- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Christopher Columbus

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

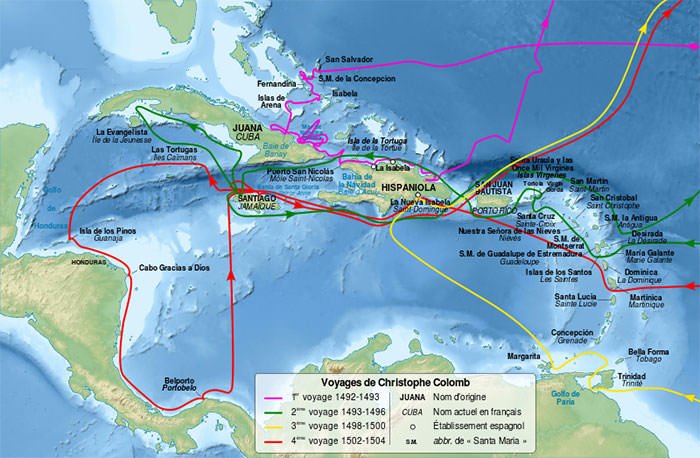

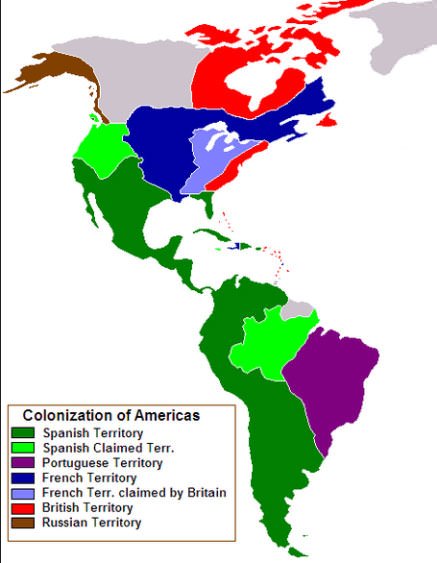

The explorer Christopher Columbus made four trips across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain: in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502. He was determined to find a direct water route west from Europe to Asia, but he never did. Instead, he stumbled upon the Americas. Though he did not “discover” the so-called New World—millions of people already lived there—his journeys marked the beginning of centuries of exploration and colonization of North and South America.

Christopher Columbus and the Age of Discovery

During the 15th and 16th centuries, leaders of several European nations sponsored expeditions abroad in the hope that explorers would find great wealth and vast undiscovered lands. The Portuguese were the earliest participants in this “ Age of Discovery ,” also known as “ Age of Exploration .”

Starting in about 1420, small Portuguese ships known as caravels zipped along the African coast, carrying spices, gold and other goods as well as enslaved people from Asia and Africa to Europe.

Did you know? Christopher Columbus was not the first person to propose that a person could reach Asia by sailing west from Europe. In fact, scholars argue that the idea is almost as old as the idea that the Earth is round. (That is, it dates back to early Rome.)

Other European nations, particularly Spain, were eager to share in the seemingly limitless riches of the “Far East.” By the end of the 15th century, Spain’s “ Reconquista ”—the expulsion of Jews and Muslims out of the kingdom after centuries of war—was complete, and the nation turned its attention to exploration and conquest in other areas of the world.

Early Life and Nationality

Christopher Columbus, the son of a wool merchant, is believed to have been born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. When he was still a teenager, he got a job on a merchant ship. He remained at sea until 1476, when pirates attacked his ship as it sailed north along the Portuguese coast.

The boat sank, but the young Columbus floated to shore on a scrap of wood and made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually studied mathematics, astronomy, cartography and navigation. He also began to hatch the plan that would change the world forever.

Christopher Columbus' First Voyage

At the end of the 15th century, it was nearly impossible to reach Asia from Europe by land. The route was long and arduous, and encounters with hostile armies were difficult to avoid. Portuguese explorers solved this problem by taking to the sea: They sailed south along the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope.

But Columbus had a different idea: Why not sail west across the Atlantic instead of around the massive African continent? The young navigator’s logic was sound, but his math was faulty. He argued (incorrectly) that the circumference of the Earth was much smaller than his contemporaries believed it was; accordingly, he believed that the journey by boat from Europe to Asia should be not only possible, but comparatively easy via an as-yet undiscovered Northwest Passage .

He presented his plan to officials in Portugal and England, but it was not until 1492 that he found a sympathetic audience: the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile .

Columbus wanted fame and fortune. Ferdinand and Isabella wanted the same, along with the opportunity to export Catholicism to lands across the globe. (Columbus, a devout Catholic, was equally enthusiastic about this possibility.)

Columbus’ contract with the Spanish rulers promised that he could keep 10 percent of whatever riches he found, along with a noble title and the governorship of any lands he should encounter.

Where Did Columbus' Ships, Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria, Land?

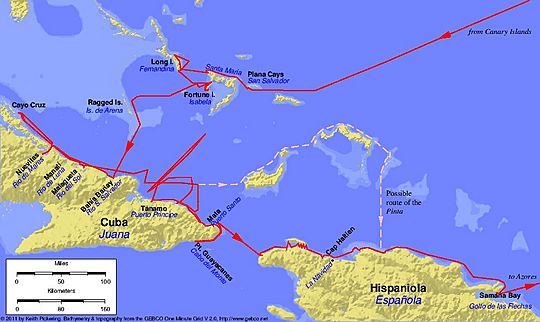

On August 3, 1492, Columbus and his crew set sail from Spain in three ships: the Niña , the Pinta and the Santa Maria . On October 12, the ships made landfall—not in the East Indies, as Columbus assumed, but on one of the Bahamian islands, likely San Salvador.

For months, Columbus sailed from island to island in what we now know as the Caribbean, looking for the “pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices, and other objects and merchandise whatsoever” that he had promised to his Spanish patrons, but he did not find much. In January 1493, leaving several dozen men behind in a makeshift settlement on Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he left for Spain.

He kept a detailed diary during his first voyage. Christopher Columbus’s journal was written between August 3, 1492, and November 6, 1492 and mentions everything from the wildlife he encountered, like dolphins and birds, to the weather to the moods of his crew. More troublingly, it also recorded his initial impressions of the local people and his argument for why they should be enslaved.

“They… brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells," he wrote. "They willingly traded everything they owned… They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features… They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron… They would make fine servants… With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

Columbus gifted the journal to Isabella upon his return.

Christopher Columbus's Later Voyages

About six months later, in September 1493, Columbus returned to the Americas. He found the Hispaniola settlement destroyed and left his brothers Bartolomeo and Diego Columbus behind to rebuild, along with part of his ships’ crew and hundreds of enslaved indigenous people.

Then he headed west to continue his mostly fruitless search for gold and other goods. His group now included a large number of indigenous people the Europeans had enslaved. In lieu of the material riches he had promised the Spanish monarchs, he sent some 500 enslaved people to Queen Isabella. The queen was horrified—she believed that any people Columbus “discovered” were Spanish subjects who could not be enslaved—and she promptly and sternly returned the explorer’s gift.

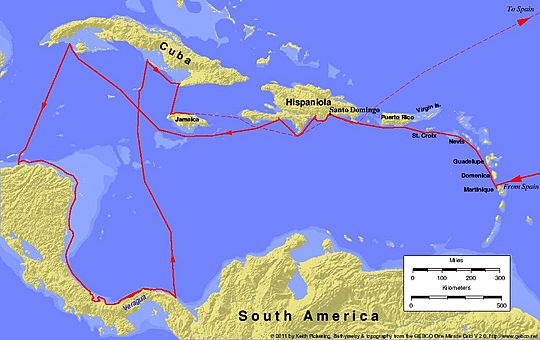

In May 1498, Columbus sailed west across the Atlantic for the third time. He visited Trinidad and the South American mainland before returning to the ill-fated Hispaniola settlement, where the colonists had staged a bloody revolt against the Columbus brothers’ mismanagement and brutality. Conditions were so bad that Spanish authorities had to send a new governor to take over.

