KATHERINE TURNER, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(6):347-353

Related letter: Well-Child Visits Provide Physicians Opportunity to Deliver Interconception Care to Mothers

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

The well-child visit allows for comprehensive assessment of a child and the opportunity for further evaluation if abnormalities are detected. A complete history during the well-child visit includes information about birth history; prior screenings; diet; sleep; dental care; and medical, surgical, family, and social histories. A head-to-toe examination should be performed, including a review of growth. Immunizations should be reviewed and updated as appropriate. Screening for postpartum depression in mothers of infants up to six months of age is recommended. Based on expert opinion, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends developmental surveillance at each visit, with formal developmental screening at nine, 18, and 30 months and autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. Well-child visits provide the opportunity to answer parents' or caregivers' questions and to provide age-appropriate guidance. Car seats should remain rear facing until two years of age or until the height or weight limit for the seat is reached. Fluoride use, limiting or avoiding juice, and weaning to a cup by 12 months of age may improve dental health. A one-time vision screening between three and five years of age is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to detect amblyopia. The American Academy of Pediatrics guideline based on expert opinion recommends that screen time be avoided, with the exception of video chatting, in children younger than 18 months and limited to one hour per day for children two to five years of age. Cessation of breastfeeding before six months and transition to solid foods before six months are associated with childhood obesity. Juice and sugar-sweetened beverages should be avoided before one year of age and provided only in limited quantities for children older than one year.

Well-child visits for infants and young children (up to five years) provide opportunities for physicians to screen for medical problems (including psychosocial concerns), to provide anticipatory guidance, and to promote good health. The visits also allow the family physician to establish a relationship with the parents or caregivers. This article reviews the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines for screenings and recommendations for infants and young children. Family physicians should prioritize interventions with the strongest evidence for patient-oriented outcomes, such as immunizations, postpartum depression screening, and vision screening.

Clinical Examination

The history should include a brief review of birth history; prematurity can be associated with complex medical conditions. 1 Evaluate breastfed infants for any feeding problems, 2 and assess formula-fed infants for type and quantity of iron-fortified formula being given. 3 For children eating solid foods, feeding history should include everything the child eats and drinks. Sleep, urination, defecation, nutrition, dental care, and child safety should be reviewed. Medical, surgical, family, and social histories should be reviewed and updated. For newborns, review the results of all newborn screening tests ( Table 1 4 – 7 ) and schedule follow-up visits as necessary. 2

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A comprehensive head-to-toe examination should be completed at each well-child visit. Interval growth should be reviewed by using appropriate age, sex, and gestational age growth charts for height, weight, head circumference, and body mass index if 24 months or older. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-recommended growth charts can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/who_charts.htm#The%20WHO%20Growth%20Charts . Percentiles and observations of changes along the chart's curve should be assessed at every visit. Include assessment of parent/caregiver-child interactions and potential signs of abuse such as bruises on uncommonly injured areas, burns, human bite marks, bruises on nonmobile infants, or multiple injuries at different healing stages. 8

The USPSTF and AAP screening recommendations are outlined in Table 2 . 3 , 9 – 27 A summary of AAP recommendations can be found at https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/periodicity_schedule.pdf . The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) generally adheres to USPSTF recommendations. 28

MATERNAL DEPRESSION

Prevalence of postpartum depression is around 12%, 22 and its presence can impair infant development. The USPSTF and AAP recommend using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/1015/p926.html#afp20101015p926-f1 ) or the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/0115/p139.html#afp20120115p139-t3 ) to screen for maternal depression. The USPSTF does not specify a screening schedule; however, based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends screening mothers at the one-, two-, four-, and six-month well-child visits, with further evaluation for positive results. 23 There are no recommendations to screen other caregivers if the mother is not present at the well-child visit.

PSYCHOSOCIAL

With nearly one-half of children in the United States living at or near the poverty level, assessing home safety, food security, and access to safe drinking water can improve awareness of psychosocial problems, with referrals to appropriate agencies for those with positive results. 29 The prevalence of mental health disorders (i.e., primarily anxiety, depression, behavioral disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) in preschool-aged children is around 6%. 30 Risk factors for these disorders include having a lower socioeconomic status, being a member of an ethnic minority, and having a non–English-speaking parent or primary caregiver. 25 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence regarding screening for depression in children up to 11 years of age. 24 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends that physicians consider screening, although screening in young children has not been validated or standardized. 25

DEVELOPMENT AND SURVEILLANCE

Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends early identification of developmental delays 14 and autism 10 ; however, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend formal developmental screening 13 or autism-specific screening 9 if the parents/caregivers or physician have no concerns. If physicians choose to screen, developmental surveillance of language, communication, gross and fine movements, social/emotional development, and cognitive/problem-solving skills should occur at each visit by eliciting parental or caregiver concerns, obtaining interval developmental history, and observing the child. Any area of concern should be evaluated with a formal developmental screening tool, such as Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Parents' Evaluation of Developmental Status, Parents' Evaluation of Developmental Status-Developmental Milestones, or Survey of Well-Being of Young Children. These tools can be found at https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Screening/Pages/Screening-Tools.aspx . If results are abnormal, consider intervention or referral to early intervention services. The AAP recommends completing the previously mentioned formal screening tools at nine-, 18-, and 30-month well-child visits. 14

The AAP also recommends autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months. 10 The USPSTF recommends using the two-step Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) screening tool (available at https://m-chat.org/ ) if a physician chooses to screen a patient for autism. 10 The M-CHAT can be incorporated into the electronic medical record, with the possibility of the parent or caregiver completing the questionnaire through the patient portal before the office visit.

IRON DEFICIENCY

Multiple reports have associated iron deficiency with impaired neurodevelopment. Therefore, it is essential to ensure adequate iron intake. Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends supplements for preterm infants beginning at one month of age and exclusively breastfed term infants at six months of age. 3 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for iron deficiency in infants. 19 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends measuring a child's hemoglobin level at 12 months of age. 3

Lead poisoning and elevated lead blood levels are prevalent in young children. The AAP and CDC recommend a targeted screening approach. The AAP recommends screening for serum lead levels between six months and six years in high-risk children; high-risk children are identified by location-specific risk recommendations, enrollment in Medicaid, being foreign born, or personal screening. 21 The USPSTF does not recommend screening for lead poisoning in children at average risk who are asymptomatic. 20

The USPSTF recommends at least one vision screening to detect amblyopia between three and five years of age. Testing options include visual acuity, ocular alignment test, stereoacuity test, photoscreening, and autorefractors. The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend screening before three years of age. 26 The AAP, American Academy of Ophthalmology, and the American Academy of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus recommend the use of an instrument-based screening (photoscreening or autorefractors) between 12 months and three years of age and annual visual acuity screening beginning at four years of age. 31

IMMUNIZATIONS

The AAFP recommends that all children be immunized. 32 Recommended vaccination schedules, endorsed by the AAP, the AAFP, and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, are found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html . Immunizations are usually administered at the two-, four-, six-, 12-, and 15- to 18-month well-child visits; the four- to six-year well-child visit; and annually during influenza season. Additional vaccinations may be necessary based on medical history. 33 Immunization history should be reviewed at each wellness visit.

