Commentary:A Clone of My Own

Topics of discussion.

- The episode aired on John's mom's birthday. John says she likes to call herself "Futuramamomma".

- This is one of two episodes Patric wrote that rhyme with his last name, the other being " A Leela of Her Own ".

- The drawing of the Professor on the screen is in the style of a certain artist but they can't remember who.

- This is the first episode to show Zoidberg 's interest in stand-up comedy.

- The set where the Professor's 150th birthday party is hosted is based on The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast .

- Patric explains that "Musky" and "Pike" are both types of fish.

- John was approached by a fan who told him that he was really good at doing different voices when playing Dungeons & Dragons with his friends and that he wanted to be a voice actor.

- The time machine is based on the one from the 1960 film adaptation of the H. G. Wells story The Time Machine .

- When all the characters speak at the same time, it is known as an "omni" in directing terms. This episode is the first one to have a character end the omni with a "topper", e.g. they speak last and can be heard above all the other characters. In this case, it is Zoidberg saying "a successor to the professor?"

- Cubert was conceived before the show even began to enter production.

- Cubert was meant to point out scientific inconsistencies throughout the show, anticipating how fanatics of the show would probably do the same thing.

- It is later explained this is because the Professor was originally going to explain how the engines of the ship work to Cubert from inside his laboratory in the top of the Planet Express building's tower.

- David says it isn't a good tradition and that Matt may be thinking of Wesley Crusher from Star Trek: The Next Generation .

- The characters in the show wouldn't put up with Cubert any more than the audience would.

- Matt says there are a lot of things in science fiction that you have to side-step in order to make the show adventurous, fun and fast-moving, such as faster-than-light travel, aliens speaking English, levitation and time travel.

- Matt says Bart Simpson 's early designs looked like Pugsley, too.

- The third act is "jam-packed" with 3D animation.

- David says Matt likes assembly lines and "people having stuff done to them by machines".

- Patric says all the old people jokes are revenge for him having to live in Southwest Florida for 13 years.

- The huge room with the tombstone-looking towers was inspired by a cemetery near the offices where the show is made.

- Rich thinks Futurama is the only primetime animated show that has effects animatiors working on staff.

- John thinks there is a quota to include the words "bastard" and "ass" in the show.

- The "wandering bladder" joke was pitched at every stage of the episode's re-write. Patric says they had everything from "rectal gout" to "cancerous hangnails".

- Cubert was originally meant to appear in 1ACV08, " A Big Piece of Garbage ".

Highlights / Quotes

Patric Verrone : [Reading the title caption] Coming soon to an illegal DVD, now this is not an illegal DVD that you're watching this on, unless, of course, it is. John DiMaggio : [Laughs]

[The Professor is shown wearing a pale yellow "Dungeon Master" shirt] David X. Cohen : I never had a shirt like that...and it was also a different colour.

Matt Groening : Well, the original idea for this character was that he was gonna be the character who was standing on the sidelines of every episode, pointing out all the logical flaws, and that he would comment on--anticipating the criticisms of the fanatics who are following the show. And uh... Patric Verrone : But then the show had no flaws and so there was no... David X. Cohen : [Laughs] John DiMaggio : Awh yeah! Matt Groening : Exactly.

