The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey

Spencer wells.

240 pages, Paperback

First published October 31, 2002

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

Author: Aldo Matteucci

The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey

Where did mankind come from originally, how did it spread across the continents, and when did this take place? This question has fascinated us since – upon observing mankind’s ‘racial diversity’ – we started disbelieving our parochial foundation myths. At first, the occasional old bone and scattered artefact was our only guide to answering these questions. Anthropology followed by re-tracing the evolution of cultures over time. Then came linguistics – suggesting a way back from today’s cacophony of languages to a likely Ur-language the human ape first spoke. Now genetics has joined them in the fray and delivered novel answers. Each of these disciplines throws up conjectures that the others verify independently – we make ‘pre-dictions’ to be tested in the field. When the results turn out to be positive, we feel more confirmed in our way of thinking.

How can genetics contribute to mankind’s history? Dante’s manuscript of the Divina Commedia is lost. We have about 600 handwritten copies. How do we know which is the closest to the original – hence more ‘genuine’? Look for copying mistakes is an answer. If a number of manuscripts share the same mistake, they are more likely to have been copied from each other than from anyone of the rest. We can skilfully establish a sort of genealogy of mistakes, and thanks to this strange tree, the genealogy of the manuscripts. Of course this is not ‘experimental’ proof (two copiers could have made the same mistake independently, or the error may have been corrected): just the application of Ockham’s razor – the principle of parsimony. The simplest explanation is the most likely, says this principle: natura non facit saltum.

Every man and woman carries within himself a manuscript, the genetic code. Over the years small copying errors occur, about thirty in each generation, which are mostly harmless to the individual but mark the passage of time. If the population is small and mates locally, it takes only a few generations before drastic gene frequency changes may occur – the individual’s marker spreads throughout his group and identifies it. If we are skilful, we can identify these groups and, through DNA analysis of the descendants, track their meanderings around the world. Recent advances in technology allow us to do this fast and reliably.

The concept of race never enters the methodology. For, firstly we would like to revert to the races’ origins – the initial ‘soup’ frown which they ‘emerged’. Secondly, upon closer statistical analysis of our genes the concept of ‘race’ proves to be empty: in humans about 85% of all genetic variation is found within the race, and only 8% between the races.

The main problem is that sex blurs the genetic variation picture quickly through recombination, so the markers diffuse rapidly and loose the function we would like to assign to them. We need markers that remain stable over time – untouched by sex. We have markers (polymorphisms) on the man’s Y chromosome, which is transmitted unchanged from father to son. On the female side we have markers in the mitochondria, the small enclosures in the cells that produce energy. This genetic material (mtDNA) is transmitted untouched from mother to offspring in the egg material that surrounds our chromosomes. Clever collection of these ‘virgin’ strands of genetic material from the descendants allows us to follow our foremothers and -fathers on their worldwide migration.

The markers on the Y-chromosome allow us to go back about 60,000 years – after that the signal is blurred. The female M-marker takes us back to about 150,000. So what’s the likely story on our last 60,000 years?

All disciplines concur: Homo sapiens sapiens emerged about 60,000 years ago in Africa. What made the difference? Probably it was the acquisition of language and its associated symbolic perception of the world. Efficient tools, art, and the better use of food resources were the result. Social organisation deepened. Together with natural curiosity climatic change became the driver of expansion at this point.

If Africa was our cradle, Australia was the continent humans settled first – so the genetic markers tell us. How did we get there? Humans simply walked the beaches, exploiting food from both sea and land As the ice age advanced and water became locked in the ice caps, the sea level dropped by over 100m and the exposed swaths of continental shelf brought islands and continents in view of each other and within easy reach of makeshift rafts. Any archaeological trace of this passage would have been subsequently submerged, but for a genetic marker found along the coast of Southern India.

50,000 years ago humans started moving into the Middle East. From there they took the ‘Steppe Highway’ into central Asia and became identified by new genetic markers as Eurasians. They split into two groups, one moving to the north of the Hindu Kush, the other to the south into the Indian subcontinent. Those that went north moved into central Asia – Mongolia and Siberia – as they followed the steppe antelopes only to switch to the bigger game to be found in colder climate (mammoth). Again a split took place, with some groups continuing eastward and others dropping south towards China and Southeast Asia, while others detoured through southern Siberia before descending towards Korea, Japan and China. Genetically, even today northern and southern Chinese are clearly distinct.

And what about the Europeans? Surprisingly, they did not move northwest from the Levant, but circled back from central Asia into Europe, where they became the Cro-Magnons and probably drove the Neanderthals to extinction by excluding them from their food resources – it takes only a reduction in fertility or an increase in mortality of 1 percent to wipe out a small population within 1,000 years. Agriculture as technology on the other hand did indeed move from the Levant directly into Europe – this is what the genes tell us – but not people: 80% of the European gene pool does not come from the Middle East.

Alaska became accessible to a few humans from the eastern Siberian clans (probably less than 500) once the Bering Strait dried up. About 15-12,000 years ago the ice that covered much of the north American continent began to melt, and a passage opened, through which these tiny populations of Siberian hunters expanded south, reaching the tip of South America within 1,000 years. There was another wave of migrants, though, coming up from Southeast Asia, that settled in the American southwest. They speak the Na-Dene languages, which linguistically is a distant cousin of Sino-Tibetan. Linguistics and genetics match.

Despite its rather technical nature the book reads like a mystery novel as it brings up concordant strands of evidence from the different disciplines. Increasingly, the reality matches our ‘pre-dictions’, and we can feel the bog of myth and speculation recede as the scientific ground becomes more solid under our feet.

The book ends on a poignantly pessimistic note. Globalisation has increased mobility. Soon the thorough mixing of the genes, languages and cultures will erase the story of our past. In Federico Fellini’s Roma, the engineers excavating the underground suddenly get a glimpse of rooms that had been remained hermetically sealed for centuries. As they stand in awe before the beauty of the paintings on the walls the air rushing through the opening eats away at the colours and turns everything to grey dust. We are lucky that science has developed methods to record our history before it is thoroughly erased, and that scientists trained these tools on the problem in the nick of time. Spencer Wells, together with many others before him, deserves our gratitude for their deep curiosity.

Review by Aldo Matteucci

You may also be interested in

Engagement: Public Diplomacy in a Globalised World

We need a public diplomacy which fits our time. The policy issues which confront us are increasingly global. Systematic engagement with publics both at home and abroad will be required if we are to identify and implement solutions. Policy-makers and diplomats must work with a wider range of constituencies beyond government, moving towards a more open, inclusive style of policy-making and implementation. Understanding of complexity, difference, networks and cultural heritage will be needed, alongside more imaginative use of technology. Engagement, conducted with energy, ambition and cre...