Anticipatory Guidance

Injuries remain the leading cause of death among children, 34 and the AAP has made several recommendations to decrease the risk of injuries. 35 – 42 Appropriate use of child restraints minimizes morbidity and mortality associated with motor vehicle collisions. Infants need a rear-facing car safety seat until two years of age or until they reach the height or weight limit for the specific car seat. Children should then switch to a forward-facing car seat for as long as the seat allows, usually 65 to 80 lb (30 to 36 kg). 35 Children should never be unsupervised around cars, driveways, and streets. Young children should wear bicycle helmets while riding tricycles or bicycles. 37

Having functioning smoke detectors and an escape plan decreases the risk of fire- and smoke-related deaths. 36 Water heaters should be set to a maximum of 120°F (49°C) to prevent scald burns. 37 Infants and young children should be watched closely around any body of water, including water in bathtubs and toilets, to prevent drowning. Swimming pools and spas should be completely fenced with a self-closing, self-latching gate. 38

Infants should not be left alone on any high surface, and stairs should be secured by gates. 43 Infant walkers should be discouraged because they provide no benefit and they increase falls down stairs, even if stair gates are installed. 39 Window locks, screens, or limited-opening windows decrease injury and death from falling. 40 Parents or caregivers should also anchor furniture to a wall to prevent heavy pieces from toppling over. Firearms should be kept unloaded and locked. 41

Young children should be closely supervised at all times. Small objects are a choking hazard, especially for children younger than three years. Latex balloons, round objects, and food can cause life-threatening airway obstruction. 42 Long strings and cords can strangle children. 37

DENTAL CARE

Infants should never have a bottle in bed, and babies should be weaned to a cup by 12 months of age. 44 Juices should be avoided in infants younger than 12 months. 45 Fluoride use inhibits tooth demineralization and bacterial enzymes and also enhances remineralization. 11 The AAP and USPSTF recommend fluoride supplementation and the application of fluoride varnish for teeth if the water supply is insufficient. 11 , 12 Begin brushing teeth at tooth eruption with parents or caregivers supervising brushing until mastery. Children should visit a dentist regularly, and an assessment of dental health should occur at well-child visits. 44

SCREEN TIME

Hands-on exploration of their environment is essential to development in children younger than two years. Video chatting is acceptable for children younger than 18 months; otherwise digital media should be avoided. Parents and caregivers may use educational programs and applications with children 18 to 24 months of age. If screen time is used for children two to five years of age, the AAP recommends a maximum of one hour per day that occurs at least one hour before bedtime. Longer usage can cause sleep problems and increases the risk of obesity and social-emotional delays. 46

To decrease the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), the AAP recommends that infants sleep on their backs on a firm mattress for the first year of life with no blankets or other soft objects in the crib. 45 Breastfeeding, pacifier use, and room sharing without bed sharing protect against SIDS; infant exposure to tobacco, alcohol, drugs, and sleeping in bed with parents or caregivers increases the risk of SIDS. 47

DIET AND ACTIVITY

The USPSTF, AAFP, and AAP all recommend breastfeeding until at least six months of age and ideally for the first 12 months. 48 Vitamin D 400 IU supplementation for the first year of life in exclusively breastfed infants is recommended to prevent vitamin D deficiency and rickets. 49 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends the introduction of certain foods at specific ages. Early transition to solid foods before six months is associated with higher consumption of fatty and sugary foods 50 and an increased risk of atopic disease. 51 Delayed transition to cow's milk until 12 months of age decreases the incidence of iron deficiency. 52 Introduction of highly allergenic foods, such as peanut-based foods and eggs, before one year decreases the likelihood that a child will develop food allergies. 53

With approximately 17% of children being obese, many strategies for obesity prevention have been proposed. 54 The USPSTF does not have a recommendation for screening or interventions to prevent obesity in children younger than six years. 54 The AAP has made several recommendations based on expert opinion to prevent obesity. Cessation of breastfeeding before six months and introduction of solid foods before six months are associated with childhood obesity and are not recommended. 55 Drinking juice should be avoided before one year of age, and, if given to older children, only 100% fruit juice should be provided in limited quantities: 4 ounces per day from one to three years of age and 4 to 6 ounces per day from four to six years of age. Intake of other sugar-sweetened beverages should be discouraged to help prevent obesity. 45 The AAFP and AAP recommend that children participate in at least 60 minutes of active free play per day. 55 , 56

Data Sources: Literature search was performed using the USPSTF published recommendations ( https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations ) and the AAP Periodicity table ( https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/periodicity_schedule.pdf ). PubMed searches were completed using the key terms pediatric, obesity prevention, and allergy prevention with search limits of infant less than 23 months or pediatric less than 18 years. The searches included systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and position statements. Essential Evidence Plus was also reviewed. Search dates: May through October 2017.

Gauer RL, Burket J, Horowitz E. Common questions about outpatient care of premature infants. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(4):244-251.

American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital stay for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):405-409.

Baker RD, Greer FR Committee on Nutrition, American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1040-1050.

Mahle WT, Martin GR, Beekman RH, Morrow WR Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Executive Committee. Endorsement of Health and Human Services recommendation for pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):190-192.

American Academy of Pediatrics Newborn Screening Authoring Committee. Newborn screening expands: recommendations for pediatricians and medical homes—implications for the system. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):192-217.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):898-921.

Maisels MJ, Bhutani VK, Bogen D, Newman TB, Stark AR, Watchko JF. Hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant > or = 35 weeks' gestation: an update with clarifications. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1193-1198.

Christian CW Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, American Academy of Pediatrics. The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2015;136(3):583]. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1337-e1354.

Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for autism spectrum disorder in young children: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(7):691-696.

Johnson CP, Myers SM American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1183-1215.

Moyer VA. Prevention of dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1102-1111.

Clark MB, Slayton RL American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Oral Health. Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):626-633.

Siu AL. Screening for speech and language delay and disorders in children aged 5 years and younger: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e474-e481.

Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2006;118(4):1808–1809]. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):405-420.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for lipid disorders in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(6):625-633.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. October 2012. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/peds_guidelines_full.pdf . Accessed May 9, 2018.

