Advertisement

Did the Chinese beat Columbus to America?

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

In his bestselling book, "1421: The Year China Discovered America," British amateur historian Gavin Menzies turns the story of the Europeans' discovery of America on its ear with a startling idea: Chinese sailors beat Christopher Columbus to the Americas by more than 70 years. The book has generated controversy within the halls of scholarship. Anthropologists, archaeologists, historians and linguists alike have debunked much of the evidence that Menzies used to support his notion, which has come to be called the 1421 theory .

But where did Menzies come up with the idea that it was Asians, not Europeans, who first arrived in America from other countries? It's been long held by scholars that it was people from Asia who first set foot in North America, but not in the way that Menzies describes. Sometime 10,000 years ago or more, people of Asian origination are believed to have crossed over the Bering land bridge from Siberia to what is now Alaska. From there, they are believed to have spread out over the course of millennia, diverging genetically and populating North and South America.

But Menzies' 1421 theory supposes much more direct influence from China. Rather than civilization evolving separately in the Americas and Asia, under the 1421 theory, China was directly involved in governance and trade with the peoples of the Americas with whom they shared their ancestry.

So what evidence does he have to support this notion? It's Menzie's belief that one merely has to refer to certain maps to see the light.

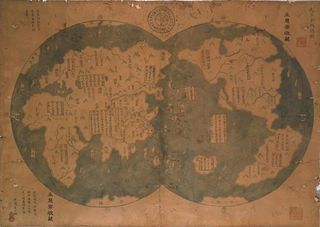

A full 30 years before Gavin Menzies published his book, Baptist missionary Dr. Hendon M. Harris perused the curiosities in a shop in Taiwan. It was there he made an amazing discovery: a map that looked to be ancient, written in classical Chinese and depicting what to Harris was clearly North America. It was a map of Fu Sang , the legendary land of Chinese fable.

Fu Sang is to the Chinese what Atlantis is to the West -- a mythical land that most don't believe existed, but for which enough tantalizing (yet vague) evidence exists to maintain popularity for the idea. The map the missionary discovered -- which has come to be known as the Harris map -- showed that Fu Sang was located exactly where North America is. Even more amazingly, some of the features shown on the map of Fu Sang look a lot like geographical anomalies unique to North America, such as the Grand Canyon.

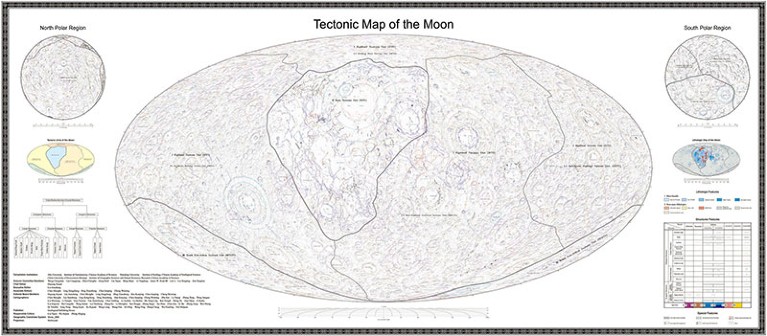

As if the Harris map weren't suggestive enough, other maps have also surfaced. It's a specific map that Menzies points to as definitive proof that the Chinese had already explored the world long before the Europeans ever set sail in the age of exploration. This map, known as the 1418 map -- so called for the date it was supposedly published -- clearly shows all of the world's oceans, as well as all seven continents, correct in shape and situation. Even more startling is the map's accurate depiction of features of North America, including the Potomac River in the Northeast of the present-day United States.

Menzies believes that not only had the Chinese already explored the world before Columbus and other European explorers, but that it was with Chinese maps that the Europeans were able to circumnavigate the globe. Armed with the map as his flagship evidence, Menzies points out plenty of other artifacts that point to Chinese pre-Columbian occupation in the Americas. Read the next page to find out what supports his theory.

Physical Evidence for the 1421 Theory

The 1421 theory: junk history, the 1418 map of america.

During the Ming Dynasty, a great admiral named Zhang He (as well as other notable admirals) sailed out of China to explore the world. Under the behest of Emperor Zhu Di, He and the Chinese Fleet (made up of 28,000 men) made their way from Asia to the Middle East and Africa, eventually reaching as far as Indonesia. But did the fleet continue west all the way to the Americas?

Perhaps the more logical possibility is that the fleet returned to China and then again set sail, this time eastward, across the Pacific to the west coast of North America. Either way, Menzies says that evidence of their arrival is scattered throughout the tradition, custom and art of American Indian tribes. And he's not alone. "1421" has created a stir among its readership, generating scores of additional submissions of evidence of a Chinese presence within the Americas before the Europeans set foot on the continents. To Menzies and his supportive readers, one need merely look at the rich cultural tapestry of the peoples of the Americas to find what they believe is the evidence of Chinese influence there.

Before the arrival of Europeans, neither North nor South America had a horse roaming upon it. This is the idea held by historians -- the horse is not indigenous to the Americas, and it wasn't until the Europeans brought the horse that the species found its way to the new world. But this is contradicted by some pre-Columbian native art found at Cofins Cave in Brazil and at Trujillo, Peru that depict horses, and in one case, what is thought to be Chinese cavalry on horseback. The Chinese were experienced horsemen for centuries, if not millennia, prior to the European age of exploration, and it's logical that were they to make an expedition to the Americas, they would have brought their valuable horses with them.

Indigenous legend and folklore is also fraught with what Menzies believes are stories about encounters between native tribes and Chinese explorers. The leaders of the Inca tribe -- a vast, powerful mountain tribe in the Andes Mountains of South America -- are thought by Menzies to have been governed by Chinese admirals. The leader Montezuma , ruler of the Aztec empire in Mexico, is believed by Menzies to have mistaken the conquistador Cortez for his grandfather, returned again from his home in the East. The Cherokee Indians of the southeastern United States possess lore that tells of their accepting and warring with visiting Chinese travelers by sea.

But what of physical evidence? If the Chinese had landed in the Americas -- let alone traded with and governed the people they found there, wouldn't direct evidence of their presence remain? Menzies and the proponents of the 1421 theory say it does exist. In the Pacific Northwest of the present-day United States, investigations at eight different sites have uncovered Chinese coins. A garment from the Nez Perce tribe of present-day Idaho that's dated at over 300 years old has woven ornaments into it that are believed to be Chinese beads. And in the Florida Keys and off the coast of Big Sur, Calif., artifacts of pre-Columbian Chinese jade have been unearthed from a riverbed and the sea floor.

But despite all of this evidence (and even more), historians aren't rushing to rewrite the history books. Find out why some consider Menzies' 1421 theory to be questionable.

From its introduction in 2003, Gavin Menzies' 1421 theory has come under assault. The writing that seeks to disprove Menzies is at least as long as his book. One question perhaps looms largest when approaching the 1421 theory: If the Chinese had a presence in the Americas prior to Christopher Columbus, then why isn't their mark left indelibly on the face of American civilization?

The Norse, who sailed as far west as Newfoundland in their travels across the Atlantic, left remnants of their visits to North America. Their folklore includes accounts of the Vikings' encounters with Native Americans. The crumbling remains of the stone outposts they built during their stay can still be seen. This was 1,000 years ago, and 500 years before Columbus' voyage. Yet the Vikings brief settlement in North America is still evident. If the Chinese had such a thorough impact on societies in the Americas just 70 years before Columbus' arrival, then why isn't evidence of their presence everywhere?

What's more, there's a distinct lack of cross-cultural pollination between the new world and China. When the Europeans arrived in the Americas, they brought with them things that have never before been seen in the continents, like steel and horses. But more importantly, they took back exotic treasures from the new world. Maize and tomatoes, along with vast amounts of plundered gold, found its way to Europe upon the ships of returning explorers. Where's the Incan gold or the corn of the Aztecs in China?

Perhaps the evidence that's been most attacked is the 1408 map itself. Dr. Geoff Wade, a historian with the National University of Singapore, has written extensively in an effort to debunk Gavin Menzies and the 1421 theory, even going so far as filing a complaint in the United Kingdom against the publishers of Menzies' book for marketing it as a history.

Wade points out several flaws with the 1408 map which suggest it's a fake, chief among them is that the map shows the world based on the idea that it's a sphere. This notion was unknown in Ming Dynasty China. He also points out that China is poorly represented on the map, and wonders why, if the map's creators were Chinese, their nation would be drawn clumsily.

