- About data.world

- Terms & Privacy

- © 2024 data.world, inc

Visit our Research Matters blog for weekly posts from the homelessness sector here

Journey to work: Key results from the 2016 Census

- About Homelessness Back x About Homelessness Homelessness 101 What is homelessness? Causes of Homelessness Myths & Questions Preventing Homelessness Who is homeless? Housing First How many people are homeless in Canada? Ending Homelessness Cost Analysis Homelessness Glossary Topics Health Legal & Justice Issues Mental Health Priority Populations Substance Use & Addiction Service Provision Education, Training & Employment Teacher Resources Lesson Plans Examples of Student Work Teaching Children Who Are Homeless Units For Primary Units For Secondary Stories Families Women Youth Men Seniors Service Providers Gallery Arts Based Research Art In The News Audio Infographics Multimedia Music Performing Arts Photography Videos Visual Art Written Word Poverty Hub

- Doing Research Back x Doing Research Ethics Methodology Knowledge Mobilization Program Evaluation Reports Research The Outcomes Star Tools Best, Promising & Emerging Practices Case Studies Framework Monitoring Progress Point-In-Time Counts

- Community Profiles Back x Community Profiles Alberta Calgary Edmonton Grande Prairie Lethbridge Medicine Hat Red Deer Wood Buffalo British Columbia Abbotsford Chilliwack Kamloops Kelowna Nanaimo Nelson Prince George Vancouver Victoria Manitoba Brandon Thompson Winnipeg New Brunswick Bathurst Fredericton Moncton Saint John Newfoundland and Labrador St. John's Northwest Territories Yellowknife Nova Scotia Halifax Sydney (Cape Breton) Nunavut Iqaluit Ontario Barrie Belleville Brantford Cochrane District Dufferin Durham Region Guelph-Wellington Halton Hamilton Kenora Kingston Lambton County London Nipissing/North Bay Ottawa Peel Region Peterborough Sault Sainte Marie St. Catharines/Niagara Sudbury Thunder Bay Toronto Waterloo Region Windsor York Region Prince Edward Island Charlottetown Summerside Quebec Drummondville Gatineau Montreal Quebec City Saguenay Sherbrooke Trois Rivieres Saskatchewan Prince Albert Regina Saskatoon Yukon Territory Whitehorse

- Solutions Back x Solutions Prevention Framework for Preventing homelessness Human Rights Approach Prevention Legislation Roadmap for Preventing Youth Homelessness Ending Homelessness Cost Effectiveness of Ending Homelessness Defining End to Homelessness Plans to End Homelessness National Strategies Plans to End Youth Homelessness Accommodations & Supports Emergency Response Education, Training & Employment Supports Affordable Housing Housing First Other Housing Options Systems Integration Continuum of Integrated Care Strategies Strategies to Strengthen Homeless Service Integration Why do this? Wrap-around Delivery and Other Team-based Models Engaging Clients Human Resources Providing Supports Self-Care Training Priority Populations Families with Children Hidden Homeless Indigenous Peoples LGBTQ2S Newcomers People with Disabilities Racialized Communities Rural Populations & Northern Communities Seniors Sex Workers Single Men Single Women Youth

The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness is the largest national research institute devoted to homelessness in Canada. The COH is the curator of the Homeless Hub.

- Homeless Hub

- Homelessness Learning Hub

- Hub Solutions

- Making the Shift

- Systems Planning Collective

- Toronto Centre of Excellence

Homelessness 101

- What is homelessness?

- Causes of Homelessness

- Myths & Questions

- Preventing Homelessness

- Who is homeless?

- Housing First

- How many people are homeless in Canada?

Ending Homelessness

- Cost Analysis

- Legal & Justice Issues

- Mental Health

Priority Populations

- Substance Use & Addiction

- Service Provision

- Education, Training & Employment

Teacher Resources

- Lesson Plans

- Examples of Student Work

- Teaching Children Who Are Homeless

- Units For Primary

- Units For Secondary

Poverty Hub

Methodology, knowledge mobilization, program evaluation.

- The Outcomes Star

Best, Promising & Emerging Practices

- Case Studies

Monitoring Progress

- Point-In-Time Counts

British Columbia

New brunswick, newfoundland and labrador, northwest territories, nova scotia, prince edward island, saskatchewan, yukon territory.

