Latest Stories

Today's picks.

- History & Culture

- Environment

- Gory Details

- Photographer

Discover More on Disney+

- Queens with Angela Bassett

- Arctic Ascent with Alex Honnold

- The Space Race

- Genius: MLK/X

- A Real Bug's Life with Awkwafina

- Incredible Animal Journeys with Jeremy Renner

- TheMissionKeyArtDisneyPlusCard

- Animals Up Close with Bertie Gregory

- Secrets of the Elephants

- The Territory

- Never Say Never with Jeff Jenkins

- Extraordinary Birder with Christian Cooper

- A Small Light

Port Protection Alaska

Wicked tuna.

- Paid Content

April 2024 Issue

In this issue.

- Photography

The National Geographic Society Mission

National geographic’s nonprofit work.

The National Geographic Society invests in innovative leaders in science, exploration, education and storytelling to illuminate and protect the wonder of our world.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

"I'm a trans woman – this is what I've learnt so far"

From an uplifting queer community to (at times) crushing gender dysphoria, my transition has been full of ups and downs. These are pieces of wisdom I wish I'd known earlier on in my journey

This will be my 14th trip to 2Pass as a trans woman . There, I will submit myself to a session of electrolysis, a form of permanent hair removal that involves eight hours of my face being injected with lidocaine, before each individual hair follicle is electrocuted with a fine metal probe. And yes, the experience is as delightful as it sounds. I will emerge swollen – so cartoonishly swollen, in fact, that the clinic will provide me with a letter to present to the passport control officers at Brussels station, in order to explain the visual discrepancy between my passport photo and the person before them, who will look more like Shrek than me.

It makes for a fairly traumatising experience – but it’s my only option after two and a half years of limited success with laser hair removal on my fair hair. It turns out that blondes don’t have more fun, they just have more electrolysis. For me, the results are just about worth it so that I can move forward in my transition, which can otherwise feel painfully slow at times. When I first started transitioning years ago, I would never have predicted hair removal would come to dominate my days. I wish someone had told me about the many challenges I’d face – and the many incredible realisations I’d have about myself along the way. Really, hair removal is just the tip of the iceberg.

There are some lessons I would love to have learned earlier – and the six below are probably the most crucial.

1/ Progress isn’t linear

When I first started transitioning, I drew up a roadmap of important milestones I expected to achieve by certain dates. It covered things like switching pronouns, starting hormone replacement therapy, coming out to my employer and going ‘full-time’ (in other words, presenting as a woman day-to-day). Committing this information to writing felt empowering; it gave me a sense of direction and a way to track my progress. Somewhere, at some point along the journey, I thought there would be an ‘Aha!’ moment when everything would just suddenly click into place: womanhood achieved, transition complete. This was admittedly slightly harder to schedule, but I was certain the moment would come, provided I worked hard and hit every target on the roadmap.

Well, guess what? So far, nothing has gone to plan and, on reflection I see how naïve I was to think it could. Transitioning isn’t a paint-by-numbers exercise. My roadmap didn’t account for the possibility of coming up against challenges, setbacks, the occasional need for off-piste travel, or even the simple fact that I might not want to take certain steps at the time I’d previously decreed I would. The reality is that my transition has felt much more like a game of snakes and ladders – three steps forward, two steps back. Some of the procedures I have undertaken to address my gender dysphoria have, frustratingly, only made it worse – at least in the short term (see my Shrek-style experience above). Even the moments when I felt invincible and brimming with self-confidence could quickly collapse into insecurity if I so much as detected a funny look from a stranger. Nothing has felt guaranteed, and I’ve learnt to just roll with the punches.

2/ Self-discovery can be awkward

Remember the makeover montage scenes in early Noughties films, where just removing a pair of glasses or swapping paint overalls for a slip dress would somehow catapult the heroine into social acceptance? There’d be a rock’n’roll soundtrack, maybe a round of high fives. Transitioning isn’t like that: it’s weird and gawky and painfully slow, and mostly just trial-and-error. For me, there were the mullet months, when, in waiting for the sides of my hair to catch up with the back, I unintentionally looked like an extra from Footloose ; there was the whole year it took my non-existent right breast to catch up with my fairly developed left; there was that strange period of androgyny, when I neither resembled a girl nor a boy, and so was misgendered by strangers as frequently as I was gendered correctly. And then there was the irrational dread of travelling under my old passport, and coming face-to-face with a pre-transition me like some unwelcome run-in with an ex.

.css-lt453j{font-family:NewParisTextBook,NewParisTextBook-roboto,NewParisTextBook-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;font-size:1.75rem;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;padding-left:5rem;padding-right:5rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-lt453j{padding-left:2.5rem;padding-right:2.5rem;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-lt453j{font-size:2.5rem;line-height:1.2;}}.css-lt453j b,.css-lt453j strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-lt453j em,.css-lt453j i{font-style:italic;font-family:NewParisTextItalic,NewParisTextItalic-roboto,NewParisTextItalic-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;} "Transitioning isn’t a paint-by-numbers exercise – I've learnt to just roll with the punches"

The thing is – and this really is the thing – with the best will in the world, you still can’t leapfrog the awkward parts of transitioning and skip to the finish line. To be honest, I’m not even sure that finish line even exists, at least not for me – I’ve embraced fridge magnet wisdom, particularly the phrase: “The journey is the destination”. And while it’s so easy, so tempting to focus on the before and after, I’ve found that it’s all the in-between stuff that really matters and has formed the bedrock of my own personal metamorphosis. Those awkward and sometimes ugly bits of self-discovery have empowered me to find a home in my own skin. So, if you can, remember to celebrate all of your gradual changes: month to month you are ushering in a new iteration of yourself, and there’s something quietly magical about that. Don’t miss out. Don’t yearn to skip ahead. All of you is a working title and it’s a privilege to watch yourself grow.

3/ Your community is everything

I cannot overstate the importance of queer friendships and connections. They have been a vital and meaningful reminder of my own humanity, that I am valid, that I belong and that I am heard, particularly at a time when it so often feels like I am still working out who I am. London is buzzing with queer-friendly spaces and I would encourage anyone who is in the infancy of their transition to explore queer culture at its grassroots, if you’re lucky enough to live in the city (or near any city that offers something similar). This could be a queer bar (I am a big fan of Dalston Superstore and The Glory ) or club night (check out Queer Frequencies ) or even a support group (mine was the now-defunct NW Girls).

"My transition has felt like a game of snakes and ladders: three steps forward, two steps back"

Whilst there’s obviously no blueprint for transitioning, social media can be another great resource: a place to feel connected, to gather useful and trustworthy information and to create your own personal support hub. I have loved following Dani St James (who posts uplifting content but never shyes away from discussing the uglier realities of transitioning), Shon Faye (who has made trauma-dumping an art form and, now, my drug of choice) and Charlie Craggs (who has this extraordinary ability to find levity and humour in bleakness and whose book, To My Trans Sisters , is one I’d recommend to everyone). I have found all their accounts informative and genuine; seeing these trans women talk about their experiences in such real and often exposing ways has been an inexpressible source of comfort to me. They’re also hilarious, encouraging and very strong on the meme front.

4/ The desire to ‘pass’ is problematic, but don’t hate yourself for wanting to

To my trans siblings: I get it. The will to ‘pass’. It’s almost unavoidable and, for many of us, it is a suffocating obsession. It can take a lot of work to appreciate that, in fact, there’s beauty in your transness – even when it doesn’t align with conventional aesthetics of cisgender beauty – that offers its own unique affirmation.

To the blissfully unaware: ‘passing’ describes someone who is invisibly trans. So, for example, a trans man is said to ‘pass’ if a stranger assumes he is a cisgender man without so much as a second glance. Passing is not about beauty: it’s about camouflage, blending into the fabric of everyday society without raising an eyebrow or arousing the ‘wrong’ attention. For a minority of trans people, passing is irrelevant. For the vast majority, the desire to pass can at times feel all-consuming and the only metric for judging the success of their transition.

