- EN - English

- PT - Portuguese

- ES - Spanish

- How it works

- Become a Host

- Download the app

Top Destinations

- United States

- United Kingdom

What type of experience are you looking for?

- Non-Profit School

- Permaculture project

- Eco Village

- Holistic Center

- Guest House

- How Worldpackers works

Learn from the most experienced travelers of the community

Traveling with worldpackers, planning and budgeting for travel, make a living while traveling as a lifestyle, travel with worldpackers.

- Using Worldpackers

- Work exchange

- Social impact

Plan your trip

- Women traveling

- Budget travel

- Solo travel

- Language learning

- Travel tips

- Get inspired

- Digital nomads

- Travel jobs

- Personal development

- Responsible travel

- Connect with nature

Top destinations

- South America

- Central America

- North America

- More destinations

- WP Life WP Life

- Exclusive discounts Discounts

What is rural tourism and what are its benefits?

Rural tourism means travelling to non urbanised places with low population. An incredible chance to connect with local communities, support them and immerse yourself in their local culture.

Joanna Joanna Roams Free - Ethical and Responsible Travel

Apr 18, 2023

A truly authentic and raw way to travel, rural tourism is on the rise, as more people seek tranquility and unique travel experiences.

What is rural tourism and what are the benefits?

Rural tourism is a form of tourism that goes beyond city breaks and popular tourist attractions.

Rural tourism is travel to natural places that are non-urbanised, often rely on agriculture and with low populations , such as villages and cottages, homestays, farms, and ranches or eco lodges.

Possible sctivities when rural travelling are camping, hiking, outdoor sports and spending time connecting with the nature.

It is related to ethical and sustainable tourism, travelling off the beaten path , outdoor activities and sports and spending time in nature. It has a great potential to make the travel more responsible and richer in experience.

When travelling in rural areas the traveller really gets to observe the local life, stay away from crowds and touristy prices, and grasp the benefits of being outdoors.

In developing countries, rural tourism has a great importance. It brings profit directly to families living in rural, otherwise non touristic, distant locations. It also brings opportunities for development. In developed countries it allows for relaxation and rest from otherwise busy lives. In any country, it helps to reduce bad effects of over tourism.

What are the different types of rural tourism?

Eco-tourism

This is travel to natural areas whilst being sustainable, responsible, and mindful of our impact on the host community and the planet.

This type of travel includes staying in eco lodges or eco hotels or other accommodations that use renewable energy.

It takes place in non-urban locations such as mountains, forests, or watersides , eco-tourism is a fantastic opportunity to connect with nature and travel off the beaten path.

This is a great option for all that care about the planet and that try to leave as least of negative impact as possible.

Community based tourism

Community tourism is focused on spending time with the locals. This is achieved by staying in guesthouses in rural locations , often with families that are underprivileged or/and marginalised.

This enables cultural exchange for both sides. Community based tourism is a great concept for the hosts, as it not only allows them to broaden their horizons by making connections with people from all over the world, but also creates jobs and motivates the society to learn new skills and languages.

In this scenario, money made from tourists stays in the community and allows for development and other projects that will benefit the whole community.

Environmental volunteer tourism

Being an environmental volunteer means giving back to the earth. It could include gardening, planting plants or trees, conservation, bio construction, clean ups and recycling and more.

An environmental volunteer leaves a positive impact and expands their environmental consciousness. Perfect concept for all nature lovers.

Volunteering with Worldpackers is a great start, as even if you do not have much gardening experience you can still sign up to projects, and you will learn on the job!

Read this article to find out more about the Worldpackers experience.

Outdoor sports tourism

Outdoor adventure tourism takes place in non-urbanised areas such as mountains, lakes, rivers, deserts, or other remote, distant places.

The outdoors offers many different activities such as: bikepacking holidays in the countryside , multiday hikes in the mountains, rock climbing, summiting volcanoes , kayaking, rafting and many, many more!

This is type of rural tourism is a great way to be more active, step out of your comfort zone and try new things!

Check out this article on how to prepare for your next adventure!

Where to go for rural tourism?

To really get to know the local life , consider staying for longer and volunteering with Worldpackers .

This is an incredible opportunity to really get to know the place, live like a local, be a part of your host family, learn more about the local culture and history, and learn new skills!

The United Kingdom

With 15 National Parks and 38 AONBs , the United Kingdom is the perfect destination for rural tourism.

There are opportunities to practise adventure sports in every park. UK’s National Cycle Network spreads all over the country and allows access to many rural areas that are rich in culture, history, and wonderful, unique landscapes. The British countryside is full of small villages with warm and welcoming communities.

There are over hundred volunteering opportunities all over the United Kingdom! That includes England , Wales , Scotland and Northern Ireland !

- If spending a month living in rural Scottish village in exchange of some gardening work, sounds like a dream to you consider applying today!

- If you are an animal lover and would like to explore the local life in Wales you can help at this small and vegan animal sanctuary.

- For those that are inspired to learn more about permaculture and natural farming, and would like to take care of small animals, you can apply for this experience in Northern Ireland. This project will expand your environmental consciousness and allow you to immerse in the local culture and the small, warm communities of rural Northern Ireland.

- There are also opportunities available for those that prefer to be social and enjoy working with people. This hotel in the New Forest National Park, England is looking for volunteers that will take care of their guests. This opportunity is excellent for travellers that enjoy connecting with the locals, or would like to improve their English.

With 64.61% of the country considered rural, India is another great destination for rural tourism.

Travelling through rural India is an authentic and raw travel. This is where a traveller can really get to see the local life. Learn more about life in India and the struggles of Indians living in rural areas, that are often, unfortunately affected by poverty. Sacrifice some of your time to help local communities or the planet, by volunteering with Worldpackers in India .

- Stay in the heart of the tea plantations and hills, and spend your time at a charity home for underprivileged people of all ages from India. Volunteer’s task include gardening, watering, teaching, housekeeping or nursing.

- Explore the rural Indian Himalayas whilst volunteering with a local NGO. When volunteering at Rural Organisation for Social Elevation you will get the chance to improve the health and education of underprivileged population of the area.

- If you want to learn more about sustainable living whilst living on farm full of tea plantations, coffee beans, pepper, cardamom, and fruits, consider this opportunity in rural India. This is a perfect location for those that like peace and tranquillity and spending time in the nature.

The USA is home to some of the most popular and most beautiful National Parks in the world. With 63 of them in total, and a lot of rural states, the USA is a country full of opportunities to practise rural tourism and volunteer at the same time.

- You can spend your time doing organic farming in the Matanuska Valley of Alaska. This is an incredibly beautiful part of this rural state, and this project will allow you to connect with nature and expand your environmental consciousness.

- If you prefer to be warm, you can help with gardening in the Arizona desert. This activity helps to mitigate the impacts of the changing climate.

- Live the ‘Wild West’ experience and help with daily activities at a ranch in Texas. Activities include taking care of animals, growing food all whilst living with a local family.

- If your dream is explore the gorgeous Hawaiian state, you should consider becoming a farming helper on a sustainable and organic farm in Hawaii. A fantastic opportunity to learn more about sustainability, connect with nature and explore Hawaii on a budget .

- Learn more about regenerative farming, tree corps and gardening when volunteering in a small village in Ohio. Great way to give back to nature, and connect with the local communities.

Read about the experience of traveling in the USA as a work exchanger in this article.

Here I mentioned some opportunities in the UK, India and USA, but there are tons of projects of rural tourism to volunteer around the world .

