National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Our guide to the UK & Ireland

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Inside the Very Real World of 'Slum Tourism'

By Mark Ellwood

Hurricane Katrina left physical and emotional scars on New Orleans, and America, but nowhere was its impact more devastating than the city’s Lower Ninth Ward. Three years after the storm, in October 2008, the district was still pockmarked with half-demolished homes and patches of overgrown grass. It was also dotted with artworks, site-specific installations by the likes of Wangechi Mutu and her Ms Sarah House . Those works formed part of the city’s inaugural art biennial, Prospect New Orleans , bringing tourists to drive and wander through the area in droves. But visitors were caught in an uncomfortable paradox, their art viewing underpinned by the backdrop of one of America’s poorest neighborhoods—or what was left of it.

Locals stood by as various VIPs peered at Mutu’s work. When one of the arterati mustered up courage enough to ask if she minded the influx of gawkers, she shrugged and dodged the question. “It’s nice to have the art here, because it means people are coming to see more than just our ruined homes.” Not everyone reacted to the incomers with such neutrality, though—take one hand-painted sign erected in the neighborhood post-Katrina, that read:

TOURIST Shame On You Driving BY without stopping Paying to see my pain 1,600+ DIED HERE

Both reactions are understandable, and spotlight the uneasy distinction locals in the area might have drawn between being viewed rather than feeling seen. Is it wrong, though, to go beyond the sightseeing mainstays of somewhere like the French Quarter and into a corner of the city that might be blighted or underprivileged as these visitors did? It’s an awkward, but intriguing, question, and one that underpins a nascent niche in travel. It has been nicknamed ‘slum tourism,’ though it’s a broad umbrella term travel that involves visiting underprivileged areas in well-trafficked destinations. Such experiences are complex, since they can seem simultaneously important (bringing much-needed revenues, educating visitors first hand) and inappropriate (a gesture of misunderstanding fitting for a modern-day Marie Antoinette).

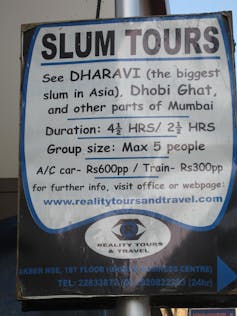

Indeed, even those who operate in the field seem to struggle to reconcile those divergent urges. Researching this story, there was resistance, suspicion, and even outright hostility from seasoned slum tourism vets. Deepa Krishnan runs Mumbai Magic , which specializes in tours around the city, home to what’s estimated as Asia’s largest slum; here, about a million people live in ad hoc homes a few miles from Bollywood’s glitz (it’s now best known as home to the hero of Slumdog Millionaire ). "The Spirit of Dharavi" tour takes in this settlement, a two-hour glimpse into everyday life aiming to show that the squalor for which it’s become shorthand is only part of Dharavi story. It’s also a hub of recycling, for example, and home to women’s co-op for papadum-making. Organized as a community project, rather than on a commercial basis, all profits are ploughed back into Dharavi. Yet pressed to talk by phone rather than email, Deepa balked. “I’ve been misquoted too often,” she said.

The organizer of another alt-tourism operation was even more reluctant, and asked not to be quoted, or included here, at all. Its superb premise—the formerly homeless act as guides to help visitors see and understand overlooked corners of a well-trafficked city—seemed smartly to upend tradition. Rather than isolating ‘the other,’ it shows the interconnectedness of so much in a modern city. The fact that both of these firms, whose businesses fall squarely into such non-traditional tours, are so squeamish about the topic is instructive—and reassuring for the rest of us when we’re conflicted about whether or not it’s ethical to treat deprivation as a distraction.

Call it poorism, misery tourism, poverty tourism—it still smacks of exploitation.

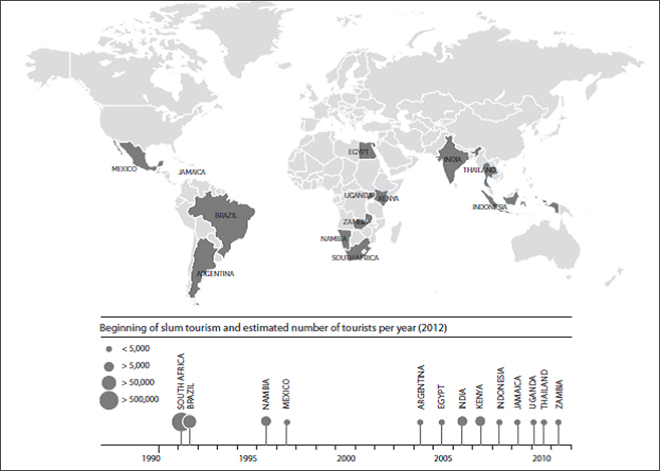

The contemporary concept of slum tourism dates back about 30 years, according to Ko Koens, Ph.D., a Dutch academic who specializes in this field and runs slumtourism.net . The South African government began bussing municipal workers into townships like Soweto in the 1980s, he explains, intending to educate them on no-go areas within their fiefdom. “International tourists, mostly activists, who wanted to show their support [for township-dwellers] started doing these tours, too. And after apartheid ended, the operators who were running them for the government realized they could do them commercially.” (It’s now a vital part of the country’s tourism economy, with some estimates that one in four visitors to the country book a Township Tour. )

Simultaneously, tourists were beginning to explore the slums or favelas of Rio de Janeiro. These are the shantytowns that six percent of Brazil’s population calls home. Bolted to the steep hills overlooking the waterfront mansions where wealthy Cariocas chose to live, these higgledy piggledy shacks perch precariously, as if jumbled in the aftermath of an earthquake. From here, the idea of slum tourism began spreading across the world, from Nairobi to the Dominican Republic, and of course, India. Mumbai Magic isn’t alone in operating tours of Bombay’s Dharavi slums—there are countless tours available of areas that now rival the Marine Drive or the Gateway of India as local attractions.

Yet though it’s a thriving new niche, many travelers remain squeamish about the idea. In part, of course, it’s thanks to the words "slum tourism," yet none of the alternatives seem any less confrontational. Call it poorism, misery tourism, poverty tourism—it still smacks of exploitation. There are also safety concerns, too: After all, Brazil supplied almost half the entries in a recent list of the world’s 50 most dangerous cities , not to mention that the world’s latest health crisis is headquartered in the stagnant waters on which the favela residents rely. The sense of being an interloper, or that such deprivation is Disneyfied into a showcase solely for visitors, is an additional factor—especially when spoofish ideas like Emoya’s Shanty Town hotel , a faux South African slum that offsets discomforts like outdoor toilets with underfloor heating and Wi-Fi, turn out not to be Saturday Night Live skits.

Muddled motivations add to the discomfort; one in-depth study found it was pure curiosity, rather than education, say, or self-actualization, that drove most visitors to book a trip around the Dharavi slums. One first-hand account by a Kenyan who went from the slums of Nairobi to studying at Wesleyan University underlines those awkward findings. “I was 16 when I first saw a slum tour. I was outside my 100-square-foot house washing dishes… “ he wrote. “Suddenly a white woman was taking my picture. I felt like a tiger in a cage. Before I could say anything, she had moved on.” He makes one rule of any such trips all too clear: If you undertake any such tours, focus on memories rather than Instagram posts.

Laura Kiniry

Blane Bachelor

Stacey Lastoe

Suddenly a white woman was taking my picture. I felt like a tiger in a cage.

The biggest challenge, though, is the lack of accreditation. It's still a frustratingly opaque process, to gauge how profits made will directly improve conditions in that slum, admits Tony Carne, who runs Urban Adventures , a division of socially conscious firm Intrepid Travel. His firm is a moderated marketplace for independent guides—much like an Etsy for travel—and offers a wide range of slum tours around the world. Carne supports some form of regulation to help reassure would-be clients of a slum tour’s ethical credentials. “The entire integrity of our business is sitting on this being the right thing to do,” he says, though he also predicts a shift in the business, likely to make such regulation unnecessary. Many charities have begun suggesting these slum tours to donors keen to see how and where their money is used, outsourced versions of the visits long available to institutional donors. He is already in to co-brand slum tours with several major nonprofits, including Action Aid via its Safe Cities program; Carne hopes that such partnerships will reassure travelers queasy about such tours’ ethics and finances. “Everyone from the U.N. down has said poverty alleviation through tourism can only be a reality if someone does something,” he says. “It will not solve itself by committee. It will solve itself by action.”