Meanwhile, the native Taino population, forced to search for gold and to work on plantations, was decimated (within 60 years after Columbus landed, only a few hundred of what may have been 250,000 Taino were left on their island). Christopher Columbus was arrested and returned to Spain in chains.

In 1502, cleared of the most serious charges but stripped of his noble titles, the aging Columbus persuaded the Spanish crown to pay for one last trip across the Atlantic. This time, Columbus made it all the way to Panama—just miles from the Pacific Ocean—where he had to abandon two of his four ships after damage from storms and hostile natives. Empty-handed, the explorer returned to Spain, where he died in 1506.

Legacy of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus did not “discover” the Americas, nor was he even the first European to visit the “New World.” (Viking explorer Leif Erikson had sailed to Greenland and Newfoundland in the 11th century.)

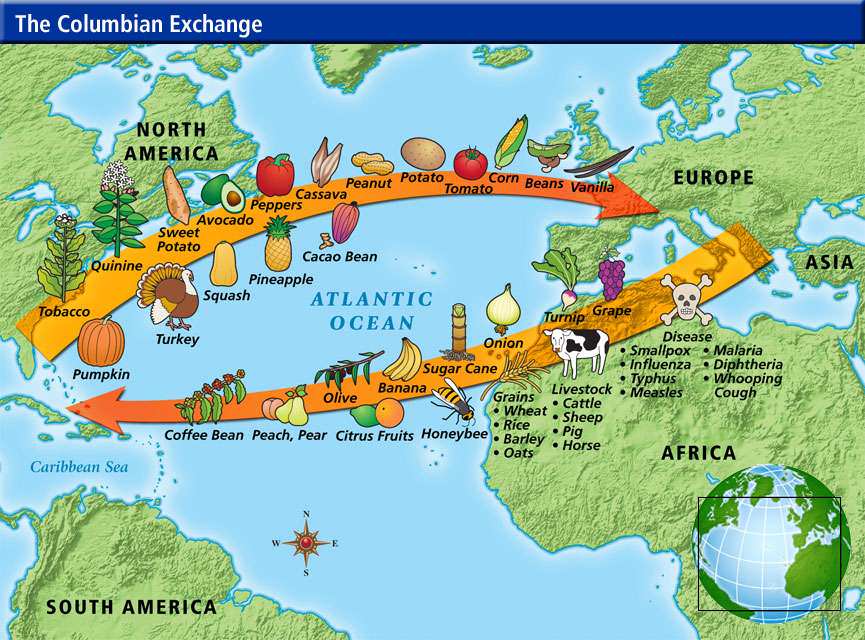

However, his journey kicked off centuries of exploration and exploitation on the American continents. The Columbian Exchange transferred people, animals, food and disease across cultures. Old World wheat became an American food staple. African coffee and Asian sugar cane became cash crops for Latin America, while American foods like corn, tomatoes and potatoes were introduced into European diets.

Today, Columbus has a controversial legacy —he is remembered as a daring and path-breaking explorer who transformed the New World, yet his actions also unleashed changes that would eventually devastate the native populations he and his fellow explorers encountered.

HISTORY Vault: Columbus the Lost Voyage

Ten years after his 1492 voyage, Columbus, awaiting the gallows on criminal charges in a Caribbean prison, plotted a treacherous final voyage to restore his reputation.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

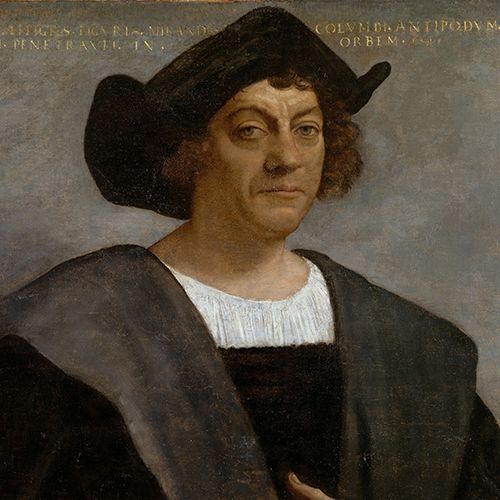

Christopher Columbus

Italian explorer Christopher Columbus discovered the “New World” of the Americas on an expedition sponsored by King Ferdinand of Spain in 1492.

c. 1451-1506

Quick Facts

Where was columbus born, first voyages, columbus’ 1492 route and ships, where did columbus land in 1492, later voyages across the atlantic, how did columbus die, santa maria discovery claim, columbian exchange: a complex legacy, columbus day: an evolving holiday, who was christopher columbus.

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator. In 1492, he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain in the Santa Maria , with the Pinta and the Niña ships alongside, hoping to find a new route to Asia. Instead, he and his crew landed on an island in present-day Bahamas—claiming it for Spain and mistakenly “discovering” the Americas. Between 1493 and 1504, he made three more voyages to the Caribbean and South America, believing until his death that he had found a shorter route to Asia. Columbus has been credited—and blamed—for opening up the Americas to European colonization.

FULL NAME: Cristoforo Colombo BORN: c. 1451 DIED: May 20, 1506 BIRTHPLACE: Genoa, Italy SPOUSE: Filipa Perestrelo (c. 1479-1484) CHILDREN: Diego and Fernando

Christopher Columbus, whose real name was Cristoforo Colombo, was born in 1451 in the Republic of Genoa, part of what is now Italy. He is believed to have been the son of Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa and had four siblings: brothers Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo, and a sister named Bianchinetta. He was an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business and studied sailing and mapmaking.

In his 20s, Columbus moved to Lisbon, Portugal, and later resettled in Spain, which remained his home base for the duration of his life.

Columbus first went to sea as a teenager, participating in several trading voyages in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. One such voyage, to the island of Khios, in modern-day Greece, brought him the closest he would ever come to Asia.

His first voyage into the Atlantic Ocean in 1476 nearly cost him his life, as the commercial fleet he was sailing with was attacked by French privateers off the coast of Portugal. His ship was burned, and Columbus had to swim to the Portuguese shore.

He made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually settled and married Filipa Perestrelo. The couple had one son, Diego, around 1480. His wife died when Diego was a young boy, and Columbus moved to Spain. He had a second son, Fernando, who was born out of wedlock in 1488 with Beatriz Enriquez de Arana.

After participating in several other expeditions to Africa, Columbus learned about the Atlantic currents that flow east and west from the Canary Islands.

The Asian islands near China and India were fabled for their spices and gold, making them an attractive destination for Europeans—but Muslim domination of the trade routes through the Middle East made travel eastward difficult.

Columbus devised a route to sail west across the Atlantic to reach Asia, believing it would be quicker and safer. He estimated the earth to be a sphere and the distance between the Canary Islands and Japan to be about 2,300 miles.

Many of Columbus’ contemporary nautical experts disagreed. They adhered to the (now known to be accurate) second-century BCE estimate of the Earth’s circumference at 25,000 miles, which made the actual distance between the Canary Islands and Japan about 12,200 statute miles. Despite their disagreement with Columbus on matters of distance, they concurred that a westward voyage from Europe would be an uninterrupted water route.

Columbus proposed a three-ship voyage of discovery across the Atlantic first to the Portuguese king, then to Genoa, and finally to Venice. He was rejected each time. In 1486, he went to the Spanish monarchy of Queen Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. Their focus was on a war with the Muslims, and their nautical experts were skeptical, so they initially rejected Columbus.

The idea, however, must have intrigued the monarchs, because they kept Columbus on a retainer. Columbus continued to lobby the royal court, and soon, the Spanish army captured the last Muslim stronghold in Granada in January 1492. Shortly thereafter, the monarchs agreed to finance his expedition.

In late August 1492, Columbus left Spain from the port of Palos de la Frontera. He was sailing with three ships: Columbus in the larger Santa Maria (a type of ship known as a carrack), with the Pinta and the Niña (both Portuguese-style caravels) alongside.

