retold by Debby Chen. Illustrated by Wenhai Ma. Adventures of Monkey King, Vol. 2. Scarborough, Ontario: Pan Asian Publications, 2001.

E. Selected Internet Resources (including images)

China the Beautiful: “Monkey-Journey to the West” http://www.chinapage.com/monkey/monkey.html

Includes several illustrations for Journey to the West and Chapters 1-8 in Chinese.

ChinaSprout, Inc. ( Brooklyn, NY) http://www.chinasprout.com .

A site for purchasing children’s books, videos, puppets, papercuts, masks, children’s T-shirts and costumes, and the complete set of 52 episodes of the animated Chinese TV production (28 VCDs in Mandarin Chinese).

Monkey Heaven http://www.monkeyheaven.com/

This frequently updated UK site is “a tribute to the cult classic live action Japanese TV series . . . made by NTV in the late 1970s.” It provides information on the series as dubbed into English and aired in the UK, giving broadcast schedules, DVD Box sets for purchase, and links to numerous other Internet sites for Monkey TV fans, including Monkey gifts to purchase.

http://www.std.org/strubin/ccc/monkey.html

Features a nice image of the pilgrims from a Chinese language website.

Two years ago, after teaching Journey to the West in a World Literature II class, I realized the inadequacy of my answers to student questions about the text and its background. That summer, I read the entire 2000-plus pages, comparing the Jenner and Yu translations, and as much criticism as I could locate in English. This initial work on Journey to the West became the basis for an article for the on-line conference, “Cultures of Authority,” sponsored by the Asian Studies Development Program, September 2003. I have used materials from that article, which will appear in a published collection from the conference, in this unit. Both my article and this unit are especially indebted to the work of Anthony Yu, C.T. Hsia, and Andrew Plaks.

back to top

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The journey to the west: a platform for learning about china past and present.

In US college students’ first course on China, the challenge for instructors is to pack the maximum amount of punch into the experience so that the course will inspire them to seek more opportunities to learn about China at and beyond the college level. One way to achieve this goal is to use a rich text with many applications to help students unpack the complexities of Chinese history, language, politics, economics, and thought. For this purpose, the sixteenth-century novel The Journey to the West, with its many incarnations, is ideal. 1 It features a rousing adventure story, which can be read as historical fiction, political satire, and religious allegory. The novel has been reproduced for many types of audiences in many different media, including children’s books, puppet shows, operas, comics, TV series, and movies; each version is different enough to allow instructors to discuss them in the context of important Chinese historical events and cultural elements. Because well-told stories help us make sense of the world, instructors can use this novel as a foundational element to facilitate students’ connections with and between the various elements of the course. In this article, we show how The Journey to the West and its multiple incarnations can be used to help students unpack the complexities of China as a subject and develop a critical awareness or appreciation for a culture different from their own. We first show how the story may be introduced in a way that sets students’ minds for embracing the immense complexity of humanity and Chinese culture. Then, we show how various elements and incarnations of the story can be used to facilitate discussions about some outstanding aspects of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Maoist China (1949–1976), and postreform Communist China.

A Glance at The Journey to the West

Developed into its full length in the sixteenth century, the 100-chapter novel The Journey to the West (The Journey hereafter) is believed to have its historical basis in the epic pilgrimage of the monk Xuanzang (c. 596–664) to India and has been a popular subject for storytellers since the late Tang dynasty. The fictionalized pilgrimage as depicted in the novel sees Xuanzang accompanied by four nonhuman disciples: Monkey, Pigsy, Sandy, and Dragon Horse. The four disciples have been expelled by the Daoist Celestial Court (i.e., Heaven) due to misbehaviors, but will beaccepted by the Bodhisattva Guanyin (AKA the Goddess of Mercy) into Buddhism on condition that they promise to assist Xuanzang’s pilgrimage.

The mischievous Monkey character and his dedicated master Xuanzang have the central roles in the novel, and the first thirteen chapters establish the backstories of how the two became destined for the journey. The exciting part of the tale begins in chapter 14, when Xuanzang releases Monkey from a mountain and together they embark on a journey filled with the humor of Monkey’s mischievous battles against bandits and demons, interspersed with moments of Buddhist enlightenment. Starting here, students get a taste of the original novel and are introduced to the two main characters. A useful in-class exercise is to brainstorm words to describe the two characters. Through this activity, students come to understand the complexity and contrast of the characters’ personalities and why this dynamic is so important not only for the success of the story, but also metaphorically for understanding the complex nature of Chinese culture and society. For example, how have the three distinct and often-contradictory teachings—Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism—been able to operate relatively harmoniously in the lived religious experience of everyday Chinese? An understanding of how each individual has contradictory tendencies and how a story needs such individuals to be successful will set students’ minds for embracing the complexity of the topics to be discussed in the course, such as the various adaptations of Monkey and The Journey, and how they relate to different aspects of China.

Learning about Traditional China through The Journey

Written in the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and based on a true event during the Tang dynasty (618–907), The Journey offers the opportunity to introduce two of the “golden eras” in Chinese history. With almost 4,000 years of written history, there is a lot of Chinese history to potentially cover, but for a course that seeks to introduce China studies through multiple disciplinary lenses, a focus on the Ming dynasty, alongside the more recent events of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, may suffice. The chapter on the Ming in Patricia Ebrey’s Cambridge Illustrated History of China offers a vivid depiction of Ming society. 2 After reading the chapter and watching episodes 2 and 3 from the 1986 TV series of The Journey , students can quickly map the hierarchical structure of the court of the Ming government onto that of the Celestial Court in The Journey . 3 Students can also connect Monkey’s eagerness to seek a position in the Celestial Court with the civil service examination in the Ming dynasty. 4 From these connections, students can get a sense of China’s hierarchical social structure and its traditional emphasis on self-improvement through education. These connections serve as foundations for students to understand the historical continuities and differences when discussing the political structure and educational system of contemporary China.

The history of the Ming dynasty is also important because it is one of the wealthiest eras in China’s history and has some interesting correlations with contemporary China, such as both being periods of international economic interactions. Employing The Journey as a fictional account of history offers a unique opportunity for the correspondences and differences between traditional and contemporary China to be highlighted and analyzed.

The syncretism of the three major teachings of traditional China, namely Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, culminated when Ming General and statesman Wang Yangming’s (1472–1529) teaching of “learning of the mind” became popularized in the empire. Inspired by Chan (Japanese, Zen) Buddhist philosophy, Wang emphasized that a true understanding of the essence of morality can only be achieved through cultivating one’s own mind, which means persistent personal enactment of moral principles. The Journey depicts the lived religious experience of everyday Chinese. To help appreciate the interplay of belief systems, students can read Asian Studies Professor Joseph Adler’s Chinese Religious Traditions , accompanied by some application exercises to highlight the distinct reasoning patterns of the three major teachings. Such application exercises might include asking students to play the roles of hardcore Confucianists, Daoists, and Buddhists, who are requested to comment on such phenomena as family reverence, gender roles, death, humanity, and the vicissitudes of life.

At this point, students begin to realize that the journey actually represents the ongoing effort to end attachment to worldly things such as fame and money, which often make the mind susceptible to moral corruption. Students will also be able to identify the Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist elements as they read other selected chapters from the novel and view other adaptations of the story, such as the movie Conquering the Demons . 5 Conquering the Demons is a fun movie to watch, and it presents a lively and modern interpretation of The Journey as Buddhist allegory. 6