- Publisher’s Message

- Editor’s Notebook

- Airline News

- Airport Community

- Airport Employment News

- Airport Safety & Security

- AOA Reflections

- Company Spotlight

- Ground Services

- New York Aviation History

- Non-Rev Traveler

- Airport & Aviation Events

- Airport Employment

- Latest Issue

Subscribe for Updates

Get the latest local airport and aviation news delivered right into your inbox each week!

By signing up, you agree to the our terms and our Privacy Policy agreement.

News Updates

LaGuardia Terminal B Achieves LEED Gold Certification

STV Elevates Kristen Van Gilst to Chief of Staff

April 2024 Publisher’s Message

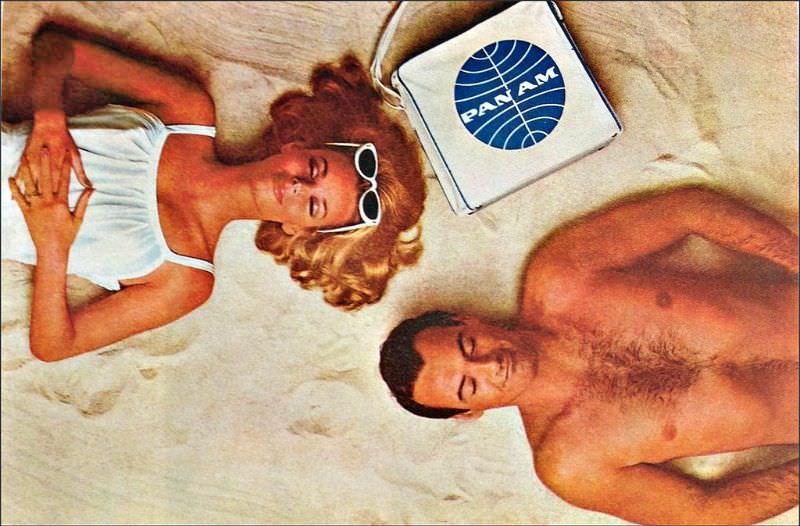

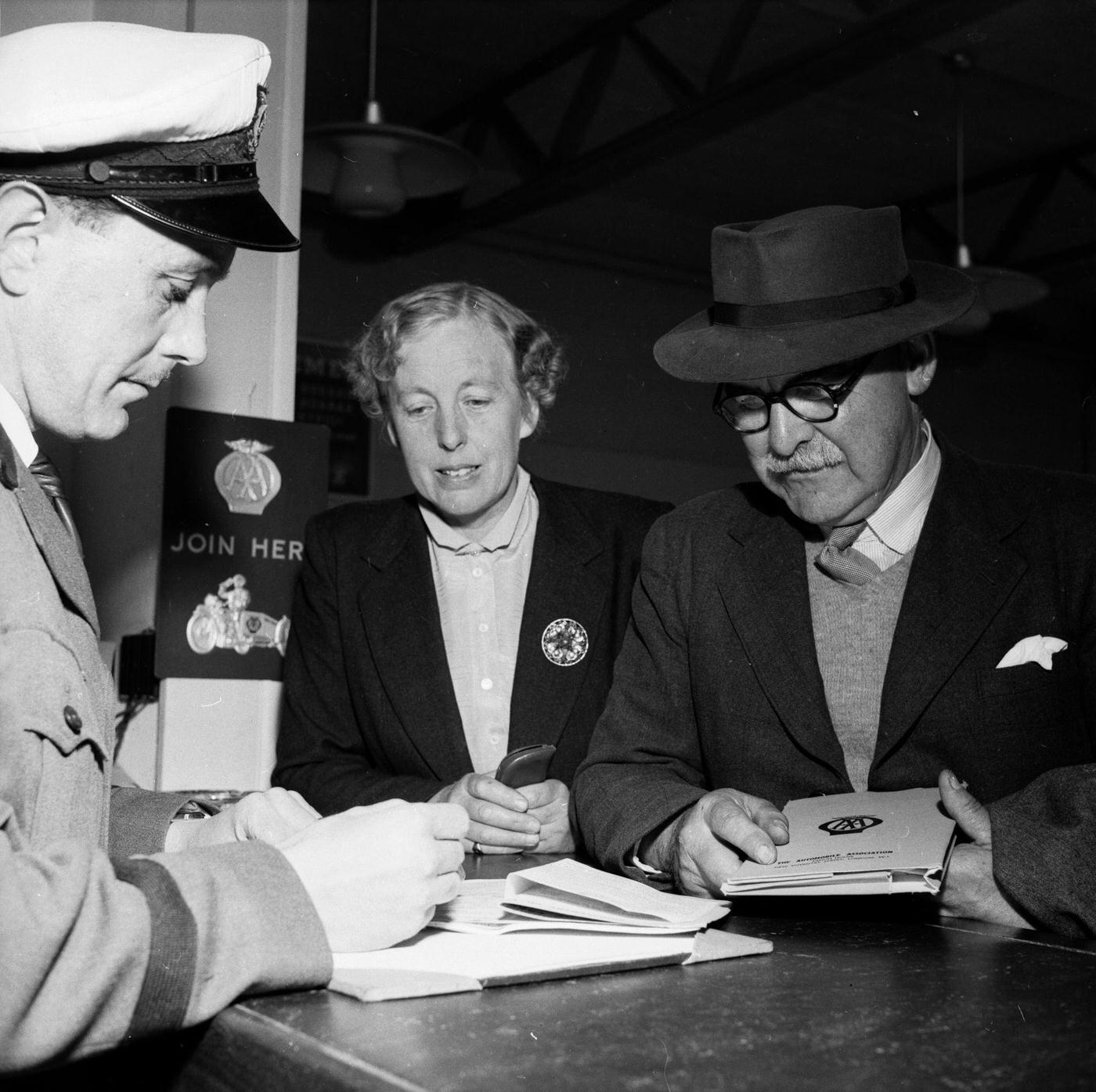

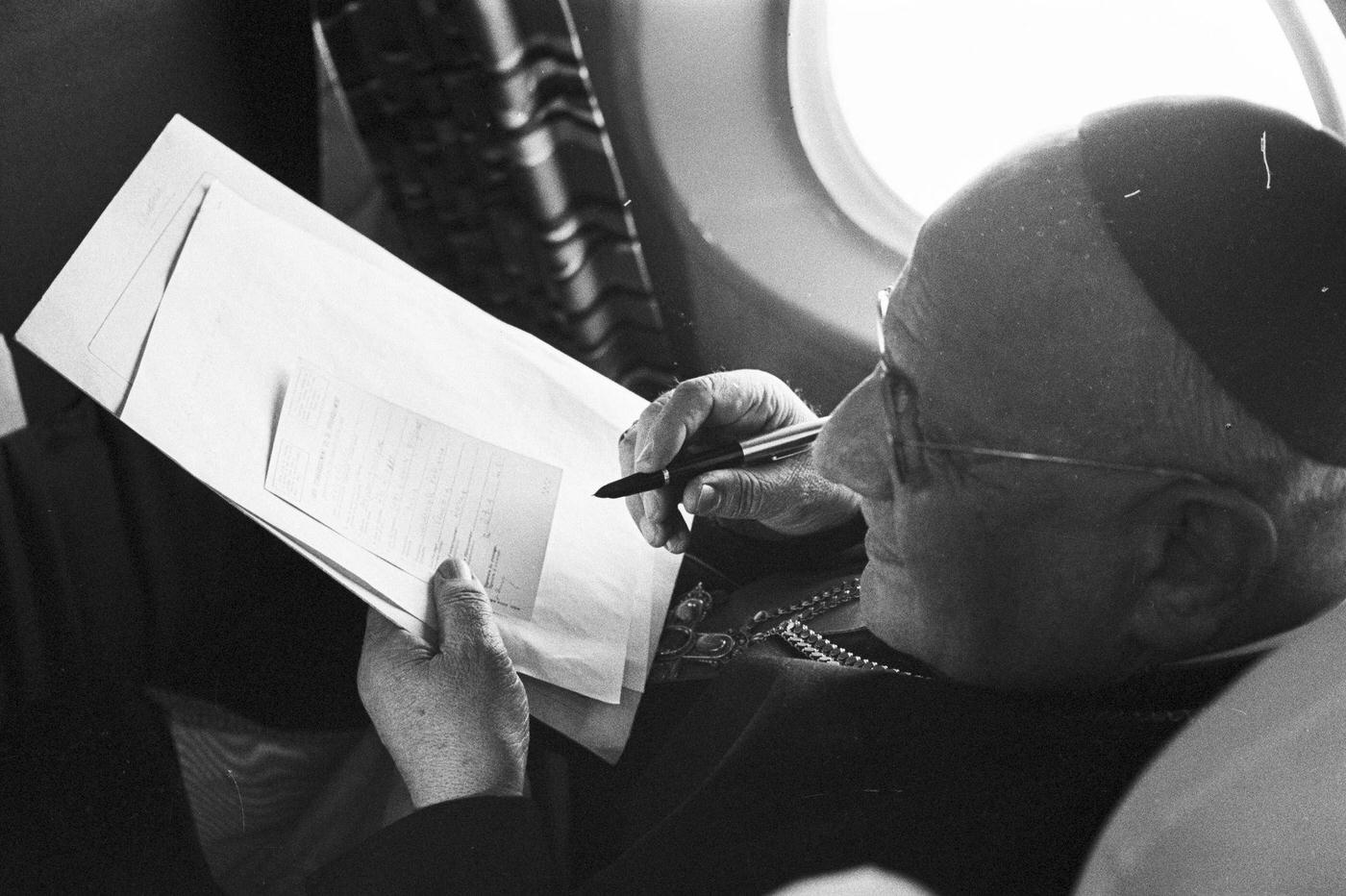

Travel By Air, The Golden Years: 1920s-1960s

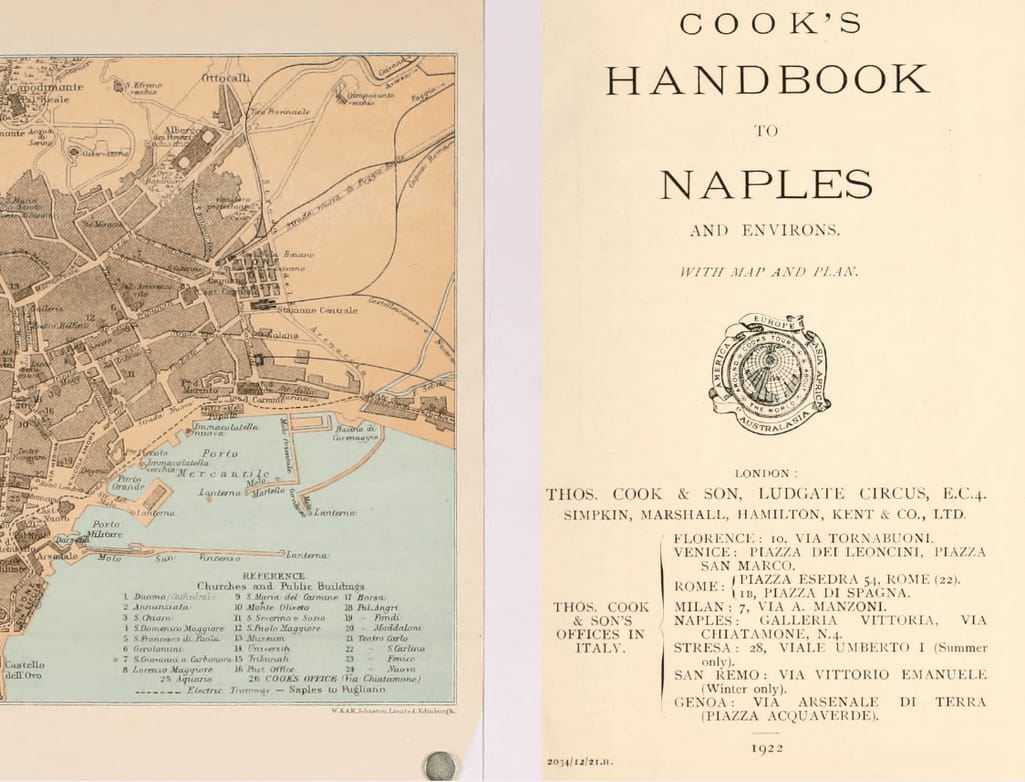

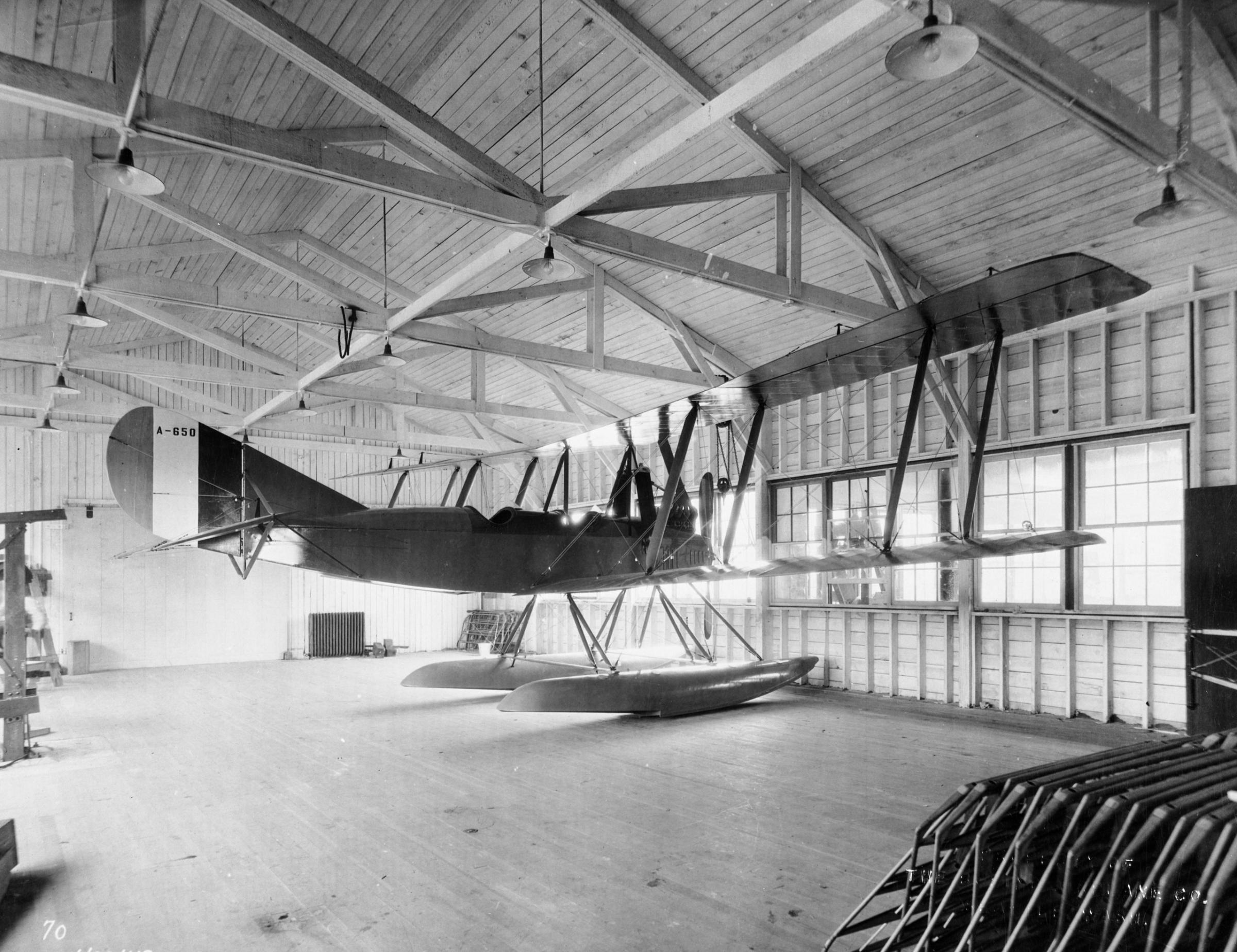

The story of commercial air travel, in a heavier-than-air, winged aircraft, began on January 1, 1914, when the world’s first scheduled passenger service took to the skies in a single-engine Benoist flying boat piloted by pioneering aviator Tony Jannus for the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line. That morning, as a crowd of 3,000 gathered at St. Pete’s municipal pier, a ticket for the inaugural round-trip flight to Tampa was auctioned off, and former mayor Abraham Pheil won the honor with a bid of $400. Prior to lifting off from the St. Petersburg waterfront, Pheil climbed aboard the open cockpit biplane and squeezed onto a single wooden seat beside Jannus. Flying no higher than fifty feet over the water, the flight across the bay to Tampa took 23 minutes, as opposed to the two hours it would take by steamship, or the nearly 12 hours by railroad. Henceforth, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line made two flights daily, six days a week, and charged a regular fare of five dollars per passenger. While the Airboat Line only operated for four months, it carried more than 1,200 passengers across the bay, and led the way for regularly scheduled trans-continental flights.

The Golden Age of Flight

In post-World War I, as the aviation industry grew, several commercial airlines began operations delivering U.S. Airmail, and then carrying passengers. In the 1920s and 1930s, the period between the two World Wars became known as the Golden Age of Flight. Many of the most notable early airlines were founded during this time period; Western Air Express and Ford Air Transport Service in 1925; Pan American Airways in 1927, which flew airmail from Key West to Havana, and Transcontinental & Western Airlines in 1930 (later TWA), when Western Air Express merged with Transcontinental Air Transport.

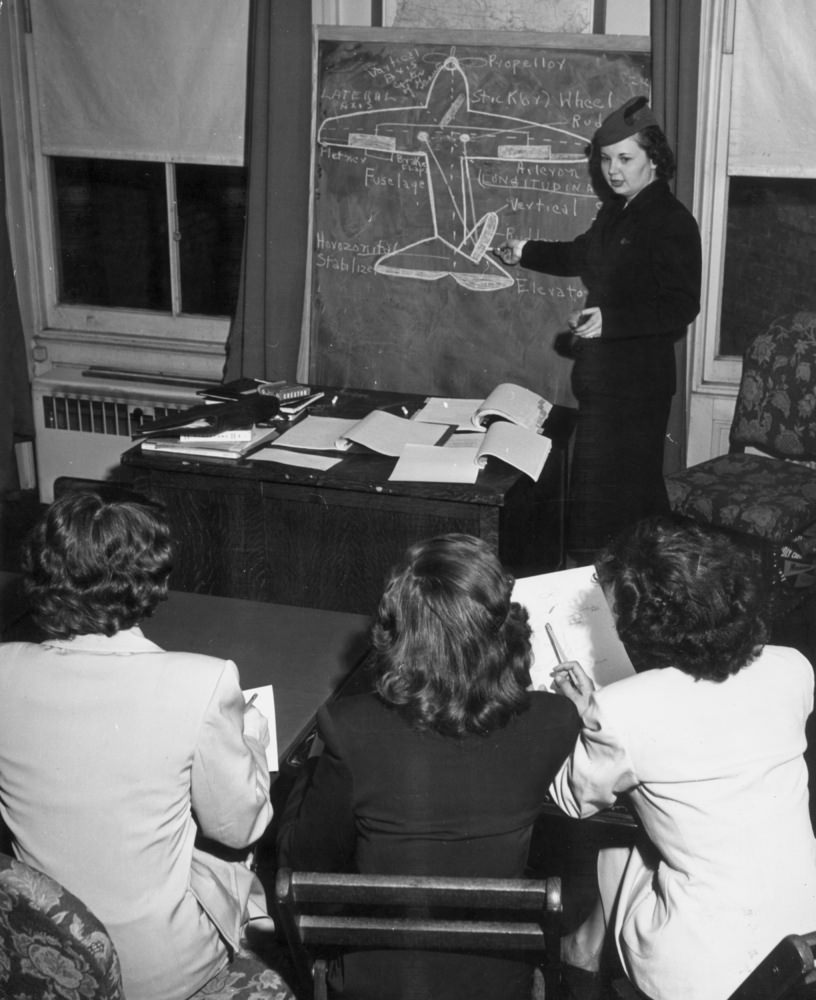

