UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Ethics, Culture and Social Responsibility

- Global Code of Ethics for Tourism

- Accessible Tourism

Tourism and Culture

- Women’s Empowerment and Tourism

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

The convergence between tourism and culture, and the increasing interest of visitors in cultural experiences, bring unique opportunities but also complex challenges for the tourism sector.

“Tourism policies and activities should be conducted with respect for the artistic, archaeological and cultural heritage, which they should protect and pass on to future generations; particular care should be devoted to preserving monuments, worship sites, archaeological and historic sites as well as upgrading museums which must be widely open and accessible to tourism visits”

UN Tourism Framework Convention on Tourism Ethics

Article 7, paragraph 2

This webpage provides UN Tourism resources aimed at strengthening the dialogue between tourism and culture and an informed decision-making in the sphere of cultural tourism. It also promotes the exchange of good practices showcasing inclusive management systems and innovative cultural tourism experiences .

About Cultural Tourism

According to the definition adopted by the UN Tourism General Assembly, at its 22nd session (2017), Cultural Tourism implies “A type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination. These attractions/products relate to a set of distinctive material, intellectual, spiritual and emotional features of a society that encompasses arts and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries and the living cultures with their lifestyles, value systems, beliefs and traditions”. UN Tourism provides support to its members in strengthening cultural tourism policy frameworks, strategies and product development . It also provides guidelines for the tourism sector in adopting policies and governance models that benefit all stakeholders, while promoting and preserving cultural elements.

Recommendations for Cultural Tourism Key Players on Accessibility

UN Tourism , Fundación ONCE and UNE issued in September 2023, a set of guidelines targeting key players of the cultural tourism ecosystem, who wish to make their offerings more accessible.

The key partners in the drafting and expert review process were the ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Committee and the European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT) . The ICOMOS experts’ input was key in covering crucial action areas where accessibility needs to be put in the spotlight, in order to make cultural experiences more inclusive for all people.

This guidance tool is also framed within the promotion of the ISO Standard ISO 21902 , in whose development UN Tourism had one of the leading roles.

Download here the English and Spanish version of the Recommendations.

Compendium of Good Practices in Indigenous Tourism

The report is primarily meant to showcase good practices championed by indigenous leaders and associations from the Region. However, it also includes a conceptual introduction to different aspects of planning, management and promotion of a responsible and sustainable indigenous tourism development.

The compendium also sets forward a series of recommendations targeting public administrations, as well as a list of tips promoting a responsible conduct of tourists who decide to visit indigenous communities.

For downloads, please visit the UN Tourism E-library page: Download in English - Download in Spanish .

Weaving the Recovery - Indigenous Women in Tourism

This initiative, which gathers UN Tourism , t he World Indigenous Tourism Alliance (WINTA) , Centro de las Artes Indígenas (CAI) and the NGO IMPACTO , was selected as one of the ten most promising projects amoung 850+ initiatives to address the most pressing global challenges. The project will test different methodologies in pilot communities, starting with Mexico , to enable indigenous women access markets and demonstrate their leadership in the post-COVID recovery.

This empowerment model , based on promoting a responsible tourism development, cultural transmission and fair-trade principles, will represent a novel community approach with a high global replication potential.

Visit the Weaving the Recovery - Indigenous Women in Tourism project webpage.

Inclusive Recovery of Cultural Tourism

The release of the guidelines comes within the context of the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development 2021 , a UN initiative designed to recognize how culture and creativity, including cultural tourism, can contribute to advancing the SDGs.

UN Tourism Inclusive Recovery Guide, Issue 4: Indigenous Communities

Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism

The Recommendations on Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism provide guidance to tourism stakeholders to develop their operations in a responsible and sustainable manner within those indigenous communities that wish to:

- Open up to tourism development, or

- Improve the management of the existing tourism experiences within their communities.

They were prepared by the UN Tourism Ethics, Culture and Social Responsibility Department in close consultation with indigenous tourism associations, indigenous entrepreneurs and advocates. The Recommendations were endorsed by the World Committee on Tourism Ethics and finally adopted by the UN Tourism General Assembly in 2019, as a landmark document of the Organization in this sphere.

Who are these Recommendations targeting?

- Tour operators and travel agencies

- Tour guides

- Indigenous communities

- Other stakeholders such as governments, policy makers and destinations

The Recommendations address some of the key questions regarding indigenous tourism:

Download PDF:

- Recommendations on Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism

- Recomendaciones sobre el desarrollo sostenible del turismo indígena, ESP

UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conferences on Tourism and Culture

The UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conferences on Tourism and Culture bring together Ministers of Tourism and Ministers of Culture with the objective to identify key opportunities and challenges for a stronger cooperation between these highly interlinked fields. Gathering tourism and culture stakeholders from all world regions the conferences which have been hosted by Cambodia, Oman, Türkiye and Japan have addressed a wide range of topics, including governance models, the promotion, protection and safeguarding of culture, innovation, the role of creative industries and urban regeneration as a vehicle for sustainable development in destinations worldwide.

Fourth UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference on Tourism and Culture: Investing in future generations. Kyoto, Japan. 12-13 December 2019 Kyoto Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Investing in future generations ( English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Russian and Japanese )

Third UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference on Tourism and Culture : For the Benefit of All. Istanbul, Türkiye. 3 -5 December 2018 Istanbul Declaration on Tourism and Culture: For the Benefit of All ( English , French , Spanish , Arabic , Russian )

Second UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference’s on Tourism and Culture: Fostering Sustainable Development. Muscat, Sultanate of Oman. 11-12 December 2017 Muscat Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Fostering Sustainable Development ( English , French , Spanish , Arabic , Russian )

First UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference’s on Tourism and Culture: Building a new partnership. Siem Reap, Cambodia. 4-6 February 2015 Siem Reap Declaration on Tourism and Culture – Building a New Partnership Model ( English )

UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage

The first UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage provides comprehensive baseline research on the interlinkages between tourism and the expressions and skills that make up humanity’s intangible cultural heritage (ICH).

Through a compendium of case studies drawn from across five continents, the report offers in-depth information on, and analysis of, government-led actions, public-private partnerships and community initiatives.

These practical examples feature tourism development projects related to six pivotal areas of ICH: handicrafts and the visual arts; gastronomy; social practices, rituals and festive events; music and the performing arts; oral traditions and expressions; and, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe.

Highlighting innovative forms of policy-making, the UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage recommends specific actions for stakeholders to foster the sustainable and responsible development of tourism by incorporating and safeguarding intangible cultural assets.

UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage

- UN Tourism Study

- Summary of the Study

Studies and research on tourism and culture commissioned by UN Tourism

- Tourism and Culture Synergies, 2018

- UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2012

- Big Data in Cultural Tourism – Building Sustainability and Enhancing Competitiveness (e-unwto.org)

Outcomes from the UN Tourism Affiliate Members World Expert Meeting on Cultural Tourism, Madrid, Spain, 1–2 December 2022

UN Tourism and the Region of Madrid – through the Regional Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Sports – held the World Expert Meeting on Cultural Tourism in Madrid on 1 and 2 December 2022. The initiative reflects the alliance and common commitment of the two partners to further explore the bond between tourism and culture. This publication is the result of the collaboration and discussion between the experts at the meeting, and subsequent contributions.

Relevant Links

- 3RD UN Tourism/UNESCO WORLD CONFERENCE ON TOURISM AND CULTURE ‘FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL’

Photo credit of the Summary's cover page: www.banglanatak.com

- Hospitality Industry

Sustainability in Tourism: The socio-cultural lens

November 27, 2020 •

8 min reading

In October 2020, EHL hosted its annual Sustainability Week with a vast array of online seminars, activities and discussion panels. Considering the current impact on the hospitality industry of ongoing COVID-19, the theme of sustainable tourism is more than ever a relevant and urgent topic. Under the direction of Joshua Gan (EHL regional director Asia-Pacific), the issues concerning the socio-cultural aspect of sustainable tourism – its meaning and implementation - were thoughtfully turned over by the two guest speakers: Dr. Peter Varga (Assistant Prof in Sustainability) and Mark Edleson (CEO of Alila Hotels & Resorts).