- Framework for Preventing homelessness

- Human Rights Approach

- Prevention Legislation

- Roadmap for Preventing Youth Homelessness

- Cost Effectiveness of Ending Homelessness

- Defining End to Homelessness

- Plans to End Homelessness

- National Strategies

- Plans to End Youth Homelessness

Accommodations & Supports

- Emergency Response

- Affordable Housing

- Other Housing Options

Systems Integration

- Continuum of Integrated Care Strategies

- Strategies to Strengthen Homeless Service Integration

- Why do this?

- Wrap-around Delivery and Other Team-based Models

Engaging Clients

- Human Resources

- Providing Supports

- Families with Children

- Hidden Homeless

- Indigenous Peoples

- People with Disabilities

- Racialized Communities

- Rural Populations & Northern Communities

- Sex Workers

- Single Women

Canadian Observatory on Homelessness

- Work with us

- COH Publications

More Canadians commuted to work in 2016 and a greater proportion took public transit than ever before. For most working Canadians, commuting is part of daily life. Since 1996, the number of commuters has risen by 3.7 million or 30.3% to 15.9 million in 2016. However, the way they get to work is changing. From 1996 to 2016, the number of commuters taking public transit grew by 59.5%, while those using a car increased by 28.3%. Canada's workforce is also increasingly living in urban areas. In 1996, 8.6 million or 70.5% of employed Canadians who commuted to work were living in a census metropolitan area (CMA). By 2016, this proportion had increased to 73.5% or 11.7 million.

How people get to work is sometimes a matter of choice; they enjoy the walk, or they like to drive. In many other cases, however, financial circumstances, distance to work, reasonable access to public transit infrastructure, or the need for work-life balance can make certain modes of transportation to work almost a necessity over others.

Commuting issues are important for municipal and urban planners as well as other policy makers, notably those in economic, health, environmental or social policy. There are personal economic costs for commuting (such as vehicle maintenance) and public economic costs (such as productivity, or infrastructure investments). Long commutes are associated with poor health outcomes. Environmentally, greater use of sustainable transportation means less pollution and road congestion. For social policy, long commutes can put a strain on family relationships.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to "About this site"

Language selection

- Search and menus

Journey to work, 2016 Census . : CS11-627/2017-38E-PDF

"Based on 2016 Census data, the following infographic looks at Canadians’ average commute time, how they get to work, as well as the average commute time for those living in Canada’s largest census metropolitan areas"--Provided by publisher.

Permanent link to this Catalogue record: publications.gc.ca/pub?id=9.846937&sl=0

- MARC XML format

- MARC HTML format

Request alternate formats

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Language selection

- Search and menus

Journey to Work Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2016

Surveys and statistical programs – Documentation: 98-500-X2016011

This guide focuses on the following topic: journey to work. This reference guide provides information that enables users to effectively use, apply and interpret data from the 2016 Census. This guide contains definitions and explanations of concepts, classifications, data quality and comparability to other sources. Additional information is included for specific variables to help general users better understand the concepts and questions used in the census.

Main Product: Census of Population Reference Guide

Related information

- Census of Population

- Surveys and statistical programs – Documentation: Commuting Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021

- Commuting to work characteristics

- Workplace type

How the Canadian population gets to work

In this post Meghan Winters, Academic Lead of the Transportation Modes Theme , and Kate Hosford, PhD Candidate at Simon Fraser University , provide a snapshot of the 2016 census journey to work mode share data stratified by gender, age, income, race, and geography.

February 22, 2022

National data on how people move around their cities is useful for researchers and practitioners to describe transportation patterns, understand who is using which travel modes, and identify longer-term trends in travel across populations. Unfortunately, unlike our neighbours down south and many other countries around the world, Canada does not have a national household travel survey.

Researchers have called for a national travel household travel survey, but until then, the journey to work mode share data from the Canadian census is the most comprehensive routinely collected travel data we have. Journey to work mode share data is just a single question. It tells us about the mode a commuter typically uses to get to work – that is, the one they use most days of the week.

Responses are limited to a single mode – drive, transit, walk, bicycle – that they use for the majority of the trip distance. This masks the fact that people may use multiple modes for commuting, such as driving or walking to connect to transit. This limitation was addressed in the most recent 2021 census through the addition of a new question that asked respondents to select all the modes they usually use to commute to work, in addition to identifying their main mode.