On October 12, 1492, after 36 days of sailing westward across the Atlantic, Columbus and several crewmen set foot on an island in present-day Bahamas, claiming it for Spain.

There, his crew encountered a timid but friendly group of natives who were open to trade with the sailors. They exchanged glass beads, cotton balls, parrots, and spears. The Europeans also noticed bits of gold the natives wore for adornment.

Columbus and his men continued their journey, visiting the islands of Cuba (which he thought was mainland China) and Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which Columbus thought might be Japan) and meeting with the leaders of the native population.

During this time, the Santa Maria was wrecked on a reef off the coast of Hispaniola. With the help of some islanders, Columbus’ men salvaged what they could and built the settlement Villa de la Navidad (“Christmas Town”) with lumber from the ship.

Thirty-nine men stayed behind to occupy the settlement. Convinced his exploration had reached Asia, he set sail for home with the two remaining ships. Returning to Spain in 1493, Columbus gave a glowing but somewhat exaggerated report and was warmly received by the royal court.

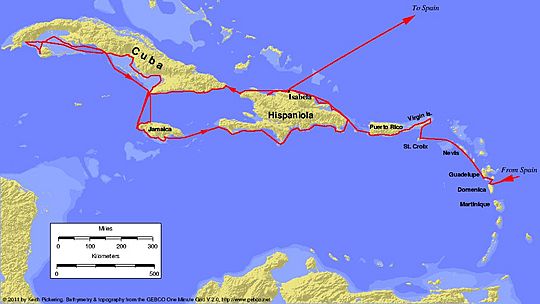

In 1493, Columbus took to the seas on his second expedition and explored more islands in the Caribbean Ocean. Upon arrival at Hispaniola, Columbus and his crew discovered the Navidad settlement had been destroyed with all the sailors massacred.

Spurning the wishes of the local queen, Columbus established a forced labor policy upon the native population to rebuild the settlement and explore for gold, believing it would be profitable. His efforts produced small amounts of gold and great hatred among the native population.

Before returning to Spain, Columbus left his brothers Bartholomew and Giacomo to govern the settlement on Hispaniola and sailed briefly around the larger Caribbean islands, further convincing himself he had discovered the outer islands of China.

It wasn’t until his third voyage that Columbus actually reached the South American mainland, exploring the Orinoco River in present-day Venezuela. By this time, conditions at the Hispaniola settlement had deteriorated to the point of near-mutiny, with settlers claiming they had been misled by Columbus’ claims of riches and complaining about the poor management of his brothers.

The Spanish Crown sent a royal official who arrested Columbus and stripped him of his authority. He returned to Spain in chains to face the royal court. The charges were later dropped, but Columbus lost his titles as governor of the Indies and, for a time, much of the riches made during his voyages.

After convincing King Ferdinand that one more voyage would bring the abundant riches promised, Columbus went on his fourth and final voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1502. This time he traveled along the eastern coast of Central America in an unsuccessful search for a route to the Indian Ocean.

A storm wrecked one of his ships, stranding the captain and his sailors on the island of Cuba. During this time, local islanders, tired of the Spaniards’ poor treatment and obsession with gold, refused to give them food.

In a spark of inspiration, Columbus consulted an almanac and devised a plan to “punish” the islanders by taking away the moon. On February 29, 1504, a lunar eclipse alarmed the natives enough to re-establish trade with the Spaniards. A rescue party finally arrived, sent by the royal governor of Hispaniola in July, and Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain in November 1504.

In the two remaining years of his life, Columbus struggled to recover his reputation. Although he did regain some of his riches in May 1505, his titles were never returned.

Columbus probably died of severe arthritis following an infection on May 20, 1506, in Valladolid, Spain. At the time of his death, he still believed he had discovered a shorter route to Asia.

There are questions about the location of his burial site. According to the BBC , Columbus’ remains moved at least three or four times over the course of 400 years—including from Valladolid to Seville, Spain, in 1509; then to Santo Domingo, in what is now the Dominican Republic, in 1537; then to Havana, Cuba, in 1795; and back to Seville in 1898. As a result, Seville and Santo Domingo have both laid claim to being Columbus’ true burial site. It is also possible his bones were mixed up with another person’s amid all of their travels.

In May 2014, Columbus made headlines as news broke that a team of archaeologists might have found the Santa Maria off the north coast of Haiti. Barry Clifford, the leader of this expedition, told the Independent newspaper that “all geographical, underwater topography and archaeological evidence strongly suggests this wreck is Columbus’ famous flagship the Santa Maria.”

After a thorough investigation by the U.N. agency UNESCO, it was determined the wreck dates from a later period and was located too far from shore to be the famed ship.

Columbus has been credited for opening up the Americas to European colonization—as well as blamed for the destruction of the native peoples of the islands he explored. Ultimately, he failed to find that what he set out for: a new route to Asia and the riches it promised.

In what is known as the Columbian Exchange, Columbus’ expeditions set in motion the widespread transfer of people, plants, animals, diseases, and cultures that greatly affected nearly every society on the planet.

The horse from Europe allowed Native American tribes in the Great Plains of North America to shift from a nomadic to a hunting lifestyle. Wheat from the Old World fast became a main food source for people in the Americas. Coffee from Africa and sugar cane from Asia became major cash crops for Latin American countries. And foods from the Americas, such as potatoes, tomatoes and corn, became staples for Europeans and helped increase their populations.

The Columbian Exchange also brought new diseases to both hemispheres, though the effects were greatest in the Americas. Smallpox from the Old World killed millions, decimating the Native American populations to mere fractions of their original numbers. This more than any other factor allowed for European domination of the Americas.

The overwhelming benefits of the Columbian Exchange went to the Europeans initially and eventually to the rest of the world. The Americas were forever altered, and the once vibrant cultures of the Indigenous civilizations were changed and lost, denying the world any complete understanding of their existence.

As more Italians began to immigrate to the United States and settle in major cities during the 19 th century, they were subject to religious and ethnic discrimination. This included a mass lynching of 11 Sicilian immigrants in 1891 in New Orleans.

Just one year after this horrific event, President Benjamin Harrison called for the first national observance of Columbus Day on October 12, 1892, to mark the 400 th anniversary of his arrival in the Americas. Italian-Americans saw this honorary act for Columbus as a way of gaining acceptance.

Colorado became the first state to officially observe Columbus Day in 1906 and, within five years, 14 other states followed. Thanks to a joint resolution of Congress, the day officially became a federal holiday in 1934 during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt . In 1970, Congress declared the holiday would fall on the second Monday in October each year.

But as Columbus’ legacy—specifically, his exploration’s impacts on Indigenous civilizations—began to draw more criticism, more people chose not to take part. As of 2023, approximately 29 states no longer celebrate Columbus Day , and around 195 cities have renamed it or replaced with the alternative Indigenous Peoples Day. The latter isn’t an official holiday, but the federal government recognized its observance in 2022 and 2023. President Joe Biden called it “a day in honor of our diverse history and the Indigenous peoples who contribute to shaping this nation.”

One of the most notable cities to move away from celebrating Columbus Day in recent years is the state capital of Columbus, Ohio, which is named after the explorer. In 2018, Mayor Andrew Ginther announced the city would remain open on Columbus Day and instead celebrate a holiday on Veterans Day. In July 2020, the city also removed a 20-plus-foot metal statue of Columbus from the front of City Hall.

- I went to sea from the most tender age and have continued in a sea life to this day. Whoever gives himself up to this art wants to know the secrets of Nature here below. It is more than forty years that I have been thus engaged. Wherever any one has sailed, there I have sailed.

- Speaking of myself, little profit had I won from twenty years of service, during which I have served with so great labors and perils, for today I have no roof over my head in Castile; if I wish to sleep or eat, I have no place to which to go, save an inn or tavern, and most often, I lack the wherewithal to pay the score.

- They say that there is in that land an infinite amount of gold; and that the people wear corals on their heads and very large bracelets of coral on their feet and arms; and that with coral they adorn and inlay chairs and chests and tables.