The definition of Sustainability

According to the Environmental Protection Agency:

Sustainability creates and maintains the conditions under which humans and nature can exist in productive harmony that permit fulfilling the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations.

The analysis of sustainability is often divided into three main perspectives: social, economic and environmental, (also known as “people, profit and planet”). When talking about the social/people aspect, one could argue that an additional perspective needs to be taken into account - that of culture.

1. What is meant by “the socio-cultural aspect of sustainability”?

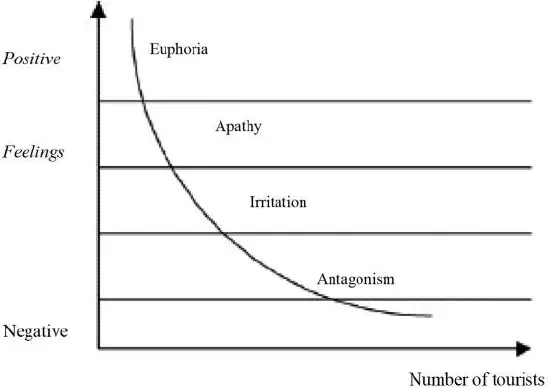

PV: The term refers to, among others, how the local community of a tourism destination is affected by the tourism industry. Hitherto, local cultural frameworks have often been neglected by the mass tourism industry. The perspectives of the tourism hosts should be taken into consideration in a more sustainable way, particularly in the developing world.

Much is normally erased for the sake of modern beach culture, bars, shopping malls, fast entertainment and consumerism. Little attention has been paid to erecting quality, authentic and culturally-rich experiences that benefit both host and visitors. As a result, the majority of todays’ tourism destinations are unsustainable due to various factors such as too fast development and lack of consideration of sustainable parameters, such as the environment and local communities. If tourism is to change and become more sustainable, the aspect of culture must be taken into account.

When we speak of culture in tourism it refers to both host and guest cultures. The goal is to create a harmonious sociocultural environment where long-term sustainable relationships are maintained among all the tourism stakeholders. This may seem excessively idealistic, nevertheless it is worth to try, at least to try and reflect on it in tourism development projects.

ME: Paying attention to the environment is now more pressing than ever. Despite the many labor and environmental regulations, few are actually adhered to. Tourism operators need to understand that sustainable tourism means more than just preserving the beautiful landscape of a tourist destination. It means, for example, respecting village mentality, places of worship, agricultural sites, all that is essential to the upkeep of local cultural identity. Operators have to ask themselves if what they are developing will be beneficial or harmful to the locals. Are they looking to promote mass tourism or quality tourism?

Mass tourism leads to land grabbing, wider roads, more transportation, traffic, pollution – many by-products that initially appear to be generating employment and returns, but that are damaging and simply not sustainable in the long run. The question today is: How to preserve the cultural fabric of a tourist destination?

2. Can you give examples of destinations that have remained socio-culturally intact?

ME: The Alila brand has based itself on a sustainable model from its inception and has tried to preserve as much of the original fabric of local life, culture and nature as possible. We use eco- designed constructions made out of local materials. We incorporate many sustainable initiatives, e.g. local water bottled in reusable glass jars, bamboo straws, organic gardens in the hotels’ compound, compost used from hotel waste, a ‘giving bag’ in each room where guests can leave anything they don’t want to take home, beach cleaning initiatives for staff and guests.

Image credits: Alila Hotels

We try to involve the locals in tourist activities where they are the beneficiaries and that naturally enhance the cultural vocabulary. A very successful initiative has been for local families to open up their homes to host dining experiences for visitors, thereby helping the village integrate the tourists and teach them about the local food and customs. This is precious, authentic interaction for the guests, as well as a means of showing respect to the villagers and developing ties with them. Reaching out respectfully to the community is an crucial step on the road to sustainable tourism.

PV: Some communities have kept their cultural rituals and turned them into interesting tourism features, which is an example of the revitalization of culture. For example, in South Africa, the Zulu dance has become a key tourist attraction, and subsequently, a commodity. Similarly, in other indigenous societies such as in the Amazon rainforest, the shamanistic presentations have become a commodity expected by tourists.

The positive outcome of this cultural ‘commodification’ is its economic benefits for the hosts and also the fact that locals keep the tradition alive. Other less appealing cultural elements for the guest will eventually be lost. Hence, the host culture is expected to adapt to tourism – but this is a fragile set up, because what if the tourism flow suddenly stops, as during this current COVID-19 pandemic? Local societies should not become too dependent on tourism, because it makes them economically fragile in front of unexpected global calamities.

A good example are the Guna people on the Caribbean side of Panama, who have intentionally made their precious small archipelagos an exclusive destination where leakage stays low, so economic benefits stay within their reach.

« The Guna are also one of the rare indigenous groups who seem to be striking a balance between their traditional ways of life and modern conventions. Since 1996, the business of tourism has rested solely in their hands, following a history of showdowns with investors who had seized lands and built luxury hotels and cabins without the blessing of the Guna General Congress. Today, the “Ley Fundamental Guna,” bans the sale or rent of Guna lands to outsiders, including Panamanians, as well as non-Guna investments in their territory. » - Mashable Media

Guana Yala Island (Image Credits: Go2Sanblas )

3. What’s the role of governments and stakeholders?

PV: Tourism has often been treated as a thriving industry by governments, especially in developing nations. However, as mentioned above, the local stakeholders are rarely taken into account, unlike the external ones (banks, developers, expatriate management, etc.) who tend to control everything. It can almost be seen as a form of neo-colonization, where the external stakeholders impose a specific type of development on the destination.

The economic return on mass tourism is considerable, but little attention is paid to the stress this causes to the local people and their culture. Some communities are very fragile in the face of mass tourism, it impacts their quality of life on a daily bases, both on tangible and intangible levels. Mass tourism may allow locals to buy mobile phones while they do not have indoor plumbing at home. Such odd ‘developments’ may generate a very unequal sociocultural environment in the destination. Even in developed countries, (take Venice for example), mass tourism had got so out of hand that the COVID lockdown was seen in many ways as a ‘blessing’ for the environment and many of the locals. There are some archeological sites, such as Angkor Wat in Cambodia to name just one among many, that risks destroying its own ‘raison d’être’ due to the uncontrolled over-tourism phenomenon.

Overtourism problem at Angkor Wat (Image Credits: Good-Travel )

ME: Governments tend to go for numbers, especially in developing countries. They are influenced by a business model that runs on economic drive and targets to be reached. Tourism is seen as an ‘export’. Tourism Officers are elected and their job is to see visitor numbers increase, which in turn causes stress to the local culture. DMCc (Destination Management Companies) have a vested interest in big groups of tourists because they stand to make a profit from tourists visiting certain shops and restaurants. In mass tourism, there’s a big circle of players all looking for their cut.

In the Bali village where I live, local teens are now going to tourism school whereas before they were going to an agriculture college. This was originally an agrarian society based on a farming economy. Land is now being sold to tourism not to farming. Tourism on this island means that some ties have been strengthened, others weakened. In order to strike a more balanced outcome, tourism must be more controlled in the future, even if that means making it more expensive.

4. How can tourists and governments change their mindset?

PV: Tourists need to start thinking about why they are traveling. There is something deeply wrong with the “why not?” mentality fueled by cheap air fares resulting in a few, fast days spent here and there. Travel has to become more purposeful. The idea of slow travel where the objective is to explore and immerse oneself in a new culture over a few weeks should be promoted. Travelers must change their expectations and mindset: show more care about their destination, do better research on simple local cultural specificities such as tipping, dress code, being respectful of the local culture, how to chat with locals, etc. We should do our best to avoid slipping back to pre-COVID times, and reflect on how to make tourism more sustainable.