And finally, this national transportation data limits insights to only work trips – excluding trips made by those who aren’t in the workforce and trips made for other purposes. As of 2016, 40% of the Canadian population is in the workforce and commutes to work. This number is likely even lower now in the context of the pandemic where many workers lost their jobs and many others shifted to working from home.

While some people may have a multitude of transportation modes to choose from to get to work, others do not. Travel mode choice may be constrained by distances, the availability of transit services or cycling infrastructure, personal resources, division of household labour, or other factors.

Researchers and practitioners commonly disaggregate transportation data by demographic and geographic characteristics to understand who is using which modes, to identify structural inequities in transportation systems, and to measure progress towards goals to reduce inequities.

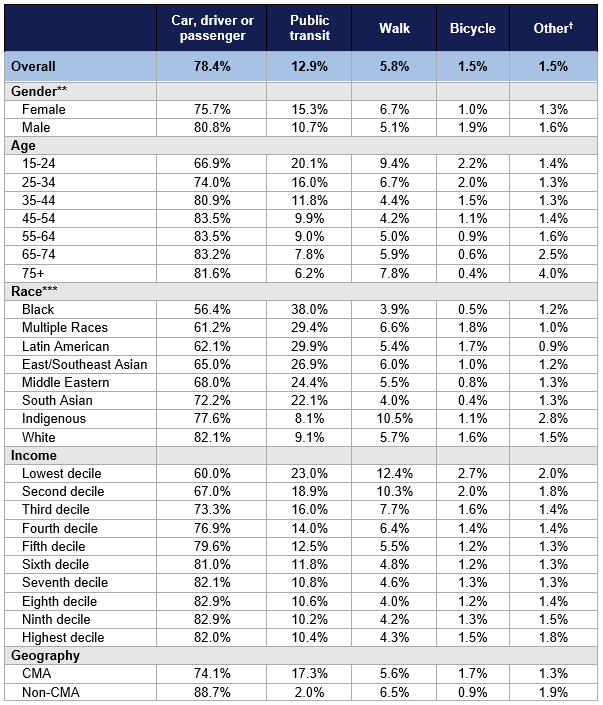

In this post we provide a snapshot of the national journey to work mode share data from the 2016 census, disaggregated by gender*, age, income, race**, and geography. We analyzed the data from the 2016 Census Public Use Microdata Files (PUMF), which is anonymized, non-aggregated census data provided by Statistics Canada. We include the data supporting each figure at the end of the blog.

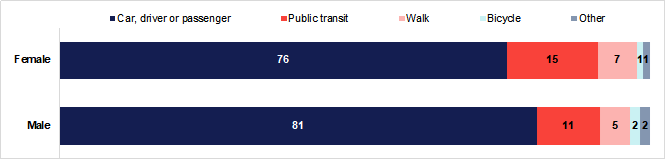

Journey to Work Mode Share by Gender

We see that compared to women, men are more likely to drive and cycle to work, and less likely to take public transit or walk.

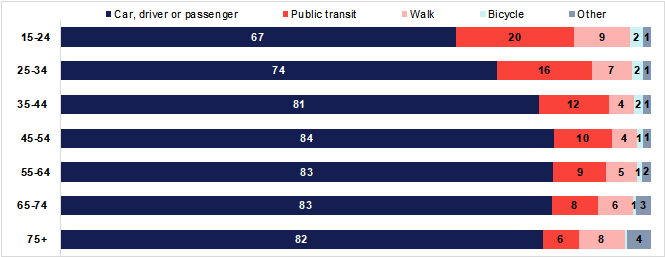

Journey to Work Mode Share by Age

We see that older workers are more likely to drive than younger workers, and less likely to take public transit, walk, or cycle. One third of commuters under 25 use sustainable transportation modes, while only about one-sixth of commuters do in the older age groups.