- This island and all the others are very fertile to a limitless degree, and this island is extremely so. In it there are many harbors on the coast of the sea, beyond comparison with others that I know in Christendom, and many rivers, good and large, which is marvelous.

- Our Almighty God has shown me the highest favor, which, since David, he has not shown to anybody.

- Already the road is opened to gold and pearls, and it may surely be hoped that precious stones, spices, and a thousand other things, will also be found.

- I have now seen so much irregularity, that I have come to another conclusion respecting the earth, namely, that it is not round as they describe, but of the form of a pear.

- In all the countries visited by your Highnesses’ ships, I have caused a high cross to be fixed upon every headland and have proclaimed, to every nation that I have discovered, the lofty estate of your Highnesses and of your court in Spain.

- I ought to be judged as a captain sent from Spain to the Indies, to conquer a nation numerous and warlike, with customs and religions altogether different to ours.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Possible Evidence of Amelia Earhart’s Plane

Charles Lindbergh

Was Christopher Columbus a Hero or Villain?

History & Culture

Barron Trump

Alexander McQueen

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Michelle Obama

Rare Vintage Photos of Celebrities at the Opera

The 12 Greatest Unsolved Disappearances

Henrietta Lacks

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

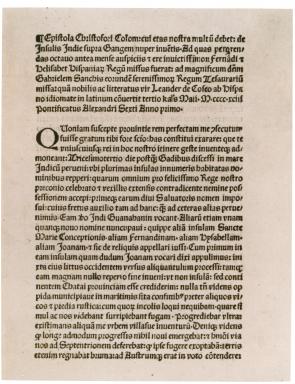

Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493

A spotlight on a primary source by christopher columbus.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Spain to find an all-water route to Asia. On October 12, more than two months later, Columbus landed on an island in the Bahamas that he called San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani.

For nearly five months, Columbus explored the Caribbean, particularly the islands of Juana (Cuba) and Hispaniola (Santo Domingo), before returning to Spain. He left thirty-nine men to build a settlement called La Navidad in present-day Haiti. He also kidnapped several Native Americans (between ten and twenty-five) to take back to Spain—only eight survived. Columbus brought back small amounts of gold as well as native birds and plants to show the richness of the continent he believed to be Asia.

When Columbus arrived back in Spain on March 15, 1493, he immediately wrote a letter announcing his discoveries to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, who had helped finance his trip. The letter was written in Spanish and sent to Rome, where it was printed in Latin by Stephan Plannck. Plannck mistakenly left Queen Isabella’s name out of the pamphlet’s introduction but quickly realized his error and reprinted the pamphlet a few days later. The copy shown here is the second, corrected edition of the pamphlet.

The Latin printing of this letter announced the existence of the American continent throughout Europe. “I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance,” Columbus wrote.

In addition to announcing his momentous discovery, Columbus’s letter also provides observations of the native people’s culture and lack of weapons, noting that “they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror.” Writing that the natives are “fearful and timid . . . guileless and honest,” Columbus declares that the land could easily be conquered by Spain, and the natives “might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain.”

An English translation of this document is available.

I have determined to write you this letter to inform you of everything that has been done and discovered in this voyage of mine.

On the thirty-third day after leaving Cadiz I came into the Indian Sea, where I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance. The island called Juana, as well as the others in its neighborhood, is exceedingly fertile. It has numerous harbors on all sides, very safe and wide, above comparison with any I have ever seen. Through it flow many very broad and health-giving rivers; and there are in it numerous very lofty mountains. All these island are very beautiful, and of quite different shapes; easy to be traversed, and full of the greatest variety of trees reaching to the stars. . . .

In the island, which I have said before was called Hispana , there are very lofty and beautiful mountains, great farms, groves and fields, most fertile both for cultivation and for pasturage, and well adapted for constructing buildings. The convenience of the harbors in this island, and the excellence of the rivers, in volume and salubrity, surpass human belief, unless on should see them. In it the trees, pasture-lands and fruits different much from those of Juana. Besides, this Hispana abounds in various kinds of species, gold and metals. The inhabitants . . . are all, as I said before, unprovided with any sort of iron, and they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror. . . . But when they see that they are safe, and all fear is banished, they are very guileless and honest, and very liberal of all they have. No one refuses the asker anything that he possesses; on the contrary they themselves invite us to ask for it. They manifest the greatest affection towards all of us, exchanging valuable things for trifles, content with the very least thing or nothing at all. . . . I gave them many beautiful and pleasing things, which I had brought with me, for no return whatever, in order to win their affection, and that they might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain; and that they might be eager to search for and gather and give to us what they abound in and we greatly need.

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction and transcript in order to answer these questions.

- Columbus described the Natives he first encountered as “timid and full of fear.” Why did he then capture some Natives and bring them aboard his ships?

- Imagine the thoughts of the Europeans as they first saw land in the “New World.” What do you think would have been their most immediate impression? Explain your answer.

- Which of the items Columbus described would have been of most interest to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella? Why?

- Why did Columbus describe the islands and their inhabitants in great detail?

- It is said that this voyage opened the period of the “Columbian Exchange.” Why do you think that term has been attached to this period of time?

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

The Ages of Exploration

Christopher columbus, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

He is credited for discovering the Americas in 1492, although we know today people were there long before him; his real achievement was that he opened the door for more exploration to a New World.

Name : Christopher Columbus [Kri-stə-fər] [Kə-luhm-bəs]

Birth/Death : 1451 - 1506

Nationality : Italian

Birthplace : Genoa, Italy

Christopher Columbus leaving Palos, Spain

Christopher Columbus aboard the "Santa Maria" leaving Palos, Spain on his first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. The Mariners' Museum 1933.0746.000001

Introduction We know that In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. But what did he actually discover? Christopher Columbus (also known as (Cristoforo Colombo [Italian]; Cristóbal Colón [Spanish]) was an Italian explorer credited with the “discovery” of the America’s. The purpose for his voyages was to find a passage to Asia by sailing west. Never actually accomplishing this mission, his explorations mostly included the Caribbean and parts of Central and South America, all of which were already inhabited by Native groups.

Biography Early Life Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, part of present-day Italy, in 1451. His parents’ names were Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo; and a sister named Bianchinetta. Christopher became an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business, but he also studied mapmaking and sailing as well. He eventually left his father’s business to join the Genoese fleet and sail on the Mediterranean Sea. 1 After one of his ships wrecked off the coast of Portugal, he decided to remain there with his younger brother Bartholomew where he worked as a cartographer (mapmaker) and bookseller. Here, he married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz and had two sons Diego and Fernando.

Christopher Columbus owned a copy of Marco Polo’s famous book, and it gave him a love for exploration. In the mid 15th century, Portugal was desperately trying to find a faster trade route to Asia. Exotic goods such as spices, ivory, silk, and gems were popular items of trade. However, Europeans often had to travel through the Middle East to reach Asia. At this time, Muslim nations imposed high taxes on European travels crossing through. 2 This made it both difficult and expensive to reach Asia. There were rumors from other sailors that Asia could be reached by sailing west. Hearing this, Christopher Columbus decided to try and make this revolutionary journey himself. First, he needed ships and supplies, which required money that he did not have. He went to King John of Portugal who turned him down. He then went to the rulers of England, and France. Each declined his request for funding. After seven years of trying, he was finally sponsored by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain.

Voyages Principal Voyage Columbus’ voyage departed in August of 1492 with 87 men sailing on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Columbus commanded the Santa María, while the Niña was led by Vicente Yanez Pinzon and the Pinta by Martin Pinzon. 3 This was the first of his four trips. He headed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean. On October 12 land was sighted. He gave the first island he landed on the name San Salvador, although the native population called it Guanahani. 4 Columbus believed that he was in Asia, but was actually in the Caribbean. He even proposed that the island of Cuba was a part of China. Since he thought he was in the Indies, he called the native people “Indians.” In several letters he wrote back to Spain, he described the landscape and his encounters with the natives. He continued sailing throughout the Caribbean and named many islands he encountered after his ship, king, and queen: La Isla de Santa María de Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabella.

