- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

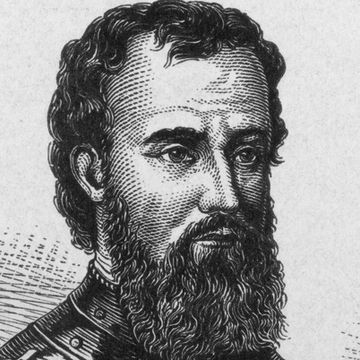

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 14, 2023 | Original: December 18, 2009

The 16th-century Spanish conquistador and explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa helped establish the first stable settlement on the South American continent at Darién, on the coast of the Isthmus of Panama.

In 1513, while leading an expedition in search of gold, he sighted the Pacific Ocean. Balboa claimed the ocean and all of its shores for Spain, opening the way for later Spanish exploration and conquest along the western coast of South America. Balboa’s achievement and ambition posed a threat to Pedro Arias Dávila, the Spanish governor of Darién, who falsely accused him of treason and had him executed in early 1519.

Early Life and Career

Balboa was born in 1475 in Jerez de los Caballeros, a town in the impoverished Extremadura region of Spain. His father was believed to be a nobleman, but the family was not wealthy; like many of his class, Balboa decided to seek his fortune in the New World.

Around 1500, he joined Spanish explorers on an expedition the coast of present-day Colombia, then returned to the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and sought to make his living as a farmer. After falling into debt, he fled his creditors by stowing away on an expedition carrying supplies to the colony of San Sebastian, located on the coast of Urabá (now Colombia), in 1510.

Did you know? The Spanish region of Extremadura, where Vasco Núñez de Balboa was born, was home to many other famous New World conquistadors, including Hernán Cortés, Francisco Pizarro, Hernando de Soto and Francisco de Orellana.

The colony had been largely abandoned by the time they arrived, after local Native Americans killed many of the colonists. At Balboa’s suggestion, they decided to move to the western side of the Gulf of Urabá, on the coast of the Isthmus of Panama, the small strip of land connecting Central and South America.

In that region, the local Indians were more peaceful, and the new colony, Darién, would become the first stable Spanish settlement on the South American continent.

Balboa Sees the Pacific

By 1511, Balboa was acting as interim governor of Darién. Under his authority, the Spaniards dealt harshly with native inhabitants of the region in order to get gold and other riches; from some of these Indians, they learned that a wealthy empire lay to the south (possibly a reference to the Inca ).

In September 1513, Balboa led an expedition of some 190 Spaniards and a number of Indians southward across the Isthmus of Panama. Late that same month, Balboa climbed a mountain peak and sighted the Pacific Ocean, which the Spaniards called the Mar del Sur (South Sea).

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Balboa, King Ferdinand II had appointed the elderly nobleman Pedro Arias Dávila (usually called Pedrarias) as the new governor of Darién.

As a reward for his explorations, Balboa was named governor of the provinces of Panama and Coiba, but remained under the authority of Pedrarias, who arrived in Darién in mid-1514, soon after Balboa returned.

Balboa’s Later Explorations and Downfall

Though suspicious of each other, the two men reached a precarious peace, and Pedrarias even betrothed his daughter María (in Spain) to Balboa by proxy. He also reluctantly gave him permission to mount another expedition to explore and conquer the Mar del Sur and its surrounding lands.

Balboa began these explorations in 1517-18, after having a fleet of ships painstakingly built and transported in pieces over the mountains to the Pacific.

Balboa Beheaded

Meanwhile, Pedrarias’ many enemies had convinced King Ferdinand to send a replacement for him from Spain and order a judicial inquiry into his conduct as leader of Darién.

Suspecting Balboa would speak against him, and fearing his influence and popularity, Pedrarias summoned the explorer home and had him arrested and tried for rebellion and high treason, among other charges.

In the highly biased trial that ensued, presided over by Pedrarias’ ally Gaspar de Espinosa, Balboa was found guilty and condemned to death. He was beheaded, along with four alleged accomplices, in 1519.

HISTORY Vault: Columbus the Lost Voyage

Ten years after his 1492 voyage, Columbus, awaiting the gallows on criminal charges in a Caribbean prison, plotted a treacherous final voyage to restore his reputation.

Vasco Nuñez de Balboa. The Mariners’ Museum and Park . Following in the Footsteps of Balboa. Smithsonian Magazine .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Explorer and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean.

(1475-1519)

Who Was Vasco Núñez de Balboa?

Explorer and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa helped establish the town of Darién on the Isthmus of Panama, becoming interim governor. In 1513, he led the first European expedition to the Pacific Ocean, but news of the discovery arrived after the king had sent Pedro Arias de Ávila to serve as the new governor of Darién. Ávila, reportedly jealous of Balboa, had him beheaded for treason in 1519.

Early Life and Exploration

Born in 1475 in Jerez de los Caballeros, in the province of Extremadura in Castile, Spain, Balboa went on to become the first European to see the Pacific Ocean.

At a time when many people in Spain were seeking their fortunes in the New World, Balboa joined an expedition to South America. After exploring the coast of present-day Colombia, Balboa stayed on the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). While there, he got into debt and fled, hiding away on a ship headed for the fledgling colony of San Sebastian.

Once he arrived at the settlement, Balboa discovered that most of the colonists had been killed by nearby ingenious people. He then convinced the remaining colonists to move to the western side of the Gulf of Uraba. They established the town of Darién on the Isthmus of Panama, which is a small strip of land that connects Central America and South America. Balboa became the interim governor of the settlement.

Seeing the Pacific Ocean

In 1513, Balboa led an expedition from Darién to search for a new sea reportedly to the south and for gold. He hoped that if he was successful, he would win the favor of Ferdinand, the king of Spain. While he didn't find the precious metal, he did see the Pacific Ocean and claimed it and all of its shores for Spain.

The news of the discovery arrived after the king had sent Pedro Arias de Ávila to serve as the new governor of Darién. The new governor was reportedly jealous of Balboa and ordered him to be arrested on charges of treason. After a brief trial, Balboa was beheaded on January 12, 1519, in Acla, near Darién, Panama.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Vasco Núñez de Balboa

- Birth Year: 1475

- Birth City: Jerez de los Caballeros, Extremadura, Castile

- Birth Country: Spain

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Explorer and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean.

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1519

- Death date: January 12, 1519

- Death City: Acla, near Darién

- Death Country: Panama

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

Biography of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Conquistador and Explorer

Heritage Images / Contributor / Getty Images

- Central American History

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Caribbean History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Back to the Darien

Santa maría la antigua del darién, expedition to the south, pedrarías dávila, vasco and pedrarías.

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475–1519) was a Spanish conquistador, explorer, and administrator. He is best known for leading the first European expedition to sight the Pacific Ocean , or the "South Sea" as he referred to it. He is still remembered and venerated in Panama as a heroic explorer.

Fast Facts: Vasco Núñez de Balboa

- Known For : First European sighting of the Pacific Ocean and colonial governance in what is now Panama

- Born : 1475 in Jeréz de los Caballeros, Extremadura province, Castile

- Parents : Differing historical accounts of parents' names: his family was noble but no longer wealthy

- Spouse : María de Peñalosa

- Died : January 1519 in Acla, near present-day Darién, Panama

Nuñez de Balboa was born into a noble family that was no longer wealthy. His father and mother were both of noble blood in Badajoz, Spain and Vasco was born in Jeréz de los Caballeros in 1475. Although noble, Balboa could not hope for much in the way of even a meager inheritance, as he was the third of four sons. All titles and lands were passed to the eldest; younger sons generally went into the military or clergy. Balboa opted for the military, spending time as a page and squire at the local court.

By 1500, word had spread all over Spain and Europe of the wonders of the New World and the fortunes being made there. Young and ambitious, Balboa joined the expedition of Rodrigo de Bastidas in 1500. The expedition was mildly successful in raiding the northeastern coast of South America. In 1502, Balboa landed in Hispaniola with enough money to set himself up with a small pig farm. He was not a very good farmer, however, and by 1509 he was forced to flee his creditors in Santo Domingo .