Life aboard a 1920s airliner was quite different from what it is today. Flying was a novel, upscale experience reserved for the wealthiest members of society and business travelers. Airliners carried less than 20 passengers and flew at lower altitudes in unpressurized cabins, frequently landing to refuel. Air travel was noisy and cold, and passengers wore their coats and hats to keep warm. In order to accommodate their every need, uniformed air stewards assisted passengers with their baggage and helped them board the aircraft. Onboard amenities included meals that typically included fruit compotes, cold fried chicken, and elegantly composed sandwiches served on lightweight dishware or wicker baskets. Before the advent of instrument flight in 1929, airplanes could not fly safely at night and had to circumvent mountains. Turbulence, lengthy flight times, airsickness, and other flight-related discomforts often resulted in travel anxiety. In order to keep air travelers at ease, airlines hired nurses to attend to passengers. In 1930, Ellen Church, a nurse and licensed pilot, was hired by Boeing Air Transport (now United Airlines) as the first female stewardess. Despite these discomforts, service evolved quickly in the 1930s. According to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the airline industry expanded from transporting 6,000 passengers in 1930 to over 450,000 by 1934, and 1.2 million by 1938.

The Douglas DC-3 would revolutionize commercial air travel when it had its first flight in 1935. Faster, larger, and more comfortable than its predecessors; the first DC-3, the Douglas Sleeper Transport, was the pinnacle of luxury, with plush seats in four main compartments designed to fold down from the cabin ceiling into sleeping berths. The aircraft could accommodate up to twenty-eight passengers for shorter day flights and fourteen overnight. As a reliable, economical, and profitable airliner, commercial aviation industry giants such as American, United, and TWA ordered the DC-3 for their fleets in 1936 and many other airlines followed suit in the next two years.

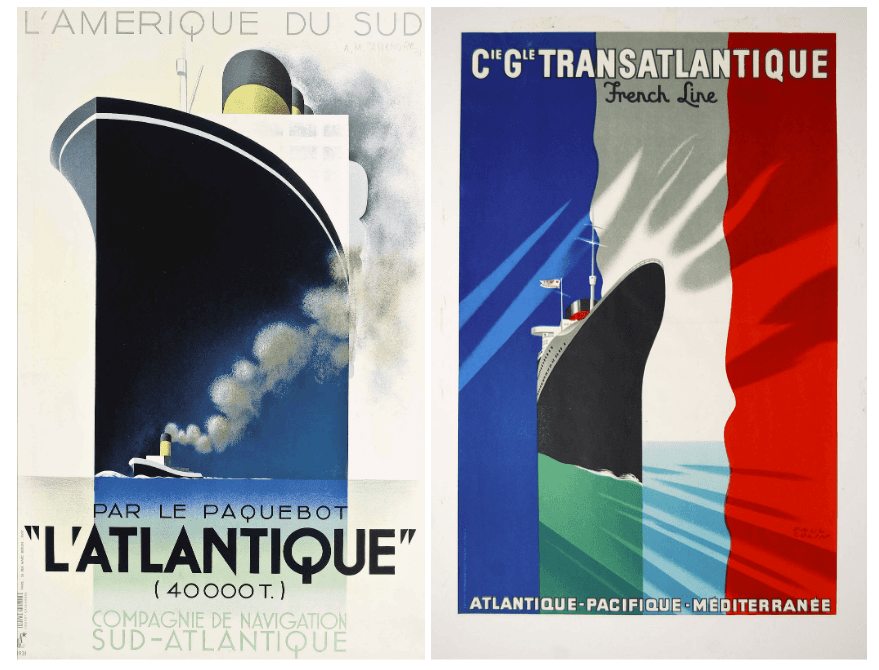

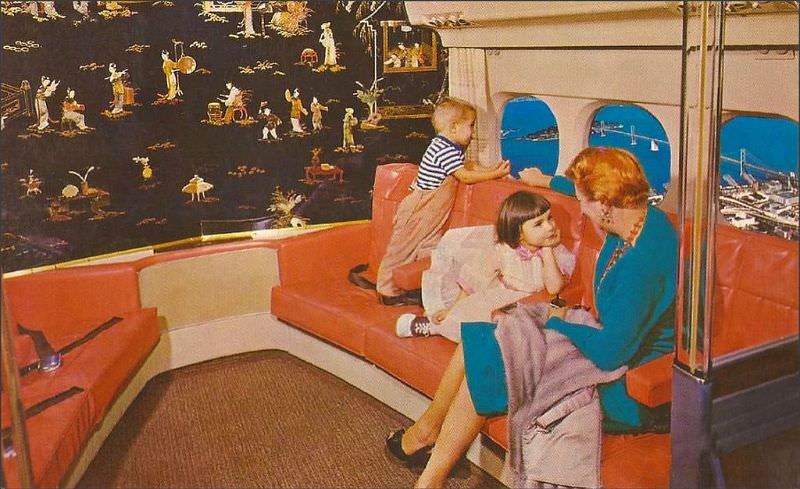

The 1930s heralded in many of the earliest commercial trans-Atlantic flights. Pan American Airways was a forerunner, carrying passengers across the Atlantic in their fleet of flying boats, or ‘Clipper’ aircraft. Transatlantic service began in May of 1939, first flying from Port Washington, Long Island, as the new Marine Air Terminal at LaGuardia was being built. That same year, Boeing 314s were considered the ultimate ‘Clippers’, carrying up to seventy-four passengers across the Atlantic and entering trans-Pacific service, linking all the continents in the Northern Hemisphere. The B-314 was a long-range flying boat that could land anywhere at sea, providing the destination had a sheltered harbor in which it could taxi to. But transport in the 314 was still reserved for the very wealthy, and a return ticket between Manhasset Bay in Port Washington to Southampton, England cost over $650; the equivalent of over $12,000 today.

