An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Schedules for home visits in the early postpartum period

Maternal complications including psychological and mental health problems and neonatal morbidity have been commonly observed in the postpartum period. Home visits by health professionals or lay supporters in the weeks following the birth may prevent health problems from becoming chronic with long‐term effects on women, their babies, and their families.

To assess outcomes for women and babies of different home‐visiting schedules during the early postpartum period. The review focuses on the frequency of home visits, the duration (when visits ended) and intensity, and on different types of home‐visiting interventions.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (28 January 2013) and reference lists of retrieved articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including cluster‐RCTs) comparing different types of home‐visiting interventions enrolling participants in the early postpartum period (up to 42 days after birth). We excluded studies in which women were enrolled and received an intervention during the antenatal period (even if the intervention continued into the postnatal period) and studies recruiting only women from specific high‐risk groups. (e.g. women with alcohol or drug problems).

Data collection and analysis

Study eligibility was assessed by at least two review authors. Data extraction and assessment of risk of bias were carried out independently by at least two review authors. Data were entered into Review Manager software.

Main results

We included data from 12 randomised trials with data for more than 11,000 women. The trials were carried out in countries across the world, and in both high‐ and low‐resource settings. In low‐resource settings women receiving usual care may have received no additional postnatal care after early hospital discharge.

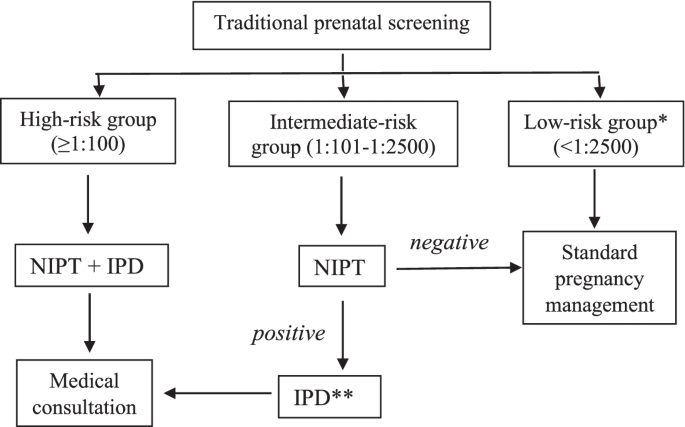

The interventions and control conditions varied considerably across studies with trials focusing on three broad types of comparisons: schedules involving more versus fewer postnatal home visits (five studies), schedules involving different models of care (three studies), and home versus hospital clinic postnatal check‐ups (four studies). In all but two of the included studies, postnatal care at home was delivered by healthcare professionals. The aim of all interventions was broadly to assess the wellbeing of mothers and babies, and to provide education and support, although some interventions had more specific aims such as to encourage breastfeeding, or to provide practical support.

For most of our outcomes only one or two studies provided data, and overall results were inconsistent.

There was no evidence that home visits were associated with improvements in maternal and neonatal mortality, and no consistent evidence that more postnatal visits at home were associated with improvements in maternal health. More intensive schedules of home visits did not appear to improve maternal psychological health and results from two studies suggested that women receiving more visits had higher mean depression scores. The reason for this finding was not clear. In a cluster randomised trial comparing usual care with individualised care by midwives extended up to three months after the birth, the proportions of women with Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) scores ≥ 13 at four months was reduced in the individualised care group (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.86). There was some evidence that postnatal care at home may reduce infant health service utilisation in the weeks following the birth, and that more home visits may encourage more women to exclusively breastfeed their babies. There was some evidence that home visits are associated with increased maternal satisfaction with postnatal care.

Authors' conclusions

Increasing the number of postnatal home visits may promote infant health and maternal satisfaction and more individualised care may improve outcomes for women, although overall findings in different studies were not consistent. The frequency, timing, duration and intensity of such postnatal care visits should be based upon local and individual needs. Further well designed RCTs evaluating this complex intervention will be required to formulate the optimal package.

Plain language summary

Home visits in the early period after the birth of a baby

Health problems for mothers and babies commonly occur or become apparent in the weeks following the birth. For the mothers these include postpartum haemorrhage, fever and infection, abdominal and back pain, abnormal discharge, thromboembolism, and urinary tract complications, as well as psychological and mental health problems such as postnatal depression. Mothers may also need support to establish breastfeeding. Babies are at risk of death related to infections, asphyxia, and preterm birth. Home visits by health professionals or lay supporters in the early postpartum period may prevent health problems from becoming long‐term, with effects on women, their babies, and their families. This review looked at different home‐visiting schedules in the weeks following the birth.

We included 12 randomised trials with data for more than 11,000 women. Some trials focused on physical checks of the mother and newborn, while others provided support for breastfeeding, and one included the provision of practical support with housework and childcare. They were carried out in both high‐resource countries and low‐resource settings where women receiving usual care may not have received additional postnatal care after early hospital discharge.

The trials focused on three broad types of comparisons: schedules involving more versus less postnatal home visits (five studies), schedules involving different models of care (three studies), and home versus hospital clinic postnatal check‐ups (four studies). In all but two of the included studies postnatal care at home was delivered by healthcare professionals. For most of our outcomes only one or two studies provided data and overall results were inconsistent.

There was no evidence that home visits were associated with reduced newborn deaths or serious health problems for the mothers. Women's physical and psychological health were not improved with more intensive schedules of home visits although more individualised care improved women's mental health in one study. Overall, babies were less likely to have emergency medical care if their mothers received more postnatal home visits. More home visits may have encouraged more women to exclusively breastfeed their babies. The different outcomes reported in different studies, how the outcomes were measured, and the considerable variation in the interventions and control conditions across studies were limitations of this review. The studies were of mixed quality as regards risk of bias.

More research is needed before any particular schedule of postnatal care can be recommended

Description of the condition

The postpartum period, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the period from childbirth to the 42nd day following delivery ( WHO 2005 ), is critical for both mothers and newborns. An estimated 529,000 maternal deaths occur worldwide each year because of pregnancy‐related complications in the antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum periods, especially in resource‐limited settings ( WHO 2005 ).These deaths are often sudden and unpredictable, with 11% to 17% occurring during childbirth itself and 50% to 71% occurring during the postpartum period ( WHO 2005 ). Maternal health problems commonly observed in the postpartum period include postpartum haemorrhage, fever, abdominal and back pain, abnormal discharge, puerperal genital infection, thromboembolic disease, and urinary tract complications ( Bashour 2008 ), as well as psychological and mental health problems such as postnatal depression. The postpartum period is also critical for newborns. Every year approximately 3.7 million babies die in the first four weeks of life. Most of these infants are born in developing countries and most die at home. Nearly 40% of all deaths of children younger than five years old occur within the first 28 days of life (neonatal or newborn period). Just three causes—infections, asphyxia, and preterm birth—account for nearly 80% of these deaths ( WHO/UNICEF 2009 ). Moreover, the postpartum period is a time of transition for women and their families, who are adjusting on physical, psychological, and social levels ( Shaw 2006 ). In most developed countries, postpartum hospital stays are often shorter than 48 hours following a vaginal birth; thus most postpartum care is provided in community and ambulatory‐care settings. Early intervention in the postpartum period may prevent health problems from becoming chronic with long‐term effects on women, their babies, and their families.