ME: Ironically, COVID-19 has caused some necessary slowing down, with a refreshing new focus on domestic tourism. On one hand, the pandemic has helped de-emphasize material things, but on the other it has accelerated the craving for experiences. Hence, I am fearful that there will be a return to mass tourism once these restrictive times are over. Much will depend on whether the low-cost carriers are still in business or not. But essentially, it’s up to us, the travelers, to carry out more research into our destination and travel with a greater sense of purpose.

PV: As a brief conclusion of this panel, the future of tourism depends on how much attention we pay to sustainable aspects. The current pandemic has not only revealed a fragile tourism industry, but it’s also shown how stakeholders and destinations are suffering from a situation that, as yet, has no definitive end point. A more sustainable planning mindset, in all aspects of the tourism and travel sector, would enable us to prepare for an uncertain, but hopefully more responsible future.

"Contributing beyond education encourages the EHL community to give back to society by driving sustainable change wherever they live and work, both during and after their education. This is a strong call to action that should empower each of us to do more and play our part in making the world a fair, ethical and sustainable place". - Michel Rochat (CEO, EHL Group)

EHL Insights content editor

Assistant Professor at EHL

Keep reading

The future of luxury experiences: Where luxury meets hospitality

Apr 09, 2024

The potential of green financing for hotel real estate in Asia

Apr 04, 2024

The future of hotel distribution channels: Seizing opportunity in channel disruption

Apr 03, 2024

This is a title

This is a text

- Bachelor Degree in Hospitality

- Pre-University Courses

- Master’s Degrees & MBA Programs

- Executive Education

- Online Courses

- Swiss Professional Diplomas

- Culinary Certificates & Courses

- Fees & Scholarships

- Bachelor in Hospitality Admissions

- EHL Campus Lausanne

- EHL Campus (Singapore)

- EHL Campus Passugg

- Host an Event at EHL

- Contact our program advisors

- Join our Open Days

- Meet EHL Representatives Worldwide

- Chat with our students

- Why Study Hospitality?

- Careers in Hospitality

- Awards & Rankings

- EHL Network of Excellence

- Career Development Resources

- EHL Hospitality Business School

- Route de Berne 301 1000 Lausanne 25 Switzerland

- Accreditations & Memberships

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Terms

© 2024 EHL Holding SA, Switzerland. All rights reserved.

The role of culture as a determinant of tourism demand: evidence from European cities

International Journal of Tourism Cities

ISSN : 2056-5607

Article publication date: 22 April 2022

Issue publication date: 16 March 2023

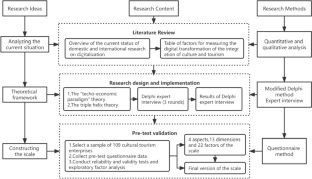

The purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of various cultural amenities on tourism demand in 168 European cities.

Design/methodology/approach

Using data from the European Commission’s Culture and Creative Cities Monitor 2017, a series of regressions are estimated to examine the impact of various cultural amenities on tourism demand while also controlling for other factors that may impact on tourism demand. Diagnostic tests are also conducted to check the robustness of the results.

The results reveal that cultural amenities in the form of sights, landmarks, museums, concerts and shows have a positive impact on tourism demand. By pinpointing the cultural amenities that are important for increasing tourism demand, the findings aid stakeholders in the tourism industry as they develop post-pandemic recovery plans.

Originality/value

This paper identifies two key aspects of the cultural tourism literature that require deeper investigation and aims to address these aspects. Firstly, while many studies focus on a specific or narrow range of cultural amenities, this study includes a series of measures to capture a range of cultural amenities. Secondly, while many studies are narrow in geographical scope, this paper includes data on 168 European cities across 30 countries.

- European cities

Noonan, L. (2023), "The role of culture as a determinant of tourism demand: evidence from European cities", International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 13-34. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-07-2021-0154

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Lisa Noonan

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of culture on tourism demand in 168 European cities. City tourism has been cited as one of the fastest growing travel segments globally ( Bock, 2015 ; Postma et al. , 2017 ). In many European countries, city tourism is a major contributor to the country’s overall tourism gross domestic product (GDP). In 2016, for example, 60.3% of direct tourism GDP in Czech Republic was generated in Prague; in Ireland, 59.1% was generated in Dublin, and Brussels accounted for 52.6% of direct tourism GDP in Belgium ( World Travel and Tourism Council, 2017 ).

Cities are attractive destinations for various segments of the tourist market ( Smolčić Jurdana and Sušilović, 2006 ). Young people are attracted to the nightlife and entertainment as well as sporting events held in the city. Older and more educated tourists are attracted to the cultural heritage of the city ( Smolčić Jurdana and Sušilović, 2006 ). The options available to travellers in a city surpass those of other destination types due to the density of cultural offerings available ( Bock, 2015 ).

The role of culture in attracting tourists to cities has not been overlooked by the tourism industry. Since the 1980s, many destinations have focussed on cultural tourism as a source of economic development ( OECD, 2009 ). This is particularly true in the case of European cities. European cities are increasingly targeting tourism as a key sector for local development and are investing in cultural attractions and infrastructure to secure a niche position in the tourist market ( Russo and van der Borg, 2002 ). In some cities that have experienced deindustrialisation, old manufacturing spaces have been designated for cultural or tourist activities ( Alvarez, 2010 ). In Bilbao, for example, the building of the Guggenheim Museum marked the beginning of the regeneration of the city and many old industrial sites were converted into parks and cultural spaces ( Alvarez, 2010 ). According to Richards (1996a ), the European cultural tourism market is becoming progressively more competitive with an increasing number of European Union cities and regions developing their tourism strategies around cultural heritage. The opening up of Central and Eastern Europe has also led to the development of “new” cultural tourism destinations ( Richards, 1996a , p. 4).

The contribution of culture to tourism has received extensive consideration in the academic literature. There are, however, two notable shortcomings in the literature. Firstly, the range of cultural amenities considered in the literature is limited. Many studies focus on a narrow range of cultural amenities with many of the cultural amenities listed by the UNWTO (2019) being overlooked. Secondly, studies are narrow in geographical scope, with many studies focusing on a specific location or multiple locations within a specific country. Location-specific case studies are useful as they allow for in-depth analyses on the contribution of culture to tourism demand. However, difficulties may arise when making generalisations from the findings of such site-specific analyses ( Chen and Rahman, 2018 ). Cross-sectional analyses, which incorporate a range of cultural amenities and geographic locations, would provide a more detailed insight into how culture impacts on tourism demand.

This paper contributes to the literature by examining the impact of different cultural amenities on tourism demand across 168 European cities. Using data from The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor, published by the European Commission (2017) , a series of regressions is estimated. Using the various measures, it is possible to pinpoint the exact cultural amenities that affect tourism demand.

The concept of cultural tourism is explained and a review of the literature is presented in Section 2. The data are presented in Section 3. The method of analysis is outlined in Section 4. The results are presented in Section 5. Finally, discussion and conclusions are presented in Section 6.

2. Aspects of cultural tourism literature

This section begins by defining cultural tourism. Two notable features of existing literature in the field are identified and discussed in subsections 2.2 and 2.3.

