Objectives of Field Trips

Ralph heibutzki, 27 jun 2018.

What student doesn't look forward to the opportunity to leave the confines of a stuffy classroom and step out into the wide wide world during school hours? For decades, American students have taken field trips to museums, historical sites and other culturally enriching institutions as a way to supplement the lessons they learn in the traditional, yet limited, school setting. Higher ups, such as superintendents, can be tempted in tight budgetary situations to eliminate such trips or opt for virtual outings that occur entirely on the computer. However, proponents see many good reasons for continuing field trips, such as the chance to reinforce what students learn in the classroom while offering them an active learning experience that exposes them to new ideas.

Explore this article

- Deepen Social and Historical Knowledge

- Develop Critical Thinking Skills

- Highlight Career Opportunities

- Promote Interest in Art and Culture

- Other Considerations

1 Deepen Social and Historical Knowledge

Field trips expose students to different lifestyles, places and eras. By touring an institution like the National World War I Museum, whose collection includes 75,000 artifacts from all the warring nations, students are able to broaden their understanding of the conflict. Looking first-hand at such meaningful exhibits allows teachers to expand on topics that are difficult to cover during a normal class period. Students also hear other perspectives besides the official U.S. viewpoint. A similar historic attraction is likely within driving distance of your district.

2 Develop Critical Thinking Skills

Evidence suggests that field trips stimulate students' reasoning skills. In a recent study, a team of University of Arkansas researchers asked third-twelfth grade students to write an essay on Bo Bartlett's painting "The Box," located at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Northwest Arkansas. Overall, the researchers found that students assigned by a lottery to tour the museum showed a 9 percent improvement in critical thinking skills, including the ability to describe and comment on the painting.

3 Highlight Career Opportunities

Students connect meaningfully with the working world through field trips. For example, one popular outing among older students involves arranging a session with professional chefs to explore the gastronomy world. Teachers then choose specific aspects of the field to discuss, such as food labels. Introducing these concepts to students helps them visualize potential career choices.

4 Promote Interest in Art and Culture

The opportunity for students to have culturally rich learning experiences on school trips can serve as the beginning of their interests in art and similar subjects. According to the University of Arkansas survey, students who tour institutions like Crystal Bridges are more likely to develop an interest in cultural affairs than peers who don't. Of the 10,912 students surveyed, 70 percent who toured the museum right away were more likely to recommend that their friends do likewise, versus 66 percent who had to wait for a different tour date. The researchers also found that students who toured the museum were 18 percent more likely to return versus classmates who didn't get a tour right away, but received a coupon to redeem within six months for a future visit.

5 Other Considerations

The field trip experience provides measurable benefits beyond a school's curriculum, as well. For example, touring a National Park Service site underscores its cultural and environmental value in the community, according to an analysis on the agency's website. Visiting an NPS site instills positive ethical values, like the need to preserve the park, while children are still forming opinions. Children also develop social skills by learning with peers in a relaxed setting, which improves their comprehension and retention of the material.

- 1 Education Next: The Educational Value of Field Trips

- 2 National World War I Museum at Liberty Memorial: Collections: A World-Class Collection in the Heart of America

- 3 National World War I Museum at Liberty Memorial: Plan a Field Trip: Teaching Beyond the Textbook

- 4 U.S. National Park Service: Benefits of On Site Educational Field Trips

About the Author

Ralph Heibutzki's articles have appeared in the "All Music Guide," "Goldmine," "Guitar Player" and "Vintage Guitar." He is also the author of "Unfinished Business: The Life & Times Of Danny Gatton," and holds a journalism degree from Michigan State University.

Related Articles

How to Apply Diversity Skills in & Out of the Workplace

Reasons to Join the National Honor Society

Fun Field Trip Ideas for 3rd & 4th Graders

Strategies for Teaching Gifted & Talented Students

Places to Meet Women in Bellingham, Washington

Art Appreciation in Elementary Schools

Fun Avid Projects for Middle Schools

How Does a Longer School Day Help Students?

How to Teach Constellations to Preschool Kids

The Top Technology Must-Haves for Classrooms

The Effects of Culture & Diversity on America

Good Qualitative Research Topics in Education

Dayton, Ohio Singles Social Clubs

Date Ideas in Claremont, CA

Top Canadian Universities for Psychology

The Top Activities for Senior Citizens in Chicago

How to Overcome Ethnocentrism

Places to Take Your Girlfriend for Fun in Columbia,...

The Best Private Schools on Long Island

Advantages & Disadvantages of the Internet in Education

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

- Our Mission

Yes, Field Trips Are Worth the Effort

Culturally enriching trips can boost grades and decrease absences and behavioral infractions, new research reveals.

As a teacher, Elena Aguilar often looked for opportunities to get her students out of the classroom and into different neighborhoods or natural environments. “We did the usual museum trips and science center stuff, but I loved the trips which pushed them into unfamiliar territory,” writes Aguilar , an instructional coach and author. Nudging kids out of their comfort zones, she says, “taught them about others as well as themselves. It helped them see the expansiveness of our world and perhaps inspired them to think about what might be available to them out there.”

Aguilar’s thinking made an impact: 15 years after traveling with her third-grade class to Yosemite National Park, a student contacted Aguilar on Facebook to thank her for the life-changing excursion. “You changed our lives with that trip,” the student wrote. “It's what made me want to be a teacher, to be able to give that same gift to other kids.”

As schools grapple with pandemic-related concerns about balancing in-seat instructional time with non-essentials like trips, new research published in The Journal of Human Resources argues that field trips, and the vital educational experiences that they provide—whether it’s a visit to a local museum or a big commitment like Aguilar’s national park trip—deliver a host of positive social and academic outcomes and are worth the effort.

“The pandemic should not keep schools from providing these essential cultural experiences forever,” asserts Jay P. Greene , one of the study’s co-authors and a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, in an opinion piece for the Daily News . “If schools make culturally-enriching field trips an integral part of the education experience, all students—especially those whose parents have a harder time accessing these experiences on their own—would benefit.”

In the study, researchers assigned more than 1,000 fourth- and fifth-grade students in Atlanta to two groups. One group participated in three to six “culturally-enriching” field trips—visits to an art museum, a live theater performance, and a symphony concert—while students in the control group stayed put in class. The outcome? Kids in the field trip group “scored higher on end-of-grade exams, received higher course grades, were absent less often, and had fewer behavioral infractions,” compared to students in the control group, according to a ScienceDaily brief . Benefits lasted two to three years, Greene writes, and were “most visible when students were in middle school.”

“We are able to demonstrate that a relatively simple intervention—and we consider it pretty low-touch; three field trips in a year, maybe six field trips in two years—can actually have some substantial impacts,” says lead study author Heidi Holmes Erickson in an interview with The 74 . “They’re not just limited to social benefits. It shows that smaller interventions can actually have some significant effects on academics as well.”

Field trips aren’t a threat to in-class instruction, Erickson notes, they’re a tool to help bolster engagement and expand students’ horizons. “It's possible to expose students to a broader world and have a culturally enriching curriculum without sacrificing academic outcomes, and it may actually improve academic outcomes,” Erickson says. Far from harming test scores, the researchers found that culturally rich excursions reinforce academics and “students who participated in these field trips were doing better in class.”

Meanwhile, class trips don't need to be elaborate productions to make an impact: small excursions outside the classroom—"low-touch," as the researchers call them—can pack a punch. Here’s how three educators recommend dialing it back with low-stakes options that are both engaging and stimulating for students, but might not require days to prepare and plan:

Make Them Bite-Sized : Instead of allocating an entire day to a field trip, educational consultant Laurel Schwartz takes her classes on micro field trips , or “short outings that can be completed in a single class period.” These real-world encounters, she says, are especially beneficial for English learners and world language students. A micro field trip to a nearby park or around school grounds, for example, can be a great opportunity to “enhance a unit on nature and wildlife while reinforcing vocabulary for senses, colors, and the concepts of quantity and size,” Schwartz writes. “Afterwards, students might write descriptive stories set in the place you visited using vocabulary collected and defined together by the class.”