Moyer VA. Screening for primary hypertension in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):613-619.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2017;140(6):e20173035]. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171904.

Siu AL. Screening for iron deficiency anemia in young children: USPSTF recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):746-752.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for elevated blood lead levels in children and pregnant women. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2514-2518.

Screening Young Children for Lead Poisoning: Guidance for State and Local Public Health Officials . Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Public Health Service; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Environmental Health; 1997.

O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and post-partum women: evidence report and systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(4):388-406.

Earls MF Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1032-1039.

Siu AL. Screening for depression in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(5):360-366.

Weitzman C, Wegner L American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Council on Early Childhood; Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; American Academy of Pediatrics. Promoting optimal development: screening for behavioral and emotional problems [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2015;135(5):946]. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):384-395.

Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;318(9):836-844.

Donahue SP, Nixon CN Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Visual system assessment in infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):28-30.

Lin KW. What to do at well-child visits: the AAFP's perspective. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6):362-364.

American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339.

Lavigne JV, Lebailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ. The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(3):315-328.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Visual system assessment of infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):28-30.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation. Immunizations. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/immunizations.html . Accessed October 5, 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger, United States, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html . Accessed May 9, 2018.

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2015. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_age_group_2015_1050w740h.gif . Accessed April 24, 2017.

Durbin DR American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Child passenger safety. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):788-793.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Reducing the number of deaths and injuries from residential fires. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):1355-1357.

Gardner HG American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Office-based counseling for unintentional injury prevention. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):202-206.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of drowning in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):437-439.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Injuries associated with infant walkers. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):790-792.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Falls from heights: windows, roofs, and balconies. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1188-1191.

Dowd MD, Sege RD Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee; American Academy of Pediatrics. Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1416-e1423.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):601-607.

Kendrick D, Young B, Mason-Jones AJ, et al. Home safety education and provision of safety equipment for injury prevention (review). Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8(3):761-939.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Oral Health. Maintaining and improving the oral health of young children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1224-1229.

Heyman MB, Abrams SA American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. Fruit juice in infants, children, and adolescents: current recommendations. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20170967.

Council on Communications and Media. Media and young minds. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162591.

Moon RY Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162940.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841.

Wagner CL, Greer FR American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding; Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2009;123(1):197]. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1142-1152.

Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e544-e551.

Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition; Section on Allergy and Immunology. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183-191.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. The use of whole cow's milk in infancy. Pediatrics. 1992;89(6 pt 1):1105-1109.

Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Assa'ad AH, Pongracic JA. Primary prevention of allergic disease through nutritional interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(1):29-36.

Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2417-2426.

Daniels SR, Hassink SG Committee on Nutrition. The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e275-e292.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Physical activity in children. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/physical-activity.html . Accessed January 1, 2018.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Family Life

How your pediatrician is paid: coding information for parents.

By: Suzanne Berman, MD, FAAP & Angelo Peter Giardino, MD, PhD, FAAP

Many families have benefit plans that help cover the cost of healthcare services for their children. These can be through an employer, a health insurance plan, or a government program (such as Medicare or Medicaid), for example.

Understanding how your plan processes and pays for different pediatric services can help you plan for what your family's out-of-pocket costs may be.

It starts with coding…

The process begins with your pediatrician reporting to the payer what services were provided and why.

Diagnostic codes are reported by your pediatrician to indicate why your child was seen or treated. The codes used to describe the reason for the visit are called the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) . There are literally thousands of ICD codes in use for pediatric and adult medicine.

Procedural codes tell what services were provided. Each medical service has its own code. All are included in the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) , which is produced by the American Medical Association (AMA) for standardized use by insurance companies, government payers, and medical professionals when reporting services for payment. The procedural codes also help insurance companies keep track of the number of specific procedures done annually, for example.

Why coding can be tricky:

New codes are created, old codes are removed, and definitions of existing codes can change. For example, there at least a dozen different CPT codes for flu vaccines alone, depending on the patient's age, vaccine dose, and type of influenza vaccine.

To help keep everyone up to speed, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has an entire division devoted to pediatric coding. The AAP Committee on Coding and Nomenclature works with the AMA to ensure codes are adequately reflecting necessary pediatric services. In addition, the AAP educates pediatricians and pediatric specialists about proper coding and urges payers to update their systems to reflect current pediatric codes.

Lumping, splitting, bundling & unbundling:

Coding can be very confusing, because sometimes one CPT code is used to represent several services. Other times, multiple codes are required to represent just one service. Think of it in terms of how restaurants charge for meals. Some restaurants have a separate charge for each item ordered (a la carte). Other, buffet-style restaurants may charge a flat fee per person―regardless of how much you eat.

Some CPT codes represent an all-inclusive fee for a period.

A "buffet-style" code (a "global code") represents all work done for a set period. For example, CPT code 59409 represents the global service of prenatal care and vaginal delivery. The same code is used whether the mother attended all prenatal visits on time, was a high-risk pregnancy requiring extra visits, or received no prenatal care until the third trimester.

Most pediatric office visits follow the "a la carte" model.

In an "a la carte" model , each service is reported with a separate code. A well-child checkup for a nine-month-old baby who is new to the practice involves history taking, an examination, and appropriate counseling. This would be coded simply as 99381. However, if your pediatrician follows AAP recommendations for well-child visits , he or she might report several line items for that visit:

99382 –Well-child checkup

96110 – Brief developmental screening with scoring

36416 – Fingerstick blood draw

85018 – Hemoglobin blood count

Even giving a single vaccine involves 2-3 different CPT codes:

The serum code represents the cost of the vaccine itself, as well as the cost of ordering and storing the vaccine. Each vaccine has a separate serum code. For example, the serum code for the MMR vaccine is 90707.

The administration code(s) represent the work of vaccination: determining which vaccine(s) is/are due, counseling the patient, drawing it up in a syringe, administering the vaccine, completing the medical record the patient's vaccine record. Depending on whether the provider counseled on vaccines and the type of vaccine given, one or two administration codes might be used just for a single shot.

Why not "bundle" all the recommended services into a single code for simplicity?

The answer is complicated. While your pediatrician selects the code(s) used to report the visit, he or she does not set the definitions of each code, nor does he or she determine how your insurance processes each code. If pediatricians and payers disagree about the right codes to report a service, a patient can feel caught in the middle.

While most pediatricians try hard to code correctly and minimize out-of-pocket costs to families, it is impossible for pediatric practices to always know how each patient's insurance will process claims. For example, a busy pediatric practice might use over 100 codes and work with at least 50 different health plans―who all have different rules for payment. Some practices have policies around this to prevent misunderstandings; ask your pediatrician's office.