The Clash of Globalizations: Essays on the Political Economy of Trade and Development Policy

The Clash of Globalizations: Essays on the Political Economy of Trade and Development Policy explores the tensions between different approaches to globalization, examining how they impact trade and development policy.

Contemporary Diplomacy: Representation and Communication in a Globalized World

The message discusses how diplomacy has evolved in the present globalized world, focusing on representation and communication.

The post-modern state and the world order

1989 marked a break in European history. What happened in 1989 went beyond the events of 1789, 1815 or 1919. These dates, like 1989, stand for revolutions, the break-up of empires and the re-ordering of spheres of influence. But these changes took place within the established framework of the balance of power and the sovereign independent state. 1989 was different. In addition to the dramatic changes of that year – the revolutions and the re-ordering of alliances – it marked an underlying change in the European state system itself. To put it crudely, what happened in 1989 was not jus...

Diplomacy of tomorrow

The time of diplomacy is far from over. This paper discusses how its role will become ever more central as most important affairs will have to be handled at global, regional and sub-regional levels.

If God ever gave mankind a mission – it was not so much to multiply as to walk. And walk we did, to the farthest corners of the earth. Homo sapiens sapiens is the only mammal to have spread from its place of origin, Africa, to every other continent – before settling down to sedentary life ogling a TV screen or monitor, that is.

Globalism and the New Regionalism

The text discusses the impact of globalism on the new regionalism trend, emphasizing how regions are increasingly important economically, politically, and culturally in the global landscape. The author explores how global interconnectedness has led to a rise in regional cooperation and integration as a response to globalization, highlighting the various ways in which regions are shaping international relations and global governance.

The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century

One mark of a great book is that it makes you see things in a new way, and Mr. Friedman certainly succeeds in that goal," the Nobel laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz wrote in The New York Times reviewing The World Is Flat in 2005. In this new edition, Thomas L. Friedman includes fresh stories and insights to help us understand the flattening of the world. Weaving new information into his overall thesis, and answering the questions he has been most frequently asked by parents across the country, this third edition also includes two new chapters--on how to be a political activist and social entreprene...

Negotiating Public Health in a Globalized World: Global Health Diplomacy in Action

The message is about the challenges and opportunities of negotiating in the global health diplomacy landscape, emphasizing the importance of collaboration and innovation to address public health issues on a global scale.

Small Economies in the Face of Globalisation

The message discusses the challenges faced by small economies in the era of globalization, highlighting the need for strategies to navigate and thrive in this interconnected world.

Globalization and Governance: Essays on the Challenges for Small States

The message is about the challenges faced by small states in the context of globalization and governance.

How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance

The book "How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance" presents a blueprint for solving global problems by leveraging networks of individuals and organizations. It explores the potential for a new era of collaboration and innovation to address pressing issues on a global scale, highlighting the power of interconnectedness and collective action in shaping a better future for all.

Diplomacy and Global Governance: The Diplomatic Service in an Age of Worldwide Interdependence

The message discusses the role of the diplomatic service in a time of global interdependence. Diplomacy plays a crucial role in ensuring cooperation and effective governance on a global scale, emphasizing the need for diplomatic efforts in maintaining peace and fostering international relations.

Diplo: Effective and inclusive diplomacy

Diplo is a non-profit foundation established by the governments of Malta and Switzerland. Diplo works to increase the role of small and developing states, and to improve global governance and international policy development.

Diplo on Social

Want to stay up to date.

Subscribe to more Diplo and Geneva Internet Platform newsletters!

Suggestions

- An Inspector Calls

- Don Quixote

- Heart of Darkness

- The Book Thief

- The Taming of the Shrew

Please wait while we process your payment

Reset Password

Your password reset email should arrive shortly..

If you don't see it, please check your spam folder. Sometimes it can end up there.

Something went wrong

Log in or create account.

- Be between 8-15 characters.

- Contain at least one capital letter.

- Contain at least one number.

- Be different from your email address.

By signing up you agree to our terms and privacy policy .

Don’t have an account? Subscribe now

Create Your Account

Sign up for your FREE 7-day trial

- Ad-free experience

- Note-taking

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AP® English Test Prep

- Plus much more

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Already have an account? Log in

Choose Your Plan

Group Discount

$4.99 /month + tax

$24.99 /year + tax

Save over 50% with a SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan!

Purchasing SparkNotes PLUS for a group?

Get Annual Plans at a discount when you buy 2 or more!

$24.99 $18.74 / subscription + tax

Subtotal $37.48 + tax

Save 25% on 2-49 accounts

Save 30% on 50-99 accounts

Want 100 or more? Contact us for a customized plan.

Payment Details

Payment Summary

SparkNotes Plus

Change

You'll be billed after your free trial ends.

7-Day Free Trial

Not Applicable

Renews April 27, 2024 April 20, 2024

Discounts (applied to next billing)

SNPLUSROCKS20 | 20% Discount

This is not a valid promo code.

Discount Code (one code per order)

SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan - Group Discount

SparkNotes Plus subscription is $4.99/month or $24.99/year as selected above. The free trial period is the first 7 days of your subscription. TO CANCEL YOUR SUBSCRIPTION AND AVOID BEING CHARGED, YOU MUST CANCEL BEFORE THE END OF THE FREE TRIAL PERIOD. You may cancel your subscription on your Subscription and Billing page or contact Customer Support at [email protected] . Your subscription will continue automatically once the free trial period is over. Free trial is available to new customers only.

For the next 7 days, you'll have access to awesome PLUS stuff like AP English test prep, No Fear Shakespeare translations and audio, a note-taking tool, personalized dashboard, & much more!

You’ve successfully purchased a group discount. Your group members can use the joining link below to redeem their group membership. You'll also receive an email with the link.

Members will be prompted to log in or create an account to redeem their group membership.

Thanks for creating a SparkNotes account! Continue to start your free trial.

We're sorry, we could not create your account. SparkNotes PLUS is not available in your country. See what countries we’re in.

There was an error creating your account. Please check your payment details and try again.

Your PLUS subscription has expired

- We’d love to have you back! Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Go ad-free AND get instant access to grade-boosting study tools!

- Start the school year strong with SparkNotes PLUS!

- Start the school year strong with PLUS!

The Odyssey

- Study Guide

- Mastery Quizzes

- Infographic

Unlock your FREE SparkNotes PLUS trial!

Unlock your free trial.

- Ad-Free experience

- Easy-to-access study notes

- AP® English test prep

Questions & Answers

Why does Telemachus go to Pylos and Sparta?

