Is Time Travel Possible?

We all travel in time! We travel one year in time between birthdays, for example. And we are all traveling in time at approximately the same speed: 1 second per second.

We typically experience time at one second per second. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

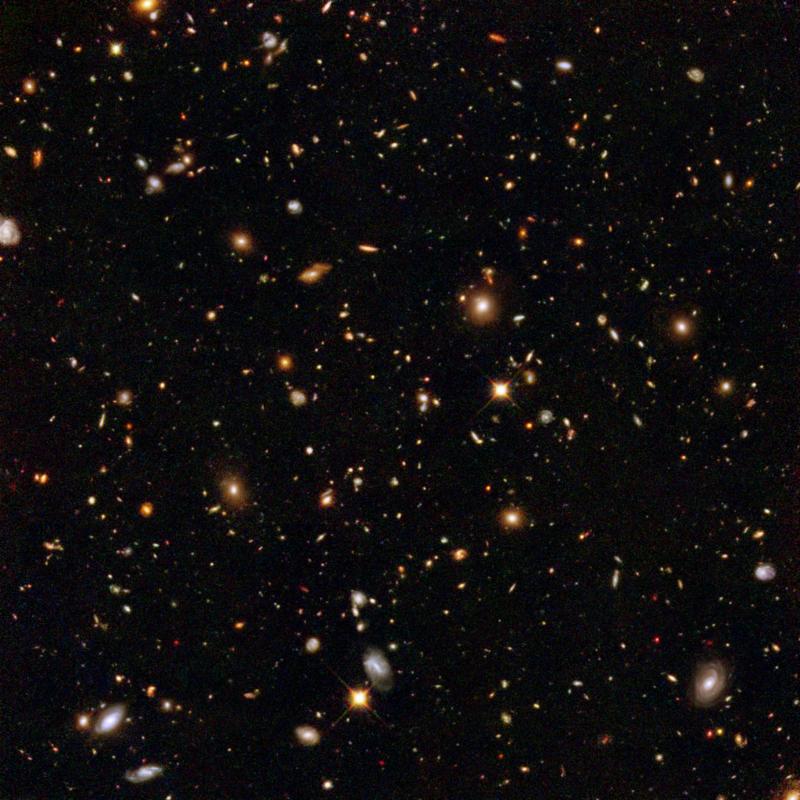

NASA's space telescopes also give us a way to look back in time. Telescopes help us see stars and galaxies that are very far away . It takes a long time for the light from faraway galaxies to reach us. So, when we look into the sky with a telescope, we are seeing what those stars and galaxies looked like a very long time ago.

However, when we think of the phrase "time travel," we are usually thinking of traveling faster than 1 second per second. That kind of time travel sounds like something you'd only see in movies or science fiction books. Could it be real? Science says yes!

This image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows galaxies that are very far away as they existed a very long time ago. Credit: NASA, ESA and R. Thompson (Univ. Arizona)

How do we know that time travel is possible?

More than 100 years ago, a famous scientist named Albert Einstein came up with an idea about how time works. He called it relativity. This theory says that time and space are linked together. Einstein also said our universe has a speed limit: nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (186,000 miles per second).

Einstein's theory of relativity says that space and time are linked together. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

What does this mean for time travel? Well, according to this theory, the faster you travel, the slower you experience time. Scientists have done some experiments to show that this is true.

For example, there was an experiment that used two clocks set to the exact same time. One clock stayed on Earth, while the other flew in an airplane (going in the same direction Earth rotates).

After the airplane flew around the world, scientists compared the two clocks. The clock on the fast-moving airplane was slightly behind the clock on the ground. So, the clock on the airplane was traveling slightly slower in time than 1 second per second.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Can we use time travel in everyday life?

We can't use a time machine to travel hundreds of years into the past or future. That kind of time travel only happens in books and movies. But the math of time travel does affect the things we use every day.

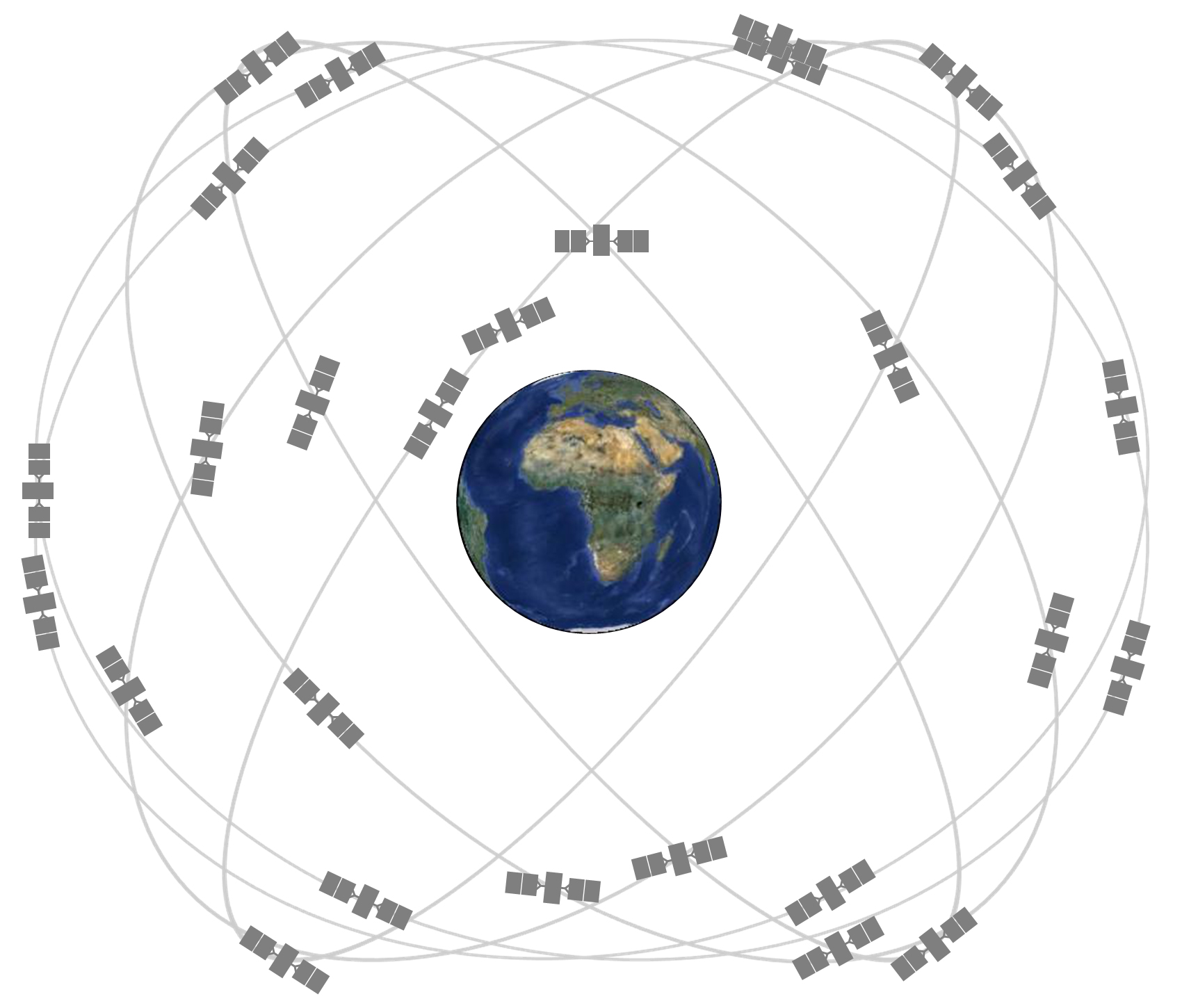

For example, we use GPS satellites to help us figure out how to get to new places. (Check out our video about how GPS satellites work .) NASA scientists also use a high-accuracy version of GPS to keep track of where satellites are in space. But did you know that GPS relies on time-travel calculations to help you get around town?

GPS satellites orbit around Earth very quickly at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. This slows down GPS satellite clocks by a small fraction of a second (similar to the airplane example above).

GPS satellites orbit around Earth at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. Credit: GPS.gov

However, the satellites are also orbiting Earth about 12,550 miles (20,200 km) above the surface. This actually speeds up GPS satellite clocks by a slighter larger fraction of a second.

Here's how: Einstein's theory also says that gravity curves space and time, causing the passage of time to slow down. High up where the satellites orbit, Earth's gravity is much weaker. This causes the clocks on GPS satellites to run faster than clocks on the ground.

The combined result is that the clocks on GPS satellites experience time at a rate slightly faster than 1 second per second. Luckily, scientists can use math to correct these differences in time.

If scientists didn't correct the GPS clocks, there would be big problems. GPS satellites wouldn't be able to correctly calculate their position or yours. The errors would add up to a few miles each day, which is a big deal. GPS maps might think your home is nowhere near where it actually is!

In Summary:

Yes, time travel is indeed a real thing. But it's not quite what you've probably seen in the movies. Under certain conditions, it is possible to experience time passing at a different rate than 1 second per second. And there are important reasons why we need to understand this real-world form of time travel.

