- Search Menu

- Volume 27, Issue 3, March 2024

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why publish with IJNP?

- About the CINP

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

RESEARCH ON TOURISM ATTRACTION, TOURISM EXPERIENCE VALUE PERCEPTION AND PSYCHOLOGICAL TENDENCY OF TRADITIONAL RURAL TOURISM DESTINATIONS

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Guangming Han, Chaozhi Zhu, RESEARCH ON TOURISM ATTRACTION, TOURISM EXPERIENCE VALUE PERCEPTION AND PSYCHOLOGICAL TENDENCY OF TRADITIONAL RURAL TOURISM DESTINATIONS, International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology , Volume 25, Issue Supplement_1, July 2022, Pages A72–A73, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyac032.099

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In recent years, rural tourism has become an important way to implement the Rural Revitalization Strategy in China, and traditional villages have become an important type of rural tourism destination. On the one hand, how to improve the attraction of traditional rural tourism, on the other hand, how to meet the escalating experience needs of rural tourists, so as to make the sustainable development of traditional rural tourism and promote rural rejuvenation, is an urgent problem for traditional rural tourism stakeholders. Especially in the increasingly competitive rural tourism destinations, how to cultivate loyal tourists has become a major problem faced by tourism destinations. This paper puts forward the following assumptions about the emotional work of rural tourism practitioners

H1: the surface behavior dimension of emotional labor is positively correlated with work pressure.

H2: the deep behavioral dimension of emotional labor is negatively correlated with work stress.

H3: the surface behavior dimension of emotional labor has a positive impact on job burnout.

H4: the deep behavioral dimension of emotional labor has a negative impact on job burnout

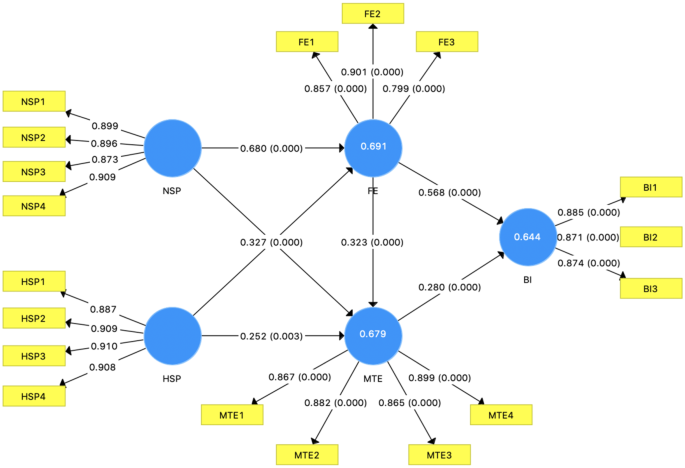

From the perspective of psychology, taking the “first behavior result” of tourists in traditional villages and rural tourism destinations as the research object, and drawing lessons from the theory of self-determination and psychological ownership, this paper constructs and verifies the research model formed by tourists' experience perceived loyalty in rural tourism destination scenic spots. Thus, it reveals the interactive mechanism between the antecedents and behaviors, behaviors and results of traditional rural tourism destination tourists and rural tourism attraction, experience perception participation and loyalty attraction. According to the theoretical hypothesis, we use Amos to construct the formation model of experience perceived loyalty of rural tourism destination tourists, and use maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to estimate the parameters of the model. The model includes 7 dimensions and 32 observation indicators. The perception dimension of experience value includes three sub dimensions: rural tourism service value perception, rural tourism emotional value perception and rural tourism resources and environment perception. The upper layer of these three sub dimensions constitutes the general dimension of “rural tourism experience value perception”. 1031 questionnaires were distributed, 945 valid questionnaires were distributed, and the effective rate was 91.7%. A field survey was conducted on many traditional rural tourism destinations in China. At the same time, the emotional behavior of tourism practitioners in various regions was investigated. The questionnaire is designed to objectively evaluate the individual's sense of self-worth or social ability. The original scale consists of 32 items. Helmreich and Stapp (1974) modified the scale and divided it into two independent 16 item scales to shorten the test time. The following criteria are followed in the composition of the two scales: the correlation between the subscale and the total scale is equivalent, the average scores between the scales and between different genders are equal, the score distribution is equal, and the corresponding factor structure. The correlation coefficient between the two subscales and the 32 item version of the total scale is 0.97, and the correlation coefficient between them is 0.87. Many researchers using tsbi only use one of the subscales. The 32 item version of tsbi factor analysis produced a large factor item and four theoretically related factor items: confidence, dominance, social ability, social withdrawal or relationship with authority. The subjects answered these statements on a 5-level scale, with a total score ranging from 0 to 64.

The perceived value of rural tourism resources has a significant effect on the attractiveness and loyalty of traditional tourism resources. In this process, experience value perception plays a positive intermediary role between resource attraction and tourist loyalty. The attraction of traditional village rural tourism services has a positive impact on tourist loyalty. The higher the service attraction, the higher the tourist loyalty. However, the indirect impact of service attractiveness on tourist loyalty is not significant, mainly because the value perception of tourists caused by high service attractiveness is not necessarily very high. The attraction of traditional rural tourism environment has an indirect negative impact on tourist loyalty. However, the correlation analysis in Table 3 shows that there is a significant positive correlation between environmental attractiveness and tourist loyalty. The self-control of tourism employees was negatively correlated with emotion perception, emotion evaluation, emotion control and emotion regulation reflex (P < 0.01), and negatively correlated with emotion regulation self-efficacy (P < 0.05), which had nothing to do with the applied emotion strategies. The self-care ability and emotion regulation ability were significantly positively correlated with each dimension (P < 0.01); Encouraging autonomy and emotion regulation ability were significantly positively correlated with each dimension (P < 0.01); The ability of self-control and emotion regulation were significantly negatively correlated with each dimension (P < 0.01).

Traditional villages should give full play to the advantages of traditional rural tourism resources, maintain the “countryside” and rural authenticity, and enhance the attraction of tourism resources. When developing rural tourism in traditional villages, we should improve the service attraction and pay attention to the needs of tourists' experience value. Considering the different characteristics of the spatial distance between traditional rural tourism and other types of tourism destinations, traditional rural tourism destinations should create a rural tourism environment conducive to tourists' spatial perception. The emotional regulation of tourism service personnel is also conducive to bring positive feedback to rural tourism.

- emotional regulation

Email alerts

Citing articles via, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1469-5111

- Copyright © 2024 Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The Other Half of Urban Tourism: Research Directions in the Global South

- First Online: 14 July 2021

Cite this chapter

- Christian M. Rogerson 4 &

- Jayne M. Rogerson 4

Part of the book series: GeoJournal Library ((URPGS))

573 Accesses

7 Citations

In mainstream urban tourism scholarship debates there is only limited attention given to the urban global South. The ‘other half’ of urban tourism is the axis in this review and analysis. Arguably, in light of the changing global patterns of urbanization and of the shifting geography of leading destinations for urban tourism greater attention is justified towards urban settlements in the global South. The analysis discloses the appearance of an increasingly vibrant scholarship about urban tourism in the setting of the global South. In respect of sizes of urban settlement it is unsurprising that the greatest amount of attention has been paid to mega-cities and large urban centres with far less attention so far given to tourism occurring either in intermediate centres or small towns. In a comparative assessment between scholarship on urban tourism in the global North versus South there are identifiable common themes and trends in writings about urban tourism, most especially in relation to the phenomenon of inter-urban competition, questions of sustainability and planning. Nevertheless, certain important differences can be isolated. In the urban global South the environment of low incomes and informality coalesce to provide for the greater significance of certain different forms of tourism to those which are high on the urban global North agenda. Three key issues are highlighted by this ‘state of the art’ overview, namely the significance of an informal sector of tourism, the distinctive characteristics of the discretionary mobilities of the poor, and the controversies surrounding slum tourism.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

In 2020 the World Bank introduced a new classification of countries: low-income, low-middle income, upper-middle income and high income. Macao SAR, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Qatar are classed as high income. As the focus of this book is South Africa, which the World Bank classifies as falling in the category of upper-middle income bracket, the high income urban destinations are viewed as Norths within the South and thus not included in our research overview of the global South.

This section builds upon and extends certain of the discussion presented in Rogerson and Saarinen ( 2018 ).

Aall, C., & Koens, K. (2019). The discourse on sustainable urban tourism: The need for discussing more than overtourism. Sustainability, 11 (15), 4228.

Article Google Scholar

Adam, I. (2013). Urban hotel development patterns in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Tourism Planning and Development, 10 , 85–98.

Adam, I., & Amuquandoh, F. E. (2013a). Hotel characteristics and location decisions in Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Tourism Geographies, 16 (4), 653–668.