Try Teacher-Less Trips : To encourage exploration and learning outside of the classroom, former social studies teacher Arch Grieve removes himself from the equation with teacher-less field trips rooted in students’ local communities. Grieve only suggests options that are directly tied to a unit being discussed in class—like attending a talk at a local university or visiting a museum or cultural festival—and offers extra credit to incentivize students. “These trips allow for a greater appreciation of my subject matter than is possible in the school setting, and perhaps best of all, there's little to no planning involved.”

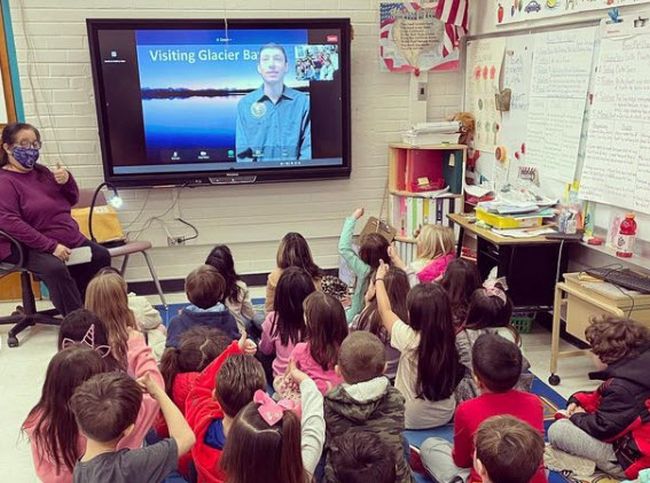

Explore Virtual Options : It may not be as fun as visiting in person, but the Internet makes it possible to visit museums like The National Gallery of London and The Vatican Museums without leaving the school building. Middle school English teacher Laura Bradley likes to search the Museums for Digital Learning website by topic, keyword, and grade level, to find lessons and activities that meet her unique curricular needs. The site grants access to digitized museum collections, 3D models, audio files, documents, images, and videos.

- The Journal

- Vol. 14, No. 1

The Educational Value of Field Trips

Jay P. Greene

Brian Kisida

Daniel H. Bowen

Jay P. Greene joined EdNext Editor-in-chief Marty West to discuss the benefits of field trips, including how seeing live theater is a more enriching experience to students, on the EdNext podcast .

Crystal Bridges; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; School Tour © 2013 Stephen Ironside/Ironside Photography Bo Bartlett – “The Box” – 2002 • Oil on Linen • 82 x 100 – Photographer is Karen Mauch

The school field trip has a long history in American public education. For decades, students have piled into yellow buses to visit a variety of cultural institutions, including art, natural history, and science museums, as well as theaters, zoos, and historical sites. Schools gladly endured the expense and disruption of providing field trips because they saw these experiences as central to their educational mission: schools exist not only to provide economically useful skills in numeracy and literacy, but also to produce civilized young men and women who would appreciate the arts and culture. More-advantaged families may take their children to these cultural institutions outside of school hours, but less-advantaged students are less likely to have these experiences if schools do not provide them. With field trips, public schools viewed themselves as the great equalizer in terms of access to our cultural heritage.

Today, culturally enriching field trips are in decline. Museums across the country report a steep drop in school tours. For example, the Field Museum in Chicago at one time welcomed more than 300,000 students every year. Recently the number is below 200,000. Between 2002 and 2007, Cincinnati arts organizations saw a 30 percent decrease in student attendance. A survey by the American Association of School Administrators found that more than half of schools eliminated planned field trips in 2010–11.

The decision to reduce culturally enriching field trips reflects a variety of factors. Financial pressures force schools to make difficult decisions about how to allocate scarce resources, and field trips are increasingly seen as an unnecessary frill. Greater focus on raising student performance on math and reading standardized tests may also lead schools to cut field trips. Some schools believe that student time would be better spent in the classroom preparing for the exams. When schools do organize field trips, they are increasingly choosing to take students on trips to reward them for working hard to improve their test scores rather than to provide cultural enrichment. Schools take students to amusement parks, sporting events, and movie theaters instead of to museums and historical sites. This shift from “enrichment” to “reward” field trips is reflected in a generational change among teachers about the purposes of these outings. In a 2012‒13 survey we conducted of nearly 500 Arkansas teachers, those who had been teaching for at least 15 years were significantly more likely to believe that the primary purpose of a field trip is to provide a learning opportunity, while more junior teachers were more likely to see the primary purpose as “enjoyment.”

If schools are de-emphasizing culturally enriching field trips, has anything been lost as a result? Surprisingly, we have relatively little rigorous evidence about how field trips affect students. The research presented here is the first large-scale randomized-control trial designed to measure what students learn from school tours of an art museum.

We find that students learn quite a lot. In particular, enriching field trips contribute to the development of students into civilized young men and women who possess more knowledge about art, have stronger critical-thinking skills, exhibit increased historical empathy, display higher levels of tolerance, and have a greater taste for consuming art and culture.

Design of the Study and School Tours

The 2011 opening of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Northwest Arkansas created the opportunity for this study. Crystal Bridges is the first major art museum to be built in the United States in the last four decades, with more than 50,000 square feet of gallery space and an endowment in excess of $800 million. Portions of the museum’s endowment are devoted to covering all of the expenses associated with school tours. Crystal Bridges reimburses schools for the cost of buses, provides free admission and lunch, and even pays for the cost of substitute teachers to cover for teachers who accompany students on the tour.

Because the tour is completely free to schools, and because Crystal Bridges was built in an area that never previously had an art museum, there was high demand for school tours. Not all school groups could be accommodated right away. So our research team worked with the staff at Crystal Bridges to assign spots for school tours by lottery. During the first two semesters of the school tour program, the museum received 525 applications from school groups representing 38,347 students in kindergarten through grade 12. We created matched pairs among the applicant groups based on similarity in grade level and other demographic factors. An ideal and common matched pair would be adjacent grades in the same school. We then randomly ordered the matched pairs to determine scheduling prioritization. Within each pair, we randomly assigned which applicant would be in the treatment group and receive a tour that semester and which would be in the control group and have its tour deferred.

We administered surveys to 10,912 students and 489 teachers at 123 different schools three weeks, on average, after the treatment group received its tour. The student surveys included multiple items assessing knowledge about art as well as measures of critical thinking, historical empathy, tolerance, and sustained interest in visiting art museums. Some groups were surveyed as late as eight weeks after the tour, but it was not possible to collect data after longer periods because each control group was guaranteed a tour during the following semester as a reward for its cooperation. There is no indication that the results reported below faded for groups surveyed after longer periods.

We also assessed students’ critical-thinking skills by asking them to write a short essay in response to a painting that they had not previously seen. Finally, we collected a behavioral measure of interest in art consumption by providing all students with a coded coupon good for free family admission to a special exhibit at the museum to see whether the field trip increased the likelihood of students making future visits.

All results reported below are derived from regression models that control for student grade level and gender and make comparisons within each matched pair, while taking into account the fact that students in the matched pair of applicant groups are likely to be similar in ways that we are unable to observe. Standard validity tests confirmed that the survey items employed to generate the various scales used as outcomes measured the same underlying constructs.

