Cruise Tourism and Society pp 173–192 Cite as

The ‘Cruise Ship Railing Dance’: Conducting Academic Research in the Cruise Domain

- Alexis Papathanassis 4 ,

- Imke Matuszewski 5 &

- Paul Brejla 6

- First Online: 14 November 2012

2228 Accesses

1 Citations

Cruise-related research is regarded as interdisciplinary, pre-paradigmatic. As a research domain, cruises are characterised by high specificity and scarcity of available documented research. Thus, transferring methodological approaches from a variety of academic disciplines is inherently associated with epistemological risks and practical obstacles for cruise researchers. This paper synthesises research methodologies commonly applied in the cruise sector, ranging from conventional methods (hypothesis testing, case-studies, qualitative interviewing) to emerging, non-traditional approaches (e.g. web-based data analysis). Reflective accounts and examples are utilised in order to discuss their applicability and relevance in the chosen context. On this basis, requirements for cruise-adapted research methods are drafted and recommendations are made.

- Cruise Ship

- Tourism Research

- Average Sample Size

- Cruise Research

- Methodological Triangulation

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Akehurst, G. (2009). User generated content: The use of blogs for tourism organisations and tourism consumers. Service Business, 3 (1), 51–61.

Article Google Scholar

Alexa.com. (2011). CruiseCritic.com Site Info . Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/cruisecritic.com

Berger, A. A. (2006). Sixteen ways of looking at an ocean cruise: A cultural studies approach. In R. K. Dowling (Ed.), Cruise ship tourism (pp. 124–128). Oxfordshire: CAB International.

Chapter Google Scholar

Brownell, J. (2008). Leading on land and sea: Competencies and context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27 , 137–150.

Bulkeley, W. M. (2005). Marketers scan blogs for brand insights . Retrieved August 22, 2011, from http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB111948406207267049-qs710svEyTDy6Sj732kvSsSdl_A_20060623.html?mod=blogs

Burton, J., & Khammash, M. (2010). Why do people read reviews posted on consumer-opinion portals? Journal of Marketing Management, 26 (3–4), 230–255.

Carson, D. (2008). The ‘blogosphere’ as a market research tool for tourism destinations: A case study of Australia’s northern territory. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 14 (2), 111–119.

Cramer, E., Blanton, C., Blanton, L., Vaughan, G., Bopp, C., & Forney, D. (2006). Epidemiology of gastroenteritis on cruise ships, 2001–2004. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30 (3), 252–257.

Cruisecritic.com. (2011). CruiseCritic.com – about us . Retrieved March 14, 2011, from http://www.cruisecritic.com/aboutus/

Dale, C., & Robinson, N. (1999). Bermuda, tourism and the visiting cruise sector: Strategies for sustained growth. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 5 (4), 333–339.

Denscombe, M. (2003). The good research guide: For small-scale social research projects (2nd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Google Scholar

Dev, C. (2006). Carnival cruise lines: Charting a new brand course. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 47 (3), 301–308.

Douglas, N., & Douglas, N. (1997). P&O’s Pacific. Journal of Tourism Studies, 7 (2), 2–14.

Douglas, N., & Douglas, N. (2004). The cruise experience: Global and regional issues in cruising . Melbourne: Pearson Education.

Dreyfus, H. L. (2008). On the internet (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Dwyer, L., & Forsyth, P. (1996). Eonomic impacts of cruise tourism in Australia. Journal of Tourism Studies, 7 (2), 36–43.

Facca, F., & Lanzi, P. (2005). Mining interesting knowledge from weblogs: A survey. Data & Knowledge Engineering, 53 (3), 225–241.

Foster, G. (1986). South seas cruise – a case study of a short-lived society. Annals of Tourism Research, 13 , 215–238.

Gabe, T., Lynch, C., & McConnon, J. (2006). Likelihood of cruise ship passenger return to a visited port: The case of bar harbor, Maine. Journal of Travel Research, 44 , 281–287.

Gibson, P. (2006). Cruise operations management . Oxford: Elsevier.

Gibson, P. (2008). Cruising in the 21st century: Who works while others play? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27 , 42–52.

Hao, J., Li, S., & Chen, Z. (2010). Extracting service aspects from web reviews. In F.L.Wang, Z.Gong, X.Luo & Lei, J. (Eds), Web Information Systems and Mining, (pp.320–327). Heidelberg: Springer

Haythornthwaite, C., & Gruzd, A. (2007). A noun phrase analysis tool for mining online community conversations. Paper presented at the Communities and Technologies 2007, East Lansing, Michigan.

Hoffman, D. L., & Novak, T. P. (1996). Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing, 60 (3), 50–68.

Hung, K., & Petrick, J. F. (2010). Developing a measurement scale for constraints to cruising. Annals of Tourism Research, 37 (1), 206–228.

Hung, K., & Petrick, J. F. (2011). Why do you cruise? Exploring the motivations for taking cruise holidays, and the construction of a cruising motivation scale. Tourism Management, 32 (2), 386–393.

Illum, S., Ivanov, S., & Liang, Y. (2010). Using virtual communities in tourism research. Tourism Management, 31 (3), 335–340.

Jaakson, R. (2004). Beyond the tourist bubble? Cruiseship passengers in port. Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (1), 44–60.

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31 (2), 386–408.

Jones, R. (2007). Chemical contamination of a coral reef by the grounding of a cruise ship in Bermuda. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 54 , 905–911.

Klein, R. A. (2002). Cruise ship blues: The underside of the cruise industry . Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

Klein, R. A. (2005). Cruise ship squeeze: The new pirates of the seven seas . Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

Litvin, S., Goldsmith, R., & Pan, B. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Management, 29 (3), 458–468.

Lukas, W. (2009). Leadership: Short-term, Intercultural and Performance-oriented. In A. Papathanassis (Ed.), Cruise sector growth: Managing emerging markets, human resources, processes and systems (pp. 65–78). Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Manning, C. D., Raghavan, P., & Schütze, H. (2009). An introduction to information retrieval . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marti, B. (1992). Passenger perceptions of cruise itineraries – A royal viking line case study. Marine Policy, 360-370.

Marti, B. (2004). Trends in world and extended-length cruising (1985–2002). Marine Policy, 28 , 199–211.

Miller, A., & Grazer, W. (2002). The North American cruise market and Australian tourism. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 8 (3), 221–234.

Miller, J., Tam, T., Maloney, S., Fukuda, K., Cox, N., Hockin, J., et al. (2000). Cruise ships: High-risk passengers and the global spread of new influenza viruses. Clinical Infectious Deseases, 31 , 433–438.

Moscardo, G., Morrison, A. M., Cai, L., Nadkami, N., & O’Leary, J. T. (1996). Tourist perspectives on cruising: Multidimensional scaling analyses of cruising and other holiday types. Journal of Tourism Studies, 7 (2), 52–63.

Olsen, W. K. (2004). Triangulation in social research: Qualitative and quantitative methods can really be mixed. In M. Holborn & M. Haralambos (Eds.), Developments in sociology (pp. 1–30). Ormskirk, Lancashire: Causeway Press.

Papathanassis, A., & Beckmann, I. (2011). Assessing the ‘poverty of cruise theory’ hypothesis. Annals of Tourism Research, 38 (1), 153–174.

Petrick, J. F. (2003). Measuring passengers’ perceived value. Tourism Analysis, 7 , 251–258.

Petrick, J. F. (2004). Are loyal visitors desired visitors? Tourism Management, 25 (4), 463–470.

Petrick, J. F., & Sirakaya, E. (2003). Segmenting cruisers by loyalty. Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (2), 472–475.

Petrick, J. F., Tonner, C., & Quinn, C. (2006). The utilization of critical incident technique to examine cruise passengers’ repurchase intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 44 , 273–280.

Porter, M. E. (2001). Strategy and the internet. Harvard Business Review, 79 (3), 62–78.

Pullman, M. (2005). Let me count the words: Quantifying open-ended interactions with guests. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 46 (3), 323–343.

Russell, M. A. (2011). Mining the social web . Sebastopol: O’Reilly.

Sayer, A. (1992). Method in social science: A realist approach . London: Routledge.

Scrapy Development Team. (2011 ). Scrapy at a glance – Scrapy v0.10.4 documentation . Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http://doc.scrapy.org/0.10/intro/overview.html

Sirakaya, E., Petrick, J., & Choi, H.-S. (2004). The role of mood on tourism product evaluations. Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (3), 517–539.

Smith, T. (2009). Conference notes – the social media revolution. International Journal of Market Research, 51 (4), 559–561.

Stewart, E. J., Kirby, V. K., & Steel, G. D. (2006). Perceptions of Antarctic tourism: A question of tolerance. Journal of Landscape Research, 31 (3), 193–214.

Szarycz, G. (2008). Cruising, freighter-style: A phenomenological exploration of tourist recollections of a passenger freighter travel experience. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10 , 259–269.

Testa, M. (2004). Cultural similarity and service leadership: A look at the cruise industry. Managing Service Quality, 14 (5), 402–413.

Thompson, E. (2002). Engineered corporate culture on a cruise ship. Sociological Focus, 35 (4), 331–344.

Thompson, E. A. (2004). An orderly mess: The use of mess areas in identity shaping of cruise ship workers. Sociological Imagination, 40 (1), 15–29.

Toh, R., Rivers, M., & Ling, T. (2005). Room occupancies: Cruise lines out-do the hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 24 , 121–135.

Teye, V., & Leclerc, D. (1998). Product and service delivery satisfaction among North American cruise passengers. Tourism Management, 19(2), 153–160.

Tracy, S. (2000). Becoming a character for commerce: Emotion labor, selfsubordination, and discursive construction of identity in a total institution. Management Communication Quarterly, 14 (1), 90–128.

Weaver, A. (2005). The McDonaldization thesis and cruise tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (2), 346–366.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bremerhaven University of Applied Sciences, An der Karlstadt 8, Bremerhaven, 27568, Germany

Alexis Papathanassis

Teesside University Business School, Teesside, UK

Imke Matuszewski

Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Paul Brejla

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alexis Papathanassis .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

, Cruise Tourism Management, Bremerhaven University of Applied Scienc, An der Karlstadt 8, Bremerhaven, 27568, Germany

University of Dubrovnik, Branitelja Dubrovnika 29, Dubrovnik, 20000, Croatia

Tihomir Lukovic

of Applied Sciences, Bremerhaven University, An der Karlstadt 8, Bremerhaven, 27568, Germany

Michael Vogel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Papathanassis, A., Matuszewski, I., Brejla, P. (2012). The ‘Cruise Ship Railing Dance’: Conducting Academic Research in the Cruise Domain. In: Papathanassis, A., Lukovic, T., Vogel, M. (eds) Cruise Tourism and Society. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32992-0_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32992-0_13

Published : 14 November 2012

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-642-32991-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-642-32992-0

eBook Packages : Business and Economics Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, international cruise research advances and hotspots: based on literature big data.

- 1 School of Economics and Management, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, China

- 2 Innovation Center on Climate and Meteorological Disasters, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing, China

This paper makes a systematic visual analysis of cruise research literature collected in science network database from 1996 to 2019. The results show that: the overall number of published literatures on cruise research are growing; North American states, Europe, and Asia are the main regions of cruise research. The evolutionary of theme development of cruise research has three stages, and the current hot topics of cruise research can be summarized as cruise tourism, luxury cruises, cruise passengers, destination ports, environmental and biological conservation, and cruise diseases. Future research in the cruise field is in the areas of cruise supply chain, technology in cruise, children’s cruise experience, itinerary design, planning and optimization, brand reputation and luxury cruises, public transportation in destinations, environmental responsibility of passengers and corporate social responsibility, optimization of energy systems, climate change in relation to the cruise industry, the Chinese cruise market and risk management of cruise diseases.

1 Introduction

As the fastest growing sector of the global tourism industry, Cruise tourism has drawn extensive attention. Over the past 40 years, although the global economy has experienced many economic recessions and fluctuations triggered by various factors, the number of cruise passengers has maintained an average growth of about 7%. According to data provided by the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), the number of passengers carried by the cruise industry has increased 9.9 million in 2001 to 28.5 million in 2018 ( China.com, C, 2019 ; Hong, 2019 ). The cruise industry plays an important role in the global economy, creating 1,177,000 jobs, sending out $50.024 billion in payroll and generating $150 billion in global revenue in 2018 ( China.com, C, 2019 ).