2.1 Defining cultural tourism

The term “cultural tourism” is frequently used in conceptual models that include culture as a key determinant of tourism competitiveness, for example, Crouch and Ritchie’s (1999) model of destination competitiveness and the integrated model of destination competitiveness ( Dwyer et al. , 2004 ). However, how best to define cultural tourism has been the subject of much debate ( Richards 1996b ; Richards, 2018 ). Various definitions can be found in the literature; see for example, Silberberg (1995) , Richards (1996b ), Richards (2000) . One of the most comprehensive definitions is provided by World Tourism Organization (UNWTO):

Cultural tourism is a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination. These attractions/products relate to a set of distinctive material, intellectual, spiritual and emotional features of a society that encompasses arts and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries and the living cultures with their lifestyles, value systems, beliefs and traditions ( UNWTO, 2019 , p. 30)

In discussing an earlier publication of the definition above, Richards (2018 , p. 13) contends that it “confirms the much broader nature of contemporary cultural tourism, which relates not just to sites and monuments, but to ways of life, creativity and ‘everyday culture’”. A broad definition is important as opinions on what constitutes culture tend to vary among stakeholders. For example, in a survey of member states, The World Tourism Organisation (2018) asked countries what aspects they included in cultural tourism. Total, 97% of respondents included aspects of tangible heritage such as heritage sights and monuments. Total, 98% included intangible heritage such as traditional festivals, music and gastronomy. Total, 82% included other contemporary cultures and creative industries including film, performing arts and fashion ( World Tourism Organisation, 2018 ). As such, empirical analyses should consider a multitude of cultural offerings when assessing the impact of culture on tourism demand.

Many of the cultural amenities listed in the UNWTO (2019) definition have been overlooked in the literature. Specifically, many studies focus on one or a small number of cultural amenities in their analyses. They also tend to focus on a specific country or subdivisions of a country. These two features of the literature are discussed in the next sections.

2.2 Studies tend to focus on specific cultural amenities

Many studies on cultural tourism tend to focus on a specific cultural amenity or a narrow range of amenities. Museums receive much attention. The interest in museums is unsurprising given that they can offer an insight into a specific location and time and as such, may be unique to the destination ( Stylianou-Lambert, 2011 ). Many types of museums are considered including state ( Cellini and Cuccia, 2013 ) and capital-city museums ( Carey et al. , 2013 ) as well as museums operating in more niche areas, such as art museums ( Stylianou-Lambert, 2011 ), transport museums ( Xie, 2006 ; Akbulut and Artvinli, 2011 ) and Holocaust museums ( Miles, 2002 ; Cohen, 2011 ). Their impact on tourism is mixed. Some studies reveal that museums have a positive effect on tourism demand Plaza (2000) , Carey et al. (2013) . The presence of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao appears to be particularly important for tourism. Visitors to the museum accounted for 58% of tourism growth in the Basque Country between 1997 and 1999 ( Plaza, 2000 ). By contrast, Cellini and Cuccia (2013) find evidence of bi-directional causality between attendance at museums and monuments and tourism flows in Italy in the long run.

While museums receive considerable attention, Cellini and Cuccia (2013) contend that focussing solely on museums and monuments is too strict as a measure of culture. Various other cultural amenities are also considered from a tourism perspective. For example, Di Lascio et al. (2011) find that modern art exhibitions have a positive one-year lagged effect on tourism. Contemporary art exhibitions also have a positive impact on tourism flows when the organisation of such exhibitions is continuous over time ( Di Lascio et al. , 2011 ). The importance of culinary heritage as a cultural tourism product is also evident in the literature. Du Rand et al. (2003) find that food plays a role in tourism in South Africa. Likewise, local gastronomy is considered a tourist attraction in Quito ( Pérez Gálvez et al. , 2017 ). Visitors to Córdoba want to taste the local cuisine as well as enjoying the historic and cultural heritage ( Beltrán et al. , 2016 ).

UNESCO World Heritage Sites (WHS) also receive considerable attention, for example, Cuccia et al. , 2016 ; Yang et al. , 2019 ; Canale et al. , 2019 ; Castillo-Manzano et al. , 2021 . However, even within the same country, their impact on tourism appears to be mixed. In Spain, cultural WHS have a positive impact on tourism numbers in inland provinces while only natural WHS have a positive impact on tourism numbers in coastal regions ( Castillo-Manzano et al. , 2021 ). The presence of WHS is negatively correlated with the technical efficiency of tourism destinations in Italian regions ( Cuccia et al. , 2016 ). However, in Italian provinces, the number of WHS increases international tourist arrivals by 6.9% ( Canale et al. , 2019 ).

While detailed studies on specific cultural amenities offer interesting insights, Cellini and Cuccia (2013) believe that different types of cultural amenities may have different relationships with tourism flows and recommend research into the same ( Cellini and Cuccia, 2013 ). Guccio et al. (2017) contribute to the literature by including a range of measures of culture in their study which examines the effects of cultural participation on the performance of tourism destinations. The amenities considered include theatres, cinemas, museums, sports and music events, discotheques and archaeological sites. They find that cultural friendly environments positively affect the performance of tourism destinations ( Guccio et al. , 2017 ). Their paper focuses solely on Italian regions.

Cultural amenities have a positive and significant impact on tourism demand.

The next section discusses this paper’s second key observation.

2.3 Studies tend to be narrow in geographical scope

The narrow geographical scope of many studies is a notable feature of the literature. There are many examples of studies that focus on a specific cultural amenity and tend to be location specific. For example, Mi’kmaw culture in Nova Scotia ( Lynch et al. , 2010 ), language tourism in Valladolid ( Redondo-Carretero et al. , 2017 ), communist heritage tourism in Bucharest ( Sima, 2017 ) and the development of cultural heritage in Gozo ( Borg, 2017 ).

Detailed case studies on specific locations are useful as they allow for in-depth analyses on the contribution of culture to tourism demand. They also aid policymakers and the stakeholders in the tourism industry when tailoring policies and initiatives specific to the location in question. However, difficulties may arise when making generalisations from the findings of such sight-specific analyses ( Chen and Rahman, 2018 ). For example, Cellini and Cuccia (2013 , p. 3481) contend that their findings for Italy should be tested in other countries as the management of Italian cultural sights is “less flexible and less market-oriented” relative to other countries, and as such, the management style may influence the findings. As such, cross-sectional analyses, which incorporate a range of geographic locations, would provide a more detailed insight into how cultural amenities impact on tourism demand.

There are, of course, studies that consider a cross-section of locations. Many of these focus on regions or provinces within a specific country, for example, Di Lascio et al. (2011) , Cuccia et al. (2016) , Guccio et al. (2017) , Canale et al. (2019) , Castillo-Manzano et al. (2021) . However, there tends to be considerably less literature that focuses on regions or cities across countries. This study contributes to the literature by empirically estimating the impact of different cultural amenities on tourism demand in 168 European cities spanning 30 European countries. The data used are discussed in the next section.

3. Data to be analysed

Data are from The Culture and Creative Cities Monitor 2017, which was carried out by the European Commission. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor is a tool to assess and monitor the performance of cultural and creative cities in Europe relative to their counterparts using quantitative and qualitative data ( European Union, 2017 ). The monitor moves away from the narrow economic perspective of culture by including a diverse range of indicators ( Montalto et al. , 2019 ). See Montalto et al. (2019) for a detailed discussion of data collection, treatment and the construction of the overall index.

In deciding what cities to include in the monitor, different criteria were considered, see Montalto et al. (2019) . In the final sample, data are available for 168 European cities covering 30 European countries. See Appendix 1 for list of cities included. To be included in the monitor, the cities had to meet one of the following three criteria. Firstly, they have been or will be a European Capital of Culture up until 2019 or have been shortlisted to become a European Capital of Culture up until the year 2021. Of the 168 cities included, 93 cities meet this criterion ( European Union, 2018a ). Secondly, the city is a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Creative city. A further 22 cities meet this criterion ( European Union, 2018a ). Thirdly, the city hosts at least two regular international cultural festivals up until, at least, 2015. A further 53 cities meet this criterion ( European Union, 2018a ).

