- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Tracheostomy

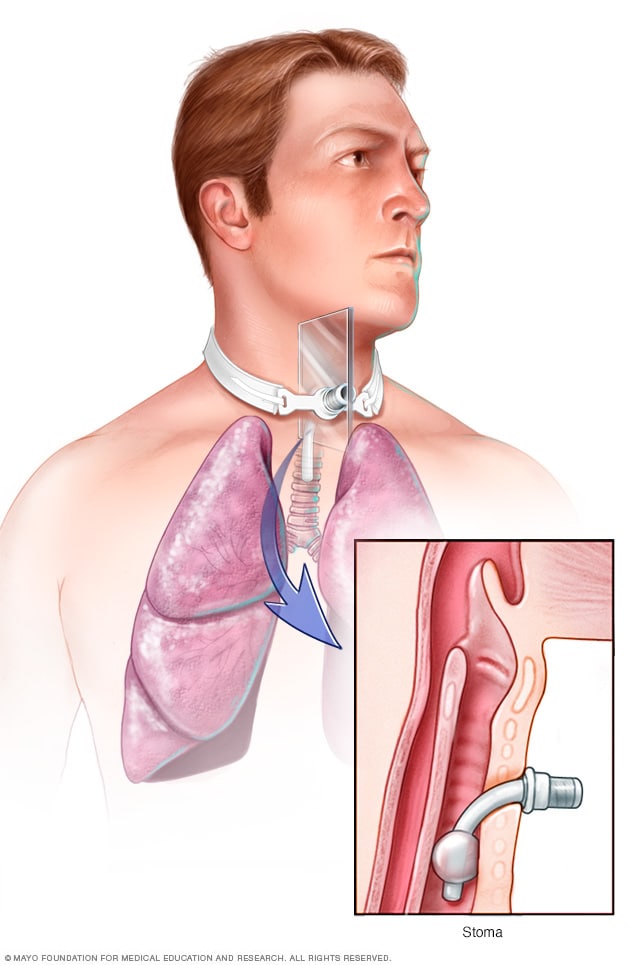

A tracheostomy is a surgically created hole (stoma) in your windpipe (trachea) that provides an alternative airway for breathing. A tracheostomy tube is inserted through the hole and secured in place with a strap around your neck.

Tracheostomy (tray-key-OS-tuh-me) is a hole that surgeons make through the front of the neck and into the windpipe (trachea). A tracheostomy tube is placed into the hole to keep it open for breathing. The term for the surgical procedure to create this opening is tracheotomy.

A tracheostomy provides an air passage to help you breathe when the usual route for breathing is somehow blocked or reduced. A tracheostomy is often needed when health problems require long-term use of a machine (ventilator) to help you breathe. In rare cases, an emergency tracheotomy is performed when the airway is suddenly blocked, such as after a traumatic injury to the face or neck.

When a tracheostomy is no longer needed, it's allowed to heal shut or is surgically closed. For some people, a tracheostomy is permanent.

Mayo Clinic's approach

Products & Services

- Sign up for Email: Get Your Free Resource – Coping with Cancer

Why it's done

Situations that may call for a tracheostomy include:

- Medical conditions that make it necessary to use a breathing machine (ventilator) for an extended period, usually more than one or two weeks

- Medical conditions that block or narrow your airway, such as vocal cord paralysis or throat cancer

- Paralysis, neurological problems or other conditions that make it difficult to cough up secretions from your throat and require direct suctioning of the windpipe (trachea) to clear your airway

- Preparation for major head or neck surgery to assist breathing during recovery

- Severe trauma to the head or neck that obstructs breathing

- Other emergency situations when breathing is obstructed and emergency personnel can't put a breathing tube through your mouth and into your trachea

Emergency care

Most tracheotomies are performed in a hospital setting. However, in the case of an emergency, it may be necessary to create a hole in a person's throat when outside of a hospital, such as at the scene of an accident.

Emergency tracheotomies are difficult to perform and have an increased risk of complications. A related and somewhat less risky procedure used in emergency care is a cricothyrotomy (kry-koe-thie-ROT-uh-me). This procedure creates a hole directly into the voice box (larynx) at a site immediately below the Adam's apple (thyroid cartilage).

Once a person is transferred to a hospital and stabilized, a cricothyrotomy is replaced by a tracheostomy if there's a need for long-term breathing assistance.

Tracheostomies are generally safe, but they do have risks. Some complications are particularly likely during or shortly after surgery. The risk of such problems greatly increases when the tracheotomy is performed as an emergency procedure.

Immediate complications include:

- Damage to the trachea, thyroid gland or nerves in the neck

- Misplacement or displacement of the tracheostomy tube

- Air trapped in tissue under the skin of the neck (subcutaneous emphysema), which can cause breathing problems and damage to the trachea or food pipe (esophagus)

- Buildup of air between the chest wall and lungs (pneumothorax), which causes pain, breathing problems or lung collapse

- A collection of blood (hematoma), which may form in the neck and compress the trachea, causing breathing problems

Long-term complications are more likely the longer a tracheostomy is in place. These problems include:

- Obstruction of the tracheostomy tube

- Displacement of the tracheostomy tube from the trachea

- Damage, scarring or narrowing of the trachea

- Development of an abnormal passage between the trachea and the esophagus (tracheoesophageal fistula), which can increase the risk of fluids or food entering the lungs

- Development of a passage between the trachea and the large artery that supplies blood to the right arm and right side of the head and neck (tracheoinnominate fistula), which can result in life-threatening bleeding

- Infection around the tracheostomy or infection in the trachea and bronchial tubes (tracheobronchitis) and lungs (pneumonia)

If you still need a tracheostomy after you've left the hospital, you'll need to keep regularly scheduled appointments for monitoring possible complications. You'll also receive instructions about when you should call your doctor about problems, such as:

- Bleeding at the tracheostomy site or from the trachea

- Difficulty breathing through the tube

- Pain or a change in comfort level

- Redness or swelling around the tracheostomy

- A change in the position of your tracheostomy tube

How you prepare

How you prepare for a tracheostomy depends on the type of procedure you'll undergo. If you'll be receiving general anesthesia, your doctor may ask that you avoid eating and drinking for several hours before your procedure. You may also be asked to stop certain medications.

Plan for your hospital stay

After the tracheostomy procedure, you'll likely stay in the hospital for several days as your body heals. If possible, plan ahead for your hospital stay by bringing:

- Comfortable clothing, such as pajamas, a robe and slippers

- Personal care items, such as your toothbrush and shaving supplies

- Entertainment to help you pass the time, such as books, magazines or games

- A communication method, such as a pencil and a pad of paper, a smartphone, or a computer, as you'll be unable to talk at first

What you can expect

During the procedure.

A tracheotomy is most commonly performed in an operating room with general anesthesia, which makes you unaware of the surgical procedure. A local anesthetic to numb the neck and throat is used if the surgeon is worried about the airway being compromised from general anesthesia or if the procedure is being done in a hospital room rather than an operating room.

The type of procedure you undergo depends on why you need a tracheostomy and whether the procedure was planned. There are essentially two options:

- Surgical tracheotomy can be performed in an operating room or in a hospital room. The surgeon usually makes a horizontal incision through the skin at the lower part of the front of your neck. The surrounding muscles are carefully pulled back and a small portion of the thyroid gland is cut, exposing the windpipe (trachea). At a specific spot on your windpipe near the base of your neck, the surgeon creates a tracheostomy hole.

- Minimally invasive tracheotomy (percutaneous tracheotomy) is typically performed in a hospital room. The doctor makes a small incision near the base of the front of the neck. A special lens is fed through the mouth so that the surgeon can view the inside of the throat. Using this view of the throat, the surgeon guides a needle into the windpipe to create the tracheostomy hole, then expands it to the appropriate size for the tube.

For both procedures, the surgeon inserts a tracheostomy tube into the hole. A neck strap attached to the face plate of the tube keeps it from slipping out of the hole, and temporary sutures can be used to secure the faceplate to the skin of your neck.