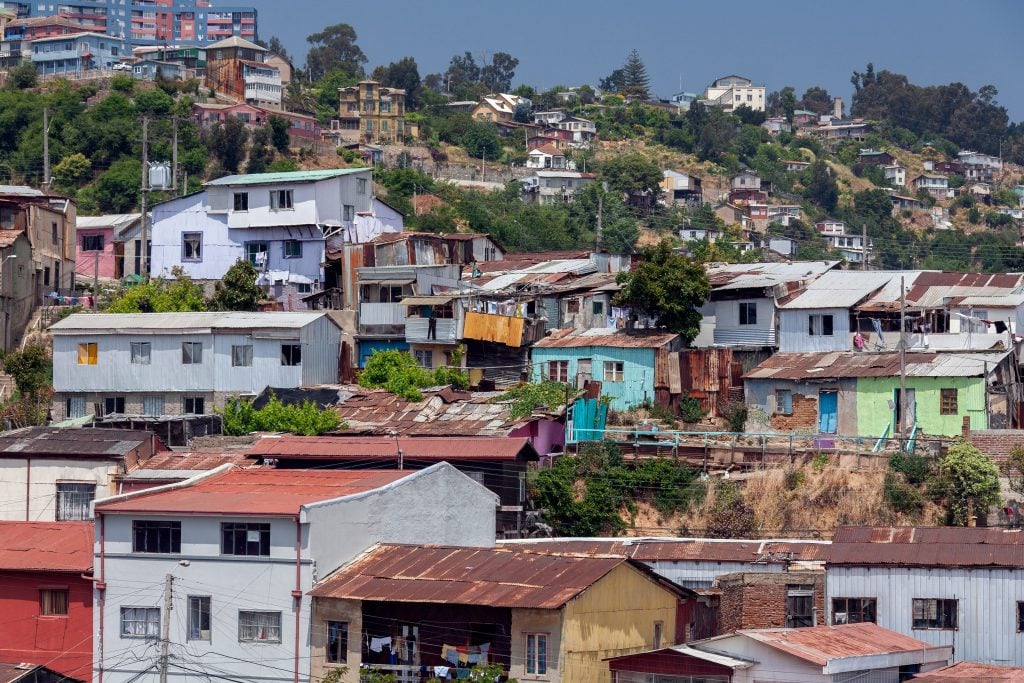

Carne’s theory was echoed by my colleague Laura Dannen Redman, who visited the Philippi township in Cape Town under the aegis of a local nonprofit. It was a private tour, but the group hopes to increase awareness to bolster the settlement’s infrastructure. She still vividly recalls what she saw, half a year later. “The homes were corrugated iron, but tidy, exuding a sense of pride with clean curtains in the windows. But there was this one open gutter I can't forget. The water was tinged green, littered with what looked like weeks’ worth of garbage—plastic wrappers and bottles and other detritus. It backed the neighborhood like a gangrenous moat," she says. "They deserve better. It does feel disingenuous, shameful, even if you’re there to learn and want to help. But the end result was motivating. We did feel called to action, to pay more attention to the plight of so many South Africans.” In the end, perhaps, it isn’t what we call it, or even why we do it that matters—it’s whether the slum tourism experience inspires us to try to make a change.

Slumming it: how tourism is putting the world’s poorest places on the map

Lecturer in the Political Economy of Organisation, University of Leicester

Disclosure statement

From 2012-2014 Fabian Frenzel was a Marie-Curie Fellow and has received funding from the European Union to conduct his research on slum tourism.

University of Leicester provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

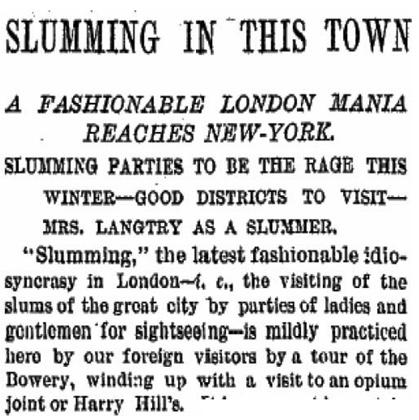

Back in Victorian times, wealthier citizens could sometimes be found wandering among London’s poorer, informal neighbourhoods, distributing charity to the needy. “Slumming” – as it was called – was later dismissed as a morally dubious and voyeuristic pastime. Today, it’s making a comeback; wealthy Westerners are once more making forays into slums – and this time, they’re venturing right across the developing world.

According to estimates by tour operators and researchers , over one million tourists visited a township, favela or slum somewhere in the world in 2014. Most of these visits were made as part of three or four-hour tours in the hotspots of global slum tourism; major cities and towns in Johannesburg, Rio de Janeiro and Mumbai.

There is reason to think that slum tourism is even more common than these numbers suggest. Consider the thousands of international volunteers, who spend anything from a few days to several months in different slums across the world.

The gap year has become a rite of passage for young adults between school and university and, in the UK, volunteering and travel opportunities are often brokered by commercial tourism operators. In Germany and the US, state sponsored programs exist to funnel young people into volunteering jobs abroad.

International volunteering is no longer restricted to young people at specific points in their lives. Volunteers today are recruited across a wide range of age groups . Other travellers can be considered slum-tourists: from international activists seeking cross-class encounters to advance global justice, to students and researchers of slums and urban development conducting fieldwork in poor neighbourhoods.

Much modern tourism leads richer people to encounter relatively poorer people and places. But in the diverse practices of slum tourism, this is an intentional and explicit goal: poverty becomes the attraction – it is the reason to go.

Many people will instinctively think that this kind of travel is morally problematic, if not downright wrong. But is it really any better to travel to a country such as India and ignore its huge inequalities?

Mapping inequality

It goes without saying that ours is a world of deep and rigid inequalities. Despite some progress in the battles against absolute poverty, inequality is on the rise globally . Few people will openly disagree that something needs to be done about this – but the question is how? Slum tourism should be read as an attempt to address this question. So, rather than dismissing it outright, we should hold this kind of tourism to account and ask; does it help to reduce global inequality?

My investigation into slum tourism provided some surprising answers to this question. We tend to think of tourism primarily as an economic transaction. But slum tourism actually does very little to directly channel money into slums: this is because the overall numbers of slum tourists and the amount of money they end up spending when visiting slums is insignificant compared with with the resources needed to address global inequality.

But in terms of symbolic value, even small numbers of slum tourists can sometimes significantly alter the dominant perceptions of a place. In Mumbai, 20,000 tourists annually visit the informal neighbourhood of Dharavi , which was featured in Slumdog Millionaire. Visitor numbers there now rival Elephanta Island in Mumbai – a world heritage site.

Likewise, in Johannesburg, most locals consider the inner-city neighbourhood of Hillbrow to be off limits. But tourists rate walking tours of the area so highly that the neighbourhood now features as one of the top attractions of the city on platforms such as Trip Advisor . Tourists’ interest in Rio’s favelas has put them on the map; before, they used to be hidden by city authorities and local elites .

Raising visibility

Despite the global anti-poverty rhetoric, it is clear that today’s widespread poverty does benefit some people. From their perspective, the best way of dealing with poverty is to make it invisible. Invisibility means that residents of poor neighbourhoods find it difficult to make political claims for decent housing, urban infrastructure and welfare. They are available as cheap labour, but deprived of full social and political rights.

Slum tourism has the power to increase the visibility of poor neighbourhoods, which can in turn give residents more social and political recognition. Visibility can’t fix everything, of course. It can be highly selective and misleading, dark and voyeuristic or overly positive while glossing over real problems. This isn’t just true of slum tourism; it can also be seen in the domain of “virtual slumming” – the consumption of images, films and books about slums.

Yet slum tourism has a key advantage over “virtual slumming”: it can actually bring people together. If we want tourism to address global inequality, we should look for where it enables cross-class encounters; where it encourages tourists to support local struggles for recognition and build the connections that can help form global grassroots movements. To live up to this potential, we need to reconsider what is meant by tourism, and rethink what it means to be tourists.

- Volunteering

- Voluntourism

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

‘We are not wildlife’: Kibera residents slam poverty tourism

Tourism in Nairobi slum is rising but many residents are angry at becoming an attraction for wealthy foreign visitors.

Kibera, Kenya – Sylestine Awino rests on her faded brown couch, covering herself with a striped green shuka, a traditional Maasai fabric.

It’s exactly past noon in a noisy neighbourhood at the heart of Kibera, Kenya ‘s largest slum, and the 34-year-old has just finished her daily chores.

Keep reading

How one mexican beach town saved itself from ‘death by tourism’, photos: tourist numbers up in post-war afghanistan, malaysia’s airport fee hikes leave bad taste in travellers’ mouths, malaysia welcomes chinese tourists back in droves after pandemic slump.

Directly opposite Awino, her two daughters are busy studying for an upcoming math exam.

The family will not have lunch today.

“We don’t afford the luxury of having two consecutive meals,” says Awino, a mother of three. “We took breakfast, meaning we will skip lunch and see if we can afford dinner”.

Up until five years ago, Awino made a living selling fresh food in Mombasa, Kenya’s second largest city. There, she interacted with tourists who came to enjoy the sandy beaches of the Indian Ocean.