Processing the claim:

After the coding is completed by your pediatrician's office, a bill (claim) is sent to the payer(s). For families with health insurance, the claim would be sent to the insurance plan. The insurance plan will review the claim (called claims processing) and assess it based on your specific benefits' coverage.

If the claim is for a covered service: The plan will process for payment based on its agreement with your pediatrician.

If there are non-covered services included in the claim: The third-party payer will deny payment and the patient or family will be responsible for payment for the non-covered service(s).

You may receive an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) from your health plan that outlines what was or was not paid. If your plan has a deductible, co-payment, or co-insurance , you will be responsible for paying the provider your share of the claim.

Remember:

Healthcare payment processing can be a complicated process, and one that can change year to year based on benefits. If you have questions, don't hesitate to talk with your pediatrician's office and benefits provider.

About Dr. Berman:

About Dr. Giardino:

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

- LinkedIn Icon

When to use normal care, sick care codes for newborns in hospital

Newborns are the only patients who are admitted to a hospital and may never develop a medical issue or problem and may transition to life in a routine and healthy way.

Coding for newborn services is complex. A newborn will fall under one of four clinical indicators for procedural coding: normal, sick, intensive or critical.

This article focuses only on the nuances between normal care and sick care for babies born in the hospital whose discharge date is subsequent to their initial service date. Intensive care and critical care services are not addressed.

Normal newborn care services

Per the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) manual, Evaluation and Management (E/M) services for the (normal) newborn include maternal and/or fetal and newborn history, newborn physical examination(s), ordering of diagnostic tests and treatments, meetings with the family, and documentation in the medical record.

Normal newborn care services are reported with these codes:

99460 Initial hospital or birthing center care, per day, for E/M of normal newborn infant

99462 Subsequent hospital care, per day, for E/M of normal newborn

The Coding for Pediatrics manual defines a normal newborn as the following:

- Transitions to life in the usual manner.

- May require delivery room intervention but is normal after transition.

- May require some testing or follow-up assessment (e.g., bilirubin, complete blood cell count, culture).

- Does not require significant intervention.

- May be observed for illness but currently does not exhibit any signs or symptoms of the disease.

- May be late preterm but requires no special care.

- May be in house with sick mother/twin.

It is important to note that some babies may have an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification abnormal diagnosis or an observation diagnosis reported but still may qualify for normal newborn care.

A baby born at 38 6/7 weeks’ gestation has ABO incompatibility. The physician is following serial bilirubin levels, but the baby is not on phototherapy. The patient transitions well and no further intervention is required as bilirubin levels remain within normal limits. The baby is coded as a normal newborn.

A baby was born at 39 weeks to a mother with a positive prenatal history of narcotic use. The baby is diagnosed with in-utero narcotic exposure but remains asymptomatic. The patient is being followed for any adverse symptoms but is rooming with mom. The baby is coded as a normal newborn.

Sick newborn care services

Some babies have clinical indications that require more work and medical decision-making than is required for a normal newborn but do not require intensive care. Their care is reported with the following sick newborn hospital care codes:

99221-99223 * Initial hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient

99231-99233 * Subsequent hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient

*Reported based on meeting or exceeding the required key elements or based on time per the CPT code descriptors.

A baby was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to a mother who is positive for syphilis. The baby is asymptomatic but is at risk for developing congenital syphilis. The baby has been placed on daily penicillin dosing and remains with the mother in the well-baby setting. The baby’s care is coded with a daily hospital care code.

A baby was born at 39 4/7 weeks’ gestation to a mother who developed gestational diabetes. At 12 hours of age, a blood sugar test reveals hypoglycemia. The physician orders oral glucose and discusses extra feedings with the nursing staff and mom. The sugar levels are ordered to be taken more frequently. After a couple more feedings, the blood sugar levels normalize. This would be coded with a daily hospital care code.

It is important to recognize that newborns may have transitory issues that require observation but will resolve without intervention. Those conditions can present in a normal newborn. Babies who require hospital care services will require additional medical decision-making and are more at risk for morbidity.

The vignettes above are meant to be vague. Co-morbidities or other circumstances can change how a newborn needs to be treated and managed. Always code based on documentation and what is medically necessary for the baby.

Vitaliya M. Boyar, M.D., FAAP, David M. Kanter, M.D., M.B.A., FAAP, and Edward A. Liechty, M.D., FAAP, contributed to this article.

- Newborn Coding Decision Tool 2021

- Coding for Pediatrics 2021

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

- Additional Coding Corner columns

Advertising Disclaimer »

Email alerts

1. AAP leaders call decision to pull harmful weighted sleep products a 'strong first step'

2. Health Alerts: Liquid vitamins, sleepwear, hydrogen peroxide, magnetic ball sets and more recalled

3. Study: Adolescent school shooters often use guns stolen from family

May issue digital edition

Subscribe to AAP News

Column collections

Topic collections

Affiliations

Advertising.