The intervention we studied is a modest one. Students received a one-hour tour of the museum in which they typically viewed and discussed five paintings. Some students were free to roam the museum following their formal tour, but the entire experience usually involved less than half a day. Instructional materials were sent to teachers who went on a tour, but our survey of teachers suggests that these materials received relatively little attention, on average no more than an hour of total class time. The discussion of each painting during the tour was largely student-directed, with the museum educators facilitating the discourse and providing commentary beyond the names of the work and the artist and a brief description only when students requested it. This format is now the norm in school tours of art museums. The aversion to having museum educators provide information about works of art is motivated in part by progressive education theories and by a conviction among many in museum education that students retain very little factual information from their tours.

Recalling Tour Details. Our research suggests that students actually retain a great deal of factual information from their tours. Students who received a tour of the museum were able to recall details about the paintings they had seen at very high rates. For example, 88 percent of the students who saw the Eastman Johnson painting At the Camp—Spinning Yarns and Whittling knew when surveyed weeks later that the painting depicts abolitionists making maple syrup to undermine the sugar industry, which relied on slave labor. Similarly, 82 percent of those who saw Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter could recall that the painting emphasizes the importance of women entering the workforce during World War II. Among students who saw Thomas Hart Benton’s Ploughing It Under , 79 percent recollected that it is a depiction of a farmer destroying his crops as part of a Depression-era price support program. And 70 percent of the students who saw Romare Bearden’s Sacrifice could remember that it is part of the Harlem Renaissance art movement. Since there was no guarantee that these facts would be raised in student-directed discussions, and because students had no particular reason for remembering these details (there was no test or grade associated with the tours), it is impressive that they could recall historical and sociological information at such high rates.

These results suggest that art could be an important tool for effectively conveying traditional academic content, but this analysis cannot prove it. The control-group performance was hardly better than chance in identifying factual information about these paintings, but they never had the opportunity to learn the material. The high rate of recall of factual information by students who toured the museum demonstrates that the tours made an impression. The students could remember important details about what they saw and discussed.

Critical Thinking. Beyond recalling the details of their tour, did a visit to an art museum have a significant effect on students? Our study demonstrates that it did. For example, students randomly assigned to receive a school tour of Crystal Bridges later displayed demonstrably stronger ability to think critically about art than the control group.

During the first semester of the study, we showed all 3rd- through 12th-grade students a painting they had not previously seen, Bo Bartlett’s The Box . We then asked students to write short essays in response to two questions: What do you think is going on in this painting? And, what do you see that makes you think that? These are standard prompts used by museum educators to spark discussion during school tours.

We stripped the essays of all identifying information and had two coders rate the compositions using a seven-item rubric for measuring critical thinking that was developed by researchers at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. The measure is based on the number of instances that students engaged in the following in their essays: observing, interpreting, evaluating, associating, problem finding, comparing, and flexible thinking. Our measure of critical thinking is the sum of the counts of these seven items. In total, our research team blindly scored 3,811 essays. For 750 of those essays, two researchers scored them independently. The scores they assigned to the same essay were very similar, demonstrating that we were able to measure critical thinking about art with a high degree of inter-coder reliability.

We express the impact of a school tour of Crystal Bridges on critical-thinking skills in terms of standard-deviation effect sizes. Overall, we find that students assigned by lottery to a tour of the museum improve their ability to think critically about art by 9 percent of a standard deviation relative to the control group. The benefit for disadvantaged groups is considerably larger (see Figure 1). Rural students, who live in towns with fewer than 10,000 people, experience an increase in critical-thinking skills of nearly one-third of a standard deviation. Students from high-poverty schools (those where more than 50 percent of students receive free or reduced-price lunches) experience an 18 percent effect-size improvement in critical thinking about art, as do minority students.

A large amount of the gain in critical-thinking skills stems from an increase in the number of observations that students made in their essays. Students who went on a tour became more observant, noticing and describing more details in an image. Being observant and paying attention to detail is an important and highly useful skill that students learn when they study and discuss works of art. Additional research is required to determine if the gains in critical thinking when analyzing a work of art would transfer into improved critical thinking about other, non-art-related subjects.

Historical Empathy. Tours of art museums also affect students’ values. Visiting an art museum exposes students to a diversity of ideas, peoples, places, and time periods. That broadening experience imparts greater appreciation and understanding. We see the effects in significantly higher historical empathy and tolerance measures among students randomly assigned to a school tour of Crystal Bridges.

Historical empathy is the ability to understand and appreciate what life was like for people who lived in a different time and place. This is a central purpose of teaching history, as it provides students with a clearer perspective about their own time and place. To measure historical empathy, we included three statements on the survey with which students could express their level of agreement or disagreement: 1) I have a good understanding of how early Americans thought and felt; 2) I can imagine what life was like for people 100 years ago; and 3) When looking at a painting that shows people, I try to imagine what those people are thinking. We combined these items into a scale measuring historical empathy.

Students who went on a tour of Crystal Bridges experience a 6 percent of a standard deviation increase in historical empathy. Among rural students, the benefit is much larger, a 15 percent of a standard deviation gain. We can illustrate this benefit by focusing on one of the items in the historical empathy scale. When asked to agree or disagree with the statement, “I have a good understanding of how early Americans thought and felt,” 70 percent of the treatment-group students express agreement compared to 66 percent of the control group. Among rural participants, 69 percent of the treatment-group students agree with this statement compared to 62 percent of the control group. The fact that Crystal Bridges features art from different periods in American history may have helped produce these gains in historical empathy.

Tolerance. To measure tolerance we included four statements on the survey to which students could express their level of agreement or disagreement: 1) People who disagree with my point of view bother me; 2) Artists whose work is critical of America should not be allowed to have their work shown in art museums; 3) I appreciate hearing views different from my own; and 4) I think people can have different opinions about the same thing. We combined these items into a scale measuring the general effect of the tour on tolerance.

Overall, receiving a school tour of an art museum increases student tolerance by 7 percent of a standard deviation. As with critical thinking, the benefits are much larger for students in disadvantaged groups. Rural students who visited Crystal Bridges experience a 13 percent of a standard deviation improvement in tolerance. For students at high-poverty schools, the benefit is 9 percent of a standard deviation.

The improvement in tolerance for students who went on a tour of Crystal Bridges can be illustrated by the responses to one of the items within the tolerance scale. When asked about the statement, “Artists whose work is critical of America should not be allowed to have their work shown in art museums,” 35 percent of the control-group students express agreement. But for students randomly assigned to receive a school tour of the art museum, only 32 percent agree with censoring art critical of America. Among rural students, 34 percent of the control group would censor art compared to 30 percent for the treatment group. In high-poverty schools, 37 percent of the control-group students would censor compared to 32 percent of the treatment-group students. These differences are not huge, but neither is the intervention. These changes represent the realistic improvement in tolerance that results from a half-day experience at an art museum.

Interest in Art Museums. Perhaps the most important outcome of a school tour is whether it cultivates an interest among students in returning to cultural institutions in the future. If visiting a museum helps improve critical thinking, historical empathy, tolerance, and other outcomes not measured in this study, then those benefits would compound for students if they were more likely to frequent similar cultural institutions throughout their life. The direct effects of a single visit are necessarily modest and may not persist, but if school tours help students become regular museum visitors, they may enjoy a lifetime of enhanced critical thinking, tolerance, and historical empathy.

We measured how school tours of Crystal Bridges develop in students an interest in visiting art museums in two ways: with survey items and a behavioral measure. We included a series of items in the survey designed to gauge student interest:

• I plan to visit art museums when I am an adult.

• I would tell my friends they should visit an art museum.

• Trips to art museums are interesting.

• Trips to art museums are fun.

• Would your friend like to go to an art museum on a field trip?

• Would you like more museums in your community?

• How interested are you in visiting art museums?

• If your friends or family wanted to go to an art museum, how interested would you be in going?

Interest in visiting art museums among students who toured the museum is 8 percent of a standard deviation higher than that in the randomized control group. Among rural students, the increase is much larger: 22 percent of a standard deviation. Students at high-poverty schools score 11 percent of a standard deviation higher on the cultural consumer scale if they were randomly assigned to tour the museum. And minority students gain 10 percent of a standard deviation in their desire to be art consumers.