Balboa stowed away (with his dog) on a ship commanded by Martín Fernández de Enciso, who was heading to the recently-founded town of San Sebastián de Urabá with supplies. He was quickly discovered and Enciso threatened to maroon him, but the charismatic Balboa talked him out of it. When they reached San Sebastián they found that natives had destroyed it. Balboa convinced Enciso and the survivors of San Sebastián (led by Francisco Pizarro ) to try again and establish a town, this time in the Darién—a region of dense jungle between present-day Colombia and Panama.

The Spaniards landed in the Darién and were quickly beset by a large force of natives under the command of Cémaco, a local chieftain. Despite the overwhelming odds, the Spanish prevailed and founded the city of Santa María la Antigua de Darién on the site of Cémaco's old village. Enciso, as ranking officer, was put in charge but the men detested him. Clever and charismatic, Balboa rallied the men behind him and removed Enciso by arguing that the region was not part of the royal charter of Alonso de Ojeda, Enciso's master. Balboa was one of two men quickly elected to serve as mayors of the city.

Balboa's stratagem of removing Enciso backfired in 1511. It was true that Alonso de Ojeda (and therefore, Enciso) had no legal authority over Santa María, which had been founded in an area referred to as Veragua. Veragua was the domain of Diego de Nicuesa, a somewhat unstable Spanish nobleman who had not been heard from in some time. Nicuesa was discovered in the north with a handful of bedraggled survivors from an earlier expedition, and he decided to claim Santa María for his own. The colonists preferred Balboa, however, and Nicuesa was not even allowed to go ashore: Indignant, he set sail for Hispaniola but was never heard from again.

Balboa was effectively in charge of Veragua at this point and the crown reluctantly decided to simply recognize him as governor. Once his position was official, Balboa quickly began organizing expeditions to explore the region. The local tribes of indigenous natives were not united and were powerless to resist the Spanish, who were better armed and disciplined. The colonizers collected much gold and pearls through their military power, which in turn drew more men to the settlement. They began hearing rumors of a great sea and a rich kingdom to the south.

The narrow strip of land which is Panama and the northern tip of Colombia runs east to west, not north to south as some might suppose. Therefore, when Balboa, along with about 190 Spaniards and a handful of natives, decided to search for this sea in 1513, they headed mostly south, not west. They fought their way through the isthmus, leaving many wounded behind with friendly or conquered chieftains. On September 25, Balboa and a handful of battered Spaniards (Francisco Pizarro was among them) first saw the Pacific Ocean, which they named the “South Sea.” Balboa waded into the water and claimed the sea for Spain.

The Spanish crown, still with some lingering doubt over whether or not Balboa had correctly handled Enciso, sent a massive fleet to Veragua (now named Castilla de Oro) under the command of veteran soldier Pedrarías Dávila. Fifteen hundred men and women flooded the tiny settlement. Dávila had been named governor to replace Balboa, who accepted the change with good humor, although the colonists still preferred him to Dávila. Dávila proved to be a poor administrator and hundreds of settlers died, mostly those who had sailed with him from Spain. Balboa tried to recruit some men to explore the South Sea without Dávila knowing, but he was found out and arrested.

Santa María had two leaders: officially, Dávila was governor, but Balboa was more popular. They continued to clash until 1517 when it was arranged for Balboa to marry one of Dávila’s daughters. Balboa married María de Peñalosa despite an obstacle: she was in a convent in Spain at the time and they had to marry by proxy. In fact, she never left the convent. Before long, the rivalry flared up again. Balboa left Santa María for the small town of Aclo with 300 of those who still preferred his leadership to that of Dávila. He was successful in establishing a settlement and building some ships.

Fearing the charismatic Balboa as a potential rival, Dávila decided to get rid of him once and for all. Balboa was arrested by a squad of soldiers led by Francisco Pizarro as he made preparations to explore the Pacific coast of northern South America. He was hauled back to Aclo in chains and quickly tried for treason against the crown: The charge was that he had tried to establish his own independent fiefdom of the South Sea, independent from that of Dávila. Enraged, Balboa shouted out that he was a loyal servant of the crown, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. He was beheaded in January of 1519 along with four of his companions (there are conflicting accounts of the exact date of the execution).

Without Balboa, the colony of Santa María quickly failed. Where he had cultivated positive ties with local natives for trade, Dávila enslaved them, resulting in short-term economic profit but long-term disaster for the colony. In 1519, Dávila forcibly moved all of the settlers to the Pacific side of the isthmus, founding Panama City, and by 1524 Santa María had been razed by angry natives.

The legacy of Vasco Nuñez de Balboa is brighter than that of many of his contemporaries. While many conquistadors , such as Pedro de Alvarado , Hernán Cortés , and Pánfilo de Narvaez are today remembered for cruelty, exploitation, and inhuman treatment of natives, Balboa is remembered as an explorer, fair administrator, and popular governor who made his settlements work.

As for relations with natives, Balboa was guilty of his share of atrocities, including enslavement and setting his dogs on homosexual men in one village. In general, however, he is thought to have dealt with his native allies well, treating them with respect and friendship which translated into beneficial trade and food for his settlements.

Although he and his men were the first to see the Pacific Ocean while heading west from the New World, it would be Ferdinand Magellan who would get the credit for naming it when he rounded the southern tip of South America in 1520.

Balboa is best remembered in Panama, where many streets, businesses, and parks bear his name. There is a stately monument in his honor in Panama City (a district of which bears his name) and the national currency is called the Balboa. There is even a lunar crater named after him.

- Editors, History.com. “ Vasco Núñez De Balboa .” History.com , A&E Television Networks, 18 Dec. 2009.

- Thomas, Hugh. Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan. Random House, 2005.

- Biography of Diego de Almagro, Spanish Conquistador

- 10 Notable Spanish Conquistadors Throughout History

- 10 Facts About Francisco Pizarro

- Explorers and Discoverers

- Biography of Francisco Pizarro, Spanish Conqueror of the Inca

- A Timeline of North American Exploration: 1492–1585

- Biography and Legacy of Ferdinand Magellan

- Biography of Francisco de Orellana, Discoverer of the Amazon River

- The Pizarro Brothers

- The Capture of Inca Atahualpa

- Biography of Hernando Pizarro

- La Navidad: First European Settlement in the Americas

- The Legend of El Dorado

- Biography of Hernán Cortés, Ruthless Conquistador

- El Dorado, Legendary City of Gold

- Spain and the New Laws of 1542

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

Vasco Nunez de Balboa Facts and Story

Published: May 31, 2012 · Modified: Nov 11, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

Vasco Nunez de Balboa (c. 1475 – around January 12–21, 1519) was a Spanish Conquistador and governor. He is known for being the first European to discover the Pacific Ocean on a mission to try and find a spice trade route to Asia.

Balboa also accomplished founding the first permanent settlement on the mainland of the New World. His successes were cut short by his own ambitions and those of others as he was wrongfully accused and sentenced to death. Francisco Pizarro , the conquistador who conquered the Incas, oversaw his execution.

Santa Maria

Death and legacy.

Balboa was born in Spain around 1475. His family was of wealthy descent, which gave him privileges that many others did not have. He was well-educated, and he served as a page and squire to Don Pedro de Portocarrero. When he was 17 years old, Christopher Columbus set sail to find a route to the East. He believed that by sailing west, he would run into Asia, but Columbus had grossly miscalculated the size of the world and accidentally discovered a New World that he died believing to be India. Balboa grew up hearing these stories and was then convinced to sail to the New World in 1500 on Rodrigo de Bastidas' expedition. By the end of the expedition, Vasco de Nunez Balboa settled in Hispaniola and lived the life of a planter and pig farmer. This vocation was not successful for him, and he landed himself in debt.

To avoid his creditors, Balboa escaped to Santo Domingo by hiding in a barrel together with his dog in order to board a ship. Before the expedition arrived at San Sebastian de Uraba, Balboa was discovered aboard the ship and was threatened by Fernandez de Enciso to be left at the first desolate island they came across. Balboa was able to convince Enciso to allow to to stay aboard due to his knowledge of the region. This expedition would be the first time that Vasco de Nunez Balboa met Francisco Pizarro .

During this expedition, Balboa had gained a positive reputation. He was charismatic and showed great leadership ability. He displayed a keen sense of the region, which enabled the Spanish to move efficiently. He became extremely popular with the crew, but the commanding officer, Enciso, was disliked after a series of blunders that left many doubting his ability to command.