The concept of passing is screwed up, and for so many reasons. It’s screwed up because it turns the lived realities of trans people into performance, some elaborate game of deception. It’s screwed up because it reinforces restrictive and damaging cultural attitudes to gender presentation. It’s screwed up because its empowerment of trans people is built on their very disempowerment – and their complicity in that disempowerment by willingly gatekeeping their own bodies. It’s screwed up because, despite all of these reasons, for so many the allure of passing simply cannot be helped – not when it promises apparent safety and the ability to walk the street without the expectation of discrimination, harassment or even violence along the way.

5/ An open mind can be invaluable

We live in a country in which we are consistently demonised, pathologised, stigmatised and delegitimised by mainstream media outlets. Trans people in the UK are already the group most likely to be the victims of violent crime, and there was a massive 56 per cent increase in hate crimes against trans people last year. What this means is that we move through the world in a state of hypervigilance, constantly assessing risk, judging safety and making snap decisions about how we will be received by strangers.

An unfortunate consequence of this fight-or-flight mentality is that we tend to assume the worst of people and, like a fire curtain, close our minds to people who we suspect will be unsympathetic to us. Yes, some people are assholes. This is an unavoidable fact of life. The vast majority, however, are not – and you’d be surprised at how expansive, compassionate and accepting their minds can be. Don’t let your own expectations of rejection and negative judgement exclude you from spaces that, while unfamiliar or even clumsy with your transness, are nonetheless welcoming of it; you might just find that the people inside those spaces become your unexpected allies.

"I cannot overstate the importance of queer friendships and connections"

The same goes for your existing support networks. Before I formally came out as trans, I lost hours agonising over all the ways my transition would test and disrupt these relationships. That I might lose friends felt a distinct possibility, not (thankfully) for their lack of sympathy but for their fundamental lack of understanding – they just might not ‘get it’, they might never ‘get it’. Many people, as you might expect, struggled with the idea of being born into the wrong body – but inviting them to share in my journey, to experience first-hand its high and lows, has afforded us the most extraordinary kind of renewed closeness.

Asking friends for advice about clothes and make-up (particularly how to do winged eyeliner). Confiding in my brother all my fears and doubts about staying the course. Holding each of my sisters’ hands as I navigate the journey home from Antwerp after yet another electrolysis session that has left me a dysphoric mess. Having my mum not only administer my quarterly hormone injection, but dutifully diarise the next one, and the next, because she knows just how important they are to me. Explaining to my dad why I’ve never been his son – not really, anyway. All of these moments, in their own way, have been profound bonding experiences.

6/ Engaging with hate rarely ends well

Honey, put the keyboard down. Trust me on this, Twitter is not your friend – no good that way lies.

I used to think that it was my duty to wade in on the ‘trans debate’. I’d trawl newspaper columns, the comments section on social media, televised political debates, even radio phone-ins, and be met each time with the same anti-transgender rhetoric. Surely, I thought, if I could just understand their point of view, if I could identify the root cause of their antipathy, I could dismantle it from the inside. But reasoning with trolls is a fool’s errand. Even where it’s possible to have a debate, it becomes a relentless game of whack-a-mole – you think you’ve eliminated one troll, only for five more to pop up in their place. It’s exhausting, demoralising and, in my experience, not even remotely worth it when the inevitable trade-off is your own mental wellbeing.

Now, to be clear, I’m not advocating a life of complete dissociation, nor am I suggesting that there isn’t value in trans activism. I’m saying that if you consistently look for hate, chances are that you will find it. Since opposition is so often louder than support, you might become blinkered to the reality that a lot of people – trans, cis, and everyone in between – are really rooting for you.

Camille Charriere: Female misogyny is a problem

Why are we all so obsessed with reboots?

'One Day' is a milestone for diverse casting

Why an adult all-girls holiday is good for you

The enduring appeal of 'Mean Girls'

FKA Twigs, Calvin Klein and clear double standards

Ayo Edebiri is right – assistants do need thanking

Bows are back in a big way – what does it mean?

How important is relationship chemistry?

Have we forgotten how to relax?

Why you should try drinking mindfully this season

BREAKING: Italian fashion designer Roberto Cavalli dies at 83

10 trans people share how their life satisfaction has changed after transition

Transgender people overwhelmingly describe their lives after transitioning as “happier,” “authentic” and “comforting” despite a deluge of state legislation in recent years that seeks to restrict their access to health care and other aspects of life.

Over the last three years, nearly half of states have passed restrictions on transition-related medical care — such as puberty blockers, hormone therapy and surgery — for minors. Supporters of the legislation have argued that many transgender people later regret their transitions, though studies have found that only about 1%-2% of people who transition experience regret.

Earlier this year, the 2022 U.S. Transgender Survey — the largest nationwide survey of the community, with more than 90,000 trans respondents — found that 94% of respondents reported that they were “a lot more satisfied” or “a little more satisfied” with their lives.

Transgender Day of Visibility, observed on March 31, is an annual awareness day dedicated to celebrating the accomplishments of trans people and acknowledging the violence and discrimination the community faces. NBC News asked transgender people from across the country to share how their life satisfaction has changed after transition. Out of two dozen respondents, all but one said they feel more joy in their lives. Here are some of their stories.

Ash Orr, 33

Morgantown, west virginia.

Orr, who is the press relations manager for the National Center for Transgender Equality, the trans rights advocacy group that conducted the nationwide survey, began socially transitioning in his mid-20s, and at 33, he received gender-affirming top surgery.

“The impact of this surgery … has been life-changing,” Orr said. “My body now feels like a comforting and familiar home, a place I had yearned for and have finally returned to.”

When Orr isn’t working, he loves immersing himself in nature, whether that’s through gardening or playing pickleball with friends. He also chases tornadoes in the Midwest — “Yes, like the movie ‘Twister’!” he said.

“My transition journey has been a profound lesson in self-discovery,” Orr said. “It has shown me that there are countless versions of myself waiting to be unearthed.”

Criss Smith, 63

After transitioning, Smith said he felt a sense of congruence between his internal sense of self and his external presentation.

“I was so broken and uncertain, and now I have a profound sense of relief, empowerment and alignment with how I feel and being the best human possible,” he said. Smith said he worked on Wall Street in financial services for more than 30 years for major companies including Merrill Lynch and JPMorgan Chase. He now works as a substitute teacher for the New York City Department of Education.

“My mind is more at rest and I am at ease with every moment,” Smith said of life after his transition. “A joy fills my soul that I never thought possible before. I am truly living a full human experience presenting all of my authenticity. I live in a liberation garden.”

Gavin Grimm, 24

Hampton roads, virginia.

Grimm was the plaintiff in a landmark 2020 court case in which the 4th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the rights of transgender students to use the school bathrooms that aligned with their gender identities. In 2021, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case and allowed the circuit court’s decision in Grimm’s favor to stand.

Now, nearly three years later, Grimm plans to go back to college to become a middle or high school teacher. He came out and began his transition in 2013, and “to date, I have absolutely zero regrets,” he said.

“While I do still struggle with unrelated strife in my personal life, the ability to be myself fully and completely for the last decade has given me the strength and joy that I have needed to carry on,” Grimm said. “Despite these challenges, I remain very, fundamentally happy. Exquisitely happy, even, in just finding small joy each day in a world where I had the ability to access myself.”

Dani Stewart, 57

Springfield, missouri.

Stewart said transitioning was “a life saver” for her and that she feels more confident than she ever has before.

“I feel like I belong in society,” said Stewart, who said she was formerly a news desk producer at CNN and worked for various TV stations. “However, dark clouds remain for all trans people. We need better and more representation in media. We need to see more of ourselves integrated with the world around us.”

Andrea Montañez, 58

Orlando, florida.

Montañez said her son and her co-workers both observed the same change in her after she transitioned in 2018: They said they noticed her smile.

“You always were a nice person, but we didn’t know you could smile,” Montañez recalled her co-workers telling her. “I lost a lot, but I won freedom and happiness.”

Montañez is the director of advocacy and immigration at the Hope CommUnity Center in Orlando and is involved in advocating against legislation targeting LGBTQ people in Florida — work that she said has helped her build community, find happiness and “bring the magic” to her and others’ lives.

“We are a gift,” she said. “Trans people are a gift.”

Elizabeth ‘Lizzy’ Graham, 34

Silver spring, maryland.

