- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of archetypal in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- The dioramas at the natural history museum were archetypal old-style exhibitions .

- With his thin mustache and well-tailored clothes he is the archetypal image of a screen villain .

- Some people saw him as the archetypal science nerd .

- archetypically

- be someone all over idiom

- by way of idiom

- instantiate

- sum (something/someone) up

- symbolization

Examples of archetypal

Translations of archetypal.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

be up to your eyeballs in something

to be very busy with something

Binding, nailing, and gluing: talking about fastening things together

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Adjective

- Translations

- All translations

Add archetypal to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ ahr-ki- tahy -p uh l ]

an archetypal evil stepmother.

Discover More

Word history and origins.

Origin of archetypal 1

Example Sentences

Everard’s killer—an off-duty cop named Wayne Couzens—is the archetypal villain we don’t know.

Yes, they alienated some people, but they were totally OK with who they were alienating because they were moving closer to their ideal archetypal customer.

Like a refrain, they also circle back to the subject of myth as it relates to the human propensity to come to terms with the mysteries and verities that underwrite existence through archetypal stories.

Hinton is the archetypal academic, tousled, lost in thought, with a wry wit and healthy disrespect for authority.

If that is so, then Becker has written “The Heroine’s Journey” about three very different women who answered the archetypal call to adventure — and found themselves immersed in the chaos that was the Vietnam War.

Black Alice and Strix have origin stories that more closely resemble the archetypal comic heroes.

Marion Barry, the former four-time mayor of Washington D.C., notorious for being filmed smoking crack, is the archetypal survivor.

As Goggins puts it, “pictures about the archetypal not the stereotypical South.”

Christie, an archetypal tough guy happy warrior, at first dismissed accusations that the traffic jam was politically motivated.

Alex Jones is a representative Second Amendment enthusiast in the same way that Leonid Brezhnev is an archetypal progressive.

He had not wholly freed himself, however, from archetypal trammels.

Truly is Homer the primordial Hellenic seer, he who sees and sets forth the archetypal forms of the future of his race.

Yes, in the sight of God, like the archetypal ideas of the Platonists.

All things exist, according to his well-known doctrine of ideas, in an ideal or archetypal form, a pattern laid up in heaven.

This is a Generic Creation, creation according to genera or classes, like the "archetypal ideas" of Plato.

Related Words

- quintessential

- stereotypical

[ ak -s uh -lot-l ]

Start each day with the Word of the Day in your inbox!

By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policies.

The Role of Archetypes in Literature

Christopher Vogler's work on archetypes helps us understand literature

- Tips For Adult Students

- Getting Your Ged

- The Hero's Journey

The Job of the Herald

The purpose of the mentor, overcoming the threshold guardian, meeting ourselves in shapeshifters, confronting the shadow, changes brought about by the trickster.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Deb-Nov2015-5895870e3df78caebc88766f.jpg)

- B.A., English, St. Olaf College

Carl Jung called archetypes the ancient patterns of personality that are the shared heritage of the human race. Archetypes are amazingly constant throughout all times and cultures in the collective unconscious, and you'll find them in all of the most satisfying literature. An understanding of these forces is one of the most powerful elements in the storyteller’s toolbox.

Understanding these ancient patterns can help you better understand literature and become a better writer yourself. You'll also be able to identify archetypes in your life experience and bring that wealth to your work.

When you grasp the function of the archetype a character expresses, you will know his or her purpose in the story.

Christopher Vogler, author of The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure , writes about how every good story reflects the total human story. In other words, the hero's journey represents the universal human condition of being born into this world, growing, learning, struggling to become an individual, and dying. The next time you watch a movie, TV program, even a commercial, identify the following archetypes. I guarantee you'll see some or all of them.

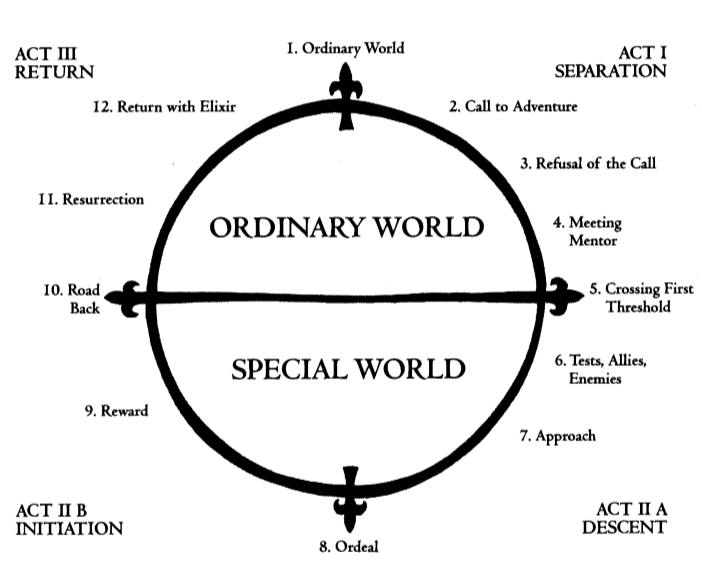

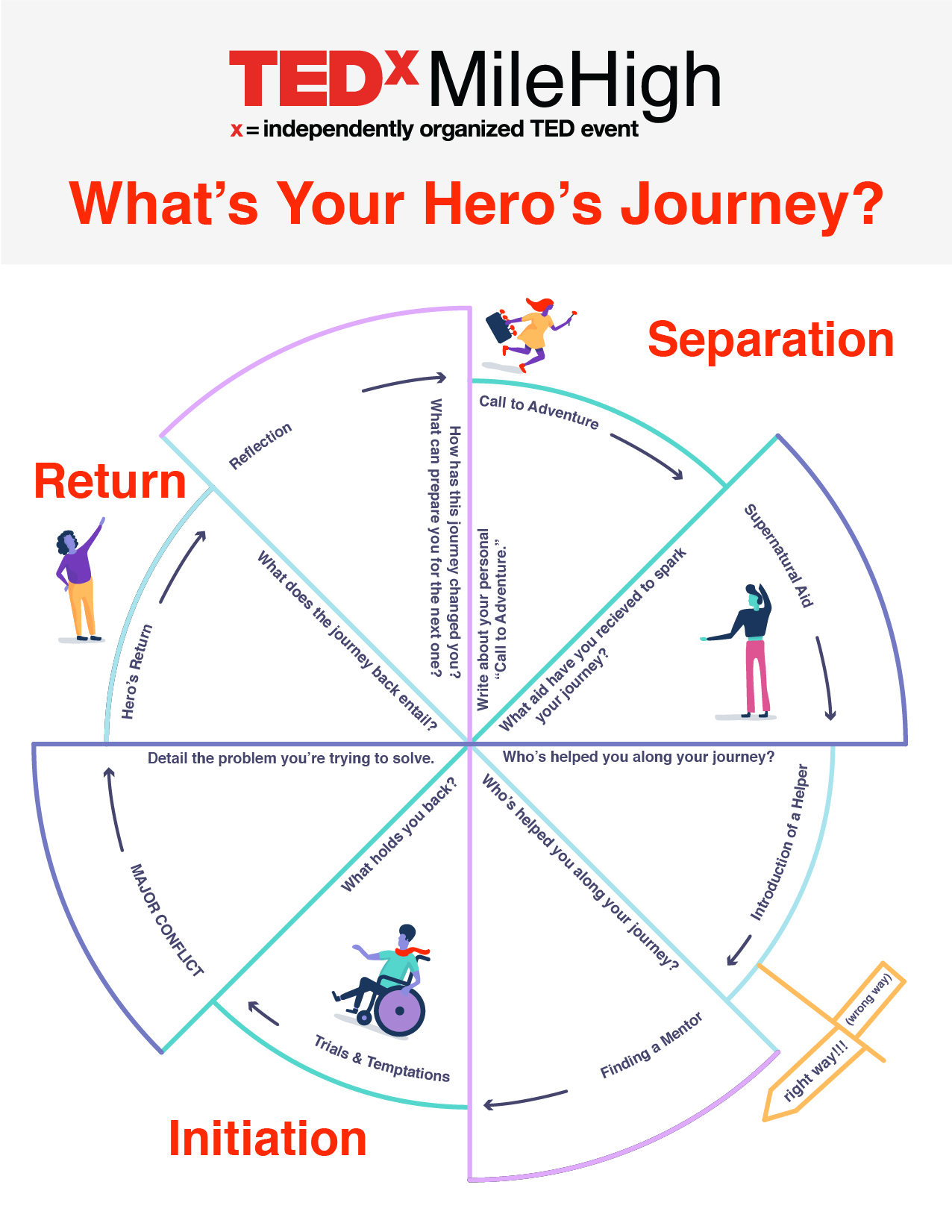

The Hero's Journey

The word "hero" comes from a Greek root that means to protect and serve. The hero is connected with self-sacrifice. He or she is the person who transcends ego, but at first, the hero is all ego.