After the procedure

You'll likely spend several days in the hospital as your body heals. During that time, you'll learn skills necessary for maintaining and coping with your tracheostomy:

- Caring for your tracheostomy tube. A nurse will teach you how to clean and change your tracheostomy tube to help prevent infection and reduce the risk of complications. You'll continue to do this as long as you have a tracheostomy.

- Speaking. Generally, a tracheostomy prevents speaking because exhaled air goes out the tracheostomy opening rather than up through your voice box. But there are devices and techniques for redirecting airflow enough to produce speech. Depending on the type of tube, width of your trachea and condition of your voice box, you may be able to speak with the tube in place. If necessary, a speech therapist or a nurse trained in tracheostomy care can suggest options for communicating and help you learn to use your voice again.

- Eating. While you're healing, swallowing will be difficult. You'll receive nutrients through an intravenous (IV) line inserted into a vein in your body, a feeding tube that passes through your mouth or nose, or a tube inserted directly into your stomach. When you're ready to eat again, you may need to work with a speech therapist, who can help you regain the muscle strength and coordination needed for swallowing.

- Coping with dry air. The air you breathe will be much drier because it no longer passes through your moist nose and throat before reaching your lungs. This can cause irritation, coughing and excess mucus coming out of the tracheostomy. Putting small amounts of saline directly into the tracheostomy tube, as directed, may help loosen secretions. Or a saline nebulizer treatment may help. A device called a heat and moisture exchanger captures moisture from the air you exhale and humidifies the air you inhale. A humidifier or vaporizer adds moisture to the air in a room.

- Managing other effects. Your health care team will show you ways to care for other common effects related to having a tracheostomy. For example, you may learn to use a suction machine to help you clear secretions from your throat or airway.

In most cases, a tracheostomy is temporary, providing an alternative breathing route until other medical issues are resolved. If you need to remain connected to a ventilator indefinitely, the tracheostomy is often the best permanent solution.

Your health care team will help you determine when it's appropriate to remove the tracheostomy tube. The hole may close and heal on its own, or it can be closed surgically.

Tracheostomy care at Mayo Clinic

- Brown AY. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. Aug. 28, 2019.

- Tracheostomy. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/tracheostomy. Accessed Sept. 23, 2019.

- Tracheostomy and ventilator dependence. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/tracheostomies/. Accessed Sept. 19, 2019.

- Surgical airway. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/critical-care-medicine/respiratory-arrest/surgical-airway#. Accessed Sept. 23, 2019.

- Roberts JR, et al., eds. Tracheostomy care. In: Roberts and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2019. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Sept. 23, 2019.

- Patton J. Tracheostomy care. British Journal of Nursing. 2019; doi:10.12968/bjon.2019.28.16.1060.

- Mitchell RB, et al. Clinical consensus statement: Tracheostomy care. Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery. 2013; doi:10.1177/0194599812460376.

- Landsberg JW. Pulmonary and critical care pearls. In: Clinical Practice Manual for Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. Elsevier; 2018. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Sept. 25, 2019.

- Rashid AO, et al. Percutaneous tracheostomy: A comprehensive review. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2017; doi:10.21037/jtd.2017.09.33.

- Moore EJ (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Oct. 1, 2019.

- Epiglottitis

- Mouth cancer

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Sleep apnea

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and Mayo Clinic in Phoenix/Scottsdale, Arizona, are ranked among the Best Hospitals for ear, nose and throat by U.S. News & World Report.

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Intensive Care Hotline

is instantly improving the lives for Families of critically ill Patients in Intensive Care, so that they can make informed decisions, have PEACE OF MIND, control, power and influence and therefore stay in control of their Family's and their critically ill loved one's destiny

- US: +1 415 915 0090

- AUS: +61 3 8658 2138

- UK: +44 118 324 3018

- patrik.hutzel

24/7 Phone Access

Your intensive care hotline - quick tip for families in icu: does a peg need to be done at the same time with a tracheostomy.

Free Download INSTANT IMPACT REPORT

We hate spam too. Your privacy will be protected.

November 26, 2020 / Patrik Hutzel - Critical Care Nurse Consultant / No Comments

Quick Tip for Families in ICU: Does a PEG Need To Be Done at the Same Time With a Tracheostomy?

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hi, it’s Patrik Hutzel from intensivecarehotline.com with another quick tip for families in intensive care.

So today’s tip is about, should a tracheostomy and a PEG be done at the same time. So a lot of patients in intensive care that need a tracheostomy or a trache also often have a PEG tube at the same time. A PEG tube is a feeding tube that’s basically inserted in the stomach through the abdominal wall.

Now, from my experience, a PEG and a tracheostomy do not have to be done at the same time. Although I know from experience that hospitals and ICUs are often trying to push families in intensive care to agree to do a PEG and a tracheostomy at the same time.

Now I tell you my point of view, from my experience now, number one, they don’t have to be done at the same time. I even oppose doing them at the same time, and I’ll tell you why.

So when someone is ventilated with a breathing tube or with a tracheostomy, they can’t eat and they need to be fed and they need to have nutrition. Now, when someone is first being put on a ventilator and intubated patients often have an orogastric tube or a nasogastric tube , that’s basically inserted through the nose or through the mouth and it’s going into the stomach and enteral feeding can be commenced through that tube.

When someone is having a tracheostomy, they still need to continue to be fed because they’re still not in a position to take oral food or oral supplements.

Now, when someone is on a tracheostomy and ventilated, they can continue to receive nutrition through a nasogastric tube or through an orogastric tube. However, a nasogastric tube is definitely preferred. An orogastric tube can be easily dislocated and a nasogastric tube is a more stable feeding tube.

Now, why am I opposed to doing a PEG simultaneously with a tracheostomy? The reason I’m opposed to it is, a PEG is a permanent or it’s often used as a permanent feeding tube. Now the goal for someone with a tracheostomy and the ventilator should be to wean them off the tracheostomy and the ventilation. That should be the goal, always.

If you’re having a PEG tube, it makes people complacent. It stops people from even trying to have oral intake. It stops people from weaning people off the ventilator and the tracheostomy.

A PEG is often a permanent arrangement, whereas a nasogastric tube, it’s in the nose. It’s probably uncomfortable. Don’t get me wrong. You might have to change it here and there to not get pressure sores in the nose, but there’s a real incentive to wean patients off the ventilator and tracheostomy if you’re not having a PEG, because you know, you need to get people back on their feet.

You need to get people to start to eat and drink again. A PEG is a permanent arrangement. Anybody that lives with ventilation and tracheostomy long-term over years, yes, they need to have a PEG. There is no doubt about that.

But if you’re starting with a PEG, the minute you, inserting a tracheostomy, I do strongly believe that it makes people complacent and not trying hard enough to get people off the ventilator and tracheostomy with a PEG.

That is my quick tip for today. Like this video, comment down below your thoughts and what questions you want to have answered and subscribe to my YouTube channel for any updates for families in intensive care.

This is Patrik Hutzel from intensivecarehotline.com and I’ll talk to you in a few days.

Related Articles:

- Your Loved Ones Condition

- Your Loved Ones Treatment

- Equipment Used in Intensive Care

- YouTube Live

- Your Questions Answered

- Testimonials

- Email Counselling

Get YOUR FREE Video Mini-Course " A BLUEPRINT for PEACE OF MIND, CONTROL, POWER & INFLUENCE whilst YOUR loved one is CRITICALLY ILL in Intensive Care!"

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What You Need to Know About PEG Tubes

Who may benefit, how to prepare, how a peg tube is placed, after placement, living with a peg tube, complications, frequently asked questions.

A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is a procedure in which a flexible feeding tube, called a PEG tube, is inserted through the abdominal wall and into the stomach. For patients who are not able to swallow food on their own, a PEG tube allows nutrition, fluids, and medications to be delivered directly into the stomach, eliminating the need to swallow by bypassing the mouth and esophagus.

Feeding tubes are helpful for people who are unable to feed themselves as a result of an acute illness or surgery, but who otherwise have a reasonable chance to recover. They are also helpful for people who are temporarily or permanently unable to swallow but who otherwise have normal or near-normal physical function.