Description of the intervention

The purpose of a home‐visiting program is to provide support at home for mothers, babies, and families by health professionals or skilled attendants. However, a single clearly defined methodology for this intervention does not exist. Further, the term "home visiting" is used differently in various contexts ( AAP 2009 ). Since the 1970s, the length of hospital stay after childbirth has fallen dramatically in many high‐resource settings. Early postnatal discharge of healthy mothers and term infants does not appear to have adverse effects on breastfeeding or maternal depression when women are offered at least one nurse‐midwife home visit after discharge ( Brown 2002 ). Home‐visiting programs provide breastfeeding and hygiene education, parenting and child health instruction, and general support to families, successfully addressing many of the barriers to access including transportation issues, initiation of timely care, and completeness of services ( AAP 1998 ; AAP 2009 ). Several trials have assessed the impact of home‐visiting programs, especially effects on child abuse and neglect in vulnerable families ( Donovan 2007 ; Olds 1997 ; Quinlivan 2003 ). Others focused on the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of intensive home‐visiting programs ( Barlow 2006 ; Carabin 2005 ; McIntosh 2009 ). Some home‐visiting programs have specifically targeted high risk groups such as women suffering domestic abuse (intimate partner violence) or families that are economically or socially disadvantaged. Home‐visiting programs for high risk groups or those by child health nurses may include components during pregnancy and may continue over many months or years; such programs are outside the scope of this review and have been addressed in other Cochrane reviews ( Bennett 2008 ; Jahanfar 2013 ; Macdonald 2008 ; Turnbull 2012 ). In this review we focus on the early postnatal period following discharge from hospital.

In 2009, WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund recommended home visits by a skilled attendant in resource‐limited settings. In high‐mortality settings and where access to facility‐based care is limited, at least two home visits are recommended for all home births: the first visit should occur within 24 hours of the birth, the second visit on day three, and if possible, a third visit should be made before the end of the first week of life (day seven). For babies born in a healthcare facility, the first home visit was recommended to be made as soon as possible after the mother and baby return home with remaining visits following the same schedule as for home births ( WHO/UNICEF 2009 ).

A recent review demonstrated the effectiveness of community‐based intervention packages in improving neonatal outcomes and reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in resource‐limited settings; home visiting is the one of the main components in each of these intervention packages. This review offers encouraging evidence of the value of integrating maternal and newborn care in community settings ( Lassi 2010 ). We, therefore, did not include intervention packages of continuous care with components of antenatal or hospital care in our review.

How the intervention might work

In high‐resource settings healthy women and babies are frequently discharged from hospital within one or two days of the birth, and in low‐resource settings women may be discharged within hours of the birth or give birth at home ( Brown 2002 ). Potentially, home visits in the first few days of the birth by healthcare professions or trained support workers offer opportunities for assessment of the mother and newborn, health education, infant feeding support, emotional or practical support and, if necessary, referral to other health professionals or agencies ( Carabin 2005 ; Donovan 2007 ; Lassi 2010 ; Shaw 2006 ). Postpartum visits may prevent health problems developing or reduce their impact by early intervention or referral. Home visits have improved coverage of key maternal and newborn care practices such as early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding, skin‐to‐skin contact, delayed bathing, attention to hygiene (e.g. hand washing and water quality), umbilical cord care, infant skin care. In addition, home visits may identify conditions that require additional care or check‐up, as well as counselling regarding when to take the mother and newborn to a healthcare facility ( WHO/UNICEF 2009 ). Home visits may involve not only the assessment of the mother and newborn for physical problems but also assessment of maternal mental health, family circumstances and the home environment.

Depending on the context, home visits may take a non‐judgmental and supportive role or a more directive approach in which the goals are to monitor family compliance with standards of parenting care and ensure the newborn's health and welfare.The type of approach used can influence the ability of the carers to engage mothers and newborns, resulting in acceptance or rejection of the help offered and potential for further disengagement ( Doggett 2005 ).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite many studies and reviews, evidence regarding the effectiveness of different types of home‐visiting programs in the early postnatal period is not sufficient. In some contexts once women have been discharged from hospital there may be no, or very limited postnatal follow‐up. In higher‐resource settings once women are at home, services may be provided by a range of health and social care agencies (newborn health visitors, social workers, paediatricians and general practitioners) and may be fragmented; postnatal home visits potentially allow continuity of care after hospital discharge and for the assessment and referral of the mother and newborn.

This review addresses the following questions: do different schedules of postpartum home‐visiting programs reduce maternal/neonatal mortality and morbidities, and if they do, what is the optimal schedule for postpartum home visits? This review includes reports evaluating the frequency, timing, duration and intensity of home visits.The optimal schedule has been set out by WHO/UNICEF 2009 , however, there was no clear evidence underpinning recommendations.

The primary objective of this review is to assess outcomes (maternal and newborn mortality) of different home‐visiting schedules during the early postpartum period. The review focuses on the frequency of home visits (how many home visits altogether), the timing (when visits started, e.g. within 48 hours of the birth), duration (when visits ended), intensity (how many visits per week), and different types of home‐visiting interventions.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies.

We included studies that compared outcomes after home visits with outcomes of no home visits or different types of home‐visiting interventions; studies that used random or quasi‐random allocations of participants; and those in which the unit of allocation was the individual or group (cluster‐randomised). We also planned to include studies available only as abstracts, noting that these studies were awaiting assessment, pending publication of the full report. There was, however, no such study identified.

Types of participants

Eligible studies were ones that enrolled participants in the early postpartum period (up to 42 days after birth). We excluded studies in which women were enrolled and received an intervention during the antenatal period, even those in which the intervention continued into the postnatal period.

We planned to exclude studies that only recruited women from specific high‐risk groups (e.g. women identified with alcohol or drug problems) as interventions to support such women have been addressed elsewhere ( Turnbull 2012 ).

Types of interventions

Interventions included scheduled home visiting in the postpartum period (excluding studies with antenatal home visiting in which the visits continued over many months). Interventions were home visits with various frequency, timings, duration and intensity.