But in 2013, she decided to move to Kibera, in the capital, Nairobi, aiming for new opportunities – only to meet camera-toting tourists again, this time eager to explore the crowded slum where many are unable to afford basic needs.

“This was strange. I used to see families from Europe and the United States flying to Mombasa to enjoy our oceans and beaches,” says Awino, who is now a housewife – her husband, a truck driver, provides for the family.

“Seeing the same tourists manoeuvring this dusty neighbourhood to see how we survive was shocking,” she adds.

Awino recalls one incident a few months ago when a group of tourists approached her, with one of them trying to take a picture of her.

“I felt like an object,” she says. “I wanted to yell at them, but I was afraid of the tour guides accompanying them”.

![slum tourism national geographic Some residents say tourism in Kibera is morally wrong, while others are taking advantage of the trend by becoming tour guides [Osman Mohamed Osman/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/e88ee18754d04805ba51645d62295887_18.jpeg)

Kibera has seen a sudden rise of tourists over the past decade, with a number of companies offering guided tours showcasing how its residents live.

The slum faces high unemployment and poor sanitation, making living conditions dire for its residents.

According to Kenya’s 2009 census, Kibera is home to about 170,000 people. Other sources, however, estimate its population to be up to two million people.

Because of the high population, housing is inadequate. Many residents are living in tiny, 12ft by 12ft shack rooms, built in some cases with mud walls, a ridged roof and dirt floor. The small structures house up to eight people, with many sleeping on the floor.

Last week, thousands of families were left homeless after the government demolished homes, schools and churches to pave way for a road expansion.

Strolling through the dusty pathways sandwiched by the thin iron-sheet-walled houses, Musa Hussein is angry to see the growing popularity of the guided tours.

“Kibera is not a national park and we are not wildlife,” says the 67-year-old, who was born and raised here.

“The only reason why these tours exist is because [a] few people are making money out of it,” he adds.

The trade of showing a handful of wealthy people how the poor are living, Hussein argues, is morally wrong and tour companies should stop offering this service.

‘We created employment for ourselves’

Kibera Tours is one of the several companies that have been set up to meet the demand.

Established in 2008, the company has between 100 to 150 customers annually. Each client is charged around $30 for a three-hour tour, according to Frederick Otieno, the cofounder of Kibera Tours.

“The idea behind it was to simply show the positive side of Kibera and promote unique projects around the slums,” he says. “By doing this, we created employment for ourselves and the youth around us”.

The tour company employs 15 youths, working in shifts.

Willis Ouma is one of them.

Midmorning on a cloudy Saturday, the 21-year-old is wearing a bright red shirt. Accompanied by a colleague, he stands at one of the slum’s entrances, anxiously waiting to greet a group of four Danish tourists who have registered for the day’s tour.

“I have to impress them because tourists recommend to each other,” he says.

For three years, Ouma has been spending most of his weekends acting as a tour guide for hundreds of visitors.

“They enjoy seeing this place, which makes me want to do more. But some locals do not like it all,” he says, adding that he often has to calm down protesting residents.

Ouma earns $4 for every tour.

“This is my side hustle because it generates some extra cash for my survival,” he says. “I used my earnings to start a business of hawking boiled eggs”.

What would happen to an African like me in Europe or America, touring and taking photos of their poor citizens? by Sylestine Awino, Kibera resident

One of the Danish tourists is 46-year-old Lotte Rasmussen, a Nairobi resident who has toured Kibera more than 30 times, often with friends who visit from abroad.

“I bring friends to see how people live here. The people might not have money like us, but they are happy and that’s why I keep on coming,” she says, carefully bending down to take an image of a smiling Kibera toddler.

The tour includes stops at sites where visitors can buy locally-made craftwork, including ornaments and traditional clothing.

“We support local initiatives like children’s homes and women’s groups hence I do not see a problem with ethical issues,” says Rasmussen.

But Awino remains adamant.

She maintains that it is morally unfair that tourists keep on coming to the place she calls home.

“Think of the vice versa,” she says, “What would happen to an African like me in Europe or America, touring and taking photos of their poor citizens?”

![slum tourism national geographic Sylestine Awino was shocked to see tourists visiting Kibera to see how the residents live [Osman Mohamed Osman/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/63ac4ca0760849c984b0deb85cc852c0_18.jpeg)

Slumtourism.net

Home of the slum tourism research network, virtual tourism in rio’s favelas, welcome to lockdown stories.

Lockdown Stories emerged as a response to the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic has impacted communities all around the world and has brought unprecedented challenges. In the favelas of Rio de Janeiro this included the loss of income and visibility from tourism on which community tourism and heritage projects depend. In that context, Lockdown Stories investigated how community tourism providers responded, and what support they needed to transform their projects in the new circumstances. In these times of isolation, Lockdown Stores aims to create new digital connections between communities across the world by sharing ‘Lockdown Stories’ through online virtual tours.

We are inviting you to engage in this new virtual tourism platform and to virtually visit six favelas in Rio de Janeiro: Cantagalo, Chapéu Mangueira, Babilônia, Providência, Rocinha and Santa Marta.

The tours are free but booking is required. All live tours are in Portuguese with English translation provided.

Tours happen through November and December, every Tuesday at 7 pm (UK) / 4 pm (Brazil) Please visit lockdownstories.travel where you can find out more about the project.

This research project is based on collaboration between the University of Leicester, the University of Rio de Janeiro and Bournemouth University and is funded by the University of Leicester QR Global Challenges with Research Fund (Research England).

Touristification Impossible

Call for Papers – Research Workshop

Touristification Impossible:

Tourism development, over-tourism and anti-tourism sentiments in context.

4 th and 5 th June 2019, Leicester UK

TAPAM – Tourism and Placemaking Research Unit – University of Leicester School of Business

Keynotes by Scott McCabe, Johannes Novy, Jillian Rickly and Julie Wilson

Touristification is a curious phenomenon, feared and desired in almost equal measure by policy makers, businesses and cultural producers, residents, social movements and last but not least, tourists themselves. Much current reflection on over-tourism, particularly urban tourism in Europe, where tourism is experienced as an impossible burden on residents and cities, repeats older debates: tourism can be a blessing or blight, it brings economic benefits but costs in almost all other areas. Anti-tourism social movements, residents and some tourists declare ‘touristification impossible’, asking tourists to stay away or pushing policy makers to use their powers to stop it. Such movements have become evident in the last 10 years in cities like Barcelona and Athens and there is a growing reaction against overtourism in several metropolitan cities internationally.

This workshop sets out to re-consider (the impossibility of) touristification. Frequently, it is understood simplistically as a process in which a place, city, region, landscape, heritage or experience becomes an object of tourist consumption. This, of course, assumes an implicit or explicit transformation of a resource into a commodity and carries an inherent notion of decline of value, from ‘authentic’ in its original state to ‘commodified’ after touristification. In other words, touristification is often seen as a process of ‘selling out’. But a change of perspective reveals the complexities involved. While some may hope to make touristification possible, it is sometimes actually very difficult and seemingly impossible: When places are unattractive, repulsive, controversial, difficult and contested, how do they become tourist attractions? Arguably in such cases value is added rather than lost in the process of touristification. These situations require a rethink not just of the meaning of touristification, but the underlying processes in which it occurs. How do places become touristically attractive, how is attractiveness maintained and how is it lost? Which actors initiate, guide and manipulate the process of touristification and what resources are mobilised?

The aim of this two-day workshop is to provide an opportunity to challenge the simplistic and biased understanding of tourism as a force of good and touristification as desirable, so common among destination marketing consulting and mainstream scholarly literature. But it will equally question a simplistic but frequent criticism of touristification as ‘sell-out’ and ‘loss of authenticity’.

We invite scholars, researchers, practitioners and PhD students to submit conceptual and/or empirical work on this important theme. We welcome submissions around all aspects and manifestations of touristification (social, economic, spatial, environmental etc.) and, particularly, explorations of anti-tourism protests and the effects of over-tourism. The workshop is open to all theoretical and methodological approaches. We are delighted to confirm keynote presentations by Scott McCabe, Jillian Rickly, Johannes Novy and Julie Wilson.

The workshop is organised by the Tourism and Placemaking Research Unit (TAPAM) of the School of Business and builds on our first research workshop last year on ‘Troubled Attractions’, which brought together over 30 academics from the UK and beyond.

The workshop format

The research workshop will take place in the University of Leicester School of Business. It will combine invited presentations by established experts with panel discussions and research papers. Participants will have the chance to network and socialize during a social event in the evening of Tuesday 4 th June. There is small fee of £20 for participation. Registration includes workshop materials; lunch on 4 th and 5 th June 2019 and social event on 4 th June.

Guidelines for submissions

We invite submissions of abstracts (about 500 words) by 31 st April 2019 . Abstracts should be sent by email to: Fatos Ozkan Erciyas ( foe2 (at) le.ac.uk ).