In such instances, feeding tubes may serve as the only way to provide much-needed nutrients and/or medications. This is known as enteral nutrition.

Some common reasons why a person would need a feeding tube include:

- Trouble swallowing due to weakness or paralysis from a brain injury or a stroke

- Cancer involving the head or neck muscles, which interferes with swallowing

- Being unable to purposefully control muscles due to a coma or a serious neurological condition

- Chronic loss of appetite due to severe illness such as cancer

Advantages of a PEG tube for these patients include:

- Improved energy as a result of getting proper nutrition

- Ability to maintain a healthy weight due to getting an adequate number of calories

- Specialized nutrition for a patient's specific needs

- A stronger immune system resulting from improved overall health

Before you undergo a gastrostomy, your healthcare provider will need to know if you have any chronic health conditions (such as high blood pressure) or allergies and which medications you take. You may need to stop certain medications, such as blood thinners or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) until after the procedure to minimize the risk of bleeding.

You will not be able to eat or drink for eight hours prior to the surgery and should arrange for someone to pick you up and drive you home.

Other Types of Feeding Tubes

There are three other types of feeding tubes in addition to the PEG tube. These include:

- Nasogastric tube (NG tube) : This is among the least invasive types of feeding tubes and is only used temporarily. NG tubes are thin and are inserted into a nostril, then threaded through the esophagus and into the stomach. The outer portion is generally kept in position with tape that is placed on the nose. NG tubes can become clogged, requiring replacement with a new tube every few days, but they are easy to remove. Long-term use of NG tubes has been associated with sinusitis and other infections.

- Orogastric (OG) tube : An orogastric tube is like a nasogastric tube, except that it is inserted into the mouth instead of the nostril. This tube can remain in place for up to two weeks, when it must be removed or replaced with a permanent tube.

- Jejunostomy tube (J tube or PEJ tube): A jejunostomy tube is similar to a PEG tube, but its tip lies inside the small intestine, thus bypassing the stomach. It is mainly used for people whose stomach cannot effectively move food down into the intestine due to weakened motility.

If a person cannot eat and a feeding tube is not an option, then fluids, calories, and nutrients needed to survive are provided intravenously. Generally, getting calories and nutrients into the stomach or into the intestine is the best way for people to get the nutrients needed for the body to function optimally, and therefore a feeding tube provides better nutrition than what can be provided through IV fluids.

Prior to the PEG placement procedure, you will be given an intravenous sedative and local anesthesia around the incision site. You may also receive an IV antibiotic to prevent infection.

The healthcare provider will then put a lighted, flexible tube called an endoscope down your throat to help guide the actual tube placement through the wall of the stomach. A small incision is made, and a disc is placed on the inside as well as the outside of the opening in your abdomen; this opening is known as a stoma . The part of the tube that is outside the body is 6 to 12 inches long.

The entire procedure takes about 20 to 30 minutes. You are usually able to go home the same day.

Once the procedure is finished, your surgeon will place a bandage over the incision site. You will probably have some pain around the incision area right after the procedure, or have cramps and discomfort from gas. There may also be some fluid leakage around the incision site. These side effects should decrease within 24 to 48 hours. Typically, you can remove the bandage after a day or two.

Your healthcare provider will tell you when it is OK to shower or bathe.

It takes time to adjust to a feeding tube. If you need the tube because you are not able to swallow, you will not be able to eat and drink through your mouth. (Rarely, people with PEG tubes can still eat via the mouth.) Products designed for tube feeding are formulated to provide all the nutrients you'll need.

When you're not using it, you can tape the tube to your belly using medical tape. The plug or cap on the end of the tube will prevent any formula from leaking onto your clothes.

How to Receive Nutrition

After the area around your feeding tube heals, you'll meet with a nutritionist or dietitian who will show you how to use the PEG tube and start you on enteral nutrition. Here are the steps you will follow when using your PEG tube:

- Wash your hands before you handle the tube and formula.

- Sit up straight.

- Open the cap on the end of the tube.

- If you are using a feeding syringe, connect it to the tube and fill the syringe with the formula (which should be at room temperature).

- Hold the syringe up high so the formula flows into the tube. Use the plunger on the syringe to gently push any remaining formula into the tube.

- If you are using a gravity bag, connect the bag to the tube, and add the formula to the bag. Hang the bag on a hook or pole about 18 inches above the stomach. Depending on the type of formula, the food may take a few hours to flow through the tube with this method.

- Sit up during the feeding and for 60 minutes afterward.

Having a PEG tube comes with the risk of certain complications. These include:

- Pain around the insertion site

- Leakage of stomach contents around the tube site

- Malfunction or dislodgment of the tube

- Infection of the tube site

- Aspiration (inhalation of gastric contents into the lungs)

- Bleeding and perforation of the bowel wall

Difficult Decisions

In some instances, it can be hard to decide whether giving a person a feeding tube is the right thing to do and what the ethical considerations are. Examples of these situations include:

- When a person is in a coma due to a progressive and fatal disease (such as metastatic cancer) that is expected to cause death very soon. Some family members may feel that a feeding tube can prolong life for only a few days and may also lead to excessive pain and discomfort for the dying and unresponsive loved one.

- When a person is unable to express personal wishes due to the impact of disease but had previously stated to loved ones that they would not want to be fed through a feeding tube. This can be a difficult problem when some, but not all, family members are aware of their loved one's wishes, but the wishes are not written or documented anywhere.

- When a person is in a coma, with extensive and irreversible brain damage and no meaningful chance to recover, but could be kept alive indefinitely with artificial feedings.

- When a person has signed a living will that specifies they would never want to be fed through a feeding tube, but the medical team and family have reason to believe that there is a chance of recovery if nutritional support is provided.

If you or your loved one has a serious illness that prevents eating by mouth, a PEG tube can temporarily, or even permanently, provide calories and nutrients for the body to heal and thrive.

PEG tubes can last for months or years. If necessary, your healthcare provider can easily remove or replace a tube without sedatives or anesthesia, by using firm traction. Once the tube is removed, the opening in your abdomen closes quickly (hence if it falls out accidentally, you should call your healthcare provider immediately.)

Whether tube feeding improves quality of life (QoL) depends on the reason for the tube and the condition of the patient. A 2016 study looked at 100 patients who had received a feeding tube. Three months later, the patients and/or caregivers were interviewed. The authors concluded that while the tubes didn't improve QoL for patients, their QoL didn't decrease.

How do you check PEG tube placement?

The tube will have a mark that shows where it should be level with the opening in your abdominal wall. This can help you confirm that the tube is in the correct position.

How do you clean a PEG tube?

You clean a PEG tube by flushing warm water through the tube with a syringe before and after feeding or receiving medications and cleaning the end with an antiseptic wipe.

How do you unclog a PEG tube?

First, try to flush the tube as you normally do before and after feedings. A blockage can occur if the tube isn't flushed or if the feeding formula is too thick. If the tube won't clear, call your healthcare provider. Never use a wire or anything else to try to unclog the tube.

How do you stop a PEG tube from leaking?

A leaking tube may be blocked. Try flushing it. If that doesn't work, call your healthcare provider.

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Understanding percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) .

Ojo O, Keaveney E, Wang XH, Feng P. The effect of enteral tube feeding on patients' health-related quality of life: A systematic review . Nutrients . 2019;11(5). doi:10.3390/nu11051046

Cleveland Clinic. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG tube) .

Metheny NA, Hinyard LJ, Mohammed KA. Incidence of sinusitis associated with endotracheal and nasogastric tubes: NIS database . Am J Crit Care . 2018;27(1):24-31. doi:10.4037/ajcc2018978

Yoon EWT, Yoneda K, Nakamura S, Nishihara K. Percutaneous endoscopic transgastric jejunostomy (PEG-J): a retrospective analysis on its utility in maintaining enteral nutrition after unsuccessful gastric feeding . BMJ Open Gastroenterol . 2016;3(1):e000098corr1. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000098

U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus. PEG tube insertion - discharge .