Rural tourism, when well-managed, can really be successful and beneficial for local communities and the traveller. However, there can be some negative impacts of rural tourism that are worth mentioning.

Some areas are not prepared or educated enough to host tourists. This can cause damage to the environment or directly to the communities. Most troubling negative effect of rural tourism is that it can increase housing prices and other living costs for the local communities. If badly managed, it can cause overcrowding and damage to the natural area.

Hopefully this article has inspired you to widen your horizons and go beyond the tourist trail. Be a conscientious traveller and give back to the planet and hosts on your next trip by volunteering with Worldpackers.

Subscribe to the Worldpackers Community for free and start saving your favorite volunteer positions until you are ready to get verified.

Join the community!

Create a free Worldpackers account to discover volunteer experiences perfect for you and get access to exclusive travel discounts!

Joanna Nowak

Joanna Roams Free - Ethical and Responsible Travel

Hey! My name is Joanna, and I have been travelling full time for over 3 years now. During my travels I like to explore the social, political and economic affairs of the countries I visit. I love to learn more about locals and their lives in their homes. I love to dive deep and get off the beaten path to see what the country is really like when the tourists are not looking. I value and always prioritise responsible and raw travel that leaves positive impact on the society and myself.

Be part of the Worldpackers Community

Already have an account, are you a host, leave your comment here.

Write here your questions and greetings to the author

Aug 27, 2022

[email protected]

Nov 08, 2022

One of the great post on google. Thanks for Sharing.

More about this topic

Working on a farm: a guide on how and where to find opportunities

How to be an environmental volunteer: 10 opportunities around the world

Beyond the glass: eco-volunteering at a winery in sicily with worldpackers.

How do Worldpackers trips work?

As a member, you can contact as many hosts and travel safely as many times as you want.

Choose your plan to travel with Worldpackers as many times as you like.

Complete your profile, watch the video lessons in the Academy, and earn certificates to stand out to hosts.

Apply to as many positions as you like, and get in contact with our verified hosts.

If a host thinks you’re a good fit for their position, they’ll pre-approve you.

Get your documents and tickets ready for your volunteer trip.

Confirm your trip to enjoy all of the safety of Worldpackers.

Have a transformative experience and make a positive impact on the world.

If anything doesn’t go as planned with a host, count on the WP Safeguard and our highly responsive support team!

After volunteering, you and your host exchange reviews.

With positive reviews, you’ll stand out to hosts and get even more benefits.

Why Rural Tourism Is The Next Big Thing

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Rural tourism is an important part of the tourism industry around the world. From walks in the Brecon Beacons , to climbing Mount Kilimanjaro to eco tourism in The Gambia , many destinations rely on their rural tourism provision to bring in much needed revenue for the local economy.

But what does rural tourism actually mean? What is it all about? In this article I will explain what is meant by the term rural tourism, providing a range of academic and industry-based definitions. I will then discuss the importance of rural tourism, activities commonly found in rural tourism destinations and destinations offering rural tourism. I will also assess the positive and negative impacts of rural tourism.

What is rural tourism?

Rural tourism definitions, national parks, areas of outstanding natural beauty (aonbs), sites of special scientific interest, sacs, spas and ramsar sites, national and local nature reserves, heritage coasts and european geoparks, why is rural tourism important, natural england, visitbritain, the national trust, forestry commission, national park authorities, employment generation, benefits to wider economy through taxes, boosts local businesses, local community can use newly developed infrastructure and services, cultural exchange, revitalisation of traditions, customs and crafts, environmental protection and conservation, pressure on public services , increased price of land and real estate, congestion and overcrowding , inappropriate or too much development, restricting access, training schemes for local population, community-based rural tourism, promoting traditional artefacts, improving public transport systems, traffic management schemes, conservation projects, repairing the paths, stone pitching, rural tourism activities, rural tourism in greece, rural tourism in canada, rural tourism in sri lanka, rural tourism in australia, rural tourism: conclusion, further reading.

Rural tourism is tourism which takes place in non-urbanised areas. These areas typically include (but are not limited to) national parks, forests , countryside areas and mountain areas.

Rural tourism is closely aligned with the concept of sustainable tourism , given that it is inherently linked to green spaces and commonly environmentally-friendly forms of tourism, such as hiking or camping.

Rural tourism is an umbrella term. The rural tourism industry includes a number of tourism types, such as golfing tourism, glamping or WOOFING .

Rural tourism is distinguished from urban tourism in that it typically requires the use of natural resources.

As with many types of tourism , there is no universally accepted definition of rural tourism. In fact, the term is actually quite ambiguous.

When defining the term rural tourism it is important first and foremost to understand what is and what isn’t ‘rural’.

The OECD defines a rural area as, ‘at the local level, a population density of 150 persons per square kilometre. At the regional level, geographic units are grouped by the share of their population that is rural into the following three types: predominantly rural (50%), significantly rural (15-50%) and predominantly urbanised regions (15%).

The Council of Europe further state that a ‘rural area’ is an area of inland or coastal countryside, including small towns and villages, where the main part of the area is used for:

- Agriculture, forestry, aquaculture, and fisheries.

- Economic and cultural activities of country-dwellers.

- Non-urban recreation and leisure areas or nature reserves.

- Other purposes such as housing.

Now that we know a little bit more about the ‘rural’ part, it is also important to understand what is meant by the term ‘tourism’. There are many definitions of tourism , but it is generally recognised that a tourist is a person who travels away from their home residence for at least 24 hours for leisure or business purposes.

It appears, therefore, that a person who travels to an area that is sparsely populated for more than 24 hours for leisure or business purposes is likely to qualify as a ‘rural tourist’.

The World Tourism Organisation , provide a little more clarity. They state that rural tourism is ‘a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s experience is related to a wide range of products generally linked to nature-based activities, agriculture, rural lifestyle / culture , angling and sightseeing’.

Dernoi states that rural tourism occurs when there are activities in a ‘non-urban territory where human (land-related economic) activity is going on, primarily agriculture’.

The OECD prescribes that rural tourism should be:

- Located in rural areas.

- Functionally rural, built upon the rural world’s special features; small-scale enterprises, open space, contact with nature and the natural world, heritage, traditional societies, and traditional practices.

- Rural in scale – both in terms of building and settlements – and therefore, small scale.

- Traditional in character, growing slowly and organically, and connected with local families.

- Sustainable – in the sense that its development should help sustain the special rural character of an area, and in the sense that its development should be sustainability in its use of resources.

- Of many different kinds, representing the complex pattern of the rural environment, economy, and history.

Gökhan Ayazlar & Reyhan A. Ayazlar (2015) have collated a number of academic definitions of rural tourism. You can see a summary of this below.

Types of rural tourism areas

There are many different types of rural areas that are popular tourism destinations. These may be named slightly differently around the world. Here are some examples from the UK:

There are 15 National Parks in the UK which are protected areas because of their beautiful countryside, wildlife and cultural heritage.

A national park is a protected area. It is a location which has a clear boundary. It has people and laws that make sure that nature and wildlife are protected and that people can continue to benefit from nature without destroying it.

People live and work in the National Parks and the farms, villages and towns are protected along with the landscape and wildlife.

National Parks welcome visitors and provide opportunities for everyone to experience, enjoy and learn about their special qualities.

National Parks were first mentioned in 1931 in a government inquiry, however no action was taken. Public discontent led to a mass trespass on Kinder Scout (in the now known Peak District), five men were arrested. This led the Council for the protection for Rural England making and releasing a film in the cinemas calling for public help.

