Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

Prenatal care: 1st trimester visits

Pregnancy and prenatal care go hand in hand. During the first trimester, prenatal care includes blood tests, a physical exam, conversations about lifestyle and more.

Prenatal care is an important part of a healthy pregnancy. Whether you choose a family physician, obstetrician, midwife or group prenatal care, here's what to expect during the first few prenatal appointments.

The 1st visit

When you find out you're pregnant, make your first prenatal appointment. Set aside time for the first visit to go over your medical history and talk about any risk factors for pregnancy problems that you may have.

Medical history

Your health care provider might ask about:

- Your menstrual cycle, gynecological history and any past pregnancies

- Your personal and family medical history

- Exposure to anything that could be toxic

- Medications you take, including prescription and over-the-counter medications, vitamins or supplements

- Your lifestyle, including your use of tobacco, alcohol, caffeine and recreational drugs

- Travel to areas where malaria, tuberculosis, Zika virus, mpox — also called monkeypox — or other infectious diseases are common

Share information about sensitive issues, such as domestic abuse or past drug use, too. This will help your health care provider take the best care of you — and your baby.

Your due date is not a prediction of when you will have your baby. It's simply the date that you will be 40 weeks pregnant. Few people give birth on their due dates. Still, establishing your due date — or estimated date of delivery — is important. It allows your health care provider to monitor your baby's growth and the progress of your pregnancy. Your due date also helps with scheduling tests and procedures, so they are done at the right time.

To estimate your due date, your health care provider will use the date your last period started, add seven days and count back three months. The due date will be about 40 weeks from the first day of your last period. Your health care provider can use a fetal ultrasound to help confirm the date. Typically, if the due date calculated with your last period and the due date calculated with an early ultrasound differ by more than seven days, the ultrasound is used to set the due date.

Physical exam

To find out how much weight you need to gain for a healthy pregnancy, your health care provider will measure your weight and height and calculate your body mass index.

Your health care provider might do a physical exam, including a breast exam and a pelvic exam. You might need a Pap test, depending on how long it's been since your last Pap test. Depending on your situation, you may need exams of your heart, lungs and thyroid.

At your first prenatal visit, blood tests might be done to:

- Check your blood type. This includes your Rh status. Rh factor is an inherited trait that refers to a protein found on the surface of red blood cells. Your pregnancy might need special care if you're Rh negative and your baby's father is Rh positive.

- Measure your hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein found in red blood cells that allows the cells to carry oxygen from your lungs to other parts of your body. Hemoglobin also carries carbon dioxide from other parts of your body to your lungs so that it can be exhaled. Low hemoglobin or a low level of red blood cells is a sign of anemia. Anemia can make you feel very tired, and it may affect your pregnancy.

- Check immunity to certain infections. This typically includes rubella and chickenpox (varicella) — unless proof of vaccination or natural immunity is documented in your medical history.

- Detect exposure to other infections. Your health care provider will suggest blood tests to detect infections such as hepatitis B, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia and HIV , the virus that causes AIDS . A urine sample might also be tested for signs of a bladder or urinary tract infection.

Tests for fetal concerns

Prenatal tests can provide valuable information about your baby's health. Your health care provider will typically offer a variety of prenatal genetic screening tests. They may include ultrasound or blood tests to check for certain fetal genetic problems, such as Down syndrome.

Lifestyle issues

Your health care provider might discuss the importance of nutrition and prenatal vitamins. Ask about exercise, sex, dental care, vaccinations and travel during pregnancy, as well as other lifestyle issues. You might also talk about your work environment and the use of medications during pregnancy. If you smoke, ask your health care provider for suggestions to help you quit.

Discomforts of pregnancy

You might notice changes in your body early in your pregnancy. Your breasts might be tender and swollen. Nausea with or without vomiting (morning sickness) is also common. Talk to your health care provider if your morning sickness is severe.

Other 1st trimester visits

Your next prenatal visits — often scheduled about every four weeks during the first trimester — might be shorter than the first. Near the end of the first trimester — by about 12 to 14 weeks of pregnancy — you might be able to hear your baby's heartbeat with a small device, called a Doppler, that bounces sound waves off your baby's heart. Your health care provider may offer a first trimester ultrasound, too.

Your prenatal appointments are an ideal time to discuss questions you have. During your first visit, find out how to reach your health care team between appointments in case concerns come up. Knowing help is available can offer peace of mind.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Lockwood CJ, et al. Prenatal care: Initial assessment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Prenatal care and tests. Office on Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/pregnancy/youre-pregnant-now-what/prenatal-care-and-tests. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Cunningham FG, et al., eds. Prenatal care. In: Williams Obstetrics. 25th ed. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018. https://www.accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Lockwood CJ, et al. Prenatal care: Second and third trimesters. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/anc-positive-pregnancy-experience/en/. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Bastian LA, et al. Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of pregnancy. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 9, 2018.

Products and Services

- A Book: Obstetricks

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 1st trimester pregnancy

- Can birth control pills cause birth defects?

- Fetal development: The 1st trimester

- Implantation bleeding

- Nausea during pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Prenatal care 1st trimester visits

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Your First Prenatal Appointment

Medical review policy, latest update:.

Medically reviewed for accuracy.

When should I schedule my first prenatal visit?

When will my first prenatal visit take place, read this next, how should i prepare for my first pregnancy appointment, what will happen at my first prenatal visit, will i see my baby on an ultrasound at my first prenatal visit, updates history, jump to your week of pregnancy, trending on what to expect, signs of labor, pregnancy calculator, ⚠️ you can't see this cool content because you have ad block enabled., top 1,000 baby girl names in the u.s., top 1,000 baby boy names in the u.s., braxton hicks contractions and false labor.

- Pregnancy Classes

Your First Prenatal Visit

If you did not meet with your health care provider before you were pregnant, your first prenatal visit will generally be around 8 weeks after your LMP (last menstrual period ). If this applies to you, you should schedule a prenatal visit as soon as you know you are pregnant!

Even if you are not a first-time mother, prenatal visits are still important since every pregnancy is different. This initial visit will probably be one of the longest. It will be helpful if you arrive prepared with vital dates and information. This is also a good opportunity to bring a list of questions that you and your partner have about your pregnancy, prenatal care, and birth options.

What to Expect at Your First Pregnancy Appointment

Your doctor will ask for your medical history, including:.

- Medical and/or psychosocial problems

- Blood pressure, height, and weight

- Breast and cervical exam

- Date of your last menstrual period (an accurate LMP is helpful when determining gestational age and due date)

- Birth control methods

- History of abortions and/or miscarriages

- Hospitalizations

- Medications you are taking

- Medication allergies

- Your family’s medical history

Your healthcare provider will also perform a physical exam which will include a pap smear , cervical cultures, and possibly an ultrasound if there is a question about how far along you are or if you are experiencing any bleeding or cramping .

Blood will be drawn and several laboratory tests will also be done, including:

- Hemoglobin/ hematocrit

- Rh Factor and blood type (if Rh negative, rescreen at 26-28 weeks)

- Rubella screen

- Varicella or history of chickenpox, rubella, and hepatitis vaccine

- Cystic Fibrosis screen

- Hepatitis B surface antigen

- Tay Sach’s screen

- Sickle Cell prep screen

- Hemoglobin levels

- Hematocrit levels

- Specific tests depending on the patient, such as testing for tuberculosis and Hepatitis C

Your healthcare provider will probably want to discuss:

- Recommendations concerning dental care , cats, raw meat, fish, and gardening

- Fevers and medications

- Environmental hazards

- Travel limitations

- Miscarriage precautions

- Prenatal vitamins , supplements, herbs

- Diet , exercise , nutrition , weight gain

- Physician/ midwife rotation in the office

Possible questions to ask your provider during your prenatal appointment:

- Is there a nurse line that I can call if I have questions?