The goddess Athena, disguised as Mentes, advises Telemachus to visit Pylos and Sparta. Athena tells Telemachus that he might hear news of his father, Odysseus. If he doesn’t hear that Odysseus is still alive, Telemachus will know it is time to hold a funeral and assert his status as master of Odysseus’s house and property. The journey is potentially dangerous. By undertaking the journey, Telemachus shows that he has inherited his father’s courage, and he begins to forge a reputation in his society as a brave and adventurous man. His visits to Nestor and Menelaus require him to tactfully observe the social rules that bind travelers and guests. This introduces one of The Odyssey ’s central themes: hospitality and the rules that govern it. Nestor and Menelaus tell Telemachus stories about Odysseus’s achievements in the Trojan War. Menelaus affirms that Telemachus is a worthy son of his famous father: “Good blood runs in you, dear boy.” Menelaus also tells him that his father is alive. This encouragement inspires Telemachus, and his experiences as a traveler help him to mature. When he returns to Ithaca, he is ready to help Odysseus defeat the suitors.

How does Odysseus escape Polyphemus?

The cyclops Polyphemus traps Odysseus and his men in a cave, behind an enormous rock. Only the cyclops is strong enough to move the rock, so Odysseus can’t escape. Instead, Odysseus hatches a plan. While the cyclops is out with his sheep, Odysseus sharpens a piece of wood into a stake and hardens it in the fire. Next, he gives the cyclops wine to get him drunk, and he tells the cyclops his name is “Nobody.” When the cyclops falls asleep, Odysseus blinds him with the hardened stake. Polyphemus’ screams summon the other cyclops, but when he shouts “Nobody’s killing me!” they go away again. In the morning, the cyclops must let his sheep out to graze. He feels the sheep as they leave, to make sure his prisoners aren’t escaping too, but Odysseus and his men are clinging to the sheep’s bellies. Odysseus’s escape from Polyphemus demonstrates his main character trait: a gift for tactics and trickery. It’s significant that Odysseus’s stratagem requires him to conceal his reputation and identify himself as “Nobody.” The Odyssey explores the nature of identity and the tension between a person’s reputation in the world and who he is in his inner life.

Why doesn’t the goddess Athena get Odysseus home sooner?

The goddess Athena is Odysseus’s patron. She is the goddess of craft and wisdom, so she is fond of the cunning Odysseus: “among mortal men / you’re far the best at tactics, spinning yarns, / and I am famous among the gods for wisdom, / cunning wiles, too.” Athena uses her divine powers to protect Odysseus and to help him get home. However, the god Poseidon is Odysseus’s sworn enemy, because Odysseus blinded his son, Polyphemus the cyclops. Poseidon is more powerful than Athena, and he has a higher rank amongst the gods. He does everything he can to prevent Odysseus from returning home. The action of The Odyssey begins when Athena sees her chance to rescue Odysseus from the nymph Calypso while Poseidon’s back is turned. Odysseus’s fate ultimately depends on the status of his patron goddess, suggesting that hierarchy is inescapable in the universe of The Odyssey .

Why does Odysseus kill the suitors?

Odysseus wants revenge on the suitors. They have wasted a lot of his wealth, by living at his expense during his absence. More importantly, by taking advantage of his absence, the suitors have insulted Odysseus and damaged his reputation. Odysseus lives by the heroic code of kleos , or fame, which values reputation above everything else. Odysseus is proud of his reputation: “My fame has reached the skies.” He cannot allow the suitors’ insult to his reputation to go unpunished. The suitors make things worse for themselves by mistreating Odysseus when he arrives at his palace disguised as a beggar. In the world of The Odyssey , hosts have an obligation to treat their guests well. Whenever he can, Odysseus punishes hosts who break this rule.

How does Penelope test Odysseus?

Penelope has not seen her husband for many years. When Odysseus returns, Penelope doesn’t recognize him and cannot be sure that Odysseus is really who he says he is. She tests Odysseus by ordering her servant Eurycleia to move their marriage bed. Odysseus gets angry. He explains that he built their bedroom around an ancient olive tree, and used the top of the tree to make their bedpost. He is angry because he believes Penelope must have replaced this bed with a movable one. His anger, and the fact that he knows the story of the bed, proves his identity. Only Odysseus, Penelope, and one loyal servant have ever seen the bed. Penelope’s determination to test Odysseus shows that she is intelligent and not easily tricked. In this way, she is very like Odysseus. Penelope’s test reminds us that the two characters are soulmates. Their marriage bed, literally rooted in the soil of Ithaca, is a powerful symbol of the permanence of home in a world where nothing else seems dependable.

What is happening at the beginning of The Odyssey ?

The Odyssey begins with the invocation of the muse, which is a distinct literary characteristic typical of epic poetry. The first line of the text, “Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns,” invokes one of the nine muses, or goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. The poet begins his recitation by calling upon the muse for inspiration in telling Odysseus’s story.

Why does Athena help Odysseus so much?

Athena helps Odysseus for several reasons. Odysseus is Poseidon’s enemy, having blinded Poseidon’s Cyclops son, Polyphemus, and Athena and Poseidon share a mutual grudge stemming from when they both vied to become the patron saint of Athens. Further, Athena sided with the Greeks during the Trojan War, and Odysseus is a Greek hero. Lastly and perhaps most importantly, Athena has genuine respect and affection for Odysseus. For instance, in her first speech of the poem, she states that her “heart breaks for Odysseus,” and later Nestor recalls how much she “lavished care on brave Odysseus, years ago in the land of Troy.”

Why does Nestor invite Telemachus to the feast before knowing his identity?

By inviting Telemachus to the feast without knowing who he is, Nestor demonstrates the ancient Greek custom of hospitality known as xenia . This custom dictates that hosts and guests must show mutual respect toward one another, which includes offering food, drink, gifts, and shelter even before the host knows a person’s identity. Only after Telemachus has been provided food and drink does Nestor question the young man: “Now’s the time, now they’ve enjoyed their meal, / to probe our guests and find out who they are. / Strangers—friends, who are you?” Homer emphasizes these rituals throughout the poem whenever proper hosts meet strangers.

Why does Calypso allow Odysseus to leave her island?

Calypso allows Odysseus to leave her island because she understands that, despite Odysseus sleeping with her, his heart longs for his wife and home. At Athena’s request, Zeus orders Hermes to deliver orders to Calypso stating that “the exile must return.” Zeus even makes Calypso help Odysseus construct a raft to sail home. While Calypso is bitter, pointing out that the gods are “scandalized when goddesses sleep with mortals,” she has no choice but to obey Zeus’s commands. Five days after Hermes’s visit, Odysseus leaves Calypso’s island.

Why does Odysseus sleep with Circe?