Adam, I., & Amuquandoh, F. E. (2013b). Dimensions of hotel location decisions in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Tourism Management Perspectives, 8 , 1–8.

Adie, B. A., & Cepeda, R. G. (2018). Film tourism and cultural performance: Mexico City’s day of the dead parade. In E. Kromidha & S. Deesilatham (Eds.), Inclusive innovation for enhanced local experience in tourism: Workshop proceedings, Phuket, Thailand , pp. 33–36.

Google Scholar

Alliance, C. (2014). Africa regional strategy: Final document . Brussels: Cities Alliance.

Amanpour, M., & Nikfetrat, M. (2020). The effect of urban tourism on economic sustainable development of Sari City. Iranian Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8 (1), 87–97.

Amore, A., & Hall, C. M. (2017). National and urban public policy in tourism: Towards the emergence of a hyperneoliberal script? International Journal of Tourism Policy, 7 (1), 4–22.

Amore, A., & Roy, H. (2020). Blending foodscapes and urban touristscapes: International tourism and city marketing in Indian cities. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6 (3), 639–655.

Angelini, A. (2020). A favela that yields fruit: Community-based tour guides as brokers in the political economy of cultural difference. Space and Culture, 23 (1), 15–33.

Ashworth, G. J. (1989). Urban tourism: An imbalance in attention. Progress in Tourism, Recreation and Hospitality Management, 1 , 33–54.

Ashworth, G. J. (2012). Do we understand urban tourism? Journal of Tourism & Hospitality, 1 (4), 1–2.

Ashworth, G. J., & Page, S. (2011). Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tourism Management, 32 (1), 1–15.

Aukland, K. (2018). At the confluence of leisure and devotion: Hindu pilgrimage and domestic tourism in India. Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 6 (1), 18–33.

Avieli, N. (2013). What is ‘local food’?: Dynamic culinary heritage in the world heritage site of Hoi An, Vietnam. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 8 (2–3), 120–132.

Bao, J., Li, M., & Liang, Z. (2020). Urban tourism in China. In S. Huang & G. Chen (Eds.), Handbook on tourism and China (pp. 116–130). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Chapter Google Scholar

Baumgart, S., & Kreibich, V. (2011). Informal urbanization – Historical and geographical perspectives. disP – The Planning Review, 47 (187), 12–23.

Bellini, N., Go, F.M., & Pasquinelli, C. (2017). Urban tourism and city development: Notes for an integrated policy agenda. In N. Bellini & C. Pasquinelli (Eds.), Tourism In The City: Towards an Integrative Agenda on Urban Tourism (pp. 333–339). Cham: SpringerTourism

Bhati, A., & Pearce, P. (2017). Tourist attractions in Bangkok and Singapore; linking vandalism and setting characteristics. Tourism Management, 63 , 15–30.

Bhoola, S. (2020). Halal food tourism: Perceptions of relevance and viability for South African destinations. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9 (3), 288–301.

Bogale, D., & Wondirad, A. (2019). Determinant factors of tourist satisfaction in Arbaminch City and its vicinity, southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 9 (4), 320–348.

Booyens, I. (2010). Rethinking township tourism: Towards responsible tourism development in South African townships. Development Southern Africa, 27 (2), 273–287.

Booyens, I. (2021). The evolution of township tourism in South Africa. In J. Saarinen & J. M. Rogerson (Eds.), Tourism, change and the global South . Abingdon: Routledge.

Booyens, I., & Rogerson, C. M. (2019a). Creative tourism: South African township explorations. Tourism Review, 74 (2), 256–267.

Booyens, I., & Rogerson, C. M. (2019b). Recreating slum tourism: Perspectives from South Africa. Urbani izziv, 30 (Supplement), 52–63.

Bowman, K. (2015). Policy choice, social structure, and international tourism in Buenos Aires, Havana and Rio de Janeiro. Latin American Research Review, 50 (3), 135–156.

Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), 484–490.

Brouder, P., & Ioannides, D. (2014). Urban tourism and evolutionary economic geography: Complexity and co-evolution in contested spaces. Urban Forum, 25 (4), 419–430.

Buning, M., & Grunau, T. (2014) Touring Katutura!: Developments, structures and representations in township tourism in Windhoek (Namibia) . Paper presented at the Destination Slum! 2 Conference, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany, 14–16 May.

Burgold, J., & Rolfes, M. (2013). Of voyeuristic safari tours and responsible tourism with educational value: Observing moral communication in slum and township tourism in Cape Town and Mumbai. Die Erde, 144 (2), 161–174.

Burrai, E., Mostafanezhad, M., & Hannam, K. (2017). Moral assemblages of volunteer tourism development in Cusco, Peru. Tourism Geographies, 19 (3), 362–377.

Burton, C., Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2020). The making of a ‘big 5’ game reserve as an urban tourism destination: Dinokeng, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9 (6), 892–911.

Cantu, L. (2002). De ambiente: Queer tourism and the shifting boundaries of Mexican male sexualities. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 8 (1–2), 139–166.

Carlisle, S., Johansen, A., & Kunc, M. (2016). Strategic foresight for (coastal) urban tourism market complexity: The case of Bournemouth. Tourism Management, 54 , 81–95.

Cejas, M. I. (2006). Tourism in shantytowns and slums: A new “contact zone” in the era of globalization. Intercultural Communication Studies, 15 (2), 224–230.

Chand, M., Dahiya, A., & Patil, L. S. (2007). Gastronomy tourism – A tool for promoting Jharkhand as a tourist destination. Atna Journal of Tourism Studies, 2 , 88–100.

Cheer, J. (2020). Human flourishing, tourism transformation and COVID-19: A conceptual touchstone. Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), 514–524.

Chege, P. W., & Mwisukha, A. (2013). Benefits of slum tourism in Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of Arts and Commerce, 2 (4), 94–102.

Chen, M., & Carré, F. (Eds.). (2020). The informal economy revisited: Examining the past, envisioning the future . London: Routledge.

Chen, M., Roever, S., & Skinner, C. (2016). Urban livelihoods: Reframing theory and policy. Environment and Urbanization, 28 (2), 331–342.

Chen, Q., & Huang, R. (2016). Understanding the importance of food tourism in Chongqing, China. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22 (1), 42–54.

Chianeh, R. H., del Chiappa, G., & Ghasemi, V. (2018). Cultural and religious tourism development in Iran: Prospects and challenges. Anatolia, 29 (2), 204–214.

Christie, I., Fernandes, E., Messerli, H., & Twining-Ward, L. (2013). Tourism in Africa: Harnessing tourism for growth and improved livelihoods . Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., & Seisdedos, G. (2021). Smart urban tourism destinations at a crossroads – Being ‘smart’ and urban are no longer enough. In A. M. Morrison & J. A. Coca-Stefaniak (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of tourism cities . London: Routledge.

Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., Morrison, A. M., Edwards, D., Graburn, N., Liu, C., Ooi, C. S., Pearce, P., Stepchenkova, S., Richards, G. W., So, A., Spirou, C., Dinnie, K., Heeley, J., Puczkó, L., Shen, H., Selby, M., Kim, H.-B., & Du, G. (2016). Editorial: Views from the editorial board of the International Journal of Tourism Cities. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2 (4), 273–280.

Cohen, E., & Cohen, S. A. (2015a). A mobilities approach to tourism from emerging world regions. Current Issues in Tourism, 18 (1), 11–43.

Cohen, E., & Cohen, S. A. (2015b). Beyond Eurocentrism in tourism: A paradigm shift in mobilities. Tourism Recreation Research, 40 (2), 157–168.

Colantonio, A. (2004). Tourism in Havana during the special period: Impacts, residents’ perceptions, and planning issues. Cuba in Transition, 14 (2), 20–42.

Colantonio, A., & Potter, R. B. (2006). Urban tourism and development in the socialist state: Havana during the special period . Aldershot: Ashgate.

Coles, C., & Mitchell, J. (2009). Pro poor analysis of the business and conference value chain in Accra: Final report . London: Overseas Development Institute.

Colomb, C., & Novy, J. (Eds.). (2016). Protest and resistance in the tourist city . Abingdon: Routledge.

Condevaux, A., Djament-Tran, G., & Gravari-Barbas, M. (2016). Before and after tourism(s) – The trajectories of tourist destinations and the role of actors involved in “off-the-beaten track” tourism: A literature review. Via@Tourism Review, 1 (9), 2–27.

Cong, L., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., & Xi, K. (2014). The spatial distribution and clustering of convention facilities in Beijing, China. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19 (9), 1070–1090.

Crush, J., & Chikanda, A. (2015). South-south medical tourism and the quest for health in southern Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 124 , 313–320.

