- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Voyager Golden Record Finally Finds An Earthly Audience

Alexi Horowitz-Ghazi

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears. Ozma Records/LADdesign hide caption

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears.

The Golden Record is basically a 90-minute interstellar mixtape — a message of goodwill from the people of Earth to any extraterrestrial passersby who might stumble upon one of the two Voyager spaceships at some point over the next couple billion years.

But since it was made 40 years ago, the sounds etched into those golden grooves have gone mostly unheard, by alien audiences or those closer to home.

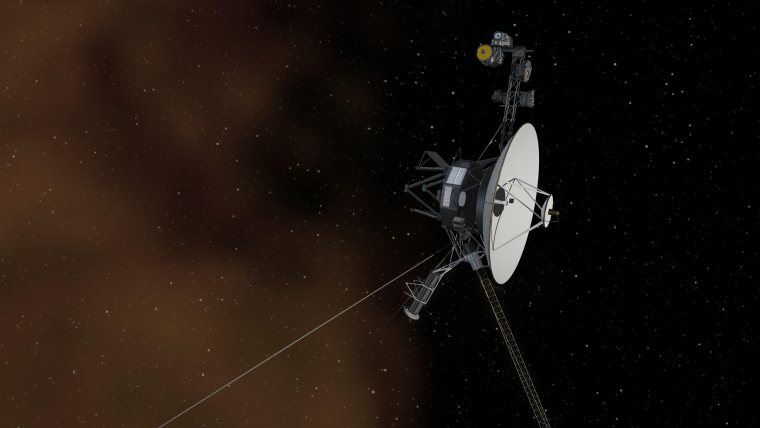

"The Voyager records are the farthest flung objects that humans have ever created," says Timothy Ferris, a veteran science and music journalist and the producer of the Golden Record. "And they're likely to be the longest lasting, at least in the 20th century."

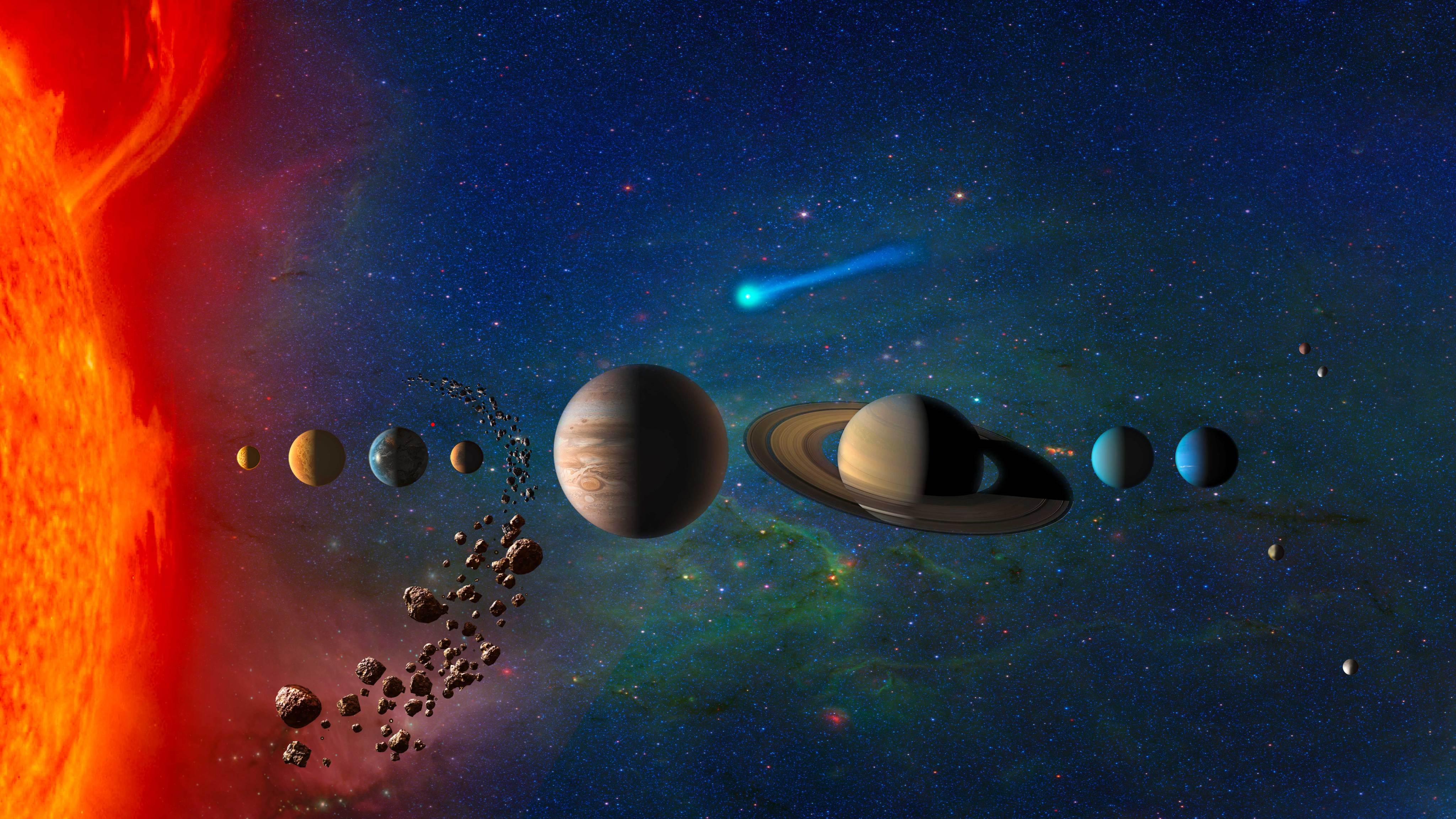

In the late 1970s, Ferris was recruited by his friend, astronomer Carl Sagan, to join a team of scientists, artists and engineers to help create two engraved golden records to accompany NASA's Voyager mission — which would eventually send a pair of human spacecraft beyond the outer rings of the solar system for the first time in history.

Carl Sagan And Ann Druyan's Ultimate Mix Tape

Ferris was tasked with the technical aspects of getting the various media onto the physical LP, and with helping to select the music. In addition to greetings in dozens of languages and messages from leading statesmen, the records also contained a sonic history of planet Earth and photographs encoded into the record's grooves. But mostly, it was music.

"We were gathering a representation of the music of the entire earth," Ferris says. "That's an incredible wealth of great stuff."

Ferris and his colleagues worked together to sift through Earth's enormous discography to decide which pieces of sound would best represent our planet. They really only had two criteria: "One was: Let's cast a wide net. Let's try to get music from all over the planet," he says. "And secondly: Let's make a good record."

That meant late nights of listening sessions while "almost physically drowning in records," Ferris says.

The final selection, which was engraved in copper and plated in gold, included opera, rock 'n' roll, blues, classical music and field recordings selected by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax .

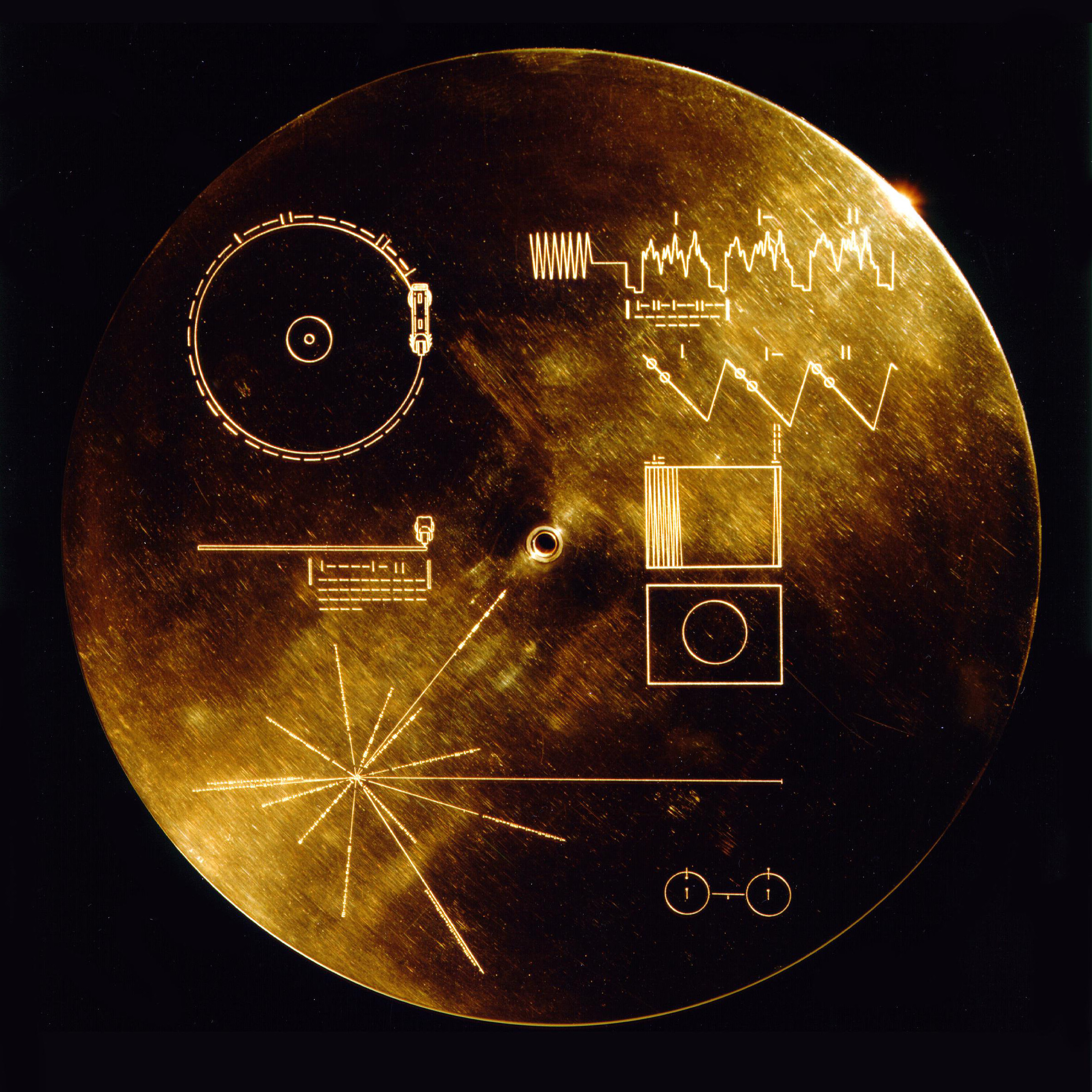

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record. NASA/Getty Images hide caption

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record.

Ferris says that from the very start, many people on the production team expected and hoped for the record to be commercially released soon after the launch of Voyager.

"Carl Sagan tried to interest labels in releasing Voyager," Ferris says. "It never worked."

Ferris says that's likely because the music rights were owned by several different record labels who were hesitant to share the bill. So — except for a limited CD-ROM release in the early 1990s — the record went largely unheard by the wider world.

David Pescovitz, an editor at technology news website Boing Boing and a research director at the nonprofit Institute for the Future, was seven years old when the Voyager spacecraft launched.

"When you're seven years old and you hear that a group of people created a phonograph record as a message for possible extraterrestrials and launched it on a grand tour of the solar system," says Pescovitz, "it sparks the imagination."

A couple years ago, Pescovitz and his friend Tim Daly, a record store manager at Amoeba Music in San Francisco, decided to collaborate on bringing the Golden Record to an earthbound audience.

Pescovitz approached his former graduate school professor — none other than Ferris, the Golden Record's original producer — about the project, and Ferris gave his blessing, with one important caveat.

Voyagers' Records Wait for Alien Ears

"You can't release a record without remastering it," says Ferris. "And you can't remaster without locating the master."

That turned out to be a taller order than expected. The original records were mastered in a CBS studio, which was later acquired by Sony — and the master tapes had descended into Sony's vaults.

Pescovitz enlisted the company's help in searching for the master tapes; in the meantime, he and Daly got to work acquiring the rights for the music and photographs that comprised the original. They also reached out to surviving musicians whose work had been featured on the record to update incomplete track information.

Finally, Pescovitz and Daly got word that one of Sony's archivists had found the master tapes.

Pescovitz remembers the moment he, Daly and Ferris traveled to Sony's Battery Studios in New York City to hear the tapes for the first time.

"They hit play, and the sounds of the Solomon Islands pan pipes and Bach and Chuck Berry and the blues washed over us," Pescovitz says. "It was a very moving and sublime experience."

Daly says that, in remastering the album, the team decided not to clean up the analog artifacts that had made their way onto the original master tapes, in order to preserve the record's authenticity down to its imperfections.

"We wanted it to be a true representation of what went up," Daly says.

Pescovitz and Daly teamed up with Lawrence Azerrad, a graphic designer who has made record packaging for the likes of Sting and Wilco , to design a luxuriant box set, complete with a coffee table book of photographs and, of course, tinted vinyl.

"I mean, if you do a golden record box set, you have to do it on gold vinyl," Daly says.

They put the project on Kickstarter and expected to sell it mostly to vinyl collectors, space nerds and audiophiles — but they underestimated the appeal.

"The internet was just on fire, talking about this thing," Daly says.

They blew past their initial funding goal in two days, eventually raising more than $1.3 million dollars, making it the most successful musical Kickstarter campaign ever. Among the initial 11,000 contributors were family members of NASA's original Voyager mission team.

An Alien View Of Earth

Last week, Ferris got his box set in the mail. He says that his friend, the late Carl Sagan, would be delighted by what they made.

"I think this record exceeds Carl's — not only his expectations, but probably his highest hopes for a release of the Voyager record," Ferris says. "I'm glad these folks were finally able to make it happen."

Pescovitz says he's just glad to have returned the Golden Record to the world that created it.

At a moment of political division and media oversaturation, Pescovitz and Daly say they hope that their Golden Record can offer a chance for people to slow down for a moment; to gather around the turntable and bask in the crackly sounds of what Sagan called the "pale blue dot" that we call home.

"As much as it was a gift from humanity to the cosmos, it was really a gift to humanity as well," Pescovitz says. "It's a reminder of what we can accomplish when we're at our best."

What Is on Voyager’s Golden Record?

From a whale song to a kiss, the time capsule sent into space in 1977 had some interesting contents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Voyager-records-631.jpg)

“I thought it was a brilliant idea from the beginning,” says Timothy Ferris. Produce a phonograph record containing the sounds and images of humankind and fling it out into the solar system.

By the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake already had some experience with sending messages out into space. They had created two gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were affixed to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft. Linda Salzman Sagan, an artist and Carl’s wife, etched an illustration onto them of a nude man and woman with an indication of the time and location of our civilization.

The “Golden Record” would be an upgrade to Pioneer’s plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and transmit much more information about life on Earth should extraterrestrials find it.

NASA approved the idea. So then it became a question of what should be on the record. What are humanity’s greatest hits? Curating the record’s contents was a gargantuan task, and one that fell to a team including the Sagans, Drake, author Ann Druyan, artist Jon Lomberg and Ferris, an esteemed science writer who was a friend of Sagan’s and a contributing editor to Rolling Stone .

The exercise, says Ferris, involved a considerable number of presuppositions about what aliens want to know about us and how they might interpret our selections. “I found myself increasingly playing the role of extraterrestrial,” recounts Lomberg in Murmurs of Earth , a 1978 book on the making of the record. When considering photographs to include, the panel was careful to try to eliminate those that could be misconstrued. Though war is a reality of human existence, images of it might send an aggressive message when the record was intended as a friendly gesture. The team veered from politics and religion in its efforts to be as inclusive as possible given a limited amount of space.

Over the course of ten months, a solid outline emerged. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. As producer of the record, Ferris was involved in each of its sections in some way. But his largest role was in selecting the musical tracks. “There are a thousand worthy pieces of music in the world for every one that is on the record,” says Ferris. I imagine the same could be said for the photographs and snippets of sounds.

The following is a selection of items on the record:

Silhouette of a Male and a Pregnant Female

The team felt it was important to convey information about human anatomy and culled diagrams from the 1978 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. To explain reproduction, NASA approved a drawing of the human sex organs and images chronicling conception to birth. Photographer Wayne F. Miller’s famous photograph of his son’s birth, featured in Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition, was used to depict childbirth. But as Lomberg notes in Murmurs of Earth , NASA vetoed a nude photograph of “a man and a pregnant woman quite unerotically holding hands.” The Golden Record experts and NASA struck a compromise that was less compromising— silhouettes of the two figures and the fetus positioned within the woman’s womb.

DNA Structure

At the risk of providing extraterrestrials, whose genetic material might well also be stored in DNA, with information they already knew, the experts mapped out DNA’s complex structure in a series of illustrations.

Demonstration of Eating, Licking and Drinking

When producers had trouble locating a specific image in picture libraries maintained by the National Geographic Society, the United Nations, NASA and Sports Illustrated , they composed their own. To show a mouth’s functions, for instance, they staged an odd but informative photograph of a woman licking an ice-cream cone, a man taking a bite out of a sandwich and a man drinking water cascading from a jug.

Olympic Sprinters

Images were selected for the record based not on aesthetics but on the amount of information they conveyed and the clarity with which they did so. It might seem strange, given the constraints on space, that a photograph of Olympic sprinters racing on a track made the cut. But the photograph shows various races of humans, the musculature of the human leg and a form of both competition and entertainment.