The hero’s job is to incorporate all the separate parts of himself to become a true Self, which he then recognizes as part of the whole, Vogler says. The reader is usually invited to identify with the hero. You admire the hero's qualities and want to be like him or her, but the hero also has flaws. Weaknesses, quirks, and vices make a hero more appealing. The hero also has one or more inner conflicts. For example, he or she may struggle over the conflicts of love versus duty, trust versus suspicion, or hope versus despair.

In The Wizard of Oz Dorothy is the story's hero, a girl trying to find her place in the world.

Heralds issue challenges and announce the coming of significant change. Something changes the hero’s situation, and nothing is the same ever again.

The herald often delivers the Call to Adventure, sometimes in the form of a letter, a phone call, an accident.

Heralds provide the important psychological function of announcing the need for change, Vogler says.

Miss Gulch, at the beginning of the film version of The Wizard of Oz , makes a visit to Dorothy's house to complain that Toto is trouble. Toto is taken away, and the adventure begins.

Mentors provide heroes with motivation , inspiration , guidance, training, and gifts for the journey. Their gifts often come in the form of information or gadgets that come in handy later. Mentors seem inspired by divine wisdom; they are the voice of a god. They stand for the hero’s highest aspirations, Vogler says.

The gift or help given by the mentor should be earned by learning, sacrifice, or commitment.

Yoda is a classic mentor. So is Q from the James Bond series. Glinda, the Good Witch, is Dorothy's mentor in The Wizard of O z.

At each gateway on the journey, there are powerful guardians placed to keep the unworthy from entering. If properly understood, these guardians can be overcome, bypassed, or turned into allies. These characters are not the journey's main villain but are often lieutenants of the villain. They are the naysayers, doorkeepers, bouncers, bodyguards, and gunslingers, according to Vogler.

On a deeper psychological level, threshold guardians represent our internal demons. Their function is not necessarily to stop the hero but to test if he or she is really determined to accept the challenge of change.

Heroes learn to recognize resistance as a source of strength. Threshold Guardians are not to be defeated but incorporated into the self. The message: those who are put off by outward appearances cannot enter the Special World, but those who can see past surface impressions to the inner reality are welcome, according to Vogler.

The Doorman at the Emerald City, who attempts to stop Dorothy and her friends from seeing the wizard, is one threshold guardian. Another is the group of flying monkeys who attack the group. Finally, the Winkie Guards are literal threshold guardians who are enslaved by the Wicked Witch.

Shapeshifters express the energy of the animus (the male element in the female consciousness) and anima (the female element in the male consciousness). Vogler says we often recognize a resemblance of our own anima or animus in a person, project the full image onto him or her, enter a relationship with this ideal fantasy, and commence trying to force the partner to match our projection.

The shapeshifter is a catalyst for change, a symbol of the psychological urge to transform. The role serves the dramatic function of bringing doubt and suspense into a story. It is a mask that may be worn by any character in the story, and is often expressed by a character whose loyalty and true nature are always in question, Vogler says.

Think Scarecrow, Tin Man, Lion.

The shadow represents the energy of the dark side, the unexpressed, unrealized, or rejected aspects of something. The negative face of the shadow is the villain, antagonist, or enemy. It may also be an ally who is after the same goal but who disagrees with the hero’s tactics.

Vogler says the function of the shadow is to challenge the hero and give her a worthy opponent in the struggle. Femmes Fatale are lovers who shift shapes to such a degree they become the shadow. The best shadows have some admirable quality that humanizes them. Most shadows do not see themselves as villains, but merely as heroes of their own myths.

Internal shadows may be deeply repressed parts of the hero, according to Vogler. External shadows must be destroyed by the hero or redeemed and turned into a positive force. Shadows may also represent unexplored potentials, such as affection, creativity, or psychic ability that goes unexpressed.

The Wicked Witch is the obvious shadow in the Wizard of Oz.

The trickster embodies the energies of mischief and the desire for change. He cuts big egos down to size and brings heroes and readers down to earth, Vogler says. He brings change by drawing attention to the imbalance or absurdity of a stagnant situation and often provokes laughter. Tricksters are catalyst characters who affect the lives of others but are unchanged themselves.

The Wizard himself is both a shapeshifter and a trickster.

- The Approach to the Inmost Cave in the Hero's Journey

- The Hero's Journey: Crossing the Threshold

- An Introduction to The Hero's Journey

- The Hero's Journey: Refusing The Call to Adventure

- The Ordeal in the Hero's Journey

- The Reward and the Road Back

- The Hero's Journey: Meeting with the Mentor

- The Ordinary World in the Hero's Journey

- The Resurrection and Return With the Elixir

- "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" Study Guide

- Therapeutic Metaphor

- The Definition of Quest in Literature

- Foreshadowing in Narratives

- The Tin Man's Toxic Metal Makeup

- The Heroes of Ancient Greece and Rome

- What Is an Antagonist?

What Are Archetypal Settings?

The archetypal settings represent the different locations that are found in literature. The article will explore what each setting has to offer, as well as how it can be used by writers.

Every writer should consider using different archetypes for their work because they provide a fresh perspective on a story and make the writing more interesting.

In this blog post, we will discuss some of these types of settings and why you might want to use them.

Quick Navigation

What are archetypal settings?

Archetypes in literature are stories that we all immediately recognise because they have heard simple fairy tale type versions of them when very young.

Thus, the rags-to-riches story; the misunderstood character whose gifts and powers are only revealed later; the quest where a series of trials are overcome; the supplanted heir; and so on.

Archetypal settings are where stories of those types typically take place. For the most part, fairy tales would be an archetypal story type and the setting would be magical, mythical, or unrealistic in nature.

Have you ever read a horror story that took place in broad daylight?

Probably not very often, since “dark and scary nights” tend to be where horror movies take place.

Understanding the archetypes associated with different settings can help reinforce tone, foreshadowing, and theme.

Archetypal settings notes:

- Themes that are found in stories and myths

- Stories that are set in a specific time period or place

- Story settings can be used to make the story more interesting

- A setting that is a physical place

- A setting that is an emotional state or mood

- A setting that represents the protagonist’s inner life

Why is setting important?

Setting can be an important aspect of story crafting and without a clear setting, your plot and characters end up in the empty abyss.

A setting is one of the tools that you can use to help create a certain world within your story. Try using settings in an early chapter or in other places where there is more detail and less dialogue so that it has greater impact.

24 Archetypal Settings You NEED To Know

Archetypes are fundamental “building blocks” of storytelling. Certain characters, plots and settings show up over and over in stories from all over the world and in all time periods. These archetypes have special symbolic meanings.

Here are some examples of archetypal settings

A river can be associated with the process of crossing into a new chapter in your life or for example, baptism.

A river crossing often represents a boundary of some kind, like going from one life phase to another or experiencing new challenges.

The garden setting can be associated with Purity, Solitude, Reflection, Quest for Meaning.

The contrast between the garden and the forest is significant. The garden is planned, organized, safe from worldly distractions and has a beauty found only in nature.