Initially, almost 200 indicators were considered for inclusion in The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor based on a literature review and expert consultation. After the data was screened and tested for statistical coherence, 29 indicators were selected ( European Union, 2018b ). Data are available for 29 indicators which are relevant to the cultural vibrancy, creative economy and enabling environment of the cities ( European Union, 2017 ). Most of the indicators are denominated in per capita terms to enable cross-city comparison ( European Union, 2018a ); see Table 1 . If the distribution of a variable deviated significantly from the normal distribution, winsorisation was used to trim the outliers ( European Union, 2018a ). Missing observations were imputed when constructing the monitor. See European Union (2018a ) for full details of data imputation techniques. Both the imputed and actual observations are included in the regression analysis as to remove the imputed observations would greatly reduce the degrees of freedom available. The data are scaled from 0 to 100. As such, for each of the variables, 0 represents the lowest performance in the data set and 100 represents the highest performance in the data set ( European Union, 2018a ). See Appendix 2 for an interpretation of the scale used. Table 1 presents the variables included in the analysis. The reference period is also included for each of the variables. While the reference periods vary for each of the variables, this should not be a problem as the variables have been used collectively as inputs in The Culture and Creative Cities Monitor 2017 to form the overall aggregate C3 index. European Union (2018b , p. 2) state that the variables included in the index “were selected with respect to statistical coherence, country coverage and timeliness”. In fact, it is not uncommon in econometric analysis to include variables from different reference periods; see, for example, Kim et al. (2000) , Alkay and Hewings (2012) , Noonan et al. (2021) .

The dependent variable is Tourist overnight stays ; see Table 1 . This is a measure of tourism demand. While measures of tourist expenditure and tourist arrivals are most commonly used to measure tourism demand ( Song et al. , 2010 ), measures based on overnight stays also exist in the literature, for example, Garín-Muñoz and Amaral (2000) , Falk (2010 , 2013 ), Falk and Lin (2018) . Tourist overnight stays is selected in this analysis for two reasons. Firstly, data on tourist expenditure are normally collected through visitor surveys and are often subject to biases due to the method of data collection ( Song et al. , 2010 ). Secondly, data on the number of overnight stays is useful as it captures the duration of the stay. This cannot be gauged by looking at the number of tourist arrivals. Garín-Muñoz (2009) uses data on the number of overnight stays rather than the number of visitors to measure tourism demand in Galicia for this particular reason. Furthermore, Song et al. (2010) claim that the volume of tourist arrivals does not account for the economic impact of the tourists.

The primary purpose of this analysis is to examine the impact of culture on tourism demand. Therefore, five measures of culture are included to capture various cultural amenities; see Table 1 . Following the World Tourism Organisation (2018) , tangible cultural amenities are captured in the variables sights and landmarks and museums . Intangible cultural amenities are captured by concerts and shows . Cinema seats and theatres capture aspects of other contemporary cultures and creative industries. While this is not an exhaustive list of all aspects of culture, it is the broadest range of measures available for all 168 cities in the year being studied. As the aforementioned measures are volume based, Satisfaction with cultural facilities is also included to account for the opinions of the population in relation to cultural facilities. This measures the percentage of the population that is very satisfied with the cultural facilities in the city.

Following Canale et al. (2019) , a series of control variables are also included. This is standard in regression analysis. These variables control for other factors that may also impact on tourism demand in European cities. While many interesting variables are included in the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor, the number of controls variables that can be included is constrained by the low number of degrees of freedom in the model. As such, it is important that those included are carefully selected based on theoretical considerations and existing empirical studies.

Van den Berg et al. (1995) propose a model that focuses specifically on the attractiveness of urban locations for tourism. Accessibility features heavily in their model. Three measures of transport are included to capture air ( passenger flights ), rail ( direct trains to other cities ) and road (potential road accessibility) accessibility. Measures of air accessibility are common in the literature; for example, Cho (2010) , Di Lascio et al. (2011) , Canale et al. (2019) . As this is a city-level study, measures of rail and road accessibility are also included. It is possible that tourists to the city may be domestic tourists who travel via the road or rail network or international tourists who make a rail connection to the city after arriving in the country and/or use the road network to visit multiple destinations during their visit.

Image is also a feature of the Van den Berg et al. (1995) model. Van den Berg et al. (1995) claim that the city must have an appealing image to attract tourists. They do, however, acknowledge that it is difficult to assess the extent to which image impacts on tourist’s destination choice ( Van den Berg et al. , 1995 ). This may be linked to the difficulty in finding a quantitative proxy to capture image. To proxy for this, two variables are included in this analysis: Tolerance of foreigners and Quality of Governance . They were chosen on the premise that a tolerant city with an educated population, with good health care and a high standard of law enforcement may be viewed as a “safe” destination choice by tourists. This reflects Tang (2018) who contends that a high quality of governance may signal a high level of security thus increasing inbound tourism demand. Canale et al. (2019) also control for crime and health care.

As well as being centres of culture and entertainment, cities are also centres of economic and political power ( Ashworth and Page, 2011 ). As many visitors travel to cities for the latter, it is possible that cities with modest cultural capital can attract as many travellers as those cities with greater cultural capital ( Ashworth and Page, 2011 ). To control for this a capital city dummy variable is included as many European capital cities are the major economic and political powerhouses in their respective countries.

A series of dummy variables are also included to control for the level of GDP per capita and population in the city. GDP per capita is a proxy for income. Various GDP-based measures are used as proxies of income in the literature; see, for example Lim (1997) , Yang and Wong (2012) , Marrocu and Paci (2013) , Leitão (2010) , Dogru et al. (2017) .. The GDP per capita and population groups are taken directly from the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor. For GDP per capita, data are not available at the city level but at the metro-region and NUTS 3 regional levels. Metro-regional level data was used where available ( European Commission, 2017 ).

A series of population dummy variables are included to control for differences in city size. See Law (1992) for a detailed discussion on the attractiveness of large cities for tourism.

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2 . The highest and lowest observations are presented in Table 3 . There is a broad geographical distribution in terms of the top and bottom performing cities for Tourist Overnight Stays . The highest values for the variable are in Budapest (Hungary), Karlovy Vary (Czech Republic) and York (UK). With scores of 100, the three cities are performing strongly relative to the mean score of 20.05. Tourist overnight stays are lowest in Zaragoza (Spain), Baia Mare (Romania), Lublin (Poland) and Osijek (Croatia).

Italian and Irish cities are among the top performers in terms of culture. Venice (Italy) is the top-ranking city for both sights and landmarks and museums , receiving the maximum score of 100 for both measures. The values of 100 are substantially higher that the European city means of 23.45 and 23.51 for the variables. Limerick (Ireland) has the third highest score behind other Italian cites Matera ( sights and landmarks ) and Florence ( museums ) for both variables. For concerts and shows , the top performing three cities are all Irish. Italian and Irish cities, however, are not represented in the top three cities for cinema seats and theatres .

In terms of the weakest scores for culture, Lódź (Poland) is in the bottom three cities for both sights and landmarks and concerts and shows . Patras (Greece) is among the weakest performers for both sights and landmarks and museums . Two German cities, Mannheim and Essen feature in the bottom three cities for Theatres . The populations of Lyon and Vienna express the greatest satisfaction with cultural facilities ( satisfaction with cultural facilities) .

The mean score for passenger flights is 17.58 with a standard deviation of 20.43. Seven cities are tied on a score of zero. Amongst the poorest ranking cities are Baia Mare, Lublin and Osijek which are also amongst the lowest ranking cities in terms of tourist overnight stays . London is the top-ranking city with a score of 100. It is followed by two Dutch cities; Eindhoven (89.3) and 's-Hertogenbosch (87.3) in second are third place respectively. Dutch cities are also performing well in terms of rail accessibility; Leiden and 's-Hertogenbosch are in the top three cities for the variable direct trains to other cities . Twelve cities are tied at the lowest score of zero. The top three performers in terms of potential road accessibility are all German cities; Cologne, Essen and Bochum. Eight cities are tied at a score of zero.