We planned to include studies with co‐intervention(s). Home visits may include outreach visits to non‐healthcare facilities. Trials including a group that did not receive home visits would have been eligible but would have been analysed separately.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes.

- Maternal mortality at 42 days post birth.

- Neonatal mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes.

- Maternal morbidities (postpartum haemorrhage, puerperal fever, abdominal and back pain, abnormal discharge, puerperal genital infection, thromboembolic disease, and urinary tract complications) within 42 days after birth.

- Maternal mental health (depression, anxiety) and related problems (intimate partner violence, drug use) at 42 days after birth.

- Satisfaction with overall care and service at 42 days after birth.

Neonatal outcomes

- Neonatal morbidities (pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhoea, septic meningitis, encephalopathy or cerebral injury, and jaundice) within 28 days after birth.

- Established feeding regimen (e.g. exclusive breastfeeding) at 28 days after birth.

- Incomplete immunisation.

- Failure to thrive, abuse, neglect, domestic violence from parents for any reason within 28 days after birth.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches.

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (28 January 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

- monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

- weekly searches of MEDLINE;

- weekly searches of Embase;

- handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

- weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

(1) references from published studies.

We searched the reference lists of relevant trials and reviews identified.

(2) Unpublished literature

We planned to contact the authors for more details about the published trials/ongoing trials.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NY and SN) independently assessed eligibility for inclusion for all studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved discrepancies by discussion and by consulting a third review author (RM).

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors (NY and SN) extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We entered data into the Review Manager (RevMan) software ( RevMan 2012 ) and checked for accuracy.

If information regarding any of the above had been unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (TD and NY) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Higgins 2011 ). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving an additional assessor (RM).

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

- low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

- high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

- unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

- low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

- high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

- unclear risk of bias.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance and detection bias)

Blinding study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received is generally not feasible for this type of intervention. It may however, be possible to blind outcome assessment. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias for detection bias if outcome assessors were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

- low, high or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses. We were not, however, able to re‐include data, as the data were not available. We assessed methods as:

- low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

- high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

- unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

- low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review were reported);

- high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes were reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

- low risk of other bias;

- high risk of other bias;

- unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Higgins 2011 ). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis .

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data.

For dichotomous and categorical data, we used risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and used the summary RR to combine trials that measured the same outcome. We had also planned to use the risk difference (RD).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. If required, we would have used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials.

We included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. When including cluster trials, we adjusted their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Higgins 2011 ) using an estimate of the intra cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial, from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. Where we used ICCs from other sources, we reported this and planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. We identified both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, and we synthesised the relevant information provided there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

Trials with multiple treatment arms

One trial with three arms has been included in this review as two separate studies ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ); to avoid double counting, the control group data (events and sample) were shared between the two study comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition as:

- low risk of bias (indicates no or low level of missing data on intention‐to‐treat basis);

- high risk of bias (indicates high level of missing data);

We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using Sensitivity analysis .

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the T², I² and Chi² statistics to examine heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis.

We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we had identified substantial heterogeneity, we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Had there been 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we planned to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We planned to assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry was suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate it. In this version of the review, too few trials contributed data to allow us to carry out this planned analyses.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the RevMan software ( RevMan 2012 ). We used a fixed‐effect model for combining data where trials examined the same intervention, and the trials' populations and interventions were judged sufficiently similar. When there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or when substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. When the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. If we had identified heterogeneity for different types of study designs, we planned to carry out separate meta‐analysis by type of studies (individually‐randomised trial, cluster‐randomised trial).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform a subgroup analysis according to the following clinically logical predefined groups.

- Initiation of the intervention (within 48 hours after birth or later).

- Duration of the intervention (< three weeks or ≥ three weeks).

- Intensity or frequency of the intervention (< one visit/week versus ≥ one visit/week.).

- Person doing the visit: medical professional versus skilled attendant.

- Parity: primiparity versus multiparity.

However, interventions in included trials were too heterogeneous to conduct subgroup analyses planned as above, and we therefore decided to conduct subgroup analyses by intensity/frequency of the intervention only in the comparison of more versus fewer home visits as below.

- Any number of home visits versus no home visit.

- Four or more home visits versus fewer than four visits.

- More home visits versus fewer home visits (both groups had more than four visits).

We planned subgroup analyses on both the primary and secondary outcomes.

For post hoc analyses, we considered a 99% CI excluding a zero treatment effect as statistically significant.

Also, when we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and where it was, used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We assessed differences between subgroups using interaction tests available in RevMan 2012 .

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality on the primary analysis and primary outcomes.

We planned to explore any risk of bias associated with a particular aspect of study quality (e.g. high risk of bias for allocation concealment) by sensitivity analyses.

Where we included cluster‐randomised trials, we planned to carry out sensitivity analysis using a range of values for intra class correlation coefficients.

Description of studies

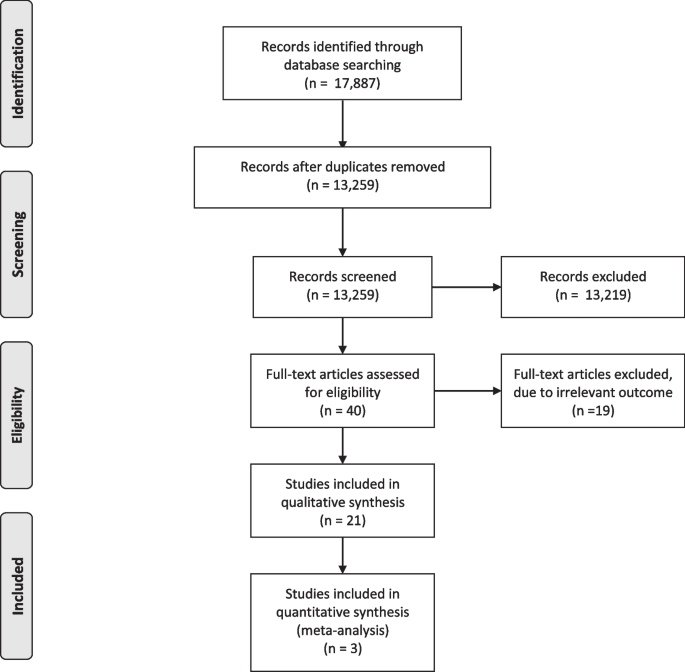

Results of the search.

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register identified 21 reports, and our additional searches of reference lists identified eight reports. Some studies resulted in multiple publications and one duplicate report. The 28 unique reports equated to 24 separate studies. After assessing eligibility we included 12 studies (one trial with three arms has been reported in this review as two separate studies ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b )). We excluded 10 studies. Two reports are awaiting further assessment pending translation from the original Spanish ( Furnieles‐Paterna 2011 ; Salazar 2011 ) and more information about these trials is set out in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables.