Crush, J., Skinner, C., & Chikanda, A. (2015). Informal migrant entrepreneurship and inclusive growth in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique (Migration policy series no. 68). Cape Town: The Southern African Migration Programme.

Book Google Scholar

Cruz, F. G. S., Tito, J. C., Perez-Galvez, J. C., & Medina-Viruel, M. J. (2019). Gastronomic experiences of foreign tourists in developing countries: The case in the city of Oruro (Bolivia). Heliyon, 5 (7), e02011.

Cudny, W., Michalski, T., & Ruba, R. (Eds.). (2012). Tourism and the transformation of large cities in the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe . Lódz: University of Lódz.

Da Cunha, N. V. (2019). Public policies and tourist saturation in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. In C. Milano, J. M. Cheer, & M. Novelli (Eds.), Overtourism; excesses, discontent and measures in travel and tourism (pp. 152–166). Wallingford: CABI.

Daskalopoulou, I., & Petrou, A. (2009). Urban tourism competitiveness: Networks and the regional asset base. Urban Studies, 46 (4), 779–801.

de Jesus, D. S. V. (2020). The boys of summer: Gay sex tourism in Rio de Janeiro. Advances in Anthropology, 10 , 125–146.

Del Lama, E. A., de la Corte Bacci, D., Martins, L., Gracia, M. D. G. M., & Dehira, L. K. (2015). Urban geotourism and the old centre of São Paulo City, Brazil. Geoheritage, 7 , 147–164.

Diaz-Parra, I., & Jover, J. (2021). Overtourism, place alienation and the right to the city: Insights from the historic centre of Seville, Spain. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29 (2–3), 158–175.

Diekmann, A., & Hannam, K. (2012). Touristic mobilities in India’s slum spaces. Annals of Tourism Research, 39 (3), 1315–1336.

Dirksmeier, P., & Helbrecht, I. (2015). Resident perceptions of new urban tourism: A neglected geography of prejudice. Geography Compass, 9 (5), 276–285.

Dixit, S. K. (Ed.). (2021). Tourism in Asian cities . London: Routledge.

Dovey, K. (2015). Sustainable informal settlements. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 179 , 5–13.

Dovey, K., & King, R. (2012). Informal urbanism and the taste for slums. Tourism Geographies, 14 (2), 275–293.

Drummond, J., & Drummond, F. (2021). The historical evolution of the cultural and creative economy of Mahikeng, South Africa: Implications for contemporary policy. In R. Comunian, B. J. Hracs, & L. England (Eds.), Developing creative economies in Africa: Policies and practice (pp. 97–112). London: Routledge.

Duchesneau-Custeau, A. (2020). ‘Theirs seemed like a lot more fun’: Favela tourism, commoditization of poverty and stereotypes of the self and the other . Masters paper in Globalization and International Development, School of International Development and Global Studies, University of Ottawa, Canada.

Dumbrovská, V., & Fialová, D. (2014). Tourist intensity in capital cities in Central Europe: Comparative analysis of tourism in Prague, Vienna and Budapest. Czech Journal of Tourism, 1 , 5–26.

Dürr, E., & Jaffe, R. (2012). Theorising slum tourism: Performing, negotiating and transforming inequality. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 93 , 113–123.

Dürr, E., Jaffe, R., & Jones, G. A. (2020). Brokers and tours: Selling urban poverty and violence in Latin America and the Caribbean. Space and Culture, 23 (1), 4–14.

Dyson, P. (2012). Slum tourism: Representing and interpreting ‘reality’ in Dharavi, Mumbai. Tourism Geographies, 14 (2), 254–274.

Ele, C. O. (2017). Religious tourism in Nigeria: The economic perspective. Online Journal of Arts, Management and Social Sciences, 2 (1), 220–232.

Faisal, A., Albrecht, J. N., & Coetzee, W. J. L. (2020). Renegotiating organisational crisis management in urban tourism: Strategic imperatives of niche construction. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6 (4), 885–905.

Ferreira, S., & Visser, G. (2007). Creating an African Riviera: Revisiting the impact of the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront development in Cape Town. Urban Forum, 18 (3), 227–246.

Fletcher, R., Mas, I. M., Blanco-Romero, A., & Blázquez-Salom, M. (2019). Tourism and degrowth: An emerging agenda for research and praxis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27 (12), 1745–1763.

Florida, R., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2020). Cities in a post-COVID world (Utrecht University papers in evolutionary geography no 20.41). Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Freire-Medeiros, B. (2014). Tourism and poverty . London: Routledge.

Freire-Medeiros, B., Vilarouca, M. G., & Menezes, P. (2013). International tourists in a ‘pacified’ favela: The case of Santa Marta, Rio de Janeiro. Die Erde, 144 (2), 147–159.

Frenzel, F. (2013). Slum tourism in the context of the tourism and poverty (relief) debate. Die Erde, 144 , 117–128.

Frenzel, F. (2016). Slumming it: The tourist valorization of urban poverty . London: Zed.

Frenzel, F. (2017). Tourist agency as valorisation: Making Dharavi into a tourist attraction. Annals of Tourism Research, 66 , 159–169.

Frenzel, F. (2019). Slum tourism. In The Wiley Blackwell encyclopaedia of urban and regional studies. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118568446.eurs0427

Frenzel, F. (2020). Touring poverty in townships, inner-city and rural South Africa. In J. M. Rogerson & G. Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies (pp. 167–181). Cham: Springer.

Frenzel, F., & Blakeman, S. (2015). Making slums into attractions: The role of tour guiding in the slum tourism development in Kibera and Dharavi. Tourism Review International, 19 (1–2), 87–100.

Frenzel, F., & Koens, K. (2012). Slum tourism: Developments in a young field interdisciplinary tourism research. Tourism Geographies, 14 (2), 195–212.

Frenzel, F., & Koens, K. (Eds.). (2016). Tourism and geographies of inequality: The new global slumming phenomenon . London: Routledge.

Frenzel, F., Koens, K., & Steinbrink, M. (Eds.). (2012). Slum tourism: Poverty, power and ethics . London: Routledge.

Frenzel, F., Koens, K., Steinbrink, M., & Rogerson, C. M. (2015). Slum tourism: State of the art. Tourism Review International, 18 , 237–252.

Frisch, T. (2012). Glimpses of another world: The favela as a tourist attraction. Tourism Geographies, 14 , 320–338.

Füller, H., & Boris, M. (2014). ‘Stop being a tourist!’ New dynamics of urban tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (4), 1304–1318.

Gálvez, J. C. P., López-Guzmán, T., Buiza, F. C., & Medina-Viruel, M. J. (2017). Gastronomy as an element of attraction in a tourist destination: The case of Lima, Peru. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 4 (4), 254–261.

Gálvez, J. C. P., Gallo, L. S. P., Medina-Viruel, M. J., & López-Guzman, T. (2020). Segmentation of tourists that visit the city of Popayán (Colombia) according to their interest in gastronomy. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology . https://doi.org/10.1080/15428052.2020.1738298 .

George, R., & Booyens, I. (2014). Township tourism demand: Tourists’ perceptions of safety and security. Urban Forum, 25 (4), 449–467.

Ghani, E., & Kanbur, R. (2013). Urbanization and (in) formalization . Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Gladstone, D. (2005). From pilgrimage to package tour: Travel and tourism in the Third World . Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

Gonzalez, S. (2011). Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in motion’: How urban regeneration ‘models’ travel and mutate in the global flows of policy tourism. Urban Studies, 48 (7), 1397–1418.

González-Pérez, J. M. (2020). The dispute over tourist cities: Tourism gentrification in the historic centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tourism Geographies, 22 (1), 171–191.

Gowreesunkar, V. G., Seraphin, H., & Nazimuddin, M. (2020). Beggarism and black market tourism – A case study of the city of Chaar Minaar in Hyderabad (India). International Journal of Tourism Cities . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-12-2019-0210 .

Grant, R. (2015). Africa: Geographies of change . New York: Oxford University Press.

Gravari-Barbas, M., & Guinand, S. (2021). Tourism and gentrification. In A. M. Morrison & J. A. Coca-Stefaniak (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of tourism cities . London: Routledge.

Greenberg, D., & Rogerson, J. M. (2015). The serviced apartment industry of South Africa: A new phenomenon in urban tourism. Urban Forum, 26 , 467–482.

Greenberg, D., & Rogerson, J. M. (2018). Accommodating business travellers: The organisation and spaces of serviced apartments in Cape Town, South Africa. Bulletin of Geography, 42 , 83–97.

Greenberg, D., & Rogerson, J. M. (2019). The serviced apartment sector in the urban global South: Evidence from Johannesburg, South Africa. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 26 (3), 916–929.