Digital Technology, Tourism and Geographies of Inequality at AAG April 2019 in DC

Digital technology, tourism and geographies of inequality.

Tourism is undergoing major changes in the advent of social media networks and other forms of digital technology. This has affected a number of tourism related processes including marketing, destination making, travel experiences and visitor feedback but also various tourism subsectors, like hospitality, transportation and tour operators. Largely overlooked, however, are the effects of these changes on questions concerning inequality. Therefore, the aim of this session is to chart this relatively unexplored territory concerning the influence of technologically enhanced travel and tourism on development and inequality.

In the wake of the digital revolution and its emerging possibilities, early debates in tourism studies have been dominated by a belief that new technologies are able to overcome or at least reduce inequality. These technologies, arguably, have emancipatory potential, inter alia, by increasing the visibility of neglected groups, neighborhoods or areas, by lowering barriers of entry into tourism service provision for low-income groups or by democratizing the designation what is considered valuable heritage. They also, however, may have homogenizing effects, for example by subjecting formerly excluded spaces to global regimes of real estate speculation or by undermining existing labour market regimes and standards in the transport and hospitality industries. These latter effects have played a part in triggering anti-tourism protests in a range of cities across the world.

In this session we aim, specifically, to interrogate these phenomena along two vectors: mobility and inequality.

Sponsor Groups : Recreation, Tourism, and Sport Specialty Group, Digital Geographies Specialty Group, Media and Communication Geography Specialty Group Day: 03.04.2019 Start / End Time: 12:40 / 16:15 Room: Calvert Room, Omni, Lobby Level

All abstracts here:

New Paper: Tourist agency as valorisation: Making Dharavi into a tourist attraction

The full paper is available for free download until mid September 2017

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016073831730110X

Tourist agency is an area of renewed interest in tourism studies. Reflecting on existing scholarship the paper identifies, develops and critically examines three main approaches to tourism agency, namely the Service-dominant logic, the performative turn, and tourist valorisation. Tourist valorisation is proposed as a useful approach to theorise the role of tourists in the making of destinations and more broadly to conceptualise the intentions, modalities and outcomes of tourist agency. The paper contributes to the structuring of current scholarship on tourist agency. Empirically it addresses a knowledge gap concerning the role of tourists in the development of Dharavi, Mumbai into a tourist destination.

Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism

Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism: Current perspectives on urban tourism (Berlin 11/12 May 2017) conference program announced / call for registration

Tourism and other forms of mobility have a stronger influence on the urban everyday life than ever before. Current debates indicate that this development inevitably entails conflicts between the various city users. The diverse discussions basically evolve around the intermingling of two categories traditionally treated as opposing in scientific research: ‘the everyday’ and ‘tourism’. The international conference Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism: Current perspectives on urban tourism addresses the complex and changing entanglement of the city, the everyday and tourism. It is organized by the Urban Research Group ‘New Urban Tourism’ and will be held at the Georg Simmel-Center for Metropolitan Studies in Berlin. May 11, 2017, 4:15 – 5:00pm KEYNOTE – Prof. Dr. Jonas Larsen (Roskilde University): ‚Tourism and the Everyday Practices‘ (KOSMOS-dialog series, admission is free).

May 12, 2017, 9:00am – 6:00pm PANELS – The Extraordinary Mundane, Encounters & Contact Zones, Urban (Tourism) Development (registration required).

See full conference program HERE (pdf)

REGISTRATION

If you are interested in the panels you need to register. An attendance fee of 40 € will be charged to cover the expenses for the event. For students, trainees, unemployed, and the handicapped there is a reduced fee of 20 €.

For registration please fill out the registration form (pdf) and send it back until April 20, 2017 to:

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Georg-Simmel-Zentrum für Metropolenforschung Urban Research Group ’New Urban Tourism’ Natalie Stors & Christoph Sommer Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin You can also send us the form by email.

https://newurbantourism.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/conference-program.pdf

AAG Boston Programm

The slum tourism network presents two sessions at the Association of American Geographer Annual Meeting in Boston on Friday 7 April 2017 :

3230 The complex geographies of inequality in contemporary slum tourism

is scheduled on Friday, 4/7/2017, from 10:00 AM – 11:40 AM in Room 310, Hynes, Third Level

3419 The complex geographies of inequality in contemporary slum tourism

is scheduled on Friday, 4/7/2017, from 1:20 PM – 3:00 PM in Room 210, Hynes, Second Level

Stigma to Brand Conference Programme announced

From Stigma to Brand: Commodifying and Aestheticizing Urban Poverty and Violence

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, February 16-18, 2017

The preliminary programme has now been published and can be downloaded here .

For attendance, please register at stigma2brand (at) ethnologie.lmu.d e

Posters presenting on-going research projects related to the conference theme are welcome.

Prof. Dr. Eveline Dürr (LMU Munich, Germany) Prof. Dr. Rivke Jaffe (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Prof. Dr. Gareth Jones (London School of Economics and Politics, UK)

This conference investigates the motives, processes and effects of the commodification and global representation of urban poverty and violence. Cities have often hidden from view those urban areas and populations stigmatized as poor, dirty and dangerous. However, a growing range of actors actively seek to highlight the existence and appeal of “ghettos”, “slums” and “no-go areas”, in attempts to attract visitors, investors, cultural producers, media and civil society organisations. In cities across the world, processes of place-making and place-marketing increasingly resignify urban poverty and violence to indicate authenticity and creativity. From “slum tourism” to “favela chic” parties and “ghetto fabulous” fashion, these economic and representational practices often approach urban deprivation as a viable brand rather than a mark of shame.

The conference explores how urban misery is transformed into a consumable product. It seeks to understand how the commodification and aestheticization of violent, impoverished urban spaces and their residents affects urban imaginaries, the built environment, local economies and social relations.

What are the consequences for cities and their residents when poverty and violence are turned into fashionable consumer experiences? How is urban space transformed by these processes and how are social relationships reconfigured in these encounters? Who actually benefits when social inequality becomes part of the city’s spatial perception and place promotion? We welcome papers from a range of disciplinary perspectives including anthropology, geography, sociology, and urban studies.

Key note speakers:

- Lisa Ann Richey (Roskilde University)

- Kevin Fox Gotham (Tulane University)

Touring Katutura – New Publication on township tourism in Namibia

A new study on township tourism in Namibia has been published by a team of researchers from Osnabrück University including Malte Steinbrink, Michael Buning, Martin Legant, Berenike Schauwinhold and Tore Süßenguth.

Guided sightseeing tours of the former township of Katutura have been offered in Windhoek since the mid-1990s. City tourism in the Namibian capital had thus become, at quite an early point in time, part of the trend towards utilising poor urban areas for purposes of tourism – a trend that set in at the beginning of the same decade. Frequently referred to as “slum tourism” or “poverty tourism”, the phenomenon of guided tours around places of poverty has not only been causing some media sensation and much public outrage since its emergence; in the past few years, it has developed into a vital field of scientific research, too. “Global Slumming” provides the grounds for a rethinking of the relationship between poverty and tourism in world society. This book is the outcome of a study project of the Institute of Geography at the School of Cultural Studies and Social Science of the University of Osnabrueck, Germany. It represents the first empirical case study on township tourism in Namibia.

It focuses on four aspects: 1. Emergence, development and (market) structure of township tourism in Windhoek 2. Expectations/imaginations, representations as well as perceptions of the township and its inhabitants from the tourist’s perspective 3. Perception and assessment of township tourism from the residents’ perspective 4. Local economic effects and the poverty-alleviating impact of township tourism The aim is to make an empirical contribution to the discussion around the tourism-poverty nexus and to an understanding of the global phenomenon of urban poverty tourism.

Free download of the study from here:

https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/frontdoor/index/index/docId/9591

CfP Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism : Current perspectives on urban tourism

Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism : Current perspectives on urban tourism

11 and 12 of May 2017 in Berlin

Deadline for proposals: 1st December 2016

Find the f ull call here

Touristifizierter Alltag – Alltäglicher Tourismus: Neue Perspektiven auf das Stadttouristische

CfP AAG 2017

Cfp association of american geographers, boston 5th to 9th april 2017, the complex geographies of inequality in contemporary slum tourism.

The visitation of areas of urban poverty is a growing phenomenon in global tourism (Burgold & Rolfes, 2013; Dürr & Jaffe, 2012; Freire-Medeiros, 2013; Frenzel, Koens, Steinbrink, & Rogerson, 2015). While it can be considered a standard tourism practise in some destinations, it remains a deeply controversial form of tourism that is greeted with much suspicion and scepticism (Freire-Medeiros, 2009). In the emerging research field of slum tourism, the practices are no longer only seen as a specific niche of tourism, but as empirical phenomena that bridge a number of interdisciplinary concerns, ranging from international development, political activism, mobility studies to urban regeneration (Frenzel, 2016).