- Commentaries with Matt Groening

- Commentaries with David X. Cohen

- Commentaries with Rich Moore

- Commentaries with Patric M. Verrone

- Commentaries with Scott Vanzo

- Commentaries with John DiMaggio

- Commentaries

- DVD box sets

Navigation menu

- Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine

- BREAST IMAGING

- CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

- COMPUTERIZED TOMOGRAPHY

- EMERGENCY RADIOLOGY

- FETAL MEDICINE

- FRCR READING LIST

- GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING

- GENERAL RADIOLOGY

- GENITOURINARY IMAGING

- HEAD & NECK IMAGING

- INTERVENTIONAL RADIOLOGY

- MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

- MUSCULOSKELETAL IMAGING

- NEUROLOGICAL IMAGING

- NUCLEAR MEDICINE

- OBSTETRICS & GYNAECOLOGY IMAGING

- PEDIATRIC IMAGING

- RADIOGRAPHIC ANATOMY

- RESPIRATORY IMAGING

- ULTRASONOGRAPHY

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Member

- iOS/Android App

Anomalies and Anatomic Variants of the Gallbladder and Biliary Tract

Chapter Outline Embryology Agenesis of the Gallbladder Duplication of the Gallbladder Anomalies of Gallbladder Shape Phrygian Cap Multiseptate Gallbladder Diverticula Abnormalities of Gallbladder Position Wandering Gallbladder Gallbladder Torsion Ectopic Gallbladder Abnormalities in Gallbladder Size Cholecystomegaly Microgallbladder Biliary Tract Anomalies Choledochal Cysts Choledochoceles Caroli’s Disease There are many congenital abnormalities of the gallbladder and bile ducts, which, excluding biliary atresia and choledochal cysts, are usually of no clinical or functional significance. These anomalies are usually found in the course of evaluating biliary disease in an adult patient and are of interest primarily to the surgeon, who must deal with the anatomic variation during the course of surgery. Embryology When the human embryo is 2.5 mm in size, a bifid bud forms along the anterior margin of the primitive foregut and proliferates laterally into the septum transversum. The more cephalad of these two diverticula is responsible for the formation of the liver and intrahepatic bile ducts, whereas the caudal diverticulum develops into the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tree. At the 5-mm stage of development, the originally hollow primordium of the gallbladder and common bile duct becomes occluded with endodermal cells but is soon revacuolated. If recanalization is incomplete, a compartmentalized multiseptate gallbladder results. A single, transversely oriented septum results in the phrygian cap deformity, whereas longitudinal septa produce a bifid or triple gallbladder. The lumen of the common bile duct is reestablished at the 7.5-mm stage and the gallbladder and duodenal lumen somewhat later. Bile is secreted by the 12th week. At the 10- to 15-mm stage (6-7 weeks), the gallbladder has formed and is connected to the duodenum by a canalized choledochocystic duct. This duct originates from the lateral aspect of the primitive foregut and eventually terminates on the medial or posteromedial aspect of the descending portion of the duodenum after the foregut completes its 270-degree rotation. The formation of the intrahepatic ducts is preceded by the development of the portal and hepatic veins and the formation of the hepatocytes and Kupffer cells. The intrahepatic ducts by the 18-mm stage consist only of a blindly ending solid core of cells that extends from the junction of the cystic and common ducts toward the liver hilum. At the point of contact between this blindly ending ductal anlage and the hepatocytes, the intrahepatic ducts develop along the framework of the previously formed portal vein branches similar to vines on a trellis. Significant variation in the configuration of the intrahepatic ducts can be accounted for by the unpredictable manner in which they wind around preexisting portal veins. Agenesis of the Gallbladder Agenesis of the gallbladder is caused by failure of development of the caudal division of the primitive hepatic diverticulum or failure of vacuolization after the solid phase of embryonic development. Atresia or hypoplasia of the gallbladder also represents aborted development of the organ. Other congenital anomalies are present in two thirds of these patients, including congenital heart lesions, polysplenia, imperforate anus, absence of one or more bones, and rectovaginal fistula. There appears to be a genetic input as well because several families with multiple individuals having agenesis have been identified. This malformation is reported in 0.013% to 0.155% of autopsy series, but many of these cases are in stillborn and young infants. The surgical incidence of gallbladder agenesis is approximately 0.02%. Nearly two thirds of adult patients with agenesis of the gallbladder have biliary tract symptoms, and extrahepatic biliary calculi are reported in 25% to 50% of these patients. Preoperative diagnosis of gallbladder agenesis is difficult, and the absence of the gallbladder is often an intraoperative finding. Ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) may suggest the diagnosis, but this disorder is usually diagnosed at surgery when the gallbladder is not found at cholangiography. Intraoperative ultrasound may be helpful in establishing the diagnosis and excluding a completely intrahepatic gallbladder. Agenesis of the gallbladder is a rare cause of false-positive hepatobiliary scintiscans. Duplication of the Gallbladder Gallbladder duplication occurs in about 1 in 4000 people and 4.8% of domestic animals. This anomaly is caused by incomplete revacuolization of the primitive gallbladder, resulting in a persistent longitudinal septum that divides the gallbladder lengthwise. Another possible mechanism is the occurrence of separate cystic buds. To establish the diagnosis, two separate gallbladder cavities, each with its own cystic duct, must be present. These duplicated cystic ducts may enter the common duct separately or form a Y configuration before a common entrance. Most reported cases of gallbladder duplication have a clinical picture of cholecystitis with cholelithiasis in at least one of the gallbladders. Sometimes one of the gallbladders appears normal on oral cholecystography, whereas the second, diseased, nonvisualized, and unsuspected gallbladder produces symptoms. A number of entities can mimic the double gallbladder at sonography: folded gallbladder, bilobed gallbladder, choledochal cyst, pericholecystic fluid, gallbladder diverticulum, vascular band across the gallbladder, and focal adenomyomatosis. Complications associated with double gallbladder include torsion and the development of papilloma, carcinoma, common duct obstruction, and secondary biliary cirrhosis. Treatment of this disorder consists of removal of both gallbladders. Triple and quadruple gallbladders have also been reported. Diverticular gallbladders without cystic ducts are classified as accessory gallbladders. Anomalies of Gallbladder Shape Phrygian Cap Phrygian cap is the most common abnormality of gallbladder shape, occurring in 1% to 6% of the population. It is named after the headgear worn by ancient Greek slaves as a sign of liberation. This deformity is characterized by a fold or septum of the gallbladder between the body and fundus. Two variations of this anomaly have been described. In the retroserosal or concealed type, the gallbladder is smoothly invested by peritoneum, and the mucosal fold that projects into the lumen may not be visible externally. In the serosal or visible type, the peritoneum follows the bend in the fundus, then reflects on itself as the fundus overlies the body. This anomaly is of no clinical significance unless it is mistaken for a layer of stones or hyperplastic cholecystosis. Multiseptate Gallbladder The multiseptate gallbladder is a solitary gallbladder characterized by multiple septa of various sizes internally and a faintly bosselated surface externally. The gallbladder is usually normal in size and position, and the chambers communicate with one another by one or more orifices from fundus to cystic duct. These septations lead to stasis of bile and gallstone formation. On ultrasound studies, multiple communicating septations and locules are seen bridging the gallbladder lumen. Oral cholecystography reveals the “honeycomb” multicystic character of the gallbladder. The sonographic differential diagnoses are desquamated gallbladder mucosa and hyperplastic cholecystoses. Diverticula Gallbladder diverticula are rare and usually clinically silent. They can occur anywhere in the gallbladder and are usually single and vary greatly in size. Congenital diverticula are true diverticula and contain all the mural layers, as opposed to the pseudodiverticula of adenomyomatosis, which have little or no smooth muscle in their walls. Acquired traction diverticula from adjacent adhesions or duodenal disease must also be excluded. Abnormalities of Gallbladder Position Wandering Gallbladder When the gallbladder has an unusually long mesentery, it can “wander” or “float.” The gallbladder may “disappear” into the pelvis on upright radiographs or wander in front of the spine or to the left of the abdomen. Rarely, the gallbladder can herniate through the foramen of Winslow into the lesser sac. In these cases, cholecystography reveals an unusual angulation of the gallbladder, which lies parallel and adjacent to the duodenal bulb with its fundus pointing to the left upper quadrant. The herniation can be intermittent and may be responsible for abdominal pain. It is best seen by a barium meal in conjunction with oral cholecystography. Cross-sectional imaging may not be specific, showing only a cystic structure in the lesser sac. Gallbladder Torsion Three unusual anatomic situations give rise to torsion of the gallbladder, and they all produce twisting of an unusually mobile gallbladder on a pedicle: (1) a gallbladder that is completely free of mesenteric or peritoneal investments except for its cystic duct and artery, (2) a long gallbladder mesentery sufficient to allow twisting, and (3) the presence of large stones in the gallbladder fundus that cause lengthening and torsion of the gallbladder mesentery. Kyphosis, vigorous gallbladder peristalsis, and atherosclerosis have also been implicated as other predisposing or contributing factors. The mesentery is sufficiently long to permit torsion in 4.5% of the population. Most cases of gallbladder torsion occur in women (female-to-male ratio of 3 : 1). The usual preoperative diagnosis is acute cholecystitis. The presence of fever is variable, leukocytosis is common, and one third of patients have a right upper quadrant mass. Gangrene develops in more than 50% of cases and is extremely common when the pain has been present for more than 48 hours. On cross-sectional imaging, the gallbladder is distended and may have an unusual location and show mural thickening. The diagnosis is seldom made preoperatively, however. Ectopic Gallbladder The gallbladder can be located in a variety of anomalous positions. In patients with an intrahepatic gallbladder, the gallbladder is completely surrounded by hepatic parenchyma. The intrahepatic gallbladder usually presents little difficulty in imaging, but it may complicate the clinical diagnosis of acute cholecystitis because of a paucity of peritoneal signs resulting from the long distance between the gallbladder and peritoneum. This anomaly also makes cholecystectomy more difficult. On sulfur colloid scans, the intrahepatic gallbladder presents as a cold hepatic defect. The gallbladder has also been reported in the following positions: suprahepatic, retrohepatic ( Fig. 76-1 ), supradiaphragmatic, and retroperitoneal. In patients with cirrhosis, small or absent right lobes, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the gallbladder together with the colon is often interposed between the liver and the diaphragm. Left-sided gallbladders may occur in situs inversus or as an isolated finding. They can also lie in the falciform ligament, transverse mesocolon, and anterior abdominal wall. Figure 76-1 Gallbladder ectopia. A. Intrahepatic gallbladder (GB) demonstrated on CT scan. B. Retrohepatic gallbladder shown on an oral cholecystogram. C. Situs inversus with left-sided gallbladder. Abnormalities in Gallbladder Size Cholecystomegaly Enlargement of the gallbladder has been reported in a number of disorders including diabetes (because of an autonomic neuropathy) and after truncal and selective vagotomy. The gallbladder also becomes larger than normal during pregnancy, in patients with sickle hemoglobinopathy, and in extremely obese people. Microgallbladder In patients with cystic fibrosis, the gallbladder is typically small, trabeculated, contracted, and poorly functioning. It often contains echogenic bile, sludge, and cholesterol gallstones. These changes are presumably due to the thick, tenacious bile that is characteristic of this disease. Biliary Tract Anomalies Anomalies of the biliary system are found in 2.4% of autopsies, 28% of surgical dissections, and 5% to 13% of operative cholangiograms. The most common anomaly is an aberrant intrahepatic duct draining a circumscribed portion of the liver, such as an anterior or posterior segment right lobe duct that drains into the left main rather than the right main hepatic duct. The aberrant duct can join the common hepatic duct, common bile duct, or cystic duct or insert into a low right hepatic duct. Rarely, it may run through the gallbladder fossa or into the gallbladder, predisposing it to injury at cholecystectomy. The hepatic ducts may join either higher or lower than normal. Surgical difficulties may arise when the cystic duct enters into a low inserting right hepatic duct or when the right hepatic duct enters into the cystic duct before joining the left hepatic duct. Duplications of the cystic duct and common bile duct are rare. Anomalies of cystic duct insertion occur as well ( Fig. 76-2 ). Figure 76-2 Anatomic variants in the cystic duct. Drawings illustrate how the cystic duct may insert into the extrahepatic bile duct with a right lateral insertion ( A ), anterior spiral insertion ( B ), posterior spiral insertion ( C ), low lateral insertion with a common sheath ( D ), proximal insertion ( E ), or low medial insertion ( F ). (From Turner MA, Fulcher AS: The cystic duct: Normal anatomy and disease processes. RadioGraphics 21:3–22, 2001.) Congenital tracheobiliary fistula is a rare disorder that is manifested with respiratory distress and cough with bilious sputum. The fistula begins near the carina, traverses the diaphragm, and usually communicates with the left hepatic duct. Pneumobilia may be seen on plain radiography, and the diagnosis is confirmed with biliary scintigraphy. Choledochal cysts, choledochoceles, and Caroli’s disease are a part of a spectrum of biliary anomalies that produce dilation of the biliary tree. They are discussed individually in the following section, and their relationship is illustrated in Figure 76-3 .