This public pressure culminates in the 1945 white paper on National Parks, leading to the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. In 1951 the Peak District became the first National Park.

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is exactly what it says it is: a precious landscape whose distinctive character and natural beauty are so outstanding that it is in the nation’s interest to safeguard them.

There are 38 AONBs in England and Wales. Created by the legislation of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act of 1949, AONBs represent 18% of the Finest Countryside in England and Wales. There are also 8 AONBs in Northern Ireland . Gower was the first AONB established in 1956.

Their care has been entrusted to the local authorities, organisations, community groups and the individuals who live and work within them or who value them.

Each AONB has been designated for special attention by reason of their high qualities. These include their flora, fauna, historical and cultural associations as well as scenic views.

AONB landscapes range from rugged coastline to water meadows to gentle downland and upland moors.

Sites of Special Scientific Interests are the country’s very best wildlife and geological sites.

SSSIs include some of the most spectacular and beautiful habitats; wetlands teeming with wading birds, winding chalk rivers, flower-rich meadows, windswept shingle beaches and remote upland peat bogs.

There are over 4,100 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) in England, covering around 8% of the country’s land area. More than 70% of these sites (by area) are internationally important for their wildlife and designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), Special Protection Areas (SPAs) or Ramsar sites.

Special Areas of Conservation are areas which have been given special protection under the European Union’s Habitats Directive.

They provide increased protection to a variety of wild animals, plants and habitats and are a vital part of global efforts to conserve the world’s biodiversity.

Special Protection Areas are areas which have been identified as being of international importance for the breeding, feeding, wintering or the migration of rare and vulnerable species of birds found within European Union countries.

Ramsar sites are wetlands of international importance, designated under the Ramsar Convention.

Wetlands are defined as areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres.

Read also- – Types of tourism: A glossary – Domestic tourism explained – What is the ‘shut-in economy’? Understanding the basics – Cultural tourism: Everything you need to know – Insta tourism: An explanation – What is globalisation? – Business tourism: What, why and where

Local Nature Reserves are for both people and wildlife. They offer people special opportunities to study or learn about nature or simply to enjoy it.

There are now more than 1400 LNRs in England. They range from windswept coastal headlands, ancient woodlands and flower-rich meadows to former inner city railways, abandoned landfill sites and industrial areas now re-colonised by wildlife. In total they cover about 35,000 ha.

This is an impressive natural resource which makes an important contribution to England’s biodiversity.

Heritage Coasts represent stretches of our most beautiful, undeveloped coastline , which are managed to conserve their natural beauty and, where appropriate, to improve accessibility for visitors.

Thirty-three per cent (1,057km) of scenic English coastline is conserved as Heritage Coasts. The first Heritage Coast to be defined was the famous white chalk cliffs of Beachy Head in Sussex and the latest is the Durham Coast. Now much of our coastline, such as the sheer cliffs of Flamborough Head and Bempton, with their huge seabird colonies, is protected as part of our coastal heritage.

European Geoparks are areas in Europe with an outstanding geological heritage. There are two in England, the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and the English Riviera in Devon.

Tourism makes up just one (important) part of the rural economy.

Rural tourism provides valuable commercial and employment opportunities for communities that are confronted with the growing challenge of offering viable livelihoods for their local populations.

Without these opportunities, people may be forced to relocate to more populous areas, often resulting in separated families and economic leakage in the local community.

Let me give you an example- In northern Thailand , many tourists choose to go on hiking tours, staying in homestays and spending their money in the rural communities. This provides local people with work opportunities that they would not otherwise be exposed to. Many women leave their home villages in Thailand to work in the sex tourism industry , where they can earn a far higher wage to support their families. But with the growth of rural tourism, many women have been able to avoid moving to the red light districts of Bangkok and Pattaya and have instead been able to make an income in the rural areas in which they live.

Moreover, rural tourism can help to disperse tourism in highly populated countries. This directs tourists away from some of the more well-known, busy areas and provides work opportunities and economic activity in alternative areas. It also helps to combat the challenge od limited carrying capacities in some destinations and the negative environmental impacts of tourism .

The rural tourism industry interlinks with a range of activity types, thus bringing economic benefit to a variety of areas. This is demonstrated in the figure below.

The roles and responsibilities of organisations involved in the management of rural tourism

Rural areas need to be managed in order to preserve its natural beauty, without limiting activities of economic benefit.

There are many organisations in which have an interest in rural areas and how they are managed and used. These include:

- National Trust

- National Association for Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (NAAONB)

- English Heritage

- Countryside Alliance

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA)

- Ramblers’ Association

The organisations involved in managing rural tourism will do things such as;

- Promote rural pursuits

- Give information

- Offer advice

- Provide revenue channels

- Legal enforcement

- Protect the environment

- Protect wildlife

- Educate people

Here is some more information about some of the major organisations that are involved with rural tourism:

Natural England is an Executive Non-departmental Public Body.

This means that although they are an independent organisation they have to report their activities and findings back to the Government (Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, DEFRA).

Their purpose is to protect and improve England’s natural environment and encourage people to enjoy and get involved in their surroundings.

They cover the whole of the England and work with people such as farmers, town and country planners, researchers and scientists, and the general public on a range of schemes and initiatives.

Their aim is to create a better natural environment that covers all of our urban, country and coastal landscapes, along with all of the animals, plants and other organisms that live with us.

Natural England is the government’s advisor on the natural environment. They provide practical advice, grounded in science, on how best to safeguard England’s natural areas for the benefit of everyone.

Their work is to ensure sustainable usage of the land and sea so that people and nature can thrive. Yet continuing to adapt and survive for future generations to enjoy.

Their responsibilities include:

- Managing England’s green farming schemes, paying nearly £400million/year to maintain two-third’s of agricultural land under agri-environment agreements

- Increasing opportunities for everyone to enjoy the wonders of the natural world

- Reducing the decline of biodiversity and licensing of protected species across England

- Designating National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty

- Managing most National Nature Reserves and notifying Sites of Special Scientific Interest

- One of Natural England’s initiatives includes Outdoors for All.

- The Outdoors for All programme began in 2008 with an action plan called Outdoors for All?

- This plan was in response to the Diversity Review which showed that some people were less likely to access the natural environment for recreation and other purposes.

- The under-represented groups were found to be disabled people, black and minority ethnic people, people who live in inner city areas and young people.

- In response Natural England are supporting other organisations in projects to get more of these under-represented groups to come to natural areas

VisitBritain is Britain’s national tourism agency, responsible for marketing Britain worldwide and developing Britain’s visitor economy.

Their mission is to build the value of tourism to Britain.

It is a non-departmental public body, funded by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, they work in partnership with thousands of organisations in the UK and overseas – the Government, the industry and other tourism bodies – to ensure that Britain is marketed in an inspirational and effective way around the world.

Their current priority is to deliver a four-year match funded global marketing programme which takes advantage of the unique opportunity of the Royal Wedding, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and the 2012 Games to showcase Britain and attract new visitors from the tourism growth markets of Asia and Latin America and to reinvigorate our appeal in core markets such as the USA, France and Germany. This campaign aims to attract four million extra visitors to Britain, who will spend an additional £2 billion.

In 2010, Deloitte published a report on their contribution to the visitor economy. As part of the findings, the report demonstrates that their activity contributes £1.1 billion to the economy and delivers £150 million directly to the Treasury each year in tax take. They also create substantial efficiency savings – £159 million last year – on the public purse.

The National Trust was founded in 1895 by three Victorian philanthropists – Miss Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley.