Slum tourism is sometimes cast as a laboratory where the relationships and interactions between the global North and South appear as micro-sociological encounters framed by the apparent concern over inequality. Beyond questioning the ways in which participants shape the encounters in slum tourism, structural implications and conditions come to the fore. Thus spatial inequality influences opportunities and hinders governance solutions to manage slum tourism operations (Koens and Thomas, 2016). Slum tourism is found to be embedded into post-colonial patterns of discourse, in which ‘North’ and ‘South’ are specifically reproduced in practices of ‘Othering’ (Steinbrink, 2012) . Evidence has been found for the use of slum tourism in urban development (Frenzel, 2014; Steinbrink, 2014) and more widely in the commodification of global care and humanitarian regimes (Becklake, 2014; Holst, 2015). Research has also pointed to the ethical implications of aestheticizing poverty in humanitarian aid performances and the troubles of on-the-ground political engagement in a seemingly post-ideological era (Holst 2016).

More recently a geographical shift has been observed regarding the occurrence of slum tourism. No longer a phenomenon restricted to the Global South, slum tourism now appears increasingly in the global North. Refugee camps such as Calais in the north of France have received high numbers of visitors who engage in charitable action and political interventions. Homeless tent cities have become the subject of a concerned tourist gaze in the several cities of the global north (Burgold, 2014). A broad range of stigmatised neighbourhoods in cities of the global North today show up on tourist maps as visitors venture to ‘off the beaten track’ areas. The resurfacing of slum tourism to the global North furthers reinforces the need to get a deeper, critical understanding of this global phenomena.

Mobility patterns of slum tourists also destabilise notions of what it means to be a tourist, as migrants from the Global North increasingly enter areas of urban poverty in the South beyond temporal leisurely visits, but as low level entry points into cities they intent to make their (temporal) home. Such new phenomena destabilise strict post-colonial framings of slum tourism, pointing to highly complex geographies of inequality.

In this session we aim to bring together research that casts the recent developments in slum tourism research. We aim specifically in advancing geographical research while retaining a broad interdisciplinary outlook.

Please sent your abstract or expressions of interest of now more than 300 words to Tore E.H.M Holst ( tehh (at) ruc.dk ) and Thomas Frisch ( Thomas.Frisch (at) wiso.uni-hamburg.de ) by October 15 th 2016

Becklake, S. (2014). NGOs and the making of “development tourism destinations.” Zeitschrift Für Tourismuswissenschaft , 6 (2), 223–243.

Burgold, J. (2014). Slumming in the Global North. Zeitschrift Für Tourismuswissenschaft , 6 (2), 273–280.

Burgold, J., & Rolfes, M. (2013). Of voyeuristic safari tours and responsible tourism with educational value: Observing moral communication in slum and township tourism in Cape Town and Mumbai. DIE ERDE – Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin , 144 (2), 161–174.

Dürr, E., & Jaffe, R. (2012). Theorizing Slum Tourism: Performing, Negotiating and Transforming Inequality. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos Y Del Caribe , 0 (93), 113–123

Freire-Medeiros, B. (2009). The favela and its touristic transits. Geoforum , 40 (4), 580–588.

Freire-Medeiros, B. (2013). Touring Poverty . New York N.Y.: Routledge.

Frenzel, F. (2014). Slum Tourism and Urban Regeneration: Touring Inner Johannesburg. Urban Forum , 25 (4), 431–447.

Frenzel, F. (2016). Slumming it: the tourist valorization of urban poverty . London: Zed Books.

Frenzel, F., Koens, K., Steinbrink, M., & Rogerson, C. M. (2015). Slum Tourism State of the Art. Tourism Review International , 18 (2), 237–252.

Holst, T. (2015). Touring the Demolished Slum? Slum Tourism in the Face of Delhi’s Gentrification. Tourism Review International , 18 (4), 283–294.

Steinbrink, M. (2012). We did the slum! Reflections on Urban Poverty Tourism from a Historical Perspective. Tourism Geographies , 14 (2), forthcoming.

Steinbrink, M. (2014). Festifavelisation: mega-events, slums and strategic city-staging – the example of Rio de Janeiro. DIE ERDE – Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin , 144 (2), 129–145.

Essay Series

- Expert Speak

- Commentaries

- Young Voices

- Issue Briefs

- Special Reports

- Occasional Papers

- GP-ORF Series

- Books and Monographs

Browse by Topics

Progammes & centres.

- SUFIP Development Network

- Centre for New Economic Diplomacy

- Centre for Security, Strategy & Technology

- Neighbourhood Studies

- Inclusive Growth and SDGs

- Strategic Studies Programme

- Energy and Climate Change

- Economy and Growth

- Raisina Dialogue

- Cape Town Conversation

- The Energy Transition Dialogues

- CyFy Africa

- Kigali Global Dialogue

- BRICS Academic Forum

- Colaba Conversation

- Asian Forum on Global Governance

- Dhaka Global Dialogue

- Kalpana Chawla Annual Space Policy Dialogue

- Tackling Insurgent Ideologies

- Climate Action Champions Network

- Event Reports

- Code of Conduct

- ORF Social Media Advisory

- Committee Against Sexual Harassment

- Declaration of Contributions

- Founder Chairman

- Work With Us

- Write For Us

- Intern With Us

- ORF Faculty

- Contributors

- Global Advisory Board

- WRITE FOR US

Slum Tourism: Promoting participatory development or abusing poverty for profit?

Author : Aditi Ratho

Issue Briefs Published on Feb 21, 2019 PDF Download

This brief is part of ORF’s series, ‘Urbanisation and its Discontents’. Find other research in the series here :

Attribution: Aditi Ratho, “Slum Tourism: Promoting Participatory Development or Abusing Poverty for Profit?”, ORF Issue Brief No. 278, February 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

The concept of “slum tourism” has been around since the time the rich wanted to experience life in the “deprived” and “risqué” spaces occupied by the marginalised communities of late-19 th -century London. [1] Today it is a profitable business, bringing more than a million tourists every year to informal settlements in various cities across the world. [2] Proponents of the industry say that slum tourism creates discourse that could result in positive change, and that the profits help the local slum communities. Critics argue that the tours are intrinsically exploitative. This brief takes stock of some of the more well-established slum tours in different parts of the world, evaluates the genesis of the industry and, using Mumbai’s Dharavi as a case study, probes its current relevance.

- Introduction

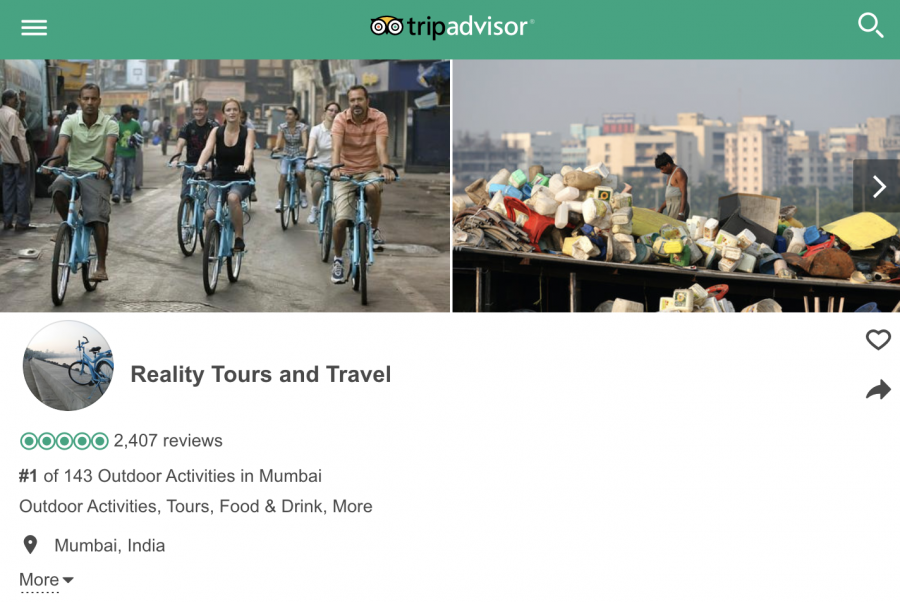

Typing in “slum tours” on the popular travel website, Tripadvisor , will lead to pictures of smiling, well-dressed foreign tourists, their arms around locals, with derelict slums in the background. “Slum tours”, as a concept, can be traced to the act called “slumming” in the 1860s; “slumming” itself was a word added to the Oxford Dictionary at the time, meaning “to go into, or frequent, slums for discreditable purposes; to saunter about, with a suspicion, perhaps, of immoral pursuits.” [3] Slumming became a routine activity when rich Londoners braved the city’s notorious East End in the late 19 th century. They left their elegant homes and clubs in Mayfair and Belgravia – still London’s most upmarket neighbourhoods until today – and crowded onto horse-drawn omnibuses bound for midnight tours of the slums of East London. [4] More than a century later, the practice was brought to New York City as a form of amusement to compare slums abroad, giving birth to the designated touring practices through the non-white section of Harlem. [5] Oxford and Cambridge Universities also started using the concept to understand underprivileged neighbourhoods and inform 19 th -century social development policy by witnessing first-hand the lives of people living in those areas. [6]