It's Wade's belief that the 1408 map was created within the 21st century, possibly even to support Menzie's 1421 theory. Wade believes that the map is based on old maps created by Jesuit missionaries in the 17th century. He points out that California is shown as an island and China is located at the center of the map, both examples of Jesuit cartography. He also says that some of the text has clearly been translated into Chinese from old Jesuit maps.

If the map is fake, then the entire 1421 theory falls apart. But isn't there any easier way to determine if the Chinese ever sailed to the Americas? Why not just ask? Here's where the story takes a turn that may maintain the 1421 theory's status as debatable for years to come. After the invading Manchu rulers took over China following the Ming Dynasty (establishing the Qing Dynasty ), the foreigners took great pains to wipe out any reminders of the previous rule. This included destroying all accounts of the great fleet's extensive voyages. As these documents burned, any evidence, contradictory or supportive, of a Chinese presence in the Americas was lost forever.

For more information on maps, as well as links to Menzies' and Wades' discourse, visit the next pages.

Lots More Information

Related howstuffworks articles.

- How Maps Work

- How Beijing Works

- How DNA Works

- How DNA Evidence Works

- Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine

- Christopher Columbus

- History of China

- History of Spain

- History of Asia

- American Indians

- History of Sweden

More Great Links

- Zhang He's Integrated Map (The 1418 Map)

- The Wade Challenge

- 1421 Official Site

- "Junk History." 4 Corners/Australian Braodcasting Corporation. July 31, 2006. http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/content/2006/s1699373.htm

- Lovgren, Stefan. "Frist Americans Arrived Recently, Settled Pacific Coast, DNA Study Says." National Geographic. February 2, 2007. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2007/02/070202-human-migration.html

- Menzies, Gavin. "1421: The Year China Discovered the World." http://www.1421.tv/index.asp

- Poser, Bill. "Language Log." February 1, 2004. University of Pennsylvania. http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/000409.html

- Seaver, Kristen A. "Walrus Pitch and Other Novelties: Gavin Menzies and the Far North." The 1421 Myth Exposed. http://www.1421exposed.com/html/walrus_pitch.html

- Wade, Dr. Geoff. "Liu Gang's Statement on the Purported 1418 Map." The 1421 Myth Exposed. http://www.1421exposed.com/html/wade_challenge.html

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -43% $13.19 $ 13 . 19 FREE delivery Thursday, May 9 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $7.65 $ 7 . 65 FREE delivery Friday, May 10 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Zoom Books Company

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

1421: The Year China Discovered America Paperback – June 3, 2008

Purchase options and add-ons.

On March 8, 1421, the largest fleet the world had ever seen set sail from China to "proceed all the way to the ends of the earth to collect tribute from the barbarians beyond the seas." When the fleet returned home in October 1423, the emperor had fallen, leaving China in political and economic chaos. The great ships were left to rot at their moorings and the records of their journeys were destroyed. Lost in the long, self-imposed isolation that followed was the knowledge that Chinese ships had reached America seventy years before Columbus and had circumnavigated the globe a century before Magellan. And they colonized America before the Europeans, transplanting the principal economic crops that have since fed and clothed the world.

- Print length 650 pages

- Language English

- Publisher William Morrow Paperbacks

- Publication date June 3, 2008

- Dimensions 6 x 1.34 x 9 inches

- ISBN-10 0061564893

- ISBN-13 978-0061564895

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

“Menzies’ enthusiasm is infectious and his energy boundless. He has raised important questions and marshaled some fascinating information.” — Toronto Globe and Mail

“Captivating . . . a historical detective story . . . that adds to our knowledge of the world, past and present.” — Daily News

“ is likely to be the most fascinating read of 2003.” — UPI

“No matter what you think of Menzies’s theories, his enthusiasm is infectious.” — Christian Science Monitor

“What you’ve done, brilliantly, is to raise many questions that people are debating.” — Diane Rehm, The Diane Rehm Show

“[Menzies] makes history sound like pure fun...a seductive read.” — New York Times Magazine

About the Author

Gavin Menzies (1937-2020) was the bestselling author of 1421: The Year China Discovered America ; 1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance ; and The Lost Empire of Atlantis: History's Greatest Mystery Revealed . He served in the Royal Navy between 1953 and 1970. His knowledge of seafaring and navigation sparked his interest in the epic voyages of Chinese admiral Zheng He.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Harpercollins publishers, inc., chapter one, the emperor's grand plan.

On 2 february 1421, China dwarfed every nation on earth. On that Chinese New Year's Day, kings and envoys from the length and breadth of Asia, Arabia, Africa and the Indian Ocean assembled amid the splendours of Beijing to pay homage to the Emperor Zhu Di, the Son of Heaven. A fleet of leviathan ships, navigating the oceans with pinpoint accuracy, had brought the rulers and their envoys to pay tribute to the emperor and bear witness to the inauguration of his majestic and mysterious walled capital, the Forbidden City. No fewer than twenty-eight heads of state were present, but the Holy Roman Emperor, the Emperor of Byzantium, the Doge of Venice and the kings of England, France, Spain and Portugal were not among them. They had not been invited, for such backward states, lacking trade goods or any worthwhile scientific knowledge, ranked low on the Chinese emperor's scale of priorities.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of Zhu Yuanzhang, who had risen to become the first Ming emperor despite his lowly birth as the son of a hired labourer from one of the poorest parts of China. In 1352, eight years before Zhu Di's birth, a terrible flood had struck parts of China. The Yellow River had burst its banks, submerging vast areas of farmland, washing away villages and leaving famine and disease in its wake. The country was still in the throes of a terrible epidemic. The Mongols had ruled China since its conquest in 1279 by the great Kublai Khan, grandson of the greatest warlord of them all, Genghis Khan. But in 1352, plagued by famine and disease and desperately poor as a result of the depredations of their Mongol overlords, the peasants around Guangzhou on the Pearl River delta rose in revolt. Zhu Yuanzhang joined the rebels and rapidly emerged as their leader, rallying soldiers and farmers to his cause. During the next three years the revolt spread throughout China. Over decades of peace, the once ferocious Mongol warriors, the scourge of all Asia, had grown idle and complacent. Riven by internal dissension, they proved no match for the army raised by Zhu Di's father. In 1356, his forces captured Nanjing and cut off corn supplies to the Mongols' northern capital, Ta-tu (Beijing).

Zhu Di was eight years old when his father's army entered Ta-tu itself. The last Mongol Emperor of China, Toghon Temur, fled the country, retreating north to the steppe, the Mongol heartland. Zhu Yuanzhang pronounced a new dynasty, the Ming, and proclaimed himself the first emperor, taking the dynastic title Hong Wu. Zhu Di joined the Chinese cavalry and proved himself a brave and skilful officer. At the age of twenty-one he was sent to join the campaign against the Mongol forces still occupying the mountainous south-western province of Yunnan, bordering modern Tibet and Laos, and in 1382 he was ordered to destroy Kun Ming, to the south of the Cloud Mountains, the remaining Mongol stronghold in the province. After the city was taken, the Chinese butchered the adult defenders and castrated those prisoners who had not reached puberty. Thousands of young Mongol boys had their penises and testicles severed. Many perished of shock and disease; the surviving eunuchs were conscripted into the imperial armies or kept as servants or retainers.

Eunuchs served as 'palace menials, harem watch dogs and spies' for rulers throughout the ancient world, in Rome, Greece, North Africa and much of Asia, and they had played an important role throughout Chinese history. Surprisingly, they were intensely loyal to the emperors who had authorized their mutilation. There had been eunuchs at the imperial court since at least the eighth century BC and as many as seventy thousand were employed in and around the capital. Only sexless males were permitted to act as personal servants to the emperor and to guard the women of his family and the quarters occupied by his concubines in the 'Great Within', inside the palace doors. Emperors retained thousands of concubines both as a symbol of their power and to ensure a number of male heirs at a time of high infant mortality; guaranteeing the continuity of the dynasty and the worship of ancestors was a vital part of Chinese cultural rites. Non-eunuchs, even relatives of the emperor and his consorts, were barred from the vicinity of the women's quarters on pain of death. The absence of potent males ensured that any children born to the concubines had been sired by the emperor alone.