Photographs of huts, houses and cityscapes give an overview of the types of buildings seen on Earth. The Taj Mahal was chosen as an example of the more impressive architecture. The majestic mausoleum prevailed over cathedrals, Mayan pyramids and other structures in part because Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in honor of his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and not a god.

Golden Gate Bridge

Three-quarters of the record was devoted to music, so visual art was less of a priority. A couple of photographs by the legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams were selected, however, for the details captured within their frames. One, of the Golden Gate Bridge from nearby Baker Beach, was thought to clearly show how a suspension bridge connected two pieces of land separated by water. The hum of an automobile was included in the record’s sound montage, but the producers were not able to overlay the sounds and images.

A Page from a Book

An excerpt from a book would give extraterrestrials a glimpse of our written language, but deciding on a book and then a single page within that book was a massive task. For inspiration, Lomberg perused rare books, including a first-folio Shakespeare, an elaborate edition of Chaucer from the Renaissance and a centuries-old copy of Euclid’s Elements (on geometry), at the Cornell University Library. Ultimately, he took MIT astrophysicist Philip Morrison’s suggestion: a page from Sir Isaac Newton’s System of the World , where the means of launching an object into orbit is described for the very first time.

Greeting from Nick Sagan

To keep with the spirit of the project, says Ferris, the wordings of the 55 greetings were left up to the speakers of the languages. In Burmese , the message was a simple, “Are you well?” In Indonesian , it was, “Good night ladies and gentlemen. Goodbye and see you next time.” A woman speaking the Chinese dialect of Amoy uttered a welcoming, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” It is interesting to note that the final greeting, in English , came from then-6-year-old Nick Sagan, son of Carl and Linda Salzman Sagan. He said, “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

Whale Greeting

Biologist Roger Payne provided a whale song (“the most beautiful whale greeting,” he said, and “the one that should last forever”) captured with hydrophones off the coast of Bermuda in 1970. Thinking that perhaps the whale song might make more sense to aliens than to humans, Ferris wanted to include more than a slice and so mixed some of the song behind the greetings in different languages. “That strikes some people as hilarious, but from a bandwidth standpoint, it worked quite well,” says Ferris. “It doesn’t interfere with the greetings, and if you are interested in the whale song, you can extract it.”

Reportedly, the trickiest sound to record was a kiss . Some were too quiet, others too loud, and at least one was too disingenuous for the team’s liking. Music producer Jimmy Iovine kissed his arm. In the end, the kiss that landed on the record was actually one that Ferris planted on Ann Druyan’s cheek.

Druyan had the idea to record a person’s brain waves, so that should extraterrestrials millions of years into the future have the technology, they could decode the individual’s thoughts. She was the guinea pig. In an hour-long session hooked to an EEG at New York University Medical Center, Druyan meditated on a series of prepared thoughts. In Murmurs of Earth , she admits that “a couple of irrepressible facts of my own life” slipped in. She and Carl Sagan had gotten engaged just days before, so a love story may very well be documented in her neurological signs. Compressed into a minute-long segment, the brain waves sound, writes Druyan, like a “string of exploding firecrackers.”

Georgian Chorus—“Tchakrulo”

The team discovered a beautiful recording of “Tchakrulo” by Radio Moscow and wanted to include it, particularly since Georgians are often credited with introducing polyphony, or music with two or more independent melodies, to the Western world. But before the team members signed off on the tune, they had the lyrics translated. “It was an old song, and for all we knew could have celebrated bear-baiting,” wrote Ferris in Murmurs of Earth . Sandro Baratheli, a Georgian speaker from Queens, came to the rescue. The word “tchakrulo” can mean either “bound up” or “hard” and “tough,” and the song’s narrative is about a peasant protest against a landowner.

Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

According to Ferris, Carl Sagan had to warm up to the idea of including Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” on the record, but once he did, he defended it against others’ objections. Folklorist Alan Lomax was against it, arguing that rock music was adolescent. “And Carl’s brilliant response was, ‘There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,’” recalls Ferris.

On April 22, 1978, Saturday Night Live spoofed the Golden Record in a skit called “Next Week in Review.” Host Steve Martin played a psychic named Cocuwa, who predicted that Time magazine would reveal, on the following week’s cover, a four-word message from aliens. He held up a mock cover, which read, “Send More Chuck Berry.”

More than four decades later, Ferris has no regrets about what the team did or did not include on the record. “It means a lot to have had your hand in something that is going to last a billion years,” he says. “I recommend it to everybody. It is a healthy way of looking at the world.”

According to the writer, NASA approached him about producing another record but he declined. “I think we did a good job once, and it is better to let someone else take a shot,” he says.

So, what would you put on a record if one were being sent into space today?

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

The Temp Track

Four Scores and Several Thoughts Ago…

Reflections on Voyager and the Golden Record: America’s Greatest Achievement

By Michael W. Harris

The Voyager Golden Record seems to float into and out of my life and consciousness at the most random of times. Recently, I encountered it when I was finally reading a New York Times article by Chuck Klosterman from May about who will be the one rock and roller remembered when all of us are but “dust in the wind.”

Klosterman mentions Berry at the end of his article and frames it in the context of Berry’s inclusion on the Golden Record affixed to the Voyager probes now traversing the dark of interstellar space. Like Klosterman, I feel like there is no better distillation of what rock and roll is and was than Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.” Ask any former rock history student of mine and they can (hopefully) tell you that I share most of Klosterman’s reasons for his selection of Berry.

As a child who was both a musician and a space buff, I was always aware of the Golden Record as a thing, but it wasn’t until I started listening to Radiolab that I really started to think about what it represented. In a 2007 episode called “Space,” Radiolab talks to Ann Druyan, Carl Sagan’s widow and one of the leaders of the Voyager Interstellar Message Project, about the record and her love story with Sagan. The story was about not only the record, but also about how Ann and Carl met and fell in love while working on the project. Encountering this podcast fairly early in my PhD career—I think I started listening to Radiolab around 2009 or so—really started me thinking more seriously and philosophically about music’s place in our culture and history. And even more so about what the Golden Record represents.

The record contains more than just music, though. It is a sonic (and visual) portrait of Earth. It has music from all over the globe, greetings in over fifty languages, sounds of nature, and even photographs. And it also includes a recording of the brainwaves of Ann Druyan, right as she and Carl were falling in love.

But what is remarkable about the record is that while it was created by Americans for inclusion on an American probe built and launched by America’s national space agency, NASA, those involved on the project worked tirelessly to make sure that it was truly a representation of EARTH . You have the music and languages of two of America’s Cold War adversaries represented, Russia and China, along with music from a Native American tribe. There is a printed greeting by Jimmy Carter, then President of the United States, along with an audio greeting, in English, by then Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kurt Waldheim. It was an American project with a global focus.

What I find so wonderful and surprising about the Golden Record as assembled by Sagan and the others on the project, is the inclusivity of their thinking. They wanted it to be a record of the entire planet. It was an act of hope. It represented an aspirational desire that maybe we can one day be a unified planet that celebrates our diversity and truly draws strength from it, rather than uses it as a reason to tear down each other or otherwise exclude someone from a society. It was a desire that maybe by presenting that view of ourselves to the cosmos that we can one day live up to it.

This was a recurring theme in Sagan and Druyan’s work (especially Cosmos ), and it is why I consider Sagan among my “Holy Trinity” of modern writer-philosophers who have had the most influence on the development of my own thinking and worldview. For those who are wondering, the other two are Douglas Adams (of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy , because of his irreverent and humorous view of humanity, always keeping us humble) and Kurt Vonnegut (for his sharp, black comedy, which again puts humanity in our place).

Humility and humbleness before our fellow human is something that is severely lacking, and I am just as guilty of this as are many others. I have my own staunch opinions (I am a liberal progressive with shades of socialism and secular humanism), and I can sometimes be blinded by them when I engage with people I disagree with. But if we can all take a step back and see the long view of both human history and our future, hopefully we can begin to see that our differences don’t really amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. That we need to come together and create a society that is greater than all of our nation states put together which can help guide our world toward the future we need.

Perhaps the best distillation of these ideas comes, once again, from Carl Sagan and a photograph taken on 14 February 1990 by Voyager I as both it and the Golden Record flew past the orbit of Pluto. Known popularly as the Pale Blue Dot photograph , it is a photo that shows the Earth as a distant speck of light, a “mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam” as Sagan famously said, seen from over 6 billion kilometers away. It a powerful image that really puts our relatively small planet in perspective. Our population may have grown to over 7 billion people, of which 2.6 billion live in India and China alone, but we are still a small and insignificant planet in the vastness of the cosmos. As Douglas Adams put it: “Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of the Galaxy lies a small unregarded yellow sun. Orbiting this at a distance of roughly ninety-two million miles is an utterly insignificant little blue green planet whose ape-descended life forms are so amazingly primitive that they still think digital watches are a pretty neat idea.”