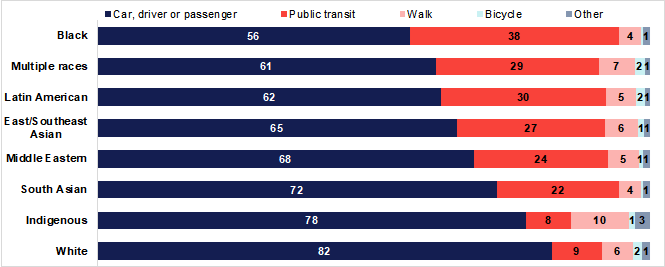

Journey to Work Mode Share by Race

Relative to all other groups, White commuters most commonly drive to work (82% of commuters). Public transit mode share is considerably lower for White and Indigenous populations (8-9% of commuters) compared to other populations. Black commuters stand out with a public transit mode share four times greater (38% use transit as their main mode).

Indigenous populations are the most likely to report walking to work as their usual mode, with a walk mode share of 10%. Those who identified as Mixed Race, Latin American, or White had the highest bicycle mode share (2%). Walking and cycling is less commonly reported by Black and South Asian commuters.

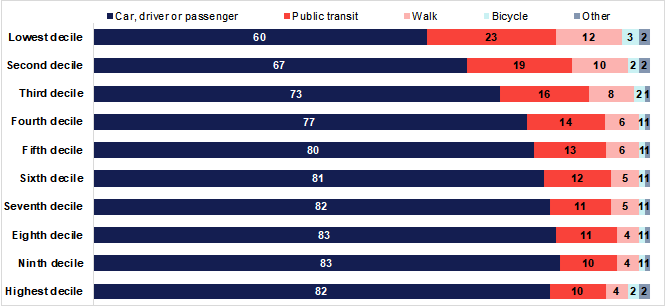

Journey to Work Mode Share by Income

There are clear patterns in journey to work mode share across income groups. The proportion who usually drive to work steadily increases with income: only 60% of commuters in the lowest income decile drive, while 82% of commuters in the highest income decile drive. Commuters with lower incomes more commonly rely on public transit, walking, and cycling.

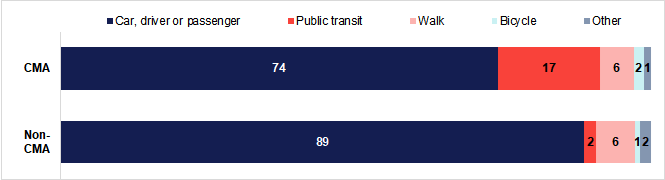

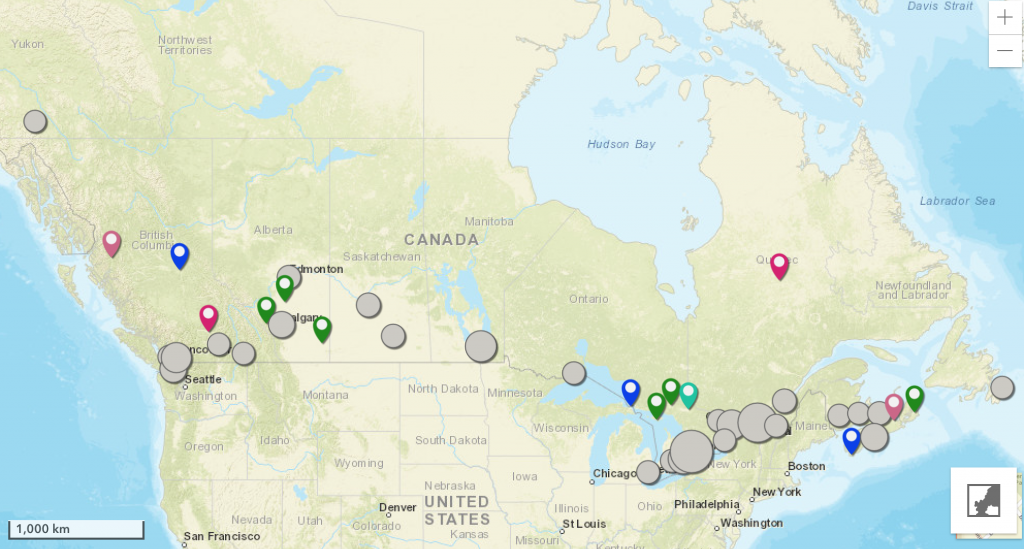

Journey to Work Mode Share by Geography

The availability of public transit and supportive walking and cycling environments varies widely across geographic contexts . About seven in ten (71%) of Canadians live within a Census Metropolitan Area , which are areas that consist of one or more neighbouring municipalities around an urban core – such as the Greater Vancouver region. As expected, driving to work is more common for those living outside a metropolitan area than for those living inside. Notably, the difference is essentially driven by a lack of public transit: only 2% of residents who live outside of a metropolitan area take public transit to work, compared to 17% within metropolitan areas.