- If I experience bleeding or cramping, do I call you or your nurse?

- What do you consider an emergency?

- Will I need to change my habits regarding sex, exercise, nutrition?

- When will my next prenatal visit be scheduled?

- What type of testing do you recommend and when are they to be done? (In case you want to do research the tests to decide if you want them or not.)

If you have not yet discussed labor and delivery issues with your doctor, this is a good time. This helps reduce the chance of surprises when labor arrives. Some questions to ask include:

- What are your thoughts about natural childbirth ?

- What situations would warrant a Cesarean ?

- What situations would warrant an episiotomy ?

- How long past my expected due date will I be allowed to go before intervening?

- What is your policy on labor induction?

Want to Learn More?

- Sign up for our weekly email newsletter

- Bonding With Your Baby: Making the Most of the First Six Weeks

- 7 Common Discomforts of Pregnancy

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Breastfeeding 29

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Cord Blood 4

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 54

- Labor and Birth 65

- Multiple Births 10

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- The First Year 41

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Paternity Tests 2

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Prenatal Testing 16

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Uncategorized 4

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Women's Health 34

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

Share this post:

Similar post.

Leg Cramps During Pregnancy

Prenatal Vitamin Limits

Skin Changes During Pregnancy

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

Speak to a maternal child health nurse

Call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436 or video call . Available 7am to midnight (AET), 7 days a week.

Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content .

Last reviewed: December 2022

Related pages

- What does a child health nurse do?

- What does an obstetrician do?

- What do midwives do?

Health professionals involved in your pregnancy

- What do paediatricians do?

Search our site for

- General Practitioners

Need more information?

Top results

Pregnancy health problems & complications | Raising Children Network

Many pregnancy health problems are mild, but always call your doctor if you’re worried about symptoms. A healthy lifestyle can help you avoid health problems.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Records and paperwork for maternal health care and babies - Better Health Channel

When you are having a baby in Victoria, there are various records and other documents that need to be accessed, created or completed.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Pregnancy and birth care options - Better Health Channel

Pregnant women in Victoria can choose who will care for them during their pregnancy, where they would like to give birth and how they would like to deliver their baby.

Pregnancy: blood tests, ultrasound & more | Raising Children Network

In pregnancy, you’ll be offered blood tests, ultrasound scans, urine tests and the GBS test. Pregnancy tests identify health concerns for you and your baby.

Information on the health professionals involved in your pregnancy, such as midwives, doctors and obstetricians.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

How to quit when you're pregnant or breastfeeding

Tips on quitting when your pregnant, from first trimester to post delivery.

Read more on Quit website

Obstetrician-gynaecologist - Better Health Channel

An obstetrician-gynaecologist is a specialist doctor who cares for women and specialises in pregnancy, childbirth and reproductive health.

FASD diagnosis and assessment | FASD Hub

Find out about FASD diagnosis and assessment for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in Australia

Read more on FASD Hub Australia website

GPs, shared care & pregnancy | Raising Children Network

Shared care is when you have some pregnancy appointments with your GP and some at hospital. Shared care can be good if you feel comfortable with your GP.

Antenatal tests: chromosomal anomalies | Raising Children Network

Antenatal tests can tell you if your baby has chromosomal anomalies or other conditions. Your health professional can help you make choices about these tests.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Call us and speak to a Maternal Child Health Nurse for personal advice and guidance.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Government Accredited with over 140 information partners

We are a government-funded service, providing quality, approved health information and advice

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

© 2024 Healthdirect Australia Limited

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Recommended links

Warning notification: Warning

Unfortunately, you are using an outdated browser. Please, upgrade your browser to improve your experience with HSE. The list of supported browsers:

Antenatal and maternity care appointments

You will have a number of appointments during your pregnancy.

Appointments will be with your GP, hospital, or a midwife.

You’ll have more appointments if you’re:

- diagnosed with a pregnancy-related condition like high blood pressure or gestational diabetes

- pregnant with twins or multiple babies

Additional appointments for pregnancy-related conditions are covered by the Maternity and Infant Care Scheme .

The scheme does not cover appointments for illnesses that are not related to your pregnancy. For example, a urinary tract infection or chest infection .

Your appointments may be changed by your GP, maternity unit, or hospital depending on your situation.

Appointments with your GP

If you register for the Maternity and Infant Care Scheme , your first appointment is with your GP. You'll see your GP at least 5 times during your pregnancy.

Your GP will do antenatal checks and give you information on how to have a healthy pregnancy. They might discuss folic acid , exercise , healthy eating and vaccines with you.

Your GP will offer you a free flu vaccine during one of your appointments. The flu season begins in October and finishes at the end of April.

Your GP will also offer you a vaccination to protect your baby from whooping cough (pertussis) between 16 to 36 weeks.

Read more about vaccines needed during pregnancy

If you do not have a GP, contact your local maternity unit for an appointment.

Appointments at your maternity unit or hospital

You will have appointments at your maternity unit or hospital under the Maternity and Infant Care Scheme. The number of appointments depends on your needs.

Your blood pressure and urine will usually be checked during these appointments.

The booking visit (between 8 to 12 weeks)

Your first appointment at the maternity unit or hospital is called the 'booking visit' and is with a midwife. This usually takes place between 8 to 12 weeks of your pregnancy.

You will be asked about your medical and family history and any previous pregnancies.

A sample of your blood will be taken. The blood test results will be reviewed at your next appointment. You will also be offered a dating scan .

You may get information about antenatal classes and breastfeeding .

You may be referred for other appointments if needed.

These may be with:

- physiotherapists

- smoking or alcohol cessation specialists

- social workers if needed

Between 20 to 22 weeks

You will be offered a fetal anatomy scan (anomaly scan) at the hospital.

If an anomaly is detected, you will be referred to an obstetrician who specialises in fetal anomalies.

From 28 weeks on

Your hospital appointments from 28 weeks onward will continue to check:

- your baby's growth and development and position in the womb

- if you have signs of high blood pressure or other complications

The height of your womb (uterus) might be measured and your baby’s heart rate will be checked. You may also be asked about your baby's movements .

It may not be necessary to have another scan after your anomaly scan at 20 weeks.

Your midwife or obstetrician will also talk to you about:

- preparing for the birth

- any concerns you may have

- breastfeeding

- preparing for parenthood

During the birth

During birth, you’ll be cared for by a midwife. If the midwife identifies a problem during your labour, they will ask a doctor to help if needed.

If you need an epidural , this will be done by an anaesthetist (a doctor who specialises in pain relief medicine).

After the birth

You will be supported by midwives after the birth. They will help you with breastfeeding and caring for your baby.

Most women and babies are discharged from hospital within 3 days of the birth. If you choose a 'domino scheme', you may be able to go home earlier. This means a midwife will be visiting you at home.

Some hospitals also have ‘early transfer home’ schemes which means you can leave the hospital as soon as possible after the birth (usually 12 to 36 hours).

When you return home, a public health nurse (PHN) will visit you within 72 hours of leaving hospital.