The Wasteland

In opposition to the Garden, the wasteland setting can be associated with loneliness, desolation, despair; the place where there is no growth

The Maze or Labyrinth

The maze setting can Represent a puzzling dilemma or great uncertainty; sometimes represents the search for a monster within himself.

The castle setting can be associated with a strong place of safety; holds the treasure or princess; may be bewitched or enchanted; may represent home or some other safe place.

The tower setting can be associated with a strong place where evil resides or where the self is locked away from society and fellowship.

The Tree setting represents life and knowledge; growth, proliferation; symbol of immortality

The Wilderness/Forest

The Wilderness/Forest setting symbolises Fertility. Those who enter often lose their direction or rational outlook and thus tap into their collective unconscious. Unregulated space is opposite of cultivated gardens. A place where rules don’t apply, and people and things run wild

The forest is unpredictable and so it’s dangerous. It’s a place where sometimes the normal rules of society don’t apply. Creatures, people and magic are free to run wild in nature.

The Threshold

The Threshold setting is A gateway to a new world the hero must enter to change and to grow.

Humans want to control and call the shots, but nature laughs at this view.

The Sea setting can symbolise a few things:

- Waves may symbolize measures of time and represent eternity or infinity

- Vast, alien, dangerous, chaos

- The mother of all life; spiritual mystery; death and/or rebirth; timelessness and eternity

- Death and rebirth (baptism); the flowing of time into eternity; transitional phases of life cycle

- Water offers the opportunity for a rebirth into its depths.

The Desert setting can be associated with Spiritual aridity; death; hopelessness.

Deserts provide an escape that allows you to explore your thoughts and escape the constraints of daily life.

The Underworld

The Underworld setting can be associated with the place where the hero encounters fear or death

The Crossroads

The Crossroads setting can be associated with a place of suffering and decision

The Winding Stairs

The Winding Stairs setting can be associated with the long and difficult way into the unknown

Islands, Ships at Sea

Islands, Ships at Sea settings can all be associated with the spiritual, mental, and physical isolation or exile

The Mountains setting can be associated with personal achievement; meeting place of earth and heaven; a spiritual peak.

Being at the peak of a mountain can offer characters insight and clarity.

The Caves setting can be associated with a descent into the unconscious or inner self; a place to face innermost fears.

The underground is often represented as a perilous journey, challenging the protagonist to overcome their worst fears.

The Bridge setting can be associated with a link between worlds

The Haven setting is a place of safety where the hero may be sheltered for a time while he or she regains health or strength. It can come in many forms and contrasts sharply against the dangerous wilderness.

The Tavern setting is located on the edge or outlying spaces; a jumping off point. The place visited by the hero before beginning the actual adventure. A place where the rumors and travelers from abroad – those who have been out there and have experienced what lies beyond – meet and exchange information. An alternate setting that functions similarly is the seaport.

The Day as a setting represents safety, knowledge, and order

The Night as a setting represents danger, a lack of knowledge, and disorder.

The City as a setting represents order, law, harmony, civilization

The Rock as a setting represents stony place of suffering

Setting Archetypes in Literature

William Goldman’s Lord of the Flies uses as many setting archetypes as it can. The main characters are isolated on an island set in a deserted sea, chased by threats from the forest while taking refuge in the lagoon and often climb to light up their signal fire high on top of the mountain

The sun in the west was a drop of burning gold that slid nearer and nearer the sill of the world. All at once they were aware of the evening as the end of light and warmth.

The setting for the book shifts with time as well. There are different symbols and locations that represent deepening revelations, and it is reflected in the tone of the characters.

Often writers, especially those of short fiction, leave the details to be talked about later.

Sometimes these details are never revisited or brought back into the story and become uninteresting in service of a larger theme within a story.

Always make sure to use the setting in any story as it can add depth and meaning without other archetypes, which can help

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of archetype

Did you know.

Archetype comes from the Greek verb archein ("to begin" or "to rule") and the noun typos ("type"). Archetype has specific uses in the fields of philosophy and psychology. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato, for example, believed that all things have ideal forms (aka archetypes) of which real things are merely shadows or copies. And in the psychology of C. G. Jung, archetype refers to an inherited idea or mode of thought that is present in the unconscious of the individual. In everyday prose, however, archetype is most commonly used to mean "a perfect example of something."

- grandaddy

- predecessor

Examples of archetype in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'archetype.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Latin archetypum , from Greek archetypon , from neuter of archetypos archetypal, from archein + typos type

1545, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Articles Related to archetype

Words of the Week - April 8

Dictionary lookups from SCOTUS, higher education, and the world of podcasting

Get Word of the Day delivered to your inbox!

Dictionary Entries Near archetype

Cite this entry.

“Archetype.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/archetype. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of archetype, medical definition, medical definition of archetype, more from merriam-webster on archetype.

Nglish: Translation of archetype for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of archetype for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about archetype

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 19, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), a great big list of bread words, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), games & quizzes.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write Archetypes

I. What is an Archetype?

An archetype (ARK-uh-type) is an idea, symbol, pattern, or character- type, in a story. It’s any story element that appears again and again in stories from cultures around the world and symbolizes something universal in the human experience.

Archetypes are always somewhat in question. After all, no one has studied every culture in the world – that would be impossible – so we never know for sure whether something is truly universal .

II. Examples of Archetype

The most famous example of an archetype is the Hero . Hero stories have certain elements in common – heroes generally start out in ordinary circumstances, are “called to adventure,” and in the end must confront their darkest fear in a conflict that deeply transforms the hero. Luke Skywalker is a perfect example of a this archetype: he’s born on Tatooine, is called to adventure by R2-D2 and Obi-Wan Kenobi, and must then face Darth Vader in order to become a Jedi. (There’s a book, called The Hero with a Thousand Faces , that lays out in detail the archetypal Hero story, and George Lucas read it many times before making Star Wars. )

After the Hero, the most common archetype is probably the Trickster . Tricksters break the ordinary rules of society and even nature. They are often androgynous (having both male and female attributes), and they love to play tricks on those around them. They may also laugh at things others find terrifying, such as death or isolation. Tricksters are believed to symbolize the chaotic and complex realities of the world that are beyond the understanding of the human mind. Tricksters can be evil (like Loki or the Joker), or they can be good (like Bugs Bunny).

Another archetypal character is the Anti-Hero , who has many of the attributes of a Hero but is not a traditional “good guy.” Batman, for example, is an anti-hero: while he fights crime and stops super- villains , he is also a moody recluse with a slightly cruel streak. As heroic as he may be, he is also fearsome and probably wouldn’t be much fun to have around.

III. Types of Archetype

There are far too many archetypes to list all of them, but they broadly fall into three categories:

a. Character archetypes

The most common and important kind of archetypes. Most popular characters have a universal archetype such as Hero, Anti-Hero, or Trickster (see the previous section). There are literally hundreds of different character archetypes, including the Seductress, the Father and Mother Figures, the Mentor, and the Nightmare Creature.

b. Situational archetypes

Situations that appear in multiple stories. Examples might include lost love, returning from the dead, or orphans destined for greatness.

c. Symbolic archetypes

Symbols that appear repeatedly in human cultures. For example, trees are an archetypal symbol of nature (even in cultures that live in relatively tree-less areas). Fire is also an archetypal symbol, representing destruction but also ingenuity and creativity.

IV. The Importance of Archetypes

The concept of archetypes was first developed by Carl Jung, a psychologist who discovered certain broad similarities among myths from all over the world. In particular, he noticed that “hero stories” all had similar elements, and that all cultural heroes had certain broad attributes in common. He theorized that this was because human beings all shared a “collective unconscious” – that is, a set of hard-wired expectations and preferences about stories. In much the same way that there is a “universal grammar” underlying all human languages, there may be a “universal grammar” of good stories!

So archetypes are part of the key to what makes a story compelling. The best storytellers draw on universal archetypes in crafting their stories, and thus tap into something elemental in the human mind – and in many cases, they do this automatically, without ever setting out to write an archetypal story.

V. Examples of Archetype in Literature

In George Orwell’s Animal Farm , the pig Snowball is a classic example of the Scapegoat archetype – a character who is blamed for everything that goes wrong, and must ultimately be sacrificed or driven away.