Coming next: an intersectional approach

This first blog looked at transportation patterns by gender, age, race, income, and geography one by one. However, intersectional approaches underscore that these categories do not exist on their own, but rather intersect with each other to create distinct social experiences.

For example, a recent study in Montreal found that women were more likely to make household and caregiving trips as compared to men. However, when the researchers also considered income, they found that as household income increased, the division of care trips became more equal between men and women. This points to structural factors that create distinct experiences for women with lower incomes compared to women with higher incomes.

In our next post we will explore how journey to work mode share data varies across intersections of gender and age, race, income, and geography.

Journey to Work Mode Share Data, 2016 Canadian Census, overall and by gender*, age, race**, income, and geography.

† Other includes passenger ferry, motorcycle, scooter, moped, and other modes not listed in the census.

*The 2016 census collected data on “sex” which only included the binary response categories of Male and Female. The 2021 census was updated to include an additional question on gender, that included a non-binary response option.

**More information on race data collected in the Canadian census can be found here .

Note: For some records in the PUMF, responses were changed to ‘Not available’ to protect the identity of the respondent. Therefore, there are slight differences in the journey to work mode share results reported in this post, as compared to results published by Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada, 2019, “2016 Census Public Use Microdata File (PUMF). Individuals File”, https://hdl.handle.net/11272.1/AB2/GDJRT8, Abacus Data Network, V1

You may also like

Thomas van Laake, doctoral researcher at the University of Manchester Introduction In recent years, equity and justice have become central issues in bicycle planning and… Read More

by Thorben Wieditz, Director of Metstrat Digital platforms are reshaping how we work, live, and get around. The rise of the… Read More

Nancy Smith Lea is the Community Co-Lead of the Mobilizing Justice Transportation Modes Thematic Working Group and a Senior Advisor at The Centre for Active… Read More

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Almost 1 in 5 stay-at-home parents in the U.S. are dads

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to see how many mothers and fathers in the United States are not employed for pay and how stay-at-home parents are different from working parents. The analysis uses the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS), which is conducted in March of every year.

Administered jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the CPS is a monthly survey of approximately 70,000 households . It is the source of the nation’s official statistics on unemployment. The ASEC survey typically features an expanded sample of about 95,000 households.

Parents are people ages 18 to 69 who live with at least one of their own children (biological, step or adopted) younger than 18. Stay-at-home parents are those who were not employed for pay at all in the calendar year prior to the survey.

The population of stay-at-home fathers who are caring for home or family is relatively small, so we combined the 2020, 2021 and 2022 ASEC files to analyze their characteristics.

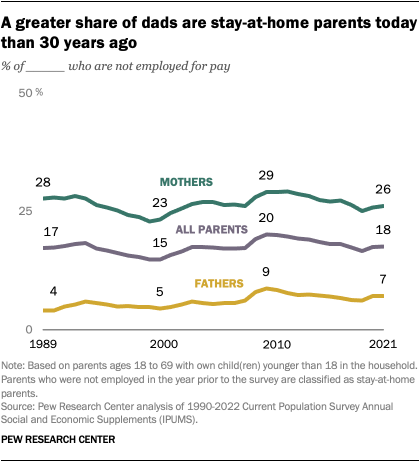

The share of parents in the United States who are not employed for pay has been fairly stable over the last five years. In 2021, 18% of parents didn’t work for pay, which was unchanged from 2016, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. The share who are stay-at-home parents differs between men and women: 26% of mothers and 7% of fathers.

Over the past 30 years, the share of stay-at-home parents has fluctuated, rising during periods of higher unemployment.

How stay-at-home dads and moms compare

Between 1989 and 2021, the share of mothers who were not employed for pay decreased slightly, from 28% to 26%. Over the same span, the share of fathers who were not working increased from 4% to 7%.

Due to these diverging trends, dads now represent 18% of stay-at-home parents, up from 11% in 1989.