Eunuchs also helped to preserve the aura of sanctity and secrecy that surrounded the imperial throne. While the gods granted a 'Mandate of Heaven' to legitimize the emperor's rule, they could rescind it if he proved guilty of human failings, misgovernment or misconduct. It was forbidden to look upon the emperor: even senior officials kept their eyes downcast in the imperial presence, and when he passed through the streets, screens were erected to shield him from public gaze. Only the 'effeminate, cringing eunuchs', slavishly dependent upon the emperor for their very lives, were considered cowed enough to be silent witnesses to his private foibles and weaknesses.

Ma He, one of the boys castrated at Kun Ming, was billeted in the household of Zhu Di, where his name was changed to Zheng He. Many of the Mongols whom Zhu Di and his father expelled had adopted the Muslim faith. Zheng He was a devout Muslim besides being a formidable soldier, and he became Zhu Di's closest adviser. He was a powerful figure, towering above Zhu Di; some accounts say he was over two metres tall and weighed over a hundred kilograms, with 'a stride like a tiger's'. When Zhu Di was elevated to Prince of Yen -- a region centred on Beijing -- and given the new and more important responsibility of guarding China's northern provinces, Zheng He went with him.

Product details

- Publisher : William Morrow Paperbacks (June 3, 2008)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 650 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0061564893

- ISBN-13 : 978-0061564895

- Item Weight : 1.81 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1.34 x 9 inches

- #159 in Chinese History (Books)

- #189 in Expeditions & Discoveries World History (Books)

- #228 in Naval Military History

About the author

Gavin menzies.

GAVIN MENZIES was born in 1937 and lived in China for two years before World War II. He joined the Royal Navy in 1953 and served in submarines from 1959 to 1970. In the course of researching 1421, he visited 120 countries, over 900 museums and libraries, and every major sea port of the late Middle Ages. He is married with two daughters and lives in North London.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Education During Coronavirus

A Smithsonian magazine special report

You Can Now Explore 200 Years of Chinese American History Online

The Museum of Chinese in America launched the digital platform one year after a fire devastated its archives

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

Livia Gershon

Daily Correspondent

:focal(890x754:891x755)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/33/5f33515d-b677-47cc-b138-fc0cec1b8425/screen_shot_2021-01-25_at_123321_pm.png)

On January 23, 2020, a devastating fire nearly destroyed the New York City archives of the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA). One year later, reports Nancy Kenney for the Art Newspaper , the cultural institution has launched a new digital platform that makes hundreds of items from its collection freely available for the public to explore.

Hosted by Google Arts & Culture , the online portal boasts more than 200 artifacts, including newspaper clippings, historical photos, restaurant signs, political campaign posters and images of art by Chinese Americans. Highlights of the virtual display range from a quilt —created by artist Debbie Lee for a 1989 MOCA exhibition—that shows images of workers in the garment industry to Chinese musical instruments , an early 20th-century typewriter with Chinese characters and a 1973 handbook aimed at fighting the stereotyping of Asian Americans in media.

The platform also includes a virtual tour of the museum. Titled “ With a Single Step: Stories in the Making of America ,” the experience allows visitors to move through a 3-D model of rooms containing art and artifacts from Chinese American communities. Another digital exhibit, “ My MOCA Story ,” offers thoughts on the significance of specific artifacts from museum staff, Chinese American cultural and political leaders, and other community members. Phil Chan , co-founder of the organization Final Bow for Yellowface , discusses the stereotypical Fu Manchu mustache in the context of his work to change depictions of Asian people in ballet, while psychologist Catherine Ma spotlights ceramic figurines created by a family business in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Another virtual exhibition, “ Trial by Fire: The Race to Save 200 Years of Chinese American History ,” tells the story of the museum’s, city workers’ and supporters’ responses to last year’s fire. It includes clips of news stories, photographs and social media posts from the weeks directly after the blaze. Also featured in the exhibition is footage of MOCA’s temporary recovery area on the first day of the salvage effort.

The building where the fire occurred—located at 70 Mulberry Street in Chinatown—served as the museum’s home until 2009. At the time of the fire, it held MOCA’s Collections and Research Center . The museum itself, now based at 215 Centre Street, was not affected by the fire but is currently closed due to Covid-19.

Per the Observer ’s Helen Holmes, the museum’s staff had already digitized more than 35,000 objects prior to the fire. Workers were later able to salvage many physical objects from the archives, including personal mementos donated by director Ang Lee, delicate paper sculptures, and compositions and notes from the musical Flower Drum Song .

As Annie Correal reported for the New York Times in January 2020, 70 Mulberry Street also housed a dance center, community groups and a senior center. Salvage efforts were delayed after the building was declared structurally unsound, but workers eventually found that the damage to the collection was less severe than originally feared, according to Gothamist ’s Sophia Chang. Ultimately, the Art Newspaper reports, workers salvaged 95 percent of the materials in the archives, though many objects suffered water damage. The items are now at a temporary collections and research center near the Mulberry Street location.

“One of the unexpected silver linings of this period of time are creative and intentional new partnerships,” says museum President Nancy Yao Maasbach in a statement . “MOCA is incredibly grateful to Google Arts & Culture to expand MOCA’s usership, which will inevitably broaden the much-needed scholarship in the areas related to the Chinese American narrative in America.”

In the wake of the fire, museum staff created a crowdfunding campaign that has now raised more than $464,000. And, in October the Ford Foundation announced a $3 million grant supporting the museum.

“This is an absolute game changer for us,” Maasbach told the Times ’ Julia Jacobs. “Given the situation with the shuttered operations, we were really struggling. We were really counting every penny.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

Livia Gershon | | READ MORE

Livia Gershon is a daily correspondent for Smithsonian. She is also a freelance journalist based in New Hampshire. She has written for JSTOR Daily , the Daily Beast , the Boston Globe , HuffPost and Vice , among others.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

America Was Eager for Chinese Immigrants. What Happened?

By Michael Luo

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, settlement of America’s western frontier generally reached no farther than the Great Plains. The verdant land that Spanish conquistadors called Alta California had been claimed by Spain and then by Mexico, after it secured its independence, in 1821. In 1844, James K. Polk won the Presidency as a proponent of America’s “manifest destiny,” the belief that it was God’s will for the United States to extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, and soon took the country into a war with Mexico. Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in 1848, Mexico ceded California to the United States, along with the vast expanse of land that today comprises Nevada, parts of Arizona, and New Mexico.

California was sparsely populated and almost wholly separate from the rest of the country. Sailing there from the Eastern Seaboard, around South America, could take six months, and the overland journey was even more arduous. The fledgling town of San Francisco consisted of a collection of wood-frame and adobe buildings, connected by dirt paths, spread out on a series of slopes. Fewer than a thousand hardy inhabitants, many of them Mormons fleeing religious persecution, occupied the sandy, windswept settlement.

That changed with remarkable suddenness. On the morning of January 24, 1848, James W. Marshall was inspecting progress on the construction of a sawmill on the banks of the American River, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains, about a hundred and thirty miles northeast of San Francisco. In his recounting, he spotted some glints in the water and picked up one or two metallic fragments. After studying them closely, he realized that they might be gold. Several days later, he returned to New Helvetia, a remote outpost in the Sacramento Valley, where he asked his business partner, John Sutter, to meet with him alone. The two men conducted a test with nitric acid and satisfied themselves that the find was genuine. Sutter implored those working the mill to keep quiet about the discovery, but, in May, 1848, a Mormon leader who owned a general store at the outpost travelled to San Francisco and heralded stunning news. “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” he reportedly shouted as he strode through the streets, holding aloft a bottle full of gold dust and waving his hat. Within a few weeks, most of San Francisco’s male population had decamped for the hills. The town’s harbor was soon filled with abandoned ships whose crews had rushed off in search of wealth.

It is uncertain exactly how word of the gold rush reached China. According to one account, a visiting merchant from Guangdong Province named Chum Ming was among the many men who ventured into the Sierra Nevada foothills and struck it rich. As the story goes, Chum Ming wrote to a friend back home, and the news began to circulate. Mae Ngai, a professor of Asian American studies at Columbia University, begins her book “ The Chinese Question ” (Norton) with a more verifiable fact: the arrival of a ship carrying California gold––specifically, two and a half cups of gold dust––in Hong Kong on Christmas Day, 1848. A San Francisco agent of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the fur-trading concern, had requested that British experts in China evaluate it. The ship also brought copies of the Polynesian , a Honolulu newspaper, which reported on the immense quantities of gold being extracted by prospectors in California.