One of the eight items in the art consumer scale asked students to express the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “I would tell my friends they should visit an art museum.” For all students who received a tour, 70 percent agree with this statement, compared to 66 percent in the control group. Among rural participants, 73 percent of the treatment-group students agree versus 63 percent of the control group. In high-poverty schools, 74 percent would recommend art museums to their friends compared to 68 percent of the control group. And among minority students, 72 percent of those who received a tour would tell their friends to visit an art museum, relative to 67 percent of the control group. Students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, are more likely to have positive feelings about visiting museums if they receive a school tour.

We also measured whether students are more likely to visit Crystal Bridges in the future if they received a school tour. All students who participated in the study during the first semester, including those who did not receive a tour, were provided with a coupon that gave them and their families free entry to a special exhibit at Crystal Bridges. The coupons were coded so that we could determine the applicant group to which students belonged. Students had as long as six months after receipt of the coupon to use it.

We collected all redeemed coupons and were able to calculate how many adults and youths were admitted. Though students in the treatment group received 49 percent of all coupons that were distributed, 58 percent of the people admitted to the special exhibit with those coupons came from the treatment group. In other words, the families of students who received a tour were 18 percent more likely to return to the museum than we would expect if their rate of coupon use was the same as their share of distributed coupons.

This is particularly impressive given that the treatment-group students had recently visited the museum. Their desire to visit a museum might have been satiated, while the control group might have been curious to visit Crystal Bridges for the first time. Despite having recently been to the museum, students who received a school tour came back at higher rates. Receiving a school tour cultivates a taste for visiting art museums, and perhaps for sharing the experience with others.

Disadvantaged Students

One consistent pattern in our results is that the benefits of a school tour are generally much larger for students from less-advantaged backgrounds. Students from rural areas and high-poverty schools, as well as minority students, typically show gains that are two to three times larger than those of the total sample. Disadvantaged students assigned by lottery to receive a school tour of an art museum make exceptionally large gains in critical thinking, historical empathy, tolerance, and becoming art consumers.

It appears that the less prior exposure to culturally enriching experiences students have, the larger the benefit of receiving a school tour of a museum. We have some direct measures to support this explanation. To isolate the effect of the first time visiting the museum, we truncated our sample to include only control-group students who had never visited Crystal Bridges and treatment-group students who had visited for the first time during their tour. The effect for this first visit is roughly twice as large as that for the overall sample, just as it is for disadvantaged students.

In addition, we administered a different version of our survey to students in kindergarten through 2nd grade. Very young students are less likely to have had previous exposure to culturally enriching experiences. Very young students make exceptionally large improvements in the observed outcomes, just like disadvantaged students and first-time visitors.

When we examine effects for subgroups of advantaged students, we typically find much smaller or null effects. Students from large towns and low-poverty schools experience few significant gains from their school tour of an art museum. If schools do not provide culturally enriching experiences for these students, their families are likely to have the inclination and ability to provide those experiences on their own. But the families of disadvantaged students are less likely to substitute their own efforts when schools do not offer culturally enriching experiences. Disadvantaged students need their schools to take them on enriching field trips if they are likely to have these experiences at all.

Policy Implications

School field trips to cultural institutions have notable benefits. Students randomly assigned to receive a school tour of an art museum experience improvements in their knowledge of and ability to think critically about art, display stronger historical empathy, develop higher tolerance, and are more likely to visit such cultural institutions as art museums in the future. If schools cut field trips or switch to “reward” trips that visit less-enriching destinations, then these important educational opportunities are lost. It is particularly important that schools serving disadvantaged students provide culturally enriching field trip experiences.

This first-ever, large-scale, random-assignment experiment of the effects of school tours of an art museum should help inform the thinking of school administrators, educators, policymakers, and philanthropists. Policymakers should consider these results when deciding whether schools have sufficient resources and appropriate policy guidance to take their students on tours of cultural institutions. School administrators should give thought to these results when deciding whether to use their resources and time for these tours. And philanthropists should weigh these results when deciding whether to build and maintain these cultural institutions with quality educational programs. We don’t just want our children to acquire work skills from their education; we also want them to develop into civilized people who appreciate the breadth of human accomplishments. The school field trip is an important tool for meeting this goal.

Jay P. Greene is professor of education reform at the University of Arkansas, where Brian Kisida is a senior research associate and Daniel H. Bowen is a doctoral student.

Additional materials, including a supplemental study and a methodological appendix , are available.

For more, please see “ The Top 20 Education Next Articles of 2023 .”

This article appeared in the Winter 2014 issue of Education Next . Suggested citation format:

Greene, J.P., Kisida, B., and Bowen, D.H. (2014). The Educational Value of Field Trips: Taking students to an art museum improves critical thinking skills, and more . Education Next , 14(1), 78-86.

Last Updated

License this Content

Latest Issue

Spring 2024.

Vol. 24, No. 2

We Recommend You Read

Learning from Live Theater

Students realize gains in knowledge, tolerance, and more

by Jay P. Greene

Getting Ahead by Staying Behind

An evaluation of Florida’s program to end social promotion

Straight Up Conversation: Scholar Jay Greene on the Importance of Field Trips

by Frederick Hess

Field Trips are Valuable Learning Experiences

This Knowledge Base article was written collaboratively with contributions from Karen Knutson and CAISE Admin. This article was migrated from a previous version of the Knowledge Base. The date stamp does not reflect the original publication date.

Field trips are recognized as important moments in learning; a shared social experience that provides the opportunity for students to encounter and explore novel things in an authentic setting. Their importance is supported by professional organizations such as the National Science Teachers Association which asserts field trips can “deepen and enhance” classroom study (NSTA 1999) and the National Research Council who assert a quality science curriculum is one that extends beyond the walls of the classroom (1996).

Findings from Research and Evaluation

Outcomes of field trips.

It is important to recognize that learning outcomes from field trips can range from cognitive to affective outcomes (for a review see: Dewitt & Storksdieck, 2008; also Learning Science in Informal Environments (2009) . Too often, however, only cognitive gains are identified (by schools or museums) ( Kisiel, 2005 ).

Among the many potential outcomes, research has shown that field trips:

Expose students to new experiences and can increase interest and engagement in science regardless of prior interest in a topic (Kisiel, 2005; Bonderup Dohn, 2011),

Result in affective gains such as more positive feelings toward a topic (Csikszentmihalyi & Hermanson, 1995; Nadelson & Jordan, 2012).

Are experiences that can be recalled and useful long after a visit (Salmi, 2003; Falk & Dierking, 1997; Wolins, Jensen, & Ulzheimer, 1992).

Effective Models of Field Trip Experiences

Research has demonstrated that field trips can be designed to more effectively support student learning. Field trips work best when they provide support for students to explore in a personally meaningful way.

Learning in field trips is impacted by many factors (DeWitt & Storksdieck, 2008). The structure of the field trip impacts learning. Some structure is needed to best support student learning, ( Stronck, 1983 ) yet programming that is overly rigid or too aligned with classroom instruction can have a negative effect (Jensen 1994; Griffin & Symington, 1997). If students are not adequately prepared for the experience, the novelty of the setting can negatively impact learning. (Orion & Hofstein, 1994).

Prior knowledge and interests of the students impacts learning during the visit (Falk & Adelman, 2003), the social context of the visit, teacher agendas, student experiences during the field trip, and the presence or absence and quality of preparation and follow-up.

Through a meta-analysis of studies such as these, DeWitt and Osborne (2007) created a model to guide museum program development, Model of Museum Practice which, among other key elements, highlights the importance of encouraging students in the area of “joint productive activity” (p. 690). This includes the opportunity for students to be cognitively engaged and challenged, as they explore areas of personal interest and curiosity and engage in bidirectional communication with each other and adult facilitators.