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

- See All Locations

- Primary Care

- Urgent Care Facilities

- Emergency Rooms

- Surgery Centers

- Medical Offices

- Imaging Facilities

- Browse All Specialties

- Diabetes & Endocrinology

- Digestive & Liver Diseases

- Ear, Nose & Throat

- General Surgery

- Neurology & Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Orthopaedics

- Pain Medicine

- Pediatrics at Guerin Children’s

- Urgent Care

- Medical Records Request

- Insurance & Billing

- Pay Your Bill

- Advanced Healthcare Directive

- Initiate a Request

- Help Paying Your Bill

Overactive Bladder

The bladder is a hollow organ in the abdomen that holds urine. When the bladder is full, it contracts, and urine is expelled from the body through the urethra. Overactive bladder starts with a muscle contraction in the bladder wall. The result is a need to urinate (urinary urgency), which is also called urge incontinence or irritable bladder.

While overactive bladder is most common in older adults, the condition is not a normal result of aging. While one in 11 people in the United States suffer from overactive bladder, it mainly affects people 65 and older, although women can be affected earlier, often in their mid-forties.

There are two kinds of overactive bladder. One without urge incontinence, which is called overactive bladder, dry, and affects two thirds of sufferers; and overactive bladder, wet, which includes the symptoms with urge incontinence (leaking or involuntary bladder voiding).

- Frequent urination

- Urgency (need to urinate)

- Leaking or involuntary, and/or complete bladder voiding (urge incontinence)

- Need to urinate frequently (eight or more times in 24 hours)

- Nocturia or waking up two or more times at night to urinate

Overactive bladder is caused by a malfunction of the detrusor muscle, which in turn can be cased by:

- Nerve damage caused by abdominal trauma, pelvic trauma or surgery

- Bladder stones

- Drug side effects

- Neurological diseases, such as multiple sclerosis , Parkinson's disease , stroke or spinal cord lesions

- Bladder cancer

- Prostate cancer

- Urinary tract infection

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus

A preliminary assessment for suspected overactive bladder can include a screening questionnaire, a request that the patient maintain a voiding diary for a prescribed number of days, a detailed medical history, and a comprehensive physical examination. Often a urinalysis, which detects the presence of bacteria in urine and indicates infection, will be ordered to determine if the condition is caused by an infection. A urinalysis also can determine if there is blood or too much protein in the urine, which may indicate kidney or cardiac disease, and can also detect the presence of puss in urine, which is also a sign of infection.

The physical examination for overactive bladder includes checking the neurological status of a patient for any sensory issues, as well as a cough stress test to measure urine loss, whether as an immediate or a delayed reaction. The exam will usually include a check of the abdomen, rectum, genitals and pelvis.

Specialized diagnostics for overactive bladder are called urodynamic tests. They assess bladder function, measure the amount of urine after voiding, the degree of incontinence (how completely the bladder empties), and bladder irritability. Measurements are performed by inserting a thin tube through the urethra into the bladder or by performing an ultrasound to acquire an image of the bladder.

Other specialized tests include:

- Uroflowmetry is a diagnostic test that uses a device that measures the volume and speed of urination.

- Cystometry uses a device called a cystometer to measure the pressure of the bladder and its capacity. It also evaluates the function of the detrusor muscle to determine the degree of muscle contraction, the pressure of any leakage, and the pressure required to fully empty the bladder.

- Electromyography is used to assess the coordination of nerve impulses in the bladder muscles and in the urinary sphincter. Sensors are placed on the abdominal region or catheters are inserted into the urethra or rectum to measure the nerve impulses.

- Video Urodynamics uses imaging and ultrasound to create images of the bladder, both filled and after voiding.

- Cystoscopy is a test in which a thin tube with a camera at one end is used to see the interior of the urethra and the bladder.

In addition to medication, behavioral interventions for an overactive bladder may help reduce episodes and strengthen bladder muscles. Bladder training, which includes the delay of voiding from 10 minutes to two hours, can be done to strengthen bladder muscles. Pelvic floor muscle exercises, also called Kegel exercises, can improve function of the pelvic floor muscles and urinary sphincter to hold urine and suppress involuntary movement of the bladder. Vaginal weight training is a process by which small weights are held within the vagina through the tightening of the vaginal muscles. These exercises are recommended twice daily for approximately 15 minutes for four to six weeks. Biofeedback in combination with Kegel exercises can also help the patient build build awareness and control of pelvic muscles.

Other possible treatments include adjusting fluid intakes and reducing irritants, such as limiting caffeine and alcohol. Patients can also try increasing fiber intake or taking supplements for constipation, which can reduce the symptoms of overactive bladder.

In some cases, absorbent pads can be worn to protect undergarments and prevent embarrassment.

The use of antisasmodics, also called anticholinergics can reduce bladder urge episodes. These include:

- Tolterodine (Detrol)

- Oxybutynin (Ditropan)

- Oxybutynin skin patch (Oxytrol)

- Trospium (Sanctura)

- Solifenacin (Vesicare)

For severe cases of overactive bladder, a sacral nerve stimulator may be recommended. This is a pacemaker-type device placed under the skin of the abdomen and connected to a wire near the sacral nerves (near the tailbone). The sacral nerves are the primary link between the spinal cord and bladder tissue. Modulating these nerve impulses has been shown to be an effective treatment for overactive bladder.

In some cases, augmentation cystoplasty may be recommended. This is a reconstructive procedure that uses parts of the bowel to replace parts of the bladder. It can improve bladder capacity, although the use of a catheter for voiding may still be necessary.

Choose a doctor and schedule an appointment.

Get the care you need from world-class medical providers working with advanced technology.

Cedars-Sinai has a range of comprehensive treatment options.

(1-800-233-2771)

Available 7 days a week, 6 am - 9 pm PT

Expert Care for Life™ Starts Here

Looking for a physician.

Marla Carlson, P.A.

- Behavioral Health

- Children's Health (Pediatrics)

- Exercise and Fitness

- Heart Health

- Men's Health

- Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Orthopedic Health

- Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery

- Women's Health

Listen to your bladder: 10 symptoms that demand attention

- Urinary Incontinence

- Pelvic Health

Every day, you get direct feedback from a vital organ: your bladder. Most people urinate six to eight times a day, and this regular act can reveal much about your bladder's health.

Some messages are easier to explain. If you down a lot of water, it's likely that you'll need to urinate soon. Some medications, like diuretics or decongestants, can increase your need to urinate.

Some messages, however, are a sign of more serious issues like urinary tract infections, bladder stones, trauma, ureteral obstruction, an enlarged prostate or even bladder cancer. When you pay close attention to your bladder health, you're more likely to identify signs and symptoms earlier and help your healthcare team determine the cause.

Here are 10 bladder symptoms that you should discuss with your healthcare team:

1. frequent urination.

On average, most people urinate six to eight times in 24 hours. This varies based on the amount of liquid you drink, along with whether you are pregnant or taking medications that increase urination. A sudden increase in urination that can't be explained, especially at night, can be a sign of a bladder problem or diabetes. Dietary bladder irritants can also increase urinary frequency and urgency.

Most of the time, adults can hold their urine until they reach a restroom. A sudden, strong urge to urinate that's difficult to control can indicate a urinary tract infection, urge incontinence or other bladder conditions.

3. Incontinence

Involuntary leakage of urine is a common bladder condition. There are two types of incontinence. Stress incontinence occurs when a person coughs, laughs or sneezes. It can also happen during physical activities. Urge incontinence happens after a sudden and intense urge to urinate, quickly followed by the involuntary loss of urine. You can have both types of incontinence.

4. Painful urination

Urinating shouldn't be painful. A burning or stinging sensation while urinating can be a sign of bladder issues like a urinary tract infection or bladder stones.

5. Hematuria

It can be scary to see blood in your urine, also called hematuria. Blood in the urine can be a sign of a serious illness such as kidney or bladder stones, an infection, or bladder or kidney cancer. Sometimes blood can be seen and appears pink, red or brown. In other cases, it can only be detected by a microscope when a lab tests the urine. Either way, it's important to figure out the reason for the bleeding.

6. Difficulty emptying the bladder

Most people feel relief when the bladder is emptied. But if you can't completely empty your bladder after urinating, it can be a sign of bladder dysfunction.

7. Weak urine stream

Changes in urine stream strength often develop over time, especially with age. A weak or interrupted urine stream could be a symptom of an enlarged prostate in men.