Soon, word spread through villages across the Pearl River Delta, a populous area in southeastern China. At the time, it was illegal for Chinese citizens to leave the country, and Qing-dynasty officials offered little protection for emigrants. Nevertheless, men throughout the region began booking passage on ships bound for Gum Shan—Gold Mountain. Ngai writes that they were just like other gold seekers from around the world: farmers, artisans, and merchants, who mostly paid their own way or borrowed money for the voyage to America. The trip across the ocean was frequently a miserable experience. It generally took ten to twelve weeks to sail from Hong Kong to San Francisco. Shipmasters often stuffed the men into overcrowded, poorly ventilated, disease-ridden holds. One ship arrived in San Francisco harbor having lost a hundred Chinese en route, a fifth of those on board. “There can be no excuse before God or man for the terrible mortality which has occurred on some of the vessels containing Chinese passengers,” William Speer, a Presbyterian missionary who treated many Chinese after they disembarked in San Francisco, wrote.

In 1849, three hundred and twenty-five Chinese passed through San Francisco’s customhouse. The next year, the number increased to four hundred and fifty; the year after that, it was twenty-seven hundred. In 1852, the arrivals jumped to more than twenty thousand. By the late eighteen-fifties, Chinese immigrants made up about ten per cent of the state’s population, and even more in mining districts. California, teeming with white Americans, Native people, Mexicans, Blacks, Chinese, Irish, Germans, Frenchmen, Hawaiians, and others, had become the substrate for a nettlesome experiment in multiracial democracy that had little precedent in the country’s history.

At first, the reception for the Chinese in America was generally positive. In the summer of 1850, city leaders in San Francisco held a ceremony to welcome them. A small group of Chinese immigrants assembled in Portsmouth Square and were presented with Chinese books, Bibles, and religious tracts. The Reverend Albert Williams, of the First Presbyterian Church, who was among the speakers, later wrote that they were united in conveying “the pleasure shared in common by the citizens of San Francisco, at their presence,” and in the hope that more of their brethren would join them in America, where they would enjoy “welcome and protection.” In January, 1852, in an annual message to the state legislature, John McDougal, California’s second governor, called for more Chinese to come. McDougal, a Democrat, had advocated at California’s constitutional convention for excluding from the state certain classes of Black people. But he believed the Chinese could be a source of cheap labor for white Americans. He suggested that the Chinese, “one of the most worthy classes of our new adopted citizens,” could help with the gruelling work of draining swamplands to make them arable. Many California businessmen envisaged a golden age of trade between China and the United States and embraced Chinese immigration as part of that interchange.

Link copied

As the numbers of Chinese climbed, however, curiosity gave way to hostility in the mining districts. In the spring of 1852, a gathering of miners in the town of Columbia, in the Sierra Nevada foothills, approved resolutions that denounced the flooding of the state with “degraded Asiatics” and barred Chinese from mining in the area. Around the same time, along the banks of the north fork of the American River, several dozen white miners reportedly drove off two hundred Chinese miners, and then, accompanied by a band playing music, headed to another camp to do the same to four hundred more.

Ngai explains that McDougal’s successor as governor, John Bigler, a Democrat facing a difficult reëlection campaign, recognized a political opportunity in the growing anti-Chinese sentiment. In April, 1852, he called on the state legislature to limit Chinese immigration. His speech was filled with racial overtones, alluding to a coming inundation from China and misleadingly depicting Chinese immigrants as coolie laborers, bound by oppressive contracts. Bigler’s tarring of the Chinese as a “coolie race” would prove to be a resilient epithet, becoming a convenient political instrument whenever white Americans on the West Coast needed a racial scapegoat, Ngai writes. The label likened the Chinese to enslaved Black people and, therefore, cast them as a threat to free white labor. Bigler explicitly differentiated the Chinese from white European immigrants, arguing that the Chinese had come to America not to receive the “blessings of a free government” but only to “acquire a certain amount of the precious metals” and then return home. He also doubted that the “yellow or tawny races of the Asiatics” could become citizens under the country’s naturalization laws even if they wanted to. Anti-coolieism, Ngai writes, became a kind of shape-shifting, racist cause.

The Chinese of the gold-rush era are mostly anonymous to us today. The absence of their voices from historical accounts perhaps contributes to the mistaken impression that they were passive in the face of abuse. Ngai helps make clear that this was far from the case. Shortly after Bigler’s 1852 comments, for instance, two Chinese merchants, Hab Wa and Tong Achick, issued a confident retort that was republished in newspapers across the country. Growing up in Macau, Tong had attended a school founded by Protestant missionaries, and he was fluent in English. He was the head of one of the biggest Chinese-owned businesses in San Francisco. He and Hab went to great lengths to dismantle Bigler’s claims. “The poor Chinaman does not come here as a slave,” they wrote. “He comes because of his desire for independence, and he is assisted by the charity of his countrymen, which they bestow on him safely, because he is industrious and honestly repays them. When he gets to the mines, he sets to work with patience, industry, temperance, and economy.” They insisted, too, that Bigler was wrong that the Chinese were not interested in citizenship: “If the privileges of your laws are open to us, some of us will doubtless acquire your habits, your language, your ideas, your feelings, your morals, your forms, and become citizens of your country.”

The citizenship issue underscored the ways in which the Chinese complicated America’s racial stratification. The Nationality Act of 1790 stipulated that you had to be a “free, white person” of “good character” to qualify for naturalization, but Ngai points out that some Chinese did manage to become citizens during the nineteenth century. Norman Assing, a prominent Chinese merchant, was apparently one of them. In 1849, Assing (whose Chinese name was Yuan Sheng), having previously spent time in New York and Charleston, South Carolina, arrived in San Francisco, where he opened a restaurant, started a trading company, and became an important leader in the Chinese community. His own response to Bigler was published in a San Francisco newspaper a month after the comments. Assing, who described himself as “a Chinaman, a republican, and a lover of free institutions,” assailed Bigler for a message that threatened to “prejudice the public mind against my people, to enable those who wait the opportunity to hunt them down, and rob them of the rewards of their toil.” The Framers of the Constitution, he maintained, would never have countenanced “an aristocracy of skin.”

As Chinese immigration increased, mutual-aid organizations, or huiguan , representing people from different regions and dialect groups, formed to assist new arrivals. Most immigrants came from just four counties, in the western part of the Pearl River Delta, and each had its own huiguan . Why this parcel of China, no bigger in size than Connecticut, accounted for so much immigration to America remains the subject of debate. When the inhabitants of the Siyi, as the counties are known, began making their way to America, it was a time of upheaval in their homeland. The population had risen, making land increasingly scarce. Political tumult was also roiling China. The worst unrest came during the Taiping Rebellion, in which at least ten million people were killed. In Guangdong, an insurgency by members of a secret society, who became known as the “red turbans,” and a savage conflict between the Punti population and the Hakka, a minority group, contributed to the turmoil. Yet other regions of China experienced greater economic privation, and the timing and the location of the upheavals don’t quite correspond with the overseas exodus. A decisive factor seems to be that the inhabitants of the Pearl River Delta were unusually familiar with the West. Canton (now Guangzhou), the provincial capital, had a long history as an important trading port and had extensive ties to California. It was also a frequent destination for American merchants and missionaries. Hong Kong, another commercial hub, was just a short journey away by boat.

In early 1853, the heads of the four huiguan met with members of the state assembly’s committee on mines and mining interests. Through Tong Achick, who served as the group’s interpreter and represented one of the associations, the huiguan leaders condemned the mistreatment of Chinese immigrants in the mines and voiced other grievances, including the fact that Chinese testimony was not being allowed in court. The committee members were, in many respects, sympathetic. In the majority report, they expressed skepticism that America was in danger of being overrun by Chinese and pushed for an expansion of trade between the two countries. The huiguan leaders, for their part, promised to do their utmost to discourage more of their countrymen from coming. “We have no authority there, but very confidently believe we could exert much influence,” Tong said, suggesting that immigration would soon taper off. The promise of Gold Mountain riches, however, proved irresistible. Despite rising hostilities, the Chinese continued to come.

Huie Kin was born in 1854 and grew up in Wing Ning, a tiny rice-farming village of about seventy people tucked away in the hills of Xinning (known today as Taishan), an impoverished, mountainous county in Guangdong Province. At one end of the village was a bamboo grove; at the other was a fishpond. Huie shared a room with his father, along with the family cow; the kitchen stove occupied one corner. His mother slept in the only other room. Because the space was so cramped, Huie’s two brothers slept at the village shrine; his two sisters spent their nights at a home for unmarried girls.