When Odysseus fails to transform into a pig after drinking Circe’s potion, Circe realizes he must be the famed “man of twists and turns” and invites him into her bed. Odysseus refuses unless she meets his conditions: Circe must turn his men whom she earlier transformed into pigs back into humans, and she must promise never to use her magic to harm him. Once they strike a bargain, Odysseus sleeps with Circe. Odysseus and his men stay on her island for a year, and Odysseus only asks to leave when his men demand it. Such behavior implies that Odysseus has grown to care for Circe even though his “heart longs to be home.”

Why does Odysseus travel to Hades?

When Odysseus approaches Circe to ask for help returning home, she tells him that he must first travel to Hades to speak with the ghost of the blind prophet Tiresias. She explains that Tiresias “will tell you the way to go, the stages of your voyage, / how you can cross the swarming sea and reach home at last.” Eager to return to his home and family in Ithaca, Odysseus follows Circe’s detailed instructions to reach Hades, where the souls of the dead dwell. Tiresias provides Odysseus with important information, confirms that Odysseus will reach home to his loyal wife, and foretells of Odysseus’s slaughter of the suitors.

Why does Odysseus fail to reveal his identity to Penelope when they are first reunited?

Having been away from home for twenty years, Odyssey doesn’t immediately reveal his identity to Penelope because he needs to ensure that he can trust her and that she remains loyal to him. Suitors fill his palace, and though Penelope seems to care only for her husband, Odysseus has experienced enough treachery along his journey to know that she could be covering up deceit. While he doesn’t immediately tell her who he is, he does divulge to her, “I am a man who’s had his share of sorrows,” indicating that he wants to protect himself from pain.

Does Penelope really intend to marry one of her suitors?

In Book 19, Penelope declares her intention to remarry. She tells Odysseus, when he is disguised as a beggar, that she can no longer avoid it: Her parents are pressuring her, and Telemachus is “galled as [the suitors] squander his estate.” To determine which man she will marry, she devises a contest: Whoever can string Odysseus’s old bow and shoot an arrow through the twelve axes will win her hand. Eurymachus, the first suitor, can’t even string the bow, let alone shoot it. This fact hints that Penelope, despite her words, may know that shooting the bow cleanly is a near impossible task, a detail that would allow her to avoid choosing a new husband after all.

How do Odysseus and Telemachus defeat the suitors?

Odysseus and Telemachus face great odds when they take on the 108 suitors vying for Penelope’s hand at the palace. While Odysseus and Telemachus only have Eumaeus and a servant on their side, they also have a hidden weapon in Athena, disguised as Mentor, who joins them after the fight breaks out. Athena uses words to inspire Odysseus to tap into his ultimate courage and strength, taunting, “Where’s it gone, Odysseus—your power, your fighting heart? . . . How can you . . . bewail the loss of your combat strength in a war with suitors ,” and she uses her powers to divert the suitors’ arrows from their mark. Athena only physically engages in the battle once Odysseus and Telemachus have proven their worthiness by fighting with determination. Once Athena enters the battle, armed with her “man-destroying shield of thunder,” the terrified suitors stop fighting and scatter, allowing Odysseus and his men to ruthlessly slaughter them.

Would Odysseus have survived without Athena’s help?

While Odysseus may have survived without Athena’s help, the goddess does save him numerous times, and she aids him almost constantly. For example, she surrounds him with a mist that allows him to move through hostile crowds, she makes him look more attractive to appeal to people who can help him, and she actively protects him from the suitors’ arrows. At the same time, if Athena had left Odysseus on Calypso’s island, he would not have faced so many dangerous situations. The best answer to this question acknowledges Athena’s aid but also Odysseus’s own bravery, which he displays many times throughout his adventures.

The Odyssey SparkNotes Literature Guide

Ace your assignments with our guide to The Odyssey !

Popular pages: The Odyssey

Full poem analysis summary, character list characters, odysseus characters, themes literary devices, homecoming quotes, full play quick quizzes, central idea essay: what makes odysseus “the man of twists and turns" essays, take a study break.

Every Literary Reference Found in Taylor Swift's Lyrics

The 7 Most Messed-Up Short Stories We All Had to Read in School

QUIZ: Which Greek God Are You?

Answer These 7 Questions and We'll Tell You How You'll Do on Your AP Exams

Global Human Journey

An animated map shows humans migrating out of Africa to Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

Anthropology, Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, World History

Loading ...

The video above is from the January 2013 iPad edition of National Geographic magazine.

Groups of modern humans— Homo sapiens —began their migration out of Africa some 60,000 years ago. Some of our early ancestors kept exploring until they spread to all corners of Earth. How far and fast they went depended on climate , the pressures of population , and the invention of boats and other technologies. Less tangible qualities also sped their footsteps: imagination, adaptability, and an innate curiosity about what lay over the next hill.

Today, geneticists are doing their own exploring. Their studies have led them to a gene variation that might point to our propensity for risk-taking, movement, change, and adventure. This gene variant, known as DRD4-7R, is carried by approximately 20 percent of the human population . Several studies tie 7R (and other variants of the DRD4 gene ) to migration . ( Genetics is complex, however. Different groups of genes interact and yield diverse results in different individuals. DRD4-7R probably influences, not causes, our tendency toward “restlessness.”)

Teaching Strategies

Review “The Global Human Journey” video, then discuss geography and genetics as posed by queries in the “Questions” tab.

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Page Producer

In partnership with, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

From the Journal of a Disappointed Man Summary & Analysis by Andrew Motion

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

"From the Journal of a Disappointed Man" appears in Andrew Motion's 2009 collection The Mower: New and Selected Poems . The poem describes this man's observations of an ill-fated construction job, during which a work crew tries to drive a pile (support column) into a pier. The crew encounters a mysterious problem, gives up on solving it, and abandons the job. Much as the crew leaves the pile hanging "in mid-air," the incident leaves the speaker hanging—and the poem leaves readers hanging, demonstrating how real life often denies us the tidy resolutions we seek.

- Read the full text of “From the Journal of a Disappointed Man”

The Full Text of “From the Journal of a Disappointed Man”

“from the journal of a disappointed man” summary, “from the journal of a disappointed man” themes.

Disappointment, Uncertainty, and Failure

Labor and Social Class

Masculinity and Social Expectations

- Lines 37-44

Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis of “From the Journal of a Disappointed Man”

I discovered these ... ... long wire hawser.

Everything else was ... ... tight": all monosyllables.

Lines 12-16

Nevertheless, by paying ... ... a great difficulty.

Lines 17-20

I cannot say ... ... the whole business.

Lines 21-24

The man nearest ... ... crack of Doom.

Lines 25-28

I should say ... ... and finally ceased.