8. Pain or pressure

Pelvic pain can feel like a dull ache, built-up pressure or a sharp, localized pain. In addition to the pelvic area, the pain can be in your lower abdomen or back. While there are many possible causes of pelvic pain or pressure, it can be related to bladder issues.

9. Recurrent urinary tract infections

Frequent infections can be a sign of an underlying bladder problem. You may have chronic or recurrent bladder infections if you have two or more bladder infections in six months or three or more infections in a year.

10. Nocturia

Waking up more than once each night to pass urine is called nocturia. This can disrupt your sleep pattern and can be a sign of many different bladder issues or underlying health issues like obstructive sleep apnea or glucosuria, which is glucose in the urine.

It's important to understand that symptoms vary based on the type and severity of any bladder condition, your lifestyle and whether you have other chronic health conditions.

Talk with your healthcare team if you're experiencing any of these symptoms. After a thorough exam and tests, they can determine the cause of your symptoms and recommend appropriate treatment options.

Marla Carlson is a physician assistant in Urology in Red Wing , Minnesota.

Related Posts

)

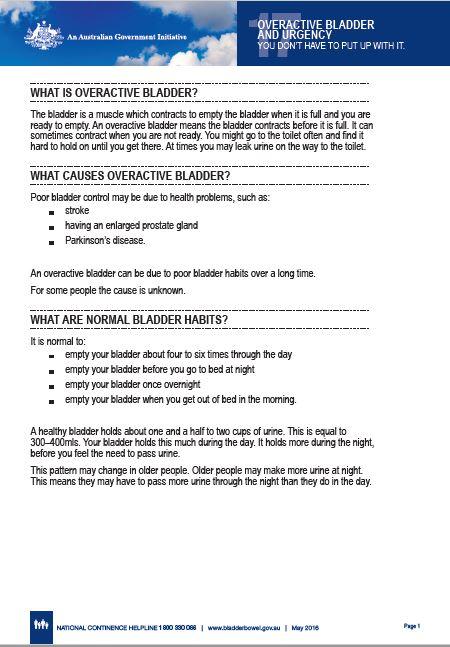

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care

Overactive bladder and urgency

An overactive bladder can cause bladder control problems. This fact sheet outlines what those problems can be, what causes it and how to manage it.

Scroll down to access downloads and media.

Download [Publication] Overactive bladder and urgency (PDF) as PDF - 242.93 KB - 6 pages

Download [Publication] Overactive bladder and urgency (Word) as Word - 202.37 KB - 4 pages

We aim to provide documents in an accessible format. If you're having problems using a document with your accessibility tools, please contact us for help .

An overactive bladder can cause bladder control problems. This fact sheet covers:

- what is an overactive bladder

- what causes an overactive bladder

- what are normal bladder habits

- what is a bladder training program

- where to get help

- Bladder and bowel

Is there anything wrong with this page?

Help us improve health.gov.au

If you would like a response please use the enquiries form instead.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Urol

- v.35(1); Jan-Mar 2019

Female underactive bladder – Current status and management

Tammer yamany.

Department of Urology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA

Marlie Elia

1 Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Jason Jihoon Lee

Ajay k. singla.

Underactive bladder (UAB) is defined by the International Continence Society as a symptom complex characterized by a slow urinary stream, hesitancy, and straining to void, with or without a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying sometimes with storage symptoms. Until recently, the topic has received little attention in the literature probably due to a lack of consistent definitions and diagnostic criteria. We performed a literature review to identify articles related to the diagnosis and management of UAB, specifically in female patients. UAB is a common clinical entity, occurring in up to 45% of females depending on definitions used. Prevalence increases significantly in elderly women and women who live in long-term care facilities. The exact etiology and pathophysiology for developing UAB is unknown, though it is likely a multifactorial process with contributory neurogenic, cardiovascular, and idiopathic causes. There are currently no validated questionnaires for diagnosing or monitoring treatment for patients with UAB. Management options for females with UAB remain limited, with clean intermittent catheterization, the most commonly used. No pharmacotherapies have consistently been proven to be beneficial. Neuromodulation has had the most promising results in terms of symptom improvement, with newer technologies such as stem-cell therapy and gene therapy requiring more evidence before widespread use. Although UAB has received increased recognition and has been a focus of research in recent years, there remains a lack of diagnostic and therapeutic tools. Future research goals should include the development of targeted therapeutic interventions based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and validated diagnostic questionnaires.

INTRODUCTION

There are two methods of categorizing bladder dysfunction due to underactivity. According to the International Continence Society (ICS), underactive bladder (UAB) syndrome is “characterized by a slow urinary stream, hesitancy, and straining to void, with or without a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying sometimes with storage symptoms.”[ 1 ] Diagnosis of UAB is made based on clinical symptoms and can have a highly variable presentation. This differs from detrusor underactivity (DU), which is a diagnosis based on urodynamic studies (UDSs). DU is defined by ICS as a bladder contraction of reduced strength and/or duration resulting in prolonged or incomplete emptying of the bladder, and acontractile detrusor is specified when there is no contraction. While UAB and DU certainly coexist in many patients, the focus of this review will be the UAB in female patients.

Until recently, this topic has received little attention in the literature probably due to a lack of consistent definitions and diagnostic criteria.[ 2 ] In men, UAB has traditionally been difficult to study because of the difficulty in distinguishing UAB from bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) without the usage of pressure flow studies.[ 3 ] However, it has been proposed that by studying the presence of DU and UAB in women, in whom BOO is rarely diagnosed, it might be possible to isolate the clinical symptomatology specific to UAB and continue to refine its clinical definition.[ 3 ] DU is a common entity occurring in up to 13.3% of elderly women with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) with the prevalence of clinically diagnosed UAB certainly exceeding that number.[ 4 ] In recent years, UAB has been recognized as contributing significantly to LUTS in the elderly and interest in the topic has grown.[ 5 , 6 ] In this review, we will focus on the definition, epidemiology, and etiology of female UAB. We will also discuss further advances in the diagnosis and management of female UAB that have come about from new understandings of the disease process.

DEFINITIONS

Chapple et al. proposed a working definition of UAB to correspond to the urodynamic finding of DU as “a symptom complex suggestive of detrusor underactivity and is usually characterized by prolonged urination time with or without a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, usually with hesitancy, reduced sensation on filling, and a slow stream.”[ 7 ] In 2017, the Congress on UAB endorsed and refined this definition, more specifically defining UAB as “a symptom complex suggestive of DU and is usually characterized by prolonged urination time with or without a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, usually with hesitancy, reduced sensation on filling, slow stream, palpable bladder, always straining to void, enuresis, and/or stress incontinence.”[ 8 ]

Only recently has the ICS given a consensus definition for UAB, which will likely act as a guiding definition for clinical and research purposes. As stated earlier, UAB is “characterized by a slow urinary stream, hesitancy, and straining to void, with or without a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying sometimes with storage symptoms.”[ 1 ] The important distinction of both the Congress on UAB and ICS definitions is that UAB is a symptom syndrome. Presentation and etiology can and will be highly variable between patients. However, the establishment of a consensus definition will encourage clinicians to consider UAB as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with lower urinary tract voiding symptoms.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

UAB as an entity remains difficult to study in part because its corresponding urodynamic correlate remains loosely defined, leading to significant variability in diagnostic criteria across research studies. Because of the variability in definition, reported prevalence also varies significantly. It is believed to range from 12% to 45% of females with increased prevalence with age.[ 2 , 4 ] Resnick et al. looked specifically at a population of women with incontinence in a long-term care facility. Overall, 38% of these women had impaired detrusor function, with DU in 8% of patients and involuntary detrusor contractions with incomplete emptying in 30%.[ 9 ] In a follow-up study, nearly one-quarter of women with DU on UDS had been misdiagnosed with stress urinary incontinence.[ 10 ]

In the ambulatory setting, DU is less common than in the long-term care facility setting. Of 206 consecutive women seen in the urogynecology practice, 62% of women self-reported voiding difficulties and 19.4% of women had demonstrable evidence of DU as characterized by incomplete emptying.[ 11 ] Interestingly, only 68% of women with incomplete emptying on UDS reported voiding symptoms. It is not clear if the disease processes that lead to DU affect a patient's symptomatology and perception of UAB or incomplete emptying. If so, this may explain why 32% of patients in this study have incomplete emptying on UDS consistent with DU and do not perceive symptoms of UAB.