One day, as he later recalled in a memoir, a member of his clan returned from America with stories of gold found in riverbeds. Huie became obsessed with travelling to Gold Mountain, and three cousins joined him in his resolve. To Huie’s surprise, his father supported his decision, and borrowed money from a wealthy neighbor, using their family farm as security on the loan, to pay for his passage. On a spring day in 1868, the fourteen-year-old Huie and his three cousins left their village before daybreak, each with just a bedroll and a bamboo basket carrying their belongings, and caught a small boat to Hong Kong. While waiting for their ship to depart for America, Huie spent his days on the waterfront; he saw his first Europeans, “strange people, with fiery hair and blue-grey eyes.” Finally, they set sail on a large ship with three heavy masts and billowing sails. Midway through the two-month voyage, Huie’s eldest cousin, the leader of their group, suddenly became feverish and died; his body was wrapped in a sheet and lowered into the ocean. Huie and his other cousins stood for hours staring out into the inky blackness, overwhelmed by grief. When the fog lifted on a cool September morning and they finally glimpsed land, the feeling was indescribable, as he later wrote: “To be actually at the ‘Golden Gate’ of the land of our dreams!”

By the time Huie and his cousins arrived in California, the gold rush there was over. Most of the easily worked claims were depleted. Individual prospecting in creeks and streams––washing and sifting dirt, looking for gold nuggets––had given way to larger-scale industrial mining operations that employed legions of Chinese. Some Chinese miners moved on to other territories, such as Oregon and Idaho, where gold had been discovered as well. Huie’s first job was as a household servant, making a dollar-fifty a week. Thousands of other Chinese earned wages building the transcontinental railroad which were far more lucrative than they could garner in China. Still more were employed in factories making cigars, slippers, and woollen garments; some even began running their own factories. Others capitalized on their success in the goldfields to open stores or restaurants.

Gold Mountain prosperity set in motion a cycle of migration. Fathers sent for sons; brothers wrote to brothers and cousins; returning villagers inspired others to venture across the ocean. Lee Chew was a sixteen-year-old in Guangdong when a man came back from America and constructed a palatial estate in their village, taking up four city blocks. “The man had gone away from our village a poor boy,” Lee later wrote. “Now he returned with unlimited wealth, which he had obtained in the country of the American wizards.” Lee said he became fixated on the idea that he, too, could become a wealthy man in America. His father gave him the equivalent of a hundred dollars, and Lee travelled to Hong Kong with five other boys from his village. They each paid fifty dollars for steerage passage on a steamship to America. He worked for two years as a household servant and then started a laundry, before eventually opening a store in New York’s Chinatown.

In the mid-eighteen-seventies, the United States entered into a prolonged economic depression. By 1877, nearly a quarter of the workforce in San Francisco was reportedly unemployed. The result was a cauldron of fifteen thousand idle white workmen. Anti-coolie clubs spread, calling for boycotts against goods that did not have a label that said “Made by White Labor.” Violence against the Chinese became increasingly frequent. “The Chinese were in a pitiable condition in those days,” Huie Kin recalled. “We were simply terrified; we kept indoors after dark for fear of being shot in the back. Children spit upon us as we passed by and called us rats.”

Even though several million Irish and German immigrants had streamed into American cities, it was whites’ resentment toward the Chinese that became a virulent nationwide movement. In 1876, the national platforms of both the Republicans and the Democrats singled out “Mongolian” immigration as a problem. (As Ngai observed, for the party of Lincoln, in particular, the stand marked a shocking retreat from the principles of equal rights.) On May 6, 1882, President Chester Arthur signed into law a ban on the immigration of Chinese laborers, which became known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. The law also prohibited Chinese from becoming naturalized citizens. For the first time in its history, America closed its gates to a class of people on the basis of race.

But the violence against the Chinese did not stop. “ The Chinese Must Go ” (Harvard), by Beth Lew-Williams, a history professor at Princeton, includes a list of almost two hundred communities that between 1885 and 1887 expelled, or attempted to expel, Chinese. In Tacoma, a group of white vigilantes forced about two hundred Chinese to leave, in November, 1885, and the Chinese sent anguished telegrams to the authorities, begging for help: “People driving Chinamen from Tacoma. Why sheriff no protect. Answer.”

Handwritten letters in neat cursive from officials in the Chinese legation to Thomas Bayard, the Secretary of State, read like a diary of violence. American-style pogroms raged in Squak Valley, Coal Creek, Tacoma, Seattle, and on and on. In September, 1885, two Chinese officials and an interpreter travelled to Rock Springs, in the Wyoming Territory, to investigate a brutal episode in which white coal miners massacred at least twenty-eight Chinese and drove out several hundred others, torching their homes and firing on them as they fled. A report from Huang Sih Chuen, the Chinese consul in New York, identified each Chinese victim: “Tom He Yew was 34 years. He had a mother, wife and daughter at home. Mar Tse Choy was 34 years. He had parents, wife and daughter at home. Leo Lung Siang was 36 years. He had a wife at home.” Husbands, brothers, fathers, sons, killed in a faraway land where they would never cease to be regarded as strangers.

The ordeal of the Chinese in America is only a portion of the history of persecution documented in “The Chinese Question.” Ngai’s principal insight is that the story of Chinese exclusion is a global one. Soon after the American gold rush began, hundreds of thousands of fortune hunters from around the world began converging on British colonies in Australia, after gold was discovered there. Just as in America, violence and efforts to halt the influx followed, culminating in a series of initiatives that came to be known as the “White Australia” policy. Early in the twentieth century, the British colony known as Transvaal, in southern Africa, became the setting for another harrowing episode for Chinese migrants, after mining magnates began importing tens of thousands of indentured laborers from China. Deep antagonism developed between Chinese miners and their white bosses, triggering violence, strikes, and other disturbances. In 1907, a newly elected colonial government in Transvaal, led by two Afrikaners who favored white supremacy and racial segregation, ended the Chinese-labor program. At the same time, the government moved to restrict Asian immigration and the rights of Indians and Chinese living in the colony. Ngai points out the similarity to the anti-coolieism rhetoric on the other side of the world: “Americans and British alike opposed the ‘slavery’ of the Chinese—but did not support their freedom.”

In the United States, the Chinese-exclusion laws were not repealed until 1943, and the impetus was not an overdue reckoning with the country’s egalitarian values but a shift in the geopolitical order. China had become an ally of the United States in its war against Japan. Still, the number of Chinese immigrants allowed into the country was negligible. The national-origins quota system that favored immigration from northern and western Europe was not set aside until 1965. Australia and South Africa did not begin to lift their restrictions on Chinese immigration until the nineteen-seventies. The grandchildren of Chinese immigrants who survived the bigotry and violence of the late nineteenth century in America are the grandparents of fifth-generation Chinese Americans today.

More than a century later, the global struggle over the Chinese Question has receded, but the complicated racial dynamics resulting from Asian immigration to the Western world have not. The years from the California gold rush to the end of the Chinese-labor program in South Africa coincided with a humbling period for China, as it contended with foreign incursions, internal rebellions, and financial crises. Today, by contrast, China is an economic, political, and military juggernaut, vying with the United States for global influence. Both Democrats and Republicans have sought to amplify the threat posed by China’s authoritarian regime. This approach has raised anew the bugbear of the unassimilable Other in our midst. When President Trump spoke about the “China virus” and the “kung flu,” it was possible to hear echoes of John Bigler invoking Chinese coolies, and British settlers warning about the Asian hordes. “The Chinese Question never really went away,” Ngai writes. “The idea that China poses a threat to Euro-American civilizations remained just beneath the surface.”

And yet the status of Asian immigrants in America today is, indisputably, different. The United States is undergoing a demographic transformation. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the country; their numbers have grown twentyfold since 1965. Much of the modern wave of immigration has been linked to skill-based allocations, and the Asian immigrant has often come to be seen as a success story, the “model minority.” It’s a misleading characterization; income inequality among Asian Americans is the highest of any racial or ethnic group. Nevertheless, Asian immigrants are no longer viewed as definitively nonwhite, as they were in the nineteenth century; in some circles, they’re considered “white-adjacent.” The historian Ellen D. Wu has traced the emergence of the model-minority story to Cold War imperatives, as American policymakers sought to renovate the country’s image, amid the tumult over the civil rights of Black Americans. In a contest of moral suasion, a narrative of Asian American ascent was a powerful way to burnish the credentials of the United States as a beacon of freedom and opportunity for all. But the surge in anti-Asian attacks during the coronavirus pandemic is merely the latest evidence of the brittleness of this narrative. Overt discrimination against Chinese or other Asian immigrants may no longer be legally sanctioned, and violent expulsions of Chinese may be a matter of history, but for many Asian Americans a sense of belonging remains elusive. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

- Snoozers are, in fact, losers .