Tolerance of foreigners has a mean score of 41.47 and a standard deviation of 24.29. Cluj-Napoca scores highest and as such, is deemed the most tolerant. The least tolerant are dominated by the Greek cities of Kalamata, Patras, Athens and Thessaloniki. Along with Turin, they all achieve a score of zero. The mean score for quality of governance is 64. The top-ranking cities are all Scandinavian cities. Each of the top four display scores greatly in excess of the mean. However, the poorest performing cities, Sofia (Bulgaria), Naples (Italy) and Bucharest (Romania) score very poorly relative to the mean with scores of 0, 8.2 and 8.5.

Of the sample, 17.86% comprises capital cities. There is a spread between each of the GDP per capita and population categories. The next section outlines the method of analysis.

4. Method of analysis

To conduct the analysis, equation (1) is estimated using an ordinary least squares (OLS) estimator. OLS is a commonly used regression technique that minimises the sum of the squared residuals in calculating the estimated regression coefficients ( Studenmund, 2001 ): (Equation 1) D i = β 0 + β 1 C i + β 2 Z i + ε i

D i measures tourism demand in city i as measured by tourist overnight stays . C i is a matrix of variables that measure culture in city i. Z i represents a series of control variables which include other factors that affect tourism demand in city i . Variables are discussed in Section 3. All continuous variables are in natural logs.

It is expected that the coefficients for β 1 and β 2 will be positive.

Prior to conducting the econometric analysis, a value of +1 is added to each of the continuous variables to allow natural logs of each variable to be taken. A series of diagnostic tests are also conducted. Firstly, the Shapiro–Wilk test is estimated to determine if the variables are normally distributed. The null hypothesis is the variables are normally distributed. The results of the test are presented in Appendix 3 . The results reveal that the dependent variable, tourist overnight stays and the independent variables sights and landmarks , museums and concerts and shows are normally distributed, while the other continuous variables are not. As the assumption of normality is not a requirement for OLS estimation ( Studenmund, 2001 ), this should not cause any serious issues.

Tests are also conducted post-estimation for heteroscedasticity. Heteroscedasticity violates the assumption of constant variance for observations of the error term ( Studenmund, 2001 , p. 345). Two tests are conducted to check for the presence of heteroscedasticity. Firstly, a Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test is conducted post-OLS estimation. The null hypothesis is constant variance. If the null hypothesis is rejected heteroscedasticity is present within the model. Secondly, White’s test is conducted. The null hypothesis is homoscedasticity. If the null hypothesis is rejected heteroscedasticity is present within the model. Although, heteroscedasticity violates the assumption of constant variance, OLS estimators remain unbiased in its presence Studenmund (2001) , Gujarati and Porter (2009) . As such, it is not as serious a concern in this analysis as multicollinearity.

Multicollinearity describes the occurrence of a perfect linear relationship among some or all of the independent variables, as well as the situation whereby the independent variables are intercorrelated ( Gujarati and Porter, 2009 , p. 323). OLS estimators will have large variances and covariances in the presence of multicollinearity which can make precise estimation difficult. The confidence levels also tend to be wider in the presence of multicollinearity leading to a greater acceptance of the zero-null hypothesis ( Gujarati and Porter, 2009 , p. 327). Variance-inflating factor (VIF) tests are conducted post regression as a check for multicollinearity. The VIF displays the speed with which variances and covariance increase and shows how the variance of an estimator can be inflated by multicollinearity ( Gujarati and Porter, 2009 , p. 328). Generally, if the VIF of a variable is greater than 10 it said to be highly collinear ( Gujarati and Porter, 2009 ; Kennedy, 2008 ).

Given that there are six measures of culture, three measures of transport and two measures relating to the institutions of cities, it is expected that some of these variables will be correlated with each other. While the VIF tests provide the primary means of identifying multicollinearity in this analysis, a correlation matrix of the continuous independent variables is generated pre- regression as a pre-emptive measure to identify any highly correlated variables which may lead to multicollinearity in the models. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is used to estimate the correlation between the continuous variables. Kennedy (2008 , p. 19) describes a high correlation coefficient between two independent variables to be “0.8 or 0.9 in absolute value”.

Ramsey’s RESET test is also conducted post-OLS estimation to determine whether there are omitted variables in the analysis. Ramsey’s RESET runs an augmented regression that includes the original independent variables, powers of the predicted values from the original regression as well as powers of the original independent variables ( Baum, 2006 , p. 122). The null hypothesis is that the model has no omitted variables. If the null hypothesis is rejected the model may be misspecified. Omitted variable bias is a cause of endogeneity.

Endogeneity may also arise from simultaneity in the model. For example, it may be the case that airlines and train networks respond to increases in tourism demand in particular cities by providing more flights and trains to and from those cities. See Cho (2010) for a discussion on possible endogeneity of airline data. As such, an IV generalised method of moments (GMM) estimator will also be estimated to include instruments for potentially endogenous variables. The instruments are constructed using the three-group method commonly used in economic literature; see for example, Noonan, 2021 ; Noonan et al. , 2021 . This involves separating the endogenous variable into three groups of equal size and then creating an instrumental variable which take values of −1, 0 and +1 depending on whether the observation is in the lowest, middle or highest group of observations ( Kennedy, 2008 , p. 160). The Difference-in-Sargan test ( C statistic) is calculated after the IV GMM regression to test for endogeneity. If the null hypothesis of exogeneity is rejected, the model includes endogenous variables and the IV GMM estimator would be more appropriate than the OLS estimator ( Noonan, 2021 ). The results are presented in the next section.

Table 4 presents the correlation matrix of the independent variables used. The matrix reveals that correlations between most variables appear to be weak to moderate. The coefficient of 0.777 between the variables sights and landmarks and museums is the strongest correlation in the matrix. There are also moderate correlations (in excess of 0.5) between museums and concerts and shows and between passenger flights and direct trains . To avoid the problem of multicollinearity, the moderately and highly correlated variables will be entered into separate regressions.

Table 5 presents the result of eight estimations of Equation (1) . Estimations i to vi are OLS estimations. Estimations vii and viii are GMM estimations. All estimations are statistically significant. VIF tests are conducted post-OLS estimation. With mean VIF values ranging from 1.32 to 2.08, it can be concluded that multicollinearity is not a problem. Breusch-Pagan test statistics are estimated for the dependent and independent variables after estimations i to vi. The test statistics are statistically insignificant in all estimations indicating that heteroskedasticity is not a problem. Similarly, the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity cannot be rejected in White’s test for estimations i to vi. The Ramsey RESET test statistic is also statistically insignificant in all estimations. As such, the models are not affected by omitted variable bias.

The variable road accessibility is found to be endogenous. This is instrumented in estimations vii and viii. The C statistic is statistically significant. As such, the null hypothesis of exogeneity is rejected. This suggests the IV GMM estimates are more appropriate than the OLS estimates [ 1 ].

While the GMM estimations are the primary focus of the interpretation, there appears to be similarities across all eight estimations presented. The results provide some evidence to support Hypothesis 1; cultural amenities have as a positive and significant impact on tourism demand. Sights and landmarks , museums and concerts and shows , are positive and significant in both OLS and GMM estimations. They are significant at the 99% confidence level in all estimations. There is also some evidence to suggest that satisfaction with cultural facilities is also a determinant of tourist overnight stays. Satisfaction is positive and significant at the 95% confidence level in Estimation vii. The positive finding for cultural amenities is consistent with positive findings for culture in the empirical literature; for example, Plaza (2000) and Carey et al. (2013) . Greater endowments of sights, landmarks, museums and more concerts and shows as well as satisfaction with cultural facilities leads to increased tourism demand in European cities. The range of cultural amenities that affect tourism demand is interesting. While cities may be endowed with cultural amenities such as sights and landmarks that are centuries old, the significant finding for museums and concerts and shows suggests that culture can be created in cities that do not boast large-scale historical sights and landmarks.