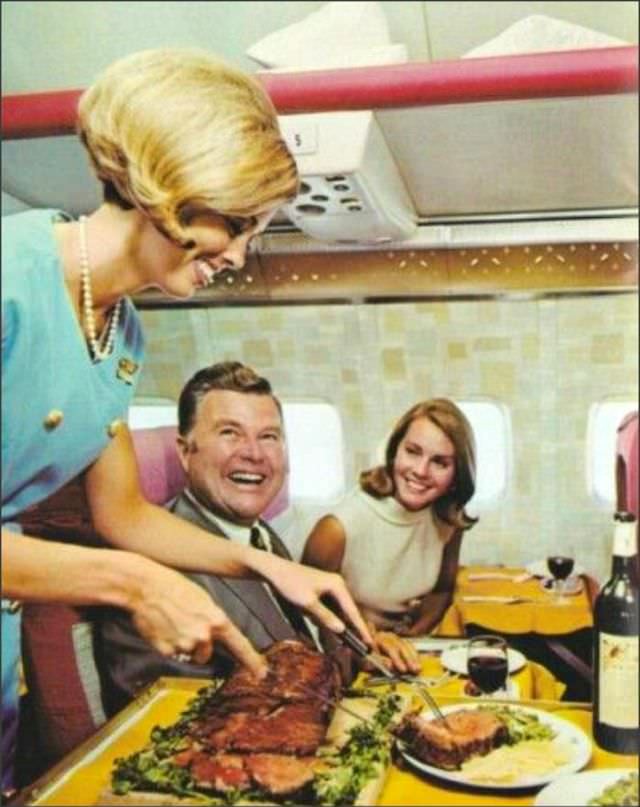

Striving to provide the most pleasant flight experience, Pan American Airways set the gold standard of passenger service. The Boeing 314 had a large upper flight deck and a lower passenger cabin divided into five seating compartments. There was a galley kitchen, a baggage compartment, men, and women’s changing and restrooms, as well as a main lounge that converted into a dining room. White-gloved, tuxedo-clad stewards catered to their passenger’s needs. Meals were lavish experiences with gourmet foods and drink served on fine china, and silverware set on white linen tablecloths. Sleeping quarters on the 314 were roomier than earlier Clippers and its aft De Lux Compartment was called the ‘Bridal Suite’.

“I have heard many planes referred to as flying hotels, but none is more worthy of that description than the Pan American Airways Clipper.” A Wright Aeronautical Co. observer on a B-314 survey flight

First flown in 1938, the Boeing 307 Stratoliner was the first four-engine airliner with a pressurized cabin, allowing it to cruise at an altitude of 20,000 feet, well above the clouds and higher than rough weather. Pan American entered the B-307 into scheduled domestic service on July 4, 1940, with routes to Latin America, and from New York to Los Angeles. The nearly 12-foot-wide cabin carried thirty-three passengers in comfort and provided space for comfortable berths for overnight travelers, as well as observation areas for those who bought the more expensive seats. The airplane’s circular fuselage provided maximum space for five crew members and the Stratoliner was the first land-based airliner to have a flight engineer as a member of the crew.

With the onset of the Second World War, commercial air travel came to a virtual halt and was limited only to those serving the war effort. But commercial aviation, along with the aviation industry as a whole, grew substantially during wartime with the development and production of large-scale aircraft and the utilization of ex-military bombers and transports that were easily converted into commercial airliners. In the post-war years, Lockheed C-69 Constellations, used as transports by the U.S. Army Air Forces, were purchased from the government by TWA and converted into civilian airliners for their fleet. After TWA’s first transatlantic demonstration flight in the Constellation, or ‘Connie’ in December of 1945, TWA launched its transatlantic service in the Connie with a flight from New York to Paris on February 6, 1946.

The Golden Age of Air Travel

After 1945, American aircraft technology set the standard for international air operations, and toward the end of the 1940s, major carriers achieved a strong foothold on international travel.

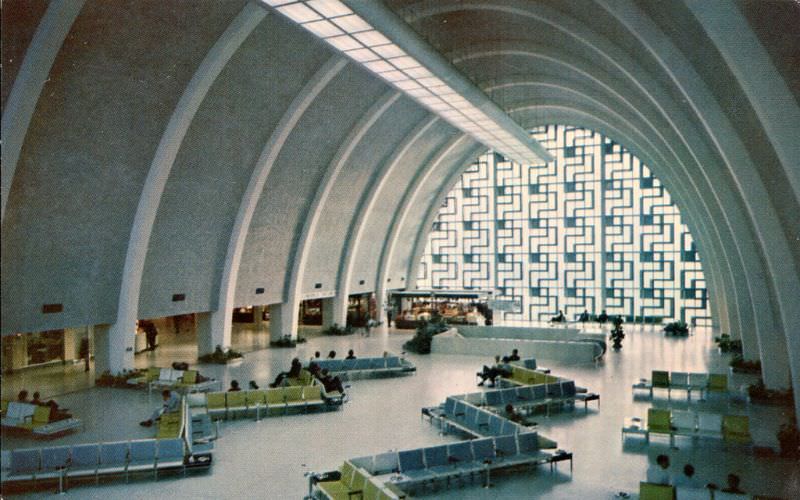

As the decade of the 1940s ended, the era of commercial flight between the 1950s and 1960s was born and became known as the ‘Golden Age of Air Travel’ and the ‘Jet Age’. By 1950, the trans-Atlantic route became the most traveled in the world, and its growing trade produced high profits and intense competition between major international airlines. In the United States, commercial jet service began with the introduction of the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. Larger and more economical than its previous airliners, Pan American began international flights on the B-707 in October of 1958. National Airlines soon began domestic jet service with the 707, and American Airlines opened its own domestic jet service in January of 1959, with a flight from New York to Los Angeles. At the end of the decade, for the first time in history, more people in the United States traveled by air than by railroad.

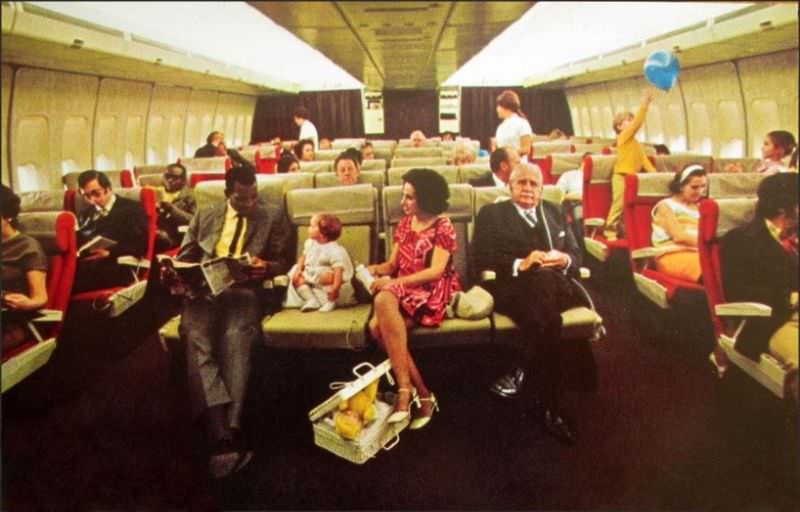

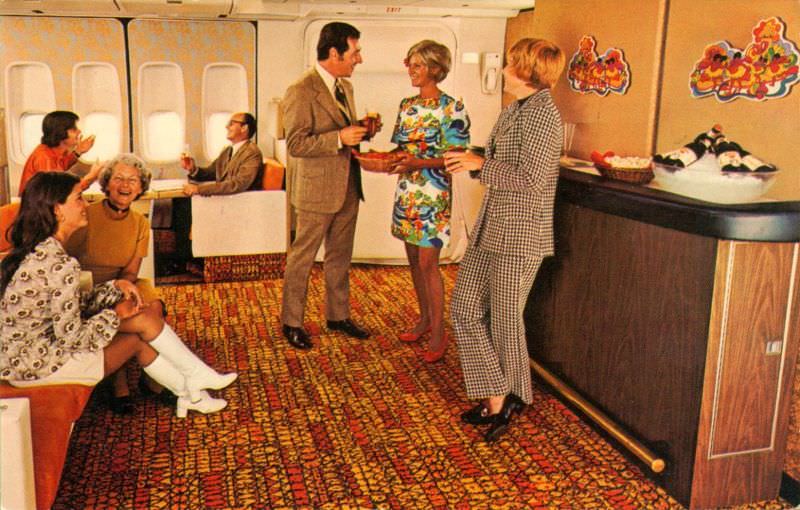

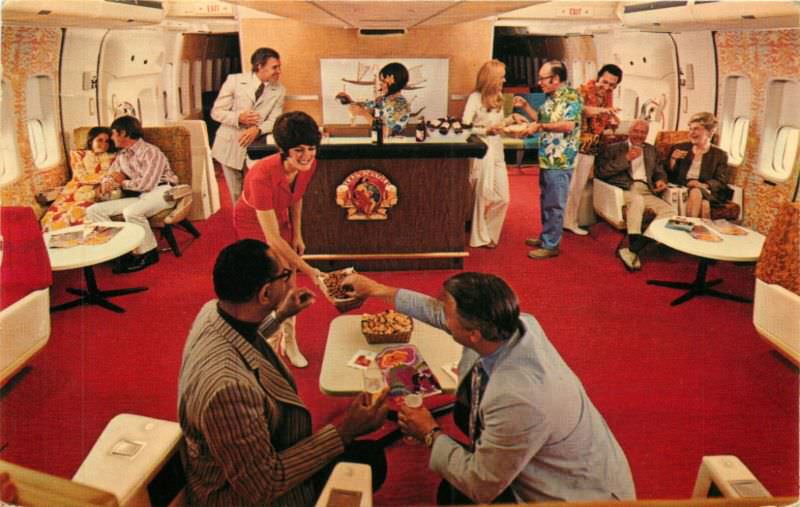

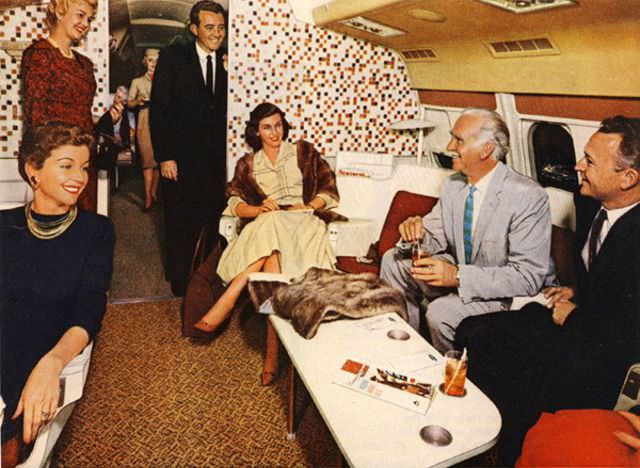

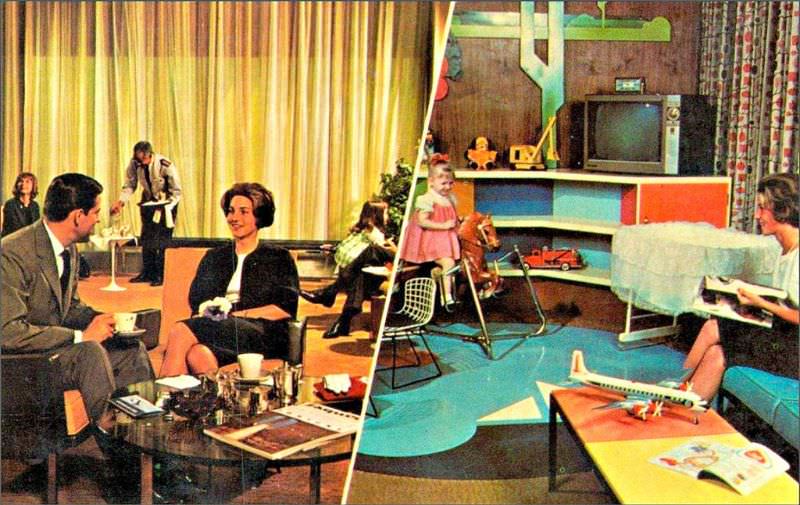

Despite its immense growth, air travel was still expensive and reserved for the elite – celebrities, and movie stars, who were called the ‘Jet Set,’ a name coined in the early 1950s by journalist Igor Cassini. Since commercial flight was still a unique, awe-inspiring event, passengers often documented their experience on airline postcards and posed for group photos prior to boarding. They dressed in their finest clothes, with women in dresses and heels, and men in tailored suits. First Class was spacious, and ‘economy’ seating provided up to six inches more legroom than today. With an increased market for air travel, airlines competed to outdo each other by offering their passengers extravagant amenities; in-flight entertainment, free-flowing cocktails, and fancy multi-course meals that included soup, salad, carved meats, vegetables, dessert, and even lobster. In a 1952 TWA (Trans World Airlines) ad captioned, ‘’Have dinner tonight with the stars!”, an elegantly dressed couple is depicted sitting before a lavishly set table while being served by a burgundy-coated steward and a perfectly coiffed stewardess in uniform and cap.