Concerned about the impact of uncontrolled development and industrialisation, they set up the Trust to act as a guardian for the nation in the acquisition and protection of threatened coastline, countryside and buildings.

They work to preserve and protect the buildings, countryside and coastline of England, Wales and Northern Ireland , in a range of ways, through practical conservation, learning and discovery, and encouraging everyone to visit and enjoy their national heritage.

They also educate people about the importance of the environment and of preserving heritage for future generations, they contribute to important debates over the future of the economy, the development of people’s skills and sense of community, and the quality of the local environment in both town and country.

The National Trust conducted a survey in which they found that ‘Wildlife is alien to a generation of indoor children’. They found that one in three cannot identify a magpie, one of the UK’s most common and most distinctive birds, while half couldn’t tell the difference between a bee and a wasp.

They also found that just 53% could correctly identify an oak leaf – the national tree and a powerful symbol of England, 29% failed to spot a magpie, despite the numbers soaring three-fold over the past 30 years, only 47% of children correctly identified a barn owl, one in three failed to recognise a Red Admiral; Britain’s best-known butterfly.

When asked to identify fictional creatures, however, children’s abilities suddenly soared with nine out of ten able to correctly name Doctor Who’s enemies, the Daleks, a similar number were able to identify Star Wars’ Jedi Grand Master, Yoda.

The figures are clearly a cause for concern for parents. Asked about their own knowledge of nature, 67% of parents thought they knew more about wildlife when they were youngsters than their children do now, 65% felt that this was partly due to the fact that they spent too little time with their children as a family outdoors.

The survey, carried out across both urban and rural areas across the UK, is part of a major campaign in London to encourage families to spend more time together outdoors.

The Forestry Commission is the government department responsible for the protection and expansion of Britain’s forests and woodlands.

Their mission is to protect and expand Britain’s forests and woodlands and increase their value to society and the environment.

They take the lead, on behalf of all three administrations, in the development and promotion of sustainable forest management. They deliver the distinct forestry policies of England, Scotland and Wales through specific objectives drawn from the country forestry strategies so our mission and values may be different in each.

As you know there are 15 members of the National Parks family in the UK and each one is looked after by its own National Park Authority. They all work together as the Association of National Park Authorities (ANPA).

The UK’s 15 National Parks are part of a global family of over 113,000 protected areas, covering 149 million square kilometres or 6% of the Earth’s surface. We are linked to Europe through the EUROPARC Federation – a network of European protected areas with 360 member organisations in 37 countries.

Each National Park is administered by its own National Park Authority. They are independent bodies funded by central government to:

- conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage; and

- promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of National Parks by the public.

- If there’s a conflict between these two purposes, conservation takes priority. In carrying out these aims, National Park Authorities are also required to seek to foster the economic and social well-being of local communities within the National Park.

- The Broads Authority has a third purpose, protecting the interests of navigation, and under the Broads Act 1988 all three purposes have equal priority.

- The Scottish National Parks’ objectives are to also promote the sustainable use of natural resources, the sustainable economic and social development of local communities and more of a focus on recreation.

Each National Park Authority has a number of unpaid appointed members, selected by the Secretary of State, local councils and parish councils. The role of members is to provide leadership, scrutiny and direction for the National Park Authority.

There are also a number of paid staff who carry out the work necessary to run the National Park.

UK ANPA brings together the 15 National Park Authorities in the UK to raise the profile of the National Parks and to promote joint working. Country associations for the English and Welsh National Parks represent the National Park Authorities to English and Welsh governments.

Positive impacts of rural tourism

Rural tourism has many positive economic, social and environmental impacts if it is managed well and adheres to sustainable tourism principles. I have outlined some of the most commonly noted benefits of rural tourism below:

Employment generation is a common positive economic impact impact of tourism .

Rural tourism can create many jobs in areas where they may otherwise not be many employment opportunities.

These jobs may be directly related to the rural tourism industry, for example hotel workers or taxi drivers.

They may also be indirected related to the rural tourism industry, such as builders (who build the hotels) or staff employed to maintain and keep the area clean.

If more people are employed, there is more opportunity for wider economics benefits. This is because employees will likely pay taxes on their income.

Each destination has its own methods of taxation. But one thing that we can be fairly certain about, is that there will be some money made through taxes on tourism products and services.

The money raised through taxes can then be reinvested into other areas, such as healthcare or education. Tourism therefore has the potential to provide a far-reaching positive economic impact.

Rural tourism enables local people to set up and operate businesses. Rural areas often have less of the known chains and brands (think Costa Coffee, Hilton Hotel etc) and more independent organisations.

Businesses that are owned and managed locally are great because it enables much of the income raised from tourism to stay local and prevents economic leakage in tourism .

Rural tourism will often require the development of new infrastructure and facilities.

This is particular prevalent when it comes to transport networks. Inherently, rural areas are not well connected by public transport. Roads are often narrow and windy, meaning that traffic build up is common, particularly during peak times.

Rural tourism often results in the construction of new transport networks and infrastructure, among other public facilities and services. This is beneficial not only to the tourists who travel here, but also to the local community.

Rural tourism encourages cultural tourism and cultural exchange.

Many people from a range of destinations will travel to rural areas for tourism. This provides opportunities for locals and tourists to get to know each other and to learn more about each other’s cultures.

There are many positive social impacts of tourism . One impact is that rural areas are encouraged to share their traditions and customs with the people who are coming to visit the area.

This encourages the revitalisation and preservation of traditions, customs and crafts.

Because rural tourism usually relies on the environment that is being visited, there are often schemes put in place to protect and conserve areas.

This includes giving an area natural park status or declaring it an area of outstanding natural beauty, for example.

It also includes implementing management processes, such as reducing visitor numbers or condoning off particular areas.

Negative impacts of rural tourism

Whilst rural tourism does have many advantages, there are also disadvantages that must be taken into account. Here are some of the most common examples:

Tourism is often seasonal and comes in peaks and troughs. In the UK, for example, countryside areas are busier on weekends than on weekdays and there are more tourists during the school holidays than there are during term time.

This can place lots of pressure on public services. Hospitals may be overwhelmed during the summer months, when hotel occupancy rates are at their highest. Roads may be gridlocked on bank holiday weekends as city-livers flee to the countryside for some fresh air.

The presence of tourism can result in increases in land and housing prices. This can have a negative effect on the local population.

Some people may feel that they need to relocate because they can no longer afford to live in the area, known as gentrification.

Other people may have a lower quality of life (i.e. have a smaller home, less disposable income) than they would have had if there was no tourism.

As I mentioned before, rural tourism can be subject to overcrowding and congestion. This is particularly prevalent during peak times such as Christmas, the summer holidays and weekends.

Another concern of rural tourism is that there may be too much development in an area. This can impact the appeal of a destination to both tourists and locals.

Some development may not be in keeping with the traditions of the area. If a new theme park is built (because they are often in rural areas), for example, this would likely completely change the area. It would bring with it a different type of tourist and the associated developments (hotels, food outlets etc).

Rural tourism management techniques

In order to maximise the positive impacts of rural tourism and minimise the negative impacts, it is imperative that appropriate management techniques are adopted. Below I have outlined that practices that are seen throughout the world:

Unfortunately, many rural tourism areas are not accessible to all. Enabling wide-scale access is an important part of ensuring that tourism is fair and sustainable.

The equality Act 2010 states that ‘Tourism providers should treat everyone accessing their goods, facilities or services fairly, regardless of their age, gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, gender reassignment, religion or belief, and guard against making assumptions about the characteristics of individuals.’