In 2020, the wide-spread of the novel coronavirus has resulted in the loss of about 1.1 billion international tourists, a drop in export earnings of between $91 billion and $1.1 trillion and the loss of between 100 million and 120 million jobs ( Personal and Archive, 2020 ). Although the novel coronavirus pneumonia has caused the global cruise market to temporarily suspend, it has not changed the long-term upward trend of the global cruise market. The Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) is optimistic about the prospects of the cruise tourism market. It predicts that the global cruise market will reach 37.6 million in 2025, with good development prospects and market potential ( Hong, 2020 ).

In terms of specific destinations, the Caribbean and the Mediterranean are still the two most popular cruise destinations in the world ( Wondirad, 2019 ). On the other hand, Asia, Australasia and the Pacific are the fastest growing cruise destinations in the world ( Wondirad, 2019 ). In recent years, the cruise tourism industry has shown extraordinary growth, and gradually become popular among Asian tourists ( Chen, 2016 ). Due to its rich tourism resources and huge potential tourism market, cruise tourism has gained rapid development momentum in Asia ( Ma et al., 2018 ). The direct economic contribution of cruise industry to Asian economy reached 3.23 billion US dollars ( Wondirad, 2019 ). Nevertheless, this rapid growth has been tested by huge challenges such as infrastructure constraints, lack of expertise, inadequate marine expertise, insufficient government commitment and environmental sustainability issues ( Sun et al., 2014 ; Ma et al., 2018 ).

The cruise industry involves a wide range of sectors and industries, including manufacturing, tourism, finance, commerce, shipping and logistics, and is connected by cruise routes and ports to form a vast regional and global network economy, a process that has far-reaching social, economic and environmental impacts on both source and destination regions ( Vega-Muñoz et al., 2020 ). Cruise research has developed a diverse range of research centers from various levels and perspectives. A review of the research literature in the cruise field reveals that, for the time being, no scholars have conducted systematic bibliometric research on the cruise field as a whole.

To this end, this study aims to comprehensively analyze the global references related to cruise research in the WOS database from 1996 to 2019. Specifically, this systematic review study intends to:

1) Examine the research trends in the field of cruise ships;

2) Analyze the pre-existing knowledge according to the research background of the literature, the author, the organization and the country to which it belongs;

3) Explore the leading cruise research topics in the past 24 years;

4) On the basis of literature analysis in the past 24 years, discuss future research trends in the cruise field, and provide reference for in-depth research.

2 Data sources and methodology

2.1 data sources.

The source of literature data is Web of Science Core Collection. The WOS Core Collection is a collection of authoritative and influential academic journals from around the world, covering a wide range of disciplines, and is characterized by high quality, large quantity and time span, and complete documentation ( Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2020 ). The data retrieval is carried out by using the fields of “TI = cruise ship* \cruise* \cruise line*, etc. and TS = cruise ship* \cruise* \cruise line*, etc.” In order to ensure the representativeness of documents, “Document Types = ARTICLE OR REVIEW” is set to refine and articles unrelated to cruise research and whose authors are unknown are removed. After that, 437 valid documents between 1996 and 2019 are obtained. The above search was conducted before January 1, 2020.

2.2 Methodology

CiteSpaces is a widely used tool in bibliometric research. It is written by a java program developed by Dr. Meichao Chen ( Chen, 2006 ) to generate a visual knowledge graph composed of different lines and nodes, such as countries, organizations, authors, cited authors, and keywords. The CiteSpace software requires the setting of relevant queues before the data can be visually analyzed. In this study, the time span is set to 1996-2019, the time division is set to one year, the data extraction object is selected as Top50, and the other options remain in the default state. Citations, countries, authors, institutions, keywords and other options are selected to perform bibliometric visualization analysis.

3 Statistical results of cruise research literature

3.1 trend of the number of publications.

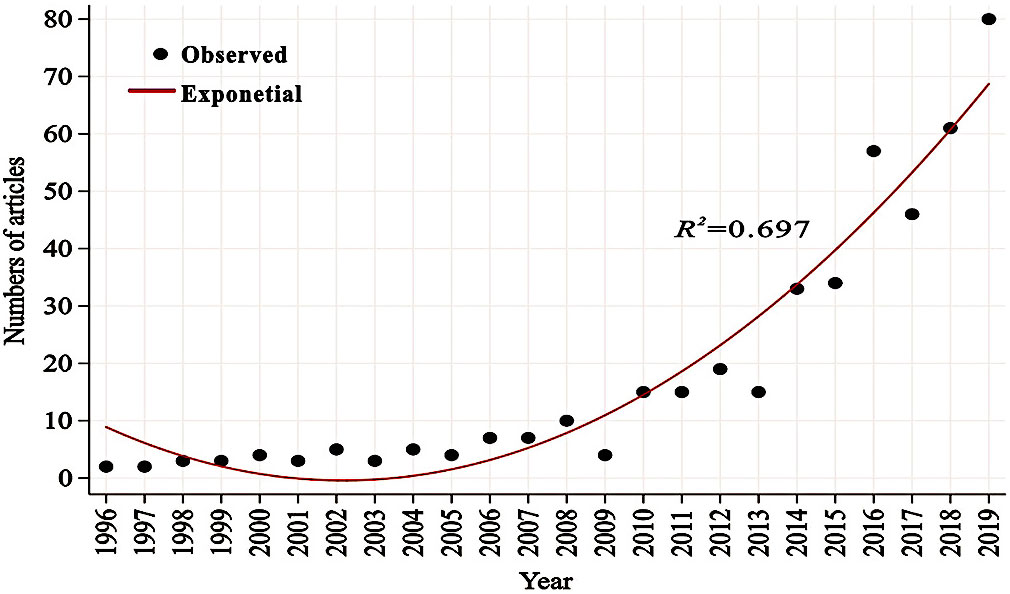

Figure 1 shows the regression model of the number of articles published from 1996 to 2019 established by using STATA software. It can be seen from the model that the number of articles published in the cruise field has increased significantly, and the time series of articles published in WOS has been adjusted by 69.7%. As can be seen from the scatter on the graph, there is a reasonable fluctuation with an upward trend in the number of publications. The fitted trend line shows that the growth in the literature was at a low level from 1996 to 2004, with an annual average of less than four articles; the number of publications grew slowly from 2005 to 2012, with an annual average of nearly 11 articles; and grew rapidly from 2013 to 2019, with an annual average of nearly 47 articles.

Figure 1 The number of articles in international cruise research published in 1996-2019.

3.2 Analysis of countries and organizations

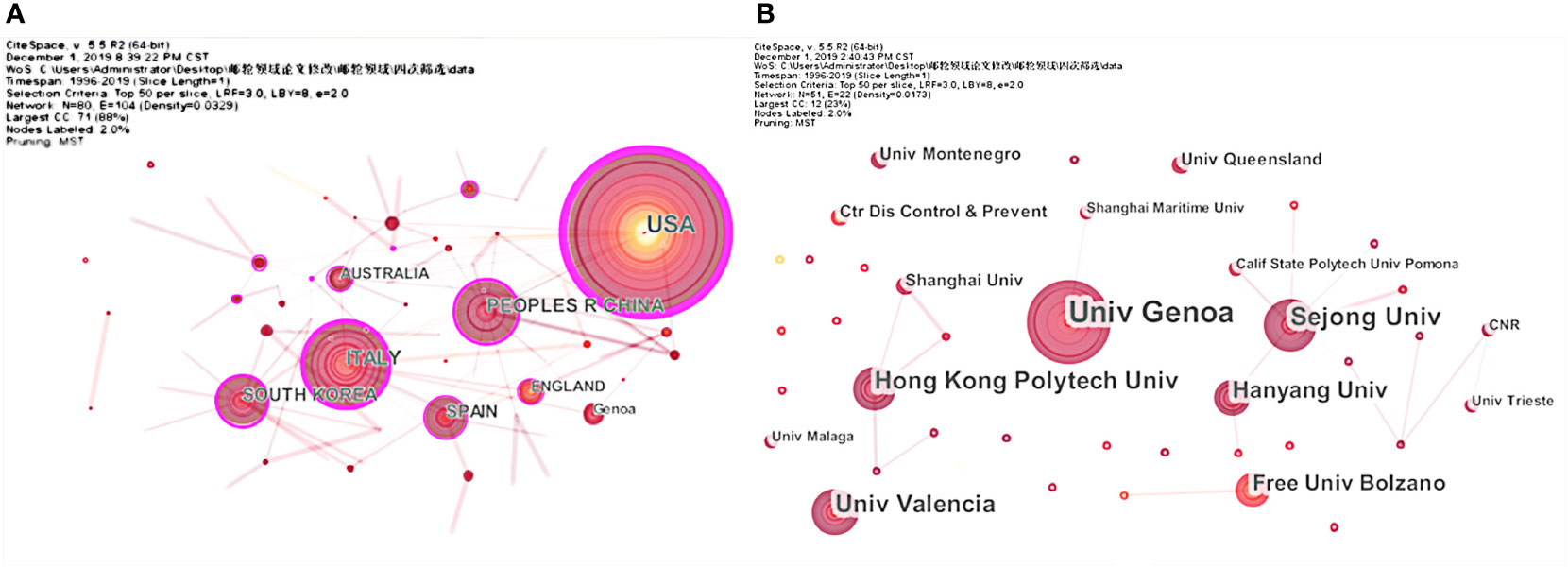

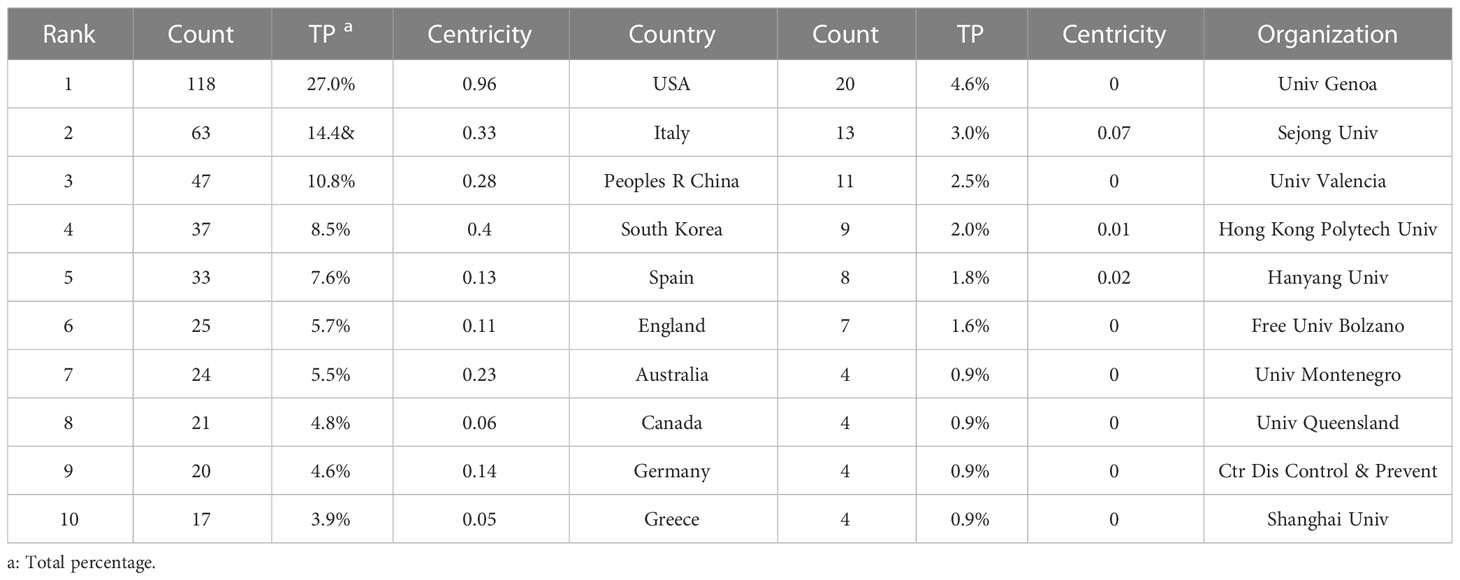

The network map of the co-author’s country/region contains 80 nodes and 104 lines ( Figure 2A ). A total of 437 articles were published in 80 countries/regions from 1996 to 2019, with contributions ranging from 118 articles (27.0%) to 1 article (0.2%). The United States not only has a high volume of publications (27.0%), but also a high centrality (0.96). This indicates that the US maintains extensive collaborations with many countries (such as China, Italy, Spain) and American researchers have achieved some significant achievements and made important contributions to the field. Both Italy and China have higher publication volumes than Korea, but both have lower centrality than Korea. The volume of publications is not positively correlated with centrality in most countries. According to the centrality, Canada and Greece should strengthen international academic cooperation with other countries.