After finding the settlement of San Sebastian in utter ruin, Balboa suggested that the settlement be moved to a different region, the region of Darien. He believed that Darien offered more fertile soil and the natives were not as hostile. Upon arriving in the region of Darien, they found the natives waiting for them. Apparently, the natives were hostile, and a battle was fought between the natives and the Spanish. The Spanish were vastly outnumbered, but the natives had inferior technology. After a tough battle, the Spanish won an important victory. Balboa then established the first permanent settlement on the mainland of the New World and named it Santa Maria.

After the victory against the natives, Balboa's thoughts about the Darien region were proven correct. The natives of the area were relatively calm compared to the settlement of San Sebastian, and the land was fertile. This, coupled with his charisma, caused much of the crew to push for him to become Mayor of Santa Maria. The crew began to mutiny against the commanding officer Fernandez de Enciso, and the ambitious Balboa took advantage of it by removing Enciso. Balboa and Martin Samudio were appointed in the first election of the Americas as the municipal council of Santa Maria. After being elected to the municipal council, Balboa would become Governor of Veragua.

As Governor Balboa put Fernandez de Enciso on trial, stripped him of all his possessions, and sent him back to Hispaniola. With Enciso out of the picture, Balboa began to expedite the territories and quickly learned of another sea. He then organized an expedition to explore the isthmus of Panama in search of the South Sea and a quest for more riches. Balboa was sent for aid from Spain, but at this point, many had turned against him due to his actions against Enciso. Balboa decided to journey there on his own with a small amount of men. Through some hardships, Balboa reached the South Sea, thus discovering a new ocean that would later be named the Pacific Ocean due to its passive nature.

The discovery of the South Sea was an important discovery for the Spanish Empire:

- It confirmed the discovery of a New World. Even though the idea that Christopher Columbus had actually sailed to Asia was beginning to fade, the discovery of the Pacific Ocean allowed future explorers to plan their voyages differently.

- The Spanish could now prepare to establish a trade route to Asia that had been monopolized by the Portuguese up until this time.

Balboa's main mission was not to discover the Pacific Ocean but rather to find wealth in precious metals. He did so by ransacking any of the native peoples he came across. When he returned to Veragua, he returned a much wealthier man. Even so, he followed the law of Spain and sent the appropriate portion back to the Spanish Crown, along with news of his discovery.

The story of Vasco de Nunez Balboa ended tragically. After making major discoveries and successfully leading economic reforms that increased the wealth of the colonies that he oversaw, he was always in constant conflict with inferior minds but with greater last names. He married the daughter of Predrarias, one of his rivals, and seemed to become close to him. Pedrarias gave Balboa permission to continue his expeditions of the South Sea, but while on an expedition, Balboa received a series of kind letters from Pedrarias asking him to come home immediately. Balboa, suspecting nothing, quickly obeyed. While returning, he was confronted by Francisco Pizarro and accused of trying to usurp Pedrarias' power. Balboa denied all charges and requested a trial in Spain, but Pedrarias and Martin Enciso quickly tried him in the New World. Balboa was found guilty and sentenced to beheading, which was carried out immediately.

Balboa was one of the greatest minds. He, along with Cortes, were more than just Conquistadors as they understood how to run a nation. His economic reforms caused a boom in the economy, which allowed him to acquire great wealth. Unfortunately, greed and those jealous of his successes betrayed him.

- Vasco Nunez de Balboa

- John Cabot

- Jacques Cartier

- Samuel de Champlain

- Christopher Columbus

- Sir Francis Drake

- Vasco da Gama

- Henry Hudson

- Juan Ponce de Leon

- Lewis & Clark

- Ferdinand Magellan

- Francisco Pizarro

- Hernando de Soto

- Amerigo Vespucci

- Treasure Hunts

- Webquest Instructions

- Copyright Notice

- Content Notice

- Privacy Policy

- All About the Authors

Vasco Nunez de Balboa

Vasco Nunez de Balboa

Born in or near the year 1457, the Spanish explorer Vasco Nunez de Balboa was the first European to see the eastern shore of the Pacific Ocean. He sighted the ocean in 1513 from a mountaintop in what is now Panama. Upon reaching the shore, Balboa waded into the ocean and claimed it and all its shores for Spain.

Balboa was born in Jerez de los Caballeros, Mexico. As a young boy, Balboa had two dreams: to be a famous explorer and to be an Olympic fencing champion. His Olympic dream never materialized, but his ability with the sword was to serve him well in battles throughout his career.

Following the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492, Balboa joined an expedition to South America in 1501. One year later Balboa found himself on the island of Hispaniola trying without success to make a living as a pig farmer. It seems that the native Indian population worshipped the pig as a god and neither they nor the Spanish settlers would eat an animal thought to be a god, no matter how tasty.

The Voyages of Vasco Nunez de Balboa (Click to enlarge)

Several years later, in 1510, Balboa enjoyed a change in fortune when he became acting governor of Darien. From there he led expeditions into Panama, conquering some Indians while allowing other, more friendly, Indians to open gambling casinos. In 1511 friendly Indians told Balboa of a land called Tubanama where he could find much gold. The Indians told him this land was located across the mountains near a great sea.

Hoping to please King Ferdinand of Spain with an exciting discovery, in early September 1513, Balboa led an expedition from Darien. The Panama Canal was temporarily closed due to a strike by native workers, so Balboa and his 190 Spanish followers were forced to take the difficult land route. After a three week journey, during which the expedition lost all radio contact with their home base, Balboa found the great sea he had longed to see: the Pacific Ocean!

Sadly, Balboa was to live only a few more years. A jealous rival falsely accused Balboa of treason to the king, and in January 1519, he was tried and sentenced to death. He was publicly beheaded in the town of Acla in Panama, which he had established only a year earlier. Fortunately, Balboa’s children were not left penniless because they were able to sell their father’s game-used armor, the same armor that their famous father wore when he waded into the Pacific Ocean, on eBay.com for a tidy sum.

Click here for other places to learn about this explorer

This page last updated on Apr 11, 2017

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

© 2006–2024 All About Explorers. All rights reserved.

Following in the Footsteps of Balboa

The first European to glimpse the Pacific from the Americas crossed Panama on foot 500 years ago. Our intrepid author retraces his journey

Juan Carlos Navarro delights in pointing out that John Keats got it all wrong in his sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.” The Romantic poet, he says, not only misidentified the first European to glimpse the Pacific Ocean, but his account of the mountain looming over a tropical wilderness in what is now Panama was, by any stretch, overly romantic.

Navarro, an environmentalist who served two terms as the mayor of Panama City and is the early favorite in his country’s 2014 presidential elections, notes that it was actually the Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa who did the glimpsing, and that countryman Hernán Cortés—the cutthroat conqueror of the Aztec Empire—wasn’t even in the neighborhood during the 1513 isthmus crossing.

Nor was the peak—Pechito Parado—technically in Darién, the first permanent mainland European settlement in the New World. “Today, the Darién is a sparsely populated region of Panama,” says Navarro, the only presidential candidate who has ever campaigned there. “In Balboa’s day, it was just a town—Santa María la Antigua del Darién—on the Caribbean side.”

Of all the inaccuracies in the sestet, the one Navarro finds the most laughable is the reaction of the expedition party after spotting the Pacific, which, to be persnickety, Balboa named Mar del Sur (the South Sea). “The look of the men hardly could have been one of ‘wild surmise,’” Navarro says, disdainfully. “Before starting his journey, Balboa knew pretty much what he’d discover and what he could expect to find along the way.”

The same can’t be said for my own Darién adventure, a weeklong trudge that’s anything but poetry in motion. As Navarro and I lurch up Pechito Parado on this misty spring morning, I realize it isn’t a peak at all, but a sharply sloped hillock. We plod in the thickening heat through thorny underbrush, across massive root buttresses and over caravans of leaf-cutter ants bearing banners of pale purple membrillo flowers. The raucous bark of howler monkeys and the deafening cry of chicken-like chachalacas are constant, a Niagara of noise that gushes between the cuipo trees that tower into the canopy. The late humorist Will Cuppy wrote that the howl of the howler was caused by a large hyoid bone at the top of the trachea, and could be cured by a simple operation on the neck with an ax.