Lines 29-32

One massive man ... ... what they saw;

Lines 33-38

though one fellow ... ... relieve the tension.

Lines 39-44

Afterwards, and with ... ... me of course.

“From the Journal of a Disappointed Man” Symbols

- Lines 1-2: “I discovered these men driving a new pile / into the pier.”

- Lines 4-5: “a wooden pile, a massive affair, swinging / over the water on a long wire hawser.”

- Lines 23-24: “showed me that for all he cared the pile / could go on swinging until the crack of Doom.”

- Lines 43-44: “That left / the pile still in mid-air, and me of course.”

“From the Journal of a Disappointed Man” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

- Lines 10-11

- Lines 13-14

- Lines 17-18

- Lines 21-22

- Lines 29-31

- Lines 33-40

- Lines 42-44

Alliteration

- Line 1: “discovered,” “driving,” “pile”

- Line 2: “pier,” “paraphernalia”

- Line 3: “pulleys”

- Line 5: “water,” “wire”

- Line 9: “Speech,” “something”

- Line 17: “what,” “one”

- Line 18: “silent,” “subject”

- Line 21: “nearest,” “still saying,” “nothing”

- Line 28: “slackened,” “ceased”

- Line 29: “massive man”

- Line 32: “spoke,” “said,” “saw”

- Line 34: “brown bolus”

- Line 35: “he had”

- Line 36: “slow,” “descent,” “same,” “depths”

- Line 38: “smoked,” “cigarette”

- Line 44: “mid-air,” “me”

- Lines 1-2: “pile / into”

- Lines 2-3: “paraphernalia / of”

- Lines 4-5: “swinging / over”

- Lines 6-7: “style / as”

- Lines 12-13: “attention / to”

- Lines 13-14: “working / on”

- Lines 14-15: “tell / that”

- Lines 18-19: “thought / at”

- Lines 19-20: “indifferent / and”

- Lines 21-22: “nothing / but”

- Lines 23-24: “pile / could”

- Lines 25-26: “hour / and”

- Lines 26-27: “efforts / to”

- Lines 29-30: “abandoned / his”

- Lines 30-31: “rail / to”

- Lines 33-34: “eyes / followed”

- Lines 41-42: “incident / was”

- Lines 43-44: “left / the”

Juxtaposition

- Line 1: “men,” “pile”

- Line 4: “pile,” “massive”

- Line 6: “massive”

- Line 7: “the men,” “very,” “men”

- Line 8: “very,” “silent,” “men”

- Line 16: “men”

- Line 18: “silent”

- Line 20: “tired,” “tired”

- Line 21: “man”

- Line 23: “the pile”

- Line 26: “the men,” “slow”

- Line 29: “massive,” “man”

- Line 32: “No one,” “no one”

- Line 36: “slow”

- Line 43: “the men”

- Line 44: “the pile”

“From the Journal of a Disappointed Man” Vocabulary

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- Paraphernalia

- Monosyllables

- Crack of Doom

- (Location in poem: Line 1: “I discovered these men driving a new pile”; Line 4: “a wooden pile, a massive affair, swinging”; Lines 23-24: “the pile / could go on swinging until the crack of Doom.”; Lines 43-44: “That left / the pile still in mid-air, and me of course.”)

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “From the Journal of a Disappointed Man”

Rhyme scheme, “from the journal of a disappointed man” speaker, “from the journal of a disappointed man” setting, literary and historical context of “from the journal of a disappointed man”, more “from the journal of a disappointed man” resources, external resources.

The Poet's Life and Work — A biography of Andrew Motion via the Poetry Foundation.

An Interview with the Poet — Andrew Motion on writing and inspiration.

The Poet's Role — Andrew Motion discusses the poet's place in society.

More on the Author — Additional resources and media related to Andrew Motion, courtesy of the Poetry Archive.

Pile Driving and Piers — Watch a video of workmen (successfully!) setting up dock piles with a pile driver.

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

- Australia edition

- International edition

- Europe edition

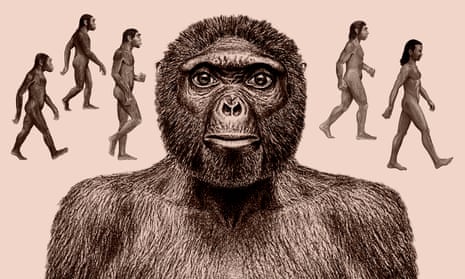

Tracing the tangled tracks of humankind's evolutionary journey

The path from ape to modern human is not a linear one. Hannah Devlin looks at what we know – and what might be next for our species

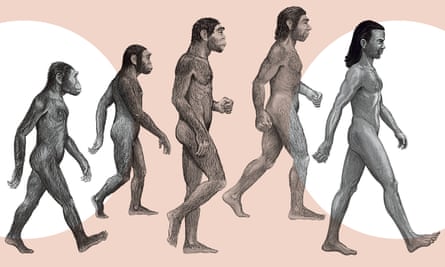

Let’s go back to the beginning. When did we and our ape cousins part ways? Scientists are still working on an exact date – or even a date to within a million years. Like many of the big questions in human evolution, the answer itself has evolved over the past few decades as new discoveries, techniques and technology have provided fresh insights.

Genetics has proved one of the most powerful tools for time-stamping the split with our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. When our complete genomes were compared in 2005 , the two species were found to share 98% of their DNA. The differences hold important clues to how long our lineages have been diverging. By estimating the rate at which new genetic mutations are acquired over generations, scientists can use the genetic differences as a “molecular clock” to give a rough idea of when the split occurred. Most calculations suggest it was between four to eight million years ago.

This time window is more recent than was originally thought. In the 1960s, fossil evidence led palaeontologists to conclude that a 14m-year-old ape, Ramapithecus, was the earliest ancestor on the human line, based on the shape of its jaw. Subsequent DNA analysis has revealed the split occurred long after that – Ramapithecus is now considered an orangutan ancestor.

So are scientists still looking for the “missing link” between us and other ape species? We still don’t know the identity of our most recent common ancestors with chimpanzees. But scientists tend to dislike the phrase “missing link”, as it implies that evolution proceeds in an orderly, linear fashion with well-defined junctures.

“It gives the sense that there is a single transitional form that magically bridges the gap between a living ape and a living human and suggests we’ve got to fit everything into our line of evolution,” says Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum.

The reality is messier: different branches evolve at different rates; new traits can emerge several times independently; splits can be dragged out over millennia and across continents, with populations diverging and then interbreeding again. Rather than the tree of life it’s more like a dense, thorny bush.