As the Golden Age of Air Travel led on, well into the 1960s, those who were fortunate enough to enjoy travel on the newest commercial jetliners featured some of the biggest celebrities of the day, including the Beatles, who arrived at JFK International in New York from London aboard a Pan American Boeing 707, to thousands of screaming fans, and some 200 journalists in February of 1964 ….fifty years after the first scheduled flight in the Benoist flying boat before a crowd of 3,000. And while the principles of flight remain the same, commercial air travel as we know it today may not be as lavish an experience as it once was during its Golden Days, but it certainly has come a very long way.

Experience the Golden Days of Air Travel

Today, the Pan Am Museum Foundation Exhibit at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, Long Island pays tribute to Pan American World Airways as a pioneer in commercial aviation through the preservation of Pan Am artifacts, memorabilia, and images that commemorate the company’s history and the people behind this legendary airline.

Also today, at the TWA Hotel at JFK International Airport, visitors are welcome to view the New York Historical Society’s curated exhibitions celebrating TWA’s history. Located within and throughout the former iconic TWA terminal, designed by Eero Saarinen in 1962, the exhibits allow visitors to experience the Jet Age through authentic artifacts, interactive displays, uniforms, memorabilia, and personal narratives. Both are a must see!

Julia Lauria-Blum earned a degree in the Visual Arts at SUNY New Paltz. An early interest in women aviation pioneers led her to research the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) of WW II. In 2001 she curated the permanent WASP exhibit at the American Airpower Museum (AAM) in Farmingdale, NY, and later curated 'Women Who Brought the War Home, Women War Correspondents, WWII’ at the AAM. Julia is the former curatorial assistant at the Cradle of Aviation Museum and is currently an editor for Metropolitan Airport News .

RELATED NEWS & UPDATES

National, the Sunshine Airline

LaGuardia Gateway Partners Welcomes Frontier Airlines to LGA Terminal B

Korean Air to Roll Out Eco-Friendly Uniforms for Maintenance, Aerospace and Cargo Teams

Korean Air Celebrates 45 Years of Serving New York

Air Premia Joins TSA PreCheck Program, Expediting Security Screening for U.S. Travelers

Avianca Airlines Perfectly Times Its Landing In Times Square

Such an interesting historical synopsis of commercial aviation! Well done!

In June 1967 I flew out of El Toro Marine Air Base California towards Vietnam. I returned to SF International in September 1968 via another commercial airline. As did thousands of other GIs going to Vietnam but not so many coming home. I highly recommend purchasing the book by BJ Elliott Prior titled Behind My Wings.

Thank you for comments, Robert. I look forward to obtaining a copy of Behind My Wings and reading about the GIs returning home. I have very strong visual memories of the returning veterans, and especially the POWs.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

- Aviation History

Aviation In The 1920’s – 1930’s

It is unknown when the first passenger aircraft services took place in the United States, but one of the earliest recorded instances was in 1913.

Sular Christofferson transported passengers between San Francisco and Oakland harbours by hydroplane.

Another early instance was in 1914 when passengers were carried from Tampa and St. Petersburg, Florida by a Benoist airboat.

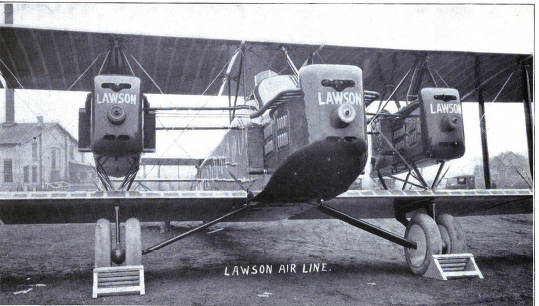

One of the first steps in commercial aviation was the development of the multi-engine airplane by Alfred W. Lawson after WW1.

The Lawson C-2, built in 1919, was created specifically to carry passengers.

Related Article – Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC): 4 Things You Need To Know

The plane was somewhat a failure; the price of military aircraft was much cheaper, so the C-2 was not worth the price to buy.

Lawson went on to build the L-3 and L-4, both larger aircraft that were capable of carrying 34 passengers and up to 6,000 pounds of cargo.

Problems arose once again, this time after the plane crashed on its first flight, causing the development of the L-4 to come to a halt.

In 1920, a Florida entrepreneur by the name of Inglis Uppercu started to offer international flights from Key West, Florida, to Havana, Cuba.

The service was eventually extended to other parts of the country, and there were flights between Miami and the Bahamas, New York and Havana, and the Midwest states of Cleveland, Ohio, and Detroit.

Uppercu’s Aeromarine Airways’ “airborne limousines” were going strong until one crashed off the coast of Florida, resulting in the death of four passengers and the company going out of business in 1924.

One of the big moments in commercial aviation came when mail began to be delivered by air.

In the early 1900s, the common means of transportation for mail was by railroad systems connecting cities in the country.

The first official airmail flight took place in 1918, and it rapidly increased after that.

Related Article – Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP): 4 Things You Need To Know

By 1925, the U.S. Post Office was delivering 14 million pieces of mail per year by airplane.

This new mailing method was especially popular among those in the financial industry who wanted a quicker way to mail checks and documents.

Airmail was eventually transferred to private companies from the government, and the Contract Air Mail Act of 1925, known as the Kelly Act, was sponsored.

The act was the first big step in creating the private U.S. airline industry.

Soon after the establishment of the Kelly Act, the Post Office began to give out contracts to private companies after they bid on certain routes.

This continued to expand for almost a decade, and the private companies went on to become the major transportation players in commercial aviation.

Henry Ford was awarded the Chicago-Detroit and Cleveland-Detroit routes after obtaining the Stout Metal Airplane Company in 1925.

He went on to establish the Ford Air Transport Service, and he developed the “Tin Goose,” an all-metal Ford Trimotor.

Ford was involved in the mailing industry for a short three years before going back to manufacturing.

The government created a national aviation policy in 1926 after President Calvin Coolidge appointed a board headed by Dwight Morrow, a senior partner in J.P. Morgan.

Morrow was not supportive of directly subsidizing airlines.

Instead, he wanted the government to fund a national air transportation system, which was taken up and recommended by Congress in the Air Commerce Act of 1926.

Related Article – 12 Runway Markings and Signs Explained By An Actual Pilot

The act gave a lot of authority to the Secretary of Commerce, who then had a role in the development of air navigation systems, air routes, the licensing of pilots and aircraft, and investigations surrounding accidents.

The Kelly Act was eventually amended by Congress, and the government carriers were paid based on the weight of the mail they were carrying.

These changes played a big role in the financial success of the airlines.

Research and training were also going through changes in the 1920s, especially with the establishment of a foundation by Harry Guggenheim.

His foundation aimed to develop flight instruments and educate aeronautical engineers at universities.

Besides his foundation, Guggenheim was involved in funding the Western Air Express, which included a $180,000 experiment to know if airlines could profit solely from passenger transportation.

The experiment failed after they were not able to make sufficient money without the subsidies.

The Western Air Express experiment was one of many that failed.

This changed in May of 1927 when Charles A. Lindbergh flew solo to Paris.

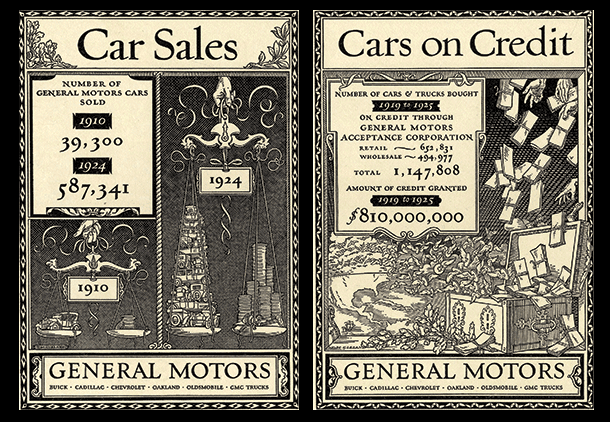

After the successful flight, investors were excited, and aviation stocks tripled between 1927 and 1929.

This helped propel the commercial aviation industry forward.

Even with all of the developments in commercial aviation, passengers could still get to their destination faster by train in the late 1920s.

There were too many limitations with planes compared to trains, which were able to travel through mountains, could run at night, and did not have to land and refuel like aircraft.

On top of that, trains were more comfortable than planes.

Passengers in the air dealt with loud noises, forcing them to put cotton in their ears, and the cabins were un-pressurized.

Despite all of the uncomfortable and limiting aspects of air travel, air travel grew in popularity.

The number of airline passengers in the United States went from less than 6,000 in 1926 to about 173,000 in 1929.

The passengers mostly consisted of businessmen, who increasingly had their tickets paid by employers.

The Ford Trimotor 5-AT, introduced in 1928 and produced through 1932, was popular among most U.S. airlines.

It carried up to 15 passengers, and there was one still being used all the way up until 1991 in Las Vegas.

The aviation industry continued to grow with the creation of jobs, airports, warehouses, aeronautical schools, and new technology.

The first instrument navigation package was used by U.S. Army lieutenant James Doolittle in September 1929.

Related Article – 5 Best Low Time Pilot Jobs With 250 Hours

Research at the Full Flight Laboratory, established by Harry Guggenheim, helped create an extremely accurate barometer, a radio direction beacon to help land, and a Sperry artificial horizon and gyroscope.

These allowed Doolittle to fly 15 miles without having to look outside his cockpit, revolutionary for air travel.

Even with all of the advancements and excitement in commercial aviation during the 1920s, the part of the industry dealing with passenger-only routes failed to make a profit.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that these airlines began to make financial gains.

Aviation in the 1920's

4.5 out of 5 (111 ratings), related articles you might be interested in:.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Vintage photos show how drastically air travel has changed in the last century

- The 1950s are widely known as the golden age of air travel, when flying was a glamorous affair.

- Before that, flights were super loud, cold, and unpressurized.

- Today, flying is all about having the same conveniences we are used to having on the ground.

Air travel has changed significantly over the last century.

From the very first flight in the early 1900s to seat-side, hand-carved hams in the 1950s , to today's touch-screen entertainment systems, air travel has come a long way .

Keep scrolling to see what air travel looked like in every decade.

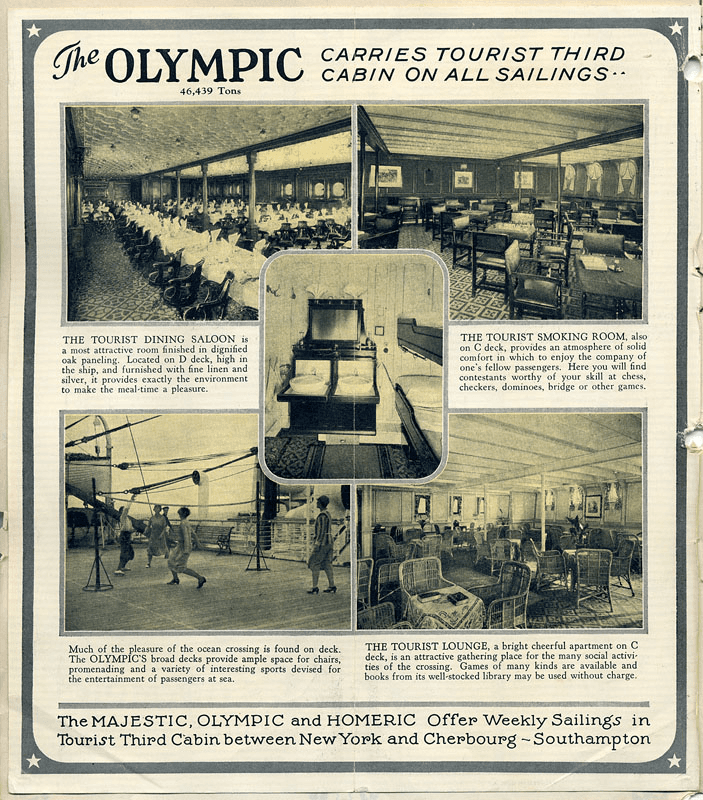

Planes in the 1920s shook loudly and were unpressurized. Air travel was often slower than train travel and only happened during the day.

The 1920s saw the first planes designed exclusively for passengers, according to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum .

Planes during this time usually held fewer than 20 passengers, reached a cruising altitude of 3,000 feet or less, and were slower than traveling by train. Additionally, planes were flying at speeds of around 100 mph, had to stop to refuel often, and could only travel by day, the Metropolitan Airport News reported.

Flying in the 1920s was also an uncomfortable experience for passengers because it was loud and cold, as planes were made of uninsulated sheets of metal that shook loudly in the wind.

Cabins were also completely unpressurized.

Nonetheless, air travel gained in popularity.

Flight attendants were introduced in the 1930s, and traveling by plane generally became more comfortable.

In the 1930s, female flight attendants, then called stewardesses, were first introduced to make flying more comfortable, according to the National Air and Space Museum . Their roles were similar to current-day flight attendants.

However, the first African-American flight attendant, Ruth Carol Taylor, didn't take to the skies until 1958, according to the museum .