Here are some great examples of accessibility in rural tourism: – New Forest Access for All – Peak District access for All – Parsley Hay cycle centre

As I mentioned earlier, a lack of transport links to gain access to the destination is a common problem in the rural tourism industry. Organisations can work with local and regional governments to improve local infrastructure. They can also organise their own transport options, such as buses or tours.

In some cases, restrictions to access are necessary in order to ensure that areas are preserved. This is the case, for example, at Stone Henge, where the area is roped-off to prevent tourists from touching the stones.

Similarly, many areas will ask tourists to stick to designated paths or walkways, to prevent damage to the natural environment.

In order to encourage sustainable tourism development , many organisations will invest in training programmes and schemes to up-skill members of the local community.

This is common amongst hotels, facilities and attractions should employ people from the local community.

Training helps to ensure that organisations have more satisfied staff, who are more likely to stay in the position. This keeps costs and turnover of staff down for the company. Happy staff are also likely to work harder and be more productive in their job, which in turn helps the organisation and the overall economy to yield greater economic outcomes.

Example: LandSkills East offer a Bursary to suitably qualified and experienced applicants to help meet the cost of higher level training in management, business and leadership skills. Applicants should be interested in developing their skills in order to steer the future of the land based and rural sector in the East of England and the rest of the UK. Bursary funding covers 50% of the cost of the training activity. This can be from £500 to a maximum of £3000 pounds. This could be to attend conferences, workshops, work placements, research, formal training or post-graduate level qualifications in areas related to the industry. The following industries are eligible for bursary funding: -Agriculture and Livestock -Arable and non Food Crops -Food and Production Horticulture -Viticulture -Environmental Conservation -Food Diversification and Supply Chain -Rural Crafts e.g. timber framing, thatching -Land-based Research and Development

Community-based tourism is often found in rural areas. This is because there is often a close-knit community.

Community tourism fosters the growth of locally owned and managed businesses. It also encourages businesses that are directly involved in the tourism industry (i.e. a hotel) to work with other local businesses (i.e. a local farmer).

Partnerships between local business helps to maximise the economic advantages of rural tourism and minimise economic leakage in tourism .

Areas will have traditional artefacts that demonstrate their history, culture and traditions. These could be from, for example, the Celtic, Romans & religious era’s.

Many of these will be protected or put into museums i.e. The Chiltern Open Air Museum , based in the AONB – The Chilterns.

Places that facilitate the promotion of traditional artefacts such as this are often given charitable status. This means that they can obtain money from sponsorship, funding and membership.

As I have mentioned several times throughout this article, public transport infrastructure is often one of the downsides of rural tourism. Therefore, rural tourism destinations can try to implement various strategies and developments in attempt to improve this.

One such technique is the Green Travel Plan. This is an effective Travel Plan helps to reduce pressure on the local infrastructure, contributes to keeping local pollution to a minimum and enables the widest range of people to have good access to work and services.

Areas can also try to encourage sustainable travel.

Sustainable travel is any form of transport that keeps damage to our environment to a minimum and normally has the added advantage of being a healthier alternative for the user.

Methods of sustainable transport include: walking, cycling, public transport and car sharing, or using vehicles that minimise carbon emissions and other pollutants, such as electric and hybrid cars, and cars which run on cleaner fuels such as LPG.

Some destinations will implement traffic management schemes in order to make their tourism sector more sustainable.

This could be in the form of encouraging destinations to have visitor travel plans in place and to work with businesses and accommodation providers to promote things to enjoy that require reduced travel.

Destinations and public transport operators may aim to develop ‘hubs’ from which there is a concentration of car free options with car parking (e.g. walks, cycle hire, bus and rail services). This would integrate with public transport, accommodation and other visitor experiences.

Others may identify and share best practice in rural public transport that meets the needs of visitors and communities e.g. Smart ticketing; electric bikes; car clubs.

A completely car free rural area and low carbon initiatives will be difficult to implement. This means accepting that some car use is necessary for rural tourism but encouraging more initiatives that increase dwell times at destinations, reduce mileage and length of car journey, such as walks and itineraries that are integrated with public transport and visitor experiences.

It is also important to encourage sustainable transport options when visitors arrive at their destination, for example, encouraging accommodation to link to cycle hire firms, cycle racks, and cycle friendly venues for visitors to bring their own bikes.

There are various sites and properties that are protected against demolition and further building but must be preserved and repaired where necessary.

Footpaths are included in the conservation projects and many destinations have developed footpath networks in attempt to protect the larger area from tramping, littering etc.

Example- Today the Lake District attracts over 12 million visitors per year. This large number of visitors puts the environment under great pressure. It has been estimated that over 10 million people use the National Park’s paths annually. Many Lake District paths have become huge open scars, visible from miles away. Eroded paths are not only unsightly, but unpleasant to walk on and can lead to habitat loss as well as damage to the heritage, archaeological and natural history qualities of the area.

Repairing eroded paths is not the statutory duty of the Highway Authority, or anyone else, as long as they are still ‘open and fit for use’. The National Trust, the LDNPA and English Nature have worked together since the late 1970s to manage the problem.

In 1993 they formed the Lake District Upland Access Management Group (AMG). Their aim was to complete a detailed survey of eroded paths in theLake District. The initial surveys, which focused in particular on the popular central fells, identified 145 paths which were in need of repair.

By 1999, the whole of the National Park had been surveyed and 180 paths had been identified as being in need of repair. The huge scale of the problem highlighted the need for a long term management solution.

This led to the formation of the Upland Path Landscape Restoration Project (UPLRP) a 10 year project (2002 to 2011) which sets out to repair the majority of landscape scars caused by the erosion of fells paths in the Lake District.

This technique involves digging stone into the ground to form good solid footfalls. This ancient technique is used extensively in the central fells using stone which is naturally occurring.

There are many different rural tourism activities that people can take part in and many reasons that a person may be motivated to be a rural tourist.

Motivational reasons may include:

Many people choose to undertake rural tourism because they enjoy traditional pursuits. These may include:

There are also a number of modern pursuits that are packaged and sold as part of a rural tourism holiday. These include:

- Mountain biking

- Quad biking

- Water sports

- Team-building

There are also many special interest holidays that take place in rural areas, such as:

- Heritage tours/activities

- Wildlife spotting/visiting/petting

- Sightseeing

- Canal cruising

- Photography

- Horser riding

- Pony trekking

- Winter sports

Lastly, rural tourism can be the perfect ground for educational opportunities, which may include:

- Geography field trips

- Team building

Rural tourism destinations

In recent years I have taken part in rural tourism activities in a number of countries around the world . Here are some of my favourites:

One of my favourite rural travel destinations is Meteora in Greece.

Meteora is an area of Greece that features extraordinary rock formations. The area is abundant with slender stone pinnacles. Many of these pinnacles house ancient Byzantine monasteries on top.

The area is simply magical! And I’m not the only one who thinks so… this part of Greece has been the setting for a number of films, including one of my favourites- Avatar.

Canada offers the perfect rural tourism holidays!

We did a road trip through the Rockies a couple of years back and absolutely LOVED it! There is so much to do and the scenery is just spectacular.

You can read all about our trip to Canada with a baby here.

Rural tourism is very popular in Sri Lanka.

The main area of appeal are the tea plantations. These areas are rich with history and offer a number of tours where tourists can learn about the history, culture and physical production of tea.

This made for a great addition to our Sri Lanka with a baby itinerary.