Your GP or your GP practice nurse will examine your baby at 2 weeks old. Your GP will examine both you and your baby when your baby is 6 weeks old.

Related topics

Your child's health checks

Your postnatal check at 6 weeks

Page last reviewed: 14 June 2023 Next review due: 14 June 2026

This project has received funding from the Government of Ireland’s Sláintecare Integration Fund 2019 under Grant Agreement Number 123.

National guide to a preventive health assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

- Overweight and obesity

- Physical activity

- Chapter 2: Antenatal care

- Immunisation

- Growth failure

- Childhood kidney disease

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

- Preventing child maltreatment – Supporting families to optimise child safety and wellbeing

- Social emotional wellbeing

- Unplanned pregnancy

- Illicit drug use

- Osteoporosis

- Visual acuity

- Trachoma and trichiasis

- Chapter 7: Hearing loss

- Chapter 8: Oral and dental health

- Pneumococcal disease prevention

- Influenza prevention

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Bronchiectasis and chronic suppurative lung disease

- Chapter 10: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease

- Chapter 11: Cardiovascular disease prevention

- Chapter 12: Type 2 diabetes prevention and early detection

- Chapter 13: Chronic kidney disease prevention and management

- Chapter 14: Sexual health and blood-borne viruses

- Prevention and early detection of cervical cancer

- Prevention and early detection of primary liver (hepatocellular) cancer

- Prevention and early detection of breast cancer

- Prevention and early detection of colorectal (bowel) cancer

- Early detection of prostate cancer

- Prevention of lung cancer

- Chapter 16: Family abuse and violence

- Prevention of depression

- Prevention of suicide

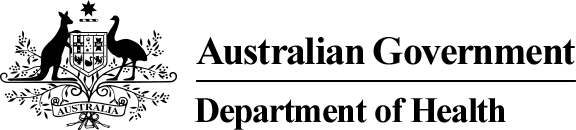

Antenatal care aims to improve health and prevent disease for both the pregnant woman and her baby. While many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have healthy babies, poor maternal health and social disadvantage contribute to higher risks of having problems during pregnancy and an adverse pregnancy outcome. 1,2 The reasons for these adverse outcomes are complex and multifactorial (Figure 1), and together with other measures of health disparity provide an imperative for all involved in caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to ensure they receive the highest quality antenatal care, and, in particular, care that is woman-centred, evidence-based and culturally competent. This chapter reflects recommendations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women from two modules of Australian evidence-based antenatal care guidelines 3,4 and incorporates new evidence published subsequently. For selected antenatal care topics, narrative summaries of evidence relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait women are presented below. These are:

- screening for genitourinary and blood-borne viral infections

- nutrition and nutritional supplementation

Antenatal care – General features

Antenatal care includes providing support, information and advice to women during pregnancy, undertaking regular clinical assessments, and screening for a range of infections and other conditions as well as following up and managing screen-detected problems. 4 The key feature of high-quality antenatal care for all women is that it is woman-centred, 4 meaning care that includes:

- focusing on each woman’s individual needs, expectations and aspirations, including her physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, social and cultural needs

- being culturally safe

- supporting women to make informed choices and decisions involving the woman’s partner, family and community, as identified by the woman herself.

High-quality antenatal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women includes holistic care that is consistent with the Aboriginal definition of health, being the physical, social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of both an individual and their community. 6

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are cared for by a range of health professionals during pregnancy, and the cultural competence of healthcare providers is of critical importance to women’s engagement with antenatal care and the delivery of high-quality care. Healthcare providers need an awareness of the higher levels of social and economic disadvantage experienced by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and to prioritise doing what they can to address these social determinants of health at both individual and system levels. 7 Building trust, and respectful communication and developing effective therapeutic relationships are also key features of providing high-quality antenatal care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. 8 In Australia, antenatal care is delivered in a range of organisational settings including hospitals, general and specialist private practices, government clinics, and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. The involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the delivery of care, and in the design and management of services, will improve the quality of care for Aboriginal and Torres Islander women in all settings. 4 The ‘first visit’ is an important focus in antenatal care, as provision of advice and a range of assessment and screening activities is best undertaken early in pregnancy to maximise the benefits. It is recommended that the first antenatal care visit occurs before 10 weeks’ gestation. 4 While there is some evidence of recent improvements, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are still less likely than other Australian women to receive antenatal care early in pregnancy. 1,9 According to age-standardised national data from 2014, 53% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women attended antenatal care in the first trimester, compared to 60% of non-Indigenous women, and among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women first trimester attendance was higher for women in outer regional areas (62%) compared to women living in major cities (48%) or very remote areas (51%). 1 This suggests the need for ongoing attention by the healthcare system to promoting and facilitating early engagement of pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, including strengthening cultural safety and addressing local barriers identified by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Current recommendations for antenatal care have shifted from a ‘traditional’ fixed schedule of visits towards a more flexible tailored plan of visits that is developed in consultation with each woman in early pregnancy and designed to meet her individual needs. 4 Ten antenatal care visits are recommended for a woman without complications having her first pregnancy, and seven visits for a woman having a subsequent pregnancy. 4 Antenatal care frequently involves screening that aims to improve outcomes for the pregnant woman and her baby. For all screening conducted during pregnancy, women must be provided with information and an opportunity to ask questions about the tests and potential treatments beforehand, so that they are able to provide informed consent. Screening test results need to be communicated to women whether they are positive or negative, and appropriate management and follow-up of positive results is critical if the potential benefits of screening are to be realised.

Smoking tobacco during pregnancy has a range of negative impacts on the health of women and babies. Adverse birth outcomes are more common among women who smoke during pregnancy and include an increased risk of preterm birth, low birthweight, and stillbirth. Children of women who smoked during pregnancy have higher rates of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), asthma, ear infections and respiratory infections. Quitting smoking before or during pregnancy can reduce these risks. At a national level, an estimated 44% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women smoked during pregnancy in 2014. 1 The prevalence of smoking during pregnancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women is decreasing (down from 52% in 2003 10 ); however, it remains much higher than that of non-Indigenous women who are pregnant (12% in 2014). Smoking during pregnancy is more common among young women, those living in rural and remote areas, and those who experience socioeconomic disadvantage. 1 Factors associated with high smoking rates and low quit rates among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations include the normalisation of smoking within Aboriginal communities; the presence of social health determinants such as unemployment, poverty, removal from family, and incarceration; personal stressors such as violence, grief and loss; concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis; and lack of access to culturally appropriate support for quitting. 11–14 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have expressed the view that smoking during pregnancy can help them cope with stress and relieve boredom, and that quitting may be of lower priority compared to the many other personal and community problems they face. 15 Pregnancy is a particularly opportune time for an intensive focus on the delivery of smoking cessation advice and support to women, because of the potential for improving the health of both mother and baby, and because women are more likely to quit smoking during pregnancy. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have indicated their support for receiving information, advice and support for quitting from caregivers during pregnancy. 16,17 Health professionals, therefore, have an important role to play in providing information and support to women during pregnancy. There is systematic review evidence that psychosocial interventions for smoking cessation during pregnancy are effective at increasing quit rates and improving birth outcomes such as low birthweight. 18 Only one randomised controlled trial has assessed the effectiveness of a tailored smoking cessation intervention for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. 19 It did not find a significant difference in quit rates between the intervention group and those receiving usual care, suggesting that more work is needed to optimise smoking cessation strategies in pregnancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. All pregnant women should be asked about their smoking history and practices, and it is recommended that those who currently smoke or have recently quit be provided with information about the effects of smoking during pregnancy, advised to quit smoking and stay quit, and offered ongoing and tailored support to do so. 4 Efforts by health professionals to address smoking during pregnancy for Aboriginal women are more likely to be effective when relationships are non-judgemental, trusting and respectful, as well as empowering and supportive of women’s self-efficacy and agency. 12,20 The social context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s lives is very important to consider when designing and delivering smoking cessation advice and support during pregnancy; it has been suggested that addressing stressors, and building skills and coping strategies, are likely to increase the efficacy of smoking cessation efforts. 14,15 Involvement of partners and families, as well as community-wide efforts to denormalise and reduce smoking in Aboriginal communities, are also recommended as strategies to address smoking in pregnancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. While evidence for the effectiveness of nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) during pregnancy is currently limited, trial results suggest NRT can have positive impacts on quit rates and child development outcomes, and there is no evidence of associated harms. 21 The use of NRT during pregnancy is recommended when initial quit attempts have not been successful, with preference being for the use of an intermittent mode of delivery (such as lozenges, gum or spray) rather than continuous (such as patches). 4 The safety of oral pharmacotherapies (such as buprenorphine and varenicline) and e-cigarettes, and their effectiveness as measures to support quitting during pregnancy, is not known and therefore they are not recommended for use. 21