If you liked this, you may like:

April 26, 2023

Is Time Travel Possible?

The laws of physics allow time travel. So why haven’t people become chronological hoppers?

By Sarah Scoles

yuanyuan yan/Getty Images

In the movies, time travelers typically step inside a machine and—poof—disappear. They then reappear instantaneously among cowboys, knights or dinosaurs. What these films show is basically time teleportation .

Scientists don’t think this conception is likely in the real world, but they also don’t relegate time travel to the crackpot realm. In fact, the laws of physics might allow chronological hopping, but the devil is in the details.

Time traveling to the near future is easy: you’re doing it right now at a rate of one second per second, and physicists say that rate can change. According to Einstein’s special theory of relativity, time’s flow depends on how fast you’re moving. The quicker you travel, the slower seconds pass. And according to Einstein’s general theory of relativity , gravity also affects clocks: the more forceful the gravity nearby, the slower time goes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Near massive bodies—near the surface of neutron stars or even at the surface of the Earth, although it’s a tiny effect—time runs slower than it does far away,” says Dave Goldberg, a cosmologist at Drexel University.

If a person were to hang out near the edge of a black hole , where gravity is prodigious, Goldberg says, only a few hours might pass for them while 1,000 years went by for someone on Earth. If the person who was near the black hole returned to this planet, they would have effectively traveled to the future. “That is a real effect,” he says. “That is completely uncontroversial.”

Going backward in time gets thorny, though (thornier than getting ripped to shreds inside a black hole). Scientists have come up with a few ways it might be possible, and they have been aware of time travel paradoxes in general relativity for decades. Fabio Costa, a physicist at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics, notes that an early solution with time travel began with a scenario written in the 1920s. That idea involved massive long cylinder that spun fast in the manner of straw rolled between your palms and that twisted spacetime along with it. The understanding that this object could act as a time machine allowing one to travel to the past only happened in the 1970s, a few decades after scientists had discovered a phenomenon called “closed timelike curves.”

“A closed timelike curve describes the trajectory of a hypothetical observer that, while always traveling forward in time from their own perspective, at some point finds themselves at the same place and time where they started, creating a loop,” Costa says. “This is possible in a region of spacetime that, warped by gravity, loops into itself.”

“Einstein read [about closed timelike curves] and was very disturbed by this idea,” he adds. The phenomenon nevertheless spurred later research.

Science began to take time travel seriously in the 1980s. In 1990, for instance, Russian physicist Igor Novikov and American physicist Kip Thorne collaborated on a research paper about closed time-like curves. “They started to study not only how one could try to build a time machine but also how it would work,” Costa says.

Just as importantly, though, they investigated the problems with time travel. What if, for instance, you tossed a billiard ball into a time machine, and it traveled to the past and then collided with its past self in a way that meant its present self could never enter the time machine? “That looks like a paradox,” Costa says.

Since the 1990s, he says, there’s been on-and-off interest in the topic yet no big breakthrough. The field isn’t very active today, in part because every proposed model of a time machine has problems. “It has some attractive features, possibly some potential, but then when one starts to sort of unravel the details, there ends up being some kind of a roadblock,” says Gaurav Khanna of the University of Rhode Island.

For instance, most time travel models require negative mass —and hence negative energy because, as Albert Einstein revealed when he discovered E = mc 2 , mass and energy are one and the same. In theory, at least, just as an electric charge can be positive or negative, so can mass—though no one’s ever found an example of negative mass. Why does time travel depend on such exotic matter? In many cases, it is needed to hold open a wormhole—a tunnel in spacetime predicted by general relativity that connects one point in the cosmos to another.

Without negative mass, gravity would cause this tunnel to collapse. “You can think of it as counteracting the positive mass or energy that wants to traverse the wormhole,” Goldberg says.

Khanna and Goldberg concur that it’s unlikely matter with negative mass even exists, although Khanna notes that some quantum phenomena show promise, for instance, for negative energy on very small scales. But that would be “nowhere close to the scale that would be needed” for a realistic time machine, he says.

These challenges explain why Khanna initially discouraged Caroline Mallary, then his graduate student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, from doing a time travel project. Mallary and Khanna went forward anyway and came up with a theoretical time machine that didn’t require negative mass. In its simplistic form, Mallary’s idea involves two parallel cars, each made of regular matter. If you leave one parked and zoom the other with extreme acceleration, a closed timelike curve will form between them.

Easy, right? But while Mallary’s model gets rid of the need for negative matter, it adds another hurdle: it requires infinite density inside the cars for them to affect spacetime in a way that would be useful for time travel. Infinite density can be found inside a black hole, where gravity is so intense that it squishes matter into a mind-bogglingly small space called a singularity. In the model, each of the cars needs to contain such a singularity. “One of the reasons that there's not a lot of active research on this sort of thing is because of these constraints,” Mallary says.

Other researchers have created models of time travel that involve a wormhole, or a tunnel in spacetime from one point in the cosmos to another. “It's sort of a shortcut through the universe,” Goldberg says. Imagine accelerating one end of the wormhole to near the speed of light and then sending it back to where it came from. “Those two sides are no longer synced,” he says. “One is in the past; one is in the future.” Walk between them, and you’re time traveling.

You could accomplish something similar by moving one end of the wormhole near a big gravitational field—such as a black hole—while keeping the other end near a smaller gravitational force. In that way, time would slow down on the big gravity side, essentially allowing a particle or some other chunk of mass to reside in the past relative to the other side of the wormhole.

Making a wormhole requires pesky negative mass and energy, however. A wormhole created from normal mass would collapse because of gravity. “Most designs tend to have some similar sorts of issues,” Goldberg says. They’re theoretically possible, but there’s currently no feasible way to make them, kind of like a good-tasting pizza with no calories.

And maybe the problem is not just that we don’t know how to make time travel machines but also that it’s not possible to do so except on microscopic scales—a belief held by the late physicist Stephen Hawking. He proposed the chronology protection conjecture: The universe doesn’t allow time travel because it doesn’t allow alterations to the past. “It seems there is a chronology protection agency, which prevents the appearance of closed timelike curves and so makes the universe safe for historians,” Hawking wrote in a 1992 paper in Physical Review D .

Part of his reasoning involved the paradoxes time travel would create such as the aforementioned situation with a billiard ball and its more famous counterpart, the grandfather paradox : If you go back in time and kill your grandfather before he has children, you can’t be born, and therefore you can’t time travel, and therefore you couldn’t have killed your grandfather. And yet there you are.

Those complications are what interests Massachusetts Institute of Technology philosopher Agustin Rayo, however, because the paradoxes don’t just call causality and chronology into question. They also make free will seem suspect. If physics says you can go back in time, then why can’t you kill your grandfather? “What stops you?” he says. Are you not free?

Rayo suspects that time travel is consistent with free will, though. “What’s past is past,” he says. “So if, in fact, my grandfather survived long enough to have children, traveling back in time isn’t going to change that. Why will I fail if I try? I don’t know because I don’t have enough information about the past. What I do know is that I’ll fail somehow.”

If you went to kill your grandfather, in other words, you’d perhaps slip on a banana en route or miss the bus. “It's not like you would find some special force compelling you not to do it,” Costa says. “You would fail to do it for perfectly mundane reasons.”

In 2020 Costa worked with Germain Tobar, then his undergraduate student at the University of Queensland in Australia, on the math that would underlie a similar idea: that time travel is possible without paradoxes and with freedom of choice.

Goldberg agrees with them in a way. “I definitely fall into the category of [thinking that] if there is time travel, it will be constructed in such a way that it produces one self-consistent view of history,” he says. “Because that seems to be the way that all the rest of our physical laws are constructed.”

No one knows what the future of time travel to the past will hold. And so far, no time travelers have come to tell us about it.

Is time travel possible? Why one scientist says we 'cannot ignore the possibility.'

A common theme in science-fiction media , time travel is captivating. It’s defined by the late philosopher David Lewis in his essay “The Paradoxes of Time Travel” as “[involving] a discrepancy between time and space time. Any traveler departs and then arrives at his destination; the time elapsed from departure to arrival … is the duration of the journey.”

Time travel is usually understood by most as going back to a bygone era or jumping forward to a point far in the future . But how much of the idea is based in reality? Is it possible to travel through time?

Is time travel possible?

According to NASA, time travel is possible , just not in the way you might expect. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity says time and motion are relative to each other, and nothing can go faster than the speed of light , which is 186,000 miles per second. Time travel happens through what’s called “time dilation.”

Time dilation , according to Live Science, is how one’s perception of time is different to another's, depending on their motion or where they are. Hence, time being relative.

Learn more: Best travel insurance

Dr. Ana Alonso-Serrano, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Germany, explained the possibility of time travel and how researchers test theories.

Space and time are not absolute values, Alonso-Serrano said. And what makes this all more complex is that you are able to carve space-time .

“In the moment that you carve the space-time, you can play with that curvature to make the time come in a circle and make a time machine,” Alonso-Serrano told USA TODAY.