In 2015, Graham said she kept a bag of women’s clothes in her car so that when she finished her shift at work as a tech support professional, she could drive to a Starbucks and change in the bathroom. She was also driving for Uber at the time, and one day she decided to dress as herself so she could practice coming out to her passengers before she came out to her family.

She came out fully in the summer of 2015, and said her gender dysphoria, or the distress caused by a misalignment between one’s sex assigned at birth and gender identity, went away with time.

“Once I began my transition journey and began living full time, my focus and productivity improved,” she said. “Many friends and people I know who knew me prior to transitioning said that they could tell I was happier now that I came out and was living my authentic life.”

Now, Graham is a service coordinator who helps autistic children who receive Medicaid-funded services, and she leads a support group for transgender people in her area.

Jordan Reid, 27

Harper woods, michigan.

Reid said her coming out as a transgender woman in 2022 happened alongside a number of other life changes. She had just gotten divorced, and then she dropped out of medical school, or, as she says, “exploded” all of her career aspirations.

But the last two years have been much happier, she said. Reid is back in school studying computer science and data science, and has rekindled her love for music. She has played guitar since she was 10, but said she stopped because she didn’t like her singing voice. Now, she sings in the shower every day.

“On paper, it may look like I have taken quite a few steps back in life,” Reid said. “In reality, what’s on paper doesn’t matter one bit if, instead of sacrificing my joy, I get to spend the majority of my time not only smiling, but truly feeling a reason to smile.”

Tiffany Jones, 35

Newark, new jersey.

Jones, who works in an Amazon warehouse, said transitioning has helped reduce her suicidal ideation.

“I am happy that I am living as my unapologetically authentic self,” Jones said, adding that her transition “helped me improve my self-confidence” and allowed her to be more creative. She now writes poetry, cosplays as anime characters and has a stronger support network, she said.

She said she worries about her personal safety as a Black trans woman, but “I just think about the positive things in life, and that there’s so much out there in the world, so much inspiration.”

Kylie Blackmon, 26

Azle, texas.

Blackmon said her life changed dramatically when she came out in 2021.

“It seemed like everything clicked mentally with me. No longer was I burdened with living a lie and having that weigh on me constantly,” she said. However, she said things are harder socially in her small Texas town of about 15,000 people, northwest of Fort Worth. She said she faces transphobia from her co-workers, and that some of her family members don’t understand her identity.

She’s currently training to be a phlebotomy technician, which is someone who collects and tests blood samples, and in her free time she enjoys doing makeup, shopping and spending time with her friends.

Cristina Angelica Piña, 23

Central valley, california.

Piña, a consultant, said that being trans can be difficult, but that “underneath this pain, there is an unfettered joy, power and beauty.”

“My existence reminds people of choice,” said Piña, who enjoys fashion, poetry, rap, cooking and spending time with her friends and her dog, Bella. “We have the autonomy to decide how we exist in the world. We have the freedom to present ourselves in a way we see fit — not what others have placed upon us.”

For more from NBC Out, sign up for our weekly newsletter .

Jo Yurcaba is a reporter for NBC Out.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

‘This is me, as I am’: A photographer documents her own gender transition

In 2015, Allison Lippy realized who she had always been—and turned her camera on herself to understand her journey as a transgender woman.

It took 27 years for me to realize I was transgender. It took a month or two to decide to physically transition. It took even less time than that to understand that I should document my transformation—for myself and for anyone else who needs to see it.

I should start at the beginning.

Growing up in Baltimore in the 1990s and early 2000s, I wasn’t aware that people could be anything other than the gender they were assigned at birth. There weren't resources or role models available to me at that point to even begin to understand who I was.

However, there were little hints of my queerness, a feeling of being different, something intangible. I never shared nor had the opportunity to explore those feelings until my early 20s. When I was 21, I came across videos of trans women on YouTube talking about their transitions. I would return to the videos periodically to see their updates, which intrigued me. I was telling myself that this was just research for a story that I wanted to do on trans identity. I wasn’t yet ready to confront the truth about myself.

I moved to New York City in 2011. Keeping my mind and body occupied by working in the photo industry distracted me from introspection. In 2015, I was sitting in my therapist’s office when she casually mentioned a person—a celebrity—who had come out as trans. I don’t remember what the context of that conversation was. I don’t think I was even paying particular attention to what she was saying. But I remember thinking, ‘Oh, that’s interesting.’

That throwaway comment was the spark that forced me to stop ignoring what had been burning in my subconscious. When I was at home, alone with my thoughts, I pondered my identity. Asking myself over and over again, ‘Am I trans? Am I a woman?’ I told myself probably not. Then I thought, ‘Maybe?’ I went back and forth, but as the days and then weeks progressed, the answer became clear: ‘Yup, that’s you.’

Finally, I realized I needed to accept who I was.

All the confusion I’d felt made sense; all the puzzle pieces fit for the first time. Everything just fell right into place. Confident and excited, I started moving quickly to make up for lost time.

I came out to my therapist first, just to test the waters, and then to my mother, who gladly was my rock throughout my transition. I’m fortunate that everybody in my life—including my parents, brother and friends—was really accepting.

Fundamentally, I owe my very existence to my trans elders, especially queer Indigenous, Black, Asian, Latinx, and POC people. They were in the streets and in our communities doing the hard work,paving the way for the rest of us to discover and live authentically as ourselves. Trailblazers, like Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and countless others , stood up and fought for our community in a time when visibility and representation were next to none.

Within a few months of coming out, I started taking hormones—and I began making self-portraits. Turning the camera on myself was a way to understand where I started and where I would end up. As a photographer and someone who didn’t encounter positive images of trans people as a kid, I felt I had a responsibility to tell my story through my own queer perspective.

I don’t intend to be representative of all trans people. Just as there isn’t one way to be human—there isn’t one right way or one wrong way to transition. We each have our own path.

My path happened to be a medical transition. In 2016, I went through facial feminization and gender reassignment surgeries. The facial feminization surgery reconstructed my skull, shaving bone to remove the effects of testosterone. While this might seem extreme, imagine discovering who you truly are and then looking in the mirror and seeing someone else. The surgeries were painful, but the journey to be yourself always includes some pain, sometimes mentally and physically.

It’s difficult to look back at old family photos now. I wish I could have been me earlier. But when I look at photos from early in this project, I see a person who is on a journey to being their true self. And toward the end of the series, there’s a few images where I think: ‘This is me, as I am. I have zero regrets.’

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- SEXUAL ORIENTATION

You May Also Like

A 'women-only' village? The truth is much more complex—and fascinating

See Sally Ride’s boundary-breaking life in photos

What was the Stonewall uprising?

Barbie’s signature pink may be Earth’s oldest color. Here’s how it took over the world.

From police raids to pop culture: The early history of modern drag

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Gory Details

- 2023 in Review

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

What my gender transition taught me about womanhood

- social change

- Transgender

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A 21-year-old trans woman's journey reflects shrinking social tolerance in Lebanon

A trans woman's harrowing journey to Australia from Iraqi Kurdistan through Lebanon and her struggle for a happier life.

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Lebanon is considered one of the most socially tolerant Arab nations and has long been a haven for LGBTQ people from elsewhere in the region. But its deep into an economic and political crisis now, and that makes it more difficult place to find refuge. NPR's Jane Arraf spoke to one transgender woman in Beirut about her harrowing journey there and onward.

(SOUNDBITE OF ZIPPING ZIPPER)

JANE ARRAF, BYLINE: Christine is packing for a new life in Australia. She isn't taking much. A few folded clothes in a battered suitcase.

CHRISTINE: And we're ready to go.

ARRAF: She's 21, a Kurdish Iraqi, and she says this reminds her of when she fled home. She hopes eventually she'll be able to come to grips with the last two years.

CHRISTINE: A 19-year-old being under so much pressure that decides to run away from their homeland and hide it from her family to a whole new, different country.

ARRAF: Christine says Lebanon opened its doors when she needed it most. She'd never been here before. A Kurdish speaker, she didn't even know Arabic.

CHRISTINE: When I asked myself, why am I here, I always get, like, super sad because it's all because I'm trans. I'm an individual born in the wrong body.