Screening for genitourinary and blood-borne infections

Urinary tract infections.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common during pregnancy, and may be more common among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. 22–24 Ascending urinary tract infection during pregnancy may lead to pyelonephritis, and an association with preterm birth and low birth weight has been suggested. 4 A Cochrane review has demonstrated that treatment with antibiotics is effective at clearing asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy, and results in a reduced risk of pyelonephritis as well as providing suggestive evidence about a reduced risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth and low birthweight. 25 All women should be routinely offered testing for asymptomatic bacteriuria early in pregnancy using a midstream urine culture. 4 Urine dipstick for nitrites is not a suitable test for diagnosing infection, as false positives are frequent; however, a negative dipstick result means infection is unlikely. Appropriate storage of dipsticks is essential, as high humidity and temperature can impact on their accuracy.

Chlamydia is a common sexually transmitted infection (STI) that can be asymptomatic and can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Chlamydia infection during pregnancy has been associated with higher rates of preterm birth and growth restriction, and can result in neonatal conjunctivitis and respiratory tract infections. 4 Antibiotics are effective at treating chlamydia, and there is some evidence that treatment during pregnancy reduces the incidence of preterm birth and low birth weight. 26,27 Chlamydia prevalence estimates for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women vary from 2.9% to 14.4%. 30,31 Chlamydia is most common among young people, with 80% of diagnoses among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people being in this group. 30 Notification rates for chlamydia are eight times higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in remote regions. 30 Australian national evidence-based antenatal care guidelines recommend that chlamydia testing is routinely offered during pregnancy at the first antenatal care visit to pregnant women aged less than 25 years, and to all women who live in areas where chlamydia and other STIs have a high prevalence. 4 Pregnant women who test positive to chlamydia, and their partners, need follow-up, assessment for other STIs and treatment.

Gonorrhoea is a sexually acquired infection that can cause pelvic inflammatory disease and chronic pelvic pain in women. Gonorrhoea infection during pregnancy is associated with adverse outcomes including ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, preterm birth and maternal sepsis during and after pregnancy. 4 Transmission at the time of birth can lead to neonatal conjunctivitis, which may cause blindness. Gonorrhoea is most commonly diagnosed in young people, and is more common for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in outer regional and remote areas. 30 Rates of diagnosis have been declining but remain high in these regions. 30 Australian national evidence-based antenatal care guidelines recommend against screening all pregnant women for gonorrhoea, because there is a relatively low prevalence of disease and there is potential for harms associated with false positive test results, particularly in low-risk populations. 4 Screening for gonorrhoea is recommended for pregnant women who live in, or come from, areas of high prevalence (outer regional and remote areas), or who have risk factors for STIs. Pregnant women who test positive to gonorrhoea, and their partners, need follow-up, assessment for other STIs and treatment.

Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted vaginitis that is commonly asymptomatic, but can cause a yellow–green vaginal discharge and vulval irritation, and may be associated with infertility and pelvic inflammatory disease. 3 The implications of trichomoniasis during pregnancy remain unclear; while an association between trichomoniasis and preterm birth and low birth weight has been demonstrated, evidence of a cause and effect relationship is currently lacking. 31 The benefits of screening asymptomatic women for trichomonas during pregnancy are uncertain, because there is no evidence that antibiotic treatment improves pregnancy outcomes, 3,31 with one trial suggesting a higher rate of preterm birth among pregnant women who were treated for asymptomatic trichomoniasis with metronidazole. 31 For this reason screening of asymptomatic, pregnant women is not recommended. 3

Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a deficiency of normal vaginal flora (Lactobacilli) and a relative overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria. BV occurs commonly and is often asymptomatic, although it can also cause a greyish vaginal discharge. 4 In epidemiological studies, BV has been associated with a higher rate of preterm birth. While antibiotics for BV have been found to be effective at eradicating BV microbiologically, they have not resulted in a reduction in the preterm birth rate. 32 For this reason, routine screening of asymptomatic pregnant women for BV is not recommended. 4,32 Symptomatic women diagnosed with BV, however, should be treated.

Group B streptococcus

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is a bacteria that commonly colonises the gastrointestinal tract, vagina and urethra, and has the potential to increase the risk of preterm birth and cause serious neonatal infection after birth. 4 For women who are colonised with GBS, intravenous antibiotics during labour can prevent more than 80% of neonatal infection. 4 Australian estimates suggest a prevalence of GBS colonisation among all pregnant women of around 20%. 4 Prevention strategies can involve two main approaches: antenatal screening for GBS in late pregnancy (at 35–37 weeks’ gestation), or an assessment of risk factors for GBS transmission during labour (including preterm birth, maternal fever and prolonged rupture of membranes). As there is currently no clear evidence supporting one strategy over the other, Australian national evidence-based antenatal care guidelines recommend either strategy can be used. 4

Syphilis is an STI with serious systemic sequelae. During pregnancy, syphilis can cause spontaneous miscarriage or stillbirth, or lead to congenital infection that is commonly fatal or results in severe and permanent impairment. Congenital syphilis can be prevented by effective treatment of maternal syphilis with antibiotics. 33 In Australia, notifications of infectious syphilis have been declining but have remained more common for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared to non-Indigenous populations. 30 However, since 2010 there has been a marked increase in notifications of infectious syphilis, driven by an outbreak in northern Australia, including Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland. 34 This outbreak has included a total of 22 cases of congenital syphilis being notified nationally between 2011 and 2015, with 14 of these cases being Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies, 30 and several infant deaths from syphilis have occurred. 34 All pregnant women should be routinely offered testing to screen for syphilis at the first antenatal visit, and repeat screening later in pregnancy may be appropriate in regions of high prevalence. 4 The interpretation of syphilis serology can be complex. To ensure diagnosis, treatment and follow-up are consistent with evidencebased best practice, it is recommended that expert advice is sought if a pregnant woman tests positive for syphilis on an initial screen. 4