“Imagine what Balboa thought as he hiked through the rainforest,” says Navarro while pausing beside the spiny trunk of a sandbox tree, whose sap can cause blindness. “He had just escaped from the Spanish colony of Hispaniola—the island that comprises present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic—an arid, spare place with a rigid system of morality. He lands in a humid jungle teeming with exotic wildlife and people who speak a magical, musical language. He’s told that not far off are huge amounts of gold and pearls and an even huger sea. He probably thought, ‘I’m gonna be rich!’ For him, the Darién must have been mind-blowing.”

This month marks the 500th anniversary of the exploration that not only blew Balboa’s mind, but eventually caused him to lose his head. (Literally: Based on false charges brought by Pedro Arias Dávila, the father-in-law who had displaced him as governor of Darién, Balboa was decapitated in 1519.) The occasion is being celebrated with great fanfare in Panama City, where the crossing was a theme of this year’s annual carnival. Nearly a million people took part in the five days of spectacles, which featured a 50-float parade, 48 conga-dancing groups and 10 culecos —enormous trucks that blast music and drench spectators with (somewhat inaptly) tap water.

While conquistadors like Cortés and Francisco Pizarro are reviled throughout Latin America for their monstrous cruelty, the somewhat less ruthless but equally brutal Balboa (he ordered native chieftains to be tortured and murdered for failing to bend to his demands, and gay indigenes to be torn to pieces by dogs) is revered in Panama. Statues of the explorer abound in city parks, coins bear his likeness, the currency and the nation’s favorite beer are named for him, and the Panama Canal’s final Pacific lock is the Port of Balboa.

As depicted in Balboa of Darién , Kathleen Romoli’s indispensable 1953 biography, the Spanish-born mercenary was as resourceful as he was politically naïve. Balboa’s greatest weakness, she observed, was his “lovable and unfortunate inability to keep his animosities alive.” (He underestimated Dávila even after Daddy-in-Law Dearest had him put under house arrest, locked him in a cage and ordered his head to be chopped off and jammed on a pole in the village square.)

Navarro argues that Balboa’s relatively humane policies toward indigenous people (befriending those who tolerated his soldiers and their gold lust) put him several notches above his fellow conquistadors. “He was the only one willing to immerse himself in the native culture,” says Navarro. “In Panama, we recognize the profound significance of Balboa’s achievement and tend to forgive his grievous sins. He was consumed by ambition and lacking in humanity and generosity. Was he guilty of being part of the Spanish power structure? He was guilty as hell. He was also an authentic visionary.”

Navarro has been following in Balboa’s bootsteps since the summer of 1984. He had graduated from Dartmouth College and was about to begin a master’s program in public policy at Harvard University. “Balboa was my childhood hero, and I wanted to relive his adventure,” he says. “So my older brother Eduardo and I got some camping gear, hired three Kuna Indian guides and started from the Río Aglaitiguar. When we reached the mountains at dawn on the third day, the guides warned us that evil spirits inhabited the forest. The Kuna refused to go farther. For the final nine days we had to muddle through the jungle on our own.”

I accompanied Navarro on his second traverse, in 1997. He was then 35 and running the National Association for the Conservation of Nature (Ancon), the privately funded nonprofit he started that became one of the most effective environmental outfits in Central America. In defense of the Darién, he prevailed against powerful lumber barons, getting tariffs on imported lumber abolished; lobbied successfully for the creation of five national parks; and discouraged poaching by setting up community agro-forestry farms. On his watch, Ancon bought a 75,000-acre cattle ranch that bordered the Gulf of San Miguel and turned it into Punta Patiño, Panama’s first and still largest private nature preserve. Now 51 and the presidential candidate of the Partido Revolucionario Democrático (PRD), he’s a bit rounder around the middle and his face has some well-earned lines, but his enthusiasm is scarcely diminished. “Despite the atrocities Balboa committed,” Navarro says, “he brought to the Darién an attitude of discovery and empathy and wonderment.”

The leader of our last Darién Gap trek was ANCON naturalist Hernán Arauz, son of Panama’s foremost explorer and its most accomplished anthropologist. Affable, wittily fatalistic and packed with a limitless fund of Balboa lore, he shepherds hikers through ant swarms and snake strikes while plying a machete the size of a gatepost. Alas, Arauz can’t escort me this time around, and Navarro is unable to join the expedition until Pechito Parado. As a consolation, Arauz leaves me with the prayer a dying conquistador is said to have chiseled in rock in the Gulf of San Miguel: “When you go to the Darién, commend yourself to the Virgin Mary. For in her hands is the way in; and in God’s, the way out.”

Ever since Balboa took a short walk across a long continent, the swamp forests that fuse the Americas have functioned as a gateway. They’re also a divider, forming a 100-mile strip that’s the only break between the northern section of the 30,000-mile Pan-American Highway, which starts in Alaska, and the southern part, by which you can drive to the Strait of Magellan. Half a millennium later, there’s still no road through the territory.

When Balboa made his 70-mile slog through this rough country, he was governor of Darién. Sure that he would provide the Spanish a faster passage to the spices of the Indies, he had petitioned King Ferdinand for men, arms and provisions. While awaiting a response, the conquistador—having crushed a plot by local natives to burn Santa María la Antigua del Darién, and held a settler insurrection at bay—not-so-wildly surmised that intriguers in Seville were scheming to have him recalled. He set off on September 1 with a force of 190 heavily armed Spaniards and hundreds of Native American warriors and porters, some of whom knew the way.

Today, Santa María no longer exists. The colonial town was abandoned soon after Balboa’s beheading, and, in 1524, was burned down by the indigenous people. The area is now a refuge for Colombian guerrillas known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Which is why we launch the trek in Puerto Obaldia, a tiny village some 30 miles north, and why the frontier police that accompany us wear bandoleers and shoulder M-16s and AK-47s.

Our small retinue is drawn from the three cultures of the region: Chocó, Afro-Darienite and Kuna, whose village of Armila is the first along the trail. The Kuna are notoriously generous and hospitable. They hold a spontaneous evening jam session, serenading my party with maracas, pan flutes and song. We all join in and toast them with bottles of Balboa beer.

The following morning I befriend a scrawny, tawny junkyard dog, one of the many strays that scavenge the Armila streets. I wonder if he could have possibly descended from Leoncico, the yellow mutt that, in 1510, famously stowed away with Balboa on a ship bound for the Darién. Sired by Becerrillo, the warrior dog of Juan Ponce de León, Leoncico was so fierce that Balboa later awarded him a bowman’s pay and a gold collar. This pooch doesn’t look lively enough to chase a paperboy.

I wish I could say as much for Darién insects. Into the rainforest I have brought reckless optimism, a book on native birds and what I had hoped was enough bug spray to exterminate Mothra. I miscalculated. As I slog through the leaf litter on the forest floor, the entire crawling army of the jungle seems to be guarding it: Mosquitoes nip at my bare arms; botflies try to burrow into them; fire ants strut up my socks and ignite four-alarm blazes. Bullet ants are equally alarming. Of all the world’s insects, their sting is supposed to be the most painful. Arauz’s secret to knowing when marauding soldier ants are on the move? The sweet bell tones of antbirds that prey on them fleeing a swarm.

Darién wildlife is spectacularly varied. We chance upon an astounding array of mammal tracks: tapirs, pumas, ocelots and white-lipped peccaries, a kind of wild hog that roves in herds of up to 200. In case of a peccary charge, Arauz suggested that I climb at least eight feet up in a nearby tree since they reputedly have the ability to piggyback. “I know of a hunter who shared a tree with a jaguar while a pack passed beneath them,” he told me. “The hunter swore the worst part was the smell of the cat’s intestinal gas.”

At a Chocó encampment, we dine on peccary stew. I remember Arauz’s yarn about a campfire meal his parents had with the Chocó on the National Geographic Society’s 1960 trans-Darién expedition. His dad looked into a pot and noticed a clump of rice bubbling to the surface. He looked a little closer and realized the rice was embedded in the nose of a monkey. The Chocó chef confided that the tastiest rice was always clenched in the monkey’s fist. “Too late,” Arauz said. “My father had already lost his appetite.”