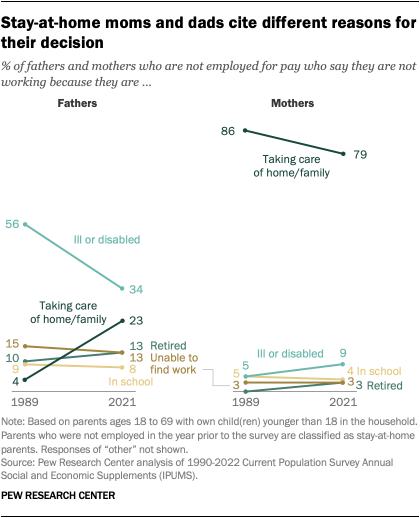

The reasons mothers and fathers give for not working for pay differ significantly. In 2021, the vast majority of stay-at-home moms (79%) said they took care of the home or family. About one-in-ten (9%) said they were at home because they were ill or disabled, and smaller shares said they didn’t work because they were students, unable to find work or retired.

Stay-at-home dads cite more varied reasons for not working for pay. In 2021, 23% stayed home to care for the home or family. That is up from only 4% in 1989 but still well below the share of stay-at-home moms who said the same.

About one-third of stay-at-home dads (34%) were not working due to illness or disability, down from 56% in 1989. Some 13% were retired, 13% said they could not find work and 8% were going to school.

How stay-at-home dads are different from dads who work

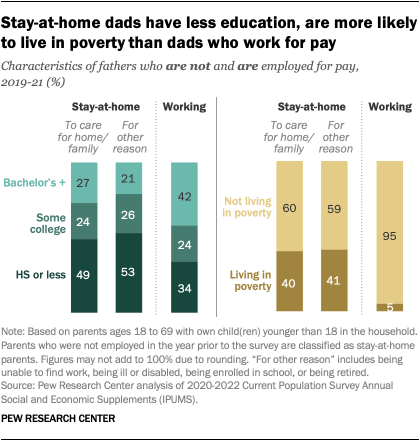

Stay-at-home dads differ demographically from dads who work for pay.

- Education: Stay-at-home dads are less likely than dads working for pay to have completed at least a bachelor’s degree. Some 22% of stay-at-home dads have this level of education, compared with 42% of dads who work for pay.

- Poverty: The families of stay-at-home dads tend to be less economically well-off than the families of dads who work for pay. Some 40% of stay-at-home dads live in poverty, compared with 5% of dads who work for pay.

- Age: Stay-at-home dads tend to be older than dads working for pay. Some 46% of stay-at-home dads are age 45 or older, compared with 35% of dads working for pay.

- Race and ethnicity: Stay-at-home dads are a more racially and ethnically diverse group than working dads. Half of dads who don’t work for pay are non-Hispanic White. This compares with 60% of dads working for pay. Non-Hispanic Black fathers are a larger share of stay-at-home dads (18%) than they are of working dads (9%). Hispanic fathers are 21% of both stay-at-home and working fathers, and non-Hispanic Asian fathers are 7% of stay-at-home fathers and 8% of working fathers.

- Marriage: Some 68% of stay-at-home dads are married, as are 85% of dads who work for pay.

In addition, stay-at-home dads who are taking care of the home or family differ in some ways from those who stay home for other reasons.

- Education: 27% of dads who stay home to care for family have a four-year college degree, while 21% of dads who stay home for other reasons do.

- Age: A third of dads staying home to take care of family are age 45 or older, compared with half of those who are home for other reasons.

- Marriage: 73%of dads who stay home to care for family are married, as are 66% of dads who are home for other reasons.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published Sept. 24, 2018, written by former Senior Researcher Gretchen Livingston.

- Family Caregiving

- Household Structure & Family Roles

- Motherhood & Fatherhood

Richard Fry is a senior researcher focusing on economics and education at Pew Research Center

Parents, Young Adult Children and the Transition to Adulthood

More than half of americans in their 40s are ‘sandwiched’ between an aging parent and their own children, financial issues top the list of reasons u.s. adults live in multigenerational homes, more than one-in-ten u.s. parents are also caring for an adult, adult caregiving often seen as very meaningful by those who do it, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Disclaimer: It looks like you're using an old version of Internet Explorer. For the best experience, please update your browser.