In the Old Testament, the story of Moses has many parallels to the Hero archetype. He is born in lowly circumstances (an orphan in a reed basket), and must face his greatest fears (both Pharaoh and his own fearsome God), before returning to his people bearing the 10 Commandments – in this case not only he, but the whole tribe of Israelites are transformed by Moses’s heroic journey.

In the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit books, both Bilbo Baggins and Frodo Baggins are classic Hero archetypes. They start out as ordinary Hobbits living under the hill, but hear a call to adventure when Gandalf and the Dwarves come to the door. Over the course of the journey, they must fight dragons and dark lords (both examples of the Nightmare Beast archetype), before returning to The Shire as transformed individuals.

VI. Examples of Archetype in Pop Culture

Bugs Bunny is a classic example of the Trickster. He frequently dresses up as a woman to deceive his pursuers, and is impossible for human beings like Elmer Fudd and Yosemite Sam to capture. According to archetype theory, these tricky escapes are symbolic explorations of the inherent limits on human thought.

Yoda is one of the best examples of the Mentor archetype. He lives on a faraway, inhospitable planet, similar to the way a guru might live on top of a mountain. And he trains the Hero (Luke) in both body and mind, but more importantly he forces Luke to confront the darkest parts of himself. That’s the symbolism of the cave scene, when Luke Skywalker fights a false “Darth Vader” – an illusory enemy who turns out to be merely a projection of himself.

The Mentor archetype is also exemplified by both Professor X and Magneto in the X-Men stories. These characters train various heroes (and villains) in their own way, and they live in secluded fortresses. But, like Yoda, part of the story is also getting the hero/villain to confront their own psyche. Think, for example, of Professor X’s relationship with Wolverine, in which Wolverine is forced to face his past and all the pain that it has caused. (Wolverine, incidentally, is an excellent example of an Anti-Hero.)

VII. Related Terms

Like an archetype, a cliché appears again and again in different stories. But “archetype” has a positive connotation, while “cliché” has a negative connotation. Why? Probably because archetypes come with genuine psychological force, and therefore we never get sick of them no matter how many times we see them. Clichés get tired from overuse – archetypes never do.

Typically, an archetype is also broader and more general, while a cliché tends to be a narrow, specific moment. So it’s an archetype (or at least a trope) to see a team of heroes in which one is far older than the other. Such stories evoke both the Hero and Mentor archetypes. However, if the older partner says, “I’m getting too old for this…” that’s a cliché.

An archetype is a particularly powerful kind of trope. Tropes are the broader category of common elements in stories, but a trope is generally not considered universal – it’s just very common, especially in a particular genre or culture. Again, the line between tropes and clichés is not black-and-white. For example, the “damsel in distress” figure is very common in literature, mythology, and popular culture – but it’s debatable whether this is a cliché, a trope, or even an archetype!

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of archetypal adjective from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

- The Beatles were the archetypal pop group.

- It was the archetypal British suburb, built in the 1930s.

Questions about grammar and vocabulary?

Find the answers with Practical English Usage online, your indispensable guide to problems in English.

Nearby words

- The Archers

Archetypes Guide: Definitions and Meanings Explained

What are archetypes, how archetypes apply to personalities, archetypes in jungian psychology.

- Archetypes in literature and film

- How to identify archetypes

- Why archetypes matter in storytelling

- Common archetypes and their meanings

How to use archetypes in character development

Imagine you're having a chat with a friend about your favorite movie characters. You start realizing that despite the diversity of films, there's a striking similarity in the roles these characters play. Ever wonder why? Meet archetypes! This guide will walk you through the definition of archetype, their meanings, and why they're more prevalent in our lives than you might think.

At its core, the definition of archetype is a typical example, a model, or a recurring symbol that appears in literature, art, and mythology. Think of it like the blueprint that shapes the characters we see in stories, the roles people play in society, or even the personas we adopt in our everyday lives.

- Blueprint of Character: Archetypes are like the cookie cutters used to shape characters in stories. Ever noticed how most adventure stories have a hero, a mentor, and a villain? Those are archetypes!

- Social Role: In a society, archetypes might be the roles people typically play like the caregiver, the rebel, or the wise old man. These roles are not just random, but they reflect deep patterns in human behavior and our shared cultural heritage.

- Personal Persona: On a personal level, archetypes can represent the different facets of our personalities. One day, you might play the role of the innocent child, the next day, you might be the explorer setting out on a new adventure.

Remember, the definition of archetype goes beyond just a stereotype or a cliché. It's a fundamental pattern that reflects our shared human experience, and that's what makes them so powerful and intriguing.

Ever had a moment when you thought, "Why am I acting this way?" Well, you might just be channeling an archetype. Let's dig into how archetypes apply to personalities.

Think of your personality as a home. It's not just one big empty space, right? It has different rooms for different purposes – the kitchen, the living room, the study, and so forth. Similarly, our personality isn't just one thing; it's a complex structure with different 'rooms' or aspects. These aspects are often shaped by various archetypes.

- The Hero: When you step up to face a challenge head-on, you're channeling the Hero archetype. This doesn't have to be slaying actual dragons (although if you do, we'd love to hear about it); it can be as simple as standing up for a friend or pushing through a tough workout.

- The Caregiver: When you find yourself going out of your way to help others, that's the Caregiver in you. This archetype is all about compassion, generosity, and selflessness.

- The Explorer: Do you have a thirst for adventure? Love trying new things? That's the Explorer archetype. It's this aspect of your personality that pushes you to break away from the norm and seek out new experiences.

Understanding these archetypes isn't about putting ourselves in boxes—it's about recognizing the many facets of our personalities. So next time you're surprised by your own actions, you might just have encountered an archetype in action!

If you've ever taken a deep dive into the waters of psychology, you've probably bumped into a fellow named Carl Jung. He introduced the concept of archetypes into psychology. But what exactly is the definition of archetype in Jungian terms?

In the world of Jungian psychology, archetypes are universal symbols or themes that reside in our collective unconscious. These symbols are shared by all of humanity and shape our thoughts, dreams, and behaviors. They're like the DNA of our shared psychological makeup.

Here's a quick rundown of a few key archetypes in Jungian psychology:

- The Shadow: This archetype represents our darker side – the repressed thoughts, feelings, and actions we don't want to acknowledge. It's those parts of ourselves we'd rather keep in the shadows.

- The Anima/Animus: The Anima and Animus archetypes represent the feminine and masculine aspects within us all. Whether you identify as male, female, or non-binary, you have both Anima and Animus within you.

- The Self: This archetype is the granddaddy of them all. It represents the unified unconsciousness and consciousness of an individual. It's the archetype that encapsulates your whole personality and strives for balance and wholeness.

When we understand Jung's archetypes, we can better understand ourselves and others. Recognizing these patterns can help us navigate our relationships, our dreams, and even our personal growth journey. So, the next time you're trying to understand a complex emotional experience, remember—there's probably an archetype for that!

Archetypes in Literature and Film

Pop the popcorn and get comfy because we're about to dive into the fascinating world of archetypes in literature and film. Have you ever wondered why certain characters or stories feel oddly familiar? Well, that's because many of them are based on archetypes. Understanding the definition of archetype in this context can add a whole new layer of depth to your next Netflix binge or book club discussion.

In literature and film, archetypes are typically expressed through characters, themes, or situations. They provide a framework that helps us quickly understand a character's role or a story's direction. Let's look at a few examples:

- The Hero: The hero is a character who embarks on a journey to overcome challenges and bring peace or justice. Think Harry Potter or Frodo Baggins.

- The Mentor: The mentor offers guidance and wisdom to the hero. They are often older and wiser characters, like Dumbledore in Harry Potter or Gandalf in Lord of the Rings.

- The Villain: Every story needs a good villain! This character opposes the hero, creating conflict in the story. Think Voldemort or Sauron.