Through a translator, I recite the tale to our Chocó chef. He listens intently and, without a tickle of irony, adds that the same monkey would have yielded three pints of cacarica fruit punch. It turns out Chocós have a delicious sense of humor. I know this because one of our Chocó porters laughs uproariously whenever I try to dismantle my tent. I laugh uneasily when he shows me the three-foot pit viper he has hacked in half beside my backpack.

The jungle air is heavy and moist; the tropical sun, unrelenting. When the Darién gets too dense to chop through with machetes, our guides navigate like sailors in a fog, with a compass, counting their steps to measure how far we’ve gone and when to change directions. We average seven or eight miles a day.

During the homestretch I cheat a little—OK, a lot—by riding in a piragua. With Navarro in the prow, the motorized dugout cruises past the patchwork of cornfields and pastures that have supplanted Balboa’s jungle. Sandbanks erupt in butterfly confetti as our canoe putters by. Balboa foraged through this countryside until September 25 (or possibly the 27th—the facts in the travel records don’t match), when his procession reached the foot of Pechito Parado. According to legend, he and Leoncico clambered up the rise together, conquistador and conquistadog. From a hilltop clearing Balboa looked south, saw a vast expanse of water and, dropping to his knees, raised eyes and arms heavenward. Then he called his men to join him. Erecting a pile of stones and a cross (“Balboa would understandably build something the size of his ego,” allows Navarro), they sang a Catholic hymn of thanksgiving.

No monument marks the spot of Balboa’s celebrated sighting. The only sign of humanity is a circle of stones in which a Bible, sheathed in plastic, lays open to the Book of Matthew. Having summited the historic peak, I, too, raise my fists in exultation. Rather than commend myself to the Virgin Mary, I peer at the cloudless sky and repeat a line from a 20th-century Balboa: “Yo, Adrian!”

If Balboa had a rocky start, he had a Rocky finish. On September 29, 1513—St. Michael’s Day—he and 26 handpicked campañeros in full armor marched to the beach. He had seen breakers from afar, but now an uninviting sand flat stretched for a mile or more. He had muffed the tides. Obliged to at least stand in ocean he was about to own, Balboa lingered at the sea’s edge till the tide turned. “Like a true conqueror,” Navarro observes, “he waited for the ocean to come to him.” When it finally did, Balboa waded into the salty waters of the gulf he would name San Miguel. Brandishing a standard of Madonna in his right hand and a raised sword in his left, he claimed the whole shebang (not quite knowing exactly how big a shebang it was) for God and Spain.

My own party skips the beachhead. Hopping aboard the piragua, Navarro and I head for the backwater settlement of Cucunati. For three years Navarro has been canvassing voters across Panama, from the big, shiny cities to frontier outposts where no presidential hopeful has gone before. At an impromptu town meeting in Cucunati, residents air their frustrations about the lack of electricity, running water and educational funding. “One out of four Panamanians live in poverty, and 90 percent of them live in indigenous comarcas ,” Navarro later says. “The conditions in these rural communities are not unlike what Balboa encountered. Unfortunately, the Indians of the Darién are not on the government’s radar.”

On a boat to the Punta Patiño reserve, Navarro points out the gumbo limbo, nicknamed the turista tree because its burnt umber bark is continually peeling. Nearby is a toothpaste tree, so named because it oozes a milky sap that has proven to be an effective dentifrice when used in a conscientiously applied program of oral hygiene and regular professional care. Twined around an enormous cuipo is a strangler fig. “I call this fig a politician tree,” says Navarro. “It’s a parasite, it’s useless and it sucks its host dry.”

Five hundred years after Balboa led a straggle of Spanish colonialists from the Caribbean across to the Pacific, the wilderness he crossed is imperiled by logging, poaching, narco-trafficking and slash-and-burn farming. “The biggest obstacle is 500 years of neglect,” says Navarro, who, if elected, plans to seat an Indian leader in his cabinet, transfer control of water treatment and hydroelectric plants to local government, and form a new agency to guarantee sustained investment in indigenous areas.

None of the native peoples Balboa encountered in 1513 exist in 2013. The current inhabitants migrated to the Darién over the last several hundred years. “Diseases and colonial wars brought by the Europeans basically wiped out the Indian populations,” says Navarro. The tragic irony was that the Spanish conquest helped preserve the rainforest. “The Indians had stripped much of the jungle to plant corn. In a strange way, the human holocaust Balboa unleashed was the Darién’s salvation.” The conquistador, he says, was an accidental greenie.

Nested inside Arauz’s home on the outskirts of Panama City are the weird and wonderful oddities he and his parents accumulated during their travels in the Darién. Among the bric-a-brac is a tooth from a giant prehistoric shark that once cruised the channels, a colorful mola (cloth panel) bestowed on his mother by a Kuna chief and a Spanish soldier’s tizona (El Cid’s signature sword) Hernán bought off a drunk in the interior. Arauz particularly prizes a photo album devoted to the 1960 trans-Darién expedition. He was, after all, conceived during the journey.

On the walls of his living room are 65 original maps and engravings of the Caribbean from five centuries; the earliest dates to 1590. Many are as cartographically challenged as a Keats poem. Some show the Pacific in the east, a mistake that’s easy to make if you think the earth is flat. Others ignore all inland features, focusing entirely on coastlines. One rendering of the Gulf of Panama—which Balboa once sailed across—features a grossly oversize Chame Point peninsula, an error perhaps deliberately made by Dutch surveyors feeling heat to come up with something fresh to justify their expense accounts.

Arauz masterfully applies his jungle know-how to antique maps of the Darién. Three years ago the Library of Congress awarded him a research fellowship. While in Washington, D.C., he spent a lot of time gazing at the Waldseemüller Map, a 12-section woodcut print of the world so old that the intended users’ biggest concern would have been sailing over the edge of it. Published at a French monastery in 1507—15 years after Columbus’ first voyage to the New World—the chart casts serious doubt on Balboa’s claim.

The Waldseemüller Map was the first to show a separate continent in the Western Hemisphere and to bear the legend “America.” It suggests that Portuguese navigators first explored the west coast of South America and ventured north as far as Acapulco. The shoreline of Chile is rendered so accurately that some believe it must have been based on firsthand knowledge.

Even if it were, argues Arauz, the navigators didn’t discover anything. “Discovery implies uncovering and making the world aware,” he insists. “Had the date been correct, the Spanish Crown would have certainly known about it. They were quite good at cartographic spying and ferreting out the geographical knowledge of rival nations.”

The Spanish kept a large secret map called the Padrón Real in Seville that was updated as soon as each expedition returned. This master schema of the known world was used as a treasure map to the world’s riches. “As late as 1529, the Chilean coast didn’t appear on the Padrón Real,” says Arauz, with the most mischievous of grins. “That tells me Balboa really was the Man—that, atop Pechito Parado, he spied the Pacific before any other European.”

The conquistador had left his mark. He had—one could safely say—put himself on the map.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Franz Lidz | READ MORE

A longtime senior writer at Sports Illustrated and the author of several memoirs, Franz Lidz has written for the New York Times since 1983, on travel, TV, film and theater. He is a frequent contributor to Smithsonian .

Legends of America

Traveling through american history, destinations & legends since 2003., vasco nunez de balboa – spanish explorer.

Vasco Nunez de Balboa.

Vasco Nunez de Balboa, a Spanish conquistador and explorer, was the first European to see the eastern part of the Pacific Ocean in 1513 after crossing the Isthmus of Panama. Balboa was born in Jerez de Los Caballeros, Spain, to the nobleman Nuño Arias de Balboa and Lady de Badajoz in about 1475. Little is known of his early childhood except that he was the third of four boys in his family. During his adolescence, he served as a page and squire to Don Pedro de Portocarrero, Lord of Moguer.