Overall trends suggest that DU and UAB are more common in elderly women and more common in women residing in a long-term care facility. Several studies have demonstrated similar prevalence rates for DU in the ambulatory setting of around 12%–19.4%.[ 4 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] As would be expected, voiding symptoms consistent with UAB are slightly higher. A population-wide study in Detroit surveyed 291 women with 20% reporting difficulty with emptying their bladder.[ 14 ]

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

There is a controversy as to the exact etiology and pathophysiology underlying UAB. In a broad sense, impaired bladder emptying characteristic of UAB can arise from damage or malfunction of peripheral afferent, efferent, or central nervous system pathways, and detrusor myopathy.[ 3 ] Impaired afferent or sensory signaling, which is common with aging and diabetic cystopathy, can impair the micturition reflex leading to impaired emptying.[ 2 ] Impaired efferent or motor signaling due to peripheral nerve malfunction or injury can lead directly to impaired contractility. Neural signaling through central nervous system pathways, particularly from the pontine micturition center through the lumbosacral cord, is essential for generating adequate detrusor contractions. Disruptions of the central neural pathways can arise from many pathologic processes including spinal cord injuries, spinal stenosis, and malignancy or vascular insults. Detrusor myopathy is characterized by unfavorable smooth muscle remodeling and myogenic failure. It may result from neuropathy or it may be idiopathic. Some factors that may lead to detrusor myopathy include BOO, aging, denervation, ischemia, or inflammation. UAB often coexists with overactive bladder, though the disease processes appear distinct.[ 3 ]

Idiopathic causes, cardiovascular insults, and neurogenic causes may all underlie eventual development of UAB through the previously described pathophysiologic pathways.[ 15 , 16 ] A recent retrospective study of 1726 patients believed to suffer from UAB found that based on patient history, 11.5% of patients would fall into the idiopathic subclass, with neurogenic causes accounting for 84.6% and myogenic causes 2.6%.[ 5 ] However, a 2016 retrospective study of 4 years of patients with UAB at one institution was unsuccessful in finding a correlation between clinical and urodynamic variables and etiologies of UAB.[ 6 ] A lack of distinct differentiation between etiological groups supports the idea that UAB more typically presents in a multifactorial fashion, or through converging pathways, rather than through clearly distinct underlying pathophysiological pathways.

Patients with UAB often present in a similar fashion to patients with general LUTS. As such, the initial evaluation should be similar. All patients should undergo a history and physical examination, with specific attention paid to bowel habits, prior abdominal or pelvic surgeries, prior traumas, medications, neurologic history, physical examination, and pelvic floor examination. We recommend as first-line tests urinalysis and postvoid residual (PVR). Given low incidence of BOO in women, uroflowmetry can be particularly useful to identify patients with low flow. Although a specific cutoff for maximum flow rate characteristic of UAB has not been defined, there are typical findings. Uroflowmetry typically shows a slow take-off with low maximum flow rate, prolonged voiding time, and multiple intervals.[ 1 ]

There do not currently exist any validated patient symptom score scales for use in the diagnosis of UAB.[ 17 ] For the purposes of setting patient inclusion criteria, researchers have used urodynamic evidence of DU to identify patients likely presenting with UAB symptomology.[ 6 , 18 ]

In a retrospective qualitative study of 29 males and 15 females previously shown to have DU by urodynamic testing, Uren et al. performed structured interviews to establish a patient-centered perspective of DU symptoms.[ 17 ] Patients reported a wide variety of LUTS and associated impact on quality of life. Over half of the patients reported storage symptoms (nocturia, frequency, and urgency) and voiding symptoms (slow stream, hesitancy, and straining). Incomplete emptying and postvoid dribbling were also common. This study provided key insight into the experience of patients with UAB and confirmed DU. However, the lack of a comparative group without DU limits the ability to identify symptoms and complaints unique to the subgroup of patients with LUTS symptoms secondary to DU. There remains a need to develop a patient-reported outcome measure for the assessment of UAB with the goal of avoiding invasive testing.

In another retrospective study, Gammie et al. reviewed the pressure flow and symptom endorsement data of 1788 patients presenting at a single center over a 28-year period and compared the results of patients found to have normal flow, DU, and BOO to isolate the symptoms most related to UAB and DU.[ 18 ] The goal was to identify the characteristics specific to patients with DU. Women with DU were found to have a higher occurrence of decreased and/or interrupted urinary stream, hesitancy, feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, palpable bladder, absent and/or decreased sensation, enuresis, and impaired mobility compared with women with normal PFS.

Jeong et al. performed a similar retrospective review of 547 Korean women older than 65 years who had undergone UDS in the outpatient setting for LUTS.[ 4 ] About 13.3% of women were classified as having DU. Women with DU were significantly older than women without DU, and the prevalence of DU increases with age. In contrast to Gammie et al. , clinical urinary symptoms, including storage symptoms, voiding symptoms, postmicturition symptoms, and stress urinary incontinence, were identical between the two groups. Despite the contradiction between the two studies, both papers support the need to identify a validated assessment questionnaire for UAB.

The necessity of urodynamic pressure-flow studies for specifying DU in patients with suspected UAB has not been proven. In men, differentiating BOO from DU can be difficult, which often makes UDS necessary to perform. However, the incidence of BOO in women with LUTS is very low, which may obviate the need for urodynamic testing.[ 4 , 19 ] Given the lack of a noninvasive diagnostic algorithm for UAB, urodynamic testing is often performed, which may demonstrate DU. Diagnosis of DU requires a contraction of reduced strength and/or duration resulting in prolonged or incomplete bladder emptying. Additional UDS findings of DU may include delayed start of bladder contraction and delayed urine flow despite desire to void. The detrusor trace may demonstrate a wandering pattern. Patients often rely on abdominal straining to enhance urine flow.[ 1 ]

While the rate of isolated BOO in women is low, there may be a subset of women who have a combination of DU and BOO. Wang et al. identified DU in 19.9% of women with LUTS, with 4.0% of those women having demonstrable BOO.[ 20 ] In women for whom there is uncertainty as to the etiology of LUTS or who are unresponsive to first-line therapies, urodynamics may be beneficial to identify a subset of patients with combined DU and BOO. In particular, video urodynamics may allow for the identification of anatomic obstruction, which in many cases can be surgically addressed.[ 21 ]

There are currently no proven therapeutic options to treat UAB; however, many behavioral modifications and medication therapies have been proposed. There are two goals for the management of patients with UAB: symptomatic/risk management and therapeutic management. The options available for symptomatic management include behavior modification therapy, pelvic floor physiotherapy and biofeedback, and catheterization.

Behavior modification therapy is useful for patients with impaired bladder sensation who may not sense bladder distension. Timed voiding and double voiding should be encouraged to avoid overdistension and assist with incomplete emptying. This may have the added benefit of reducing frequency and/or incontinence in these patients. Voiding diaries can be important for identifying patients who chronically over-hydrate and can worsen the symptoms of UAB. These patients may benefit from a fluid restriction program. Patients can also perform Crede maneuver using manual pressure on the abdomen to apply pressure to the bladder to further promote bladder emptying. However, this technique should be avoided in patients with BOO as it may lead to vesicoureteral reflux and is cautioned in women as it may lead to increased UTIs due to stop-start voiding.[ 22 ]

Pelvic floor physiotherapy and biofeedback have not been directly studied in the female UAB population. Ladi-Seyedian et al. performed a randomized trial in two groups of children with nonneuropathic UAB looking at the benefits of animated biofeedback.[ 23 ] Both groups received behavioral modification therapy and education, while one group also received pelvic floor physiotherapy and biofeedback training with the assistance of animated imaging. The group that received pelvic physiotherapy demonstrated significantly improved bladder contractility with improved sensation of bladder fullness. While the results are promising, they have not been extended to the adult population in which the etiology of UAB may differ.

In UAB patients with incomplete emptying and high PVR volumes, clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) should be considered. CIC reduces many risks of incomplete emptying, including urinary tract infections, upper tract deterioration, and overflow incontinence. CIC is an adequate management strategy for many patients, but it is not known to be therapeutic. It is the most commonly used management strategy for UAB.[ 24 ]

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Many therapeutic management options have been proposed. In theory, therapeutic interventions for UAB should have a basis in the pathophysiologic mechanisms of UAB.