- Submit a story

- American Academy of Pediatrics

- Online ISSN 1556-3332

- Print ISSN 1073-0397

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

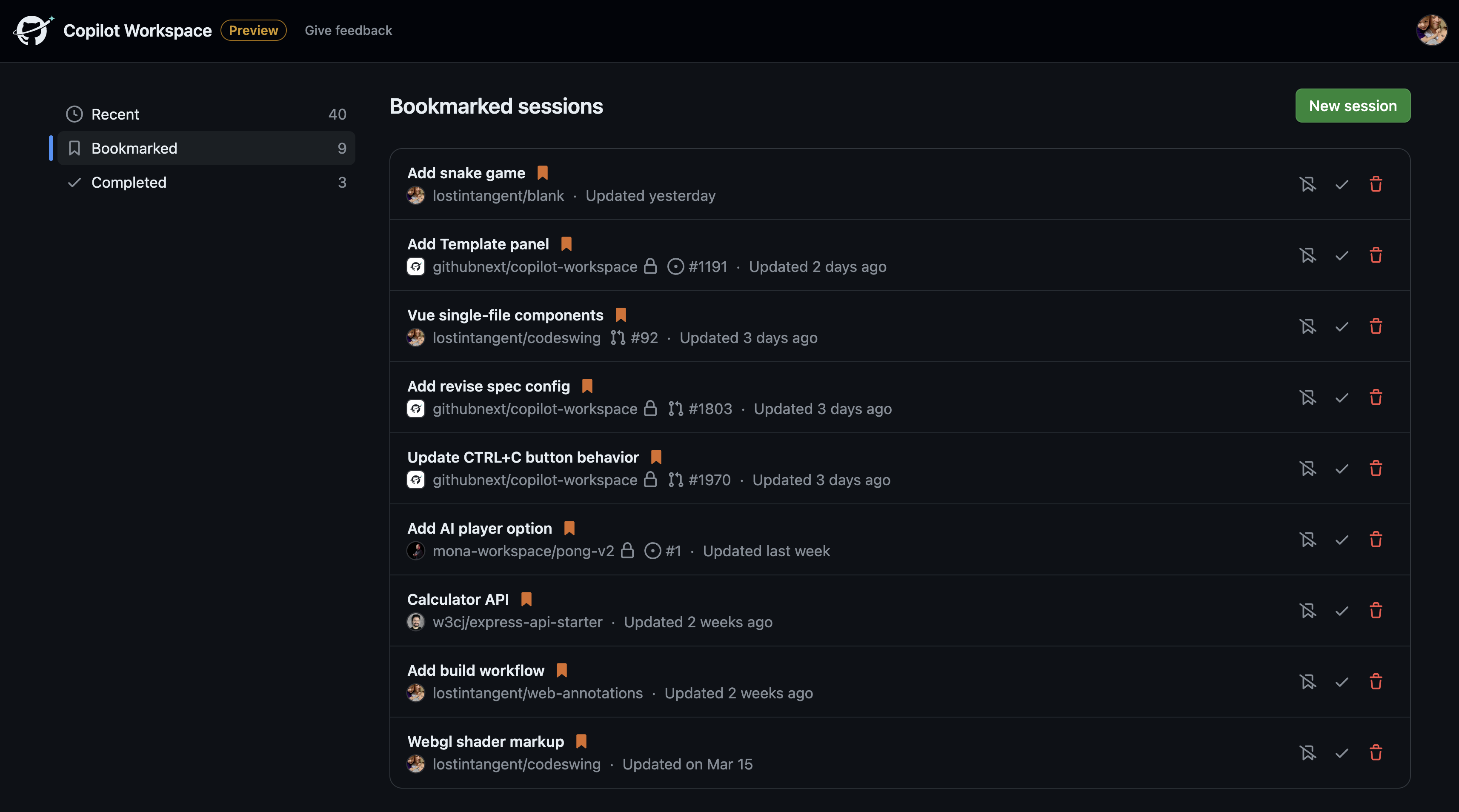

Copilot Workspace is GitHub’s take on AI-powered software engineering

Is the future of software development an AI-powered IDE? GitHub’s floating the idea.

Ahead of its annual GitHub Universe conference in San Francisco early this fall, GitHub announced Copilot Workspace, a dev environment that taps what GitHub describes as “Copilot-powered agents” to help developers brainstorm, plan, build, test and run code in natural language.

Jonathan Carter, head of GitHub Next, GitHub’s software R&D team, pitches Workspace as somewhat of an evolution of GitHub’s AI-powered coding assistant Copilot into a more general tool, building on recently introduced capabilities like Copilot Chat , which lets developers ask questions about code in natural language.

“Through research, we found that, for many tasks, the biggest point of friction for developers was in getting started, and in particular knowing how to approach a [coding] problem, knowing which files to edit and knowing how to consider multiple solutions and their trade-offs,” Carter said. “So we wanted to build an AI assistant that could meet developers at the inception of an idea or task, reduce the activation energy needed to begin and then collaborate with them on making the necessary edits across the entire corebase.”

At last count, Copilot had over 1.8 million paying individual and 50,000 enterprise customers. But Carter envisions a far larger base, drawn in by feature expansions with broad appeal, like Workspace.

“Since developers spend a lot of their time working on [coding issues], we believe we can help empower developers every day through a ‘thought partnership’ with AI,” Carter said. “You can think of Copilot Workspace as a companion experience and dev environment that complements existing tools and workflows and enables simplifying a class of developer tasks … We believe there’s a lot of value that can be delivered in an AI-native developer environment that isn’t constrained by existing workflows.”

There’s certainly internal pressure to make Copilot profitable.

Copilot loses an average of $20 a month per user , according to a Wall Street Journal report, with some customers costing GitHub as much as $80 a month. And the number of rival services continues to grow. There’s Amazon’s CodeWhisperer , which the company made free to individual developers late last year. There are also startups, like Magic , Tabnine , Codegen and Laredo .