The Oxford dictionary has since revised its definition of slumming to mean, “to spend time at a lower social level than one’s own through curiosity or for charitable purposes”—which might aptly describe the current phenomenon of “slum tourism” in different parts of the world. Today, it is estimated that one million people go on slum tours every year. [7] This number is remarkable enough, even if compared with the big number of 300 million tourists who visited religious sites in 2017. [8] Eight out of every 10 of these tourists go to either the shanty towns of Cape Town or the favelas [1] of Rio de Janeiro. [9] To be sure, tourism is an ever-evolving commercial activity that continuously looks for novelty in destinations. [10] This nature lends tourism to a variety of genres of interest, depending on the assortment of sites and experiences offered by particular destinations. In a time of globalised experiences, however, the novelty factor in travelling tends to get muted more easily, and the demand for more unique forms of travel increases: among them, adventure tourism, reality tours, artisanal tours, and poverty tours. These are called “niche travel” in tourism parlance. Slum tourism itself has grown into a well-organised, global industry, with over 300,000 visitors touring slums in Cape Town in 2007 and 40,000 tourists exploring the favelas of Rio de Janeiro in 2009. [11]

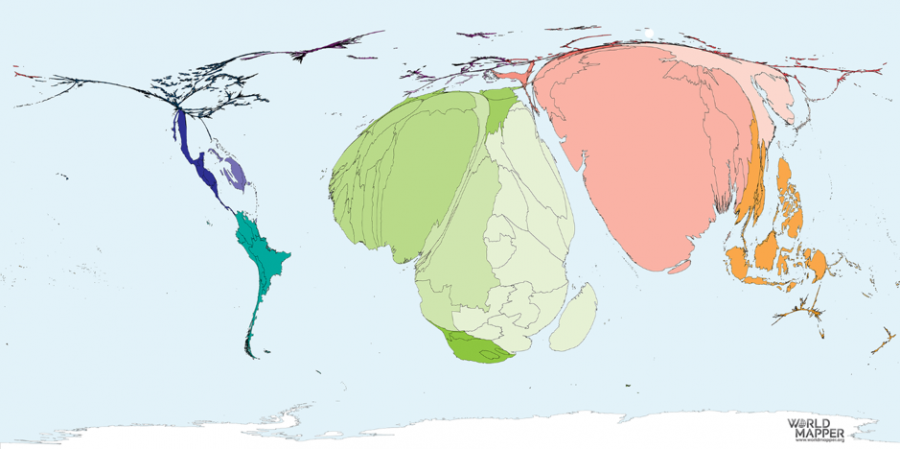

The contemporary wave of slum tourism started in South Africa and Brazil in the 1990s, and it has now expanded to several cities, as seen in Figure 1.

Tours of the South African townships were first conducted in the 1990s by local residents to help raise global awareness about the rampant human rights violations in their marginalised and racially segregated areas. Meanwhile, in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil and landfills of Tondo in the Philippines, tours are conducted not by the community people but by outsiders who work with local guides. Whether in Cape Town or Tondo, however, these tours purport to have the same aim of offering the experience of “real-life surroundings” to visitors. [12]

A 2010 research paper on slum tourism in Mumbai found that most people embark on slum tours because they are interested in that culture, and they want to learn about the living conditions of the residents of those communities. [13] Herein lies the inherent paradox in slum tourism: while its supposed objective is to increase awareness about the lives of the poor, it also attempts to show tourists the positive aspects of those very same lives. In these tours, slums are ingeniously described as places meant for the experience of reality, where the focus is not on the squalor and poverty of the residents but on the presentation of “positive socio-economic development impulses and alternative forms of development that defy normal approaches”. [14] This creates a dissonance between the intent and effect of slum tourism – while it is meant to create awareness, it invariably ends up glossing over the unfortunate facets of poverty and adversity, much less their structural causes.

Existing scholarly work on the subject focuses on whether this form of tourism engenders positive socio-economic impact. As elaborated by Frenzel, “slum tourism promoters, tour providers as well as tourists claim that this form of tourism contributes to development in slums by creating a variety of potential sources of income and other non-material benefits.” [15] The question, however, is how far in fact do tourists come to an understanding of local problems, or whether they indeed engage in any actions, post-tour, to affect concrete change. Slum tourism also raises ethical issues: do these tours end up merely objectifying the poor, and do these visits not violate the people’s privacy, to begin with?

- Slum Tourism: Dimensions and Forms

Following the end of apartheid in South Africa in the early 1990s, the country saw a significant increase in the number of international arrivals from 3.6 million in 1994 to 9.1 million in 2002. In that period, the tourism sector outshined the historically lucrative gold-mining sector in revenues. [16] Tourism in post-apartheid South Africa started off as a niche form of tourism for politically interested travellers who wanted to visit the South Western Townships (or Soweto), which were the centre of political repression during the anti-apartheid struggle. [17] Since then, tour destinations in the country have expanded along the same theme, trying to engage tourists with the urban residents of areas that were formerly classified as “non-white” and planned according to the old regime’s championship of racial segregation.

Today most of the slum tourists who visit South Africa are from Britain, Germany, Netherlands and the US. [18] Organisers say that these slum tours can be a direct way of raising awareness about the debilitating effects of policy-level racial segregation. Such awareness, in turn, could lead to changes in the cognisance and attitudes of the tourists towards issues of racism affecting migrants in their own countries. The result of these tours, therefore, may be different from those in Mumbai, Rio, or Manila—there is potential for these tourists to learn certain lessons from the tour and contribute positively to their home country, as opposed to ending their engagement with the tour itself. However, most other slum tours – for example, in Mumbai – are not based on a narrative of historical discrimination, but merely highlight the current problems of inequality and poverty and are touted to help lead to solutions.

In both South Africa and Brazil, unlike in India, policy has played a key role in the expansion of slum tourism. Policymakers have promoted, for example, locations of the anti-apartheid struggle by creating museums and sites of political heritage in cities like Cape Town, Durban and Johannesburg. Rio de Janeiro, for its part, has developed plans for museums of the favela region. [19] Sports has also played a part in promoting slum tourism in both Brazil and South Africa. The FIFA World Cup, which both countries have hosted, involved tours where football was at the centrestage of the experience. Those tours happened to be in the poorer sections of society.

Due to high-level policy interventions, local involvement in tours in both these countries is limited. This is not the case with the slum tours in Mumbai. According to the research by Frenzel et al (2015), “in practicality all major slum tourism destinations the most popular tours are run by tour operators, NGOs, or guides who are based outside the slums.” [20] Some of the earliest tours in South Africa were operated by local residents, but they have now been displaced by the more professional tour operators, many of them under external ownership (i.e., white). [21] Therefore, even as there could potentially be an increase in awareness, the lack of local participation negates the argument that slum tourism benefits the society that is being “experienced”. Freire-Medeiors, in an extensive research of Rio’s favelas, further points to significant levels of economic leakage occurring in slum tourism and recommends that visitors be made aware of what portions of the profit of slum tours actually goes back into local communities. [22] A study of the residents’ reactions by Frenzel et al. shows that these tours “challenge negative perspectives, breaks the isolation of citizens, and [engenders] a sense of pride that foreign tourists are interested” [23] in their lives. At the same time, the research also mentions that few residents mention direct economic gain or employment as benefits of these tours; therefore, whatever positive results that are obtained are insubstantial and short-term.

- The Case of Dharavi

The Dharavi area of Mumbai is the second-largest slum in Asia, and the third-largest in the world. Dharavi is not a desolate and deprived community of unemployed squatters. Within the congested alleys of shanties there are booming home industries that sustain 20,000 small-scale units. [24]

A New York Times mapping of the industrial slum area describes the northern 13th Compound as the heart of Dharavi’s recycling industry, where an estimated 80 percent of Mumbai’s plastic waste is recycled in approximately 15,000 single-room factories. [25] It also describes the southern Kumbharwada region as production spaces of the migrant potters from Saurashtra . The Maharashtra Slum Redevelopment Authority (SRA) describes Dharavi’s growth as “closely interwoven with the pattern of migration into Bombay”, [26] due to the land being free and unregulated. Together with Muslim tanners from Tamil Nadu, artisans and embroidery workers from Uttar Pradesh and other migrants setting up retail food shops, the area provides employment opportunities irrespective of region, caste, and religion. The SRA also states that most of the land in Dharavi is owned by government agencies, making it easier to set up informal settlement.