ARRAF: Christine is not using her birth name to avoid repercussions for her family in Iraq, where the LGBTQ community faces attacks from militias and even their own relatives. She has a slight build, delicate features and short, black, tousled hair. Her near-perfect English? She learned it from watching movies. She makes coffee over a hot plate in a kitchen with peeling white paint. Christine says when she was born, her father was thrilled at the thought his firstborn child was a boy. But then...

CHRISTINE: As a kid, I was always attracted to my mom's makeup, and I was attracted to, like, dolls and Barbie dolls and stuff.

ARRAF: She says because of that, her father, and sometimes her mother, would beat her. At school, she had no friends.

CHRISTINE: I couldn't, like, find anyone to talk to and feel safe and open up and tell them that I don't feel like a boy; I feel like a girl.

ARRAF: In college, Christine passed as a man. But after her mother suspected she had worn a dress to a private pride party...

CHRISTINE: She was like, because if that was the case, I would have either poisoned you myself, or I would have let your uncles take care of you, meaning that - my uncles killing me.

ARRAF: So she ran away to Lebanon, one of the few countries where Iraqis can go without a visa. But even here, the space is narrowing.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

HASSAN NASRALLAH: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah, recently told followers that under Islamic law, gay people are killed.

DOUMIT AZZI: Lately we are facing a huge anti-queer, anti-gender campaign in Lebanon triggered by lots of religious figures.

ARRAF: Doumit Azzi is with Helem, an LGBTQ advocacy group in Lebanon.

AZZI: And this has very, very, very dangerous consequences on the queer individuals here.

ARRAF: He says trans individuals are the most vulnerable. In Beirut, Christine couldn't get a job. She became a sex worker so she wouldn't end up in the street. She says she wants to talk about it because it happens to a lot of trans people.

CHRISTINE: Always so scared. (Crying) It was just so painful and so traumatizing, so scary. And you're so disgusted, and you just want it to end so bad.

ARRAF: But after two years in Beirut, another door has opened - to Australia, where she's been given entry because of persecution due to her gender identity. In Australia, she wants to go back to college and save money for gender-affirming surgery. Two days after we meet, Christine leaves me a voice message from an airport stopover.

CHRISTINE: It's a weird experience to, like, finally just see everyone and, you know, just feel like any other human being. Oh, my God, is this what I have missed for, like, 21 years?

ARRAF: Unlike so many, she's on her way to a new life, so far in so many ways from her old one, a life where she will finally feel safe to be who she is.

Jane Arraf, NPR News, Beirut.

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Music Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

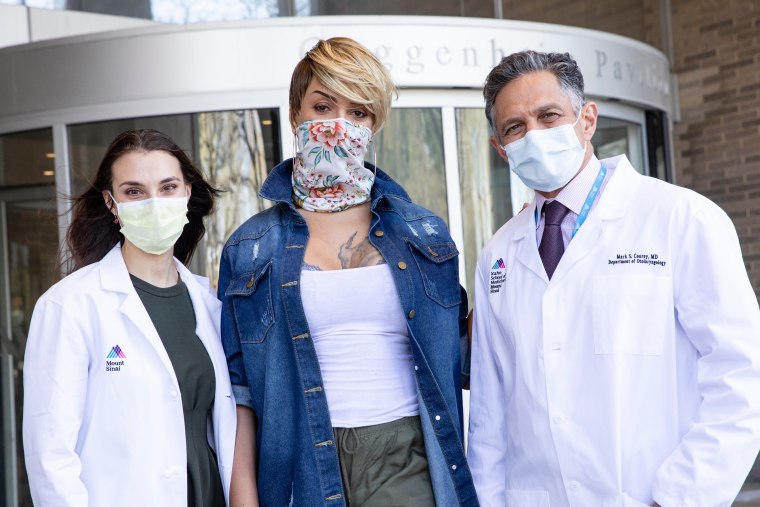

Trans woman details journey of gender confirmation surgery

JaiLynn Joanna Desvignes, 44, of the Bronx, is a makeup artist and a trans woman who has been sharing her experiences with gender confirmation surgery though her YouTube channel and blog. She spoke with TODAY about her experience.

This story discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is at risk of suicide please call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or go to SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

Even as a child, I knew who I was. I dreamed of walking down the aisle in a beautiful wedding dress. But how I looked on the outside clashed with who I was. So, I swallowed my feelings. As I entered my 20s, I was tired of feeling confused and started my social transition in my 30s. I used makeup and hair to affirm who I was. I took some hormones but not the full hormone replacement therapy regimen. While this helped me look more like myself, it soon became clear that this wasn’t enough.

The struggle between who I was and how I looked wore on me. Though many didn't realize how hard it was for me. I appeared happy and full of life, but inside I felt depressed. After years of feeling conflicted, I attempted suicide in 2016. I survived and realized that I had to be me. Denying who I was had been harming me and I wanted to live. I also wanted to help others. So, I began documenting my experiences on social media and hoped that my videos and blogs would prevent others from suffering like I did. I truly hoped that my words would help someone feel less alone.

Every transgender person lives a different experience and faces a different journey. Not everyone will follow a path similar to mine. Some might feel comfortable with just a social transition. Others might love the results from hormone replacement therapy. Still, others might not feel safe enough to transition in any way.

It feels important to share what was possible and what worked for me. I found the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and worked with the doctors there to find surgeries and treatments that helped me.

Dr. Bella Avanessian, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon at Mount Sinai’s Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, performed my facial feminization surgery, a procedure that softens the effects of testosterone on the face. I say it’s like she sanded my face down, though it’s much more advanced than that.

Even though the healing process was long, I loved the results. Dr. Avanessian also performed my breast enhancement surgery. Along with hormone replacement therapy — which blocks testosterone and provides the feminizing hormone estrogen — my shape transformed. I finally started to look more like the person I always knew I was. Dr. Avanessian did my vaginoplasty and Dr. Mark Courey, a professor of otolaryngology at Icahn School of Medicine, performed vocal feminization surgery to help my voice sound more like I wanted.

While the surgeries made me look the way I wanted, recovery was harder than I ever imagined. The pain that came with the procedures was shocking but manageable. With a vaginoplasty, I needed to dilate my vagina regularly, which is intimate. Recovering from such a procedure feels lonely. I was lucky to have support from a friend for the first month following surgery, but after she left it became tougher to be so isolated. Though, I think of my recovery period as my time in my cocoon and I’m spending time reflecting and growing.

It also felt hard to face other people’s opinions about what I was doing. For so long I had been living my life for other people. I waited to transition because I worried about the impact it would have on others in my life and I wanted them to have the space for their feelings and emotions. While some people took time grappling with their feelings and we became closer, others turned away from me. It has been tough but I felt that I needed to be me. In some ways, this process has allowed me to become closer to many of my loved ones and I feel that now I am aligned mind, body and soul, I can have deep relationships with them.

I feel happy with who I am and how I look now. I don't believe I will undergo any more procedures. I am lucky to have insurance that covered my gender-affirming care. According to a policy brief by the American Medical Association and GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality, trans people struggle to access adequate care and are less likely to have insurance than the general population and other people in the LGBTQ community. And, many trans individuals report that their insurance has denied some gender affirmation coverage.

While I wanted to share my journey to help other trans people to feel less alone, I also hope to show others what trans people are like. We come from various walks of life. We’re your best friend, niece, nephew, brother, mother, sister, aunt or uncle. While we may all be different we all want what so many people desire — love, acceptance and validation.

Meghan Holohan is a digital health reporter for TODAY.com and covers patient-centered stories, women’s health, disability and rare diseases.