Motivated by his master, after the news of Christopher Columbus ‘ voyage to the New World became known, he embarked on his first voyage to the Americas, along with Juan de la Cosa, on Rodrigo de Bastidas’ expedition. Bastidas had a license to bring back treasure for the king and queen while keeping four-fifths for himself. In 1501, he crossed the Caribbean coasts from the east of Panama along the Colombian coast and through the Gulf of Uraba toward Cabo de la Vela. The expedition continued to explore the northeast of South America until they realized they did not have enough men and sailed to the Caribbean Island of Hispaniola. In 1510, Balboa and his dog, Leoncio, stowed away on a boat going from Santo Domingo to San Sebastian. When they arrived at San Sebastian, they discovered that it had been burned to the ground. Balboa convinced the others to travel southwest with him to a spot he had seen on his earlier expedition. In 1511, Balboa founded a colony, the first European settlement in South America – the town of Santa Maria de la Antigua del Darien in present-day Panama. He soon married the daughter of Careta, the local Indian chief. Soon after, in 1513, he sailed with hundreds of Spaniards and Indians across the Gulf of Uraba to the Darien Peninsula.

Balboa and his men, including Francisco Pizarro, then traveled to the ocean, claiming it and all that touched it for Spain. Once they reached the Pacific Ocean, Balboa and his men found gold and pearls, which Balboa decided to send back to King Ferdinand of Spain. However, before news of Balboa’s accomplishment reached Spain, King Ferdinand appointed an elderly nobleman, Pedrarias Davila, to be the new governor of Darien. Once the King learned of Balboa’s discovery of the Pacific Ocean, he appointed Balboa to serve under Davila as governor of Panama. Unfortunately for Balboa, Pedrarias Davila was a jealous man who did not like seeing the growing popularity and influence that Balboa was developing. In 1518, Governor Davila falsely accused Balboa of treason, had him arrested, ordered a speedy trial, and sentenced Balboa to death. In January 1519, Balboa and four friends were beheaded.

Compiled by © Kathy Alexander / Legends of America , updated April 2024.

American History

Discovery and Exploration of America

Exploration of America

The Spanish Explore America

- Articles, Media, and References

- Poetry & Lyrics

- Voices That Guide Us

- Register for the Teacher’s Forum

- Effectiveness

- Parents & Grandparents

- Street Team Civics

- Street Team INNW, Long Beach

- Street Team 2020

- Street Team INNW, Mt. Zion

- Street Team INNW, St. Paul

- Street Team HD Challenge

- Street Team International

- Street Team Sweden

- Street Team Ghana

- Goals & Outcomes

- Smart Practices

- Annual Report

- Our Partners

- Donation Support

- Volunteer/Intern/Employment

- Your Community

- Donate to AA Registry

- Frances McHie Nursing Scholarship

Today's Articles

People, locations, episodes, vasco de balboa, explorer, and slave trader born.

Vasco Balboa

*The birth of Vasco Balboa is affirmed on this date in c. 1475. He was a Spanish explorer, slave trader, governor, and conquistador.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa was born in Jerez de los Caballeros, Spain. He was a descendant of the Lord mason of the Balboa castle, on León and Galicia's borders. His mother was the Lady de Badajoz, and his father was the hidalgo (nobleman), Nuño Arias de Balboa. Vasco's early childhood shows that he was the third of four boys in his family. During his adolescence, he served as a page and squire.

In 1500, after the news of Columbus's voyages to the New World became known, he decided to become an explorer. He embarked on his first voyage to the Americas on Rodrigo de Bastidas' expedition. Bastidas had a license to bring back treasure for the King and queen while keeping four-fifths for himself, under a policy known as the Quinto real, or "royal fifth." In 1501, he engaged in the middle passage. He crossed the Caribbean coasts from the east of Panama along the Colombian coast. The expedition continued to explore the northeast of South America until they realized they did not have enough men and sailed to Hispaniola. With his share of the earnings from this campaign, Balboa settled there in 1505. He resided as a planter and pig farmer; he was unsuccessful and abandoned life on the island.

In 1509, wishing to escape his creditors in Santo Domingo, Balboa set sail as a stowaway, hiding on the expedition of Nueva Andalucía. Before the journey arrived, Fernández de Enciso discovered Balboa aboard the ship and kept him aboard. Pizarro started preparations for the return to Hispaniola when Enciso arrived. Balboa had gained popularity among the crew because of his charisma and his knowledge of the region. By contrast, Fernández de Enciso was not well-liked by the men. At that point, the rivalry between Balboa and Pedrarias ceased abruptly due to the intercession of Bishop de Quevedo and Isabel de Bobadilla, who arranged for Balboa's marriage to María de Peñalosa, one of Pedrarias' daughters, who was in Spain.

The friendship between Pedrarias and Balboa lasted barely two years. Balboa wished to continue exploring the South Sea; Pedrarias finally consented to let Balboa go on his new expedition, giving him a license to study for a year and a half. In 1519, Balboa moved to Acla with 300 men and built new ships using the native and African slaves' workforce. He traveled to the Balsas River (Río Balsas), where he had four ships built. On his return, Pedrarias wrote warm letters urging Boats to meet him as soon as possible. Balboa quickly obeyed. Halfway to Santa María, he encountered a group of soldiers commanded by Francisco Pizarro, who arrested him in the governor's name. The latter took Pedrarias' power and create a separate government in the South Sea.

Balboa's trial began in January 1519, and Espinosa sentenced him to death by decapitation on the fifteenth of that month. Four of Balboa's friends accused as accomplices received the same fate. The sentence was carried out in Acla to show that the conspiracy had its roots in that colony. As Balboa and others were being led to the block, the town crier announced: "This is the justice that the King and his lieutenant Pedro Arias de Ávila impose upon these men, traitors, and usurpers; of the Crown's territories." Balboa could not restrain his indignation and replied: "Lies, lies! Never have such crimes held a place in my heart; I have always loyally served the King, with no thought in my mind but to increase his dominions."

Pedrarias observed the execution, hidden behind a platform. The executioner beheaded Balboa and his four friends with an ax. The final location of Balboa's remains is unknown, partly because there is no record of what happened in Acla after the execution on January 15, 1519. He is best known for crossing the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to lead an expedition to see or reach the Pacific from the New World. Gaspar de Espinosa, Pedrarias' underling, sailed the South Sea aboard the very ships that Balboa had commissioned. In 1520, Ferdinand Magellan renamed the sea the Pacific Ocean because of its calm waters.

Black Presence.co.uk

History.com

Related Videos:

The registry by subject.

- STEM / Medicine

- Theatre / The Arts

- Politics / Military / Law

- Activist / Abolitionist

- Sports / Outdoors

- Youth Views

Today’s Stories

- Kenneth Kaunda, Politician and Teacher born

- Henry Lowry, Lumbee Outlaw, born

- Reuben Shipley, Oregon Farmer born

- The Garifuna Community, a story

- Belle Davis, Vaudeville Singer born

- Lari Gilges, Black German Actor born

- The Boondocks (Sitcom) is Published

- Muhammad Ali Refuses His Vietnam Draft Notice

- The First ‘Festa Confederada’ is Celebrated

- Jewel Stradford, Lawyer born

- Needham Roberts, Soldier born

- William Hall, Mariner born

- Sally Hemings, Domestic Servant born

- A Ship Propeller is Patented by a Black Man

- ‘Bullet Joe’ Rogan, Baseball Player born

- William Crogman, Educator born

- Jeremiah Haralson, Politician born

New Poem Each Day

Poetry corner.

- Vasco Núñez de Balboa

John Florens | Dec 28, 2022

Table of Content

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (Jerez de los Caballeros, province of Badajoz, ca. 1475 - Acla, present-day Panama, January 15, 1519) was a Spanish adelantado, explorer, ruler and conqueror. After being Andrés Contero, the first European to spot the Pacific Ocean from a cliff on its eastern coast, he was the first to take possession of those lands and the first European to have founded a stable city on the mainland of the New World.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa was born around 1475 in the town of Jerez de los Caballeros, near Badajoz, and belonged to the Order of Santiago.

The surname Balboa comes from the castle of Balboa, near Villafranca del Bierzo, in the current province of León (Spain). It is believed that his father was the nobleman Álvaro Núñez (or Martínez) de Balboa, but almost nothing is known about the identity of his mother. He had at least three brothers: Gonzalo, a notary, Juan and Álvaro. Little is known with certainty about his childhood, except that he learned to read and write, unlike other Spanish conquistadors.

During his adolescence he served as page and squire of Pedro Portocarrero, VIII lord of Moguer, with whom he lived in the Castle of Moguer, during the preparations and development of the voyage of discovery. He also lived in Cordoba and had a house in Seville.