A successful and quality field trip requires teacher preparation and interaction, yet often teachers are not equipped to, or do not provide this support. See: ( Schoolteacher Learning Agenda Influences Student Learning in Museums ; Griffin & Symington, 1997).

References

Behrendt, M., & Franklin, T. (2014). A Review of Research on School Field Trips and Their Value in Education. International Journal of Environmental & Science Education 9, 235-245. Doi: 10.12973/ijese.2014.213a

Bell, P., Lewenstein, B., Shouse, A. W., & Feder, M. A., (Eds.) (2009). Learning science in informal environments: People, places, and pursuits. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://informalscience.org/research/ic-000-000-002-024/LSIE

Bonderup Dohn, N. (2011). Situational interest of high school students who visit an aquarium. Science Education, 95(2), 337-357. http://informalscience.org/research/ic-000-000-008-700/Situational_Interest_of_High_School_Students_Who_Visit_an_Aquarium

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Hermanson, K. (1995). Intrinsic motivation in museums: Why does one want to learn? In J. H. Falk & L. D. Dierking (Eds.), Public institutions for personal learning (pp.67–77). Washington, DC: American Association of Museums.

DeWitt, J. & Osborne, J. (2007). Supporting teachers on science-focused school trips: Towards an integrated framework of theory and practice. International Journal of Science Education, 29, 685-710. http://informalscience.org/research/ic-000-000-008-500/Supporting_Teachers_on_Science-Focused_Field_Trips

DeWitt, J., Storksdieck, (2008). A Short Review of School Field Trips: Key Findings from the Past and Implications for the Future. Visitor Studies Vol. 11, 2, 181-197. DOI:10.1080/10645570802355562

Falk, J. & Direking, L. (1997). School field Trips: Assessing their long-term impact. Curator, 40, 211-218. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1997.tb01304.x/abstract

Jensen, N. (1994). Children’s perceptions of their museum experiences: A contextual perspective. Children’s Environments, 11(4), 300-324. Retrieved from http://informalscience.org/research/ic-000-000-009-681/Children ’s_Perceptions_of_Their_Museum_Experiences

Kisiel, J. F. (2005). Understanding elementary teacher motivations for science fieldtrips. Science Education, 89(6), 936 – 955. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sce.20085/abstract

Nadelson, L., & Jordan, R. (2012). Student Attitudes Toward and Recall of Outside Day: An Environmental Science Field Trip. The Journal of Educational Research Vol. 105, Iss. 3, 2012. DOI:10.1080/00220671.2011.576715

National Research Council. (1996). National Science Education Standards. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=4962

National Science Teachers Association (1999). NSTA Position Statement: Informal Science Education. Retrieved from http://informalscience.org/research/ic-000-000-009-678/NSTA_Position_Statement

Salmi, H. (2003). Science centres as learning laboratories: experiences of Heureka, the Finnish Science Centre. International Journal of Technology Management, 25, 460–476. Retrieved from http://www.heureka.fi/portal/englanti/about_heureka/research/international_journal_of_technology_management/

Stronck, D. R. (1983). The comparative effects of different museum tours on children’s attitudes and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 20(4), 283 - 290. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tea.3660200403/abstract

Wolins, I. S., Jensen, N., & Ulzheimer, R. (1992). Children’s memories of museum field trips: A qualitative study. Journal of Museum Education, 17(2), 17–27. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/pss/40478925

Whitesell, E. R. (2016). A Day at the Museum: The Impact of Field Trips on Middle School Science Achievement. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. D: 10.1002/tea.21322.

Ultimate Guide to Planning Field Trips for Kids

Welcome to our guide for planning and preparing for a field trip! As a preschool teacher , here I provide you with comprehensive information and helpful tips on organizing a successful and enriching field trip for kids , specifically geared towards preschool-aged children. Join me as we dive into the exciting world of field trip planning and activities!

Section 1: Choosing the Perfect Destination

When planning a field trip, selecting the right destination is key. Consider the educational objectives, curriculum relevance, and age appropriateness of the location. Look for interactive exhibits, guided tours, and activities that align with the topics you want to cover. Some popular choices for preschool field trips include museums, nature centers , farms , aquariums, and planetariums.

Section 2: Field Trip Planning

Set Clear Goals : Determine the learning outcomes and objectives you want to achieve through the field trip. Tailor your activities and discussions accordingly to maximize the educational value.

Research and Pre-Visit : Familiarize yourself with the destination by researching online, contacting the facility, and even scheduling a pre-visit. This will help you anticipate any potential challenges and tailor the experience to meet the needs of your young learners.

Obtain Permissions : Communicate with parents and obtain necessary permissions and waivers well in advance. Inform them about the field trip’s purpose, date, duration, and logistics. Provide them with emergency contact information and any specific requirements for the day.

Volunteering Teachers : Coordinate with teachers and parent volunteers to ensure sufficient supervision during the field trip. Assign specific responsibilities to each volunteer, such as group leaders, first aid assistants, or photographers. Clearly communicate the expectations and guidelines for the volunteering teachers to maintain a safe and organized trip.

Arrange Transportation : Determine the most suitable mode of transportation based on the distance, group size, and accessibility of the destination. Ensure you have sufficient adult supervision during transit.

Create a Schedule : Develop a detailed itinerary that includes arrival and departure times, activity timelines, lunch breaks, and restroom breaks. A well-structured schedule ensures a smooth and organized experience.

Dietary Considerations : Before the field trip, collect information about any dietary restrictions or allergies among the children. Communicate these requirements to the facility or arrange packed lunches accommodating everyone’s needs.

Snacks and Water : Plan snack breaks throughout the day to energise the children. Encourage parents to pack healthy snacks such as fruits, granola bars, or cheese sticks. Additionally, ensure an adequate water supply or provide refillable water bottles for each child.

Section 3: Field Trip Activities

Guided Tours: Arrange guided tours led by knowledgeable staff or docents who can provide relevant information and engage the children in interactive discussions. Encourage students to ask questions and actively participate in the tour.

Hands-on Experiments : Seek out activities that allow children to engage in hands-on experiments and exploration. This tactile experience will deepen their understanding and leave a lasting impression.

Interactive Workshops : Many educational destinations offer workshops tailored to specific age groups. These workshops often involve interactive demonstrations, experiments, or crafts, providing a valuable and engaging learning experience.

Scavenger Hunts : Incorporate scavenger hunts or treasure hunts to make the field trip more exciting and interactive. Prepare age-appropriate clues or questions related to the exhibits or environment for the children to solve.

Reflection and Discussion : Allocate time for reflection and group discussions at various points throughout the trip. Encourage children to share their observations, ask questions, and express their thoughts and feelings about the experience.

Read more on: Places to take preschool kids for an educational field trip

Section 4: Safety Considerations

First Aid and Emergency Preparedness : Ensure you have a well-stocked first aid kit and designate a responsible adult with first aid training. Familiarize yourself with emergency procedures and establish a plan for any unforeseen situations.

Adult-to-Child Ratio : Maintain an appropriate adult-to-child ratio to ensure the safety and supervision of all participants. Consider dividing the children into smaller groups, each with a designated adult supervisor. This allows for better management and attention to individual needs.

Medical Information : Collect and carry necessary medical information for each child, including allergies, medications, and emergency contact details. Keep this information easily accessible in case of any medical emergencies.

Rules and Behavior Expectations : Clearly communicate the behaviour expectations to both children and accompanying adults before the trip. Emphasise the importance of following instructions, staying with the group, and respecting the facility and its exhibits.

Communication Plan : Establish a communication plan to keep parents informed throughout the trip. Share contact details and schedule regular updates, ensuring parents know of any changes or delays.