Rural tourism in Australia is very popular.

Some people choose to visit the mountain or countryside areas for recreation. Others commit to volunteer tourism projects or undertake working holidays. WWOOFING is also very popular in Australia.

Many people choose to visit the ‘outback’, which offers many rural tourism opportunities. Australia is a popular destination for road trips and it is common for tourists to drive around the country using camper vans or other road transport.

It is evident that rural tourism deserves a place in the tourism industry!

Rural tourism is popular the world over and has the potential to have significant economic impacts in rural areas. As I have explained, careful management is important in order to ensure that the positive impacts are maximised and the negative impacts are minimised- there are a number of different stakeholders that play a role in this.

The rural tourism industry has significant value to the tourism industries and economies of countries around the world. If you would like to learn more about rural tourism, I have suggested some texts below.

- Rural Tourism -This book describes, analyses, celebrates and interrogates the rise of rural tourism in the developed world over the last thirty years, while explaining its need to enter a new, second generation of development if it is to remain sustainable in all senses of that word.

- Rural Tourism and Enterprise: Management, Marketing and Sustainability – This textbook examines key issues affecting rural enterprise and tourism.

- Rural Tourism: An International Perspective – This edited collection questions the contribution tourism can and does make to rural regions.

- Rural Tourism: An Introduction – This text provides a comprehensive, stimulating and up-to-date analysis of the key issues involved in the planning and management of rural tourism.

- Rural Tourism and Recreation: Principles to Practice – This book reviews both the theory and practice of rural tourism and recreation.

- Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business – This book provides the latest conceptual thinking on, and case study exemplification of, rural tourism and sustainable business development from Europe, North America, Australasia, the Middle East and Japan.

- Rural Tourism Development: Localism and Cultural Change – This book links changes at the local, rural community level to broader, more structural considerations of globalization and allows for a deeper, more theoretically sophisticated consideration of the various forces and features of rural tourism development.

Liked this article? Click to share!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 31 March 2023

The benefits of tourism for rural community development

- Yung-Lun Liu 1 ,

- Jui-Te Chiang 2 &

- Pen-Fa Ko 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 137 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Development studies

While the main benefits of rural tourism have been studied extensively, most of these studies have focused on the development of sustainable rural tourism. The role of tourism contributions to rural community development remains unexplored. Little is known about what tourism contribution dimensions are available for policy-makers and how these dimensions affect rural tourism contributions. Without a clear picture and indication of what benefits rural tourism can provide for rural communities, policy-makers might not invest limited resources in such projects. The objectives of this study are threefold. First, we outline a rural tourism contribution model that policy-makers can use to support tourism-based rural community development. Second, we address several methodological limitations that undermine current sustainability model development and recommend feasible methodological solutions. Third, we propose a six-step theoretical procedure as a guideline for constructing a valid contribution model. We find four primary attributes of rural tourism contributions to rural community development; economic, sociocultural, environmental, and leisure and educational, and 32 subattributes. Ultimately, we confirm that economic benefits are the most significant contribution. Our findings have several practical and methodological implications and could be used as policy-making guidelines for rural community development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Creativity development of tourism villages in Bandung Regency, Indonesia: co-creating sustainability and urban resilience

Rd Ahmad Buchari, Abdillah Abdillah, … Heru Nurasa

Eco-tourism, climate change, and environmental policies: empirical evidence from developing economies

Yunfeng Shang, Chunyu Bi, … Ehsan Rasoulinezhad

Knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory and its applicability in tourism research

Jinyu Pan & Zhenzhi Yang

Introduction

In many countries, rural areas are less developed than urban areas. They are often perceived as having many problems, such as low productivity, low education, and low income. Other issues include population shifts from rural to urban areas, low economic growth, declining employment opportunities, the loss of farms, impacts on historical and cultural heritage, sharp demographic changes, and low quality of life. These issues indicate that maintaining agricultural activities without change might create deeper social problems in rural regions. Li et al. ( 2019 ) analyzed why some rural areas decline while others do not. They emphasized that it is necessary to improve rural communities’ resilience by developing new tourism activities in response to potential urban demands. In addition, to overcome the inevitability of rural decline, Markey et al. ( 2008 ) pointed out that reversing rural recession requires investment orientation and policy support reform, for example, regarding tourism. Therefore, adopting rural tourism as an alternative development approach has become a preferred strategy in efforts to balance economic, social, cultural, and environmental regeneration.

Why should rural regions devote themselves to tourism-based development? What benefits can rural tourism bring to a rural community, particularly during and after the COVID pandemic? Without a clear picture and answers to these questions, policy-makers might not invest limited resources in such projects. Understanding the contributions of rural tourism to rural community development is critical for helping government and community planners realize whether rural tourism development is beneficial. Policy-makers are aware that reducing rural vulnerability and enhancing rural resilience is a necessary but challenging task; therefore, it is important to consider the equilibrium between rural development and potential negative impacts. For example, economic growth may improve the quality of life and enhance the well-being index. However, it may worsen income inequality, increase the demand for green landscapes, and intensify environmental pollution, and these changes may impede natural preservation in rural regions and make local residents’ lives more stressful. This might lead policy-makers to question whether they should support tourism-based rural development. Thus, the provision of specific information on the contributions of rural tourism is crucial for policy-makers.

Recently, most research has focused on rural sustainable tourism development (Asmelash and Kumar, 2019 ; Polukhina et al., 2021 ), and few studies have considered the contributions of rural tourism. Sustainability refers to the ability of a destination to maintain production over time in the face of long-term constraints and pressures (Altieri et al., 2018 ). In this study, we focus on rural tourism contributions, meaning what rural tourism contributes or does to help produce something or make it better or more successful. More specifically, we focus on rural tourism’s contributions, not its sustainability, as these goals and directions differ. Today, rural tourism has responded to the new demand trends of short-term tourists, directly providing visitors with unique services and opportunities to contact other business channels. The impact on the countryside is multifaceted, but many potential factors have not been explored (Arroyo et al., 2013 ; Tew and Barbieri, 2012 ). For example, the demand for remote nature-based destinations has increased due to the fear of COVID-19 infection, the perceived risk of crowding, and a desire for low tourist density. Juschten and Hössinger ( 2020 ) showed that the impact of COVID-19 led to a surge in demand for natural parks, forests, and rural areas. Vaishar and Šťastná ( 2022 ) demonstrated that the countryside is gaining more domestic tourists due to natural, gastronomic, and local attractions. Thus, they contended that the COVID-19 pandemic created rural tourism opportunities.

Following this change in tourism demand, rural regions are no longer associated merely with agricultural commodity production. Instead, they are seen as fruitful locations for stimulating new socioeconomic activities and mitigating public mental health issues (Kabadayi et al., 2020 ). Despite such new opportunities in rural areas, there is still a lack of research that provides policy-makers with information about tourism development in rural communities (Petrovi’c et al., 2018 ; Vaishar and Šťastná, 2022 ). Although there are many novel benefits that tourism can bring to rural communities, these have not been considered in the rural community development literature. For example, Ram et al. ( 2022 ) showed that the presence of people with mental health issues, such as nonclinical depression, is negatively correlated with domestic tourism, such as rural tourism. Yang et al. ( 2021 ) found that the contribution of rural tourism to employment is significant; they indicated that the proportion of nonagricultural jobs had increased by 99.57%, and tourism in rural communities had become the leading industry at their research site in China, with a value ten times higher than that of agricultural output. Therefore, rural tourism is vital in counteracting public mental health issues and can potentially advance regional resilience, identity, and well-being (López-Sanz et al., 2021 ).