It is hard to determine specifically which islands Columbus visited on this voyage. His descriptions of the native peoples, geography, and plant life do give us some clues though. One place we do know he stopped was in present-day Haiti. He named the island Hispaniola. Hispaniola today includes both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In January of 1493, Columbus sailed back to Europe to report what he found. Due to rough seas, he was forced to land in Portugal, an unfortunate event for Columbus. With relations between Spain and Portugal strained during this time, Ferdinand and Isabella suspected that Columbus was taking valuable information or maybe goods to Portugal, the country he had lived in for several years. Those who stood against Columbus would later use this as an argument against him. Eventually, Columbus was allowed to return to Spain bringing with him tobacco, turkey, and some new spices. He also brought with him several natives of the islands, of whom Queen Isabella grew very fond.

Subsequent Voyages Columbus took three other similar trips to this region. His second voyage in 1493 carried a large fleet with the intention of conquering the native populations and establishing colonies. At one point, the natives attacked and killed the settlers left at Fort Navidad. Over time the colonists enslaved many of the natives, sending some to Europe and using many to mine gold for the Spanish settlers in the Caribbean. The third trip was to explore more of the islands and mainland South America further. Columbus was appointed the governor of Hispaniola, but the colonists, upset with Columbus’ leadership appealed to the rulers of Spain, who sent a new governor: Francisco de Bobadilla. Columbus was taken prisoner on board a ship and sent back to Spain.

On his fourth and final journey west in 1502 Columbus’s goal was to find the “Strait of Malacca,” to try to find India. But a hurricane, then being denied entrance to Hispaniola, and then another storm made this an unfortunate trip. His ship was so badly damaged that he and his crew were stranded on Jamaica for two years until help from Hispaniola finally arrived. In 1504, Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain .

Later Years and Death Columbus reached Spain in November 1504. He was not in good health. He spent much of the last of his life writing letters to obtain the percentage of wealth overdue to be paid to him, and trying to re-attain his governorship status, but was continually denied both. Columbus died at Valladolid on May 20, 1506, due to illness and old age. Even until death, he still firmly believing that he had traveled to the eastern part of Asia.

Legacy Columbus never made it to Asia, nor did he truly discover America. His “re-discovery,” however, inspired a new era of exploration of the American continents by Europeans. Perhaps his greatest contribution was that his voyages opened an exchange of goods between Europe and the Americas both during and long after his journeys. 5 Despite modern criticism of his treatment of the native peoples there is no denying that his expeditions changed both Europe and America. Columbus day was made a federal holiday in 1971. It is recognized on the second Monday of October.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 30.

- Fleming, Off the Map, 30

- William D. Phillips and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 142-143.

- Phillips and Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus, 155.

- Robin S. Doak, Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World (Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005), 92.

Bibliography

Doak, Robin. Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Map of Voyages

Click below to view an example of the explorer’s voyages. Use the tabs on the left to view either 1 or multiple journeys at a time, and click on the icons to learn more about the stops, sites, and activities along the way.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

By AD. F. Bandelier Transcribed by Janet van Heyst Dedicated in honor of Fr. Moses M. Nagy, O. Cist.

(Italian CRISTOFORO COLOMBO; Spanish CRISTOVAL COLON.) Born at Genoa, or on Genoese territory, probably 1451; died at Valladolid, Spain, 20 May 1506.

The early age at which he began his career as a sailor is not surprising for a native of Genoa, as the Genoese were most enterprising and daring seamen. Columbus is said in his early days to have been a corsair, especially in the war against the Moors, themselves merciless pirates. He is also supposed to have sailed as far south as the coast of Guinea before he was sixteen years of age. Certain it is that while quite young he became a thorough and practical navigator, and later acquired a fair knowledge of astronomy. He also gained a wide acquaintance with works on cosmography such as Ptolemy and the “Imago Mundi” of Cardinal d’Ailly, besides entering into communication with the cosmographers of his time. The fragment of a treatise written by him and called by his son Fernando “The Five Habitable Zones of the Earth” shows a degree of information unusual for a sailor of his day. As in the case of most of the documents relating to the life of Columbus the genuineness of the letters written in 1474 by Paolo Toscanelli, a renowned physicist of Florence, to Columbus and a member of the household of King Alfonso V of Portugal, has been attacked on the ground of the youth of Columbus, although they bears signs of authenticity. The experiences and researches referred to fit in satisfactorily with the subsequent achievements of Columbus. For the rest, the early part of Columbus’s life is interwoven with incidents, most of which are unsupported by evidence, though quite possible. His marriage about 1475 to a Portuguese lady whose name is given sometimes as Doña Felipa Moniz and sometimes as Doña Felipa Perestrella seems certain.

Columbus seems to have arrived in Portugal about 1471, although 1474 is also mentioned and supported by certain indications. He vainly tried to obtain the support of the King of Portugal for his scheme to discover the Far East by sailing westward, a scheme supposed to have been suggested by his brother Bartholomew, who is said to have been earning a livelihood at Lisbon by designing marine charts. Columbus went to Spain in 1485, and probably the first assistance he obtained there was from the Duke of Medina Celi, Don Luis de la Cerda, for whom he performed some services that brought him a compensation of 3000 maravedis in May, 1487. He lived about two years at the home of the duke and made unsuccessful endeavors to interest him in his scheme of maritime exploration. His attempts to secure the help of the Duke of Medina Sidonia were equally unproductive of results. No blame attaches to the noblemen for declining to undertake an enterprise which only rulers of nations could properly carry out. Between 1485 and 1488 Columbus began his relations with Doña Beatriz Enriquez de Arana, or Harana, of a good family of the city of Cordova, from which sprang his much beloved son Fernando, next to Christopher and his brother Bartholomew the most gifted of the Colombos.

Late in 1485 or early in 1486, Columbus appeared twice before the court to submit his plans and while the Duke of Medina Celi may have assisted him to some extent, the chief support came from the royal treasurer, Alonzo de Quintanilla, Friar Antonio de Marchena (confounded by Irving with Father Perez of La Rábida), and Diego de Deza, Bishop of Placencia. Columbus himself declared that these two priests were always his faithful friends. Marchena also obtained for him the valuable sympathy of Cardinal Gonzalez de Mendoza. Through the influence of these men the Government appointed a junta or commission of ecclesiastics that met at Salamanca late in 1486 or early in 1487, in the Dominican convent of San Esteban to investigate the scheme, which they finally rejected. The commission had no connection with the celebrated University of Salamanca, but was under the guidance of the prior of Prado. It seems that Columbus gave but scant and unsatisfactory information to the commission, probably through fear that his ideas might be improperly made use of and he be robbed of the glory and advantages that he expected to derive from his project. This may account for the rejection of his proposals. The prior of Prado was a Hieronymite, while Columbus was under the especial protection of the Dominicans. Among his early friends in Spain was Luis de Santangel, whom Irving calls “receiver of the ecclesiastical revenues of Aragon”, and who afterwards advanced to the queen the funds necessary for the first voyage. If Santangel was receiver of the church revenues and probably treasurer and administrator, it was the Church that furnished the means (17,000 ducats) for the admiral’s first voyage.