- The book for children that is an amphibious celebration of same-sex love .

- Why the last snow on Earth may be red.

- The case for not being born .

- A pill to make exercise obsolete .

- The fantastical, earnest world of haunted dolls on eBay .

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jiayang Fan

By Casey Cep

By Susan B. Glasser

By Geraldo Cadava

New Evidence Ancient Chinese Explorers Landed in America Excites Experts

- Read Later

By Tara MacIsaac , Epoch Times

John A. Ruskamp Jr., Ed.D., reports that he has identified an outstanding, history-changing treasure hidden in plain sight. High above a walking path in Albuquerque’s Petroglyph National Monument, Ruskamp spotted petroglyphs that struck him as unusual. After consulting with experts on Native American rock writing and ancient Chinese scripts to corroborate his analysis, he has concluded that the readable message preserved by these petroglyphs was likely inscribed by a group of Chinese explorers thousands of years ago.

On the fringe of archaeology have long been claims that the Chinese reached North America long before Europeans. With some renowned experts taking interest in Ruskamp’s discovery, those claims may be working their way from the fringe to the core.

It doesn’t mean our history textbooks will change tomorrow. Anything short of discovering an undisturbed early Asiatic relic or village in the Americas may fail to convince those archaeologists who have dogmatically rejected evidence of an ancient Chinese presence in the New World, said Ruskamp.

But, the disparate and widespread symbols he has found show many indications of authenticity. They have the potential to inspire a more serious investigation into early trans-Pacific interaction. To date, Ruskamp has identified over 82 petroglyphs matching unique ancient Chinese scripts not only at multiple sites in Albuquerque, New Mexico, but also nearby in Arizona, as well as in Utah, Nevada, California, Oklahoma, and Ontario. Collectively, he believes that most of these artifacts were created by an early Chinese exploratory expedition, although some appear to be reproductions made by Native people for their own purposes.

- Did China discover America 70 years before Columbus?

- Ancient Bronze Artifacts in Alaska Reveals Trade with Asia Before Columbus Arrival

- Sea-Farers from the Levant the first to set foot in the Americas: proto-Sinaitic inscriptions found along the coast of Uruguay

One of Ruskamp’s staunchest supporters has been David N. Keightley, Ph.D., a MacArthur Foundation Genius Award recipient who is considered by many to be the leading analyst in America of early Chinese oracle-bone writings. Keightley has helped Ruskamp decipher the scripts he has identified. One ancient message, preserved by three Arizona cartouche petroglyphs, translates as: “Set apart (for) 10 years together; declaring (to) return, (the) journey completed, (to the) house of the Sun; (the) journey completed together.” At the end of this text is an unidentified character that may be the author’s signature.

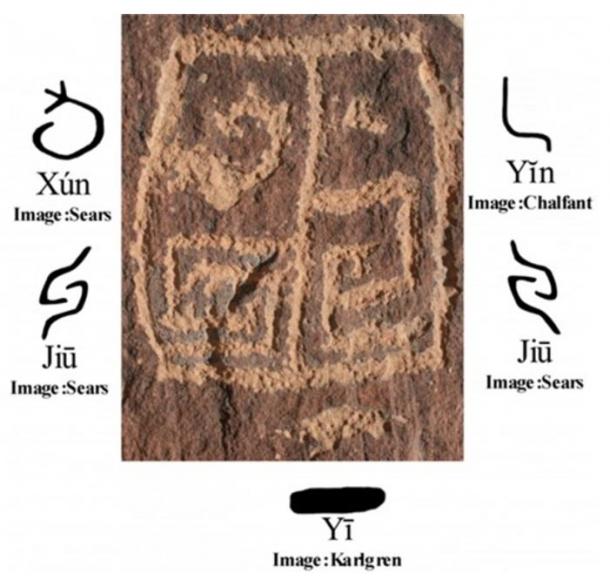

Cartouche 1, which reads “Set apart (for) 10 years together.”(Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

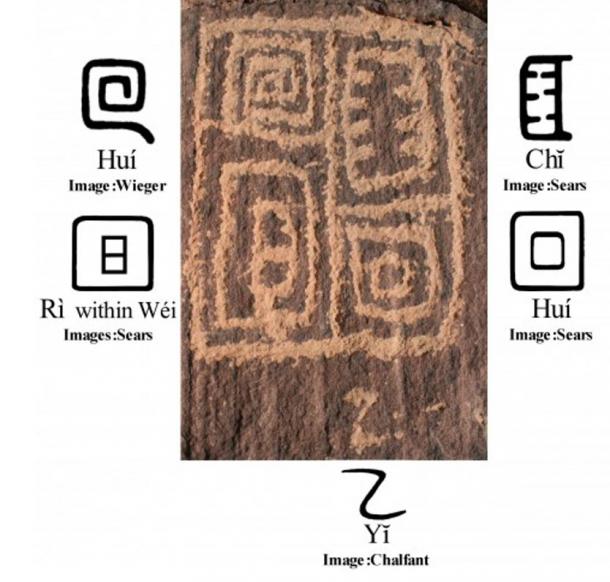

Cartouche 2, which reads, “Declaring (to) return, (the) journey completed, (to the) house of the Sun.” (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

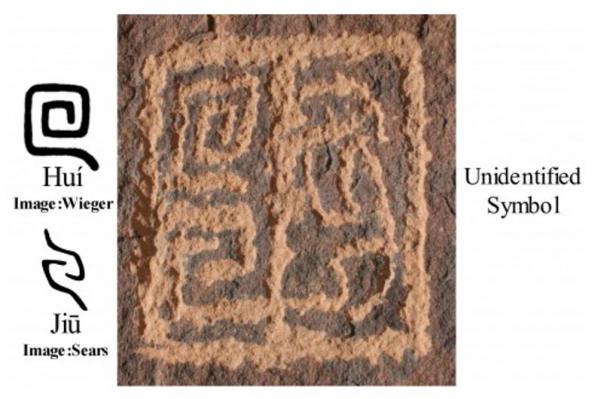

Cartouche 3, which reads, “(The) journey completed together.” (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

The Arizona glyph site on what has always been, and still is, very private ranch property located miles from any public access or road. (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

The oracle-bone style of writing employed for creating a number of these ancient petroglyph scripts disappeared by royal decree from mankind’s memory around 1046 B.C., following the fall of the Shang Dynasty. It remained an unknown and totally forgotten form of writing until it was rediscovered in A.D. 1899 at Anyang, China. Ruskamp thus concluded that the mixed styles of Chinese scripts found in these Arizona petroglyphs indicates that they were made during a transitional period of writing in China, not long after 1046 B.C.

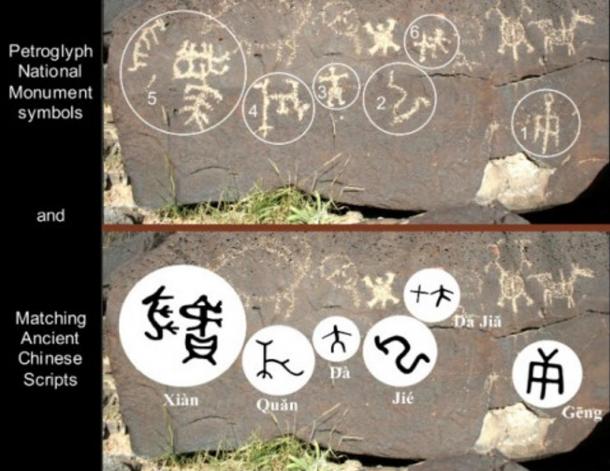

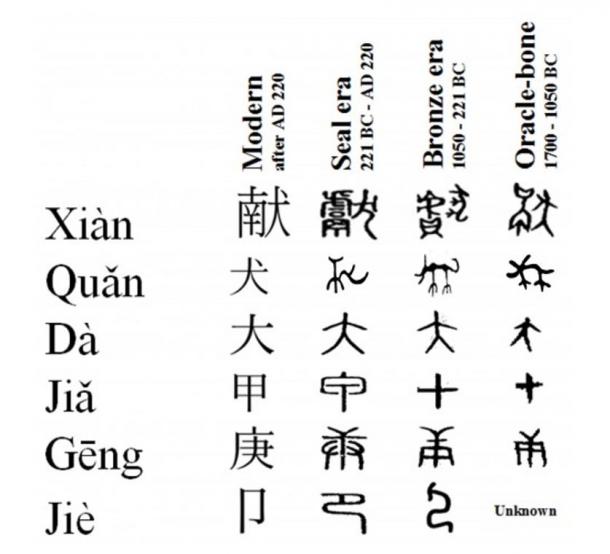

Ruskamp gives the following translation for the Albuquerque petroglyphs: “Gēng (a date; the seventh Chinese Heavenly Stem); Jié (to kneel down in reverence); Da (great—referring to a superior); Quăn (dog—the sacrificial animal); Xiàn (offering worship to deceased ancestors); and Dà Jiă (the name of the third king of the Shang dynasty).”