Figure 2 A visual map of countries/organizations in the cruise research: (A) the main countries in the cruise research; (B) the organizations in the cruise research.

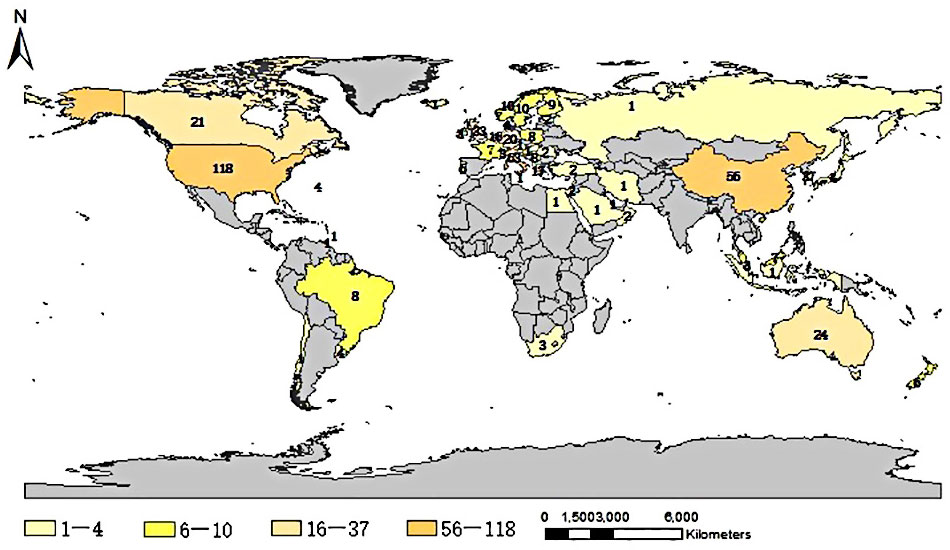

As far as the regional distribution of research publications is concerned ( Figure 3 ), the countries to which the published literature belongs are mainly concentrated in Europe, and the countries with more publications are concentrated in North America and Asia, which is consistent with the market phenomenon of the global cruise industry. The global cruise market is mainly concentrated in the Caribbean, Asia & Pacific, Mediterranean, Northern Europe, Western Europe, Australia, Alaska and other regions, with these six regions accounting for 85% of the market share. According to the intercontinental division, the six regions can be divided into North America, Europe, Asia and other regions ( Hong, 2019 ; Vega-Muñoz et al., 2020 ).

Figure 3 Global cruise research productivity contribution.

Creating and analysing a knowledge map of an organization’s network not only provides valuable information, but also helps organizations to build and develop collaborative relationships.

The following organizations have made important contributions to the research in the entire field: University of Genoa (20 articles), University of Sejong (13 articles), and University of Valencia (11 articles). From Table 1 , we can see that the centrality of these organizations is low. From Figure 2B , it can be seen that there are only four sub-networks in the cooperation network of research organizations, with a low network density, a loose overall structure and a high cooperation degree gap. The largest collaborative network is made up of 12 research organizations, including Sejong University and Hanyang University. Of these, Sejong University (Centricity = 0.07) is the organization with the highest network centrality, which has promoted academic cooperation in this field and has become the main force in promoting the development of cruise research.

Table 1 Top ten countries and organizations in cruise research.

3.3 Analysis of author collaboration networks and author co-citation networks

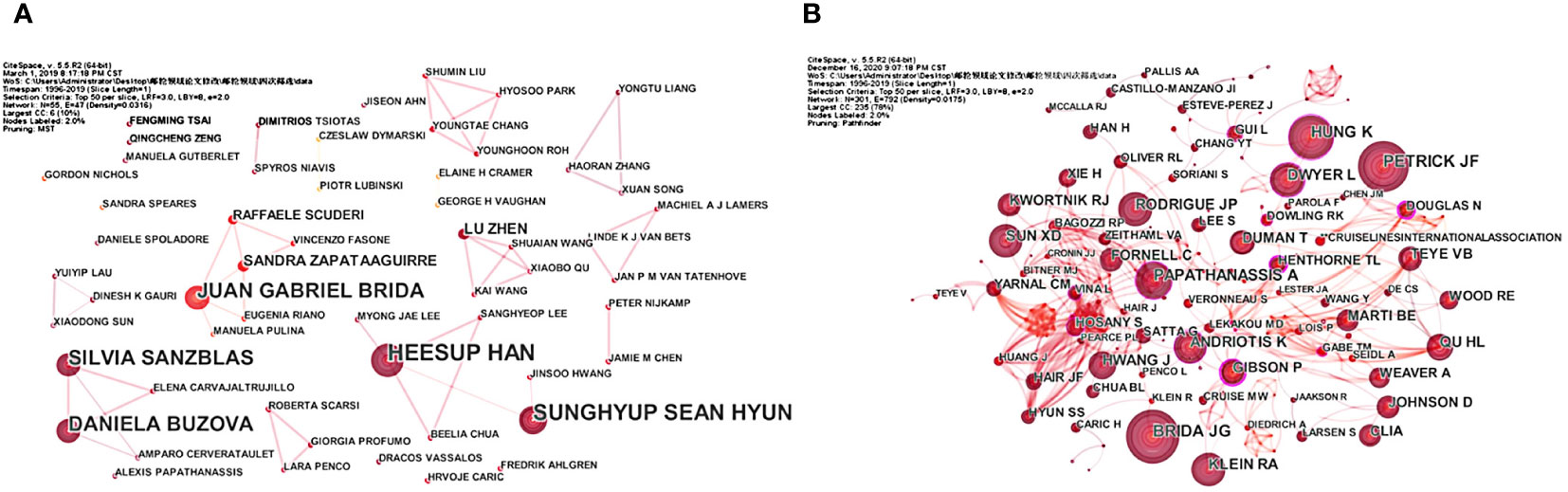

Figure 4A vividly maps the author’s collaboration network in cruise research. The authors who excelled in terms of publications are Heesup Han (11 articles), Sunghyup Sean Hyun (10 articles), Silvia Sanzblas (8 articles), Daniela Buzova (8 articles) and Juan Gabriel Brida (8 articles), whose tireless efforts have contributed to the depth of cruise research. The author collaborative network consists of 13 collaborative groups. Among them, the two largest collaborative networks is a sub-network with 6 people including Heesup Han and a sub-network of 6 people including Juan Gabriel Brida, while the other collaborative relationships are mostly composed of 2-4 people.

Figure 4 Visualization of authors in cruise research: (A) Collaborative network of lead authors in cruise research; (B) Cited authors in cruise research.

Although there are multiple collaborative networks, the nodes do not have a purple outer circle, which indicates that these authors have low centrality and lack extensive collaboration with other scholars.

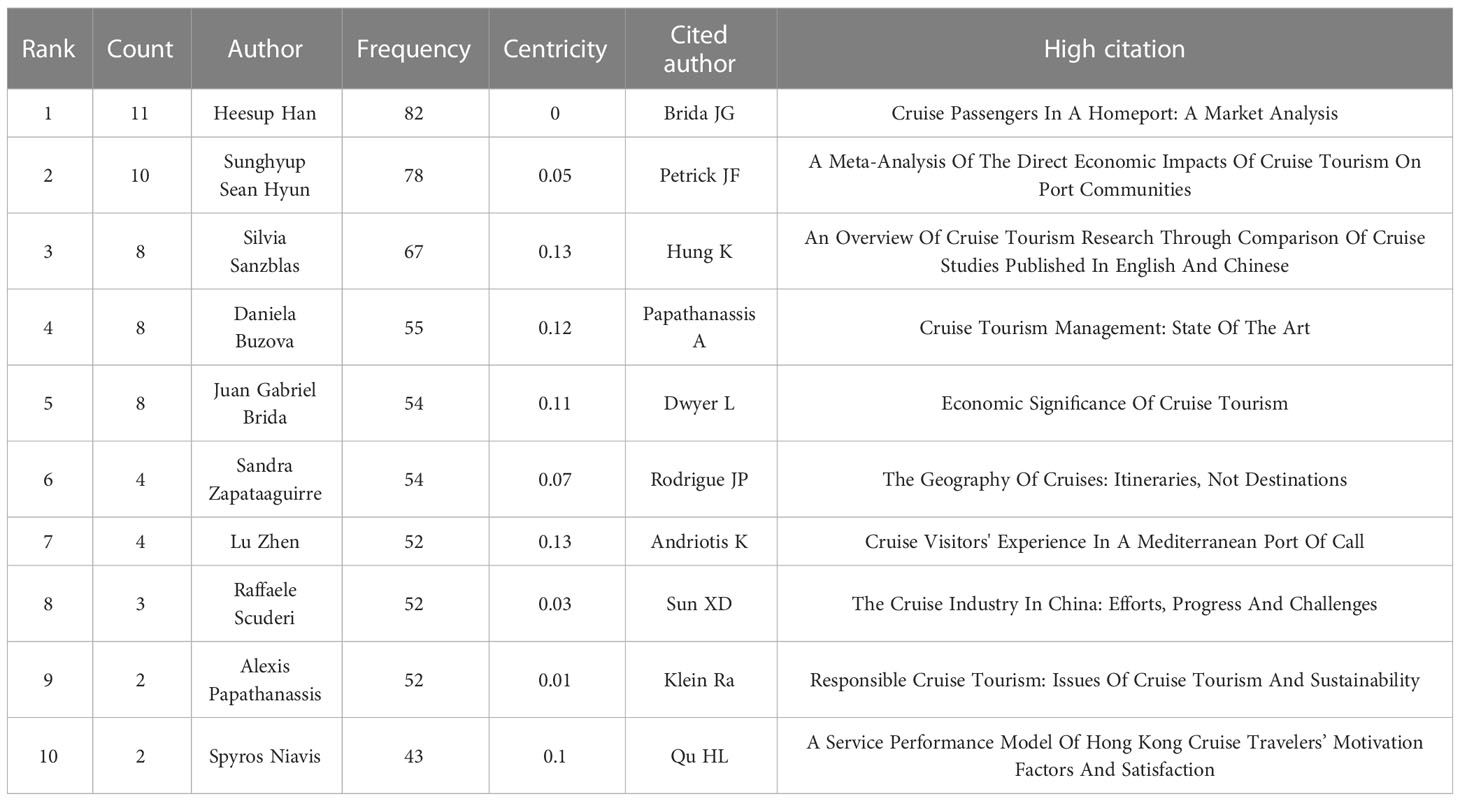

Table 2 summarizes the top 10 most cited authors. The larger nodes in Figure 4B have fewer peripheral links, indicating that the number of publications by cited authors is not proportional to centrality. Based on 437 articles, it is easy to find that the author who is widely cited by other scholars in this field is Brida JG, he applied three-step multivariable market segmentation analysis to study the characteristics and preferences of cruise passengers and the overall experience of passengers at the port of call, providing a reference for local managers to formulate policies ( Brida et al., 2013 ). The second author, Petrick JF, conducted a meta-analysis of the direct economic impact of cruise tourism, with significant positive coefficients between the direct economic impact and: number of passengers, number of crew, number of cruise lines, expenditure per passenger, and expenditure per cruise line. It was further found that cruise lines have a significant mediating effect on expenditure per passenger and per crew member in port destinations. Compared with the North American market, the direct economic impact of cruise tourism on the Caribbean market and other emerging market ports is significantly lower ( Chen et al., 2019 ). The third author, Hung K, explores the differences between Chinese and British cruise tourism literature by reviewing 62 articles published in top English-language tourism and hospitality journals and 26 articles in leading Chinese journals, and discusses important research themes, methodological trends and future research fields ( Hung et al., 2019 ). Most of the inner circles of these authors are from orange to dark red, indicating the rapid increase in citations of these authors in recent years. Their articles are more likely to provide ideas for some basic research and to guide scholars in establishing new perspectives on cruise research.

Table 2 Top ten authors, cited authors and his high-frequency citations.