It would be unjust to blame King Ferdinand for declining the proposals of Columbus after the adverse report of the Salamanca commission, which was based upon objections drawn from Seneca and Ptolemy rather than upon the opinion of St. Augustine in the “De Civitate Dei”. The king was then preparing to deal the final blow to Moorish domination in Spain after the struggle of seven centuries, and his financial resources were taxed to the utmost. Moreover, he was not easily carried away by enthusiasm and, though we now recognize the practical value of the plans of Columbus, at the close of the fifteenth century it seemed dubious, to say the least, to a cool-headed ruler, wont to attend first to immediate necessities. The crushing of the Moorish power in the peninsula was then of greater moment than the search after distant lands for which, furthermore, there were not the means in the royal treasury. Under these conditions Columbus, always in financial straits himself and supported by the liberality of friends, bethought himself of the rulers of France and England. In 1488 his brother Bartholomew, as faithful as sagacious, tried to induce one or the other of them to accept the plans of Christopher, but failed. The idea was too novel to appeal to either. Henry VII of England was too cautious to entertain proposals from a comparatively unknown seafarer of a foreign nation, and Charles VIII of France was too much involved in Italian affairs. The prospect was disheartening. Nevertheless, Columbus, with the assistance of his friends, concluded to make another attempt in Spain. He proceeded to court again in 1491, taking with him his son Diego. The court being then in camp before Granada, the last Moorish stronghold, the time could not have been more inopportune. Another junta was called before Granada while the siege was going on, but the commission again reported unfavourably. This is not surprising, as Ferdinand of Aragon could not undertake schemes that would involve a great outlay, and divert his attention from the momentous task he was engaged in. Columbus always directed his proposals to the king and as yet the queen had taken no official notice of them, as she too was heart and soul in the enterprise destined to restore Spain wholly to Christian rule.

The junta before Granada took place towards the end of 1491, and its decision was such a blow to Columbus that he left the court and wandered away with his boy. Before leaving, however, he witnessed the fall of Granada, 2 January, 1492. His intention was to return to Cordova and then, perhaps, to go to France. On foot and reduced almost to beggary, he reached the Dominican convent of La Rábida probably in January, 1492. The prior was Father Juan Perez, the confessor of the queen, frequently confounded with Fray Antonio Marchena by historians of the nineteenth century, who also erroneously place the arrival of Columbus at La Rábida in the early part of his sojourn in Spain. Columbus begged the friar who acted as door-keeper to let his tired son rest at the convent over night. While he was pleading his cause the prior was standing near by and listening. Something struck him in the appearance of this man, with a foreign accent, who appeared to be superior to his actual condition. After providing for his immediate wants Father Perez took him to his cell, where Columbus told him all his aspirations and blighted hopes. The result was that Columbus and his son stayed at the convent as guests and Father Perez hurried to Santa Fe near Granada, for the purpose of inducing the queen to take a personal interest in the proposed undertaking of the Italian navigator.

Circumstances had changed with the fall of Granada, and the Dominican’s appeal was favourably received by Isabella who, in turn, influenced her husband. Columbus was called to court at once, and 20,000 maravedis were assigned him out of the queen’s private resources that he might appear in proper condition before the monarch. Some historians assert that Luis de Santangel decided the queen to espouse the cause of Columbus, but the credit seems rather to belong to the prior of La Rábida. The way had been well prepared by the other steadfast friends of Columbus, not improbably Cardinal Mendoza among others. At all events negotiations progressed so rapidly that on 17 April the first agreement with the Crown was signed, and on 30 April the second. Both show an unwise liberality on the part of the monarchs, who made the highest office in what was afterwards the West Indies hereditary in the family of Columbus. Preparations were immediately begun for the equipment of the expedition. The squadron with which Columbus set out on his first voyage consisted of three vessels–the Santa Maria, completely decked, which carried the flag of Columbus as admiral, the Pinta, and the Niña, both caravels, i.e. undecked, with cabins and forecastles. These three ships carried altogether 120 men. Two seamen of repute, Martín Alonso Pinzon and his brother Vicente Yanez Pinzon, well-to-do-residents of Palos commanded, the former the Pinta. the latter the Niña, and experienced pilots were placed on both ships. Before leaving, Columbus received the Sacraments of Penance and Holy Eucharist, at the hands (it is stated) of Father Juan Perez, the officers and crews of the little squadron following his example. On 3 August, 1492, the people of Palos with heavy hearts saw them depart on an expedition regarded by many as foolhardy.

Las Casas claims to have used the journal of Columbus’s first voyage, but he admits that he made an abridged copy of it. What and how much he left out, of course, is not known. But it is well to bear in mind that the journal, as published, is not the original in its entirety. The vessels touched at the Canaries, and then proceeded on the voyage. Conditions were most favourable. Hardly a wind ruffled the waters of the ocean. The dramatic incident of the mutiny, in which the discouragement of the crews is said to have culminated before land was discovered, is a pure invention. That there was dissatisfaction and grumbling at the failure to reach land seems to be certain, but no acts of insubordination are mentioned either by Columbus, his commentator Las Casas, or his son Fernando. Perhaps the most important event during the voyage was the observation, 17 September, by Columbus himself, of the declination of the magnetic needle, which Las Casas attributes to a motion of the polar star. The same author intimates that two distinct journals were kept by the admiral, “because he always represented [feigned] to the people that he was making little headway in order that the voyage should not seem long to them, so that he kept a record by two routes, the shorter being the fictitious one, and the longer the true one”. He must therefore either have kept two log-books, or he must have made two different entries in the same book. At any rate Las Casas seems to have had at his command both sets of data, since he gives them almost from day to day. This precautionary measure indicates that Columbus feared insubordination and even revolt on the part of the crews, but there is no evidence that any mutiny really broke out. Finally, at ten o’clock, p.m., 11 October, Columbus himself described a light which indicated land and was so recognized by the crew of his vessel. It reappeared several times, and Columbus felt sure that the shores so eagerly expected were near. At 2 a.m. on 12 October the land was seen plainly by one of the Pinta’s crew, and in the forenoon Columbus landed on what is now called Watling’s Island in the Bahama group, West Indies. The discoverers named the island San Salvador. The Indians inhabiting it belonged to the widespread Arawak stock and are said to have called the island Guanahani. Immediately after landing Columbus took possession of the island for the Spanish sovereigns.

The results of the first voyage, aside from the discovery of what the admiral regarded as being approaches to India and China, may be summed up as follows: partial recognition of the Bahamas; the discovery and exploration of a part of Cuba, and the establishment of a Spanish settlement on the coast of what is now the Island of Haiti or Santo Domingo. Cuba Columbus named Juana, and Santo Domingo, Hispaniola.

It was on the northern coast of the large island of Santo Domingo that Columbus met with the only serious mishap of the first voyage. Having established the nucleus of the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Indies, he left about three score men to hold it. The vicinity was comparatively well peopled by natives, Arawaks like those of the Bahamas, but slightly more advanced in culture. A few days previous to the foundation Martin Alonso Pinzon disappeared with the caravel Pinta which he commanded and only rejoined the admiral on 6 January, 1493, an act, to say the least, of disobedience, if not of treachery. The first settlement was officially established on Christmas Day, 1492, and hence christened “La Navidad”. On the same day the admiral’s ship ran aground. It was a total loss, and Columbus was reduced for the time being to the Niña, as the Pinta had temporarily deserted. Happily the natives were friendly. After ensuring, as well as he might, the safety of the little colony by the establishment of friendly relations with the Indians, Columbus left for Spain, where, after weathering a frightful storm during which he was again separated from the Pinta, he arrived at Palos, 15 March, 1493.

From the journal mentioned we also gather (what is not stated in the letters of Columbus) that while on the northern shores of Santo Domingo (Hispaniola) the admiral “learned that behind the Island Juana [Cuba] towards the South, there is another large island in which there is much more gold. They call that island Yamaye. . . . And that the island Española or the other island Yamaye was near the mainland, ten days distant by canoe, which might be sixty or seventy leagues, and that there the people were clothed [dressed]”. Yamaye is Jamaica, and the mainland alluded to as sixty or seventy leagues distant to the south (by south the west is meant), or 150 to 175 English miles (the league, at that time, being counted at four millas of 3000 Spanish feet), was either Yucatan or Honduras. Hence the admiral brought the news of the existence of the American continent to Europe as early as 1493. That he believed the continent to be Eastern Asia does not diminish the importance of his information.