Gregory, J. J. (2016). Creative industries and urban regeneration – The Maboneng Precinct, Johannesburg. Local Economy, 31 (1–2), 158–171.

Hall, C. M. (2002). Tourism in capital cities. Tourism – An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 50 (3), 235–248.

Hall, C. M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), 577–598.

Hannam, K., & Zuev, D. (2020). Revisiting the local in Macau under COVID-19. ATLAS Tourism and Leisure Review, 2020-2 , 19–21.

Hayllar, B., & Griffin, T. (2005). The precinct experience: A phenomenological approach. Tourism Management, 26 , 517–528.

Hayllar, B., Griffin, T., & Edwards, D. (Eds.). (2008). City spaces – Tourism spaces: Urban tourism precincts . Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Haywood, K. M. (1992). Identifying and responding to challenges posed by urban tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 17 (2), 9–23.

Heeley, J. (2011). Inside city tourism: A European perspective . Bristol: Channel View.

Henderson, J. (2006). Tourism in Dubai: Overcoming barriers to destination development. International Journal of Tourism Research, 8 , 87–99.

Henderson, J. (2014). Global Gulf cities and tourism: A review of Abu Dhabi, Doha and Dubai. Tourism Recreation Research, 39 (1), 107–114.

Henderson, J. (2015a). The development of tourist destinations in the Gulf: Oman and Qatar compared. Tourism Planning and Development, 12 (3), 350–361.

Henderson, J. (2015b). Destination development and transformation – 50 years of tourism after independence in Singapore. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 1 (4), 269–281.

Hernandez-Garcia, J. (2013). Slum tourism, city branding and social urbanism: The case of Medellin, Colombia. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6 (1), 43–51.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020a). COVID-19 and tourism: Reclaiming tourism as a social force. ATLAS Tourism and Leisure Review, 2020-2 , 65–73.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020b). The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism . https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1803334 .

Hoffman, L. M., Fainstein, S. S., & Judd, D. R. (Eds.). (2003). Cities and visitors: Regulating people, markets and city space . Oxford: Blackwell.

Holst, T. (2015). Touring the demolished slum?: Slum tourism in the face of Delhi’s gentrification. Tourism Review International, 18 , 283–294.

Holst, T. (2018). The affective negotiation of slum tourism: City walks in Delhi . London: Routledge.

Holst, T., Frisch, T., Frenzel, F., Steinbrink, M., & Koens, K. (2017). The complex geographies of inequality in contemporary slum tourism . In Call for papers for the Association of American Geographers Annual Meeting, Boston.

Horner, R., & Carmody, P. (2020). Global North/South. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International encyclopedia of human geography (Vol. 6, 2nd ed., pp. 181–187). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

i Agusti, D. P. (2020). Mapping tourist hot spots in African cities based on Instagram images. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22 (5), 617–626.

Ihalanayake, R. (2009). Awaiting attention: Profiling the domestic tourism sector in Sri Lanka. In S. Singh (Ed.), Domestic tourism in Asia (pp. 253–266). London: Earthscan.

Ioannides, D., & Petridou, E. (2016). Contingent neoliberalism and urban tourism in the United States. In J. Mosedale (Ed.), Neoliberalism and the political economy of tourism (pp. 21–36). Avebury: Ashgate.

Iwanicki, G., & Dłużewska, A. (2015). Potential of city break clubbing tourism in Wroclaw. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series, 28 , 77–89.

Iwanicki, G., Dłużewska, A., & Kay, M. S. (2016). Assessing the level of popularity of European stag tourism destinations. Quaestiones Geographicae, 35 (3), 15–29.

Jaguaribe, B., & Hetherington, K. (2004). Favela tours: Indistinct and maples representations of the real in Rio de Janeiro. In M. Sheller & J. Urry (Eds.), Tourism mobilities: Places to play (pp. 155–166). London: Routledge.

Jamieson, W., & Sunalai, P. (2002). The management of urban tourism destination: The cases of Klong Khwang and Phima, Thailand . Pathumthani, Thailand: Urban Management Programme – Asia Occasional Paper, 56.

Jeffrey, H. L., Vorobjovas-Pinta, O., & Sposato, M. (2017). It takes two to tango: Straight-friendly Buenos Aires. In Critical tourism studies VII conference: Book of abstracts, 25–29 June . Palma de Mallorca, Spain , p. 77.

Joksimović, M., Golic, R., Vujadinović, S., Sabić, D., Popović, D. J., & Barnfield, G. (2014). Restoring tourism flows and regenerating city’s image: The case of Belgrade. Current Issues in Tourism, 17 (3), 220–233.

Jones, G. A., & Sanyal, R. (2015). Spectacle and suffering: The Mumbai slum as a worlded space. Geoforum, 65 , 431–439.

Jurado, K. C., & Matovelle, P. T. (2019). Assessment of tourist security in Quito city through importance-performance analysis. Tourism – An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 67 (1), 73–86.

Kaczmarek, S. (2018). Ruinisation and regeneration in the tourism space of Havana. Turyzm, 28 (2), 7–14.

Kadar, B. (2013). Differences in the spatial patterns of urban tourism in Vienna and Prague. Urbani izziv, 24 (2), 96–111.

Kalandides, A. (2011). City marketing for Bogotá: A case study in integrated place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4 (3), 282–291.

Kamete, A. Y. (2013). On handling urban informality in southern Africa. Geografiska Annaler Series B, 95 , 17–31.

Kanai, M. (2014). Buenos Aires, capital of tango: Tourism, redevelopment and the cultural politics of neoliberal urbanism. Urban Geography, 35 (8), 1111–1117.

Karski, A. (1990). Urban tourism – A key to urban regeneration. The Planner, 76 (13), 15–17.

Kaushal, V., & Yadav, R. (2020). Understanding customer experience of culinary tourism through food tours of Delhi. International Journal of Tourism Cities . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2019-0135 .

Ketter, E. (2020). Millennial travel: Tourism micro-trends of European Generation Y. Journal of Tourism Futures . https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2019-0106 .

Khoo, S. L., & Badarulzaman, N. (2014). Factors determining George Town as a city of gastronomy. Tourism Planning & Development, 11 (4), 371–386.

Khusnutdinova, S. R., Sadretdinov, D. F., & Khusnutdinov, R. R. (2019). Tourism as a factor of city development in the post-industrial economy. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 131 , 886–890.

Kieti, D. M., & Magio, K. O. (2013). The ethical and local resident perspectives of slum tourism in Kenya. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 1 (1), 37–57.

Koens, K., & Thomas, R. (2015). Is small beautiful? Understanding the contribution of small businesses in township tourism to economic development. Development Southern Africa, 32 (3), 320–332.

Koens, K., Postma, A., & Papp, B. (2018). Is overtourism overused?: Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability, 10 (12), 4384.

Komaladewi, R., Mulyana, A., & Jatnika, D. (2017). The representation of culinary experience as the future of Indonesian tourism cases in Bandung city, West Java. International Journal of Business and Economic Affairs, 2 (5), 268–275.

Korstanje, M. E., & Baker, D. (2018). Politics of dark tourism: The case of Cromanon and ESMA, Buenos Aires, Argentina. In P. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), Handbook of dark tourism (pp. 533–552). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kotus, J., Rzeszewski, M., & Ewertowski, W. (2015). Tourists in the spatial structures of a big Polish city: Development of an uncontrolled patchwork or concentric spheres? Tourism Management, 50 , 98–110.

Ladkin, A., & Bertramini, A. M. (2002). Collaborative tourism planning: A case study of Cusco, Peru. Current Issues in Tourism, 5 (2), 71–93.

Larsen, J. (2020). Ordinary tourism and extraordinary everyday life: Re-thinking tourism and cities. In T. Frisch, C. Sommer, L. Stoltenberg, & N. Stors (Eds.), Tourism and everyday life in the contemporary city . London: Routledge.

Law, C. M. (1992). Urban tourism and its contribution to economic regeneration. Urban Studies, 29 , 599–618.

Law, C. M. (1993). Urban tourism: Attracting visitors to large cities . London: Mansell.

Law, C. M. (1996). Introduction. In C. M. Law (Ed.), Tourism in major cities (pp. 1–22). London: International Thomson Business Press.

Lee, J. (2008). Riad fever: Heritage tourism, urban renewal and the medina property boom in old cities of Morocco. E Review of Tourism Research, 6 , 66–78.

Leonard, L., Musavengane, R., & Siakweh, P. (Eds.). (2021). Sustainable urban tourism in sub-Saharan Africa . London: Routledge.