The variable cinema seats is not statistically significant in the estimations. Unlike sights, landmarks and museums which are unique to specific cities and concerts and shows which may only be held in a limited number of locations, cinemas tend to be widely available across cities and cinema offerings are likely to be relatively homogenous across space. Therefore, cinema facilities are unlikely to be a key amenity in attracting tourists to the city. This may explain the insignificant finding.

The variable capturing the availability of theatres is also statistically insignificant in all estimations except for Estimation v where it is negative and significant at the 90% confidence level. It may be the case that the shows offered in the theatres and possibly in the cinemas, may not be produced with tourists in mind. For example, Ben-Dalia et al. (2013) find that theatres in Tel Aviv tend not to offer English or French language translations. If a language barrier exists, this makes cinema and theatre offerings unattractive to tourists.

In terms of the control variables, accessibility, in the form of passenger flights , is statistically insignificant in the GMM estimations. This is unexpected and is not consistent with Van den Berg et al. (1995) , Russo and Van der Borg (2002) and Cho (2010) . Road Accessibility is also statistically insignificant. The variable capturing direct trains to other cities is, however, statistically significant at the 90% level in estimation viii. It must be noted that this study does not distinguish between domestic and international tourists and as such, this may be reflected in the results. It may be the case that domestic tourists are more likely to use the rail network than air transport when visiting cities. In the case of Italy, for example, the car is the most common mode of transport for domestic tourists ( Marrocu and Paci, 2013 ).

Quality of governance and tolerance of foreigners are statistically insignificant in both GMM estimations. This suggests that the variables are not significant determinants of tourism demand in European cities. This contrasts with Tang (2018) who finds that institutional quality is positively related to tourism demand in Malaysia and Mushtaq et al. (2021) who find evidence of institutional quality having a positive impact on tourism arrivals in India.

The capital city dummy variable is also statistically insignificant in both GMM estimations. This suggests that tourism demand is not significantly different in capital cities than in other European cities. However, the GDP per capita and population of cities appear to play a role. Two of the GDP per capita variables are significant in the GMM estimations. Cities with GDP per capita of 20,000–25,000 and <20,000 experience significantly less tourist overnight stays than cities with GDP per capita >35,000. The significant finding for income is consistent with Yang and Wong (2012) who contend that cities with higher incomes can allocate more resources to tourism development. The significant finding is also consistent with Marrocu and Paci (2013) who describe higher income areas as being more likely to attract more business trips and provide better quality public services which are important components of the product provided to tourists ( Marrocu and Paci, 2013 ).

Relative to cities with populations in excess of one million, tourism demand is significantly lower for all cities with populations of less than one million. This finding is not unexpected. Law (1992) identifies that large cities are attractive for visitors due to business activities, retail facilities, sports and culture as well as visits to friends and family. Large cities have many advantages for hosting conferences such as accessibility, accommodation and urban amenities ( Law, 1992 ). Cities with larger populations are also bases for prestigious sports teams ( Law, 1992 ), which may lead to increased sports tourism.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of a range of cultural amenities on tourism demand in 168 European cities. In doing so, it addresses two notable shortcomings in the literature. Firstly, it addresses the narrow range of cultural amenities considered in much existing literature by including measures of five cultural amenities. Secondly, while studies tend to be narrow in geographical scope, this paper fills a gap by considering 168 European cities spanning 30 countries. The broad geographical scope of this study is important as it allows stakeholders in the tourism industry to gauge the importance of culture for tourism demand. The results should allow for more informed decision-making to take place as the findings are not specific to a particular location but are relevant across 168 European cities.

Using data from The Culture and Creative Cities Monitor 2017, a series of regressions are estimated. Due to the presence of endogeneity in the road accessibility variable, the GMM estimations are more robust than the OLS estimations and are the focus of the discussion. The results of the analysis reveal that culture, in the form of sights and landmarks, museums, concerts and shows, is a determinant tourism demand across 168 European cities. Satisfaction with cultural facilities in the city is also an important determinant. The insignificant findings for cinema seats and theatres in the GMM estimations are important as they reveal that not all cultural amenities are of equal relevance in stimulating tourism demand. The differing findings for the various cultural amenities support the opinion of Cellini and Cuccia (2013) who believe that different types of cultural amenities may have different relationships with tourism flows.

From a political perspective, important implications can be drawn from this analysis. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global tourism industry has been badly affected. Travel restrictions have led to a contraction in tourist numbers in many destinations. As countries enter the recovery stage of the pandemic, they will be eager to stimulate tourism demand and facilitate the recovery of the tourism industry. Some governments have already pledged financial support to aid recovery of the sector. For example, in Ireland, a record level of funding of €288.5m has been allocated to the tourism sector in Budget 2022 ( Government of Ireland, 2021 ). A certain amount of funding could be allocated to cities to promote and develop their cultural amenities. For example, governments could provide financial support to the tourism industry to develop marketing campaigns based on the cultural amenities of the cities. Funding could also be allocated to cities to support them in staging a music festival or series of concerts.

Hosting concerts and shows is an avenue that stakeholders in the tourism industry should seriously consider as an opportunity for increasing tourism demand in their cities. While there is obviously a lot of resources, including time, financial resources and manpower, required to host concerts, such events could provide a lucrative means of increasing tourism demand in cities. It is important that all stakeholders in the tourism industry work together to facilitate the recovery of the industry in their cities post-pandemic. This may involve, for example, national governments providing financial supports, local governments and councils issuing licences and permits for such concerts and shows where required as well as ensuring adequate public utilities and services are in place for tourists in their cities. Those working in the tourism industry could oversee the overall organisation and promotion of the event as well as engaging with proprietors and managers from the accommodation and food services sector in the city to arrange for various packages to be put in place for prospective visitors. Given that many concerts, internationally, are held in venues such sporting arenas and open-air sites, it is possible that many European cities would have access to locations to stage such events without having to make large-scale capital investments in terms of building concert halls or event centres. As such, hosting such events could be a viable option to facilitate recovery in many European cities.

The findings of this study also have managerial implications for business operating within the tourism industry. The different findings for the various cultural amenities are relevant from a European industry and policy perspective as it allows stakeholders to identify the cultural amenities that have the greatest impact on tourism in their cities. Therefore, they may put a greater emphasis on the sights, landmarks, museums concerts and shows on offer when promoting their cities to potential tourists. Similarly, tour operators within the cities may design tailored daytrips to the specific cultural amenities that are attractive to tourists.

While sights and landmarks may be associated with the history of a city, not all cultural amenities have to be inherited. Cultural amenities, in the form of hosting concerts and shows, can be actively created in the city. This is particularly positive for cities that are not endowed with numerous cultural sights and landmarks and for cities that do not house many museums. This suggests that culture does not have to be inherited but can be created. Russo and van der Borg (2002) acknowledge that not all cities have a “sufficient mass” of cultural assets and therefore, the assets they possess should be promoted in conjunction with other tourist attractions including events, gastronomy and quality infrastructure and regional networks ( Russo and van der Borg, 2002 , p. 631). Even if a city has a sufficient mass of sight and landmarks, developing alternative cultural amenities is important as Carey et al. (2013) contend that, in the long term, a single successful attraction is insufficient to sustain a destination. Rather, a combination of complementary formal and informal cultural attractions is required to maintain tourist arrivals.