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

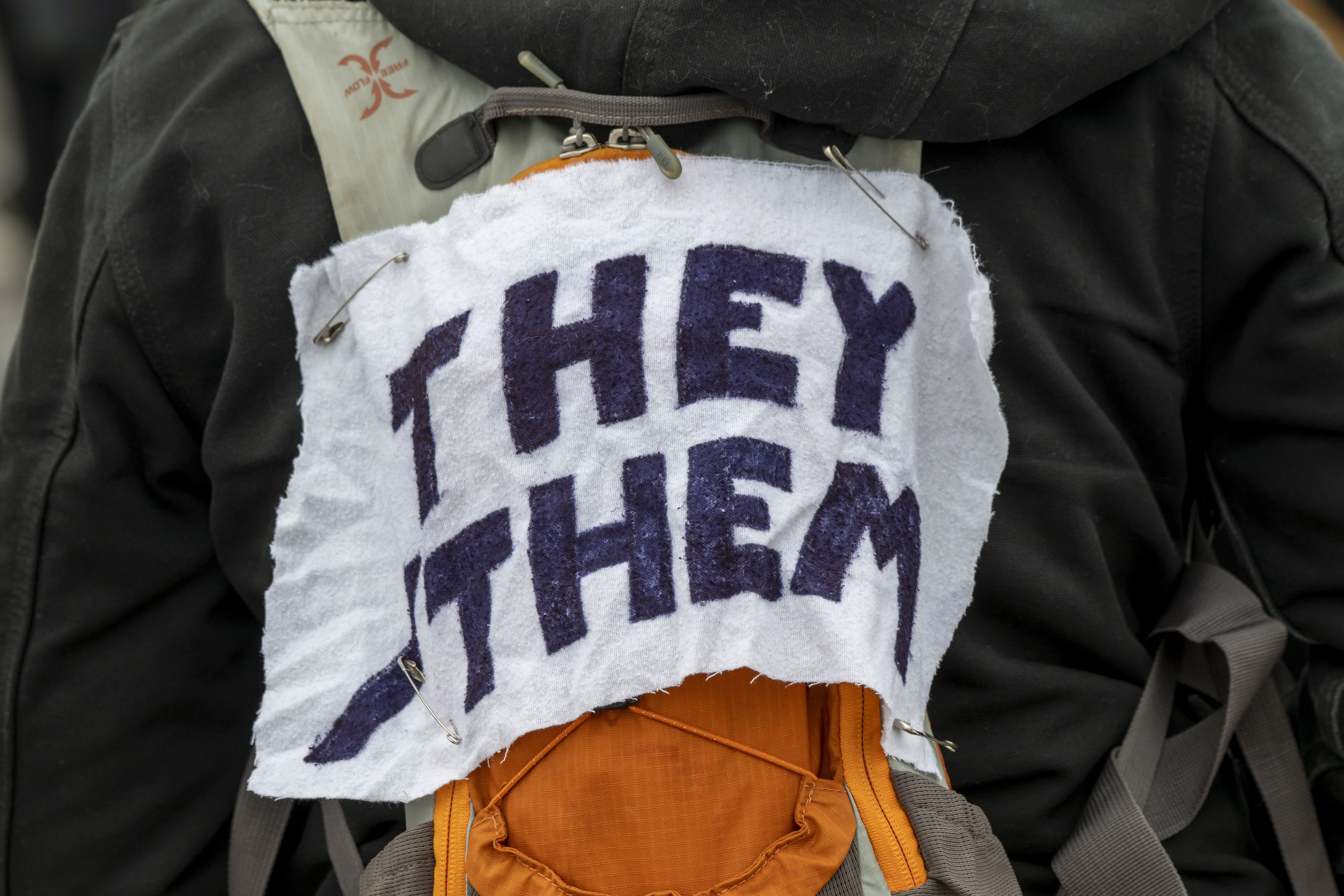

The Experiences, Challenges and Hopes of Transgender and Nonbinary U.S. Adults

Findings from pew research center focus groups, table of contents, introduction.

Transgender and nonbinary people have gained visibility in the U.S. in recent years as celebrities from Laverne Cox to Caitlyn Jenner to Elliot Page have spoken openly about their gender transitions. On March 30, 2022, the White House issued a proclamation recognizing Transgender Day of Visibility , the first time a U.S. president has done so.

More recently, singer and actor Janelle Monáe came out as nonbinary , while the U.S. State Department and Social Security Administration announced that Americans will be allowed to select “X” rather than “male” or “female” for their sex marker on their passport and Social Security applications.

At the same time, several states have enacted or are considering legislation that would limit the rights of transgender and nonbinary people . These include bills requiring people to use public bathrooms that correspond with the sex they were assigned at birth, prohibiting trans athletes from competing on teams that match their gender identity, and restricting the availability of health care to trans youth seeking to medically transition.

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that 1.6% of U.S. adults are transgender or nonbinary – that is, their gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. This includes people who describe themselves as a man, a woman or nonbinary, or who use terms such as gender fluid or agender to describe their gender. While relatively few U.S. adults are transgender, a growing share say they know someone who is (44% today vs. 37% in 2017 ). One-in-five say they know someone who doesn’t identify as a man or woman.

In order to better understand the experiences of transgender and nonbinary adults at a time when gender identity is at the center of many national debates, Pew Research Center conducted a series of focus groups with trans men, trans women and nonbinary adults on issues ranging from their gender journey, to how they navigate issues of gender in their day-to-day life, to what they see as the most pressing policy issues facing people who are trans or nonbinary. This is part of a larger study that includes a survey of the general public on their attitudes about gender identity and issues related to people who are transgender or nonbinary.

The terms transgender and trans are used interchangeably throughout this essay to refer to people whose gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. This includes, but is not limited to, transgender men (that is, men who were assigned female at birth) and transgender women (women who were assigned male at birth).

Nonbinary adults are defined here as those who are neither a man nor a woman or who aren’t strictly one or the other. While some nonbinary focus group participants sometimes use different terms to describe themselves, such as “gender queer,” “gender fluid” or “genderless,” all said the term “nonbinary” describes their gender in the screening questionnaire. Some, but not all, nonbinary participants also consider themselves to be transgender.

References to gender transitions relate to the process through which trans and nonbinary people express their gender as different from social expectations associated with the sex they were assigned at birth. This may include social, legal and medical transitions. The social aspect of a gender transition may include going by a new name or using different pronouns, or expressing their gender through their dress, mannerisms, gender roles or other ways. The legal aspect may include legally changing their name or changing their sex or gender designation on legal documents or identification. Medical care may include treatments such as hormone therapy, laser hair removal and/or surgery.

References to femme indicate feminine gender expression. This is often in contrast to “masc,” meaning masculine gender expression.

Cisgender is used to describe people whose gender matches the sex they were assigned at birth and who do not identify as transgender or nonbinary.

Misgendering is defined as referring to or addressing a person in ways that do not align with their gender identity, including using incorrect pronouns, titles (such as “sir” or “ma’am”), and other terms (such as “son” or “daughter”) that do not match their gender.

References to dysphoria may include feelings of distress due to the mismatch of one’s gender and sex assigned at birth, as well as a diagnosis of gender dysphoria , which is sometimes a prerequisite for access to health care and medical transitions.

The acronym LGBTQ+ refers to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or, in some cases, questioning), and other sexual orientations or gender identities that are not straight or cisgender, such as intersex, asexual or pansexual.

Pew Research Center conducted this research to better understand the experiences and views of transgender and nonbinary U.S. adults. Because transgender and nonbinary people make up only about 1.6% of the adult U.S. population, this is a difficult population to reach with a probability-based, nationally representative survey. As an alternative, we conducted a series of focus groups with trans and nonbinary adults covering a variety of topics related to the trans and nonbinary experience. This allows us to go more in-depth on some of these topics than a survey would typically allow, and to share these experiences in the participants’ own words.

For this project, we conducted six online focus groups, with a total of 27 participants (four to five participants in each group), from March 8-10, 2022. Participants were recruited by targeted email outreach among a panel of adults who had previously said on a survey that they were transgender or nonbinary, as well as via connections through professional networks and LGBTQ+ organizations, followed by a screening call. Candidates were eligible if they met the technology requirements to participate in an online focus group and if they either said they consider themselves to be transgender or if they said their gender was nonbinary or another identity other than man or woman (regardless of whether or not they also said they were transgender). For more details, see the Methodology .

Participants who qualified were placed in groups as follows: one group of nonbinary adults only (with a nonbinary moderator); one group of trans women only (with a trans woman moderator); one group of trans men only (with a trans man moderator); and three groups with a mix of trans and nonbinary adults (with either a nonbinary moderator or a trans man moderator). All of the moderators had extensive experience facilitating groups, including with transgender and nonbinary participants.

The participants were a mix of ages, races/ethnicities, and were from all corners of the country. For a detailed breakdown of the participants’ demographic characteristics, see the Methodology .