The Oral Cancer Foundation. PEG feeding overview .

Michigan Medicine: Living with a feeding tube .

- Miles A, Watt T, Wong WY, McHutchison L Friary P. Complex feeding decisions: Perceptions of staff, patients, and their families in the inpatient hospital setting . Gerontol Geriatr Med . Aug 22, 2016. doi:10.1177/2333721416665523

Kurien M, Andrews RE, Tattersall R, et al. Gastrostomies preserve but do not increase quality of life for patients and caregivers . Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology . 2017 Jul;15(7):1047-1054. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.032

By Jose Vega MD, PhD Jose Vega MD, PhD, is a board-certified neurologist and published researcher specializing in stroke.

Flats happen

We'll show you how to fix them.

- filter controls Items 24 24 48 72 filter controls Sort by Featured Featured A-Z Z-A Price Low-High Price High-Low

Everything that You Always Wanted to Know About the Management of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) Tubes (but Were Afraid to Ask)

- Fellows and Young GIs Section

- Published: 21 April 2023

- Volume 68 , pages 2221–2225, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Dana Ley 1 &

- Sumona Saha 1

3104 Accesses

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastroenterology (GI) fellows are equipped during training with the knowledge of when more permanent routes of enteral feeding are indicated and how to place percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. Though there are prior reviews and guides [ 1 ] to assist GI fellows further in the logistics of this procedure, many practical questions arise regarding PEG tubes from patients and their healthcare teams for which clear evidence-based answers are more difficult to locate. In particular, GI fellows are less likely to learn about the management and removal of gastrostomy tubes than they are about their insertion.

This guide was created to help GI fellows more confidently and efficiently answer commonly asked questions from patients, families, and healthcare team members regarding the management and removal of PEG tubes. We end with suggestions for improvements in clinical documentation, patient education, and interdisciplinary communication that can help reduce confusion regarding PEG tube insertion and management.

The following are examples of questions that might be asked from the providers, the care team, the patient, and their family.

From the Nurse or Registered Dietician: The Primary Team Has Ordered Tube Feeds for a Patient Who Had a PEG Placed Today...How Soon Can We Start the Tube Feeds?

Traditionally, though the initiation of PEG tube feeding is delayed to 12–24 h after tube placement, a meta-analysis and multiple randomized controlled trials reported that patients started on earlier feedings (within 3 h of PEG placement) had no difference in complications, death within 72 h, or the amount of significant gastric residual volume after one day when compared with patients who were started on tube feeds the day after tube placement [ 2 ]. There is no standard of practice regarding the timing of feeding initiation. Since there is no current national consensus, each center or institution has their own practice guidelines. In order to prevent the tube from getting clogged, it should be flushed after each feed as well as before and after administrating any medications.

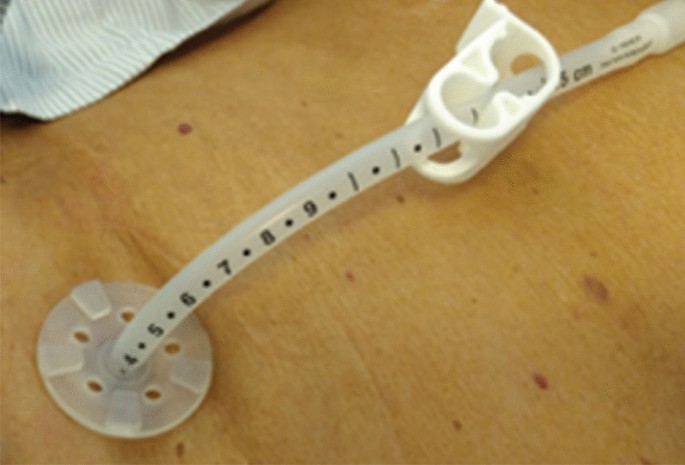

From the Patient’s Facility: How Tight Should the PEG Tube’s External Bolster Be Maintained?

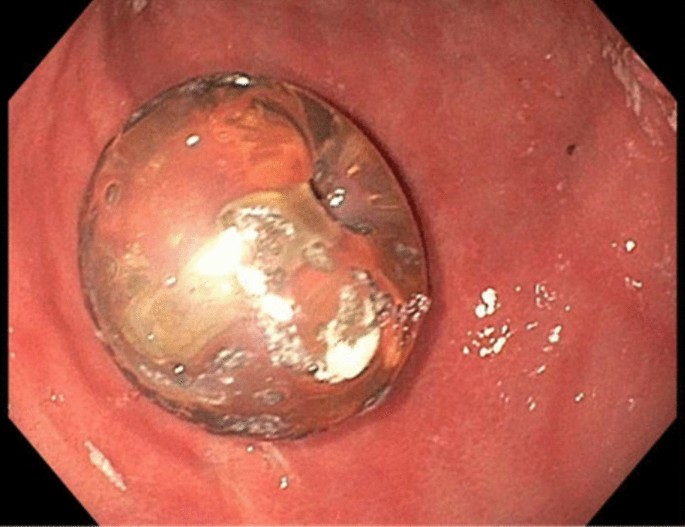

The external bolster of the PEG tube should be positioned loosely enough to allow for 1–2 cm of in-and-out movement of the tube (see Fig. 1 for appropriate tube positioning, Fig. 2 for PEG tube internal balloon-type bolster, and Fig. 3 for too-tight tube positioning leading to the buried bumper syndrome) [ 3 ]. Tissue compression between the internal and external bolsters can lead to pressure necrosis or breakdown of the gastrostomy tract. This loose positioning does not cause leakage around the tube, since a tract forms quickly due to tissue edema and inflammation.

Appropriate PEG tube positioning. Permission for image use obtained from the Journal of Digestive Endoscopy [ 15 ].

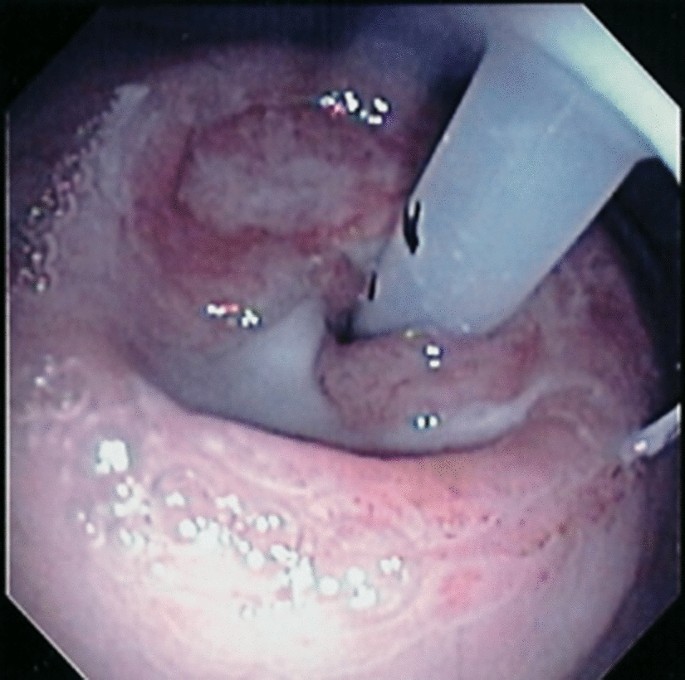

Endoscopic image taken by the authors showing balloon-type internal bolster

Endoscopic image indicating PEG positioning that is too-tight, leading to buried bumper syndrome. Courtesy of Stephen McClave, MD

It is also important to document the initial location of the external bolster after placement in order to guide tube replacement when needed. Ideally, the initial location of the external bolster should be documented in the operative or procedure note on the date of placement and in all follow-up notes regarding the PEG tube. At our institution, we routinely place orders guiding tube care for the nursing staff after PEG placement. We round on all inpatients one day after PEG tube placement in order to ensure that the tube can freely rotate 360˚ and to tighten or loosen the tube if necessary. In the note, we document tube placement date, skin disc level, and the type of tube. We indicate whether or not it is safe to start tube feeds and document that the head of the bed should be elevated ≥ 30° during feedings and for 60 min thereafter. Moreover, we include the title of an institutional patient-focused handout that can be provided to patients upon discharge with further instructions for PEG tube care.

