- Find in topic

INTRODUCTION

The treatment and prevention of travelers' diarrhea are discussed here. The epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of travelers' diarrhea are discussed separately. (See "Travelers' diarrhea: Epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis" .)

Clinical approach — Management of travelers’ diarrhea depends on the severity of illness. Fluid replacement is an essential component of treatment for all cases of travelers’ diarrhea. Most cases are self-limited and resolve on their own within three to five days of treatment with fluid replacement only. Antimotility agents can provide symptomatic relief but should not be used when bloody diarrhea is present. Antimicrobial therapy shortens the disease duration, but the benefit of antibiotics must be weighed against potential risks, including adverse effects and selection for resistant bacteria. These issues are discussed in the sections that follow.

When to seek care — Travelers from resource-rich settings who develop diarrhea while traveling to resource-limited settings generally can treat themselves rather than seek medical advice while traveling. However, medical evaluation may be warranted in patients who develop high fever, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, or vomiting. Otherwise, for most patients while traveling or after returning home, medical consultation is generally not warranted unless symptoms persist for 10 to 14 days.

Fluid replacement — The primary and most important treatment of travelers' (or any other) diarrhea is fluid replacement, since the most significant complication of diarrhea is volume depletion [ 11,12 ]. The approach to fluid replacement depends on the severity of the diarrhea and volume depletion. Travelers can use the amount of urine passed as a general guide to their level of volume depletion. If they are urinating regularly, even if the color is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely mild. If there is a paucity of urine and that small amount is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely more severe.

To continue reading this article, you must sign in . For more information or to purchase a personal subscription, click below on the option that best describes you:

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

Print Options

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Section 2 - Travelers’ Diarrhea

- Section 2 - Food & Water Precautions

Perspectives : Antibiotics in Travelers' Diarrhea - Balancing Benefit & Risk

Cdc yellow book 2024.

Author(s): Mark Riddle, Bradley Connor

For the past 30 years, randomized controlled trials have consistently and clearly demonstrated that antibiotics shorten the duration of illness and alleviate the disability associated with travelers’ diarrhea (TD). Treatment with an effective antibiotic shortens the average duration of a TD episode by 1–2 days, and if the traveler combines an antibiotic with an antimotility agent (e.g., loperamide), duration of illness is shortened even further. Emerging data on the potential long-term health consequences of TD (e.g., chronic constipation, dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome) might suggest a benefit of early antibiotic therapy given the association between more severe and longer disease and risk for postinfectious consequences.

Antibiotics commonly used to treat TD have side effects, some of which are severe but rare. Perhaps of greater concern is the recent understanding that antibiotics used by travelers can contribute to changes in the host microbiome and to the acquisition of multidrug-resistant bacteria. Multiple observational studies have found that travelers (in particular, travelers to South and Southeast Asia) who develop TD and take antibiotics are at risk for colonization with extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE).

The direct effect of colonization on the average traveler appears limited; carriage is most often transient, but it does persist in a small percentage of colonized persons. Elderly travelers (because of the serious consequences of bloodstream infections in this population) and those with a history of recurrent urinary tract infections (because Escherichia coli is a common cause) might be at an increased risk for health consequences from ESBL-PE colonization. At a minimum, clinicians should make these travelers aware of the risk and counsel them to convey their travel exposure history to their treating providers if they become ill after travel. Of broader importance, international travel has been associated with subsequent ESBL-PE colonization among close-living contacts, suggesting potentially wider public health consequences from ESBL-PE acquisition during travel.

The Challenge

The challenge providers and travelers face is how to balance the health benefit of short-course antibiotic treatment of TD with the risk for colonization and global spread of resistance. The role played by travelers in the translocation of infectious disease and resistance cannot be ignored, but the ecology of ESBL-PE infections is complex and includes diet, environment, immigration, and local nosocomial transmission dynamics. ESBL-PE infections are an emerging health threat, and addressing this complex problem will require multiple strategies, including antibiotic stewardship.

An Approach

Health care providers need to have conversations with travelers about the multilevel (individual, community, global) and multifactorial risks of developing TD: travel, individual behaviors (e.g., hand hygiene), diet (e.g., safe selection of foods and beverages), and other risk avoidance measures. But then, knowing it is often difficult to prevent or even reduce the risk for TD through behaviors and diet alone, what is the most reasonable way to prepare travelers for empiric TD self-treatment before a trip? Clinicians can strongly emphasize reserving antibiotics for moderate to severe TD and using antimotility agents for self-treatment of mild TD.

When it comes to managing TD, we expect the traveler to be both diagnostician and health care provider. For even the most astute traveler, making an appropriately informed decision about their own health can be challenged by the anxiety-provoking onset of that first abdominal cramp in sometimes austere and inconvenient settings. Given that TD counseling is competing with numerous other pretravel health topics that need to be covered, travel medicine providers might want to develop and implement simple messaging, handouts, or easy-to-access electronic health guidance. Providing travelers with clear written guidance about TD prevention and step-by-step instructions about how and when to use medications for TD is crucial.

Though further studies are needed (and many are under way), a rational approach involves using a single-dose regimen of an antibiotic that minimizes microbiome disruption and risk for colonization. Additionally, as travel and untreated TD independently increase the risk for ESBL-PE colonization, nonantibiotic chemoprophylactic strategies (e.g., self-treatment with bismuth subsalicylate), can decrease both the acute and posttravel risk concerns. Strengthening the resilience of the host microbiota to prevent infection and unwanted colonization, as with the use of prebiotics or probiotics, are promising potential strategies but need further investigation.

The following authors contributed to the previous version of this chapter: Mark S. Riddle, Bradley A. Connor

Bibliography

Arcilla MS, van Hattem JM, Haverkate MR, Bootsma MCJ, van Genderen PJJ, Goorhuis A, et al. Import and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by international travellers (COMBAT study): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):78–85.

Riddle MS, Connor BA, Beeching NJ, DuPont HL, Hamer DH, Kozarsky P, et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: a graded expert panel report. J Travel Med. 2017;24 (Suppl 1):S57–74.

. . . perspectives chapters supplement the clinical guidance in this book with additional content, context, and expert opinion. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

Traveler’s Diarrhea

, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

More Information

Traveler’s diarrhea is an infection characterized by diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting that commonly occur in travelers to areas of the world with poor water purification.

Traveler's diarrhea can be caused by bacteria, parasites, or viruses.

Organisms that cause the disorder are usually acquired from food or water, especially in countries where the water supply may be inadequately treated.

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea can occur with any degree of severity.

The diagnosis is usually based on the doctor's evaluation, but sometimes stool is tested for organisms.

Treatment involves drinking plenty of safe fluids and sometimes taking antidiarrheal medications or antibiotics.

Preventive measures include drinking only bottled carbonated beverages, avoiding uncooked vegetables or fruits, not using ice cubes, and using bottled water to brush teeth.

Traveler’s diarrhea occurs when people are exposed to bacteria, viruses, or, less commonly, parasites to which they have had little exposure and thus no immunity. The organisms are usually acquired from food or water (including water used to wash foods).

Traveler’s diarrhea occurs mostly in countries where the water supply is inadequately treated.

Travelers who avoid drinking local water may still become infected by brushing their teeth with an improperly rinsed toothbrush, drinking bottled drinks with ice made from local water, or eating food that is improperly handled or washed with local water. People who take medications that decrease stomach acid (such as antacids, H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors) are at risk of developing a more severe illness.

Symptoms of Traveler’s Diarrhea

The following symptoms of traveler's diarrhea can occur in any combination and with any degree of severity:

Intestinal rumbling

Abdominal cramping

These symptoms begin 12 to 72 hours after ingesting contaminated food or water. Vomiting, headache, and muscle pain are particularly common in infections caused by norovirus. Rarely, diarrhea is bloody.

Most cases are mild and disappear without treatment within 3 to 5 days.