The positive finding for culture is important as it is a product that can be offered throughout the entire year. As such, it provides a means of attracting tourists during the off-peak tourism season. Evidence suggests that there is less seasonality in tourism flows in cultural destinations relative to other destinations ( Cuccia and Rizzo, 2011 ). Greater promotion of the cultural amenities in their cities is something that the tourism industry should consider, as it may provide a lucrative means of increasing tourism demand. This will be particularly important in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic as many businesses develop recovery strategies.

This study provides a first large-scale attempt of econometrically testing the impact of various cultural amenities on tourism demand across 168 different cities. As such, it is not without limitations. The limitations are primarily due to a lack of available data. While various aspects of culture are included in the study, this is not by any means an exhaustive list of cultural amenities. The UNWTO (2019) definition of cultural tourism includes aspects such as culinary heritage, literature and the beliefs and traditions associated with different cultures. It would be worthwhile to also include these aspects in the analysis, but lack of available data means that they cannot be included. It would also be worthwhile to include more qualitative measures of culture into the analysis to gauge the attitudes of tourists towards the various cultural amenities. Primary data collection may be necessary to study such aspects. This is an area for future research.

Furthermore, the dependent variable considers tourist overnight stays in accommodation but does not distinguish between domestic and international visitors to the city. It is possible that cultural amenities may have a different level of importance for the different categories of visitors. For example, Ryan (2002) finds that domestic non-Maori New Zealanders are not attracted to the Maori cultural tourism products to the same extent as Europeans and North Americans. Due to data limitations, it is not possible to make the distinction between domestic and international tourists in this study. Such a distinction would be worthy of further analysis.

Finally, the data used are from The Culture and Creative Cities Monitor 2017. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first year for which this monitor has been published. When future additions become available, it would be worth conducting an analysis over a 5- or 10-year period to identify if there are any changes in the effects of culture on tourism demand over time.

Variables included in the analysis

*** Denotes significant at 99% level, ** denotes significant at 95% level and * denotes significant at 90% level

Source: Calculations author’s own based on data from European Commission (2017)

Multiple IV estimations were run, and instruments were included for a range of potentially endogenous variables. As road accessibility was the only endogenous variable, the other estimations are not included here.

Appendix 1. List of cities included in analysis

Appendix 2. interpretation of 0–100 scale, appendix 3. shapiro–wilk test.

Akbulut , G. and Artvinli , E. ( 2011 ), “ Effects of Turkish railway museums on cultural tourism ”, Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 19 , pp. 131 - 138 .

Alkay , E. and Hewings , G.J.D. ( 2012 ), “ The determinants of agglomeration for the manufacturing sector in the Istanbul metropolitan area ”, The Annals of Regional Science , Vol. 48 , pp. 225 - 245 .

Alvarez , M.D. ( 2010 ), “ Creative cities and cultural spaces: new perspectives for city tourism ”, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research , Vol. 4 No. 3 , pp. 171 - 175 .

Ashworth , G. and Page , S.J. ( 2011 ), “ Urban tourism research: recent progress and current paradoxes ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 15 .

Baum , C.F. ( 2006 ), An Introduction to Modern Econometrics Using Stata , Stata Press , Texas .

Beltrán , J.J. , López-Guzmán , T. and González Santa-Cruz , F. ( 2016 ), “ Gastronomy and tourism: profile and motivation of international tourism in the city of Córdoba, Spain ”, Journal of Culinary Science and Technology , Vol. 14 No. 4 , pp. 347 - 362 .

Ben-Dalia , S. , Collins-Kreiner , N. and Churchman , A. ( 2013 ), “ Evaluation of an urban tourism destination ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 15 No. 2 , pp. 233 - 249 .

Bock , K. ( 2015 ), “ The changing nature of city tourism and its possible implications for the future of cities ”, European Journal of Futures Research , Vol. 3 No. 20 , pp. 1 - 8 .

Borg , D. ( 2017 ), “ The development of cultural heritage in GOZO and its potential as a tourism niche ”, International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 3 No. 2 , pp. 184 - 195 .

Canale , R.R. , De Simone , E.D. , Maio , A. and Parenti , B. ( 2019 ), “ UNESCO world heritage sites and tourism attractiveness: the case of Italian provinces ”, Land Use Policy , Vol. 85 , pp. 114 - 120 .

Carey , S. , Davidson , L. and Sahli , M. ( 2013 ), “ Capital city museums and tourism flows: an empirical study of the museum of New Zealand Te papa tongarewa ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 15 No. 6 , pp. 554 - 569 .

Castillo-Manzano , J.I. , Castro-Nuño , M. , Lopez-Valpuesta , L. and Zarzoso , Á. ( 2021 ), “ Assessing the tourism attractiveness of world heritage sites: the case of Spain ”, Journal of Cultural Heritage , Vol. 48 , pp. 305 - 311 .

Cellini , R. and Cuccia , T. ( 2013 ), “ Museum and monument attendance and tourism flow: a time series analysis approach ”, Applied Economics , Vol. 45 No. 24 , pp. 3473 - 3482 .

Chen , H. and Rahman , I. ( 2018 ), “ Cultural tourism: an analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty ”, Tourism Management Perspectives , Vol. 26 , pp. 153 - 163 .

Cho , V. ( 2010 ), “ A study of non-economic determinants in tourism demand ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 12 No. 4 , pp. 307 - 320 .

Cohen , E.H. ( 2011 ), “ Educational dark tourism at an in populo site: the holocaust museum in Jerusalem ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 38 No. 1 , pp. 193 - 209 .

Crouch , G.I. and Ritchie , J.R.B. ( 1999 ), “ Tourism, competitiveness and societal prosperity ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 44 No. 3 , pp. 137 - 152 .

Cuccia , T. and Rizzo , I. ( 2011 ), “ Tourism seasonality in cultural destinations: empirical evidence from Sicily ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 32 No. 3 , pp. 589 - 595 .

Cuccia , T. , Guccio , C. and Rizzo , I. ( 2016 ), “ The effects of UNESCO world heritage list inscription on tourism destinations performance in Italian regions ”, Economic Modelling , Vol. 53 , pp. 494 - 508 .

Di Lascio , F.M. , Giannerini , S. , Scorcu , A.E. and Candela , G. ( 2011 ), “ Cultural tourism and temporary art exhibitions in Italy: a panel data analysis ”, Statistical Methods and Applications , Vol. 20 , pp. 519 - 542 .

Dogru , T. , Sirakaya-Turk , E. and Crouch , G.I. ( 2017 ), “ Remodeling international tourism demand: old theory and new evidence ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 60 , pp. 47 - 55 .

Du Rand , G.E. , Heath , E. and Alberts , N. ( 2003 ), “ The role of local and regional food in destination marketing ”, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing , Vol. 14 Nos 3/4 , pp. 97 - 112 .

Dwyer , L. , Mellor , R. , Livaic , Z. , Edwards , D. and Kim , C. ( 2004 ), “ Attributes of destination competitiveness: a factor analysis ”, Tourism Analysis , Vol. 9 Nos 1/2 , pp. 91 - 101 .

European Commission ( 2017 ), “ Annex C: the culture and creative cities monitor ”, available at: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/cultural-creative-cities-monitor/downloads ( accessed 22 March 2019 ).

European Union ( 2017 ), The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor 2017 Edition , European Union , Luxembourg .

European Union ( 2018a ), “ Annex A: the culture and creative cities monitor methodology in ten steps ”, available at: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/cultural-creative-cities-monitor/downloads ( accessed 22 March 2019 ).

European Union ( 2018b ), “ Annex B: statistical assessment of the cultural and creative cities index 2017 ”, available at: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/cultural-creative-cities-monitor/docs-and-data ( accessed 24 November 2021 ).

Falk , M. ( 2010 ), “ A dynamic panel data analysis of snow depth and winter tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 31 No. 6 , pp. 912 - 924 .

Falk , M. ( 2013 ), “ Impact of long-term weather on domestic and foreign winter tourism demand ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 17 .