Albuquerque petroglyphs (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

The Albuquerque petroglyphs use both Seal era and Bronze era Chinese scripts, suggesting they were also written during a transitional period in Chinese calligraphy, likely between 1046 B.C. and 475 B.C. The use of the title “Da” before the name “Jiă,” suggests a date close to the end of the Shang Dynasty in 1046 B.C., as this appellation emerged during that time period and was replaced shortly thereafter.

A comparison of scripts over time. (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Michael F. Medrano, Ph.D., chief of the Division of Resource Management for Petroglyph National Monument, studied the petroglyphs at that location upon Ruskamp’s request. He said that, based on his more than 25 years of experience with local Native cultures, “These images do not readily appear to be associated with local tribal entities,” and “based on repatination appear to have antiquity to them.”

It is difficult to physically date petroglyphs with absolute certainty, notes Ruskamp. Yet the syntax and mix of Chinese scripts found at these two locations correspond to what experts would expect explorers from China to use some 2,500 years ago.

For example, the Arizona ranch petroglyphs are divided into three sections each enclosed in a square known as a cartouche. Two of the cartouches are numbered; one with the Chinese script for “one” placed beneath it and in a similar manner the second cartouche has the ancient Chinese script meaning “second” inscribed beneath it. Together these numeric figures indicate the order in which these images should be read. Importantly, the cartouches are thus shown to be read in the traditional Chinese manner, from right to left.

The first two cartouches are rotated 90 degrees to the left of vertical and the third is rotated 90 degrees to the right. “The deliberate rotation of these writings, both to the left and right of vertical by an equal number of degrees, endorses their authenticity, for the rotation of individual scripts by Chinese calligraphers is well-documented,” wrote Ruskamp.

Some of the symbols found in the petroglyphs are common to both Chinese script and ancient Native American writing. For instance, “The Chinese petroglyph figure of Jiu conveys the idea of “togetherness,” in much the same manner as the Nakwach symbol is now, and has been in the past, understood by the Hopi,” wrote Ruskamp.

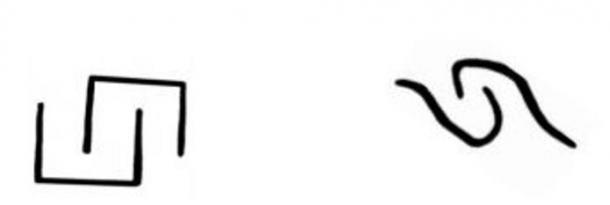

Left: Hopi Nakwách symbol. Right: Chinese petroglyph figure of Jiu. (Sears; Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Another similarity is the use of a rectilinear spiral to convey the concept of a “round-trip journey.”

A rectilinear spiral similarly used by the Chinese and the Hopi to convey the concept of a “round-trip journey.”(Wieger; Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Though these similarities could be conceived as supporting a Native American origin for Ruskamp’s petroglyphs, Ruskamp stated: “The extensive Chinese vocabulary evidenced at each location advocates against the authorship of the figures evaluated in this study being credited to Native Americans. None of the more complex Chinese figures identified in this report are known to have any Native tribal affiliation.”

The conclusion of his paper titled “Ancient Chinese Rock Writings Confirm Early Trans-Pacific Interaction,” reads: “In contrast to any previous historical uncertainty, the comparative evidence presented in this report, which is supported by both analytical evaluation and expert opinion, documenting the presence of readable sequences of old Chinese scripts located upon the rocks of North America, establishes that prior to the extinction of oracle-bone script from human memory, approximately 2,500 years ago, trans-Pacific exchanges of epigraphic intellectual property took place between Chinese and North American populations.”

He published the paper on his website, Asiaticechoes.org, in April and it is currently under peer review. Last October, he began presenting his findings in speaking engagements, including most recently to the Association of American Geographers in Chicago. He will next present at a meeting of the Little Colorado River Chapter of the Arizona Archaeology Society in Springerville, Arizona, on May 18. The editors of the journal Pre-Columbiana have confirmed they will soon publish Ruskamp’s article. The journal is edited by Professor Emeritus Stephen C. Jett, Ph.D., University of California–Davis, with the assistance of an editorial board of distinguished professional scholars, and is dedicated to exploring Pre-Columbian transoceanic contact.

A retired educator, statistician, and analytical chemist, Ruskamp pursued his study of petroglyphs as a hobby—little expecting to find what may lead to a great shift in how we view both American and Chinese history.

Featured image: Arizona cartouche petroglyphs. (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

The article ‘ New Evidence Ancient Chinese Explorers Landed in America Excites Experts ’ was originally published on The Epoch Times and has been republished with permission.

It is known that Kwan Ying, Goddess of Mercy was an actual princess-queen. She held the West Coast region of Central America as a Chinese-Japanese ruler of an extended colony of Asia here ... in the times of Jesus. Such Chinese and Japanese migrations and colonies along the West Coast would be nothing new. Even Japanese colonists continue in the Peru area ... and up into modern times.

Having any number of inland colonies up and down the West Coast, using ancient Chinese writing would be considered natural. Colonies expand and explore the interior of islands and continents. And in ancient times, such frontier locations could have easily moved from the West Coast of Central America) into AZ and NM, having their rock inscriptions.

It is also readily known that many of the modern branches of Amerindians were actual refugees from the Spanish conquest of Central America in 1492 and later. Miwoks (San Francisco), Mohawks (northeast), Mohicans, Michigan, Mihouicans were all Mayans. Cherokee, Chirichuahua, Iriquois, Crow, Cree were from the city-state of Quiragua Mexico. Apache and so many others are modern migrations from Central America. All these came from the South and moved north along ancient trails as old as 400s and earlier. They didn't need to walk up the Pacific shoreline first, and then go inland.

In the times of King David, 1000s BC, his other concubine sons ... other than Bathsheba's sons Solomon and Nathan ... were moved from the Mideast into the America's West Coast line. Many of the noted West Coast Indian tribal names come from these sons. Nogah (Inca), Aleut, Inuit, Hopi, Navaho, and many more. Albeit they are considered Israelites, their mothers could be any racial ancestry. It is now more correctly known that "Bath Sheba" princess-queen daughter of Xbalba was Mayan Mihouican. So Israelite King David and Mexican wife had their bi-racial sons Solomon and Nathan, who stayed in the Mideast. So there is no problem for these concubine sons having pan-Asian ancestry, and they would provide the Asian appearance to these Pacific Northwest Indian tribes. And with Solomon having all of the international princesses, queens, and other high royal and noble females procreating a planetary dynasty of children for those regions - the Solomonic Fleet traversing the Indian and Pacific Oceans 1000s BC could have translocated and bred up any number of future royal dynasties on site - but also be moved into other areas for residency.

Having a Chinese bloodline into America would be nothing new with ancient migrations, civilizations, exploitation of areas for commerce, trade, and international expansionism.

There is every possible logical and reasonable validation for the author's impressions.

It is known that the Solomonic Fleet of the 1000s BC, that was previously the Egyptian Pharaoh's fleet give in dowry to Solomon, was already traversing the Indian and Pacific Oceans as far as Peru (biblical Ophir, gold of Ophir). Along the Pacific Northwest it is readily known that the Chinese have had fishing fleets and explorations up to the times of Chinese fleets fishing off Santa Monica harbor in the 1930s (photos shown were shocking !). It is known that the Chinese had failed sailings and shipwrecks along the Oregon and Washington coastline, with shoreline beeswax and stories of buried gold (Oregon) in the sand dunes. The Chinook tribe of Washington can be readily known to be a Chinese shipwreck, and the surviving sailors (et al) married into the local tribe.