Diagnosis of Traveler’s Diarrhea

A doctor's evaluation

Rarely stool tests

Diagnostic tests are rarely needed, but sometimes stool samples are tested for bacteria, viruses, or parasites, typically in people who have fever, severe abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea.

Treatment of Traveler’s Diarrhea

Medications that stop diarrhea (antidiarrheal medications)

Sometimes antibiotics or antiparasitic medications

When symptoms occur, treatment includes drinking plenty of fluids and taking antidiarrheal medications such as loperamide .

These medications are not given to children under 18 years of age with acute diarrhea. Antidiarrheal medications are also not given to people who have recently used antibiotics, who have bloody diarrhea, who have small amounts of blood in the stool that are too small to be seen, or who have diarrhea and fever.

Antibiotics are not necessary for mild traveler's diarrhea.

However, if diarrhea is more severe (3 or more loose stools over 8 hours), antibiotics are often given. Adults may be given ciprofloxacin , levofloxacin , azithromycin , or rifaximin . Children may be given azithromycin . Antibiotics are not given if a virus is the cause.

Antiparasitic medications are given if a parasite is identified in the stool.

Travelers are encouraged to seek medical care if they develop fever or blood in the stool.

Prevention of Traveler’s Diarrhea

Safe consumption of food and water

Travelers should eat only in restaurants with a reputation for safety and should not consume any food or beverages from street vendors. Cooked foods that are still hot when served are generally safe. Salads containing uncooked vegetables or fruit and salsa left on the table in open containers should be avoided. Any fruit should be peeled by the traveler.

Travelers should drink only bottled carbonated beverages or beverages made with water that has been boiled. Even ice cubes should be made with water that has been boiled.

Buffets and fast food restaurants pose an increased risk of infection.

Preventive antibiotics are recommended only for people who are particularly susceptible to the consequences of traveler’s diarrhea, such as those whose immune system is impaired, those who have inflammatory bowel disease, those who have HIV, those who have received an organ transplant, and those who have severe heart or kidney disease. The antibiotic most commonly given is rifaximin . Some travelers instead take bismuth subsalicylate rather than an antibiotic for prevention.

The following English-language resource may be useful. Please note that THE MANUAL is not responsible for the content of this resource.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Choose Safe Food and Drinks When Traveling

Drugs Mentioned In This Article

Was This Page Helpful?

Test your knowledge

Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada)—dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the Merck Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge .

- Permissions

- Cookie Settings

- Terms of use

- Veterinary Edition

- IN THIS TOPIC

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Collections

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Travel Medicine

- About the International Society of Travel Medicine

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction.

- < Previous

Medications for the prevention and treatment of travellers’ diarrhea

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David N. Taylor, Davidson H. Hamer, David R. Shlim, Medications for the prevention and treatment of travellers’ diarrhea, Journal of Travel Medicine , Volume 24, Issue suppl_1, April 2017, Pages S17–S22, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taw097

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Background . Travellers’ diarrhea (TD) remains one of the most common illnesses encountered by travellers to less developed areas of the world. Because bacterial pathogens such as enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), enteroaggregative E. coli , Campylobacter spp. and Shigella spp. are the most frequent causes, antibiotics have been useful in both prevention and treatment of TD.

Methods. Results of trials that assessed the use of medications for the prevention and treatment of TD were identified through PubMed and MEDLINE searches using search terms ‘travellers’ diarrhea’, ‘prevention’ and ‘treatment’. References of articles were also screened for additional relevant studies.

Results. Prevention of TD with antibiotics has been recommended only under special circumstances. Doxycycline, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, fluoroquinolones and rifaximin have been used for prevention, but at present the first three antibiotics may have limited use secondary to increasing resistance, leaving rifaximin as the only current option. Bismuth subsalicylate (BSS) (Pepto-Bismol tablets) is also an option for prophylaxis. Treatment with antibiotics has been recommended for moderate to severe TD. Azithromycin is the drug of choice, especially in Asia where Campylobacter is common. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics continue to be effectively used in Latin America and Africa where ETEC is predominant. BSS and loperamide (LOP) also are effective as standalone treatments. LOP may be used alone for treatment of mild TD or in conjunction with antibiotics for treatment of TD.

Conclusions . Historically, antibiotic prophylaxis has not been routinely recommended and has been reserved for special circumstances such as when a traveller with an underlying illness cannot tolerate TD. Antibiotics with or without LOP have been useful in shortening the duration and severity of TD. Emerging antibiotic resistance, limited new antibiotic alternatives and faecal carriage of antibiotic-resistant bacteria by travellers may prompt a re-evaluation of classic recommendations for treatment and prevention of TD with antibiotics.

Preventing and treating travellers’ diarrhea (TD) during and after a journey continue to be important clinical challenges. Bacterial pathogens such as enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), enteroaggregative E. coli , Campylobacter species and Shigella spp. still predominate as causes; however the list of etiologic agents causing diarrheal disease includes a broad spectrum of bacteria, viruses and parasites. 1–3 As diagnostic methods improve, multiple pathogens are detected in a higher proportion of TD illnesses. 4 , 5 Antimicrobial resistance of enteric bacterial pathogens continues to increase and requires surveillance to monitor current trends. 6 Emerging research has further highlighted the acute and chronic health consequences of TD. 7 There is now increasing awareness of alterations to gut microflora caused by even a short course of antibiotics. 8 Some of these changes to the gut microflora appear to be associated with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms and enteropathy, and there is growing recognition of colonization with multi‐drug resistant bacteria in returning travellers. 9 This review outlines the classical recommendations for use of antimicrobial and other agents in the treatment and prevention of TD and sets the stage for the consensus statements that follow on how recommendations might need to change in view of emerging concerns for the use of antimicrobial agents.

Results of trials that assessed the use of antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of TD were identified through PubMed and MEDLINE searches using search terms ‘travellers’ diarrhea’, ‘prevention’ and ‘treatment’. References of articles were also screened for additional relevant studies.

Historical Definitions of Diarrhea

Diarrhea is one of the most common illnesses acquired during travel. TD caused by ETEC, the most common aetiology, is usually a watery diarrhea associated with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping or pain. Shigella and Campylobacter may also be associated with bloody diarrhea instead of watery diarrhea and a longer and more severe course of illness, associated with invasion of the gut mucosa. ETEC is confined to the lumen of the gut and disease is mediated by toxin. Invasion of the gut mucosa or spread to blood or other tissues does not occur. The spectrum of illness has been categorized as mild, moderate or severe. Severe diarrhea is characterized by more than 10 loose, watery stools in a single day, moderate diarrhea is more than a few diarrhea stools but less than 10 diarrhea stools in a day, and mild diarrhea is a few diarrhea stools in a day. In clinical and epidemiologic studies, TD has been defined as three or more unformed stools or two unformed stools with at least one accompanying symptom (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, blood in stool) within 24 h. 10

History of Antibiotic Use for TD

When Dr Benjamin Kean first started investigating diarrhea in travellers in Mexico in the 1950s, the aetiology was elusive. The known bacterial pathogens of the time were not present in these patients. 11 An exhaustive search for protozoan pathogens proved fruitless. 12 An interesting observation, at the time, was that non-absorbable antibiotics (phthalylsulfathiazole and neomycin) prevented diarrhea in travellers. 13 , 14 Eventually, the discovery of ETEC confirmed the predominantly bacterial aetiology of TD in Mexico. 15 , 16 Studies in the mid-East, Asia and South America provided additional proof that bacteria were the main cause of TD. 2 , 17 , 18 By 1970s, the threat of TD was such a concern that studies were done to see if prophylactic antibiotics would prevent TD. Doxycycline was proven to prevent TD in two studies in the late 1970s. 19 , 20 At the same time, clinicians were convinced that travellers who were able to make good decisions about what to avoid eating and drinking could also avoid TD. This feeling continues to persist, despite the absence of any reliable studies demonstrating that travellers can avoid TD by watching what they eat. 21 Since TD was not fully preventable by taking precautions with food and beverages, the discussion naturally focused on antimicrobial prophylaxis or treatment, both of which had been shown to be effective. 22 However, at the same time, many clinicians still considered TD to be a minor, self-limited illness for which antibiotic treatment was not indicated. There was also an ongoing feeling among clinicians that empiric treatment was not justified, and that a definitive diagnosis should be made before treatment could be offered.