A similar photo was taken by the Cassini probe while in orbit of Saturn, though its distance was a meager 1.5 billion kilometers. However, the juxtaposition of Earth against Saturn’s ring has a certain beauty to it.

No nation is more special than the other. No person more valuable or more important than another. But collectively we are special…at least within our solar system. But when compared against the grand stage of the universe, we begin to see that we are but one small planet. And with that perspective, we have only two options, or views, before us: 1) we are alone and we are the only intelligent life to have arisen in the almost 14 billion year history of the universe, or 2) we are not alone and sometime—maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but hopefully soon—we will discover proof that there are more species out there to have developed intelligence and some form of communication. Either way, what we, as a species, have to do is still the same: come together and start working towards the common good of all people everywhere in the world. That might mean giving up some national sovereignty in order to work towards a common goal. It might mean an European Union style open border policy. It might even mean the creation of the dreaded, and favorite scare tactic of the conspiracy theory crowd, “one world government.”

But why is that such a crazy—and bad—idea? If we can peacefully and democratically unite all people for the common good of ourselves and our home— Spaceship Earth —then why shouldn’t we? It is only logical.

And maybe this weekend, as you are grilling meats, a practice older than our species (which means that it first developed in Africa), and exploding fireworks, first invented by the Chinese , pause and give a thought to how you, me, and the rest of us might take a longer view of humanity. Let you inner Carl Sagan out for a moment and reflect on the bigger picture of where we have been and where we are going. Reflect for just a minute on the Pale Blue Dot and the Golden Record, currently hurtling through interstellar space at nearly 40,000 mph carrying the message of Chuck Berry, Bach, Beethoven, Mangkunegara IV, Bo Ya, the Navajo, and many others, to who or whatever may find it one day in the future.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Featured: The Golden Record

A few weeks ago, an old Radiolab episode reminded me of the Golden Record, which I hadn't thought about since childhood.

In 1977, Voyager 1 and 2 headed out into the universe, each carrying a copy of a Golden Record. A combination of greetings, audio clips, and images made up the Record's contents. The Records and the spacecraft carrying them are expected to remain intact for billions of years, hopefully to be discovered by alien beings. They are time capsules and, when I learned of them at eight years old, I loved the concept of a time capsule. What would I put in one? What would future people say when they found it? Could I find someone else's message from the past?

These time capsules sparked my first realization that the past was inhabited by actual people who felt real feelings and had real experiences, but whose lives remain largely (and frustratingly) mysterious.

The greetings on the Record are disarmingly conversational. "Greetings from a computer programmer in the small university town of Ithaca on the planet Earth," it says in Swedish. "Hello? How are you?" in Japanese. Alongside images of human anatomy and mathematical statements are snapshots of mundane scenes, like this one of rush hour traffic in Thailand. Sounds range from whale song to train whistles, from the Brandenburg Concerto to Chuck Berry's Johnny Be Good . It's understandable given the intended audience, but as messages for posterity go, it's a far cry from Sima Qian's Shiji or Herodotus' History

Later in the podcast, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson reminds listeners of the enormous physical and chronological distances involved. The chance of any extraterrestrial being finding and playing the Golden Record is vanishingly small. And the likelihood that intelligent beings might hear it while human civilization still exists ? Essentially zero. The Record is not the opening line in an interstellar conversation. Instead, for the incredibly unlikely extraterrestrial who finds and interprets it, the Golden Record will almost certainly be the sole artifact of human history.

Ruminating anew on the Golden Record, I've been thinking about how - when I was teaching - I could have used it as a frame for historical thought and discussion. The concept is broad enough to encompass all of World History but its actual contents are manageably discrete. Perhaps most useful, the Committee that spent a year deciding on the content of the Record also published a book, Murmurs of Earth , explaining why they chose what they did. It's as if Qin Shi Huangdi himself wrote an annotated inventory of his tomb.

In other words, there is ample material to play with the connections between artifacts, authorial intent, and historical interpretation.

see resources

photo of record: NASA/JPL [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons (link is external)

photo of traffic: " Voyager Golden Record 102 rush hour traffic in Thailand (link is external) " by UN via Wikimedia Commons (link is external)

Background on the Golden Record from NASA

Radiolab podcast: Space

Carl Sagan explains the Golden Record

Sound recordings from the Golden Record

Images from the Golden Record

Murmurs from Earth

"What is on Voyager's Golden Record?" from Smithsonian Magazine

Presentation summaries from the 2009 ORIAS Summer Institute: Visible Power - Art in National Life

Questions for Discussion

What message do you believe the Voyager Interstellar Record Committee was trying to send about human civilization?

What similarities and differences do you see between the Golden Record and other intentionally long-lasting artifacts, like monumental buildings and stelae?

What message would you attempt to communicate about World History, if given the chance? Identify sounds and images you would include, and explain the reasoning behind your choices.

Lesson Ideas

Short Activity: Attempt to match images and sounds from the Golden Record to brief quotes about the committee's intent, from Murmurs of Earth

Jigsaw Project: (1) Assign small groups specific regions or time periods; have them identify an intended message and 15 artifacts to include on a Golden Record. (2) Remix students in a jigsaw format; have them negotiate a new intended message and 25 total artifacts.

- Lesson Plans topic page

Nov 20, 2007

Imagine trying to sum up existence on Earth into one little record... for an alien or humans of the far-off future. What sounds would you use? What music? What images? We put this charge to a bunch of artists, and asked what they would put into a space capsule. And in this week's podcast, a few of the answers we got back. From Margaret Cho, Philip Glass, Alice Waters, Michael Cunningham, and Neil Gaiman.

Unlock member-only exclusives and support the show

Exclusive podcast extras, entire podcast archive, listen ad-free, behind-the-scenes content, video extras, original music & playlists, unlock exclusives in the lab, sign up for the newsletter.

Test the outer edges of what you think you know

Produced by WNYC Studios

© 2024 WNYC Studios

Golden Record Sounds and Music

Sounds of earth.

The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft.

Music from Earth

The following music was included on the Voyager record.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Our Solar System

Inside NASA's 5-month fight to save the Voyager 1 mission in interstellar space

After working for five months to re-establish communication with the farthest-flung human-made object in existence, NASA announced this week that the Voyager 1 probe had finally phoned home.

For the engineers and scientists who work on NASA’s longest-operating mission in space, it was a moment of joy and intense relief.

“That Saturday morning, we all came in, we’re sitting around boxes of doughnuts and waiting for the data to come back from Voyager,” said Linda Spilker, the project scientist for the Voyager 1 mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We knew exactly what time it was going to happen, and it got really quiet and everybody just sat there and they’re looking at the screen.”

When at long last the spacecraft returned the agency’s call, Spilker said the room erupted in celebration.

“There were cheers, people raising their hands,” she said. “And a sense of relief, too — that OK, after all this hard work and going from barely being able to have a signal coming from Voyager to being in communication again, that was a tremendous relief and a great feeling.”

The problem with Voyager 1 was first detected in November . At the time, NASA said it was still in contact with the spacecraft and could see that it was receiving signals from Earth. But what was being relayed back to mission controllers — including science data and information about the health of the probe and its various systems — was garbled and unreadable.

That kicked off a monthslong push to identify what had gone wrong and try to save the Voyager 1 mission.

Spilker said she and her colleagues stayed hopeful and optimistic, but the team faced enormous challenges. For one, engineers were trying to troubleshoot a spacecraft traveling in interstellar space , more than 15 billion miles away — the ultimate long-distance call.

“With Voyager 1, it takes 22 1/2 hours to get the signal up and 22 1/2 hours to get the signal back, so we’d get the commands ready, send them up, and then like two days later, you’d get the answer if it had worked or not,” Spilker said.

The team eventually determined that the issue stemmed from one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers. Spilker said a hardware failure, perhaps as a result of age or because it was hit by radiation, likely messed up a small section of code in the memory of the computer. The glitch meant Voyager 1 was unable to send coherent updates about its health and science observations.

NASA engineers determined that they would not be able to repair the chip where the mangled software is stored. And the bad code was also too large for Voyager 1's computer to store both it and any newly uploaded instructions. Because the technology aboard Voyager 1 dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, the computer’s memory pales in comparison to any modern smartphone. Spilker said it’s roughly equivalent to the amount of memory in an electronic car key.

The team found a workaround, however: They could divide up the code into smaller parts and store them in different areas of the computer’s memory. Then, they could reprogram the section that needed fixing while ensuring that the entire system still worked cohesively.

That was a feat, because the longevity of the Voyager mission means there are no working test beds or simulators here on Earth to test the new bits of code before they are sent to the spacecraft.

“There were three different people looking through line by line of the patch of the code we were going to send up, looking for anything that they had missed,” Spilker said. “And so it was sort of an eyes-only check of the software that we sent up.”

The hard work paid off.