Included studies

After assessing eligibility we included 12 randomised trials with a total of 11,287 women.

Three of the trials ( Christie 2011 ; Kronborg 2007 ; MacArthur 2002 ) were cluster‐randomised and health centres or healthcare staff were the units of randomisation. For these trials event rates and, or sample sizes have been adjusted in the analysis to take account of cluster design effect.

One of the trials included three arms; women in the intervention groups received either four or one home visits, while the control group received no visits. In order for us to set out the results for all three groups we have reported this trial as though it was two studies ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ). In the Data and analyses , women receiving four visits versus no visits are entered under Bashour 2008a ; whereas one versus no visits are compared in Bashour 2008b . The events and sample number for the control group have been divided between these comparisons to avoid double counting.

Results of trials were published between 1998 and 2012 although study data may have been collected some years before publication (e.g. in Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 women were recruited between 1989 and 1992).

The studies were carried out in countries across the globe in both high‐ and low‐resource settings. Three studies were carried out the USA ( Escobar 2001 ; Lieu 2000 ; Paul 2012 ), three in the UK ( Christie 2011 ; MacArthur 2002 ; Morrell 2000 ), two in Canada ( Gagnon 2002 ; Steel 2003 ), and one each in Turkey ( Aksu 2010 ), Syria ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ), Denmark ( Kronborg 2007 ) and Zambia ( Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 ). It is important to take the time and setting into account when interpreting results as routine practice varied across time and in different settings; for example, in the UK usual care may have involved up to seven home visits, whereas in other settings there may have been no postnatal care after hospital discharge.

The number and type of visits examined varied considerably across these trials, and control conditions also varied. Broadly, trials examined three types of comparisons: schedules involving more versus less postnatal home visits; schedules involving different models of care; and home versus hospital clinic postnatal follow‐up. In view of the complexity of interventions we have set out the main components of interventions and a description of control conditions in Table 4 .

1. Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits

In five of our included studies the main comparison was between women receiving more versus fewer home visits in the postnatal period.

Aksu 2010 examined the effect of one postnatal visit by a trained supporter versus no postnatal visits; Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b compared four or one postnatal home visits from midwives versus no home visits following hospital discharge. Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 compared four versus one midwife home visits. In these three studies, carried out in low‐resource settings, women may have received no additional postnatal care.

In contrast, Christie 2011 and Morrell 2000 examined the impact of additional care in settings where women already received more than four postnatal visits from midwives as part of usual care. Christie 2011 compared groups receiving six versus one health visitor visits (in addition to midwifery care) and Morrell 2000 examined the impact of up to 10 visits from lay supporters; again visits were provided in addition to routine midwifery care which was available to women in both intervention and control groups. (In the data and analysis tables we have separated studies where women in both groups received more than four home visits as the impact of interventions is likely to be different from that in settings where women received no, or very limited postnatal care.)

2. Schedules comparing different models of postnatal care

Three studies examined different ways of providing postnatal care.

Steel 2003 compared the effects of two visits by public health nurses in the early postnatal period compared with a telephone screening interview with discretionary nurse home visits.

In a cluster‐randomised trial Kronborg 2007 looked at the effects of more structured postnatal visits; women in the intervention group were visited between one and three times by health visitors who had attended special training on promoting and supporting breastfeeding. Women in the control group received usual care by health visitors who had not attended the breastfeeding courses.

MacArthur 2002 compared postnatal care that was adapted to the individual needs of women and home visits extended beyond the usual period of care (flexible visits up to 10 to 12 weeks postpartum). This was compared with usual care which involved a more rigid schedule of midwife home visits confined to the early postnatal period.

3. Home versus hospital postnatal care

Four of the included studies compared outcomes in women attending hospital clinics for postnatal checks and follow‐up (usual care) versus home visits by nurses ( Escobar 2001 ; Gagnon 2002 ; Lieu 2000 ; Paul 2012 ).

For all types of comparisons the purpose of visits was broadly similar: to assess the physical health and wellbeing of mothers and babies (with referral for further care where necessary), to promote and support breastfeeding, to assess maternal emotional wellbeing and to offer health education and support. In some cases the intervention focused on a particular aspect of care (e.g. breastfeeding), whereas other interventions were more general.

The outcomes measured in different studies varied. Most studies included some measure of maternal and infant health (although the particular outcomes measured, the way they were measured, and the time of follow‐up varied considerably between studies). Health service utilisation was also reported in a number of trials. Maternal emotional wellbeing and rates of breastfeeding were reported in some of the studies, and a minority reported maternal satisfaction with postnatal care. In the data and analyses tables we have set up analyses for all prespecified outcomes even where no studies have reported results. We did this in order to illustrate gaps in the evidence, and so that empty tables can be populated in updates of the review as more data become available.

Excluded studies

Ten studies identified by the searches were excluded after assessing the full trial reports. Two trials were excluded as they focused on outcomes in women following early hospital discharge after the birth rather than on different schedules of home visits for women discharged at the same time ( Boulvain 2004 ; Carty 1990 ). Two studies did not specifically examine postnatal home visits ( Gunn 1998 ; Simons 2001 ). One study, which recruited high‐risk women, involved intervention by child health nurses, rather than more general care of the mother and baby in the early postnatal period ( Izzo 2005 ). Quinlivan 2003 also focused on a high‐risk group rather than on the impact of different schedules of care. Three excluded studies examined complex interventions that included components delivered during the antenatal period ( Korfmacher 1999 ; Lumley 2006 ; Olds 2002 ). Finally, Stanwick 1982 was excluded for methodological reasons; there were major protocol deviations in this study, with many women in the intervention group failing to receive the intervention as planned, and analysis was carried out according to treatment received rather than by randomisation group (data were not available to allow us to restore women to their original randomisation group).

Risk of bias in included studies

The included studies were of mixed methodological quality; we were unable to carry out planned sensitivity analysis (temporarily excluding studies at high or unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment) as too few studies contributed data to allow any meaningful additional analysis.

Ten of the 12 included studies used methods to generate the randomisation sequence that we judged were at low risk of bias: seven used computer‐generated sequences or external trial randomisation services ( Aksu 2010 ; Escobar 2001 ; Gagnon 2002 ; Kronborg 2007 ; Lieu 2000 ; MacArthur 2002 ; Paul 2012 ) and three used random number tables ( Christie 2011 ; Morrell 2000 ; Steel 2003 ). In the Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b trial, it was not clear how the randomisation sequence was decided, and the method used by Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 was assessed as being at high risk of bias.