While human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is uncommon in Australia, screening during pregnancy for all women at the first antenatal visit is recommended because of the serious consequences of mother-tochild transmission and the availability of treatments effective at reducing this risk. 4 These treatments include caesarean section, short courses of selected antiretroviral medications, and the avoidance of breastfeeding. HIV infection currently occurs at similar rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous population groups in Australia. 30 Women who test positive for HIV require careful and confidential follow-up, including repeat confirmatory testing, assessment and specialist management.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is a blood-borne virus with the potential for causing serious long-term sequelae, including cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure through chronic infection. Hepatitis C infection is diagnosed up to four times more often among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women than nonIndigenous women, and is increasing. 30 Perinatal transmission occurs for 4–6% of babies born to women who are positive to both hepatitis C antibody and hepatitis C RNA during pregnancy, and this risk is higher with increasing viral load. 4 In recent years, the increased availability of effective anti-viral therapies with fewer adverse impacts than previously available treatments has greatly improved treatment options and outcomes for people with chronic hepatitis C infection. 35 However, at the time of writing, anti-viral therapies used for treating for hepatitis C are not approved or recommended for use during pregnancy. 35 The lack of antenatal treatment options and the potential psychological harms associated with false positive results of screening tests are the main reasons that routine screening of all women for hepatitis C during pregnancy is not recommended. 4 Testing during pregnancy may be considered, however, for women with identifiable risk factors, including intravenous drug use, tattooing and body piercing, and incarceration. 4 If an initial hepatitis C antibody test is positive, a confirmatory hepatitis C RNA test is required to assess risks and guide management for the woman and baby, and both should be appropriately followed up.

Hepatitis B

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations have higher rates of diagnosis of hepatitis B infection than non-Indigenous population groups, and available evidence suggests this pattern is also true of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity during pregnancy. 30,36,37 All pregnant women should be offered screening for hepatitis B infection by testing for hepatitis B surface antigen at their first antenatal care visit, and those that test positive should be appropriately followed up. 4 Newborn children of women with current hepatitis B infection (hepatitis B surface antigen positive) can be vaccinated after delivery. Vaccination and the provision of immunoglobulin to the baby at birth is approximately 95% effective at preventing perinatal transmission. 4

Nutrition and nutritional supplementation

Good nutrition during pregnancy is important for the health of the woman, and the development and growth of the baby. Providing women with information and advice about nutritional needs during pregnancy is an important part of routine antenatal care. In providing this advice to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, it is important to consider the significance of barriers to accessing nutritious foods (eg fresh fruit, vegetables) because of costs and lack of availability in rural and remote regions (refer to Chapter 1: Lifestyle, ‘Overweight and obesity’ ).

Weight and body mass index

Overweight and obesity is becoming increasingly common in Australia, and is more common in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population groups. 9 In 2014, obesity during pregnancy was documented for 33% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women compared to 20% of non-Indigenous women. 1 Being overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m 2 ) or underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m 2 ) before pregnancy are each associated with an increased risk of adverse birth outcomes. Being overweight before pregnancy or having a high weight gain during pregnancy is associated with higher rates of preterm birth, caesarean section, gestational high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, postpartum haemorrhage, and depression, as well as a baby being more likely to be of low birthweight or large for gestational age. Being underweight before pregnancy or having a low weight gain during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, low birthweight and being small for gestational age. The national evidence-based antenatal care guidelines recommend routine assessment of a woman’s weight and height, and calculation of BMI at the first antenatal care visit. 4 Weighing women at subsequent visits is recommended only when it is likely to influence clinical management. Recommended weight gain during pregnancy varies with a woman’s estimated pre-pregnancy BMI from a total of 6 kg to 18 kg ( Box 1 ). While weight loss is not an appropriate aim during pregnancy, strong evidence suggests interventions for women who are overweight based on increased physical activity and dietary counselling combined with weight monitoring can reduce inappropriate weight gain during pregnancy, as well as reduce the risks of caesarean section, macrosomia and neonatal respiratory morbidity. 38–40

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations are at greater risk of anaemia, 41 and iron deficiency is the most common cause of anaemia. Routine iron supplementation for all pregnant women is not recommended, because evidence of improved pregnancy outcomes is lacking and there may be adverse impacts. 4 However, it is recommended that all women be screened for anaemia at the first and subsequent visits during pregnancy, and that iron supplementation be used to treat iron deficiency if it is detected. 4 Management of iron deficiency anaemia during pregnancy includes dietary advice, iron supplementation and follow-up. Pregnant women can potentially benefit by being advised about iron-rich foods and that iron absorption can be aided by vitamin C– rich foods, such as fresh fruit and fruit juice, and reduced by tea and coffee. 4,42

Routine folic acid supplementation before and during pregnancy is recommended for all women as it is effective in reducing the risk of neural tube defects. 4 The incidence of this group of congenital abnormalities decreased in Australia among non-Indigenous women after folic acid supplementation during pregnancy became widespread. 43 However, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women were still experiencing high rates of neural tube defects. 43,44 Following mandatory folic acid fortification of bread, which has occurred since 2009, rates of neural tube defects among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have dropped significantly and are now lower than those of other Australian women. 45

Increased thyroid activity during pregnancy results in increased maternal requirements for iodine, which is essential for neuropsychological development. While severe iodine deficiency during pregnancy is uncommon in Australia, recent evidence suggests that mild and moderate levels of iodine deficiency during pregnancy may result in negative impacts on the neurological and cognitive development of the child. 47 While mandatory iodine fortification of bread since 2009 has improved iodine levels in the general Australian population, available evidence suggests that for many women dietary intake of iodine will not be sufficient to meet needs during pregnancy and breastfeeding. 45 As a consequence, it is recommended that all pregnant women take an iodine supplement of 150 mcg daily. 4,47

Vitamin D is essential for skeletal development, and vitamin D deficiency may have a range of negative health impacts, including during pregnancy. 4,48 The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency varies geographically and between different population groups, and there have been few estimates of prevalence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. 49,50 Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency include limited exposure to sunlight, dark skin and a high BMI. Vitamin D supplementation for women with vitamin D deficiency increases maternal levels of vitamin D, but there is currently no evidence that it improves pregnancy outcomes. 4,48 Screening pregnant women for vitamin D deficiency is recommended only if they have risk factors, and women who are found to be vitamin D deficient should be treated with supplementation because of the potential benefits to their long-term health. 4,48