Whatever the concerns were about treatment, the impact of TD was and still remains significant for travellers. The incidence of TD in resource-poor countries is never less than 20–30% of travellers, and can be as much as 88%. That means the chance that a traveller will have their trip impacted by an episode of uncomfortable diarrhea ranges from 1 in 5 to over 4 in 5.

The concept that TD is a self-limited illness that does not require treatment is belied by the magnitude of the symptoms present in a majority of cases. Vomiting, fever, severe cramps and blood in the stool are present in a substantial subset of travellers with acute gastroenteritis. A description of the natural history of TD acquired among Finnish travellers in Morocco found that 23% of patients with an identifiable invasive pathogen were still ill at day 7. Among patients with no pathogen identified, or a non-invasive pathogen, 20% were still ill after 4 days. 23 Significantly, 37% of patients with an identified bacterial pathogen had fever.

Empiric Treatment of Diarrhea—Historical Perspective

Once it was confirmed that pathogenic bacteria were the main cause of acute TD, this paved the way for empiric treatment without obtaining stool exams or cultures. 18 , 24 Since TD often occurred in a setting far from medical care, the next step was to provide travellers with empiric antibiotics to carry with them, to minimize the impact of TD when it occurred. This approach was recommended as early as 1985. The initial antibiotic that was used was trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP–SMX), twice a day for 5 days. 25 . Clinical experience later demonstrated that many patients were better within 24 h of taking their first one or two doses, and they did not always finish the remaining course. Subsequently, treatment was shortened to three days, and even less. In the latter half of the 1980s, resistance to TMP–SMX began to be noted, with resulting treatment failures. 26 Fluoroquinolones were then employed. 27–29 The length of treatment with ciprofloxacin was twice a day for three days, which later was gradually shortened to one day, as studies confirmed that even single dose treatment could be effective. 30 Early randomized, placebo-controlled trial of ciprofloxacin in 1987 demonstrated that the mean duration of diarrhea in the treatment group was 1.5 vs. 2.9 days in the placebo group. 29 In addition, the mean duration of fever was 1.3 vs. 3.1 days. In this study, two patients in the placebo group subsequently received ciprofloxacin: one patient with fever after 4 days, and one patient with 5 days of diarrhea. Both patients improved after one day of treatment with ciprofloxacin 500 mg BID.

Starting in the mid-1990s in Thailand, fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni began to be noted. 31 This increased rapidly, and since C. jejuni was found to account for 20–25% of the etiology of diarrhea in Thailand (and Nepal), this had an impact on treatment failure. Based on the observation that Campylobacter was sensitive to erythromycin, azithromycin (AZM) began to be used for fluoroquinolone treatment failures, and later as empiric treatment. 30 , 32

In 1985, an influential TD consensus statement concluded that it was difficult to prevent TD with eating precautions, although they conjectured that it was possible. 21 , 33 Prophylactic antibiotics were discouraged, due to the risk of side effects from the mass administration of antibiotics, and the possibility of creating resistant organisms. Empiric treatment was the recommended approach to TD. 24 , 30 In the late 1990s, a non-absorbable antibiotic, rifaximin, was tested for both the prophylaxis and treatment of TD. 34–36 However, rifaximin could not be used to treat invasive organisms, such as Campylobacter or Shigella , so its usefulness for empiric self-treatment of TD was limited in many parts of the world.

Non-Antibiotic Therapy for Empiric Treatment of diarrhea—Historical Perspective

In the mid-1970s, bismuth subsalicylate (BSS) as a liquid formulation was first evaluated for the treatment of TD. 37 US subjects with TD acquired in Mexico were treated with 4.2 g of BSS over a 3.5-h period, which resulted in a decrease in the number of unformed stools compared to placebo. In a study of TD prevention, US students in Mexico received BSS or placebo for 21 days. TD occurred in 23% of 62 students taking BSS compared to 61% of 66 students taking placebo. 38 A second prevention study was performed using BSS tablets. US students visiting Mexico received two tablets (high dose) or one tablet (low dose) of BSS four times daily or a placebo during a three-week period. TD occurred in 7 (14%) of 51 receiving the high-dose regimen compared with 15 (24%) of 63 receiving the low-dose regimen and 23 (40%) of 58 in the placebo group. BSS in both dosages caused blackening of tongues and stools and infrequently was associated with tinnitus. 39 BSS at doses of 150 mg/kg was also found to be safe and effective in treating infantile diarrhea even when the cause of illness was viral. 40 , 41

BSS was compared to loperamide (LOP) for the treatment of non-dysenteric TD in US students in Mexico. 39 , 42 LOP was more effective than BSS in reducing the number of unformed stools at all time points and was more often associated with constipation than BSS. BSS was also shown to be effective in Africa 43 and treatment with BSS or LOP became an other option for the treatment of TD. 44 The utility of an anti-motility drug such as LOP to lessen diarrhea, particularly in the first 24 h of illness, has historically been offset by the concern that it could worsen an illness caused by an invasive pathogen such as Shigella . This led to evaluation of the safety of LOP when taken along with an antibiotic. One of the first studies of this kind, was the evaluation of TMP–SMX with LOP versus LOP alone. 45 The combination of antibiotic plus LOP gave the shortest duration of diarrhea compared with the placebo group (1 vs 59 h). The authors concluded that the combination of TMP–SMX plus LOP can be highly recommended for the treatment of most patients with traveller's diarrhea. Other studies found that the combination of ciprofloxacin plus LOP was also effective and safe to use even in the presence of dysentery caused by Shigella . 27 , 46

Hill evaluated the choices made by US travellers for TD. 47 Overall, 80% of persons with TD chose to take some medication. BSS or LOP were taken by 48%, while 30% took an antibiotic with an antimotility drug and 15% took antibiotic alone. About 80% of persons said that their symptoms improved regardless of treatment category. In a recent placebo-controlled study, BSS was evaluated to reduce the use of antibiotics among Pakistani adults who presented to outpatient clinics with diarrhea. 48 In this study 9.1% of 220 patients were eventually treated with antibiotics in the BSS group and 15.5% in the placebo group. There was a 41% reduction in antibiotic use among those who received BSS, but the study did not report on the length of time that the patients remained ill. These studies suggest that BSS may be tried first and will often allow patients to avoid antibiotics. LOP could also be tried as a first medication but appears to be more reliably used in combination with an antibiotic.

Current Recommendations on Medications for the Prevention and Treatment of TD

Medications for td prophylaxis.

Agents available for the management of TD

Adapted from Hill et al. 49 .

Should be considered mainly for trips <2 weeks in duration.

The recommended over-the-counter dose is 8 mg daily.

Effectiveness of rifaximin and fluoroquinolones in preventing TD: systematic review and meta-analysis

Alajbegovic et al. 51 .

In the meta-analysis performed by Alajbegovic et al. , the fluoroquinolone antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin, given for prevention showed a high degree of protection ( Table 2 ). 51 However, many of the studies were performed in the 1980s and 1990s before fluoroquinolone resistance was detected. It is likely that if the studies were repeated today in Asia, fluoroquinolone antibiotics would be less effective due to the increasing prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance documented in South and South East Asia. 52–55 Prophylactic fluoroquinolone use can also be discouraged because fluoroquinolones are one of the mainstays of treatment. In addition, in May 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a new Black Box warning for fluoroquinolones ( http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM500591.pdf ), advising that the potentially serious side effects (tendon, joint and muscle pain; paresthesia; confusion and hallucination) associated with this class of antibiotic generally outweigh the benefits for patients with acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis and uncomplicated urinary tract infections who have other treatment options. While these recommendations do not apply to short treatment courses of fluoroquinolones and the FDA did not specifically comment on serious adverse events associated with the use of fluoroquinolones for TD, the risk of longer term treatment that is likely to result during prophylactic use might be another reason for avoiding this class of agents for the prevention of TD.