But can we assume that our last shared ancestor with other living apes was something like a chimp? Not necessarily – chimps are not simply unevolved versions of us. Our hypothetical common ancestor would have had a mixture of chimp-like traits, human-like traits and primitive traits that both species eventually left behind. The common ancestor might have walked on all fours, or might have been more upright.

Scientists are still trying to piece together this evolutionary jigsaw puzzle based on a shifting cast of creatures that show up in the fossil record. To complicate things, most of the fossils found probably represent evolutionary side-branches rather than direct ancestors.

Evolutionary timeline

55m years ago

First primates evolve.

15m years ago

Hominidae (great apes) split off from the ancestors of the gibbon.

8m years ago

Chimp and human lineages diverge from that of gorillas.

4.4m years ago

Ardipithecus appears: an early "proto-human" with grasping feet.

4m years ago

Australopithecines appeared, with brains about the size of a chimpanzee’s.

2.3m years ago

Homo habilis first appeared in Africa.

1.85m years ago

First "modern" hand emerges.

1.6m years ago

Hand axes are a major technological innovation.

800,000 years ago

Evidence of use of fire and cooking.

700,000 years ago

Modern humans and Neanderthals split.

400,000 years ago

Neanderthals begin to spread across Europe and Asia.

300,000 years ago

Evidence of early Homo sapiens in Morocco .

200,000 years ago

Homo sapiens found in Israel .

60,000 years ago

Modern human migration from Africa that led to modern-day non-African populations.

What are some of the important fossils I should know about? One of the earliest specimens that people believe lies on our lineage – or not far from it – is Sahelanthropus tchadensis , a six to seven-million-year-old fossil found in Chad. It has an ape-like sloping face, prominent brow and very small brain, but small human-like canine teeth. The spinal cord is positioned underneath the skull, rather than towards the back, which some say suggests the creature walked on two legs, but it’s hard to know for sure, since there’s just a skull and a few bones to go on.

Another fossil from around the same period found in Kenya, called Orrorin tugenensis (nicknamed Millennium Man), also features small teeth and a leg bone that indicates primitive bipedalism.

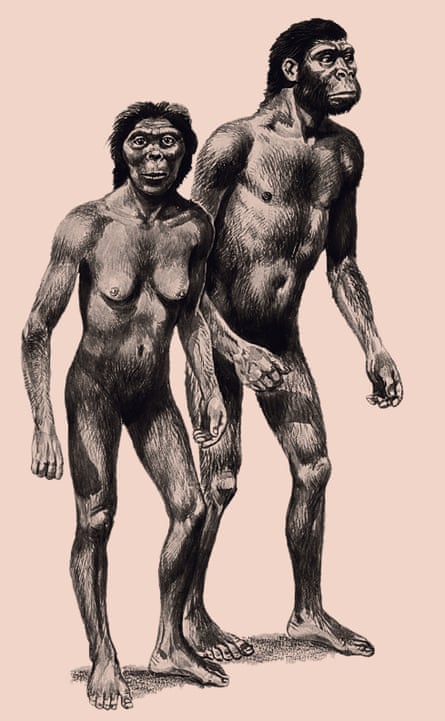

Slightly later, at 4.4m years, there is Ardipithecus ramidus (Ardi), a stunningly complete female skeleton found in Ethiopia. Ardi, who had a stocky frame and stood almost four feet (one metre) tall, had gangly ape-like arms and grasping big toe, suggesting she would have been an agile climber. Scientists are divided on the extent to which Ardi walked upright – some say she would have walked on two legs routinely, others think she would have just about managed it if she needed to use her arms to carry something. The pelvis bones are crushed and the skeleton does not include a knee, which could have helped resolve the question more definitively. The strongest evidence for Ardi being a direct ancestor, or very close to our lineage, comes from her teeth, which were small and stubby – more like modern human teeth – and lacked the large fang-like canines of chimpanzees, gorillas and earlier extinct apes.

Then comes “Lucy”, a 3.18m-year-old skeleton, named after the Beatles song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, the soundtrack to the 1974 excavation. Lucy is viewed as one of the most important discoveries in palaeontology as she is a unique amalgam of primitive features – a chimpanzee-sized brain, a powerful jaw and long, dangling arms – and incredibly human ones. In particular, her legs, knee and pelvis are strikingly similar to our own anatomy, suggesting that by this point our ancestors had gained the distinctive human abilities of being able to walk and run.

Lucy also helped cement a growing acceptance of Africa as the cradle of humanity, reflected in her species’ scientific name: Australopithecus afarensis . Scientists now think that the australopithecine genus (in the taxonomical hierarchy, genus is one up from species) gradually evolved and spread across southern and eastern Africa – and that one of these species seeded the next phase of our evolution.

Why did our ancestors start walking upright? The traditional “savannah theory” held that shifts in the climate led to dense forests being replaced by sweeping grasslands, creating a new incentive for being able to travel long distances by foot. Yet the transition towards bipedalism appears to have started at least six million years ago – long before the African climate dried out enough to create savannahs. To complicate matters further, a recent analysis of the Lucy fossil suggests that multiple fractures had been sustained shortly before her death, leading some to speculate that she may have died falling out of a tree .

A more recent idea is that bipedalism first emerged in the forests, which would be consistent with the fossil record and may also have a modern-day parallel. Orangutans in Sumatra have been observed moving through the forest canopy by walking along branches on two legs while using their arms to help support their weight or hang, allowing them to move through thinner branches than would otherwise be possible.

Whatever prompted our transition from four legs to two, it seems to have happened over millions of years, probably with a long period of travelling between the ground and the trees.

So once we got the hang of walking, what happened next? The boundary for when our ancestors started counting as human is blurry and somewhat subjective, but scientists place the starting point at species that emerged about 2.4m years ago, which are designated to the Homo genus. We are the sole survivors of this group, but the Earth was once home to a surprising diversity of humans, some of whom crossed paths with our own ancestors.

One of the earliest of these is Homo habilis , who lived in Africa between 2.4m and 1.4m years ago. The name means “handyman” because this species was originally thought to represent the first maker of stone tools (since then, sharpened stones, hammers and anvils dating to 3.3m years ago have been discovered). Homohabilis was short (between one and 1.4 metres or 3ft 4in - 4ft 5in) had a protruding face and massive teeth – earning one fossil the nickname Nutcracker Man. His braincase was about 50% bigger than that of the Australopithicenes, but still only half as big as a modern human’s.

Homo erectus , 1.7-1.8m years ago, was much closer to modern humans anatomically. He was taller (1.5 to two metres or 4ft 9in - 6ft 1in) and bigger-brained than Homo habilis and had a far smaller jaw and teeth, implying a change in diet. Harvard anthropologist Richard Wrangham argues that the striking change in jaw anatomy suggests Homo erectus mastered fire and began cooking, allowing more efficient foraging and digestion, freeing up energy to fuel a larger brain. Homo erectus has sometimes been called the first cosmopolitan, due to the impressive geographical range it spanned, with fossils found in Africa, Spain, Italy, China and Indonesia.