She explained how, theoretically, time travel is possible. The mathematics behind creating curvature of space-time are solid, but trying to re-create the strict physical conditions needed to prove these theories can be challenging.

“The tricky point of that is if you can find a physical, realistic, way to do it,” she said.

Alonso-Serrano said wormholes and warp drives are tools that are used to create this curvature. The matter needed to achieve curving space-time via a wormhole is exotic matter , which hasn’t been done successfully. Researchers don’t even know if this type of matter exists, she said.

“It's something that we work on because it's theoretically possible, and because it's a very nice way to test our theory, to look for possible paradoxes,” Alonso-Serrano added.

“I could not say that nothing is possible, but I cannot ignore the possibility,” she said.

She also mentioned the anecdote of Stephen Hawking’s Champagne party for time travelers . Hawking had a GPS-specific location for the party. He didn’t send out invites until the party had already happened, so only people who could travel to the past would be able to attend. No one showed up, and Hawking referred to this event as "experimental evidence" that time travel wasn't possible.

What did Albert Einstein invent?: Discoveries that changed the world

Just Curious for more? We've got you covered

USA TODAY is exploring the questions you and others ask every day. From "How to watch the Marvel movies in order" to "Why is Pluto not a planet?" to "What to do if your dog eats weed?" – we're striving to find answers to the most common questions you ask every day. Head to our Just Curious section to see what else we can answer for you.

Time travel: Is it possible?

Science says time travel is possible, but probably not in the way you're thinking.

Albert Einstein's theory

- General relativity and GPS

- Wormhole travel

- Alternate theories

Science fiction

Is time travel possible? Short answer: Yes, and you're doing it right now — hurtling into the future at the impressive rate of one second per second.

You're pretty much always moving through time at the same speed, whether you're watching paint dry or wishing you had more hours to visit with a friend from out of town.

But this isn't the kind of time travel that's captivated countless science fiction writers, or spurred a genre so extensive that Wikipedia lists over 400 titles in the category "Movies about Time Travel." In franchises like " Doctor Who ," " Star Trek ," and "Back to the Future" characters climb into some wild vehicle to blast into the past or spin into the future. Once the characters have traveled through time, they grapple with what happens if you change the past or present based on information from the future (which is where time travel stories intersect with the idea of parallel universes or alternate timelines).

Related: The best sci-fi time machines ever

Although many people are fascinated by the idea of changing the past or seeing the future before it's due, no person has ever demonstrated the kind of back-and-forth time travel seen in science fiction or proposed a method of sending a person through significant periods of time that wouldn't destroy them on the way. And, as physicist Stephen Hawking pointed out in his book " Black Holes and Baby Universes" (Bantam, 1994), "The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future."

Science does support some amount of time-bending, though. For example, physicist Albert Einstein 's theory of special relativity proposes that time is an illusion that moves relative to an observer. An observer traveling near the speed of light will experience time, with all its aftereffects (boredom, aging, etc.) much more slowly than an observer at rest. That's why astronaut Scott Kelly aged ever so slightly less over the course of a year in orbit than his twin brother who stayed here on Earth.

Related: Controversially, physicist argues that time is real

There are other scientific theories about time travel, including some weird physics that arise around wormholes , black holes and string theory . For the most part, though, time travel remains the domain of an ever-growing array of science fiction books, movies, television shows, comics, video games and more.

Einstein developed his theory of special relativity in 1905. Along with his later expansion, the theory of general relativity , it has become one of the foundational tenets of modern physics. Special relativity describes the relationship between space and time for objects moving at constant speeds in a straight line.

The short version of the theory is deceptively simple. First, all things are measured in relation to something else — that is to say, there is no "absolute" frame of reference. Second, the speed of light is constant. It stays the same no matter what, and no matter where it's measured from. And third, nothing can go faster than the speed of light.

From those simple tenets unfolds actual, real-life time travel. An observer traveling at high velocity will experience time at a slower rate than an observer who isn't speeding through space.

While we don't accelerate humans to near-light-speed, we do send them swinging around the planet at 17,500 mph (28,160 km/h) aboard the International Space Station . Astronaut Scott Kelly was born after his twin brother, and fellow astronaut, Mark Kelly . Scott Kelly spent 520 days in orbit, while Mark logged 54 days in space. The difference in the speed at which they experienced time over the course of their lifetimes has actually widened the age gap between the two men.

"So, where[as] I used to be just 6 minutes older, now I am 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds older," Mark Kelly said in a panel discussion on July 12, 2020, Space.com previously reported . "Now I've got that over his head."

General relativity and GPS time travel

The difference that low earth orbit makes in an astronaut's life span may be negligible — better suited for jokes among siblings than actual life extension or visiting the distant future — but the dilation in time between people on Earth and GPS satellites flying through space does make a difference.

Read more: Can we stop time?

The Global Positioning System , or GPS, helps us know exactly where we are by communicating with a network of a few dozen satellites positioned in a high Earth orbit. The satellites circle the planet from 12,500 miles (20,100 kilometers) away, moving at 8,700 mph (14,000 km/h).

According to special relativity, the faster an object moves relative to another object, the slower that first object experiences time. For GPS satellites with atomic clocks, this effect cuts 7 microseconds, or 7 millionths of a second, off each day, according to the American Physical Society publication Physics Central .

Read more: Could Star Trek's faster-than-light warp drive actually work?

Then, according to general relativity, clocks closer to the center of a large gravitational mass like Earth tick more slowly than those farther away. So, because the GPS satellites are much farther from the center of Earth compared to clocks on the surface, Physics Central added, that adds another 45 microseconds onto the GPS satellite clocks each day. Combined with the negative 7 microseconds from the special relativity calculation, the net result is an added 38 microseconds.

This means that in order to maintain the accuracy needed to pinpoint your car or phone — or, since the system is run by the U.S. Department of Defense, a military drone — engineers must account for an extra 38 microseconds in each satellite's day. The atomic clocks onboard don’t tick over to the next day until they have run 38 microseconds longer than comparable clocks on Earth.

Given those numbers, it would take more than seven years for the atomic clock in a GPS satellite to un-sync itself from an Earth clock by more than a blink of an eye. (We did the math: If you estimate a blink to last at least 100,000 microseconds, as the Harvard Database of Useful Biological Numbers does, it would take thousands of days for those 38 microsecond shifts to add up.)

This kind of time travel may seem as negligible as the Kelly brothers' age gap, but given the hyper-accuracy of modern GPS technology, it actually does matter. If it can communicate with the satellites whizzing overhead, your phone can nail down your location in space and time with incredible accuracy.

Can wormholes take us back in time?

General relativity might also provide scenarios that could allow travelers to go back in time, according to NASA . But the physical reality of those time-travel methods is no piece of cake.

Wormholes are theoretical "tunnels" through the fabric of space-time that could connect different moments or locations in reality to others. Also known as Einstein-Rosen bridges or white holes, as opposed to black holes, speculation about wormholes abounds. But despite taking up a lot of space (or space-time) in science fiction, no wormholes of any kind have been identified in real life.

Related: Best time travel movies

"The whole thing is very hypothetical at this point," Stephen Hsu, a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Oregon, told Space.com sister site Live Science . "No one thinks we're going to find a wormhole anytime soon."

Primordial wormholes are predicted to be just 10^-34 inches (10^-33 centimeters) at the tunnel's "mouth". Previously, they were expected to be too unstable for anything to be able to travel through them. However, a study claims that this is not the case, Live Science reported .

The theory, which suggests that wormholes could work as viable space-time shortcuts, was described by physicist Pascal Koiran. As part of the study, Koiran used the Eddington-Finkelstein metric, as opposed to the Schwarzschild metric which has been used in the majority of previous analyses.

In the past, the path of a particle could not be traced through a hypothetical wormhole. However, using the Eddington-Finkelstein metric, the physicist was able to achieve just that.

Koiran's paper was described in October 2021, in the preprint database arXiv , before being published in the Journal of Modern Physics D.

Alternate time travel theories

While Einstein's theories appear to make time travel difficult, some researchers have proposed other solutions that could allow jumps back and forth in time. These alternate theories share one major flaw: As far as scientists can tell, there's no way a person could survive the kind of gravitational pulling and pushing that each solution requires.

Infinite cylinder theory

Astronomer Frank Tipler proposed a mechanism (sometimes known as a Tipler Cylinder ) where one could take matter that is 10 times the sun's mass, then roll it into a very long, but very dense cylinder. The Anderson Institute , a time travel research organization, described the cylinder as "a black hole that has passed through a spaghetti factory."

After spinning this black hole spaghetti a few billion revolutions per minute, a spaceship nearby — following a very precise spiral around the cylinder — could travel backward in time on a "closed, time-like curve," according to the Anderson Institute.

The major problem is that in order for the Tipler Cylinder to become reality, the cylinder would need to be infinitely long or be made of some unknown kind of matter. At least for the foreseeable future, endless interstellar pasta is beyond our reach.