Since the government plays a critical role in rural tourism development, providing valuable insights, perspectives, and recommendations to policy-makers to foster sustainable policies and practices in rural destinations is essential (Liu et al., 2020 ). Despite the variables developed over time to address particular aspects of rural tourism development, there is still a lack of specific variables and an overall measurement framework for understanding the contributions of rural tourism. Therefore, more evidence is needed to understand how rural tourism influences rural communities from various structural perspectives and to prompt policy-makers to accept rural tourism as an effective development policy or strategy for rural community development. In this paper, we aim to fill this gap.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: the section “Literature review” presents the literature review. Our methodology is described in the section “Methodology”, and our results are presented in the section “Results”. Our discussion in the section “Discussion/implications” places our findings in perspective by describing their theoretical and practical implications, and we provide concluding remarks in the section “Conclusion”.

Literature review

The role of rural tourism.

The UNWTO ( 2021 ) defined rural tourism as a type of tourism in which a visitor’s experience is related to a wide range of products generally linked to nature-based activity, agriculture, rural lifestyle/culture, angling, and sightseeing. Rural tourism has been used as a valid developmental strategy in rural areas in many developed and developing countries. This developmental strategy aims to enable a rural community to grow while preserving its traditional culture (Kaptan et al., 2020 ). In rural areas, ongoing encounters and interactions between humans and nature occur, as well as mutual transformations. These phenomena take place across a wide range of practices that are spatially and temporally bound, including agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, farm tourism, cultural heritage preservation, and country life (Hegarty and Przezbórska, 2005 ). To date, rural tourism in many places has become an important new element of the regional rural economy; it is increasing in importance as both a strategic sector and a way to boost the development of rural regions (Polukhina et al., 2021 ). Urban visitors’ demand for short-term leisure activities has increased because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Slater, 2020 ). Furthermore, as tourists shifted their preferences from exotic to local rural tourism amid COVID-19, Marques et al. ( 2022 ) suggested that this trend is a new opportunity that should be seized, as rural development no longer relies on agriculture alone. Instead, other practices, such as rural tourism, have become opportunities for rural areas. Ironically, urbanization has both caused severe problems in rural areas and stimulated rural tourism development as an alternative means of economic revitalization (Lewis and Delisle, 2004 ). Rural tourism provides many unique events and activities that people who live in urban areas are interested in, such as agricultural festivals, crafts, historical buildings, natural preservation, nostalgia, cuisine, and opportunities for family togetherness and relaxation (Christou, 2020 ; Getz, 2008 ). As rural tourism provides visitors from urban areas with various kinds of psychological, educational, social, esthetic, and physical satisfaction, it has brought unprecedented numbers of tourists to rural communities, stimulated economic growth, improved the viability of these communities, and enhanced their living standards (Nicholson and Pearce, 2001 ). For example, rural tourism practitioners have obtained significant economic effects, including more income, more direct sales, better profit margins, and more opportunities to sell agricultural products or craft items (Everett and Slocum, 2013 ). Local residents can participate in the development of rural tourism, and it does not necessarily depend on external resources. Hence, it provides entrepreneurial opportunities (Lee et al., 2006 ). From an environmental perspective, rural tourism is rooted in a contemporary theoretical shift from cherishing local agricultural resources to restoring the balance between people and ecosystems. Thus, rural land is preserved, natural landscapes are maintained, and green consumerism drives farmers to focus on organic products, green chemistry, and value-added products, such as land ethics (Higham and Ritchie, 2001 ). Therefore, the potential contributions of rural tourism are significant and profound (Marques, 2006 ; Phillip et al., 2010 ). Understanding its contributions to rural community development could encourage greater policy-maker investment and resident support (Yang et al., 2010 ).