Section 5: Post-Trip Follow-up

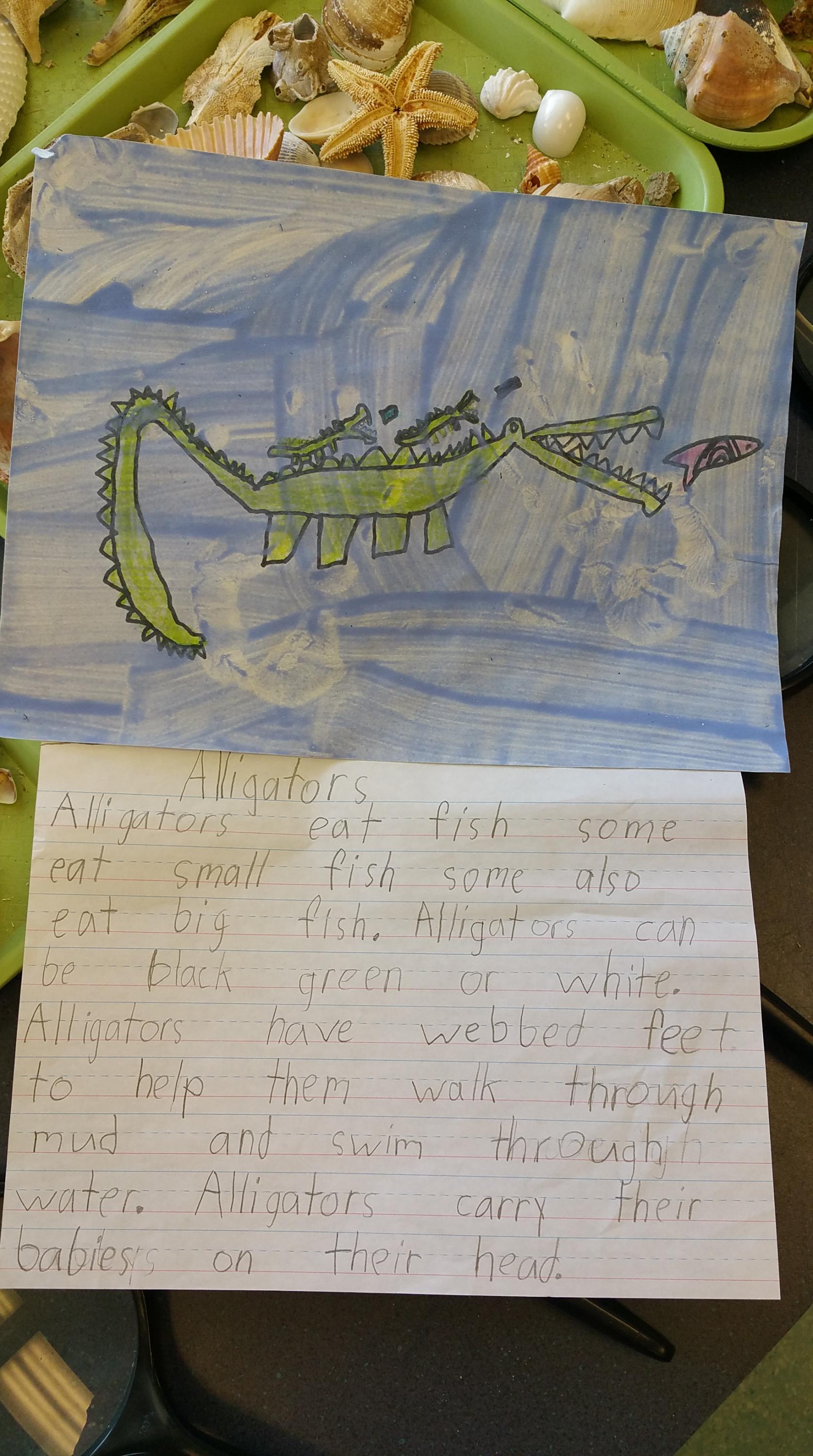

Reflection Activities : Engage the children in post-trip activities that encourage reflection and reinforce learning. This could include discussions, journaling, or creating artwork inspired by their experiences.

Parent Engagement : Share highlights and photos of the field trip with parents through newsletters, emails, or a dedicated online platform. Encourage parents to discuss the trip with their children and extend their learning at home.

Thank-You Notes : Have the children write thank-you notes or draw pictures expressing their gratitude to the destination and any staff members who made the trip memorable. This teaches them the importance of appreciation and reinforces social skills.

Evaluation and Feedback : Gather feedback from both children and accompanying adults to evaluate the success of the field trip. Use this feedback to improve future trips and enhance the overall experience.

Volunteer Appreciation : Express your gratitude to the volunteering teachers for their support and dedication. Recognize their contributions through thank-you notes, certificates, or small tokens of appreciation. This gesture fosters a sense of teamwork and encourages continued involvement in future field trips.

Conclusion:

Organizing an educational field trip for preschool kids requires careful planning and preparation, but the rewards are immeasurable. By selecting the right destination, creating a well-structured itinerary, and incorporating engaging activities, you can provide a valuable and memorable experience that nurtures young minds. Remember to prioritize safety, communicate effectively, and follow up with post-trip activities to maximize the educational impact. So, embrace the excitement of field trip planning, and watch as your preschoolers embark on an educational journey they’ll cherish for years to come.

Popular Tags:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post You Also Like

A Comprehensive Guide on How to Use Haaka

- April 14, 2024

Exploring Different Parenting Styles and Their Effects

- April 13, 2024

Building Strong Study Habits from a Young Age

- April 10, 2024

Practical Tips for Attachment Parenting for Strengthening Bonds

- March 31, 2024

Free-Range Parenting and Exploring the Philosophy and Practice

- March 18, 2024

- About this Book

- Introduction

- Cooperative Learning

- Culturally Responsive Teaching

Field Trips

- Flipped Classrooms

- Internships

- Math Manipulatives

- Outdoor Education

- Special Education Inclusion

- Study Abroad

- Translations

Choose a Sign-in Option

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

A field trip is an experiential learning opportunity in which students leave the traditional classroom setting to learn within their community. During field trips, K–12 students can participate in a wide variety of experiences to expand upon their current knowledge and to apply what they learn in school. Behrendt and Franklin (2014) pointed out that field trips cannot be replicated within the confines of a classroom; rather, they are experiences that occur within a natural and relevant context. By participating in these trips, teachers enable their students to use their knowledge in real-life settings. There are many different kinds of field trips that vary based on the subject matter being taught. They range from art museums to nature reserves and include both virtual trips and in-person excursions. No matter the location, students are invited to connect with the class content in a personal way (Behrendt & Franklin, 2014). Overall, field trips are a student-centered approach in which students put their learning into action outside the classroom.

Student-Centered Approach

A student-centered approach is just as it says: it is centered around the students rather than centered on the teacher giving instruction (Pearce & Lee, 2021). Field trips embody being student-centered by giving students more autonomy in their learning. As Pattacini (2018) said, “A student-centered learning and teaching approach implies greater involvement of students… They are given many opportunities to voice their opinions and share their experience. Throughout the module, the students are adopting different roles…” (Rethinking Student Roles section). In contrast to the traditional teaching style of lecturing in the classroom, field trips provide a plethora of opportunities for students that they otherwise could not have. Pearce and Lee (2021) stated that field trips "allow students to discover different learning environments, provide enrichment opportunities, and respite from the daily school routine” (Field Trips section). By implementing this student-centered approach, field trips provide countless positive outcomes for students that go beyond just academic success.