The earliest evidence of Homo sapiens (that’s us) comes from fossils dated to just over 300,000 years ago excavated from a cave in Morocco . The bones of at least five people were found alongside tools, gazelle bones and lumps of charcoal. Jean-Jacques Hublin, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig who excavated the fossils, told the Guardian last year: “The face of the specimen we found is the face of someone you could meet on the tube in London.”

When did humans leave Africa and spread across the globe? Until recently, converging lines of evidence from fossils, genetics and archaeology suggested that modern humans first spread from Africa into Eurasia about 60,000 years ago. However, a series of recent discoveries – including a trove of 100,000-year-old human teeth found in a cave in China, and a nearly 200,000-year-old jawbone in northern Israel – show that Homo sapiens was venturing across the world far earlier than once thought.

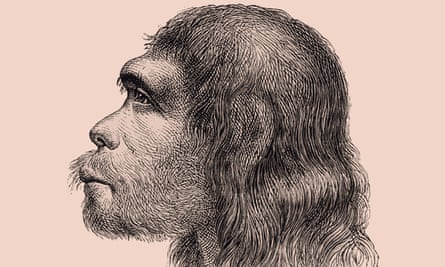

However, these early exits appear to have contributed very little to the genetics of modern day populations – perhaps these groups died out or were killed off by subsequent migratory waves. By triangulating the common ancestors of modern day populations, scientists can show that the ancestors of African and non-African people alive today converge at around 60,000 years ago. As these ancestors travelled across continents they would have encountered a motley assortment of other archaic human species, including the Neanderthals in Eurasia, the Denisovans in Siberia, possibly a dwarf species known as “ the hobbit ” ( Homo floresiensis ) on the Indonesian island of Flores and probably other species that we do not yet know about.

Did we kill off the Neanderthals? Neanderthals tend to be cast as the low-browed thugs of the prehistoric world, who stood little chance against the superior intellect and hunting prowess of our own ancestors. This may be a case of unfair stereotyping, though. Neanderthals had bigger brains than us, they made jewellery, buried their dead in ancient ceremonies and used pigments – possibly for tribal markings.

It is true, however, that the Neanderthals went into a steep decline around 40,000 years ago, at a time when Homo sapiens from Africa were settling in Eurasia. Perhaps they were struggling to compete for resources, were killed in conflicts or were simply less well adapted to changes in climate that led our own ancestors to move north and east.

There’s a postscript to this story. While the Neanderthals died out as a species, in one sense they are still around today. Interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals means that all non-Africans alive today carry about 1-5% Neanderthal DNA . Everyone has acquired slightly different parts of the Neanderthal genome and so collectively there is a substantial fraction (at least 20%) of the Neanderthal genome spread through the living human population.

Wait ... we interbred with another species? Yes, genetics shows that the ancestors of everyone outside of Africa interbred with Neanderthals, probably more than once. There was also interbreeding with another archaic group called the Denisovans. We don’t know much about what these other ancient cousins looked like as their fossils are so fragmented. But from a finger bone found in a cave in Siberia, scientists were able to extract high quality DNA belonging to a Denisovan girl who lived about 41,000 years ago.

Intriguingly, Denisovan DNA shows up only in modern day Indigenous Australians and Papua New Guineans, suggesting that their ancestors must have met the Denisovans on their way across the globe, probably somewhere in south-east Asia.

We can only speculate on the circumstances of these interbreeding events and whether they were peaceful mergers of different tribes or violent encounters.

Could we use cloning to bring our extinct cousins back to life? Theoretically, it would be possible to cut and paste Neanderthal or Denisovan mutations into a modern human genome, and then transfer that into an egg and grow a baby using a surrogate mother. In his book Regenesis: How Synthetic Biology Will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves , Harvard geneticist George Church speculates about the possibility of using genetic engineering to resurrect extinct creatures. “If society becomes comfortable with cloning and sees value in true human diversity, then the whole Neanderthal creature itself could be cloned by a surrogate mother chimp – or by an extremely adventurous female human,” Church wrote.

In a less ethically fraught version of this experiment, scientists at several labs are currently growing Neanderthalised cells and even organoids – miniature brains and livers – to better understand how Neanderthal biology differed from our own.

When did we learn to speak? This is tricky, as language leaves no direct trace on the fossil record and even today’s neuroscientists haven’t fully figured out how the human brain produces language. Some argue that primitive versions of language pre-date Homo sapiens , based on early evidence of collective hunting and other sophisticated behaviours. For instance, Boxgrove Man, a 500,000 year old Homo heidelbergensis fossil (another extinct relative), was found alongside the remains of now extinct species of rhinoceros, bears and voles, which had signs of having been butchered.

The so-called language gene FOXP2 , known to be crucial for speech, also holds clues. The Homo sapiens version of this gene has mutations that are not seen in chimps or other animals. We now know that Neanderthals shared these same mutations. However, modern humans have double the number of mutations in FOXP2’s flanking DNA that determines when the gene is switched on and off, hinting that we could have evolved a qualitatively different capacity for language than our relatives.

Human evolution is not over, but it’s impossible to predict how we’re going to turn out. It’s tempting to assume that we are on an ever-upward intellectual trajectory, but there’s no guarantee of this. In fact, the human brain has become about 5-10% smaller during the past 20,000 years. Perhaps this is comparable to the pattern seen in domestic animals, which almost always have smaller brains than their wild counterparts. “Maybe we’ve domesticated ourselves and those bits of the brain that our ancestors needed aren’t so important any more,” says Stringer.

It’s also possible that we are swapping individual brainpower for collective forms of intelligence. “Our brains are energetically very expensive – they use about 20% of our energy,” says Stringer. “So if evolution can get away with a smaller brain it will.”

Further reading

Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature by Thomas Huxley

Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind by Donald Johanson and Maitland Edey

Our Human Story by Louise Humphry and Chris Stringer

Regenesis : How Synthetic Biology Will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves by George Church

A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived : the Stories in Our Genes by Adam Rutherford

- The briefing

Most viewed

Have an account?

James Forten Lesson 14 Comprehension

10 questions

Introducing new Paper mode

No student devices needed. Know more

Which event in the article is described first?

James Forten plays marbles.

James Forten goes to school.

Thomas Forten frees his wife.

Thomas Forten works making sails.

Which detail supports the idea that sail making is a difficult job?

Thomas Forten helps install the sails.

The thread can easily cut through flesh.