From the Inpatient Nurse: The Patient’s PEG Tube Is Clogged… How Do We Fix It?

Clogging is one of the most common complications of PEG tubes. If possible, all medications should be given in liquid form or dissolved in liquid in attempt to minimize clogging. Furthermore, bulking agents such as psyllium fiber should never be put through the tube. Water (15–30 cc) should be flushed through the tube before and after all medications and after all tube feeds.

If the tube becomes obstructed, it can be flushed with a higher volume syringe (for example, a 60 cc). It is best to use warm water for irrigation [ 4 ]. Coca Cola® has also been cited as a possible alternative to water for flushing since it may help prevent tube clogging and is of similar efficacy to water; nevertheless, evidence for Coca Cola® for resolution of existing clogs is limited and has not been reproducible [ 5 ]. If this does not work, pancreatic enzymes dissolved in bicarbonate can be left to dwell inside the tube [ 6 ]. As a last resort, the tube may be cleared with a brush.

From the Pharmacist: The Formulation of the Medication that Was Ordered Cannot Be Crushed or Administered Through the PEG… Does the Patient Really Need the Medication?

Oral medications need to be prepared properly for administration through the PEG tube. Tablets must be crushed and diluted, and capsules must be opened with the contents diluted. Many liquid forms of medications should also be further diluted prior to enteral administration through the PEG [ 7 ]. Many of the immediate-release tablets can be crushed and diluted before administration through the tube. Sublingual, enteric-coated, extended-release, or delayed-release medications should not be crushed since crushing these medications destroys the drug’s protective coating. Furthermore, crushed enteric-coated tablets may clump and clog PEG tubes [ 7 ]. Crushing these sublingual, extended-release, or delayed-release medications may lead to unpredictable blood levels and dangerous side effects. If it is unclear whether a medication is safe to be crushed and administered through a PEG tube, it should be discussed with a pharmacist prior to its use. Alternative non-enteric-coated or immediate-release options should be substituted when available.

From the Primary Team: The PEG Tube Looks Damaged and Is Leaking… How Do We Remove and Replace It?

Due to the corrosive actions of gastric acid and digestive enzymes, PEG tubes may deteriorate over time. Some signs of tube deterioration include tube discoloration, beading, and foul odor. Though these complications alone will not harm the patient, if the tube breaks and leaks, continuing tube feeds may be challenging or even impossible. In general, the lifespan of a PEG tube is about one year although PEG tubes may last much longer for many patients. One single center retrospective study found that PEG tube lifespan was 1 year for 95.1% of patients and five years for 68.5%. Younger age was associated with earlier PEG failure. [ 8 ]

PEG tubes may also develop peristomal leakage, which usually occurs in the first few days after tube placement but can also occur in patients with a mature gastrostomy tract. Loosening the external bolster may help, as well as improving malnutrition and hyperglycemia. Placing a larger PEG tube through the same tract will only distend the tract further and worsen leakage. In patients who already have a mature tract and develop peristomal leakage, the tube should be fully removed, allowing the tract to completely close, with placement of a new tube at another location.

Since the method of PEG tube removal depends on the type of tube present, it is essential to know which type of tube is in place before attempting to remove it. The term “PEG” should only be used to describe endoscopically placed tubes that initially have a soft internal bolster (bumper) that is located within the stomach and an external bolster, which is placed over the tube, external to the abdominal wall. The internal bolster can deform to enable the tube to be removed through the tract when firm and steady traction is applied, with most tubes designed to withstand 10–14 pounds of external pull force. Radiologically or surgically placed gastrostomy tubes and replacement tubes are removed endoscopically or percutaneously after balloon deflation. Tubes with an internal balloon can be identified by the presence of a printed balloon capacity, generally 5–10 cc, and tube diameter, usually 12–20 Fr., on or near the valve. The balloon is deflated by inserting a straight tip (not Luer Lock®) syringe into the valve and removing as much fluid as possible, after which the tube should slide out easily. If there is any question regarding the type of tube, the patient’s medical record should be searched for operative or procedural notes detailing when the tube was placed and by whom. If the type of tube is incorrectly documented as a PEG tube, confusion and misguided attempts at removal may occur. If the type of tube cannot be determined based on exam and the patient’s medical record, an endoscopy should be performed to determine which type of internal bolster is present. After the tube is removed, the site should be covered with a clean dressing until the tract closes, which typically takes 24–72 h after removal.

Though replacement tubes have a balloon at the distal tip, they should only be placed once the tract has matured, which may take up to 4 weeks after placement. The balloon is inflated after placement with water or saline using a straight tip (not Luer Lock®), with an external bolster placed to secure the tube. If the patient had an internal bolster balloon, and it was deflated early leading to dislodgement of the tube, a replacement tube with a soft bumper rather than an internal balloon should be used.

From the Emergency Department: This Patient’s PEG Tube Was Accidentally Removed… What Do We Do?

PEG tubes may be accidentally removed due to excess traction, especially by patients who are agitated or confused. If this occurs when the tract is mature (at least 4 weeks old), a replacement tube can be placed through the tract. If the appropriate tube is not available, a Foley catheter may be temporarily used. The catheter is placed through the gastrostomy tract after which the balloon at the distal tip is inflated. To create an external bolster, a 2–3-cm piece of tubing can be cut from a second Foley catheter. A hole can be cut into the middle of this piece of tubing, and the tubing of the replacement tube passed through the hole.

Since the gastrostomy tract starts to close within hours, replacement of the tube should occur as soon as possible. If the tube is accidentally removed within the first 4 weeks after placement, it should not be replaced blindly, since the gastric and abdominal walls may have separated in an immature tract, with the possibility of intraperitoneal insertion. If there is concern this may have occurred, a water-soluble contrast dye study through the tube should be obtained emergently to confirm correct positioning before using the tube for feeding to prevent potentially serious complications.

From the Patient’s Caregiver: Buried Bumper Syndrome Sounds Frightening… How Do We Prevent It?

Buried bumper syndrome is a late complication due to the external bolster of the PEG tube being too-tight against the abdominal wall [ 9 ]. Over time, the internal bolster erodes into the gastric wall due to the tension on the tract with consequent pain and the inability to give feeds through the tube. Endoscopy will show that the internal bolster is buried within the gastric wall.

Prevention requires good PEG site care and patient education. It is important to leave enough space between the external bolster and abdominal wall. Gauze pads should only be placed over the external bolster since placing them underneath the bolster can create excess pressure on the gastrostomy tract. The tube itself should be pushed into the wound slightly and rotated during daily tube care, ensuring that the internal bumper does not become buried. It should then be placed back into the initial position.

From the Patient: Can I Go Swimming with a PEG Tube?

Patients may shower with their PEG tube in place as long as they pat the surrounding skin dry afterwards. They should wait for 4 weeks before submerging their PEG tube underwater in a bathtub. Though there is no evidence-based recommendation regarding swimming with a PEG tube, there are, however, multiple patient resource and support group websites discussing this topic. According to the Feeding Tube Awareness Foundation, for example, it is safe to go swimming with a PEG tube as long as the stoma has matured [ 10 ]. Swimming in well-maintained chlorinated or saltwater pools and oceans is preferred over lakes and rivers due to the possibility of unsafe water quality. Hot tubs are also ill-advised, since they often harbor bacteria. If the tube site is exposed to sand or other suspended debris, covering the tube it in a clear, protective dressing or plastic wrap with waterproof tape is recommended.

Infections are one of the more common PEG tube complications. Though most are minor, severe infections such as peritonitis or necrotizing fasciitis may occur [ 11 ]. Signs of possible wound infection include erythema around the tube site, tenderness, and/or purulence. Most of these infections will respond to antibiotics (either a first-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone). If there are signs of a more severe infection, the tube should be removed after which additional antibiotics are started. Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare complication of PEG tube placement, for which patients with diabetes, wound infections, malnutrition, and immunocompromise are at increased risk. Patients should use increased caution with swimming and exposure of their PEG site to water. Maintaining sufficient space between the external bolster and abdominal wall may help to prevent this as well. [ 12 ]

From the Home Health Nurse: The Patient Has a PEG Tube for Venting... How Does This Work?