The findings are not statistically representative and cannot be extrapolated to wider populations.

Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity or to remove identifying details. In this essay, participants are identified as trans men, trans women, or nonbinary adults based on their answers to the screening questionnaire. These words don’t necessarily encompass all of the ways in which participants described their gender. Participants’ ages are grouped into the following categories: late teens; early/mid/late 20s, 30s and 40s; and 50s and 60s (those ages 50 to 69 were grouped into bigger “buckets” to better preserve their anonymity).

These focus groups were not designed to be representative of the entire population of trans and nonbinary U.S. adults, but the participants’ stories provide a glimpse into some of the experiences of people who are transgender and/or nonbinary. The groups included a total of 27 transgender and nonbinary adults from around the U.S. and ranging in age from late teens to mid-60s. Most currently live in an urban area, but about half said they grew up in a suburb. The groups included a mix of White, Black, Hispanic, Asian and multiracial American participants. See Methodology for more details.

Identity and the gender journey

Most focus group participants said they knew from an early age – many as young as preschool or elementary school – that there was something different about them, even if they didn’t have the words to describe what it was. Some described feeling like they didn’t fit in with other children of their sex but didn’t know exactly why. Others said they felt like they were in the wrong body.

“I remember preschool, [where] the boys were playing on one side and the girls were playing on the other, and I just had a moment where I realized what side I was supposed to be on and what side people thought I was supposed to be on. … Yeah, I always knew that I was male, since my earliest memories.” – Trans man, late 30s

“As a small child, like around kindergarten [or] first grade … I just was [fascinated] by how some people were small girls, and some people were small boys, and it was on my mind constantly. And I started to feel very uncomfortable, just existing as a young girl.” – Trans man, early 30s

“I was 9 and I was at day camp and I was changing with all the other 9-year-old girls … and I remember looking at everybody’s body around me and at my own body, and even though I was visually seeing the exact shapeless nine-year-old form, I literally thought to myself, ‘oh, maybe I was supposed to be a boy,’ even though I know I wasn’t seeing anything different. … And I remember being so unbothered by the thought, like not a panic, not like, ‘oh man, I’m so different, like everybody here I’m so different and this is terrible,’ I was like, ‘oh, maybe I was supposed to be a boy,’ and for some reason that exact quote really stuck in my memory.” – Nonbinary person, late 30s

“Since I was little, I felt as though I was a man who, when they were passing out bodies, someone made a goof and I got a female body instead of the male body that I should have had. But I was forced by society, especially at that time growing up, to just make my peace with having a female body.” – Nonbinary person, 50s

“I’ve known ever since I was little. I’m not really sure the age, but I just always knew when I put on boy clothes, I just felt so uncomfortable.” – Trans woman, late 30s

“It was probably as early as I can remember that I wasn’t like my brother or my father [and] not exactly like my girl cousins but I was something else, but I didn’t know what it was.” – Nonbinary person, 60s

Many participants were well into adulthood before they found the words to describe their gender. For those focus group participants, the path to self-discovery varied. Some described meeting someone who was transgender and relating to their experience; others described learning about people who are trans or nonbinary in college classes or by doing their own research.

“I read a Time magazine article … called ‘Homosexuality in America’ … in 1969. … Of course, we didn’t have language like we do now or people were not willing to use it … [but] it was kind of the first word that I had ever heard that resonated with me at all. So, I went to school and I took the magazine, we were doing show-and-tell, and I stood up in front of the class and said, ‘I am a homosexual.’ So that began my journey to figure this stuff out.” – Nonbinary person, 60s

“It wasn’t until maybe I was 20 or so when my friend started his transition where I was like, ‘Wow, that sounds very similar to the emotions and challenges I am going through with my own identity.’ … My whole life from a very young age I was confused, but I didn’t really put a name on it until I was about 20.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“I knew about drag queens, but I didn’t know what trans was until I got to college and was exposed to new things, and that was when I had a word for myself for the first time.” – Trans man, early 40s

“I thought that by figuring out that I was interested in women, identifying as lesbian, I thought [my anxiety and sadness] would dissipate in time, and that was me cracking the code. But then, when I got older, I left home for the first time. I started to meet other trans people in the world. That’s when I started to become equipped with the vocabulary. The understanding that this is a concept, and this makes sense. And that’s when I started to understand that I wasn’t cisgender.” – Trans man, early 30s

“When I took a human sexuality class in undergrad and I started learning about gender and different sexualities and things like that, I was like, ‘oh my god. I feel seen.’ So, that’s where I learned about it for the first time and started understanding how I identify.” – Nonbinary person, mid-20s

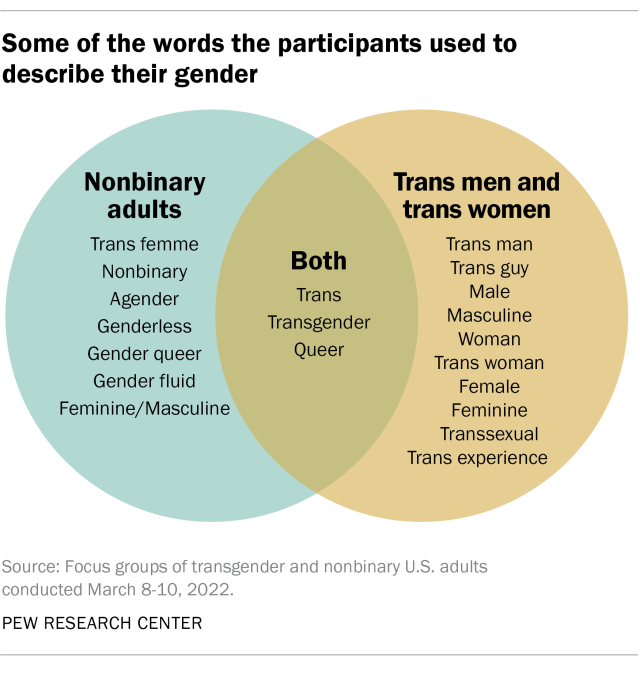

Focus group participants used a wide range of words to describe how they see their gender. For many nonbinary participants, the term “nonbinary” is more of an umbrella term, but when it comes to how they describe themselves, they tend to use words like “gender queer” or “gender fluid.” The word “queer” came up many times across different groups, often to describe anyone who is not straight or cisgender. Some trans men and women preferred just the terms “man” or “woman,” while some identified strongly with the term “transgender.” The graphic below shows just some of the words the participants used to describe their gender.

The way nonbinary people conceptualize their gender varies. Some said they feel like they’re both a man and a woman – and how much they feel like they are one or the other may change depending on the day or the circumstance. Others said they don’t feel like they are either a man or a woman, or that they don’t have a gender at all. Some, but not all, also identified with the term transgender.

“I had days where I would go out and just play with the boys and be one of the boys, and then there would be times that I would play with the girls and be one of the girls. And then I just never really knew what I was. I just knew that I would go back and forth.” – Nonbinary person, mid-20s

“Growing up with more of a masculine side or a feminine side, I just never was a fan of the labelling in terms of, ‘oh, this is a bit too masculine, you don’t wear jewelry, you don’t wear makeup, oh you’re not feminine enough.’ … I used to alternate just based on who I felt I was. So, on a certain day if I felt like wearing a dress, or a skirt versus on a different day, I felt like wearing what was considered men’s pants. … So, for me it’s always been both.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I feel like my gender is so amorphous and hard to hold and describe even. It’s been important to find words for it, to find the outlines of it, to see the shape of it, but it’s not something that I think about as who I am, because I’m more than just that.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“What words would I use to describe me? Genderless, if gender wasn’t a thing. … I guess if pronouns didn’t exist and you just called me [by my name]. That’s what my gender is. … And I do use nonbinary also, just because it feels easier, I guess.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

Some participants said their gender is one of the most important parts of their identity, while others described it as one of many important parts or a small piece of how they see themselves. For some, the focus on gender can get tiring. Those who said gender isn’t a central – or at least not the most central – part of their identity mentioned race, ethnicity, religion and socioeconomic class as important aspects that shape their identity and experiences.