- Participating in a survey

- Creative commons

- Accessibility

- Staff login

- Skip to main content

- Skip to "About this site"

Language selection

- Français

- Search and menus

Data tables, 2016 Census

Journey to work.

16 result(s) found, grouped by product name

Group number 1 of 16 - Commuting Destination (5), Main Mode of Commuting (10), Sex (3) and Age (5) for the Employed Labour Force Aged 15 Years and Over Having a Usual Place of Work, in Private Households

Group number 2 of 16 - commuting flow from geography of residence to geography of work - census divisions: sex (3) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work, in private households, group number 3 of 16 - commuting flow from geography of residence to geography of work - census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations: main mode of commuting (10), commuting duration (6) and sex (3) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work, in private households, group number 4 of 16 - commuting flow from geography of residence to geography of work: - census subdivisions: sex (3) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work, in private households, group number 5 of 16 - language used most often at work (8), other language(s) used regularly at work (9), language spoken most often at home (8), immigrant status (4) and place of work census division (296) for the population aged 15 years and over who worked since 2015, in private households, group number 6 of 16 - main mode of commuting (10), commuting duration (6), distance from home to work (12) and time leaving for work (7) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work, in private households, group number 7 of 16 - main mode of commuting (10), commuting duration (6), time leaving for work (7), occupation - national occupational classification (noc) 2016 (11) and sex (3) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work or no fixed workplace address, in private households, group number 8 of 16 - main mode of commuting (10), commuting duration (7), time leaving for work (7), sex (3) and age (5) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work or no fixed workplace address, in private households, group number 9 of 16 - main mode of commuting (10), employment income groups (18), sex (3) and age (5) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work or no fixed workplace address, in private households, group number 10 of 16 - main mode of commuting (10), highest certificate, diploma or degree (7), sex (3) and age (5) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work or no fixed workplace address, in private households, group number 11 of 16 - main mode of commuting (10), immigrant status and period of immigration (9), sex (3) and age (5) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work or no fixed workplace address, in private households, group number 12 of 16 - main mode of commuting (10), industry - north american industry classification system (naics) 2012 (21), occupation - national occupational classification (noc) 2016 (11) and sex (3) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work or no fixed workplace address, in private households, group number 13 of 16 - main mode of commuting (20), commuting duration (6), distance from home to work (12), time leaving for work (7), sex (3) and age (5) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work, in private households, group number 14 of 16 - main mode of commuting (20), commuting duration (7), time leaving for work (7), sex (3) and age (11b) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over having a usual place of work or no fixed workplace address, in private households, group number 15 of 16 - place of work status (5), industry - north american industry classification system (naics) 2012 (122), sex (3) and age (11b) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over in private households, group number 16 of 16 - place of work status (5), industry - north american industry classification system (naics) 2012 (21), occupation - national occupational classification (noc) 2016 (11) and sex (3) for the employed labour force aged 15 years and over, in private households.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Access demographic, economic and population data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Explore census data with visualizations and view tutorials. ... (Journey to Work) Commuting data includes where people work (including work from home), when their trip starts, how they get there, and how long it takes. ... 2016 American Community Survey Content Test ...

Brian McKenzie. Download 2016 American Community Survey Content Test Evaluation Report: Journey to Work - Travel Mode of Commute and Time of Departure for Work [PDF - <1.0 MB] From February to June of 2016, the U.S. Census Bureau conducted the 2016 American Community Survey (ACS) Content Test, a field test of new and revised content.

We ask questions about where people work, how they get there, when they leave, and how long it takes, to create statistics about commuting, or a person's journey to work. This information is for planning improvements to roads and highways and planning emergency response routes. The 1960 Census was the first to ask about how people get to work ...

2016 Census topic: Journey to work. Release date: November 29, 2017 Updated on: December 2, 2019. The 2016 Census of Population Program offers a wide range of analysis, data, reference and geographical information according to topics (subjects) that paint a portrait of Canada and its population.

The journey to work is captured by an individual's location of usual residence, their location of workplace along with the method by which they commuted. For the first time, 2016 Census data has been released with the distance travelled to work, enabling further analysis on this topic to be performed. See Commuting Distance for Australia for ...

Commuting patterns and characteristics are crucial to planning for improvements to road and highway infrastructure, developing transportation plans and services, and understanding where people are traveling in the course of a normal day. The 1960 Census was the first to ask about how people get to work. In 1970, the Census added a question ...