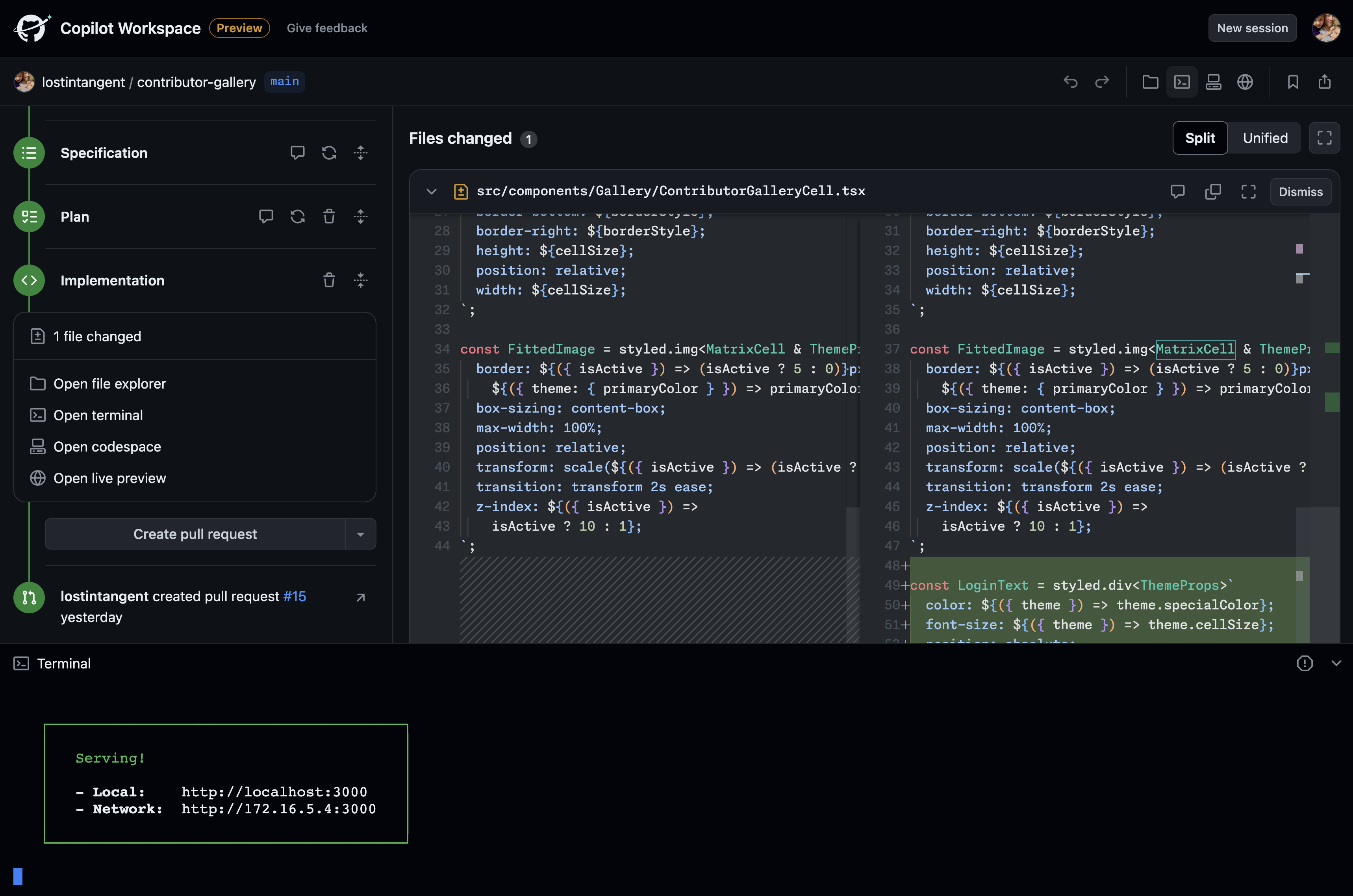

Given a GitHub repo or a specific bug within a repo, Workspace — underpinned by OpenAI’s GPT-4 Turbo model — can build a plan to (attempt to) squash the bug or implement a new feature, drawing on an understanding of the repo’s comments, issue replies and larger codebase. Developers get suggested code for the bug fix or new feature, along with a list of the things they need to validate and test that code, plus controls to edit, save, refactor or undo it.

Image Credits: GitHub

The suggested code can be run directly in Workspace and shared among team members via an external link. Those team members, once in Workspace, can refine and tinker with the code as they see fit.

Perhaps the most obvious way to launch Workspace is from the new “Open in Workspace” button to the left of issues and pull requests in GitHub repos. Clicking on it opens a field to describe the software engineering task to be completed in natural language, like, “Add documentation for the changes in this pull request,” which, once submitted, gets added to a list of “sessions” within the new dedicated Workspace view.

Workspace executes requests systematically step by step, creating a specification, generating a plan and then implementing that plan. Developers can dive into any of these steps to get a granular view of the suggested code and changes and delete, re-run or re-order the steps as necessary.

“If you ask any developer where they tend to get stuck with a new project, you’ll often hear them say it’s knowing where to start,” Carter said. “Copilot Workspace lifts that burden and gives developers a plan to start iterating from.”

Workspace enters technical preview on Monday, optimized for a range of devices, including mobile.

Importantly, because it’s in preview, Workspace isn’t covered by GitHub’s IP indemnification policy, which promises to assist with the legal fees of customers facing third-party claims alleging that the AI-generated code they’re using infringes on IP. (Generative AI models notoriously regurgitate their training datasets, and GPT-4 Turbo was trained partly on copyrighted code.)

GitHub says that it hasn’t determined how it’s going to productize Workspace, but that it’ll use the preview to “learn more about the value it delivers and how developers use it.”

I think the more important question is: Will Workspace fix the existential issues surrounding Copilot and other AI-powered coding tools?

An analysis of over 150 million lines of code committed to project repos over the past several years by GitClear, the developer of the code analysis tool of the same name, found that Copilot was resulting in more mistaken code being pushed to codebases and more code being re-added as opposed to reused and streamlined, creating headaches for code maintainers.

Elsewhere, security researchers have warned that Copilot and similar tools can amplify existing bugs and security issues in software projects . And Stanford researchers have found that developers who accept suggestions from AI-powered coding assistants tend to produce less secure code . (GitHub stressed to me that it uses an AI-based vulnerability prevention system to try to block insecure code in addition to an optional code duplication filter to detect regurgitations of public code.)

Yet devs aren’t shying away from AI.

In a StackOverflow poll from June 2023, 44% of developers said that they use AI tools in their development process now, and 26% plan to soon. Gartner predicts that 75% of enterprise software engineers will employ AI code assistants by 2028.

By emphasizing human review, perhaps Workspace can indeed help clean up some of the mess introduced by AI-generated code. We’ll find out soon enough as Workspace makes its way into developers’ hands.

“Our primary goal with Copilot Workspace is to leverage AI to reduce complexity so developers can express their creativity and explore more freely,” Carter said. “We truly believe the combination of human plus AI is always going to be superior to one or the other alone, and that’s what we’re betting on with Copilot Workspace.”

The May 2024 issue of IEEE Spectrum is here!

For IEEE Members

Ieee spectrum, follow ieee spectrum, support ieee spectrum, enjoy more free content and benefits by creating an account, saving articles to read later requires an ieee spectrum account, the institute content is only available for members, downloading full pdf issues is exclusive for ieee members, downloading this e-book is exclusive for ieee members, access to spectrum 's digital edition is exclusive for ieee members, following topics is a feature exclusive for ieee members, adding your response to an article requires an ieee spectrum account, create an account to access more content and features on ieee spectrum , including the ability to save articles to read later, download spectrum collections, and participate in conversations with readers and editors. for more exclusive content and features, consider joining ieee ., join the world’s largest professional organization devoted to engineering and applied sciences and get access to all of spectrum’s articles, archives, pdf downloads, and other benefits. learn more →, join the world’s largest professional organization devoted to engineering and applied sciences and get access to this e-book plus all of ieee spectrum’s articles, archives, pdf downloads, and other benefits. learn more →, access thousands of articles — completely free, create an account and get exclusive content and features: save articles, download collections, and talk to tech insiders — all free for full access and benefits, join ieee as a paying member., ai copilots are changing how coding is taught, professors are shifting away from syntax and emphasizing higher-level skills.

Generative AI is transforming the software development industry. AI-powered coding tools are assisting programmers in their workflows, while jobs in AI continue to increase. But the shift is also evident in academia—one of the major avenues through which the next generation of software engineers learn how to code.

Computer science students are embracing the technology, using generative AI to help them understand complex concepts, summarize complicated research papers, brainstorm ways to solve a problem, come up with new research directions, and, of course, learn how to code.

“Students are early adopters and have been actively testing these tools,” says Johnny Chang , a teaching assistant at Stanford University pursuing a master’s degree in computer science. He also founded the AI x Education conference in 2023, a virtual gathering of students and educators to discuss the impact of AI on education.