If diarrhea occurs while on fluoroquinolone prophylaxis, the only remaining option is AZM. Additionally, fluoroquinolone prophylaxis, and antibiotic use in general, may have unintended consequences such as selection for antibiotic resistant gut flora 9 , 56 or disruption of the gut microbiome that could lead to colonization with pathogenic bacteria such as Clostridium difficile .

Risk factors associated with TD

Adapted from Ericsson CD. Prevention of TD in Travel Medicine 2 nd edition. 59

Medications for Empiric Self-Treatment

The alternative to prophylaxis is self-treatment. Studies have shown that up to half of all TD cases are mild and self-limited after a day or two of illness. The use of empiric self-treatment of antibiotics for bacterial diarrhea has been a very successful method of keeping travellers from getting stranded at destinations, on treks, and facing unnecessary hospitalization in a developing country. Given that it is difficult to anticipate which traveller to which destination might become severely ill, current recommendations are to provide antibiotics to travellers for use in an emergency, even in lower risk destinations. Many recommendations encourage the use of antibiotics only for more severe illness. A step wise approach to treatment has been espoused in recommendations; first try BSS or LOP to see if they provide enough relief for mild illness and reserve antibiotic self-treatment for moderate or severe TD.

Treatment of travellers’ diarrhea with rifaximin and/or LOP

DuPont et al. 36

TLUS, time to last unformed stool.

Comparative efficacy and tolerability of single doses of AZM and the combination of LOP and single dose AZM in the treatment of acute TD

Ericsson et al. 58 .

The routine use of empiric antibiotics for TD has recently been questioned again, this time due to the specific concern about travellers acquiring highly resistant E. coli during travel, along with general concerns of change in the intestinal microbiome, and increasing antibiotic resistant of intestinal pathogens. Already, there are signs of bacterial resistance to AZM, with no obvious replacement antibiotic on the horizon. As a result, the ongoing history of antibiotic treatment of TD remains unsettled. This is a disturbing prospect for those clinicians old enough to remember the pre-antibiotic era of TD.

Conflict of interest : None declared.

Jiang ZD , Lowe B , Verenkar MP et al. Prevalence of enteric pathogens among international travelers with diarrhea acquired in Kenya (Mombasa), India (Goa), or Jamaica (Montego Bay) . J Infect Dis 2002 ; 185 : 497 – 502 .

Google Scholar

Shah N , Ldupont H , Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present . Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009 ; 80 : 609 – 14 .

Swaminathan A , Torresi J , Schlagenhauf P et al. A global study of pathogens and host risk factors associated with infectious gastrointestinal disease in returned international travellers . J Infect 2009 ; 59 : 19 – 27 .

Koo HL , Ajami NJ , Jiang ZD et al. Noroviruses as a cause of diarrhea in travelers to Guatemala, India, and Mexico . J Clin Microbiol 2010 ; 48 : 1673 – 6 .

Mattila L , Siitonen A , Kyrönseppä H et al. Seasonal variation in etiology of travelers’ diarrhea. Finnish-Moroccan Study Group . J Infect Dis 1992 ; 165 : 385 – 8 .

Ouyang-Latimer J , Jafri S , VanTassel A et al. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial enteropathogens isolated from international travelers to Mexico, Guatemala, and India from 2006 to 2008 . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011 ; 55 : 874 – 8 .

Youmans BP , Ajami NJ , Jiang ZD et al. Characterization of the human gut microbiome during travelers’ diarrhea . Gut Microbes 2015 ; 6 : 110 – 9 .

Dethlefsen L , Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011 ; 108 ( Suppl 1 ): 4554 – 61 .

Kantele A , Lääveri T , Mero S et al. Antimicrobials increase travelers’ risk of colonization by extended-spectrum betalactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae . Clin Infect Dis 2015 ; 60 : 837 – 46 .

DuPont HL , Cooperstock M , Corrado ML , Fekety R. Evaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Food and Drug Administration . Clin Infect Dis 1992 ; 15 ( Suppl 1 ): S228 – 35 .

Varela G , Kean BH , Barrett EL , Keegan CJ. The diarrhea of travelers. II. Bacteriologic studies of U. S. students in Mexico . Am J Trop Med Hyg 1959 ; 8 : 353 – 7 .

Rosenbluth MA , Schaffner W , Kean BH. The diarrhea of travelers. IV. Viral studies of visiting students in Mexico with further bacteriologic and parasitologic observations . Am J Trop Med Hyg 1963 ; 12 : 239 – 45 .

Kean BH , Waters SR. The diarrhea of travelers . N Engl J Med 1959 ; 261 : 71 – 4 .

Kean B , Schaffner W , Brennan RW. The diarrhea of travelers V. prophylaxis with phthalylsulfathiazole and neomycin sulphate . JAMA 1962 ; 180 : 367 – 71 .

Gorbach SL , Kean BH , Evans DG , Evans DJ , Bessudo D. Travelers’ diarrhea and toxigenic Escherichia coli . N Engl J Med 1975 ; 292 : 933 – 6 .

Merson MH , Morris GK , Sack DA et al. Travelers’ diarrhea in Mexico . N Engl J Med 1976 ; 294 : 1299 – 305 .

Rowe B , Taylor J , Bettelheim KA. An investigation of traveller’s diarrhoea . Lancet 1970 ; 1 : 1 – 5 .

Taylor DN , Houston R , Shlim DR , Bhaibulaya M , Ungar BL , Echeverria P. Etiology of diarrhea among travelers and foreign residents in Nepal . JAMA 1988 ; 260 : 1245 – 8 .

Sack RB , Froehlich JL , Zulich AW et al. Prophylactic doxycycline for travelers’ diarrhea: results of a prospective double-blind study of Peace Corps volunteers in Morocco . Gastroenterology 1979 ; 76 : 1368 – 73 .

Sack DA , Kaminsky DC , Sack RB et al. Prophylactic doxycycline for travelers’ diarrhea . N Engl J Med 1978 ; 298 : 758 – 63 .

Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent traveler’s diarrhea . Clin Infect Dis 2005 ; 41 (Suppl 8) : S531 – 5 .

Gorbach S. How to hit the runs for fifty million travelers at risk . Ann Intern Med 2005 ; 142 : 861 – 2 .

Mattila L. Clinical features and duration of traveler’s diarrhea in relation to its etiology . Clin Infect Dis 1994 ; 19 : 728 – 34 .

Hoge CW , Shlim DR , Echeverria P , Rajah R , Herrmann JE , Cross JH. Epidemiology of diarrhea among expatriate residents living in a highly endemic environment . JAMA 1996 ; 275 : 533 – 8 .

DuPont HL , Reves RR , Galindo E , Sullivan PS , Wood LV , Mendiola JG. Treatment of travelers’ diarrhea with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and with trimethoprim alone . N Engl J Med 1982 ; 307 : 841 – 4 .

Rudy RP , Murray BE. Evidence for an epidemic trimethoprim-resistance plasmid in fecal isolates of Escherichia coli from citizens of the united states studying in Mexico . J Infect Dis 1984 ; 150 : 25 – 9 .

Taylor DN , Sanchez JL , Candler W , Thornton S , McQueen C , Echeverria P. Treatment of travelers diarrhea: Ciprofloxacin plus loperamide compared with ciprofloxacin alone: a placebo-controlled, randomized trial . Ann Intern Med 1991 ; 114 : 731 .