4 Content level dimension analysis of cruise research

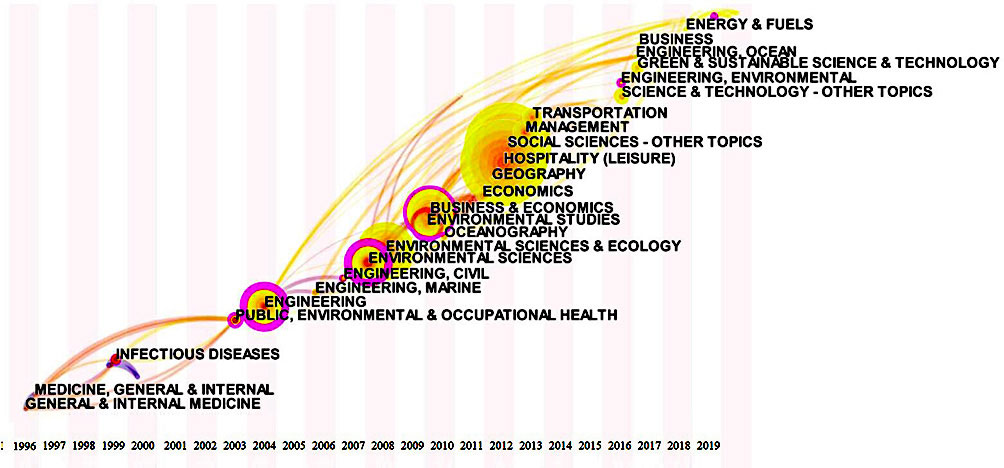

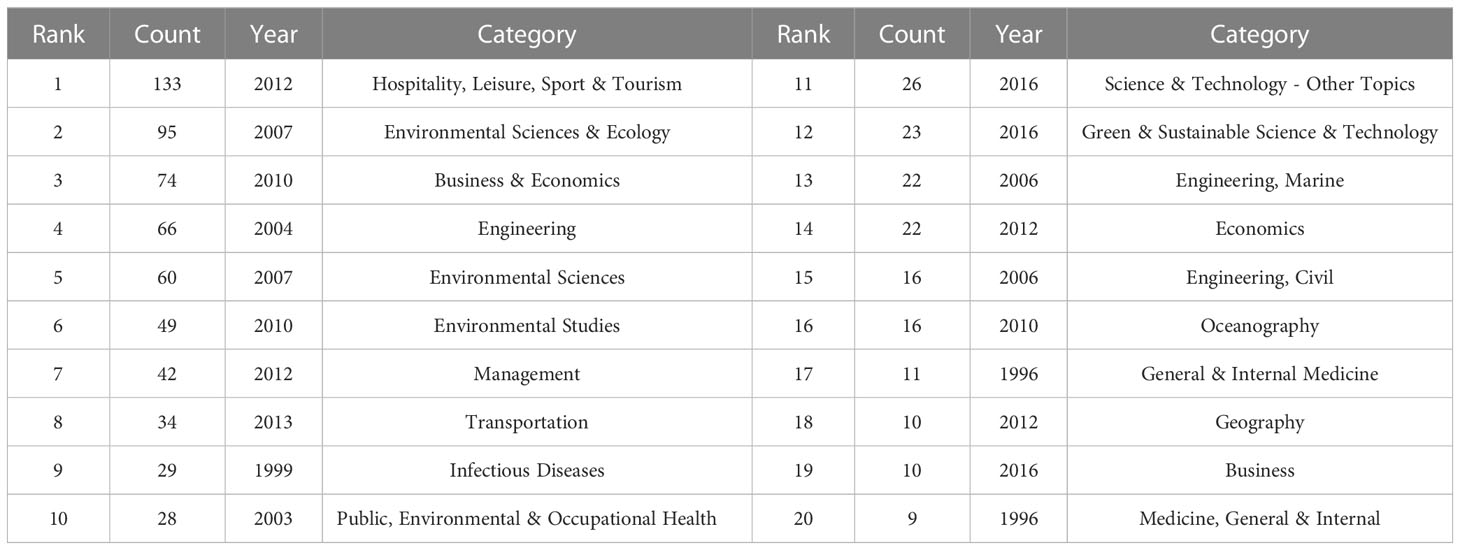

4.1 analysis of disciplines in cruise research.

Figure 5 is a time zone view of the cruise research disciplines from 1996 to 2019, involving 47 disciplines. hospitality, leisure, sport & tourism, environmental science & ecology, business & economics, engineering, environmental sciences and environmental studies are the main disciplines of cruise research, accounting for 47% of the total. The year of the discipline in Table 3 indicates the time of the first concentration. As can be seen from Table 3 and Figure 5 , Medicine, general & internal and infectious diseases were the basic disciplines in the early stage of cruise research. In recent years, cruise research has begun to involve marine engineering, environmental engineering, green & sustainable technology, energy & fuels, etc., which may be emerging disciplines for future research.

Figure 5 Time zone view of the cruise field disciplines. Purple means the node has good centrality; the time demonstration from 1996 to 2019 is represented by a blue to yellow gradient.

Table 3 Top 20 disciplines in cruise research.

4.2 Analysis of references

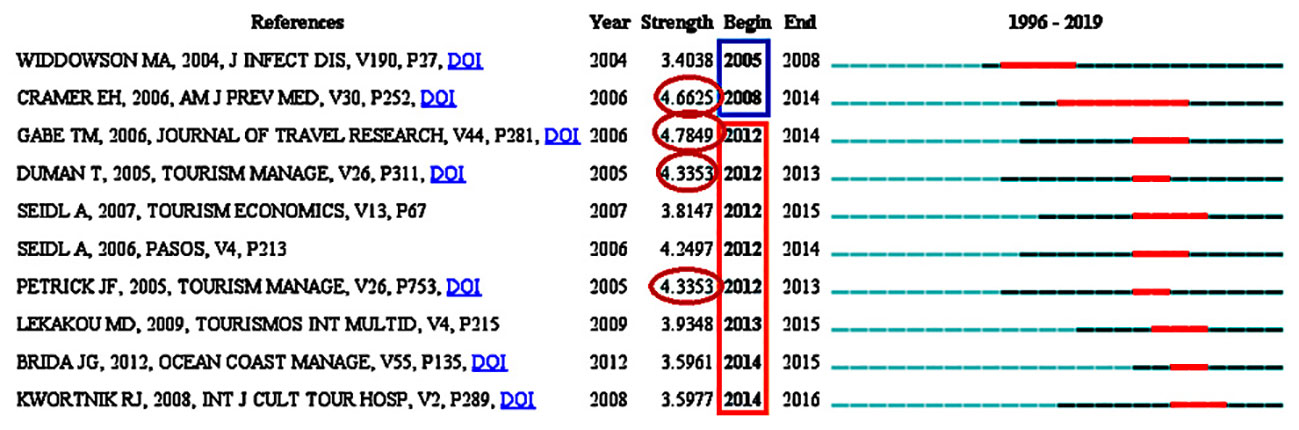

Burst detection is an effective analysis tool that can be used to detect emergencies or important information within a specific period of time. Figure 6 shows the top 10 strongest citations detected by CiteSpace from 1996 to 2019.

Figure 6 The ten most cited references in cruise research. The blue indicates the time interval, the red indicates the time period when the document is cited.

In terms of time, the first two references highlight emerging trends in cruise research in 2005 and 2008, and the remaining references highlight emerging trends in cruise research from 2012 to 2014. In 2005 and 2008, the most noticeable burst intensity of 4.6625 was written by Cramer EH. The outbreak started in 2008 and ended in 2014. This article assessed the correlation between the incidence of gastroenteritis on cruise ships and its outbreak frequency, and found that environmental programs cannot adequately predict or prevent common risk factors and the transmission of diseases between people ( Cramer et al., 2006 ).

The three most cited strong citation burst intensities from 2012 to 2014 include Gabe TM (4.7849), Duman T (4.3353) and Petrick JF (4.3353). The subjects of the three literatures are cruise passengers, and they study the factors that affect the intention of cruise passengers to revisit the port community ( Gabe et al., 2006 ); they segment the market based on the price sensitivity of cruise passengers to determine whether a price-sensitive market is needed ( Petrick, 2005 ); In the context of the cruise vacation experience, they study the role of passengers’ emotional factors (i.e. enjoyment, control and novelty) on value and the role of customer satisfaction in emotional value relationships ( Duman and Mattila, 2005 ).

Overall, of the 10 references cited between 2005 and 2016, the longest citation time is 7 years, and the shortest is 2 years. However, there are no new strong citations on cruise research from 2017 to 2019.

5 Analysis of hot spots and their evolution in cruise research

5.1 analysis of hot spots in cruise research.

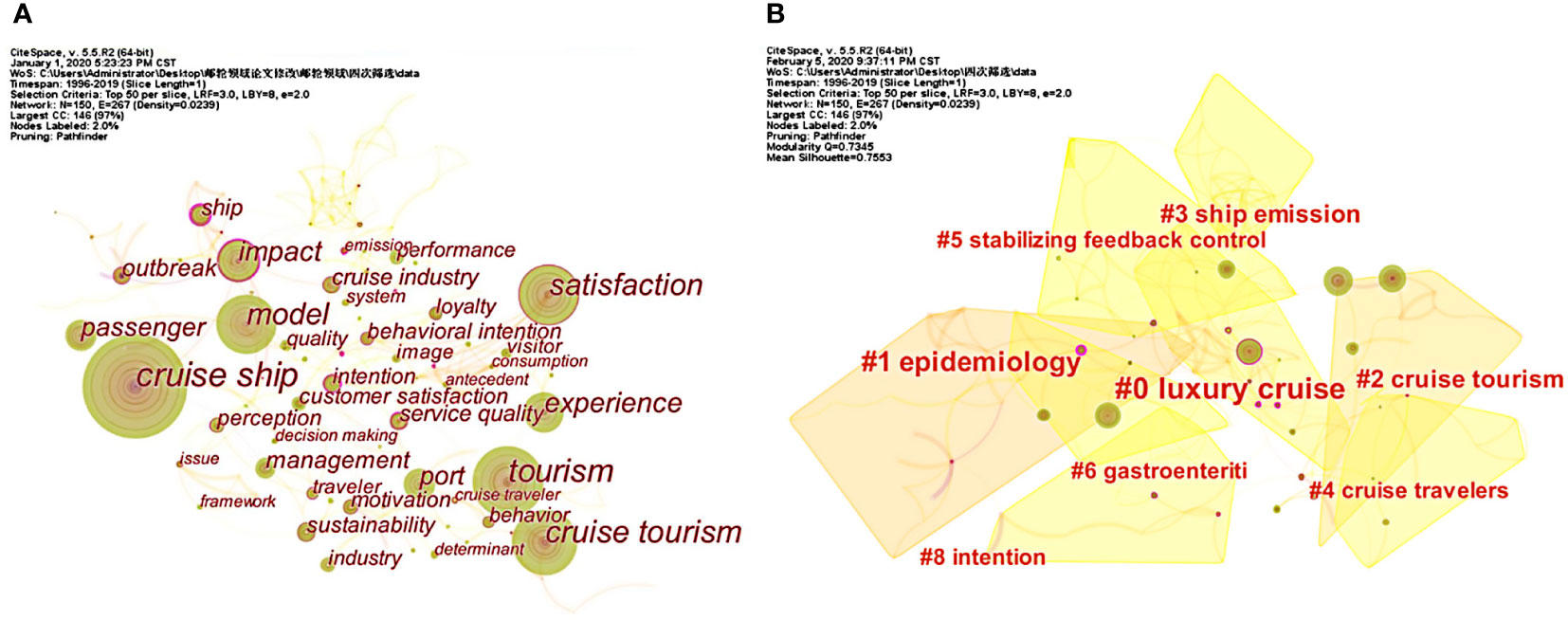

Since keywords are an accurate summary of the literature, analyzing high-frequency keywords can directly reflect the subject content and topical issues in the academic field. The bibliometric data shows that a total of 150 thematic keywords were covered in the cruise research. As shown in Figure 7A , the keywords with a high frequency are cruise ship, tourism, cruise tourism, satisfaction, model, impact, experience and port. The keywords with high centrality are ship, emission and intention.

Figure 7 A visual map of keywords in cruise research: (A) the main keywords in cruise research; (B) the cluster map of keywords.

In order to more clearly reflect the branch composition of cruise research, a cluster analysis of subject terms was performed, and the cluster view was selected on the basis of the original operation to form 8 clusters ( Figure 7B ). The Q = 0.7345 and S = 0.7553 of this cluster indicate that this cluster is significant and convincing.