Diabetes in pregnancy includes type 1 or type 2 diabetes diagnosed before pregnancy, undiagnosed pre-existing diabetes, and gestational diabetes, where glucose intolerance develops in the second half of pregnancy. All forms of diabetes in pregnancy are associated with increased risks for both the pregnant woman and the baby, with the level of risk depending on the level of hyperglycaemia. 3,51–53 Diabetes in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of induced labour, preterm birth, caesarean section and pre-eclampsia. Babies of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy have higher rates of stillbirth, fetal macrosomia, low APGAR (Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration) scores, neonatal hypoglycaemia, and admission to special care/neonatal intensive care units. Babies born to mothers with pre-existing diabetes also have a higher risk of congenital malformations of the spine, heart and kidneys. In addition, raised maternal glycaemic levels are associated with a child having increased adiposity in childhood and other adverse metabolic factors that may increase the risks of later cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Women with gestational diabetes also have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life. The number of women with all types of diabetes in pregnancy is increasing. At a national level in 2014, an estimated 4% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women had diabetes in pregnancy and 13% had gestational diabetes, and each of these rates was higher than those of non-Indigenous women (3.5 times higher for diabetes and 1.6 times higher for gestational diabetes). 1 Given the high prevalence of diabetes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, a significant number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are likely to have undiagnosed diabetes at the time they become pregnant. Consequently, screening all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women for pre-existing diabetes is recommended at the first antenatal care visit. 3,54 Tests recommended for screening for undiagnosed diabetes are fasting plasma glucose, plasma glucose after a 75 g glucose load, or random plasma glucose. 3 The use of HbA1C levels to screen for diabetes during pregnancy has not yet been fully evaluated, but has been proposed as an alternative test to consider for early pregnancy screening if other tests such as an oral glucose tolerance test are not feasible; an HbA1C level above 6.5% suggests pre-existing diabetes. 54 Internationally, screening guidelines for gestational diabetes vary in their recommendations about whether screening should be offered to all pregnant women or only to women with risk factors for diabetes. However, given the higher risk of diabetes experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, it is recommended that all pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women without pre-existing diabetes are offered screening for gestational diabetes. The recommended timing for gestational diabetes screening to occur is 24–28 weeks’ gestation, and recommended tests include fasting plasma glucose, or plasma glucose one hour and two hours after a 75 g glucose load. 3,54 While diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes continue to be debated, Australian national evidence-based antenatal care guidelines 3 and the Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society 54 both recommend the use of criteria endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (refer to ‘Recommendations: Diabetes’). In discussions about screening for diabetes and gestational diabetes, women need information about the risks associated with these conditions and the effectiveness of management in reducing and mitigating these risks. 56,57 In general terms, management strategies for diabetes in pregnancy and gestational diabetes include optimising nutrition, increasing physical activity, monitoring and controlling weight gain, additional monitoring activities including of fetal growth and wellbeing, and the use of medications. Medications include insulin and, increasingly, oral hypoglycaemics for women where adequate glycaemic control is not achieved using non-pharmacological measures. Optimising control of gestational diabetes is important to reduce pregnancy-related risks for the woman and baby, and may also have longer term implications on the health of the infant into adulthood. For women with gestational diabetes, screening for diabetes after delivery is also important as it provides an opportunity for intervention to improve women’s future health. 57

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s mothers and babies 2014. Perinatal statistics series no. 32. Canberra: AIHW, 2016.

- Humphrey MD, Bonello M, Chughtai A, Macaldowie A, Harris K, Chambers G. Maternal deaths in Australia 2008–12. Canberra: AIHW, 2015.

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. Clinical practice guidelines: Antenatal care – Module II. Canberra: Department of Health, 2014.

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. Clinical practice guidelines: Antenatal care – Module 1. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2012.

- Clarke M, Boyle J. Antenatal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Aus Fam Physician 2014;43(1/2):20–24.

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party. National Aboriginal Health Strategy. Canberra, 1989.

- Wilson G. What do Aboriginal women think is good antenatal care? Consultation Report. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009.

- McHugh AM, Hornbuckle J. Maternal and child health model of care in the Aboriginal community controlled health sector. Perth: Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia, 2011.

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework 2014 report. Canberra: Department of Health, 2015.

- Laws PG, Sullivan EA. Smoking and pregnancy. Sydney: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Perinatal Statistics Unit, 2006.

- Thomas DP, Briggs V, Anderson IP, Cunningham J. The social determinants of being an Indigenous non‐smoker. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32(2):110–16.

- Bond C, Brough M, Spurling G, Hayman N. ‘It had to be my choice’. Indigenous smoking cessation and negotiations of risk, resistance and resilience. Health Risk Soc 2012;14(6):565–81.

- Passey ME, Sanson-Fisher RW, D’Este CA, Stirling JM. Tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use during pregnancy: Clustering of risks. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;134:44–50.

- Passey ME, D’Este CA, Stirling JM, Sanson‐Fisher RW. Factors associated with antenatal smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in two jurisdictions. Drug Alcohol Rev 2012;31(5):608–16.

- Gould GS, Munn J, Watters T, McEwen A, Clough AR. Knowledge and views about maternal tobacco smoking and barriers for cessation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15(5):863–74.

- Passey ME, Sanson-Fisher RW. Provision of antenatal smoking cessation support: A survey with pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17(6):746–49.

- Passey ME, Sanson-Fisher RW, Stirling JM. Supporting pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to quit smoking: Views of antenatal care providers and pregnant Indigenous women. Maternal Child Health J 2014;18(10):2293–99.

- Chamberlain C, O’Mara‐Eves A, Porter J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD001055.

- Eades SJ, Sanson-Fisher RW, Wenitong M, et al. An intensive smoking intervention for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: A randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 2012;197(1):42.

- Gould GS, Bittoun R, Clarke MJ. Guidance for culturally competent approaches to smoking cessation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pregnant women. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18(1):104.

- Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi‐Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(12):CD010078.

- Bookallil M, Chalmers E, Andrew B. Challenges in preventing pyelonephritis in pregnant women in Indigenous communities. Rural Remote Health 2005;5(3):395.

- Panaretto KS, Lee HM, Mitchell MR, et al. Prevalence of STIs in pregnant urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in northern Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;46(3):217–24.

- Hunt J. Pregnancy care and problems for women giving birth at Royal Darwin Hospital. Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Mothers’ and Children’s Health, La Trobe University, 2004.

- Smaill FM, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(8):CD000490.

- Ryan GM Jr, Abdella TN, McNeeley SG, Baselski VS, Drummond DE. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy and effect of treatment on outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;162(1):34–39.

- McMillan JA, Weiner LB, Lamberson HV, et al. Efficacy of maternal screening and therapy in the prevention of chlamydia infection of the newborn. Infection 1985;13(6):263–66.

- Lewis D, Newton DC, Guy RJ, et al. The prevalence of chlamydia trachomatis infection in Australia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12(1):113.

- Graham S, Smith LW, Fairley CK, Hocking J. Prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichomonas in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Health 2016;13(2):99–113.

- The Kirby Institute. Bloodborne viral and sexually transmissible infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Surveillance and evaluation report 2015. Sydney: The Kirby Institute, 2016.

- Gülmezoglu AM, Azhar M. Interventions for trichomoniasis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(5):CD000220.

- Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, Milan SJ. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(1):CD000262.

- Walker GJ. Antibiotics for syphilis diagnosed during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(3):CD001143.

- Bright A, Dups J. Infectious and congenital syphilis notifications associated with an ongoing outbreak in northern Australia. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2016;40(1):E7–10.

- Thompson A. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection: A consensus statement. Med J Aust 2016;204(7):268–72.

- Graham S, Guy RJ, Cowie B, et al. Chronic hepatitis B prevalence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians since universal vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13(1):403.

- Schultz R. Hepatitis B screening among women birthing in Alice Springs Hospital, and immunisation of infants at risk. Northern Territory Disease Control Bulletin 2007;14(2):1–5.

- Campbell F, Johnson M, Messina J, Guillaume L, Goyder E. Behavioural interventions for weight management in pregnancy: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative data. BMC Public Health 2011;11(1):491.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia. Melbourne: NHMRC, 2013.

- Muktabhant B, Lawrie TA, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(6):CD007145.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey: Biomedical results, 2012–13. Canberra: ABS, 2014.

- National Blood Authority. Patient blood management guidelines: Module 5 – Obstetrics and maternity. Canberra: NBA, 2015.

- Bower C, D’Antoine H, Stanley FJ. Neural tube defects in Australia: Trends in encephaloceles and other neural tube defects before and after promotion of folic acid supplementation and voluntary food fortification. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009;85(4):269–73.