PEG tubes may be used for venting rather than feeding in patients with chronic nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain related to gastrointestinal obstruction. Gastric decompression through a venting PEG tube can palliate symptoms [ 13 ]. Venting a PEG tube removes air and drains gastric juice in order to improve the above symptoms. When symptoms are under control, the PEG tube can be kept clamped or closed. When the patient becomes nauseated, the tube can be unclamped and allowed to drain until the symptoms improve. After the symptoms have gone away, the tube can again be clamped and eventually removed.

From the Primary Team: The Patient Has a PEG Tube... Can It Be Converted to a PEG-J?

Yes – a PEG tube may be converted endoscopically to a jejunal extension tube (PEG-J). Placement of a PEG-J placement, typically a two-step procedure, is used in patients who cannot tolerate gastric feeding. The first step is placement of the PEG tube, and the second step is insertion of a J extension tube through the PEG tube. Once this is inserted, the J extension tube is grasped with tools placed into the endoscope. The J extension tube is then guided through the stomach, pylorus, and small bowel until it is in position in the jejunum, distal to the ligament of Treitz. The jejunal extension tube may then be clipped to the mucosa [ 14 ].

Conclusions

Although GI fellows may know how to place PEG tubes, they may lack knowledge regarding the nuances of PEG tube management. It is important to know the type of PEG tube and internal bolster present before attempting to remove it. If a PEG tube falls out and needs replacement, it should be done as quickly as possible, given the tract can start to close within hours. Additionally, tube positioning is extremely important; the external bolster should be positioned loosely enough to allow for 1–2 cm of in-and-out movement in order to prevent complications such as buried bumper syndrome.

The common questions included in this article regarding the proper management of PEG tubes come from patients, their caregivers, and their healthcare teams. We hope this guide will help answer some of these frequently asked questions. Notably, improved documentation in patients’ medical records, communication with, and educational resources for patients, families, and members of the healthcare team can help to answer some of these questions up front.

Abdelfattah T, Kaspar M. Gastroenterologist’s guide to gastrostomies. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:3488–3496.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Szary NM, Arif M, Matteson ML et al. Enteral feeding within three hours after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement: a meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:e34–e38.

Gupta A, Singh AK, Goel D et al. Mittal S Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement: a single center experience. Journal of Digestive Endoscopy . 2019. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-3401391 .

Article Google Scholar

Metheny N, Eisenberg P, McSweeney M. Effect of feeding tube properties and three irrigants on clogging rates. Nurs Res. 1988;37:165.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dandeles LM, Lodolce AE. Efficacy of agents to prevent and treat enteral feeding tube clogs. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:676–680.

Sriram K, Jayanthi V, Lakshmi RG et al. Prophylactic locking of enteral feeding tubes with pancreatic enzymes. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1997;21:353.

Grissinger M. Preventing errors when drugs are given via enteral feeding tubes. P T. 2013;38:575–576.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Siau K, Troth T, Gibson E et al. Fisher NC How long do percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tubes last? A retrospective analysis. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94:469–474.

Klein S, Heare BR, Soloway RD. The “buried bumper syndrome”: a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:448.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Swimming, traveling, and camping. Feeding Tube Awareness Foundation; [Accessed 2022 Dec 28]. http://www.feedingtubeawareness.org/swimming/

Sharma VK, Howden CW. Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of antibiotic prophylaxis before percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3133.

Hucl T, Spicak J. Complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2016;30:769.

Teriaky A, Gregor J, Chande N. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement for end-stage palliation of malignant gastrointestinal obstructions. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2012;18:95–98.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Simons-Linares CR, Milano R, Bartel MJ. PEG-J tube placement with optimization of J tube insertion. VideoGIE. 2021;6:112–113.

Gupta A, Singh AK, Goel D et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement: a single center experience. J Digest Endosc 2019;10:150–154.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Wisconsin, 1685 Highland Avenue, 4000 MFCB, Madison, WI, 53705, USA

Dana Ley & Sumona Saha

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dana Ley .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ley, D., Saha, S. Everything that You Always Wanted to Know About the Management of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) Tubes (but Were Afraid to Ask). Dig Dis Sci 68 , 2221–2225 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-07944-y

Download citation

Accepted : 20 March 2023

Published : 21 April 2023

Issue Date : June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-07944-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Request An Appointment

- Pay a Bill or Get an Estimate

- For Referring Providers

- Pediatric Care

- Cancer Center

- Carver College of Medicine

- Find a Provider

- Share Your Story

- Health Topics

- Educational Resources & Support Groups

- Clinical Trials

- Medical Records

- Info For... Directory

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) tube

What is a peg tube.

It is a soft, plastic feeding tube. It goes into your stomach. Liquid, such as formula, fluids, and medicines can be put through the PEG tube if you cannot eat or drink all the nutrients you need. It can also be used to take air and fluid out of your stomach.

How do I get a PEG tube?

You go to the Digestive Health Center to get a PEG tube placed. A tool called an endoscope (scope) is used. It is a small camera with a light on a thin, flexible tube. It goes down into your mouth, through your esophagus (food pipe), and into your stomach. The light helps your doctor find the best place to put the PEG tube.

Your care team will start an intravenous (IV) catheter. They will give you medicine through the IV to help you relax. Your doctor will also give you local anesthesia. This is a shot of medicine in your skin to numb the site where the cut is made. These keep you from having pain while getting the PEG tube.

Your doctor will make a small incision (cut in your skin). Then, they put the PEG tube in an opening in your stomach. This is called a stoma. A small balloon is blown up on the end of the PEG tube inside your stomach and a small disc is on the outside to hold it in place.

What are the risks of getting a PEG tube?

- Damage or bleeding in your esophagus and stomach from the scope

- Lung infection due to liquid in your stomach getting into your lungs

- Bruising, pain, and sores around your stoma

- An infected stoma

- The end of the PEG tube moving out of place

- The PEG tube can get blocked, crack, break, and leak

Will it hurt getting a PEG tube?

You will be given medicines in an IV to help you relax. These will make you sleepy. You may not feel pain or remember the procedure. You may feel pressure or pushing during the procedure.

You may have a little pain after it is in. Take mild pain medicine to help.

How do I get ready for the PEG tube procedure?

Your medicines may need to stop or change before your PEG tube is put in. Call the doctor who ordered your medicines at least 2 weeks before your procedure.

Blood thinners: Call the doctor that orders your medicines, such as Coumadin® (warfarin), Plavix® (clopidogrel), Ticlid® (ticlopidine hydrochloride), Agrylin® (anagrelide), Xarelto® (rivaroxaban), Pradaxa® (dabigatran), and Effient® (prasugrel).

Insulin or diabetes pills: Call the doctor that watches your sugar levels. Your doses may need to change because of the diet needed. Bring them with you on the day of your procedure.

Give your care team a list of your medicines and doses. Tell your care team if you use any herbs, food supplements, or over-the-counter medicine. Tell your care team if you have any allergies.

1 day before your procedure

- You may eat and drink as normal.

- Do not drink alcohol the day before or day of your procedure.

- Do not eat or drink after midnight the night before your morning procedure. If your procedure is in the afternoon , you may drink clear liquids up to 2 hours before your check-in time.

The day of your procedure

Your care team will ask you to sign a legal paper called a consent form. It will tell you about the procedure and the risks. Signing the form gives your doctor permission to place your PEG tube. Make sure all your questions are answered before you sign the form.

After your procedure

You stay in a recovery room until you are fully awake. Then you will go home or to your hospital room. It is normal to have a sore throat for 2 to 3 days.

When should I call my doctor?