Lertwannawit, A., & Gulid, N. (2011). International tourists service quality perception and behavioral loyalty toward medical tourism in Bangkok metropolitan area. Journal of Applied Business Research, 27 (6), 1–12.

Li, J., Pearce, P. L., Morrison, A. M., & Wu, B. (2016). Up in smoke?: The impact of smog on risk perception and satisfaction of international tourists in Beijing. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18 (4), 373–386.

Li, M., & Wu, B. (2013). Urban tourism in China . London: Routledge.

Liu, L., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., & Ling, R. S. J. (2015). Why dwell in a hutongtel?: Tourist accommodation preferences and guest segmentation for Beijing hutongtels. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17 (2), 171–184.

Loazya, N. V. (2016). Informality in the process of development and growth. The World Economy, 39 (12), 1856–1916.

Lunchaprasith, T. (2017). Gastronomic experience as a community development driver: The study of Amphawa floating market as community-based culinary tourism destination. Asian Journal of Tourism Research, 2 (2), 84–116.

Ma, B. (2010). A trip into the controversy: A study of slum tourism travel motivations . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Mahler, A. G. (2018). From the tricontinental to the global South: Race, radicalism and transnational solidarity . Durham: Duke University Press.

Maitland, R. (2012a). Global change and tourism in national capitals. Current Issues in Tourism, 15 (1–2), 1–2.

Maitland, R. (2012b). Capitalness is contingent: Tourism and national capitals in a globalised world. Current Issues in Tourism, 15 (1–2), 3–17.

Maitland, R. (2016). Everyday tourism in a world tourism city: Getting backstage in London. Asian Journal of Behavioural Studies, 1 (1), 13–20.

Maitland, R., & Newman, P. (2009). Developing world tourism cities. In R. Maitland & P. Newman (Eds.), World tourism cities: Developing tourism off the beaten track (pp. 1–21). London: Routledge.

Maitland, R., & Ritchie, B. W. (Eds.). (2009). City tourism: National capital perspectives . Wallingford: CABI.

Mbaiwa, J. E., Toteng, E. N., & Moswete, N. (2007). Problems and prospects for the development of urban tourism in Gaborone and Maun. Development Southern Africa, 24 , 725–739.

Mbatia, T. W., & Owuor, S. (2014). Prospects for urban eco-tourism in Nairobi, Kenya: Experiences from the Karura forest reserve. African Journal of Sustainable Development, 4 (3), 184–198.

McGehee, N. G., & Andereck, K. (2009). Volunteer tourism and the “voluntoured”: The case of Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17 (1), 39–51.

McKay, T. (2013). Leaping into urban adventure: Orlando bungee, Soweto, South Africa. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 18 (Supplement), 55–71.

McKay, T. (2017). The South African adventure tourism economy: An urban phenomenon. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series, 37 , 63–76.

McKay, T. (2020). Locating great white shark tourism in Gansbaai, South Africa within the global shark tourism economy. In J. M. Rogerson & G. Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies (pp. 283–297). Cham: Springer.

Mekawy, M. A. (2012). Responsible slum tourism: Egyptian experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 39 (4), 2092–2113.

Mendoza, C. (2013). Beyond sex tourism: Gay tourists and male sex workers in Puerto Vallarta (Western Mexico). International Journal of Tourism Research, 15 (2), 122–137.

Mikulić, D., & Petrić, L. (2014). Can culture and tourism be the foothold of urban regeneration?: A Croatian case study. Tourism – An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 62 (4), 377–395.

Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27 (12), 1857–1875.

Miller, D., Merrilees, B., & Coghlan, A. (2015). Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23 (1), 26–46.

Miraftab, F., & Kudva, N. (Eds.). (2015). Cities of the global South reader . London: Routledge.

Mitchell, J., & Ashley, C. (2010). Tourism and poverty reduction: Pathways to prosperity . London: Earthscan.

Mogaka, J. J. O., Mupara, L. M., Mashamba-Thompson, T. P., & Tsoka-Gwegweni, J. M. (2017). Geo-location and range of medical tourism services in Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6 (1), 1–18.

Montes, G. C., & de Pinho Bernabé, S. (2020). The impact of violence on tourism to Rio de Janeiro. International Journal of Social Economics, 47 (4), 425–443.

Moreno-Gil, S., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2020). Guest editorial. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6 (1), 1–7.

Morrison, A. M., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (Eds.). (2021). The Routledge handbook of tourism cities . London: Routledge.

Muldoon, M., & Mair, H. (2016). Blogging slum tourism: A critical discourse analysis of travel blogs. Tourism Analysis, 21 (5), 465–479.

Műller, M. (2020). In search of the global East: Thinking between North and South. Geopolitics, 25 (3), 734–755.

Murillo, J., Vaya, E., Romani, J., & Surinach, J. (2011). How important to a city are tourists and daytrippers?: The economic impact of tourism on the city of Barcelona . Barcelona: University of Barcelona, Research Institute of Applied Economics.

Musavengane, R., Siakweh, P., & Leonard, L. (2020). The nexus between tourism and urban risk: Towards inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable outdoor tourism in African cities. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 29 , 100254.

Myers, G. (2020). Rethinking urbanism: Lessons from postcolonialism and the global South . Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Naicker, M. S., & Rogerson, J. M. (2017). Urban food markets: A new leisure phenomenon in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6 (3), 1–17.

Niewiadomski, P. (2020). COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a rediscovery of tourism? Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), 651–656.

Nisbett, M. (2017). Empowering the empowered?: Slum tourism and the depoliticization of poverty. Geoforum, 85 , 37–45.

Nobre, E. A. C. (2002). Urban regeneration experiences in Brazil: Historical preservation, tourism development and gentrification in Salvador da Bahia. Urban Design International, 7 , 109–124.

Novy, J. (2011). Marketing marginalized neighbourhoods: Tourism and leisure in the 21 st century inner city . PhD dissertation, Columbia University, New York.

Novy, J., & Colomb, C. (2019). Urban tourism as a source of contention and social mobilisations: A critical review. Tourism Planning and Development, 16 (4), 358–375.

Nyerere, V. C. Y., Ngaruko, D., & Mlozi, S. (2020). The mediating role of strategic planning on the determinants of sustainable urban tourism: Empirical evidence from Tanzania. African Journal of Economic Review, 8 (1), 198–216.

OECD. (2020). Rebuilding tourism for the future: COVID-19 policy response and recovery . Paris: OECD.

Oldfield, S., & Parnell, S. (2014). From the South. In S. Parnell & S. Oldfield (Eds.), The Routledge handbook on cities of the global South (pp. 1–4). London: Routledge.

Opfermann, L. S. (2020). Walking in Jozi: Guided tours, insecurity and urban regeneration in inner city Johannesburg. Global Policy . https://doi.org/10.1011/1758-5899.12809 .

Oppermann, M., Din, K. H., & Amri, S. Z. (1996). Urban hotel location and evolution in a developing country: The case of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Tourism Recreation Research, 2 , 55–63.

Page, S. J., & Connell, J. (2006). Tourism: A modern synthesis . London: Thomson Press.

Panasiuk, A. (2019). Crises in the functioning of urban tourism destinations. Studia Periegetica, 27 (3), 13–25.

Pandy, W. R., & Rogerson, C. M. (2019). Urban tourism and climate change: Risk perceptions of business tourism stakeholders in Johannesburg, South Africa. Urbani izziv, 30 (Supplement), 225–243.

Park, J., Wu, B., Shen, Y., Morrison, A. M., & Kong, Y. (2014). The great halls of China?: Meeting planners’ perceptions of Beijing as an international convention destination. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 15 (4), 244–270.

Parnell, S., & Oldfield, S. (Eds.). (2014). The Routledge handbook on cities of the global South . London: Routledge.

Parnell, S., & Pieterse, E. (Eds.). (2014). Africa’s urban revolutions . London: Zed.

Parvin, M., Razavian, M. T., & Tavakolinia, J. (2020). Importance of urban tourism planning in Tehran with economic approach. Iranian Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8 (4), 95–110.

Pasquinelli, C. (2015). Urban tourism(s): Is there a case for a paradigm shift? (Cities research unit working papers no. 14). L’ Aquila: Gran Sasso Science Institute.

Pasquinelli, C., & Bellini, N. (2017). Global context, policies and practices in urban tourism: An introduction. In N. Bellini & C. Pasquinelli (Eds.), Tourism in the city: Towards an integrative agenda on urban tourism (pp. 1–25). Dordrecht: Springer.

Pasquinelli, C., & Trunfio, M. (2020a). Overtouristified cities: An online news media narrative analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28 (11), 1805–1824.

Pasquinelli, C., & Trunfio, M. (2020b). Reframing overtourism through the smart city lens. Cities, 102 (July), 102729.