Mattila L , Peltola H , Siitonen A , Kyrönseppä H , Simula I , Kataja M. Short-term treatment of traveler’s diarrhea with norfloxacin: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study during two seasons . Clin Infect Dis 1993 ; 17 : 779 – 82 .

Pichler HE , Diridl G , Stickler K , Wolf D. Clinical efficacy of ciprofloxacin compared with placebo in bacterial diarrhea . Am J Med 1987 ; 82 : 329 – 32 .

Tribble DR , Sanders JW , Pang LW et al. Traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen . Clin Infect Dis 2007 ; 44 : 338 – 46 .

Kuschner RA , Trofa AF , Thomas RJ et al. Use of azithromycin for the treatment of campylobacter enteritis in travelers to Thailand, an area where ciprofloxacin resistance is prevalent . Clin Infect Dis 1995 ; 21 : 536 – 41 .

Sanders JW , Frenck RW , Putnam SD et al. Azithromycin and loperamide are comparable to levofloxacin and loperamide for the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea in United States military personnel in Turkey . Clin Infect Dis 2007 ; 45 : 294 – 301 .

Travelers’ diarrhea. NIH Consensus Development Conference . JAMA 1985 ; 253 : 2700 – 4 .

DuPont HL , Jiang Z , Ericsson CD et al. Rifaximin versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea: a randomized, double‐blind clinical trial . Clin Infect Dis 2001 ; 33 : 1807 – 15 .

Taylor DN , Bourgeois AL , Ericsson CD et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea . Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006 ; 74 : 1060 – 6 .

Dupont HL , Jiang ZD , Belkind-Gerson J et al. Treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: randomized trial comparing rifaximin, rifaximin plus loperamide, and loperamide alone . Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007 ; 5 : 451 – 6 .

DuPont HL , Sullivan P , Pickering LK , Haynes G , Ackerman PB. Symptomatic treatment of diarrhea with bismuth subsalicylate among students attending a Mexican university . Gastroenterology 1977 ; 73 : 715 – 8 .

DuPont HL , Sullivan P , Evans DG et al. Prevention of traveler’s diarrhea (emporiatric enteritis). Prophylactic administration of subsalicylate bismuth) . JAMA 1980 ; 243 : 237 – 41 .

DuPont HL , Ericsson CD , Johnson PC , Bitsura JA , DuPont MW , de la Cabada FJ. Prevention of travelers’ diarrhea by the tablet formulation of bismuth subsalicylate . JAMA 1987 ; 257 : 1347 – 50 .

Soriano-Brücher H , Avendaño P , O’ryan M et al. Bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children: a clinical study . Pediatrics 1991 ; 87 : 18 – 27 .

Figueroa-Quintanilla D , Salazar-Lindo E , Sack RB et al. A controlled trial of bismuth subsalicylate in infants with acute watery diarrheal disease . N Engl J Med 1993 ; 328 : 1653 – 8 .

DuPont HL , Flores Sanchez J , Ericsson CD et al. Comparative efficacy of loperamide hydrochloride and bismuth subsalicylate in the management of acute diarrhea . Am J Med 1990 ; 88 : 15S – 9S .

Steffen R , Mathewson JJ , Ericsson CD et al. Travelers’ diarrhea in West Africa and Mexico: fecal transport systems and liquid bismuth subsalicylate for self-therapy . J Infect Dis 1988 ; 157 : 1008 – 13 .

Steffen R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea . Rev Infect Dis 1990 ; 12(Suppl 1) : S80 – 6 .

Ericsson CD , DuPont HL , Mathewson JJ , West MS , Johnson PC , Bitsura JA. Treatment of traveler’s diarrhea with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim and loperamide . JAMA 1990 ; 263 : 257 – 61 .

Murphy GS1 , Bodhidatta L , Echeverria P et al. Ciprofloxacin and loperamide in the treatment of bacillary dysentery . Ann Intern Med 1993 ; 118 : 582 – 6 .

Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries . Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000 ; 62 : 585 – 9 .

Bowen A , Agboatwalla M , Pitz A , Brum J , Plikaytis BD. Bismuth subsalicylate reduces antimicrobial use among adult diarrhea patients in Pakistan: a randomized, placebo-controlled, triple-masked clinical trial. In: 65th Annual Meeting of the ASTMH. Atlanta, GA; 2016 . p. Abstract 1202.

Hill DR , Ericsson CD , Pearson RD et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America . Clin Infect Dis 2006 ; 43 : 1499 – 539 .

Ponziani FR , Scaldaferri F , Petito V et al. The role of antibiotics in gut microbiota modulation: the eubiotic effects of rifaximin . Dig Dis 2016 ; 34 : 269 – 78 .

Alajbegovic S , Sanders JW , Atherly DE , Riddle MS. Effectiveness of rifaximin and fluoroquinolones in preventing travelers’ diarrhea (TD): a systematic review and meta-analysis . Syst Rev 2012 ; 1 : 39.

Hoge CW , Gambel JM , Srijan A , Pitarangsi C , Echeverria P. Trends in antibiotic resistance among diarrheal pathogens isolated in Thailand over 15 years . Clin Infect Dis 1998 ; 26 : 341 – 5 .

Barlow RS , Debess EE , Winthrop KL , Lapidus JA , Vega R , Cieslak PR. Travel-associated antimicrobial drug-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonellae , 2004-2009 . Emerg Infect Dis 2014 ; 20 : 603 – 11 .

De Lappe N , O’connor J , Garvey P , McKeown P , Cormican M. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Shigella sonnei associated with travel to India . Emerg Infect Dis 2015 May ; 21 : 894 – 6 .

Vila J , Vargas M , Ruiz J , Corachan M , De Anta MTJ , Gascon J. Quinolone resistance in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli causing diarrhea in travelers to India in comparison with other geographical areas . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000 ; 44 : 1731 – 3 .

Connor BA , Keystone JS. Antibiotic self-treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: helpful or harmful? . Clin Infect Dis 2015 ; 60 : 847 – 8 .

DuPont HL , Jiang ZD , Okhuysen PC et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin to prevent travelers’ diarrhea . Ann Intern Med 2005 ; 142 : 805 – 12 .

DuPont HL , Jiang ZD , Okhuysen PC et al. Loperamide plus azithromycin more effectively treats travelers’ diarrhea in Mexico than azithromycin alone . J Travel Med 2007 ; 14 : 312 – 9 .

Ericsson C. D. Prevention of Travelers Diarrhea. 2nd ed. In: Keystone JS , Kozarsky PE , Freedman DO , Nothdurft HD , Connor B (ed). Travel Medicine . Elsevier Ltd ., 2008 . pp. 191 – 196

Google Preview

- antibiotics

- bismuth subsalicylate

- fluoroquinolones

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole combination

- pathogenic organism

- enterotoxigenic escherichia coli

- campylobacter

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1708-8305

- Copyright © 2024 International Society of Travel Medicine

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Traveler's diarrhea

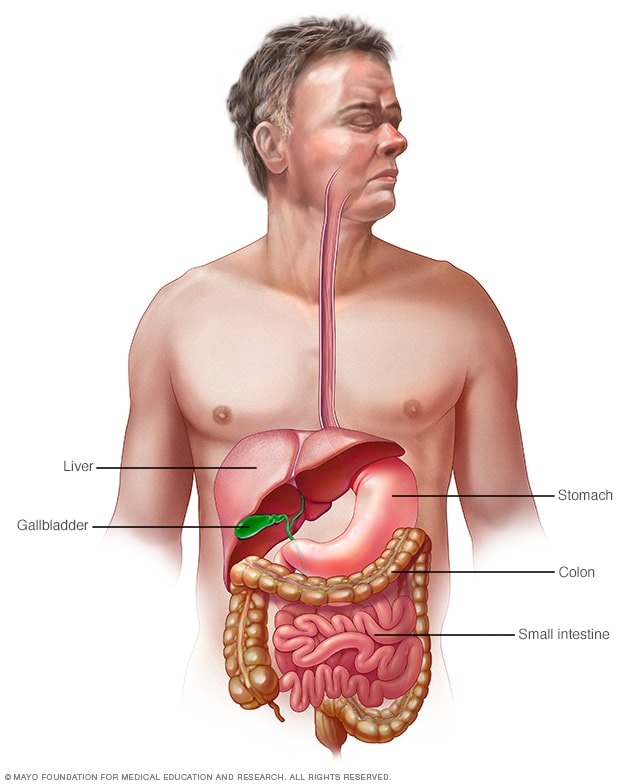

Gastrointestinal tract

Your digestive tract stretches from your mouth to your anus. It includes the organs necessary to digest food, absorb nutrients and process waste.