2019-01-03. This guide focuses on the following topic: journey to work. This reference guide provides information that enables users to effectively use, apply and interpret data from the 2016 Census. This guide contains definitions and explanations of concepts, classifications, data quality and comparability to other sources.

data.world ACS Summary File datasets are already split across Topic Areas. This dataset focuses on the Journey to Work topic area. If you are looking for another topic area, go back to data.world/uscensusbureau to find the one you are looking for. Federated queries across multiple Topic Areas are possible with the data.world query tool.

This is a summary from publication Journey to Work to Place of Work which contains key figures, ... Census of Population and Housing: Commuting to Work - More Stories from the Census, 2016 . ARCHIVED ISSUE Released at 11:30 AM (CANBERRA TIME) 22/05/2018 First Issue. Summary;

However, the way they get to work is changing. From 1996 to 2016, the number of commuters taking public transit grew by 59.5%, while those using a car increased by 28.3%. Canada's workforce is also increasingly living in urban areas. In 1996, 8.6 million or 70.5% of employed Canadians who commuted to work were living in a census metropolitan ...

For most working Canadians, commuting is part of daily life. Since 1996, the number of commuters has risen by 3.7 million or 30.3% to 15.9 million in 2016. But how they get to work is changing. From 1996 to 2016, the number of commuters taking public transit grew by 59.5%, while those using a car increased by 28.3%.

The origin-destination flow format informs our understanding of interconnectedness between communities, including the interchange of people, goods, and services. Commuting flows also help shape the contours of metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas. Commuting flow estimates are not included among standard annual ACS products, but they ...

Publication information / bibliographic Record. Journey to work, 2016 Census .: CS11-627/2017-38E-PDF "Based on 2016 Census data, the following infographic looks at Canadians' average commute time, how they get to work, as well as the average commute time for those living in Canada's largest census metropolitan areas"--Provided by publisher.

The average commute to work in 2016 took 26 minutes.. 7% of Canadians usually worked at home in 2016. How residents of Canada's CMAs Footnote 2 are commuting. In 2016, 22% of commuters living in the Montréal CMA commuted by public transit and took an average of 44 minutes to get to work.. Car commuters living in the Montréal CMA took an average of 27 minutes to get to work.

This guide focuses on the following topic: journey to work. This reference guide provides information that enables users to effectively use, apply and interpret data from the 2016 Census. This guide contains definitions and explanations of concepts, classifications, data quality and comparability to other sources. Additional information is included for specific variables to

Journey to Work Mode Share Data, 2016 Canadian Census, overall and by gender*, age, race**, income, and geography. † Other includes passenger ferry, motorcycle, scooter, moped, and other modes not listed in the census. *The 2016 census collected data on "sex" which only included the binary response categories of Male and Female.

Census of Population Reference Guide. Journey to Work Reference Guide. Census of Population, 2016. Release date: November 29, 2017. How to obtain more information. For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca.

While 'Bicycle' has always been a response option for the journey to work question, 'Walking' was only added as its own response option on the 1986 Census, meaning responses from 1976 and 1981 were written in. Active modes of transport peaked over the 2011 and 2016 Census cycles each recording close to 480,000 commuters.

Email: [email protected]. Date modified: 2019-01-03. The Journey to work Release and concepts overview provides an overview of the concepts, definitions and key measures used in the 2016 Census of Population Journey to work release, as well as the products which will be available on release day and later.

The share of parents in the United States who are not employed for pay has been fairly stable over the last five years. In 2021, 18% of parents didn't work for pay, which was unchanged from 2016, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

This is a summary from publication Interactive Maps - Journey to Work which contains key figures, key points and notes from the publication. 2071..55.001 - Census of Population and Housing: Commuting to Work - More Stories from the Census, 2016

Journey to work index Dictionary, Census of Population, 2016 Journey to work index. Release date: May 3, 2017. Tables Figures Appendices More information. Filter by: ...

Data tables, 2016 Census. Journey to work 16 result(s) found, grouped by product name . Ungroup related products. ... Commuting Flow from Geography of Residence to Geography of Work - Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations: Main Mode of Commuting (10), Commuting Duration (6) and Sex (3) for the Employed Labour Force Aged 15 Years ...