So as not to be left behind, educators are also experimenting with generative AI. But they’re grappling with techniques to adopt the technology while still ensuring students learn the foundations of computer science.

“It’s a difficult balancing act,” says Ooi Wei Tsang , an associate professor in the School of Computing at the National University of Singapore . “Given that large language models are evolving rapidly, we are still learning how to do this.”

Less Emphasis on Syntax, More on Problem Solving

The fundamentals and skills themselves are evolving. Most introductory computer science courses focus on code syntax and getting programs to run, and while knowing how to read and write code is still essential, testing and debugging—which aren’t commonly part of the syllabus—now need to be taught more explicitly.

“We’re seeing a little upping of that skill, where students are getting code snippets from generative AI that they need to test for correctness,” says Jeanna Matthews , a professor of computer science at Clarkson University in Potsdam, N.Y.

Another vital expertise is problem decomposition. “This is a skill to know early on because you need to break a large problem into smaller pieces that an LLM can solve,” says Leo Porter , an associate teaching professor of computer science at the University of California, San Diego . “It’s hard to find where in the curriculum that’s taught—maybe in an algorithms or software engineering class, but those are advanced classes. Now, it becomes a priority in introductory classes.”

“Given that large language models are evolving rapidly, we are still learning how to do this.” —Ooi Wei Tsang, National University of Singapore

As a result, educators are modifying their teaching strategies. “I used to have this singular focus on students writing code that they submit, and then I run test cases on the code to determine what their grade is,” says Daniel Zingaro , an associate professor of computer science at the University of Toronto Mississauga . “This is such a narrow view of what it means to be a software engineer, and I just felt that with generative AI, I’ve managed to overcome that restrictive view.”

Zingaro, who coauthored a book on AI-assisted Python programming with Porter, now has his students work in groups and submit a video explaining how their code works. Through these walk-throughs, he gets a sense of how students use AI to generate code, what they struggle with, and how they approach design, testing, and teamwork.

“It’s an opportunity for me to assess their learning process of the whole software development [life cycle]—not just code,” Zingaro says. “And I feel like my courses have opened up more and they’re much broader than they used to be. I can make students work on larger and more advanced projects.”

Ooi echoes that sentiment, noting that generative AI tools “will free up time for us to teach higher-level thinking—for example, how to design software, what is the right problem to solve, and what are the solutions. Students can spend more time on optimization, ethical issues, and the user-friendliness of a system rather than focusing on the syntax of the code.”

Avoiding AI’s Coding Pitfalls

But educators are cautious given an LLM’s tendency to hallucinate . “We need to be teaching students to be skeptical of the results and take ownership of verifying and validating them,” says Matthews.

Matthews adds that generative AI “can short-circuit the learning process of students relying on it too much.” Chang agrees that this overreliance can be a pitfall and advises his fellow students to explore possible solutions to problems by themselves so they don’t lose out on that critical thinking or effective learning process. “We should be making AI a copilot—not the autopilot—for learning,” he says.

“We should be making AI a copilot—not the autopilot—for learning.” —Johnny Chang, Stanford University

Other drawbacks include copyright and bias. “I teach my students about the ethical constraints—that this is a model built off other people’s code and we’d recognize the ownership of that,” Porter says. “We also have to recognize that models are going to represent the bias that’s already in society.”

Adapting to the rise of generative AI involves students and educators working together and learning from each other. For her colleagues, Matthews’s advice is to “try to foster an environment where you encourage students to tell you when and how they’re using these tools. Ultimately, we are preparing our students for the real world, and the real world is shifting, so sticking with what you’ve always done may not be the recipe that best serves students in this transition.”

Porter is optimistic that the changes they’re applying now will serve students well in the future. “There’s this long history of a gap between what we teach in academia and what’s actually needed as skills when students arrive in the industry,” he says. “There’s hope on my part that we might help close the gap if we embrace LLMs.”

- How Coders Can Survive—and Thrive—in a ChatGPT World ›

- AI Coding Is Going From Copilot to Autopilot ›

- OpenAI Codex ›

Rina Diane Caballar is a writer covering tech and its intersections with science, society, and the environment. An IEEE Spectrum Contributing Editor, she's a former software engineer based in Wellington, New Zealand.

"Video Games" for Flies Shed Light on How They Fly

Ieee’s honor society expands to more countries, video friday: loco-manipulation, related stories, ai spam threatens the internet—ai can also protect it, what is generative ai, generative ai has a visual plagiarism problem.

Help | Advanced Search

Electrical Engineering and Systems Science > Image and Video Processing

Title: joint reference frame synthesis and post filter enhancement for versatile video coding.

Abstract: This paper presents the joint reference frame synthesis (RFS) and post-processing filter enhancement (PFE) for Versatile Video Coding (VVC), aiming to explore the combination of different neural network-based video coding (NNVC) tools to better utilize the hierarchical bi-directional coding structure of VVC. Both RFS and PFE utilize the Space-Time Enhancement Network (STENet), which receives two input frames with artifacts and produces two enhanced frames with suppressed artifacts, along with an intermediate synthesized frame. STENet comprises two pipelines, the synthesis pipeline and the enhancement pipeline, tailored for different purposes. During RFS, two reconstructed frames are sent into STENet's synthesis pipeline to synthesize a virtual reference frame, similar to the current to-be-coded frame. The synthesized frame serves as an additional reference frame inserted into the reference picture list (RPL). During PFE, two reconstructed frames are fed into STENet's enhancement pipeline to alleviate their artifacts and distortions, resulting in enhanced frames with reduced artifacts and distortions. To reduce inference complexity, we propose joint inference of RFS and PFE (JISE), achieved through a single execution of STENet. Integrated into the VVC reference software VTM-15.0, RFS, PFE, and JISE are coordinated within a novel Space-Time Enhancement Window (STEW) under Random Access (RA) configuration. The proposed method could achieve -7.34%/-17.21%/-16.65% PSNR-based BD-rate on average for three components under RA configuration.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- HTML (experimental)

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

sick visit (99202-99215). . Codes . 99406-99409. may be reported in addition to the preventive. medicine service codes. CPT. Codes. 99406. moking and tobacco use cessation counseling visit; S ntermediate, greater than 3 minutes up to 10 minutesi. 99407. ntensive, greater than 10 minutesi. 99408. lcohol or substance (other than tobacco ...

the bab the ne tthe baby the next morning. - He reviews the records. ... - Code 99232 subsequent inpatient visit for day 3 - 99238/99239 for discharge day 4 dependent on time99238/99239 for discharge day 4, dependent on time ... • Includes CPT® and ICD-9-CM codes for 43 Vaccines and

AAP recommends use preventive medicine codes 99381-99397. If not covered due to previous preventive visit in same year, will be billed to parent. Office visit codes 99211-99215 only if problem uncovered. 99241-99245 outpt. consult if coach or school nurse requests visit due to medical concern.

