Tourism Planning

- Post last modified: 2 October 2021

- Reading time: 19 mins read

- Post category: Uncategorized

Tourism planning like any planning is purpose-oriented, determined to accomplish some of the objectives by corresponding to the accessible resources and programs with the necessities and desires of the people.

Tourism as a whole is an activity that is judged as part of physical, environmental, social and economic planning. It is seen as a business activity, in which the public or private and individual stakeholders have different perspectives to plan it. But, the role of government agencies in developing countries is central to tourism planning.

Table of Content

- 1 Importance of Tourism Planning

- 2 Constraints in Tourism Planning

- 3.1 Transport

- 3.2 Accommodation

- 3.3 Tourist Activities

- 3.4 Product Development

- 3.5 Tourism Zoning

- 3.6 Marketing and Promotion

- 3.7 Institutional Framework

- 3.8 Statistics and Research

- 3.9 Legislation and Regulation

- 3.10 Quality Standards of Tourism Services

- 4 Types of Tourism Planning

- 5 Levels of Tourism Planning

Planning in tourism is setting and achieving the goals, keeping constraints in mind such as time, money etc. there are many approaches involved in tourism planning such as bottom-up approach, collaborative, boosterism, interactive, integrated etc. If you talk about planning in tourism in developing countries, it is generally taken by consultancy firms. But it has only been in the 1990s that tourism has been thought as a serious planning activity (Gunn, 1990; WTO 1994).

Tourism planning occurs at all levels international, national, regional and for specific areas and sites. National and regional planning establishes the policies, physical and institutional structures, standards for developments, while the local bodies generally implement them.

In 1992, Gunn spotted out that tourism industry was the result of the tourist’s desire to visit a particular location and culminated when his desires got fulfilled. According to him, planning helps tourism by critically reviewing the various choices available & to choose the most appropriate plan, so that the destination achieves the desired results in terms of economic and social aspects.

Hence, wherever planning is involved in tourism, the various things important are- reviewing the ground position w.r.t resources available (capital, material, human); setting objectives; appraisal of the various plans, selection of the most appropriate plan in tandem with the local community support & approach and achieving the desired results.

Importance of Tourism Planning

At all levels of tourism in order to achieve success, planning is vital for managing and developing tourism. This has been exemplified by many tourism destinations throughout the globe that planning that also long term can only lead to economic, socio-cultural and ecological benefits to both local community and tourists.

Following are the importance of tourism planning:

- Development of linkages and co-ordination of tourism with other sectors through policy formulation.

- Ascertaining the objectives and tourism policy in order to realize the goals.

- Preserving & conserving the resources (natural/cultural/man-made) efficiently and effectively, so that they are also kept for coming generations also.

- Planning can be used to upgrade and revitalize existing outmoded or badly developed tourism areas. Through the planning process, new tourism areas.

- Integrating tourism policy at national, regional and local level.

- Helps in making a tourism framework for effectual execution of hard work done both by public & private sector. The public sector creates an environment conducive for tourism development, while the private sector pours financial assets for developing tourism.

- Helps in the harmonized growth of the various elements of the tourist sector through co-ordination and involvement.

- It helps to maximize the benefits (economic, socio-cultural and ecological) to local community; poor people etc and help in impartial distribution of the benefits to everyone.

- t helps to minimize the negative impacts of tourism, if any.

- Right type of planning can ensure that the natural and cultural resources for tourism are indefinitely maintained and not destroyed or degraded in the process of development.

- Developing specialized training facilities.

- Achieving controlled tourism development requires special organizational structures, marketing strategies and promotion programmes, legislation and regulations, and fiscal measures.

- Planning provides a rational basis for development staging and project programming. These are important for both the public and private sectors in their investment planning.

- It promotes rational thinking and development for tourism growth and expansion.

- It helps in formulation of a skeleton framework which directs the tourism development in terms of facilities, infrastructure, services and attractions.

- Helps in formulation of tourism policy, plans and effective management of tourism areas, facilities etc.

- Helps in creation of guidelines and standards which help in preparing detailed plans for developing tourism destinations and circuits.

- Helps in incessant monitoring of the developmental activities of tourism.

- Positioning tourism as a major engine of economic growth.

- Developing suitable marketing plans with realistic, practical and sustainable targets.

- Employing sustainable environmental practices.

- Review of tourism polices and their evaluation.

- Development of planning criterion and analysis of resources.

- Providing adequate recreation opportunities and facilities in the tourist destination and tourist circuits.

- Proper land- use and planning of the physical spaces.

- Allocating an adequate level of funding for tourism programmes

In order to develop tourism, planning is done at all levels of tourism through policy formulation and planning activities. Though the nature and type of planning vary from one country to another ranging from developed to least developed countries.

But, tourism planning should have a firm foundation for which good research and study of the grass-roots level is very essential. Also, the plans need to be revised again & again based on the study results and likely future trends but retaining the basic structure.

Constraints in Tourism Planning

The constraints in tourism planning are:

- Lack of community participation : The unwillingness of the people to participate in the tourism activity limits its future. The tourism planning and in fact tourism can only give positive results, if it receives people support at every stage of tourism process.

- Limited budgets: Usually, government provides low or limited budgets to the tourism a Industry. And this makes tourism a very limited process.

- Accuracy and reliability of market data: for planning and management is also a serious problem in tourism. If the market information is incomplete or hazy, then also the goals of the tourism planning would be affected.

- Low priority accorded to the tourism sector: No, doubt, there has been a positive mindset w.r.t tourism in the Indian economy. But, still this sector deserves much more, then it has received.

- The poor quality of infrastructure & facilities present at the attractions: also act as a constraint in tourism planning and development.

- Quality of transportation service: The quality and quantity of transportation service is not very good. And needs great improvement.

- Multiplicity and high level of taxation: also gives less inspiration to the tourism entrepreneurs and creates more & more obstacles for the tourism.

- Facilitation of entry of tourists at ports(Airport/seaport/land port): The lengthy procedures involved in immigration should be made reasonable without giving the visitors much botheration and anxiety, before they visit the country for tourist purpose.

- Poor communication & awareness: A sound plan without clear communication can lead to duplication of endeavors and create differences among the stakeholders of tourism. It can also lead to occurrence of feuds among the stakeholders and create complexity.

- Conflict of interest: At times, the tourism policies can lead to conflict of interest among the stakeholders and create questions at the very start of the tourism planning. Hence, whenever policies are framed the local community should be involved at all levels, so that tourism policies not lead to planning failures.

Management constraints

- Legislative constraints and adherence to rules/regulations/ executive orders: Touism planning will have to abide rules & regulation related to environment, wildlife, local resources. And at times, it also creates impediments for the overall tourism project or plan for a particular tourism area/destination or tourism project.

- Environmental constraints: The presence of wetland, certain wildlife species, sensitive habitat, steep slopes, unstable soil, hazardous geologic conditions, tectonic movement, seismicity, critical habitat, lack of land base are the limiting factors or constraints in tourism development. And their incidence can create problems for infrastructure development and tourism planning.

- Carrying capacity constraints: Carrying capacity is the ability of a place to accommodate fixed number of individuals without affecting the ecology of the place. But, if this threshold increases, then it affects the ecology and resource base of that place. Carrying capacity can be divided into four types i.e. (1) social, (2) physical, (3) environmental (or ecological), and (4) facility. So, all these carrying capacity are adversely affected, if the number of individuals increases. This is one of the biggest constraints in the tourism planning as it is often violated in tourism.

- Apt understanding of ground realities: The improper understanding of ground realities can also lead to creation of tourism polices and tourism planning, which leads to no results. Hence, the policies become rudimental often at its inception stage.

- Inactivity dilemma: For the tourism planning process, the nodal agency involved may have large infrastructure, bureaucracy, man power involved but may suffer from the fear of change. This mental state creates a lot of obstacles in the tourism planning.

Scope in Tourism Planning

Tourism planning has come a long way in the tourism development process. But still, there is ample scope for betterment. The scope of Tourism planning are briefly explained below:

Accommodation

Tourist activities, product development, tourism zoning, marketing and promotion, institutional framework, statistics and research, legislation and regulation, quality standards of tourism services.

Accessibility plays an important role in tourism planning. It provides mobility to not only the tourists, but also the tourism policy or plan. If the means of transport such as land, air and water are developed, it also makes ground for implementing the tourism plan at the grass-root level.

Accommodation is one of the important A’s of the tourism industry. It also increases the carrying capacity of a place by accommodating more tourists. But, currently in India, if we want to increase the flow of tourists, then we also need more hotels or accommodation facilities to accommodate them. Hence, the tourism plans should give a priority to develop them.

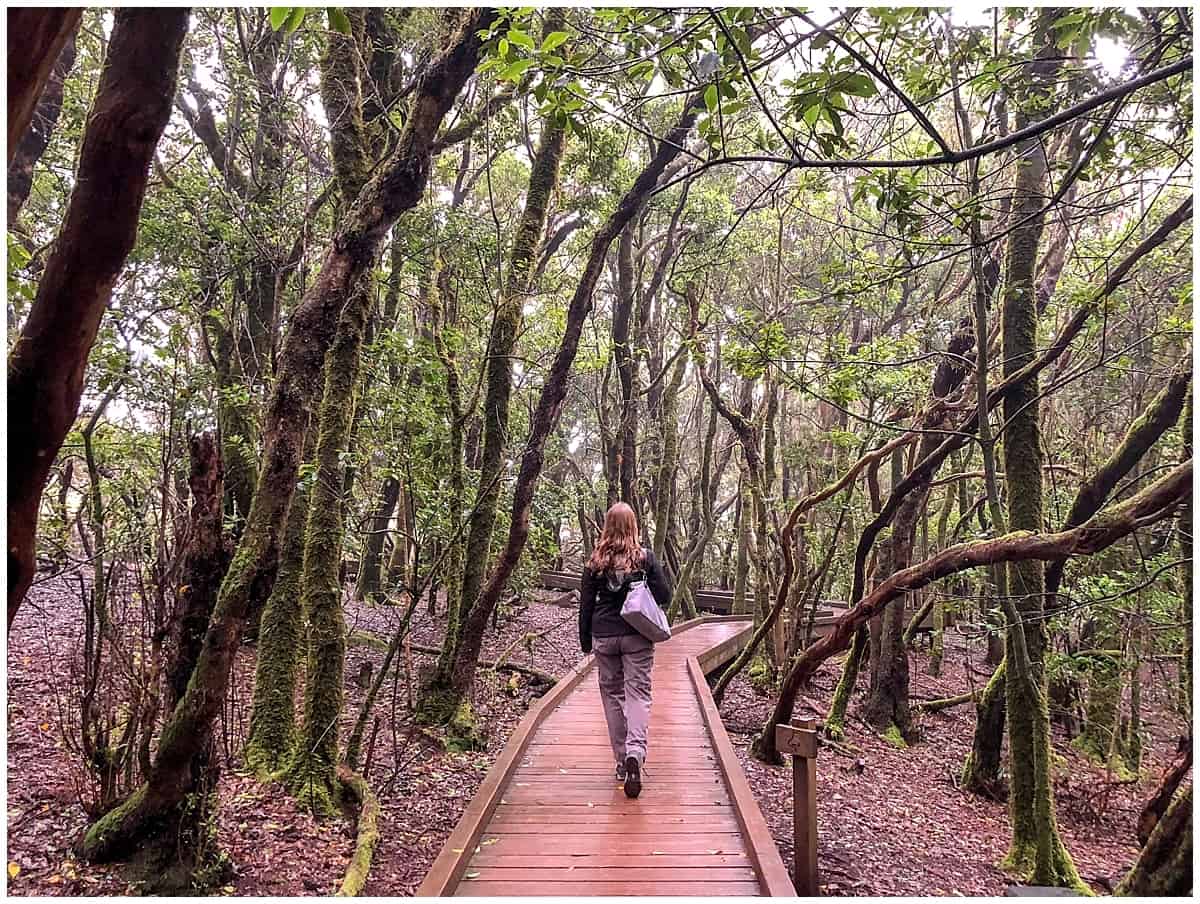

The tourist activities such as adventure activities, non-adventure activities, experiential activities in tourism such as in rural tourism, village tourism, Geotourism, ecotourism should be given more space in tourism development. And, these should be developed along with tourism concept as it gives more innovation to tourism, apart from enhancing the variety of experience to the tourists.

The diversity of the tourism product should be enhanced to give a variety of experiences to all tourists suiting their age, taste and culture. Also, emphasis should be laid down to develop the tourism product through quality gradation and innovation.

Also, importance should be given to developing a native product which is unique, indigenous to the land and helps in portraying the image of the land in terms of its culture, heritage, cuisine, festivals, folklores, traditions, dance forms, dresses etc.

Tourism zoning is an important aspect involved in tourism destination planning. It divides the tourist destination into various regions and segregates the tourist activity in those regions.

Marketing and Promotion are important elements in tourism planning and development. It needs more improvement in case of India. As, the tourism product of India is very diverse, indigenous and unique, still it lags in attracting the number of tourists. So, surely it is an area in tourism planning which needs great attention and careful planning.

Tourism development in India is institutionalized at a central level, state level and local level. But, still, there are large lacunas associated with it. The coordination of the institutions is delayed due to non-streamlined procedures, bureaucracy, nepotism, corruption etc and hampering the state of tourism in the country.

The tourism planning in India, still requires more research base and groundwork, prior to making the tourism policies. And, hence, if we want to improve our tourism planning and tourism policy, the research wings for the tourism industry have to be made sound and strong.

The existing legislation and regulations need to be revised to match up the current environment. Also, the legislation should be made keeping in mind the perspectives of all the stakeholders. They should not be made just by keeping the tourist in mind.

There has been great growth in the tourist infrastructure. But, in order to increase tourism competitiveness, importance have to be given on the quality of services and facilities. Also, the pricing of the tourism services is a big question. And, they should be made affordable keeping in consideration not only the foreign tourists, but also the domestic tourists whose role can also not be ignored.

Types of Tourism Planning

There are ‘n’ numbers of types of Tourism Planning. Some important ones are as follows:

- Spatial Tourism Planning: The space as well as the environment is scrutinized for creating good quality infrastructure e.g. Jim Corbett National Park.

- Sectorial Tourism Planning: Region to be developed is divided in to various broad sections called sectors e.g. South East Asia

- Integrated Tourism Planning: Parts of a tourist region are integrated so that the region becomes a hot destination.

- Complex Tourism Planning: When several regions are considered for planning which are far away e.g. Char Dham Yatra.

- Centralized Tourism Planning: Single authority, usually state or central Government, no private sector intervenes.

- Decentralized Tourism Planning: Parties who are keen to develop the spot, Government do not interfere. But it provides financial support.

- Urban – modern infrastructure

- Rural – culture, history, built from scratch

Levels of Tourism Planning

Tourism planning is implemented at different levels from the general level which may apply to an entire country or region down to the local level which may apply to detail planning for specific resort.

What is important to emphasize is the tourism planning and development must be integrated among all levels to take into account different levels of concern and to avoid duplication of efforts and policies.

Each level involves different considerations as follows:

- International level: Tourism planning at the international level involves more than one country and includes areas such as international transportation services, joint tourism marketing, regional tourism polices and standards, cooperation between sectors of member countries, and other cooperative concerns.

- National level: Tourism planning at the national level is concerned with national tourism policy, structure planning, transportation networks within the country, major tourism attractions, national level facility and service standards, investment policy, tourism education and training, and marketing of tourism.

- Regional level: Tourism planning at the regional level generally is done by provinces, states, or prefectures involving regional policy and infrastructure planning, regional access and transportation network, and other related functions at the regional level.

- Local or community level: Tourism planning at the local level involves sub regions, cities, towns, villages, resorts, rural areas and some tourist attractions. This level of planning may focus on tourism area plans, land use planning for resorts, and planning for other tourism facilities and attractions.

- Site planning level: Site planning refers to planning for specific location of buildings and structures, recreational facilities, conservation and landscape areas and other facilities carried out for specific development sites such as tourism Uttarakhand Open University 48 resorts and may also involve the design of buildings, structures, landscaping and engineering design based on the site plan.

Please Share This Share this content

- Opens in a new window X

- Opens in a new window Facebook

- Opens in a new window Pinterest

- Opens in a new window LinkedIn

- Opens in a new window Reddit

- Opens in a new window WhatsApp

You Might Also Like

Customer segmentation: strategy, shopping festival in india, indian hotel chain.

Preparing for Service in Restaurant

Golden chariot (mysore – goa), what is savoury types, dishes, service, this post has one comment.

Your notes are up-to-date, thanks so much

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Tourism Planning

Tourism Planning: The written account of projected future course of action or scheme aimed at achieving or targeting specific goals or objectives within a specific time period is called a Plan. A Tourism plan explains in detail what needs to be done, when to be done, how to be done, and by whom to be done. It often includes best case, expected case, and worst case scenarios or situations.

A plan is usually a map or list of steps with timing and available resources, used to achieve an objective to do something. It is commonly understood as a temporary set of projected actions through which one believes that the goals or targets would be achieved.

Plans can be formal or informal:

Structured and formal plans, utilised by numerous people, are more likely to occur in projects, diplomacy, careers, economic development, military campaigns, combat, sports, games, agriculture, technology, tourism, IT, Telecommunication etc. or in the conduct of other businesses.

In most cases, the absence of a well-laid plan can have high effects: for example, a nonrobust project plan can cost the organization long time and high cost.

The persons to fulfill their various quests do informal or adhoc planning. But, what most importantly matters is the extensiveness, time interval, and preciousness of the plans. Though, all these planning categories are not self-governing and dependent on each other.

For example, there is an intimate connection between short-range and long-range plans and tactical (strategic) & functional (operational) planning classifications.

For businesses, sector planning’s (such as IT, telecommunication, services, banking, tourism, agriculture etc.) and military purposes formal plans used to a greater level. They are conceptualized, thought as abstract ideas, are likely to be written down, drawn up or otherwise stored in a form that is accessible to multiple people across time and space. This allows more reliable collaboration in the execution of the plan.

Tourism Planning and the Need for Tourism Planning

Planning is one of the most important project management and time management techniques or methods. It involves preparing or forming of a sequence of action steps to achieve some specific desired goals. If you do it effectively and efficiently, you can reduce much of the necessary time and effort used in achieving the goal.

A plan is like a map or a blueprint which would fetch you results slowly & steady according to a time frame. Whenever, you are following any plan, you are able to know how much you have neared to your assignment objectives or how much distant you are from your goals.

Why is planning important?

- To set direction and priorities for the workforce in the organisation:

The strategy is the chief requirement of the organization, in order to achieve the targets. The strategies give the route and primacies (priorities) for your organization. It describes your organization’s perspective and gives an order to the activities that will make the perspective into reality.

Read more on World Federation of Tourist Guide Associations (WFTGA)

The plan will assist the team in achieving goals and also give them familiarity about the tasks. The plainly defined and appropriate strategy will give priority initiatives that will drive the maximum success.

- To get everyone on the same room or the same box:

An organisation has different departments, but a single goal. That’s, why different departments work in a way that add to the goals of the organization.

Hence, a strategy is required, so that all actions move in one direction. Then only, the various departments such as marketing, administration, sales, operations etc. can move together to accomplish the anticipated goals of the organisation. Tourism Planning

- To simplify decision-making process within the organisation:

Whenever, there are targets, there are different solutions. The team also may have new philosophies or probable solutions. Therefore, you need a definite plan, so there are no inhibiting factors.

- To drive alignment:

Many a times, inspite of the best labour, you reach nowhere. The reason is that the efforts or labour is done in areas, which are of no use. Hence, the effort should coincide with the priorities or primacies. The plan serves as a vehicle for answering the enquiry, that “How well we can use all the resources such as material, man, machine etc. to upsurge our tactical (strategic) success?

- To communicate the message to everyone:

The countless managers in the top level management know how to make an effective plan/strategy, at which position their organisation is, what they need to do and where they need to be there Many a time, the strategies are not written down and the various aspects in the plan are not linked systematically.

Then, only few members of your team can work towards your goals. Therefore, it’s very important that your team, staff, customers, suppliers and other stakeholder’s know your plan of action and strategy base, this will lead to better probability of success and more efforts pouring in. Tourism Planning

Also read Contribution of Tour Guiding in Sustainability

Once, you ascertain your goal, you are in a good position to make a solid proof plan in which role of each team member is defined. There are very less managers, who have understanding of situations and actually comprehend to make the greatest use of their part in smoothing policy (Eagles, McCool, Haynes, Philips, & United Nations Environment Programme, 2002).

Techniques of Plan formulation

It involves a number of steps:

- Collection of information (data):

The most noteworthy phase of economic planning is the gathering of the economic data. The data not only contains economic defining variables, but also descriptive variables such as demographical, topographical, and political data. The economic planning also contains non-quantitative variables. And surely in order to collect appropriate data the planner should have intra-disciplinary as well as inter-disciplinary knowledge.

- Deciding the nature and duration of the plan:

After the collection of data in context to the economy. Now the next step is deciding the nature and period (time duration) of the plan. Now, the planner has to decide the planning levels i.e. micro or macro basis, functional (practical) or structural (operational),centralised (central) or decentralised (distributed), long or medium or short term etc. The medium term plan generally comprises 5 years and is enough time periods to apply its drivers, strategies and approaches.

Also read Goals and objective of sustainable tourism development

- Setting up of the objectives:

The third step after setting the nature and time period of the plan is setting the goals or objectives or aim of the plan. And, surely these objectives will have to be realized in a fixed time schedule. Generally, most of the objectives related to economy of the country are related to advanced progress rate of GNP, reduction in joblessness, eradication of local discrepancies, removal of illiteracy, growth of farming and manufacturing areas, etc.

After, the planner has analysed the ground situation and given the objectives. Now, the planner has to establish these objectives depending on the eminence/Significance to the individuals and the economy in totality.

- Determination of growth rate:

While framing the plan, the planner has to determine the growth rate i.e. at what rate the economy will grow through this time interval. Whatever plan, the planner and policy makers decide at least, it should maintain the per capita income level of the country. The plan should be such that the per capita income do not decreases or affect the progress of the country negatively.

And, such a thing is possible, if the growth rate of GNP or growth rate of the country and growth rate or progress of the population is same. But this growth rate is least recommended. Rather, the planner will choose for that growth rate which is better than the population rate. “For example, if India wants to maintain its present per capita income while population is growing at the rate of 8% p.a., then the obligatory GNP growth rate should not be less than 8%. If we want to grow GNP by 8%, NI should grow @ 16%.

If the capital output ratio (COR) is 1:3, then we will have to invest 16% of GNP. While defining the growth rate, the planner must keep in view the growth rate of other adjoining or developing countries like Pakistan, China, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Bangladesh, etc.” Tourism Planning

- Full utilisation of financial resources of the plan:

The utilization of resources including the fiscal resources should be in a way that the predetermined objectives are realized. The various resources used in a plan of a country are human resources, natural resources, technology, worthy governance, entrepreneurial skills, financial resources etc. Therefore, from these resources or sources advantages or profits can be achieved.

Read more Local Community Involvement in Tourism Development

Broadly it can be categorized into renewable or renewal resources. Advantages of resource application may be augmented prosperity or needs, appropriate operation of a system, or boosted welfare. With the resource allocation, resource management is also crucial in a plan. The various resources have three basic attributes- “utility, limited availability, and potential for depletion or consumption.”

In order to accomplish the planning requirements, outside (external) resources are also used, when internal (inside) resources fall short. The outside resources generally comprises of foreign relief and support, foreign grants, foreign direct investment, and foreign borrowings from various International Financial Institutions (IFI’s) and rich countries.

The role of government is important and cannot be ignored. They plan and take various roles depending upon the environment of the country. When, a country is developed, their role more becomes as a facilitator, while in case of developing or poor countries, they have to actively participate in it. They have to implement plans as well as pour on their resources.

Whenever, the plans have been made by the government, they are sent to the necessary departments with goals, necessary steps and outlays. Thereafter, the concerned ministries or departments see the feasibility of the sent projects and give recommendations about the feasibility (viability) of various schemes and projects of the plan. Here, the government organisations are asked of their keeping in mind the sectorial distribution and extent of the plan. There are also some projects where partnership occurs between governmental and private sectors. Here, the government may play role of a catalyst or facilitator and there may be some revenue sharing understandings.

- Formation of economic policies:

In planning, plans are fine. The role of planners is fine. But, most importantly the plans should be able to give the desired results. The results should have more positive effects than the negative effects. Here, economic programmes, policies or strategies play a substantial role. As, they act as a gasoline to the locomotive of economic development. Also, the plans implemented should be based on ground or current scenario, rather than being picked from other countries, environments or sectors.

- Plan execution:

The final phase of planning is plan operation. And, for actual implementation of plan, following conditions cannot be ignored:

- The regime should be steady, truthful, genuine and productive.

- The organisational (administrative) system should be well-organized,

- i.e. free of nepotism, dishonesty, enticement, red tapism.

- Upkeep of law and order inside the nation.

- There should be equivalent level of involvement of both private and public sectors in economic growth.

- Keep a check on convenience and electronic up keep of government records, monetary proclamations and cost statements. Tourism Planning

- The opposition should be Watchful and productive. (Wagner, Frick, & Schupp, 2007)

- Different countries use planning models/techniques dependent upon the nature of the economy.

- The availability of the data, the volume to use and manage such techniques and models.

Read more Tourism Policy formulation Bodies in India

You Might Also Like

Complexity in Travel Decision Making

Challenges facing by Global Aviation Industry

Wait you forgot to try your Luck

Enter your email and get details on how you can win Prizes/ Shopping Vouchers

- Business Courses How to start a travel agency 4Ps of Tourism Marketing Interpersonal Skills Training Mastering in AIRBNB Travel Consultant Course Travel Photography Travel Agent Essentials Tourism Marketing Course International Tourism Course View All

- Destinations Alpines of Graubunden Lakshadweep Oman Andaman Manali Hampi Hawaii Hungary Saudi Arabia Ooty View All

- Hotels Centara Ras Fushi Resort Maldives Centara Grand Maldives Courtyard By Marriott Bangkok JW Marriott Bangkok FIVE Zurich Hyatt Ziva Los Cabos Hyatt Ziva Puerto Vallarta Sinner Paris Kandima Maldives View All

- Experiences ARTECHOUSE Kennedy Space Center An out of this world adventure SUMMIT One Vanderbilt Phillip Island Nature Park Trans Studio Bali Theme Park Zoos Victoria Vana Nava The Wheel at ICON Park View All

- Register with us

- Webinar Registration

- Destinations

- Experiences

- Business Courses

- TBO Portal Training

- Strategic Alliance

Existing Agents Login Here

Reset Password

Effective tourism destination planning.

The concept of tourism was introduced when early civilizations across the world started to travel for commerce and religious purposes, while some say tourism found its roots in the 17th century.

The Travel and Tourism Industry saw monumental growth during the second half of the 20th century when backpacking around Europe became a thing.

And today tourism industry is one the largest and fastest growing industry and sector responsible for economic growth. While it has great potential to boost the overall economy, strategic tourism planning is required to reap the benefits of the powerful and ever-expanding industry.

Destination and stakeholders must carry out purposeful, comprehensive, and, most importantly, inclusive strategic tourism planning. While we know that tourism destination planning is done to increase the tourism activities in the nation, but it is the responsibility of the authorities to make sure it is culturally appropriate for the citizens residing in it to support long-term success and sustainable growth.

While the trajectory of the tourism industry is unclear due to the covid-19 wave, now is the time to plan and adapt tourism destination planning and development strategies.

What is destination planning?

How to start planning for destination development.

We need to understand the importance of developing tourism in a way that it provides/adds great benefits to stakeholders while conserving the natural assets for generations. To up the tourism game of a destination will never be a straight path, it will require critical research and strategic tourism planning and defining the best-suited tourism marketing plan for the destination.

The world we all live in is home to infinite unique destinations waiting to be charted and show the world their unique features and assets, and diversity is the strength that we must undeniably safeguard. Saying that safeguarding the undeniable strength is no secret recipe, just a few points to keep in mind while deciding the steps of destination planning.

Steps of Destination Planning

Step 1 – Comprehensive Destination Assessment: A comprehensive destination assessment is the first vital step any destination or its stakeholder must take to understand the destination and its touristic approach.

Step 2 – Long-term approach: Comprehensive assessment must follow the long-term direction and should leave enough room for unforeseen circumstances, changing trends, and competition.

Step 3 – Record Consumer Behavior: Amid rising ecological consciousness or the ever-increasing presence of technologies, it is a must to record the behavior of the traveler.

When is the right time?

In the hope of economic prosperity and tourist dollars, the rapid expansion of the sector has set destinations to compete on a global scale. Before we hop on this train of the tourism destination planning process.

World travel and tourism council (WTTC), in a comprehensive study, outlines 75+ factors responsible for tourism growth. From tourist attractions and infrastructure to accommodations, connectivity, as well as overall economic development and tourism policies. The factors listed are essential factors

responsible to determine how prepared a destination is and the resulting challenges. It is necessary to keep in mind that the success potential of a destination does not depend on the number of arrivals but on effective resource management.

Meanwhile, as it is important to know when to start, it is equally important to know when to hit the brakes. Uncontrolled tourism development can result in environmental degradation, waste mismanagement, rising prices, overcrowding, social unrest among residents and overall exceeding of destinations’ capacity. Suggested Read: Event Tourism – Impact and Types

Who should lead the effort?

Government plays an important role in the implementation of appropriate investment decisions, regulations, and policies and in mitigating the negative impact of tourism development.

Good governance should lead tourism destination planning to establish appropriate administrative structures and frameworks for private and public sector cooperation, regulate the protection of heritage, assist in education and training, and will identify clear developmental objectives.

A DMO is a destination's strategic leader; it directs and coordinates the efforts of various organizations and people to achieve a common objective. The DMO serves as a mediator and advisor, pooling resources, and knowledge to provide key stakeholders with the resources they need to thrive by fostering strategic alliances between the local government, citizens, small enterprises, and NGOs. By bridging the gap between locals and tourists, a DMO will enable cooperative efforts to maximize the economic benefits of tourism. Suggested Read: Tourism Planning: Importance, Benefits, Types & Levels

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. what is destination planning in tourism, q2. what are the five a’s of tourist destinations.

A2. The five A’s of tourist destinations are:

- Accommodation

- Accessibility

- Attractions

Q3. What are the three features that make tourist destinations a hit?

A3. The three features that make tourist destinations a hit:

Q4. What are the main purposes of tourism destination planning?

A4. Destination planning ensures cultural and environmental protection while providing economic growth for local communities.

Q5. Who is responsible for tourism destination planning?

A5. Generally, this task is given to the government of the area. The government appoints a Destination Management Organization (DMO) that leads and coordinates the activities of tour operators, travel suppliers and other stakeholders towards a common goal.

- Things to do in Phillip Island: For an Incredible trip to Melbourne, Victoria

- Top 15 Things to Do in Victoria: Exploring Melbourne and Beyond

- Top 6 Places to Visit in Muscat: Top Attractions & Hidden Gems

- 10 Things to Do in Saudi Arabia Beyond a Spiritual Experience

- 8 Adventures in Oman: You shouldn’t be missing

- 8 Tourist Places to Visit in Lakshadweep: India’s Island Paradise

- 8 Best Things to do in Oman for a Holiday to Remember

- Full Proof Guide to 13 Top New Attractions in Dubai

- Top Things to Do at Katara Cultural Village, Doha, Qatar

- Exploring the Breathtaking Beaches of Tanzania: A Coastal Paradise

- Discovering Willy’s Rock: Boracay's Hidden Gem

- 10 Top Places to Visit in Oman, Tourist Places & Tourist Attractions

- Camping in Riyadh: A Recreational Escapade in the Desert

- Exploring the Serene Beauty of Big Buddha Temple Pattaya

- Top 8 Cafes and Restaurants in Yas Island: Casual Dining Options

21 reasons why tourism is important – the importance of tourism

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Tourism is important, more important than most people realise in fact!

The importance of tourism is demonstrated throughout the world. From the economic advantages that tourism brings to host communities to the enjoyment that tourism brings to the tourists themselves, there is no disputing the value of this industry.

The importance of tourism can be viewed from two perspectives: the tourism industry and the tourist. In this article I will explain how both the industry and the tourist benefit from the tourism industry and why it is so important on a global scale.

What is the importance of tourism?

Enhanced quality of life, ability to broaden way of thinking, educational value, ability to ‘escape’, rest and relaxation, enhanced wellbeing, who are tourism industry stakeholders, foreign exchange earnings, contribution to government revenues, employment generation, contribution to local economies, overall economy boost, preserving local culture, strengthening communities, provision of social services, commercialisation of culture and art, revitalisation of culture and art, preservation of heritage, empowering communities, protecting nature, the importance of tourism: political gains, why tourism is important: to conclude, the importance of tourism: further reading.

When many people think about the tourism industry they visualise only the front-line workers- the Holiday Representative, the Waiter, the Diving Instructor. But in reality, the tourism industry stretches much, much further than this.

As demonstrated in the infographic below, tourism is important in many different ways. The tourism industry is closely interconnected with a number of global industries and sectors ranging from trade to ecological conservation.

Why tourism is important to the tourist

When we discuss the importance of tourism it is often somewhat one-sided, taking into consideration predominantly those working in the industry and their connections.

However, the tourist is just as important, as without them there would be no tourism!

Below are just a few examples of the importance of tourism to the tourist:

Taking a holiday can greatly benefit a person’s quality of life. While different people have very different ideas of what makes a good holiday (there are more than 150 types of tourism after all!), a holiday does have the potential to enhance quality of life.

Travel is known to help broaden a person’s way of thinking. Travel introduces you to new experiences, new cultures and new ways of life.

Many people claim thatchy ‘find themselves’ while travelling.

One reason why tourism is important is education.The importance of tourism can be attributed to the educational value that it provides. Travellers and tourists can learn many things while undertaking a tourist experience, from tasting authentic local dishes to learning about the exotic animals that they may encounter.

Tourism provides the opportunity for escapism. Escapism can be good for the mind. It can help you to relax, which in turn often helps you to be more productive in the workplace and in every day life.

This is another way that the importance of tourism is demonstrated.

Rest and relaxation is very important. Taking time out for yourself helps you to be a happier, healthier person.

Having the opportunity for rest and relaxation in turn helps to enhance wellbeing.

Why tourism is important to stakeholders

There are many reasons why tourism is important to the people involved. There are many people who work either directly or indirectly with the tourism industry and who are therefore described as stakeholders. You can read more about tourism stakeholders and why they are important in this post- Stakeholders in tourism: Who are they and why do they matter?

The benefits of tourism are largely related to said stakeholders in some way or another. Below are some examples of how stakeholders benefit from tourism, organised by economic, social, environmental and political gains; demonstrating the importance of tourism.

The importance of tourism: Economic gains

Perhaps the most cited reason in reference to the importance of tourism is its economic value. Tourism can help economies to bring in money in a number of different ways. Below I have provided some examples of the positive economic impacts of tourism .

The importance of tourism is demonstrated through foreign exchange earnings.

Tourism expenditures generate income to the host economy. The money that the country makes from tourism can then be reinvested in the economy. How a destination manages their finances differs around the world; some destinations may spend this money on growing their tourism industry further, some may spend this money on public services such as education or healthcare and some destinations suffer extreme corruption so nobody really knows where the money ends up!

Some currencies are worth more than others and so some countries will target tourists from particular areas. Currencies that are strong are generally the most desirable currencies. This typically includes the British Pound, American, Australian and Singapore Dollar and the Euro .

Tourism is one of the top five export categories for as many as 83% of countries and is a main source of foreign exchange earnings for at least 38% of countries.

The importance of tourism is also demonstrated through the money that is raised and contributed to government revenues. Tourism can help to raise money that it then invested elsewhere by the Government. There are two main ways that this money is accumulated.

Direct contributions are generated by taxes on incomes from tourism employment and tourism businesses and things such as departure taxes.

According to the World Tourism Organisation , the direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP in 2018 was $2,750.7billion (3.2% of GDP). This is forecast to rise by 3.6% to $2,849.2billion in 2019.

Indirect contributions come from goods and services supplied to tourists which are not directly related to the tourism industry.

There is also the income that is generated through induced contributions . This accounts for money spent by the people who are employed in the tourism industry. This might include costs for housing, food, clothing and leisure Activities amongst others. This will all contribute to an increase in economic activity in the area where tourism is being developed.

The importance of tourism can be demonstrated through employment generation.

The rapid expansion of international tourism has led to significant employment creation. From hotel managers to theme park operatives to cleaners, tourism creates many employment opportunities. Tourism supports some 7% of the world’s workers.

There are two types of employment in the tourism industry: direct and indirect.

Direct employment includes jobs that are immediately associated with the tourism industry. This might include hotel staff, restaurant staff or taxi drivers, to name a few.

Indirect employment includes jobs which are not technically based in the tourism industry, but are related to the tourism industry.

It is because of these indirect relationships, that it is very difficult to accurately measure the precise economic value of tourism, and some suggest that the actual economic benefits of tourism may be as high as double that of the recorded figures!

The importance of tourism can be further seen through the contributions to local economies.

All of the money raised, whether through formal or informal means, has the potential to contribute to the local economy.

If sustainable tourism is demonstrated, money will be directed to areas that will benefit the local community most. There may be pro-poor tourism initiatives (tourism which is intended to help the poor) or volunteer tourism projects. The government may reinvest money towards public services and money earned by tourism employees will be spent in the local community. This is known as the multiplier effect.

Tourism boosts the economy exponentially. This is partly because of the aforementioned jobs that tourism creates, but also because of the temporary addition to the consumer population that occurs when someone travels to a new place. Just think: when you travel, you’re spending money. You’re paying to stay in a hotel or hostel in a certain area – then you’re eating in local restaurants, using local public transport, buying souvenirs and ice cream and new flip flops. As a tourist, you are contributing to the global economy every time you book and take a trip.

For some towns, cities and even whole countries, the importance of tourism is greater than for other. In some cases, it is the main source of income. For example, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council, tourism accounts for almost 40% of the Maldives’ total GDP. In comparison, it’s less than 4% in the UK and even lower in the US! In the Seychelles the number is just over 26% while in the British Virgin Islands it is over 35% – so tourism is vastly important in these nations.

The importance of tourism: Social gains

The importance of tourism is not only recognised through economic factors, but there are also many positive social impacts of tourism that play an important part. Below I will outline some of the social gains from tourism.

It is the local culture that the tourists are often coming to visit and this is another way to demonstrate the importance of tourism.

Tourists visit Beijing to learn more about the Chinese Dynasties. Tourists visit Thailand to taste authentic Thai food. Tourists travel to Brazil to go to the Rio Carnival, to mention a few…

Many destinations will make a conserved effort to preserve and protect the local culture. This often contributes to the conservation and sustainable management of natural resources, the protection of local heritage, and a renaissance of indigenous cultures, cultural arts and crafts.

The importance of tourism can also be demonstrated through the strengthening of communities.

Events and festivals of which local residents have been the primary participants and spectators are often rejuvenated and developed in response to tourist interest.

The jobs created by tourism can also be a great boost for the local community. Aside from the economic impacts created by enhanced employment prospects, people with jobs are happier and more social than those without a disposable income.

Local people can also increase their influence on tourism development, as well as improve their job and earnings prospects, through tourism-related professional training and development of business and organisational skills.

The importance of tourism is shown through the provision of social services in the host community.

The tourism industry requires many facilities/ infrastructure to meet the needs of the tourist. This often means that many developments in an area as a result of tourism will be available for use by the locals also.

Local people often gained new roads, new sewage systems, new playgrounds, bus services etc as a result of tourism. This can provide a great boost to their quality of life and is a great example of a positive social impact of tourism.

Tourism can see rise to many commercial business, which can be a positive social impact of tourism. This helps to enhance the community spirit as people tend to have more disposable income as a result.

These businesses may also promote the local cultures and arts. Museums, shows and galleries are fantastic way to showcase the local customs and traditions of a destination. This can help to promote/ preserve local traditions.

Some destinations will encourage local cultures and arts to be revitalised. This may be in the form of museum exhibitions, in the way that restaurants and shops are decorated and in the entertainment on offer, for example.

This may help promote traditions that may have become distant.

Another reason for the importance of tourism is the preservation of heritage. Many tourists will visit the destination especially to see its local heritage. It is for this reason that many destinations will make every effort to preserve its heritage.

This could include putting restrictions in place or limiting tourist numbers, if necessary. This is often an example of careful tourism planning and sustainable tourism management.

Tourism can, if managed well, empower communities. While it is important to consider the authenticity in tourism and take some things with a pinch of salt, know that tourism can empower communities.

Small villages in far off lands are able to profit from selling their handmade goods. This, in turn, puts food on the table. This leads to healthier families and more productivity and a happier population .

The importance of tourism: Environmental gains

Whilst most media coverage involving tourism and the environment tends to be negative, there are some positives that can come from it: demonstrating the importance of tourism once again.

Some people think that tourism is what kills nature. And while this could so easily be true, it is important to note that the tourism industry is and always has been a big voice when it comes to conservation and the protection of animals and nature. Tourism organisations and travel operators often run (and donate to) fundraisers.

As well as this, visitors to certain areas can take part in activities that aim to sustain the local scenery. It’s something a bit different, too! You and your family can go on a beach clean up walk in Spain or do something similar in the UAE . There are a lot of ways in which tourism actually helps the environment, rather than hindering it!

Lastly, there is something to be said for the political gains that can be achieved through tourism.

The tourism industry can yield promising opportunities for international collaborations, partnerships and agreements, for example within the EU. This can have positive political impacts on the host country as well as the countries who choose to work with them.

Tourism is a remarkably important industry. As you can see, the tourism industry does not stand alone- it is closely interrelated with many other parts of society. Not only do entire countries often rely on the importance of tourism, but so do individual members of host communities and tourists.

If you are studying travel and tourism and are interested in learning more about the importance of tourism, I recommend you take a look at the following texts:

- An Introduction to Tourism : a comprehensive and authoritative introduction to all facets of tourism including: the history of tourism; factors influencing the tourism industry; tourism in developing countries; sustainable tourism; forecasting future trends.

- The Business of Tourism Management : an introduction to key aspects of tourism, and to the practice of managing a tourism business.

- Tourism Management: An Introduction : gives its reader a strong understanding of the dimensions of tourism, the industries of which it is comprised, the issues that affect its success, and the management of its impact on destination economies, environments and communities.

Liked this article? Click to share!

Sustainable Tourism Planning and Why it Matters

Sustainable tourism is now an imperative focus for operators and communities. Major disruptions such as pandemics, climate change and new technology are influencing the way people feel about tourism, the way visitors are making decisions and the way industry responds to these changing expectations.

As connected global citizens, we are much more likely to seek out experiences which positively contribute to the people and places we choose to visit. How is your community taking notice of the shift toward sustainable tourism and making the most of what it has to offer?

What is Sustainable Tourism Planning?

Sustainable tourism planning is about finding the right balance between the needs of people and places. It involves clearly defining purpose, vision, and a point of difference or identity for your community. This form of destination planning in our communities enables us to think long-term, to be adaptable and proactive with changing target markets, trends and crisis like the Covid-19 pandemic. It also ensures we allocate resources appropriately while building local communities sustainably and ethically. Sustainability is at the heart of this approach to tourism planning, which benefits people and locations socially, economically, culturally and environmentally.

Planning with purpose is about prioritising the benefits tourism can provide for everyone and amplifying the quality of tourism over the quantity of tourism. It’s about maximising the quality of life for communities, protecting ecosystems, cultures, and the quality of experiences offered for visitors.

Our Top Sustainable Tourism Planning Tips:

- Use evidence to support decision making and let go of traditional approaches to your destination planning

- Articulate a strong united vision amongst your community, government and industry

- Identify the benefits you want to see in your area

- Focus on environmental and cultural advocacy and stewardship

- Connect with local Indigenous communities through purposeful engagement to capture their aspirations and further build the destination’s value proposition

- Build capability and strong, resilient local communities

- Seek out new products and experiences for ethical development opportunities

- Create new opportunities for investment and business development

- Collaborate with new partners and consider new organisational structures to get the best result

- Monitor and evaluate the environmental, social, cultural and economic benefits of tourism

- Consider risks and prepare for managing crisis and change.

Benefits of Sustainable Tourism Planning

Aside from attracting more interest in your community, your plan can extend across different sectors and attract the following benefits for your region:

- A good sustainable tourism strategy can preserve cultural and natural heritage for the benefit of locals and tourists alike

- The right planning can increase income thanks to tourist spending

- Planning for sustainable tourism allows you to implement strategies that increase people’s awareness and understanding of different cultures and ecosystems

- The money generated from the tourism industry can fund the construction of new infrastructures like educational and cultural centres that are of benefit to your community and to visitors.

The Bottom Line: The Importance of Sustainable Planning

Balancing the needs of the community with those of visitors is critical to protecting the very nature and culture of the places that make our world so special. This method of strategic, ethical tourism planning ensures you can maximise the benefits without causing disruption to local communities and leaving a negative mark on the region. READ MORE

Our Approach to Sustainable Tourism

Instead of thinking about how much value we can extract from experiences and places, at TRC Tourism , we focus on how many benefits we can create from tourism for the people and the places we love.

We provide support to communities with sustainable tourism planning services spanning sustainable destination planning , experience and product development , feasibility studies and business planning , indigenous tourism planning , and eco accreditation . From feasibility studies for wilderness trails to destination management plans and indigenous tourism programs, check out the hundreds of projects we’ve worked on for more than 20 years.

Ready to Explore Sustainable Tourism Planning for your Community?

Contact us today to see how we can take your destination and experience to the next level.

TRC is committed to the application of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the New Zealand Tourism Sustainability Commitment. TRC is a member of the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), and our team holds GSTC Professional Certificates in Sustainable Tourism. Our team of sustainable tourism practitioners provide practical advice on how to maximise the social, economic, environmental and cultural benefits of tourism.

Share this story on your favourite social media platform.

Related posts.

Exploring the Sinai Trail with Trailblazer Chris Halstead

Meet the Speakers attending the 2024 Sustainable Trails Conference

Commonwealth Innovation Awards 2023 winners

Cultural Tourism is About Building for Our Future

- Article Submission

- Basics of Geography

- Book Reviews

- Disaster Management

- Field Training and Tour

- Geography Notes

- Geography of Tourism

- Geography Study Material for NTA-NET & IAS Exams

- Geomorphology Class Black Board

- Hindi Posts

- Human Geography

- My Projects

- New UGC NET Syllabus-Geography

- Online Class

- Physical Geography

- Posts on Geography Practicals and Statistical Techniques

- North America

- South East Asia

- South West Asia

- Settlement Geography

- Social Geography

- Urban Systems

Useful Links

- Water Resources

- About Me and This Site

Tourism Planning: Overview and Importance

What is tourism planning.

…. And What is Planning per se.

Planning is to prepare a Road Map to achieve goals.

The principal phases of an urban planning process are:

- Preparatory / exploration phase

- Feasibility/planning phase

- Formal planning/zoning phase

- Design and implementation phase

- Operational phase

D.Getz (1987) defines tourism planning as” a process, based on research and evaluation, which seeks to optimize the potential contribution of tourism to human welfare and environmental quality”.

According to Faludi (1973) “Planning is a very important part of the process by which tourism is managed by governments at the national, local and organizational levels”.

If you search online for countries that have had success in planning their tourism, most of them are viewed as great travel destinations. Even to the point that people visit these countries with the guarantee that their travel vlogs will get youtube subscribers . In this day and age, that’s a marker of success.

Tourism development consists of many elements :

- developing and managing private-public partnerships,

- assessing the competitors to gain competitive advantage and

- Ensuring responsible and sustainable development.

Viewing tourism as an interconnected system and a demand-driven sector, assessing private sector investment and international cooperation, tourism clustering and involvement by the Government.

According to Williams cited in Mason (2003);

‘The aim of modern planning is to seek optimal solutions to perceived problems and that it is designed to increase and, hopefully maximise development benefits, which will produce predictable outcomes’.

We should take Planning tourism as an integrated System. Tourism industry is viewed as an inter-related system of demand and supply factors. The demand factors are international and domestic tourist markets and the local resident community who use the tourist facilities and services. The supply factors consist of the tourist attractions and activities as natural and manmade attractions like waterfalls, forests, beaches, monuments, zoos, etc.,

What Planning Should and Should Not Be

Basic Stages in Tourism Development Planning

Tourism development planning is a complex task.There are many variables to consider. There are different levels of tourism planning and policy.

On a basic level, the main stages in tourism development planning include:

- Analyses of earlier tourist developments

- Evaluation of the of status tourism in the area

- Evaluation of the competitors

- Formulation of Government Policies

- Defining a development strategy and the formation of a programme of action.

- The Implications of Planning

Planning enables a range of benefits to all stakeholders involved, for example:

- Increases income and jobs

- It helps preserve cultural and natural heritage

- It increases understanding of other cultures

- It builds new infrastructure facilities

(Read more here on Impacts of Tourism)

The impacts of tourism can be sorted into seven general categories:

- Environmental

- Social and cultural

- Crowding and congestion

- Community attitude

The costs of Tourism Development

There are also some costs which must be considered and planned for, which include:

- Costs of implementing tourist facilities can be costly

- The environment can be destructed to make room for hotels etc. to be built

- Social standards may be undermined e.g. topless women in Dubai

- The natural environment may be polluted

Formulating an approach to tourism policy and planning

There are six ‘golden rules’ that should be applied when formulating an approach to tourism planning and policy, as outlined by Inskeep (1991).

Goal Oriented

Clear recognition of tourism’s role in achieving broad national and community goals

Integrative

Incorporating tourism policy and planning into the mainstream of planning for the economy, land use and infrastructure, conservation and environment

Market Driven

Planning for tourism development that trades successfully in a competitive global marketplace

Resource Driven

Developing tourism which builds on the destination’s inherent strengths whilst protecting and enhancing the attributes and experiences of current tourism assets.

Consultative

Incorporating the wider community attitudes, needs and wants to determine what is acceptable to the population

Drawing on primary or secondary research to provide conceptual or predictive support for planners including the experiences of other tourism destinations

Why Tourism Planning is Important

Tourism planning really can make or break a destination. If done well, it can ensure the longevity of the tourism industry in the area, take good care of the environment, have positive economic outcomes, and a positive benefit to the community.

If executed badly, tourism development can destroy the very environment or culture that it relies on. It can disrupt local economies, cause inflation and negative effects to local people and businesses. Unfortunately, developing countries tend to suffer the most from negative impacts such as these, largely as a result of limited education and experience in contrast with Western nations.

Sources and Links:

Share this:

About Rashid Faridi

4 responses to tourism planning: overview and importance.

Hello Friend, I am Hira Nizami and I am regularly read your articles. Your articles are very charming and entertainment. Its motivate me to make a blog, and write an article. You know I am beginner please visit my site.

https://specialbeautiesoftheworld.blogspot.com/2020/09/9-astonishing-unseen-view-must-see-in.html?m=1

https://specialbeautiesoftheworld.blogspot.com/2020/09/12-secrets-that-help-you-to-win-murree.html?m=1

https://specialbeautiesoftheworld.blogspot.com/2020/09/siri-paye-such-supernatural-place-you.html?m=1

Thank you so much sir it helped a lotttt

This page a big help to us for a better planning for the future in the field of research.

Thank you for simplifying the work

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Total Visitors

Search inside, my you tube channel.

Jugraphia With Rashid Faridi

Visitors on The Site

Subscribe by Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this Blog.

Email Address:

Click Here to Subscribe

Fill This Form to Contact Me

Top posts & pages.

- Peopling Process of India: Technology and Occupational Change

- Social Geography: Concept,Origin,Nature and Scope

- Migration Theories : Lee’s Push Pull Theory

- Types of Tourism : An Overview

- Eight Major Industrial Regions of India

- भारत के पर्वत व पर्वत श्रेणियाँ

- Geography Study Material for NTA-NET & IAS Exams

- Planning Regions of India: Concept,Classification and Delineation

- The Structure of the Ocean Floor(Ocean Topography)

- Problems of Cities

Being Social

- View rashidazizfaridi’s profile on Facebook

- View rashidfaridi’s profile on Twitter

- View rashidfaridi’s profile on Instagram

- View rashidafaridi’s profile on Pinterest

- View rashidazizfaridi’s profile on LinkedIn

- A load of crap from an idle brain

- Akhil Tandulwadikar’s Blog

- Anast's World

- Earth in Danger

- Install Flipkart on your Mobile

- Onionesque Reality

- WordPress.com

- WordPress.org

Digital Blackboards

- Geomorphology Class Blackboard

- My Page at AMU

Other Sites I Am Involved With

- Bytes From All Over The Globe

- Jugraphia Slate

- Rakhshanda's Blog

Recommended Links

- Dr. Shonil Bhagwat's Blog

- Top Educational Sites

- Trainwreck of Thoughts

- Views of The World

- Access and Download NCERT Books Free

- My Uncle Fazlur Rehman Faridi on Wikipedia

Treasure Hunt

- Buy Certificate Physical and Human Geography

- Buy BHARAT KA BHUGOL 4th Edition from Flipkart.com

- Buy BHUGOLIK CHINTAN KA VIKAS

- INDIA A COMPREHENSIVE GEOGRAPHY by KHULLAR D.R.