NASA reported the happy development Monday, writing in a post on X : “Sounding a little more like yourself, #Voyager1.” The spacecraft’s own social media account responded , saying, “Hi, it’s me.”

So far, the team has determined that Voyager 1 is healthy and operating normally. Spilker said the probe’s scientific instruments are on and appear to be working, but it will take some time for Voyager 1 to resume sending back science data.

Voyager 1 and its twin, the Voyager 2 probe, each launched in 1977 on missions to study the outer solar system. As it sped through the cosmos, Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn, studying the planets’ moons up close and snapping images along the way.

Voyager 2, which is 12.6 billion miles away, had close encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune and continues to operate as normal.

In 2012, Voyager 1 ventured beyond the solar system , becoming the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, or the space between stars. Voyager 2 followed suit in 2018.

Spilker, who first began working on the Voyager missions when she graduated college in 1977, said the missions could last into the 2030s. Eventually, though, the probes will run out of power or their components will simply be too old to continue operating.

Spilker said it will be tough to finally close out the missions someday, but Voyager 1 and 2 will live on as “our silent ambassadors.”

Both probes carry time capsules with them — messages on gold-plated copper disks that are collectively known as The Golden Record . The disks contain images and sounds that represent life on Earth and humanity’s culture, including snippets of music, animal sounds, laughter and recorded greetings in different languages. The idea is for the probes to carry the messages until they are possibly found by spacefarers in the distant future.

“Maybe in 40,000 years or so, they will be getting relatively close to another star,” Spilker said, “and they could be found at that point.”

Denise Chow is a reporter for NBC News Science focused on general science and climate change.