These industries and labour are part of the informal economy – it is not taxed, it is not monitored by the government, nor is its contribution to the overall economy of the city properly accounted for. Interventions to improve the infrastructure, provide sanitation, drainage, and electricity facilities are ad-hoc and not policy-driven.

In order to increase awareness about the poor living conditions, there exist several profit-making Dharavi slum tours, which also claim to be facilitating the development of the community. A company founded in 2005 provides educational walking tours of Dharavi. The company claims that 80 percent of its profits go to its NGO, which runs high-quality education programmes for Dharavi residents. Another company, started by Dharavi residents themselves, works to support local students to study full-time and also trains and employs them as tour guides.

On several global tourism portals, “five-star” reviews for these tours highlight their so-called “awareness quotient”. The reviews range from wanting to “meet some additional locals as they were all extremely nice and friendly” to expressing surprise that there was “extreme poverty everywhere, but so much life!” [27] Most of the “Poor” and “Terrible” reviews do not mention the nature of tourism, but rather disapprove of the experience in the dirty, congested slum. Reviewers generally note that though there was poverty, there was no suffering and people living in the slums “seemed happy”. Melissa Nisbett, professor at King’s College London, analysed more than 230 such reviews and concluded that for most Dharavi visitors, desolation in poverty simply did not exist. Nisbett’s analyses of the reviews show that “poverty was ignored, denied, overlooked and romanticised, but moreover, it was de-politicised.” [28] Without discussing the reasons why the slums existed, the tours de-contextualised the plight of the poor and seemed only to empower the privileged, she noted. A contrary view is held by other analysts, including for instance, Fabian Frenzel, who argues that since poverty lacks recognition and voice, tourism provides the audience a much-needed story to be told, and even “ taking the most commodifying tour is better than ignoring that inequality completely .” [29]

One of the main slum tour operators in Dharavi is not based in the area and only ropes in locals to lead the tours. Its website [30] takes pride in Dharavi’s thriving industry. Dharavi is portrayed as the hub that “supplies celebrations for a century” (through handcrafted idols and sweets), “the height of fashion” (the second-largest leather apparel industry in India), and the birth of “Swachh Bharat Abhiyaan” (due to 80 percent of the city’s plastic being recycled here). The website then describes how tourists have been “inspired” by visiting these successful industries “in the midst of derelict conditions”. The question that needs to be asked is whether such depictions end up obscuring the need to improve the living conditions of the residents.

The company claims that “bulldozing [Dharavi] and starting again” would be unfeasible. In slums like Dharavi, common ground needs to be found where industry is recognised and legalised and given the correct infrastructure to thrive. Property rights on land and dwellings must be created for the residents under the purview of the development schemes of the government to enable them to participate actively in the formal economy with better access to credit.

Plans for the redevelopment of Dharavi have been mooted for nearly 15 years and gone through multiple stages, recommending various permutations and combinations of public-private-partnerships (PPP) for the project. The current Dharavi Redevelopment Plan will be operated as a Special Purpose Vehicle under the Dharavi Redevelopment Authority and funded by the government and a private company based in Dubai. While it seems like this plan might finally take shape in the near future, there needs to be a concerted effort to not only focus on amenities, maintenance, and rehabilitation, but a clear understanding of the nature of economic activities and the spatial requirements. The Dharavi slum industry is thriving and income-generating, and any significant adverse impact of the SRA’s redevelopment plan would be detrimental and unsustainable for its denizens. Until such time that the much-debated redevelopment becomes a reality, Dharavi will continue to attract slum tourists.

- Awareness of poverty or obfuscation of development?

Slum tours can become part of a vicious cycle where the run-down aspects of a community are used for commercial gain. The section of the community that benefits from the tours has no incentive to participate in improving the community. While infrastructure development projects are at a standstill due to the lack of property rights and the informal nature of the economic activities, being outside the tax net is also beneficial to the poor artisans. These factors have led to a community that has—either willingly or unwillingly—found itself embedded into an ethically-inappropriate but financially-viable conundrum.

The government needs to find viable alternatives for such communities – alternatives that support its active industry, while also covering the opportunity costs of eliminating slum tourism. There are currently already about 100 construction projects in Dharavi undertaken by the SRA, which are mainly limited to housing. [31] However, such redevelopment must ensure that the existing industrial infrastructure is also protected and refurbished. Residents are likely to reject housing that does not sustain their current ecosystem for income-generation. These residents can have better housing conditions and commercial opportunities and should not be living in the squalor that slum tours tend to glorify and sustain. The redevelopment plan will face stiff opposition, distrust, and backlash, unless the complexity of economic activities and the interrelated nature of dwellings and industrial units is properly mapped and taken into account in the design of the redevelopment plan. It is essential to educate the community through the process by providing examples of successful redevelopment projects, imparting the importance of basic infrastructure (including hygiene, sanitation, electricity, and housing), and ensuring that there is no loss to indigenous industries. Slum tourism will die a natural death if the people living in slums are empowered with efficient civic amenities along with housing, workplaces, and formal property rights.

Writer Manu Joseph’s account of eco-tourism is relevant in the slum tourism debate as well: if an industry is going to function without the support of the informed and the ethical, then it is at risk of becoming more callous. [32] Slum tours in the townships of South Africa and the favelas of Brazil have a clear objective of raising historical and cultural awareness about the destitute areas. Similar tours in Dharavi, however, seem to be running on the profitability of showcasing uplifting stories of industriousness despite adversity, altogether forgetting to bother with any element of historical or cultural awareness.

While citizens of the slum areas might seem to benefit from these tours, finding an alternative form of development in terms of industry and employment is essential in order to lift the community from this irony of “profitable poverty”. Slum tourism in India does not appear to have created any impetus in this direction, as is evident from the case of Dharavi. Slum tours aim to dispel notions that people may have of slums being a place of misery; however, the glorification of slum tourism is unjustified, as it may actually serve to evade the real issues and challenges confronting slum dwellers and their prospects for improving their lives.

Aditi Ratho is a lecturer of Political Science at the Government Law College, Mumbai. She has previously worked as a researcher for the World Bank and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

[1] A favela is a Brazilian Portuguese term to describe an urban area of slums, shantytown, or shacks.

[1] Meschkank, Julia. “ Investigations into Slum Tourism in Mumbai: Poverty Tourism and the Tensions between Different Constructions of Reality “. GeoJournal 76, no. 1 (2010): 47.

[2] Shepard, Wade. “ Slum Tourism: How It Began, the Impact It Has, and Why It Became so Popular “. Forbes , July 16, 2016.

[3] Blau, Christine. “ Inside the Controversial World or Slum Tourism “. National Geographic , April 25, 2018.

[4] Meschkank, “Investigations,” 48

[6] Blau, “Inside.”

[7] Shepard, Wade. “ Slum Tourism: How It Began, the Impact It Has, and Why It Became so Popular “. Forbes , July 16, 2016.

[8] Tomljenović, Renata, and Larisa Dukić. “ Religious Tourism – from a Tourism Product to an Agent of Societal Transformation “. Proceedings of the Singidunum International Tourism Conference – Sitcon 2017 (2017): 1.

[9] Frenzel, Fabian, Ko Koens, Malte Steinbrink, and Christian M. Rogerson. “ Slum Tourism: State of the Art “. Tourism Review International 18, no. 4 (2015): 237.

[10] Steinbrink, Malte. “‘We Did the Slum!’ – Urban Poverty Tourism in Historical Perspective.” Tourism Geographies 14, no. 2 (2012): 215

[11] Steinbrink,”‘We.”215.

[12] Blau, “Inside.”

[13] Meschkank, “Investigations.” 48-50.

[14] ibid

[15] Frenzel, Fabian. “Slum Tourism in the Context of the Tourism and Poverty (Relief) Debate.” Die Erde, 144 (2013): 117

[16] Steinbrink, “‘We,” 216..

[17] ibid, 217

[18] ibid

[19] ibid

[20] Frenzel et al, “Slum,” 242.

[21] ibid, 244

[22] Friere-Medeiros, Bianca. “ The Favela and Its Touristic Transits “. Geoforum 40, no. 1 (2009), 586.

[23] Frenzel et al, “Slum,” 246

[24] Assainar, Raina. “ At the Heart of Dharavi Are 20,000 Mini-factories “. The Guardian , November 25, 2014.

[25] “ An Industrial Slum at the Heart of Mumbai “. The New York Times , December 28, 2011.

[26] “ Growth History “, Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Accessed January 10, 2019.

[27] “ Dharavi Slum Tours of Mumbai ”, Tripadvisor, Accessed January 10, 2019.

[28] Nisbett, Melissa. “ Empowering the Empowered? Slum Tourism and the Depoliticization of Poverty “. Geoforum 85 (2017): 42.