Not only was the service better than in the 1920s, but airplanes themselves had become more comfortable. They were soundproofed, heated, and the seats were upholstered, the Metropolitan Airport News reported.

The planes could also fly much higher, reaching a cruising altitude of around 13,000 feet, which reduced turbulence and made travel by aircraft a lot faster (around 200 mph), USA Today reported.

The first pressurized commercial transport aircraft was introduced in 1938, according to the National Air and Space Museum .

In the 1940s, World War II changed commercial air travel.

During World War II, planes were being developed for the purpose of war, rather than commercial flight, Gizmodo reported.

The National Air and Space Museum reported, "Few members of minority groups flew before World War II. But as the economy rapidly expanded and the number of minority-owned businesses increased, more people of color began to fly."

These, however, often faced discrimination, as many airports were segregated at the time, and air travel remained mostly white, Air & Space Magazine reported.

Once the war ended, the US and Europe were left with a lot of planes, as well as large new airbases with long runways, which they repurposed for commercial flight.

New airports were built closer to Europe's main cities, like today's London Heathrow Airport, which was finished in 1946, according to its official website . Transatlantic flights, such as between New York and London, became a daily occurrence, Air & Space Magazine reported.

The 1950s are considered the golden age of air travel. Passengers dressed up and enjoyed inflight meals of prime rib and lobster.

Despite being known as the golden age of air travel, flying in the '50s was not cheap. In fact, a roundtrip flight from Chicago to Phoenix could cost today's equivalent of $1,168 when adjusted for inflation. A one-way flight to Europe could cost more than $3,000 in today's dollars, according to the May 27, 1955 issue of Collier's magazine, as reported by Gizmodo .

Passengers got what they paid for, though. Flying was extremely glamorous: people dressed up, booze was served in fancy glassware, and meals consisted of dishes like roast beef, lobster, and prime rib, The Atlantic reported.

However, while plane cabins were mostly integrated, some US airports were segregated until as late as 1963, Air & Space Magazine reported , despite desegregation efforts having begun in 1948.

Flying was becoming more commonplace in the 1960s, and it was less glamorous than in the previous decade.

Flying became more and more common in the 1960s. Passengers didn't dress up as much as before, though they typically dressed up more than passengers do today.

Passengers flying in the 1960s could also fly without any form of ID, HuffPost reported. That meant that they could just show up at the airport half an hour before departure and walk straight up to the gate.

Even loved ones could walk all the way to the gate without a ticket to send people on their way.

While a couple of exceptions exist, such as the aforementioned flight attendant Ruth Carol Taylor, African Americans were not allowed to work on planes in any capacity until the 1960s, according to the National Air and Space Museum. Marlon D. Green became the first commercial African-American pilot in 1965, paving the way for others.

Security screenings didn't become mandatory until the early 1970s when bigger flights meant more passengers.

Security screenings didn't become mandatory until 1973, and even those were pretty relaxed compared to the airport security we go through today, The Boston Globe reported.

The "Jumbo Jet," or the Boeing 747, opened up the skies for millions of travelers who previously couldn't afford it in 1970, CNN Travel reported. Airlines, now able to fly large numbers of passengers, could sell tickets at a more reasonable price.

Still, there was plenty of legroom and flight attendants catered to passengers' every need.

From 1970 to around 1974, American Airlines even featured a piano lounge in the rear of its 747s, which would be advertised as "the ultimate in informal conviviality in the skies," HuffPost reported.

In the 1980s you could smoke cigarettes on flights, meals were included, and you could check as many bags as you wanted.

Flying saw some fun arrangements in the '80s.

Continental Airlines (now United Airlines) even tested out a "Pub" configuration complete with a bar stocked with alcohol and circular tables surrounded by swivel chairs, Forbes reported.

Passengers could also make a visit to the cockpit during the flight where children were given a commemorative wing pin to remember the experience, USA Today reported.

In the 1990s, passengers could experience inflight entertainment for the first time.

Air travel in the '90s saw the single biggest change up until that point: the slow but inevitable banning of smoking, Condé Nast Traveler reported.

Inflight meals , though not always the tastiest, were also free, seats were outfitted with phones, and inflight entertainment was in its nascent stages.

In the 2000s, 9/11 and other threats significantly changed airport security and what passengers could take in their carry-on luggage.

After 9/11 in 2001, air travel changed drastically.

Before 9/11, the Transportation Security Administration, or TSA, didn't even exist. Travelers could go through security with items including liquids and small pocket knives, and they could wear bulky jackets. Passengers could even keep their shoes on, according to TSA's website .

All that changed after 9/11 and other incidents in the early 2000s — including a foiled plot to detonate liquid explosives on planes departing London, NPR reported – and airport security became much stricter. Cockpit doors were reinforced and locked, and only ticketed travelers were allowed at airline gate areas, NPR reported.

In the 2010s, passengers began to expect the same conveniences on planes they were used to having on the ground.

From private touch-screen TVs to USB chargers in every seat, plane passengers wanted to have all the modern amenities they had on the ground.

However, air travel also began to mean grappling with extra fees for everything from carry-ons to seat assignments, according to Inc. , and free meals were a rarity.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought significant changes to air travel in 2020.

Much changed in air travel in 2020.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic , airlines had to make significant changes for passengers to feel safe and to help slow the spread of COVID-19.

Many airlines blocked middle seats to ensure social distancing, according to Delta , though most resumed offering the seats around December 2020.

Several airlines also stopped serving food and drinks on flights or served them in little plastic baggies dispensed upon boarding.

All domestic airlines finally stopped requiring passengers to wear masks in April 2022, Forbes reported.

In 2023, summer air travel ramped up once again, surpassing pre-pandemic levels, according to the TSA, and as reported by Forbes . Airline revenues also inched back near record levels, The Guardian reported.

- Main content

Birth of Aviation

The history of commercial aviation, first u.s. passenger airliners.

Western Air Express’s success would be followed by that of other CAM carriers, many of whom would also go on to become major players in the airline industry including CAM-5 carrier Varney Airlines (which would later be acquired by Boeing and eventually merged with United Airlines) and CAM-2 carrier Robertson Aircraft Corporation with chief pilot Charles Lindbergh (which would become American Airlines, currently the largest airline in the world).

Below is a list of some of the earliest known U.S. passenger airliners leading up to the first passenger flight of Western Air Express in 1926, which began what is claimed to be the first “year-round overland passenger airline transportation service” in the United States:

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Sweepstakes

- Travel Tips

What Travel Looked Like Through the Decades

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/maya-kachroo-levine-author-pic-1-2000-1209fcfd315444719a7906644a920183.jpg)

Getting from point A to point B has not always been as easy as online booking, Global Entry , and Uber. It was a surprisingly recent event when the average American traded in the old horse-and-carriage look for a car, plane, or even private jet .

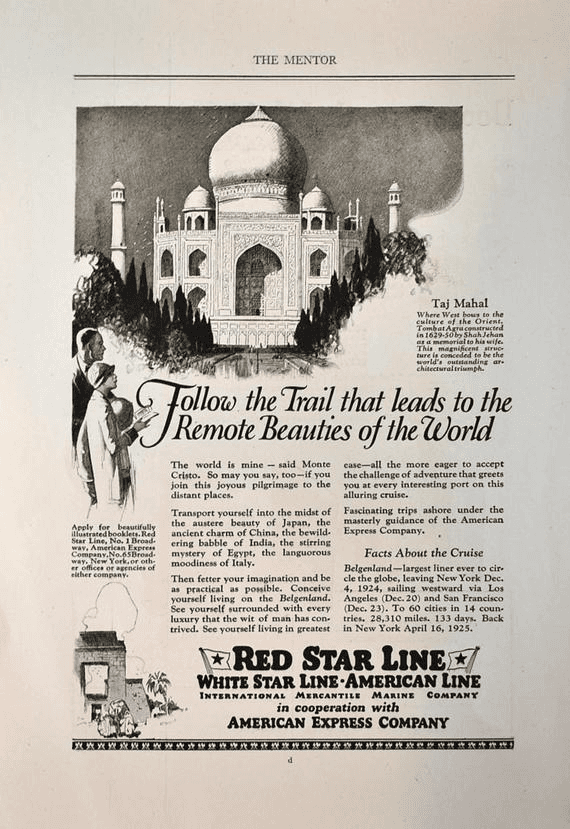

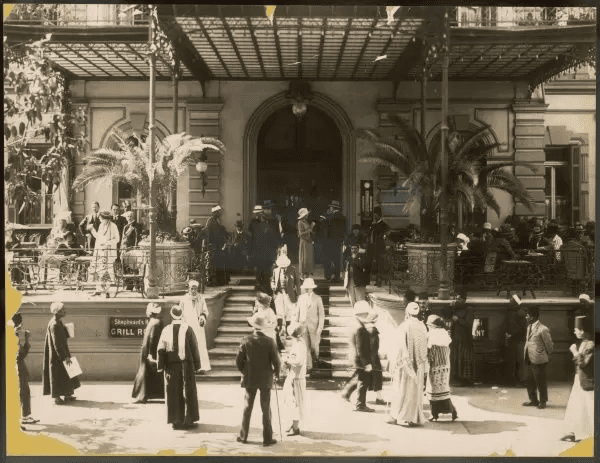

What was it like to travel at the turn of the century? If you were heading out for a trans-Atlantic trip at the very beginning of the 20th century, there was one option: boat. Travelers planning a cross-country trip had something akin to options: carriage, car (for those who could afford one), rail, or electric trolley lines — especially as people moved from rural areas to cities.

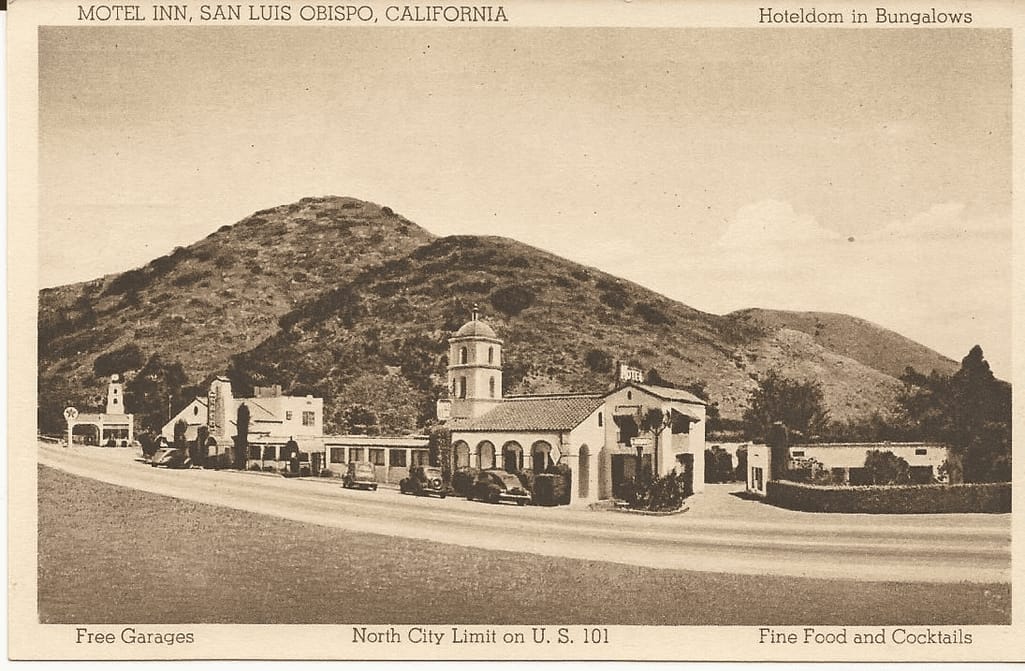

At the beginning of the 1900s, leisure travel in general was something experienced exclusively by the wealthy and elite population. In the early-to-mid-20th century, trains were steadily a popular way to get around, as were cars. The debut regional airlines welcomed their first passengers in the 1920s, but the airline business didn't see its boom until several decades later. During the '50s, a huge portion of the American population purchased a set of wheels, giving them the opportunity to hit the open road and live the American dream.

Come 1960, airports had expanded globally to provide both international and domestic flights to passengers. Air travel became a luxury industry, and a transcontinental trip soon became nothing but a short journey.

So, what's next? The leisure travel industry has quite a legacy to fulfill — fancy a trip up to Mars , anyone? Here, we've outlined how travel (and specifically, transportation) has evolved over every decade of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The 1900s was all about that horse-and-carriage travel life. Horse-drawn carriages were the most popular mode of transport, as it was before cars came onto the scene. In fact, roadways were not plentiful in the 1900s, so most travelers would follow the waterways (primarily rivers) to reach their destinations. The 1900s is the last decade before the canals, roads, and railway plans really took hold in the U.S., and as such, it represents a much slower and antiquated form of travel than the traditions we associate with the rest of the 20th century.