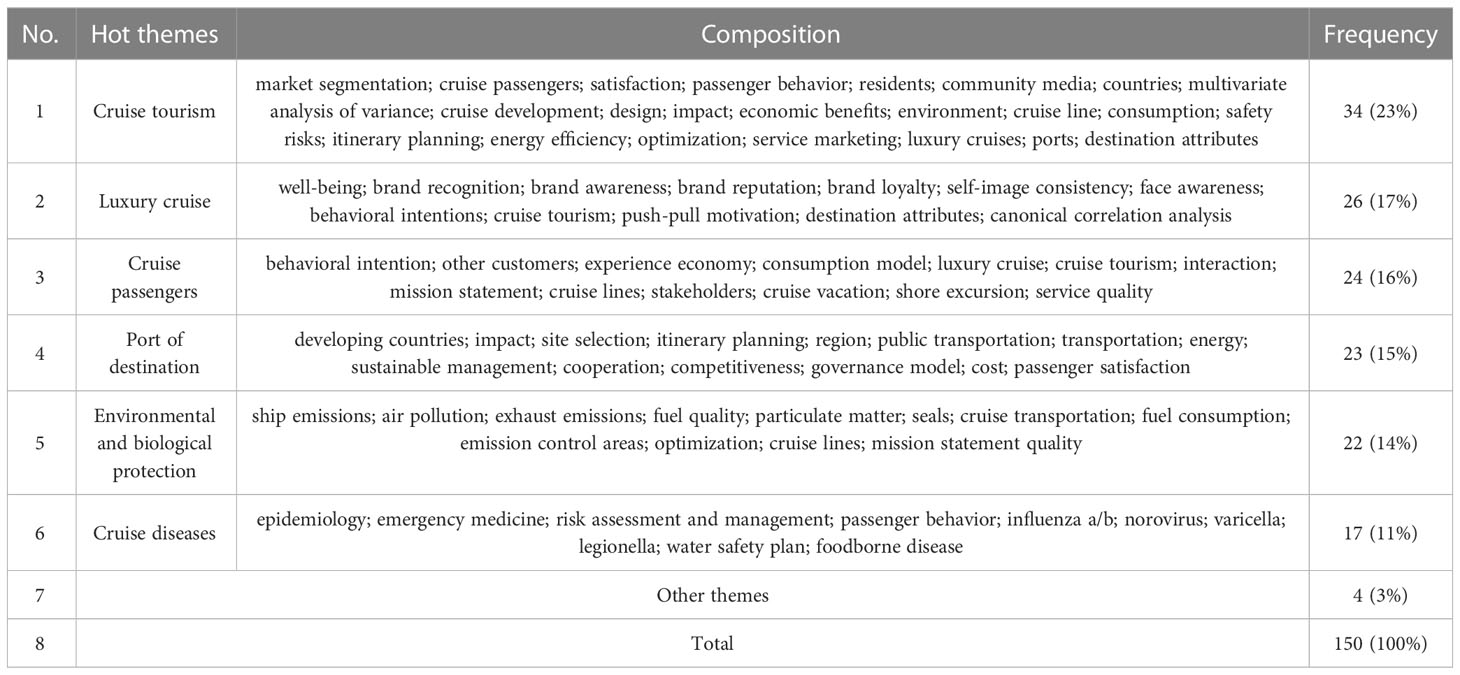

Based on the above statistical analysis and the relevant literature, the hot topics of cruise research are classified into the following categories ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 Hot topics in cruise research.

5.1.1 Cruise tourism

The wide range of possibilities in music tourism, party tourism, hotel management and local city tourism and etc. form a comprehensive sailing experience ( Hefner et al., 2014 ; Cashman, 2016 ; Paananen and Minoia, 2019 ). Cruise tourism is one of those tourism phenomena that has experienced significant growth but has not attracted much attention, a claim supported by the growing turnover, the number of passengers, the number of ships or ports in operation and the number of countries in operation ( Vega-Muñoz et al., 2020 ). Cruise tourism has a double impact on the economy of the destination. On the one hand, the direct impact is generated by passengers, crew activities and land-based consumer spending, as well as revenues received by cruise lines and local suppliers that provide services to ports and ships ( Chua et al., 2015 ). On the other hand, the indirect impact is the income generated by the increase in consumption within the scope of the tourism economy that is caused by the purchase of consumables and services from local suppliers and the increase in income generated from cruise tourism activities ( Castillo-Manzano et al., 2015 ). In addition, there are also positive and negative impacts on local communities. Although theoretically increasing employment has led to income growth, little evidence of improvement has been found. On the contrary, cruise tourism has had a significant negative impact on the local environment, and local residents have also suffered from a large number of tourists invaded, and tourists often do not respect local customs, traditions and beliefs ( MacNeill and Wozniak, 2018 ). Cruise tourism can also be studied in terms of the environmental impact of the increasing number and scale of ships, destination ports and cruise passengers, which are covered in the following themes due to cross-cutting and overlapping content.

5.1.2 Luxury cruises

With huge growth potential, luxury cruises are considered to be one of the most promising target markets. Factors such as perception of crowding, food quality, service quality and cabin quality have an impact on brand prestige, which in turn affects customer perception of well-being, brand recognition and loyalty ( Hwang and Han, 2014 ; Hyun and Kim, 2015 ). In the brand community, the cruise brand, cruise products and the relationship with other cruise ships have a positive impact on the uniqueness of the brand ( Shim et al., 2017 ). Brand tribalism has a positive effect on the formation of passengers’ perceived consumer power, passengers’ perception of consumer power influences their engagement, and engagement has a moderating effect on passengers’ satisfaction, loyalty and perceived happiness ( Han and Hyun, 2018 ; Lee and Kim, 2019 ). Satisfaction, loyalty, and the “conspicuousness” of product use affect travelers’ purchase behavior of products, and happiness perception affects travelers’ willingness to pay for price premiums ( Han et al., 2018 ; Yu, 2019 ).

5.1.3 Cruise passengers

The pleasure that cruise travel brings to cruise passengers is created primarily through emotional and relational experiences in the short term, with much of the long-term impact coming from the experience of thinking ( Lyu et al., 2018 ). The difference of passenger culture is reflected in behavioral intention, satisfaction, emotional value, service quality, and etc. ( Sanz Blas and Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014 ; Forgas-Coll et al., 2016 ; Li and Fairley, 2018 ). It is necessary for cruise lines or destination ports to reduce the gap between marketing and actual experience in order to increase passenger arrivals and increase revenue. Studying the relationship between elements such as passenger satisfaction, loyalty, and behavioral intentions, factors influencing the decision-making process, the volume and structure of passenger expenditures, and factors influencing willingness to pay ( Sanz Blas and Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014 ; Chua et al., 2015 ; Chen et al., 2016 ; Lee et al., 2017 ; Bahja et al., 2019 ), and thus segmenting the market according to elements such as nationality, gender, age, satisfaction, perceptions of safety, and consumption patterns ( Brida et al., 2013 ), can help planners and managers increase the likelihood of repeat visits and positive word-of-mouth. The design of the ship, the quality of the guide service and the design of the land excursions also affect the passenger experience ( Oklevik et al., 2018 ; Dai et al., 2019 ; Buzova et al., 2019b ). In addition, attitudes towards cruise travel are gradually shifting by age, with Gen Xers and Millennials becoming more optimistic about cruise travel ( Wang et al., 2018 ; Cooper et al., 2019 ).

5.1.4 Destination ports

In a mature market, looking for new destinations to expand the catalogue offered by cruise lines to potential customers means that most new ports correspond to port areas in developing countries ( Vega-Muñoz et al., 2020 ). In view of the positive impact of tourism on the ports of call and hinterland, it is necessary to analyze the factors of lines in port site selection ( Vega-Muñoz et al., 2020 ). It is necessary for the cruise lines to evaluate the port’s traffic, performance, safety risks and other factors before planning the itinerary ( Kofjač et al., 2013 ; Vidmar and Perkovič, 2015 ). The studies of regional port focus on the Mediterranean. The port/terminal serves as a bridge between cruise lines, global operators, and local businesses and infrastructure. The study of port class, concentration, tourist satisfaction, cooperative competition, forms of governance, structure, strategy and other elements within the Mediterranean region ( Kofjač et al., 2013 ; Vidmar and Perkovič, 2015 ; Cusano et al., 2017 ; Esteve-Perez and Garcia-Sanchez, 2018 ; Pallis et al., 2018 ; Sanz-Blas et al., 2019 ), provides port authorities and potential investors with a basis for decision making and facilitates port operators to address the challenge of cruise traffic seasonality and thus achieve sustainable port management. In order to reduce the pollution level of the port, the port implements cost differentiation, and proposes to use (electric) bicycles as public transportation for tourists from the port of call to inland scenic spots ( Bardi et al., 2019 ; Mjelde et al., 2019 ).

5.1.5 Environmental and biological protection

In 2017, 449 cruise ships were put into service, 27 more in 2018, and 24 more in 2019. The passenger capacity of these ships ranged from 3,000 to 5,000, causing significant environmental impacts on the world, including polar regions ( Vega-Muñoz et al., 2020 ). The emissions of carbon dioxide and sulfur particles during cruise transport lead to air pollution; the incineration of garbage and the generation of organic waste lead to certain economic impact, social costs as well as water pollution, such as coastal waters polluted by high levels of oil, detergents, plastic residues and bacteria ( Mölders et al., 2013 ; Rumpf et al., 2018 ; Wang et al., 2018 ; Suneel et al., 2019 ). In addition, cruise ships have caused serious impacts on living things. For example, the invasion of alien species, engine noise and collisions lead to the death of birds and affect the ecosystems of many marine species, especially cetaceans ( Bocetti, 2011 ; Casoli et al., 2016 ; Halliday et al., 2018 ). Growing international concern about environmental issues has prompted many major cruise lines to invest in green technology and fulfill their social responsibility in the marine environment, while optimizing the design of ship energy systems and cruise itinerary planning ( Rivarolo et al., 2018 ; Armellini et al., 2019 ; Wang et al., 2019 ; Yan et al., 2019 ).

5.1.6 Cruise diseases

The international composition of the cruise population and its semi-enclosed environment are conducive to the outbreak of infectious diseases, such as vaccine-preventable diseases (chickenpox), respiratory diseases (A/B influenza), diseases caused by norovirus, and Legionella disease ( Mouchtouri et al., 2009 ; Cramer et al., 2012 ; Payne et al., 2018 ). Researches have shown that timely vaccination before sea travel can prevent the outbreak of related diseases ( Mitruka et al., 2012 ). Respiratory diseases usually cause large-scale influenza outbreaks and occur outside the traditional flu season. A comprehensive epidemic prevention and control plan, including timely antiviral treatment, may reduce the impact of the flu epidemic ( Millman et al., 2015 ). Norovirus is prone to gastroenteritis, and individuals in crew cabins and restaurants face the highest risk of infection ( Millman et al., 2015 ). Vigorously promoting good hand-washing habits and increasing the ventilation rate of some or all locations can effectively reduce the risk of infection for passengers ( Millman et al., 2015 ). Isolating sick passengers and cleaning the cabin are also beneficial ( Towers et al., 2018 ). Legionnaires’ disease has a significant relationship with water supply systems. The application of water treatment systems in ship water supply systems is expected to improve ship water management and reduce the incidence of passengers ( Mouchtouri et al., 2012 ).