“It is tough because [gender] does affect every factor of your life. If you are doing medical transitioning then you have appointments, you have to pay for the appointments, you have to be working in a job that supports you to pay for those appointments. So, it is definitely integral, and it has a lot of branches. And it deals with how you act, how you relate to friends, you know, I am sure some of us can relate to having to come out multiple times in our lives. That is why sexuality and gender are very integral and I would definitely say I am proud of it. And I think being able to say that I am proud of it, and my gender, I guess is a very important part of my identity.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“Sometimes I get tired of thinking about my gender because I am actively [undergoing my medical transition]. So, it is a lot of things on my mind right now, constantly, and it sometimes gets very tiring. I just want to not have to think about it some days. So, I would say it’s, it’s probably in my top three [most important parts of my identity] – parent, Black, queer nonbinary.” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“I live in a town with a large queer and trans population and I don’t have to think about my gender most of the time other than having to come out as trans. But I’m poor and that colors everything. It’s not a chosen part of my identity but that part of my identity is a lot more influential than my gender.” – Trans man, early 40s

“My gender is very important to my identity because I feel that they go hand in hand. Now my identity is also broken down into other factors [like] character, personality and other stuff that make up the recipe for my identity. But my gender plays a big part of it. … It is important because it’s how I live my life every day. When I wake up in the morning, I do things as a woman.” – Trans woman, mid-40s

“I feel more strongly connected to my other identities outside of my gender, and I feel like parts of it’s just a more universal thing, like there’s a lot more people in my socioeconomic class and we have much more shared experiences.” – Trans man, late 30s

Some participants spoke about how their gender interacted with other aspects of their identity, such as their race, culture and religion. For some, being transgender or nonbinary can be at odds with other parts of their identity or background.

“Culturally I’m Dominican and Puerto Rican, a little bit of the macho machismo culture, in my family, and even now, if I’m going to be a man, I’ve got to be a certain type of man. So, I cannot just be who I’m meant to be or who I want myself to be, the human being that I am.” – Trans man, mid-30s

“[Judaism] is a very binary religion. There is a lot of things like for men to do and a lot of things for women to do. … So, it is hard for me now as a gender queer person, right, to connect on some levels with [my] religion … I have just now been exposed to a bunch of trans Jewish spaces online which is amazing.” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“Just being Indian American, I identify and love aspects of my culture and ethnicity, and I find them amazing and I identify with that, but it’s kind of separated. So, I identify with the culture, then I identify here in terms of gender and being who I am, but I kind of feel the necessity to separate the two, unfortunately.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I think it’s really me being a Black woman or a Black man that can sometimes be difficult. And also, my ethnic background too. It’s really rough for me with my family back home and things of that nature.” – Nonbinary person, mid-20s

Navigating gender day-to-day

For some, deciding how open to be about their gender identity can be a constant calculation. Some participants reported that they choose whether or not to disclose that they are trans or nonbinary in a given situation based on how safe or comfortable they feel and whether it’s necessary for other people to know. This also varies depending on whether the participant can easily pass as a cisgender man or woman (that is, they can blend in so that others assume them to be cisgender and don’t recognize that they are trans or nonbinary).

“It just depends on whether I feel like I have the energy to bring it up, or if it feels worth it to me like with doctors and stuff like that. I always bring it up with my therapists, my primary [care doctor], I feel like she would get it. I guess it does vary on the situation and my capacity level.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“I decide based on the person and based on the context, like if I feel comfortable enough to share that piece of myself with them, because I do have the privilege of being able to move through the world and be identified as cis[gender] if I want to. But then it is important to me – if you’re important to me, then you will know who I am and how I identify. Otherwise, if I don’t feel comfortable or safe then I might not.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“The expression of my gender doesn’t vary. Who I let in to know that I was formerly female – or formerly perceived as female – is kind of on a need to know basis.” – Trans man, 60s

“It’s important to me that people not see me as cis[gender], so I have to come out a lot when I’m around new people, and sometimes that’s challenging. … It’s not information that comes out in a normal conversation. You have to force it and that’s difficult sometimes.” – Trans man, early 40s

Work is one realm where many participants said they choose not to share that they are trans or nonbinary. In some cases, this is because they want to be recognized for their work rather than the fact that they are trans or nonbinary; in others, especially for nonbinary participants, they fear it will be perceived as unprofessional.

“It’s gotten a lot better recently, but I feel like when you’re nonbinary and you use they/them pronouns, it’s just seen as really unprofessional and has been for a lot of my life.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“Whether it’s LinkedIn or profiles [that] have been updated, I’ve noticed people’s resumes have their pronouns now. I don’t go that far because I just feel like it’s a professional environment, it’s nobody’s business.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I don’t necessarily volunteer the information just to make it public; I want to be recognized for my character, my skill set, in my work in other ways.” – Trans man, early 30s

Some focus group participants said they don’t mind answering questions about what it’s like to be trans or nonbinary but were wary of being seen as the token trans or nonbinary person in their workplace or among acquaintances. Whether or not they are comfortable answering these types of questions sometimes depends on who’s asking, why they want to know, and how personal the questions get.

“I’ve talked to [my cousin about being trans] a lot because she has a daughter, and her daughter wants to transition. So, she always will come to me asking questions.” – Trans woman, early 40s

“It is tough being considered the only resource for these topics, right? In my job, I would hate to call myself the token nonbinary, but I was the first nonbinary person that they hired and they were like, ‘Oh, my gosh, let me ask you all the questions as you are obviously the authority on the subject.’ And it is like, ‘No, that is a part of me, but there are so many other great resources.’” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“I don’t want to be the token. I’m not going to be no spokesperson. If you have questions, I’m the first person you can ask. Absolutely. I don’t mind discussing. Ask me some of the hardest questions, because if you ask somebody else you might get you know your clock cleaned. So, ask me now … so you can be educated properly. Otherwise, I don’t believe it’s anybody’s business.” – Trans woman, early 40s

Most nonbinary participants said they use “they/them” as their pronouns, but some prefer alternatives. These alternatives include a combination of gendered and gender-neutral pronouns (like she/they) or simply preferring that others use one’s names rather than pronouns.

“If I could, I would just say my name is my pronoun, which I do in some spaces, but it just is not like a larger view. It feels like I’d rather have less labor on me in that regard, so I just say they/them.” – Nonbinary person, late 20s

“For me personally, I don’t get mad if someone calls me ‘he’ because I see what they’re looking at. They look and they see a guy. So, I don’t get upset. I know a few people who do … and they correct you. Me, I’m a little more fluid. So, that’s how it works for me.” – Nonbinary person, mid-30s

“I use they/she pronouns and I put ‘they’ first because that is what I think is most comfortable and it’s what I want to draw people’s attention to, because I’m 5 feet tall and 100 pounds so it’s not like I scream masculine at first sight, so I like putting ‘they’ first because otherwise people always default to ‘she.’ But I have ‘she’ in there, and I don’t know if I’d have ‘she’ in there if I had not had kids.” – Nonbinary person, late 30s

“Why is it so hard for people to think of me as nonbinary? I choose not to use only they/them pronouns because I do sometimes identify with ‘she.’ But I’m like, ‘Do I need to use they/them pronouns to be respected as nonbinary?’ Sometimes I feel like I should do that. But I don’t want to feel like I should do anything. I just want to be myself and have that be accepted and respected.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I have a lot of patience for people, but [once someone in public used] they/them pronouns and I thanked them and they were like, ‘Yeah, I just figure I’d do it when I don’t know [someone’s] pronouns.’ And I’m like, ‘I love it, thank you.’” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

Transgender and nonbinary participants find affirmation of their gender identity and support in various places. Many cited their friends, chosen families (and, less commonly, their relatives), therapists or other health care providers, religion, or LGBTQ+ spaces as sources of support.