These archetypes are found all over literature and film because they resonate with us on a deep, psychological level. We connect with them because they reflect universal aspects of the human experience. So next time you're watching a movie or reading a book, see if you can spot these archetypes. You might just find that it adds a whole new level of enjoyment to your experience!

How to Identify Archetypes

Now, let's put our detective hats on and uncover some tips on how to identify archetypes. It's like a treasure hunt, but instead of gold, we're unearthing universal patterns of human behavior!

The first step to identify an archetype is to look at a character's role within a story. Are they the hero, the villain, the mentor, or the sidekick? Perhaps they're the star-crossed lover or the trickster? Once you've figured that out, you're halfway there!

Next, examine their behavior, strengths, weaknesses, and the challenges they face. Does the hero have a tragic flaw? Does the villain have a redeeming quality? This adds depth to the archetype and makes them more relatable.

Also, consider the recurring themes or situations in the story. For example, the journey, the quest, or the transformation are all archetypal situations that can give you clues about the characters involved.

And lastly, don't forget the setting! It can also be an archetype. From the small, peaceful town to the bustling, corrupt city; the enchanting forest to the terrifying abyss—each of these settings has an archetypal meaning.

Remember, the definition of archetype is a universally understood symbol or term, or pattern of behavior. If a character, situation, or setting feels familiar or universal, there's a good chance it's an archetype. So, keep your eyes peeled and happy hunting!

Why Archetypes Matter in Storytelling

Did you ever wonder why some stories, regardless of their origin, feel so familiar and comforting? Or why some characters, despite their flaws, are so relatable and captivating? Well, our friends, the archetypes, deserve some credit here!

Archetypes are the secret sauce that adds depth and universal appeal to a story. They tap into our shared human experience, making the narrative more meaningful and impactful. And that's why they're so important in storytelling.

By using archetypes, storytellers can craft characters and situations that resonate with audiences across different cultures and time periods. They offer a sort of 'shortcut' to understanding complex emotions and motivations, making the story easier to connect with and digest.

Moreover, archetypes foster predictability—not in a boring sense but in a comforting one. When we spot an archetype in a story, it's like running into an old friend. We know what to expect and look forward to how the familiar will interact with the new.

But don't mistake this predictability for simplicity. Archetypes can be surprisingly complex and versatile. They can change, grow, and even surprise us—just like real people. This complexity makes them even more engaging and relatable.

So, next time you read a book or watch a movie, try to spot the archetypes. You'll be amazed at how much more depth and meaning you'll find in the story. And remember, the definition of archetype is not a rigid mold but a flexible pattern that can be adapted and reshaped. Now that’s the beauty of storytelling!

Common Archetypes and Their Meanings

Now that we've touched on why archetypes are an integral part of storytelling, let's dive into some common archetypes and their meanings. You might recognize some of these from your favorite books, movies, or even from people you know!

The Hero: Ah, the person we all root for — the hero. Their mission? To save the day, of course. The hero is defined by their bravery, selflessness, and determination to overcome obstacles and achieve their goal. Think Harry Potter, who despite numerous challenges, never stops fighting against the dark forces.

The Mentor: Who would our hero be without their wise and experienced mentor? This archetype provides guidance and advice, often helping the hero realize their full potential. Just like Dumbledore did for Harry, a mentor often sees the hero's potential before they do themselves.

The Outlaw: Meet the rebel, the rule-breaker, the one who dares to challenge the status quo. The Outlaw archetype isn't afraid to upset the apple cart to bring about change. They're often seen as a symbol of freedom and non-conformity. Robin Hood, anyone?

The Lover: This archetype is all about passion, romance, and relationships. They seek to create deep connections with others and value love above all else. Romeo and Juliet, despite their tragic end, embody this archetype to a tee.

The Jester: Life's a stage, and the Jester is here to enjoy the show! This archetype represents joy, humor, and the ability to live in the moment. They remind us not to take life too seriously and to find joy in the everyday—just like Olaf from Frozen.

These are just a few examples of the many archetypes out there. Each one represents different aspects of the human experience. And by understanding the definition of archetype, we can better understand the characters we meet in stories—and maybe even in real life.

Alright, let's get down to business. You've gotten a grasp on the definition of archetype and some common examples. Now, how do you use this knowledge to flesh out your characters? Let's find out.

Start with the basics: Begin with the basic traits of your character. Are they brave, wise, rebellious, romantic, or maybe a bit of a jokester? This can help guide you towards an archetype that suits your character. For instance, a brave character might fit well into the Hero archetype.

Build on the archetype: Once you've selected an archetype, don't just stop there. Use it as a foundation to build a complex, well-rounded character. Remember, an archetype is not a stereotype—it's a starting point. Your Hero can have flaws, your Outlaw can have moments of doubt, and your Jester can have hidden depths.

Add some conflict: One of the most compelling parts of a story is the conflict. What if your Hero is afraid of responsibility? What if your Mentor has a secret they're hiding? By adding conflict, you can create tension and add layers to your character.

Use archetypes for relationships: Archetypes can also help shape the relationships between characters. A Hero and Mentor relationship can form a deep bond, while a Jester might provide comic relief or challenge the Hero in their journey.

In the end, remember this: archetypes serve as tools to help you understand and develop your characters, but they should never limit your creativity. Use them as a guide, not a rulebook. The real magic happens when you let your characters break the mold and become truly unique.

If you're intrigued by the concept of archetypes and want to learn how to incorporate them into your art, don't miss Juliet Schreckinger's workshop, ' Composing Complex Illustrations using Basic Shapes .' This workshop will guide you through the process of creating visually striking illustrations that are rich with meaning, making use of archetypes to enhance your work.

Live classes every day

Learn from industry-leading creators

Get useful feedback from experts and peers

Best deal of the year

* billed annually after the trial ends.

*Billed monthly after the trial ends.

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

Archetypal Literary Theory / Criticism

Archetypal literary theory, also known as archetypal criticism, analyzes literature focusing on archetypes, symbols, characters, motif etc.

Introduction

Table of Contents

Archetypal literary theory , also known as archetypal criticism , is an approach to analyzing literature focusing on the identification and interpretation of archetypes —universal symbols, themes, characters, and motifs—that recur across cultures and periods.

Derived from the concept of the collective unconscious proposed by Carl Jung , archetypal theory strives to go deep into the innate human experiences and instincts that shape the narratives.

By exploring these recurring patterns and symbols , archetypal critics seek to uncover the deeper psychological, cultural, and mythological meanings embedded within literary texts, providing valuable insights into the fundamental aspects of human existence and storytelling across the ages.

Etymology Archetypal Literary Theory / Criticism

- The term “archetypal” comes from the Greek word “archétypos,” meaning “original pattern” or “model.”

- “Criticism” is derived from the Greek word “krinein,” which translates to “to judge” or “to analyze.”

- “ Archetypal criticism ” involves the analysis and interpretation of original patterns and universal symbols present in literature and other storytelling mediums.

Etymology Archetypal Literary Theory: Origin, Key Theorists, Works and Arguments

Origin of archetypal literary theory:.

- Emerged in the mid-20th century, primarily in the field of literary criticism.

- Rooted in the ideas of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung and his concept of archetypes.

Key Theorists in Archetypal Literary Theory:

- Carl Jung: The foundational figure in the development of archetypal theory. His work on the collective unconscious and archetypes greatly influenced literary scholars.

- Joseph Campbell: A prominent scholar who popularized the concept of the hero’s journey and its connection to archetypal patterns in world mythology.

- Northrop Frye: An influential literary critic who incorporated archetypal elements into his theory of literary genres and mythic patterns.

- Maud Bodkin: Known for her work on the archetypal dimensions of poetic language in Archetypal Patterns in Poetry .

Notable Works in Archetypal Literary Theory:

- The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (1950) by Carl Jung: In this seminal work, Jung explores the concept of archetypes and their relevance to psychology and culture.

- The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) by Joseph Campbell: Campbell’s book outlines the monomyth, or hero’s journey, as a universal narrative structure found in myths and stories from various cultures.

- Anatomy of Criticism (1957) by Northrop Frye: In this work, Frye discusses archetypal patterns in literature, particularly within the context of literary genres.