Time donuts

Theoretical physicist Amos Ori at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel, proposed a model for a time machine made out of curved space-time — a donut-shaped vacuum surrounded by a sphere of normal matter.

"The machine is space-time itself," Ori told Live Science . "If we were to create an area with a warp like this in space that would enable time lines to close on themselves, it might enable future generations to return to visit our time."

Amos Ori is a theoretical physicist at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel. His research interests and publications span the fields of general relativity, black holes, gravitational waves and closed time lines.

There are a few caveats to Ori's time machine. First, visitors to the past wouldn't be able to travel to times earlier than the invention and construction of the time donut. Second, and more importantly, the invention and construction of this machine would depend on our ability to manipulate gravitational fields at will — a feat that may be theoretically possible but is certainly beyond our immediate reach.

Time travel has long occupied a significant place in fiction. Since as early as the "Mahabharata," an ancient Sanskrit epic poem compiled around 400 B.C., humans have dreamed of warping time, Lisa Yaszek, a professor of science fiction studies at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, told Live Science .

Every work of time-travel fiction creates its own version of space-time, glossing over one or more scientific hurdles and paradoxes to achieve its plot requirements.

Some make a nod to research and physics, like " Interstellar ," a 2014 film directed by Christopher Nolan. In the movie, a character played by Matthew McConaughey spends a few hours on a planet orbiting a supermassive black hole, but because of time dilation, observers on Earth experience those hours as a matter of decades.

Others take a more whimsical approach, like the "Doctor Who" television series. The series features the Doctor, an extraterrestrial "Time Lord" who travels in a spaceship resembling a blue British police box. "People assume," the Doctor explained in the show, "that time is a strict progression from cause to effect, but actually from a non-linear, non-subjective viewpoint, it's more like a big ball of wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff."

Long-standing franchises like the "Star Trek" movies and television series, as well as comic universes like DC and Marvel Comics, revisit the idea of time travel over and over.

Related: Marvel movies in order: chronological & release order

Here is an incomplete (and deeply subjective) list of some influential or notable works of time travel fiction:

Books about time travel:

- Rip Van Winkle (Cornelius S. Van Winkle, 1819) by Washington Irving

- A Christmas Carol (Chapman & Hall, 1843) by Charles Dickens

- The Time Machine (William Heinemann, 1895) by H. G. Wells

- A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Charles L. Webster and Co., 1889) by Mark Twain

- The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (Pan Books, 1980) by Douglas Adams

- A Tale of Time City (Methuen, 1987) by Diana Wynn Jones

- The Outlander series (Delacorte Press, 1991-present) by Diana Gabaldon

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Bloomsbury/Scholastic, 1999) by J. K. Rowling

- Thief of Time (Doubleday, 2001) by Terry Pratchett

- The Time Traveler's Wife (MacAdam/Cage, 2003) by Audrey Niffenegger

- All You Need is Kill (Shueisha, 2004) by Hiroshi Sakurazaka

Movies about time travel:

- Planet of the Apes (1968)

- Superman (1978)

- Time Bandits (1981)

- The Terminator (1984)

- Back to the Future series (1985, 1989, 1990)

- Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

- Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure (1989)

- Groundhog Day (1993)

- Galaxy Quest (1999)

- The Butterfly Effect (2004)

- 13 Going on 30 (2004)

- The Lake House (2006)

- Meet the Robinsons (2007)

- Hot Tub Time Machine (2010)

- Midnight in Paris (2011)

- Looper (2012)

- X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014)

- Edge of Tomorrow (2014)

- Interstellar (2014)

- Doctor Strange (2016)

- A Wrinkle in Time (2018)

- The Last Sharknado: It's About Time (2018)

- Avengers: Endgame (2019)

- Tenet (2020)

- Palm Springs (2020)

- Zach Snyder's Justice League (2021)

- The Tomorrow War (2021)

Television about time travel:

- Doctor Who (1963-present)

- The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) (multiple episodes)

- Star Trek (multiple series, multiple episodes)

- Samurai Jack (2001-2004)

- Lost (2004-2010)

- Phil of the Future (2004-2006)

- Steins;Gate (2011)

- Outlander (2014-2023)

- Loki (2021-present)

Games about time travel:

- Chrono Trigger (1995)

- TimeSplitters (2000-2005)

- Kingdom Hearts (2002-2019)

- Prince of Persia: Sands of Time (2003)

- God of War II (2007)

- Ratchet and Clank Future: A Crack In Time (2009)

- Sly Cooper: Thieves in Time (2013)

- Dishonored 2 (2016)

- Titanfall 2 (2016)

- Outer Wilds (2019)

Additional resources

Explore physicist Peter Millington's thoughts about Stephen Hawking's time travel theories at The Conversation . Check out a kid-friendly explanation of real-world time travel from NASA's Space Place . For an overview of time travel in fiction and the collective consciousness, read " Time Travel: A History " (Pantheon, 2016) by James Gleik.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ailsa is a staff writer for How It Works magazine, where she writes science, technology, space, history and environment features. Based in the U.K., she graduated from the University of Stirling with a BA (Hons) journalism degree. Previously, Ailsa has written for Cardiff Times magazine, Psychology Now and numerous science bookazines.

Car-size asteroid gives Earth a super-close shave with flyby closer than some satellites

SpaceX launches advanced weather satellite for US Space Force (video)

Why I watched the solar eclipse with my kids, a goose and 2,000 trees

Most Popular

- 2 Rocket Lab to launch NASA's new solar sail technology no earlier than April 24

- 3 Nuclear fusion reactor in South Korea runs at 100 million degrees C for a record-breaking 48 seconds

- 4 1st female ISS program manager looks ahead to new spaceships, space stations (exclusive)

- 5 This little robot can hop in zero-gravity to explore asteroids

We have completed maintenance on Astronomy.com and action may be required on your account. Learn More

- Login/Register

- Solar System

- Exotic Objects

- Upcoming Events

- Deep-Sky Objects

- Observing Basics

- Telescopes and Equipment

- Astrophotography

- Space Exploration

- Human Spaceflight

- Robotic Spaceflight

- The Magazine

Is time travel possible? An astrophysicist explains

Will it ever be possible for time travel to occur? – Alana C., age 12, Queens, New York

Have you ever dreamed of traveling through time, like characters do in science fiction movies? For centuries, the concept of time travel has captivated people’s imaginations. Time travel is the concept of moving between different points in time, just like you move between different places. In movies, you might have seen characters using special machines, magical devices or even hopping into a futuristic car to travel backward or forward in time.

But is this just a fun idea for movies, or could it really happen?

The question of whether time is reversible remains one of the biggest unresolved questions in science. If the universe follows the laws of thermodynamics , it may not be possible. The second law of thermodynamics states that things in the universe can either remain the same or become more disordered over time.

It’s a bit like saying you can’t unscramble eggs once they’ve been cooked. According to this law, the universe can never go back exactly to how it was before. Time can only go forward, like a one-way street.

Time is relative

However, physicist Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity suggests that time passes at different rates for different people. Someone speeding along on a spaceship moving close to the speed of light – 671 million miles per hour! – will experience time slower than a person on Earth.

Related: The speed of light, explained

People have yet to build spaceships that can move at speeds anywhere near as fast as light, but astronauts who visit the International Space Station orbit around the Earth at speeds close to 17,500 mph. Astronaut Scott Kelly has spent 520 days at the International Space Station, and as a result has aged a little more slowly than his twin brother – and fellow astronaut – Mark Kelly. Scott used to be 6 minutes younger than his twin brother. Now, because Scott was traveling so much faster than Mark and for so many days, he is 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds younger .

Some scientists are exploring other ideas that could theoretically allow time travel. One concept involves wormholes , or hypothetical tunnels in space that could create shortcuts for journeys across the universe. If someone could build a wormhole and then figure out a way to move one end at close to the speed of light – like the hypothetical spaceship mentioned above – the moving end would age more slowly than the stationary end. Someone who entered the moving end and exited the wormhole through the stationary end would come out in their past.

However, wormholes remain theoretical : Scientists have yet to spot one. It also looks like it would be incredibly challenging to send humans through a wormhole space tunnel.

Time travel paradoxes and failed dinner parties

There are also paradoxes associated with time travel. The famous “ grandfather paradox ” is a hypothetical problem that could arise if someone traveled back in time and accidentally prevented their grandparents from meeting. This would create a paradox where you were never born, which raises the question: How could you have traveled back in time in the first place? It’s a mind-boggling puzzle that adds to the mystery of time travel.

Famously, physicist Stephen Hawking tested the possibility of time travel by throwing a dinner party where invitations noting the date, time and coordinates were not sent out until after it had happened. His hope was that his invitation would be read by someone living in the future, who had capabilities to travel back in time. But no one showed up.

As he pointed out : “The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future.”

Telescopes are time machines

Interestingly, astrophysicists armed with powerful telescopes possess a unique form of time travel. As they peer into the vast expanse of the cosmos, they gaze into the past universe. Light from all galaxies and stars takes time to travel, and these beams of light carry information from the distant past. When astrophysicists observe a star or a galaxy through a telescope, they are not seeing it as it is in the present, but as it existed when the light began its journey to Earth millions to billions of years ago.