The human bladder has five types of muscarinic receptors, with M2 the most prevalent and M3 the most important for detrusor contraction. In theory, muscarinic agonists and anticholinesterase inhibitors can increase the concentration of acetylcholine at the muscarinic receptor allowing for a strong bladder contraction. One of the more commonly prescribed medications for UAB is bethanechol, which is a nonselective muscarinic agonist.[ 25 ] Other parasympathomimetics that have been studied in the literature include carbachol and distigmine.[ 26 , 27 ] Results of multiple randomized controlled trials looking at the benefit of parasympathomimetics in patients with UAB have been mixed.[ 25 ] There has been no definitive evidence proving benefit. In addition, the side effect profile of parasympathomimetics is significant, including GI upset, blurred vision, bronchospasm, and bradycardia. For this reason, bethanechol and other parasympathomimetics are not recommended to treat UAB.

There has been an argument made to the potential benefit of alpha-adrenergic antagonists, such as tamsulosin, which function by decreasing sympathetic tone at the bladder neck and decreasing urethral muscle tone. This decreases the pressure against which the bladder needs to empty, which in turn may allow increased bladder emptying and improved UAB symptoms.[ 28 ] Yamanishi et al. studied the combined use of alpha-blockers and parasympathomimetics in women with UAB.[ 29 ] They found that the combined therapy was superior to either monotherapy in regard to improvement in voiding parameters and subjective symptoms. In the same study, alpha blockers were superior to parasympathomimetics alone. Of note, the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was used to assess voiding symptoms in men and women in this study. While the use of IPSS has not been validated for this purpose, there likely remains benefit in tracking progression of symptoms over time and response to treatment.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been used to treat DU in humans.[ 30 , 31 ] Prostaglandins are known to be important in the modulation of bladder function.[ 32 , 33 ] The intravesical instillation of prostaglandins to promote earlier return of bladder activity has been studied in patients with postoperative urinary retention and DU.[ 34 , 35 , 36 ] Overall, results have been mixed, and intravesical prostaglandins are not recommended at this time. In addition, results are difficult to generalize to the general female UAB population given the different pathophysiologies. However, there are currently promising animal studies looking at a novel selective PGE2 and PGE3 receptor agonist in a rat lumbar spinal canal stenosis model for UAB/DU.[ 37 ] The prostaglandin selective agonist resulted in improved voiding parameters with decreased PVR due to increased bladder contractility and urethral muscle relaxation. While the results have not been extended to humans yet, the drug is promising.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN PHARMACOTHERAPY

To our knowledge, no other medical therapies have been reported in humans for the treatment of female UAB. Clearly, there remains a need to identify new drug therapies for the treatment of UAB. Chai and Kudze nicely theorize potential areas for investigation in their review paper by breaking down the voiding process from central nervous system to peripheral nervous system to the lower urinary tract at a macroscopic and microscopic level.[ 38 ] Theoretical targets of therapy at the motor or efferent system level that are discussed include ATP regulation, potassium channels, and excitation-contraction coupling through intracellular calcium concentrations. Three different mechanisms for modulating the bladder sensory or afferent system are discussed. In theory, by increasing bladder sensation, the downstream motor or efferent system can be amplified. The potential therapeutic targets discussed include bladder sensory-related neurotransmitters, suburothelial myofibroblasts that function as pacemaker cells within the lamina propria and communicate with afferent nerve fibers, and urothelial cells that are also part of the urothelial-afferent system.

NEUROMODULATION

Sacral neuromodulation is an FDA approved therapy for patients with UAB as a means of improving voluntary voiding. In patients with neurogenic UAB, neuromodulation has been proposed as a mechanism through which a patient's malfunctioning neural system can be altered to allow adequate voiding. In theory, sacral neuromodulation may have the benefit of increasing detrusor contractility while decreasing outflow resistance. A number of trials have been published with overall promising results, demonstrating that sacral neuromodulation appears to decrease PVR volumes and/or the number of self-catheterization episodes per day.[ 39 ] It appears that the results of sacral neuromodulation with an implanted device are durable with >80% of patients demonstrating >50% improvement in symptoms after 5 years.[ 40 ] Measurable outcomes, such as increased detrusor contractility or decreased outflow resistance, have not been studied as closely.

Future studies for neuromodulation may focus on the central nervous system and closed-loop feedback neuromodulation. Mouse models have shown that stimulation of specific loci in the brain can induce increased voiding frequency.[ 41 ] Theoretically, transcranial stimulation in humans could target similar specific loci to increase voiding frequency. It is unknown if this technique could increase bladder contractility as well.

Closed-loop feedback neuromodulation allows for monitoring of bladder filling through sensory pathways and bladder stimulation through motor pathways. The process is automated and does not require patient input, as such bladder stimulation is induced when a full bladder is detected. The concept has been demonstrated in a rat model with improved voiding parameters after intervention.[ 42 ]

STEM-CELL THERAPY

Stem-cell therapy has been proposed as a mechanism of therapy for patients with UAB caused by detrusor cell malfunction. Stem cells are pluri- or multipotent cells capable of regenerating and differentiating into more specialized cells. Stem cells in recent years become an increasingly popular area of research due to their potential use in the treatment of various diseases. The bladder is known to contain multipotent progenitor cells that can regenerate the urothelium and detrusor after injury.[ 43 , 44 ] It is unknown if these progenitor cells can be utilized to regenerate malfunctioning detrusor cells in patients with UAB and DU.

Animal studies have demonstrated that the injection of mesenchymal stem cells, which are derived from the bone marrow, can prevent the development of DU after ischemia.[ 45 , 46 ] Other studies have looked at the use of autologous muscle-derived cells (ADMCs). Animal models demonstrated the development of myofibroblasts and myotubes after injection of ADMCs.[ 47 ] A single case of ADMC injection into a 79-year-old man with UAB has been reported.[ 48 ] At 3 months, the patient achieved improved voiding and pressure parameters on UDS with decreased bladder volume and decreased CIC frequency. To our knowledge, ADMC injection into a female UAB patient has not been attempted or described.

GENE THERAPY

Gene therapy is the delivery of genetic material into a patient's cells to treat disease. In the realm of female UAB, gene therapy remains experimental. Nerve growth factor (NGF) levels have been demonstrated to be decreased in neurogenic-type DU.[ 49 ] Therefore, the gene of choice for therapy of neurogenic DU is NGF. The NGF gene is introduced into sensory ganglia cells of the bladder using herpes simplex virus. Rats with DU transfected with the NGF gene demonstrate decreased bladder capacity and PVR.

SURGICAL THERAPY

Various surgical therapies for reducing outflow resistance in patients with UAB and DU have been studied. OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections to the urethral sphincter have been used in patients with both neurogenic and nonneurogenic DU.[ 50 ] The benefits of Botox appear to be twofold. First, Botox can paralyze the striated urethral sphincter, which in turn can decrease urethral resistance. Second, Botox injections may eliminate the inhibitory effect of urethral afferent nerves on detrusor activity. Urethral sphincter Botox injections have been demonstrated to reduce voiding pressures, reduce PVR volumes, and increase detrusor contractility.[ 51 , 52 ]

Transurethral incision of the bladder neck (TUI-BN) has been reported as a surgical management strategy for women with DU who have failed medical therapy. Jhang et al. reported a case series of 31 women with DU who underwent TUI-BN.[ 21 ] They found that PVR decreased by 56.3% and 20 out of 27 patients no longer required CIC. Of note, three patients developed transient incontinence, and one developed a vesicovaginal fistula.

Myoplasty has been used with success in patients with acontractile bladder.[ 53 ] Myoplasty describes the process of transferring autologous latissimus dorsi muscle flaps from the axilla to the bladder. The muscle flap is draped over the bladder. Because the neural bundle of the flap is anastomosed to the 12 th intercostal nerve, patients can voluntarily control the muscular flap. Long-term results have demonstrated that 17 out of 24 patients gained voluntary control of voiding with low PVRs and no need for CIC. The procedure has not been performed in women with UAB, so it is unclear what the functional and symptomatic effects of myoplasty would be on this patient population.