- Archetypal Patterns in Poetry (1934) by Maud Bodkin: Bodkin examines the presence of archetypal symbols and themes in poetry, emphasizing their emotional and psychological impact.

Main Arguments in Archetypal Literary Theory:

- Existence of Universal Archetypes: Archetypal theorists argue that certain symbols, themes, and character types are universal and recurrent across cultures and time periods.

- Collective Unconscious: Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious suggests that these archetypes are inherited and shared by all humans, influencing their thoughts, emotions, and creativity.

- Mythic Patterns and the Hero’s Journey: The theory identifies recurring mythic patterns, such as the hero’s journey, which reflect fundamental human experiences and transformations.

- Interpretation of Literature: Archetypal criticism involves interpreting literature through the lens of these archetypes, exploring the deeper meanings and psychological resonances within texts.

Archetypal Literary Theory continues to be a significant approach in the study of literature and storytelling, offering insights into the universal themes and symbols that shape human narratives.

Principal of Archetypal Literary Theory

Suggested readings.

- Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space . Beacon Press, 1994.

- Bodkin, Maud. Archetypal Patterns in Poetry: Psychological Studies of Imagination . Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces . Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Estés, Clarissa Pinkola. Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype . Ballantine Books, 1996.

- Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays . Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Jung, Carl Gustav. Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious . Routledge, 2014.

Related posts:

- Marxism Literary Theory

- Russian Formalism

- Chaos Literary Theory-2

- Globalization Theory, Theorists and Arguments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Definition of Archetype

An archetype is a literary device in which a character is created based on a set of qualities or traits that are specific and identifiable for readers. The term archetype is derived from the studies and writings of psychologist Carl Jung who believed that archetypes are part of humanity’s collective unconscious or memory of universal experiences. In a literary context , characters (and sometimes images or themes ) that symbolically embody universal meanings and basic human experiences, independent of time or place, are considered archetypes.

For example, one of the most common literary archetypes is the Hero . The hero is generally the protagonist of a narrative and displays ubiquitous characteristics such as courage , perseverance, sacrifice, and rising to challenge. Though heroes may appear in different literary forms across time and culture, their characterization tends to be universal thus making them archetypal characters.

Common Examples and Descriptions of Literary Archetypes

As a rule, there are twelve primary character types that symbolize basic human motivations and represent literary archetypes. Here is a list of these example literary archetypes and their general descriptions:

- Lover: character guided by emotion and passion of the heart

- Hero : protagonist that rises to a challenge

- Outlaw: character that is rebellious or outside societal conventions or demands

- Magician: powerful character that understands and uses universal forces

- Explorer: character that is driven to explore the unknown and beyond boundaries

- Sage: character with wisdom, knowledge, or mentor qualities

- Creator: visionary character that creates something significant

- Innocent: “pure” character in terms of morality or intentions

- Caregiver: supportive character that often sacrifices for others

- Jester: Character that provides humor and comic relief with occasional wisdom

- Everyman: Character recognized as average, relatable, found in everyday life

- Ruler: Character with power of others, whether in terms of law or emotion

Examples of Archetype in Shakespearean Works

William Shakespeare utilized archetype frequently as a literary device in his plays. Here are some examples of archetype in Shakespearean works:

- Lover: Romeo (“Romeo and Juliet”), Juliet (“Romeo and Juliet”), Antony (“Antony and Cleopatra”)

- Hero : Othello (“Othello”), Hamlet (“Hamlet”), Macduff (“ Macbeth ”)

- Outlaw: Prince Hal (“Henry IV”), Edmund (“ King Lear ”), Falstaff (“Henry IV”)

- Magician: Prospero (“The Tempest”), The Witches (“Macbeth”), Soothsayer (“Julius Caesar”)

- Sage: Polonius (“Hamlet”), Friar Laurence (“Romeo and Juliet”), Gonzalo (“The Tempest”)

- Innocent: Viola (“ Twelfth Night ”), Ophelia (“Hamlet”), Hero (“Much Ado about Nothing”)

- Caregiver: Nurse (“Romeo and Juliet”), Mercutio (“Romeo and Juliet”), Ursula (“Much Ado about Nothing”)

- Jester: Touchstone (“As You Like It’), Feste (“Twelfth Night ”), Fool (“King Lear”)

- Everyman: Lucentio (“ The Taming of the Shrew ”), Valentine (“The Two Gentelmen of Verona”), Florizel (“The Winter ’s Tale”)

- Ruler: King Lear (“King Lear”), Claudius (“Hamlet”), Alonso (“The Tempest”)

Famous Examples of Archetype in Popular Culture

Think you don’t know of any famous archetypes? Here are some well-known examples of archetype in popular culture:

- Lovers: Ross and Rachel ( Friends ), Scarlett O’Hara ( Gone with the Wind ), Jack and Rose ( Titanic )

- Heroes: Frodo Baggins ( The Lord of the Rings ), Luke Skywalker ( Star Wars ), Mulan (Mulan)

- Outlaws: Han Solo ( Star Wars ), Star-Lord/Peter Quill ( Marvel Universe ), Ferris Bueller ( Ferris Bueller’s Day Off )

- Magicians: Gandalf (The Lord of the Rings), Dumbledore (Harry Potter ), Doctor Strange ( Marvel Universe )

- Explorers: Huck Finn ( The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn ), Indiana Jones ( Indiana Jones ), Captain Kirk ( Star Trek )

- Sages: Atticus Finch ( To Kill a Mockingbird ), Jiminy Cricket (Disney’s Pinocchio ), Obi-Wan Kenobi ( Star Wars )

- Creators: Victor Frankenstein ( Frankenstein ), Willy Wonka ( Charlie and the Chocolate Factory ), Daniel Plainview ( There Will Be Blood )

- Innocents: Tiny Tim ( A Christmas Carol ), Dorothy ( The Wizard of Oz ), Forrest Gump ( Forrest Gump )

- Caregivers: Mary Poppins ( Mary Poppins ), Alice ( The Brady Bunch ), Marge Simpson ( The Simpsons )

- Jesters: Donkey ( Shrek ), Kramer ( Seinfeld ), Eric Cartman ( Southpark )

- Everyman Characters: The Dude ( The Big Lebowski ), Homer Simpson ( The Simpsons ), Jim Halpert ( The Office )

- Rulers: Daenerys Targaryen ( Game of Thrones ), T’Challa/Black Panter ( Marvel Universe ), Don Corleone (The Godfather)

Difference Between Archetype and Stereotype

It can be difficult to distinguish the difference between archetype and stereotype when it comes to literary characters. In general, archetypes function as a literary device with the intent of complex characterization. They assign characters with specific qualities and traits that are identifiable and recognizable to readers of literary works. Stereotypes function more as limited and often negative labels assigned to characters.

For example, the movie “The Breakfast Club” features characters that are far more stereotypical than archetypal. This movie features five representations of “typical” teenagers such as a dumb jock, conceited rich girl, skinny nerd, misunderstood rebel, and disaffected slacker that are forced to spend time together. These representations include what may appear to be archetypes in that they are identifiable by the audience . However, they function much more as stereotypes in the sense that their characterization is oversimplified and primarily negative. The characters assume their given stereotypical roles rather than display the complex characterization generally demonstrated by archetypes.

Writing Archetype

Overall, as a literary device, archetype functions as a means of portraying characters with recurring and identifiable traits and qualities that span time and culture. This is effective for readers in that archetypes set up recognizable patterns of characterization in literary works. When a reader is able to identify an archetypal character, they can anticipate that character’s role and/or purpose in the narrative. This not only leads to expectations, but engagement as well on the part of the reader.

It’s essential that writers bear in mind that their audience must have a reasonably clear understanding of how the character reflects a particular archetype in order for it to be effective. If the characterization of the archetype is not made clear to the reader, then that level of literary meaning will be lost. Of course, archetypal characters can be complex and fully realized. However, they must be recognizable as such for the reader on some level.