[29] Blau, “Inside.”

[30] “ How Dharavi Makes a Difference: Eight Surprising Facts About Mumbai’s Largest Slum ”, Reality Tours & Travels, accessed February 15, 2019.

[31] “ Our Projects ”, Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Accessed January 10, 2019.

[32] Jospeh, Manu. “ How much conscience should a traveler possess ”. Conde Nast Traveller , September 4, 2017.

- Development

- Urbanisation in India

- Urbanisation

- Slum Tourism

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Aditi Ratho

Aditi Ratho was an Associate Fellow at ORFs Mumbai centre. She worked on the broad themes like inclusive development gender issues and urbanisation.

Publications

What ails the Plastics Treaty negotiations: It’s not India

Climate, food and environment | developing and emerging economies, apr 12, 2024.

Nepal’s new coalition government: A solution for its political woes?

Neighbourhood.

Storytelling in a Slum's Silicon Valley

Dharavi Diary Students create art installations for Earth Day using recycled materials. (Image courtesy of Dharavi Diary)

Dipali, a young girl half my size, fetched me from a busy intersection in Dharavi, a locality in Mumbai with one of the largest slums in the world. While she led me to her after school program, we talked about her classes, how many languages she knows (4), and her extra-curriculum studies in coding. She talked excitedly about HTML programming, but I could not understand what she was saying -- not because of her English, which was perfect, but because I am a terrible Millennial and do not know back ends from front ends of digital devices.

At the top of a steep narrow staircase that descends into one of the slum’s neighborhoods, we slipped into a small room filled with perhaps two dozen students sitting side by side, calmly flipping through workbooks, chatting on the couch and tapping away on computers. As an after-school educator, I have rarely seen such diligent and relaxed demeanors.

This is basecamp of Dharavi Diary: A Slum & Rural Innovation Project founded by Nawneet Ranjan in 2014, it focuses primarily on empowering young girls in the neighborhood through technological literacy . The girls learn computer skills and quickly began to code and develop applications geared towards female issues like violence and housework within the community.

Student-designed smartphone application to help protect women in the slums and around Mumbai from male violence. (Image courtesy of Dharavi Diary)

“We started with 14 girls, and it quickly grew to 140. Boys started coming, and we couldn’t turn them away. We were in the basement of this building then,” Ranjan told me.

“Moving on up,” I quip.

“Yes exactly, that’s part of the narrative.”

Storytelling is the fulcrum of the program. Students use visual, performing and language arts to explore subjects and interpersonal relations. Every 15 days, over 200 students in the after-school program work on their respective “Who Am I” stories, a writing project to reflect on personal strengths, weaknesses, and how to develop the narratives they want to live and tell.

The stories are not always easy to share, as the students regularly experience and witness abuse, violence and the very painful realities of living in poverty. Showing vulnerability towards such personal truths is not something many of us are able to do in a public setting, so Ranjan focuses on cultivating ownership and a safe space that belongs to the youth. “They have the keys to the building,” he tells me. It made me remember the time I trusted a student with a key to a garden shed. The story ends with me purchasing bolt cutters…

“Stories make learning more fun," Ranjan explains. "The bridge [in learning] becomes more organic. When we share our stories, we understand we are part of a larger family tree.”

Ranjan comes from a storytelling background, including touring India as a teenager performing community theater to draw attention to the injustices of the Bhopal gas leak , and also documentary work in both India and San Francisco. He invites youth to use narrative platforms to explore what is important to them.

Two Dharavi Diary student give a presentation about gender. (Image courtesy of Dharavi Diary)

The students recently finished hosting more than 50 community screenings of “Period of Change,” a film they collectively made about menstruation, still an extremely taboo subject throughout India . By making this documentary together, not only did the female students have an opportunity to express their hardships, but the male students could better comprehend their peers’ experiences and help assess solutions for change.

“Through regular dialogue, the really complex issues we face often become quite simple,” Ranjan believes.

Since the start of the program, Ranjan has noticed change in how the female youth are treated in their community: “They are starting to participate in decisions and see larger pictures. Domestic violence is going down and so is the rate of young marriages.” He adds that overall, both female and male students are improving in scholastic performance, most moving into the 70th or 80th percentile of their classes.

“We are not learning how to memorize and vomit information," he says. "We are learning about the process and how to celebrate it. When you understand the process, you care more.”

I met with Ranjan and his students to help provide some resources and ideas for expanding their gardening projects. They had already planted dozens of fruit-bearing and medicinal trees around the field where they play football, but wanted to explore more vegetable production. For an organization so focused on technological literacy, I was surprised by the interest in gardening. “Nothing is in isolation,” Ranjan tells me. “Gardening can help shift the consciousness of the urban notion. It also gives students grit.”

I could not agree more. A garden offers a space for exploring so many different subjects, emotions, skills, and especially life cycles. It is a space wrapped intricately in life and death, depicting the beauty and necessity of both.

In front of their new space where Dharavi Diary students plan to build an indoor garden and host salad bar pilot project. (Image credit Lauren Ladov)

Ranjan and a couple of the male students lead me upstairs to their recently acquired street-facing space (moving on up again). Lifting the heavy shutter door revealed a dark interior with high corrugated metal walls which would surely radiate the summer heat more intensively. Immediately, I envisioned vining trellises of beans climbing skyward, suspended bamboo troughs holding strawberries, buckets of hot peppers, tomatoes, and assorted herbs lining every inch of floor. The grey gloom could soon meet green vibrancy. The students seemed excited by the potential, especially the strawberry idea.

The Dharavi gardens will also serve as a pilot for a salad bar project, testing best practices for growing greens in small spaces so they can share the methods with unemployed mothers in the community who can earn extra cash through their harvests. Ranjan constantly encourages students to see the potential for frugal and improvisation innovation all around them. For instance, houses in the slums are often stacked on top of each other, so staircases are extremely steep. Many families hang ropes so the stairs are easier to climb. This is innovation. Or, when a panel in a fan breaks, fashioning a new panel out of cardboard is not only quick-thinking but accessible. This is innovation.

“I want to see these students grow into sustainable creators, focusing on ecological, local and longterm solutions for products. We do not need more obedient Unilever consumers. We have a different kind of Silicon Valley here,” he explains. Sitting in the room are youth from all corners of India. The Dharavi square mile is not just one of the most populated, it is one of the most ethnically diverse in India.

“Diversity is giving space to the other, having a safety net for sharing different points of view -- where you have the freedom to say “no” or to experiment. And we use our diversity for problem-solving,” Ranjan reveals.

Dharavi Diary student-made mural on local college wall depicting their view of Mumbai. (Image credit Lauren Ladov)

I inquire about the problem of sea-level rise for this coastal community of over 1 million, whose homes are generally constructed with makeshift materials.

“Climate change is a luxurious conversation to have when every day you are struggling to survive,” he says.

I nod, hearing echoes of this particular sentiment from similar communities who do not live in the Unilever-realities where we wring our hands over which type of laundry detergent to buy.

The students file out of the center to play football across the street. I leave too, knowing that these young people are the ones equipped with the skills, moral fiber, emotional depth and imagination to solve any problem confronting their community. We just have to give them the space to be free.

The National Geographic Society is a global nonprofit organization that uses the power of science, exploration, education and storytelling to illuminate and protect the wonder of our world. Since 1888, National Geographic has pushed the boundaries of exploration, investing in bold people and transformative ideas, providing more than 15,000 grants for work across all seven continents, reaching 3 million students each year through education offerings, and engaging audiences around the globe through signature experiences, stories and content. To learn more, visit www.nationalgeographic.org or follow us on Instagram , LinkedIn, and Facebook .

Tourists are always eager to see authentic destinations and find out how the locals live. It is not only trendy shopping districts that attract tourists, but many are keen to visit the living quarters of the less privileged, i.e., slums of some of the largest cities in the world.

Yrkeshögskolan Novia

lehtori, matkailuliiketoiminta Senior Lecturer, tourism business Haaga-Helia ammattikorkeakoulu

There are interesting developments and trends in tourism that we are constantly following. Sometimes we get a chance to experience them as well. Our SUCSESS project meeting in South Africa gave us an opportunity to visit a slum tourism destination. We wanted to dig deeper into this phenomenon, and this is what we found out.

Slum tourism is not a new phenomenon

The roots of slum tourism are in the 19th century, with London, New York and San Francisco among the famous slum destinations in the past centuries (Bednarz 2018; Frenzel et al 2015). These days, the most famous slum destinations are in the BRICS countries of Brazil, India and South Africa.

The favelas of Rio de Janeiro started the trend with guided tours for tourists to see how the slum dwellers live. The movie Slumdog Millionaire made Mumbai’s Dharavi famous. The founding fathers of post-Apartheid South Africa, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu, made Soweto in Johannesburg the slum to visit and to see the urban poor.