Traveler's diarrhea is a digestive tract disorder that commonly causes loose stools and stomach cramps. It's caused by eating contaminated food or drinking contaminated water. Fortunately, traveler's diarrhea usually isn't serious in most people — it's just unpleasant.

When you visit a place where the climate or sanitary practices are different from yours at home, you have an increased risk of developing traveler's diarrhea.

To reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea, be careful about what you eat and drink while traveling. If you do develop traveler's diarrhea, chances are it will go away without treatment. However, it's a good idea to have doctor-approved medicines with you when you travel to high-risk areas. This way, you'll be prepared in case diarrhea gets severe or won't go away.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

Traveler's diarrhea may begin suddenly during your trip or shortly after you return home. Most people improve within 1 to 2 days without treatment and recover completely within a week. However, you can have multiple episodes of traveler's diarrhea during one trip.

The most common symptoms of traveler's diarrhea are:

- Suddenly passing three or more looser watery stools a day.

- An urgent need to pass stool.

- Stomach cramps.

Sometimes, people experience moderate to severe dehydration, ongoing vomiting, a high fever, bloody stools, or severe pain in the belly or rectum. If you or your child experiences any of these symptoms or if the diarrhea lasts longer than a few days, it's time to see a health care professional.

When to see a doctor

Traveler's diarrhea usually goes away on its own within several days. Symptoms may last longer and be more severe if it's caused by certain bacteria or parasites. In such cases, you may need prescription medicines to help you get better.

If you're an adult, see your doctor if:

- Your diarrhea lasts beyond two days.

- You become dehydrated.

- You have severe stomach or rectal pain.

- You have bloody or black stools.

- You have a fever above 102 F (39 C).

While traveling internationally, a local embassy or consulate may be able to help you find a well-regarded medical professional who speaks your language.

Be especially cautious with children because traveler's diarrhea can cause severe dehydration in a short time. Call a doctor if your child is sick and has any of the following symptoms:

- Ongoing vomiting.

- A fever of 102 F (39 C) or more.

- Bloody stools or severe diarrhea.

- Dry mouth or crying without tears.

- Signs of being unusually sleepy, drowsy or unresponsive.

- Decreased volume of urine, including fewer wet diapers in infants.

It's possible that traveler's diarrhea may stem from the stress of traveling or a change in diet. But usually infectious agents — such as bacteria, viruses or parasites — are to blame. You typically develop traveler's diarrhea after ingesting food or water contaminated with organisms from feces.

So why aren't natives of high-risk countries affected in the same way? Often their bodies have become used to the bacteria and have developed immunity to them.

Risk factors

Each year millions of international travelers experience traveler's diarrhea. High-risk destinations for traveler's diarrhea include areas of:

- Central America.

- South America.

- South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Traveling to Eastern Europe, South Africa, Central and East Asia, the Middle East, and a few Caribbean islands also poses some risk. However, your risk of traveler's diarrhea is generally low in Northern and Western Europe, Japan, Canada, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Your chances of getting traveler's diarrhea are mostly determined by your destination. But certain groups of people have a greater risk of developing the condition. These include:

- Young adults. The condition is slightly more common in young adult tourists. Though the reasons why aren't clear, it's possible that young adults lack acquired immunity. They may also be more adventurous than older people in their travels and dietary choices, or they may be less careful about avoiding contaminated foods.

- People with weakened immune systems. A weakened immune system due to an underlying illness or immune-suppressing medicines such as corticosteroids increases risk of infections.

- People with diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, or severe kidney, liver or heart disease. These conditions can leave you more prone to infection or increase your risk of a more-severe infection.

- People who take acid blockers or antacids. Acid in the stomach tends to destroy organisms, so a reduction in stomach acid may leave more opportunity for bacterial survival.

- People who travel during certain seasons. The risk of traveler's diarrhea varies by season in certain parts of the world. For example, risk is highest in South Asia during the hot months just before the monsoons.

Complications

Because you lose vital fluids, salts and minerals during a bout with traveler's diarrhea, you may become dehydrated, especially during the summer months. Dehydration is especially dangerous for children, older adults and people with weakened immune systems.

Dehydration caused by diarrhea can cause serious complications, including organ damage, shock or coma. Symptoms of dehydration include a very dry mouth, intense thirst, little or no urination, dizziness, or extreme weakness.

Watch what you eat

The general rule of thumb when traveling to another country is this: Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it. But it's still possible to get sick even if you follow these rules.

Other tips that may help decrease your risk of getting sick include:

- Don't consume food from street vendors.

- Don't consume unpasteurized milk and dairy products, including ice cream.

- Don't eat raw or undercooked meat, fish and shellfish.

- Don't eat moist food at room temperature, such as sauces and buffet offerings.

- Eat foods that are well cooked and served hot.

- Stick to fruits and vegetables that you can peel yourself, such as bananas, oranges and avocados. Stay away from salads and from fruits you can't peel, such as grapes and berries.

- Be aware that alcohol in a drink won't keep you safe from contaminated water or ice.

Don't drink the water

When visiting high-risk areas, keep the following tips in mind:

- Don't drink unsterilized water — from tap, well or stream. If you need to consume local water, boil it for three minutes. Let the water cool naturally and store it in a clean covered container.

- Don't use locally made ice cubes or drink mixed fruit juices made with tap water.

- Beware of sliced fruit that may have been washed in contaminated water.

- Use bottled or boiled water to mix baby formula.

- Order hot beverages, such as coffee or tea, and make sure they're steaming hot.

- Feel free to drink canned or bottled drinks in their original containers — including water, carbonated beverages, beer or wine — as long as you break the seals on the containers yourself. Wipe off any can or bottle before drinking or pouring.

- Use bottled water to brush your teeth.

- Don't swim in water that may be contaminated.

- Keep your mouth closed while showering.

If it's not possible to buy bottled water or boil your water, bring some means to purify water. Consider a water-filter pump with a microstrainer filter that can filter out small microorganisms.

You also can chemically disinfect water with iodine or chlorine. Iodine tends to be more effective, but is best reserved for short trips, as too much iodine can be harmful to your system. You can purchase water-disinfecting tablets containing chlorine, iodine tablets or crystals, or other disinfecting agents at camping stores and pharmacies. Be sure to follow the directions on the package.

Follow additional tips

Here are other ways to reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea:

- Make sure dishes and utensils are clean and dry before using them.

- Wash your hands often and always before eating. If washing isn't possible, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol to clean your hands before eating.

- Seek out food items that require little handling in preparation.

- Keep children from putting things — including their dirty hands — in their mouths. If possible, keep infants from crawling on dirty floors.

- Tie a colored ribbon around the bathroom faucet to remind you not to drink — or brush your teeth with — tap water.

Other preventive measures

Public health experts generally don't recommend taking antibiotics to prevent traveler's diarrhea, because doing so can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotics provide no protection against viruses and parasites, but they can give travelers a false sense of security about the risks of consuming local foods and beverages. They also can cause unpleasant side effects, such as skin rashes, skin reactions to the sun and vaginal yeast infections.

As a preventive measure, some doctors suggest taking bismuth subsalicylate, which has been shown to decrease the likelihood of diarrhea. However, don't take this medicine for longer than three weeks, and don't take it at all if you're pregnant or allergic to aspirin. Talk to your doctor before taking bismuth subsalicylate if you're taking certain medicines, such as anticoagulants.