Here are some ways that writers benefit from incorporating archetype into their work:

Establish Universal Characters

Archetypal characters are recurrent when it comes to human experience, especially in art. A literary archetype represents a character that appears universal and therefore gives readers a sense of recognition and familiarity. This ability to relate to an archetypal character alleviates a writer’s burden of excessive or unnecessary description, explanation, and exposition . Due to a reader’s experience, they are able to understand traits and characteristics of archetypes in literature in an almost instinctual way without detailed explication .

Establish Contrasting Characters

Archetypes can also help writers establish contrasting characters, sometimes known as foils . In general, a literary work does not feature just one archetypal character. Since readers have an awareness of the inherent and typical characteristics of an archetype, this can create contrast against other characters in the narrative that are either archetypes themselves or not. Therefore, writers are able to create conflict and contrast between characters that are logical and recognizable for the reader.

Examples of Archetype in Literature

Archetype is an effective literary device as a means of creating characters with which the reader can identify. Here are some examples of literary archetypes and how they add to the significance of well-known literary works:

Example 1: Nick Carraway: Everyman ( The Great Gatsby , F. Scott Fitzgerald)

In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

In this passage, Fitzgerald establishes for the reader that Nick Carraway’s character is not just the narrator of the novel , but an “everyman” archetype as well. Though Nick’s father reminds him of “advantages” that he’s had, Nick is nevertheless considered the novel’s most relatable and “average” character. Therefore, as an everyman archetype, the reader is able to identify with Nick and consequently trust his observations and narration of the events of the story . This allows Nick’s character to influence the way in which the reader engages with the novel’s characters and events, as his everyman actions and interactions become vicarious experiences for Fitzgerald’s audience as well.

Example 2: Ma Joad: Caregiver ( The Grapes of Wrath , John Steinbeck)

Her hazel eyes seemed to have experienced all possible tragedy and to have mounted pain and suffering like steps into a high calm and a superhuman understanding. She seemed to know, to accept, to welcome her position, the citadel of the family, the strong place that could not be taken. And since old Tom and the children could not know hurt or fear unless she acknowledged hurt and fear, she had practiced denying them in herself.

In Steinbeck’s heart-breaking novel, the female characters represent a life force. This is epitomized by Ma Joad’s character as a “caregiver” archetype. Ma Joad is not only literally a caregiver in the sense that she is the mother of the protagonist and cares for her family, but she is also an archetypal caregiver in the sense that she makes sacrifices in order to care for others. Readers’ recognition of the characterization of Ma Joad as a caregiver allows Steinbeck to portray her as a traditional and symbolic mother figure.

However, Steinbeck elaborates on this archetype by portraying the effects of these caregiver traits on Ma Joad’s character. Rather than establishing her as a passive maternal character which would be identifiable and understood by a collective readership, Steinbeck reveals the universal consequences of this archetype’s traits on the character herself. Ma Joad is a universal character, yet her character also has a universal understanding and experience of tragedy and suffering. This makes her role and sacrifices as a caregiver even more meaningful.

Example 3: Sancho Panza: Jester ( Don Quixote , Miguel de Cervantes)

The most perceptive character in a play is the fool, because the man who wishes to seem simple cannot possibly be a simpleton.

In Miguel de Cervantes’ novel, Sancho Panza reflects the complexity and importance of the “jester” archetype. As Don Quixote’s sidekick, Sancho Panza provides humor and comic relief as a contrast to the title character’s idealism. However, as Sancho Panza’s character becomes more developed in the novel, his jester archetype develops as well into a voice of reason and example of empathy and loyalty. This is beneficial for the reader in that, though they are contrasting characters, Sancho Panza as a jester beside Don Quixote becomes a more legitimate and influential character. In turn, the jester archetype legitimizes the protagonist as well, making the novel’s fool the “most perceptive character.”

Related posts:

- Archetype of Imagination

- Caregiver Archetype

- Creator Archetype

- Customer Archetype

- Goddess Archetype

- Jester Archetype

- King Archetype

- Lover Archetype

- Magician Archetype

- Mother Archetype

- Maiden Archetype

- Outlaw Archetype

- Queen Archetype

- Quest Archetype

- Ruler Archetype

- Sage Archetype

- Temptress Archetype

- Scapegoat Archetype

- Shadow Archetype

- Siren Archetype

- Sophisticate Archetype

- Trickster Archetype

- Warrior Archetype

- 10 Archetype Examples in Movies

- Anti-Hero Archetype

- Damsel in Distress Archetype

- Earth Mother Archetype

- Dark Magician Archetype

- Wild Woman Archetype

Post navigation

8 Key Archetypes of the Hero’s Journey

by Lewis / July 14, 2018 / Character Development

Archetypes are something we experience every day…

An older coworker passing along important tips at your new job or a friend turns out to be talking behind your back. Most of us can recognize these as archetypes, but can we apply these familiar patterns to our fictional worlds and characters? The answer is a resounding yes!

Just as we see these character archetypes mirrored in our own lives, they’ll show up in our storytelling as well. Not only do they provide guidelines for making our characters feel like real people, but they can add a whole new layer of complexity and depth to our stories too.

What Is an Archetype?

- 1 What Is an Archetype?

- 2 Our Case Study: Solo

- 3.1 The Hero:

- 3.2 The Shadow:

- 3.3 The Mentor:

- 3.4 The Ally:

- 3.5 The Threshold Guardian:

- 3.6 The Herald:

- 3.7 The Trickster:

- 3.8 The Shapeshifter:

- 4 Repeat Archetypes and How They Work

- 5 Using Archetypes in Your Own Novel

An archetype is a repeated motif or trait found in storytelling.

Based on that definition, you might initially think of the classic “damsel in distress” or “knight in shining armor” from European fairy tales. Both of these do fall under the umbrella of archetypes, however, these aren’t the archetypes we’ll be exploring here.

Instead, the character archetypes of the Hero’s Journey are universal archetypes, roles all characters can fill at different points along their journey. These archetypes help you flesh out your story with a complete cast, while ensuring no character exists without a purpose.

“The archetypes are part of the universal language of storytelling, and a command of their energy is as essential to the writer as breathing.” – Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey

While most of these ideas originated with Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth and the Hero’s Journey, these eight universal archetypes are actually based on Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey. This book is beyond excellent, and breaks down the ideas of Campbell into a more usable storytelling guide—versus the highly academic The Hero With a Thousand Faces .

Both books are well worth your time, but we’ll be covering Vogler’s description of character archetypes here.

Of course, throughout this article I’ll assume you have at least a basic understanding of the Hero’s Journey. If you’re not familiar with this story structure, then check out my breakdown of the Hero’s Journey here.

Our Case Study: Solo

Rather, Solo is great for studying universal archetypes because each of its characters exhibits archetypal roles in interesting ways. Far from being stereotypes, Solo proves that these universal archetypes are the building blocks for forming unique characters.

For those unfamiliar with the movie, Solo is the origin story of Han Solo from the original Star Wars trilogy—and there will be major spoilers for Solo in this article.

Please enter at your own risk.

If you wish to continue but need a refresher on the plot, check out the Movie Structure Archives entry for Solo. It’ll give you a full breakdown of all the plot points I’ll be referencing here.

The 8 Universal Character Archetypes

You’re likely already familiar with the basics of the Hero archetype. After all, your protagonist will fill this role for most of your story as they overcome their flaws, drive your plot forward, and make important sacrifices.

Ultimately, their decisions will determine the outcome of the Climax .

However, other characters can also wear the Hero archetype at different points in your story. An Ally may become the Hero while your protagonist is incapacitated, or a Trickster may face a sudden change of heart. This dynamic allows other characters to temporarily take the spotlight and fulfill important story functions or resolve subplots.

In our case study, Han Solo fills the role of the Hero, though various Allies such as Val also fill it under special circumstances.

This makes sense because—beyond being on all the posters—this is Han’s journey. He grows the most from beginning to end, and is the catalyst for the movie’s progression. When the cast gets into a tight spot with Dryden Vos, it’s Han’s choices that propel them into the conflict. Not only that, but he is who the audience identifies with the most, meaning he checks all the boxes of the Hero archetype.

Of course, because the Hero is such a central archetype, it also has a whole host of specific traits and trials that go along with it. For more on the Hero’s character arc, check out this article.

The Shadow:

Just as the Hero archetype aligns with your protagonist, the Shadow is linked to your antagonist. This archetype seeks the antithesis of your Hero’s goals, often the destruction of what the Hero wishes to preserve.

Essentially, the Shadow embodies the dark aspects of the Hero.

The Shadow is meant to personify the suppressed wounds and inner struggles that the Hero will need to overcome—and this is why antagonists are often called “foil characters.” They’re a warning about what your protagonist will become if they fail to learn.

Of course, just like many characters can act as the Hero, many characters take on aspects of the Shadow. Your Hero may behave like the Shadow in moments. Allies, Heralds, and Threshold Guardians may do so as well, allowing you to create depth in characters that have thus far served only one purpose.

In Solo, Dryden Vos—from his name to his appearance and demeanor—screams antagonist. Because of this, it’s fairly obvious that Vos serves as the Shadow for most of the story.

However, he’s not the only character who plays this role.

While it’s easy to see Vos as the Shadow, Qi’ra actually fills this archetype in an even more crucial way. You see, Qi’ra’s role as a Shadow is intrinsically tied to Han’s character arc. Both begin from the same place and both are seeking to escape to a better life, but where Han’s journey molds him into a Hero, Qi’ra becomes a Shadow. This is a powerful contrast, and one we’ll be returning to later in the article.

The Mentor:

Acting as the Hero’s main guidance throughout their journey, the Mentor comes in many forms, but they always serve a critical purpose.

An elderly woman giving a soon-to-be bride a magic mirror to see the true face of her new husband or a veteran sports coach training young players both embody the Mentor archetype. This archetype is there to equip the Hero through knowledge, encouragement, and skills that allow them to overcome the conflict of the story and eventually surpass their flaws.

Of course, Mentors are a great opportunity to add depth to a story.

Because of this, Mentors often take on aspects of Threshold Guardians as Heroes prove their worth in exchange for help. Meanwhile, Shadow Mentors may seem to guide the Hero while actually misleading them—sometimes maliciously, sometimes mistakenly.

For example, while Han works under the guidance of a variety of Mentors throughout Solo , Tobias Beckett fills this role most often. He guides Han in how to deal with Vos, he teaches Han about this new world of crime, and he encourages Han at every step to leave it. Tobias clearly wears the mask of the Mentor archetype, but we’ll be coming back to him soon, as that isn’t the only archetype he wears.

The third of the well-known archetypes, Allies are seen in every story.

After all, Heroes need a friend to lean on, someone to lighten the load of the journey or to practice their growing skills with. That’s the role of the Ally, seen through characters like Samwise Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings , or Toto in The Wizard of Oz .

Because of how broad this archetype is, it serves many functions and can take on the aspects of many other archetypes. An Ally might act as a Mentor or may descend into a period of being a Shadow or Trickster. Thanks to this complexity, Allies are a great tool for humanizing your Hero, relieving tension, and furthering explore your story’s themes through subplots.

Fortunately, Ally archetypes are usually easy to identify, and primary Ally for Han is Chewbacca.

Audiences knew Chewie well before the story of Solo began, and he has served the same Ally role throughout the Star Wars series. Chewie is someone for Han to banter with and rely on, and he ends the movie as Han’s only lasting companion. While other characters such as Lando and Qi’ra wear the Ally archetype for only a short period of time, Chewie remains an Ally archetype for the entirety of Han’s life.

The Threshold Guardian:

Often an aspect of the Shadow, Threshold Guardians are there to represent the fears of your Hero and to challenge them as they progress along their journey. Of course, much like the midterm exams you may have had in school, Threshold Guardians aren’t the final test. Still, without your Hero proving they’ve mastered their new skills, these Guardians will prevent them from reaching their final test at all.

While Threshold Guardians are often henchmen of the Shadow, Mentors and Allies can also fulfill this role. For example, an Ally who has second thoughts about their quest might challenge the resolve of your Hero, forcing them to overcome their own doubts to convince their uncertain ally.

One of the primary Threshold Guardians on Han’s journey—though there are many—is a familiar character: Tobias Beckett.

Beckett’s role as a Threshold Guardian cannot go understated, and he actually embodies this role before he takes on the mantle of Mentor. When Han is struggling to get out of the Imperial Army, Tobias refuses to allow him into his gang and even gives him up to Imperial forces as a traitor. Fortunately, Han is persistent, and proves his value to the gang through his quick thinking. Only after he proves himself does Tobias allow him to join, fulfilling the role of the Threshold Guardian.

The Herald:

The Herald’s name gives away much of its function—your story’s Herald is there to give the Call to Adventure, to foreshadow the coming conflict, and to warn the audience that your Hero’s Ordinary World will soon fall away.

Based on this description, the Herald may sound like another aspect of the Shadow, and it certainly can be. However, it can also be a positive force, such as the spitfire young girl who coaxes the lonely bounty hunter out of his shell in, True Grit .

In Solo , the Herald is a character we’ve mentioned before.

From the start of Han’s journey, his mission has been the same—go back for Qi’ra. When he gets caught up with Beckett and his gang, this is still his focus. However, when he finally finds Qi’ra again, she’s not the scrappy child he remembers. This Qi’ra is powerful, elegant, respected, and under the frightening control of Vos.

Suddenly the dynamics of Han’s journey have shifted, and he can no longer live with the “one-day” mentality he had previously been had. His goal becomes urgent and firmly focused on the present, all thanks to Qi’ra’s role as the Herald.

The Trickster:

Next up, we’ll be looking at the Trickster archetype. A classic comedy character seen in sidekicks from a variety of genres, Tricksters are a great way to manage the pace your story. These moments of comedy relieve the tension built up by more action-packed moments, letting your readers take a moment to breathe.

Used in reverse, Tricksters are also great at increasing the weight of key scenes.

A character that’s been light-hearted throughout your story can suddenly turn serious as they approach the Climax. Your readers will take notice, and will soon find themselves anxiously wondering about what’s to come. If this previously comedic character is suddenly changing their tune, then the stakes of the adventure must be rising.

Serving as the Trickster in Solo , we have another repeat character from the original Star Wars trilogy: Lando Calrissian, along with his droid L3-37.

They provide the audience with plenty of antics and absurdities, lightening the mood between darker segments. For periods of the story Lando also serves as an Ally, but his true alliance is always with himself. Fortunately this isn’t malicious and is instead played for laughs, making him a strong Trickster character.

The Shapeshifter:

If you like to fill your stories with suspense you likely have one—if not many—important Shapeshifter characters.

Like the example of the traitorous friend we talked about at the start of this article, the Shapeshifter shows a different face when looked at from different angles. Seductresses, both sexually and in other ways, work to trick the Hero by presenting an alluring offer to their problems while seeking to trap or defeat them when they aren’t looking.

Shapeshifters aren’t always Shadows either.

For instance, the Hero may believe they have an Ally only to find a Shadow, leaving them betrayed and confused. Other times the Shapeshifter may start out as a Shadow, before becoming an Ally later on. This flexibility lets you layer the Shapeshifter archetype into existing characters to create suspense and tension in your story.

Unfortunately for Han, one of his key allies and his Mentor both embody the Shapeshifter archetype, causing suffering on two fronts. For starters, Beckett spends much of the movie acting as a pseudo father-figure, only to betray Han to Vos. This forces Han to kill Beckett to save himself and Chewie, robbing him of his Mentor figure.

Qi’ra engages in a similar betrayal after killing Vos. Han believes he has achieved his goal and that the pair can finally be together, but Qi’ra reveals her allegiance to the Sith and abandons Han. Her betrayal is arguably even more painful for Han than Beckett’s, as it robs him of everything he’s worked towards on his journey.

Repeat Archetypes and How They Work

By this point in the article, you may be wondering…

Why does Qi’ra show up in so many of these archetypes?