Pearce, D. (2015). Urban management, destination management and urban destination management: A comparative review with issues and examples from New Zealand. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 1 (1), 1–17.

Pechlaner, H., Innerhofer, E., & Erschbamer, G. (Eds.). (2020). Overtourism: Tourism management and solutions . London: Routledge.

Pike, A., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2014). Local and regional development in the global North and South. Progress in Development Studies, 14 (1), 21–30.

Pinke-Sziva, I., Smith, M., Olt, G., & Berezvai, Z. (2019). Overtourism and the night-time economy: A case study of Budapest. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5 (1), 1–6.

Pophiwa, N. (2020). Shopping-oriented mobility across the Zimbabwe-South Africa border: Modalities and encounters. In C. Nshimbi & I. Moyo (Eds.), Borders, mobility, regional integration and development (pp. 65–83). Cham: Springer.

Postma, A., Buda, D.-M., & Gugerell, K. (2017). Editorial. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3 (2), 95–101.

Pu, B., Teah, M., & Phau, I. (2019). Hot chilli peppers, tears and sweat: How experiencing Sichuan cuisine will influence intention to visit city of origin. Sustainability, 11 (13), 3561.

Rabbiosi, C. (2016). Developing participatory tourism in Milan, Italy: A critical analysis of two case studies. Via@Tourism Review, 1 (9), 2–16.

Richards, G. (2014). Creativity and tourism in the city. Current Issues in Tourism, 17 (2), 119–144.

Richards, G. (2020). Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 85 , 102922.

Richards, G., & Roariu, I. (2015). Developing the eventful city in Sibiu, Romania. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 1 (2), 89–102.

Rink, B. (2013). Que(e)rying Cape Town: Touring Africa’s ‘gay capital’ with the Pink Map . In J. Sarmento & E. Brito-Henriques (Eds.), Tourism in the global South: Heritages, identities and development (pp. 65–90). Lisbon: Centre for Geographical Studies, University of Lisbon.

Rink, B. (2020). Cruising nowhere: A South African contribution to cruise tourism. In J. M. Rogerson & G. Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies (pp. 249–266). Cham: Springer.

Rockefeller Foundation. (2009). Century of the city . Washington, DC: The Rockefeller Foundation.

Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, P., Cruz, F. G. S., Gallo, S. M. P., & López-Guzmán, T. (2020). Gastronomic satisfaction of the tourist: Empirical study in the creative city of Popayán, Colombia. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 7 , 8.

Rogerson, C. M. (1997). Globalization or informalization?: African urban economies in the 1990s. In C. Rakodi (Ed.), Managing urban growth in Africa (pp. 337–370). Tokyo: The United Nations University Press.

Rogerson, C. M. (2002a). Tourism-led local economic development: The South African experience. Urban Forum, 13 , 95–119.

Rogerson, C. M. (2002b). Urban tourism in the developing world: The case of Johannesburg. Development Southern Africa, 19 , 169–190.

Rogerson, C. M. (2004). Urban tourism and small tourism enterprise development in Johannesburg: The case of township tourism. GeoJournal, 60 , 249–257.

Rogerson, C. M. (2006). Creative industries and urban tourism: South African perspectives. Urban Forum, 17 , 149–166.

Rogerson, C. M. (2013). Urban tourism, economic regeneration and inclusion: Evidence from South Africa. Local Economy, 28 (2), 186–200.

Rogerson, C. M. (2015a). Unpacking business tourism mobilities in sub-Saharan Africa. Current Issues in Tourism, 18 (1), 44–56.

Rogerson, C. M. (2015b). Revisiting VFR tourism in South Africa. South African Geographical Journal, 97 (2), 183–202.

Rogerson, C. M. (2016a). Outside the cities: Tourism pathways in South Africa’s small towns and rural areas. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 5 (3), 1–16.

Rogerson, C. M. (2016b). Secondary cities and tourism: The South African record. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 5 (2), 1–12.

Rogerson, C. M. (2017a). Visiting friends and relatives matters in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6 (3), 1–10.

Rogerson, C. M. (2017b). Unpacking directions and spatial patterns of VFR travel mobilities in the global South: Insights from South Africa. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19 , 466–475.

Rogerson, C. M. (2018a). Informality, migrant entrepreneurs and Cape Town’s inner-city economy. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series, 40 , 157–171.

Rogerson, C. M. (2018b). Informal sector city tourism: Cross border shoppers in Johannesburg. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 22 (2), 372–387.

Rogerson, C. M. (2019). Globalisation, place-based development and tourism. In D. Timothy (Ed.), Handbook of globalisation and tourism (pp. 44–53). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Rogerson, C. M., & Baum, T. (2020). COVID-19 and African tourism research agendas. Development Southern Africa, 37 (5), 727–741.

Rogerson, C. M., & Letsie, T. (2013). Informal sector business tourism in the global South: Evidence from Maseru, Lesotho. Urban Forum, 24 , 485–502.

Rogerson, C. M., & Mthombeni, T. (2015). From slum tourism to slum tourists: Township resident mobilities in South Africa. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 24 (3–4), 319–338.

Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2014). Urban tourism destinations in South Africa: Divergent trajectories 2001–2012. Urbani izziv, 25 (Supplement), S189–S203.

Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2017). City tourism in South Africa: Diversity and change. Tourism Review International, 21 (2), 193–211.

Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2019a). Emergent planning for South Africa’s blue economy: Evidence from coastal and marine tourism. Urbani izziv, 30 (Supplement), 24–36.

Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2019b). Tourism in South Africa’s borderland regions: A spatial view. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 24 (1), 175–188.

Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2020). COVID-19 and tourism spaces of vulnerability in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9 (4), 382–401.

Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2021). City tourism in southern Africa: Progress and issues. In M. Novelli, E. A. Adu-Ampong, & M. A. Ribeiro (Eds.), Routledge handbook of tourism in Africa (pp. 447–458). London: Routledge.

Rogerson, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2018). Tourism for poverty alleviation: Issues and debates in the global South. In C. Cooper, S. Volo, B. Gartner, & N. Scott (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of tourism management: Applications of theories and concepts to tourism (pp. 22–37). London: Sage.

Rogerson, C. M., & Visser, G. (Eds.). (2007). Urban tourism in the developing world: The South African experience . New Brunswick: Transaction Press.

Rogerson, C. M., & Visser, G. (2014). A decade of progress in African urban tourism scholarship. Urban Forum, 25 , 407–417.

Rogerson, J. M. (2012). The changing location of hotels in South Africa’s coastal cities, 1990–2010. Urban Forum, 23 (1), 73–91.

Rogerson, J. M. (2013a). Reconfiguring South Africa’s hotel industry 1990–2010: Structure, segmentation, and spatial transformation. Applied Geography, 36 , 59–68.

Rogerson, J. M. (2013b). The economic geography of South Africa’s hotel industry 1990 to 2010. Urban Forum, 24 (3), 425–446.

Rogerson, J. M. (2014a). Hotel location in Africa’s world class city: The case of Johannesburg, South Africa. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series, 25 , 181–196.

Rogerson, J. M. (2014b). Changing hotel location patterns in Ekurhuleni, South Africa’s industrial workshop. Urbani izziv, 25 (Supplement), S82–S96.

Rogerson, J. M. (2016). Hotel chains of the global South: The internationalization of South African hotel brands. Tourism – An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 64 (4), 445–450.

Rogerson, J. M., & Slater, D. (2014). Urban volunteer tourism: Orphanages in Johannesburg. Urban Forum, 25 , 483–499.

Rogerson, J. M., & Visser, G. (2020). Recent trends in South African tourism geographies. In J. M. Rogerson & G. Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies (pp. 1–14). Cham: Springer.

Rogerson, J. M., & Wolfaardt, Z. (2015). Wedding tourism in South Africa: An exploratory analysis. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 4 (2), 1–13.

Rohr, E. (1997). Planning for sustainable tourism in old Havana, Cuba . MA dissertation, Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada.

Rolfes, M. (2010). Poverty tourism: Theoretical reflections and empirical findings regarding an extraordinary form of tourism. GeoJournal, 75 (5), 421–442.

Rolfes, M., Steinbrink, M., & Uhl, C. (2009). Townships as attraction: An empirical study of township tourism in Cape Town . Potsdam: University of Potsdam.

Rowe, D., & Stevenson, D. (1994). ‘Provincial paradise’: Urban tourism and city imaging outside the metropolis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, 30 , 178–193.

Rudsari, S. M. M., & Gharibi, N. (2019). Host-guest attitudes toward socio-cultural carrying capacity of urban tourism in Chalus, Mazandaran. Iranian Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7 (4), 31–47.