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

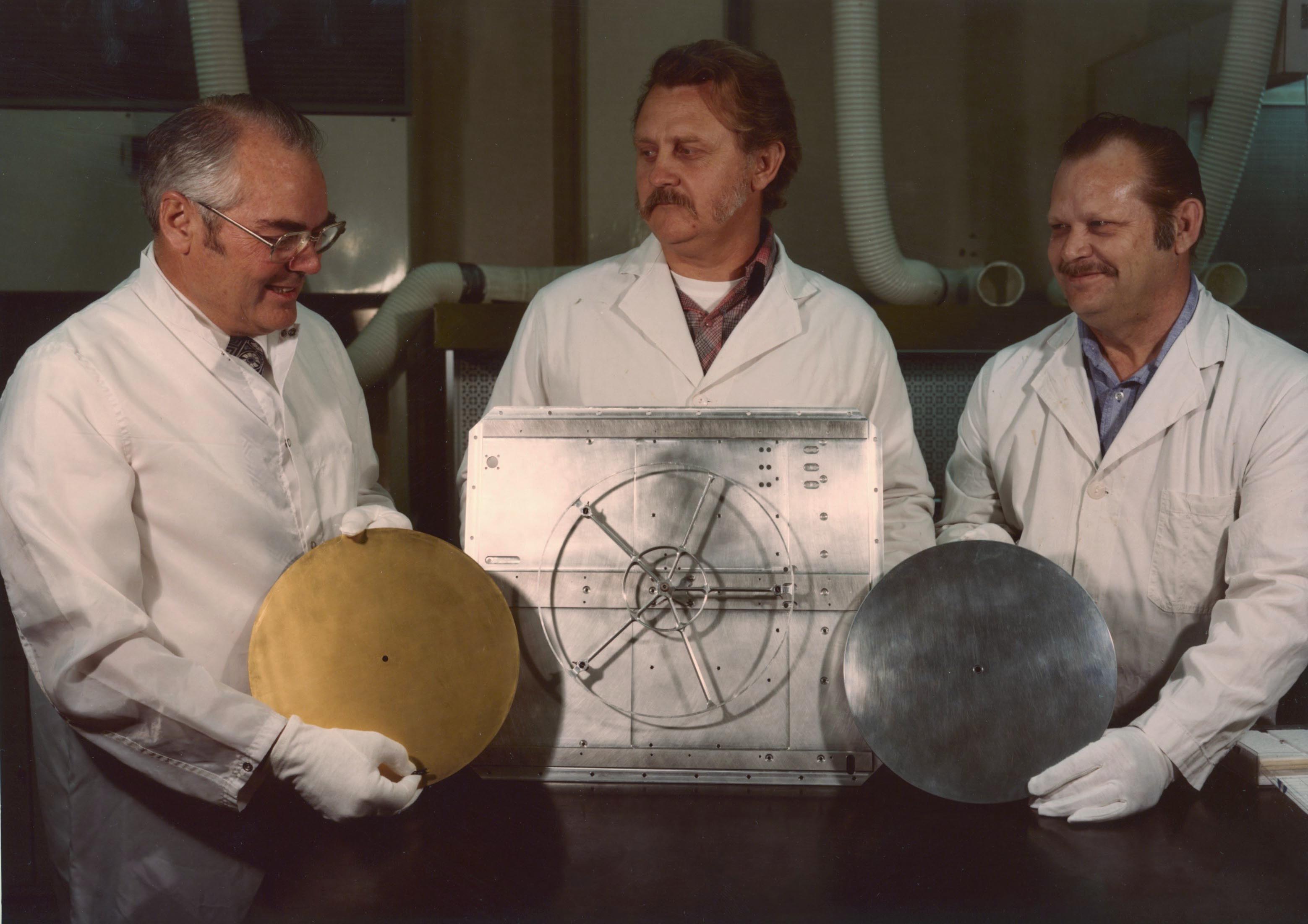

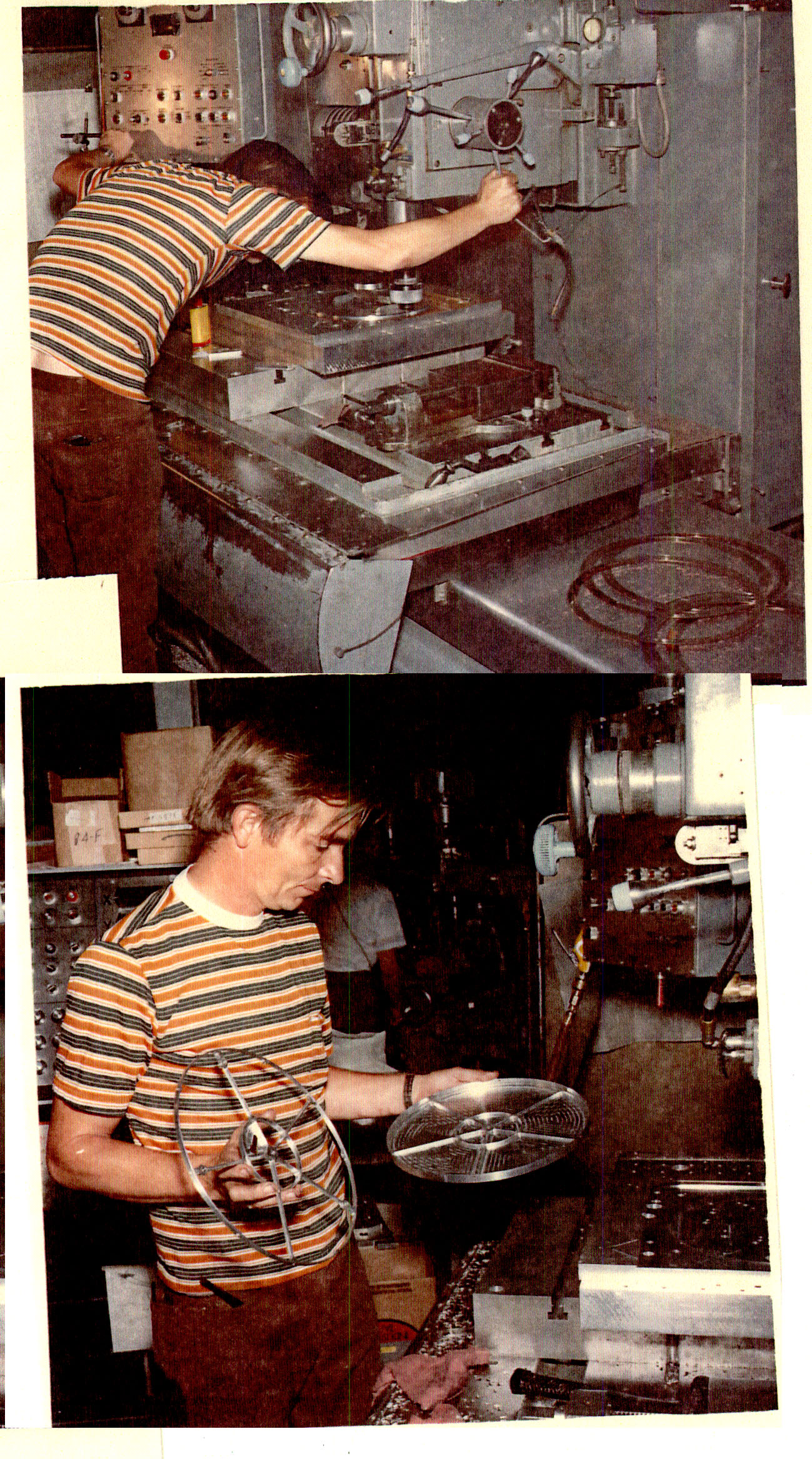

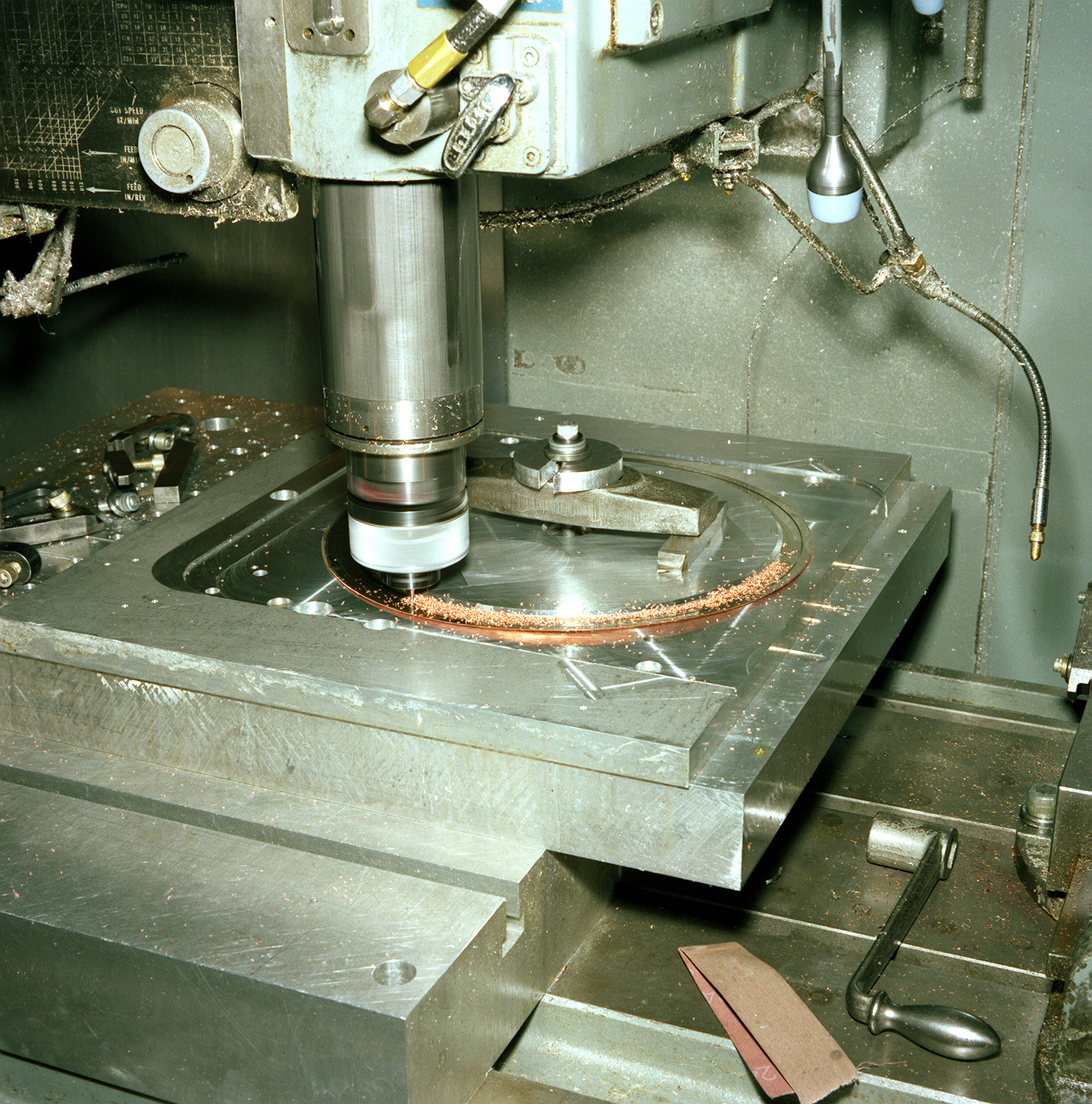

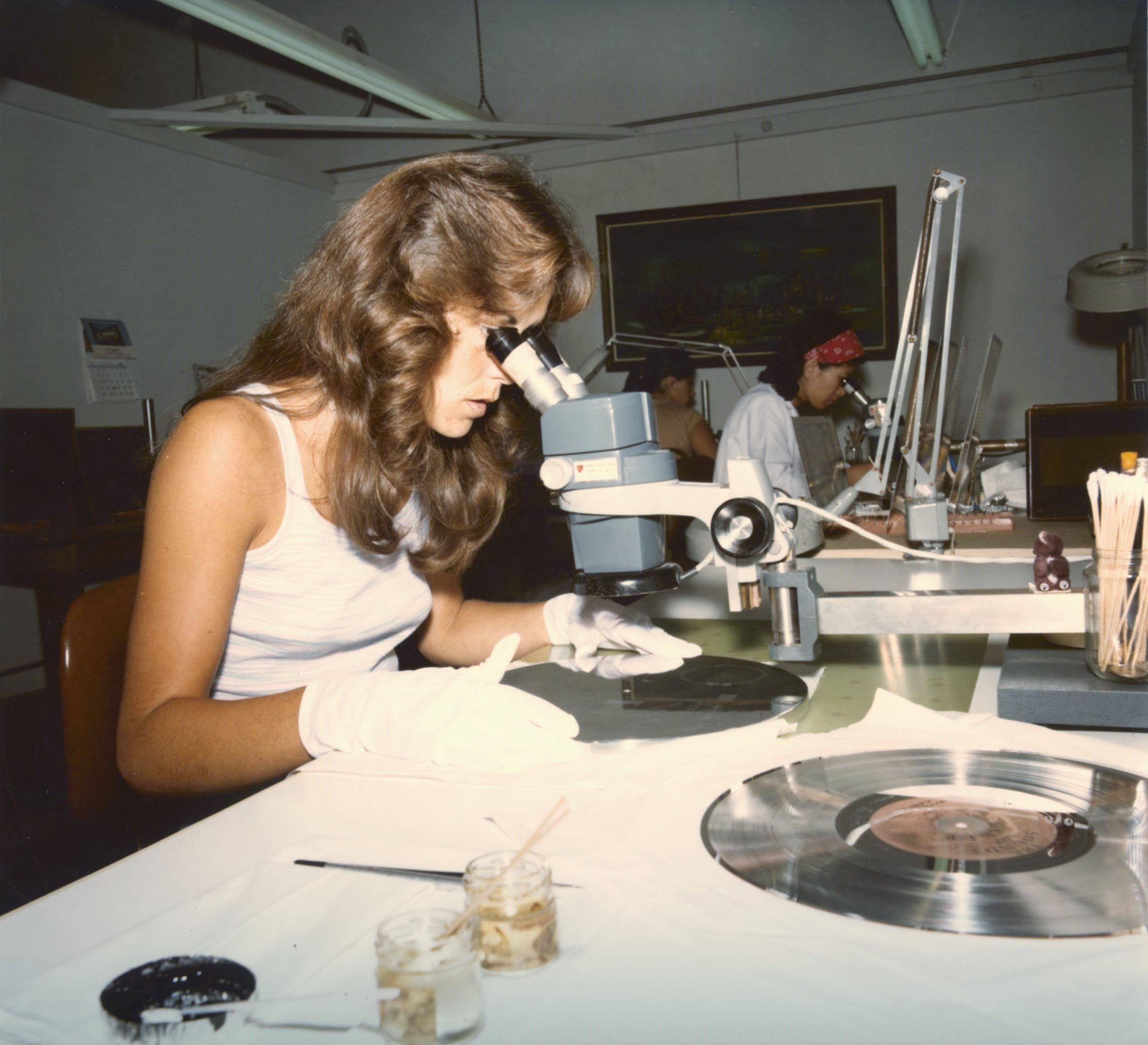

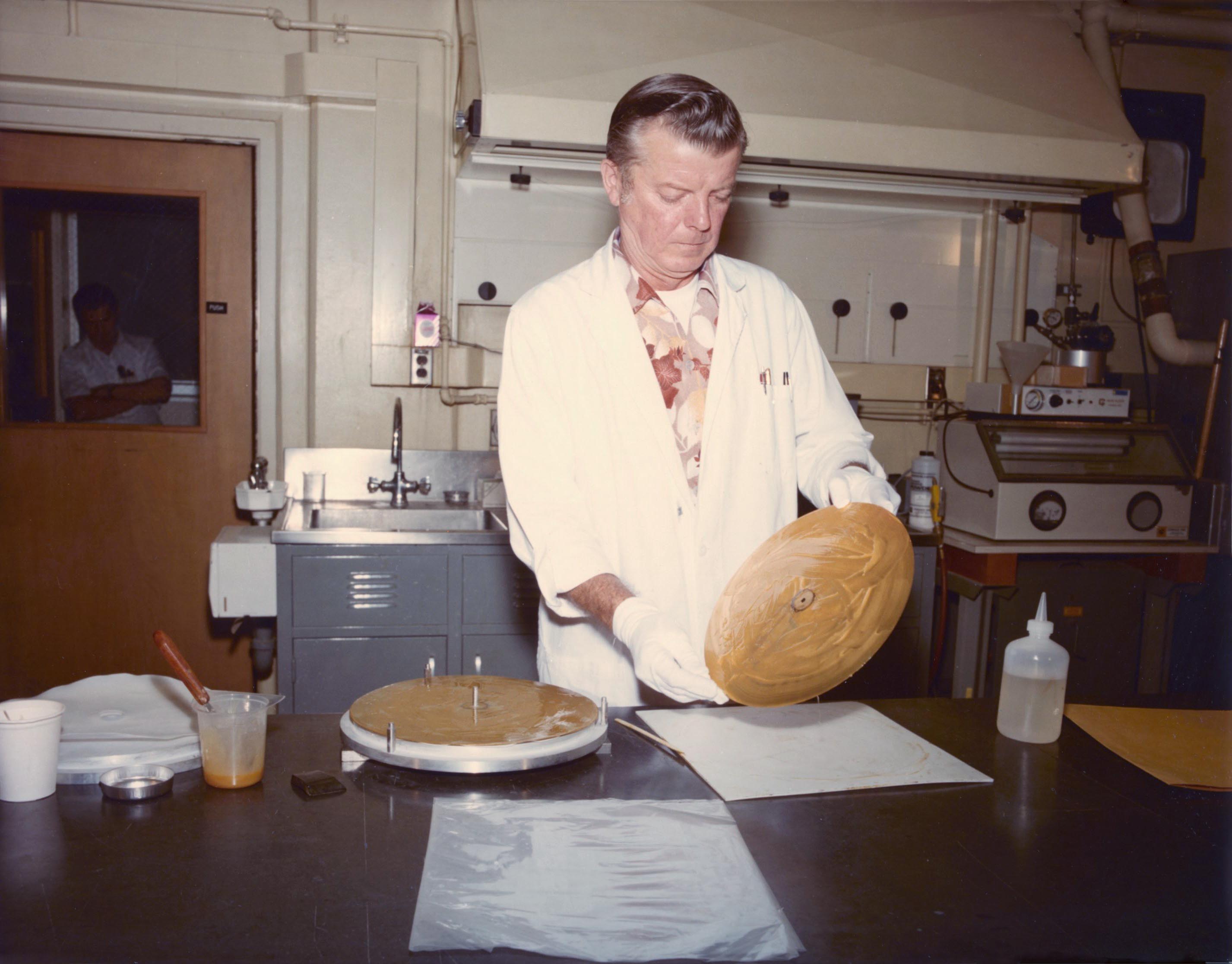

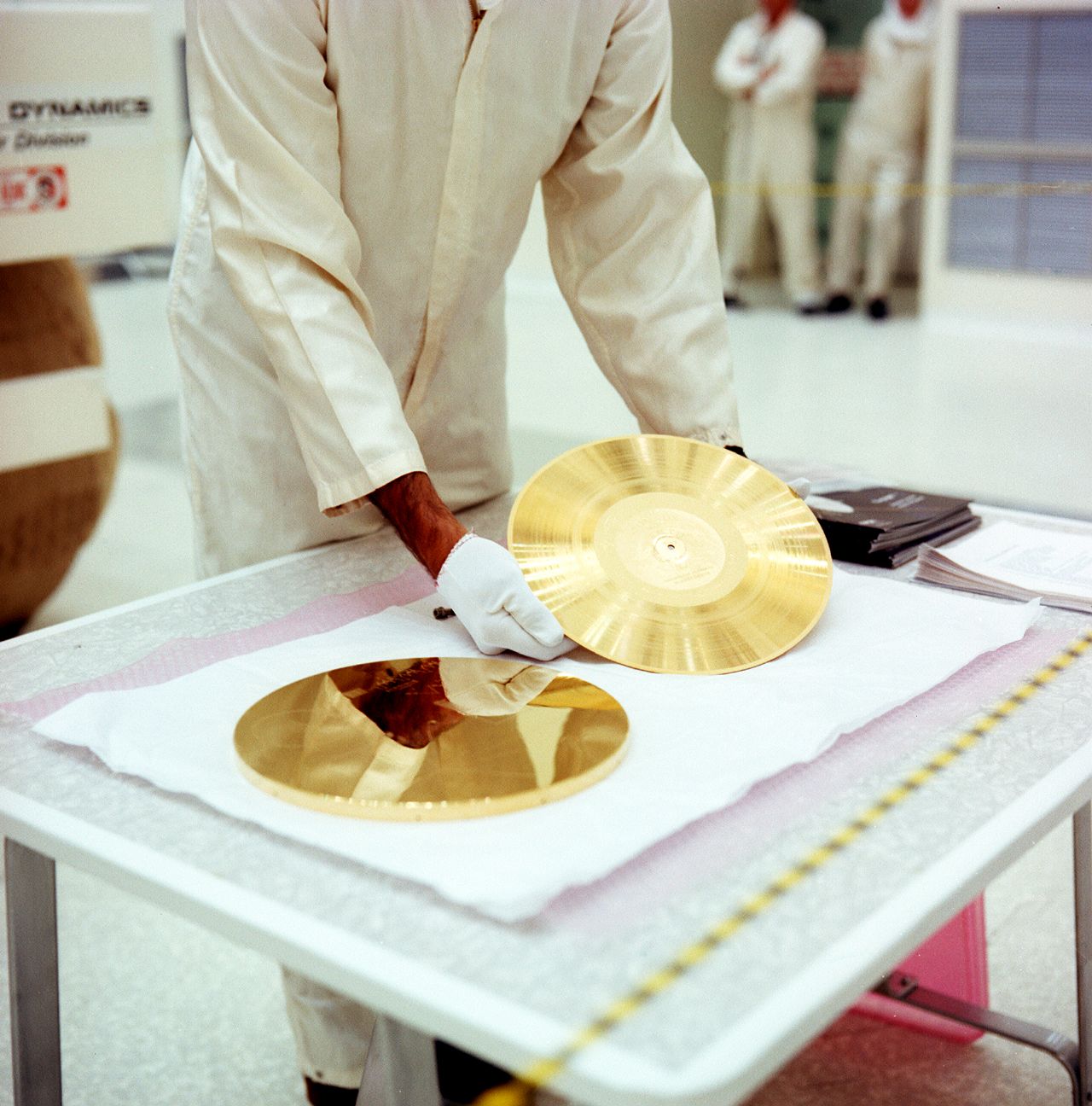

Making of the Golden Record

Many people were instrumental in the design, development and manufacturing of the golden record. Blank records were provided by the Pyral S.A. of Creteil, France. CBS Records contracted the JVC Cutting Center in Boulder, Colorado to cut the lacquer masters which were then sent to the James G. Lee Record Processing center in Gardena, California to cut and gold plate eight Voyager records. Gold plating took place on August 23, 1977; afterward, the records were mounted in aluminum containers and delivered to JPL. The record is constructed of gold-plated copper and is 12 inches (30 cm) in diameter. The record's cover is aluminum and electroplated upon it is an ultra-pure sample of the isotope uranium-238. Uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.468 billion years. The records also had the inscription "To the makers of music – all worlds, all times" hand-etched on its surface.