The objective of field trips is to provide a variety of opportunities for students to grow both academically and affectively. The benefits extend beyond the traditional classroom setting and have been linked to increased engagement and motivation in school, higher test scores, enhancement of critical thinking skills, and better understanding and retention of content. Not only do field trips provide academic benefits, but they also promote affective learning, such as historical and cultural appreciation. In addition to developing cultural awareness, field trips can magnify students’ emotional well-being and foster positive attitudes towards their communities.

Academic Outcomes

Field trips have been used as an educational tool for many years to provide students with hands-on learning experiences outside of the classroom. As a result, student engagement in learning has increased. In a study by Florick et al. (2021), several groups of fourth and fifth grade students were invited to visit the Woodruff Arts Center and their art partners in Atlanta, Georgia. The purpose of this study was to examine the benefits of multiple field trips as compared to only one field trip throughout the school year. To conduct this study, some groups of students were selected to participate in several field trips while other groups of students attended only one field trip. The results of this study showed that those who participated in multiple field trips were more engaged in learning and had a better attitude towards school, as they demonstrated fewer absences and behavioral violations (Florick et al., 2021).

Furthermore, field trips can improve academic achievement, such as test scores. In the same study mentioned above by Florick et al. (2021), after attending either one or multiple field trips, both groups of students were administered their end-of-year exams, and it showed that the students who participated in multiple field trips scored higher on their exams than those who attended only one field trip (Florick et al., 2021). Whitesell (2016) also analyzed the effects of field trips on middle school students’ standardized test scores in science and found that students who went on a museum field trip scored higher on their science achievement test than those who did not attend a field trip. These studies suggest that field trips can have a positive impact on academic engagement and achievement.

In addition to increased student engagement, field trips can enhance critical thinking skills and improve retention of details. A study conducted by Greene et al. (2014) explored the outcomes of field trips by inviting groups of local K–12 students to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. After each museum tour, students were given surveys to assess their art knowledge and critical thinking. The survey results illustrated that students who participated in the art museum tours were better able to recall details about the paintings they saw. Additionally, these students also demonstrated higher levels of critical thinking skills when they were shown unfamiliar paintings and were able to analyze and discuss these new paintings. Furthermore, Das (2021) shared findings from a study that asked K–12 students to gauge whether field trips increased their knowledge following their participation in a virtual field trip. The findings showed that as students engaged in virtual field trips, they had a better understanding of the content being taught in the classroom (Das, 2021). Field trips bring the curriculum from the classroom to life and teach students how to apply it to their lives.

Affective Outcomes

The benefits of field trips are not only limited to academic achievement, but they also expand to positive affective outcomes, such as social and emotional benefits.

Field trips provide an opportunity for students to build social connections and learn in a collaborative environment. According to Greene et.al (2014), K–12 students who participated in the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art tours learned about various artworks and demonstrated higher levels of historical tolerance and cultural empathy. In other words, they learned how to understand and appreciate others’ perspectives on history and culture. Moreover, the same study found that field trips can promote a sense of belonging, particularly for students from disadvantaged backgrounds who may have limited opportunities to engage in extracurricular activities (Greene et al., 2014). By attending field trips, these students were able to connect with other students and their communities at a much deeper level.

Not only do field trips yield social benefits, but they also provide a much-needed break from the structured and sometimes stressful environment of the classroom, offering students a chance to connect with their emotions and develop positive associations with learning. In a study conducted by Heras et al. (2020), a group of 11- and 12-year-old students in Spain participated in a nature-based field trip and were asked about their perceptions of field trips and nature-based activities following the field trip. These students were chosen because they attended a school program focused on raising environmental awareness and helping their students appreciate the natural and cultural heritage of their community. Based on student responses, the researchers concluded that nature-based field trips can significantly impact students’ emotional well-being. The students reported feeling relaxed, happy, and more connected to nature after their field trip; they also recalled positive memories from their trip.

Similarly, Musselman (2020) described how elementary students found a sense of wonder and curiosity while exploring scientific topics in their community. During a field trip, students had hands-on experience learning about the effects of wind and water on landforms and how sea barriers prevent coastline erosion. As a result, students gained firsthand understanding of the relationship between humans and nature, as well as an opportunity to make a positive impact in the world. Field trips can enhance the overall learning experience and contribute to students’ holistic development.

While many recognize the importance of student-centered field trips, there are several obstacles that hinder teachers and school administrators from providing field trip opportunities including cost, logistics, and content preparation. Depending on the trip, the cost can be a key deterrent. Many schools are already on tight budgets, so adding expensive trips can be difficult. Even if the actual event is free, the price of transportation can cause educators to avoid planning trips altogether (Clarke-Vivier & Lee, 2018). These kinds of cost analysis decisions require both teacher and administrator approval. Some school districts simply may not have access to events due to these issues of cost and extra transportation. Based on the location of the school, some may not have many field trip options available to them (Behrendt & Franklin, 2014). There may not be events or venues close by that offer the desired educational content. In addition, surveyed teachers named logistical planning as another obstacle to their success for these academic excursions (Clarke-Vivier & Lee, 2018). Teachers must coordinate with the field trip facility, organize transportation, and establish student safety measures. Some described the time put into planning field trips as “lost time” because they had to organize large groups and chaperones, which took away from time teaching the course content (Behrendt & Franklin, 2014). In order to be successful in planning field trips, teachers need to find a trip that is applicable to their course content and then prepare students for the experiences that they will have. They may plan pre-trip or post-trip activities that require time away from the required curriculum for the school year. When considering the major benefits of field trip experiences, it is important to note this extra effort from the teachers to both carry out the experience and ensure the students are sufficiently prepared.

As educators continue to actively involve field trips in their teaching, students will experience a higher quality education and educators will experience better classroom results. Beyond the classroom, students also experience social and emotional benefits when they have the opportunity to participate in field trips. While teachers do not have complete control over making a field trip happen, they can submit requests and proposals to the powers that do decide. It is also important that these significant benefits are clearly communicated to the people who do make the decisions (administrators and school boards). Overall, student-centered learning through field trips has many positive outcomes for students that far outweigh any challenges they provide and can be implemented in the classroom in a variety of ways. Nature-based, arts-based, or even virtual field trips will all provide the positive outcomes that teachers are looking for as they work to provide a quality education for their students.

Behrendt, M., & Franklin, T. (2014). A review of research on school field trips and their value in education. International Journal of Environmental & Science Education, 9 (3), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijese.2014.213a

Clarke-Vivier, S., & Lee, J. C. (2018). Because life doesn’t just happen in a classroom: Elementary and middle school teacher perspectives on the benefits of, and obstacles to, out-of-school learning. Issues in Teacher Education , 27 (3), 55–72.

Das, A. (2021, November 9-11). Virtual field trips and impact on learning [Conference presentation]. Innovate Learning Summit 2021, Online, 85–89. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/220274/

Florick, L., Greene, J. P., Levenberg, R., & Pogue, R. (2021). The benefits of multiple arts based field trips. Phi Delta Kappan, 102 (8), 26–29.

Greene, J. P., Kisida, B., & Bowen, D. H. (2014). The educational value of field trips. Education Next, 14 (1), 78–86.

Heras, R., Medir, R. M., & Salazar, O. (2020). Children’s perceptions on the benefits of school nature field trips. Education , 48 (4), 379–391.

Musselman, S. (2020). Connecting with community. Science and Children, 58 (1), 43–47.

Pattacini, L. (2018). Experiential learning: The field study trip, a student-centered curriculum. Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching , 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v11i2.815

Pearce, M. K., & Lee, T. (2021). Comparing teaching methods in an environmental education field trip program. Journal of Interdisciplinary Teacher Leadership, 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.46767/kfp.2016-0037

Whitesell, E. R. (2016). A day at the museum: The impact of field trips on middle school science achievement. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53 (7), 1036–1054. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21322

This content is provided to you freely by EdTech Books.

Access it online or download it at https://edtechbooks.org/student_centered/field_trips .