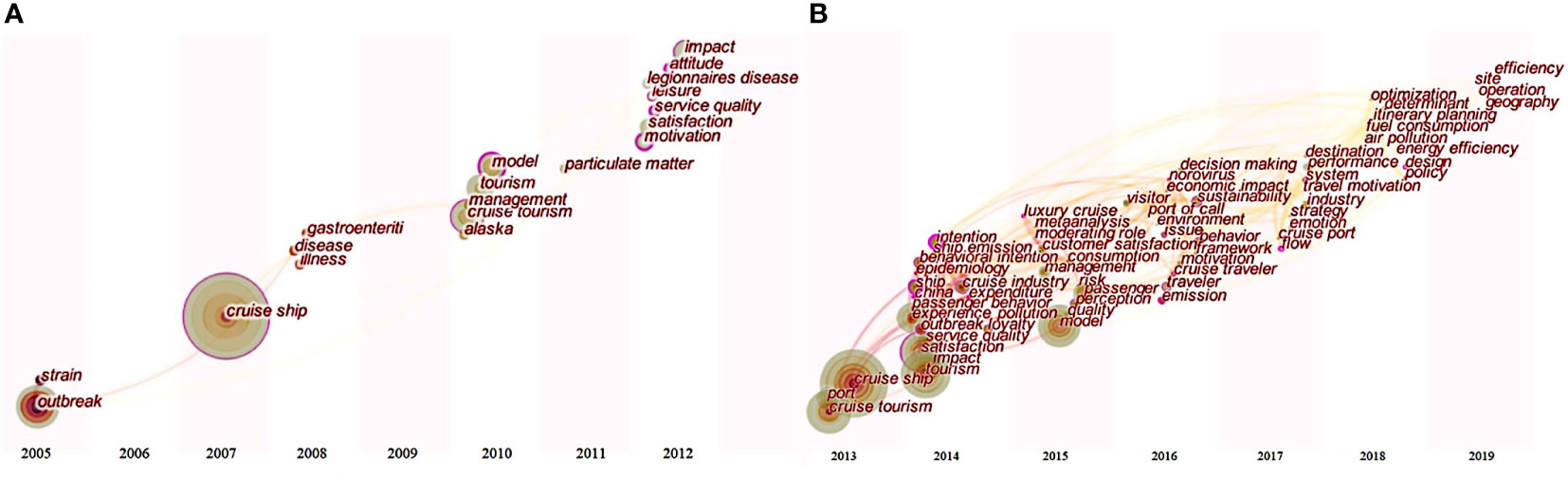

5.2 The evolution and future trends of cruise research hotspots

Figure 8 is a time zone map of the co-occurrence of keywords in cruise research from 2005 to 2019. Since there are fewer keywords from 1996-2004, they are not shown in the map. Keywords such as cruise, cruise tourism, motivation, influence, satisfaction, disease, management, and etc. are shown in Figures 8A, B . The keywords co-occurrence broke out in from 2013 to 2019, indicating that cruise research has entered a boom period at this stage. The research topics are becoming more and more detailed and intersecting with more disciplines. Many new keywords have emerged, such as optimization, itinerary planning, fuel consumption, efficiency, system sustainability, luxury cruises, pollution, and so on.

Figure 8 Keywords co-occurrence time zone map for the cruise research from 2005 to 2019: (A) Keywords co-occurrence time zone map from 2005 to 2012 (B) Keywords co-occurrence time zone map from 2013 to 2019.

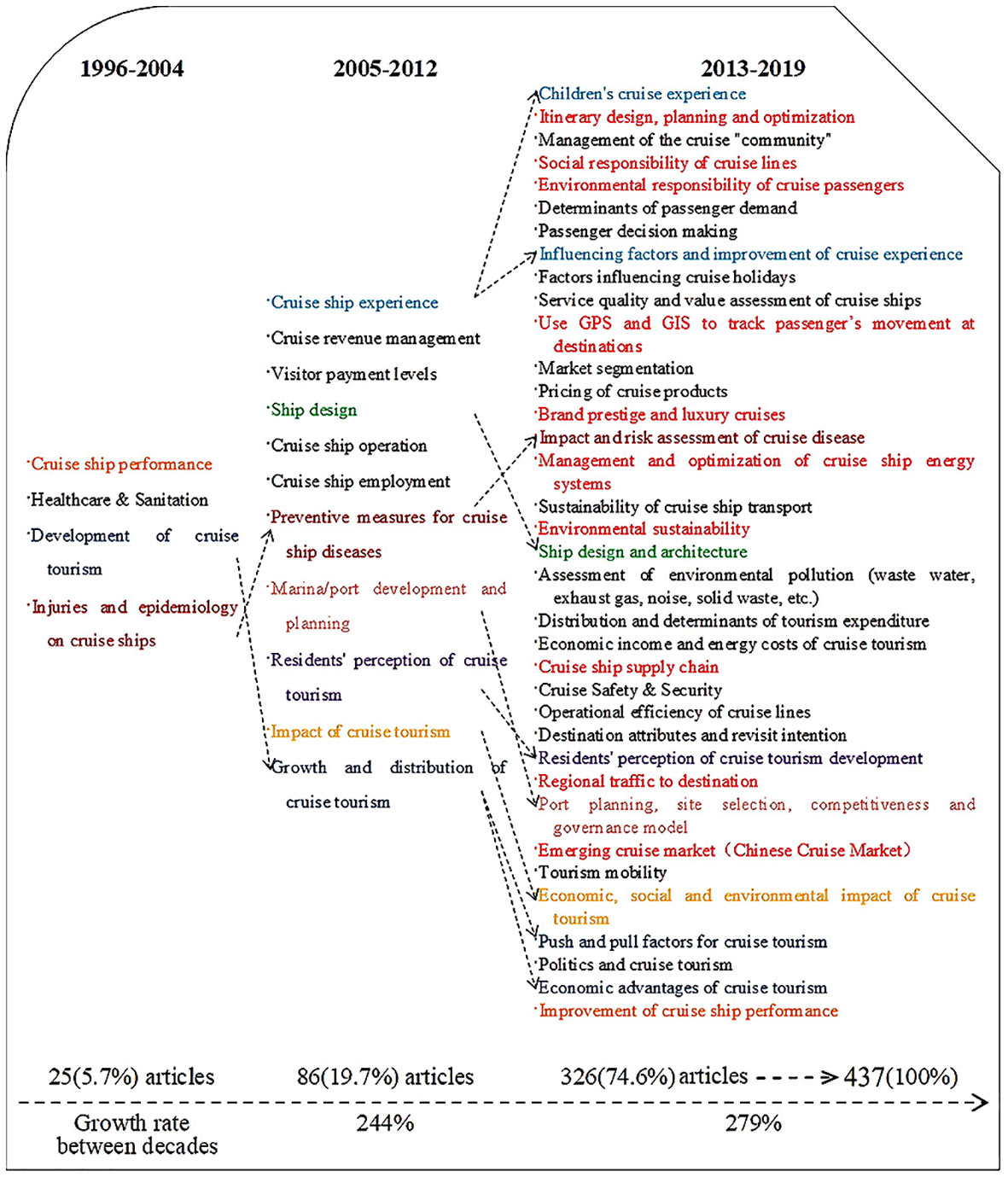

The publications collected by this research are divided into three stages to further understand the evolution of the paradigm and theme of cruise research ( Figure 9 ).

Figure 9 The evolution of hot spots in cruise research.

Phase I: In this stage, injuries and epidemics on cruise ships are more prominent, such as gastroenteritis ( Cramer et al., 2006 ), Legionnaires’ disease ( Pastoris et al., 1999 ), influenza A/B ( Brotherton et al., 2003 ). There are few researches on cruise tourism and cruise performance.

Phase II: Cruise researches have gradually increased by 244% over Phase 1. The scope of research on cruise diseases has expanded, with the emergence of chickenpox, hepatitis E, norovirus, etc., and delves into disease prevention measures. People begin to realize the economic importance brought by the growth of cruise tourism. The cruise market is gradually expanding, and there are more development ideas for terminals or ports. With the development of cruise tourism, research topics such as the design of ships, the payment level of passengers, the employment, experience and operation of cruise ships have emerged.

Phase III: Cruise researches have entered a period of prosperity, by 279% over Phase II. The research area is no longer limited to North America and Europe, but expanded to Asia and even the world, and a new cruise market has emerged. Cruise disease is still the theme of research, but it is more to evaluate the risk and impact through models to find the source of the disease and preventive measures. The scope of impact of tourism or cruise tourism extends to the economic, social and environmental impact of destination ports or communities, with research methods or solutions shifting to novel Internet of Things, such as electronic word of mouth (EWOM), electronic cabin (E-cabin) systems ( Barsocchi et al., 2019 ; Sanz-Blas et al., 2019 ; Buzova et al., 2019a ). Sustainable development is an important research theme at this stage. People are acutely aware of the environmental pollution caused by cruise ships. Environmental responsibility should not be confined to cruise lines and governments, but should extend to port development plans, community residents and every cruise passenger. In addition, various research agendas have been observed, including understanding children’s cruise experience, brand reputation, luxury cruises, itinerary planning, musical performances on board, passenger decision-making behavior, sustainability, and the use of technology to better understand the behavior and mobility trends of cruise passengers in cruise destinations.

Although there are already a large number of cruise research publications, there is a lack of liberating research on some important topics in the cruise industry, including the research themes in red in Figure 8 , which have gradually emerged in recent years and will continue to be of interest to scholars in the future. It is mainly reflected in the following aspects:

5.2.1 Cruise supply chain

One important research topic that has been overlooked in existing cruise researches is the cruise supply chain. From the perspective of the global value chain of the cruise industry, cruise operations account for 50% of the output value, with the highest added value, and cruise supply is a key link in cruise operation management and has considerable economic benefits ( Huang and Yang, 2020 ). Due to the short replenishment time of the cruise ship, there may be conflicts of interest with the supplier, which will affect the customer experience. Therefore, it is necessary to do in-depth research on the cruise supply chain to promote the establishment of long-term and reliable relationships between cruise lines and service providers.

5.2.2 The use of technology in cruise ships

In addition to the following two items, one is to use GPS technology to track the behavior of cruise passengers at their destinations ( De Cantis et al., 2016 ), and the other is to use GIS to study the mobility of cruise passengers ( Paananen and Minoia, 2019 ).According to Naci Polata, no research technology has been found to reduce the negative impact of the cruise industry or promote the sustainable development of the cruise industry.

5.2.3 Children’s cruise experience

The importance of children in the family’s choice of cruise line was identified. While on board, they demanded a certain amount of autonomy so that they could create their own memorable cruise experience ( Radic, 2019 ). Cruise tourism increasingly attracts millennial and generation X family vacations. Children play a decisive role in shaping the future consumption pattern of cruise travel ( Radic, 2019 ). Therefore, with the rapid increase in family cruise travel packages, it is extremely important to understand children’s cruise travel experience ( Wondirad, 2019 ).

5.2.4 Itinerary design, planning and optimization

According to the survey, more and more tourists will stay at or near the cruise port. In fact, 65% of cruise passengers spend a few more days in the ports of departure and arrival ( China.com, C, 2019 ). The new generation of cruise passengers has seen a shift in journey schedule, with many passengers looking for shorter trips. The traditional cruise itinerary has been completely unable to meet the needs of passengers. Cruise itinerary planning needs to focus not only on passenger satisfaction, but also on the impact of emission control zones on cruise traffic ( Zhen et al., 2018 ). It is a big challenge for cruise lines to plan, design and optimize a highly attractive, low-polluting itinerary ( China.com, C, 2019 ).

5.2.5 Brand reputation and luxury cruises

Luxury cruises are considered to be one of the most promising target markets due to the huge growth potential ( Jeong and Hyun, 2019 ). However, as the service is expensive, a reasonable pricing strategy is required ( Jeong and Hyun, 2019 ). Reputation plays a certain role in the operation of luxury cruises and can influence passenger perceptions of happiness and loyalty ( Hwang and Han, 2014 ). Research on brand reputation helps cruise lines to better develop their luxury cruise business.

5.2.6 Public transportation at the destination

The increase of cruise activities in port cities has caused a certain degree of traffic congestion to the local tourism resources and historical centers, and hindered the flow of passengers from the port of call to inland tourist attractions ( Rosa-Jiménez et al., 2018 ). The mobility of tourists is an important criterion for cruise destinations as well as the city’s economic resources ( Perea-Medina et al., 2019 ). Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the potential public transportation modes of cruise passengers entering the mainland.

5.2.7 Environmental responsibility of cruise passengers and corporate social responsibility

The global growth of the cruise shipping industry has had a strong impact on the ecological environment. The cross-regional and multi-participant nature of cruise routes and the trend towards larger ships have led to a wider environmental impact. Environmental sustainability has always been a hot spot in cruise research, but the research branch rarely involves the environmental responsibility of cruise passengers and corporate social responsibility. Cruise passengers and companies should jointly participate in environmental protection actions.

5.2.8 Optimization of energy systems

The cruise industry is facing more and more challenges due to the strict regulation of anthropogenic emission limits, new targets to reduce carbon emissions and potential carbon pricing ( Trivyza et al., 2019 ). In addition, it is imperative for the cruise industry to discover new technologies and clean energy and promote development. The performance of cruise energy systems needs to be continuously optimized to meet the comprehensive goals of life cycle cost and life cycle carbon emissions.