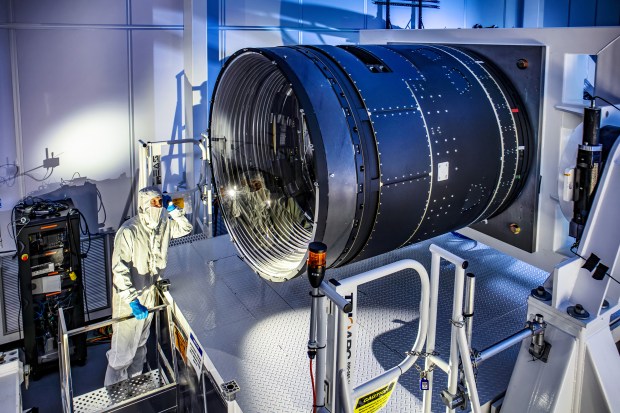

NASA’s newest space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope , is peering at galaxies that were formed at the very beginning of the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago.

While we aren’t likely to have time machines like the ones in movies anytime soon, scientists are actively researching and exploring new ideas. But for now, we’ll have to enjoy the idea of time travel in our favorite books, movies and dreams.

This article first appeared on the Conversation. You can read the original here .

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to [email protected] . Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

The largest digital camera ever made for astronomy is done

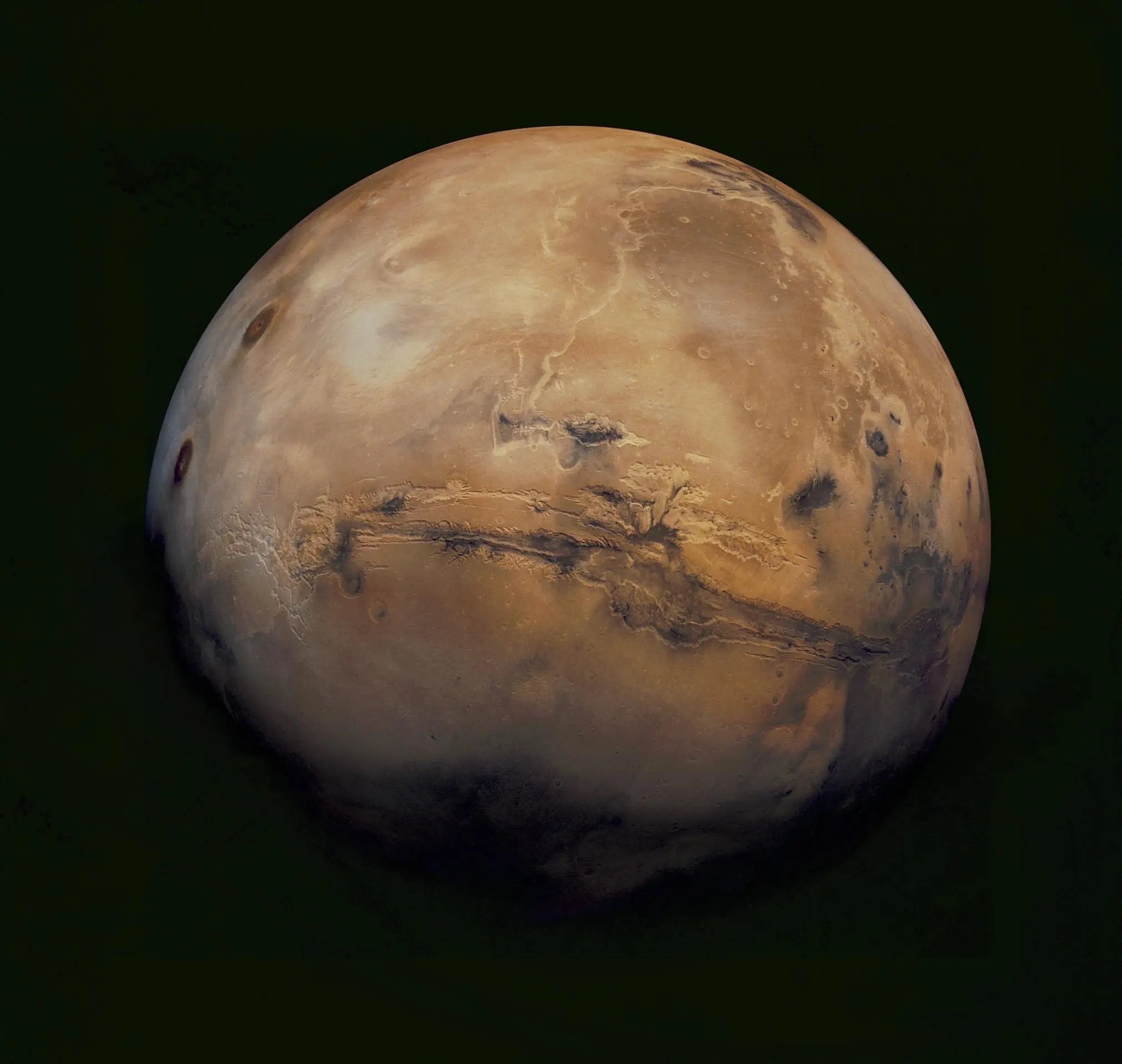

NASA seeks faster, cheaper options to return Mars samples to Earth

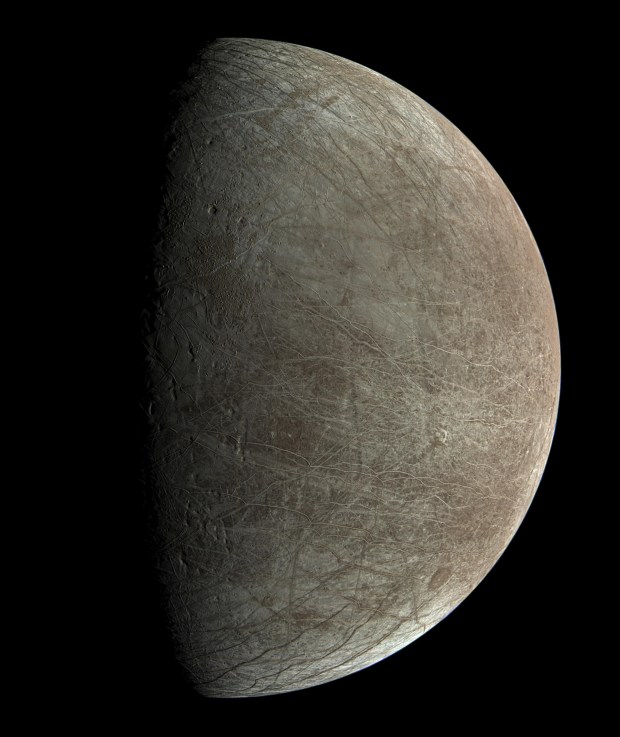

The search is on extraterrestrial life on worlds like Enceladus

Why good science is needed more than ever, and so is good faith

2024 Full Moon calendar: Dates, times, types, and names

How to help astronomers study gamma-ray bursts.

Explore the Virgo galaxy cluster: This Week in Astronomy with Dave Eicher

Circular patterns on Europa suggest how deep a lively ocean may be

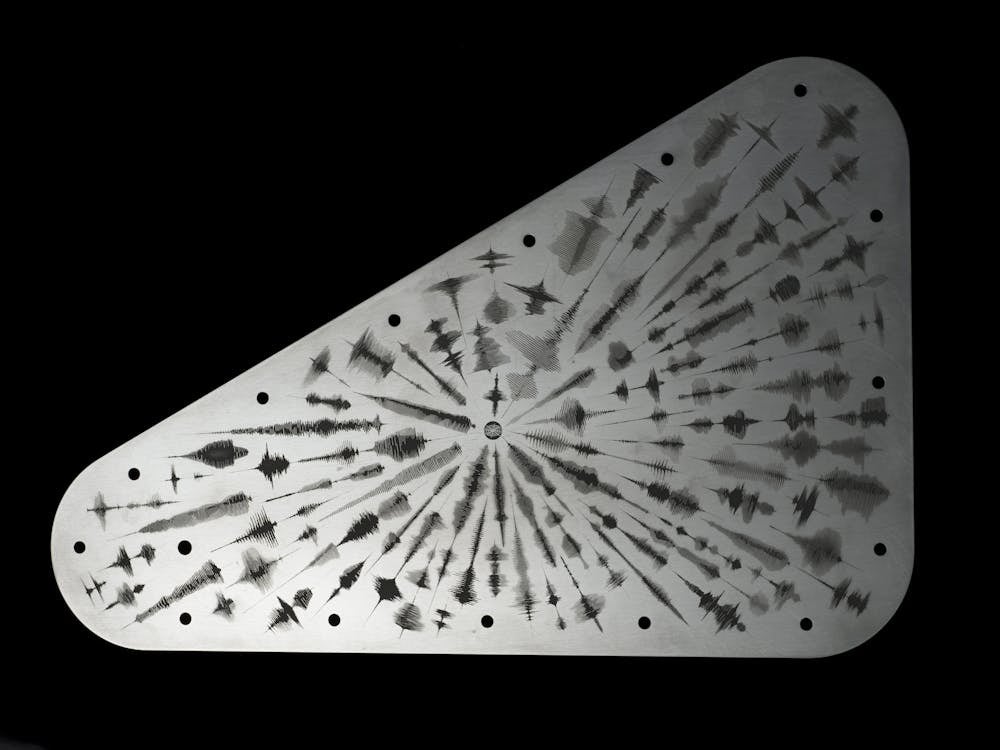

These are the clever messages headed to Jupiter aboard NASA’s Europa Clipper

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible, Researchers Say

Matthew S. Schwartz

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered. Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered.