- Macaldowie A. Neural tube defects in Australia: Prevalence before mandatory folic acid fortification. Canberra: AIHW, 2011.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Monitoring the health impacts of mandatory folic acid and iodine fortification. Canberra: AIHW, 2016.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Iodine supplementation during pregnancy and lactation – A literature review. Canberra: NHMRC, 2009.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Iodine supplementation: Public statement. Canberra: NHMRC, 2010.

- Paxton GA, Teale GR, Nowson CA, et al. Vitamin D and health in pregnancy, infants, children and adolescents in Australia and New Zealand: A position statement. Med J Aust 2013;198(3):142–43.

- Benson J, Wilson A, Stocks N, Moulding N. Muscle pain as an indicator of vitamin D deficiency in an urban Australian Aboriginal population. Med J Aust 2006;185(2):76–77.

- Vanlint SJ, Morris HA, Newbury JW, Crockett AJ. Vitamin D insufficiency in Aboriginal Australians. Med J Aust 2011;194(3):131–34.

- Lowe LP, Metzger BE, Dyer AR, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome (HAPO) study. Diabetes Care 2012;35(3):574–80.

- Contreras M, Sacks DA, Bowling FG, et al. The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002;78(1):69–77.

- McElduff A, Cheung NW, McIntyre HD, et al. The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society consensus guidelines for the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in relation to pregnancy. Med J Aust 2005;183(7):373–77.

- Nankervis A, McIntyre H, Moses R, et al. ADIPS consensus guidelines for the testing and diagnosis of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy in Australia and New Zealand. Sydney: Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society, 2014.

- Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005;352(24):2477–86.

- Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009;361(14):1339–48.

- Chamberlain C, McLean A, Oats J, et al. Low rates of postpartum glucose screening among indigenous and non-indigenous women in Australia with gestational diabetes. Maternal Child Health J 2015;19(3):651–63.

- Cancer Council Australia Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines Working Party. National Cervical Screening Program: Guidelines for the management of screen-detected abnormalities, screening in specific populations and investigation of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia, 2016.

- Woolcock J, Grivell R. Noninvasive prenatal testing. Aust Fam Physician 2014;43(7):432–34.

- beyondblue. Clinical practice guidelines for depression and related disorders – anxiety, bipolar disorder and puerperal psychosis – in the perinatal period: A guideline for primary care health professionals. Melbourne: beyondblue, 2011.

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation. The Australian immunisation handbook. 10th edn. Canberra: Department of Health, 2017.

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obtetricians and Gynaecologists. Measurement of cervical length for prediction of preterm birth. Sydney: RANZCOG; 2017 . [Accessed 10 November 2017].

National guide to a preventive health assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (PDF 9.8 MB)

Evidence base to a preventive health assessment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (PDF 9.4 MB)

National Guide Lifecycle chart (child) (PDF 555 KB)

National Guide Lifecycle chart (young) (PDF 1 MB)

National Guide Lifecycle chart (adult) (PDF 1 MB)

Gravidity & Parity and GTPAL (Explained with Examples)

Last updated on December 28th, 2023

What is Gravidity & Parity and GTPAL?

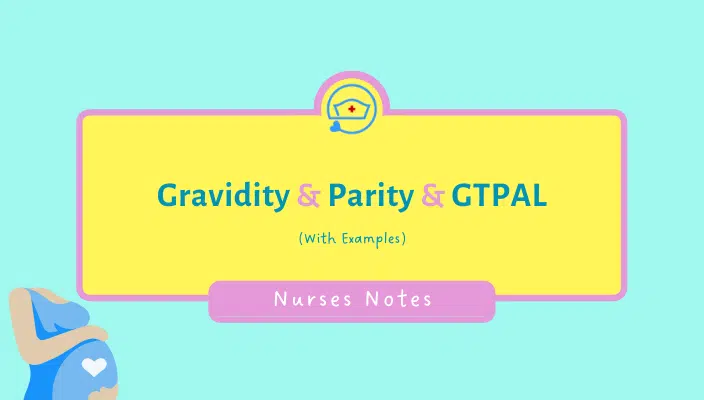

Gravidity and parity, and GTPAL are systems used in health assessment to record woman’s obstetric history.

Gravidity and parity (G P) is a basic 2-digit system that only gives information about the number of pregnancies and births. While 5-digit GTPAL system provides more comprehensive data on obstetric history at a glance.

Details of a woman’s gravidity and parity are important. Because it gives critical information to the healthcare team to determine the level of risks for complications and plan individualized patient care.

For example, an elderly primigravida is at higher risk for several complications like spontaneous abortion, fetal distress preterm labor, and prolonged labor.

Here, we’ll discuss GP and GTPAL systems in detail with examples.

Gravidity and Parity (GP 2-Digit Recording System)

Gravidity and parity (GP) are a 2-digit system to record pregnancy and birth history of the women. This is more basic method of recording obstetric history which only include information about woman’s number of pregnancies and births.

Gravidity refers to the total number of pregnancies regardless of its outcome. A pregnancy can end in a live birth, miscarriage, premature birth (before 37 weeks of gestation), or an abortion.

The term Gravida refers to a woman who is currently pregnant.

For example , a woman who is currently pregnant has previous history of 2 miscarriages will be G3.

Parity refers to the number births after 20 weeks of gestation. When calculating parity also, you include all births beyond 20 weeks of gestation whether or not the baby born was alive.

The term Para just indicates the number of pregnancies carried beyond 20 weeks of gestation.

For example , P2 means the woman has given birth twice from two pregnancies carried beyond 20 weeks of gestation regardless of the baby born was alive or stillborn.

Also, it’s important to remember that gravida and para refers to pregnancies and not to babies . That way it will be easier to answer those confusing scenario questions.

For example, a woman who delivers a twin at 38 weeks of gestation in her first pregnancy is still a gravida one (G1) and para one (P1).

GTPAL 5-Digit Recording System

GTPAL is the acronym for a 5-digit system of recording women’s obstetric history. It is just an extended version of the TPAL recording system with the addition of gravidity.

GTPAL provides quick overview of the person’s term and preterm pregnancies, abortions, and number of living children.

In the table below, you’ll see a description of the GTPAL acronym.

Common Terminologies with Definition

Click HERE to learn more about Leopold Maneuvers

GP vs GTPAL Explained with Scenarios

Scenario 1: gravida and para for twins.

Sara is currently 38 weeks pregnant and has a history of 1 spontaneous abortion at 12 weeks of gestation and 1 normal vaginal delivery of twin boys at 37 weeks of gestation. So, how would you record her basic gravidity and parity using GP system?

Answer: According to GP system she is G3, P1.

Rationale: She conceived total 3 times (i.e.: 1 abortion, 1 normal delivery, and current pregnancy). So, she is gravida 3 (i.e.: G3).

But, she only carried 1 pregnancy to a stage of viability (beyond 20 weeks gestation) where she delivered twins. So, she is para 1 (i.e.: P1).