UAB is a symptom complex characterized by a “slow urinary stream, hesitancy, and straining to void, with or without a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying sometimes with storage symptoms.” UAB is a common, though underdiagnosed, clinical entity that has only recently been given formal recognition and definition by the ICS. Most studies of UAB have focused on patients with UAB and DU secondary to long-standing BOO, which is much less common in female patients. However, we know that UAB and DU are common in elderly women and women residing in long-term care facilities. There are currently no validated patient symptom-based tools to aid the diagnosis and management of UAB. Management strategies have not been directly studied in the female UAB patient population, though various therapies for DU have been studied with mixed results. Future research goals should include the development of targeted therapeutic interventions based on pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Financial support and sponsorship:

Conflicts of interest:.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Bladder cancer

- What is bladder cancer? A Mayo Clinic expert explains

Learn more about bladder cancer from urologist Mark Tyson, M.D., M.P.H.

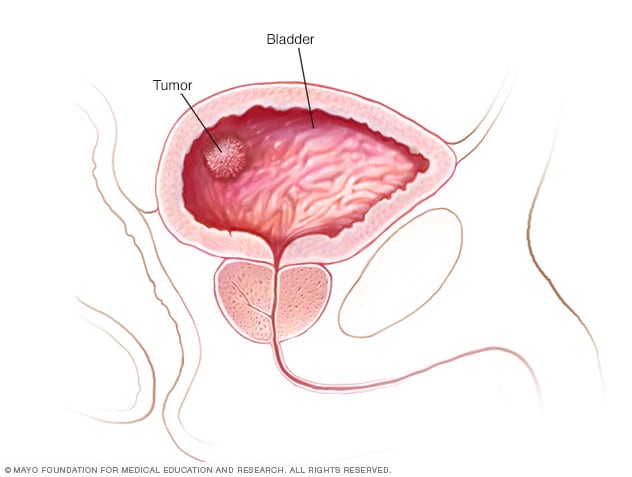

Hi. I'm Dr. Mark Tyson, a urologist at Mayo Clinic. In this video, we'll cover the basics of bladder cancer: What is it? Who gets it? The symptoms. Diagnosis and treatment. Whether you're looking for answers for yourself or someone you love, we're here to give you the best information available. Bladder cancer is almost always one certain type of cancer called urothelial carcinoma, because it starts when urothelial cells that line the inside of the bladder over multiply and become abnormal. Most bladder cancer is caught in the early stages and therefore very treatable.

While bladder cancer can happen to anyone, it affects certain groups more than others. For instance, smokers. As the bladder works to filter the harmful chemicals ingested in cigarette smoke, it becomes damaged. In fact, smokers are three times more likely to get bladder cancer. People over the age of 55 are more at risk, as are men, more than women. Exposure to harmful chemicals, either at home or at work, previous cancer treatments, chronic bladder inflammation, or a family history of bladder cancer can also play a role.

Bladder cancer symptoms are usually clear and easy to notice. If any of these symptoms are present, it may be worth making an appointment to see a doctor: Blood in the urine, frequent urination, painful urination or back pain. Your doctor may investigate the more common causes of the symptoms first, or may refer you to a specialist, like a urologist or an oncologist.

To determine if you have bladder cancer, your doctor may start with a cystoscopy, where a tiny camera is passed through the urethra to see into the bladder. If your doctor finds something suspicious, they can take a biopsy or a cell sample that is sent to a lab for analysis. In some cases, your doctor may do a urine cytology, where they examine a urine sample under a microscope to check for cancer cells. Or they may even do imaging tests of your urinary tract, like a CT urogram or a retrograde pyelogram. In both procedures, a safe dye is injected and travels to your bladder, illuminating the cancer cells so they can be seen in X-ray images.

When creating a treatment plan for bladder cancer, your doctor is considering several factors, including the type and stage of cancer and your treatment preferences. There are five types of treatment options for bladder cancer: Surgery to remove the cancerous tissue. Chemotherapy, which uses cancer-cell-killing chemicals that can travel either locally into the bladder or through the whole body, if needed. Radiation therapy, which uses high-power beams of energy to target cancer cells. Targeted drug therapy focusing on blocking specific weaknesses present within cancer cells. And immunotherapy, a drug treatment that helps your immune system recognize cancer cells and attack them.

Getting a cancer diagnosis or worrying that cancer will return can be very stressful. However, there are ways to feel more in control and deal with less stress. Stay on top of your follow-up tests and appointments. Even though they might feel uncomfortable or unpleasant, ultimately, they can empower you and your health. Take care of yourself outside of your appointments. Be good to your body with plenty of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, consistent exercise and the ever important sleep. Be good to your mind. Try different methods to cope with stress, like journaling or meditation. Maybe find a support group of cancer survivors who understand how you're feeling. If you'd like to learn even more about bladder cancer, watch our other related videos or visit mayoclinic.org. We wish you well.

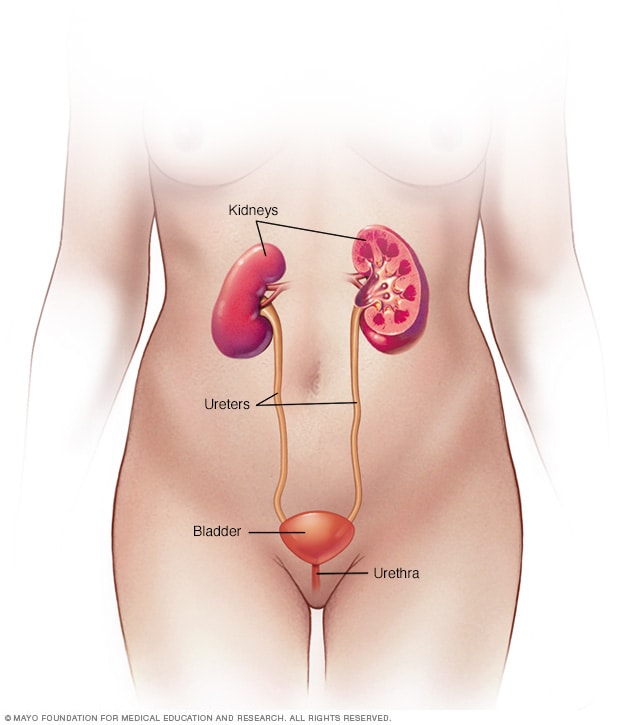

Female urinary system

Your urinary system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. The urinary system removes waste from the body through urine. The kidneys are located toward the back of the upper abdomen. They filter waste and fluid from the blood and produce urine. Urine moves from the kidneys through narrow tubes to the bladder. These tubes are called the ureters. The bladder stores urine until it's time to urinate. Urine leaves the body through another small tube called the urethra.

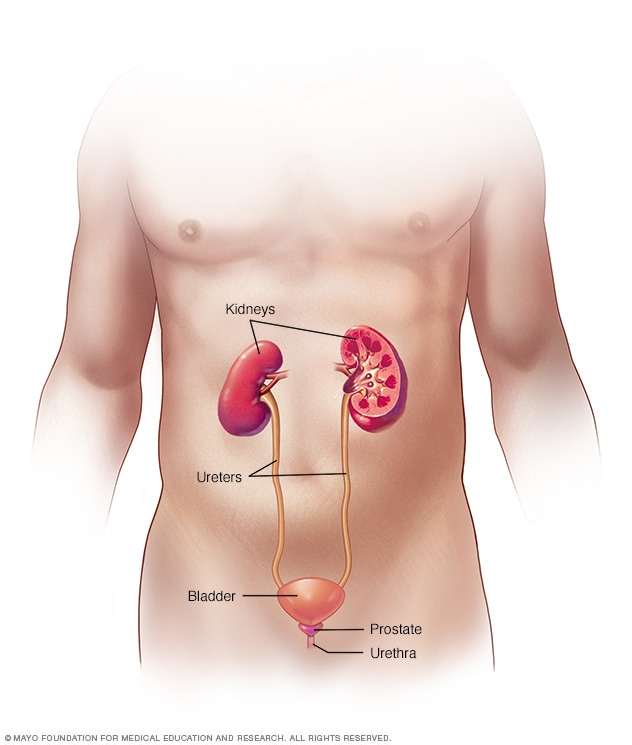

Male urinary system

Bladder cancer is a common type of cancer that begins in the cells of the bladder. The bladder is a hollow muscular organ in your lower abdomen that stores urine.