Call your doctor if:

- The skin around your PEG tube is red, hot, hurts to touch, or has greenish-yellow drainage

- You have a fever

- The tube feels tight around your skin

- The skin around your PEG tube breaks down

- Skin grows over your tube

- Your stoma (the opening in your skin) gets bigger

- You have a lot of leaking around your tube (some leaking is normal)

- Your tube gets blocked

- Your tube is cracked or breaks

- Your tube comes out

- You have any questions or concerns

Call your primary care doctor if:

- You have nausea (feel like you are going to throw up) or vomiting (throwing up)

- You cannot have a bowel movement

How do I take care of a PEG tube?

- It may take 4 to 6 weeks for the skin around the PEG tube to heal.

- Clean the skin around your PEG tube each day or if it is dirty with mild soap and water. Try to gently remove any drainage or crusting on the skin or tube. Let your skin dry all the way under the disc.

- Do not place gauze between the disc and skin.

- Do not use any ointments, powders, or sprays around the PEG tube.

- Do not pull your PEG tube. It can move out of place or come out.

- Close your PEG tube and tape it to your stomach when you are not using it.

Can I take a bath or go swimming?

Yes. You can do your normal activities after the skin around your PEG tube heals. Be sure it is closed before getting into a pool or tub.

What can I put in a PEG tube?

Liquid, such as formula, fluids, and medicines can be put through the PEG tube. Do not put pills into your PEG tube.

A dietitian will talk with you about the commercial formulas that are best for you. They will help you get a balanced diet with all the vitamins and minerals you need. They will talk to you about how much and how often to give yourself the formula. Use these formulas so your tube does not get blocked.

Before you start putting medicine or feedings in the tube, check for:

- Leftover liquid in your PEG tube and stomach

- Cracks or breaks in the PEG tube

Will I give myself feedings at normal meal times?

- Follow the instructions from your dietitian.

- Give yourself feedings at any time during the day or night. Some people feed themselves at normal mealtimes. Some people choose other times during the day or overnight.

- No matter when you feed yourself, it may be nice to sit with your family during meals to share and talk. Also, be sure you choose feeding times that let you get enough sleep.

Can I give myself medicine through a PEG tube?

You can give yourself medicine that is liquid or finely crushed and dissolved in water. Never mix medicines. Always flush the tube with a little water between each medicine and after the last medicine is given.

Will I taste anything?

Your taste buds are on your tongue. So, you will not taste food given through your PEG tube. You might be able to taste something if you burp after a feeding.

Can I eat or drink after a PEG tube is put in?

It depends why you needed the PEG tube. Talk with your care team about eating and drinking.

It is often okay to eat and drink if you needed the PEG tube because of:

- Weight loss

- Not being able to gain weight

- Just in case you are not able to eat enough

If your care team tells you it is okay to eat and drink, you cannot do so until your gag reflex returns.

Talk with your care team about what is safe to eat and drink if you:

- Have problems swallowing

- Aspirate (food or drink goes down your windpipe into your lungs)

- Needed the PEG tube to keep your stomach empty

Some people should not eat or drink anything. Some people can eat and drink different amounts and consistencies in certain positions.

What if the PEG tube falls out?

Do not panic if your PEG tube ever falls out. Put a clean, dry towel over the opening to catch drainage. Then, go to your doctor or emergency room to get another tube put in. The opening can close quickly, so get it put back in as soon as you can.

Will the PEG tube leak?

- It can leak a small amount. Clean and dry the skin around the tube if it does leak, so you do not get skin breakdown or sores.

- Keep gauze or absorbent pads on the PEG tube. This keeps the skin dry and protects your clothes. Take extra pads and clothes with you when you leave your home.

- The tube may need to be changed if it leaks more than a little.

Will people know I have PEG tube?

A PEG tube is small. It is hidden by your clothing. People will only know you have a PEG tube if you show them.

Will I have a PEG tube forever?

This depends on your weight, health, eating habits, and if you can swallow. Talk with your care team about this.

The contents of this website are for information purposes only and not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Users should not rely on the information provided for medical decision making and should direct all questions regarding medical matters to their physician or other health care provider. Use of this information does not create an express or implied physician-patient relationship.

Combined tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

- PMID: 3115126

- DOI: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90608-9

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is rapidly becoming the preferred method of long-term enteral access with minimal complications obviating the need for prolonged nasogastric or orogastric intubation. Tracheostomy is the accepted technique for long-term airway control, especially for protection against upper airway secretions and respiratory failure. Over a 14 month period, 73 percutaneous gastrostomies were inserted in 71 patients. Nine patients (12.6 percent) had previously undergone tracheostomy, and 13 patients (18.3 percent) underwent a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy immediately after tracheostomy. All procedures were performed under local anesthesia. The concomitant percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy added little time to the total procedure and was not associated with additional complications. Early experience with percutaneous gastrostomy indicates that a substantial number of patients (30.9 percent in the present study) also required tracheostomy. The tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy combination completely frees the nasopharynx of indwelling tubes. Concomitant percutaneous gastrostomy should be considered in patients undergoing tracheostomy.

- Anesthesia, Local

- Enteral Nutrition

- Gastroscopy

- Gastrostomy / methods*

- Middle Aged

- Respiration, Artificial

- Tracheotomy / methods*

Thanks for visiting! GoodRx is not available outside of the United States. If you are trying to access this site from the United States and believe you have received this message in error, please reach out to [email protected] and let us know.

How to Use and Care for your Peg Tube

Medically reviewed by Drugs.com. Last updated on Apr 2, 2024.

- Español

What do I need to know about a PEG tube?

A PEG tube is a soft, plastic feeding tube that goes into your stomach. Healthcare providers will teach you how to put liquid food and certain medicines through the tube. You will also be taught how to care for the PEG tube and the skin where the tube enters your body.

How do I use a PEG tube for feedings?

Your healthcare provider will tell you when and how often to use your PEG tube for feedings. A bolus feeding means nutrition is given over a short period of time. An intermittent feeding is scheduled for certain times throughout the day. Continuous feedings run all the time. The following are types of PEG tube systems:

- A feeding syringe helps liquid food to flow steadily into the PEG tube. The syringe is connected to the end of the PEG tube. You will pour the liquid into the syringe and hold it up high. The syringe plunger may be used to gently push the last of the liquid through the PEG tube.

- A gravity drip bag allows liquid food to drip more slowly into the PEG tube. The tubing from the gravity drip bag is connected to the end of the PEG tube. You will pour the liquid into the bag. The bag hangs on a medical pole or similar device. You can adjust the flow rate on the tubing according to your healthcare provider's instructions.

- An electric feeding pump controls the flow of the liquid food into your PEG tube. Your healthcare provider will teach you how to set up and use the pump.

How do I care for my PEG tube?

- Always flush your PEG tube before and after each use. This helps prevent blockage from formula or medicine. Use at least 30 milliliters (mL) of water to flush the tube. Follow directions for flushing your PEG tube.

- If your PEG tube becomes clogged, try to unclog it as soon as you can. Flush your PEG tube with a 60 mL syringe filled with warm water. Never use a wire to unclog the tube. A wire can poke a hole in the tube. Your healthcare provider may have you use a medicine or a plastic brush to help unclog your tube.

- Check the length of the tube from the end to where it goes into your body. If it gets longer, it may be at risk for coming out. If it gets shorter, let your healthcare provider know right away.

- Check the bumper. The bumper is a piece that goes around the tube, next to your skin. It should be snug against your skin. Tell your healthcare provider if the bumper seems too tight or too loose.

- Use an alcohol pad to clean the end of your PEG tube. Clean before you connect tubing or a syringe to your PEG tube and after you remove it. Do not let the end of the PEG tube touch anything.

How do I care for the skin around my PEG tube?

- Clean the skin around your tube 1 to 2 times each day. Ask your provider what you should use to clean your skin. Check for redness, swelling, or pus in the area where the tube goes into your body. Check for fluid draining from your stoma (the hole where the tube was put in).

- Gently turn your tube daily after your stitches come out. This may decrease pressure on your skin under the bumper. It may also help prevent an infection.

- Keep the skin around your PEG tube dry. This will help prevent skin irritation and infection.