5.2.9 The relationship between climate change and the cruise industry

Causing changes in the ecosystems of sensitive areas such as the polar regions climate change has brought serious consequences to humans and requires immediate response measures ( Dawson et al., 2016 ; Lamers and Pashkevich, 2018 ). Although the number of tourists in sensitive areas such as Antarctica seems to be relatively small compared to other destinations, recent trends show that the number of tourists in these areas has increased sharply, with no signs of decrease, especially the emergence of large cruise ships ( Wondirad, 2019 ). Cruise tourism has a great impact on climate change, and the industry itself is also affected by extreme weather due to climate change. Therefore, the relationship between cruise industry and climate change should be one of the most thematic research areas in the next few years ( Bender et al., 2016 ; Wondirad, 2019 ).

5.2.10 Chinese cruise market

In recent years, the growth rate of emerging cruise market in Asia & Pacific region is higher than the average level ( Sun et al., 2014 ). As one of the core elements of the Asian cruise market, China is growing rapidly in terms of cruise visits ( Sun et al., 2014 ). However, there is currently a lack of research on the development of China’s cruise industry to enable stakeholders in cruise tourism to understand the characteristics of the Chinese market. This means that it is necessary to carry out relevant scientific research into this budding and promising area of cruise passenger generation ( Wondirad, 2019 ).

5.2.11 Risk management of cruise diseases

The outbreak of COVID-19 has caused a serious negative impact on the global cruise industry, and it also highlights that international epidemic prevention is still weak ( McAleer, 2020 ). Since the worldwide suspension of cruises, the international cruise industry has carefully analyzed the lessons of the infection incidents of cruise tourists in Yokohama, Japan in the early stages of the epidemic, and has actively studied safety and health measures and risk prevention mechanisms for the resumption of cruises. Some countries and regions around the world have resumed cruise ships. However, among the cruise ships that have resumed sailing around the world, some cruise ships have been suspended due to the epidemic. Therefore, the research of cruise disease risk management is still worth discussing.

6 Conclusion

In this bibliometric study, 437 valid articles on cruise research were analyzed. These documents are recorded in the core collection of Web of Science from 1996 to 2019. This paper uses CiteSpace software to visualize the data of effective articles on cruise research, and analyzes the research status and dynamic frontiers. There is an overall increasing trend in the amount of published literature on cruise research, with reasonable local fluctuations. In recent years, the average number of publications per year has exceeded 40, indicating that cruise research has attracted widespread academic attention.

The United States, Italy, and China are the main countries for cruise research, and the United States maintains extensive cooperation with many countries. The number of published documents and high-quality academic results reflect the important position of the United States in cruise research. In terms of regional distribution, North America, Europe and Asia are the main regions of cruise research. This is consistent with the market phenomenon of the global cruise industry. The University of Genoa, the university of Sejong and the university of Valencia are highly productive organizations whose research has a significant impact. The organizations engaged in research in this area are predominantly independent, with fewer opportunities for collaboration with each other, and the intensity of collaboration needs to be strengthened.

The more prominent of the authors’ collaborative network are Heesup Han, Sunghyup Sean Hyun, Silvia Sanzblas, Daniela Buzova and Juan Gabriel Brida. They have contributed to the in-depth research and application in the cruise field. However, the author’s centrality is low, and there is a lack of extensive cooperation with other scholars, which leads to the low cooperation intensity of the author. The more prominent of the cited authors are Brida JG, Petrick JF and Hung K. They have provided some basic research and guided others in establishing new perspectives on cruise research.

The hot spots of cruise research can be summarized as cruise tourism, luxury cruises, cruise passengers, destination ports, environmental and biological protection and cruise diseases. The development and change of cruise discipline are related to its hot spot evolution. In recent years, environmental engineering, green sustainable technology, energy and fuel have emerged in the background of cruise research, which indicates that the relationship between cruise industry and ecological environment is the focus of sustainable development in the future. Based on this idea, this paper summarizes some future research trends in the field of cruise, including the environmental responsibility of cruise passengers and corporate social responsibility, the optimization of energy system, and the relationship between climate change and cruise industry. These research topics should be widely concerned by the academia and the government.

In 2020, the global outbreak of the novel coronavirus pneumonia caused the cruise industry to withstand unprecedented impacts and challenges. The epidemic on cruise ships such as “Diamond Princess” severely affected market confidence, causing more than two-thirds of the world’s cruise ships to be suspended. This study found that the topic of research on cruise diseases has been lasting for a long time and has always been a hot spot and focus of research. The awareness of prevention and control and related technologies have been improved but not received due attention compared with the speed of cruise industry and market development. In particular, the epidemic prevention and management capabilities in the design, construction and operation of cruise ships need to be improved. Therefore, it is predicted that this area of research will be a key area in the near future.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, writing - review & editing. HL: Investigation, methodology, formal analysis. XW: Supervision, resources. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The study was funded by MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Liberal arts and Social Sciences Foundation (21YJA79029) and the Major Research Plan of National Social Science Foundation (18ZDA052).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Armellini A., Daniotti S., Pinamonti P., Reini M. (2019). “Reducing the environmental impact of large cruise ships by the adoption of complex cogenerative/trigenerative energy systems,” in Energy conversion and management , vol. 198. (England: Elsevier Ltd). doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.111806

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bahja F., Cobanoglu C., Berezina K., Lusby C. (2019). “Factors influencing cruise vacations: the impact of online reviews and environmental friendliness,” in Tourism review , vol. 74. (England: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.), 400–415. doi: 10.1108/TR-12-2017-0207

Bardi A., Mantecchini L., Grasso D., Paganelli F., Malandri C. (2019). Flexible mobile hub for e-bike sharing and cruise tourism: A case study. Sustain. (Switzerland). 11 (19). doi: 10.3390/su11195462

Barsocchi P., Ferro E., Rosa D La., Mahroo A., Spoladore D. (2019). E-cabin: A software architecture for passenger comfort and cruise ship management. Sens. (Switzerland). 19 (22). doi: 10.3390/s19224978

Bender N. A., Crosbie K., Lynch H. J. (2016). “Patterns of tourism in the Antarctic peninsula region: A 20-year analysis,” in Antarctic Science , vol. 28. (America: Cambridge University Press), 194–203. doi: 10.1017/S0954102016000031

Bocetti C. I. (2011). Cruise ships as a source of avian mortality during fall migration. Wilson J. Ornithol. 123 (1), 176–178. doi: 10.1676/09-168.1

Brida J. G., Pulina M., Riaño E., Zapata-Aguirre S. (2013). “Cruise passengers in a homeport: A market analysis,” in Tourism geographies , vol. 15. (England: Routledge), 68–87. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2012.675510

Brotherton J. M. L., Delpech V. C., Gilbert G. L., Hatzi S., Paraskevopoulos P. D., McAnulty J. M., et al. (2003). A large outbreak of influenza a and b on a cruise ship causing widespread morbidity. Epidemiol. Infect. 130 (2), 263–271. doi: 10.1017/S0950268802008166

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Buzova D., Sanz-Blas S., Cervera-Taulet A. (2019a). Does culture affect sentiments expressed in cruise tours’ eWOM? Service Industries J. 39 (2), 154–173. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2018.1476497

Buzova D., Sanz-Blas S., Cervera-Taulet A. (2019b). “Tour me onshore”: understanding cruise tourists’ evaluation of shore excursions through text mining. J. Tourism Cultural Change. 17 (3), 356–373. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2018.1552277

Cashman D. (2016). “The most atypical experience of my life: The experience of popular music festivals on cruise ships,” in Tourist studies , vol. 17. (Canada: SAGE Publications Ltd), 245–262. doi: 10.1177/1468797616665767

Casoli E., Ventura D., Modica M. V., Belluscio A., Capello M., Oliverio M., et al. (2016). “A massive ingression of the alien species mytilus edulis l. (Bivalvia: Mollusca) into the Mediterranean Sea following the Costa Concordia cruise-ship disaster,” in Mediterranean Marine science , vol. 17. (Greece: Hellenic Centre for Marine Research), 404–416. doi: 10.12681/mms.1619

Castillo-Manzano J. I., Lopez-Valpuesta L., Alanís F. J. (2015). “Tourism managers’ view of the economic impact of cruise traffic: the case of southern Spain,” in Current issues in tourism , vol. 18. (England: Routledge), 701–705. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.907776

Chen C. (2006). CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 57 (3), 359–377. doi: 10.1002/asi.20317

Chen C. A. (2016). “How can Taiwan create a niche in asia’s cruise tourism industry?,” in Tourism management , vol. 55. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.015

Chen J. M., Petrick J. F., Papathanassis A., Li X. (2019). “A meta-analysis of the direct economic impacts of cruise tourism on port communities,” in Tourism management perspectives (Netherlands: Elsevier), 209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.05.005

Chen J. M., Zhang J., Nijkamp P. (2016). “A regional analysis of willingness-to-pay in Asian cruise markets,” in Tourism economics (England: SAGE Publications Inc.), 809–824. doi: 10.1177/1354816616654254

China.com, C (2019) Cruise lines international association: 2020 cruise industry outlook report . Available at: http://www.ccyia.com/?p=1077 (Accessed 10 October 2020).

Google Scholar

Chua B. L., Lee S., Goh B., Han H. (2015). Impacts of cruise service quality and price on vacationers’ cruise experience: Moderating role of price sensitivity. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 44, 131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.10.012

Cooper D., Holmes K., Pforr C., Shanka T. (2019). Implications of generational change: European river cruises and the emerging gen X market. J. Vacation Market. 25 (4), 418–431. doi: 10.1177/1356766718814088

Cramer E. H., Blanton C. J., Blanton L. H., Vaughan G. H., Bopp C. A., Forney D. L., et al. (2006). Epidemiology of gastroenteritis on cruise ships 2001-2004. Am. J. Prev. Med. 30 (3), 252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.027

Cramer E. H., Slaten D. D., Guerreiro A., Robbins D., Ganzon A. (2012). Management and control of varicella on cruise ships: A collaborative approach to promoting public health. J. Travel Med. 19 (4), 226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00621.x

Cusano M. I., Ferrari C., Tei A. (2017). Port hierarchy and concentration: Insights from the Mediterranean cruise market. Int. J. Tourism Res. 19 (2), 235–245. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2106

Dai T., Hein C., Zhang T. (2019). “Understanding how Amsterdam city tourism marketing addresses cruise tourists’ motivations regarding culture,” in Tourism management perspectives , vol. 29. (Netherlands: Elsevier B.V.), 157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.12.001

Dawson J., Stewart E. J., Johnston M. E., Lemieux C. J. (2016). Identifying and evaluating adaptation strategies for cruise tourism in Arctic Canada. J. Sustain. Tourism. 24 (10), 1425–1441. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1125358

De Cantis S., Ferrante M., Kahani A., Shoval N. (2016). “Cruise passengers’ behavior at the destination: Investigation using GPS technology,” in Tourism management , vol. 52. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 133–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.018

Duman T., Mattila A. S. (2005). The role of affective factors on perceived cruise vacation value. Tourism Manage. 26 (3), 311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.11.014

Esteve-Perez J., Garcia-Sanchez A. (2018). “Dynamism patterns of western mediterranean cruise ports and the coopetition relationships between major cruise ports,” in Polish maritime research , vol. 25. (Poland: De Gruyter Open Ltd), 51–60. doi: 10.2478/pomr-2018-0006

Forgas-Coll S., Palau-Saumell R., Sánchez-García J., Garrigos-Simon FJ. (2016). “Comparative analysis of American and Spanish cruise passengers’ behavioral intentions,” in RAE revista de administracao de empresas , vol. 56. (England: Fundacao Getulio Vargas), 87–100. doi: 10.1590/S0034-759020160108

Gabe T. M., Lynch C. P., McConnon J. C. (2006). Likelihood of cruise ship passenger return to a visited port: The case of bar harbor, Maine. J. Travel Res. 44 (3), 281–287. doi: 10.1177/0047287505279107

Halliday W. D., Têtu P. L., Dawson J., Insley S. J., Hilliard R. C. (2018). “Tourist vessel traffic in important whale areas in the western Canadian Arctic: Risks and possible management solutions,” in Marine policy , vol. 97. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.08.035

Han H., Hyun S. S. (2018). Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 70 (October 2017), 75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.024

Han H., Lee M. J., Kim W. (China: 2018). “Antecedents of green loyalty in the cruise industry: Sustainable development and environmental management,” in Business strategy and the environment , vol. 27. (John Wiley and Sons Ltd), 323–335. doi: 10.1002/bse.2001

Hefner F., Mcleod B., Crotts J. (2014). “Research note: An analysis of cruise ship impact on local hotel demand - an event study in Charleston, south Carolina,” in Tourism economics , vol. 20. (England: University of London), 1145–1153. doi: 10.5367/te.2013.0328

Hong W. (2019) GREEN BOOK OF CRUISE INDUSTRY:ANNUAL REPORT ON CHINA’S CRUISE INDUSTRY (England: Social Sciences Academic Press). Available at: https://www.sohu.com/a/354330956_99900352 (Accessed 25 December 2020).