Cross-continental travel became more prevalent in the 1910s as ocean liners surged in popularity. In the '10s, sailing via steam ship was the only way to get to Europe. The most famous ocean liner of this decade, of course, was the Titanic. The largest ship in service at the time of its 1912 sailing, the Titanic departed Southampton, England on April 10 (for its maiden voyage) and was due to arrive in New York City on April 17. At 11:40 p.m. on the evening of April 14, it collided with an iceberg and sank beneath the North Atlantic three hours later. Still, when the Titanic was constructed, it was the largest human-made moving object on the planet and the pinnacle of '10s travel.

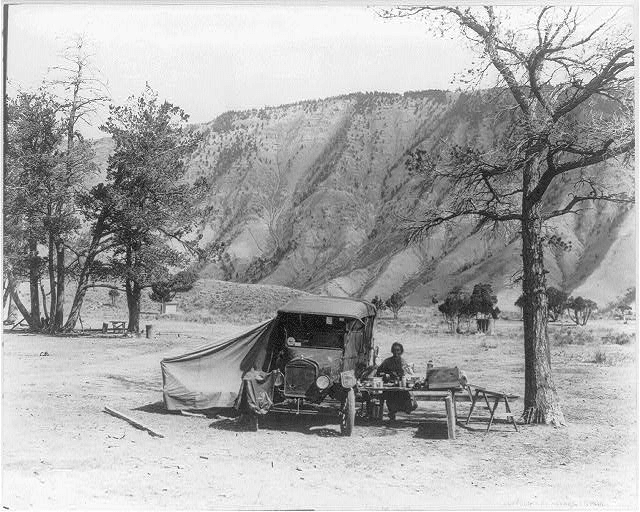

The roaring '20s really opened our eyes up to the romance and excitement of travel. Railroads in the U.S. were expanded in World War II, and travelers were encouraged to hop on the train to visit out-of-state resorts. It was also a decade of prosperity and economic growth, and the first time middle-class families could afford one of the most crucial travel luxuries: a car. In Europe, luxury trains were having a '20s moment coming off the design glamour of La Belle Epoque, even though high-end train travel dates back to the mid-1800s when George Pullman introduced the concept of private train cars.

Finally, ocean liners bounced back after the challenges of 1912 with such popularity that the Suez Canal had to be expanded. Most notably, travelers would cruise to destinations like Jamaica and the Bahamas.

Cue "Jet Airliner" because we've made it to the '30s, which is when planes showed up on the mainstream travel scene. While the airplane was invented in 1903 by the Wright brothers, and commercial air travel was possible in the '20s, flying was quite a cramped, turbulent experience, and reserved only for the richest members of society. Flying in the 1930s (while still only for elite, business travelers) was slightly more comfortable. Flight cabins got bigger — and seats were plush, sometimes resembling living room furniture.

In 1935, the invention of the Douglas DC-3 changed the game — it was a commercial airliner that was larger, more comfortable, and faster than anything travelers had seen previously. Use of the Douglas DC-3 was picked up by Delta, TWA, American, and United. The '30s was also the first decade that saw trans-Atlantic flights. Pan American Airways led the charge on flying passengers across the Atlantic, beginning commercial flights across the pond in 1939.

1940s & 1950s

Road trip heyday was in full swing in the '40s, as cars got better and better. From convertibles to well-made family station wagons, cars were getting bigger, higher-tech, and more luxurious. Increased comfort in the car allowed for longer road trips, so it was only fitting that the 1950s brought a major expansion in U.S. highway opportunities.

The 1950s brought the Interstate system, introduced by President Eisenhower. Prior to the origination of the "I" routes, road trippers could take only the Lincoln Highway across the country (it ran all the way from NYC to San Francisco). But the Lincoln Highway wasn't exactly a smooth ride — parts of it were unpaved — and that's one of the reasons the Interstate system came to be. President Eisenhower felt great pressure from his constituents to improve the roadways, and he obliged in the '50s, paving the way for smoother road trips and commutes.

The '60s is the Concorde plane era. Enthusiasm for supersonic flight surged in the '60s when France and Britain banded together and announced that they would attempt to make the first supersonic aircraft, which they called Concorde. The Concorde was iconic because of what it represented, forging a path into the future of aviation with supersonic capabilities. France and Britain began building a supersonic jetliner in 1962, it was presented to the public in 1967, and it took its maiden voyage in 1969. However, because of noise complaints from the public, enthusiasm for the Concorde was quickly curbed. Only 20 were made, and only 14 were used for commercial airline purposes on Air France and British Airways. While they were retired in 2003, there is still fervent interest in supersonic jets nearly 20 years later.

Amtrak incorporated in 1971 and much of this decade was spent solidifying its brand and its place within American travel. Amtrak initially serviced 43 states (and Washington D.C.) with 21 routes. In the early '70s, Amtrak established railway stations and expanded to Canada. The Amtrak was meant to dissuade car usage, especially when commuting. But it wasn't until 1975, when Amtrak introduced a fleet of Pullman-Standard Company Superliner cars, that it was regarded as a long-distance travel option. The 235 new cars — which cost $313 million — featured overnight cabins, and dining and lounge cars.

The '80s are when long-distance travel via flight unequivocally became the norm. While the '60s and '70s saw the friendly skies become mainstream, to a certain extent, there was still a portion of the population that saw it as a risk or a luxury to be a high-flyer. Jetsetting became commonplace later than you might think, but by the '80s, it was the long-haul go-to mode of transportation.

1990s & 2000s

Plans for getting hybrid vehicles on the road began to take shape in the '90s. The Toyota Prius (a gas-electric hybrid) was introduced to the streets of Japan in 1997 and took hold outside Japan in 2001. Toyota had sold 1 million Priuses around the world by 2007. The hybrid trend that we saw from '97 to '07 paved the way for the success of Teslas, chargeable BMWs, and the electric car adoption we've now seen around the world. It's been impactful not only for the road trippers but for the average American commuter.

If we're still cueing songs up here, let's go ahead and throw on "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous," because the 2010s are when air travel became positively over-the-top. Qatar Airways rolled out their lavish Qsuites in 2017. Business class-only airlines like La Compagnie (founded in 2013) showed up on the scene. The '10s taught the luxury traveler that private jets weren't the only way to fly in exceptional style.

Of course, we can't really say what the 2020 transportation fixation will be — but the stage has certainly been set for this to be the decade of commercial space travel. With Elon Musk building an elaborate SpaceX rocket ship and making big plans to venture to Mars, and of course, the world's first space hotel set to open in 2027 , it certainly seems like commercialized space travel is where we're headed next.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Ellie-Nan-Storck-00d7064c4ef24a22a8900f0416c31833.jpeg)

Air Travel in the 1920s

Farm history portal, 1920's, 1930's.

- Introduction

- Accidents & Illnesses

- Building the Lines

- Bringing Electricity

- Changing Farm Work

- Changing Rural Homes

- Community Churches

- Diversity In Religion

- Family Time

- Feeding The Family

- Flour Sack Clothes

- Going To School

- Impact of the REA

- Indoor Plumbing

- Migration Out

- Migration In

- Prohibition Of Alcohol

- School Days

- School Programs

- Surviving The Weather

- Who Lived In York Co.?

- Tractored Out

- Technological Advances

- Picking Corn

- Harvesting Wheat

- Cultivating

- Animal Hybrids

- Conservation

- Contour Plowing

- Crop Rotation

- Cropping Patterns

- Culling The Herds

- Different Breeds, Purposes

- Fertilizers

- Henry A. Wallace

- Henry Beachell

- Hybrid Crops

- Planting & Harvesting

- Selective Breeding

- Shelterbelts

- The Science Of Hybrids

- Worldwide Depression

- Wall Street to RFD

- What Followed The Crash

- Burning Corn for Fuel

- Couldn’t Even Buy a Job

- RFD to Main Street

- Foreclosures

- Penny Auctions

- Radical Farm Protests

- Barter Economies

- New Financial Laws

- WPA Arts Projects

- SSA, the Social Security Administration

- The Politics Of The REA

- Political Attitudes

- A 1930s Balance Sheet

- Depression Legacy

- Backlash – The FDA

- Early Pesticides

- Grasshoppers are Coming

- Calling Off School

- Farm Numbers Decline

- FSA CO-OP Farmsteads

- Fsa Photographers

- Groundwater Irrigation

- Hitchhiking

- Irrigation Techniques

- Kingsley Dam

- New Deal Farm Laws

- No Water, No Crops

- Riding The Rails

- Surface Water Irrigation

- The Dust Bowl

- World Events

1940's

- Building Bombs & Planes

- Canteens Greet Gis

- Changes In Eating Habits

- Civil Rights For Minorities

- Conscientious Objectors

- Enlistments & The Draft

- Internment In America

- K-12 & Consolidation

- Land Grant Universities

- Local Sports

- Minorities On Base

- More Rights For Women

- Nisei Invade … Nebraska

- Normal Life & War Brides

- Pop Culture At War

- Postwar Food & Fun

- REA Promise Fulfilled

- Rural Bases

- Rural Medicine

- Strains on Rural Housing

- The Blizzard Of ’49

- The GI Bill

- The Home Front

- TV Turns On

- War Stories

- Fertilizing

- A Jeep Is A Jeep, Right?

- Allis Chalmers Tractors

- Case Tractors

- Cultivators

- Fixing Machinery

- Ford-Ferguson Tractors

- Horses Lose Their Jobs

- John Deere Tractors

- Haying Equipment

- IH Farmall Tractors

- Postwar Technology

- REA In The Field & Barn

- Self-Propelled Combines

- Surplus Everywhere

- Tractor Innovations

- Berlin Airlift

- Co-ops Expand

- Economic Boom

- Exports & Imports

- Food For Peace

- Food For War

- Information Age Begins

- Labor Shortages

- POWs Work The Fields

- Rural Banking

- The Marshall Plan

- Transportation

- UNRRA & Private Relief

- Antibiotics & Additives

- Barns – Functions & Forms

- Breeding & Insemination

- Changing Crops, Soybeans

- Fertilizer Explodes

- Hybrids, Fertilizer & Irrigation

- Livestock Grows

- Storing The Bounty

- Veterinary Medicine

- Victory Gardens

- Aerial Crop Dusting

- Biological Controls

- Delta Airlines

- Herbicides, 2,4-D +

- Insecticides, DDT +

- Pesticide Regulations

1950's & 1960's

- Duck & Cover

- Fallout Shelter For Cows

- Frozen Foods

- Life Goes On

- Living At Ground Zero

- Planting Fields of ICBMS

- Protests at Home

- RURAL AM. EDUCATION

- Shrinking Farm Numbers

- The Extension Service

- Vietnam War

- Watching an A-bomb

- Harvest Technology

- Allis-Chalmers Tractors

- Corn Combines

- Cotton Harvesting

- Ford Tractors

- From Barns To Behlen Buildings

- J. I. Case Tractors

- Massey-Harris becomes Massey-ferguson

- Minimum Tillage Changes Planters & Cultivators

- Other Tractors In The 1950s And 60s

- Tractor Pulling

- Ag Lobbies Washington

- Agribusiness

- Farm Families Going To The City

- Farmers Teach Wall Street Futures

- Farming For The Government

- Food Stamps

- IBP & Boxed Beef

- Ike’s Farm Programs

- JFK’s Farm Programs

- Johnson’s Farm Programs

- Supermarkets Dominate

- The Rise & Fall Of The Omaha Stockyards

- Truman’s Farm Program

- Planter Technology

- DDT is Banned and Earth Day Begins

- Multiple Choices

- Silent Spring & The Environmental Movement

- The Environmental Movement Begins

- The Insect Challenge

- Center Pivots Take Over

- Connections Between Surface And Groundwater

- Exporting Water

- First Pivots Installed

- How Pivots Work

- Making Circles Into Squares

- Nebraska’s Unique Natural Resource Districts

- Other Center Pivot Innovators

- Robert Daugherty & Valmont

- State To State Water Agreements

- The 1950s Worldwide Boom In Irrigation

- Valmont’s Center Pivot Patent Runs Out

1970's - Today

- Farming in the 70s to Today

- City Problems Come Home

- Internet Connections

- A Nation of Immigrants

- Language, Ed. & Culture

- The New Wave

- The Political Debate

- Rural Pop Culture

- Rural Recruits

- “Average” Farmers

- Declining Towns

- Raising Kids

- Future Sources Of Ethanol

- Changes in the Meat Industry

- Crops & Climate Change

- Global Production Of Ethanol

- Grown Up Fertilizer Industry

- Organic Farming

- Bt & Roundup Ready Crops

- “Pharm” Animals & Plants

- The GMO Backlash

- The Green Revolution Phase II

- Afghan Boycott

- Foreclosures & Bank Failures

- Farm Strike

- Food Price Hikes

- An End to Agricultural Subsidies?

- New Agricultural Markets

- Women on the Farm

- Climate Change

- Computers as a Tool

- Tillage Technology

- Other Tractor Manufacturers

- AGCO Tractors

- CLAAS Tractors

- CNH, Case New Holland Tractors

- Partial Bibliography

- Chemical Companies Buy Seed Companies

- Insecticides – DDT’s Rise, Fall & Rise Again

- The Herbicide 2, 4-D

- How Herbicides Work

- Organic Agriculture & Pesticides

- The EPA, The Endangered Species Act & Pesticides

- Cycles Of Drought

- The End Of Dams For Surface Irrigation

- Paying Farmers to Not Irrigate

- Global Warming Research Heats Up

A young Charles Lindbergh was trained in Lincoln and later became the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic ocean.