Bladder cancer most often begins in the cells (urothelial cells) that line the inside of your bladder. Urothelial cells are also found in your kidneys and the tubes (ureters) that connect the kidneys to the bladder. Urothelial cancer can happen in the kidneys and ureters, too, but it's much more common in the bladder.

Most bladder cancers are diagnosed at an early stage, when the cancer is highly treatable. But even early-stage bladder cancers can come back after successful treatment. For this reason, people with bladder cancer typically need follow-up tests for years after treatment to look for bladder cancer that recurs.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Assortment of Pill Aids from Mayo Clinic Store

- Available Ostomy Supplies from Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Bladder cancer signs and symptoms may include:

- Blood in urine (hematuria), which may cause urine to appear bright red or cola colored, though sometimes the urine appears normal and blood is detected on a lab test

- Frequent urination

- Painful urination

When to see a doctor

If you notice that you have discolored urine and are concerned it may contain blood, make an appointment with your doctor to get it checked. Also make an appointment with your doctor if you have other signs or symptoms that worry you.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Bladder cancer develops when cells in the bladder begin to grow abnormally, forming a tumor in the bladder.

Bladder cancer begins when cells in the bladder develop changes (mutations) in their DNA. A cell's DNA contains instructions that tell the cell what to do. The changes tell the cell to multiply rapidly and to go on living when healthy cells would die. The abnormal cells form a tumor that can invade and destroy normal body tissue. In time, the abnormal cells can break away and spread (metastasize) through the body.

Types of bladder cancer

Different types of cells in your bladder can become cancerous. The type of bladder cell where cancer begins determines the type of bladder cancer. Doctors use this information to determine which treatments may work best for you.

Types of bladder cancer include:

- Urothelial carcinoma. Urothelial carcinoma, previously called transitional cell carcinoma, occurs in the cells that line the inside of the bladder. Urothelial cells expand when your bladder is full and contract when your bladder is empty. These same cells line the inside of the ureters and the urethra, and cancers can form in those places as well. Urothelial carcinoma is the most common type of bladder cancer in the United States.

- Squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinoma is associated with chronic irritation of the bladder — for instance, from an infection or from long-term use of a urinary catheter. Squamous cell bladder cancer is rare in the United States. It's more common in parts of the world where a certain parasitic infection (schistosomiasis) is a common cause of bladder infections.

- Adenocarcinoma. Adenocarcinoma begins in cells that make up mucus-secreting glands in the bladder. Adenocarcinoma of the bladder is very rare.

Some bladder cancers include more than one type of cell.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase bladder cancer risk include:

- Smoking. Smoking cigarettes, cigars or pipes may increase the risk of bladder cancer by causing harmful chemicals to accumulate in the urine. When you smoke, your body processes the chemicals in the smoke and excretes some of them in your urine. These harmful chemicals may damage the lining of your bladder, which can increase your risk of cancer.

- Increasing age. Bladder cancer risk increases as you age. Though it can occur at any age, most people diagnosed with bladder cancer are older than 55.

- Being male. Men are more likely to develop bladder cancer than women are.

- Exposure to certain chemicals. Your kidneys play a key role in filtering harmful chemicals from your bloodstream and moving them into your bladder. Because of this, it's thought that being around certain chemicals may increase the risk of bladder cancer. Chemicals linked to bladder cancer risk include arsenic and chemicals used in the manufacture of dyes, rubber, leather, textiles and paint products.

- Previous cancer treatment. Treatment with the anti-cancer drug cyclophosphamide increases the risk of bladder cancer. People who received radiation treatments aimed at the pelvis for a previous cancer have a higher risk of developing bladder cancer.

- Chronic bladder inflammation. Chronic or repeated urinary infections or inflammations (cystitis), such as might happen with long-term use of a urinary catheter, may increase the risk of a squamous cell bladder cancer. In some areas of the world, squamous cell carcinoma is linked to chronic bladder inflammation caused by the parasitic infection known as schistosomiasis.

- Personal or family history of cancer. If you've had bladder cancer, you're more likely to get it again. If one of your blood relatives — a parent, sibling or child — has a history of bladder cancer, you may have an increased risk of the disease, although it's rare for bladder cancer to run in families. A family history of Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), can increase the risk of cancer in the urinary system, as well as in the colon, uterus, ovaries and other organs.

Although there's no guaranteed way to prevent bladder cancer, you can take steps to help reduce your risk. For instance:

- Don't smoke. If you don't smoke, don't start. If you smoke, talk to your doctor about a plan to help you stop. Support groups, medications and other methods may help you quit.

- Take caution around chemicals. If you work with chemicals, follow all safety instructions to avoid exposure.

- Choose a variety of fruits and vegetables. Choose a diet rich in a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables. The antioxidants in fruits and vegetables may help reduce your risk of cancer.

Bladder cancer care at Mayo Clinic

Living with bladder cancer?

Connect with others like you for support and answers to your questions in the Cancer support group on Mayo Clinic Connect, a patient community.

Cancer Discussions

21 Replies Fri, Apr 26, 2024

47 Replies Thu, Apr 25, 2024

76 Replies Wed, Apr 24, 2024

- AskMayoExpert. Bladder cancer (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2018.

- Bladder cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Partin AW, et al., eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Bladder cancer treatment (PDQ). National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/bladder/patient/bladder-treatment-pdq. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- What is retrograde pyelography? Urology Care Foundation. https://www.urologyhealth.org/urologic-conditions/retrograde-pyelography. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- AskMayoExpert. Urinary diversion. Mayo Clinic; 2019.

- Warner KJ. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. Jan. 22, 2020.

- Bladder cancer FAQs

- Bladder cancer treatment options

- Glowing Cancer Surgery

- New immunotherapy approved for metastatic bladder cancer

- Robotic bladder surgery

- Scientists propose a breast cancer drug for some bladder cancer patients

Associated Procedures

- Bladder removal surgery (cystectomy)

- Chemotherapy

- Chest X-rays

- Computerized tomography (CT) urogram

- Neobladder reconstruction

- Radiation therapy

News from Mayo Clinic

- Bladder cancer: What you should know about diagnosis, treatment and recurrence June 22, 2023, 01:00 p.m. CDT

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, and Mayo Clinic in Phoenix/Scottsdale, Arizona, have been recognized among the top Cancer hospitals in the nation for 2023-2024 by U.S. News & World Report.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of wandering

(Entry 1 of 2)

Definition of wandering (Entry 2 of 2)

- digressional

- digressionary

Examples of wandering in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'wandering.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

before the 12th century, in the meaning defined above

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Phrases Containing wandering

wandering albatross

- wandering dude

- wandering eye

- wandering Jew

Dictionary Entries Near wandering

Cite this entry.

“Wandering.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/wandering. Accessed 29 Apr. 2024.

Medical Definition

Medical definition of wandering.

Medical Definition of wandering (Entry 2 of 2)

More from Merriam-Webster on wandering

Nglish: Translation of wandering for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of wandering for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 26, 9 superb owl words, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, fan favorites: your most liked words of the day 2023, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, games & quizzes.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The huge room with the tombstone-looking towers was inspired by a cemetery near the offices where the show is made. Rich thinks Futurama is the only primetime animated show that has effects animatiors working on staff. John thinks there is a quota to include the words "bastard" and "ass" in the show. The "wandering bladder" joke was pitched at ...

Paruresis, also known as shy bladder syndrome, is a type of phobia in which a person is unable to urinate in the real or imaginary presence of others, such as in a public restroom. The analogous condition that affects bowel movement is called parcopresis or shy bowel.

Symptoms. Gallstones may cause no signs or symptoms. If a gallstone lodges in a duct and causes a blockage, the resulting signs and symptoms may include: Sudden and rapidly intensifying pain in the upper right portion of your abdomen. Sudden and rapidly intensifying pain in the center of your abdomen, just below your breastbone.

Wandering Gallbladder . When the gallbladder has an unusually long mesentery, it can "wander" or "float." The gallbladder may "disappear" into the pelvis on upright radiographs or wander in front of the spine or to the left of the abdomen. Rarely, the gallbladder can herniate through the foramen of Winslow into the lesser sac.