"The past is obdurate," Stephen King wrote in his book about a man who goes back in time to prevent the Kennedy assassination. "It doesn't want to be changed."

Turns out, King might have been on to something.

Countless science fiction tales have explored the paradox of what would happen if you went back in time and did something in the past that endangered the future. Perhaps one of the most famous pop culture examples is in Back to the Future , when Marty McFly goes back in time and accidentally stops his parents from meeting, putting his own existence in jeopardy.

But maybe McFly wasn't in much danger after all. According a new paper from researchers at the University of Queensland, even if time travel were possible, the paradox couldn't actually exist.

Researchers ran the numbers and determined that even if you made a change in the past, the timeline would essentially self-correct, ensuring that whatever happened to send you back in time would still happen.

"Say you traveled in time in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus," University of Queensland scientist Fabio Costa told the university's news service .

"However, if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place," said Costa, who co-authored the paper with honors undergraduate student Germain Tobar.

"This is a paradox — an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe."

A variation is known as the "grandfather paradox" — in which a time traveler kills their own grandfather, in the process preventing the time traveler's birth.

The logical paradox has given researchers a headache, in part because according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, "closed timelike curves" are possible, theoretically allowing an observer to travel back in time and interact with their past self — potentially endangering their own existence.

But these researchers say that such a paradox wouldn't necessarily exist, because events would adjust themselves.

Take the coronavirus patient zero example. "You might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so, you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Tobar told the university's news service.

In other words, a time traveler could make changes, but the original outcome would still find a way to happen — maybe not the same way it happened in the first timeline but close enough so that the time traveler would still exist and would still be motivated to go back in time.

"No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you," Tobar said.

The paper, "Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice," was published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Classical and Quantum Gravity . The findings seem consistent with another time travel study published this summer in the peer-reviewed journal Physical Review Letters. That study found that changes made in the past won't drastically alter the future.

Bestselling science fiction author Blake Crouch, who has written extensively about time travel, said the new study seems to support what certain time travel tropes have posited all along.

"The universe is deterministic and attempts to alter Past Event X are destined to be the forces which bring Past Event X into being," Crouch told NPR via email. "So the future can affect the past. Or maybe time is just an illusion. But I guess it's cool that the math checks out."

- grandfather paradox

- time travel

Is time travel even possible? An astrophysicist explains the science behind the science fiction

Published: Nov 13, 2023

By: Magazine Editor

Written by Adi Foord , assistant professor of physics , UMBC

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to [email protected] .

Will it ever be possible for time travel to occur? – Alana C., age 12, Queens, New York

Have you ever dreamed of traveling through time, like characters do in science fiction movies? For centuries, the concept of time travel has captivated people’s imaginations. Time travel is the concept of moving between different points in time, just like you move between different places. In movies, you might have seen characters using special machines, magical devices or even hopping into a futuristic car to travel backward or forward in time.

But is this just a fun idea for movies, or could it really happen?

The question of whether time is reversible remains one of the biggest unresolved questions in science. If the universe follows the laws of thermodynamics , it may not be possible. The second law of thermodynamics states that things in the universe can either remain the same or become more disordered over time.

It’s a bit like saying you can’t unscramble eggs once they’ve been cooked. According to this law, the universe can never go back exactly to how it was before. Time can only go forward, like a one-way street.

Time is relative

However, physicist Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity suggests that time passes at different rates for different people. Someone speeding along on a spaceship moving close to the speed of light – 671 million miles per hour! – will experience time slower than a person on Earth.

People have yet to build spaceships that can move at speeds anywhere near as fast as light, but astronauts who visit the International Space Station orbit around the Earth at speeds close to 17,500 mph. Astronaut Scott Kelly has spent 520 days at the International Space Station, and as a result has aged a little more slowly than his twin brother – and fellow astronaut – Mark Kelly. Scott used to be 6 minutes younger than his twin brother. Now, because Scott was traveling so much faster than Mark and for so many days, he is 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds younger .

Some scientists are exploring other ideas that could theoretically allow time travel. One concept involves wormholes , or hypothetical tunnels in space that could create shortcuts for journeys across the universe. If someone could build a wormhole and then figure out a way to move one end at close to the speed of light – like the hypothetical spaceship mentioned above – the moving end would age more slowly than the stationary end. Someone who entered the moving end and exited the wormhole through the stationary end would come out in their past.

However, wormholes remain theoretical: Scientists have yet to spot one. It also looks like it would be incredibly challenging to send humans through a wormhole space tunnel.

Paradoxes and failed dinner parties

There are also paradoxes associated with time travel. The famous “ grandfather paradox ” is a hypothetical problem that could arise if someone traveled back in time and accidentally prevented their grandparents from meeting. This would create a paradox where you were never born, which raises the question: How could you have traveled back in time in the first place? It’s a mind-boggling puzzle that adds to the mystery of time travel.

Famously, physicist Stephen Hawking tested the possibility of time travel by throwing a dinner party where invitations noting the date, time and coordinates were not sent out until after it had happened. His hope was that his invitation would be read by someone living in the future, who had capabilities to travel back in time. But no one showed up.

As he pointed out : “The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future.”

Telescopes are time machines

Interestingly, astrophysicists armed with powerful telescopes possess a unique form of time travel. As they peer into the vast expanse of the cosmos, they gaze into the past universe. Light from all galaxies and stars takes time to travel, and these beams of light carry information from the distant past. When astrophysicists observe a star or a galaxy through a telescope, they are not seeing it as it is in the present, but as it existed when the light began its journey to Earth millions to billions of years ago. https://www.youtube.com/embed/QeRtcJi3V38?wmode=transparent&start=0 Telescopes are a kind of time machine – they let you peer into the past.

NASA’s newest space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope , is peering at galaxies that were formed at the very beginning of the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago.

While we aren’t likely to have time machines like the ones in movies anytime soon, scientists are actively researching and exploring new ideas. But for now, we’ll have to enjoy the idea of time travel in our favorite books, movies and dreams.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article and see more than 250 UMBC articles available in The Conversation.

Tags: CNMS , Physics , The Conversation

Related Posts

- Science & Tech

UMBC partners with American Statistical Association to organize annual African International Conference on Statistics

From thousands to millions to billions to trillions to quadrillions and beyond: Do numbers ever end?

- Campus Life

Stitching it all together, or how Ephraim Ruttenberg ’25 got hooked on math and crochet

Search UMBC Search

- Accreditation

- Consumer Information

- Equal Opportunity

- Privacy PDF Download

- Web Accessibility

Search UMBC.edu

Advertisement

How Time Travel Works

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

From millennium-skipping Victorians to phone booth-hopping time traveler teenagers, the term time travel often summons our most fantastic visions of what it means to move through the fourth dimension. But of course you don't need a time machine or a fancy wormhole to jaunt through the years.

As you've probably noticed, we're all constantly engaged in the act of time travel. At its most basic level, time is the rate of change in the universe -- and like it or not, we are constantly undergoing change. We age, the planets move around the sun, and things fall apart.

We measure the passage of time in seconds, minutes, hours and years, but this doesn't mean time flows at a constant rate. In fact Einstein's theory of relativity determines that time is not universal. Just as the water in a river rushes or slows depending on the size of the channel, time flows at different rates in different places. In other words, time is relative.

But what causes this fluctuation along our one-way trek from the cradle to the grave? It all comes down to the relationship between time and space. Human beings frolic about in the three spatial dimensions of length, width and depth. Time joins the party as that most crucial fourth dimension . Time can't exist without space, and space can't exist without time. The two exist as one: the space time continuum . Any event that occurs in the universe has to involve both space and time.

In this article, we'll look at the real-life, everyday methods of time travel in our universe, as well as some of the more far-fetched methods of dancing through the fourth dimension.

Did you know your GPS devices rely on time-travel calculations to help you navigate around town? It's true! GPS satellite clocks are about 3 8 seconds longer per day than a clock closer to earth due to the gravitational frequency shift. They make up for this discrepancy by using time travel calculations or they could be way off from your current location and time.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Time Travel and Modern Physics

Time travel has been a staple of science fiction. With the advent of general relativity it has been entertained by serious physicists. But, especially in the philosophy literature, there have been arguments that time travel is inherently paradoxical. The most famous paradox is the grandfather paradox: you travel back in time and kill your grandfather, thereby preventing your own existence. To avoid inconsistency some circumstance will have to occur which makes you fail in this attempt to kill your grandfather. Doesn’t this require some implausible constraint on otherwise unrelated circumstances? We examine such worries in the context of modern physics.