Common harmless side effects of bismuth subsalicylate include a black-colored tongue and dark stools. In some cases, it can cause constipation, nausea and, rarely, ringing in your ears, called tinnitus.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Infectious enteritis and proctocolitis. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Microbiology, epidemiology, and prevention. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Ferri FF. Traveler diarrhea. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Elsevier; 2023. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Diarrhea. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/diarrhea. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Travelers' diarrhea. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/travelers-diarrhea. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Khanna S (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 29, 2021.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Please note: This information was current at the time of publication but now may be out of date. This handout provides a general overview and may not apply to everyone.

Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(1):135-136

See related article on traveler's diarrhea .

What is traveler's diarrhea?

Traveler's diarrhea is a kind of diarrhea you might get when you're traveling in less developed countries. Many countries in Africa, Asia and Central and South America are risky places for travelers' diarrhea. It's usually caused by eating food or drinking water that is contaminated with bacteria. The illness may also cause nausea, vomiting and cramps. Fortunately, travelers' diarrhea is usually mild, and recovery is usually quick.

If you're planning a trip to a developing country, talk to your family doctor first about what you can do to stay healthy on your trip. Your doctor can give you advice about things you can do to help prevent illnesses like traveler's diarrhea. Your doctor also may prescribe an antibiotic for you to take along with you, in case you get traveler's diarrhea.

What can I do to prevent traveler's diarrhea?

You can help prevent traveler's diarrhea by being very careful about the foods you eat and the beverages you drink when you're traveling.

Do these things:

Tie a ribbon around the water faucet handle so you'll remember not to use tap water.

Keep safe, bottled water by the sink to use for drinking and tooth brushing.

Always clean your hands before you eat, but use prepackaged hand wipes or antiseptic gel to clean your hands, not just tap water.

Don't do these things:

Don't drink tap water. Don't even use it for brushing your teeth.

Don't use ice unless you know it was made from boiled or filtered water.

Don't eat raw vegetables or salads.

Don't eat unpasteurized dairy products.

Don't eat any fruits unless you peel them yourself.

Don't buy food and drinks from street vendors.

Don't go swimming in streams and lakes because of the risk of water pollution.

What foods and drinks are safe to eat in developing countries?

Coffee and tea made with boiled water are safe. Carbonated soft drinks (without ice), beer and wine are safe. Tap water that has been boiled, filtered or purified with iodine is safe to use. Most of the time, though, it's easier to buy purified bottled water for drinking than to purify the tap water.

It's safe to eat foods that are thoroughly cooked and served piping hot. Fresh breads and most dry foods are safe to eat.

What should I do if I get traveler's diarrhea?

When you're packing for your trip, take along some loperamide just in case you get travelers' diarrhea. This medicine usually stops diarrhea quickly. You may know this drug by its brand name—Imodium A-D. Take two tablets right after your first bout of diarrhea. Then take one tablet after each episode of diarrhea. Don't take more than four tablets a day.

How will I know if I need to take an antibiotic for traveler's diarrhea?

If loperamide doesn't stop your diarrhea, you may need to take an antibiotic to get rid of the infection. Your doctor might prescribe an antibiotic for you to take with you on your trip, just in case.

Several antibiotics can be used to treat traveler's diarrhea. One antibiotic commonly used for traveler's diarrhea is ciprofloxacin (brand name: Cipro). Often, only a few doses are needed to clear up the infection. (You shouldn't take Cipro if you're pregnant or under 18.)

If the diarrhea stops 12 hours after you took the first dose of the antibiotic, you probably don't need to take any more of the medicine. But see a doctor if your diarrhea hasn't stopped after you've been taking antibiotics for three days.

What should I do so I don't get dehydrated when I have traveler's diarrhea?

One of the biggest problems caused by diarrhea is dehydration. You can prevent dehydration by drinking lots of clear liquids, such as water, juices and soft drinks. Remember to keep drinking safe, purified water.

You can also drink a product that's made just to prevent and treat the dehydration caused by diarrhea. It's called “oral rehydration” mix. You can buy it in drug stores. It comes in a powder. You mix it with safe water and drink it. You can take some packets of oral rehydration mix with you on your trip, just in case.

What are danger signs that mean I have severe diarrhea?

If you're having diarrhea and you notice blood in your stool or you also have a high fever, you may have a severe infection. Stop taking loperamide and start taking an antibiotic. See a doctor if you don't get better in a day or two.

Traveler's diarrhea can turn a great vacation into a bad vacation. But taking a few simple precautions and knowing what to do if travelers' diarrhea strikes can make the difference in your trip.

Continue Reading

More in afp.

Copyright © 1999 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Skip to content

- Accessibility help

Diarrhoea - prevention and advice for travellers: Scenario: Diarrhoea - prevention and advice for travellers

Last revised in September 2023

Covers the prevention of travellers' diarrhoea, and advice for people who are at risk of travellers' diarrhoea.

Scenario: Diarrhoea - prevention and advice for travellers

From age 1 month onwards.

How should I assess the risk of acquiring travellers' diarrhoea before travelling?

- Low-risk areas (fewer than 7% of travellers experience travellers' diarrhoea) include Western Europe, the USA, Canada, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

- Intermediate risk areas (8–20% of travellers experience travellers' diarrhoea) include southern Europe, Israel, South Africa, and some Caribbean and Pacific islands.

- High-risk areas (more than 20% of travellers experience travellers' diarrhoea) include Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and most parts of Asia.

- For up-to-date risk assessment of individual countries and the requirement for strict food, water, and personal hygiene precautions , see the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC) website ( www.nathnac.org ).

- Local amenities and sanitation — in areas with low standards of hygiene and sanitation and poor control over the safety of food, drink, and drinking water, the risk of acquiring travellers' diarrhoea is high.

- How the person will be travelling — backpackers, campers, adventurers, and passengers on cruise ships are at increased risk.

- When the person will be travelling — the peak incidence of travellers' diarrhoea is in the warmer months. Lower rates occur in winter.

- What the person eats — for example, risks are associated with food from buffets, restaurants, and street vendors, and certain types of food such as raw fish and seafood, salads, and meat and poultry that have been inadequately cooked. For more information, see Advice on food and drink .

- Review the person's susceptibility to traveller's diarrhoea and their risk of complications. For more information on which groups of people are considered to be at higher risk, see the section on Risk factors .

- Enquire about access to medical amenities — this is particularly important for those travelling to remote areas with few or no medical amenities (especially trekking and camping).

- Discuss whether visits to high-risk areas are essential (particularly if the person is at increased risk of complications) and whether they are suitably prepared (for example, if backpacking through remote areas).

Basis for recommendation

The recommendations about how to assess a person's risk of acquiring travellers' diarrhoea are largely based on expert opinion in a World Health Organisation (WHO) publication International Travel and Health [ WHO, 2012 ], the BMJ Best Practice guideline Traveller's Diarrhoea [ BMJ Best Practice, 2021 ], the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) guidance Travelers' diarrhea - Preparing International Travelers [ CDC, 2023a ], and the guidance on Travellers' diarrhoea from the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC) [ NaTHNaC, 2023 ].

How should I manage someone at low or intermediate risk of travellers' diarrhoea?

- Advise the person that most travellers' diarrhoea is caused by the consumption of contaminated food or water.

- Reassure the person that no special precautions (other than basic hygiene measures) are required when travelling to locations with a high standard of hygiene.

- Provide information on food hygiene and safe drinking water if the person is travelling to locations with lower standards of hygiene and sanitation.

- Offer advice regarding self-management and when to seek medical advice if the person develops diarrhoea during their trip.