How to Have a Safe, Fun, and Successful Field Trip

When You Leave the Classroom, There's a Whole New Set of Rules

Hero Images/Getty Images

- Classroom Organization

- Reading Strategies

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- B.A., Sociology, University of California Los Angeles

New teachers might naively think that field trips are easier and more fun than a typical day in the classroom. But throw in crises like a lost group of children or wasp stings, and field trips can go from fun to frantic in no time.

But if you adjust your expectations you can come up with a new, more practical way to approach field trips and minimize the chances of drama and mayhem.

Tips for a Successful Field Trip

Follow these field trip tips and you'll likely create fun learning adventures for your students:

- Explicitly discuss field trip behavior rules with your students beforehand. Teach, model, and review appropriate field trip behavior with your students for at least a week before the big event. Drill into their heads that field trips are not the time or place to mess around and that any aberrant behavior will result in non-participation in any future field trips that school year. Sound serious and back it up with consequences as needed. It's good to have your students scared of testing the boundaries on field trips. Emphasize that they are representing our school's reputation when they are off-campus and that we want to present our best behavior to the outside world. Make it a point of pride and reward them afterward for a job well done.

- Give your students a learning task ahead of time. Your students should show up for the field trip with a base of knowledge on the subject at hand, as well as questions to answer before returning to the classroom. Spend some time in the weeks before the field trip discussing the subject matter. Review a list of questions they will be looking to answer during the field trip. This will keep them informed, engaged, and focused on learning all day long.

- Choose parent chaperones wisely. Field trips require as many adult eyes and ears as you can get, but unfortunately, you can't be everywhere at once. From the first day of school, observe the parents of your students closely, looking for signs of responsibility, firmness, and maturity. A lax or careless parent can be your worst nightmare on a field trip, so choose your parental allies wisely. That way, you'll reap the benefits of having adult partners in the field trip process.

- Make sure you have all the necessary medications. Talk to the school nurse and procure any and all medications that your students usually take during the day. While on the field trip, make sure you administer the medications accordingly. If you have students will allergies, you may need to get trained on how to use an EpiPen. If so, the student involved will need to stay with you at all times.

- Arrive at school early on field trip day. The students will be excited and antsy, ready to go. You'll want to greet the chaperones and give them instructions for the day. It takes some time to organize the sack lunches and ensure that everyone has what they need for the day. And one last pep talk on appropriate behavior never hurt anybody.

- Give your chaperones the tools they need to succeed. Make nametags for all chaperones and students. Create a "cheat sheet" of the day's itinerary, special rules, your cell phone number, and the names of all kids in each chaperone's group; distribute these sheets to each adult on the field trip. Procure and label grocery bags that each chaperone can use to carry the group's sack lunches. Consider getting a little thank-you gift for each chaperone, or treat them to lunch that day.

- Be proactive with regards to challenging students. If you have a student who causes trouble regularly in the classroom , it's safe to assume he or she will cause at least five times more trouble in public. If possible, ask his or her parent to be a chaperone. That will usually limit any potential problems. Also, when you are making groups, split any problem pairs into separate groups. This is a good policy for troublemakers, chatty kids, or bickering frenemies. And it's probably best to keep the most challenging students in your own group, rather than pawning them off on an unsuspecting parent chaperone.

- Count all day. As the teacher, you will likely spend most of your day counting heads and making sure everyone is accounted for. Obviously, the worst thing that can occur on a field trip is losing a student. So count accurately and often. Enlist the help of chaperones in this task, but do it yourself too, for your own peace of mind. Keeping track of each and every student is the number one priority of field trip day.

- Do a "debriefing" when you return to the classroom. If you have a few extra minutes after the field trip and before dismissal from school, put on some soothing classical music and have the students draw about what they saw and learned that day. It gives them a chance to decompress and review what they experienced. The next day, it's a good idea to do a more active and in-depth review of the field trip material, extending the learning further and connecting it to what you're working on in the classroom.

- Write thank-you notes after the field trip. Lead a class language arts lesson the day after your field trip, formally thanking the people who hosted your group. This serves as an etiquette lesson for your students and helps form your school's good reputation at the field trip destination. In future years, this goodwill could translate into prime perks for your school.

With proper planning and a positive attitude, field trips can be unique ways to explore the outside world with your students. Stay flexible and always have a Plan B, and you should do just fine.

- Field Trips: Pros and Cons

- 10 Ways to Make Learning Fun for Students

- 10 Ways to Keep Your Class Interesting

- 5 Fun Field Trip Ideas for Elementary School

- Why Teaching is Fun

- 10 Ways to Put the Home in Schooling

- 7 Back to School Tips for Teachers

- June Themes, Holiday Activities, and Events for Elementary Students

- 4 Tips for Effective Classroom Management

- Last Day of School Activities

- Teaching Strategies to Keep Struggling Students Working

- Creating a Positive Learning Environment

- 12 New Teacher Start-of-School Strategies

- How Teachers Can Ease Students' First Day Jitters

- 6 Ways Elementary School Teachers Can Welcome Students Back to School

- 25 Simple Ways to Say Thank You to Teachers

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Teacher Resources

How to Plan a Class Field Trip

Last Updated: March 11, 2024

This article was co-authored by Catherine Palomino, MS . Catherine Palomino is a former Childcare Center Director in New York. She received her MS in Elementary Education from CUNY Brooklyn College in 2010. This article has been viewed 203,898 times.

A field trip can be a very positive experience to move students outside the classroom into the wider world. There are so many learning experiences that can take place outside of the traditional classroom setting, and conducting a field trip can be a fun and informative way to administer curriculum materials. Field trips can range from day trips to a museum, art gallery, or park to an overnight camp that requires more planning. Regardless of the type of trip you want to facilitate, make sure that there are clear learning objectives. In order to plan a successful class trip make sure that you obtain all necessary permissions and that your students, chaperones, and teachers are adequately prepared. [1] X Research source

Selecting an Educational Site for a Field Trip

- You will also want to clarify a date with the principal in order to ensure that the class trip does not conflict with any other mandatory school activities.

- Ask about emergency protocols while you’re on the trip. Review the school’s guidelines so you can be prepared.

- Learning outcomes of the trip.

- Key vocabulary that will be used and taught during the trip.

- Major concepts that will be taught.

- Can the learning objective be accomplished without a field trip?

- For instance, an overnight ropes course to learn cooperation is not suitable for students in the second grade.

- Young children will not be able to physically complete a ropes course and they are too young to attend an overnight trip.

- Grocery store: Perform a nutritional scavenger hunt. Ask students to read food labels and create a weekly meal plan that would adequately meet their nutritional needs.

- Local restaurant: Learn to cook a nutritional and well-balanced meal at a local restaurant.

- Farm in the area: Visit a farm and learn how livestock are raised, fed, and distributed to customers.

- You should also ask the site how many students they can accommodate. You want to make sure that they can handle the size of your group.

- Ask about areas for seating and how many restrooms there are.

- This additional information will help you to narrow down your list and ultimately select a site.

- Choose a local site to cut down transportation costs.

- Find a site that allows students to bring their own food and snacks so they don’t need to spend money on lunch or food.

- Inquire if the site offers any discounted group or student rates.

- Determine if you need to plan an agenda while you’re there or if a tour will be provided.

- Once you have officially selected a destination, you should get the name, phone number, and email address for a contact person at the site. This will make it easier to book the trip, once you have received the necessary approval.

- If the trip will be over the course of multiple days, you will need to make appropriate overnight arrangements. Camping is an excellent way to provide students with a positive educational experience, but alternative indoor sleeping arrangements are frequently made as well. A tent campground with one or more group campsites, cabin, dormitory, sleeping hall, or hotel that accommodates three students per room would be most ideal for overnight school trips.

Obtaining Permissions for the Field Trip