Concealment of group allocation at the point of randomisation was assessed as being at low risk of bias in nine of the studies; five trials reported using sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes to conceal allocation ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ; Escobar 2001 ; Lieu 2000 ; Morrell 2000 ; Steel 2003 ) and four used external randomisation services ( Christie 2011 ; Gagnon 2002 ; Kronborg 2007 ; MacArthur 2002 ). In the trials by Aksu 2010 , Paul 2012 , and Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 the methods used to conceal allocation were not described, or were not clear.

Blinding women and care providers to this type of intervention is not generally feasible and no attempts to achieve blinding for these groups were described. All studies were judged to be at high risk of bias for this domain. It is possible that lack of blinding may have been an important source of bias.

In seven of the trials it was reported that outcome assessors were blind to group allocation ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ; Escobar 2001 ; Gagnon 2002 ; Lieu 2000 ; MacArthur 2002 ; Paul 2012 ; Steel 2003 ). However, where outcome data were assessed by interview, women may have revealed their treatment group and it was not clear whether or not blinding was successful; none of the trialists reported checking the success of blinding. Blinding of outcome assessors was either not attempted or not mentioned in the remaining five trials ( Aksu 2010 ; Christie 2011 ; Kronborg 2007 ; Morrell 2000 ; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 ).

Incomplete outcome data

In six of the included trials sample attrition and missing data did not appear to be important sources of bias (assessed as low or unclear risk of bias) ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ; Christie 2011 ; Escobar 2001 ; Lieu 2000 ; Paul 2012 ; Steel 2003 ). In some trials, although attrition was balanced across groups there was more than 10% loss to follow‐up; in the Aksu 2010 trial the response rate at four months postpartum was 82%; 16% were lost to follow‐up in the Kronborg 2007 study and 15% in the trials by Gagnon 2002 and Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 . By four months postpartum more than 20% of the sample were lost to follow‐up in the MacArthur 2002 trial. Loss to follow‐up was not balanced in the intervention and control groups in the Morrell 2000 study; while the response rate was 83% for those women receiving additional postnatal visits it was only 75% in the control group.

Selective reporting

Assessing selective reporting bias is not easy without access to study protocols, and for all studies included in the review, risk of bias was assessed from published study reports. In most, but not all of the studies the primary outcomes were specified in the methods section and trialists reported results for these outcomes. We were unable to carry out planned investigation of possible publication bias by generating funnel plots as too few studies contributed data.

Other potential sources of bias

In most of the studies there were no other obvious sources of bias. In four of the trials there was some imbalance between groups at baseline ( Escobar 2001 ; Gagnon 2002 ; Lieu 2000 ; Morrell 2000 ). In the cluster trial reported by Christie 2011 , health visitors were the unit of randomisation and it appeared that there were differences between health visitors in terms of the number of women recruited to the trial and in their practices; the impact of these differences in individual practices is unclear. In the Steel 2003 study women were recruited in two study areas and usual practice was different in each area and this led to protocol deviations; again, it is not clear how this would affect results. Finally, in the Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 trial much of the analysis related to the intervention group only, in addition, the nature of the intervention may have affected findings. Midwives asked women about their health as part of the intervention so women in the intervention group were asked repeatedly to identify health problems, whereas women in the control group were only asked as part of follow‐up assessments; this may have affected recall and introduced a risk of response bias.This trial may also have had the potential for publication bias because the publication date was more than six years after study completion.

We have set out the 'Risk of bias' assessments for individual studies in Figure 1 and for overall bias across all studies for different bias domains in Figure 2 .

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Comparison 1: schedules involving more versus fewer home visits (five trials with 2102 women).

In five included studies the main comparison was between women receiving more versus less home visits in the postnatal period ( Aksu 2010 ; Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ; Christie 2011 ; Morrell 2000 ; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 ). One trial included three arms and to allow us to report findings for two different intervention groups this trial has been treated as two separate studies in this review ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ). One of the trials ( Christie 2011 ) was a cluster‐randomised trial and in the data and analyses tables we have used the effective sample size and event rates (adjusted for cluster design effect).

Aksu 2010 examined the effect of one postnatal visit versus no postnatal visits; Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b four or one home visits versus none; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 four versus one home visits. Christie 2011 and Morrell 2000 examined the impact of additional care in settings where women already received more than four visits as part of usual care. Christie 2011 compared groups receiving six versus one health visitor visits (in addition to midwifery care) and Morrell 2000 up to 10 lay supporter visits versus no additional visits with routine midwifery care available to women in both intervention and control groups. (In the data and analysis tables we have separated studies where women in both groups received more than four home visits.)

For many of our prespecified outcomes only one or two studies contributed data and results were not always available for all women randomised. For each result we have specified the number of studies and women for whom data were available (for cluster‐randomised trials these are the adjusted figures). We anticipated that the treatment effect might differ in trials comparing different numbers of visits, we therefore used a random‐effects model for all analyses in this comparison.

Maternal mortality up to 42 days postpartum

Only one trial reported this outcome ( Christie 2011 ). There was no evidence of differences in maternal mortality between groups receiving additional health visitor visits compared with controls, with only one death in 951 women (risk ratio (RR) 2.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 60.14, one study with 951 women) ( Analysis 1.1 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 1 Maternal mortality within 42 days post birth.

Neonatal mortality

Two trials reported on neonatal death ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 ); there was no strong evidence that more visits were associated with fewer deaths. Pooled results showed no evidence of differences between intervention and control groups (average RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.69, two studies, 1281 women), similarly women receiving four or one visits versus none, or four visits versus one had similar numbers of neonatal deaths (RR 3.06, 95% CI 0.37 to 25.39, one study, 873 women; and, RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.60, one study, 408 women, respectively) ( Analysis 1.2 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 2 Neonatal mortality.

Severe maternal morbidity

Two studies reported this outcome, Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b reported the number of women seeking medical help for a health problem and Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 the number of women where a doctor had identified a problem up to 42 days. The numbers of women with problems were very similar in intervention and control groups and there was no evidence of differences between groups either overall, or for women receiving different patterns of visits (overall RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.15, two studies, 1228 women; four or one visits versus none RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.17, one study, 876 women; and, four visits versus one RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.54, one study, 352 women) ( Analysis 1.3 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 3 Severe maternal morbidity.

Maternal health problems up to 42 days

Only one study reported results for most of our pre‐specified outcomes relating to maternal postpartum health problems up to 42 days after the birth ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ). There was no evidence of differences between women receiving four or one postnatal home visits versus none for secondary postpartum haemorrhage (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.26); abdominal pain (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.34); back pain (RR 0.96, 95% 0.83 to 1.11); urinary tract complications (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.10); fever (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.82) or dyspareunia (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.55). No studies reported on thromboembolic disease or puerperal genital tract infections.