Russo, A. P. (2020). After overtourism?: Discursive lock-ins and the future of (tourist) places. ATLAS Tourism and Leisure Review, 2020-2 , 74–79.

Saghir, J., & Santoro, J. (2018). Urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa: Meeting challenges by bridging stakeholders . Washington, DC: Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

Sarmento, J. (2010). Fort Jesus: Guiding the past and contesting the present in Kenya. Tourism Geographies, 12 (2), 246–263.

Scarpaci, J. L., Jr. (2000). Winners and losers in restoring old Havana. Cuba in Transition, 10 , 289–299.

Schettini, M. G., & Troncoso, C. A. (2011). Tourism and cultural identity: Promoting Buenos Aires as the cultural capital of Latin America. Catalan Journal of Communication and Cultural Studies, 3 (2), 195–209.

Šegota, T., Sigala, M., Gretzel, U., Day, J., Kokkranikal, J., Smith, M., Seabra, C., Pearce, P., Davidson, R., van Zyl, C., Newsome, D., Hardcastle, J., & Rakić, T. (2019). Editorial. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5 (2), 109–123.

Seok, H., Joo, Y., & Nam, Y. (2020). An analysis of sustainable tourism value of graffiti tours through social media: Focusing on TripAdvisor reviews of graffiti tours in Bogota, Colombia. Sustainability, 12 (11), 4426.

Seraphin, H., Sheeran, P., & Pilato, M. (2018). Overtourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9 , 374–376.

Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28 (11), 1932–1946.

Shinde, K. (2020). The spatial practice of religious tourism in India: A destinations perspective. Tourism Geographies . https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1819400 .

Shoval, N., McKercher, B., Ng, E., & Birenboim, A. (2011). Hotel location and tourist activity in cities. Annals of Tourism Research, 38 (4), 1594–1612.

Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117 , 312–321.

Sima, C. (2013). Post-communist capital city tourism representation: A case-study on Bucharest . PhD Dissertation, London: University of Westminster.

Singh, S. (1992). Urban development and tourism: Case of Lucknow, India. Tourism Recreation Research, 17 (2), 71–78.

Singh, S. (2004). Religion, heritage and travel: Case references from the Hindu Himalayas. Current Issues in Tourism, 7 (1), 44–65.

Smith, A., & Graham, A. (Eds.). (2019). Destination London: The expansion of the visitor economy . London: University of Westminster Press.

Somnuxpong, S. (2020). Chiang Mai: A creative city using creative tourism management. Journal of Urban Culture Research, 20 , 112–132.

Speakman, M. (2019). Dark tourism consumption in Mexico City: A new perspective of the thanatological experience. Journal of Tourism Analysis, 26 (2), 152–168.

Spirou, C. (2021). Tourism cities in the United States. In A. M. Morrison & J. A. Coca-Stefaniak (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of tourism cities . London: Routledge.

Spirou, C., & Judd, D. R. (2014). The changing geography of urban tourism: Will the center hold? disP – The Planning Review, 50 (2), 38–47.

Spirou, C., & Judd, D. R. (2019). Tourist city. In A. M. Orum (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of urban and regional studies . Wiley, online library collection.

Steck, J.-F., Didier, S., Morange, M., & Rubin, M. (2013). Informality, public space and urban governance: An approach through street trading (Abidjan, Cape Town, Johannesburg, Lomé and Nairobi). In S. Bekker & L. Fourchard (Eds.), Politics and policies governing cities in Africa (pp. 145–167). Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Steel, G. (2013). Mining and tourism: Urban transformations in the intermediate cities of Cajamarca and Cusco, Peru. Latin American Perspectives, 40 (2), 237–249.

Steinbrink, M. (2012). ‘We did the slum!’ – Urban poverty tourism in historical perspective. Tourism Geographies, 14 (2), 213–234.

Steinbrink, M. (2013). Festifavelisation: Mega-events, slums and strategic city staging – The example of Rio de Janeiro. Die Erde, 144 (2), 129–145.

Stepchenkova, S., Rykhtik, M. I., Schichkova, E., Kim, H., & Petrova, O. (2015). Segmentation for urban destination: Gender, place of residence, and trip purpose: A case of Nizhni Novgorod, Russia. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 1 (1), 70–86.

Stephenson, M. L., & Dobson, G. J. (2020). Deciphering the development of smart and sustainable tourism cities in Southeast Asia: A call for research. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 13 (1), 143–153.

Su, M. M., & Wall, G. (2015). Community involvement at Great Wall world heritage sites, Beijing, China. Current Issues in Tourism, 18 (2), 137–157.

Taherkhani, M., & Farahani, H. (2019). Evaluating and prioritizing urban tourism capabilities in Qazvin. Iranian Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8 (1), 71–85.

Tichaawa, T. (2017). Business tourism in Africa: The case of Cameroon. Tourism Review International, 21 (2), 181–192.

Trupp, A., & Sunanata, S. (2017). Gendered practices in urban ethnic tourism in Thailand. Annals of Tourism Research, 64 , 76–86.

Tzanelli, R. (2018). Slum tourism: A review of state-of-the-art scholarship. Tourism, Culture and Communication, 18 , 149–155.

Uansa-ard, S., & Binprathan, A. (2018). Creating an awareness of halal MICE tourism business in Chiang Mai, Thailand. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 8 (3), 203–213.

Ukah, A. (2016). Building God’s city: The political economy of prayer camps in Nigeria. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40 , 524–540.

Ukah, A. (2018). Emplacing God: The social worlds of miracle cities – Perspectives from Nigeria and Uganda. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 36 (3), 351–368.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme, & Economic Commission for Africa. (2015). Towards an African urban agenda . Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

UNWTO. (2012). Global report on city tourism – Cities 2012 project . Madrid: UNWTO.

van der Merwe, C. D. (2013). The limits of urban heritage tourism in South Africa: The case of Constitution Hill, Johannesburg. Urban Forum, 24 , 573–588.

van der Merwe, C. D., & Rogerson, C. M. (2013). Industrial heritage tourism at ‘The big hole’, Kimberley, South Africa. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 19 (Supplement 2), 155–171.

van der Merwe, C. D., & Rogerson, C. M. (2018). The local development challenges of industrial heritage tourism in the developing world: Evidence from Cullinan, South Africa. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 21 (1), 186–199.

Vandermey, A. (1984). Assessing the importance of urban tourism: Conceptual and measurement issues. Tourism Management, 5 (2), 123–155.

Visser, G. (2002). Gay tourism in South Africa: Issues from the Cape Town experience. Urban Forum, 13 (1), 85–94.

Visser, G. (2003). Gay men, tourism and urban space: Reflections on Africa’s ‘gay capital’. Tourism Geographies, 5 (2), 168–189.

Völkening, N., Benz, A., & Schmidt, M. (2019). International tourism and urban transformation in old Havana. Erdkunde, 73 (2), 83–96.

Wang, F., Lu, L., Xu, L., Wu, B., & Wu, Y. (2020). Alike but different: Four ancient capitals in China and their destination images. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6 (2), 415–429.

Winter, T. (2009). Asian tourism and the retreat of Anglo-Western centrism in tourism theory. Current Issues in Tourism, 12 , 21–31.

Wonders, N. A., & Michalowski, R. (2001). Bodies, borders, and sex tourism in a globalized world: A tale of two cities – Amsterdam and Havana. Social Problems, 48 (4), 545–571.

Wu, B., Liu, L., Shao, J., & Morrison, A. M. (2015). The evolution and space patterns of hutongels in Beijing historic districts. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 10 (2), 129–150.

Wu, B., Li, Q., Ma, F., & Wang, T. (2021). Tourism cities in China. In A. M. Morrison & J. A. Coca-Stefaniak (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of tourism cities . London: Routledge.

Xiao, G., & Wall, G. (2009). Urban tourism in Dalian, China. Anatolia, 20 (1), 178–195.

Yang, Y., Wong, K. K. F., & Wang, T. (2012). How do hotels choose their location?: Evidence from hotels in Beijing. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31 , 675–685.

Yin, N. L. (2014). Decision factors in medical tourism: Evidence from Burmese visitors to a hospital in Bangkok. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 6 (2), 84–94.