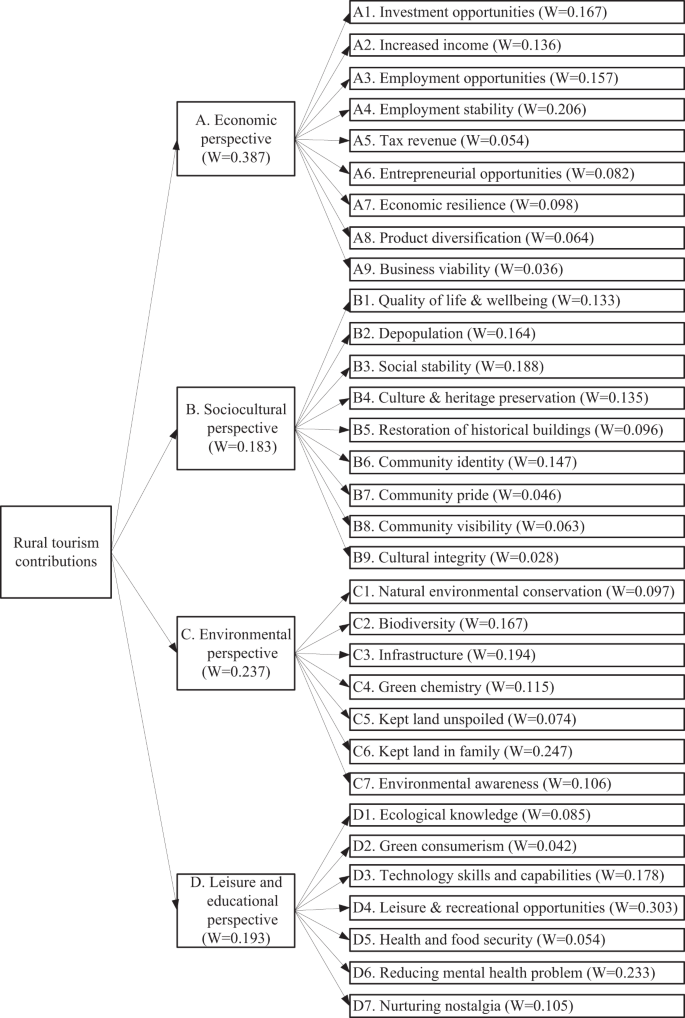

Contributions of rural tourism to rural community development

Maintaining active local communities while preventing the depopulation and degradation of rural areas requires a holistic approach and processes that support sustainability. What can rural tourism contribute to rural development? In the literature, rural tourism has been shown to bring benefits such as stimulating economic growth (Oh, 2005 ), strengthening rural and regional economies (Lankford, 1994 ), alleviating poverty (Zhao et al., 2007 ), and improving living standards in local communities (Uysal et al., 2016 ). In addition to these economic contributions, what other elements have not been identified and discussed (Su et al., 2020 )? To answer these questions, additional evidence is a prerequisite. Thus, this study examines the following four aspects. (1) The economic perspective: The clustering of activities offered by rural tourism stimulates cooperation and partnerships between local communities and serves as a vehicle for creating various economic benefits. For example, rural tourism improves employment opportunities and stability, local residents’ income, investment, entrepreneurial opportunities, agricultural production value-added, capital formation, economic resilience, business viability, and local tax revenue (Atun et al., 2019 ; Cheng and Zhang, 2020 ; Choi and Sirakaya, 2006 ; Chong and Balasingam, 2019 ; Cunha et al., 2020 ). (2) The sociocultural perspective: Rural tourism no longer refers solely to the benefits of agricultural production; through economic improvement, it represents a greater diversity of activities. It is important to take advantage of the novel social and cultural alternatives offered by rural tourism, which contribute to the countryside. For example, rural tourism can be a vehicle for introducing farmers to potential new markets through more interactions with consumers and other value chain members. Under such circumstances, the sociocultural benefits of rural tourism are multifaceted. These include improved rural area depopulation prevention (López-Sanz et al., 2021 ), cultural and heritage preservation, and enhanced social stability compared to farms that do not engage in the tourism business (Ma et al., 2021 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). Additional benefits are improved quality of life; revitalization of local crafts, customs, and cultures; restoration of historical buildings and community identities; and increased opportunities for social contact and exchange, which enhance community visibility, pride, and cultural integrity (Kelliher et al., 2018 ; López-Sanz et al., 2021 ; Ryu et al., 2020 ; Silva and Leal, 2015 ). (3) The environmental perspective: Many farms in rural areas have been rendered noncompetitive due to a shortage of labor, poor managerial skills, and a lack of financial support (Coria and Calfucura, 2012 ). Although there can be immense pressure to maintain a farm in a family and to continue using land for agriculture, these problems could cause families to sell or abandon their farms or lands (Tew and Barbieri, 2012 ). In addition, unless new income pours into rural areas, farm owners cannot preserve their land and its natural aspects; thus, they tend to allow their land to become derelict or sell it. In the improved economic conditions after farms diversify into rural tourism, rural communities have more money to provide environmental care for their natural scenic areas, pastoral resources, forests, wetlands, biodiversity, pesticide mitigation, and unique landscapes (Theodori, 2001 ; Vail and Hultkrantz, 2000 ). Ultimately, the entire image of a rural community is affected; the community is imbued with vitality, and farms that participate in rural tourism instill more togetherness among families and rural communities. In this study, the environmental benefits induced by rural tourism led to improved natural environmental conservation, biodiversity, environmental awareness, infrastructure, green chemistry, unspoiled land, and family land (Di and Laura, 2021 ; Lane, 1994 ; Ryu et al., 2020 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). (4) The leisure and educational perspective: Rural tourism is a diverse strategy associated with an ongoing flow of development models that commercialize a wide range of farming practices for residents and visitors. Rural territories often present a rich set of unique resources that, if well managed, allow multiple appealing, authentic, and memorable tourist experiences. Tourists frequently comment that the rural tourism experience positively contrasts with the stress and other negatively perceived conditions of daily urban life. This is reflected in opposing, compelling images of home and a visited rural destination (Kastenholz et al., 2012 ). In other words, tourists’ positive experiences result from the attractions and activities of rural tourism destinations that may be deemed sensorially, symbolically, or socially opposed to urban life (Kastenholz et al. 2018 ). These experiences are associated with the “search for authenticity” in the context of the tension between the nostalgic images of an idealized past and the demands of stressful modern times. Although visitors search for the psychological fulfillment of hedonic, self-actualization, challenge, accomplishment, exploration, and discovery goals, some authors have uncovered the effects of rural tourism in a different context. For example, Otto and Ritchie ( 1996 ) revealed that the quality of a rural tourism service provides a tourist experience in four dimensions—hedonic, peace of mind, involvement, and recognition. Quadri-Felitti and Fiore ( 2013 ) identified the relevant impact of education, particularly esthetics, versus memory on satisfaction in wine tourism. At present, an increasing number of people and families are seeking esthetic places for relaxation and family reunions, particularly amid COVID-19. Rural tourism possesses such functions; it remains a novel phenomenon for visitors who live in urban areas and provides leisure and educational benefits when visitors to a rural site contemplate the landscape or participate in an agricultural process for leisure purposes (WTO, 2020 ). Tourists can obtain leisure and educational benefits, including ecological knowledge, information about green consumerism, leisure and recreational opportunities, health and food security, reduced mental health issues, and nostalgia nurturing (Alford and Jones, 2020 ; Ambelu et al., 2018 ; Christou, 2020 ; Lane, 1994 ; Li et al., 2021 ). These four perspectives possess a potential synergy, and their effects could strengthen the relationship between rural families and rural areas and stimulate new regional resilience. Therefore, rural tourism should be understood as an enabler of rural community development that will eventually attract policy-makers and stakeholders to invest more money in developing or advancing it.

Methodology

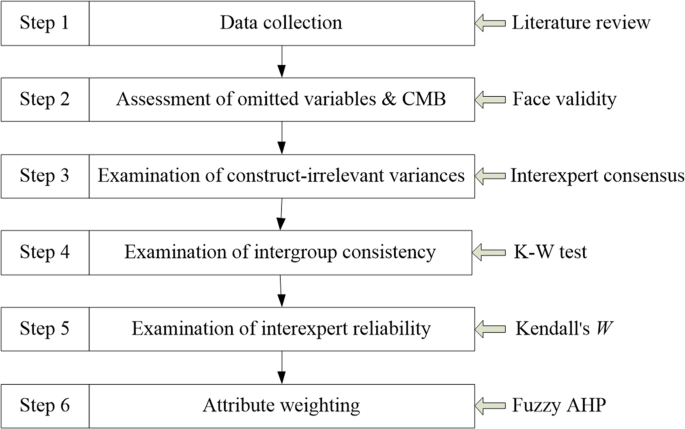

The literature on rural tourism provides no generally accepted method for measuring its contributions or sustainability intensity. Although many statistical methods are available, several limitations remain, particularly in terms of the item generation stage and common method bias (CMB). For example, Marzo-Navar et al. ( 2015 ) used the mean and SD values to obtain their items. However, the use of the mean has been criticized because it is susceptible to extreme values or outliers. In addition, they did not examine omitted variables and CMB. Asmelash and Kumar ( 2019 ) used the Delphi method with a mean value for deleting items. Although they asked experts to suggest the inclusion of any missed variables, they did not discuss these results. Moreover, they did not assess CMB. Islam et al. ( 2021 ) used a sixteen-step process to formulate sustainability indicators but did not consider omitted variables, a source of endogeneity bias. They also did not designate a priority for each indicator. Although a methodologically sound systematic review is commonly used, little attention has been given to reporting interexpert reliability when multiple experts are used to making decisions at various points in the screening and data extraction stages (Belur et al., 2021 ). Due to the limitations of the current methods for assessing sustainable tourism development, we aim to provide new methodological insights. Specifically, we suggest a six-stage procedure, as shown in Fig. 1 .

Steps required in developing the model for analysis after obtaining the data.

Many sources of data collection can be used, including literature reviews, inferences about the theoretical definition of the construct, previous theoretical and empirical research on the focal construct, advice from experts in the field, interviews, and focus groups. In this study, the first step was to retrieve data from a critical literature review. The second step was the assessment of omitted variables to produce items that fully captured all essential aspects of the focal construct domain. In this case, researchers must not omit a necessary measure or fail to include all of the critical dimensions of the construct. In addition, the stimuli of CMB, for example, double-barreled items, items containing ambiguous or unfamiliar terms, and items with a complicated syntax, should be simplified and made specific and concise. That is, researchers should delete items contaminated by CMB. The third step was the examination of construct-irrelevant variance to retain the variances relevant to the construct of interest and minimize the extent to which the items tapped concepts outside the focal construct domain. Variances irrelevant to the targeted construct should be deleted. The fourth step was to examine intergroup consistency to ensure that there was no outlier impact underlying the ratings. The fifth step was to examine interexpert reliability to ensure rating conformity. Finally, we prioritized the importance of each variable with the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (AHP), which is a multicriteria decision-making approach. All methods used in this study are expert-based approaches.

Selection of experts