In 1500, encouraged by his master and the news of the voyages of Christopher Columbus and other navigators to the New World, he decided to enlist in the expedition of Rodrigo de Bastidas to the Caribbean Sea. Following Bastidas and his pilot Juan de la Cosa, in 1501 he traveled the coasts of the Caribbean Sea from the east of Panama, passing through the Gulf of Urabá, to Cape Vela (present-day Colombia). The ships finally set course for the island of Hispaniola, where one of them was shipwrecked.

Balboa, with the profits obtained in that campaign, bought land on the island and lived there for several years, farming and raising pigs. But he did not have much luck in this activity: the weather was adverse, as it was an area very exposed to hurricanes; the island's inhabitants were immersed in poverty, and wild pigs represented competition for his products. Balboa began to fall into debt and as he began to be pursued by his creditors, he finally saw no other way out but to flee the island.

In 1508, King Ferdinand the Catholic submitted the conquest of Tierra Firme to a contest. Two new governorships were created in the lands between the capes of La Vela (present-day Colombia) and Gracias a Dios (currently on the border between Honduras and Nicaragua). The Gulf of Urabá was taken as the limit of both governorships: Nueva Andalucía to the east, governed by Alonso de Ojeda, and Veragua to the west, governed by Diego de Nicuesa.

In 1509, wanting to get rid of his creditors in Santo Domingo, Núñez de Balboa embarked as a stowaway inside a barrel in the expedition commanded by the bachelor and mayor of Nueva Andalucía, Martín Fernández de Enciso, taking with him his dog Leoncico, who was the son of a dog Juan Ponce de León. He took with him his dog Leoncico, who was the son of a dog belonging to Juan Ponce de Leon. Fernandez de Enciso was on his way to help Governor Alonso de Ojeda, who was his superior.

Ojeda, along with seventy men, had founded the settlement of San Sebastián de Urabá in Nueva Andalucía. However, near the settlement there were many warlike Indians who used poisonous weapons, and Ojeda had been wounded in the leg. Shortly thereafter, Ojeda retreated on a ship to Hispaniola, leaving the settlement in charge of Francisco Pizarro, who at the time was no more than a soldier waiting for Enciso's expedition to arrive. Ojeda asked Pizarro to remain with a few men for fifty days in the settlement, or else use all means to return to Hispaniola.

Before the expedition arrived at San Sebastian de Uraba, Fernandez de Enciso discovered Nunez de Balboa aboard the ship and threatened to leave him on the first desert island he found. But many of the crew members spoke in favor of Balboa, whom they knew, and the bachelor was convinced of the usefulness of the stowaway's knowledge in that region, which he had explored eight years earlier. For this reason, he spared his life and allowed him to stay on board. Upon arriving at his destination, Enciso's ship ran aground and the credential that accredited the powers granted to Enciso was lost. This would later allow Balboa to challenge Enciso's authority.

After the fifty days stipulated by Ojeda had passed, Pizarro began to mobilize to return to Hispaniola, when the vessel of Fernandez de Enciso arrived. The bachelor, using his powers as mayor, ordered the return to San Sebastian. This caused surprise among his men because the town was totally destroyed, and also the Indians were waiting for them and began to attack without rest.

Due to the danger of the territory, Núñez de Balboa suggested that the town of San Sebastián be moved to the Darién region, to the west of the Gulf of Urabá, where the land was more fertile and the indigenous people were less bellicose. Fernández de Enciso accepted this suggestion. Later, the regiment moved to Darien, where the cacique Cemaco was waiting for them, together with 500 combatants ready for battle. The Spaniards, fearful of the large number of combatants, made a vow before the Virgin of Antigua de Sevilla, that if they were victorious in the battle, they would give their name to a town in the region. The battle was very close for both sides, but by a stroke of luck the Spaniards were victorious.

Cemaco, who was lord of the region, abandoned the town along with his fighters to the jungle of the interior. Then the Spaniards decided to loot the houses and gathered a large booty consisting of gold jewelry. In exchange, Núñez de Balboa made a vow promise and founded in December 1510 the first permanent settlement in continental America, Santa María la Antigua del Darién.

The triumph of the Spaniards over the Indians and the subsequent foundation of Santa María la Antigua del Darién, now located in a relatively calm place, gave Vasco Núñez de Balboa authority and consideration among his companions. His supporters described Martin Fernandez de Enciso as a despot and miser for the restrictions he took against gold, which was the object of greed of the colonists.

Núñez de Balboa took advantage of the situation by becoming a spokesman for the disgruntled colonists and succeeded in removing Fernández de Enciso from the position of ruler of the city. For this he used as an argument that the new city of Antigua was no longer in the government of Ojeda, which ended in the Gulf of Urabá, but in the government of Diego de Nicuesa. Fernández de Enciso, as Ojeda's lieutenant, therefore had no jurisdiction in that territory. After the dismissal, an open town council was established and a municipal government was elected (the first in the American continent), and two mayors were appointed: Martín Zamudio and Vasco Núñez de Balboa.

Shortly after, a flotilla headed by Rodrigo Enrique de Colmenares arrived in Santa María de la Antigua, whose objective was to find Nicuesa, who was also in trouble somewhere in the north of Panama. When he learned of the facts he persuaded the settlers of the city that they should submit to Nicuesa's authority, since they were in his governorship; Enrique de Colmenares invited two representatives that the Cabildo would name to travel with his flotilla and offer Nicuesa control of the city. The two representatives were Diego de Albites and Diego del Corral.

Enrique de Colmenares found Nicuesa badly wounded and with few men near Nombre de Dios, due to a skirmish he had had with indigenous people of that region. After being rescued, the governor heard the story of the battle with the cacique Cémaco and the foundation of Santa María, and decided to head to the city to impose his authority, since he considered the acts of Enciso and Balboa as an intrusion in his jurisdiction of Veraguas.

The representatives of Santa Maria were persuaded by Lope de Olano, who was imprisoned along with several disgruntled prisoners, that they would be making a grave mistake if they handed over control to Nicuesa, who was described as greedy and cruel, and who was capable of destroying the prosperity of the new city. With these arguments, de Albites and del Corral fled to the Darien before Nicuesa arrived and informed both Núñez de Balboa and the rest of the municipal authorities of the governor's intentions.

When Nicuesa arrived at the port of the city, a crowd appeared and a riot broke out, preventing the governor from disembarking in the city. Nicuesa insisted on being received no longer as governor, but as a simple soldier, but still the colonists refused to allow him to disembark in the city. Instead, he was forced to board a ship in poor condition and with few provisions and was left at sea on March 1, 1511. Together with the governor, 17 people embarked. The ship disappeared without a trace of Nicuesa or his companions.

In this way, Núñez de Balboa became the de facto governor of Veraguas. He immediately took steps to obtain official recognition. To this end, he sent two messengers, Mayor Zamudio and Valdivia, to present themselves before the viceroy of the Indies, Diego Colon. From there, Zamudio went to Spain. The efforts were successful because on December 23, 1511, the Crown named Balboa "governor and captain" of "the province of the Darien".

Núñez de Balboa was from then on in absolute command of Santa María la Antigua and Nombre de Dios. One of his first actions was to judge the bachelor Fernandez de Enciso for the crime of usurpation of authority, who was sentenced to jail and his goods were confiscated, although later Balboa released him in exchange for his return to Hispaniola and then to Spain. On the same ship were two representatives of Núñez de Balboa, with the mission of giving his version of the events of the colony and to ask for more men and supplies to continue with the conquest of Veraguas, which nominally reached Cape Gracias a Dios.

Meanwhile, Núñez de Balboa began to show his conquistador side by embarking to the west and traveling the Isthmus of Panama, subduing several indigenous tribes and forging alliances with others, such as the Coíba, Careta and Poncha chiefs. He crossed rivers, mountains and unhealthy swamps in search of gold and slaves. In a letter sent to the king of Spain, he said: "I have gone ahead by guide and even opening the roads by my hand". He was also able to quell revolts of several Spaniards who challenged his authority.