Hong W. (2020). GREEN BOOK OF CRUISE INDUSTRY:ANNUAL REPORT ON CHINA’S CRUISE INDUSTRY . Ed. Hong W. (Social Sciences Academic Press).

Huang L., Yang J. (2020). “An improved swarm intelligence algorithm for multi-item joint ordering strategy of cruise ship supply,” in Mathematical problems in engineering , vol. 2020. (Netherlands: Hindawi Limited). doi: 10.1155/2020/5048629

Hung K., Wang S., Denizci Guillet B., Liu Z. (2019). An overview of cruise tourism research through comparison of cruise studies published in English and Chinese. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 77 (May 2018), 207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.031

Hwang J., Han H. (2014). “Examining strategies for maximizing and utilizing brand prestige in the luxury cruise industry,” in Tourism management , vol. 40. (Germany: Elsevier Ltd), 244–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.007

Hyun S. S., Kim M. G. (2015). Negative effects of perceived crowding on travelers’ identification with cruise brand. J. Travel Tourism Market. 32 (3), 241–259. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2014.892469

Jeong J. Y., Hyun S. S. (2019). “Roles of passengers’ engagement memory and two-way communication in the premium price and information cost perceptions of a luxury cruise,” in Tourism management perspectives , vol. 32. (England: Elsevier B.V.). doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100559

Kofjač D., Škurić M., Dragović B., Škraba A. (2013). Traffic modelling and performance evaluation in the kotor cruise port. Strojniski Vestnik/Journal Mechan. Eng. 59 (9), 526–535. doi: 10.5545/sv-jme.2012.942

Lamers M., Pashkevich A. (2018). Short-circuiting cruise tourism practices along the Russian barents sea coast? the case of arkhangelsk. Curr. Issues Tourism. 21 (4), 440–454. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1092947

Lee S., Chua B. L., Han H. (2017). Role of service encounter and physical environment performances, novelty, satisfaction, and affective commitment in generating cruise passenger loyalty. Asia Pacific J. Tourism Res. 22 (2), 131–146. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2016.1182039

Lee Y., Kim I. (2019). “A value co-creation model in brand tribes: the effect of luxury cruise consumers’ power perception,” in Service business , vol. 13. (England: Springer Verlag), 129–152. doi: 10.1007/s11628-018-0373-x

Li N., Fairley S. (2018). “Mainland Chinese cruise passengers’ perceptions of Western service,” in Marketing intelligence and planning , vol. 36. (England: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.), 601–615. doi: 10.1108/MIP-08-2017-0171

Lyu J., Mao Z., Hu L. (2018). Cruise experience and its contribution to subjective well-being: A case of Chinese tourists. Int. J. Tourism Res. 20 (2), 225–235. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2175

Ma M. Z., Fan H. M., Zhang E. Y. (2018). “Cruise homeport location selection evaluation based on grey-cloud clustering model,” in Current issues in tourism (Routledge, England;), vol. 21. , 328–354. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1083951

MacNeill T., Wozniak D. (2018). “The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism,” in Tourism management , vol. 66. (Turkey: Elsevier Ltd), 387–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.11.002

McAleer M. (2020). Prevention is better than the cure: Risk management of COVID-19. J. Risk Financial Manage. 13 (3), 46. doi: 10.3390/jrfm13030046

Millman A. J., Kornylo Duong K., Lafond K., Green N. M., Lippold S. A., Jhung M. A., et al. (2015). Influenza outbreaks among passengers and crew on two cruise ships: A recent account of preparedness and response to an ever-present challenge. J. Travel Med. 22 (5), 306–311. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12215

Mitruka K., Felsen C. B., Tomianovic D., Inman B., Street K., Yambor P., et al. (2012). Measles, rubella, and varicella among the crew of a cruise ship sailing from florida, united state. J. Travel Med. 19 (4), 233–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00620.x

Mjelde A., Endresen Ø., Bjørshol E., Gierløff C. W., Husby E., Solheim J., et al. (2019). “Differentiating on port fees to accelerate the green maritime transition,” in Marine pollution bulletin , vol. 149. (Netherlands: Elsevier Ltd). doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110561

Mölders N., Gende S., Pirhalla M. (2013). “Assessment of cruise-ship activity influences on emissions, air quality, and visibility in glacier bay national park,” in Atmospheric pollution research , vol. 4. (England: Dokuz Eylul Universitesi), 435–445. doi: 10.5094/APR.2013.050

Moreno-Guerrero A. J., de los Santos P. J., Pertegal-Felices M. L., Costa R. S. (2020). Bibliometric study of scientific production on the term collaborative learning in web of science. Sustain. (Switzerland) 12 (14), 1–19. doi: 10.3390/su12145649

Mouchtouri V., Black N., Nichols G., Paux T., Riemer T., Rjabinina J., et al. (2009). “Preparedness for the prevention and control of influenza outbreaks on passenger ships in the EU: the SHIPSAN TRAINET project communication,” in Euro surveillance : bulletin européen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin (Sweden: Eur Centre Dis Prevention & Control), vol. 14. , 1–4. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.21.19219-en

Mouchtouri V. A., Bartlett C. L.R., Diskin A., Hadjichristodoulou C. (2012). “Water safety plan on cruise ships: A promising tool to prevent waterborne diseases,” in Science of the total environment , vol. 429. (England: Elsevier B.V.), 199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.018

Oklevik O., Nysveen H., Pedersen P. E. (2018). Influence of design on tourists’ recommendation intention: an exploratory study of fjord cruise boats. J. Travel Tourism Market. 35 (9), 1187–1200. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2018.1487367

Paananen K., Minoia P. (2019). “Cruisers in the city of Helsinki: staging the mobility of cruise passengers,” in Tourism geographies , vol. 21. (America: Routledge), 801–821. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2018.1490341

Pallis A. A., Parola F., Satta G., Notteboom T. E. (2018). “Private entry in cruise terminal operations in the Mediterranean Sea,” in Maritime economics and logistics (England: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.), 1–28. doi: 10.1057/s41278-017-0091-7

Pastoris M. C., Lo Monaco R., Goldoni P., Mentore B., Balestra G., Ciceroni L., et al. (1999). “Legionnaires’ disease on a cruise ship linked to the water supply system: Clinical and public health implications,” in Clinical infectious diseases , vol. 28. (England: University of Chicago Press), 33–38. doi: 10.1086/515083

Payne M., Skowronski D., Sabaiduc S., Merrick L., Lowe C. (2018). Increase in hospital admissions for severe influenza A/B among travelers on cruise ships to alask. Emerg. Infect. Dis. Centers Dis. Control Prev. (CDC) 24 (3), 566–568. doi: 10.3201/eid2403.171378

Perea-Medina B., Rosa-Jiménez C., Andrade M. J. (2019). “Potential of public transport in regionalisation of main cruise destinations in Mediterranean,” in Tourism management , vol. 74. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 382–391. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.016

Personal M., Archive R. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on tourism Industry: A review Vol. 102834) (England: MPRA Paper). Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/102834/ .

Petrick J. F. (2005). Segmenting cruise passengers with price sensitivity. Tourism Manage. 26 (5), 753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.03.015

Radic A. (2019). “Towards an understanding of a child’s cruise experience,” in Current issues in tourism , vol. 22. (Bulgaria: Routledge), 237–252. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.1368463

Rivarolo M., Rattazzi D., Magistri L. (2018). Best operative strategy for energy management of a cruise ship employing different distributed generation technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 43 (52), 23500–23510. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.10.217

Rosa-Jiménez C., Perea-Medina B., Andrade M. J., Nebot N. (2018). An examination of the territorial imbalance of the cruising activity in the main Mediterranean port destinations: Effects on sustainable transport. J. Transport Geogr. 68, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.02.003

Rumpf S. B., Alsos I. G., Ware C. (2018). “Prevention of microbial species introductions to the arctic: The efficacy of footwear disinfection measures on cruise ships,” in NeoBiota , vol. 37). (England: Pensoft Publishers), 37–49. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.37.22088

Sanz-Blas S., Buzova D., Schlesinger W. (2019). The sustainability of cruise tourism onshore: The impact of crowding on visitors’ satisfaction. Sustain. (Switzerland). 11 (6). doi: 10.3390/su11061510

Sanz Blas S., Carvajal-Trujillo E. (2014). “Cruise passengers’ experiences in a Mediterranean port of call. the case study of Valencia,” in Ocean and coastal management (England: Elsevier Ltd), 307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.10.011

Shim C., Kang S., Kim I., Hyun S. S. (2017). “Luxury-cruise travellers’ brand community perception and its consequences,” in Current issues in tourism , vol. 20. (England: Routledge), 1489–1509. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1033386

Sun X., Feng X., Gauri D. K. (2014). The cruise industry in China: Efforts, progress and challenges. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 42, 71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.009

Suneel V., Saha M., Rathore C., Sequeira J., Mohan P. M. N., Ray D., et al. (2019). “Assessing the source of oil deposited in the surface sediment of mormugao port, goa - a case study of MV Qing incident,” in Marine pollution bulletin , vol. 145. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.05.035

Towers S., Chen J., Cruz C., Melendez J., Rodriguez J., Salinas A., et al. (2018). Quantifying the relative effects of environmental and direct transmission of norovirus. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5 (3). doi: 10.1098/rsos.170602

Trivyza N. L., Rentizelas A., Theotokatos G. (2019). “Impact of carbon pricing on the cruise ship energy systems optimal configuration,” in Energy , vol. 175. (Elsevier Ltd), 952–966. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2019.03.139

Vega-Muñoz A., Arjona-Fuentes J. M., Ariza-Montes A., Han H., Law R., et al. (2020). In search of “a research front” in cruise tourism studies. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 85 (July), 102353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102353

Vidmar P., Perkovič M. (2015). “Methodological approach for safety assessment of cruise ship in port,” in Safety science , vol. 80. (Netherlands: Elsevier), 189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2015.07.013

Wang G., Li K. X., Xiao Y. (2019). “Measuring marine environmental efficiency of a cruise shipping company considering corporate social responsibility,” in Marine policy , vol. 99. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.10.028

Wang S., Zhen L., Zhuge D. (2018). “Dynamic programming algorithms for selection of waste disposal ports in cruise shipping,” in Transportation research part b: Methodological , vol. 108. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.trb.2017.12.016

Wondirad A. (2019). “Retracing the past, comprehending the present and contemplating the future of cruise tourism through a meta-analysis of journal publications,” in Marine policy , vol. 108. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 103618. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103618

Yan Y., Zhang H., Long Y., Wang Y., Liang Y., Song X., et al. (2019). Multi-objective design optimization of combined cooling, heating and power system for cruise ship application. J. Cleaner Product. 233, 264–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.047

Yu J. (2019). Verification of the role of the experiential value of luxury cruises in terms of price premium. Sustain. (Switzerland) 11 (11), 1–15. doi: 10.3390/su11113219

Zhen L., Li M., Hu Z., Lv W., Zhao X. (2018). “The effects of emission control area regulations on cruise shipping,” in Transportation research part d: Transport and environment , vol. 62. (England: Elsevier Ltd), 47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2018.02.005

Keywords: cruise ship, Citespace, low carbon, sustainability, cruise tourism market

Citation: Meng S, Li H and Wu X (2023) International cruise research advances and hotspots: Based on literature big data. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1135274. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1135274

Received: 31 December 2022; Accepted: 23 February 2023; Published: 09 March 2023.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2023 Meng, Li and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hua Li, [email protected] ; Xianhua Wu, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Global Vessel-Source Maritime Pollution Governance—Technical Innovation and Policy Orientation

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

cruise ship

Definition of cruise ship

Examples of cruise ship in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'cruise ship.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Dictionary Entries Near cruise ship

cruiserweight

Cite this Entry

“Cruise ship.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cruise%20ship. Accessed 1 Apr. 2024.

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »