5 Ways to Fix Knee Pain When Squatting

No matter what anyone tells you, squatting doesn't actually cause knee pain. Instead, most knee pain when squatting is actually due to muscle imbalances or limited mobility . That's because your joints are affected by the movement in your joints directly above and below them.

Advertisement

After all, your knee joint is located between your hip and ankle joints, so any issues in your feet, ankles, hips and glutes can end up affecting you knees.

Video of the Day

That said, learning how to fix knee pain from squatting doesn't have to be that tricky. Here are five form adjustments and mobility drills you can do the next time you get low.

Related Reading

Knee Pain During Squats? Here's What Your Body Is Trying to Tell You

1. Grip With Your Feet

Strong, active feet provide a solid base of support and help properly distribute forces throughout your joints. If you don't know how to actively engage with the ground using your feet, other joints — including your knees — take on excessive load when you squat.

Think of how you would grab a heavy dumbbell with your hands: You wrap your fingers around the handle and grip hard. Ideally, your feet should be doing something similar when you squat.

Focus on grabbing the ground with your toes and think about pushing the floor away from you with your feet. If you're struggling to activate your feet, try squatting in your socks so you can better feel your connection with the ground.

Imagine you are straddling a huge crack in the earth. Your job as you squat is to try to spread that crack apart with your feet.

Another thing to watch out for is your heel(s) popping off the floor. The ball of your foot, its outside edge and your heel should all stay in constant contact with the ground while squatting or lunging.

"Keeping the heel 'glued' to the ground can prevent knee pain from squatting," says Michelle Kania, CSCS , a certified strength and conditioning specialist and owner of One Day Better Training.

2. Work on Your Ankle Mobility

If your ankles don't move well, your knees pick up the slack. Poor ankle mobility is one of the most overlooked obstacles to squatting with great form

According to a March 2015 study in the Journal of Human Kinetics , ankle dorsiflexion (raising your toes toward your shins) plays a major role in the depth of your squat , aka how low you can go. This means if your ankles don't bend very well, you'll have a hard time getting into the bottom of a squat.

You can improve your ankle mobility by including some ankle drills in your warm-up . The half-kneeling kettlebell ankle drill below uses the weight of the kettlebell to gently drive your knee forward over your toe. Be sure to keep your heel down on the floor throughout the rep.

"Tight calves can also make it harder for your knee to move past your toes without your heel popping up off the ground," Kania says.

Spend a couple of minutes at the start of each workout foam rolling your calves to help relax these overly tight muscles.

Half-Kneeling Kettlebell Ankle Drill

- Start in a half-kneeling position and place one knee down on a pad so that it's directly beneath your hip. Your back toes should be flexed and pointing to the floor. Bend your front knee so it forms a 90-degree angle. This foot should remain flat on the floor throughout the exercise.

- Place a mid-weight kettlebell on top of your front side. The weight should be heavy enough to push you into the stretch, but not so heavy that it causes pain or excessive leg fatigue.

- Use the weight of the kettlebell to gently guide your knee out over your toe. Keep the knee in alignment with your toes and do not allow it to travel in toward the middle of your body.

- Go as far as you can while still keeping your front heel glued to the floor. When you reach end range ankle dorsiflexion, return to the starting position.

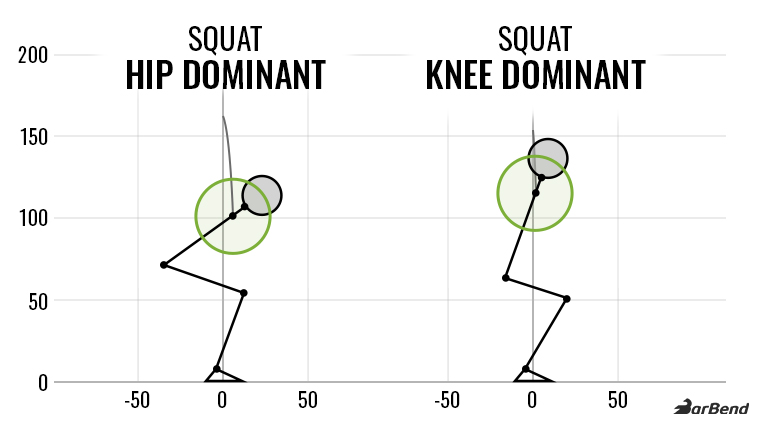

3. Lead With Your Hips and Knees

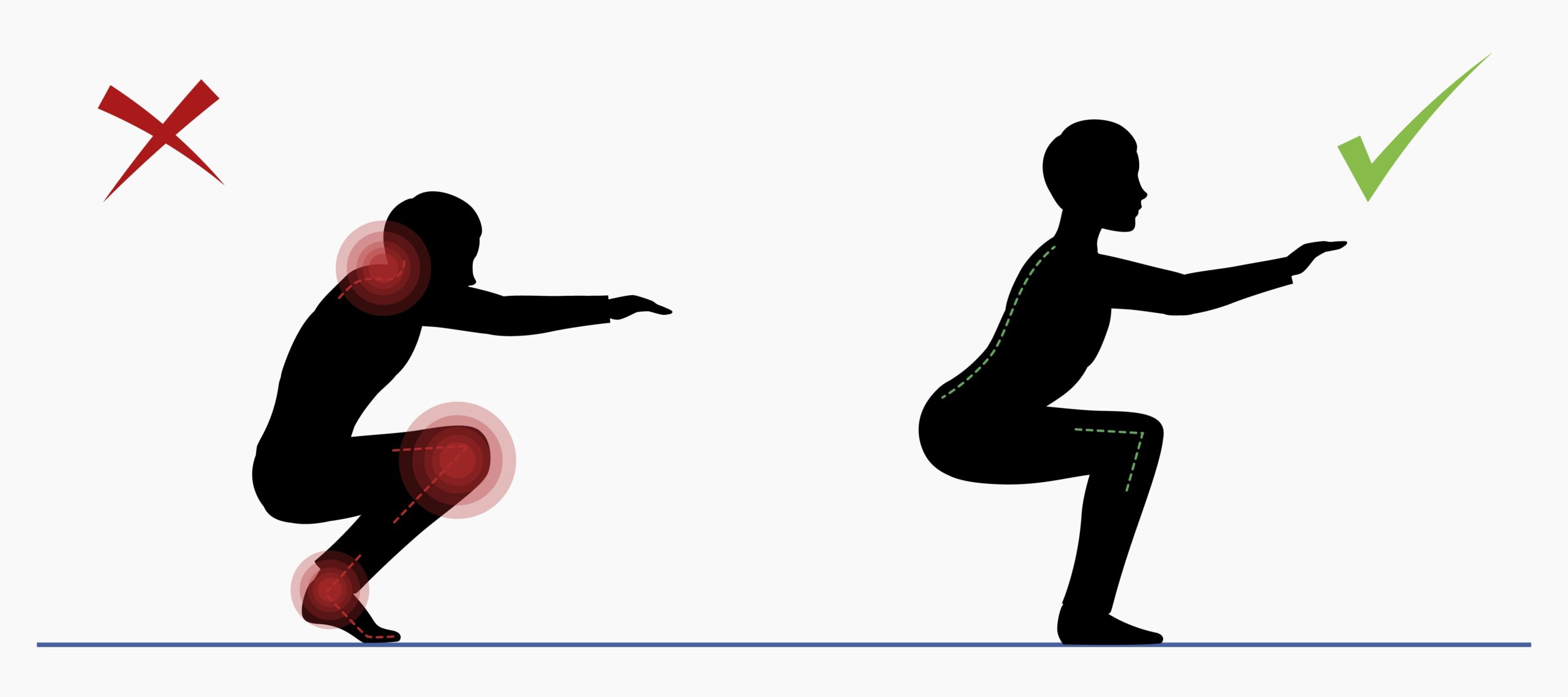

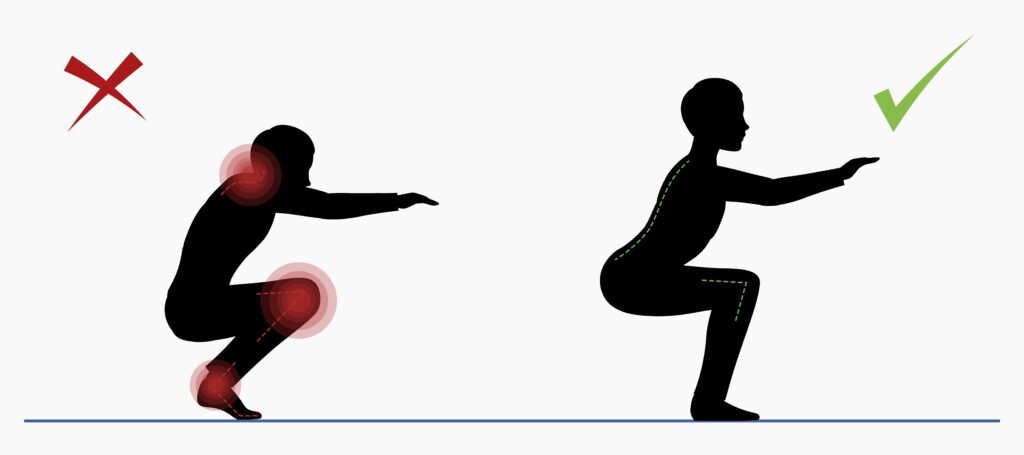

One of the biggest mistakes that contributes to knee pain when squatting is starting the exercise from your ankles. When you bend at your ankles first, your knees automatically shoot out over your toes without your hips sh0oting behind as a counterbalance. This causes your knees to absorb nearly the entire load as you squat.

To avoid this problem, begin each rep by moving your hips and knees. Think about squatting both back and down so your hips take on their fair share of the load. This way you'll also be able to use your glutes and core to support yourself throughout the movement.

It might also be helpful to do box squats (see below) to help you understand how far back your hips should go.

- If possible, select a box that allows you to squat down so your thighs are parallel with the floor. People who are tall, those with limited hip or ankle mobility or those with active knee pain may need to use a higher box.

- Start standing in a tall and tight upright position.

- Initiate the movement by reaching your hips back and bending your knees. Think about sitting both back and down. Grab the floor and try to spread it apart with your feet.

- Continue descending into your squat until your hips reach the box.

- Finish the movement by driving your feet into the floor to stand up. Keep your chest tall throughout the rep. Don't allow yourself to excessively fold over or lean forward.

Relates Reading

How Bad Is It Really if Your Knees Go Over Your Toes During Squats and Lunges?

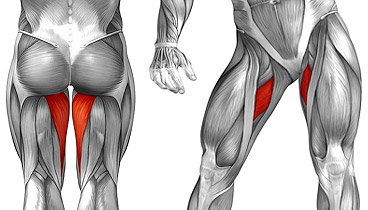

4. Strengthen Your Glutes

Sometimes, to fix knee pain from squatting, you kneed to focus on your hips and glutes. Your glutes, and primarily your side glutes, play a big role in stabilizing your knee joint. So any weaknesses there can make things go off-track.

But, of course, most lower-body workouts ignore the side glutes (gluteus medius and minimus). Fix that by doing side-to-side exercises like lateral band walks , clamshells and side squats .

The 32 Best Glute Exercises for Every Piece of Equipment

5. Choose a Different Squat Variation

If you struggle with knee pain during squats, try a different squat variation (think: goblet squats , double kettlebell squats , barbell front and back squats, air squats , sumo squats ).

While front-loaded squats put more stress on your quads and knees, they also use a pretty upright posture that some people prefer. Meanwhile, backloaded squats take some pressure off of the knees, but require you to hinge more at the hips and move your knees farther over your toes.

In the end, everyone is a bit different in what works for them. So test out the variations and stick with the ones that feel most comfortable on your knees. Over time, as you build strength and mobility in your legs, you may be able to expand your squat repertoire.

The 30 Best Squat Variations for Every Exerciser and Piece of Equipment

5 Exercises to Help You Improve Your Squat

The 5 Best Mobility Moves to Deepen Your Squat — Glute Gains Guaranteed

How Deep Do You Really Need to Squat?

- Journal of Human Kinetics: "Lower Extremity Strength and the Range of Motion in Relation to Squat Depth"

Was this article helpful?

150 Characters Max

Thank you for sharing!

Thank you for your feedback!

Report an Issue

Screenshot loading...

What to Do if Squats Hurt Your Knees

What to do if you love squats, but your knees are giving you too much pain to go on.

SQUATS SHOULD MAKE you feel something, since they're among the most important—and potentially the most heavily-loaded—compound lifts in your strength training arsenal. One thing you shouldn't feel from squats is knee pain.

Knee pain isn't a death sentence for your leg day gains, however, or even your ability to perform squats. You don't need to take a break from squatting to heal your aches. You just need to address the issue causing the knee pain in the first place. Here, Samuel looks at 4 common issues that typically lead to knee aching after squatting, and offers solutions to work through them.

Why You Have Knee Pain With Squats

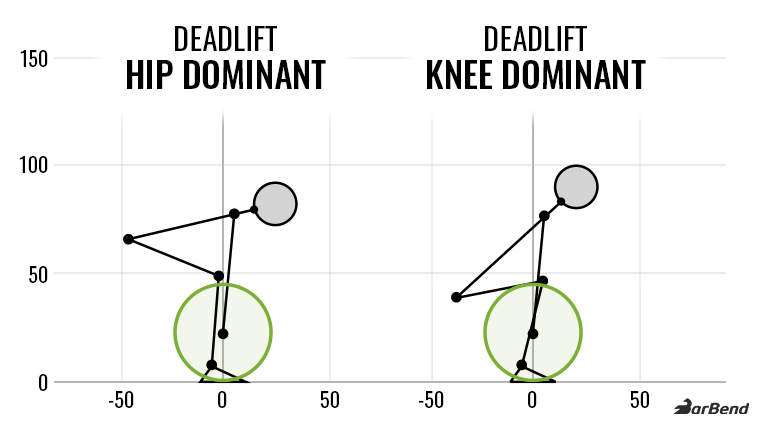

Problem 1: you load your hips wrong.

Yes, squats are a knee dominant exercise, but the hips are also heavily involved. To load some pressure into the glutes, you need to hinge backwards. If you don't, extra stress can translate to the knees, which may cause pain. Poor hip loading can happen for several reasons, and you simply need to restore the feeling of proper loading and timing, Samuel says.

Touch Down Squat

The touch down squat allows you to keep a perpendicular shin at the knee throughout the movement, which is going force you to load at the hips. This exercise is going to help you "rebalance your entire squat motion," Samuel says.

How to Do It:

- Grab one plate to start—if you get through a full set without knee pain, then you can go higher and grab another.

- Stand on your platform.

- Push your butt back to slowly lower your other leg to where your heel meets the floor. Go as slow as you can on the way down.

Set and Reps: Do 3 to 4 sets of 6 to 8 reps per side as a warmup to your standard squats

Problem 2: Your Glutes Are Weak

If you're lacking glute strength, your hips won't be able to externally rotate under great load they way they need to in a heavy squat. In a squat, your knees need to be able to track outward to properly align with your shins to create an efficient movement pattern. Opening up the knee requires strength through the glutes.

These may look silly, but the clamshell is one of the best exercises to work on hip external rotation.

- Lay down on your side, and place a resistance band just above your knee if you have one (you can still do the move against gravity if you don't have one).

- Slightly bend your knee forward. Keep your heels together as you drive your top knee up.

Set and Reps: Do 2 to 3 sets of 20 reps per side as a warm up to your squats.

Monster Walks

This exercise also helps build outer glute strength, which will ultimately help your knee maintain proper position when squatting.

- Place a resistance band just above your knees. You can also place one around your ankles for a little extra challenge.

- Bend your knees slightly to get into an athletic stance—think quarter squat—like a defender on a basketball court.

- Take 5 to 10 steps laterally each way. Think about stacking your knee over your ankle every step.

Set and Reps: Do 2 to 3 sets of 5 to 10 steps each direction as a warm up to your squats.

Problem 3: You Don't Bend Your Knees Enough

Everyday movement doesn't typically call for a ton of deep knee flexion, the bent position you'll find yourself in when you perform a full-depth squat. Even if you're only working on squatting to a 90 degree or parallel position, you still get a few benefits from working on deep knee bending. This action can help build tendon strength in the knee, and "spending time in deep knee flexion is going to train our quads in a lengthened position," Samuel says.

ATG Split Squat

The ass-to-grass split squat really emphasizes bringing your calf as close as you can to your hamstring, finding that intense strength into knee flexion.

- Grab one or two plates to create a platform. Place one foot on the platform and extend out the back foot, finding a good split squat stance .

- Shift your weight down and forward onto the front leg. Drive your knee as far over and in front of your toes as possible—don't be afraid to lift up off the heel a bit.

- Time your time, and feel that stretch. Hold for 2 to 3 seconds before pushing back up.

Set and Reps: Do 3 sets of 6 to 8 reps per side as an accessory motion on your leg days, or at least 2 to 3 times a week.

Assisted Squat with Heels Up

This move provides a similar idea to the split squat with a bilateral (two-foot) movement, while loading the knee just a little differently. You're still trying to get the hamstrings to touch the calves.

- Find something sturdy to hold on to like a post or side of a squat rack.

- Spread your feet out hip width apart, and load your weight into your toes. Lift the heels up off the ground.

- While holding your base, squat down to where you bring your calves as close to your hamstrings as possible, keeping your heels lifted the whole time.

- Hold that position for 2 to 3 seconds before pressing up.

Set and Reps: Do 2 to 3 sets of 5 reps, every day.

Problem 4: You Lack Ankle Mobility

A good squat depends more on ankle mobility than you would think. You have to shift the knees forward, and that can't be done that without proper flexibility through the ankles—specifically in the Achilles tendon.

Kneeling Ankle Stretch

This is a very simple stretch that you can incorporate into your squat warm up routine to prep the ankles for motion.

- Get down onto one knee. Place one thumb around your Achilles tendon on your front foot.

- Push down with that hand to ensure your heel doesn't pop up off the ground while you shift your weight forward into that foot.

- Track your knee as far forward over your toes as possible.

- To get a deeper strength, place a little bit of pressure over top of your front knee.

Set and Reps: Do 1 to 2 sets of 3 to 5 reps during your squat warm up, or in between your squat sets.

.css-1fpt53b{height:1.25rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-1fpt53b{overflow:unset;line-height:1.25rem;}}@media(min-width: 48rem){.css-1fpt53b{line-height:1.25rem;}}.css-1fpt53b:before{background-color:#D2232E;color:#fff;margin-right:0.625rem;width:1.25rem;height:1.25rem;content:'';display:block;} Workouts

The Best Chest Exercises to Build Stronger Pecs

This Is How to Bench Press Correctly

Jake Gyllenhaal's 'Road House' Workout

15 Moves to Smoke Your Back With Just Dumbbells

How to Get a (Stronger) Grip

Build Massive Calves With These Workouts

How to Do a Perfect Dumbbell Chest Fly

The Moves You Need for Hamstring Muscle

Build Lower Body Power With Box Squats

How Many Situps You Should Do in a Day

The Beginner's Guide to Weight Training

HOW TO ELIMINATE KNEE PAIN DURING SQUATS (8 TIPS)

Nothing ruins the joy of working out more than nagging joint pain.

Not only is it physically uncomfortable, but it often stalls progression by preventing you from training at peak performance.

The knee joint is an area that very commonly acts up in many trainees, especially during the squat.

However, squats are not inherently dangerous. In fact, when performed with proper technique, they can actually strengthen the knees and reduce the risk of future injuries .

But what should you do if you experience knee pain during squats?

In this post I’ll be going over 8 tips you can implement to treat the underlying causes, eliminate the discomfort and get back on the road to squatting pain-free.

Squats & Knee Pain: 8 Tips To Follow

#1 – do a proper warm up.

This is the first and most basic place to start if you’re experiencing knee pain while squatting.

Doing nothing more than one or two quick warm up sets and then jumping straight into the heavy weights is not enough if you truly want to minimize the strain on your knees and optimize training performance.

A properly executed warm up will lubricate the joints with synovial fluid, improve mobility and activate your central nervous system for greater strength, power, and faster reaction time.

#2 – Spread Your Knees Outward

A big problem many lifters run into during the squat is having their knees buckle inward.

We call this a “knee valgus,” and it’s a very common cause of knee pain from squats.

Knee valgus increases the tension on the knee joint and places a lot of stress on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), potentially leading to patellofemoral pain syndrome or even ligament tears.

The first step in preventing this is to simply be aware of what your knees are doing during the squat and to ensure that they remain in line with your feet rather than collapsing inward.

A useful cue for this is to focus on “spreading the floor apart” with your feet.

Adopting a squatting stance with your toes pointed slightly outward helps as well.

If simply adjusting your form doesn’t take care of it completely, there could be other underlying issues at play.

One of the most common reasons behind inward collapsing knees are weak and inactive glutes.

When the glutes don’t fire properly during a squat, they’re unable to resist the inward force your upper legs undergo during the lift, causing your knees to buckle.

Performing some very light “pre-activation” work for the glutes prior to your squatting sessions can be helpful here, as can directly training the glutes using movements such as hip thrusts and banded sidewalks.

Another helpful tip is to squat with a mini-band wrapped your knees, as this will increase the strength and activation of the glutes and force you to keep your knees spread outward throughout the exercise.

Another common cause of knee valgus is tight ankles.

Insufficient ankle mobility will pull your feet inward when you reach the lower part of a squat. Once this happens, your knees will follow automatically.

Lifters who are limited by their ankle flexibility can self-myofascial release the tissues in the calves, ankles and feet in order to loosen things up and improve ankle mobility. A lacrosse ball or other SMR tool can be used for this. ( This video covers some techniques you might find helpful.)

Lastly, knee valgus can often be fixed by simply re-learning the squat using lighter loads.

Focus on keeping your knees in the proper position and getting those glutes to fire consistently, and then gradually begin adding weight again while maintaining the correct form.

#3 – Stop Pushing Through Your Toes

When you push through your toes during the squat (or on any compound quad exercise such as leg presses, lunges, or deadlifts ), you shift the tension forward and direct more stress onto the knees.

Instead, make sure to evenly distribute the weight over your entire foot.

One form cue that will help out with this is to think about “sitting back” as you descend on each rep.

Box squats are a very helpful exercise to learn how to do this correctly.

Since you can maintain a more upright shin angle with this variation, lifters with beaten up knees will often feel less pain on the box squat in comparison to regular squats.

Don’t push your hips too far back though, since this will create greater flexion at the hip joint.

When overdone, this can turn your squat into a good morning exercise and lead to more stress on your lower back .

Find a middle ground here between sitting back during the squat but without allowing your torso to collapse forward.

This will help to prevent knee pain during squats and keep your lower back protected as well.

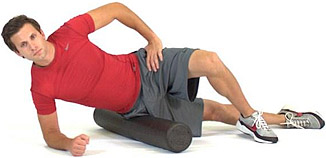

#4 – Self-Myofascial Release Your IT Band

The Iliotibial Tract (IT) band is a thick strip of connective tissue that is attached to your knee joint. It helps abduct and laterally rotate the hip and is essential for the stabilization of your knees.

However, squatting (and running) regularly can cause the IT band to become excessively tight, which pulls and creates tension on the knee joint.

While a deep tissue massage from a skilled practitioner would be ideal, self-myofascial release techniques (SMR) are a good alternative to relax those overly contracted muscles and release built-up trigger points.

The most well-known SMR technique is foam rolling.

Simply place a foam roller between your body and the ground and apply pressure to the area you’re trying to treat by slowly rolling back and forth.

Here’s how you can SMR your IT band:

Once you’ve gotten into position, perform long, slow rolls running from your hip all the way down to just above your knee. If you find an area that is particularly tender, stay on that spot for a bit longer until the pain subsides.

You’ll likely find this very painful if it’s your first time, but the discomfort will gradually decrease with repeated sessions.

#5 – Self-Myofascial Release Your Adductors

The adductors are a group of muscles located at your inner thigh.

Their primary function is to bring your legs toward the midline of your body. Aside from that, they also assist with hip flexion, hip extension and hip rotation.

The problem?

The adductors muscles – just like your IT band – have a tendency to become overly tight.

Tight adductors can increase your risk of knee pain on squats by contributing to knee valgus as discussed above, as well as by preventing proper stabilization of the femur.

You can use a foam roller for this as well along the inner portion of your thigh.

#6 – Use A Pair Of Knee Sleeves

Knee sleeves are made up of a thin layer of rubber or neoprene and are wrapped around your knees during the squat.

They help to lubricate the joints by trapping in heat, as well as providing additional support to the knees throughout the lift.

Knee sleeves should not be used as a “crutch” for bad form, and they certainly aren’t a solution to knee pain during squats in and of themselves.

However, if you’re squatting with proper form and are working on fixing some of the potential underlying issues addressed above, knee sleeves can be used (at least temporarily) to provide a bit of extra support.

#7 – Squat Deeper

Although it may seem counter-intuitive, squatting with a deeper range of motion may actually be superior for knee health.

One analysis found that full squats produce less stress on the knee joint and have a lower risk of injury than partial squats. ( 1 )

The researchers also found that the highest force on your knees during a squat is when your upper legs are parallel to the floor.

In addition, full squats force you to use a lighter weight which not only reduces the stress on the knee joints but also on the lower back as well.

#8 – Do Front Squats

If you’ve tried all of the tips above and that stubborn knee while squatting still won’t subside, another option is to take a break from regular back squats and try performing front squats instead.

Despite the fact that front squats cause more forward knee travel, they produce less stress on your knee joint overall and may be better for long-term knee health. ( 2 )

They’re much easier on the lower back as well.

Here is what the researchers concluded in the study linked above:

“The front squat was as effective as the back squat in terms of overall muscle recruitment, with significantly fewer compressive forces and extensor moments. The results suggest that front squats may be advantageous compared with back squats for individuals with knee problems such as meniscus tears, and for long-term joint health.”

If front squats aren’t doing the trick either, then you’ll probably just be best to take a break from squatting movements altogether to give your knees a chance to heal.

Try replacing them with another compound leg exercise such as a leg press if you find it more comfortable. Going with a lighter weight/higher rep approach would probably be helpful as well.

Squats & Knee Pain: The Bottom Line

There are many benefits to squats , but you can’t do them if you’re injured.

Conversely, it’s been a long-held belief that squats are bad for your knees. However, when performed properly, squats are the single most productive lower body exercise available and are safe on the knees as well.

In fact, they can even improve the health of your knees joints and prevent future knee injuries as long as your technique is on point.

If you’ve been experiencing nagging knee pain on squats (or just want to minimize knee strain during the exercise to prevent future injuries), implementing the 8 tips above should take care of the issue for you.

Read more about leg extension knee pain to protect your joints in that exercise, too.

If you found this article helpful, make sure to sign up for your FREE custom fitness plan below...

Suggested Articles

Featured comment.

Thanks for checking out my article! I hope you found the information useful. Feel free to leave a comment below if you have any questions and I\'ll get back to you as soon as I can.

If you did enjoy this post, don\'t forget to sign up for my newsletter that delivers science-based, no B.S muscle building and fat loss tips, macro-friendly recipes, motivational strategies and more straight to your inbox every week:

==> http://www.SeanNal.com/newslet...

And if you\'re into social media, make sure to connect with me on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and more for additional fitness tips and updates:

==> http://www.SeanNal.com/connect...

Thanks for checking out my article! If you found it helpful, make sure to subscribe to my YouTube channel and follow on Instagram for more daily training and nutrition tips.

If you need further help getting onto the right track with your fitness goals, you can also sign up for a free customized program from me here:

https://www.SeanNal.com/free-custom-fitness-plan.php

ABOUT SEAN NALEWANYJ

RECOMMENDED POSTS

- How Much Muscle Can You Gain Naturally, And How Fast?

- Not Losing Fat? 20 Cutting Diet Mistakes To Avoid

- 7 Ways Supplement Companies Are Ripping You Off

- How To Build Round "3D Delts" That Pop (4 Exercises)

- The Best Cardio Exercises To Burn Fat And Get Lean

- Not Gaining Strength In The Gym? (12 Simple Fixes)

- The #1 Cutting Diet To Achieve A Lean Physique

- 10 Ways To Increase Testosterone Levels Naturally

Most Recent Posts

- 7 “RED PILL TRUTHS” ABOUT BUILDING MUSCLE YOU NEED TO KNOW

- 20 COMMON GYM MISTAKES YOU NEED TO AVOID

- THE TOP 5 WORST PRE-WORKOUTS ON THE MARKET

Looking For Something Specific?

- For Individuals

- Benefit Leaders and Health Plans

- Our Approach

- Learning Center

- Knee Pain While Squatting: Tips and Exercises to Prevent It

Learn the possible causes and best remedies for knee pain while squatting, including at-home exercises to keep your knees strong and resilient.

- Hinge Health Learning Center

Table of Contents

All hail the knee: It's our biggest joint, and responsible for our ability to walk, run, jump, climb stairs, sit, and stand back up. So it’s natural to worry when your knee starts to hurt — and hurt during specific activities like squatting. Just about anyone can experience this type of pain because we squat so much as part of our day. “Every time you sit or stand from a chair or a couch, you’re squatting,” says Cody Anderson, PT, DPT, a physical therapist at Hinge Health.

If squatting irritates your knee, you may start to unintentionally — or intentionally — avoid that movement. “If you’re retrieving something from a low cabinet, for example, you may bend more from the back and the hips instead of the knees,” says Dr. Anderson. While this is an understandable adaptation, this change in mechanics can lead to other problems down the road, and can actually prevent your knee from getting stronger and more resilient.

Here, learn about some common causes of knee pain while squatting, myths about the “perfect” way to squat, and exercises to help your knee stay strong.

Our Hinge Health Experts

Cody anderson, pt, dpt, jonathan lee, md, mba, dylan peterson, pt, dpt, tap into pain relief. anytime, anywhere with our app., why does my knee hurt when i squat and how bad is it.

Knee pain during squatting can happen for a lot of reasons, including a sudden uptick in physical activity, repetitive workouts, or an underlying issue in the joint. Lack of activity or a sedentary lifestyle can also cause the knee joint to lose mobility and range of motion, making it more sensitive to pain when you squat. Many people experienced this during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example. “During the early days of the pandemic, many people were not as active. And an increase in home deliveries meant we were less likely to be in the store, squatting to get things off the shelf. As people started to go back to their usual routines, they may have found that squatting caused pain when it didn’t before,” says Dr. Anderson.

Knee pain when squatting may feel like a dull ache, a pulling sensation, or a sharp pain. One common misconception is that a sharper pain must mean a bad injury and worse outcome, but this is not necessarily true, says Dr. Anderson. “A sharp pain in the knee usually indicates a more notable irritation or flare-up compared to a dull ache that builds. A sharp pain is the brain saying, ‘I’m not ready for that movement right now,’” says Dr. Anderson. But it doesn’t necessarily indicate that an injury is worse or will take longer to heal.

Common Causes of Knee Pain When Squatting

Here are some common contributing factors to knee pain when squatting. No matter what the primary cause of your knee pain when squatting is, movement and targeted exercises are usually a first-line treatment for each of these issues. They help strengthen the knee to reduce pain and prevent pain flares from occurring in the future.

Patellar tendinitis. The patellar tendon is located just below the kneecap. Repetitive force through the patellar tendon from activities like repeated jumping (often called jumper’s knee ) can contribute to inflammation or swelling just below the knee. This can contribute to knee pain when squatting for some people.

Quadriceps tendinitis. The quadriceps tendon is located just above the kneecap and connects the quadriceps muscles (front thigh) to the top of the kneecap, helping you straighten your knee during activities like climbing stairs, walking, running, and jumping. If the quadriceps tendon becomes strained or irritated, you’ll feel pain just above the kneecap.

Patellofemoral syndrome. This condition can cause a dull ache behind or around the kneecap and is caused by irritation in those areas. It may get worse during activities such as squatting and climbing stairs. It can also be referred to as runner’s knee because it’s common among athletes, but anyone can develop patellofemoral syndrome, regardless of activity level.

Meniscus tear. Just as it’s normal to develop gray hair on your head or wrinkles on your skin, it’s normal for the cartilage that cushions the knee joint to change with age. While these changes are often unnoticeable, they can contribute to knee pain, stiffness, swelling, or reduced range of motion for some people. You may also feel a catching or locking sensation.

Osteoarthritis. Similar to the meniscus, it’s normal for the articular cartilage that cushions the knee joint to change with age. If these changes contribute to friction in the knee joint, you may experience aches or stiffness that can make everyday movements, including squats, more difficult.

Weak glute muscles. Research shows that working the glutes, inner hip, and inner thigh muscles can help reduce knee pain. If you have pain with squatting and your knees cave inward during a squat, try strengthening your glute muscles to see if it helps, suggests Dr. Anderson. Start with the standing side leg raise (instructions below). Know that knees caving inward during a squat isn’t necessarily a bad thing, or something that contributes to pain, but it may indicate a lack of glute strength which can be a factor in the bigger picture of your knee pain.

Limited ankle mobility. Everything in the body is connected. So if your ankle has a limited ability to flex forward or adjust side to side, it ultimately affects the angle at which your knee bends and it may force your knee to assume a position that’s more stressful for you. Simple at-home exercises can improve your ankle’s range of motion (see prevention tips and exercises below).

Too little movement throughout the day. Staying in the same position for too long can be irritating to your joints and make them stiffer. There’s no right or wrong way to sit or stand throughout the day. The most important thing you can do to prevent and manage stiff joints is to change positions and move throughout the day. If you have to sit a lot during the day, make sure to change positions and take movement breaks. Same with standing. That’s why our Hinge Health physical therapists always say your next position is your best position .

Treatment Options for Knee Pain During Squatting

If you overdid it and your knee is inflamed, these remedies can help you through the worst of the pain, until you're ready to resume your normal activities again.

For an overuse injury , try modifying your activities. You may need to scale back on certain activities that cause a noticeable uptick in your pain to give your knee time to recoup, but it’s important to keep moving in some capacity. Movement delivers healing nutrients to the joint and ensures that it stays strong and resilient.

For inflammation, try:

Icing your knee for 10 minutes after activity.

Over-the-counter (OTC) medication such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), naproxen (Aleve), and acetaminophen (Tylenol) to help reduce pain and swelling. It’s important to make sure that you are safely able to take these medications, based on your medical history.

Compression (like a knee sleeve), to potentially help to keep the swelling under control.

For stiffness try using heat before activity, such as a heating pad for 10 minutes. Warming up the tissues can help make them more pliable and resilient when moving.

When to See a Doctor

Most cases of knee pain during squatting are nothing to worry about and resolve with activity modifications and other conservative measures. If you have excessive swelling that lasts for several days and happens in conjunction with squatting, see your medical provider. There may be an underlying medical issue that requires evaluation, says Dr. Anderson.

The Truth About the ‘Best’ Way to Squat

Spoiler alert: There is no such thing as a “perfect” squat. “People’s bodies are so variable that it’s really hard to come up with one form for everyone,” says Dr. Anderson. The squat technique below is commonly recommended as it works for most people. However, there may be good reasons your body has trouble following these instructions to a tee. The important thing is to listen to what your body is telling you during a squat so you can adapt your squat to meet your own unique needs.

General Squat Form Recommendations:

Keep your feet flat on the ground. Think about the inside and outside balls of your foot and your heel — these three points should all be on the ground, says Dr. Anderson.

Stand with your feet hip-width apart.

Keep your knees in line with your feet. In other words, you want your knees to rest over your feet, not forward or behind them.

Hold your chest up and keep your core engaged.

When squatting, move your hips back, as if you are about to sit on a chair behind you.

Try to keep the middle of your knees in line with the space between your second and fourth toes throughout the entire movement.

What It Means If:

You are very upright. An upright position when squatting tends to mean you’re heavily engaging the quadriceps muscles (top of the thigh). This could happen because of your body mechanics — if you have a long torso and shorter thigh bones (common in powerlifters, for example). Or, you may not be fully engaging your glute muscles.

You are very bent forward. This means you are engaging your hips and back more than your quads and knees. This could mean you have an opportunity to increase your knee range of motion, or that you’d benefit from strengthening your quads. (Start with the knee extension, below).

Squat Myths to Bust

Myth: It’s really bad if your knees go over your toes. If you’re like most people, you’ve been told at some point to not let your knees go past your toes when you squat. It’s true that you might not be ready for your knee to go over your toes just yet, because there can be increases in knee pressure as your knees go farther over your toes. However, it’s not a bad thing to have your knees extend past your toes when squatting and this advice can make it seem really dangerous. The knee naturally goes over your toes all the time in daily life — like every time you go down the stairs, says Dr. Anderson. So just know that if your knee does go over your toes, you are not damaging the joint. You are just challenging your knee more.

Myth: You shouldn’t let your knee cave inward (known as knee valgus) during a squat. In excess, knee valgus could signal weak muscles or poor form. But variations in movement are normal. If you are naturally a bit knock-kneed, for example, your body may be used to your knee moving inward. “If you’ve been moving this way for 25 years with no problem, chances are this isn’t the main cause of your pain and you may not need to correct this,” says Dr. Anderson.

Myth: It’s bad to turn out your toes. If your toes turn out when you squat, it may be because of how your hip bones are aligned. In that case, it’s okay to do what feels most natural for your body. In fact, turned-out toes can actually allow you to squat deeper with less stiffness.

How to Prevent Knee Pain When Squatting

Put simply: Motion is lotion . To keep your knees healthy and strong for life, the key is to stay active in whatever way works for you. The CDC recommends a minimum of 150 minutes of cardiovascular exercise a week, and strength training twice a week can keep your muscles strong and protect your joints from stress. Here are specific ways to make sure your physical activity nurtures strong, resilient knees.

Indulge in ‘movement snacks.’ Since prolonged sitting can irritate the knees, it’s crucial to stand up and move around frequently, even if it’s just for a minute or two. “Giving your knees movement throughout the day is actually better than if you sit all day and then hit the gym at night,” says Dr. Anderson. Set an alarm on your phone to remind yourself to take hourly mini-breaks for movement, whether it’s walking around the block or just to the bathroom, or stretching near your seat.

Improve knee mobility — gently. “When we’re talking about improving knee pain, a lot of times we’re really talking about improving your range of motion,” says Dr. Anderson. Here are two ways to help your knee bend to its full range of motion while using little or no weight. This can help you bend your knees more deeply during activities like squatting and build up your confidence about moving the joint.

Knees to chest stretch : Lay on your back and pull your knees to your chest, grasping the back of your thighs or the top of your shin bones. Breathe deeply and hold for 30 to 60 seconds. For an even gentler stretch, do this one leg at a time.

Child’s pose . This popular yoga pose mimics a squat — but without supporting the weight of your body. Kneel with your knees shoulder width apart, feet together, and buttocks down toward your heels. Lean forward and place your hands on the ground for support, and breathe deeply. Hold for one to two minutes Improve ankle mobility. Because the knee and the ankle work together to move the leg, improving ankle mobility helps your knee stay in optimal alignment as well. Improve your ankle’s range of motion with a knee-to-wall stretch . Here’s how to do it:

Place your bare foot flat on the floor about three inches from the wall, then bend your knee forward until it hits the wall. Move your foot back a half inch or so until you can no longer touch the wall with your heel on the ground.

Slowly rock your knee toward the wall and hold for three to five seconds. Relax back to the starting position and repeat six to eight times before repeating on the other side.

If your knee begins to touch the wall during the repetitions, this is a sign your ankle mobility is improving.

Engage your hip muscles. “Some people naturally do a very knee-dominant squat, meaning they are very upright and they are just not used to using the hip muscles,” says Dr. Anderson. ”Sometimes, if we give people hip exercises, they become better able to engage their hip muscles and adjust so they can get some pain relief,” says Dr. Anderson. And sometimes, simply becoming more aware of how you’re moving and using your muscles can make a big difference. Get started with the standing side leg raise below.

Exercises for Knee Pain Relief

Relieve your pain today with our app.

Curated exercise playlists just for you by physical therapists

These exercises recommended by Hinge Health physical therapists take you through a low, medium, and high load to build up to doing full squats. Start by doing these three days a week, and slowly increase to every other day or daily.

The information contained in these videos is intended to be used for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice or treatment for any specific condition. Hinge Health is not your healthcare provider and is not responsible for any injury sustained or exacerbated by your use of or participation in these exercises. Please consult with your healthcare provider with any questions you may have about your medical condition or treatment.

PT Tip: Try This High-Heel Squat Trick

It’s true that general squat form recommendations include keeping your feet flat on the ground. But if you have knee pain during squatting, there’s a modification you can try that may help: Raise your heels off the ground. You can do this by resting your heels on a very small step (about two inches), a piece of plywood, a book, or anything else you have lying around the house. You can also do your squats barefoot and place your exercise shoes behind you so you can place your heels on the toes of your shoes.

Elevating your heels can help knee pain in a lot of ways, such as allowing you to increase squat depth, increasing the range of motion at the knees, and increasing activation of the quadriceps. High-heel squats can also be especially helpful for people who struggle with ankle mobility because it can improve their alignment during a squat, says Dr. Anderson.

How Hinge Health Can Help You

If you have joint or muscle pain that makes it hard to move, you can get the relief you’ve been looking for with Hinge Health’s online exercise therapy program.

The best part: You don’t have to leave your home because our program is digital. That means you can easily get the care you need through our app, when and where it works for you.

Through our program, you’ll have access to therapeutic exercises and stretches for your condition. Additionally, you’ll have a personal care team to guide, support, and tailor our program to you.

See if you qualify for Hinge Health and confirm free coverage through your employer or benefit plan here .

This article and its contents are provided for educational and informational purposes only and do not constitute medical advice or professional services specific to you or your medical condition.

Looking for pain relief? Check if your employer or health plan covers our program

Almeida, G. P. L., Rodrigues, H. L. das N., Coelho, B. A. L., Rodrigues, C. A. S., & Lima, P. O. de P. (2021). Anteromedial versus posterolateral hip musculature strengthening with dose-controlled in women with patellofemoral pain: A randomized controlled trial. Physical Therapy in Sport, 49 , 149–156. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2021.02.016

Bump, J. M., & Lewis, L. (2022). Patellofemoral Syndrome. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557657/

Cannell, L. J., Taunton, J. E., Clement, D. B., Smith, C., & Khan, K. M. (2001). A randomised clinical trial of the efficacy of drop squats or leg extension/leg curl exercises to treat clinically diagnosed jumper’s knee in athletes: Pilot study. British Journal of Sports Medicine , 35 (1), 60–64. doi:10.1136/bjsm.35.1.60

Caterisano, A., Moss, R. F., Pellinger, T. K., Woodruff, K., Lewis, V. C., Booth, W., & Khadra, T. (2002). The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research , 16 (3), 428–432.

Move More; Sit Less . (2022, June 2). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/index.htm

Mulcahey, M. K. (2022, February). Common Knee Injuries. OrthoInfo — American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.orthoinfo.org/en/diseases--conditions/common-knee-injuries/

Deshpande, B. R., Katz, J. N., Solomon, D. H., Yelin, E. H., Hunter, D. J., Messier, S. P., Suter, L. G., & Losina, E. (2016). The number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the United States: Impact of race/ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care & Research , 68 (12), 1743–1750. doi:10.1002/acr.22897

Sheth, N. P. (2022, April). Osteoarthritis. OrthoInfo — American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.orthoinfo.org/en/diseases--conditions/osteoarthritis/

Wittstein, J. R. & Wilkerson, R. (2021, September). Patellar Tendon Tear. OrthoInfo — American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.orthoinfo.org/en/diseases--conditions/patellar-tendon-tear/

Mulcahey, M. K., Hettrich, C. M., & Liechti, D. (2020, October). Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. OrthoInfo — American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.orthoinfo.org/en/diseases--conditions/patellofemoral-pain-syndrome/

Pereira, P. M., Baptista, J. S., Conceição, F., Duarte, J., Ferraz, J., & Costa, J. T. (2022). Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome Risk Associated with Squats: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 19 (15), 9241. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159241

Raj, M. A., & Bubnis, M. A. (2022). Knee Meniscal Tears. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431067/

Foran, J. R. H. (2020, June). Total Knee Replacement. OrthoInfo — American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.orthoinfo.org/en/treatment/total-knee-replacement/

Related Articles

OPT OUT OF SALES, SHARING, AND TARGETED ADVERTISING

Manage consent preferences, strictly necessary cookies.

These cookies are necessary for the website to function and cannot be switched off in our systems. They are usually only set in response to actions made by you which amount to a request for services, such as setting your privacy preferences, logging in or filling in forms. You can set your browser to block or alert you about these cookies, but some parts of the site will not then work. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable information.

Performance Cookies

These cookies allow us to count visits and traffic sources so we can measure and improve the performance of our site. They help us to know which pages are the most and least popular and see how visitors move around the site. All information these cookies collect is aggregated and therefore anonymous. If you do not allow these cookies we will not know when you have visited our site, and will not be able to monitor its performance.

Functional Cookies

These cookies enable the website to provide enhanced functionality and personalisation. They may be set by us or by third party providers whose services we have added to our pages. If you do not allow these cookies then some or all of these services may not function properly.

Targeting Cookies

These cookies may be set through our site by our advertising partners. They may be used by those companies to build a profile of your interests and show you relevant adverts on other sites. They do not store directly personal information, but are based on uniquely identifying your browser and internet device. If you do not allow these cookies, you will experience less targeted advertising.

Cookie List

Knee Pain After Squats: How to Get Rid Of It

You hear it everywhere you turn – if you wanna get big, especially in the lower body, you gotta squat. That’s ok for those with healthy joints, but what about those of us who have to put up with knee pain? Do we have to eliminate this fundamental mass builder from our routine, or is there a way to squat without suffering debilitating knee pain as a consequence?

Let’s find out.

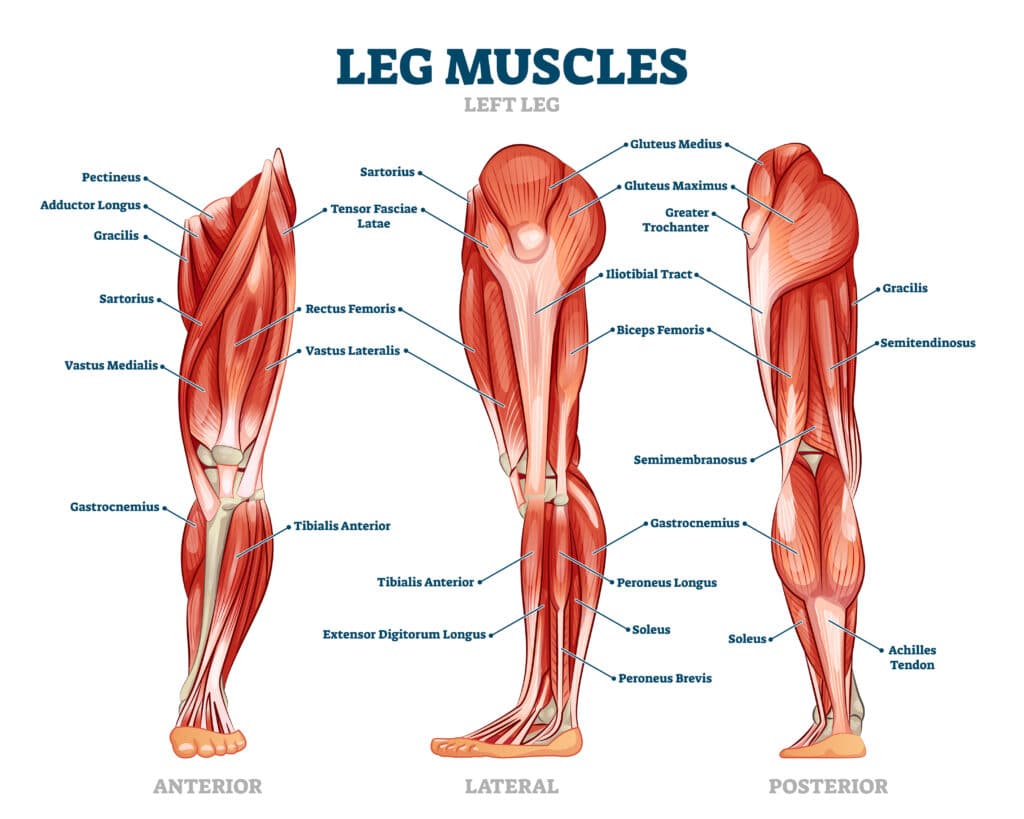

Knee Anatomy

Your knee is a hinge joint, but one that does not have a fixed axis. Instead, it is able to glide and rotate. As a result, the axis of the joint constantly changes. This is one of the prime reasons for knee problems.

In order for your knees to work without giving you too much trouble, you need your hamstring and your quadriceps to be of roughly equal strength. Ideally, you should have a hamstring-to-quadricep ratio of one to one.

The knee is comprised of seven types of tissue:

- Bone – the femur, tibia and patella

- Ligaments – this is the connective tissue that connects bone to bone; there are eight interior ligaments and six external ligaments

- Muscle -while there are no muscles in the actual knee joint, those that act on the knee are the quadriceps and the hamstrings

- Tendon – tendons connect the quadriceps and hamstrings to bones of the knee.

- Bursa – this is a pad-like sac that prevents friction from occurring at the point of connection, such as between bone and muscle. The knee contains twelve of these bursa.

- Adipose tissue – this provides padding around the knee joint

- Articular cartilage – this is the connective tissue that allows for fluid movement between the bones of the knee joint. There are two cartilages on the knee joint; the two menisci which cradle the rounded knobs of the lower femur.

Why the Pain?

The knee joint is stuck between the ankle and the hip. Often the reason that squatters end up with pain in that middle joint has nothing to do with the fact that they have ‘bad knees’. Rather, incorrect movement at the hips and ankles lead to collateral damage to the knee. 90% of the time the issue is with the hips. If you do not have the right mechanics of the hip joint while you squat , your lower body will not be able to stabilize itself when you are squatting. As a result of that, your knees will not be able to track up and down in the ideal plane of movement.

In order to ensure that you are squatting with the correct hip alignment there are two key steps that you need to take:

(1) When you get under the bar be sure that your elbows are pointing downward and into your sides, with your head up. This may seem inconsequential, when in fact it is critical. When your elbows are pointing down, your upper and mid back will automatically come into proper alignment and stabilization.

(2) As you start to go down, consciously pull your body down. To do this, activate the hip flexors and contract and squeezing the psoas muscle. This will allow you to stabilize the lumbar spine.

When you practice those two steps, your knees will track directly up and down when you squat. You will not have to artificially recruit the muscles on the outside of the thigh to push back up. As a result, you will not experience the knee pain that you are used to.

What If You’ve Got Patellar Tendonitis?

Patellar tendonitis will result in stabbing knee pain that goes right through your knee caps into your inner knee joint after doing even light squats. But even that doesn’t mean that you have to forego the squat exercise. The solution to patellar tendonitis pain is to do the box squat.

Patellar tendonitis results from the fact that the tendons attached to the knee are being relied on too much to carry the load of the weight you are squatting. Your goal is for the quads, hamstrings and glutes to take that load. Your job is going to have to be to train those tendons to hold back and allow the muscles to do the job. Squatting to a box will allow you to do just that.

The most common reason that squatters over rely on the patellar tendon is that they have a psychological fear of not being able to get back up during the squat descent. As a result, they rely on the patellar tendon rather than the quads as they are going down. They will bend the knees first because they do not want the quads to take the load. They do not have the confidence that their quads will be strong enough to get them out of the hole. When you use a box, however, that problem is eliminated.

You should squat to a box height of about seventeen inches. You will probably use a bench as your squat box and the height of most benches should be set at about that level. Place the bench between your legs. This will ensure that you are squatting with a wide stance, which will turn out your toes and bring more hip activation into play. Your hips will lead on the descent rather than your knees. Lean back with the hips and then start descending. The bench will provide you with the security that you won’t fall to the ground.

Rather than resting on the box, just touch it with your butt and then power back up, again driving through the hips. Using the box will also recruit more involvement from the hamstrings and glutes.

Knee Tracking

The line of travel of your knee is critical to squatting pain free. You want your knee to be pushed out as you go up and down so that it is in line with your toes. This will minimize any interior or external rotation of the tibia.

Pushing Through the Heels

Inexperienced squatters have a tendency to push through the front of the foot as they push up out of the hole. This is never a good idea and especially not when you are experiencing knee pain. Pushing through the toes will concentrate the tension of the exercise forward and place more stress on the knees.

You should ideally displace your weight over your entire foot. As you drive out of the squat, visualize pushing into the ground through your heels. This will go a long way to helping to achieve the ideal body tracking that you are after.

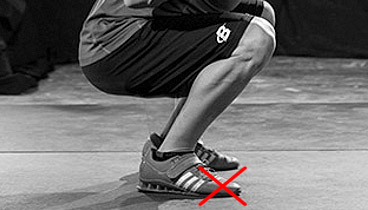

What About Squatting Shoes?

The shoes that you wear while squatting can have a great impact on your knees while squatting. Most general running or casual shoes do not have the stability or the arch support to lower you to squat efficiently. For many people, their feet have a natural tendency to pronate when they squat. This will also force the knees to come inward. This leads to a chain of problem reactions including strain on the ligaments, excessive sheer force and misaligned tracking of the patellar.

Wearing the right type of squatting shoes can help to prevent these effects.

Squatting shoes also allow you to have a raised heel and a solid heel cup. A solid heel support will stop the heel from moving laterally, which will cause a lot of strain on your knee joint. The raised heel will also place your body in the proper alignment to move up and down with proper patellar tracking.

What About Bar Positioning?

Does the position of the bar on your back affect your knees? Yes, it does. The back squat gives you the choice of either a high bar or a low bar position. The high bar position puts the bar across the upper trapezius muscles, whereas the low bar will have it positioned across the rear delts. With the bar higher, you will end up with a more upright squat position, less hip flexion, and more forward migration of the knee. This is not what you want if your goal is to reduce knee pain .

The low bar squat will naturally result in more forward lean, more hip flexion and less migration of the knee. This is the preferred form to reduce pain in the knee area.

How About Knee Wraps?

Should people with knee pain use knee wraps?

The answer is no – unless you are squatting at more than 85% of your one rep maximum. The problem is that a wrap absorbs the stress and not the tissues of the knee. This means that your tissues never get stronger. If you are going to wear knee wraps be sure to purchase wraps that are heavy as they will provide the greatest level of knee protection. You also want the wrap to have a length of about 18 feet. Allowing you to wrap it around your knee multiple times. You do not, however, want wraps that provide a lot of elastic stretch.

What About Foot Position?

The health of your knees has a direct correlation to your foot stance. At the end of the day, you will have to work out your ideal foot stance in accordance with your own anatomical peculiarities. However, there are some basic foot stance guidelines that you should take into account:

- Point your feet slightly outwards. This is the strongest stance for quad recruitment.

- Do not have an overly wide stance. This will put too much pressure on the patellar tendon.

- Do not allow your knees to cave in during the drive out of the hole. This will place too much pressure on the medial ligament.

- Do not use a close stance. This will place too much compression on the knee.

- Keep your feet locked in position during the set. Do not allow them to fidget around.

Try Front Squats

The front squat is a great exercise that places more emphasis on the quads and less on the hamstrings and glutes. It has also been shown to be less troublesome to the knees. According to a 2009 study . . .

“The front squat was as effective as the back squat in terms of overall muscle recruitment, with significantly fewer compressive forces and extensor moments. The results suggest that front squats may be advantageous compared with back squats for individuals with knee problems such as meniscus tears, and for long-term joint health.”

Warming Up to Prevent Knee Pain

As we’ve already identified one of the main causes for knee pain when squatting has to do with the patellar tendon. Warming the patellar before you get under the rack is vital in order to alleviate the problem. Be sure to do lots of dynamic stretches before you tackle squats.

The Exercises

Here is a non-weight circuit that you can perform in order to loosen up the entire knee area prior to adding weight to your squat.

Partial Pulse Squats x 10

With this move you are only moving through the first 6-8 inches of the squat. You will be pulsing up and down in a ballistic movement.

Side Step Pulse Squats x 10 (each direction)

This is the same movement as the previous exercise, but with every squat, lunge to the side a few inches. Maintain, short, quack and ballistic movements.

Drop Set Pulse Squats x 10 (each direction)

This time as you pulse down you will step back into a quarter turn. Rotate from side to side, allowing your hips to open up.

Jack Pulse Squats x 10

This pulse squat variation involves perform mini jumping jacks as you pulse up and down.

Perform this circuit three times with about 30 seconds of rest between each circuit before you go into your first set of weighted squats and you will take a lot of the pressure off the knees.

Check out this article for ideas on which squat workout is right for you.

Knee pain doesn’t have to mean that you are resigned to missing leg day. It doesn’t even mean that you have to give the squat rack a wide berth. By implementing the guidelines provided in this article, you will be able to squat without the pain. In so doing, you’ll once again be benefiting from the single best exercise for building strength, size and power.

- Research Reviews

- Masterclass

Is it Safe for Knees to Pass Toes During a Squat

One of the biggest training myths out there is that the knees shouldn’t travel forward past the toes during a squat, otherwise your knees will explode… or something like that. This myth, like a lot of other myths, likely started with an old study that was misinterpreted and this incorrect knowledge being passed down over years and years to end up with the false but widely held beliefs we have today – myths.

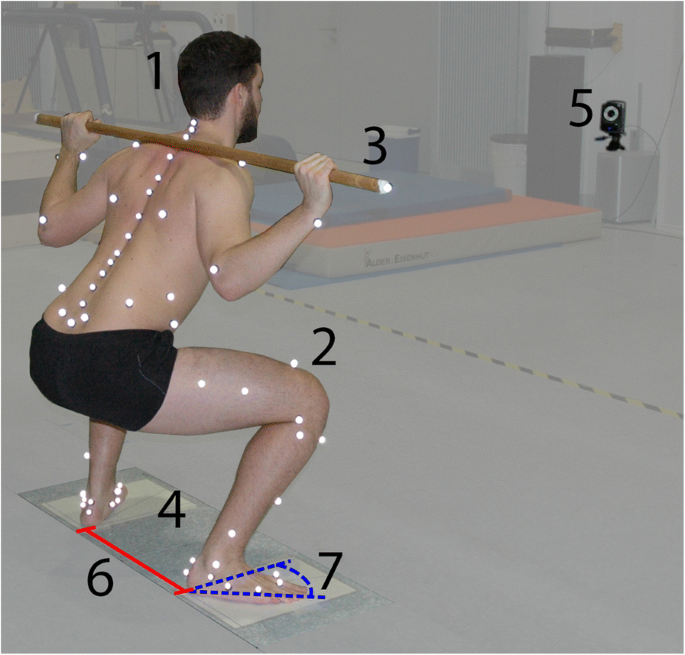

One such study that may have contributed to this belief was conducted in 2003 by Fry et al. (1) , who looked at how joint torques at the knees and hips changed when restricting forward knee travel during a squat. As you can see in the picture below, in ‘A’ the knees were allowed to travel forward freely, whereas in ‘B’ they were restricted to not travel forward past the toes at all.

What they found was that by limiting forward knee travel it simply shifted the stress from the knees to the hips/low back. So while squatting with restricted forward knee movement showed a 22% decrease in knee torque, there was a 1070% increase in hip torque! This is a LOT more work for the hip and low back musculature to perform, and is a potentially more dangerous squatting method for the low back.

Therefore, while it is true that anterior knee stress increases as the knees come forward during a squat, it is important to know that the amount of stress from the knees going slightly in front of the toes is still WELL within the limits of what the knee can handle (2). Reference: Schoenfeld 2010 .

Furthermore, in order to reach FULL depth in the squat the knees almost always have to move forward past the toes. Olympic weightlifters are a great example of this, as they need to train at full depth for their sport, and so often squat with their knees past their toes, and with very high loads too!

Caution – knees about to blow!

This myth is also likely perpetuated by the popular ‘knees over toes’ cue, which actually means don’t let the knees collapse inwards or outwards and keep them in line with the feet. This is far more important to follow as it not only ensures efficient force transmission through the knee joint, but also, an inward collapse of the knee (or dynamic knee valgus) has been linked with ACL injuries, so it is likely not a good idea to encourage this movement pattern.

What people also tend to forget is that each type of squat is MEANT to have differing amounts of forward knee travel, due to the varying demands placed on the joints of the lower limb due to the different bar positions. In order of most to least expected forward knee travel in different versions of the squat:

Front squat > High bar back squat > Low bar back squat > Box squat

So don’t go expecting someone to have the same amount of forward knee movement in a front squat compared to a low bar back squat.

Hopefully now it’s pretty clear that there is no need to restrict forward knee movement altogether when squatting. However, it’s probably not a bad idea to limit ‘excessive’ forward knee travel to prevent undue strain on the patellar tendon and patellofemoral joint. And by excessive I’m talking knees being more than 15-20cm in front of the toes every rep in people that squat heavy and often.

Note that there hasn’t been any research to quantify what is ‘excessive’, it is just a figure I have estimated from my own clinical experience.

Having said all of this, there are people who may benefit from limiting forward knee travel during a squat – those with anterior knee pain, i.e. pain at the front of the knees (3) Reference: Rudavsky 2014 .

In this population reducing anterior knee stress may allow for more pain-free squatting. If this is you, I would recommend doing squatting movements that encourage less forward knee travel (or more vertical shins) such as box squats and the powerlifting squat or low bar back squat (4) Reference: Swinton 2012 .

Hope this has shed light on this huge training myth. Happy squatting!

Want to master youth low back pain?

Angela Jackson has done a Masterclass lecture series for us!

“Assessment and Rehabilitation of Low Back Pain in Youth Athletes”

You can try Masterclass for FREE now with our 7-day trial!

- Fry AC., Smith JC, Schilling, BK. Effect of knee position on hip and knee torques during the barbell squat. J Strength Cond Res. 2003 Nov;17(4):629-33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14636100

- Schoenfeld BJ. Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Dec;24(12):3497-506. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20182386

- Rudavsky A, Cook, J. (2014) Physiotherapy management of patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee). Journal of Physiotherapy 60: 122–129] http://www.journalofphysiotherapy.com/article/S1836-9553 (14)00091-5/fulltext

- Swinton PA., Lloyd R., Keogh JW., Agouris I., Stewart AD. A biomechanical comparison of the traditional squat, powerlifting squat, and box squat. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Jul;26(7):1805-16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22505136

Don’t forget to share this blog!

Leave a comment.

If you have a question, suggestion or a link to some related research, share below!

You must be logged in to post or like a comment.

Related blogs

Elevate your physio knowledge every month.

Get free blogs, infographics, research reviews, podcasts & more.

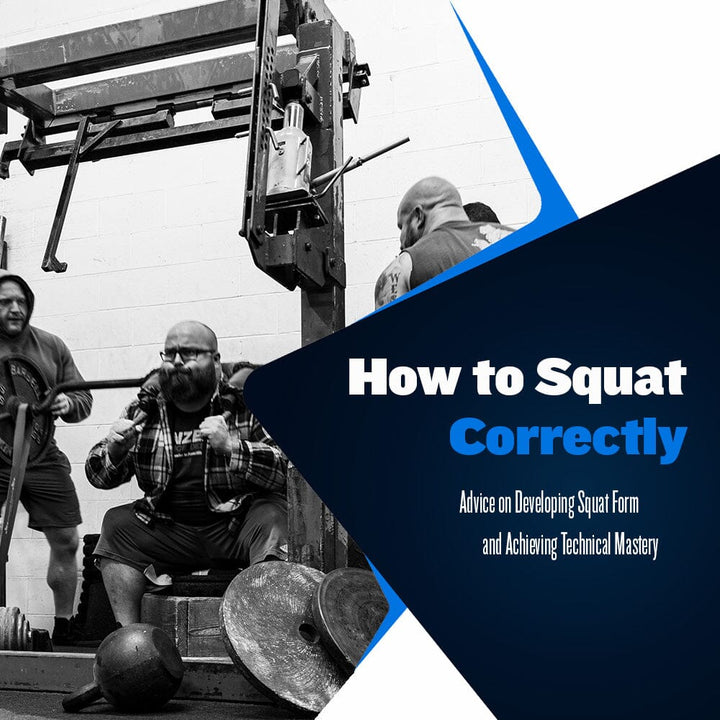

How to Squat Correctly

WSBB Education Sun Aug 20, 2023

One of the most basic and essential barbell exercises is the squat. The squat is an exercise that allows an individual to strengthen their legs, back, and trunk and can provide a myriad of strength and athletic benefits depending on how the exercise is performed and programmed. Whether you are a football player looking to improve sports performance or a powerlifter seeking to add pounds to your total, the barbell squat can be programmed to deliver the desired training results.

The Conjugate Method provides a template allowing the barbell squat to be utilized in many ways. At Westside, we perform squats in one of three ways: during max, dynamic, and repeated effort training. The selected squat exercises can range from a basic barbell or SSB squat to giant cambered bar box squats with forward-pulling bands. A squat variation is a tool, and how we choose to utilize that tool dictates the training outcomes we can expect.

However, to attain expected training results, the athlete must be able to perform a barbell squat proficiently. Failure to execute squat exercises with optimal form leads to reduced training effectiveness, an increased risk of overuse injuries, and an increased risk of catastrophic injury.

As you can see, the squat is a rewarding exercise when performed correctly, but it can set an athlete back if performed without proper form and intent. At Westside, we have taught and corrected squat techniques for many athletes seeking to improve their lower body strength, explosive power, muscle mass, and endurance.

The Anatomy of a Squat

The barbell squat is an exercise that involves and challenges many different muscle groups. This is what makes the squat such an effective exercise: the ability to target multiple muscle groups simultaneously while performing a basic barbell movement. Here are the major muscle groups involved in a barbell squat:

Anterior Chain:

Abdominals / Trunk

Hip Flexors

Posterior Chain:

Erector Spinae

As you can see, the squat trains all the essential lower-body muscle groups efficiently and effectively. This simple barbell exercise is an incredibly valuable training tool for all athletes. No matter the sport you’re preparing for, there is no doubt all of these above-listed muscle groups play a significant role in the execution of basic sports movements.

At Westside, we utilize a variety of specialty barbells and special exercises to target each of the above-listed muscle groups most effectively. These exercises are included to improve the overall technical mastery of the squat while placing specific emphasis on anterior or posterior muscle groups. These exercises enhance squat strength and coordination and help to build a complete athlete.

Basic Squat Execution

When thinking about squat execution, it is essential to remember that no two athletes will squat or perform any lift the same way. For this reason, effective squat coaching is achieved by providing movement guidelines and parameters instead of strict rules that all athletes must follow without considering biomechanical advantages and disadvantages.

Barbell lifts are best coached by providing an athlete with basic instructions that can be easily followed while leaving room for the athlete to find their groove and move most efficiently. Remember that no matter how well-educated or capable a coach is, nobody knows how an athlete should move more than the athlete. Proprioception plays a tremendous role in technical mastery; only the athlete knows how they feel under the barbell.

Here are the basic guidelines we use to coach the barbell squat at Westside Barbell:

First, ensure the rack elevates the barbell to the proper height for a comfortable unrack. For most athletes, this will be the height that places the barbell in the middle of the chest as you walk up to the bar.

Next, set the hands up properly. We recommend that athletes set their hands wide enough for the torso to remain as vertical as possible throughout the movement. The width of the grip will ultimately be determined by the width of the athlete’s back and the shoulder mobility they possess.

Now that the hands have been properly set, we can bring the torso underneath the barbell and set the barbell on the back. This can be done one of two ways - high bar or low bar . Where you place the barbell will largely depend on your trunk and torso size. Typically, leaner athletes benefit from using the high bar position, considering stability and lack of torso lean associated with high bar squatting.

Larger athletes can choose to squat high bar or low bar. Large athletes typically benefit from increased trunk and torso size when using a low bar position, allowing for the spinal flexion and torso lean created by the low bar position to be more tolerable. Low bar also gives a large athlete a biomechanical advantage over the barbell, considering the differing hip and knee flexion levels associated with high bar and low bar squatting.

Once you have determined how to carry the barbell, it is time to unrack it. Unracking the barbell to squat will differ depending on whether you use a typical squat rack or a monolift.

You must unrack and walk the weight out to complete your set when using a basic squat rack. This means an athlete must stabilize, unrack the barbell, walk the barbell out, restabilize, and complete the movement. To do this most efficiently, we want to unrack the barbell with our torso braced as much as possible. Then, we want to take as few steps as necessary to walk the bar out. Two steps are preferable, but if it takes a few extra steps to get your feet set, so be it. Once the feet are set, the athlete will restabilize as much as possible.

When using a monolift all we have to worry about is bracing properly and unracking the barbell. With the monolift, there is no need to be concerned about walking out the weight and finding our foot placement, considering we can place our feet properly before standing up with the barbell.

Now that we have unracked the barbell, it is time to initiate the eccentric portion of the squat. The first move should be a slight sit back of the hips to reduce the amount of forward knee travel as we descend. This is not a significant sitting back of the hips, just a slight movement rearward to give the knee joint and quads a break and maximize the use of the hips, glutes, and hamstrings.

As we sit the hips back, we will simultaneously break at the knees to lower the barbell. During the descent, maintaining a torso as vertical as possible with the trunk adequately braced is critical. The torso position will ensure we maintain control of the barbell, while the trunk brace will act as the brake pad once we transition to the concentric portion of the squat.

While lowering the barbell, we want to maintain a vertical shin position by opening the knees up as much as necessary, depending on the width of our stance. This will help ensure efficient lateral and vertical force transfer to the barbell, creating a stronger and more explosive squat movement.

Once we have completed the eccentric phase of the squat, it is time to reverse the weight and complete the concentric phase of the lift. Provided you have followed the above advice, all that should be left to do is apply adequate force and move the barbell back to the starting position. As the exercise is completed, we will maintain our trunk brace and control the barbell as we return it to the rack.

The Benefits of Squatting

The squat may be the most beneficial movement for all athletes out of the big three barbell lifts. Aside from the deadlift, which can cause issues with fatigue if performed too often, no other barbell lift challenges as many major muscle groups as the squat. Not only does the squat make an athlete bigger and stronger, but it does so rapidly and efficiently.

When you program a squat or squat variation into your training program, you can guarantee you won’t waste your time. At Westside, we use the squat and its many variations to make athletes bigger, stronger, faster, and better conditioned. When considering the number of squat variations and the ability to adjust volume and intensity to manipulate the training effect further, you can see how the squat is a Swiss Army knife-type exercise.

The greatest benefit is that squatting will improve lower body absolute strength. As an athlete, it is vital to increase the absolute strength you possess constantly. Absolute strength is the king of all strengths and determines your maximum strength, power, speed, and endurance. This is achieved by regularly including squat variations during max effort lower training.

The next benefit of squatting is developing lower body explosive power. At Westside, we use the squat and its many variations to perform dynamic effort lower body training. This is done using a three-week wave format, training at specific intensity levels to achieve optimal barbell velocity.

The final benefit of squatting is developing lower body muscle mass and endurance. At Westside, we use the repeated effort method when performing our accessory work. Often, if an athlete lacks lower body muscle mass or work capacity, we program accessory squat work at moderate to high volume and moderate to low intensity.

The squat is an excellent tool to build muscle and improve conditioning, considering the number of muscle groups involved and the energy required to perform multiple multi-rep sets.

Common Squat Mistakes

Depending on your level of experience, you can make various mistakes when performing a barbell squat. However, almost every athlete makes a few common mistakes regardless of their level of strength or experience. The effectiveness of your squat training depends on your ability to avoid errors and perform technically proficient repetitions, so it is essential to know what habits to avoid when squatting.

Here are a few of the most common squat mistakes we have seen athletes make over the years:

Weak Unrack: This occurs when an athlete sets their rack height incorrectly or fails to brace properly before lifting the barbell out of the squat rack. Either way, a weak unrack will cause immediate instability in the squat setup and typically result in poor execution. With the squat, you finish as well as you start, so a poorly managed unrack can lead to disaster.

Weak Brace: This can occur before or after lifting the barbell from the rack. A weak brace means what it says: your brace is weak or nonexistent. This happens due to improper breathing, with the athlete failing to create adequate intra-abdominal pressure. A weak brace will also lead to our next common squat mistake.

Excessive Torso Lean: This mistake occurs when an athlete fails to brace correctly or does not have the strength to control the barbell properly. This results in the torso leaning forward, placing significant strain on the lower back. When this happens, the athlete will look like they are performing a good morning instead of a proper barbell squat.

Collapsing Chest: This can occur due to poor bar placement or a weak upper back. A collapsing chest in the squat means the shoulders are rolled forward, placing great strain on the neck and upper back. This results in a loss of control over the eccentric portion of the lift and can lead to thoracic or cervical spine injury.

Collapsing Knees: This occurs when the knees excessively collapse inward as an athlete applies force out of the hole to complete the concentric phase of the lift. This can occur due to weak hips, a poor trunk brace, or improper squat stance width. When left unchecked, collapsing knees can lead to catastrophic injury.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the proper way to use air to brace during a squat?

A: We want to breathe in deeply, using the air to expand the diaphragm and create adequate intra-abdominal pressure. When done correctly, your trunk will feel rigid and stable without feeling like you’re holding your breath. When done incorrectly, you will feel the air pressure in the chest and face, with the trunk and torso remaining noticeably unstable.

Q: Should I wear a belt when squatting?

A: We recommend wearing a belt when performing a standard squat workout. However, if you are completely new to squatting, we do recommend training with lighter weights and no belt to develop fundamental movement skills without the assistance of a belt

Q: Should I wear knee sleeves or wraps when squatting?

A: Knee sleeves can be worn during any squat or lower body exercise. However, we typically save knee wraps for max effort training or if we plan on performing high or ultra-high rep squat sets and need additional assistance and support.

Q: Box squats or free squats?

A: At Westside, we perform all our dynamic effort squats to a box. With max effort squatting, we will perform a mix of free and box squats. The key is to perform as many free squats during max effort training as necessary to remain proficient in competition-relevant movements.

Q: What squat exercise variations are most commonly used at Westside Barbell?

A: We most often use the back squat, front squat, box squat, and squat vs. bands using a typical squat bar, safety squat bar, buffalo bar, or giant cambered bar.

Find Your Form