“I’m just not close with my family [of origin], but I have a huge chosen family that I love and that fully respects my identity.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“Before the pandemic I used to go out to bars a lot; there’s a queer bar in my town and it was a really nice place just being friends with everybody who went and everybody who worked there, it felt really nice you know, and just hearing everybody use the right pronouns for me it just felt really good.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I don’t necessarily go to a lot of dedicated support groups, but I found that there’s kind of a good amount of support in areas or groups or fandoms for things that have a large LGBT population within them. Like certain shows or video games, where it’s just kind of a joke that all the gay people flock to this.” – Trans woman, late teens

“Being able to practice my religion in a location with a congregation that is just completely chill about it, or so far has been completely chill about it, has been really amazing.” – Nonbinary person, late 30s

Many participants shared specific moments they said were small in the grand scheme of things but made them feel accepted and affirmed. Examples included going on dates, gestures of acceptance by a friend or social group, or simply participating in everyday activities.

“I went on a date with a really good-looking, handsome guy. And he didn’t know that I was trans. But I told him, and we kept talking and hanging out. … That’s not the first time that I felt affirmed or felt like somebody is treating me as I present myself. But … he made me feel wanted and beautiful.” – Trans woman, late 30s

“I play [on a men’s rec league] hockey [team]. … I joined the league like right when I first transitioned and I showed up and I was … nervous with locker rooms and stuff, and they just accepted me as male right away.” – Trans man, late 30s

“I ended up going into a barbershop. … The barber was very welcoming, and talked to me as if I was just a casual customer and there was something that clicked within that moment where, figuring out my gender identity, I just wanted to exist in the world to do these natural things like other boys and men would do. So, there was just something exciting about that. It wasn’t a super macho masculine moment, … he just made me feel like I blended in.” – Trans man, early 30s

Participants also talked about negative experiences, such as being misgendered, either intentionally or unintentionally. For example, some shared instances where they were treated or addressed as a gender other than the gender that they identify as, such as people referring to them as “he” when they go by “she,” or where they were deadnamed, meaning they were called by the name they had before they transitioned.

“I get misgendered on the phone a lot and that’s really annoying. And then, even after I correct them, they keep doing it, sometimes on purpose and sometimes I think they’re just reading a script or something.” – Trans man, late 30s

“The times that I have been out, presenting femme, there is this very subconscious misgendering that people do and it can be very frustrating. [Once, at a restaurant,] I was dressed in makeup and nails and shoes and everything and still everyone was like, ‘Sir, what would you like?’ … Those little things – those microaggressions – they can really eat away at people.” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“People not calling me by the right name. My family is a big problem, they just won’t call me by my name, you know? Except for my nephew, who is of the Millennial generation, so at least he gets it.” – Nonbinary person, 60s

“I’m constantly misgendered when I go out places. I accept this – because of the way I look, people are going to perceive me as a woman and it doesn’t cause me huge dysphoria or anything, it’s just nice that the company that I keep does use the right pronouns.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

Some participants also shared stories of discrimination, bias, humiliation, and even violence. These experiences ranged from employment discrimination to being outed (that is, someone else disclosing the fact that they are transgender or nonbinary without their permission) without their permission to physical attacks.

“I was on a date with this girl and I had to use the bathroom … and the janitor … wouldn’t let me use the men’s room, and he kept refusing to let me use the men’s room, so essentially, I ended up having to use the same bathroom as my date.” – Trans man, late 30s

“I’ve been denied employment due to my gender identity. I walked into a supermarket looking for jobs. … And they flat out didn’t let me apply. They didn’t even let me apply.” – Trans man, mid-30s

“[In high school,] this group of guys said, ‘[name] is gay.’ I ignored them but they literally threw me and tore my shirt from my back and pushed me to the ground and tried to strip me naked. And I had to fight for myself and use my bag to hit him in the face.” – Trans woman, late 20s

“I took a college course [after] I had my name changed legally and the instructor called me out in front of the class and called me a liar and outed me.” – Trans man, late 30s

Seeking medical care for gender transitions

Many, but not all, participants said they have received medical care , such as surgery or hormone therapy, as part of their gender transition. For those who haven’t undergone a medical transition, the reasons ranged from financial barriers to being nervous about medical procedures in general to simply not feeling that it was the right thing for them.

“For me to really to live my truth and live my identity, I had to have the surgery, which is why I went through it. It doesn’t mean [that others] have to, or that it will make you more or less of a woman because you have it. But for me to be comfortable, … that was a big part of it. And so, that’s why I felt I had to get it.” – Trans woman, early 40s

“I’m older and it’s an operation. … I’m just kind of scared, I guess. I’ve never had an operation. I mean, like any kind of operation. I’ve never been to the hospital or anything like that. So, it [is] just kind of scary. But I mean, I want to. I think about all the time. I guess have got to get the courage up to do it.” – Trans woman, early 40s

“I’ve decided that the dysphoria of a second puberty … would just be too much for me and I’m gender fluid enough where I’m happy, I guess.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I’m too old to change anything, I mean I am what I am. [laughs]” – Nonbinary person, 60s

Many focus group participants who have sought medical treatment for their gender transition faced barriers, although some had positive experiences. For those who said there were barriers, the cost and the struggle to find sympathetic doctors were often cited as challenges.

“I was flat out turned down by the primary care physician who had to give the go-ahead to give me a referral to an endocrinologist; I was just shut down. That was it, end of story.” – Nonbinary person, 50s

“I have not had surgery, because I can’t access surgery. So unless I get breast cancer and have a double mastectomy, surgery is just not going to happen … because my health insurance wouldn’t cover something like that. … It would be an out-of-pocket plastic surgery expense and I can’t afford that at this time.” – Nonbinary person, 50s

“Why do I need the permission of a therapist to say, ‘This person’s identity is valid,’ before I can get the health care that I need to be me, that is vital for myself and for my way of life?” – Nonbinary person, mid-40s

“[My doctor] is basically the first person that actually embraced me and made me accept [who I am].” – Trans woman, late 20s

Many people who transitioned in previous decades described how access has gotten much easier in recent years. Some described relying on underground networks to learn which doctors would help them obtain medical care or where to obtain hormones illegally.

“It was hard financially because I started so long ago, just didn’t have access like that. Sometimes you have to try to go to Mexico or learn about someone in Mexico that was a pharmacist, I can remember that. That was a big thing, going through the border to Mexico, that was wild. So, it was just hard financially because they would charge so much for testosterone. And there was the whole bodybuilding community. If you were transitioning, you went to bodybuilders, and they would charge you five times what they got it [for], so it was kind of tough.” – Trans man, early 40s

“It was a lot harder to get a surgeon when I started transitioning; insurance was out of the question, there wasn’t really a national discussion around trans people and their particular medical needs. So, it was challenging having to pay everything out of pocket at a young age.” – Trans man, early 30s

“I guess it was hard for me to access hormones initially just because you had to jump through so many hoops, get letters, and then you had to find a provider that was willing to write it. And now it’s like people are getting it from their primary care doctor, which is great, but a very different experience than I had.” – Trans man, early 40s

Connections with the broader LGBTQ+ community

The discussions also touched on whether the participants feel a connection with a broader lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community or with other people who are LGBTQ+. Views varied, with some saying they feel an immediate connection with other people who are LGBTQ+, even with those who aren’t trans or nonbinary, and others saying they don’t necessarily feel this way.

“It’s kind of a recurring joke where you can meet another LGBT person and it is like there is an immediate understanding, and you are basically talking and giving each other emotional support, like you have been friends for 10-plus years.” – Trans woman, late teens

“I don’t think it’s automatic friendship between queer people, there’s like a kinship, but I don’t think there’s automatic friendship or anything. I think it’s just normal, like, how normal people make friends, just based on common interests.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I do think of myself as part of the LGBT [community] … I use the resources that are put in place for these communities, whether that’s different health care programs, support groups, they have the community centers. … So, I do consider myself to be part of this community, and I’m able to hopefully take when needed, as well as give back.” – Trans man, mid-30s

“I feel like that’s such an important part of being a part of the [LGBTQ+] alphabet soup community, that process of constantly learning and listening to each other and … growing and developing language together … I love that aspect of creating who we are together, learning and unlearning together, and I feel like that’s a part of at least the queer community spaces that I want to be in. That’s something that’s core to me.” – Nonbinary person, early 30s

“I identify as queer. I feel like I’m a part of the LGBT community. That’s more of a part of my identity than being trans. … Before I came out as trans, I identified as a lesbian. That was also a big part of my identity. So, that may be too why I feel like I’m more part of the LGB community.” – Trans man, early 40s