In 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh, “Lucky Lindy,” flew nonstop from New York to Paris, completing the world’s first solo transatlantic flight. Lindbergh learned to fly at Ray Page’s Flying School in Lincoln, Nebraska. Before his transatlantic flight in “The Spirit of St. Louis,” Lindbergh was a barnstormer, flying from town to town and astounding rural residents with aerial acrobatics, such as loops, rolls, spins, dives, walking on the wings, and parachute jumping. Barnstormers dropped leaflets and buzzed small towns to draw a crowd for the next air show. Many people in Nebraska were impressed by the acrobatics, and some even paid $5 each for a plane ride. Air mail postal service started on the East Coast in 1918 and in 1921 expanded to California. The decade of the 1920s saw increased use of airplanes for mail, passenger, and freight service. Fourteen domestic airlines were founded in 1926.

Charles Lindbergh’s airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis.

Start exploring now by clicking on one of these seven sections.

Farm Life / Water / Crops / Making Money / Machines / Pests & Weeds / World Events

Little you care for vows that you made. Little you care how much I have paid. My heart is aching, My heart is breaking, For somebody’s taking my place.

They call… no date. I promised you I’d wait. I want them all to know I’m strictly single, oh.

I’ll walk alone because to tell you the truth I’ll be lonely, I don’t mind being lonely when my heart tells me you are lonely too. I’ll walk alone, they’ll ask me why and I’ll tell them I’d rather. There are dreams I must gather, dreams we fashioned the night you held me tight.

I’ll always be near you wherever you are, each night in every prayer. Just whisper, I’ll hear you, no matter how far. So, close your eyes and I’ll be there. Please walk alone, but send your love and your kisses to guide me. Till you’re walking beside me, I’ll walk alone. Darling, all by myself, I’ll walk alone.

Lyrics by Sammy Cahn, music by Jule Styne. Also featured in the film “Follow The Boys” (1944).

Dinah Shore was born as Fanny Shore in Tennessee and raised in Nashville where she began singing at a nightclub at age 14. When she was attending local Vanderbilt University, she paid for school by singing on radio station WSM. Her program was called “Our Little Cheerleader of Song.” For her theme song, she chose the blues standard “Dinah” popularized by Ethel Waters. After graduation, she moved in New York in 1938 where a flustered radio announcer called her Dinah. The name stuck. She made it big when Eddie Cantor hired her for his radio show. That was followed by a string of hits, her own radio show, movies and, in 1951, the first of a series of television talk shows. She died in 1994.

The captains of aircraft walked out. I noticed that the big Canadian with the slow, easy grin had printed “Berlin” at the top of his pad and then embellished it with a scroll. The red-headed English boy with the two-weeks’-old mustache was the last to leave the room.

Late in the afternoon we went to the locker room to draw parachutes, Mae Wests [lifevests] and all the rest. As we dressed, a couple of Australians were whistling. Walking out to the bus that was to take us to the aircraft, I heard the station loudspeakers announcing that that evening all personnel would be able to see a film: Star-Spangled Rhythm. Free.

We went out and stood around the big, black four-motored Lancaster, “D for Dog.” A small station wagon delivered a thermos bottle of coffee, chewing gum, an orange, and a bit of chocolate for each man. Up in that part of England the air hums and throbs with the sound of aircraft motors all day, but for half an hour before takeoff the skies are dead, silent and expectant. A lone hawk hovered over the airfield, absolutely still as he faced into the wind. Jack, the tail gunner, said, “It’d be nice to fly like that.” D-Dog eased around the perimeter track to the end of the runway. We sat there for a moment. The green light flashed and we were rolling … ten seconds ahead of schedule.

The takeoff was as smooth as silk. The wheels came up, and D-Dog started the long climb. As we came up through the clouds, I looked right and left and counted fourteen black Lancasters climbing for the place where men must burn oxygen to live. The sun was going down and its red glow made rivers and lakes of fire on the top of the clouds. Down to the southward, the clouds piled up to form castles, battlements, and whole cities, all tinged with red.

Soon we were out over the North Sea. Dave, the navigator, asked Jock if he couldn’t make a little more speed. We were nearly two minutes late. By this time, we were all using oxygen. The talk on the intercom was brief and crisp. Everyone sounded relaxed. For a while, the eight of us in our little world of exile moved over the sea. There was a quarter moon on the starboard beam and Jock’s quiet voice came through the intercom, “That’ll be flak ahead.” We were approaching the enemy coast. The flak looked like a cigarette lighter in a dark room: one that won’t light – sparks but no flame – the sparks crackling just above the level of the cloud tops. We flew steady and straight, and soon the flak was directly below us. D-Dog rocked a little from right to left, but that wasn’t caused by the flak. We were in the slipstream of other Lancasters ahead, and we were over the enemy coast. Then a strange thing happened. The aircraft seemed to grow smaller. Jack in the rear turret, Wally the mid-upper gunner, Titch the wireless operator, all seemed somehow to draw closer to Jock in the cockpit. It was as though each man’s shoulder was against the others. The understanding was complete. The intercom came to life, and Jock said, “Two aircraft on the port beam.” Jack in the tail said, “Okay, sir. They’re Lancs.” The whole crew was a unit and wasn’t wasting words.

The cloud below was ten-tenths. The blue-green jet of the exhausts licked back along the wing, and there were other aircraft all around us. The whole great aerial armada was hurtling toward Berlin. We flew so for twenty minutes, when Jock looked up at a vapor trail curling above us, remarking in a conversational tone that, from the look of it, he thought there was a fighter up there. Occasionally the angry red of ack-ack burst through the clouds, but it was far away, and we took only an academic interest. We were flying in the third wave.

Jock asked Wally in the mid-upper turret, and Jack in the rear, if they were cold. They said they were all right and thanked him for asking. He even asked how I was and I said, “All right so far.” The cloud was beginning to thin out. Off to the north we could see lights, and the flak began to liven up ahead of us. Buzz, the bomb-aimer, crackled through on the intercom, “There’s a battle going on over on the starboard beam.” We couldn’t see the aircraft, but we could see the jets of red tracer being exchanged. Suddenly, there was a burst of yellow flame and Jock remarked, “That’s the fighter going down. Note the position.” The whole thing was interesting, but remote. Dave, the navigator, who was sitting back with his maps, charts and compasses, said, “The attack ought to begin in exactly two minutes.” We were still over the clouds.

But suddenly those dirty gray clouds turned white and we were over the outer searchlight defenses. The clouds below us were white, and we were black. D-Dog seemed like a black bug on a white sheet. The flak began coming up, but none of it close. We were still a long way from Berlin. I didn’t realize just how far. Jock observed, “There’s a kite on fire dead ahead.” It was a great, golden, slow-moving meteor slanting toward the earth. By this time we were about thirty miles from our target area in Berlin. That thirty miles was the longest flight I have ever made.

Dead on time, Buzz the bomb-aimer reported, “Target indicators going down.” At the same moment, the sky ahead was lit up by bright yellow flares. Off to starboard another kite went down in flames. The flares were sprouting all over the sky, reds and greens and yellows, and we were flying straight for the center of the fireworks. D-Dog seemed to be standing still, the four propellers thrashing the air, but we didn’t seem to be closing in. The clouds had cleared, and off to the starboard a Lanc was caught by at least fourteen searchlight beams. We could see him twist and turn and finally break out. But still, the whole thing had a quality of unreality about it. No one seemed to be shooting at us, but it was getting lighter all the time. Suddenly, a tremendous big blob of yellow light appeared dead ahead; another to the right and another to the left. We were flying straight for them.

Jock pointed out to me the dummy fires and flares to right and left, but we kept going in. Dead ahead there was a whole chain of red flares looking like stoplights. Another Lanc was coned on our starboard beam. The lights seemed to be supporting it. Again we could see those little bubbles of colored lead driving at it from two sides. The German fighters were at him. And then, with no warning at all, D-Dog was filled with an unhealthy white light.

I was standing just behind Jock and could see all the seams on the wings. His quiet Scots voice beat in my ears, “Steady lads, we’ve been coned.” His slender body lifted half out of the seat as he jammed the control column forward and to the left. We were going down. Jock was wearing woolen gloves with the fingers cut off. I could see his fingernails turn white as he gripped the wheel. And then I was on my knees, flat on the deck, for he had whipped the Dog back into a climbing turn. The knees should have been strong enough to support me, but they weren’t, and the stomach seemed in some danger of letting me down too. I picked myself up and looked out again. It seemed that one big searchlight, instead of being twenty thousand feet below, was mounted right on our wingtip. D-Dog was corkscrewing. As we rolled down on the other side, I began to see what was happening to Berlin.

The clouds were gone, and the sticks of incendiaries from the preceding waves made the place look like a badly laid-out city with the streetlights on. The small incendiaries were going down like a fistful of white rice thrown on a piece of black velvet. As Jock hauled the Dog up again, I was thrown to the other side of the cockpit. And there below were more incendiaries, glowing white and then turning red. The cookies, the four-thousand-pound high explosives, were bursting below like great sunflowers gone mad. And then, as we started down again, still held in the lights, I remembered that the Dog still had one of those cookies and a whole basket of incendiaries in his belly, and the lights still held us, and I was very frightened.

While Jock was flinging us about in the air, he suddenly yelled over the intercom, “Two aircraft on the port beam.” I looked astern and saw Wally, the mid-upper, whip his turret around to port, and then looked up to see a single-engine fighter slide just above us. The other aircraft was one of ours. Finally, we were out of the cone, flying level. I looked down, and the white fires had turned red. They were beginning to merge and spread, just like butter does on a hot plate. Jock and Buzz, the bomb-aimer, began to discuss the target. The smoke was getting thick down below. Buzz said he liked the two green flares on the ground almost dead ahead. He began calling his directions. Just then a new bunch of big flares went down on the far side of the sea of flame that seemed to be directly below us. He thought that would be a better aiming point. Jock agreed and we flew on.

The bomb doors were opened. Buzz called his directions: “Five left, five left.” And then, there was a gentle, confident upward thrust under my feet and Buzz said, “Cookie gone.” A few seconds later, the incendiaries went, and D-Dog seemed lighter and easier to handle.

I thought I could make out the outline of streets below, but the bomb-aimer didn’t agree, and he ought to know. By this time, all those patches of white on black had turned yellow and started to flow together. Another searchlight caught us but didn’t hold us. Then, through the intercom came the word, “One can of incendiaries didn’t clear. We’re still carrying it.” And Jock replied, “Is it a big one or a little one?” The word came back: “Little one I think, but I’m not sure. I’ll check.” Finally, the intercom announced that it was only a small container of incendiaries left, and Jock remarked, “Well, it’s hardly worth going back and doing a run up for that.” If there had been a good fat bundle left, he would have gone back through that stuff and done it all over again. I began to breathe, and to reflect again, that all men would be brave if only they could leave their stomachs at home. Then there was a tremendous whoomph, an unintelligible shout from the tail gunner, and D-Dog shivered and lost altitude. I looked to the port side and there was a Lancaster that seemed close enough to touch. He had whipped straight under us; missed us by twenty-five, fifty feet, no one knew how much.

The navigator sang out the new course and we were heading for home. Jock was doing what I had heard him tell his pilots to do so often – flying dead on course. He flew straight into a huge green searchlight, and as he rammed the throttles home he remarked, “We’ll have a little trouble getting away from this one.” Again D-Dog dove, climbed and twisted, and was finally free. We flew level then. I looked on the port beam at the target area. There was a red, sullen, obscene glare. The fires seemed to have found each other … and we were heading home.

For a little while it was smooth sailing. We saw more battles. Then another plane in flames, but no one could tell whether it was ours or theirs. We were still near the target. Dave, the navigator said, “Hold her steady, skipper. I want to get an astral sight.” Jock held her steady. And the flak began coming up at us. It seemed to be very close. It was winking off both wings, but the Dog was steady. Finally, Dave said, “Okay, skipper. Thank you very much.” A great orange blob of flak smacked up straight in front of us, and Jock said “I think they’re shooting at us.” I’d thought so for some time. He began to throw D for Dog up, around, and about again. When we were clear of the barrage, I asked him how close the bursts were and he said, “Not very close. When they’re really near, you can smell ’em.” That proved nothing for I’d been holding my breath.

Jack sang out from the rear turret that his oxygen was getting low; he thought maybe the lead had frozen. Titch the wireless operator went scrambling back with a new mask and a bottle of oxygen. Dave said, “We’re crossing the coast.” My mind went back to the time I had crossed that coast in 1938, in a plane that had taken off from Prague. Just ahead of me sat two refugees from Vienna – an old man and his wife. The copilot came back and told them that we were outside German territory. The old man reached out and grasped his wife’s hand. The work that was done last night was a massive blow of retribution, for all those who have fled from the sound of shots and blows on a stricken continent.