One study reported mean scores on a scale measuring maternal perceptions of their general health at six weeks postpartum ( Morrell 2000 ). There was no strong evidence of differences between women receiving additional postnatal support and controls (mean difference (MD) ‐1.60, 95% CI ‐4.72 to 1.52) ( Analysis 1.12 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 12 Maternal perception of general health at 6 weeks (mean SF36).

Postnatal depression and anxiety

None of the studies included in this comparison reported the number of women with a diagnosis of depression in the postnatal period. Two studies looked at mean scores on the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) at six weeks ( Morrell 2000 ) and eight weeks postpartum ( Christie 2011 ). In the Morrell 2000 study women received additional support from lay people, and in Christie 2011 , women received additional health visitor support as well as routine midwife home visits. The intervention did not appear to have a positive effect in either study, and overall, women receiving the additional visits had slightly higher mean depression scores (MD 1.05, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.82) ( Analysis 1.14 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 14 Mean postnatal depression score (last assessment up to 42 days postpartum).

Christie 2011 reported mean anxiety scores at eight weeks postpartum; there was no strong evidence of a difference between groups (MD 3.80, 95% CI ‐0.44 to 8.04) ( Analysis 1.16 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 16 Mean maternal anxiety score (last assessment up to 42 days postpartum).

Maternal satisfaction with care in the postnatal period

Women were asked about their satisfaction with postnatal care in two studies. In one study the number of women saying they were "happy" with their postnatal experience was reported ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b ) ( Analysis 1.17 ). Women receiving no formal postnatal care were slightly more satisfied with their experience, but there was no evidence of difference between groups, and in all groups most women reported satisfaction (RR 0.96, 0.90 to 1.02). In a second study ( Christie 2011 ), the additional support provided by health visitors was associated with increased mean satisfaction scores (MD 14.70, 95% CI 8.32 to 21.08) ( Analysis 1.18 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 17 Maternal satisfaction with postnatal care.

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 18 Mean satisfaction score with postnatal care.

Infant outcomes

Neonatal health service use.

Three studies reported the number of babies requiring urgent health care during the postnatal period although the way this outcome was defined varied in the three studies ( Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b reported hospital visits up to four months; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 doctor‐identified infant health problem at six weeks; and Christie 2011 use of emergency medical services up to eight weeks). Overall, babies were less likely to have emergency medical care if their mothers received more postnatal home visits (average RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.95, three studies with 1370 infants) ( Analysis 1.19 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 19 Serious neonatal morbidity up to 6 months.

Breastfeeding

Exclusive breastfeeding at up to six weeks was reported in three studies. Women receiving additional support at home were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding their babies at six weeks postpartum, and at the last assessment up to six months postpartum (average RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.36, three studies 960 women, and, average RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.73, three studies 1309 women respectively) ( Analysis 1.20 ; Analysis 1.21 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 20 Exclusive breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 weeks).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 21 Exclusive breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 months).

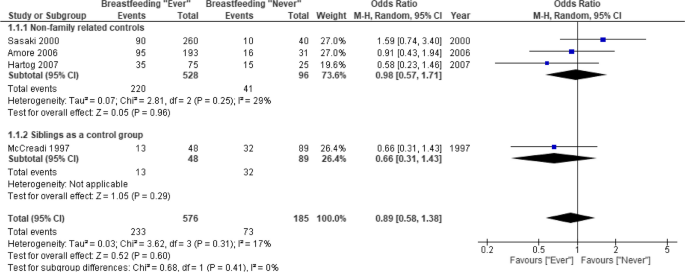

For any breastfeeding there was no evidence of differences between women receiving additional postnatal visits and controls at either six weeks or up to six months postpartum (average RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.38, two studies 813 women, and, average RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.03, two studies 1315 women, respectively) ( Analysis 1.22 ; Analysis 1.23 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 22 Any breastfeeding (up to 6 weeks).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 23 Any breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 months).

Aksu 2010 reported mean duration of breastfeeding (months) in 54 women who had received one versus no postnatal care at home. In both groups women on average breast fed their babies for approximately a year or more, but the mean duration was increased by three months in women receiving a home visit (MD 3.00, 95% CI 2.33 to 3.67) ( Analysis 1.24 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 24 Mean duration of any breastfeeding (months).

Neonatal morbidity

Two studies reported infant respiratory tract infections up to eight weeks postpartum, although the condition was not defined in the same way in the two trials. In Bashour 2008a ; Bashour 2008b the number of babies suffering a cough or cold was reported, whereas in the Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 trial infants appeared to have more serious illness. Overall, and in individual studies there was no clear evidence of difference between groups (pooled RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.17, two studies 1217 infants) ( Analysis 1.25 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 25 Infant respiratory tract infection within 42 days.

A single study reported on the number of infants with jaundice (not defined); very similar numbers of infants had jaundice in both intervention and control groups (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.26, 861 infants) ( Analysis 1.26 ). In the same study, approximately half of the babies were reported to have had diarrhoea, however, more infants in the group receiving no visits were reported to suffer from diarrhoea compared to those whose mothers received postnatal home visits (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.98, 861 infants) ( Analysis 1.27 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 26 Infant jaundice.

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 27 Infant diarrhoea up to 42 days postpartum.

There were no clear differences between groups in the number of infants receiving immunisations; the vast majority of infants were immunised whether or not their mothers received postnatal care at home (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.01) ( Analysis 1.28 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 28 Infant immunisation took place.

Non‐prespecified outcomes

One study reported on contraceptive use at 42 days postpartum; no clear differences between groups were identified (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.16) ( Analysis 1.29 ).

Comparison 1 Schedules involving more vs fewer postpartum visits, Outcome 29 Non prespecified ‐ Contraceptive use.

Comparison 2: Schedules comparing different models of postnatal care (three studies with 4394 women)

Three studies are included in this comparison; each examined a different type of intervention and control condition and we have not pooled findings in meta‐analyses. In brief, Steel 2003 compared two home visits compared with a telephone screening interview with discretionary nurse home visits. In Kronborg 2007 , health visitors (HVs) were randomised, and women were visited between one and three times by HVs who had attended special training on supporting breastfeeding compared with usual care by HVs who had been specially trained. MacArthur 2002 compared individualised postnatal care up to 10 to 12 weeks postpartum with usual care, which involved a more rigid schedule of midwife home visits in the early postnatal period.

For most of our prespecified outcomes no data were reported in any of the three trials.

None of the studies reported on maternal mortality.

In the study by MacArthur 2002 there were only three neonatal deaths from a sample of 2064 women, and no significant differences between treatment groups were identified.