Tourism Geography

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Why We’re Different

- Join Our Team

- Strategic Alliances

- Why Tourism

- Strategic Planning

- Tourism Development

- Workforce Development

- Destination Management

- Destination Marketing

- Solimar DMMS

- Creative Portfolio

- Testimonials

- Tourism for Development Blog

- Case Studies

- Useful links

7 New Trends in Tourism Planning You Must Know

Written by Greta Dallan on July 26, 2022 . Posted in Blog , Uncategorized .

What is Tourism Planning?

Tourism planning consists of creating strategies to develop tourism in a specific destination. Knowing and understanding current trends allows those in the industry to tailor their operations to meet demand. It is crucial for DMOs and tourism businesses to stay up-to-date.

Origin and development of tourism planning

Tourism planning was born from the necessity of simultaneously balancing the economic goals of tourism and preserving the destination’s environment and local welfare. It arose in the second half of the 1990s, when mass tourism brought an unparalleled change in the travel environment. Consequently, the industry had to develop new standards to adapt to this change.

The aim of tourism planning

The current objective of tourism planning is to control tourism’s unprecedented expansion to limit its negative social and environmental effects, while maximizing its benefits to locals.

These goals can be reached by:

- Analyzing the development of tourism in the destination

- Examining the state of affairs in a specific area and executing a competitive analysis

- Drafting tourism policies

- Defining a development strategy and actionable steps

Businesses looking for support through this process can reach out to Solimar International or check out this free toolkit . Solimar has a dedicated team of staff who employ a wide range of skills to promote economic growth, environmental preservation, and cultural heritage conservation.

Why is Tourism Planning Important?

Tourism planning should be part of destination development plans because it supports a destination’s long term success and incentivizes the collaboration of key stakeholders.

Tourism planning maximizes tourism benefits like:

- Promotion of local heritage and cross-cultural empathy

- Optimization of tourism revenue

- Natural environment and resource protection

Tourism planning also minimizes tourism drawbacks such as:

- Overtourism, and consequently anti-tourism feelings

- Economic leakage

- Disrespect for the local culture

- Damage to the local environment

Tourism planning is also important because, by creating plans and strategies, destinations provide an example that other destinations can follow to improve tourism in their area. It ensures that the destination is consistent with changing market trends, constantly addressing tourist and resident needs as they arise.

This was made clear in the Cayman Islands. The surge of cruise tourism caused a massive influx of tourists, which brought new challenges to the small islands. Consequently, the destination’s goal shifted from attracting tourists to sustainably managing them. The development of a National Tourism Management Plan was key to provide stakeholders with the tools they needed for sustainable tourism management.

What are the Newest Tourism Trends?

In the planning process, it is fundamental to consider how new tourism trends influence the future of tourism planning and allow destination strategies to stay innovative.

1. Safety and Cleanness

The Covid-19 pandemic brought about significant change to tourism and tourists’ perception of travel. Tourists are now more concerned about safety and cleanliness. They have a preference for private home rental, contactless payments, and booking flexibility due to the constantly-evolving global health situation. They are also more willing to visit natural environments and less crowded destinations where they feel safer.

→ Tips for DMOs : Have safety and cleanliness standards, allow flexible bookings and contactless payments, and focus on open-air experiences.

An excellent example of these practices is Thailand, which decided to boost tourism after Covid-19 by rebranding itself as a safe tourist destination , issuing safety certificates to infrastructures to build public trust.

2. Social Media

Social media is the preferred channel for travel inspiration, influencing travelers’ decision-making because videos and pictures create an emotional bond between people and places.

The preferred platform depends on the traveler’s generation :

- Gen X uses Pinterest and aesthetically pleasing blogs

- Millennials use Instagram

- Gen Z uses TikTok

Generation Z is also more willing to travel after Covid, and they will have high spending power in the next few years .

Video content is favorable because of the high engagement and interaction it creates compared to pictures. In this context, TikTok is the future of travel marketing. On this fast-growing platform, videos are likely to become viral because of the app’s algorithm. For example, the travel campaign #TikTokTravel, where people were invited to share videos of their past trips, was viewed by 1.7 billion people .

→ Tips for DMOs : DMOs can use TikTok to promote attractions, restaurants, and tours partnering with influencers. Social media can attract new customers, monitor Instagrammable locations, and manage overcrowding by promoting lesser-known areas. This all helps shift tourists away from hot spots.

Follow Solimar International’s success with social media promotion through their World Heritage Journeys of the European Union project. By providing research, media-rich itineraries, website promotion, and mobile maps, Solimar International can help your organization reach its target audience.

3. BLeisure Travel

Due to technology, the separation between work and life is blurred. This premise gives birth to the BLeisure travel, a genre of travel that combines business and leisure . Aside from those who travel for work, combining some leisure during their stay, there is an increasing number of digital nomads. These people are freelancers or smart workers who decide to adopt a traveling lifestyle. They will look for business hotels where they can easily obtain a fast Internet connection and a good working environment.

Some destinations are rebranding themselves, targeting those who work remotely. A good example is Aruba, which promotes itself as a paradise for workation .

4. Destination Uniqueness

The tourism market is becoming increasingly competitive, especially for destinations with similar climates or natural features. To stand out, destinations need to focus on their distinctive assets. Places should identify a destination brand, which highlights their culture and the unique experiences they offer to tourists, instead of branding common and widely-available tourism practices.

An example of destination uniqueness as a trend of tourism planning is Uganda, which is widely known as a safari destination. The country rebranded itself by focusing on its one-of-a-kind cultures, landscapes, food, and traditions, labeling itself “The Pearl of Africa.” This is one aspect of Uganda’s tourism planning process. By identifying and promoting a destination brand, Uganda aims to develop an immersive tourism for meaningful and transformative experiences abroad.

5. Transformative Travel

Transformative travel is an expression of the experience economy combined with experiential travel. The latter is about living once-in-a-lifetime, off-the-beaten-track experiences rather than conventional ones, connecting visitors with local cultures.

Transformative travel is defined by the Transformational Travel Council as:

“ intentionally traveling to stretch, learn and grow into new ways of being and engaging with the world.”

Therefore, transformative travel is an immersive experience that aims to inspire personal transformation, growth, and self-fulfillment. People travel to transform their own lives and the lives of those who live in the destination.

→ Tips for DMOs : Destinations should focus on providing unique and authentic experiences that connect travelers with locals. This enables tourists to experience local culture, food, and lifestyles, lending way to authentic experiences that they are sure to remember.

6. Sustainability and Community Engagement

Travelers are becoming more conscious of their environmental impact, and they are more willing to adopt a sustainable travel style. This means not only doing less harm to the environment, but also making a positive impact on cultures and economies, generating mutually beneficial relationships between tourists and locals.

An excellent example of a country that stays ahead of trends in tourism planning is Jamaica. Instead of boosting sun and beach tourism development, Jamaica has recently focused on community-based tourism , providing several experiences that empower locals.

By focusing on poverty reduction, gender empowerment, equality and employment, Jamaica utilizes tourism to achieve social justice goals.