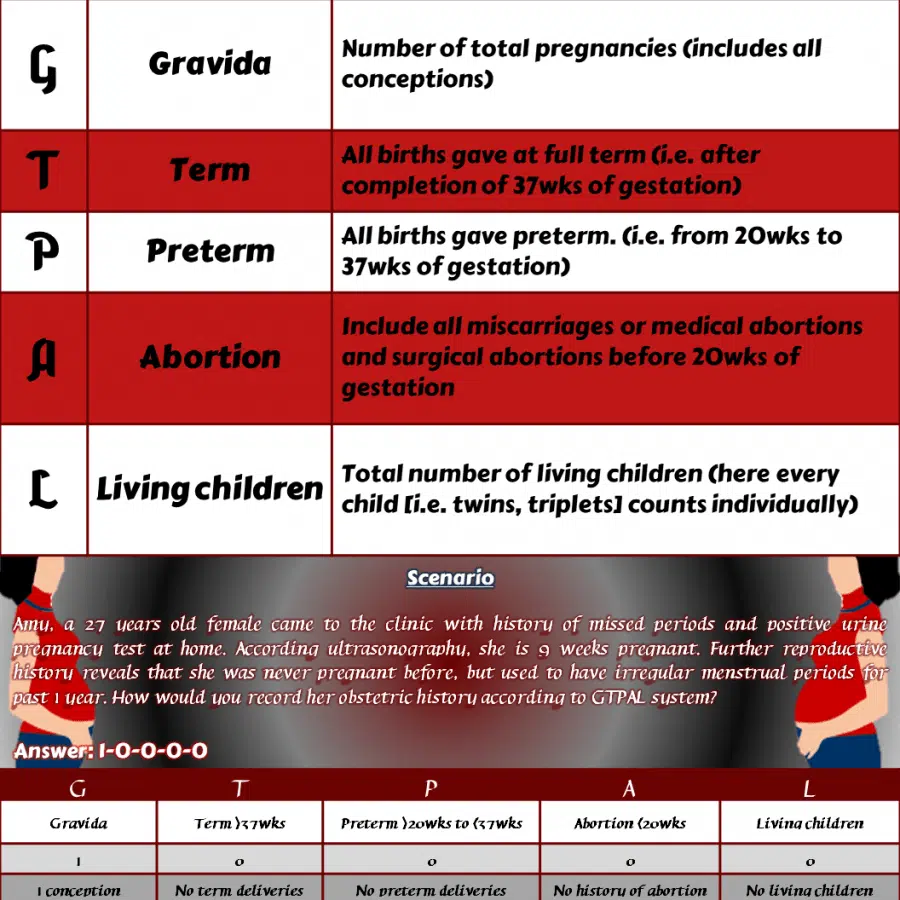

Scenario 2: GTPAL for Primigravida

Amy, a 27 years old female came to the clinic with history of missed periods and positive urine pregnancy test at home. According ultrasonography, she is 9 weeks pregnant. Further reproductive history reveals that she was never pregnant before, but used to have irregular menstrual periods for past 1 year. How would you record her obstetric history according to GTPAL system?

Answer: According to GTPAL system she is 1-0-0-0-0

Rationale: This is her very 1 st conception. So, she is a primigravida.

Scenario 3: GP and GTPAL for Preterm Twins

A woman who is 13 weeks pregnant, has a history of loss of 2 previous pregnancies at 10 weeks and 9 weeks of gestation respectively. She has 3 children, 1st child was delivered via normal vaginal delivery at 38 weeks. The second time she delivered twin girls at 36 weeks of gestation by LSCS due to PROM. What is her gravidity and parity according to the GP system and GTPAL?

Answer: According to GP system she is G5 P2 and according to GPTAL she is 5-1-1-2-3.

Rationale: Gravida includes all conceptions which includes present pregnancy and previous abortions as well. So, she is gravida 5. On the other hand, Para includes only previous pregnancies beyond the period of viability (i.e: pregnancies that carried beyond 20 weeks of gestation). So, she is para 2.

( Also note that number of babies born will be not included in gravidity and parity )

(Note that multiple or singleton pregnancies will be counted as 1 conception)

Scenario 4: GTPAL for Ectopic Pregnancy and Stillborn

Sandy just medically terminated her ectopic pregnancy at 10 weeks. This was her fifth pregnancy. Sadly, her first and fourth pregnancies also ended in a spontaneous loss at 16 and 24 weeks respectively. All her pregnancies have been singletons (one baby), one born living at 39 weeks and one stillbirth at 38 weeks. What is her gravidity and parity using GTPAL system?

Answer: GTPAL is 5-2-1-2-1.

Scenario 5: GTPAL for Twins

A woman is currently pregnant with twins. She is in her first trimester now. Also, she has a history of one previous twin delivery at 38 weeks. That pregnancy was uneventful. Both kids are living and just turned 4. Using GTPAL acronym, how would you record this obstetric history?

Casanova, R., Chuang, A., Goepfert, A., Hueppchen, N., & Weiss, P. (2019). Beckmann and Ling’s Obstetrics and Gynecology (8th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Konar, H. (2015). DC Dutta’s textbook of obstetrics (8th ed). JP Brothers Medical.

O’Toole, M. (2013). Mosby’s medical dictionary (9th ed.). Elsevier.

Medical & Legal Disclaimer

All the contents on this site are for entertainment, informational, educational, and example purposes ONLY. These contents are not intended to be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or practice guidelines. However, we aim to publish precise and current information. By using any content on this website, you agree never to hold us legally liable for damages, harm, loss, or misinformation. Read the privacy policy and terms and conditions.

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

© 2024 nurseship.com. All rights reserved.

- Skip to content

- Accessibility help

Antenatal care - uncomplicated pregnancy

Last revised in February 2023

A woman with an uncomplicated pregnancy is usually managed in the community by a midwife.

- Scenario: Antenatal care - uncomplicated pregnancy

- Scenario: Managing common minor ailments

Background information

Antenatal care - uncomplicated pregnancy: summary.

- Women with uncomplicated pregnancies are usually managed in the community by a midwife. GPs, obstetricians, and specialist teams become involved when additional care is needed.

- 10 antenatal appointments for nulliparous women or 7 antenatal appointments for parous women.

- 2 ultrasound scans — a ‘dating scan’ (between 11+2 weeks and 14+1 weeks) and a ‘fetal anomaly scan’ (between 18+0 weeks and 20+6 weeks).

- Management at each appointment depends on the stage of the pregnancy.

- Women who may need additional care should be identified and referred to secondary care.

- Advice on vitamins and supplements in pregnancy (including folic acid and vitamin D) and lifestyle factors that may affect the pregnancy (including diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use) should be provided from first contact.

- The risks, benefits, and limitations of NHS screening programmes in pregnancy (including infectious disease screening [HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B], sickle cell and thalassaemia screening, and screening for fetal anomalies) should be discussed and the woman advised that they can accept or decline any part of any of these.

- Immunization for flu, whooping cough, and other infections such as COVID-19.

- Infections that can impact on the baby in pregnancy or during birth (such as group B streptococcus).

- Reducing the risk of infections.

- Safe use of medicines and health supplements.

- Mental health.

- Lifestyle including nutrition and diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use.

- Sleep position after 28 weeks of pregnancy.

- Travel including air travel.

- Occupation.

- Blood pressure measurement and a urine dipstick test for proteinuria should be offered at each appointment.

- Advice on the symptoms of pre-eclampsia and when to seek immediate medical help should be discussed with all pregnant women.

- The symphysis–fundal height (to identify small- or large-for-gestational-age infants) should be measured and plotted.

- The baby’s movements should be discussed and the woman advised to contact maternity services at any time of day or night if she has any concerns about her baby’s movements or notices reduced movements.

- At 28 weeks of pregnancy, routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis should be offered to rhesus-negative women.