None of the studies reported on maternal general morbidity although MacArthur 2002 reported on the number of women with EPDS scores greater than 12 (the cut‐off used to denote high risk of postnatal depression) at four months postpartum. Women receiving individualised extended postnatal care were less likely to have EPDS scores ≥ 13 compared with women receiving routine care (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.86) ( Analysis 2.9 ).

Comparison 2 Studies comparing different ways of offering postnatal care at home, Outcome 9 Postnatal depression (EPDS ≥ 13 at 4 months postpartum).

Steel 2003 reported the number of babies with health problems up to four weeks; there was no strong evidence of any difference between groups (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.12) ( Analysis 2.15 ).

Comparison 2 Studies comparing different ways of offering postnatal care at home, Outcome 15 Neonatal morbidity up to 28 days.

The cluster‐randomised trial by Kronborg 2007 examined the impact of care from HVs with special training to promote and support breastfeeding. In this study there was no evidence of difference in the number of women who had stopped exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.14) ( Analysis 2.16 ). Few women in either group continued to exclusively breastfeed at six months and there was no evidence of difference between groups identified (RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.69) ( Analysis 2.17 ).

Comparison 2 Studies comparing different ways of offering postnatal care at home, Outcome 16 Stopped exclusive breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 weeks).

Comparison 2 Studies comparing different ways of offering postnatal care at home, Outcome 17 Exclusive breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 months).

In the study comparing home visits versus telephone screening by Steel 2003 most women in both groups were breastfeeding their babies at six weeks postpartum (any breastfeeding) and there was no clear difference between groups (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.08) ( Analysis 2.18 ).

Comparison 2 Studies comparing different ways of offering postnatal care at home, Outcome 18 Any breastfeeding (up to 6 weeks).

None of our other prespecified infant outcomes were reported in any of these studies.

Comparison 3: Home versus hospital postnatal care (four studies with 3917 women)

Four studies compared women attending hospital clinics for postnatal checks (usual care) versus home visits by nurses ( Escobar 2001 ; Gagnon 2002 ; Lieu 2000 ; Paul 2012 ).

None of these studies reported on maternal or neonatal mortality.

Maternal morbidity

All four studies reported on maternal use of emergency health care in the postnatal period although there were some differences in definitions; Escobar 2001 and Lieu 2000 reported on the number of women making an urgent hospital visit up to two weeks, and Paul 2012 the number of women seeking unplanned emergency health care up to two weeks, whereas Gagnon 2002 reported hospital admissions up to eight weeks postpartum. Pooled results from these studies revealed no evidence of differences between women receiving hospital clinic versus home postnatal care (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.26, four studies, 3755 women) ( Analysis 3.3 ).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 3 Severe maternal morbidity.

Maternal anxiety and depression

Two studies reported on the number of women with depressive symptoms at two weeks postpartum; similar numbers of women in the intervention and control groups had symptoms (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.30, two studies with 2177 women) ( Analysis 3.10 ).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 10 Postnatal depression (last assessment up to 42 days postpartum).

Gagnon 2002 reported mean scores on the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) at two weeks. There were no evidence of differences between groups (MD 0.30, 95% CI ‐1.08 to 1.68, 513 women) ( Analysis 3.13 ).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 13 Mean maternal anxiety score (last assessment up to 42 days postpartum).

Data on depression and anxiety were also collected in the Paul 2012 study. However, while the MDs between groups were set out, mean scores for women in the home and hospital groups were not reported and we were unable to enter data from this trial in our data and analyses tables. The authors reported no statistically significant differences in mean EPDS or STAI scores at two weeks, two months and six months postpartum.

Satisfaction with care

In two studies, women seemed to prefer home rather than hospital clinic care; postnatal care was rated as good or excellent by 68% of women in the home care group compared with 55% in the clinic group (unweighted percentages). This difference between groups was statistically significant (there was high heterogeneity for this outcome and we used a random‐effects model; average RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.45) ( Analysis 3.14 ). Gagnon 2002 identified no evidence of difference in mean scores for satisfaction with postnatal care at eight weeks (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.88 to 0.68) ( Analysis 3.15 ).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 14 Maternal satisfaction with postnatal care.

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 15 Mean satisfaction score with postnatal care.

All four studies examined at least one outcome relating to breastfeeding. Gagnon 2002 reported the number of women exclusively breastfeeding at two weeks. There was no strong evidence of differences between groups (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.18) ( Analysis 3.16 ). Escobar 2001 and Lieu 2000 reported the number of women who had discontinued any breastfeeding at two weeks; again, there were no clear differences between groups (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.12) ( Analysis 3.18 ). Paul 2012 examined the number of women breastfeeding at eight weeks postpartum and while slightly more women in the home visit group were still breastfeeding at this time, the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.18) ( Analysis 3.19 ).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 16 Exclusive breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 weeks).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 18 Discontinued breastfeeding (up to 6 weeks).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 19 Any breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 months).

Infant severe morbidity and health care use

All four studies reported on infant use of emergency health care; Escobar 2001 and Lieu 2000 reported on the number of infants re‐hospitalised within two weeks of initial discharge, and Paul 2012 the number of infants requiring unplanned emergency health care up to two weeks. Gagnon 2002 reported infant hospital admissions up to eight weeks postpartum. Pooled results revealed no evidence of differences in infant health service use for women receiving hospital clinic versus home postnatal care (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.43, four studies 3770 infants) ( Analysis 3.21 ).

Comparison 3 Postnatal visit at home vs hospital clinic visit, Outcome 21 Severe infant morbidity up to 6 weeks.

Planned subgroup and sensitivity analysis

For our primary outcomes we had planned subgroup analysis by when visits were initiated, by the duration and intensity of the intervention, by the person carrying out the visit (medical professional versus skilled attendant), by content of the visit, by parity, and by other potential modifying factors (e.g. study in developed versus developing country). However, within each comparison, data for our primary outcomes were scarce. For maternal mortality only one study reported findings and for neonatal mortality, within the different comparisons, at most two studies contributed data. For both of our primary outcomes event rates were low and within studies there were no significant differences between groups, nor was there evidence of heterogeneity between studies where more than one study contributed data. For these reasons, we did not think that in this version of the review subgroup analysis would throw any further light on findings. In future updates of the review, as more data become available we will carry out planned additional analysis.

Similarly, planned sensitivity analysis by risk of bias was not performed; again, too few studies contributed data to any particular analysis to make such additional analyses meaningful.

Summary of main results

In this review we have included data from 12 randomised trials with data for more than 11,000 women. The trials were carried out in countries across the world, and in both high‐ and low‐resource settings. In low‐resource settings, women receiving usual care may have received no additional postnatal care after early hospital discharge.