Ziaee, M., & Amiri, S. (2018). Islamic tourism pilgrimages in Iran: Challenges and perspectives. In S. Seyfi & C. M. Hall (Eds.), Tourism in Iran: Challenges, development and opportunities . London: Routledge.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Thanks to comments received from two reviewers which influenced the final revision of this chapter. Arno Booyzen produced the accompanying maps. Dawn and Skye Norfolk assisted the writing process.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Tourism & Hospitality, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Christian M. Rogerson & Jayne M. Rogerson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christian M. Rogerson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Christian M. Rogerson

Jayne M. Rogerson

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Rogerson, C.M., Rogerson, J.M. (2021). The Other Half of Urban Tourism: Research Directions in the Global South. In: Rogerson, C.M., Rogerson, J.M. (eds) Urban Tourism in the Global South. GeoJournal Library(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71547-2_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71547-2_1

Published : 14 July 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-71546-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-71547-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences History (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A framework of tourist attraction research

- Geography, Planning, and Recreation

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

Although tourist attractions are fundamental to the very existence of tourism, there have been few attemps to come to terms with the breadth of approaches that have been employed in their study. An examination of research methods used in the study of tourist attractions and the tourist attractiveness of places reveals that most studies can be classified into one or more of three general perspectives: the ideographic listing, the organization, and the tourist cognition of attractions. Each of these perspectives shares a distinct set of questions concerning the nature of the attractions, as expressed through the typologies used in their evaluation. At the same time, all three perspectives make comparisons based on the historical, locational, and various valuational aspects of attractions. This framework can be applied in the comparison and evaluation of tourist attraction related research.

- research evaluation

- research methods

- tourist attraction

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- Development

- Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management

Access to Document

- 10.1016/0160-7383(87)90071-5

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

Fingerprint

- tourist attraction Earth & Environmental Sciences 100%

- Tourist Attractions Business & Economics 89%

- tourist Social Sciences 67%

- Attraction Business & Economics 67%

- Tourist Cognition Business & Economics 47%

- cognition Earth & Environmental Sciences 27%

- research method Earth & Environmental Sciences 26%

- Evaluation Business & Economics 26%

T1 - A framework of tourist attraction research

AU - Lew, Alan A.

N2 - Although tourist attractions are fundamental to the very existence of tourism, there have been few attemps to come to terms with the breadth of approaches that have been employed in their study. An examination of research methods used in the study of tourist attractions and the tourist attractiveness of places reveals that most studies can be classified into one or more of three general perspectives: the ideographic listing, the organization, and the tourist cognition of attractions. Each of these perspectives shares a distinct set of questions concerning the nature of the attractions, as expressed through the typologies used in their evaluation. At the same time, all three perspectives make comparisons based on the historical, locational, and various valuational aspects of attractions. This framework can be applied in the comparison and evaluation of tourist attraction related research.

AB - Although tourist attractions are fundamental to the very existence of tourism, there have been few attemps to come to terms with the breadth of approaches that have been employed in their study. An examination of research methods used in the study of tourist attractions and the tourist attractiveness of places reveals that most studies can be classified into one or more of three general perspectives: the ideographic listing, the organization, and the tourist cognition of attractions. Each of these perspectives shares a distinct set of questions concerning the nature of the attractions, as expressed through the typologies used in their evaluation. At the same time, all three perspectives make comparisons based on the historical, locational, and various valuational aspects of attractions. This framework can be applied in the comparison and evaluation of tourist attraction related research.

KW - research evaluation

KW - research methods

KW - tourist attraction

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=0023468715&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=0023468715&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/0160-7383(87)90071-5

DO - 10.1016/0160-7383(87)90071-5

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:0023468715

SN - 0160-7383

JO - Annals of Tourism Research

JF - Annals of Tourism Research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 April 2024

The soundscape and tourism experience in rural destinations: an empirical investigation from Shawan Ancient Town

- Wenxi (Bella) Bai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2004-7258 1 ,

- Jiaojiao (Jane) Wang 1 ,

- Jose Weng Chou Wong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3557-1829 1 ,

- Xingyu (Hilary) Han 1 &

- Yiqing Guo 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 492 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

318 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

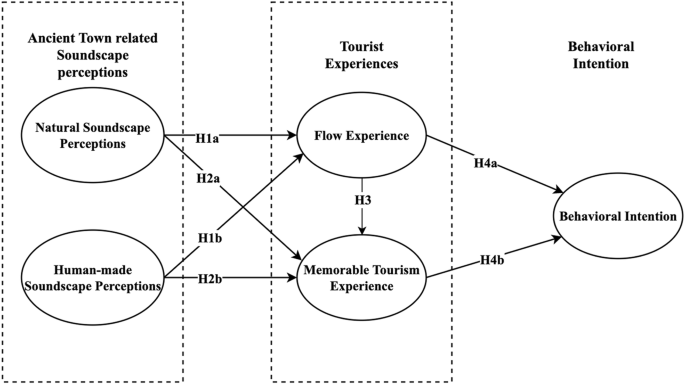

Rural tourism is becoming more valued by different tourist destinations along with the expansion of its market, especially, ancient town tourism, as one of the special rural tourism destinations, has become popular in recent years. This study aims to take Shawan ancient town as a case to comprehend the role of soundscape perceptions in affecting both flow experience and memorable tourism experience and further influence future behavioral intentions. The method of systematic sampling was performed, and finally, 394 samples were retained for further PLS-SEM analysis. The results show that both natural soundscape perceptions and human-made soundscape perceptions have significant effects on flow experience and memorable tourism experience, and natural soundscape perceptions have a stronger effect on tourism experience. In addition, both flow experience and memorable tourism experience were found to influence behavioral intention positively, and flow experience shows the stronger impact. Findings provide managerial implications suggesting that destination managers should cleverly integrate natural soundscape elements into the design of ancient towns and reduce interference from human-made soundscapes. Additionally, practical implications are provided for destination managers in designing soundscapes in the ancient town.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of ecological presence in virtual reality tourism on enhancing tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior

Zhen Su, Biman Lei, … Xijing Zhang

Research on key acoustic characteristics of soundscapes of the classical Chinese gardens

Wei Chen & Juanjuan Liu

Fado, urban popular song, and intangible heritage: perceptions of authenticity and emotions in TripAdvisor reviews

Inês Carvalho, Arlindo Madeira, … Teresa Palrão

Introduction

Rural tourism, often referred to as countryside or agritourism tourism, is popular worldwide (Lane 1994 ). According to the report from Future Market Insights (FMI 2023 ), the global rural tourism market will reach US$ 102.7 billion in 2023, and it can realize a steady 6.8% compound growth rate in the next decade. Rural tourists are increasingly seeking immersive experiences, a connection with nature, and an escape from the hectic urban life (Chen et al. 2023 ; Yildirim and Arefi 2022 ). As one special type of rural tourism, ancient town attractions offer a unique proposition (Su 2010 ). Ancient towns, as a continuum sitting on a spectrum from rural to urban areas that are characterized by rural functions (such as traditional, locally based, authentic, remote, and sparsely populated), provide the ideal backdrop for modern tourists (Lane 1994 ; Rosalina et al. 2021 ). As Orbasli ( 2002 ) underlined, ancient towns are traditionally dated back centuries, their rich historical heritage and picturesque settings are found to offer a stark contrast to the modernized and urbanized world. And these reasons contribute to the preference for ancient towns among rural tourists (Gao and Wu 2017 ). Therefore, rural tourism research, especially the ancient town as a specific tourism destination, has become an important destination topic that cannot be overlooked. Notably, as the popularity of ancient town tourism grows, there is a greater emphasis on its development trends, such as sustainable practices and collaborative conservation (Lane and Kastenholz 2015 ).

In research on rural experiences, sensory-related attractions are considered essential resources for a destination, and these sensory landscapes serve as important mediums for tourists to perceive the place (Agapito et al. 2014 ). Hence, more scholars have attempted to study the dimensions of sensescape in the tourism experience (Wong and Lai 2024 ). For example, previous studies concerned the impact of landscape and heritage buildings on the tourism experience in the ancient town (Fatimah 2015 ; Zhang et al. 2021 ). However, as Carneiro et al. ( 2015 ) argued, there is a large and complex group of non-visual elements that can stimulate tourist perception in rural destinations, and soundscape is one of the most important factors. Soundscape, introduced by Schafer in 1997, can be thought of as an auditory landscape. In the context of ancient towns, soundscapes refer to the collection of sounds in the area, encompassing both natural (e.g., rustling of leaves, chirping of birds) and human-made sounds (e.g., tolling of historic bells, traditional music) (Chen et al. 2021 ). These sounds not only contribute to a sense of serenity and harmony with nature but also reflect the daily lives and historical traditions of the local communities (Jiang et al. 2020 ; Mao et al. 2022 ). Hence, ancient town tourists are drawn to these tranquil and cultural soundscapes. Practically, destination stakeholders attach great importance to ancient town tourism and continuously in the preservation and enhancement of soundscapes (e.g., sound art installation and digital interpretation) (Qiu et al. 2018 ). These practices are designed to maintain the authenticity of these destinations and attract rural tourists seeking a connection with tradition and nature (Zhao and Li 2023 ).