1. Paradoxes Lost?

2. topology and constraints, 3. the general possibility of time travel in general relativity, 4. two toy models, 5. slightly more realistic models of time travel, 6. the possibility of time travel redux, 7. even if there are constraints, so what, 8. computational models, 9. quantum mechanics to the rescue, 10. conclusions, other internet resources, related entries.

- Supplement: Remarks and Limitations on the Toy Models

Modern physics strips away many aspects of the manifest image of time. Time as it appears in the equations of classical mechanics has no need for a distinguished present moment, for example. Relativity theory leads to even sharper contrasts. It replaces absolute simultaneity, according to which it is possible to unambiguously determine the time order of distant events, with relative simultaneity: extending an “instant of time” throughout space is not unique, but depends on the state of motion of an observer. More dramatically, in general relativity the mathematical properties of time (or better, of spacetime)—its topology and geometry—depend upon how matter is arranged rather than being fixed once and for all. So physics can be, and indeed has to be, formulated without treating time as a universal, fixed background structure. Since general relativity represents gravity through spacetime geometry, the allowed geometries must be as varied as the ways in which matter can be arranged. Alongside geometrical models used to describe the solar system, black holes, and much else, the scope of variation extends to include some exotic structures unlike anything astrophysicists have observed. In particular, there are spacetime geometries with curves that loop back on themselves: closed timelike curves (CTCs), which describe the possible trajectory of an observer who returns exactly back to their earlier state—without any funny business, such as going faster than the speed of light. These geometries satisfy the relevant physical laws, the equations of general relativity, and in that sense time travel is physically possible.

Yet circular time generates paradoxes, familiar from science fiction stories featuring time travel: [ 1 ]

- Consistency: Kurt plans to murder his own grandfather Adolph, by traveling along a CTC to an appropriate moment in the past. He is an able marksman, and waits until he has a clear shot at grandpa. Normally he would not miss. Yet if he succeeds, there is no way that he will then exist to plan and carry out the mission. Kurt pulls the trigger: what can happen?

- Underdetermination: Suppose that Kurt first travels back in order to give his earlier self a copy of How to Build a Time Machine. This is the same book that allows him to build a time machine, which he then carries with him on his journey to the past. Who wrote the book?

- Easy Knowledge: A fan of classical music enhances their computer with a circuit that exploits a CTC. This machine efficiently solves problems at a higher level of computational complexity than conventional computers, leading (among other things) to finding the smallest circuits that can generate Bach’s oeuvre—and to compose new pieces in the same style. Such easy knowledge is at odds with our understanding of our epistemic predicament. (This third paradox has not drawn as much attention.)

The first two paradoxes were once routinely taken to show that solutions with CTCs should be rejected—with charges varying from violating logic, to being “physically unreasonable”, to undermining the notion of free will. Closer analysis of the paradoxes has largely reversed this consensus. Physicists have discovered many solutions with CTCs and have explored their properties in pursuing foundational questions, such as whether physics is compatible with the idea of objective temporal passage (starting with Gödel 1949). Philosophers have also used time travel scenarios to probe questions about, among other things, causation, modality, free will, and identity (see, e.g., Earman 1972 and Lewis’s seminal 1976 paper).

We begin below with Consistency , turning to the other paradoxes in later sections. A standard, stone-walling response is to insist that the past cannot be changed, as a matter of logic, even by a time traveler (e.g., Gödel 1949, Clarke 1977, Horwich 1987). Adolph cannot both die and survive, as a matter of logic, so any scheme to alter the past must fail. In many of the best time travel fictions, the actions of a time traveler are constrained in novel and unexpected ways. Attempts to change the past fail, and they fail, often tragically, in just such a way that they set the stage for the time traveler’s self-defeating journey. The first question is whether there is an analog of the consistent story when it comes to physics in the presence of CTCs. As we will see, there is a remarkable general argument establishing the existence of consistent solutions. Yet a second question persists: why can’t time-traveling Kurt kill his own grandfather? Doesn’t the necessity of failures to change the past put unusual and unexpected constraints on time travelers, or objects that move along CTCs? The same argument shows that there are in fact no constraints imposed by the existence of CTCs, in some cases. After discussing this line of argument, we will turn to the palatability and further implications of such constraints if they are required, and then turn to the implications of quantum mechanics.

Wheeler and Feynman (1949) were the first to claim that the fact that nature is continuous could be used to argue that causal influences from later events to earlier events, as are made possible by time travel, will not lead to paradox without the need for any constraints. Maudlin (1990) showed how to make their argument precise and more general, and argued that nonetheless it was not completely general.

Imagine the following set-up. We start off having a camera with a black and white film ready to take a picture of whatever comes out of the time machine. An object, in fact a developed film, comes out of the time machine. We photograph it, and develop the film. The developed film is subsequently put in the time machine, and set to come out of the time machine at the time the picture is taken. This surely will create a paradox: the developed film will have the opposite distribution of black, white, and shades of gray, from the object that comes out of the time machine. For developed black and white films (i.e., negatives) have the opposite shades of gray from the objects they are pictures of. But since the object that comes out of the time machine is the developed film itself it we surely have a paradox.

However, it does not take much thought to realize that there is no paradox here. What will happen is that a uniformly gray picture will emerge, which produces a developed film that has exactly the same uniform shade of gray. No matter what the sensitivity of the film is, as long as the dependence of the brightness of the developed film depends in a continuous manner on the brightness of the object being photographed, there will be a shade of gray that, when photographed, will produce exactly the same shade of gray on the developed film. This is the essence of Wheeler and Feynman’s idea. Let us first be a bit more precise and then a bit more general.

For simplicity let us suppose that the film is always a uniform shade of gray (i.e., at any time the shade of gray does not vary by location on the film). The possible shades of gray of the film can then be represented by the (real) numbers from 0, representing pure black, to 1, representing pure white.

Let us now distinguish various stages in the chronological order of the life of the film. In stage \(S_1\) the film is young; it has just been placed in the camera and is ready to be exposed. It is then exposed to the object that comes out of the time machine. (That object in fact is a later stage of the film itself). By the time we come to stage \(S_2\) of the life of the film, it has been developed and is about to enter the time machine. Stage \(S_3\) occurs just after it exits the time machine and just before it is photographed. Stage \(S_4\) occurs after it has been photographed and before it starts fading away. Let us assume that the film starts out in stage \(S_1\) in some uniform shade of gray, and that the only significant change in the shade of gray of the film occurs between stages \(S_1\) and \(S_2\). During that period it acquires a shade of gray that depends on the shade of gray of the object that was photographed. In other words, the shade of gray that the film acquires at stage \(S_2\) depends on the shade of gray it has at stage \(S_3\). The influence of the shade of gray of the film at stage \(S_3\), on the shade of gray of the film at stage \(S_2\), can be represented as a mapping, or function, from the real numbers between 0 and 1 (inclusive), to the real numbers between 0 and 1 (inclusive). Let us suppose that the process of photography is such that if one imagines varying the shade of gray of an object in a smooth, continuous manner then the shade of gray of the developed picture of that object will also vary in a smooth, continuous manner. This implies that the function in question will be a continuous function. Now any continuous function from the real numbers between 0 and 1 (inclusive) to the real numbers between 0 and 1 (inclusive) must map at least one number to itself. One can quickly convince oneself of this by graphing such functions. For one will quickly see that any continuous function \(f\) from \([0,1]\) to \([0,1]\) must intersect the line \(x=y\) somewhere, and thus there must be at least one point \(x\) such that \(f(x)=x\). Such points are called fixed points of the function. Now let us think about what such a fixed point represents. It represents a shade of gray such that, when photographed, it will produce a developed film with exactly that same shade of gray. The existence of such a fixed point implies a solution to the apparent paradox.

Let us now be more general and allow color photography. One can represent each possible color of an object (of uniform color) by the proportions of blue, green and red that make up that color. (This is why television screens can produce all possible colors.) Thus one can represent all possible colors of an object by three points on three orthogonal lines \(x, y\) and \(z\), that is to say, by a point in a three-dimensional cube. This cube is also known as the “Cartesian product” of the three line segments. Now, one can also show that any continuous map from such a cube to itself must have at least one fixed point. So color photography can not be used to create time travel paradoxes either!