A child has a well-child visit EPSDT (99381 - 99461), with a well child diagnosis code (Z-code) in the first position; the sick visit code (99211 - 99215) with the modifier 25 and with the illness diagnosis CPT code in the second position. To bill this way, there mustbe enough evidence in the medical record documentation to support a stand ...

CODES FOR THE INITIAL CARE OF THE NORMAL NEWBORN. 99460. Initial hospital or birthing center care, per day, for E/M of normal newborn infant. 99461. Initial care per day, for E/M of normal newborn ...

To bill for a well-child visit: Use the age-based preventive visit CPT code and appropriate ICD-10 Code listed in Table 1. Bill for each separate assessment/screening performed using the applicable CPT code from Table 2. If a screening or assessment is positive, use ICD-10 code Z00.121. If it is an issue that requires follow-up or a referral ...

Immunizations are usually administered at the two-, four-, six-, 12-, and 15- to 18-month well-child visits; the four- to six-year well-child visit; and annually during influenza season ...

Because 99431 and 99433 are per-day codes, you may bill them once per day only, regardless of how often the doctor sees the infant. Office setting: When the pediatrician sees the baby for the first time and the visit occurs in the office, use an office visit code (99201-99205) or preventive medicine services code (CPT 99381 ). If she has been ...

AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter (2016) 11 (12): 1-4. Current Procedural Terminology ( CPT ®) provides specific codes for normal and intensive or critical care of the newborn. In between these levels of care, physicians may report initial or subsequent hospital care for a newborn who is ill but who does not require intensive or critical care.

Coding for services provided after discharge from the birth admission often fall into the preventive evaluation and management (E/M) service categories (eg, 99391).However, coding may become more complicated when a well-baby visit includes abnormal findings or a visit is scheduled due to illness or concerns about the neonate's health.

Well-Child Visits in the First 30 Months of Life (W30) Measure Description Children who had the following number of well-child visits with a PCP during the following timeframes: • Well-Child Visits in the First 15 Months Children who had six or more well-child visits on different dates of service on or before the 15-month birthday

Examples of commonly used CPT codes: 99381 - Well baby checkup (new patient) 12001 - Repairing a small laceration on the leg. 76856 - Complete ultrasound of pelvis. ... While your pediatrician selects the code(s) used to report the visit, he or she does not set the definitions of each code, nor does he or she determine how your insurance ...

The baby is asymptomatic but is at risk for developing congenital syphilis. The baby has been placed on daily penicillin dosing and remains with the mother in the well-baby setting. The baby's care is coded with a daily hospital care code. A baby was born at 39 4/7 weeks' gestation to a mother who developed gestational diabetes.

Code 99432 is the only code you can use when a baby was born in a home, then brought to your office for the first exam. This is a fairly frequent occurrence at Baylor Pediatric Center, a three-physician, one-nurse practitioner practice in Dallas, TX. Her pediatricians use 99432 when a mother delivers at home or at a birthing center, says ...

The preventive medicineservices codes for new patients are 99381 (under 1 year old), 99382 (1 through 4), 99383 (5 through 11), 99384 (12 through 17), and 99385 (18 through 39). The office-visit codes are 99201 through 99205. Note that the sick diagnosis code goes only on the office visit, and the well-care diagnosis code, V20.2, goes only on ...

Hep B CPT: 90697, 90723, 90740, 90744, 90747-8 Hep B HCPCS: G0010 VZV CPT: 90710, 90716 PCV CPT: 90670 PCV HCPCS: G0009 Hep A CPT: 90633 RV Rotarix (2 Dose Schedule) CPT: 90681 RV RotaTeq (3 Dose Schedule) CPT: 90680 Influenza CPT: 90655, 90657, 90661, 90673-4, 90685-90689, 90756 Influenza HCPCS: G0008 Influenza LAIV CPT: 90660, 90672 (on 2nd ...

The current mechanisms to bill for obstetric care include billing each office visit as an appropriate Evaluation & Management (E/M) service and billing the delivery CPT codes (59409, 59514, 59612, 59620), or utilizing the global maternity codes. After the initial postpartum period (no later than 12 weeks after birth) care should not be covered ...

Use CPT Category II code 0500F (Initial prenatal care visit) or 0501F (Prenatal flow sheet documented in medical record by first prenatal visit). Date of postpartum visit - The postpartum visit should occur 4-6 weeks after delivery. Use CPT II code 0503F (postpartum care visit) and ICD-10 diagnosis code Z39.2 (routine postpartum follow-up).

CPT® Code: Description: 99381: Initial comprehensive preventive medicine evaluation and management, new patient; infant (age younger than 1 year): 99382 early childhood (age 1 through 4 years) 99383 late childhood (age 5 through 11 years) 99384 adolescent (age 12 through 17 years) 99385 18-39 years 99386 40-64 years 99387 65 years and older

Options for coding and billing as a follow-up visit: Schedule follow-up visit with physician or billable licensed health care provider (eg, NP or PA): Use codes 99212-99215 and appropriate ICD-10-CM codes: If the feeding problem persists, use an ICD-10-CM such as P92.2, P92.3, P92.5, P92.8, etc. If the feeding problem has resolved, use ICD-10 ...

Copilot loses an average of $20 a month per user, according to a Wall Street Journal report, with some customers costing GitHub as much as $80 a month. And the number of rival services continues ...

When the pediatrician provides E/M services for newborns who are not considered "normal," CPT ® directs you to report the codes for hospital inpatient (99221-99233), neonatal intensive (99477-99480), or critical care (99468-99469) services. A baby considered a "sick" newborn might have a fever, high hemoglobin count, or mild respiratory distress.

Professors are shifting away from syntax and emphasizing higher-level skills. Generative AI is transforming the software development industry. AI-powered coding tools are assisting programmers in ...

This paper presents the joint reference frame synthesis (RFS) and post-processing filter enhancement (PFE) for Versatile Video Coding (VVC), aiming to explore the combination of different neural network-based video coding (NNVC) tools to better utilize the hierarchical bi-directional coding structure of VVC. Both RFS and PFE utilize the Space-Time Enhancement Network (STENet), which receives ...

After the eighth visit, the patient changes insurance carriers. The eight visits prior to the insurance change are separately reportable to the initial payer. To code this scenario correctly, the physician reports 59426 (one unit). If only one to three antepartum visits were provided, report the appropriate E/M codes, according to CPT® guidelines.