The interventions and control conditions varied considerably across studies with trials focusing on three broad types of comparisons: schedules involving more versus fewer postnatal home visits (five studies), schedules involving different models of care (three studies), and home versus hospital clinic postnatal check‐ups (four studies). In all but two of the included studies, postnatal care at home was delivered by healthcare professionals. The broad aims of all interventions were to assess the wellbeing of mothers and babies, and to provide education and support, although some interventions had more specific aims such as to encourage breastfeeding or to provide practical support.

In the five studies comparing more versus less postnatal home visits there was no evidence of differences between groups for maternal and neonatal mortality. Only one study (which reported a large number of outcomes overall) reported results for most of our outcomes relating to maternal morbidity, and there was no strong evidence that more postnatal visits at home were associated with improvements in maternal health.

Two studies examining maternal depression compared mean scores on the EPDS and results suggested that women receiving more visits had higher mean scores, denoting an increased risk of depression. The reason for this finding is not clear. It is possible that women who had more contact with healthcare professionals may have been more willing to disclose their feelings. The authors of one trial ( Morrell 2000 ), also speculated that increased provision of support may somehow disrupt women's usual support networks, or that the withdrawal of services may result in increased depression.

Two studies reported on maternal satisfaction with postnatal care and in one of these, additional health visitor support was associated with increased satisfaction scores. There was some evidence that postnatal care at home may reduce infant health service utilisation in the weeks following the birth, and that more home visits may encourage more women to exclusively breastfeed their babies. The evidence regarding any breastfeeding was less clear, although one study with a small sample size suggested that a home visit may encourage women to continue to breastfeed for longer. There was no strong evidence that infant morbidity including jaundice and respiratory tract infections was affected by home visits, although episodes of diarrhoea were reported less often by women in the groups receiving visits in a single study (this study reported a large number of outcomes and as findings were not consistent it is possible that this finding occurred by chance).

For the three studies comparing different ways of offering care involving postnatal home visits it was not clear that interventions had a consistent effect, and many of our prespecified outcomes were not reported. There did not appear to be strong evidence from two studies that experimental interventions increased the number of women breastfeeding their babies. In one study, women in the experimental groups receiving an extended programme of home visits by midwives appeared to have lower EPDS scores at four months postpartum.

Four studies examined home versus hospital clinic postnatal checks. There were no data reported for most of our outcomes. There were no clear differences between groups for maternal emergency healthcare utilisation or maternal anxiety or depression. In two studies women seemed to prefer home rather than hospital care, while a third study examining satisfaction with care did not identify any clear difference between groups. There was no strong evidence that home care was associated with an increase in breastfeeding, or that infant emergency healthcare utilisation differed between groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The studies included in the review examined different sorts of interventions in different types of settings and drawing clear conclusions is not simple. The trials had a variety of aims with some focusing on physical checks of the mother and newborn, while others specifically aimed to provide support for breastfeeding, and one included the provision of more practical support with housework and childcare; under these circumstances it is not surprising that results from studies were not entirely consistent. This variation in aims was reflected in the choice of outcomes reported in different studies, and for most of our outcomes there were very few data. Further, for outcomes such as breastfeeding there were differences in how outcomes were measured and when. Important clinical outcomes relating to maternal and infant health were mainly not reported, and for these outcomes results were dominated by a single study. Perhaps surprisingly, not all of the studies reported maternal satisfaction with different schedules or ways of offering care; those studies that did, provided some evidence that women preferred care at home. Improved maternal satisfaction with care involving home visits may be related to women's increased health awareness, support for behavioural change, and improved access to health‐care services, however, the evidence on maternal views is still limited. There was some evidence from two studies carried out in high‐resource settings that maternal depression scores were increased in women receiving more postnatal visits; the reasons for this finding are not clear, and this finding warrants further research attention in future trials and qualitative research.

Quality of the evidence

The studies included in the review were of mixed quality as regards risk of bias. Most of the studies used methods to generate the randomisation sequence and to conceal allocation at the point of randomisation that we judged were at low risk of bias. On the other hand, blinding women and healthcare staff to this type of intervention is not generally feasible, and in many of the studies the experimental and control interventions may have been delivered by quite different staff. Although in eight of the 12 studies it was stated that outcome assessors were blind to treatment group, many of the data on breastfeeding and maternal depression, for example, were derived from interviews and it is possible that women disclosed their allocation. It is also possible that the interventions themselves led to a response bias; women in the groups receiving more care were asked to discuss their health (physical and psychological) as part of the intervention, and it is possible that this may have affected reporting of health problems as part of study assessments. Loss to follow‐up was a further problem in half of these trials. Even relatively low sample attrition (less than 5%) may mean it is more difficult to interpret results for outcomes that occur infrequently (such as serious maternal morbidity) as those with health problems may be less likely to respond. We were unable to investigate possible publication bias as too few studies contributed data.

Most of the results in the review are derived from one or two studies and several of the studies had small sample sizes; we were unable to pool many of the data in meta‐analysis; there was a lack of consistency between studies in terms of the outcomes reported, and the time and way in which outcomes were measured. In addition, there was considerably diversity in terms of the aims of interventions and the way they were delivered. These differences mean that for any one outcome there were few data and most of our results were inconclusive.

Potential biases in the review process

We are aware that authors carrying out a review may themselves introduce bias. We took a number of measures to try to reduce bias; at least two review authors carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. All data were checked after entry. Nevertheless, assessing risk of bias for example, requires individual judgements and it is possible that a different review team may have made different assessments.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Generally, postnatal home visits seem likely to increase maternal satisfaction, and may promote breastfeeding, and reduce infant morbidities, but these effects are very much dependent upon the aims of the package of the postnatal interventions. The findings are in line with what the previous literature has shown.

Implications for practice

Generally, postnatal home visits have been recommended where mothers and their newborns are discharged early to promote infant health and maternal satisfaction. However, the results of this review are inconclusive and in the absence of strong or consistent evidence the frequency, timing, duration and intensity of such postnatal care visits should be determined by individual and local needs, and where possible, should take account of maternal preferences.

Implications for research

Further well designed randomised controlled trials or any other studies evaluating this complex intervention will be required to formulate the optimal package. The design of interventions in such a trial should be based upon postpartum health priorities in each context, which would determine the intensity and content of postnatal care visits.

Feedback from MacArthur and Bick, 12 March 2015

The findings of our study ( MacArthur 2002 ) have been included in this review in the opposite direction to the results reported in our Lancet paper. The review states that the intervention group had worse (higher) EPDS scores than the control group, which is opposite to the actual findings.

The review concludes "Significantly more women receiving extended postnatal care had high EPDS scores (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.92) (Analysis 2.9)". This is completely wrong as it was significantly FEWER, not more.