He succeeded in planting corn and received provisions from Hispaniola and Spain. He made his soldiers accustomed to the life of explorers of colonial lands. Núñez de Balboa managed to collect a lot of gold, partly from the adornments of the indigenous women and the rest obtained by violent means. In 1513, he wrote an extensive letter to the King of Spain in which he requested more men acclimated in Hispaniola, weapons, provisions, carpenters to build ships and the necessary materials to build a shipyard. In 1515, in another letter he spoke of his humanitarian policy towards the Indians and advised at the same time that the cannibalistic or feared tribes be punished with extreme severity.

At the end of 1512 and the beginning of 1513, he arrived in a region dominated by the cacique Careta. He was easily defeated and then became friends with Balboa, receiving Christian baptism and making an alliance with the Castilians that assured the subsistence of the colony, since the cacique promised to supply them with food. In exchange, the Spaniards would give him iron products, a metal unknown in the American continent that quickly became an object of prestige for the Indians.

To seal the alliance, Balboa took "as if she were a legitimate woman" the daughter or niece of Cacique Careta. Núñez de Balboa continued his conquest, reaching the lands of Careta's neighbor and rival, Cacique Ponca, who fled from his region to the mountains, leaving only the Spaniards and Careta's indigenous allies who plundered and destroyed the houses of the region. Soon after, he went to the domains of the cacique Comagre, fertile but very wild territory, although when they arrived they were received peacefully to such an extent that they were invited to a feast; in the same way Comagre was baptized.

It was in this region that Núñez de Balboa first heard of the existence of another sea on the other side of the mountains. During a dispute between Spaniards over the little gold they were finding, Panquiaco, eldest son of Comagre, was angered by the greed of the Spaniards and knocked over the scales that measured the gold and replied: "If you are so anxious for gold that you abandon your land to come and disturb another's, I will show you a province where you can satisfy that desire with your bare hands".

Panchikachus told of a kingdom to the south where the people were so rich that they used gold crockery and utensils for eating and drinking. He also warned that they would need at least a thousand men to defeat the tribes that inhabited inland and those on the coasts of the other sea. It was the first news of the Inca Empire.

The unexpected news of a new sea rich in gold was taken to heart by Nunez de Balboa. He decided to return to Santa Maria in early 1513 to have more men from Hispaniola, and it was there that he learned that Fernandez de Enciso had persuaded the colonial authorities of his version of what had happened in Santa Maria. Nunez de Balboa then sent Enrique de Colmenares directly to Spain to seek help, since there had been no response from the authorities in Hispaniola.

While in Santa Maria expeditions were organized in search of the new sea. Some traveled the Atrato River up to ten leagues inland, without any success. The request for more men and supplies in Spain was denied because the case of Fernandez de Enciso was already known to the Spanish Court. Thus, Núñez de Balboa had no choice but to use the few resources he had in the city to undertake the discovery. He had the wisdom to rely heavily on the Indians, who knew all the secrets of the jungle: routes to follow, where to get water, how to light a fire.

Using various reports given by friendly Indian chiefs, Núñez de Balboa set out from Santa Maria across the Isthmus of Panama on September 1, 1513, along with 190 Spaniards, some Indian guides and a pack of dogs. Using a small brigantine and ten indigenous canoes, they sailed to the lands of Cacique Careta. And on the 6th, from what was later called Acla, together with a large contingent of a thousand Careta Indians, among them Ponquiaco, to the lands of Ponca, who had reorganized himself; but he was defeated, subdued and made an alliance with Nuñez de Balboa. After several days and joining several of Ponca's men, they went up into the thick jungle on the 20th. They advanced with some difficulty, encountering black-skinned tribesmen.

They arrived on the 24th to the lands of the cacique Torecha, who dominated the town of Cuarecuá. In this town a fierce and persistent battle was unleashed; Torecha was defeated and killed in combat. When bursting into Torecha's house, the conquerors discovered his brother "in a woman's dress" surrounded by other notables. The Spaniards interpreted the scene as a homosexual harem and executed them all by throwing them to the dogs. After the battle, Torecha's men decided to ally with Núñez de Balboa, although a large part of the expedition was exhausted and badly wounded by the combat and many of them decided to rest in Cuarecuá.

Núñez de Balboa decided to continue the journey with a detachment of 67 Spaniards, an undetermined number of Indians, including Ponquiaco, and Francisco Pizarro. They entered the mountain ranges in the region of the Chucunaque River. Currently called Urrucallala mountains, between the Sabanas and Cucunatí rivers. According to reports from the Indians, from the top of this mountain range the sea could be seen, so Núñez de Balboa went ahead of the rest of the expedition and before noon managed to reach the top and contemplate, far on the horizon, the waters of the unknown sea.

It was on one of the peaks of the Urrucallala Mountains. The others hurried to show their joy and happiness for the discovery made by Nuñez de Balboa. The chaplain of the expedition, the clergyman Andrés de Vera intoned the Te Deum Laudamus, while the rest of the men erected stone pyramids and tried with their swords to engrave crosses and initials on the bark of the local trees, attesting that the discovery had been made in that place. All this happened on September 25, 1513.

After the moment of discovery, the expedition descended from the mountain ranges towards the sea and entered the lands of the Chiapes chieftain, who was defeated in a brief battle and invited to collaborate with the expedition. Three groups set out from the Chiapes region in search of roads leading to the sea. The group led by Alonso Martín de Don Benito arrived at its shores two days later, embarking in a canoe and testifying that they had sailed the sea for the first time. On their return they notified Núñez de Balboa and he marched with 26 men who arrived at the beach (Núñez de Balboa raised his hands, in one his sword and in the other a banner with an image of the Virgin Mary; he entered the sea up to his knees and took possession of it in the name of the sovereigns of Castile, Juana and Fernando.

Balboa baptized the gulf where they were as San Miguel, because it was discovered on the day of St. Michael the Archangel, September 29, and the new sea as the South Sea, name given then to the Pacific Ocean, by the route that the exploration took to reach that sea. This fact was an important milestone in the long search carried out by the Spanish for a maritime route to Asia by the west. A month later, on October 29, he made the second seizure outside the Gulf of San Miguel and on the coast of the open sea, somewhere on the present Gonzalo Vazquez beach.

Subsequently, Balboa dedicated himself to the search for the regions rich in gold. He traveled through the lands of the Coquera and Tumaco caciques, whom he easily defeated and snatched their riches in gold and pearls. He later learned that pearls were produced in abundance on some islands ruled by Terarequí, a powerful chieftain who dominated that region. So Núñez de Balboa decided to embark by canoe to those islands, despite the fact that it was October 1513 and the weather conditions were not the best. He barely managed to spot the islands, and named the largest of them Isla Rica (today Isla del Rey), and called the entire region the Archipiélago de las Perlas, a name it still retains today.

In November, Nuñez de Balboa decided to return to Santa Maria la Antigua del Darien but by a different route, to continue conquering territories and obtain greater wealth with his booty. He crossed the regions of Teoca, Pacra, Bugue Bugue, Bononaima and Chiorizo, defeating some with force and others with diplomacy. When he arrived at the territories of the cacique Tubanamá, Núñez de Balboa had to face him with great violence and managed to defeat him; in December he arrived at the lands of the cacique Pocorosa in the gulf of San Blas, already in the Caribbean and then he went to the lands of Comagre, where the cacique had already died of old age and his son Panquiaco had been named the new cacique.

From there he decided to cross the lands of Ponca and Careta, to finally arrive at Santa Maria on January 19, 1514, with a great booty of cotton articles, more than 100,000 castellanos of gold, without counting the amount of pearls; besides obviously the discovery of a new sea for the Spaniards. Núñez de Balboa assigned Pedro de Arbolancha to travel to Spain with the news of the discovery and sent the fifth part of the riches obtained to the king, as established by law.

Balboa would make a second crossing in 1517 departing from Acla but by a different route. The so-called Balboa Route would quickly be abandoned when the road from Nombre de Dios to Panama City was opened a few years later.

The accusations of Bachelor Fernandez de Enciso, whom Nunez de Balboa had stripped of power, and the dismissal and subsequent disappearance of Nicuesa caused that, at the request of Bishop Juan Rodriguez de Fonseca, the king appointed Pedro Arias de Avila, better known as Pedrarias Davila, as governor of the new province of Castilla de Oro, who would therefore replace Balboa in the governorship of the Darien. When Balboa's emissary, de Arbolancha, arrived at the Court, he calmed things down a bit.