Voyager Golden Record Cover

Voyager Golden Record

Voyager Phonograph Record, 5-10-1977

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Voyager Recording Session, 6-29-77

Voyager Golden Record, production machine, 6-30-77

Voyager Golden Record production; record machine fixture, 6-30-77

Voyager Golden Record, project plastic lab, 7-21-77

Voyager Golden Record, etching, 7-28-77

John Casani, August 4, 1977

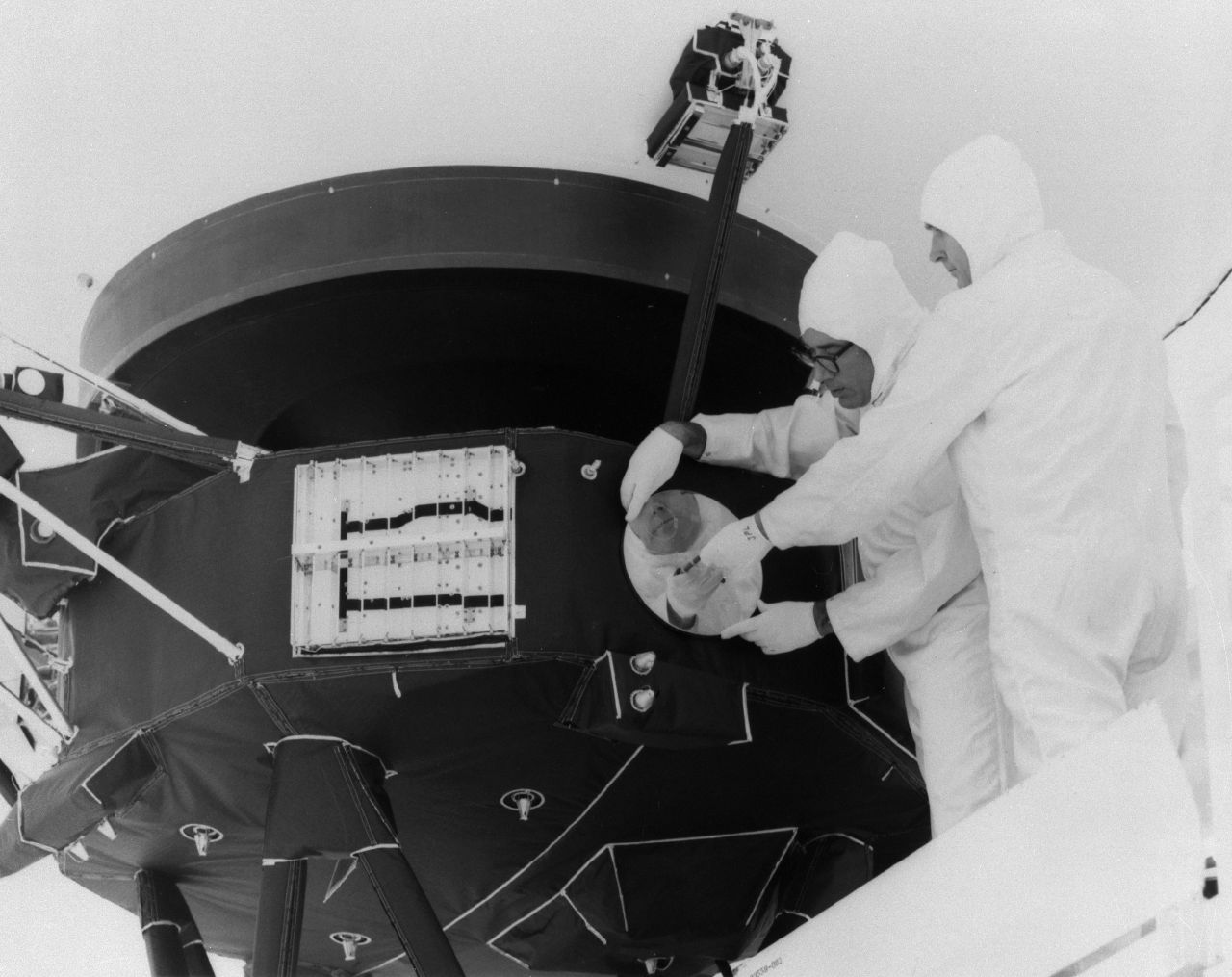

As NASA’s two Voyager spacecraft travel out into deep space, they carry a small American flag and a Golden Record packed with pictures and sounds -- mementos of our home planet. This picture shows John Casani, Voyager project manager in 1977, holding a small Dacron flag that was folded and sewed into the thermal blankets of the Voyager spacecraft before they launched 36 years ago. Below him lie the Golden Record (left) and its cover (right). In the background stands Voyager 2 before it headed to the launch pad. The picture was taken at Cape Canaveral, Florida, on August 4, 1977.

Voyager Golden Record, gold plating, 8-23-77

Voyager Golden Record, lamination bonding, 8-31-1977

The Golden Record

Mounting the Golden Record

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In the Space episode Ann Druyan, widow of Carl Sagan, told us a story about the Voyager expedition, true love, and golden record that travels through space. Listen to part of the episode at the top of the page. Here's what Ann Druyan thought of it! (She's speaking with intern Linda Evarts):

(You can hear the entire Golden Record here.) While the Voyager probes aren't expected to reach another planetary system for roughly 40,000 years, we recently stumbled across evidence that the Golden Record has indeed been intercepted by intelligent beings--check out this reworking: Scrambles of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record, Remixed ...

Radiolab: Carl Sagan And Ann Druyan's Ultimate Mix Tape Of The Human Experience Floating through space right now is a golden record carrying sounds of Earth: a mother's first words to her baby ...

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears. ... Radiolab Carl Sagan And Ann Druyan's Ultimate Mix Tape.

The remainder of the record is in audio, designed to be played at 16-2/3 revolutions per minute. It contains the spoken greetings, beginning with Akkadian, which was spoken in Sumer about six thousand years ago, and ending with Wu, a modern Chinese dialect.Following the section on the sounds of Earth, there is an eclectic 90-minute selection of music, including both Eastern and Western ...

A Kind of Time Capsule. Pioneers 10 and 11, which preceded Voyager, both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. With this example before them, NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule ...

The "Golden Record" would be an upgrade to Pioneer's plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and ...

The Golden Record. Pioneers 10 and 11, which preceded Voyager, both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. With this example before them, NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule ...

The Voyager Golden Record contains 116 images and a variety of sounds. The items for the record, which is carried on both the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft, were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University.Included are natural sounds (including some made by animals), musical selections from different cultures and eras, spoken greetings in 59 languages ...

A mission that was supposed to last just five years is celebrating its 30th anniversary this fall. Scientists continue to receive data from the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft as they approach interstellar space. The twin craft have become a fixture of pop culture, inspiring novels and playing a central role in television shows, music videos, songs ...

Images on the Golden Record. The following is a listing of pictures electronically placed on the phonograph records which are carried onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University, et. al. Dr. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and ...

The Voyager Golden Records are two identical phonograph records which were included aboard the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended for any intelligent extraterrestrial life form who may find them.

Celebrate the 35th anniversary of the launch of Voyager 2 (it rocketed off Earth on 8/20/77 carrying a copy of the Golden Record), and tip your hat to the Mars rover Curiosity as it kicks off its third week on the red planet, with a rebroadcast of one our favorite episodes: Space. We've been space-crazy the past few weeks here at Radiolab -- from cheering on the scientifically epic landing of ...

The Voyager Golden Record seems to float into and out of my life and consciousness at the most random of times. ... In a 2007 episode called "Space," Radiolab talks to Ann Druyan, Carl Sagan's widow and one of the leaders of the Voyager Interstellar Message Project, about the record and her love story with Sagan. The story was about not ...

The Voyager spacecraft showcasing where the Golden Record is mounted. Credit: NASA/JPL. The drawing in the lower left-hand corner of the cover is the pulsar map previously sent as part of the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11. It shows the location of the solar system with respect to 14 pulsars, whose precise periods are given.

In the Radiolab podcast Space episode (2004) Ann Druyan mentioned that the contents of the Voyager Golden Record will last for 1 billion years before the contents of the Record becomes unreadable. This raises some questions: How will the Golden Record outlast everything mankind has created? What are the special features of the Record to reduce its deterioration?

Featured: The Golden Record. January 4, 2016. A few weeks ago, an old Radiolab episode reminded me of the Golden Record, which I hadn't thought about since childhood. In 1977, Voyager 1 and 2 headed out into the universe, each carrying a copy of a Golden Record. A combination of greetings, audio clips, and images made up the Record's contents.

In 1977, the Voyager spacecraft launched into space. And with it, went the Golden Record-- a sort of time capsule, a collection of so... How would you describe life on Earth to an alien? In 1977, the Voyager spacecraft launched into space. And with it, went the Golden Record-- a sort of time capsule, a collection of so...

Sounds of Earth The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. Music from Earth The following music was included on the Voyager record. Country of origin Composition Artist(s) Length Germany Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F. First Movement Munich Bach Orchestra, Karl Richter, conductor 4:40 Java […]

Images on the Golden Record. The following is a listing of pictures electronically placed on the phonograph records which are carried onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University, et. al. Dr. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and ...

Embark on an extraordinary journey to decipher the Voyager Golden Record, a cosmic time capsule carrying a message from humanity to extraterrestrial beings. ...

Inside NASA's 5-month fight to save the Voyager 1 mission in interstellar space. The Voyager 1 probe is the most distant human-made object in existence. After a major effort to restore ...

Gold plating took place on August 23, 1977; afterward, the records were mounted in aluminum containers and delivered to JPL. The record is constructed of gold-plated copper and is 12 inches (30 cm) in diameter. The record's cover is aluminum and electroplated upon it is an ultra-pure sample of the isotope uranium-238.