The recommendations on managing people at low or intermediate risk of travellers' diarrhoea are largely based on expert opinion regarding general advice to offer travellers in a World Health Organisation (WHO) publication International Travel and Health [ WHO, 2012 ], the American College of Gastroenterologists guideline Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Acute Diarrheal Infections in Adults [ Riddle et al, 2016 ], the BMJ Best Practice guideline Traveller's Diarrhoea [ BMJ Best Practice, 2021 ], the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) guidance Travelers' diarrhea - Preparing International Travelers [ CDC, 2023a ] and the guidance on Travellers' diarrhoea from the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC) [ NaTHNaC, 2023 ].

How should I manage someone at high risk of travellers' diarrhoea?

- For further information, see advice on food and drink .

- Warn travellers about the risk of food- and water-borne infections and how to avoid potentially contaminated recreational water. Contaminated recreational water can be found in inadequately treated pools, water playgrounds, hot tubs, spas, and freshwater or seawater. Potential illness-causing contaminants include human faeces, animal waste, sewage, or wastewater runoff.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis may be appropriate for certain high-risk travellers. For more information, see the section on prophylactic antibiotics .

- The use of bismuth subsalicylate and probiotics for prophylaxis is not recommended.

- Antidiarrhoeal drugs (such as loperamide) should not be taken prophylactically.

- Consider whether 'stand by' antibiotic treatment (to use if affected) is appropriate. For more information, see the section on 'stand-by' antibiotics .

- Inform the person that there are no universal vaccines to cover all the infections which may cause travellers' diarrhoea. However, travellers to risky areas must seek advice about appropriate vaccination against other infections that cause gastrointestinal effects, such as cholera, hepatitis A, and typhoid. For further information on vaccines recommended for overseas travel, extended holidays, or working overseas, see the CKS topic on Immunizations - travel .

- For further information, see advice on managing travellers' diarrhoea .

The recommendations on managing people at high risk of travellers' diarrhoea are largely based on expert opinion in a World Health Organisation (WHO) publication International Travel and Health [ WHO, 2012 ], the American College of Gastroenterologists guideline Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Acute Diarrheal Infections in Adults [ Riddle et al, 2016 ], the BMJ Best Practice guideline Traveller's Diarrhoea [ BMJ Best Practice, 2021 ], the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines Travelers' diarrhea - Preparing International Travelers [ CDC, 2023a ] and Food and water precautions - Preparing International Travelers [ CDC, 2023c ] and the guidance on Travellers' diarrhoea from the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC) [ NaTHNaC, 2023 ].

What food and drink measures are recommended for preventing travellers' diarrhoea?

- Hands should always be washed with soap and water before handling and consuming food (particularly after contact with raw meat and uncooked food), using the toilet, or caring for an ill person.

- If soap and water are not available, an alcohol-based hand sanitiser can be used as an alternative until it is possible to wash the hands. Note that hand sanitiser is not effective when hands are greasy or visibly dirty and has limited effectiveness against Cryptosporidium and norovirus.

- Raw fish and seafood should be avoided, as well as shellfish, and any meat or poultry that has not been thoroughly cooked.

- Risks are associated with food from buffets, restaurants, and street vendors. Food from these sources should be avoided, if it has neither been kept hot, nor refrigerated or kept on ice.

- Cooked food that has been in contact with raw food, or contains raw or uncooked eggs (such as homemade mayonnaise), should be avoided.

- If hygiene and sanitation are likely to be inadequate, avoid salads, uncooked vegetables, and unpasteurised fruit juices. Fruits and vegetables that can be peeled by the end-user are suitable choices (fruits and vegetables with damaged skins should be avoided).

- Ice should be avoided, unless it has been made from safe water.

- Unpasteurised (raw) milk or cheese should be avoided.

- Commercially prepared carbonated drinks, pasteurised drinks, fruit juices, and alcoholic beverages are usually safe provided they are in factory-sealed containers. The surface of the container should be wiped clean and dried if the drink is to be consumed directly from the container.

- Tap water should be avoided for drinking, preparing food, making ice, cooking, and brushing teeth, unless there is reasonable certainty it is safe.

- Bottled water is the safer choice for drinking water. The seal must not have been tampered with.

- Water should be boiled (for at least 1 minute) if its safety for drinking is in doubt.

- Other options include micropore filtering and the use of disinfectant preparations. These might be more relevant for people travelling to areas where there is little or no access to safe drinking water.

- A fact sheet on Food and Water Hygiene is available on the Travel Health Pro website ( travelhealthpro.org.uk ).

The recommendations on food and drink precautions to reduce the risk of travellers' diarrhoea are based on expert opinion in the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) guidance on Travelers' diarrhea - Preparing International Travele rs [ CDC, 2023a ] and Travelers' diarrhea - Food & Water precautions [ CDC, 2023c ] and the guidance on Travellers' diarrhoea from the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC) [ NaTHNaC, 2023 ].

The CDC states that [ CDC, 2023a ]:

- Poor hygiene practices in local restaurants and underlying hygiene and sanitation infrastructure deficiencies are likely the largest contributors to the risk for travellers' diarrhoea.

- While measures such as avoiding certain food and food establishment types and ensuring food is thoroughly cooked, can help to reduce the risk of travellers' diarrhoea, it is acknowledged that some of these measures may be difficult to follow while travelling, and that some food safety factors are out of the traveller's control. Risk can therefore never be fully eliminated.

What should I advise about self-management of travellers' diarrhoea?

- That most episodes of travellers' diarrhoea are short-lived and self-limiting, and last a few days.

- To consider purchasing sachets of oral rehydration salts before travelling as they may not be available at the destination.

- For infants, breastfeeding should not be interrupted.

- Hydration must be maintained, for example with boiled, treated, or sealed bottled water. Most otherwise healthy adults can stay hydrated by eating and drinking as normal.

- Alcohol and other drinks and beverages with a diuretic effect (such as coffee and tea) and overly sweet drinks (in large quantities) should be avoided.

- For more severe symptoms, or people prone to complications from dehydration, oral rehydration powders diluted into clean drinking water can help to correct electrolyte imbalances.

- Immediate medical attention is required if children show signs of dehydration such as restlessness or irritability, great thirst, sunken eyes, and dry skin with reduced elasticity.

- Loperamide is usually considered the standard treatment when rapid control of symptoms is required — for example during travelling where toilet amenities are limited or unavailable.

- Bismuth subsalicylate is more suitable for mild diarrhoea; loperamide has a faster onset of action and is more effective than bismuth subsalicylate for controlling diarrhoea and cramping.

- Bismuth subsalicylate is not suitable for people with aspirin allergy, renal insufficiency, gout, severe enteric disease or HIV (risk of bismuth absorption), or people who are taking an anticoagulant such as warfarin, or pregnant or breastfeeding women. Darkened tongue and stools are common adverse effects.

- Advise the person not to use loperamide or bismuth subsalicylate (for example Pepto-Bismol ® ) if they have blood or mucous in the stool and/or high fever or severe abdominal pain.

- Loperamide should not be used in children younger than 12 years of age because of concerns that it may cause intestinal obstruction.

- Bismuth subsalicylate must not be used in children younger than 16 years of age because of the possible association between salicylates and Reye's syndrome.

- Stools are blood-stained, profuse and watery, or there is high or persistent fever or severe abdominal pain.

- Severe diarrhoea occurs in infants or elderly people, or a child is unwell with travellers' diarrhoea and symptomatic treatment is needed.

- The person becomes dehydrated — particularly in infants and children (restlessness or irritability, very thirsty, sunken eyes, and dry skin with reduced elasticity); or it is difficult to maintain adequate hydration.

- Diarrhoea does not begin to improve within 24–36 hours despite self-treatment.

- There is a medical comorbidity (for example immunosuppression or gastrointestinal disorder).

- NHS: www.nhs.uk — Access to healthcare abroad .

- The National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC): www.nathnac.net .

- The 'Fit for travel' website provided by NHS Scotland: www.fitfortravel.scot.nhs.uk .

- The World Health Organization: www.who.int .