It is being discovered that a portion of Mayan and Inca tribes, and those called the Apache were spread from the Russian Alaska down into Mexico. One period of time in the 400s CE, a group migrated up from Central America into the Pacific Northwest, chopped down trees, made ships, and sailed to the Siberian Steppes, and when arriving invaded the lands down into China (and India) as the Wu Hei (a Chinese pronunciation for Mihouican). If they were doing this, then there is no doubt that the clockwise Pacific current running from Asia to Alaska and down the West Coast could bring Chinese sailors into the Americas. Again, in another period of time, 1200s CE, another group of Central Americans again (!) moved up into the Pacific Northwest, chopped down trees, made ships, and sailed again into the Siberian Steppes, and appeared in full force, invading down into China, India, and across the Old World. They were the Monghols (Mayan cohols), the Golden Horde, the Yellow Plague. These events were before 1421, so there is no real hardship of any later expeditions to the Americas, when other migrations - and international trade (?) in iron, pottery, for fish, furs, etc could be bartered.

The discussion about possible very early Chinese exploration in the Americas is not convincing. The location of these glyphs far distant from the Pacific Ocean would lead one to believe that other glyphs much closer to, let's say, modern southern California or western Mexico, should have long since been found. None have! Yes, a so-called "anchor" supposedly from a Chinese ship was found off Santa Barbara, but even if true it would be far more recent than the New Mexico petroglyphs.

Ancient-Origins

This is the Ancient Origins team, and here is our mission: “To inspire open-minded learning about our past for the betterment of our future through the sharing of research, education, and knowledge”.

At Ancient Origins we believe that one of... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

Map Fuels Debate: Did Chinese Sail to New World First?

Tattered and rusty orange, a map recently unfurled in Beijing has reignited an international war of words over who reached the New World first.

China is the latest to throw its sailor hat into the ring, but it won't likely be the last in this long-running, hotly contested debate.

The Chinese voyage to America theory was popularized by British amateur historian Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book entitled " 1421: the Year China Discovered America ." The controversial, bestselling work claims that Chinese admiral Zheng He reached the Americas more than 70 years prior to Christopher Columbus' famous voyage.

After reading "1421," Liu Gang, a Chinese lawyer, realized the potential significance of a map he'd purchased for his private collection. Dated 1418 and clearly depicting the outlines of both North and South America, the map could be used to support Menzies' theory if it proves legitimate.

Liu unveiled his map at a packed press conference in Beijing on Jan. 16.

Despite arousing immediate international interest, the map was quickly dismissed by many historians as an outright forgery.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Scholars who know this field have refuted this claim under no uncertain terms," Sally K. Church, Fellow at the University of Cambridge, told LiveScience .

Geoff Wade, Senior Research Fellow at the University of Singapore's Asia Research Institute, echoed her sentiment. "The map is an 18th-century copy of a European map, as evidenced by the two hemispheres depicted, the continents shown and the non-maritime detailed [sic] depicted," he wrote recently to a group of maritime scholars.

In the other camp, Menzies is supporting Liu and the 1418 map with fervor. His key reasoning, forwarded by email from a member of his staff, is that "every continent, ocean, land, island, river shown on the 1418 map also appears on other Chinese maps of the same date or earlier. There is nothing new on the 1418 map—it simply combines everything on one sheet of paper," he said.

Menzies also points to a Portuguese map of the Americas dating from 1419 whose mistakes—like the drawing of California as an island—are thought to have been copied from cartographic errors made by the Chinese.

"In 1419 European voyages of exploration had not started. If the 1418 map is a forgery, then the 1419 map must be as well. How do you forge something yet to be discovered," Menzies reasoned.

British magazine The Economist recently printed an article about Liu's prized possession, quoting both supporters and detractors of Menzies' beliefs.

In a letter written to The Economist and provided to LiveScience , Wade, the critic of the map from the Asia Research Institute, urged its editor to print a retraction.

"That your writer has contributed to the Menzies' bandwagon and continuing deception of the public is saddening," Wade wrote. "The support mentioned all comes from Mr. Menzies' band of acolytes and the claims have no academic support whatsoever. Your writer has been taken in by Mr. Menzies and you do have a social responsibility to rectify this."

Other claims

The Chinese map controversy can be added to a growing database of claims for pre-Columbian discovery of the Americas.

According to some scholars, it was Scottish Earl Sir Henry Sinclair of Orkney who first touched American land in 1397, on one of many voyages the sailor undertook with Italian partner Nicolo Zeno. Another controversial map drawn by Zeno himself is thought to outline the coasts of Nova Scotia.

Supporters of this theory offer as evidence Sinclair's known contact with nearby Viking lords, whose ancestors unequivocally did reach North America centuries prior to any other Europeans—a feat that's often forgotten in the mix.

For now, a rewrite of the history books is unnecessary, according to Wade. "There is no need to rewrite anything except the history of 21st-century charlatans," he said.

Why do people feel like they're being watched, even when no one is there?

Why do babies rub their eyes when they're tired?

6G speeds hit 100 Gbps in new test — 500 times faster than average 5G cellphones

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 3 Scientists discover once-in-a-billion-year event — 2 lifeforms merging to create a new cell part

- 4 Quantum computing breakthrough could happen with just hundreds, not millions, of qubits using new error-correction system

- 5 DNA analysis spanning 9 generations of people reveals marriage practices of mysterious warrior culture

- 2 Tweak to Schrödinger's cat equation could unite Einstein's relativity and quantum mechanics, study hints

- 3 Plato's burial place finally revealed after AI deciphers ancient scroll carbonized in Mount Vesuvius eruption

- 4 Earth from space: Lava bleeds down iguana-infested volcano as it spits out toxic gas

- 5 Hundreds of black 'spiders' spotted in mysterious 'Inca City' on Mars in new satellite photos

The Seven Voyages of the Treasure Fleet

Zheng He and Ming China Rule the Indian Ocean, 1405-1433

Lars Plougmann/CC BY-SA 2.0/Flickr

- Figures & Events

- Southeast Asia

- Middle East

- Central Asia

- Asian Wars and Battles

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., History, Boston University

- J.D., University of Washington School of Law

- B.A., History, Western Washington University

Over a period of almost three decades in the early 15th century, Ming China sent out a fleet the likes of which the world had never seen. These enormous treasure junks were commanded by the great admiral, Zheng He . Together, Zheng He and his armada made seven epic voyages from the port at Nanjing to India , Arabia, and even East Africa.

The First Voyage

In 1403, the Yongle Emperor ordered the construction of a huge fleet of ships capable of travel around the Indian Ocean. He put his trusted retainer, the Muslim eunuch Zheng He, in charge of construction. On July 11, 1405, after an offering of prayers to the protective goddess of sailors, Tianfei, the fleet set out for India with the newly-named admiral Zheng He in command.

The Treasure Fleet's first international port of call was Vijaya, the capital of Champa, near modern-day Qui Nhon, Vietnam . From there, they went to the island of Java in what is now Indonesia, carefully avoiding the fleet of pirate Chen Zuyi. The fleet made further stops at Malacca, Semudera (Sumatra), and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

In Ceylon (now Sri Lanka ), Zheng He beat a hasty retreat when he realized that the local ruler was hostile. The Treasure Fleet next went to Calcutta (Calicut) on the west coast of India. Calcutta was one of the world's major trade depots at the time, and the Chinese likely spent some time exchanging gifts with the local rulers.

On the way back to China, laden with tribute and envoys, the Treasure Fleet confronted the pirate Chen Zuyi at Palembang, Indonesia. Chen Zuyi pretended to surrender to Zheng He, but turned upon the Treasure Fleet and tried to plunder it. Zheng He's forces attacked, killing more than 5,000 pirates, sinking ten of their ships and capturing seven more. Chen Zuyi and two of his top associates were captured and taken back to China. They were beheaded on October 2, 1407.

On their return to Ming China, Zheng He and his entire force of officers and sailors received monetary rewards from the Yongle Emperor. The emperor was very pleased with the tribute brought by the foreign emissaries, and with China's increased prestige in the eastern Indian Ocean basin.

The Second and Third Voyages