- Use topical medicines as directed. You may need to put antibiotic cream on the skin around your tube after you are done cleaning it.

What else do I need to know about a PEG tube?

- Keep a record of liquids you have each day. You may also need to keep a record of how much you urinate and how many times you have a bowel movement each day. Bring this record to your follow-up visits.

- Take your medicines as directed. Learn which of your medicines can be crushed, mixed with water, and given through the PEG tube. Certain medicines should not be crushed or may clog the PEG tube.

- Go to all follow-up appointments. You may need to have blood tests and other tests when you see your healthcare provider.

When should I seek immediate care?

- You start coughing or vomiting during or after a feeding.

- You have severe abdominal pain.

- Blood or tube feeding fluid leaks from the PEG tube site.

- Your PEG tube comes out.

- Your mouth feels dry, your heart feels like it is beating too fast, or you feel weak.

When should I call my doctor?

- You have a fever.

- Your PEG tube is shorter or longer than it was when it was put in.

- You have nausea, diarrhea, or abdominal bloating or discomfort.

- You have stomach pain after each feeding or when you move around.

- You have discomfort or pain around your PEG tube site.

- The skin around your PEG tube is red, swollen, or draining pus.

- You weigh less than your healthcare provider says you should.

- You have questions or concerns about your condition or care.

Care Agreement

© Copyright Merative 2024 Information is for End User's use only and may not be sold, redistributed or otherwise used for commercial purposes.

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.

Medical Disclaimer

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

PEG tube insertion - discharge

A PEG (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) feeding tube insertion is the placement of a feeding tube through the skin and the stomach wall. It goes directly into the stomach. PEG feeding tube insertion is done in part using a procedure called endoscopy.

Feeding tubes are needed when you are unable to eat or drink. This may be due to stroke or other brain injury, problems with the esophagus, surgery of the head and neck, or other conditions.

Your PEG tube is easy to use. You (or your caregiver) can learn to care for it on your own and even give yourself tube feedings.

About PEG Tubes

Here are the important parts of your PEG tube:

- PEG/Gastrostomy feeding tube.

- 2 small discs that are on the outside and the inside of the gastrostomy opening (or stoma) in your stomach wall. These discs prevent the feeding tube from moving. The disc on the outside is very close to the skin.

- A clamp to close off the feeding tube.

- A device to attach or fix the tube to the skin when not feeding.

After you have had your gastrostomy for a while and the stoma is established, something called a button device can be used. These make feedings and care easier.

The tube itself will have a mark that shows where it should be leaving the stoma. You can use this mark whenever you need to confirm the tube is in the correct position.

What you Will Need to Know

Things you or your caregivers will need to learn include:

- Signs or symptoms of infection

- Signs that the tube is blocked and what to do

- What to do if the tube is pulled out

- How to hide the tube under clothes

- How to empty the stomach through the tube

- What activities are ok to continue and what to avoid

Feedings will start slowly with clear liquids, and increase slowly. You will learn how to:

- Give yourself food or liquid using the tube

- Clean the tube

- Take your medicines through the tube

If you have any pain, it can be treated with medicine.

Caring for the PEG-tube Site

Drainage from around the PEG tube is common for the first 1 or 2 days. The skin should heal in 2 to 3 weeks.

You will need to clean the skin around the PEG-tube 1 to 3 times a day.

- Use either mild soap and water or sterile saline (ask your health care provider). You may use a cotton swab or gauze.

- Try to remove any drainage or crusting on the skin and tube. Be gentle.

- If you used soap, gently clean again with plain water.

- Dry the skin well with a clean towel or gauze.

- Take care not to pull on the tube itself to prevent it from being pulled out.

For the first 1 to 2 weeks, you provider will likely ask you to use sterile technique when caring for your PEG-tube site.

Your provider may also want you to put a special absorbent pad or gauze around the PEG-tube site. This should be changed at least daily or if it becomes wet or soiled.

- Avoid bulky dressings.

- Do not put the gauze under the disc.

Do not use any ointments, powders, or sprays around the PEG-tube unless told to do so by your provider.

Ask your provider when it is ok to shower or bathe.

Keeping the PEG-tube in Place

If the feeding tube comes out, the stoma or opening may begin to close. To prevent this problem, tape the tube to your abdomen or use the fixation device. A new tube should be placed right away. Call your provider for advice on next steps.

Your provider can train you or your caregiver to rotate the gastrostomy tube when you are cleaning it. This prevents it from sticking to the side of the stoma and opening that leads to the stomach.

- Make note of the mark or guide number of where the tube exits the stoma.

- Detach the tube from the fixation device.

- Rotate the tube a bit.

When to Call the Doctor

You should contact your provider if:

- The feeding tube has come out and you do not know how to replace it

- There is leakage around the tube or system

- There is redness or irritation on the skin area around the tube

- The feeding tube seems blocked

- There is a lot of bleeding from the tube insertion site

Also contact your provider if you:

- Have diarrhea after feedings

- Have a hard and swollen belly 1 hour after feedings

- Have worsening pain

- Are on a new medicine

- Are constipated and passing hard, dry stools

- Are coughing more than normal or feel short of breath after feedings

- Notice feeding solution in your mouth

Alternative Names

Gastrostomy tube insertion-discharge; G-tube insertion-discharge; PEG tube insertion-discharge; Stomach tube insertion-discharge; Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube insertion-discharge

Samuels LE. Nasogastric and feeding tube placement. In: Roberts JR, Custalow CB, Thomsen TW, eds. Roberts and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care . 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 40.

Twyman SL, Davis PW. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement and replacement. In: Fowler GC, ed. Pfenninger and Fowler's Procedures for Primary Care . 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 92.

Review Date 8/9/2023

Updated by: Michael M. Phillips, MD, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Related MedlinePlus Health Topics

- Nutritional Support

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clin Endosc

- v.56(4); 2023 Jul

- PMC10393568

Clinical practice guidelines for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Chung hyun tae.

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

Moon Kyung Joo

3 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Chan Hyuk Park

4 Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University Guri Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Guri, Korea

Eun Jeong Gong

5 Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University College of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea

Cheol Min Shin

6 Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

7 Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Anyang, Korea

Hyuk Soon Choi

8 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Miyoung Choi

9 National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency, Seoul, Korea

Sang Hoon Kim

10 Department of Gastroenterology, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

11 Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research–Metabolism, Obesity & Nutrition Research Group, Seoul, Korea

Chul-Hyun Lim

12 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Eunpyeong St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

13 Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-The Research Group for Endoscopes and Devices, Seoul, Korea

Jeong-Sik Byeon

14 Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Ki-Nam Shim

Geun am song.

15 Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University Hospital, Pusan National University College of Medicine and Biomedical Research Institute, Busan, Korea

Moon Sung Lee

16 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Korea

Jong-Jae Park

Oh young lee.

17 Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Associated Data

With an aging population, the number of patients with difficulty in swallowing due to medical conditions is gradually increasing. In such cases, enteral nutrition is administered through a temporary nasogastric tube. However, the long-term use of a nasogastric tube leads to various complications and a decreased quality of life. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is the percutaneous placement of a tube into the stomach that is aided endoscopically and may be an alternative to a nasogastric tube when enteral nutritional is required for four weeks or more. This paper is the first Korean clinical guideline for PEG developed jointly by the Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research and led by the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. These guidelines aimed to provide physicians, including endoscopists, with the indications, use of prophylactic antibiotics, timing of enteric nutrition, tube placement methods, complications, replacement, and tube removal for PEG based on the currently available clinical evidence.

INTRODUCTION

With an aging population, the number of patients with difficulty in swallowing due to medical conditions is gradually increasing. Enteral feeding can be provided temporarily through a nasogastric tube; however, nasogastric tubes are typically replaced every four to six weeks. In addition, complications such as aspiration pneumonia due to regurgitation of the stomach contents, ulcers, and bleeding because of nasogastric tube may occur. 1 Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is the percutaneous placement of a tube into the stomach and may be an alternative to a nasogastric tube. PEG should be considered when enteral nutrition is required for four weeks or more.