We began to lose height over the North Sea. We were over England’s shores. The land was dark beneath us. Somewhere down there below, American boys were probably bombing up Fortresses and Liberators, getting ready for the day’s work. We were over the home field. We called the control tower and the calm, clear voice of an English girl replied, “Greetings D-Dog. You are diverted to Mulebag.” We swung round, contacted Mulebag, came in on the flare path, touched down very gently, ran along to the end of the runway and turned left. And Jock, the finest pilot in Bomber Command, said to the control tower, “D-Dog clear of runway.”

When we went in for interrogation, I looked on the board and saw that the big, slow-smiling Canadian and the red-headed English boy with the two-weeks’-old moustache hadn’t made it. They were missing.

There were four reporters on this operation. Two of them didn’t come back. Two friends of mine, Norman Stockton of Australian Associated Newspapers, and Lowell Bennett, an American representing International News Service. There is something of a tradition amongst reporters, that those who are prevented by circumstances from filing their stories will be covered by their colleagues. This has been my effort to do so. In the aircraft in which I flew, the men who flew and fought poured into my ears their comments on fighters, flak, and flares in the same tone that they would have used in reporting a host of daffodils. I have no doubt that Bennett and Stockton would have given you a better report of last night’s activity.

Berlin was a thing of orchestrated Hell – a terrible symphony of light and flames. It isn’t a pleasant kind of warfare – the men doing it speak of it as a job. Yesterday afternoon, when the tapes were stretched out on the big map all the way to Berlin and back again, a young pilot with old eyes said to me, “I see we’re working again tonight.” That’s the frame of mind in which the job is being done. The job isn’t pleasant; it’s terribly tiring. Men die in the sky while others are roasted alive in their cellars. Berlin last night wasn’t a pretty sight. In about 35 minutes it was hit with about three times the amount of stuff that ever came down on London in a night-long blitz. This is a calculated, remorseless campaign of destruction. Right now the mechanics are probably working on D-Dog, getting him ready to fly again.

Source: Library of Congress, Milo Ryan Phonoarchive tapes 774-775

“I left here in York, went to Hebron. That was the induction station. From Hebron I went to Pawnee City and in Pawnee City, that’s where we stayed. I was right there on the fairgrounds. There was barracks and everything made there. And what we done – the farmer, all he done was paid for the fence posts and barbwire. We would put it up for him. And that’s, [we] stayed in that.

“But we didn’t have any money. You got paid $15 for the month. Ten of it went home so the folks could have 10 dollars to spend in cash because Dad was on unemployment. And five dollars was all I got for a month. If you smoked, you had to buy your shaving cream and everything out of that five dollars. Now you take five dollars, you buy yourself shaving cream and smoking and see if you can do that nowadays. But we bought them big sacks of Golden Grain [tobacco], rolled our own cigarettes and used hand soap that was in the latrine and that’s what we shaved with. Cause you didn’t have any money. “Oh, it wasn’t bad. I mean, you got the barracks and it was just like being in the service. The only thing is, in the service you had to be taught you know, how to kill people and carry a gun, take care of your gun. There, you went out on the farms and dug in fence posts and stuff like that. It was hard work. You dig them holes. You set the post. Then run the roll of barbwire, stretch it in there. Sometimes it was woven wire fence to keep the hogs in. No, that’s – it was hard work. But nobody seemed to complain down there, because you had a place to sleep, a place to eat – which was pretty skimpy a lot of times at home. So, no, I never complained about it.”

Alvin and Delbert Apetz are first generation Americans. Their father, Carl, immigrated from Germany in 1909. Alvin is the oldest. Both kids worked on their dad’s farm until he lost it in the 1930s, Alvin worked in the National Youth Administration and Delbert joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. Both brothers were in the military during World War II. Alvin fought in Germany even though he still had relatives over there. Delbert was drafted towards the end of the war. After the war, Alvin worked construction and Delbert worked for the York Dairy and in construction. Delbert died in 2005.

“Most of them went [into the program]. There was just a few that wouldn’t have anything to do with it. But, the majority of people, they all went into the program… There’s a few that said, ‘The government isn’t going to tell me what to do.’ There was a few of them. Now, I don’t think there was too many. They didn’t want the government to tell them what to do. That’s the whole story. You had to abide by their rules. If you had to leave 10 acres out, they came out and measured it, and checked it, and checked you out.”

LeRoy Hankel was raised on a farm and spoke German in the home. He only learned English after he went to school. He started farming for himself in 1937 renting ground for years until he could buy his own land in 1948. That was also the first year they had indoor plumbing. He and his wife Blondina had five children. Later, LeRoy served as an assessor for York county for 13 years. LeRoy passed on in 2005.

“Well, the improvement in the seeds is one [big change in agriculture]. And REA is one. That sure changed the farm life. And the improvement in the seeds. And of course, some of this farm machinery now is just massive. It’s so different than what it used to be. This multi-row – 12-row, 16-row – when I first started working in the shop, they used to list corn one row at a time with a hard ground lister behind three head of horses. One row at a time! And that was just the way a horse would plod. Now, they have these big tractors, what, maybe eight miles an hour, maybe even more.

Yeah, 12-rows, 16 – however many rows they have. That is why the farms have become bigger in acreage, too. They can handle it. But there’s another reason for that. Just in recent weeks, there’s been an article in the State Journal about the trouble that some farmers are getting into. Young farmers, they’ve spent maybe 20 years farming, they’re in their 40s, and they have to give it up. Because when they go to their banker their banker says, ‘Well, you’re not big enough.’ If you’re not farming a thousand acres and see the possibility of farming 12- or 13-hundred acres five years down the road, the banker frowns on that. He wants to see that expansion. He wants to see that increase in size.

“That’s one of the changes that takes place. You know, there was a time when the farmer, when he went to town behind horses with a buggy or wagon, he was almost compelled to go to his nearest small town, his nearest town. Now, he goes out and he sits down in his car. He can go any distance he wants to, in any direction of the compass that he wants to, 20, 30 miles. That’s one of the things that’s contributed to the decline of the small town. They have a wider choice. And the larger businesses are competition that the small town just can’t meet. It’s difficult for them to meet it. Only the exception ever meets it.

“In Gresham, our main street in Gresham was pretty well filled with buildings at that time. And there was a business in each building. And at that time, the people that lived in Gresham, most of the people that lived in Gresham, in the morning they’d get up and go downtown into their business in the main street of Gresham. Now, of course, that Gresham main street has dried up. There isn’t much there anymore. There’s a bank and a post office and a beer tavern and an insurance agency. And that just about winds it up. So, the people that live in Gresham now, they live in Gresham, it’s a bedroom community, but they work elsewhere.”

Walter Schmitt is a first generation American. His father was immigrated from Germany and his mother from Czechoslovakia. He grew up in his father’s blacksmith shop in Gresham, Nebraska. He graduated from high school in 1930 and went to work with his father. After his father died, he kept the shop open until his health failed in the early 1990s. Walter passed on in 2008 and left over $3.5 million to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln for scholarships.

Question: “And what did your husband say?”

Carla Due was born in Denmark. Her parents emigrated to Nebraska when she was about two years old, but they decided the trip would be too dangerous for Carla. She grew up with her grandparents. When she was about 10 or 12 her folks tried twice to get her to come to the U.S. but she resisted. Finally, when she was 16 she crossed the Atlantic alone on a ship. She helped her parents farm, learned English, met her husband Bernard at a dance and then helped him farm.

“Well, I remember when I bought the farm. I bought it from the other banker here in town. And he said, ‘That’s got good water under it. You can irrigate that.’

“And I said, ‘I don’t think I will ever irrigate.’ Well, boy I was sure wrong. We was drilling a well a shortly after that. And it made a big difference. That irrigation changed the whole country.”

Harvey Pickrel was born in 1916 on a farm south of York, Nebraska. Harvey and his brother helped their father on the farm in many ways. They would harness the horses to the plow and, later on, drive the tractor and plow the fields. When he was old enough, Harvey started farming on his own. Harvey has seen a lot of good and bad years out on the farm, and he’s seen a lot of changes in the way farming is done.

“I must have said, ‘Well, if we’re dead, we’re just dead.’ That’s all I can remember because I don’t remember talking to her [the photographer Dorothea Lange]…

“I never once thought about living this long [81 years in 1979]. Well, I just didn’t think we’d survive. You want to know something we’re not living much better than we did, as high as everything is, than we did then…

Nettie Featherston and her family were trying to get to California when they ran out of money in Carey, Texas, in 1937. A local cotton grower took pity on the family and hired them to harvest his cotton. They were living in a small shack near Childress when photographer Dorothea Lange drove up, talked with Nettie and took photos of her. Lange recorded the desperation in her face and in her voice: “If you die, you’re dead – that’s all.” Nettie eventually moved to Lubbock, Texas, and never made it to California although several in her family did.

[Darrel Coble:] “The wind and the dust just blew every day. The one that I remember come in here from the north that evening. Dad was in the field, and I don’t know why as dry as it was. This thing [dust storm] rolled in there, and he got caught on the tractor. And he started for the house, but he couldn’t see the house. But we had an old chickenhouse just out east of the house. And the back wheel just clipped the corner of that chickenhouse, and he knew where he was at then. And he just stopped there and got in the chickenhouse and spent the night in the chickenhouse. [Laughter.] Of course, we had kerosene lamps and everything. It got so dark you couldn’t even see without – Kerosene lamps didn’t make no light so you could see by…

“Ah, it kind of scared me, best I can recall [laughs]. I thought maybe the world was coming to an end, I didn’t know [laughs]…

“Last spring we had some pretty bad days. They weren’t the old black dusters, but I mean, there was plenty of dust in the air…

[Question:] “Do you like living in this country?” “You bet.”

[Question:] “How come?”

“It’s just home. Dad always says, ‘Anybody ever come out here and wear out two pairs of shoes here, they’d never leave.’ I’ve known some that did do it in later years.”

[Question:] “Tell me about what was it like in Colorado?”

[Lois Houle:] “It was terrible. [Laughs.] We had dust storms and droughts. We survived back there as long as we possibly could. I can remember one dust storm back there. We were coming from my grandparents’ in Straton. And as we got closer to home, you could see this big gray matter up in the air. And the minute we got home, we had a storm cellar built with things to eat and everything else in it. We were all taken to the storm cellar right away, and they went in and closed the house all up good. And we stayed down there until the storm was over. It just came to the point where we couldn’t live any more back there. And we had relatives out here already.”

[Question:] “Did they write back or anything?”

“Oh, yes! Oh, yeah! Everything was ‘beautiful’ out here. [Laughs.] This was the land of milk and honey out here.” [Woody Guthrie’s “Dust Bowl Refugee”]

Darrell Coble was a three-year-old kid “Fleeing a Dust Storm” in the famous photograph by Arthur Rothstein. The photo was taken in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, in April 1936 and came to symbolize the impact that dust could have. Darrell lived in the same county for all of his life. In 1977, he farmed 190 acres but still needed to work as a propane truck driver to make ends meet. He died in 1979. Lois (Adolf) Houle was photographed by Dorothea Lange in Wapato, Wasington, in August 1929. Her family left the high plains of Colorado after several years of drought and dust storms.

“Earnie Rupp was a John Deere dealer in Gresham, and he talked me into getting the FSA [Farm Security Administration] loan. Well, they didn’t make the payments on the tractor, but they bought me the livestock. So, that’s what we lived on. We milked cows, and some chickens, eggs, you know. We’d go to town with a can of cream and several dozen eggs. That’s what bought out groceries. For my wife and I, if you bought $5 worth of groceries, that would last you a week. ‘Course, we had our meat and stuff.

“When I got that FSA loan, it was for a $1,020, and I looked at the check and thought, ‘Oh, my God, I’ll never on God’s earth pay that off, you know.’ And now, what’s $1,000 now? Well, it really tied you down. But, yeah, they gave us some money to buy hogs. And I bought a team of horses, and I bought some milk cows so I could make a living anyway.”

Question: “Did they work with you? I mean did they – I know that part of what they were trying to do was to teach people how to do bookkeeping and all that kind of stuff.”

“Well, yeah. And they kind of taught us to do that. You had to keep a good book. Yeah.”

lroy Hoffman grew up on a farm near York. He went to a rural school and started high school in York. But he came down with scarlet fever and had to be quarantined. Shortly after, his father also came up ill and Elroy had to leave school to work on the home place and as a hired man on other farms. For a time, he worked for the brothers of David Wessels. He and his wife Florence had two children. Elroy died in 2005.

“Now, that’s where you got started at when they run the renters off. We was helping them. I was working for a renter. Now the fellow I worked for, Frank Heine, is dead. He knows about him. He had half of that country out there. He’d have, oh maybe on a half section of land, there’d be two or three houses, you know, of me and him and you. Families living in them making a decent living working for him. Well, he seen he could buy tractors up, and [he said] ‘You get off! I don’t need you no more. I don’t need you no more.’