Even more generally, consider some system \(P\) which, as in the above example, has the following life. It starts in some state \(S_1\), it interacts with an object that comes out of a time machine (which happens to be its older self), it travels back in time, it interacts with some object (which happens to be its younger self), and finally it grows old and dies. Let us assume that the set of possible states of \(P\) can be represented by a Cartesian product of \(n\) closed intervals of the reals, i.e., let us assume that the topology of the state-space of \(P\) is isomorphic to a finite Cartesian product of closed intervals of the reals. Let us further assume that the development of \(P\) in time, and the dependence of that development on the state of objects that it interacts with, is continuous. Then, by a well-known fixed point theorem in topology (see, e.g., Hocking & Young 1961: 273), no matter what the nature of the interaction is, and no matter what the initial state of the object is, there will be at least one state \(S_3\) of the older system (as it emerges from the time travel machine) that will influence the initial state \(S_1\) of the younger system (when it encounters the older system) so that, as the younger system becomes older, it develops exactly into state \(S_3\). Thus without imposing any constraints on the initial state \(S_1\) of the system \(P\), we have shown that there will always be perfectly ordinary, non-paradoxical, solutions, in which everything that happens, happens according to the usual laws of development. Of course, there is looped causation, hence presumably also looped explanation, but what do you expect if there is looped time?

Unfortunately, for the fan of time travel, a little reflection suggests that there are systems for which the needed fixed point theorem does not hold. Imagine, for instance, that we have a dial that can only rotate in a plane. We are going to put the dial in the time machine. Indeed we have decided that if we see the later stage of the dial come out of the time machine set at angle \(x\), then we will set the dial to \(x+90\), and throw it into the time machine. Now it seems we have a paradox, since the mapping that consists of a rotation of all points in a circular state-space by 90 degrees does not have a fixed point. And why wouldn’t some state-spaces have the topology of a circle?

However, we have so far not used another continuity assumption which is also a reasonable assumption. So far we have only made the following demand: the state the dial is in at stage \(S_2\) must be a continuous function of the state of the dial at stage \(S_3\). But, the state of the dial at stage \(S_2\) is arrived at by taking the state of the dial at stage \(S_1\), and rotating it over some angle. It is not merely the case that the effect of the interaction, namely the state of the dial at stage \(S_2\), should be a continuous function of the cause, namely the state of the dial at stage \(S_3\). It is additionally the case that path taken to get there, the way the dial is rotated between stages \(S_1\) and \(S_2\) must be a continuous function of the state at stage \(S_3\). And, rather surprisingly, it turns out that this can not be done. Let us illustrate what the problem is before going to a more general demonstration that there must be a fixed point solution in the dial case.

Forget time travel for the moment. Suppose that you and I each have a watch with a single dial neither of which is running. My watch is set at 12. You are going to announce what your watch is set at. My task is going to be to adjust my watch to yours no matter what announcement you make. And my actions should have a continuous (single valued) dependence on the time that you announce. Surprisingly, this is not possible! For instance, suppose that if you announce “12”, then I achieve that setting on my watch by doing nothing. Now imagine slowly and continuously increasing the announced times, starting at 12. By continuity, I must achieve each of those settings by rotating my dial to the right. If at some point I switch and achieve the announced goal by a rotation of my dial to the left, I will have introduced a discontinuity in my actions, a discontinuity in the actions that I take as a function of the announced angle. So I will be forced, by continuity, to achieve every announcement by rotating the dial to the right. But, this rotation to the right will have to be abruptly discontinued as the announcements grow larger and I eventually approach 12 again, since I achieved 12 by not rotating the dial at all. So, there will be a discontinuity at 12 at the latest. In general, continuity of my actions as a function of announced times can not be maintained throughout if I am to be able to replicate all possible settings. Another way to see the problem is that one can similarly reason that, as one starts with 12, and imagines continuously making the announced times earlier, one will be forced, by continuity, to achieve the announced times by rotating the dial to the left. But the conclusions drawn from the assumption of continuous increases and the assumption of continuous decreases are inconsistent. So we have an inconsistency following from the assumption of continuity and the assumption that I always manage to set my watch to your watch. So, a dial developing according to a continuous dynamics from a given initial state, can not be set up so as to react to a second dial, with which it interacts, in such a way that it is guaranteed to always end up set at the same angle as the second dial. Similarly, it can not be set up so that it is guaranteed to always end up set at 90 degrees to the setting of the second dial. All of this has nothing to do with time travel. However, the impossibility of such set ups is what prevents us from enacting the rotation by 90 degrees that would create paradox in the time travel setting.

Let us now give the positive result that with such dials there will always be fixed point solutions, as long as the dynamics is continuous. Let us call the state of the dial before it interacts with its older self the initial state of the dial. And let us call the state of the dial after it emerges from the time machine the final state of the dial. There is also an intermediate state of the dial, after it interacts with its older self and before it is put into the time machine. We can represent the initial or intermediate states of the dial, before it goes into the time machine, as an angle \(x\) in the horizontal plane and the final state of the dial, after it comes out of the time machine, as an angle \(y\) in the vertical plane. All possible \(\langle x,y\rangle\) pairs can thus be visualized as a torus with each \(x\) value picking out a vertical circular cross-section and each \(y\) picking out a point on that cross-section. See figure 1 .

Figure 1 [An extended description of figure 1 is in the supplement.]

Suppose that the dial starts at angle \(i\) which picks out vertical circle \(I\) on the torus. The initial angle \(i\) that the dial is at before it encounters its older self, and the set of all possible final angles that the dial can have when it emerges from the time machine is represented by the circle \(I\) on the torus (see figure 1 ). Given any possible angle of the emerging dial, the dial initially at angle \(i\) will develop to some other angle. One can picture this development by rotating each point on \(I\) in the horizontal direction by the relevant amount. Since the rotation has to depend continuously on the angle of the emerging dial, circle \(I\) during this development will deform into some loop \(L\) on the torus. Loop \(L\) thus represents all possible intermediate angles \(x\) that the dial is at when it is thrown into the time machine, given that it started at angle \(i\) and then encountered a dial (its older self) which was at angle \(y\) when it emerged from the time machine. We therefore have consistency if \(x=y\) for some \(x\) and \(y\) on loop \(L\). Now, let loop \(C\) be the loop which consists of all the points on the torus for which \(x=y\). Ring \(I\) intersects \(C\) at point \(\langle i,i\rangle\). Obviously any continuous deformation of \(I\) must still intersect \(C\) somewhere. So \(L\) must intersect \(C\) somewhere, say at \(\langle j,j\rangle\). But that means that no matter how the development of the dial starting at \(I\) depends on the angle of the emerging dial, there will be some angle for the emerging dial such that the dial will develop exactly into that angle (by the time it enters the time machine) under the influence of that emerging dial. This is so no matter what angle one starts with, and no matter how the development depends on the angle of the emerging dial. Thus even for a circular state-space there are no constraints needed other than continuity.

Unfortunately there are state-spaces that escape even this argument. Consider for instance a pointer that can be set to all values between 0 and 1, where 0 and 1 are not possible values. That is, suppose that we have a state-space that is isomorphic to an open set of real numbers. Now suppose that we have a machine that sets the pointer to half the value that the pointer is set at when it emerges from the time machine.

Figure 2 [An extended description of figure 2 is in the supplement.]

Suppose the pointer starts at value \(I\). As before we can represent the combination of this initial position and all possible final positions by the line \(I\). Under the influence of the pointer coming out of the time machine the pointer value will develop to a value that equals half the value of the final value that it encountered. We can represent this development as the continuous deformation of line \(I\) into line \(L\), which is indicated by the arrows in figure 2 . This development is fully continuous. Points \(\langle x,y\rangle\) on line \(I\) represent the initial position \(x=I\) of the (young) pointer, and the position \(y\) of the older pointer as it emerges from the time machine. Points \(\langle x,y\rangle\) on line \(L\) represent the position \(x\) that the younger pointer should develop into, given that it encountered the older pointer emerging from the time machine set at position \(y\). Since the pointer is designed to develop to half the value of the pointer that it encounters, the line \(L\) corresponds to \(x=1/2 y\). We have consistency if there is some point such that it develops into that point, if it encounters that point. Thus, we have consistency if there is some point \(\langle x,y\rangle\) on line \(L\) such that \(x=y\). However, there is no such point: lines \(L\) and \(C\) do not intersect. Thus there is no consistent solution, despite the fact that the dynamics is fully continuous.

Of course if 0 were a possible value, \(L\) and \(C\) would intersect at 0. This is surprising and strange: adding one point to the set of possible values of a quantity here makes the difference between paradox and peace. One might be tempted to just add the extra point to the state-space in order to avoid problems. After all, one might say, surely no measurements could ever tell us whether the set of possible values includes that exact point or not. Unfortunately there can be good theoretical reasons for supposing that some quantity has a state-space that is open: the set of all possible speeds of massive objects in special relativity surely is an open set, since it includes all speeds up to, but not including, the speed of light. Quantities that have possible values that are not bounded also lead to counter examples to the presented fixed point argument. And it is not obvious to us why one should exclude such possibilities. So the argument that no constraints are needed is not fully general.

An interesting question of course is: exactly for which state-spaces must there be such fixed points? The arguments above depend on a well-known fixed point theorem (due to Schauder) that guarantees the existence of a fixed point for compact, convex state spaces. We do not know what subsequent extensions of this result imply regarding fixed points for a wider variety of systems, or whether there are other general results along these lines. (See Kutach 2003 for more on this issue.)