Thomas Forten is employed by Robert Bridges.

Sail makers in Philadelphia work particularly hard.

What aspect of US history best explains the fact that Thomas Forten has to buy his wife's freedom?

the Civil War

women's rights

the practice of slavery

the Declaration of Independence

Right after Thomas Forten dies, James

works in a ship.

continues to go to school.

gets permission to go to sea.

What happens before James joins the crew of the Royal Louis?

The ship sails out of Philadelphia

James carries gunpowder to the guns.

James sees African captives on the ships.

The Active lowers its flag in surrender.

Why are the owners and crew of the Royal Louis allowed to share the proceeds from the sale of the Active ?

A privateer gave them permission

They received a note from the British king.

They received a letter of marque from the king.

They were told they could in a speech from the Active's captain.

What happens after the crew of the Royal Louis sights three British ships?

The Royal Louis surrenders.

The captain carefully checks the ship.

The crew carries more gunpowder on board.

The Panoma takes off for the island of Barbados.

What detail from the article best supports the idea that Forten felt terrified after the Royal Louis surrendered to the British?

The crew was taken aboard the Amphyon.

Captain Beasley looked over the prisoners.

There were rumors of captured Africans being sold into slavery

Once on board the British ship, the boys were separated from the older men.

Use the biography "James Forten" and the text "Modern Minute Man" to answer the following questions. What do Charles Price and James Forten have in common?

They fight oni actual battles.

They both seek a life at sea.

They are not Revolutionary War heroes.

They live the same historical time period.

How is the structure of "Modern Minute Man" different from the way the story of "James Forten" is told?

Modern Minute Man is about the soldier

Modern Minute Man is in interview format

Modern Minute Man compares two events

Moden Minute Man reads more like a story

Explore all questions with a free account

Continue with email

Continue with phone

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like blood, geneticist, DNA/ blood type and more. ... Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. Teacher 35 terms. SullivanLatin. Preview. US History Chptr 30. 20 terms. kgiesen3. Preview. History 1700 Final . 120 terms. brhend2005. Preview. History Unit 2 Quiz Review.

The journey of man began in Africa. What are three primary routes that early man took after leaving Africa? Man went to Siberia, Australia, and central Asia. What was the mode of transportation that early man used to move from North American into Cental and South America?

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Africa, Archeological, Blood and more. ... The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey Video Questions. 9 terms. juliaalxandr77. Preview. Journey of Man. 34 terms. joyjoymarie. Preview. JOURNEY OF MAN. 30 terms. alanzel. Preview. PURPCOM: Module 8.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like What is the source of the time machine, what population is the oldest lineage of people, what country is san bushman from and more. ... The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey Video Questions. 9 terms. juliaalxandr77. Preview. ANP 370 Exam 2 Authors. 22 terms. MeenaAoude. Preview ...

Journey of Man. Term. 1 / 62. fossil. Click the card to flip 👆. Definition. 1 / 62. the remains (or an impression) of a plant or animal that existed in a past geological age and that has been excavated from the soil. Click the card to flip 👆.

The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey is a 2002 book by Spencer Wells, an American geneticist and anthropologist, in which he uses techniques and theories of genetics and evolutionary biology to trace the geographical dispersal of early human migrations out of Africa. The book was made into a TV documentary in 2003.

The Journey of Man ends with the author lamenting the genetic mixing within the global melting pot, the loss of linguistic diversity and the urbanization of village culture. He views this globalization as creating a rapidly shrinking window of opportunity for geneticists to discover our history before it is lost forever. This is an ...

The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. 2003. If God ever gave mankind a mission - it was not so much to multiply as to walk. And walk we did, to the farthest corners of the earth. Homo sapiens sapiens is the only mammal to have spread from its place of origin, Africa, to every other continent - before settling down to sedentary life ogling ...

This is Spencer Wells - The journey of man - A genetic odyssey. Part 1 of 13. Where did homo sapiens originate from? How did we spread across the face of the...

The journey is potentially dangerous. By undertaking the journey, Telemachus shows that he has inherited his father's courage, and he begins to forge a reputation in his society as a brave and adventurous man. His visits to Nestor and Menelaus require him to tactfully observe the social rules that bind travelers and guests.

809 writers online. Learn More. The Journey of Man, a Genetic Odyssey by Spencer Wells is an informative documentary where the author explains his theory of the origin of man using genetics. The hypothesis is intensely intriguing and, while he presents convincing facts on the matter, I would take the information with a grain of salt.

Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. By Spencer Wells By analyzing DNA from people in all regions of the world, geneticist Spencer Wells has concluded that all humans alive today are descended from a single man who lived in Africa around 60,000 years ago. Modern humans, he contends, didn't start their spread across the globe until after that time.

The Journey of Man. : Spencer Wells. Princeton University Press, Mar 28, 2017 - Reference - 240 pages. Around 200,000 years ago, a man--identical to us in all important respects--lived in Africa. Every person alive today is descended from him. How did this real-life Adam wind up father of us all?

The video above is from the January 2013 iPad edition of National Geographic magazine. Groups of modern humans— Homo sapiens —began their migration out of Africa some 60,000 years ago. Some of our early ancestors kept exploring until they spread to all corners of Earth. How far and fast they went depended on climate, the pressures of ...

Summary. ' From the Journal of a Disappointed Man ' by describes the actions of construction workers who labor to build a pier. The poem takes the reader through the 's initial impression of the men and then how that impression evolves as he studies them. He admits his fascination with their actions and minds and eventually comes to ...

Learn More. "From the Journal of a Disappointed Man" appears in Andrew Motion's 2009 collection The Mower: New and Selected Poems. The poem describes this man's observations of an ill-fated construction job, during which a work crew tries to drive a pile (support column) into a pier. The crew encounters a mysterious problem, gives up on solving ...

Soon this important documentary will no longer be available on this channel. But as long as copyrights allow the video remains to be seen at this location: h...

From the Journal of a Disappointed Man Lyrics. I discovered these men driving a new pile into the pier. over the water on a long wire hawser. very ruminative and silent men ignoring me. "Let go ...

Homohabilis was short (between one and 1.4 metres or 3ft 4in - 4ft 5in) had a protruding face and massive teeth - earning one fossil the nickname Nutcracker Man. His braincase was about 50% ...

To purchase print edition or for more info: https://goo.gl/TX5bCzTo purchase, download and print instantly: http://bit.ly/3898qfnPerformance Marching Band - ...

1 pt. Which detail supports the idea that sail making is a difficult job? Thomas Forten helps install the sails. The thread can easily cut through flesh. Thomas Forten is employed by Robert Bridges. Sail makers in Philadelphia work particularly hard. 3.