Columbus had been careful to load his ship with all manner of products of the newly discovered countries and he also took some of the natives. Whether, among the samples of the vegetable kingdom, tobacco was included, is not yet satisfactorily ascertained. Nor is it certain that, when upon his return he presented himself to the monarchs at Barcelona, an imposing public demonstration took place in his honour. That he was received with due distinction at court and that he displayed the proofs of his discovery can not be doubted. The best evidence of the high appreciation of the King and Queen of Spain is the fact, that the prerogatives granted to him were confirmed, and everything possible was done to enable him to continue his explorations. The fact that Columbus had found a country that appeared to be rich in precious metals was of the utmost importance. Spain was poor, having been robbed, ages before, of its metallic wealth by the Romans. As gold was needed the discovery of a new source of that precious metal made a strong impression on the people of Spain, and a rush to the new regions was inevitable.

Columbus started on his second voyage to the Indies from Cadiz, 25 September, 1493, with three large vessels and thirteen caravels, carrying in all about 1500 men. On his first trip, he had heard about other, smaller islands lying some distance south of Hispaniola, and said to be inhabited by ferocious tribes who had the advantage over the Arawaks of being intrepid seafarers, and who made constant war upon the inhabitants of the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas, carrying off women and children into captivity. They were believed to practice cannibalism. These were the Caribs and the reports about them were true, outside of some exaggerations and fables like the story of the Amazons. Previous to the arrival of Columbus the Caribs had driven the Arawaks steadily north, depopulated some of the smaller islands, and were sorely pressing the people of Hispaniola, parts of Cuba, Porto Rico, and even Jamaica. Columbus wished to learn more about these people. The helpless condition of the Arawaks made him eager to protect them against their enemies. The first land sighted, 3 November, was the island now known as Dominica, and almost at the same time that of Marie Galante was discovered. Geographically the second voyage resulted in the discovery of the Caribbean Islands (including the French Antilles), Jamaica, and minor groups. Columbus having obtained conclusive evidence of the ferocious customs of the Caribs, regarded them as dangerous to the settlements he proposed to make among the Arawaks and as obstacles to the Christianization and civilization of these Indians. The latter he intended to make use of as labourers, as he soon perceived that for some time to come European settlers would be too few in numbers and too new to the climate to take advantage of the resources of the island. The Caribs he purposed to convert eventually, but for the time being they must be considered as enemies, and according to the customs of the age, their captors had the right to reduce them to slavery. The Arawaks were to be treated in a conciliatory manner, as long as they did not show open hostility. Before long, however, there was a change in these relations.

After a rapid survey of Jamaica, Columbus hastened to the northern coast of Haiti, where he had planted the colony of La Navidad. To his surprise the little fort had disappeared. There were to be seen only smouldering ruins and some corpses which were identified as Spanish. The natives, previously so friendly, were shy, and upon being questioned were either mute or contradictory in their replies. It was finally ascertained that another tribe, living farther inland and hostile to those on the coast, had fallen upon the fort, killed most of the inmates and burnt most of the buildings. Those who escaped had perished in their flight. But it also transpired that the coast people themselves had taken part in the massacre. Columbus, while outwardly on good terms with them, was on his guard and, in consequence of the aversion of his people to a site where only disaster had befallen them, moved some distance farther east and established on the coast the larger settlement of Isabella. This stood ten leagues to the east of Cape Monte Cristo, where the ruins are still to be seen.

The existence of gold on Haiti having been amply demonstrated on the first voyage, Columbus inaugurated a diligent search for places where it might be found. The gold trinkets worn by the Indians were washings or placeres, but mention is also made, on the first voyage, of quartz rock containing the precious metal. But it is likely that the yellow mineral was iron pyrites, probably gold-bearing but, in the backward state of metallurgy, worthless at the time. Soon after the settlement was made at Isabella the colonists began to complain that the mineral wealth of the newly discovered lands had been vastly exaggerated and one, who accompanied the expedition as expert in metallurgy, claimed that the larger nuggets held by the natives had been accumulated in the course of a long period of time. This very sensible supposition was unjustly criticized by Irving, for since Irving’s time it has been clearly proved that pieces of metal of unusual size and shape were often kept for generations by the Indians as fetishes.

A more important factor which disturbed the Spanish was the unhealthiness of the climate. The settlers had to go through the slow and often fatal process of acclimatization. Columbus himself suffered considerably from ill-health. Again, the island was not well provided with food suitable for the newcomers. The population, notwithstanding the exaggerations of Las Casas and others, was sparse. Isabella with its fifteen hundred Spanish immigrants was certainly the most populous settlement. At first there was no clash with the natives, but parties sent by Columbus into the interior came in contact with hostile tribes. For the protection of the colonists Columbus built in the interior a little fort called Santo Tomas. He also sent West Indian products and some Carib prisoners back to Spain in a vessel under the command of Antonio de Torres. Columbus suggested that the Caribs be sold as slaves in order that they might be instructed in the Christian Faith. This suggestion was not adopted by the Spanish monarchs, and the prisoners were treated as kindly in Spain as the friendly Arawaks who had been sent over.

The condition of affairs on Hispaniola (Haiti) was not promising. At Isabella and on the coast there was grumbling against the admiral, in which the Benedictine Father Buil (Boil) and the other priests joined, or which, at least, they did not discourage. In the interior there was trouble with the natives. The commander at Santo Tomas, Pedro Margarite, is usually accused of cruelty to the Indians, but Columbus himself in his Memorial of 30 January, 1494, commends the conduct of that officer. However, he had to send him reinforcements, which were commanded by Alonzo de Ojeda.

Anxiously following up his theory that the newly discovered islands were but outlying posts of Eastern Asia and that further explorations would soon lead him to the coast of China or to the Moluccas, Columbus, notwithstanding the precarious condition of the colony, left it in charge of his brother Diego and four counsellors (one of whom was Father Buil), and with three vessels set sail towards Cuba. During his absence of five months he explored parts of Cuba, discovered the Isle of Pines and several groups of smaller islands, and made the circuit of Jamaica, landing there almost every day. When he returned to Isabella (29 September, 1494), he was dangerously ill and in a stupor. Meanwhile his brother Bartholomew had arrived from Spain with a small squadron and supplies. He proved a welcome auxiliary to the weak Diego, but could not prevent serious trouble. Margarite, angered by interference with his administration in the interior, returned to the coast, and there was joined by Father Buil and other malcontents. They seized the three caravels that had arrived under the command of Bartholomew Columbus, and set sail in them for Spain to lay before the Government what they considered their grievances against Columbus and his administration.

That there was cause for complaint there seems to be no doubt, but it is almost impossible now to determine who was most at fault, Columbus or his accusers. He was certainly not as able an administrator as he was a navigator. Still, taking into consideration the difficulties, the novelty of the conditions, and the class of men Columbus had to handle, and placing over against this what he had already achieved on Haiti, there is not so much ground for criticism. The charges of cruelty against the natives are based upon rather suspicious authority, Las Casas being the principal source. There were errors and misdeeds on both sides, which, however, might not have brought about a crisis had not disappointment angered the settlers, who had based their expectations on the glowing reports of Columbus himself, and disposed them to attribute all their troubles to their opponents.

TBC – Before the return of Columbus to Isabella, Ojeda had repulsed an attempt of the natives to surprise Santo Tomas. Thereupon the Indians of various tribes of the interior now formed a confederation and threatened Isabella. Columbus, however, on his return, with the aid of firearms, sixteen horses, and about twenty blood-hounds easily broke up the Indian league. Ojeda captured the leader, and the policy of kindness hitherto pursued towards the natives was replaced by repression and chastisement. According to the customs of the times the prisoners of war were regarded as rebels, reduced to slavery, and five hundred of these were sent to Spain to be sold. It is certain that the condition of the Indians became much worse thereafter, that they were forced into unaccustomed labours, and that their numbers began to diminish rapidly. That these harsh measures were authorized by Columbus there can be no doubt.

While the Spanish monarchs in their dispatches to Columbus continued to show the same confidence and friendliness they could not help hearing the accusations made against him by Father Buil, Pedro Margarite, and the other malcontents, upon their return to Spain. It was clear that there were two factions among the Spaniards in Haiti, one headed by the admiral, the other composed of perhaps a majority of the settlers including ecclesiastics. Still the monarchs enjoined the colonists by letter to obey Columbus in everything and confirmed his authority and privileges. The incriminations, however, continued, and charges were made of nepotism and spoliation if royal revenue. There was probably some foundation for these charges, though also much wilful misrepresentation. Unable to ascertain the true condition of affairs, the sovereigns finally decided to send to the Indies a special commissioner to investigate and report. Their choice fell upon Juan de Aguado who had gone with Columbus on his first voyage and with whom he had always been on friendly terms. Aguado arrived at Isabella in October, 1495, while Columbus was absent on a journey of exploration across the island. No clash appears to have occurred between Aguado and Bartholomew Columbus, who was in charge of the colony during his brother’s absence, much less with the admiral himself upon the latter’s return. Soon after, reports of important gold discoveries came from a remote quarter of the island accompanied by specimens. The arrival of Aguado convinced Columbus of the necessity for his appearance in Spain and that new discoveries of gold would strengthen his position there. So he fitted out two ships, one for himself and one for Aguado, placing in them two hundred dissatisfied colonists, a captive Indian chief (who died on the voyage), and thirty Indian prisoners, and set sail for Spain on 10 March, 1496, leaving his brother Bartholomew at Isabella as temporary governor. As intercourse between Spain and the Indies was now carried on at almost regular intervals. Bartholomew was in communication with the mother country and was at least tacitly recognized as his brother’s substitute in the government of the Indies. Columbus reached Cadiz 11 June, 1496.

The story of his landing is quite dramatic. He is reported to have gone ashore, clothed in the Franciscan garb, and to have manifested a dejection which was wholly uncalled for. His health, it is true, was greatly impaired, and his companions bore the marks of great physical suffering. The impression created by their appearance was of course not favourable and tended to confirm the reports of the opponents of Columbus about the nature of the new country. This, as well as the disappointing results of the search for precious metals, did not fail to have its influence. The monarchs saw that the first enthusiastic reports had been exaggerated, and that the enterprise while possibly lucrative in the end, would entail large expenditures for some time to come. Bishop Fonseca, who was at the head of colonial affairs, urged that great caution should be exercised. What was imputed to Bishop Fonseca as jealousy was only the sincere desire of an honest functionary to guard the interests of the Crown without blocking the way of an enthusiastic but somewhat visionary genius who had been unsuccessful as an administrator. Later expressions (1505) of Columbus indicate that the personal relations to Fonseca were at the time far from unfriendly. But the fact that Columbus had proposed the enslaving of American natives and actually sent a number of them over to Spain had alienated the sympathy of the queen to a certain degree, and thus weakened his position at court.

Nevertheless, it was not difficult for Columbus to organize a third expedition. Columbus started on his third voyage from Seville with six vessels on 30 May, 1498. He directed his course more southward than before, owing to reports of a great land lying west and south of the Antilles and his belief that it was the continent of Asia. He touched at the Island of Madeira, and later at Gomera, one of the Canary Islands, whence he sent to Haiti three vessels. Sailing southward, he went to the Cape Verde Islands and, turning thence almost due west, arrived on 31 July 1498, in sight of what is now the Island of Trinidad which was so named by him. Opposite, on the other side of a turbulent channel, lay the lowlands of north-eastern South America. Alarmed by the turmoil caused by the meeting of the waters of the Orinoco (which empties through several channels into the Atlantic opposite Trinidad) with the Guiana current, Columbus kept close to the southern shore of Trinidad as far as its south-western extremity, where he found the water still more turbulent. He therefore gave that place the name of Boca del Drago, or Dragon’s Mouth. Before venturing into the seething waters Columbus crossed over to the mainland and cast anchor. He was under the impression that this was an island, but a vast stream of fresh water gave evidence of a continent. Columbus landed, he and his crew being thus the first Europeans to set foot on South American soil. The natives were friendly and gladly exchanged pearls for European trinkets. The discovery of pearls in American waters was important and very welcome.

A few days later, the admiral, setting sail again, was borne by the currents safely to the Island of Margarita, where he found the natives fishing for pearls, of which he obtained three bags by barter.

Some of the letters of Columbus concerning his third voyage are written in a tone of despondency. Owing to his physical condition, he viewed things with a discontent far from justifiable. And, as already said, his views of the geographical situation were somewhat fanciful. The great outpour opposite Trinidad he justly attributed to the emptying of a mighty river coming from the west, a river, so large that only a continent could afford its space. In this he was right, but in his eyes that continent was Asia, and the sources of that river must be on the highest point of the globe. He was confirmed in this idea by his belief that Trinidad wasnearer the Equator than it actually is and that near the Equator the highest land on earth should be found. He thought also that the sources of the Orinoco lay in the Earthly Paradise and that the great river was one of the four streams that according to Scripture flowed from the Garden of Eden. He had no accurate knowledge of the form of the earth, and conjectured that it was pear-shaped.

On 15 August, fearing a lack of supplies, and suffering severely from what his biographers call gout and from impaired eyesight, he left his new discoveries and steered for Haiti. On 19 August he sighted that island some distance west of where the present capital of the Republic of Santo Domingo now stands. During his absence his brother Bartholomew had abandoned Isabella and established his head-quarters at Santo Domingo so called after his father Domenico. During the absence of Columbus events on Haiti had been far from satisfactory. His brother Bartholomew, who was then known as the adelantado, had to contend with several Indian outbreaks, which he subdued partly by force, partly by wise temporizing. These outbreaks were, at least in part, due to a change in the class of settlers by whom the colony was reinforced. The results of the first settlement far from justified the buoyant hopes based on the exaggerated reports of the first voyage, and the pendulum of public opinion swung back to the opposite extreme. The clamour of opposition to Columbus in the colonies and the discouraging reports greatly increased in Spain the disappointment with the new territorial acquisitions. That the climate was not healthful seemed proved by the appearance of Columbus and his companions on his return from the second voyage. Hence no one was willing to go to the newly discovered country, and convicts, suspects, and doubtful characters in general who were glad to escape the regulations of justice were the only reinforcements that could be obtained for the colony on Hispaniola. As a result there were conflicts with the aborigines, sedition in the colony, and finally open rebellion against the authority of the adelantado and his brother Diego. Columbus and his brothers were Italians, and this fact told against them among the malcontents and lower officials, but that it influenced the monarchs and the court authorities is a gratuitous charge.

As long as they had not a common leader Bartholomew had little to fear from the malcontents, who separated from the rest of the colony, and formed a settlement apart. They abused the Indians, thus causing almost uninterrupted trouble. However, they soon found a leader in the person of one Roldan, to whom the admiral had entrusted a prominent office in the colony. There must have been some cause for complaint against the government of Bartholomew and Diego, else Roldan could not have so increased the number of his followers as to make himself formidable to the brothers, undermining their authority at their own head-quarters and even among the garrison of Santo Domingo. Bartholomew was forced to compromise on unfavourable terms. So, when the admiral arrived from Spain he found the Spanish settlers on Haiti divided into two camps, the stronger of which, headed by Roldan, was hostile to his authority. That Roldan was an utterly unprincipled man, but energetic and above all, shrewd and artful, appears from the following incident. Soon after the arrival of Columbus the three caravels he had sent from Gomera with stores and ammunition struck the Haitian coast where Roldan had established himself. The latter represented to the commanders of the vessels that he was there by Columbus’s authority and easily obtained from them military stores as well as reinforcements in men. On their arrival shortly afterward at Santo Domingo the caravels were sent back to Spain by Columbus. Alarmed at the condition of affairs and his own importance, he informed the monarchs of his critical situation and asked for immediate help. Then he entered into negotiations with Roldan. The latter not only held full control in the settlement which he commanded, but had the sympathy of most of the military garrisons that Columbus and his brothers relied upon as well as the majority of the colonists. How Columbus and his brother could have made themselves so unpopular is explained in various ways. There was certainly much unjustifiable ill will against them, but there was also legitimate cause for discontent, which was adroitly exploited by Roldan and his followers.